#buonarroti

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Napoleon and the Babouvists

I have chosen to translate Victor Daline’s 1970 article “Napoleon and the Babouvists”, which examines the relationship between Bonaparte and the Babouvist movement, as well as the repression they faced under his regime. Although the article dates back to 1970 and therefore lacks access to some more recent research or updated sources, it remains highly relevant and insightful.

That being said, the article notably overlooks the role of politically active women who were connected to Babeuf and who suffered repression under Bonaparte. These include Simone Evrard, Albertine Marat, and Marie-Anne Babeuf—the widow of Gracchus Babeuf—along with Madame Dufour, who lost her husband following his arrest under Bonaparte ( plus she was Jacobin woman who publicly opposed Bonaparte). Once again, women’s political agency during the Revolution is marginalized.

Furthermore, it is important to remember that repression under the Consulate was not limited to Babouvists. It also targeted liberal revolutionaries who opposed Babeuf’s ideas and were supporters of the Constitution of Year III. One such figure was Bernard Metge, an opponent of both Sieyès and the Consulate. Others were prosecuted simply for what historian Natalie Petiteau refers to as “insults and threats against the government.” There is no mention of the Dagger Plot in which the neo-Jacobin Topino Lebrun, friend of Babeuf, was executed among the "conspirators."

In addition, the article makes no mention of the well-known republican revolutionary Antonelle, a Babouvist who opposed Bonaparte and was quite possibly a member of the Philadelphes society.

Just so there’s no confusion: in his correspondence with Émile Babeuf, Buonarroti responds to someone who, by 1816, had already converted to Bonapartism. Later in life, Émile even adopted some rather reactionary positions—a surprising turn, considering that his father Gracchus Babeuf strongly disliked Bonaparte, that his mother Marie-Anne was persecuted at least twice under Napoleon, and that Émile himself was the subject of an arrest warrant during the first Malet conspiracy. since he frequented Buonarrotti, Antonelle and other opponents. He avoided arrest only because he was abroad at the time he was to be arrested.

Here is the article translated into English

The rise of Bonaparte began during Babeuf's lifetime. Did he notice it? Did he mention Bonaparte's name? Did Bonaparte attribute any importance to the Conspiracy for Equality? Did he consider it even the slightest serious threat? Ultimately, the trial at Vendôme dealt a painful blow to the Babouvist movement, yet it continued to exist nonetheless. What was the attitude toward Napoleon among the Babouvists who survived? In the vast literature dedicated to Napoleon, we find only a few scattered mentions regarding these questions, and no dedicated study is known to us. This is what determines the focus of our inquiry: what were the relations between the "last Gracchus" of the French Revolution and Napoleon?

The men of the Revolution were well-versed in the lessons of Roman history. They were also not unaware of the English Revolution, particularly the experience of General Monk. From the earliest days of the Revolution, many among them foresaw the threat of a "military government." “All revolutions end with the sword,” said the counter-revolutionary Rivarol, who was as clever as he was cynical. The fear of a general becoming “the hope and idol of the nation” was one of the main arguments used to oppose the war in 1791–1792—not only by Maximilien Robespierre, but also by the humble feudal law clerk from the small Picardy town of Roye, as early as 1790. In the draft statutes for the National Guard, the “citizen-soldier,” as Babeuf called himself, defended the principles of the most rigorous form of democracy. Commanders should be elected. To “preserve and secure the sweet fraternity, the only guarantee of liberty” between soldiers and officers, there should be no external distinctions. Uniforms and weapons were to be the same. All of these restrictions were dictated by the fear that otherwise “the colonel of our guard would behave like a sovereign.” Instead of “a detachment of free soldiers,” it would become “a herd of slaves.” ( 1) At the time, in Roye, the concern was only about “colonels.” But by the autumn of 1792, when France was at war, Babeuf clearly emphasized the threat a “military government” posed to the future of democracy. In his speech to the electoral assembly of the Somme department, he insisted that an article be added to the constitution stipulating that “a sufficient number of generals shall alternate monthly in the supreme command of the armies.” The first draft of his manuscript demanded that the supreme command “not remain in one person’s hands for more than two months.”(2)

During the insurrection of 13 Vendémiaire, Bonaparte and Babeuf (who was at the time imprisoned at Plessis) found themselves, it is true, on the same republican side. But the early signs of the rise of the “Vendémiaire general” already caused Babeuf deep concern. In theTribun du Peupleaddress to the army, published in issue 41 of his journal, he mentioned Bonaparte’s name for the first time and openly voiced his suspicions: “...Isn’t it foolish to believe that the Revolution was made for us? All right then, for our leaders. Should we not have felt flattered to see the Directory grant our General Buonaparte 800,000 francs to set up his household?” Babeuf contrasted Jourdan with Bonaparte: “It is said that the same tactics were tried on Jourdan... But it is claimed that Jourdan, being little impressed by such flattery, remains the general of Liberty and continues to deserve the trust of the People and the soldiers.”(3)

Babeuf voiced his suspicions regarding “Buonaparte” one month before his final arrest. Yet it is remarkable that even from his prison cell in Vendôme, Babeuf continued to follow Bonaparte’s actions. Upon reading the Ami des lois by Duchosal, dated 16 Pluviôse Year V (February 4, 1797), he made the following note: “Buonaparte, conqueror of Lombardy, believed this title authorized him to dictate the organization of the government of that country. He requested a list of good citizens from all classes to form a provisional general council representing the Milanese people, pending their self-constitution. There is no doubt,” the journalist adds, “that he will unite with the Cispadan peoples and form with them a one and indivisible republic.” (4) The hostile tone of this note is unmistakable. The guillotine’s blade already hung over Babeuf’s head. He had only three and a half months left to live, but he still had time to observe the transformation of the “conqueror of Lombardy” into an absolute sovereign—exactly what had frightened him as early as 1792. Babeuf had a clear vision of the danger of a “military government,” and he had time to observe how victorious generals most clearly embodied that threat.

