#Late Tang Dynasty Period

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

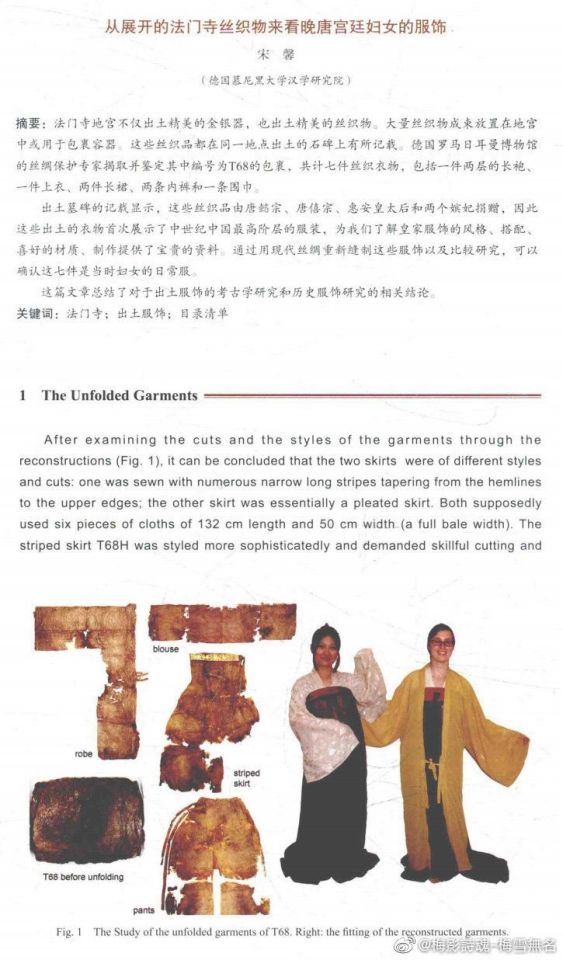

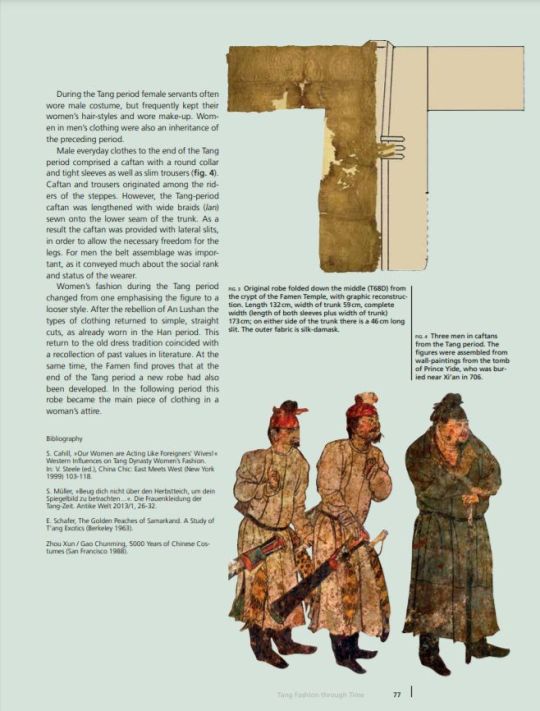

【Historical Reference Artifacts】:

Tang Dynasty Hanfu Relics Unearthed from the Underground Palace of Famen Temple

Tang Dynasty Hanfu Relics Unearthed from the Underground Palace of Famen Temple:直領對襟團窼紋長衫(袍)

[Hanfu · 漢服]Chinese Tang Dynasty(618-907A.D)Traditional Clothing Hanfu Refer to the relics of Famen Temple

Late Tang Dynasty Period Noblewoman Attire

_______

👗Hanfu & Photo: @佳期閣

🔗Weibo:https://weibo.com/6614078088/N2FqMr2U6

🛍️ Tabao:https://item.taobao.com/item.htm?spm=a1z10.3-c.w4002-21517525888.12.3ed71c81WrejrM&id=722671302802

_______

#chinese hanfu#Tang Dynasty(618-907A.D)#hanfu history#hanfu accessories#hanfu#hanfu artifacts#chinese historical fashion#chinese historical makeup#chinese history#chinese style#chinese#chinese attire#chinese traditional clothing#chinese culture#直領對襟團窼紋長衫(袍)#Famen Temple#汉服#漢服#佳期閣#Late Tang Dynasty Period#chinese fashion#china

152 notes

·

View notes

Text

All the Historical Mermay’s together!

I had a lot of fun with this mermay prompt list by chloe.z.arts and they turned into a pretty cool collection of illustrations!

Prompt list by chloe.z.arts on instagram.

I am the artist! Do not post without permission & credit! Thank you! Come visit me over on: instagram.com/ellenartistic or tiktok: @ellenartistic

#historical mermay#mermay 2023#collection of mermaids#lnart#ellenart#historically inspired#historical fashion#it’s gonna be mermay#ancient egypt#ancient greece#tang dynasty#french medieval#italian renaissance#mughal empire#edo period#late victorian era

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

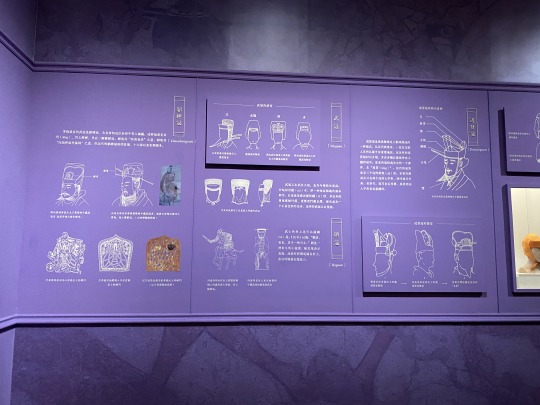

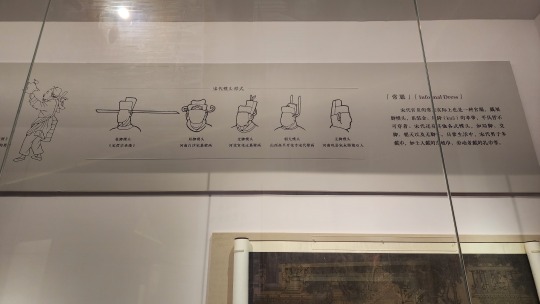

April 20, Beijing, China, National Museum of China/中国国家博物馆 (Part 3 – Chinese Historical Fashion Exhibition):

Another cool exhibition that I visited while at the museum, showcasing popular fashion from different dynasties, historical artifacts, and some other relevant artifacts that gave a glimpse into the fashion of different dynasties. What's even cooler is that you can visit this exhibition virtually! (the site is in Chinese but I highly recommend it to everyone, there's so much more to the exhibition than the pictures I post here) Note that this exhibition does not only include historical hanfu, but also historical fashion of the 少数民族 that ruled some of the dynasties. This post will be pre-Ming fashion, and next post will be Ming and Qing era fashion. The reason is because Ming and Qing dynasties are the two most recent dynasties, so there are a lot of surviving artifacts from these two dynasties, which means there are 30+ pictures total and I couldn't fit them all into a single post.

First is a recreation of Han-era (202 BC - 220 AD) hanfu. The woman on the left is wearing a one-piece robe called a qujushenyi/曲裾深衣. The man on the right is wearing the outfit characteristic of Eastern Han dynasty (25 - 220 AD) civil officials, a combo of jinxianguan/进贤冠 hat and zaochaofu/皂朝服 clothing (皂 here means the color black, as in the word "青红皂白", or "blue and red, black and white"):

Left: model of a Han-era magpie tail cap/queweiguan/鹊尾冠 (you can see the influence of these Han-era men’s hats on the outfits of male characters in modern xianxia art). Right: recreation of a Han-era bian/弁 hat (the headscarf-like piece tied beneath the chin):

Line drawings of different hats worn by different types of officials based on artifacts and murals. The center and left sections are different hats of military officials (wuguan/武官 in Chinese), and the right section is different hat styles of civil officials (wenguan/文官 in Chinese).

Jumping back, this is a Warring States period (476 - 221 BC) iron daigou/带钩 inlaid with gold and jade and decorated with dragons. Daigou are basically belt buckles where the flat end is attached to one end of the belt, and the hook will hook into slits in the other end of the belt, so this is an extra fancy belt buckle:

On to Tang-era (618 - 907 AD) hanfu. From the left to right these are: the regular outfit of early Tang dynasty officials (color varies by rank, red is worn by fourth and fifth rank officials), the outfit of a female servant in early to mid Tang era, the ceremonial outfit of a Tang dynasty emperor, and the outfit of noblewomen in late Tang to Five Dynasties era (907 - 960 AD):

Song-era hanfu (front two) and Yuan-era Mongolian fashion (back two). Front left is the formal attire of Southern Song dynasty (1127 - 1279) civil officials (color varies by rank, red is worn by fourth and fifth rank officials), and front right is the regular outfit of women in Southern Song dynasty. Back left is the formal attire of Mongolian noblewomen in Yuan dynasty (1271 - 1368), and back right is the regular outfit of Mongolian men in Yuan dynasty.

Replicas of painted clay sculptures of women from Northern Song dynasty (960 - 1127), the original sculptures are in Hall of the Holy Mother/圣母殿 of Jinci Temple/晋祠 in Shanxi province:

By the way, in the case of Song dynasty, the descriptor "northern" and "southern" basically indicate time periods within Song dynasty (you can refer to the beginning of this post where I explain this in more detail).

And line drawing diagrams of different styles of futou/幞头 hats in Song dynasty based on paintings, murals, and other artifacts:

#2024 china#beijing#china#national museum of china#historical fashion#historical clothing#chinese historical fashion#hanfu#mongolian historical fashion#fashion history#chinese history#chinese culture#history#culture

140 notes

·

View notes

Text

"In historical context though-"

This book has potatoes and chilis in supply and demand when these were not traded until the late 15th century... and not used for cuisine and a foods crop cultivator in China well into the 17th and 18th century almost 200 years later. Folding fans that are seen abundantly were not popularized until the 13th century. Taoism was at its largest during the Warring States period of 450 BCE–c. 300 BCE with the epigram of Tao Te Ching. Confucianism became the abundant practice as of 206 BCE to 220 BCE with the authoring of The Analects. It uses fabricated province names for real world Chinese provinces that are relegated to a simple five, when there are of 22 (claimed) and have been the most stable to survive since the Yuan dynasty 1271-1368. Idioms used vary through the centuries and are still a staple of modern day vernacular. The version of futou Jin Guangyao alone wears was a wushamao (乌纱帽), used in the Ming dynasty 1368-1398. Futou was made a part of ministerial and court attire during the reign of Emperor Wu 560 BCE.

The author has said it has no standing Imperial Dynasty it takes place in and has borrowed aesthetics from the Han, Wei-Jin, Song, Tang, Ming and even Qing. All of which had seen several turns of dynasty from Han to Mongol to Han divine rulings. So no, there is no historical context to take in regard when it comes to Madam Yu's overt abuse, to Jiang Cheng's abuse, the clan's classisms and hypocrisy.

