#Kherson art museum

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Wooden decorative plate depicting a fox and a wolf by Ivan Skitsiuk, 1970s

818 notes

·

View notes

Text

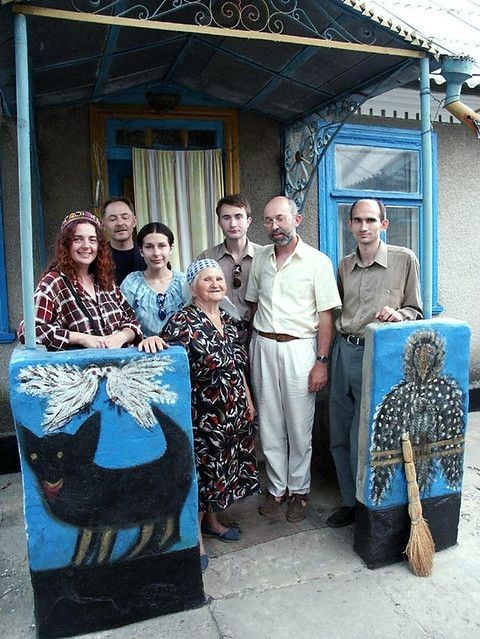

Museum and home of famous Ukrainian painter flooded

The home of famed Ukrainian painter Polina Raiko is under water as a result of the Kakhovka dam destruction.

Polina Raiko was a self-taught painter and an important figure in Ukrainian naïve artistry. Raiko passed away in 2004 at the age of 75 but her home became a museum and a national cultural monument of Ukraine.

#kherson is ukraine#kherson#russia blew up the dam#ecocide#ecological catastrophe#ecology#ukrainian culture#ukraine#ukrainians#museum#museum in ukraine#art in ukraine#ukrainian art#museum under water#russia war criminal#russia war crimes#war in ukraine#stand with ukraine#pray for ukraine#ukraine under attack#war#pray for ukrainians#stop war#pray for ukrainian soldiers#ukrainians on tumblr#kakhovska dam#kakhovska dam destruction#naive art#naive painting#naive artist

482 notes

·

View notes

Text

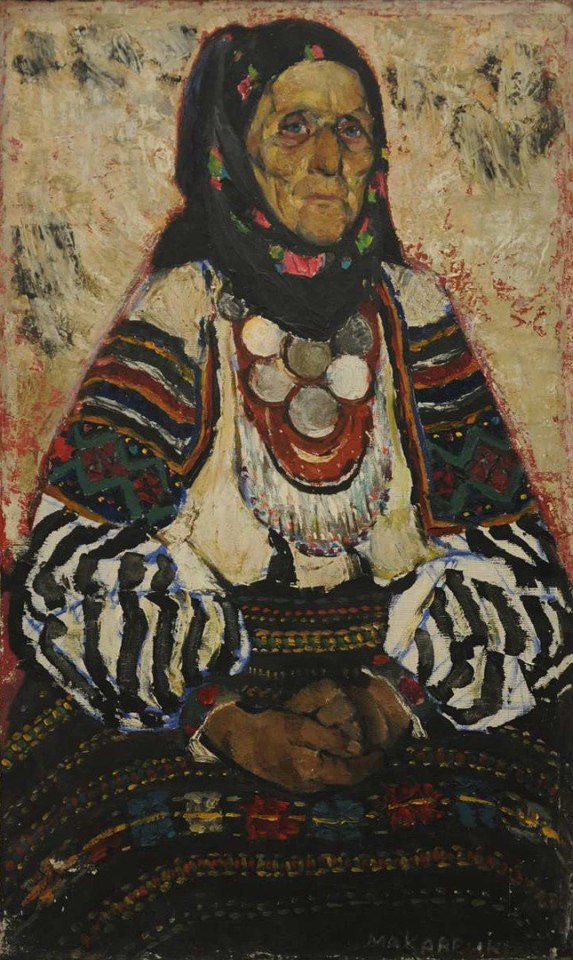

Happy vyshyvanka day!

"Portrait of a girl in vyshyvanka" by Mykhailo Bryanksy/"Peasant woman from Ternopilshchyna" by Marta Makarenko

Both paintings were stolen by russians from Kherson Art Museum.

#ukraine#russia#russia is a terrorist state#fuck russia#genocide#stand with ukraine#support ukraine#genocide of ukrainians#russian war crimes#Ukrainian culture#Ukrainian art#ukrainian clothes#vyshyvanka#art#culture#painting#Kherson

504 notes

·

View notes

Text

Moscow Auction House Sells a $1 Million Painting Stolen from a Ukrainian Museum

In Russia, Ukrainian artist Ivan Aivazovsky’s painting “Moonlit Night” has been put up for auction, according to Ukraine’s former Deputy Attorney General and Prosecutor of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea, Gyunduz Mamedov, who has reported the auction plans.