A year later, another Babouvist, Sylvain Maréchal, spelled out that danger in very concrete terms. His actions during the final phase of the Babeuf movement remain unclear. However, his anti-Bonapartist pamphlet, Corrective to Bonaparte’s Glory or Letter to that General, written in Frimaire Year VI (between Campo Formio and the Egyptian campaign), when Bonaparte's republican reputation was still beyond doubt, does credit to Maréchal’s political insight(5). In it, Maréchal criticized Bonaparte’s Italian policy, the compromise with Austria regarding Venice, and his refusal to go to Rome. Above all, however, Maréchal feared the general’s ambition: “Bonaparte! Your glory is a dictatorship... If you allow yourself this tone in Italy when addressing the Cisalpine Directory, I don’t see what would prevent you from using the same tone one day when addressing the French Directory. I see nothing to reassure me that next Germinal, during our primary assemblies, you won’t say from your chambers in the Luxembourg Palace: People of France! I shall appoint you a Legislative Body and an Executive Directory. I see nothing to stop the general who toasts His Majesty the Emperor before toasting the French Republic from saying at the National Palace: I shall give you a king of my own choosing—or tremble. Your disobedience shall be punished.” It is true that Maréchal ended his pamphlet by softening his criticism, expressing hope that Bonaparte would contribute to the creation of a European republic led by France. But even in Frimaire Year VI, Maréchal predicted 18 Brumaire with considerable accuracy.

We will not dwell here on Marc Antoine Jullien’s attitude toward Bonaparte. Although closely associated with Babeuf in 1795, Jullien broke with the Babouvist movement well before the arrests in Floréal. At the time of his arrival in Italy, Jullien could be considered among the “conscientious Bonapartists,” although his criticism of Bonaparte’s Italian policy—serious and sharp—was quite close to the judgment expressed by Buonarroti. (6)

It is precisely to Buonarroti, one of the leaders of the “movement for equality,” and at the same time the man who knew Bonaparte closely and well from their time in Corsica, and later up to 1795 during preparations for the Italian campaign(7), that we owe the most accurate and clearest characterization of the Babouvists' attitude toward Bonaparte. Buonarroti wrote in Conspiracy for Equality: “…Through several such instances, the new aristocracy came to recognize in this general… the man who could one day offer it solid support against the people; and it was the knowledge of his haughty character and aristocratic views that led to his being summoned on 18 Brumaire, Year VIII, alarmed by the speed with which the democratic spirit was then resurfacing. Bonaparte was brought to supreme power by a sort of backward step that the 9th Thermidor, Year II, had imprinted on the Revolution… Bonaparte, by the firmness of his character and the influence of his military exploits, could have been the restorer of French liberty; an ordinary ambitious man, he preferred to strike the final blows against it: he held the happiness of Europe in his hands and became its scourge through the systematic oppression he imposed upon it.”(8)

This “diffidenza verso Bonaparte” (mistrust of Bonaparte) took root in Buonarroti well before 1795 and lasted until the end of his life (except for the Hundred Days). “Do not speak to me of the great man; he dealt the Revolution its death blow and completed to his benefit the work of iniquity that immorality and aristocracy had long since begun. He could have repaired everything; he lost everything. That is his great crime,” Buonarroti wrote to Babeuf’s son in 1828(9).

Buonarroti shared his memories of Napoleon with the Turgenev brothers, Alexander and Nikolai, in 1836, shortly before his death. These appeared in the first issue of Pushkin’s Sovremennik (“The Contemporary”): “February 16. The old man Buonarroti… had lunch at our house. He is a living chronicle of the last half-century… He characterizes many people wonderfully and tells little-known details about events and individuals. In his youth and later he knew Napoleon: in Corsica, he lived in his mother’s house and, when Napoleon came to visit her, the last night that Sub-Lieutenant Bonaparte spent in his family home, they slept in the same bed. Ever since, they quarreled at times but never reconciled. Bonaparte rose to the throne. Buonarroti, for his part, was thrown into prison.” (10)

“Never reconciled” – this phrase precisely defines not only Buonarroti’s attitude toward Napoleon but that of all the Babouvists.

On the 9th of Ventôse, Year IV, Bonaparte, as Commander-in-Chief of the Army of the Interior, personally closed the Panthéon Club. Buonarroti attributed to him not only the execution but also the initiative of this action. Three days later, on the 12th of Ventôse, Bonaparte was appointed commander of the Army of Italy. The Babouvists considered these two acts intimately connected.

At Saint Helena, Napoleon recalled these events and his encounter with Buonarroti at the time: “…After Vendémiaire, he was among the Babouvists. I had him summoned. He responded proudly. ‘That’s fine,’ I said, ‘but you have professed communist views to have the commander of Paris executed—this does not suit me, and I will have you tried by a military commission and shot.’”

Napoleon recalled this meeting with Buonarroti on January 5, 1819 (11). Whether he truly threatened Buonarroti with a military commission in 1795 is difficult to say, especially since negotiations for the “Italian mission” had occurred beforehand, evidently with Napoleon’s knowledge. But Bonaparte did indeed threaten the Babouvists with military commissions and execution during the famous State Council sessions of Nivôse, Year IX, after the explosion of the so-called “infernal machine.”