It was written in an alternate fantasy of China without this context of real world history and through the lens of modernity of its author. Do not use a history that does not pertain to a novel that is not has not and was never called historical.

129 notes

·

View notes

Text

#TextileTuesday:

Textile with Animals, Birds, and Flowers Eastern Central Asia, late 12th–14th century Silk embroidery on plain-weave silk 14 5/8 x 14 7/8 in. (37.1 x 37.8 cm) Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York 1988.296

"This textile demonstrates the longevity of motifs in eastern Central Asia. The placement of animals—a spotted horse, a rabbit, and two deer (or antelope)—at its cardinal points is a compositional device that began to appear in the region during the Han dynasty. The birds on the piece, especially the parrot, entered the Central Asian repertoire during a second period of strong Chinese influence, the Tang dynasty. The floral background's central motif of lotus blossoms, a lotus leaf, and a trefoil leaf was seen in Central Asia and North China but became widespread during the Yuan dynasty."

#animals in art#birds in art#textile#Textile Tuesday#embroidery#silk#Central Asian art#Asian art#Metropolitan Museum of Art New York#animal iconography#medieval art

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

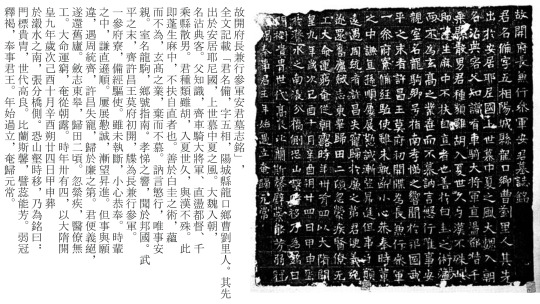

Tomb of An Bei 589 CE. Sogdian tomb.

I couldn't find the translation for the epitaph for this one.

"Differently from the other tombs quoted in this paper, Anbei’s tomb was not excavated by archaeologists, but found and looted by the robbers, therefore the archaeological context of this tomb, even the date of this accidental finding are lost. Until now, all we know is that this tomb robbery happened someday between 2006 and 2007. Several stone figurines, a funerary couch and Anbei’s epitaph stone were found in the tomb. Two stone figurines, parts of the base of the couch and the epitaph are now exhibited in the Tang West Market Museum in Xi’an (Fig.20), four panels belonging to the private owners, including two processing and two banqueting scenes, were published, too (Fig.21).

Although owning the typical Sogdian name An, which means his ancestors migrated into China from Bukhara, his homeland was described in a completely different name, the state of Anjuyeni, which was never recorded by any source before. An’s family moved to China during the Northern Wei dynasty, some of his family members once served in the Bureau of Tributaries. For the court, it’s also an usual way to adopt expatriate immigrants to work in the diplomatic system. Anbei’s father, An Zhishi, served as a middle-rank commanding officer among the honour guards of the court.

As a, likely, third generation immigrant, Anbei’s life depicted in the epitaph was very brief, too. Except for the usual eulogies commonly written in every epitaph, two main parts of his experience were emphasized: his mercantile ability and simple bureaucratic career. The one who wrote the text made a metaphor, assimilating Anbei with two famous ancient Chinese merchants, Baigui and Xiangao during the Eastern Zhou Period (approximately between 8th c. - 3rd c. BC); After that, Anbei’s only short official career as a very lower status clerk of the military headquarters of vassal leader Xuchang was recorded, probably happened in 575 AD when he was 20 years old. Soonafter the Northern Qi was replaced by Northern Zhou dynasty in 577 AD, Anbei returned home in Luoyang, the place where he died and was buried in 589 AD at the age of 34.

The motivation for me to list this robbed tomb here, together with the other tombs which have detailed background obtained through scientific archaeological excavation is, however, mainly not for its elaborate funerary couch, but because of his distinctive identity depicted in the epitaph. Prior to the discovery of Anbei’s tomb, the deceased of all five tombs which constituted the most important foundation of the studies of the foreign immigrants in early medieval China, namely the tombs of Lidan, Kangye, Anjia, Shijun and Yuhong, owned high-ranked official positions such as head of a prefecture or Sabao, which may result in a misconception that only aristocrats of the foreign immigrants could be buried with such elaborate funerary furniture. However, Anbei’s tomb provided an additional possibility about the status of the tomb occupant who used the stone funerary furniture. What is expressly shown in the epitaph, during his 34-year-long life, Anbei was just a very ordinary person, without any notable ancestry from homeland, neither held any high-ranked post, nor received anyone as a posthumous reward.

Except for the basic information above, there is also a remarkable narration during the introduction in the beginning of Anbei’s epitaph, which may reflect the collective mindset among most of the foreign immigrants in China and their efforts in social integration, ‘Although he is a foreigner, after a long life in China, there is no difference between him and the Chinese’.

-Yusheng Li, Study of tombs of Hu people in late 6th century northern China

210 notes

·

View notes

Text

Statue of a goddess, probably Nehemetaui or Nebethetepet Late Period–Ptolemaic Period Dynasty 27–30 550–300 B.C.

The shrine-shaped sistrum sound-box worn as a crown by this figure indicates that either the goddess Nehemet-aui, the consort of Thoth, or Nebethetepet, a manifestation of Hathor, is represented. The features of the goddess suggest a date to the end of the 26th dynasty, or the 30th dynasty. As the kings of the 30th Dynasty built important buildings including a temple to the goddess Nehemet-aui at Hermopolis, the seat of the god Thoth, it is plausible this statue is Nehemet-aui.

H. 17.8 × W. 4.3 × D. 10 cm (7 × 1 11/16 × 3 15/16 in.). H. (with tang): 20 cm (7 7/8 in.).

#Statue of a goddess#Nehemetaui#Nebethetepet#Late Period–Ptolemaic Period#statue#egyptian statue#ancient artifacts#archeology#archeolgst#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations#ancient egypt#egyptian history#egyptian art

120 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello! I was wondering about the evolution of kimono styles throughout Japanese history. I have a rather static image of what they look like, but being into general historical fashion made me question if it really was as unchanging as I imagine. For example, the Edwardian and Victorian silhouettes, or Tang dynasty qixiong and Ming dynasty aoqun look very different from each other. Did kimono have they own trends that amateurs don't know about?

Part 2: Hi, just to clarify, I mean general fashion trends, for both men and women (though I'm leaning more women). Also, I was wondering if there was a disparity between geimaiko trends which separated them from "normal" women. In certain cultures, courtesans and entertainers were trendsetters. The kimono as we know it today, the kosode, has been around for approximately 600 years or so. In that time not much has changed in its shape, but rather all changes have been made in length and material. Until the late 19th century almost all kimono were worn while dragging along the floor, so they were longer than their contemporaries. In terms of material, obviously the richest members of society had the most lavish kimono, which are the ones that have survived in the highest quantities to this day. From what we know as the "modern kimono," which dates to the Edo Period (1603-1868), we know that goshodoki (views of the nobility) were a very popular motif on kimono for both women and younger girls (kosode and furisode) and were worn on their best kimono. Goshodoki began to fall out of favor just before the Meiji Period, so around 1840-1850, when Japan began to experience upheaval and Western influence. When it comes to influences and influencers, The Edo Period once again strictly controlled what people could wear due to sumptuary laws. There were many ways that people got around these laws, but for the most part you had to dress in what was prescribed for your social class. Courtesans were in a class above those of the "normal" people, so they weren't setting any trends for clothing (although they did with their hair). However, it was the geisha who were trendsetters for the common people as they belonged in the same class. What a popular geisha wore was quickly copied by other geisha, which was then in turn copied by townswomen. The only real control that they had over their wardrobe were the patterns on their kimono and obi, which, although still regulated, could be presented in unique ways or new color patterns. With the end of the Edo Period came the end of sumptuary laws and a fair degree of Western influence in everyday Japanese life. Kimono were now shorter as people no longer wore them dragging on the floor (except for geimaiko) and motif placement had to change to due to the adoption of Western furniture. Kamon (family crests) on women's kimono grew smaller but with them came added motifs on shoulders that weren't seen before as now most motifs on kimono couldn't be viewed properly on Western style chairs. Western style motifs and artistic styles also began to be adopted in the early 20th century in a time known as the Taisho Roman. Kimono production boomed during the Taisho Period (1912-1926) as Japan was expanding its foreign territories and the economy soared. The different types of motifs and and the sheer richness and sparing of no expense was something that has never been seen before and will never be seen again. Sadly then came World War II, production stopped, and when it resumed it was much more subdued as people moved to Western clothing as their main clothing of choice. Kimono were still being produced throughout the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s with a fair amount of regularity, but the burst of the bubble economy in the 1990s lead to a sharp decline in kimono production. It's only been within the last 10 years or so that a "Kimono Renaissance" has been taking place that has lead to both foreigners and Japanese nationals rediscovering the iconic garment, with an uptick in indie designers leading the way in new fashions rather than older fashion houses ^^

20 notes

·

View notes

Note

do you know roughly what time period mount hua takes place? like if its during a specific dynasty or anything

most murim/wuxia take place in a very vague ancient time period that, unless the author specifically mentions what year it is, its impossible to tell.. as for rotmhs i dont think a specific year/dynasty has ever been mentioned so u pretty much have free range to put rotmhs in whichever dynasty feels right to you

ive seen some people speculate on time periods based on the type of hanfu characters wear but that hardly ever holds up seeing how in most wuxia media (mostly xianxia but i digress) that take place in this vague-wuxia-timeline, the robes are often mashed together into a conglomerate of a bunch of different dynastys styles, that or theyre purely fictional and only exist to be aesthetically pleasing and more xianxia-like..

purely my own headcanon though i like to imagine current timeline rotmhs takes place mid to late tang dynasty, chung myung having lived his life as geomjon some point in the early years of the sui dynasty and into the tang dynasty..or something.. *scratches ass* im still working on the math

#a lot of unnecessary information u didnt ask for my bad ive just seen people claim that some stories take place in THIS era or THAT era#even though they dont..based on zero concrete evidence..and that kind of ruffles my feathers for no reason at all..im so nit picky

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy Gushiwensday Shabbes, we've got a Du Mu tonight! Here's "On the subject of water pavilion of Kaiyuan Temple at Xuanzhou." It includes a little foreword by Du: "Below the pavilion are winding creeks, between which people dwell."

The relics of the Six Dynasties are now just manuscripts fading to air but the sky's mild clouds are as lazy now as they were in ancient times. Birds come and birds go through the color of the mountain; people sing and people weep among the sound of water. Rain in deep autumn, door-curtains for a thousand houses, and at sunset on the balcony, a flutelike wind. Feeling melancholy because I'll never meet Fan Li, who disappeared into the jagged mist and trees at Five Lakes.

Original text and notes under the cut.

