#felix lepeletier

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The Mysteries of Marie-Anne Babeuf, Wife of Gracchus Babeuf, and My Theories About Her

I have previously published several articles about this revolutionary woman, and you can find them all here (these sources concern the life of Gracchus Babeuf): https://www.tumblr.com/nesiacha/768437156389715968/in-honor-of-gracchus-babeufs-recent-anniversary. This revolutionary woman, a true political right-hand to Gracchus Babeuf, was known for her strong character, leaving many mysteries surrounding her.

Marie-Anne Victoire Langlet came from a poor family of servants at the castle and was slightly older than her husband. Her father was a hardware merchant. When Gracchus Babeuf met her, he was certain he would marry her and was so in love that he wrote to lawyer Mouret on July 21, 1781: "I advise you not to be too sensitive to the pleasures of your age. Love makes those who experience it pay dearly, and often the moment when one kneels before the altar is the one that determines the fate of an entire life; do not be too angry with the circumstances, but never cease to respect yourself." It was a marriage of love, revolution, and mutual support until the end.

Some historians claim that despite her political effectiveness, her advice, and her knowledge of numbers, she was illiterate and had to have her letters written for her, read by her trusted friends or her son, as she was poor and had no access to education. However, Jean-Marc Schiappa argues that she was not illiterate. According to him, she could read and even write, though her handwriting was erratic, like that of many poor women of the time. Schiappa states that when Gracchus claimed his wife couldn’t read or write, it was in vain, aimed at protecting her during the repression (which would not be enough—she would face governmental repression during Gracchus’s life and even for years after his death, especially under the Napoleonic regime). This hypothesis is interesting, though it does not discredit other theories suggesting that Babeuf's wife was indeed illiterate. There is nothing better than a good debate of solid theories among historians or even researchers.

Jean-Marc Schiappa writes again, like other historians, that she was an effective political advisor to her husband, united with him, loving him, and endowed with a strong character. Virtually no divergence in their difficult struggles, their exchanged letters were full of love, advice, and tenderness. Schiappa explains that she played a more significant role than simply managing her husband’s subscriptions and printing his works. She advised him, showing great cunning, and advised him to be clever when he was imprisoned again during Year III. In January 1795, she protected her husband by telling the police she had not seen him. She would be arrested for two days under the Directory, and her allies René Lebois and René Vatar (the latter would die in exile under the Napoleonic regime, if I understand correctly) protested against this.

She managed clandestine communication under the guise of a mother of a family (she took good care of her children). This shows she was a trusted figure within the Babouvist circle, capable of deceiving the police and displaying initiative and intelligence, according to Jean-Marc Schiappa. There seems to have been a brief moment of tension between the Babeufs, according to Advielle, but this letter is neither signed nor dated, and there’s a stern phrase from Gracchus: "We are no longer tender at all," although this seems to be the only tension during their years of revolutionary struggle. She told her husband she would never abandon him. She even tried to help him escape during his last incarceration to prevent his execution, but this failed (she walked miles to support her husband, pregnant and about to give birth, trying to organize his defense with others, alongside Teresa Poggi, Buonarroti's companion).

One aspect that deepens the mystery of Marie-Anne Babeuf is that no physical description of her exists. In fact, physical descriptions of her were made when she was imprisoned at the La Petite-Force prison during Year IV. However, these documents were destroyed because she was never convicted. One can imagine a similar scenario when she was arrested by the Napoleonic police in 1801 and underwent brutal questioning in 1808. What a shame. I would have liked to know, for example, what her relationship with Albertine Marat, Marat's sister, was like, as she had good relations with Gracchus Babeuf. It is certain they met, as Albertine gave Gracchus a letter to publish against Stanislas Fréron, as you can see here https://www.tumblr.com/nesiacha/767708756031176704/i-am-so-exhausted-that-i-only-now-realize-that-i?source=share . At this time, Marie-Anne Babeuf was in Paris, collaborating faithfully with her husband. I would also have liked to know her relationship with the Duplay family. Perhaps some members of the Duplay family never spoke of her to protect her after all the misfortunes she had suffered and the suffering of her surviving son, Émile (I’m thinking specifically of Elisabeth Le Bas, for example). Perhaps they didn’t get along, despite the common cause and Gracchus becoming a fervent admirer of Robespierre again after having violently criticized him, but I don’t know.

Why did Joseph Fouché target the widow Babeuf?

I will now propose a few theories explaining why Joseph Fouché, Minister of Police, targeted the widow Babeuf twice. It is certain that in 1801, he included her name in the list of Jacobins to arrest, and then he authorized an arrest warrant for her son, Émile Babeuf (Émile escaped arrest because he was working abroad). Marie-Anne Babeuf underwent quite a harsh moral interrogation, and her papers were seized, although they were innocent of the Malet conspiracy, I talk about it in a personal and not very important post https://www.tumblr.com/nesiacha/770322937812336640/one-of-the-creepiest-things-among-the-many.

Theory 1: Opportunistically, Fouché wanted to show Bonaparte that he had no mercy for the Jacobins (after all, Fouché was in a delicate position), especially after the attack on Rue Saint-Nicaise, which I briefly discussed here and here. Bonaparte had not forgotten the Babouvistes, so the widow Babeuf was a logical target. But why attack her and her son again in 1808, even though this episode of the Malet conspiracy exposes Fouché’s limits as Minister of Police, according to Jean Tulard? I don’t know. I think after that it's because Emile had contacted Buonarroti so maybe for a verification. Honestly I think the first hypothesis is the most plausible.

Theory 2: Gracchus Babeuf and Fouché worked together at one point (more precisely, Fouché manipulated Gracchus before Gracchus realized his true nature and showed him the door, as you can see here). It is highly probable, if not nearly certain, that Fouché met Gracchus's wife and saw her political talents, activism, her combative nature in the underground, and her ability to evade the police, since she was always by Gracchus’s side. As a close ally to her husband, she had been involved in underground activities, and Fouché may have suspected her of continuing anti-Napoleonic actions. Furthermore, her associations with neo-Jacobins and opponents like René Vatar and Félix Le Peletier might have fueled Fouché’s suspicion. Perhaps these suspicions were justified, given the strong character of the widow Babeuf. In 1808, he may have wanted to verify this. Fouché was just acting as a "good" Minister of Police to fight the Empire’s opponents (even though again, why target her son? Perhaps as a warning or because he was beginning to want to become a revolutionary activist apart).

Theory 3: The third theory is the one I believe the least but after discussion with friends I decided to put it. We know that Fouché liked to keep all documents concerning him at his disposal, including delicate documents about others, and he liked to destroy traces of himself (including information about his own mother, for which there is no trace). In fact, in his last days, he burned papers containing important correspondence, notably with Condorcet, Robespierre, Collot d'Herbois, and others. We know that Gracchus Babeuf had to produce documents about him, especially when Gracchus considered him an ally. It’s possible that Fouché sought to recover these documents, either directly or indirectly. We also know that in Gracchus Babeuf’s final letter before his execution, he left his defense papers with his wife, recommending that they be passed to their friends. Here’s an excerpt from this letter: "Lebois announced that he would print our defenses separately. It is necessary to give my defense as much publicity as possible. I recommend to my wife, my dear friend, not to give to Baudouin, to Lebois, or to others, any copy of my defense, without having another accurate one kept with her, so as to ensure that this defense is never lost" as you can see here https://www.tumblr.com/nesiacha/765954409563897856/last-letter-of-babeuf-before-his-execution?source=share .

What is the connection? Gracchus Babeuf may have entrusted his wife with other important papers, and Joseph Fouché might have wanted to recover them, either indirectly, or he wanted to verify their contents to see if they concerned him directly. So what to do if Marie-Anne Babeuf surely didn’t want anything to do with him anymore? He could commit a burglary ( Fouché clearly demonstrated that he often acted outside the law in ways that are difficult to understand. I am currently examining the Clément de Ris case more closely through the papers of Clément de Ris to see if the hypothesis of historian Alain Decaux aligns with that of Waresquiel, which highlights the extent to which Fouché could be unscrupulous at times as you all know which is an understatement ). However, Marie-Anne Babeuf would have quickly deduced who it was or would have her suspicions. It is important to say that the Babeufs had important links with François Réal , who had an important role in Bonaparte’s government (François Réal, one of the few with Admiral Truguet, openly protested against Bonaparte when Napoleon ordered the repression of the Jacobins in 1801 during a council). So she might have informed Réal, who would tell Bonaparte, which would have been problematic.So burglary is out of the question . On the other hand, when someone is arrested or interrogated, their house can be searched legally. This is partly why he included Marie-Anne Babeuf's name in the list of Jacobins to be arrested in 1801—to thoroughly search her home and the homes of her friends to try to recover her papers. Perhaps Fouché was not satisfied with what he found in 1801 and took the opportunity to try again and search her home in 1808. Proof is that her papers were confiscated, even though they were returned to her two days later. So, Fouché targeted Marie-Anne Babeuf to verify that she didn’t have any compromising documents about him, or to try to get his hands on any papers Gracchus might have left, which could be important for him.