As is known, two days after the explosion, during the session on 5 Nivôse (December 26, 1800), Bonaparte—who was clearly preparing to purge the revolutionary cadres—categorically affirmed the terrorists' guilt. “These are the Septemberists, the remnants of all the men of blood... This is not a royalist conspiracy nor an English plot—it is a terrorist conspiracy.”(12)

The time had come to “cleanse France”: “I am ready to serve as a tribunal on my own, to have the guilty appear before me, interrogate them, judge them, and execute their sentence…” In that same speech, he declared: “There will be no avoiding blood. We must shoot… fifteen to twenty people, expel two hundred, and take advantage of this occasion to cleanse France.”

According to Roederer and Thibaudeau, this scene stunned the Council of State, which—according to Thiers—was “frozen in surprise and fear.”(13) A heavy silence followed, broken only by Admiral Truguet. The Brumairians were willing to judge the perpetrators of the attack severely, but the prospect of summary justice for a whole group of active revolutionaries alarmed them. Where would Bonapartist terror end?

Among those who took heed of this warning was even the most devoted of Bonapartists—Pierre-François Réal, former comrade of Chaumette and Hébert at the Paris Commune, defender of the Babouvists at Vendôme, and future count of the Empire.

Taken aback by such resistance, Bonaparte flew into a rage. According to Roederer, he turned pale, his voice broke, and he completely lost control of himself, even interrupting Cambacérès(14).

It is striking that when calling for extraordinary measures against terrorists, Bonaparte always recalled the Babouvists. In all versions of his speech that reached us, and in all accounts by those present, Babeuf is invariably mentioned: “The tribunal will conclude everything in five days. I have a dictionary of the Septemberists, the conspirators, Babeuf and others who played their part during the worst moments of the Revolution.”(15)

Transported by fury, Bonaparte threatened Council members: “Don’t you know, gentlemen of the Council, that except for two or three, you are all considered royalists?... Shall I send Citizen Portalis to Sinnamary, Citizen Devaisne to Madagascar, and then form a council à la Babeuf [emphasis ours]? Come now, Citizen Truguet, don’t try to fool me… They wouldn’t spare you either; and you could tell them you defended them today at the Council of State, but they would sacrifice you like me, like all your colleagues.”(16)

Enraged, Bonaparte suspended the session.

Meanwhile, it became clear that the terrorists had no part in the Rue Nicaise explosion. At the Council session of 11 Nivôse, Bonaparte no longer linked the attack to anti-terrorist measures. “The government has its convictions, but without proof it cannot impute the attack to these individuals. They are being deported for September 2, May 31, Babeuf’s conspiracy [emphasis ours], and all that has happened since.”(17)

At this session, Réal and others again raised objections to the list of people to be deported, drawn up by Fouché(18). Bonaparte held firm. The proscription list came into effect on 14 Nivôse.

This list of 130 names included well-known Babouvists like Rossignol and Massard, leaders of the Babouvist military organization; “agents” from the Paris districts: Mathurin Bouin, Claude Fiquet, Mennessier; individuals indicted in the Vendôme trial and others linked to the Babouvist movement: Convention member Choudieu, Félix Lepeletier, Marchand, Chrétien, Lamberthé, the Babouvist literature publisher Brochet, Cordas, Dufour, Vatar, Goulard, Paris, the Belgian Fyon, Vanneck, and many others.

Seventy people were deported to the Seychelles. Some remained on Anjouan Island in the Comoros, where, within two weeks, twenty-one of them—including Rossignol and Bouin—died of disease. According to survivor Lefranc, Fescourt, author of a book on the deportees’ fate, reports Rossignol’s final words: “I die overwhelmed by the most horrible pain; but I would die content if I could know that the oppressor of my homeland, the author of all my misfortunes, suffered the same torments and pains.”(19)

Hostilities with England prevented the deportation of the second group of terrorists. Only in 1803 were 40 people sent to Cayenne, where a third died in the first year. However, the police failed to arrest everyone sentenced to deportation. Claude Fiquet and Menessier, former administrators of the Paris Commune police, as well as Babouvists Didier, Marchand, Fyon and others escaped. Some managed to flee, including Fournier l’Américain, a close associate of Babeuf in Paris in 1793 (20).

The arrests of Floréal, the repression at Grenelle, the Vendôme trial, and finally the list of 14 Nivôse dealt heavy blows to the Babouvists. But did Napoleon completely suppress them? Was opposition to the Consulate and Empire limited to military and ideological circles? Who created the Philadelphes organization, and did it even exist? Was Buonarroti truly connected to it and involved in General Malet’s two plots? These questions demand further research.

Fifty years ago, a historian as capable as Léonce Pingaud could still consider the Philadelphes a fabrication by Charles Nodier, and General Malet a “loner” with occasional accomplices(21) . Regarding Malet, E.V. Tarlé held the same opinion. However, later studies confirmed the Philadelphes' existence. Destrem’s hypothesis—that during his deportation to Île de Ré, Félix Lepeletier became linked to Colonel Oudet, its commander, and became involved with the Philadelphes—is more than plausible (22). Lepeletier escaped in 1803.