题宣州开元寺水阁

阁下宛溪,夹溪居人。

六朝文物草连空,天淡云闲今古同。 鸟去鸟来山色里,人歌人哭水声中。 深秋帘幕千家雨,落日楼台一笛风。 惆怅无因见范蠡,参差烟树五湖东。

I'm really not sure what all Du Mu was going for with this one... I just tried to make my translation kind of abstruse because it's what he would want. Here are some notes, though!

Kaiyuan Temple at Xuanzhou --- in modern Anhui province on the Wanxi River.

relics of the Six Dynasties --- specifically 文物 cultural relics. The term is ill-defined even now, including vehicles, clothing, ritual objects, and documents. We're not totally sure what it meant in the Tang Dynasty. But either way, the Six Dynasties period ended about 250 years before this poem was written.

manuscripts fading to air --- a lot of ways to interpret this one. 草连空 "grass joining emptiness" is the gloss I went with. As Laurence pointed out it's fun that this line ends with 空 and then next line in the couplet starts with 天 since they can both refer to the sky, so I wanted to end my line with "air."

through the color of the mountain --- seriously, what does 山色里 mean? I wasn't confident enough about any interpretation to do anything other than literal, although Laurence points out that 色 is often used poetically to mean scenery. My translation is a little intentionally occluded because I like the ambiguity and the possible alternate image of birds emerging from a painting of a mountain, which feels very Mushi-shi to me.

deep autumn --- maybe better translated as "late autumn" but the literal is so juicy.

door-curtains --- Sounds a little awkward. I feel like the best vibes-based translation of 帘幕 is maybe "awning," but in the West awnings are curved, so you don't get the image of rain as a curtain.

Fan Li --- a politician and businessman from the end of the Spring and Autumn Period, some 1300 years before the time of this poem's writing. As I understand it he was being pursued by his former lord and decided to disappear.

jagged mist --- 参差 fantastic word, maybe meant to convey uneven or patchy, but can also mean serrated.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rotating volley technique possibly exist in Sengoku Japan

Previously in my Nagashino post, I mentioned that the popular story of the rotating volley tactic is considered dubious. The main reason for it is that the source of it is completely unknown. At some point it became a just-so story in the Edo era, and was affirmed as fact by the Meiji government, clearly without properly checking its veracity.

Even Oze Hoan’s Shinchouki text (this is not Ota Gyuuichi’s Shinchoukouki), which is already considered dubious in the first place, only recorded that the Oda forces had 3000 guns. It also did not describe a rotating volley tactic.

However, even if this artillery tactic is not explicitly used in the Nagashino battle, there is proof that the Japanese troops are aware of and seemingly well-trained trained in this tactic at least as of the late Sengoku. It was known to have been used in Hideyoshi’s Korean war, as recounted by the people of Ming and Joseon:

In 1593, for example, Ming General Song Yingchang (宋應唱, 1536-1606) noted that the Japanese employed the musketry volley technique, writing that he feared the Japanese would “break into squads and shoot alternately against us (分番休迭之法).” In 1595, Korean King Sŏnjo shared the same apprehension that “the Japanese [would] divide themselves into three groups and shoot alternately by moving forward and backward (若分三運, 次次放砲)?”

From "Big Heads, Bird Guns and Gunpowder Bellicosity: Revolutionizing the Chosŏn Military in Seventeenth Century Korea", a thesis by Kang Hyeok Hweon.

Maybe there were records of this method employed in domestic battle that the researchers just haven’t discovered yet. For now it’s still unclear where and when the Japanese troops learned of this. Just that they seem well trained enough in it during the battles mentioned above.

It’s noteworthy, however, that this rotating volley tactic was already a very well-known method of warfare in China as early as 750s AD in the Tang dynasty. First, it was used by archery and crossbow units. Then, they evolved the technique to be used with guns. Below is a description of a battle in the year 1414:

“The commander-in-chief (都督) Zhu Chong led Lü Guang and others directly to the fore, where they assaulted the enemy by firing firearms and guns continuously and in succession. Countless enemies were killed.”

From “The Gunpowder Age: China, Military Innovation, and the Rise of the West in World” by Tonio Andrade.

Especially noteworthy is that the enemy’s army described in this passage are also mounted troops. It’s not impossible that the Japanese somehow learned of the above literature from Ming, and then put it in practice, though without proof we cannot assume too much.

King Seonjo’s description, specifically, sounds like the kind of rotating volley usually described in the Nagashino stories. This brings to mind how many times I’ve seen cases of Edo period stories inserting anachronistic objects or settings into narratives of the past, so it could be how this legend was born. Perhaps the Edo storytellers took the volley technique that wasn’t known or used until later, and just assigned it to Nagashino for dramatic flair.

#artillery#Firearms#resource#research#japanese history#imjin war#bunroku keicho war#samurai#sengoku#Sengoku Era#Sengoku period#Warring states#Warring States Period#Warring States Era

23 notes

·

View notes

Photo

【Historical Artifacts Reference】

Skirt Pattern Reference:Tang Dynasty Murals<Mother and Daughter Doner>in Cave 12 of Dunhuang Mogao Grottoes. ※Due to the mural paint has long been oxidized, resulting in color differences※

【Skirt Restoriation And Way Of Wearing Reference】

※Let the inner skirt show through the side※

China Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms Period:Murals From Tomb of Wang Chuzhi王處直(862–922)

China Tang Dynasty Murals in Cave 159 of Dunhuang Mogao Grottoes.

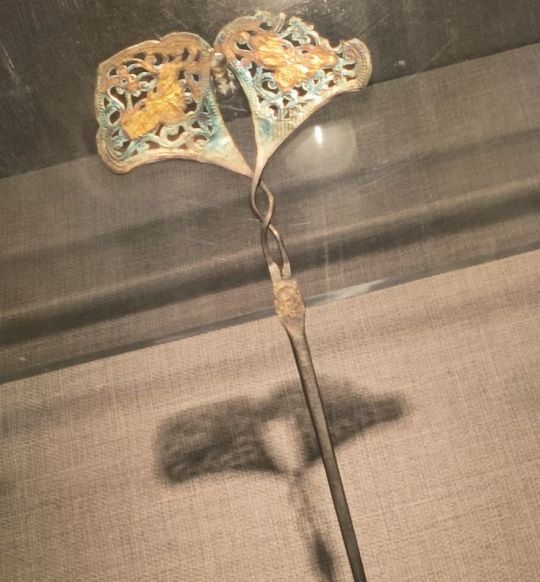

【Tang Dynasty Hairpin Artifacts】

[Hanfu · 漢服]Chinese Tang Dynasty(618-907A.D)Traditional Clothing Refer to Tang Dynasty Dunhuang Mogao Grottoes Murals

Mid-Late Tang Dynasty Women's Attire

————————

📸Recreation Work:@-盥薇-

👗 Hanfu: @时合岁初传统服饰

🔗Weibo:https://weibo.com/3942003133/MC5n4viSt

————————

#Chinese Hanfu#Tang Dynasty(618-907A.D)#hanfu#chinese traditional clothing#chinese history#Mid-Late Tang Dynasty Period#hanfu history#chinese fashion history#ruqun#齊胸衫裙 qixiong shanqun#pibo 披帛#Chinese Culture#china#chinese#Huadian(花钿)#hanfu accessories#hanfu artifacts#Dunhuang Mogao Grottoes Cave#漢服#汉服#recreation#-盥薇-#时合岁初传统服饰#Tang Dynasty Hairpin Unearthed from the tomb of Wu King Wife Tomb#tang dynasty hairpin

236 notes

·

View notes

Text

Okay expanding on something I was going to put in the tags but it drives me nuts when people say "ancient tang dynasty China."

There's a few reasons for this:

The Tang dynasty began in 618 CE, which even if we're only looking at western historical periodization is arguably the very tail end of late antiquity. Calling the WHOLE DYNASTY ancient because it begins in the end of what the west calls "ancient" feels silly.

It ends in 907 CE, which again, by western periodization is explicitly medieval.

Using western European historical periodization for Chinese history is dumb.

Chinese academic studies typically group these periods differently from the western periods. In English language journals, the Tang studies society journal actually includes the Sui (581 CE), Tang, and Five Dynasties periods. (Basically ending just before 1000 CE.) The journal of Song-Yuan studies actually includes "Song, Liao, Jin, Xia, and Yuan dynasties," and covers "middle period China."

You might say "oh medieval is a middle period! So obviously what comes before medieval is ancient, and therefore the tang dynasty is ancient."

But the journal "Early China" covers "all aspects of the culture and civilization of China from earliest times through the end of the Han dynasty period (CE 220)." Meaning that anything post-Han dynasty isn't ancient enough to be included in the ancient China journal.

It's probably MORE Accurate to say that Sui-Tang China is their equivalent to the "Early Middle Ages" and Song-Yuan is the "High Middle Ages." And we just call the Song-Yuan period "middle China". Lots of historians call tang dynasty "early medieval" for a reason!

"but it could be late antiquity, which is still ancient!" But late antiquity is defined in relationship to the remains of the ancient Roman empire which is incidentally, not near China.

My classical Chinese translation class focused on reading ancient Chinese didn't include anything from the tang dynasty because you need to be familiar with ancient Chinese before you get to tang literature

I'm a medievalist

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

April 14, Xi'an, China, Shaanxi History Museum, Qin and Han Dynasties Branch (Part 3 – Innovations and Philosophies):

(Edit: sorry this post came out so late, I got hit by the truck named life and had to get some rest, and this post in itself took some effort to research. But anyway it's finally up, please enjoy!)

A little background first, because this naming might lead to some confusions.....when you see location adjectives like "eastern", "western", "northern", "southern" added to the front of Zhou dynasty, Han dynasty, Song dynasty, and Jin/晋 dynasty, it just means the location of the capital city has changed. For example Han dynasty had its capital at Chang'an (Xi'an today) in the beginning, but after the very brief but not officially recognized "Xin dynasty" (9 - 23 AD; not officially recognized in traditional Chinese historiography, it's usually seen as a part of Han dynasty), Luoyang became the new capital. Because Chang'an is geographically to the west of Luoyang, the Han dynasty pre-Xin is called Western Han dynasty (202 BC - 8 AD), and the Han dynasty post-Xin is called Eastern Han dynasty (25 - 220 AD). As you can see here, in these cases this sort of adjective is simply used to indicate different time periods in the same dynasty.

Model of a dragonbone water lift/龙骨水车, Eastern Han dynasty. This is mainly used to push water up to higher elevations for the purpose of irrigation:

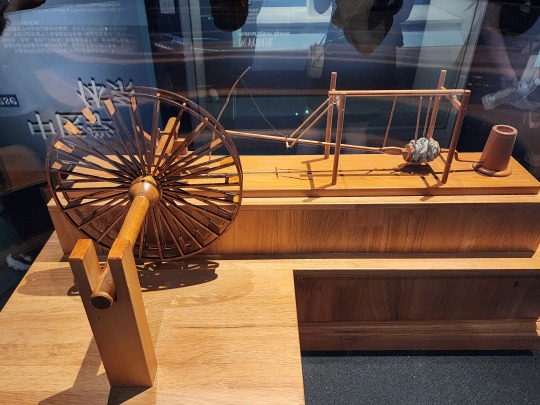

Model of a water-powered bellows/冶铁水排, Eastern Han dynasty. Just as the name implies, as flowing water pushes the water wheel around, the parts connected to the axle will pull and push on the bellows alternately, delivering more air to the furnace for the purpose of casting iron.

