Sarah; more active now on my alternate account, @ishido-enjoyer.Author of Joachim Murat: A Portrait in Letters, available on Amazon.https://projectmurat.wordpress.com

Last active 2 hours ago

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Rip Murat you would love white girl party music

207 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tagged by @monaldus :)

currently reading: “S” by Koji Suzuki, “A History of Japan” by R.H.P. Mason & J.G. Caiger, and “Why War?” by Richard Overy.

last song: “Fake Divine” by Hyde.

last film: The last one I finished was Hell House III. I’m like 90 minutes into Tokugawa: Rise of the Shogun on Amazon Prime and watching it piecemeal because it’s 4 hours long.

last series: Squid Game.

sweet/salty/savory: Savory.

tea or coffee: Both. But if given the choice I will choose an iced matche latte 95% of the time.

working on: Studying Japanese, translating a manga about Ishida Mitsunari, plotting the rest of A Duel of Sparrows, and job-hunting/preparing to possibly relocate. It’s going to be a busy summer.

tagging: @almhw85 @chaot1cotter @fahre @surullinenotus @christinethalassinou @alsatianus

(No worries if you don’t want to do it. :)

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

‘Bust of Jean-Baptiste Kléber, General-in-Chief of the Eastern Army’ – 1839

‘Bust of Jean-Baptiste Kléber, General-in-Chief of the Eastern Army’

By Philippe-Joseph-Henri Lemaire; that is located at the Galerie des Bataille, Aile du Midi, Château de Versailles.

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Things I learned while having dinner with Murat

“Prince” is his courtesy title, but he's not the Prince Murat - for now, that's his father. He is the Prince of Ponte Corvo, a title that originally belonged to the Bernadotte family, but which Napoleon gave to the Murats out of spite

With the marriage of Cécile Ney and Joachim Murat in 1884, the title of Prince de la Moskowa… also went to the Murats. The Ney family is apparently still very upset about it. As a consequence, we have been calling him Monsieur le Prince de la Moskowa the whole night

Like his ancestor, he just cannot stand Davout and considers that, despite his military talents, he is insufferable, and I quote: “If Murat hadn't been there, Davout would have died in ten seconds” (I don't remember which battle he was rambling about)

His favourite Napoleonic Marshals, apart from Murat, are Bessières and Lannes

“Contrary to common belief, Murat and Lannes got on very well” (again, I'm quoting him)(and I guess he has letters and family archives to support this claim)

He enjoys rosé wine (disgusting)

And for those who want to know what was on the menu, we had duck breast with honey-port sauce, vegetables and apricot clafouti

147 notes

·

View notes

Text

Quick sketch of Christopher Plummer as Duke of Wellington sketch i did yesterday evening

128 notes

·

View notes

Text

My first trip to Japan - Day 11 & 12

After the impromptu hike up Mt Shizugatake on Monday—and just being pretty worn out in general at this point—I decided to take it a bit easy on Tuesday. I took the train down to Hikone to see the statue of Mitsunari and Hikone Castle.

Right outside Hikone Station is a statue of Ii Naomasa, who hated Mitsunari and therefore sided with Tokugawa Ieyasu at Sekigahara despite having served Hideyoshi prior to his death. After Sekigahara, Ieyasu awarded Naomasa with Sawayama Castle, which had formerly belonged to Mitsunari and his family (it was actually besieged by one of Sekigahara’s most notorious traitors, Hideaki Kobayakawa, shortly after Sekigahara under Ieyasu’s orders, and Mitsunari’s father and brother, who were holding it, both committed seppuku). Naomasa found Sawayama unsuitable (partially because he disliked its former owner so much) and decided to tear it down and replace it with a new castle instead, and so Hikone Castle was built. Here’s Ii Naomasa’s statue:

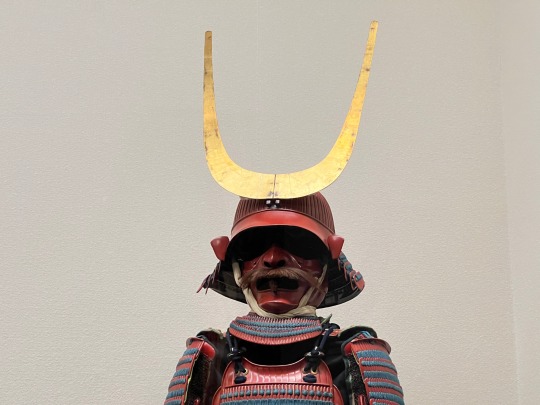

The castle has a museum; unlike the museum at Nagahama Castle, there were English translations accompanying the exhibits, so I spent a good deal of time there. They actually had the banner of the Ii clan that was used at Sekigahara, as well as examples of the famous red armor worn by the Ii samurai:

Mitsunari’s statue is in a beautiful little forested area on the path leading to Ryōtan-ji, a Buddhist temple that goes back to the 8th century and has been the family temple of the Ii clan for 40 generations. I can’t find any information as to how old the statue of Mitsunari is or who had it built or how that particular spot was chosen; perhaps it was a member of the Ii clan who felt a bit more charitably towards Mitsunari’s memory than Naomasa. I’d love to be able to find out more about this. I took a picture of the plaque on the side of Mitsunari’s statue but I can’t read it. Anyway, I just found it comforting that this tribute to him was placed in such a nice, tranquil spot, surrounded by trees, flowers, and birds. (More pics here.)

Continuing with my Mitsunari theme of the second half of this trip, I made a short trip back to Nagahama today to see the statue of his first meeting with Hideyoshi, which I didn’t know existed when I was in Nagahama the other day to see the castle and Lake Biwa. (Yes, I’m enough of a fangirl to take a train ride to see a statue. I’ve done far more over my historical obsessions in the past.) (More pics of the statue are here.)

I wonder if I’d ever be able to adjust to the huge crowds in Kyoto, especially at Kyoto Station, if I were to live here for a year or two, or if I would just be steadily driven insane by them. I’ve thoroughly enjoyed this trip overall but I’m definitely over having to navigate through massive hordes of people at the station, it sends my anxiety through the roof.

I had to buy an extra bag to be able to take home all the stuff I bought (mostly clothes and books. So many books. ☠️☠️). I’ve always tried to avoid having to check bags because I’m paranoid about my stuff getting lost, but it can’t be avoided this time, so, fingers crossed I get my bag back on the other end. I fly out tomorrow, and it’s going to be a very long travel day.

I don’t know if I’ll ever get to come back to Japan—I’m certainly going to try—but I’m definitely going to be working on my Japanese in the meantime. You can get pretty far with very little, but if I’m able to come back again I’d like to be a lot more proficient than I was this time.

Thanks to those of you who’ve been reading these posts, I hope you found at least some of it interesting and potentially helpful if you ever plan to visit Japan yourself someday. ^^

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Statue depicting the first meeting between Toyotomi Hideyoshi and teenage Ishida Mitsunari. The traditional story is that Hideyoshi was on his way back to Nagahama castle from a hunt and stopped at a temple in the area to rest, and young a Mitsunari served him three cups of skillfully prepared tea. According to the (possibly apocryphal) story, Hideyoshi was so impressed by the boy that he decided to take him on as a page on the spot. The statue is located just outside of Nagahama Station.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Statue of Ishida Mitsunari in Hikone, Shiga.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

My first trip to Japan - Day 9 & 10

On Saturday I decided I’d visit Kinkaku-ji (not to be confused with Ginkaku-ji). Took the subway up to Kitaōji station and boarded a bus with a bunch of other tourists for the temple. This was my first inner-city bus ride and it wasn’t my cup of tea to be honest. It wasn’t long before we were all jam-packed together like sardines, yet somehow more people kept getting on at each stop along the way. (I did not take the bus on the way back.)

We arrived at Kinkaku-ji a few minutes before opening time, to find several busloads of school kids in line in their uniforms. I didn’t think school groups would be something I’d need to worry about encountering on a Saturday, but apparently weekend school trips are a thing here. Between the hordes of students and the horde of tourists, the crowd size was pretty immense as the temple opened. This was the first experience I’ve had at a popular tourist site where the crowd size pretty much ruined it for me. The temple itself was gorgeous, as was the surrounding area, and I was able to get some great pics of the Golden Pavilion, but it was simply impossible to just be able to really stop and take it in properly and just appreciate its beauty with the non-stop human wave and all the noise it created. I stopped to have some matcha ice cream from one of the vendors near the bus parking area, and made my way out of there.

From Kinkaku-ji I went on foot down to Daitoku-ji, a Zen temple complex northwest of the Imperial Palace. One of my reasons for wanting to visit this was that Mitsunari’s remains were actually buried at one of the sub-temples here, Sangen-in, which Mitsunari co-founded in 1589. I wasn’t able to see Sangen-in during my wanderings, unfortunately; it isn’t open to the public most of the time. Daitoku-ji was also where Toyotomi Hideyoshi was taught the art of tea by the famous tea master, Sen no Rikyū. It was frequented by many of the most famous elite samurai of the Sengoku period, including all three of the “Great Unifiers,” Oda Nobunaga, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, and Tokugawa Ieyasu.