Andryane’s testimony about Buonarroti’s links to General Malet(23) finds strong confirmation in Buonarroti’s Elenco dei grandi uomini, published by A. Saitta, where Oudet is praised as “founder of the Philadelphes society instituted against Bonaparte’s tyranny,” and Malet as “a passionate republican-democrat who, from the depths of prison, rose up against imperial despotism to restore the people to their rights.”(24)

Buonarroti was the living link connecting the movement of the Equals to the resistance against “imperial despotism.” Other evidence exists of Babouvist activity(25). Napoleon did not succeed in breaking this “Macedonian phalanx”—chief among them Buonarroti himself.

At Saint Helena, he paid tribute to his adversary. Let us recall these words, which J. Godechot was the first to highlight(26) . According to a note by Bertrand dated 1819: “Napoleon reads Le Moniteur. He reads the Babouvist trial and finds it interesting… Buonarroti was a man of great talent… He was a friend of the common good, a leveler. I had him released. I don’t believe Buonarroti ever thanked me, or ever addressed me. Perhaps it was pride on his part, perhaps he thought himself too insignificant. Maybe I forgot he wrote to me—I was so busy then! Buonarroti was a leveler so far from my system that it’s possible I paid no attention. Yet he could have been very useful in organizing the Kingdom of Italy. He would have made a very good professor. He was an extraordinarily talented man, a descendant of Michelangelo, an Italian poet like Ariosto, writing French better than I did, drawing like David, and playing the piano like Paisiello.”(27)

This judgment seems objective and impartial. What a pity Napoleon expressed it so late…

Victor Daline

(1) Archives IML, fonds 223, inv.I, number 134

(2) Archives IML, fonds 223, inv.I, number 333

(3) Le Tribun du Peuple, number 41, page 276, “Adresse du tribun du peuple à l’armée” 10 Germinal

(4) Archives IML, fonds 223, inv.I, number 473

(5) Cf. A. Mathiez, “An anti-Bonapartist pamphlet in Year VI. The predictions of Sylvain Maréchal”, La Révolution française, 1903, vol. XLIV, pages 249–255; M. Dommanget, Sylvain Maréchal (1950). The text of the pamphlet was reprinted in 1913 by O. Karmin in the Revue historique de la Révolution française.

(6) Cf. V. Daline, “M.A. Jullien after 9 Thermidor”, Annales Historiques de la Révolution Française, 1966, no.185

(7) J. Godechot, Les commissaires aux armées sous le Directoire (1941), vol. I; A. Saitta, Filippo Buonarroti (Rome, 1950–1951)

(8) F. Buonarroti, Conspiration pour l’égalité (Paris, 1957), vol. I

(9) Archives départementales de la Somme, F 129/106, “Brussels, 30 July 1828”. It is interesting to compare Buonarroti’s opinion to the attitude of Ch. Fourier toward Napoleon (cf. Rob. C. Bowles, “The reaction of Ch. Fourier to the French Revolution”, French Historical Studies, Vol. I, No. 3, 1960). “Fourier was particularly disappointed by Napoleon, for he acknowledged that this conqueror was a remarkable genius and held the key to universal harmony and happiness.”

(10) Sovremennik, 1836, vol. I, pp. 275–276, “Paris, A Russian’s Chronicle”. See also A.I. Turgenev, Chronique d’un Russe. Journaux (Moscow, 1964)

(11) General Bertrand, Cahiers de Sainte-Hélène, 1818–1819 (Paris, 1959), page 225

(12) P.L. Roederer, Œuvres (1854), vol. III, p. 355

(13) A. Thiers, Histoire du Consulat et de l’Empire (1845), vol. I, p. 255. Cf. Thibaudeau, A.C., Mémoires sur le Consulat par un ancien conseiller d’État (1827), ch. II “Explosion de la machine infernale”. Also Histoire de la France et de Napoléon Bonaparte, vol. II (1835), page 46

(14) Roederer, op. cit., p. 357

(15) Roederer, op. cit., p. 359

(16) Thiers, op. cit., p. 257

(17) Thibaudeau, Mémoires…, page 47. Cf. Thiers, op. cit., page 266

(18) Desmarets, in Témoignages historiques sur quinze ans de haute police (1833), pp. 48–49, probably based on Réal’s account, reproduced this scene: “Napoleon: Who made those lists? There are still enough of those incorrigible remnants of Babeuf’s anarchy in Paris. Réal: Precisely. I’d be on that list too… if I weren’t a Councillor of State — I who defended Babeuf and his co-defendants at Vendôme.”

(19) Fescourt, Histoire de la double conspiration de 1800: contre le gouvernement consulaire, et de la déportation qui eut lieu dans la deuxième année du consulat; contenant des détails authentiques et curieux sur la machine infernale et sur les déportés (1819). Chateaubriand in his Mémoires d’outre-tombe mentions this same phrase by Rossignol and Fescourt’s book

(20) Cf. J. Destrem, “Les déportations du Consulat”, Revue historique, May–June 1878

(21) L. Pingaud, La jeunesse de Ch. Nodier. Les Philadelphes (1919): “Oudet is the fictitious creation of a whimsical imagination” (page 179) “Malet… only ever had occasional accomplices; a solitary figure driven by his passions or personal grudges, and not acting on behalf of any known association” (pages 170–171)

(22) Destrem, op. cit., page 94

(23) Cf. Andryane, Souvenirs de Genève

(24) Cf. A. Saitta, op. cit., vol. II, page 45. See also A. Lehning, “Buonarroti and his internal secret societies”, International Review of Social History, 1956, no. 1

(25) Cf. J. Dautry, “Saint-Simon et les anciens babouvistes de 1804 à 1809”, Babeuf et Buonarroti. Pour le deuxième centenaire de leur naissance. Also by the same author: “La tradition babouviste après la mort de Babeuf”, Annuaire d’études françaises, 1960 (Moscow, 1961)