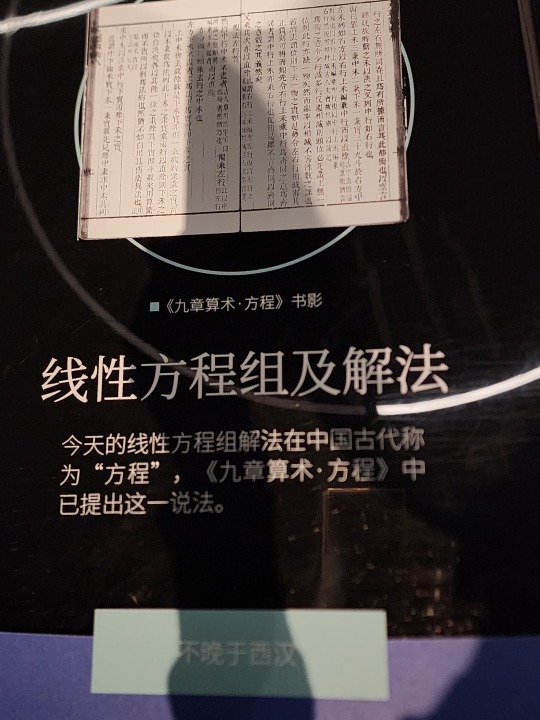

The Nine Chapters on the Mathematical Art/《九章算术》, Fangcheng/方程 chapter. It’s a compilation of the work of many scholars from 10 th century BC until 2 nd century AD, and while the earliest authors are unknown, it has been edited and supplemented by known scholars during Western Han dynasty (also when the final version of this book was compiled), then commented on by scholars during Three Kingdoms period (Kingdom of Wei) and Tang dynasty. The final version contains 246 example problems and solutions that focus on practical applications, for example measuring land, surveying land, construction, trading, and distributing taxes. This focus on practicality is because it has been used as a textbook to train civil servants. Note that during Han dynasty, fangcheng means the method of solving systems of linear equations; today, fangcheng simply means equation. For anyone who wants to know a little more about this book and math in ancient China, here’s an article about it. (link goes to pdf)

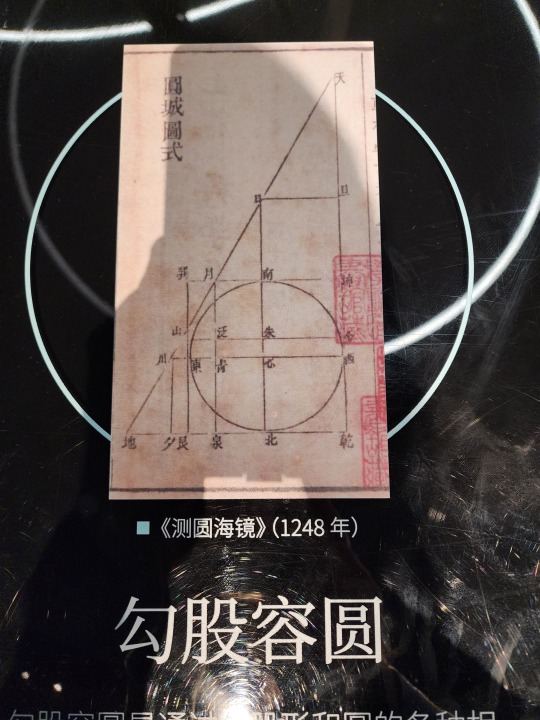

Diagram of a circle in a right triangle (called “勾股容圆” in Chinese), from the book Ceyuan Haijing/《测圆海镜》 by Yuan-era mathematician Li Ye/李冶 (his name was originally Li Zhi/李治) in 1248. Note that Pythagorean Theorem was known by the name Gougu Theorem/勾股定理 in ancient China, where gou/勾 and gu/股 mean the shorter and longer legs of the right triangle respectively, and the hypotenuse is named xian/弦 (unlike what the above linked article suggests, this naming has more to do with the ancient Chinese percussion instrument qing/磬, which is shaped similar to a right triangle). Gougu Theorem was recorded in the ancient Chinese mathematical work Zhoubi Suanjing/《周髀算经》, and the name Gougu Theorem is still used in China today.

Diagram of the proof for Gougu Theorem in Zhoubi Suanjing. The sentence on the left translates to "gou (shorter leg) squared and gu (longer leg) squared makes up xian (hypotenuse) squared", which is basically the equation a² + b² = c². Note that the character for "squared" here (mi/幂) means "power" today.

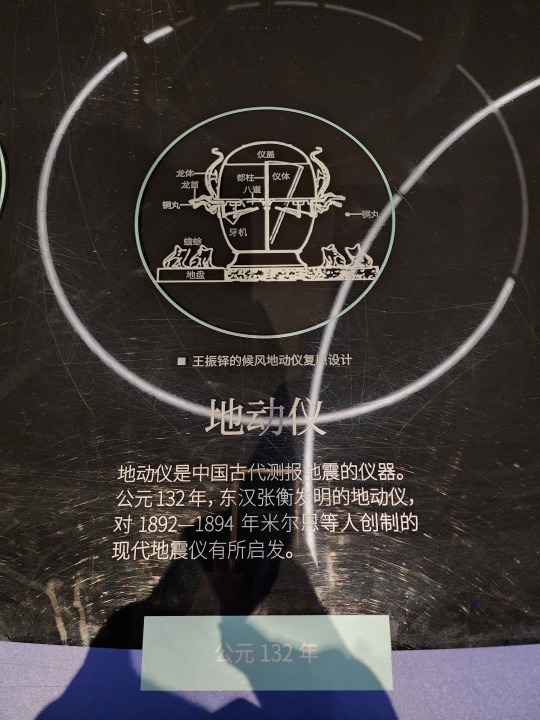

This is a diagram of Zhang Heng’s seismoscope, called houfeng didong yi/候风地动仪 (lit. “instrument that measures the winds and the movements of the earth”). It was invented during Eastern Han dynasty, but no artifact of houfeng didong yi has been discovered yet, this is presumably due to constant wars at the end of Eastern Han dynasty. All models and diagrams that exist right now are what historians and seismologists think it should look like based on descriptions from Eastern Han dynasty. This diagram is based on the most popular model by Wang Zhenduo that has an inverted column at the center, but this model has been widely criticized for its ability to actually detect earthquakes. A newer model that came out in 2005 with a swinging column pendulum in the center has shown the ability to detect earthquakes, but has yet to demonstrate ability to reliably detect the direction where the waves originate, and is also inconsistent with the descriptions recorded in ancient texts. What houfeng didong yi really looks like and how it really works remains a mystery.

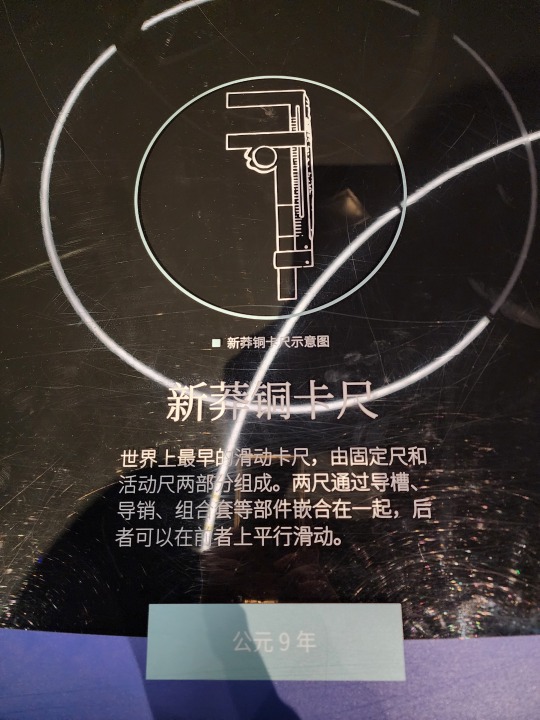

Xin dynasty bronze calipers, the earliest sliding caliper found as of now (not the earliest caliper btw). This diagram is the line drawing of the actual artifact (right).

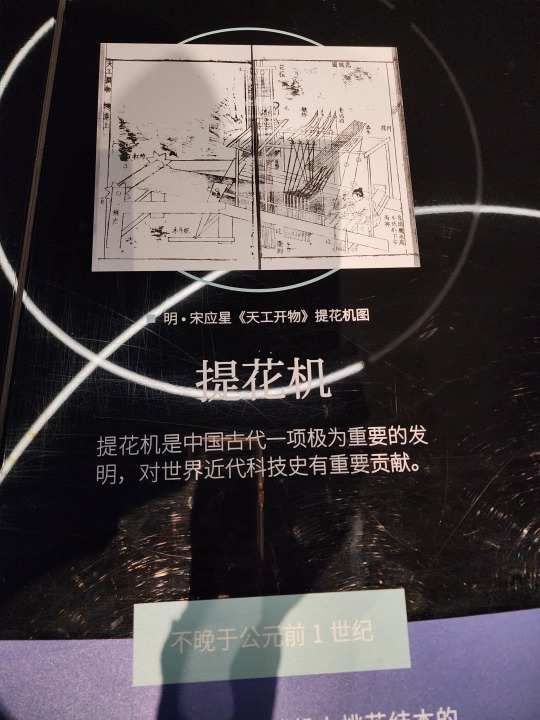

Ancient Chinese "Jacquard" loom (called 提花机 or simply 花机 in Chinese, lit. "raise pattern machine"), which first appeared no later than 1st century BC. The illustration here is from the Ming-era (1368 - 1644) encyclopedia Tiangong Kaiwu/《天工开物》. Basically it's a giant loom operated by two people, the person below is the weaver, and the person sitting atop is the one who controls which warp threads should be lifted at what time (all already determined at the designing stage before any weaving begins), which creates patterns woven into the fabric. Here is a video that briefly shows how this type of loom works (start from around 1:00). For Hanfu lovers, this is how zhuanghua/妆花 fabric used to be woven, and how traditional silk fabrics like yunjin/云锦 continue to be woven. Because it is so labor intensive, real jacquard silk brocade woven this way are extremely expensive, so the vast majority of zhuanghua hanfu on the market are made from machine woven synthetic materials.