Daitoku-ji was a therapeutic experience after the chaos at Kinkaku-ji though. I had encountered very few people and no large tourist groups at all. Several of the sub-temples were open to the public and for a small fee you were permitted to go in, take off your shoes, and explore at your own pace, and photography was allowed in most areas. Some of these sub-temples go back over 500 years. I visited Ryogen-in, Kohrin-in, Zuiho-in, and Obai-in (there are over twenty sub-temples at Daitoku-ji). Hideyoshi and Ieyasu once played chess in Ryogen-in, and Obai-in was founded by Hideyoshi under Nobunaga’s orders to serve as a burial place for Nobunaga’s father. The sub-temples are all very simple and tranquil, with Zen rock gardens of varying sizes and symbolism.

On Sunday I took the train to Nagahama, to see Nagahama Castle and some of Lake Biwa. The castle is a reconstruction and the inside of it is a museum. Unfortunately none of the displays had any translations available so I couldn’t get as much out of it as I’d hoped. The castle was built by Hideyoshi in 1575-6, and this area is supposed to be where he first met young Ishida Mitsunari (then called Sakichi). The top floor of the museum/castle is an observation deck, so I got some lovely views of the entire area.

After visiting the castle I decided on a whim to go several stops down the Hokuriko Main Line to Yogo and walk to the Shizugatake battlefield. This ended up being a pretty grueling trek up a mountain, but I made it to the top and got to take in the views of Lake Biwa and Lake Yogo below. There is also a statue of a sitting samurai warrior on the mountaintop, but I haven’t been able to find out if it’s supposed to represent a specific historical figure or not.

There was supposed to be a chair lift service available to take people up and down the mountain, but I was not able to find it. It would’ve been nice; my legs were thoroughly shot by the time I made it back to the Yogo train station. The views from which are really nice:

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Views of my hike to the top of Mt. Shizugatake. It was the site of a decisive battle between Toyotomi Hideyoshi and Shibata Katsuie in 1583. It was a pretty grueling trek but the views at the top were breathtaking. The mountaintop straddles Lake Biwa and Lake Yogo.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kinkaku-ji (Golden Pavilion), Kyoto.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Flowers at Daitoku-ji, Kyoto.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

My first trip to Japan - Day 7 & 8

What should’ve been a roughly 90-minute trip by train from Kyoto to Sekigahara ended up taking me about three hours because of my misunderstanding of the Shinkansen system. Unaware that there were three different categories for the Tokaido line (Nozomi, Hikari, and Kodama), and that only one of these (Kodama) actually stops at all the stations along the way, I innocently hopped on the Nozomi. So, instead of being able to transfer at Maibara as intended, I found myself going to Nagoya, and by the time I realized my mistake it was too late. Trying to explain the situation at the help desk at the Nagoya station so I could get the fare adjusted and buy the correct ticket was not really something I was capable of with my limited Japanese; fortunately the worker was able to use a translator app to help get me squared away. I was able to stop at Sekigahara Station itself.

When you exit the station, there’s a little gift shop with the Tokugawa and Ishida family crests overhead. Sekigahara is a small rural town (roughly 7,000 people) and imagery related to the battle is everywhere; you can scarcely turn a corner without seeing a Tokugawa or Ishida crest. The pathway leading from the station to the battlefield visitor center is lined with art of the main figures from the battle and maps showing the battle’s various phases. Examples:

I paid the entrance fee at the visitor center and was given a token to see the movie(s) about the battle. Both had English subtitles. The first of these was in a standing-only room with a giant screen in the floor for the viewers to look down at. It gave a nice overview of the political situation that led to the battle, and then illustrated how the battle played out on a large map. The second movie was a real treat though. It was in a regular seated theater but with an IMAX-style screen that wrapped halfway around the room. The movie was an immersive experience of the battle itself, complete with the floor and your chair rumbling as the mounted samurai charged the field. The animation was great and vivid and they did a really great job bringing the story to life.

At the top of the visitor center is an observation deck that provides a complete panoramic view of the whole area along with map displays to point out where key sites from the battle can be found today. Unlike its sister park, Gettysburg (where I went to college), the town of Sekigahara has grown up over most of the battlefield itself, but at least some of the key spots have been preserved, like the various encampments and the head mounds.

The head mounds (kubizuka) are one of the more macabre aspects of samurai warfare. Head-taking being a major aspect of every battle back then, after the viewing ceremony was conducted once the battle concluded, the heads would typically be buried in giant pits. There are two head mound sites at Sekigahara, one for the Western (Ishida) and one for the Eastern (Tokugawa) army. Despite being called mounds, they don’t really protrude as you might expect. The Western and Eastern mounds are pretty far apart. They aren’t as secluded as you might expect either; the Western one is adjacent to a busy street and there is a private residence right next to it.