(26) Cf. A. H.R.F., 1952, pages 177–178: “Thus, Napoleon was more closely connected with Buonarroti before 1796 than Saitta and Galente Garrone believed”

(27) General Bertrand, Cahiers de Sainte-Hélène, 1818–1819 (1959), p. 297. Cf. ibidem, p. 255: “He finds Buonarroti’s name, admits he knew him, and says he should have used his knowledge. He was a clever man, a liberty fanatic, but sincere, a terrorist and yet a good and simple man. It seems he never changed character.” See also notes for 1816–1817: “Buonarroti… had known me in his youth. He was a talented, eloquent, honest man… He would have been very useful to me in Italy” (General Bertrand, Cahiers de Sainte-Hélène. Journal 1816–1817, pp. 177–178)

Here is the source for Victor Daline's original article in French:

#frev#french revolution#napoleonic era#gracchus babeuf#napoleon bonaparte#buonarroti#Felix Le Peletier#jacobin#françois réal#Interesting fact: Bonaparte had the Pantheon club closed a few days after Babeuf gave a speech there about his wife's imprisonment#a dire omen of the misfortunes that would befall her under Bonaparte.#sylvain maréchal#1790s#1800s

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

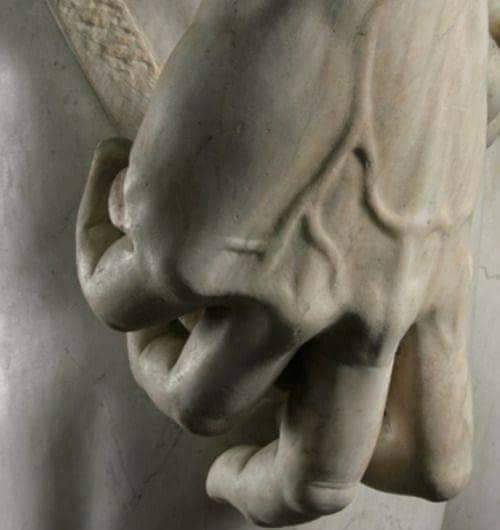

Michelangelo: Giuliano de Medici, 1526-1534.

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Piccolomini Altarpiece in the Cathedral of Santa Maria Assunta in Siena, Italy, has a statue of St Peter (1504) by Michelangelo Buonarroti.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Buonarroti - Don't Worry..You're Dead!

Da venerdì 9 maggio 2025 è disponibile sulle piattaforme digitali “Don’t worry… you’re dead!” (Overdub Recordings), il quinto singolo di BUONARROTI, estratto dal nuovo EP “KOMOREBI” di prossima uscita. “Don’t worry… you’re dead!” è un brano che si apre con un piano ascendente, quasi a suggerire una veste classica. Ma l’ingresso deciso di batteria e basso riporta subito il pezzo su coordinate…

0 notes

Text

Pese a su fama de hombre solitario y colérico, Miguel Ángel Buonarroti supo ganarse el favor de poderosos mecenas y entabló relaciones profundas con figuras como Vittoria Colonna.

#national geographic#miguel angel#buonarroti#italia#arte#historia#vittoria colonna#michelangelo buonarroti

0 notes

Text

"L'Enigma Michelangelo: Il Genio, il Falsario" di Daniela Piazza. Recensione di Alessandria today

Un’avvincente caccia al tesoro rinascimentale, tra arte, potere e inganni nel cuore dell’Italia del XV secolo.

Un’avvincente caccia al tesoro rinascimentale, tra arte, potere e inganni nel cuore dell’Italia del XV secolo. Recensione:Il romanzo “L’Enigma Michelangelo: Il Genio, il Falsario” di Daniela Piazza, pubblicato il 10 settembre 2014, ci trascina nell’Italia del Rinascimento, dove il giovane Michelangelo Buonarroti, a soli vent’anni, si ritrova immerso in una serie di eventi che cambieranno il…

#1494#Arte#Baldassarre#Bologna#Borgia#Buonarroti#Caccia#Caterina#Cesare#Cultura#Cupido#Daniela#dormiente#falsario#Firenze#genio#Il#Intrighi#Italia#Italiana#L&039;enigma#Medici#mercante#Michelangelo#Narrativa#Piazza#Potere#Rinascimento#rizzoli#Romanzo

0 notes

Text

Did you know that such basic sacraments as communion and baptism were borrowed from the religions of the ancient peoples of Syria and Asia Minor, who worshiped the sun god Mithra. The feast of the Nativity of Christ on December 25 and the weekly Sunday were also borrowed from this ancient religion.😳

Michelangelo Buonarroti "The Lamentation of Christ" or "The Vatican Pieta."