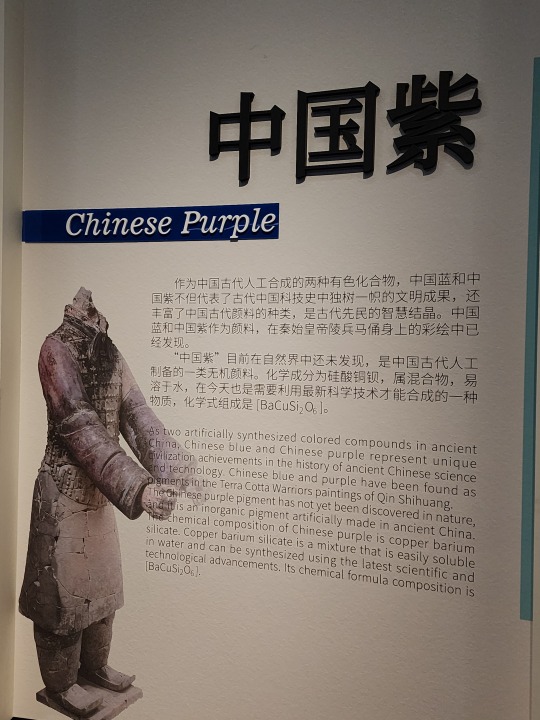

Chinese purple is a synthetic pigment with the chemical formula BaCuSi2O6. There's also a Chinese blue pigment. If anyone is interested in the chemistry of these two compounds, here's a paper on the topic. (link goes to pdf)

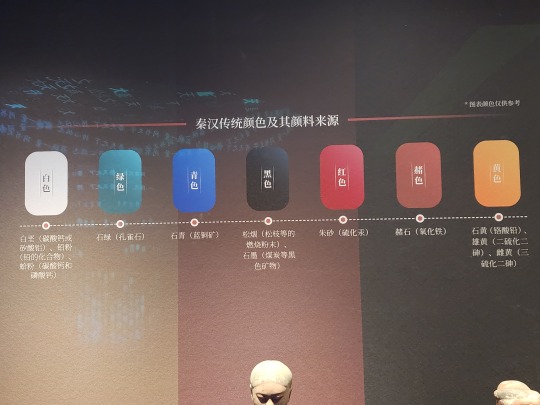

A list of common colors used in Qin and Han dynasties and the pigments involved. White pigment comes from chalk, lead compounds, and powdered sea shells; green pigment comes from malachite mineral; blue pigment usually comes from azurite mineral; black comes from pine soot and graphite; red comes from cinnabar; ochre comes from hematite; and yellow comes from realgar and orpiment minerals.

Also here are names of different colors and shades during Han dynasty. It's worth noting that qing/青 can mean green (ex: 青草, "green grass"), blue (ex: 青天, "blue sky"), any shade between green and blue, or even black (ex: 青丝, "black hair") in ancient Chinese depending on the context. Today 青 can mean green, blue, and everything in between.

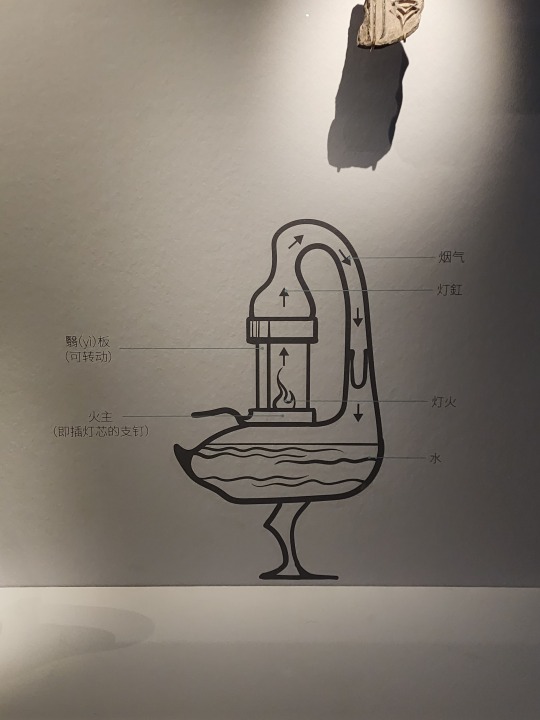

Western Han-era bronze lamp shaped like a goose holding a fish in its beak. This lamp is interesting as the whole thing is hollow, so the smoke from the fire in the lamp (the fish shaped part) will go up into the neck of the goose, then go down into the body of the goose where there's water to catch the smoke, this way the smoke will not be released to the surrounding environment. There are also other lamps from around the same time designed like this, for example the famous gilt bronze lamp that's shaped like a kneeling person holding a lamp.

Part of a Qin-era (?) clay drainage pipe system:

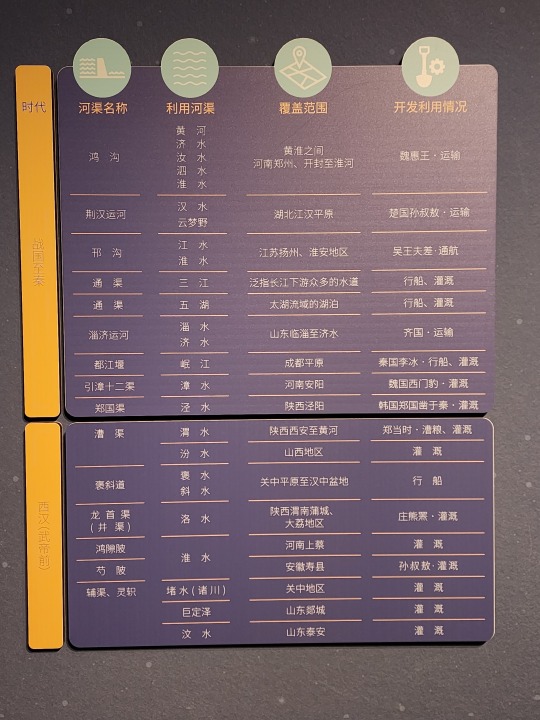

A list of canals that was dug during Warring States period, Qin dynasty, and pre-Emperor Wu of Han Han dynasty (475 - 141 BC). Their purposes vary from transportation to irrigation. The name of the first canal on the list, Hong Gou/鸿沟, has already become a word in Chinese language, a metaphor for a clear separation that cannot be crossed (ex: 不可逾越的鸿沟, meaning "a gulf that cannot be crossed").

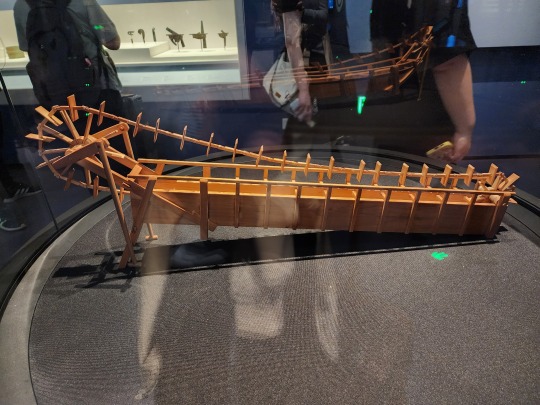

Han-era wooden boat. This boat is special in that its construction has clear inspirations from the ancient Romans, another indication of the amount of information exchange that took place along the Silk Road:

A model that shows how the Great Wall was constructed in Qin dynasty. Laborers would use bamboo to construct a scaffold (bamboo scaffolding is still used in construction today btw, though it's being gradually phased out) so people and materials (stone bricks and dirt) can get up onto the wall. Then the dirt in the middle of the wall would be compressed into rammed earth, called hangtu/夯土. A layer of stone bricks may be added to the outside of the hangtu wall to protect it from the elements. This was also the method of construction for many city walls in ancient China.

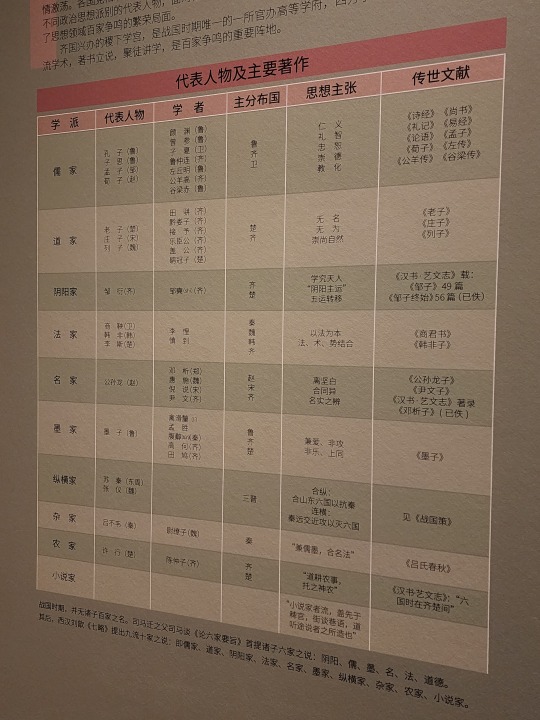

A list of the schools of thought that existed during Warring States period, their most influential figures, their scholars, and their most famous works. These include Confucianism (called Ru Jia/儒家 in Chinese; usually the suffix "家" at the end denotes a school of thought, not a religion; the suffix "教" is that one that denotes a religion), Daoism/道家, Legalism (Fa Jia/法家), Mohism/墨家, etc.

The "Five Classics" (五经) in the "Four Books and Five Classics" (四书五经) associated with the Confucian tradition, they are Shijing/《诗经》 (Classic of Poetry), Yijing/《易经》 (also known as I Ching), Shangshu/《尚书》 (Classic of History), Liji/《礼记》 (Book of Rites), and Chunqiu/《春秋》 (Spring and Autumn Annals). The "Four Books" (四书) are Daxue/《大学》 (Great Learning), Zhongyong/《中庸》 (Doctrine of the Mean), Lunyu/《论语》 (Analects), and Mengzi/《孟子》 (known as Mencius).

And finally the souvenir shop! Here's a Chinese chess (xiangqi/象棋) set where the pieces are fashioned like Western chess, in that they actually look like the things they are supposed to represent, compared to traditional Chinese chess pieces where each one is just a round wooden piece with the Chinese character for the piece on top:

A blind box set of small figurines that are supposed to mimic Shang and Zhou era animal-shaped bronze vessels. Fun fact, in Shang dynasty people revered owls, and there was a female general named Fu Hao/妇好 who was buried with an owl-shaped bronze vessel, so that's why this set has three different owls (top left, top right, and middle). I got one of these owls (I love birds so yay!)

And that concludes the museums I visited while in Xi'an!

#2024 china#xi'an#china#shaanxi history museum qin and han dynasties branch#chinese history#chinese culture#chinese language#qin dynasty#han dynasty#warring states period#chinese philosophy#ancient technology#math history#history#culture#language

90 notes

·

View notes

Text

Selections from Hongmei Sun’s “Transforming Monkey”

Here it is! My compilation of quotes that I particularly liked from Sun’s excellent overview of the figure of the Monkey King. I hope you all enjoy them and find that they give you a richer understanding of an amazing text and its amazing monkey

---

Sun, Hongmei. Transforming Monkey: Adaptation & Representation of a Chinese Epic. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2018.