Theory about Marie-Anne Babeuf's Date of Death

Finally, the date of Marie-Anne Babeuf’s death remains a great mystery, but I will propose a hypothesis. In my opinion, she surely died after her friends and comrades, Félix Le Peletier and Philippe Buonarroti. Indeed, Félix Le Peletier was very close to the Babeufs, almost a family member, a mentor, a protector and it seems hard to believe that there would not have been a written account if he had lost one of his closest friends and a companion in struggle. Buonarroti, despite his suspicions about Émile’s Bonapartist leanings, also likely would have mentioned Marie-Anne’s passing, as she had been his ally.

One source says she was alive in 1842, according to Advielle, quoted by Dommanget and Legrand, because she supposedly signed as the widow Babeuf. However, given her spelling issues, it is likely that it was actually Émile Babeuf's wife (Émile passed away in 1842). Personally, I believe Marie-Anne Babeuf died between 1841 and 1842, because otherwise, I think Albertine Marat would have mentioned her death, since Marat's sister died in 1841. I say this because it would have been horrible for her to lose two daughters (one died from a scalding accident, the other from malnutrition under the Directory) and later two sons (Camille in 1814 by suicide at the time of the Allies' entry into Paris—some say from depression, others say from "patriotism", and Caius Babeuf, who died at 17 in the defense of Paris in 1814). It would have been so painful if she had also lost the last son she had left after everything she had suffered.

My theory is that she died between 1841 and 1842.

Émile Babeuf's Lie about His Mother's Origins

Émile Babeuf lied about his mother’s origins, claiming she was not a maid: "It is false that my mother was a maid," and that she was, according to him, "the friend of a noblewoman who had taken her out of the convent." Why did Émile Babeuf lie? To protect his mother from persecution by inventing more important origins to try to deter their enemies from attacking them? Or was it to protect himself, given his activism (he joined Bonaparte’s Hundred Days and was involved in opposition to the Bourbons) and the subsequent persecution he faced under the Restoration? Or did he simply want to glorify his parents?

A Final Word from Jean-Marc Schiappa:

"Like Hecuba, the Queen of Troy, she had the misfortune of seeing almost all of her children (including two young daughters) die. There was a Greek tragedy in her fate. Always poor, always suffering, always unknown, always a victim, but always present, and always faithful... An admirable woman, she deserves much more than these few lines, but history has left us with few elements to better describe her. How can we not regret her?"

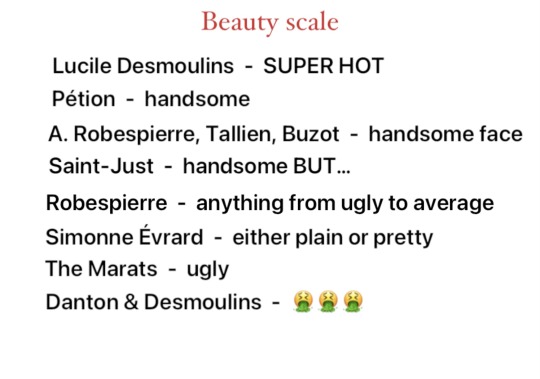

But in my view, she was far more than faithful—she was a fighter, just like her husband. Just as Camille Desmoulins would not have been as effective without Lucile Desmoulins, Antoine-François Momoro without Sophie Momoro, the Marquis de Condorcet without Sophie de Grouchy, Philippe Le Bas without Elisabeth, Jean-Paul Marat without Albertine Marat, his partner Simone Evrard, and her sister Catherine, Gracchus Babeuf would not have made it as far without his faithful political right-hand, Marie-Anne Babeuf, who never ceased to fight, surely even after Gracchus’s death.

#frev#french revolution#napoleonic era#babeuf#marie anne babeuf#joseph fouché#albertine marat#napoleon bonaparte#1800s#history#france#theories#felix lepeletier#buonarroti#women's history#women in revolution

21 notes

·

View notes

Note

10, 13, and 26 for history asks :D

10. Pieces of art ( paintings, sculpures, lithographies, ect.) related to history you like most ( post an image of them)

Self-Portrait of Boilly as a sans-culotte:

13. Something random about some random historical person in a random era.

This will be more about the present but hear me out. Nikola Tesla was cremated and his ashes rest in a spherical urn in the Nikola Tesla museum, Belgrade (Serbia). There is a HUGE controversy in Serbia over this, because it's seen as an inappropriate burial for such a huge figure of national pride. But the museum doesn't want to give the urn to the church, so there are periodical protests/fights/controversies over it, particularly near the elections, when there is a need to score political points over Tesla's remains. 26. Forgotten hero we should know about and admire?

Already answered with Michel Lepeletier, so now maybe Félix Lepeletier. Not as heroic, but I love a reformed himbo.

18 notes

·

View notes

Note

Thank you for collecting these! I think Michel is a super interesting figure and I wonder why he is forgotten when he was hailed "the first martyr" and so often depicted together with Marat.

I will try to find more about his friendship with Hérault. They were about the same age, too, although Lepeletier sounds more mature and well-adjusted.

Félix, as I understand, was a hopeless womanizer and carefree until the death of his brother. Michel's assassination changed him and he became a dedicated Jacobin for the rest of his life. He helped Babeuf and the Conspirscy of the Equals crowd (he cared for Babeuf's son after B's death), and was an "old man yelling at the cloud" during the subsequent regimes, never abandoning his beliefs. (As far as I can tell). Truly a reformed hoe! (Though I don't think Jacobinism cured him of womanizing).

I understand the story of marat and his assassination event

But who is lepeletier?

Because I saw a drawing for him by louis David and I learned about his death which happen to be the same as Marat so yeah .. I wanna know about him.

According to the biography Michel Lepeletier de Saint-Fargeau, 1760-1793 (1913), its subject of study was born on 29 May 1760, in his family home on rue Culture-Sainte-Catherine, a building which today is the Bibliothèque Historique de la Ville de Paris. His family belonged to the distinguished part of the robe nobility. At the death of his father in 1769, Lepeletier was both Count of Saint-Fargeau, Marquis of Montjeu, Baron of Peneuze, Grand Bailiff of Gien as well as the owner of 400,000 livres de rente. For five years he worked as avocat du roi at Châtelet, before becoming councilor in Parliament in 1783, general counsel in 1784 and finally taking over the prestigious position of président à mortier at the Parlement of Paris from his father in 1785. On May 16 1789, Lepeletier was elected to represent the nobility at the Estates General. On June 25 the same year he was one of the 47 nobles to join the newly declared National Assembly, two days before the king called on the rest of the first two estates to do so as well. A month later, during the night of August 4 1789, he was in the forefront of those who proposed the suppression of feudalism, even if, for his part, this meant losing 80 000 livres de rente. Four days later he wrote a letter to the priest of Saint-Fargeau, renouncing his rights to both mills, furnaces, dovecote, exclusive hunting and fishing, insence and holy water, butchery and haulage (the last four things the Assembly hadn’t ruled on yet). When the Assembly on June 19 1790 abolished titles, orders, and other privileges of the hereditary nobility, Lepeletier made the motion that all citizens could only bear their real family name — ”The tree of aristocracy still has a branch that you forgot to cut..., I want to talk about these usurper names, this right that the nobles have arrogated to themselves exclusively to call themselves by the name of the place where they were lords. I propose that every individual must bear his last name and consequently I sign my motion: Michel Lepeletier” — and the same year he also, in the name of the Criminal Jurisprudence Committee, presented a report on the supression of the penal code and argued for the abolition of the death penalty. After the closing of the National Assembly in 1791, Lepeletier settled in Auxerre to take on the functions of president of the directory of Yonne, a position to which he had been nominated the previous year. He did however soon thereafter return to Paris, as he, following the overthrow of the monarchy, was one of few former nobles elected to the National Convention, where he was also one of even fewer former nobles to sit together with the Mountain. In December 1792 he started working on a public education plan. On January 20 1793, he voted for death without a reprieve and against an appeal to the people during the trial of Louis XVI (Opinion de L.M. Lepeletier, sur le jugement de Louis XVI, ci-devant roi des François: imprimée par ordre de la Convention nationale). After the session was over, Lepeletier went over to Palais-Égalité (former Palais-Royal) where he dined everyday. The next day, his friend and fellow deputy Nicolas Maure could report the following to the Convention:

Citizens, it is with the deepest affection and resentment of my heart that I announce to you the assassination of a representative of the people, of my dear colleague and friend Lepelletier, deputy of Yonne; committed by an infamous royalist, yesterday, at five o'clock, at the restaurateur Fevrier, in the Jardin de l'Égalité. This good citizen was accustomed to dining there (and often, after our work, we enjoyed a gentle and friendly conversation there) by a very unfortunate fate, I did not find myself there; for perhaps I could have saved his life, or shared his fate. Barely had he started his dinner when six individuals, coming out of a neighboring room, presented themselves to him. One of them, said to be Pâris, a former bodyguard, said to the others: There's that rascal Lepeletier. He answered him, with his usual gentleness: I am Lepeletier, but I am not a rascal. Paris replied: Scoundrel, did you not vote for the death of the king? Lepelletier replied: That is true, because my confidence commanded me to do so.Instantly, the assassin pulled a saber, called a lighter, from under his coat and plunged it furiously into his left side, his lower abdomen; it created a wound four inches deep and four fingers wide. The assassin escaped with the help of his accomplices. Lepeletier still had the gentleness to forgive him, to pray that no further action would be taken; his strength allowed him to make his declaration to the public officer, and to sign it. He was placed in the hands of the surgeons who took him to his brother, at Place Vendôme. I went there immediately, led by my tender friendship, and my reverence for the virtues which he practiced without ostentation: I found him on his death bed, unconscious. When he showed me his wound, he uttered only these two words: I'm cold. He died this morning, at half past one, saying that he was happy to shed his blood for the homeland; that he hoped that the sacrifice of his life would consolidate Liberty; that he died satisfied with having fulfilled his oaths.

This was the first time a Convention deputy had gotten murdered, and it naturally caused strong reactions. Already the same session when Maure had announced Lepeletier’s death, the Convention ordered the following:

There are grounds for indictment against Pâris, former king's guard, accused of the assassination of the person of Michel Lepelletier, one of the representatives of the French people, committed yesterday.

[The Convention] instructs the Provisional Executive Council to prosecute and punish the culprit and his accomplices by the most prompt measures, and to without delay hand over to its committee of decrees the copies of the minutes from the justice of the peace and the other acts containing information relating to this attack.

The Decrees and Legislation Committees will present, in tomorrow's session, the drafting of the indictment.

An address will be written to the French people, which will be sent to the 84 departments and the armies, by extraordinary couriers, to inform them of the crime against the Nation which has just been committed against the person of Michel Lepelletier, of the measures that the National Convention has taken for the punishment for this attack, to invite the citizens to peace and tranquility, and the constituted authorities to the most exact surveillance.

The entire National Convention will attend the funeral of Michel Lepelletier, assassinated for having voted for the death of the tyrant.

The honors of the French Pantheon are awarded to Michel Lepelletier, and his body will be placed there.

The president is responsible for writing, on behalf of the National Convention, to the department of Yonne, and to the family of Lepelletier.

The next day, January 22, further instructions were given regarding Lepeletier’s funeral:

On Thursday January 24, Year 2 of the Republic, at eight o'clock in the morning, will be celebrated, at the expense of the Nation, the funeral of Michel Lepeletier, deputy of the department of Yonne to the National Convention.

The National Convention will attend the funeral of Michel Lepeletier in its entirety. The executive council, the administrative and judicial bodies will attend it as well.

The executive council and the department of Paris will consult with the Committee of Public Instruction regarding the details of the funeral ceremony.

The last words spoken by Michel Lepeletier will be engraved on his tomb, they are as follows: “I am happy to shed my blood for the homeland; I hope that it will serve to consolidate Liberty and Equality; and to make their enemies recognized.”

In number 27 (January 27 1793) of Gazette Nationale ou Le Moniteur Universel, the following long description was given over Lepeletier’s funeral, held three days earlier:

The funeral of Lepeletier Saint-Fargeau was celebrated on Thursday 24 with all the splendor that the severity of the weather and the season allowed, but with such a crowd that it could have been the most beautiful day of the year. At ten o'clock in the morning his deathbed was placed on the pedestal where the equestrian statue of Louis XVI previously stood, on Place Vendôme, today Place des Piques. One went up to the pedestal by two staircases, on the banisters of which were antique candelabras. The body was lying on the bed with the bloody sheets and the sword with which he had been struck. He was naked to the waist, and his large and deep wound could be seen exposed. These were the mournful and most endearing part of this great spectacle. All that was missing was the author of the crime, chained, and beginning his torture by witnessing the sight of the triumph of Saint-Fargeau. As soon as the National Convention and all the bodies that were to form courage were assembled in the square, mournful music was played. It was, like almost all those which has embellished our revolutionary festivals, the composition of citizen Gossec. The Convention was ranged around the pedestal. The citizen in charge of the ceremonies presented the President of the Convention with a wreath of oak and flowers; then the president, preceded by the ushers of the Convention and the national music, went around the monument, and went up to the pedestal to place the civic crown on Lepeletier's head: during this time, a federate gave a speech; the president dismounted, the procession set out in the following order: A detachment of cavalry preceded by trumpets with fourdincs. Sappers. Cannoneers without cannons. Detachment of veiled drummers. Declaration of the rights of man carried by citizens. Volunteers of the six legions, and 24 flags. Drum detachment. A banner on which was written the decree of the Convention which ordered the transport of Lepeletier's body to the Pantheon. Students of the homeland. Police commissioners. The conciliation office. Justices of the peace. Section presidents and commissioners. The commercial court. The provisional criminal court. The department’s fix courts. The electorate. The provisional criminal court. The department's criminal courts fix. The municipality of Paris. The districts of Saint-Denis and the village of L’Égalité. The Department. Drum detachment. The seal of the 84, worn by Federates. The provisional executive council. National Convention Guard Detachment. The court of cassation. Figure of Liberty carried by citizens. The bloody clothes worn at the end of a national pike, deputies marching in two columns. In the middle of the deputies was a banner where Lepeletier's last words were written: "I am happy to shed my blood for my homeland, I hope that it will serve to consolidate Liberty and Equality, and to make their enemies known.”

The body carried by citizens, as it was exhibited on the Place des Piques. Around the body, gunners, sabers in hand, accompanied by an equal number of Veterans. Music from the National Guard, who performed funeral tunes during the march. Family of the dead. Group of mothers with children. Detachment of the Convention Guard. Veiled drums. Volunteers of the six legions and 24 flags. Veiled drums. Volunteers of the six legions and 24 flags. Veiled drums. Volunteers of the six legions and 24 flags. Veiled drums. Armed federations. Popular societies. Cavalry and trumpets with fourdines. On each side, citizens, armed with pikes, formed a barrier and supported the columns. These citizens held their pikes horizontally, at hip height, from hand to hand. The procession left in this order from the Place des Piques, and passed through the streets St-Honoré, du Roule, the Pont-Neuf, the streets Thionville (former Dauphine), Fossés Saint-Germain, Liberté (former Fossés M. le Prince), Place Saint-Michel and Rue d'Enfer, Saint-Thomas, Saint-Jacques and Place du Panthéon. It stopped front of the meeting room of the Friends of Liberty and Equality; opposite the Oratory, on the Pont-Neuf, opposite the Samaritaine; in front of the meeting room of the Friends of the Rights of Man; at the intersection of Rue de la Liberté; Place Saint-Michel and the Pantheon. Arriving at the Pantheon, the body was placed on the platform prepared for it. The National Convention lined up around it; the band, placed in the rostrum, performed a superb religious choir; Lepeletier's brother then gave a speech, in which he announced that his brother had left a work, almost completed, on national education, which will soon be made public; he ended with these words: I vote, like my brother, for the death of tyrants. The representatives of the people, brought closer to the body, promised each other union, and swore on the salvation of the homeland. A big chorus to Liberty ended the ceremony.