#Michelangelo#Buonarroti#michelangelo#The Lamentation of Christ#The Vatican Pieta#communion#baptism#Nativity of Christ#sun god Mithra#god#sun

1 note

·

View note

Text

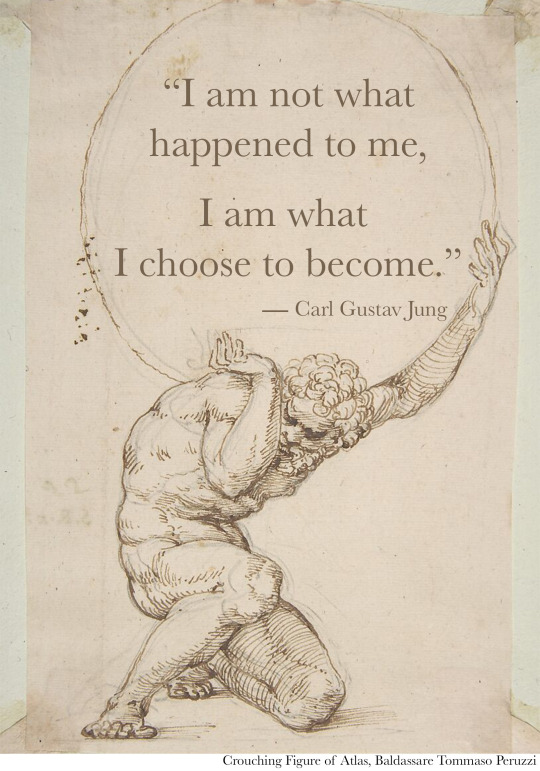

“I am not what happened to me, I am what I choose to become.” ― Carl Gustav Jung

Drawing: "Crouching Figure of Atlas" by Baldassare Tommaso Peruzzi

#albert camus#poetry#franz kafka#classical quotes#literature#booklr#quotes#classics#sylvia plath#classical literature#renissance#sandro botticelli#leonardo da vinci#michelangelo buonarroti#carl jung#archetypes#freidrich nietzsche#the will to power#thus spoke zarathustra#psychology#lit#classic literature#literary quotes#excerpts#fragments#letters#existensialism#jane austen#charlotte bronte#book quote

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

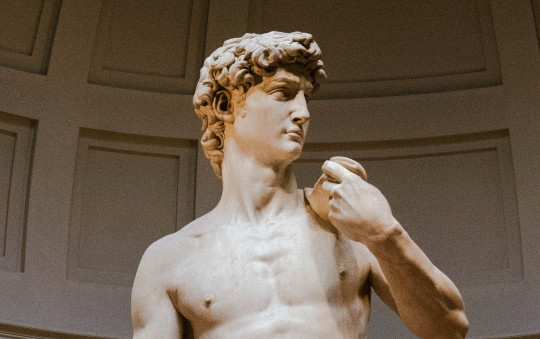

David, Michelangelo. Galleria dell'Accademia, Firenze

My Instagram acount

#my photography#my pics#florence#italy#Sony A7II#digital photography#dark academia#dark acadamia aesthetic#museum#museum photography#firenze#florence italy#art gallery#museums#photographers on tumblr#photography#original photographers#dark aesthetic#picoftheday#my pictures#my photos#rennaissance#rennaisance art#michelangelo buonarroti

108 notes

·

View notes

Text

The sorrow of a Mother who knew. The Madonna della Pietà, Michelangelo. 1499. Saint Peter’s Basilica, Rome. Photographer @enduringhosts 04/01/2025.

#rome#vatican#pieta#michelangelo buonarroti#rinascimento#renaissance#marble statue#sculpture#art history#art#photography#virgin mary#marble sculpture

102 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Mysteries of Marie-Anne Babeuf, Wife of Gracchus Babeuf, and My Theories About Her

I have previously published several articles about this revolutionary woman, and you can find them all here (these sources concern the life of Gracchus Babeuf): https://www.tumblr.com/nesiacha/768437156389715968/in-honor-of-gracchus-babeufs-recent-anniversary. This revolutionary woman, a true political right-hand to Gracchus Babeuf, was known for her strong character, leaving many mysteries surrounding her.

Marie-Anne Victoire Langlet came from a poor family of servants at the castle and was slightly older than her husband. Her father was a hardware merchant. When Gracchus Babeuf met her, he was certain he would marry her and was so in love that he wrote to lawyer Mouret on July 21, 1781: "I advise you not to be too sensitive to the pleasures of your age. Love makes those who experience it pay dearly, and often the moment when one kneels before the altar is the one that determines the fate of an entire life; do not be too angry with the circumstances, but never cease to respect yourself." It was a marriage of love, revolution, and mutual support until the end.

Some historians claim that despite her political effectiveness, her advice, and her knowledge of numbers, she was illiterate and had to have her letters written for her, read by her trusted friends or her son, as she was poor and had no access to education. However, Jean-Marc Schiappa argues that she was not illiterate. According to him, she could read and even write, though her handwriting was erratic, like that of many poor women of the time. Schiappa states that when Gracchus claimed his wife couldn’t read or write, it was in vain, aimed at protecting her during the repression (which would not be enough—she would face governmental repression during Gracchus’s life and even for years after his death, especially under the Napoleonic regime). This hypothesis is interesting, though it does not discredit other theories suggesting that Babeuf's wife was indeed illiterate. There is nothing better than a good debate of solid theories among historians or even researchers.

Jean-Marc Schiappa writes again, like other historians, that she was an effective political advisor to her husband, united with him, loving him, and endowed with a strong character. Virtually no divergence in their difficult struggles, their exchanged letters were full of love, advice, and tenderness. Schiappa explains that she played a more significant role than simply managing her husband’s subscriptions and printing his works. She advised him, showing great cunning, and advised him to be clever when he was imprisoned again during Year III. In January 1795, she protected her husband by telling the police she had not seen him. She would be arrested for two days under the Directory, and her allies René Lebois and René Vatar (the latter would die in exile under the Napoleonic regime, if I understand correctly) protested against this.