3: “Sun Wukong, known as the Monkey King in English, is the protagonist of the Ming dynasty novel Journey to the West (Xiyou ji). He is famous for his ability to shape-shift and ride the clouds, his size-changing magic rod, and his love of playing tricks. The longevity of his story reflects his popularity in Chinese culture: the ‘Journey to the West’ narrative is among the most malleable and long-lasting in Chinese literary history. With the repeated adaptations of the narrative over the centuries, the image of the protean monkey character has evolved into the Monkey King we know today.

Journey to the West is a one-hundred-chapter novel published in the sixteenth century during the late-Ming period. It is considered one of the four masterworks of the Ming novel, along with Water Margin (Shuihu zhuan), Romance of the Three Kingdoms (Sanguo yanyi), and The Plum in the Golden Vase (Jinping mei). Loosely based on the historical journey of the famous monk Xuanzang (602-664), who traveled in the Tang dynasty from China to India in search of Buddhist scriptures, the story experienced a series of adaptations over hundreds of years before it was developed into the full-length novel, which recounts a mythological pilgrimage of the monk Tripitaka (the fictional Xuanzang), accompanied by three disciples and protectors he converts along the way: Sun Wukong (aka the Monkey King, or Monkey), Zhu Bajie (aka Zhu Wuneng, Pigsy, or Pig), and Sha Wujing (aka Sha Seng, Sha Heshang, Friar Sand, or Sandy). These disciples, as well as a dragon prince who transforms into a white horse as Tripitaka’s steed, are demons or animal spirits who have sinned…”

4: “Along the way, the group encounters and overcomes eighty-one tests, most of which involve demons and spirits who want to capture Tripitaka and eat his flesh in order to gain immortality.

The history of Journey to the West represents a process of continuous adaptations of Xuanzang’s story. The historical trip becomes a mythological journey in a world full of demons, spirits, Taoist gods, and Buddhist celestials. At some point—the actual origin and provenance remain unclear—the monkey follower of Xuanxang was added to a retelling of the story. Once included, the monkey figure grew in popularity until he replaced the monk as the main character and protagonist. It is owing to the long process of adaptation that today the Monkey King remains popular globally.”

5: “Literary analyses of the text have taken diverse and heterogeneous approaches but have predominantly focused on the religious and allegorical meanings of the tales. Little has been written about the Monkey King image in contemporary settings from the approach of adaptation, despite the obvious importance of this approach for Journey to the West, which is the product of repeated adaptations and maintains its influence in popular culture through ongoing adaptation today. Journey to the West is an accretive text, shaped by many hands at many times, and through interactions with many audiences.”

6: “…for lack of new data and more convincing interpretation, the Shidetang edition printed in 1592 is generally considered the ‘original.’ Although it is now generally accepted that Wu Cheng’en (ca. 1500-ca. 1582) is the author of the Shidetang edition of Journey to the West, this position is supported only by the lack of better candidates and more convincing evidence. Furthermore, the origin of the Monkey King character remains unclear.”

-“Through hundreds of years the Monkey King figure has shown amazing adaptability. His story appears in various forms in all media, crossing borders of culture and time, and his image has been frequently used in racial and political representations with social and political impact. Sun Wukong’s changes throughout modern history, intertwined with the construction and representation of Chinese identity, require a thorough examination.”

9: “Tracing further back from “Journey to the West,” two major sources for the narrative have been found: the historical journey of Xuanzang and the mythical figure of the Monkey King. Although the historical event clearly refers to the journey to India that the monk Xuanzang undertook in the seventh century, and the historical figure Xuanzang is accepted almost unanimously by scholars as the source of the character Tripitaka in the novel, the source of the Monkey King is unclear. Multiple figures may have influenced the image of the Monkey King, including Hanuman in the Indian tradition and monkey lore in the Chinese tradition. Each of these two major narrative lines revolves around one protagonist, who together become the two major characters in Journey to the West. Although the Monkey King figure was adopted into the narrative of the journey to India as only a helper of the monk, in later versions of the story the monkey becomes the protagonist, as becomes evident in Journey to the West, and more obviously in contemporary adaptations in China, where the Monkey King becomes the central figure with whom the audience identifies, and Tripitaka is portrayed with more negative features.”

11: “If one were to narrow the rich meaning of the Monkey King image down to a trope, it would like in the tension between the monkey, the human, and the god that coexists in the Monkey King. Because the tension exists in something as important and personal as the body itself, the image of Sun Wukong is therefore being used in a varied situations representing the struggle in identity. What the Monkey King can contribute to the issue of Asian American identity is the metaphor of transformation, the freedom one can attain in one’s body, and by extension in aspects of one’s social life.”

13: “Because of the fundamental multivalence in this figure, various political and ethnic groups use him as a representative to tell their own stories…Historically speaking, ‘Journey to the West’ is a product of adaptation. When the image of the Monkey King is added to the narrative and gradually takes the shape of Sun Wukong in Journey to the West, the influence of antecedents and the interlacing traditions of popular and elite culture together shape what we know as the protagonist of the sixteenth-century novel. A major transformation takes place in the mid-twentieth century during the reign of Mao Zedong, when the trickster monkey is collectively recast as a revolutionary hero. This heroic image remains the mainstream view until a new change is initiated by a Stephen Chow film, A Chinese Odyssey (1995), after which the image of Monkey takes a postsocialist turn. While the new transformation of the Monkey King as a hero is ongoing in China, in American popular media the Monkey image is adapted in a different manner, representing a mythical and antiprogressive oriental. Asian American adaptations, on the other hand, use the image of the Monkey King to illustrate the struggles of ethnic minorities in the United States, racial stereotypes, and ethnic identity. Monkey continues to shape-shift in new places and times, and each new Monkey collectively enriches our understanding of his image.”

15: “At the beginning of the hundred-chapter novel Journey to the West, a monkey is born from a primeval stone egg. This uncommon birth makes it impossible to place him into a distinct taxonomic category. ‘Born of the essences of Heaven and Earth,’ he is nonetheless still one of ‘the creatures from the world below.’ While the Monkey King belongs to both heaven and earth, his legendary birthplace is not easily locatable in either. According to the Buddhist cosmology introduced to the reader at the beginning of the first chapter, the Flower-Fruit Mountain (Huaguo Shan) appears to be located on the East Purvavideha Continent (Dong Shengshen Zhou), one of the four continents of the world. However, its geographic location relative to heaven and earth, or to the other continents that the monkey traverses in his journey, is never accounted for. To some extent the ambiguous birth and birthplace of the monkey contribute to his multivalent character.

At home on the Flower-Fruit MMountain, the monkey soon declares himself the Monkey King after demonstrating his prowess by crossing a waterfall and discovering a new territory, the Water-Curtain Cave, on behalf of the entire monkey kingdom. It is the first breakthrough in his life and is accomplished through crossing boundaries. Soon thereafter, and having become dissatisfied with a mortality that, by necessity, would subject him to the border between life and death, the self-proclaimed king sets off on a raft in search of a teacher who might guide him toward immortality. This journey brings him from the East Purvavideha Continent to the West Aparagodaniya Continent (Xi Niuhe Zhou), where he finds a master in the Patriarch Subhuti (Xuputi Zushi) on Lingtai Mountain.”

16: “Of no small significance, the master, one of the ten disciples of the Buddha, is described here as one who finds harmony among Buddhism, Taoism, and Confucianism. By means of the physical and spiritual journey from east to west, the monkey has acquired a name, Sun Wukong (Awaking to Emptiness), together with esoteric techniques enabling him to wield magical powers.

After returning to the Flower-Fruit Mountain, Sun Wukong successfully defends the subjects of his monkey kingdom by defeating a demon foe and thereby creating a name for himself among the demon kings. In addition, he befriends a number of immortal beings who occupy neighboring lands, one of whom in the Bull Demon King (Niumo Wang), who later becomes an antagonist of the pilgrims. By becoming brothers with these demons on earth, Sun Wukong posits himself as one of them. He tests his power in the water realms and convinces the dragon kings there to present him with their treasured magic iron, which becomes hi famous iron rod. He also creatures turmoil in hell when he deletes the names of his monkey tribe from the Register of Life and Death, hence attaining immortality, although unofficially. The sphere in which he can be active is thus enlarged to include the earth, the sea, and the underworld.

Heaven, having learned of the monkey’s mischievous behavior, appoints him as Supervisor of the Imperial Stables (Bimawen), in an effort to co-opt him. His territory is thus further enlarged to include heaven. This is an important step in his life since he is now recognized as a deity within the heavenly hierarchical system rather than an outsider demon. When Sun Wukong recognizes his low position in the celestial hierarchy, he returns to his mountain and lays claim to the title ‘Great Sage, Equal to Heaven,’ essentially declaring himself the strongest demon in the world in possession of an outlaw power on par with heaven’s. Dissatisfied with marginalization within one system, he simply chooses to create a parallel system and names himself its head. And when heaven is unable to take him by force, it once again must reabsorb the monkey peacefully by reaccepting him into the heavenly fold. Despite being officially recognized as the Great Sage, the Monkey King still constantly breaks rules in heaven, and ultimately creates havoc when he learns he is not invited to the Peach Banquet. The disgruntled monkey breaks off yet again from heaven, this time demanding that he replace the Jade Emperor…”

17 + 18 (for list): “…himself. Significantly, the domains that Sun Wukong has so far tested and conquered include the earth, water, hell, and the Taoist heaven. Being active in all levels of the mythic cosmos enables him to enjoy immense growth in his realm—but more importantly, he becomes effectively limitless.”

Sun Wukong’s rebellion comes to an end when he meets the Buddha. He accepts the wager the Buddha has proposed, which is to jump out from the Buddha’s palm. Failing to do so, since the Buddha’s palm can grow as fast as Wukong can jump, he is subsequently imprisoned under the Five Phases Mountain for five hundred years, which functions as a turning point in Monkey’s life and an intermission in the narrative. What Monkey goes through during this period is completely omitted by the narrative, which simply switches to the story of Tripitaka and the beginning of the journey. When the Monkey King reappears in the story, his life starts anew on a very different track.

The monkey is in due course released by the traveling monk Tripitaka, who becomes his master and gives him the name Pilgrim (Xingzhe). At the beginning the master is shocked by Wukong’s demonic behavior and worried that the monkey might be out of control. The Bodhisattva Guanyin responds by setting a fillet on the monkey’s head. The tightening of this band—in response to Tripitaka’s recitation of the Tight-Fillet Spell (Jingu Zhou)—enables Tripitaka to control the monkey’s actions. Henceforth Sun Wukong serves as Tripitaka’s protector and as leader of the other disciples. He becomes the monk’s most reliable defense against demons and monsters on their way to the West. In the following eighty-seven chapters, which are primarily a long series of captures and releases of the pilgrims by monsters, demons, animal spirits, and gods in disguise, Sun Wukong either defeats the adversaries himself or finds a natural or sociopolitical conqueror of the enemy to ensure victory.