According to Michel Lepeletier de Saint-Fargeau, 1760-1793 (1913), civic festivals in honor of Lepeletier were celebrated in all sections of Paris, as well as the towns of Arras, Toulouse, Chaumont, Valenciennes, Dijon, Abbeville and Huningue. Lepeletier’s body did however only get to rest in the Panthéon for a little more than a year, as on February 15 1795, the Convention ordered it exhumed, at the same time as that of Marat. It was instead buried in the park surrounding Château de Ménilmontant, the properly of which the ancestor Lepeletier de Souzy had purchased in the 17th century and that still remained in the family.

One day after the funeral, January 25, Lepeletier’s only child, the ten and a half year old Susanne, who had already lost her mother ten years before the murder of her father, was brought before the Convention by her step-mother and two paternal uncles Amédée and Félix. It was Félix who had held a speech during the funeral and he would continue to work for his seven years older brother’s memory afterwards too, offering a bust of him to the Convention on February 21 1793, (on the proposal of David, it was placed next to the one of Brutus), reading his posthumous work on public education to the Jacobins on July 19 1793, and even writing a whole biography over his life in 1794 (Vie de Michel Lepeletier, représentant du peuple français, assassiné à Paris le 20 janvier 1793 : faite et présentée a la Société des Jacobins).

The president announces that the widow of Michel Lepelletier, his two brothers and his daughter, request to be admitted to the bar, to testify to the Convention their recognition of the honors that they have decreed in memory of their relative. It is decreed that they will be admitted immediately.

One of Michel Lepeletier’s brothers: Citizens, allow me to introduce my niece, the daughter of Michel Lepelletier; she comes to offer you and the French people her recognition of the eternity of glory to which you have dedicated her father... He takes the young citoyenne Lepelletier in his arms, and makes her look at the president of the Convention... My niece, this is now your father... Then, addressing the members of the Convention, and the citizens present at the session: People, here is your child... Lepelletier pronounces these last words in an altered voice: silence reigns throughout the room, with exception for a couple of sobs.

The President: Citizens, the martyr of Liberty has received the just tribute of tears owed to him by the National Convention, and the just honor that his cold skin has received invites us to imitate his example and to avenge his death. But the name of Lepelletier, immortal from now on, will be dear to the French Nation. The National Convention, which needs to be consoled, finds relief to its pain in expressing to his family the just regrets of its members and the recognition of the great Nation of which it is the organ. The Nation will undoubtedly ratify the adoption of Michel Lepelletier's daughter that is currently being carried out by the National Convention.

Barère: The emotion that the sight of Michel Lepeletier's only daughter has just communicated to your souls must not be infertile for the homeland. Susanne Lepelletier lost her father; she must find now find one in the French people. Its representatives must consecrate this moment of all-too-just felicity to a law that can bring happiness to several citizens and hope to several families. The errors of nature, the illusions of paternity, the stability of morals, have long demanded this beautiful institution of the Romans. What more touching time could present itself at the National Convention to pass into French legislation the principle of adoption, than that when the last crimes of expiring tyranny deprived the homeland of one of its ardent defenders and Susanne Lepelletier of a dear father! Let the National Convention therefore give today the first example of adoption by decreeing it for the only offspring of Lepelletier; let it instruct the Legislation Committee to immediately present the bill on this interesting subject. I ask that the homeland adopt through your organ Susanne Lepelletier, daughter of Michel Lepelletier, who died for his country; that it decrees that adoption will be part of French legislation, and instructs its Legislation Committee to immediately present the draft decree on adoption.

This proposal is unanimously approved.

Susanne being adopted by the state would however lead to a fierce debate when, in 1797, this ”daughter of the nation” wished to marry a foreigner. For this affair, see the article Adopted Daughter of the French People: Suzanne Lepeletier and Her Father, the National Assembly (1999)

Right after Barère’s intervention, David took to the rostrum:

David: Still filled with the pain that we felt, while attending the funeral procession with which we honored the inanimate remains of our colleagues, I ask that a marble monument be made, which transmits to posterity the figure of Lepelletier , as you clearly saw, when it was brought to the Pantheon. I ask that this work be put into competition.

Saint-André: I ask that this figure be placed on the pedestal which is in the middle of Place Vendôme... (A few murmurs arise)

Jullien: I ask that the Convention adopt in advance, in the name of the homeland, the children of the defenders of Liberty, who, for similar reasons, could be immolated in the vengeance of the royalists.

All these proposals are referred to the Legislation and Public Instruction Committees.

On Maure's proposal, the Assembly orders the printing of the speeches delivered yesterday at the Panthéon, by one of Michel Lepelletier's brothers, Barère and Vergniaux.

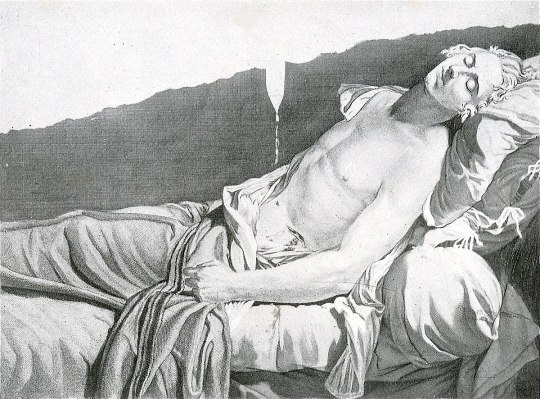

If it would appear David never got to make a marble monument of Lepeletier, on March 28 1793, he could nevertheless present the following painting of his to the Convention, which isn’t just a little similar to his La Mort de Marat.

(This image is an engraving of the actual painting, which has gone missing)

After Marat on July 13 1793 (on the very same day the plan for public education Lepeletier had been working on was read to the Convention by Robespierre) became the second assassinated Convention deputy, we find several engravings etc, depicting the two ”martyrs of liberty” side by side.

In the following months, even more people would be join the two, such as Joseph Chalier, a lyonnais politician executed on July 17 1794 and Joseph Bara, a fourteen year old republican drummer boy killed in the Vendée by the pro-Monarchist forces.

Lepeletier’s murderer, 27 year old Philippe Nicolas Marie de Pâris, a man who the minister of justice described as "former king's guard, height five pieds, five pouces, barbe bleue, and black hair; swarthy complexion, fine teeth, dressed in a gray cloak, green lapels and a round hat” on January 21, went into hiding right after his deed. In spite of his description being published in the papers and a considerable sum of money being promised to whoever caught him, Pâris managed to flee Paris and settled for a country house of an acquaintance near Bourget. He there ran into a cousin of one of the owners. When Pâris asked for food and a bed, he was refused and instead disappeared into the night again. In the evening of January 28 he arrived in Forges-les-Eaux and stopped at an inn, where he came under suspicion once he started cutting his bread with a dagger after which he locked himself into his room. The following morning he woke up with a start as five municipal gendarmes came bursting into his room and told him to come with them. Pâris responded that he would, but in the next second he had picked up his hidden pistol, placed it into his mouth, and pulled the trigger. Searching the dead body, the gendarmes found Pâris’ baptism record (dated November 12 1765) and dismissal from the king's guard (dated June 1 1792), on the latter of which had been written the following:

My certificate of honor. Do not trouble anyone. No one was my accomplice in the fortunate death of the scoundrel de Saint-Fargeau. Had I not run into him, I would have carried out a more beautiful action: I would have purged France of the patricide, regicide and parricide d’Orléans. The French are cowards to whom I say: Peuple dont les forfaits jettent partout l'effroi, Avec calme et plaisir j'abandonne la vie. Ce n'est que par la mort qu'on peut fuir l'infamie Qu'imprime sur nos fronts le sang de notre roi. Signed by Paris the older, guard of the king, assassinated by the French.

Learning about what had happened, the Convention tasked Tallien and Legrand with going to Forges-les-Eaux and making sure the dead man really was Pânis. Having come to the conclusion that this was indeed the case, the deputies briefly discussed whether the body ought to be brought back to Paris, but it was decided it would be better if it was just buried "with ignominy.” It was therefore instead taken into the nearby forest in a wheelbarrow and thrown into a six feet deep hole.