She managed clandestine communication under the guise of a mother of a family (she took good care of her children). This shows she was a trusted figure within the Babouvist circle, capable of deceiving the police and displaying initiative and intelligence, according to Jean-Marc Schiappa. There seems to have been a brief moment of tension between the Babeufs, according to Advielle, but this letter is neither signed nor dated, and there’s a stern phrase from Gracchus: "We are no longer tender at all," although this seems to be the only tension during their years of revolutionary struggle. She told her husband she would never abandon him. She even tried to help him escape during his last incarceration to prevent his execution, but this failed (she walked miles to support her husband, pregnant and about to give birth, trying to organize his defense with others, alongside Teresa Poggi, Buonarroti's companion).

One aspect that deepens the mystery of Marie-Anne Babeuf is that no physical description of her exists. In fact, physical descriptions of her were made when she was imprisoned at the La Petite-Force prison during Year IV. However, these documents were destroyed because she was never convicted. One can imagine a similar scenario when she was arrested by the Napoleonic police in 1801 and underwent brutal questioning in 1808. What a shame. I would have liked to know, for example, what her relationship with Albertine Marat, Marat's sister, was like, as she had good relations with Gracchus Babeuf. It is certain they met, as Albertine gave Gracchus a letter to publish against Stanislas Fréron, as you can see here https://www.tumblr.com/nesiacha/767708756031176704/i-am-so-exhausted-that-i-only-now-realize-that-i?source=share . At this time, Marie-Anne Babeuf was in Paris, collaborating faithfully with her husband. I would also have liked to know her relationship with the Duplay family. Perhaps some members of the Duplay family never spoke of her to protect her after all the misfortunes she had suffered and the suffering of her surviving son, Émile (I’m thinking specifically of Elisabeth Le Bas, for example). Perhaps they didn’t get along, despite the common cause and Gracchus becoming a fervent admirer of Robespierre again after having violently criticized him, but I don’t know.

Why did Joseph Fouché target the widow Babeuf?

I will now propose a few theories explaining why Joseph Fouché, Minister of Police, targeted the widow Babeuf twice. It is certain that in 1801, he included her name in the list of Jacobins to arrest, and then he authorized an arrest warrant for her son, Émile Babeuf (Émile escaped arrest because he was working abroad). Marie-Anne Babeuf underwent quite a harsh moral interrogation, and her papers were seized, although they were innocent of the Malet conspiracy, I talk about it in a personal and not very important post https://www.tumblr.com/nesiacha/770322937812336640/one-of-the-creepiest-things-among-the-many.

Theory 1: Opportunistically, Fouché wanted to show Bonaparte that he had no mercy for the Jacobins (after all, Fouché was in a delicate position), especially after the attack on Rue Saint-Nicaise, which I briefly discussed here and here. Bonaparte had not forgotten the Babouvistes, so the widow Babeuf was a logical target. But why attack her and her son again in 1808, even though this episode of the Malet conspiracy exposes Fouché’s limits as Minister of Police, according to Jean Tulard? I don’t know. I think after that it's because Emile had contacted Buonarroti so maybe for a verification. Honestly I think the first hypothesis is the most plausible.

Theory 2: Gracchus Babeuf and Fouché worked together at one point (more precisely, Fouché manipulated Gracchus before Gracchus realized his true nature and showed him the door, as you can see here). It is highly probable, if not nearly certain, that Fouché met Gracchus's wife and saw her political talents, activism, her combative nature in the underground, and her ability to evade the police, since she was always by Gracchus’s side. As a close ally to her husband, she had been involved in underground activities, and Fouché may have suspected her of continuing anti-Napoleonic actions. Furthermore, her associations with neo-Jacobins and opponents like René Vatar and Félix Le Peletier might have fueled Fouché’s suspicion. Perhaps these suspicions were justified, given the strong character of the widow Babeuf. In 1808, he may have wanted to verify this. Fouché was just acting as a "good" Minister of Police to fight the Empire’s opponents (even though again, why target her son? Perhaps as a warning or because he was beginning to want to become a revolutionary activist apart).

Theory 3: The third theory is the one I believe the least but after discussion with friends I decided to put it. We know that Fouché liked to keep all documents concerning him at his disposal, including delicate documents about others, and he liked to destroy traces of himself (including information about his own mother, for which there is no trace). In fact, in his last days, he burned papers containing important correspondence, notably with Condorcet, Robespierre, Collot d'Herbois, and others. We know that Gracchus Babeuf had to produce documents about him, especially when Gracchus considered him an ally. It’s possible that Fouché sought to recover these documents, either directly or indirectly. We also know that in Gracchus Babeuf’s final letter before his execution, he left his defense papers with his wife, recommending that they be passed to their friends. Here’s an excerpt from this letter: "Lebois announced that he would print our defenses separately. It is necessary to give my defense as much publicity as possible. I recommend to my wife, my dear friend, not to give to Baudouin, to Lebois, or to others, any copy of my defense, without having another accurate one kept with her, so as to ensure that this defense is never lost" as you can see here https://www.tumblr.com/nesiacha/765954409563897856/last-letter-of-babeuf-before-his-execution?source=share .