In Journey to the West, Monkey’s life can be summarized as composed of two parts, with the Five Phases Mountain as the watershed. Before his subjugation by the Buddha under the Five Phases Mountain, his life can also be divided into several phases, each phase with a different name and identity:

I: Before Subjugation:

a. The nameless stone monkey

b. The Handsome Monkey King (Mei Houwang)

c. Sun Wukong (name given by Subhuti)

d. The Supervisor of the Imperial Stables (Bimawen)

e. The Great Sage, Equal to Heaven (Qitian Dasheng)

Intermission: 500 years under the Five Phases Mountain

II: After Subjugation

Pilgrim (Xingzhe)

18: “The five phases of the monkey’s life before his subjugation by the Buddha demonstrate the innate drive of the monkey to test every limit that defines his sphere. With each step the monkey takes in his life, there is a transformation, a breakthrough, and his magic skills allow him to transgress limits. Step by step he broadens his sphere, challenging every authority, until he is facing the greatest cosmic power (who is, interestingly, the foreign Buddha from the West, invited by the indigenous god, the Jade Emperor). It is the spirit that challenges all limits that identifies him as a demon, one of those who dwell outside of the space of heavenly order. Since hierarchical control is about keeping boundaries and maintaining order, this kind of nonstop challenge cannot be accepted. Monkey therefore has to be either considered as a challenge from the outside (a demon) or changed and co-opted within the system.”

--“The five hundred years serve as a narrative gutter, before which Monkey strives to surpass all boundaries—the patriarch of all beings—while after it the monkey becomes a servant, a pilgrim following the orders of a monk, confined by the magic headband. Before the gutter, he was a demon himself; after the gutter, he becomes a demon-subjugator and a demon killer. When encountering and fighting antagonist demons, the pilgrim monkey continually boasts to them about his glorious past as a demon monkey but the kills or subjugates them by himself or with celestial help. In this sense, the journey of the pilgrims is at the same time a story of demon-conquering and an account of the subjugation of the monkey himself.”

19: “He is simultaneously the one and the other, dual contradictions within one body.

But this is not only a journey from China to India. The Monkey King’s journey, far from unidirectional, is also full of upward and downward movement—he bounces between the heavenly gods and the demons and monsters on earth both before and after his submission. The nature of these trips does, however, change after his imprisonment. In the early phases of his life, the journeys up and down are carried out via his free will, whereas the later ups and downs as a pilgrim are mostly arranged by Guanyin and the other gods, as part of the trials of the journey. Just as his somersault never enables him to jump out of the hand of Buddha, his somersaulting up and down during the pilgrimage never gets him out of the determined trajectory of his life. He is only fulfilling his task, the mission of a pilgrim who works as a mediator.

The character of the Monkey King is fundamentally self-contradictory. In the earlier stage of his life, his is a self-important heroic rebel, but later he transforms into a loyal disciple of the monk master and a pious believer in Buddhist thought. Monkey does go through some transitional periods during the journey, including a few incidents in which he is in disagreement with, yet has to obey, Tripitaka, but later in the journey the narrative demonstrates that his understanding of the Heart Sutra often even surpasses that of Tripitaka.”

20: “Reflected by his names and titles, Sun Wukong juggles his multiple identities, some of which are sharply opposed to each other.”

21: “Rather than mediating between two opposite states, the Monkey King denies and deletes dualism and brings multiple and otherwise incompatible possibilities together.”

24: “As a narrative rejecting dichotomy, Journey to the West clearly rejects a simple division of the story into shouxin (controlling the mind, retrieving of mind) and fangxin (letting the mind go, exile of the mind). Not only is the ‘mind monkey’ always fond of his mischievous ways when he remains a follower of Tripitaka, in the two episodes of the ‘exile’ of the ‘mind monkey,’ he is never totally let loose either. In both cases he asks Tripitaka or Bodhisattva to take his head fillet off, but neither of them is able to fulfill his request. Ironically, although Tripitaka ‘exiles’ the monkey from the pilgrim group, his power over the Tightening Fillet remains. Monkey, on the other hand, is also never totally happy when being released. In the case of the first release, Bajie (Pigsy) has to resort to a stratagem to persuade the monkey to return: he lies to the monkey that the monster who had beaten the pilgrims does not take seriously of the name of Sun Wukong and his deeds in heaven five hundred years ago. It is in defense of his reputation as the ‘number one monster’ that the monkey leaves his Flower-Fruit Mountain and returns to rejoin the band of pilgrims.

In the case of the second ‘exile,’ the episode of the ‘double-mind monkey’ (erxin yuan), a fake Wukong commits a series of monstrous crimes in his name. While one ‘mind monkey’ is staking with the Bodhisattva, the other ‘mind monkey’ goes to strike the master Tripitaka unconscious, takes his travel documents, returns to the Flower-Fruit Mountain, and sets up another pilgrim band, ready for his own journey to the West. The resemblance of the two ‘mind monkeys’ deceives everyone except the Buddha, who sees through the fake Wukong and recognizes him as a six-eared macaque (liuer mihou). The use of a double of Wukong enables the narrative to literally grant the monkey the facility to be self-contradictory, with one Monkey being a pious follower of Tripitaka, and the other a monster who is even capable of beating his master. At the culmination of this episode, Sun Wukong uses his rod to kill the six-eared macaque,…”

25: “…despite the fact that the macaque had already been captured by Buddha’s golden almsbowl—a constraining weapon—and submitted to Buddha’s control, which seems out of character for the ‘good’ Monkey. One feasible explanation would be that it is an action of eliminating the monster in him, indicating that he is getting closer to achieving Buddhahood at this point in the journey. However, this explanation does not negate another one: that he kills the six-eared macaque because the latter has copied him too closely, the best demon among the ones that Monkey has conquered. By killing his rival who resembles himself, he plays the norm of self-contradiction to an extreme.”

26: “At that very moment the actual smallness of the monkey’s bloated self is demonstrated in the shadow of the Buddha’s fingers, the overblown ‘mind monkey’ is reduced to finite proportions, and his rehabilitative imprisonment under Five Phases Mountain begins. The lesson demonstrates to him that, however far the ‘cloud-somersault’ can reach, it would also represent his own unbreakable boundary. The Buddha’s fingers serve as an index, revealing to the monkey that what beats him is how own self. Later this indexing role of Buddha’s hand is taken over by the Five Phases Mountain, and after that the headband. Whenever Tripitaka recites the spell, Monkey is reminded of his own limits and the impossibility of breaking them, even with his rod.

In the case of the six-eared macaque, one can reach an opposite explanation as to why Wukong chooses to kill him: to free himself. Just as in the submission of Wukong, Buddha beats the six-eared macaque at his forte. Although the fake Wukong is strong in taking forms of others and had succeeded in confusing everyone else, the Buddha is able to exactly identify this monkey’s original form: someone belonging to none of the ten categories in the universe, neither the five immortals (wu xian) nor the five creatures (wu chong). There are four kinds of monkeys who ‘are not classified in the ten species, nor are the contained in the names between Heaven and Earth,’ among which was the first, ‘the intelligent stone monkey (lingming shihou), who knows transformations, recognizes the seasons, discerns the advantages of earth, and is able to alter the course of planets and stars,’ and the fourth, ‘the six-eared macaque, who has a sensitive ear, discernment of fundamental principles, knowledge of past and future, and comprehension of all things.’ This recognition announces the six-eared macaque’s failure as one who has been trying to use his disguise to erase the boundary of his self while taking up the identity of Wukong. It also announces once again the failure of Wukong, who although not belonging to any of the ten species between heaven and earth, still falls into one of the in-between types that the Buddha names: the intelligent stone monkey, indeed a peer of the six-eared macaque. Therefore by killing the six-eared macaque, Wukong not only kills a monster who has tried to cross proper borders, but he also kills a self whose boundary has just been pinned down. This action of self-annihilation is in this sense an effort in defiance of any classification.”

27: “Readers may often find it hard to tell whether the monkey is a monster or a pilgrim during any one incident: just like the rod and headband, the monster and pilgrim are indispensable sides of the character of Sun Wukong.”

-“The narrative of Journey to the West itself also has a multivalent nature. Containing and allowing for contradictions is a central message of the book. Theses and rhetoric of Buddhism, Taoism, and Confucianism all appear in every part of the work. For a story of Buddhist monks’ pilgrimage for Buddhist sutras, it also bears apparent characteristics of Taoist dual cultivation. While gods of Buddhist and Taoist traditions happily coexist, a Confucian emphasis on filial piety and loyalty is also prevalent. Owing to the coexistence of heterogenous factors, the text gives space for various interpretations of the metaphorical meaning of the book…In the narrative there are multiple parameters for the classification and ranking of cosmic beings, among them two basic categories—the earthly demons and the heavenly gods. At first glance the two are a pair of opposing powers, one always contradicting the other. However, a closer view of the relationship between the two reveals that the boundaries between the categories and kinds in the cosmic hierarchy are not firmly fixed. There are always possibilities of crossing the boundaries; the coexistence of all these distinctive beings is already an act of the abnegation of boundaries.”

28: “Historian of Chinese religion Robert Campany visualizes the positions of these demons in the hierarchy, within which boundaries can be crossed upward or downward by means of transformation (hua, the phenomenon of demons assuming bodies and forms not their own), reincarnation, cultivation, conversion, or subjugation. Hierarchical distinctions are thus relative, and typological divisions appear to be mere illusion, with the pilgrim and demons both functioning as antagonists and complementing one another. Although demons and the pilgrims are similar in that both strive for cultivation of self, ‘demons have not yet realized the necessity of submitting the self to a larger Self that is the entire cosmic order.’ This insight points to another duality that is undercut by the narrative.

This allegorical explanation—that the pilgrims, by battling against the demons, come to realize the truth of emptiness, while Wukong, as indicated by his name, has always been aware of it—however, is too neat, as the purpose of the journey allows to multiple interpretations. While the pilgrims are moving toward a destination, ironic tension is apparent between the exuberant ease with which Monkey travels between different sphere and Tripitaka’s extreme difficulty in moving forward on his journey on earth.”

29: Andrew Plaks argues that “the characteristic Chinese solution to the problem of duality ‘consists in the conception of a universe with neither beginning nor end, neither eschatological nor teleological purpose, within which all of the conceivable opposites of sensory and intellectual experience are contained, such that the poles of duality emerge as complementary within the intelligibility of the whole.’ This argument about the Chinese concept of complementary duality provides an interesting explanation for the coexistence of contradictions in the narrative. It may also count as one of the cultural situation ‘generative of ambivalence and contradiction’ that folklorist Laura Makarius discusses. The concept of complementary duality in Chinese culture certainly helps explain the fundamental ambiguity regarding the teachings in the journey, the most famous being the merging boundary between god and demon.”

-“Transformation is something practiced very commonly by heavenly immortals and demons alike in Journey to the West. Besides crossing the boundary between the deity and demon, it also illustrates that all ‘forms,’ no matter how different they might look, are the same because they are all manifestations, or illusions. Forms are not the true nature of a being, and an important technique for a creature to attain in becoming an immortal through cultivation is the ability to transform itself, as well as the ability to see through forms. The Monkey King is among the most adept at seeing through the false forms of demons and monsters. In short, transformation, and the understanding of transformation, seem to have a crucial connection with a nondualist (or multivalent) understanding of the universe.”