Finally, here are some other revolutionaries simping for honoring Lepeletier’s memory just because I can:

…a tragic event took place the day before the execution [of the king]. Pelletier, one of the most patriotic deputies, and who had voted for death, was assassinated. A king's guard made a wound three fingers wide with a saber: he died this morning. You must judge the effect that such a crime has had on the friends of liberty. Pelletier had an income of six hundred thousand livres; he had been président à mortier in the Parliament of Paris; he was barely thirty years old; to many talents, he added the most estimable of virtues. He died happy, he took to his grave the idea, consoling for a patriot, that his death would serve the public good. Here then is one of these beings whom the infamous cabal who, in the Convention, wanted to save Louis and bring back slavery, designated to the departments as a Maratist, a factious, a disorganizer... But the reign of these political rascals is finished. You will see the measures that the Assembly took both to avenge the national majesty and to pay homage to a generous martyr of liberty. Philippe Lebas in a letter to his father, January 21 1793

Ah! if it is true that man does not die entirely and that the noblest part of himself survives beyond the grave and is still interested in the things of life, come then, dear and sacred shadow, sometimes to hover above the Senate of the nation that you adorned with your virtues; come and contemplate your work, come and see your united brothers contributing to the happiness of the homeland, to the happiness of humanity. Marat in number 105 (January 23 1793) of Journal de la République Française

O Lepeletier! Your death will serve the Republic: I envy your death. You ask for the honors of the Pantheon for him, but he has already collected the prize of martyrdom of Liberty. The way to honor his memory is to swear that we will not leave each other without having given a constitution to the Republic. Danton at the Convention, January 21 1793

O Le Peletier, tu étais digne de mourir pour la patrie sous les coups de ses assassins ! Ombre chère et sacrée, reçois nos vœux et nos serments ! Généreux citoyen, incorruptible ami de la vérité, nous jurons par tes vertus, nous jurons par ton trépas funeste et glorieux de défendre contre toi la sainte cause dont tu fus l'apôtre; nous jurons une guerre éternelle au crime dont tu fus l'éternel ennemi, à la tyrannie et à la trahison, dont tu fut la victime. Nous envions ta mort et nous saurons imiter ta vie. Elles resteront à jamais gravées dans nos cœurs, ces dernières paroles où lu nous montrais ton âme tout entière; ”Que ma mort, disais tu, sera utile à la patrie, qu'elle serve à faire connaître les vrais et les faux amis de la liberté, et je meurs content. Robespierre at the Jacobins, January 23

Wednesday 23 [sic] — We went to Madame Boyer’s to see the procession. I saw the poor Saint-Fargeau. We all burst into tears when the body passed by, we threw a wreath on it. After the ceremony, we returned to my house. Ricord and Forestier had arrived. I was unable to stop my tears for some time. F(réron), La P(oype), Po, R(obert) and others came to dinner. The dinner was quite fun and cheerful. Afterwards they went to the Jacobins, Maman and I stayed by the fire and, our imaginations struck by what we had seen, we talked about it for a while. She wanted to leave, I felt that I could not be alone and bear the horrible thoughts that were going to besiege me. I ran to D(anton’s). He was moved to see me still pale and defeated. We drank tea, I supped there. Lucile Desmoulins in her diary, January 24 1793

…Pelletier's funeral took place this Thursday as I informed you in my last letter (this letter has gone missing). The procession was immense; it seemed that the population of Paris had doubled, to honor the memory of this virtuous citizen. The mourning of the soul was painted on all the faces: it was especially noticed that the people were extremely affected, which proves that they keenly felt the price of the friend they had lost. Arriving at the Pantheon, Lepelletier's body was placed on the platform prepared for it; his brother delivered a speech which was applauded with tears; Barère succeeded him. Then the members of the Convention, crowding around the body of their colleague, promised union among themselves, and took an oath to save the country. God grant that we have not sworn in vain, that we finally know the full extent of our duties, and that we only occupy ourselves with fulfilling them! In yesterday's session, Pelletier's daughter, aged eight [sic], was presented to the National Convention, which immediately adopted her as a child of the homeland. Georges Couthon in a letter written January 26 1793

How could I be so base as to abandon myself to criminal connections, I who, in the world, have never had more than one close friend since the age of six? (he gestures towards David's painting). Here he is! Michel Lepeletier, oh you from whom I have never parted, you whose virtue was my model, you who like me was the target of parliamentary hatred, happy martyr! I envy your glory. I, like you, will rush for my country in the face of liberticidal daggers; but did I have to be assassinated by the dagger of a republican! Hérault de Sechelles at the Convention, December 29 1793

For a collection of Lepeletier’s works, see Oeuvres de Michel Lepeletier Saint-Fargeau, député aux assemblées constituante et conventionnelle, assassiné le 20 janvier 1793, par Paris, garde du roi (1826)

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Ambiguous Political Relationship Between Lazare Carnot and Félix Le Peletier

On the surface, and even at a deeper ideological level, a lot divides these two men. Félix Le Peletier became one of the most well-known republican opponents of the Directoire period (among the famous opponents of this period are Bernard Metge, Xavier Audouin, Antonelle, Jean-Baptiste Drouet, Gracchus Babeuf, Victor Bach, although some of them were not aligned on the same ideals—for example, Metge was a liberal follower of the Constitution of Year III and anti-Babouvist), whereas Lazare Carnot was one of the most important members of the Directoire. Carnot was much more conservative on many points compared to Félix Le Peletier. However, their relationship is far more complex than simply being sworn enemies.

Here is an excerpt from their complex relationship: "In early November 1795, upon Carnot's recommendation, Félix Le Peletier was offered a position as a commissioner of the Directoire in the department of Seine-et-Oise. He rejected it with surprising virulence, informing Carnot that he regarded him as a tyrant and would continue to work to overthrow him. Carnot-Feulins, in his Histoire du Directoire, asserts, however, that Félix Le Peletier and his brother had close relations and frequently conversed. In 1796, when the Conjuration des Égaux was suppressed, Carnot led the operation. Yet, Félix Le Peletier escaped the police. Was this with Carnot's complicity? It seems hard to believe, especially since an archival document suggests that he narrowly escaped a police dragnet because he was detained in a café on Rue des Deux-Écus with a soldier. However, when in May 1796, he dared to publish his Second Reflections on the Present Moment, a strong indictment in favor of equality and common happiness, it is certain that he benefited from effective protection. At the same time, an arrest warrant signed by Carnot was issued for Félix Le Peletier, 'accused of conspiracy against the internal and external security of the Republic.' Despite this, Félix Le Peletier acted quite freely in Paris and Versailles. Was Carnot playing a double game? One might assume so. There is testimony to support this. A passage from the Mémoires sur Carnot by his son claims that during the Grenelle uprising, Carnot warned Félix Le Peletier the very morning that the police were about to intervene. Félix Le Peletier supposedly shared this warning with several others. Finally, the close ties between Carnot and Félix Le Peletier are evident during the Hundred Days. Carnot was appointed Minister of the Interior. On his recommendation, Félix Le Peletier was appointed commissioner of the Empire in the department of Seine-Inférieure, where he lived. Elected to the Chamber of Representatives after the May 1815 legislative elections, he went to Paris and was offered the Legion of Honor by Carnot, which he refused."

What is strange is that Félix Le Peletier never forgot that Carnot was responsible for the death of his friend Gracchus Babeuf (whom he was very close to). I believe that while Félix Le Peletier was a staunch activist, he did not believe in the death of a republican martyr and was prepared to continue living and fighting without abandoning his friends. After all, Félix Le Peletier accepted help from his childhood friend Saint-Jean d’Angely when he was persecuted by Bonaparte and nearly deported. So, he might have accepted help from Carnot as well, even though his friend Gracchus Babeuf had been condemned to death, for in any case, Félix could have done nothing.

What I personally find intriguing is Carnot's attitude. I mean, he clearly saw that Félix was not a real threat and decided to protect him. That is to his credit. Yet, he led a repression against the Babouvists, including Félix Le Peletier's friends. I get the impression that Carnot overestimated the "danger" posed by Gracchus and his Babouvist associates compared to other elements under the Directoire regime, and that’s why Carnot acted this way.

Perhaps this is one of the reasons why Gracchus (and Buonarotti) spared Carnot from most of the criticism, while he was virulent against Cochon, the Minister of Police, and Grisel, despite the terrible ordeals Gracchus endured, such as being transported in a metal cage from Paris to Vendôme. The reason may be that Carnot at least protected some of his friends, in addition to other reasons I’ve mentioned here. Indeed, in the last letter Gracchus sent to his friend Félix, he told him that he knew Félix would be spared, even though Gracchus was to be executed, as you can see here.