What is the connection? Gracchus Babeuf may have entrusted his wife with other important papers, and Joseph Fouché might have wanted to recover them, either indirectly, or he wanted to verify their contents to see if they concerned him directly. So what to do if Marie-Anne Babeuf surely didn’t want anything to do with him anymore? He could commit a burglary ( Fouché clearly demonstrated that he often acted outside the law in ways that are difficult to understand. I am currently examining the Clément de Ris case more closely through the papers of Clément de Ris to see if the hypothesis of historian Alain Decaux aligns with that of Waresquiel, which highlights the extent to which Fouché could be unscrupulous at times as you all know which is an understatement ). However, Marie-Anne Babeuf would have quickly deduced who it was or would have her suspicions. It is important to say that the Babeufs had important links with François Réal , who had an important role in Bonaparte’s government (François Réal, one of the few with Admiral Truguet, openly protested against Bonaparte when Napoleon ordered the repression of the Jacobins in 1801 during a council). So she might have informed Réal, who would tell Bonaparte, which would have been problematic.So burglary is out of the question . On the other hand, when someone is arrested or interrogated, their house can be searched legally. This is partly why he included Marie-Anne Babeuf's name in the list of Jacobins to be arrested in 1801—to thoroughly search her home and the homes of her friends to try to recover her papers. Perhaps Fouché was not satisfied with what he found in 1801 and took the opportunity to try again and search her home in 1808. Proof is that her papers were confiscated, even though they were returned to her two days later. So, Fouché targeted Marie-Anne Babeuf to verify that she didn’t have any compromising documents about him, or to try to get his hands on any papers Gracchus might have left, which could be important for him.

Theory about Marie-Anne Babeuf's Date of Death

Finally, the date of Marie-Anne Babeuf’s death remains a great mystery, but I will propose a hypothesis. In my opinion, she surely died after her friends and comrades, Félix Le Peletier and Philippe Buonarroti. Indeed, Félix Le Peletier was very close to the Babeufs, almost a family member, a mentor, a protector and it seems hard to believe that there would not have been a written account if he had lost one of his closest friends and a companion in struggle. Buonarroti, despite his suspicions about Émile’s Bonapartist leanings, also likely would have mentioned Marie-Anne’s passing, as she had been his ally.

One source says she was alive in 1842, according to Advielle, quoted by Dommanget and Legrand, because she supposedly signed as the widow Babeuf. However, given her spelling issues, it is likely that it was actually Émile Babeuf's wife (Émile passed away in 1842). Personally, I believe Marie-Anne Babeuf died between 1841 and 1842, because otherwise, I think Albertine Marat would have mentioned her death, since Marat's sister died in 1841. I say this because it would have been horrible for her to lose two daughters (one died from a scalding accident, the other from malnutrition under the Directory) and later two sons (Camille in 1814 by suicide at the time of the Allies' entry into Paris—some say from depression, others say from "patriotism", and Caius Babeuf, who died at 17 in the defense of Paris in 1814). It would have been so painful if she had also lost the last son she had left after everything she had suffered.

My theory is that she died between 1841 and 1842.

Émile Babeuf's Lie about His Mother's Origins

Émile Babeuf lied about his mother’s origins, claiming she was not a maid: "It is false that my mother was a maid," and that she was, according to him, "the friend of a noblewoman who had taken her out of the convent." Why did Émile Babeuf lie? To protect his mother from persecution by inventing more important origins to try to deter their enemies from attacking them? Or was it to protect himself, given his activism (he joined Bonaparte’s Hundred Days and was involved in opposition to the Bourbons) and the subsequent persecution he faced under the Restoration? Or did he simply want to glorify his parents?

A Final Word from Jean-Marc Schiappa:

"Like Hecuba, the Queen of Troy, she had the misfortune of seeing almost all of her children (including two young daughters) die. There was a Greek tragedy in her fate. Always poor, always suffering, always unknown, always a victim, but always present, and always faithful... An admirable woman, she deserves much more than these few lines, but history has left us with few elements to better describe her. How can we not regret her?"

But in my view, she was far more than faithful—she was a fighter, just like her husband. Just as Camille Desmoulins would not have been as effective without Lucile Desmoulins, Antoine-François Momoro without Sophie Momoro, the Marquis de Condorcet without Sophie de Grouchy, Philippe Le Bas without Elisabeth, Jean-Paul Marat without Albertine Marat, his partner Simone Evrard, and her sister Catherine, Gracchus Babeuf would not have made it as far without his faithful political right-hand, Marie-Anne Babeuf, who never ceased to fight, surely even after Gracchus’s death.

#frev#french revolution#napoleonic era#babeuf#marie anne babeuf#joseph fouché#albertine marat#napoleon bonaparte#1800s#history#france#theories#felix lepeletier#buonarroti#women's history#women in revolution

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Emil Gataullin

67 notes

·

View notes

Text

Michelangelo Buonarroti (Italian, 1475-1564) Cleopatra, ca.1532

#Michelangelo Buonarroti#Michelangelo#Italian art#italian#italy#cleopatra#cleo#1532#1500s#drawing#art#fine art#european art#classical art#europe#european#fine arts#europa#mediterranean

152 notes

·

View notes

Text

Buonarroti - Homesick

Da venerdì 11 aprile 2025 è disponibile sulle piattaforme digitali “HOMESICK” (Overdub Recordings), il quarto singolo di BUONARROTI, estratto dal nuovo EP “KOMOREBI” di prossima uscita. “Homesick” è un brano che unisce atmosfere post-rock con un tocco di nostalgia degli anni ’80. L’effetto delay della chitarra d’apertura si trasforma in un arpeggiatore sintetico, creando un’esperienza…

0 notes

Text

Battle of the Centaurs, Michelangelo Buonarroti, about 1492

#art history#art#italian art#aesthethic#15th century#centaurs#bassorilievo#sculpture#marble#michelangelo buonarroti#lapiths#greek mythology#ancient greece#rinascimento#casa buonarroti#homoerotic art#battle

328 notes

·

View notes

Text

David di Michelangelo

464 notes

·

View notes