35: “The multistable image of the Monkey King…serves as a hyper-icon. The seemingly simple factors of the image, a monkey in human clothes with a head ring and an iron rod, together encapsulate a whole bundle of meanings, an entire episteme. It can be used as a decoration, and it can also be used to speak to power, knowledge, and representation. It is fascinating that it continues over centuries to appeal to readers/audiences of various social orders and successfully transforms them into creators of new images.”

39: “Shihua [Full title Da Tang Sanzang qujing shihua] is the first fictional account of Xuanzang’s journey in which the monk acquires a monkey attendant who functions as his guide and protector. Following his introduction, the monkey figures enjoyed growing popularity in subsequent fictional retellings of the story, until in the hundred-chapter novel Journey to the West he becomes the protagonist of the story, overshadowing his master…Compared to Xuanzang’s historical journey, Shihua introduces two major changes to the nature of the journey that are carried through later adaptations of the story. In the first, the monk’s individual religious pursuit, a brave act that breaches the law of Tang and puts his own life at risk, is transformed into the performance of a decreed commission from the Tang emperor. Although the imperial decree seems to have given Tripitaka a more celebrated status, his choice to defy the legal order in order to undertake his religious pilgrimage is taken away from the monk. Second, realistic challenges the monk had to face are replaced by obstacles deployed by demons and deities, which Tripitaka relies on the monkey to conquer. These two changes set the stage for a transformation of the story about Tripitaka into a story about the monkey.

Buddhist themes and elements in the story are obvious, but there is no monopoly of Buddhist themes; instead, a variety of traditions and cults are present in the text, with popular tradition being blended into the orthodox religious material. In this sense, Shihua already begins to show what is masterfully realized in the hundred-chapter version Journey to the West: the encyclopedic coexistence of different and conflicting cultures and traditions. According to Shihua’s account, the monk is on his way to acquire scriptures because he has received an imperial commission. On his way he meets the monkey figure, Hou Xingzhe (Monkey Acolyte), who becomes his guide and assistant. This story is filled with praises of the religious pilgrimage, paying its respects to Buddha and Buddhist teaching and eulogizing the peaceful places near the Western Heaven. Unlike the later versions, it is clear in the story that the success of the pilgrimage is based on Tripitaka’s deep understanding of Buddhist texts and great strength in his belief. The Tripitaka in later versions will reply on the assistance of Sun Wukong and gods from all parts of the universe to complete his journey.”

40: “There is little evidence to show where the monkey figure originated, but scholars have discussed the possible connections between Hou Xingzhe and the carved monkey figures at the Kaiyuan Temple in Quanzhou Prefecture, Fujian; monkey stories in Buddhist texts; and Hanuman of the Ramayana. Discussion about Hanuman as the influence or origin of Sun Wukong can be traced to Hu Shih’s 1923 article ‘Textual Criticism of Journey to the West’ (Xiyou ji kaozheng), but at about the same time Lu Xun, in his Brief History of the Chinese Novel (Zhongguo xiaoshuo shilue), disagreed, connecting Sun Wukong with the ape-shaped Chinese mythical figure Wuzhiqi. The two scholars who built the foundation of modern Chinese literary study thus began a long-running argument in Journey to the West scholarship about the origination of Sun Wukong. Even today, the problem of the origin of the Chinese Monkey King is unresolved. For, in addition to these two sources, there are other possible origins or influences, such as the influence of Buddhist texts; the figure of Shi Pantuo, a disciple of Xuanzang at the beginning stages of his trip; the Monk Wukong of the Tang; tales about a white ape who abducts women; and the Fujian cult of Qitian Dasheng or Tongtian Dasheng….Regarding the origination of Hou Xingzhe, Zhang Chengjian’s findings generally support the notion of a greater influence from India than from indigenous myths, and in particular the influence of Hanuman or the ape-shaped guardian general in the Tantric tradition.”

41: However, “scholars who support this view have not been able to provide a convincing theory about the paths of transmission of the Hanuman story. It would seem that the Ramayana may have been transmitted to and spread in China via the Silk Road, the marine Silk Road, or the path via Schuan and Yunnan; however, these paths do not correspond with the appearance of Hou Zingzhe and the transmission of Hanuman to China in either time or place…a foruth path for the transmission of Hanuman could be the Musk Road via Tibet, , as the Tantric tradition reflected in Shihua and the spread of Tantric Buddhism at the time from India through Tibet to China demonstrates a connection between Hanuman and Hou Zingzhe. It is worth noting here, though, that the necessary link between the transmission of Tantric Buddhism and the story of Hanuman is yet to be found. Nonetheless, the image of Hou Xingzhe in Shihua reminds us more of Hanuman and the images of the monkey protector figures found in mural paintings in Dunhuang and the stone relief in Kaiyuan Temple—these serious and godlike images bear very little resemblance to the trickster that the monkey would become in later version.

The role that Hou Xingzhe plays is Tripitaka’s guide through the journey. Although Xingzhe calls Tripitaka ‘my master’ (wo shi), he is the one who gives advice, and Tripitaka always follows it.”

44: “…although Hou Xingzhe appears as a clearly synthesized figure in Shihua, bearing influences from both Indian and Chinese cultures, he is mostly an honorable and capable godlike figure. Negative features have yet to be developed in this character.”

-The six-part, twenty-four-act Zaju Xiyou ji is attributed to the fourteenth-century playwright Yang Jingxian, who lived during the late Yuan and early Ming periods. In the few hundred years between Shihua and Zaju, the story of ‘Journey to the West’ is not only more expanded, containing many of the stories that can be found later in Journey to the West, but the monkey figure in Zaju has grown into a character strikingly different from Hou Xingzhe. If Hou Xingzhe in Shihua is depicted as an advisor for Tripitaka, as respectable albeit mysterious deity, and a brave fighter, the monkey in Zaju is pictured as a rowdy clown, an untamed demon and ill-qualified Buddhist disciple.

The monkey’s name in Zaju now is almost the same as in the sixteenth-century fiction Journey to the West. He refers to himself as ‘Tongtian Dasheng’ (Great Sage Reaching Heaven), only one word’s difference from ‘Qitian Dasheng,’ the title Sun Wukong receives from the Taoist heaven in the sixteenth-century book. In some versions of the Monkey King story, including the Zaju, Qitian Dasheng and Tongtian Dasheng are brothers…”

45: “Although Tongtian Dasheng is the monkey’s title, in the drama everyone calls him ‘the monkey’ (husun), including Guanyin, even though she is the person who gave him the names Sun Wukong and Sun Xingzhe (Acolyte). When Guanyin presents Sun Xingzhe to Tripitaka as his disciple, she gives the monkey an iron fillet, a cassock, and a knife….Even with the headband’s control, Tongtian Dasheng’s behavior and language indicate that his mind remains that of an irreverent demon.

As in the zaju theater tradition, Sun Xingzhe introduces himself to the audience with a poem at his first appearance. Vaunting his celestial birth, his power, and the troubles he could create, in colloquial expression rather than elegant traditional terms as others’ opening poems, the monkey’s poem describes himself as a celebrated ape demon, referring to himself as the King of a Hundred Thousand Demons. In the following statement he introduces himself and his four siblings as his demon family: His elder brother Quitian Dasheng, a younger brother Shuashua Sanlang, and two sisters, Lishan Laomu and Wu Zhiqi Shengmu. This genealogy of the monkey shows that Sun Xingzhe in Zaju is already much more localized, settled into the local religious/cult culture. Unlike the monkey in other versions, this one has a wife, the abducted princess of the Country off the Golden Cauldron. He also proudly reports to the audience his famous misdeeds, which is also the reason that heaven is after him: he has stolen the Jade Emperor’s celestial wine, Laozi’s golden elixir, and the Queen of the West’s (Xichi Wangmu) peaches and fairy clothes. He also makes upfront ribald references about himself in this very first speech. The monkey’s demonic heart is indicated by his intention to eat Tripitaka immediately after Tripitaka rescues him from beneath the mountain. He never shows any seriousness about his business of pilgrimage, and his behavior does not improve during the journey. When the team arrives in India, he uses crude language in a conversation with an old lady about Buddhis ideas of the ‘heart.’”

46: “Sun Xingzhe does not act seriously, nor does he ever speak seriously. The king of demons seems to be good only at stealing and running away.”

-“In scenes 13-16, in the episode of Tripitaka and Sun Xingzhe’s encounter with Zhu Bajie the pig demon, who is converted into Tripitaka’s second disciple, Xingzhe offers to help fight the pig demon, but he is more interested in the Pei girl (old man Pei’s daughter) who has been abducted by Zhu. He only offers to help after old Pei tells him that his daughter is a rare beauty, and his dealings with the pig only revolve around the girl: when he visits the pig’s mountain home, he sees only the Pei girl, so his first action is to take the girl back to Pei. He then waits fo Zhu Bajie in the bridal chamber in the Pei girl’s clothing and flirts with the pig when he arrives…His sustained interest in woman and sex is demonstrated in another encounter with a demon in the Flaming Mountain episode. In this story, he seeks to borrow the Iron Fan from Princess Iron Fan (Tieshan Gongzhu) to put out the fire,…”

47: “…but because he introduces himself using vulgar language, the princess refuses to lend him the fan and instead attacks him. Although eventually—with the help of Guanyin and other gods—the pilgrims pass the Flaming Mountains, the battle with Princess Iron Fain, which later becomes one of the most famous battles of Journey to the West, seems to be caused solely by Sun Xingzhe’s insolence.”

-“The vulgarity of Sun Xingzhe’s language persists throughout the drama. The zaju drama during the Yuan era is distinguished from most other earlier Chinese art forms by its use of informal, vernacual, and nonsensical language. The language that Xingzhe uses is the most vulgar of all, corresponding to his role as the clown. He amuses by making crude jokes and obscene references at most inappropriate occasions throughout the story. For instance, at a crucial moment of his life when Tripitaka meets him for the first time and tries to climb the mountain to have him released, the monkey starts a conversation about love and explains that Triitaka’s motivation to save him is his lust for the monkey’s thin waistline, which resembles that of a desirable beauty. The monkey makes a reference to Agilawood Pavilion (Chenxiang Ting), a place that is known through Li Bo’s poems about the love affair between Emperor Tang Xuanzong and his consort Yang Guifei.”

-“When asked about his heart, Xingzhe comments that he used to have a heart, but he ‘shit it out’ because his ‘asshole’ is too wide.”

48: “From Shihua to Zaju, the monkey is transformed from a god who acts properly to a demon who uses foul language and makes suggestive jokes. In the hundred-chapter Journey to the West, Sun Wukong is turned into a multivalent figure, funny but not crude. The vulgarity of Sun Wukong seems to be peculiar to the Zaju version.”