But the fact that Carnot wanted to recruit Félix Le Peletier offers a plausible explanation for why Émile Babeuf might have worked for Carnot, specifically on a mission during the Hundred Days, as shown here. Indeed, Émile Babeuf, like Félix Le Peletier, aligned with Bonaparte during the Hundred Days. Now, we know that Félix Le Peletier was a protector of the Babeuf family and very close to them (he considered them as a family, and vice versa, not to mention their shared political views on several points). So it’s likely that if Carnot wanted Félix Le Peletier to work for him, Félix could have served as an intermediary for Émile Babeuf to send a letter to Lazare Carnot. This now makes more sense to me, considering what happened between Carnot and Gracchus Babeuf.

Sources (about the excerpt) :

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Michel and Félix Le Peletier

I need to read more about them. If anyone has book recommendations, please let me know!

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

A request for information about a letter from Felix Le Peletier (or a search for his humor)

I was reading a short biography of Felix Le Peletier, and I burst out laughing at his "trickster" side. I mean, nothing compares to the audacity (in a good sense) of an anecdote recounted by Lacour (I believe) about Delgrès, who, surrounded by Richepance's troops trying to restore slavery, played the violin to mock them from the ramparts.

But Felix Le Peletier can give him a run for his money if the anecdote in the document I’m going to share is true. Following his deportation under Bonaparte, he temporarily stayed on the Île de Ré while awaiting another transfer. Just before his imminent departure, he was allowed a visit from a relative, and he seized the opportunity to escape. At the same time, he took it upon himself to inform the Minister of Justice about his escape in a letter, which left the authorities in a bind apparently he informed them before the authorities became aware of his invasion. The Parisian authorities were informed earlier by Felix's letter than by the prefect.

The author speculates, based on plausible hypotheses and evidence, whether he had secured his safety and enjoyed protection, as he managed to travel back and forth to Paris without a hitch. Indeed, his childhood friend had become a councilor of state, so having connections helps.

In any case, whether it’s true or not, I want to see that letter. Don’t you?

Here are the sources of the information I already know

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

The "good deeds" of the "rotten" revolutionaries:

Fouché: he gave a pension to the widow of Collot d'Herbois, apparently also one for Charlotte Robespierre Tallien: he participated in the day of August 10, 1792. In the end he was let go for the wrong reasons because even if he rallied to the right, he tried to make a turnaround to the left to try to prevent the royalists from returning which shows that ultimately he sought to preserve the revolution. Carrier Jean Baptiste: In Nantes he succeeded in repelling the English attempts to establish themselves in this port (which would have been a catastrophe for France if the English had succeeded) Fréron: Stayed in contact with Annette Duplessis, helped her financially after the execution of Camille and Lucile Desmoulins and helped to ensure the education of Horace Turreau: Would have adopted Camille Babeuf after the death of his father (even if it was Felix Lepeletier who was the real protector of this family until to his deportation) P.S: Off topic but I didn't expect it seems that Camille Babeuf sent in 1813 a letter to Pierre-François Réal for a request for financial aid as he is in difficult I'll send you the link if you can connect and access it I can't it seems we must have an account for see the letter https://www.proquest.com/docview/1294139227?sourcetype=Scholarly%20Journals Sources: Antoine Resche Jean Marc Schiappa For Fréron, don't hesitate to see the excellent post by @anotherhumaninthisworld here https://www.tumblr.com/anotherhumaninthisworld/757673440640647168/how-close-desmoulins-and-fr%C3%A9ron-were- and-what-did?source=share

#frev#french revolution#joseph fouché#freron#carrier jean baptiste#Turreau#my mental health took a hit#by dint of looking for their good deeds

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

The political career of the revolutionary Antonelle Pierre-Antoine, close to Felix Lepeletier

Presumed portrait of Pierre Antoine Antonelle

This revolutionary was born in Arles in 1747. As a marquis, he published between 1788 and 1789 "le Catéchisme du Tiers État, à l’usage de toutes les provinces de France, et spécialement de la Provence ." He did not succeed as an officer, due to a lack of both will and ability. Instead, he preferred reading philosophy and mathematics treatises, according to Pierre Serna. He managed to become the first mayor of Arles in 1790.

Antonelle founded a Jacobin society, affiliated with Paris, and opposed Monseigneur de Lau (who was killed during the September massacres). Antonelle supported the common people, while Monseigneur de Lau, despite being attracted to Enlightenment ideas, opposed the Civil Constitution of the Clergy. Antonelle was elected to the Legislative Assembly in 1791 and became a legislative commissioner for the Army of the Center in 1792.

In the autumn of 1792, he gained further importance by being elected as a juror at the Revolutionary Tribunal. He was apparently an alternate who did not participate in Marie Antoinette's trial. Contrary to what Wikipedia claims, he was harsh with Marie Antoinette, although he did not believe the infamous rumors about her son. According to Pierre Serna, Antonelle acted this way because, in his view, one could not build a new world on the revolution without destroying the old roots of the Ancien Régime. However, he declared himself insufficiently informed during the trial of the Girondins. He was imprisoned in May 1794 but was released immediately after the 9th Thermidor.

The Directory was a great disappointment for Antonelle. While Robespierre was nicknamed "the Incorruptible," Antonelle was called "the Invariable," according to Pierre Serna. He maintained a lifelong friendship with Felix Lepeletier, despite a later divergence between them. Involved in the Conspiracy of Equals, he was tried during the Babouvist trial. Apparently, one of the reasons many were spared (except Darthé and Babeuf) was due to Antonelle's strategy. Here is an excerpt from Pierre Serna: "He participated in the Vendôme trial against Babeuf’s accomplices and played a key role in saving almost all of the defendants." According to Serna, for Antonelle, there should be no more martyrs, or at least no more forced uprisings of this kind. He believed in fighting the Directory from within, through elections.

He helped the majority of the Directory's directors on the eve of the coup d'état of 18 Fructidor, Year V, by publishing the newspaper Le Démocrate Constitutionnel to call on the suburbs to fight against the royalists. His election to the Council of Five Hundred in 1799 was annulled due to irregularities, namely his affiliation with the Jacobins.

He quickly sensed the danger of Bonaparte, as it matched the fears of a general too ambitious, who would definitively end the Revolution. The consequences of the Saint-Nicaise Street attack and the terrible repression of the Jacobins led to his expulsion from France. Later, when he returned to France, he was placed under surveillance, although he fared better than his friend Felix Lepeletier, who was temporarily deported. Other Jacobins were executed in what was, in Antonelle’s view, an even worse parody of justice than under the First Republic (particularly because of the use of torture). Many other Jacobins were deported, and half of them died in exile.

He lived in retirement in Arles, continuing his philanthropic activities, becoming beloved by the local population for his generous donations. Despite his reputation as a "priest-eater," he gave large sums of money to nuns in the Church so they could care for the poor. This reputation later saved his life. Antonelle had a political divergence with his friend Lepeletier. In fact, he rallied to the Restoration in 1814 in opposition to Bonaparte and published Le dernier rêve d’un vieillard . He accepted the restoration of Louis XVIII under one condition: that he respects civil equality, equal access to jobs for all, and civil liberties. This was criticized, but honestly, he had to choose between two monarchs (as the return of the monarchy was sealed the day Bonaparte crowned himself, let's not delude ourselves), one of whom had betrayed his entire political circle, executed many, caused a large number of deaths, and rolled back many achievements shortly after his coup d'état while proclaiming himself the savior of the Revolution. In comparison, one could criticize Louis XVIII, but he seemed more reasonable (we cannot say the same of Charles X, who had as much honor as he had intelligence, meaning none at all). I don't blame those who chose Bonaparte either, as they were desperate not to return under the Bourbons' yoke (it must have been a terrible dilemma for all honest republicans to choose between Bonaparte and Louis XVIII).

During the Second Restoration, he was hunted by royalists in Arles. However, being highly esteemed by the local population, especially the farmers , they hid him out of gratitude for his generosity toward them (according to Pierre Serna, the farmers owed a large debt to Antonelle, which he forget the debt after they saved his life).

Having inherited a significant fortune, he gave generously to the people of Arles, who only loved him more for it. When he died in 1817, a massive crowd reportedly attended his funeral. Here is another excerpt from Serna: "His burial led to a popular riot when the clergy refused to give him the last rites, provoking the anger of the common people of Arles. Even in death, Antonelle remained controversial."