I had a nice walk through the gorgeous countryside to see the battle commemoration site and Mitsunari’s encampment. The town is basically in a little valley complete surrounded by mountains. It was al beautiful, I would’ve loved to have explored it more thoroughly but after a few hours of being out in the heat I was pretty worn out. I honestly never thought I’d get to see this place in person though, so even despite the difficulty I had getting there it was a great experience.

Day 8 - I bought a lot of books and pretty much stayed put. My legs needed a rest. Adventures will resume tomorrow.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sekigahara - the countryside leading to Mitsunari’s encampment on Mt Sasao, and the view looking down from it. The pillar with Mitsunari’s and Ieyasu’s banners on either side is the battle commemoration marker.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

My first trip to Japan - Day 5 & 6

Day 5 started with a visit to Shimogamo-jinja, one of Kyoto’s oldest Shinto shrines, a little northwest of the Imperial Palace. I bought an omikuji (fortune slip) to dip into the water, but when the text appeared it was too blurry for my translation app to read. :/ It was a beautiful little place though, and the surrounding forest was a nice escape from the heat.

After that, it was on to the Imperial Palace. Access is only permitted to the palace grounds, you don’t get to actually go inside any of the buildings. As far as royal residences go, it struck me as surprisingly modest and underwhelming, especially compared to the old palaces of European royalty where ostentation was maximized. It made for a nice contrast with my next destination, Nijo Castle, built by Tokugawa Ieyasu after he became Shogun. For a higher ticket price, you can go inside the main palace (Ninomaru). Each room’s screens are painted with different themes meant to either impress or intimidate those visiting the Shogun with imagery symbolizing Tokugawa strength, wealth, longevity etc. Unfortunately we weren’t allowed to take photos of the building’s interior.

I had planned to visit Daitoku-ji and the onsen south of it afterwards, but I was pretty done in by the time I left Nijo.

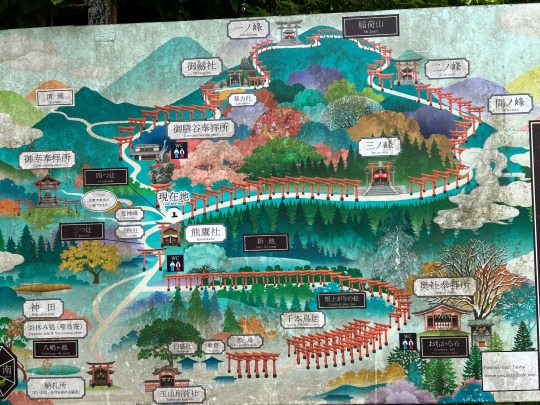

This morning the sky was cloudless and the heat gearing up to be even worse than the previous day, so I took the train to Fushimi Inari Taisha at around 6AM. There was still a fairly decent crowd, but not anywhere near as bad as it was by the time I left. I really underestimated how hard this particular trek would be, and the heat definitely didn’t help. At one point I reached a gorgeous viewpoint, and thought surely I must be close to the top… until I beheld this map of demoralization posted helpfully at the foot of the next stairway (note where the “You are here” is):

The closer I got to the mountain top, the smaller the crowd became. Most of the people who started the hike didn’t go all the way to the top. By the time I made it up there, my clothes were basically glued to my body. There’s no special viewpoint or anything at the top either, just a little shrine, so it felt a bit anticlimactic, but given that my cardio isn’t great and I don’t deal well with heat in general, it was just satisfying to be able to say I did it.

On the way up there was a guy doing the hike in a pair of leather business loafers. No idea if he made it to the top.

The heatwave doesn’t seem like it’s going to let up for the rest of my time here. :/ My tentative plan for tomorrow is to try to go to Sekigahara, which should be about 1 hour and 40 minutes by train, so I’m gonna try to get up at the crack of dawn. Pocari Sweat from the vending machines is my new best friend.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

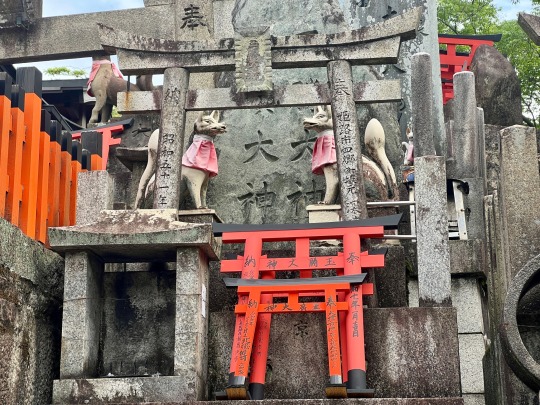

Fushimi Inari Taisha, Kyoto.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

I miss takarazuka 's Napoleon musical,When can they rehearse again?

192 notes

·

View notes