In Arles, at 30 Rue de la Roquette, there is a hotel bearing his name, with a plaque in his honor.

Sources: Pierre Serna Jean Dautry

#frev#french revolution#napoleon#napoleonic era#the directory#noble revolutionaries#babeuf#babouvism

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why was Carnot so vehement in repressing the Babouvists while protecting or even wanting to collaborate with some (theories)?

We have seen here that Carnot was one of the main figures behind the repression of the Babouvists, as seen here: https://www.tumblr.com/nesiacha/767944757763883008/babeuf-et-la-r%C3%A9publique-pers%C3%A9e?source=share, wanting to expand arrests to the maximum while protecting some of the Babouvists like Felix Le Peletier (a very close friend of Gracchus Babeuf and protector of Babeuf's family after his death), who had an ambiguous political relationship with Carnot to the point where Carnot protected him and sometimes wanted them to work together https://www.tumblr.com/nesiacha/770487228804759553/f%C3%A9lix-lepeletier-de-saint-fargeau-un-personnage?source=share. If you want to know more about Gracchus Babeuf, including some of my theories, please consult here https://www.tumblr.com/nesiacha/768437156389715968/in-honor-of-gracchus-babeufs-recent-anniversary?source=share, and feel free to correct me, I’m not infallible.

First theory.

At first glance, this seems implausible. And it is indeed a mystery. However, I believe there are some theories that might explain why Carnot was truly after Gracchus Babeuf. Babeuf was one of those who wanted a certain redistribution of property, especially in the agrarian sense (though this is still unclear, and we can’t really talk about communism because Babeuf seemed unaware of the rise of capitalist societies). However, he is one of the rare revolutionaries who began to advocate for the redistribution of property rights.

One of the major revolutionaries who also started theorizing the right to redistribute property was Momoro. Momoro, along with Ronsin, was one of the leaders of the Hébertists. In fact, Momoro had issues with this in Normandy. Here is an excerpt: “On August 30, the Directory of the Department of Paris sent him, accompanied by a certain Jean-Michel Dufour, representing the Commune, to supervise mass levies in Normandy. They arrived in Bernay on September 7, where Momoro immediately made a vehement speech to the assembly of the Department of Eure. On this occasion, they distributed copies of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen, with two additional articles of their own, sowing doubt about the inviolability of private property, which, according to them, was ‘guaranteed until the nation has established laws on the matter.’ This, of course, sparked a fierce reaction from the rural population, very attached to land ownership! The next day, they were ‘booed, insulted, disarmed,’ and treated as ‘incendiaries and seditious.’ They owed their safety only to the authority of the president of the Department’s assembly, the Girondin deputy François Buzot, who was eager to restore peace to his district. Freed, they were escorted to Lisieux. The incident made waves in the department and had some repercussions in Paris, especially under Buzot’s influence, who was determined to make Momoro pay for the disorder caused in his district. In the October 12 session of the newly established National Convention, he personally attacked ‘the man I saved from the fury of the people, to whom this wretched man preached the division of land.’ Momoro and Dufour were recalled to Paris, and on September 23, the department’s public prosecutor thanked the Minister of the Interior, Jean-Marie Roland, as these individuals ‘had conducted themselves in a manner more likely to incite trouble than to propagate respect for property and personal safety.’” (Excerpt from Jean-Pierre Duquesne, confirmed by Grace Phelan since Jean Pierre Duquesne is not reliable at times but Grace Phelan does more correct work ).

In fact, those who proposed any significant challenge to property rights were often put in the minority, even within the Enragés or Hébertists, who focused more on economic issues like the maximum price law. There was a real fear of any attack on property rights, a fear heavily played upon by the Directory, including by Sieyès. One pretext was the closure of the neo-Jacobin club, which gathered figures like Prieur de la Marne, Xavier Audouin, Topino-Lebrun, Felix Le Peletier, Victor Bach, Antonelle, Jean Baptiste Drouet, René Vatar, and adjudant Jorry, among others. Following Victor Bach’s speech and the resurgence of the left in 1799, Poultier in his journal L’Ami des lois accused Victor Bach of advocating for an agrarian law. According to Bernard Gainot’s investigation into Victor Bach’s mysterious death, this led to a "Jacobine conspiracy" being staged by Sieyès and Lucien Bonaparte. The speech of Bach, as interpreted by his critics (presenting a “project for a constitution” which proposed a social program close to Babeuf’s system), was a true provocation. It provided conservatives with the perfect opportunity to demonstrate to the majority of deputies (who held police powers over the Tuileries buildings, including the Manège hall) that the neo-Jacobins, contrary to their legalistic demonstrations, only sought the overthrow of the Constitution of Year III and the abolition of private property (or more precisely, a "leveling" of wealth). By wielding the "red peril" scare, this provided an opportunity to close the Manège Hall and ruin the democratic strategy gathered around the Journal des Hommes libres, which aimed to unite militant networks from Paris and the provinces to form a majority in the Councils capable of gradually amending the Constitution of Year III into a "representative democracy."

What is the link to Carnot? Simply that Carnot was maybe likely part of this larger political class, more numerous than we once thought (without excusing Carnot, of course, and avoiding the false excuse of "it was his time"), which feared the agrarian law. Gracchus Babeuf had promoted this law a few years earlier, while Felix Le Peletier was more vague about it, perhaps intentionally, to better rally people, whether on property rights or progressive taxation, even though reform demands were there. (Felix Le Peletier later used the same tactic in the Manège club, where Victor Bach was more precise in his demands, showing Felix Le Peletier to be more prudent or strategic in gathering support.) Therefore, for Carnot, Felix Le Peletier, by his attitude, was less "suspicious" than Gracchus Babeuf.

Second theory.

The second theory I find plausible: Babeuf’s proximity to the Hébertists (Gracchus Babeuf had connections with many left-wing figures, including Albertine Marat, Robert Lindet, Jean-Paul Marat, the Robespierrists such as the Duplays, and even the widow of Chaumette, Pierre-Gaspard Chaumette, Jean-Nicolas Pache, former mayor of Paris, and even people like Vadier). Among these Hébertists, some had problems with the Committee of Public Safety, the General Security Committee, or the Convention. Two names that came up are Clémence and Marchand, who were imprisoned and later released in Year II. Joseph Bodson, one of Babeuf’s most important “lieutenants,” was a fervent Hébertist who resented members of the CPS, including Robespierre, for having executed Chaumette and Hébert (while Gracchus Babeuf became a Robespierrist at the end of his life). Rossignol, one of Ronsin's friends, was also involved in the Conspiracy of Equals. At this time, Carnot was part of the Committee of Public Safety. When he saw the names of these individuals again during his time as Director of the Directory, perhaps this raised a "red flag" for him. Here was Gracchus Babeuf, who had once been close to the Hébertists, surrounded by elements that had had conflicts with the government where Carnot held important positions. We know that Carnot was not close to the Hébertists, and vice versa. This likely didn’t help Carnot view Babeuf favorably, as he was surrounded by individuals Carnot mistrusted (it’s not a simple "good Hébertists vs. bad Carnot and CPS members," or good Carnot and CPS members vs Hebertists—it’s more complex).

@aedesluminis mentioned a letter Carnot wrote to Garrau, a very loyal Jacobin who remained a friend of Carnot during the Directory. Garrau warned him about a potential royalist threat, but Carnot replied, dismissing it as no threat and stating he was more concerned about the danger of extremists from the left—the Babeuf faction in this case. We know that Carnot made significant political errors, and one of them was overestimating the danger from the left while underestimating the royalists.

According to historian Claude Mazauric, Carnot was the most fervent advocate of Babouvist repression, wanting to extend many arrests, though it seems he paradoxically protected Felix Le Peletier and other figures. Barras had reservations about this (one of the rare good actions from Barras in this case). However, according to Fouché’s memoirs, Barras might have been more responsible for the repression of the Babouvists than Claude Mazauric suggests. Fouché reportedly convinced Barras that Gracchus Babeuf (who had long since broken with Fouché) was a threat. This is plausible, especially when we realize how much harm Fouché did to the Babeuf family once he became Minister of Police. He listed Gracchus Babeuf’s widow, Marie-Anne Babeuf, in the list of Jacobins to be arrested in 1801, at a time when Jacobins were despised and victims of violence following the royalist-provoked Saint-Nicaise Street bombing. And in 1808, during the Malet Conspiracy, Fouché, now Minister of Police, ordered the arrest of Emile Babeuf, who only escaped because he was abroad due to work, while Marie-Anne Babeuf underwent a harsh interrogation (though she was known for her strong character and probably wasn't intimidated, given that she had survived worse trials, notably under the Directory). It’s chilling to think that, during a time when Gracchus Babeuf mistakenly thought of Fouché as a friend, he once wrote that he trusted Fouché with his children, as you can see in this post here: https://www.tumblr.com/nesiacha/770322937812336640/one-of-the-creepiest-things-among-the-many?source=share.

However, there’s a big "but." For now, I have only the version from historian Claude Mazauric and Fouché’s memoirs, which are sometimes unreliable (understatement). So, while I have no affection for Barras, I’m more inclined to believe Mazauric unless other elements come to corroborate it. Although when Fouché speaks of the agrarian law to scare people, it seems very plausible. Knowing Fouché, who showed no mercy to those who became his enemies (and after all, Gracchus Babeuf publicly denounced him in his journal), this could be true.

Why was Gracchus Babeuf executed along with Darthé?

Gracchus Babeuf, in my view, put forward a defense of rupture, at least initially, as you can see here: https://www.tumblr.com/nesiacha/764082552563761152/three-brave-defenses-by-revolutionaries-tried?source=share. For those who don't want to visit the link, here’s what Babeuf did: He showed remarkable courage, taking full responsibility for the "Society of Democrats," acknowledging all attacks against the Directory, stating, "The decision of the jurors will solve this problem...: will France remain a Republic, or will it return to a monarchy?" Babeuf fought, refused to answer, and contested many points. He was sentenced to death with Darthé (who remained stoic and mute, refusing to answer questions). Some say Charles Germain almost got the death sentence, but he was finally sentenced to deportation .

Gracchus may have been condemned to death as the leader of the Conjuration of Equals. His defense saved many of his colleagues, but it wasn’t the only reason why other co-defendants avoided execution. Babeuf's trial is well-known thanks to Pierre-Nicolas Hésine, a revolutionary who sheltered the Babeuf family during the trial and published Le Journal de la Haute-Cour or L’Echo des Hommes Sensibles et Vrais throughout the trial. The terrible journey in the iron cage from Paris to Vendôme, where the trial took place, moved public opinion. Teresa Poggi, Philippe Buonarroti’s partner, and Marie-Anne Babeuf, who was pregnant, made the journey on foot under arduous conditions for support the two mans.

Antonelle wasn’t idle in trying to save his co-defendants, although he distanced himself from Gracchus Babeuf due to Babeuf’s irresponsible attitude and their differences on certain issues. Gracchus made foolish moves, like leaving a list of people associated with him in his room, which Pierre Serna suggests was child's play for the police to find. According to Laura Mason, the police found hundreds of documents in an apartment near the center of Paris, including underground pamphlets, insurrection decrees, and instructions to confederates to incite rebellion. Gracchus was irresponsible in this regard, which greatly frustrated his more sensible comrade Antonelle. Antonelle distanced himself, particularly on how to achieve the revolution. I simplify, but for this noble revolutionary, the revolution should be saved through the ballot box and by fighting the system from within, though history would prove him wrong. Here's what Antonelle wrote: "The act of insurrection is the dream of a sick man… The more I think about this too frivolous subject, the more I remain convinced that this great conspiracy was reduced to the petty annoyances of a few disgruntled minds, the pastimes of some idle people who shared their thoughts." The problem was also that Gracchus didn’t take the necessary measures for a clandestine operation, inadvertently putting many involved—whether directly or indirectly—in danger.

But Antonelle, in his journal, also fought to save as many of the co-defendants as possible.

Here is an excerpt from Pierre Serna: "He participated in the Vendôme trial against Babeuf’s accomplices and played a key role in saving almost all of the defendants ».

Réal was also active, just like Vatar and Lebois, in defending the co-defendants (Vatar and Lebois had, a few years earlier, campaigned for the release of Marie-Anne Babeuf, who had been arrested for handling the subscriptions of her husband’s journal. Her arrest lasted only two days thanks to them, according to what I understand).

Moreover, among the co-defendants was an important figure who couldn’t possibly be dead, as he played a symbolic and crucial role in being one of the men who arrested Louis XVI: Jean-Baptiste Drouet. Even some reactionaries panicked when they saw his name among the list of co-defendants in the Babeuf trial, even though others supported the accusation.

Here are some excerpts about Jean-Baptiste Drouet: 'The submission of J.-B. Drouet's case to the Legislative Body in the summer of 1796 crystallized the anger of the democrats. From the moment the Council of Five Hundred began debating the inviolability of the deputy, the press entirely lost interest in other aspects of the case. On the day of Drouet’s arrest, the Directory declared that the police had apprehended him in the act of conspiracy. The democrats now demanded evidence that could justify the imprisonment and trial of a sitting deputy. Drouet claimed he had been arrested while meeting political allies to discuss an official letter he was drafting. The police report, his defenders pointed out, confirmed his statement, as it only mentioned the letter from Drouet and commercial documents belonging to the host of the meeting. 'Thus, in the eyes of the commissioner and his assistants, there were no actions, words, or writings that externally indicated any kind of conspiracy; therefore, there was no flagrant crime.' If Drouet had not been arrested in the act of conspiracy, the Directory had violated his inviolability, thus violating the constitution. If the Legislative Body repeated this act by allowing a trial, it would likewise violate the constitution. 'If the constitution is violated by its main guardians, all is lost; for, how can you punish a man who has conspired against the constitution if you are the first violators?' Didn’t the Terror originate from such violations?’

None of the arguments from Lamarque, nor from the other defenders of Drouet, managed to influence the Legislative Body. The Council of Five Hundred allowed the case to go to the Council of Ancients, which voted for a trial and set up a high court authorized to judge a representative of the people. Insulted but not defeated, the democratic press continued to defend Drouet by publishing speeches, letters, and satires. Méhée even offered to defend Drouet, fearing that more qualified men, faced with the threat of royalist violence, would hesitate to offer their services.

While the democrats focused on the trial, news spread that Drouet had escaped and disappeared. Drouet was able to flee because his case had become too embarrassing for the Directory. The Directory, which had arrested the conspirators denounced by Grisel, had assumed that the case would be widely approved, without considering the obstacle presented by the reputation of the man who had arrested the king at Varennes. Despite irrefutable evidence, despite Grisel’s denunciation, and especially despite the fact that the two chambers of the Legislative Body, by a large majority, had approved the trial, the charges against Drouet continued to provoke the anger of the democrats. Perhaps the Directors hoped that by letting Drouet escape, they would shift attention back to Babeuf, a less credible figure, and thus achieve the glory they expected from his prosecution.

However, the escape came too late. Fearing that the prosecutions against Drouet and the harassment of other democrats signaled a new reaction, and convinced that the Directors had violated the constitution, the democrats were determined to follow the trial of Babeuf closely. This trial, which involved a total of sixty-three other defendants, lasted three months, from the winter of 1796 to the spring of 1797, and became a fierce battle between the Directors and their democratic opponents. During longer and more radically covered proceedings than any other trial during the French Revolution, each side accused the other of betraying the promises of the Revolution, presenting its members as the heralds of the only true Republic.' (Excerpt from the article by Laura Mason, "After the Conspiracy: the Directory, the Press, and the Affair of the Equals")

So here we see that the press, the impact of the democrats, and certain prisoners influenced the judgment, in addition to Gracchus’s defense. I think we can now understand why only Gracchus and Darthé were executed. Between Gracchus’s defense, where he fought fiercely to at least save as many of his colleagues as possible, and Darthé, who was stoic and did not respond (Gracchus and Darthé knew they were going to die, as they spent their time sharpening a blade to attempt suicide), the fact that Gracchus was among those revolutionaries advocating for the infringement of property rights through agrarian reforms (a small group of revolutionaries who scared many political factions, whether in 1789, 1792, or even more so under the Directory) likely worked against him.

As for Carnot, the fact that Gracchus was part of this group of revolutionaries who surrounded themselves with people who had had problems with the Committee of Public Safety in 1794, as we saw, must have made his case even more difficult in Carnot’s eyes. Nevertheless, even in his repression of the Babouvists, Carnot did try to save some revolutionaries, as we saw in the case of Félix Le Peletier, which is to his credit.