Russia’s looting and destruction of Ukrainian museums and cultural heritage sites have resulted in significant losses, with nearly 40 museums plundered and almost 700 heritage sites damaged or destroyed since the invasion began in February 2022, causing cultural losses estimated in the hundreds of millions of euros.

The first report that “Moonlit Night” will be the main lot of the auction, which will take place at the Moscow Auction House on 18 February, appeared on the Telegram channel by Russia’s state-funded news agency RIA Novosti, noting that the painting was estimated at 100 million rubles (approximately $1.09 million) before the sale.

‘In 2017, [Interpol], at the request of [Prosecutor’s Office of the Republic of Crimea], put the paintings on the international wanted list. Thus, Russia openly disregards [international law], as according to the 1970 UNESCO Convention, the export of cultural properties and transfer of ownership is prohibited,” Mamedov emphasized on X.

In 2014, during the early stages of Russia’s occupation of Crimea, Aivazovsky’s painting “Moonlit Night” was illegally transferred to the Simferopol Art Museum, along with 52 other artworks.

In 2022, during the Russian invasion of Ukraine, some of his works were destroyed in an airstrike on the Kuindzhi Art Museum in Mariupol, and others were looted by Russian forces from Mariupol and Kherson museums, including “The Storm Subsides,” which was moved to the Central Taurida Museum in Simferopol, Crimea.

#Ivan Aivazovsky#ukraine#russia#russian war crimes#looted art#stolen art#Ivan Aivazovsky 'Moonlit Night'#art#artist#art work#art world#art news#Moscow Auction House Sells a $1 Million Painting Stolen from a Ukrainian Museum

490 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mykhailo Bryansky (1830-1908), Ukrainian artist, Portrait of a girl in an embroidered dress.

Along with this painting, the Russian occupiers stole more than 10,000 works of art from the Kherson Art Museum, and this is only what we know.

This is what so called 'great Russian culture' is built on: genocide, colonization, appropriation and violence.

#art#artist#artists on tumblr#painting#ukraine#ukrainian#ukrainian art#ukrainian culture#ukrainian embroidery#russian war on ukraine#ukrainian tumblr#war#stop the genocide

189 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ivan and Phoebe by Oksana Lutsyshyna

Ivan and Phoebe is a novel about a revolution of consciousness triggered by very different events, both global and personal. This is a book about the choices we make, even if we decide to just go with the flow of life. It is about cruelty, guilt, love, passion – about many things, and most importantly, about Ukraine of the recent past, despite or because of which it has become what it is today.

The story told in Oksana Lutsyshyna’s novel Ivan and Phoebe is set during a critical period – the 1990s. In the three decades that have passed since gaining independence, Ukraine has experienced many socio-political, economic, and cultural changes that have yet to be fully expressed. The Revolution of Dignity in 2014 marked a pivotal moment in the country’s history, as it signaled a shift towards European integration and a strong desire to distance itself from Moscow. Prior to this, Ukrainian culture had remained overshadowed by Russian influence, struggled to compete for an audience and was consequently constrained in exploring vital issues.

77 days of February. Living and dying in Ukraine

"77 Days," is a compelling anthology by contributors to Reporters, a Ukrainian platform for longform journalism. The book, published in English as both an e-book and an audiobook by Scribe Originals.

"77 Days'' offers a tapestry of styles and experiences from over a dozen contributors, making it a complex work to define. It includes narratives about those who stayed put as the Russians advanced, and the horror they encountered, like Zoya Kramchenko’s defiant "Kherson is Ukraine," Vira Kuryko’s somber "Ten Days in Chernihiv," and Inna Adruh’s wry "I Can’t Leave – I’ve Got Twenty Cats." The collection also explores the ordeal of fleeing, as in Kateryna Babkina’s stark "Surviving Teleportation '' and "There Were Four People There. Only the Mother Survived."

It also highlights tales of Ukrainians who created safe havens amidst the turmoil, such as Olga Omelyanchuk’s "Hippo and the Team," about zookeepers safeguarding animals in an occupied private zoo near Kyiv, and one of Paplauskaite’s three pieces, "Les Kurbas Theater Military Hostel," depicting an historic Lviv theater turned shelter for the displaced, including the writer/editor herself.

In the Eye of the Storm. Modernism in Ukraine 1900’s – 1930’s

This book was inspired by the exhibition of the same name that took place in Madrid, at the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, and is currently at the Museum Ludwig, located in Cologne, Germany.

Rather than being a traditional catalogue, the publishers and authors took a more ambitious approach. Rather than merely publishing several texts and works from the exhibition, they choose to showcase the history of the Ukrainian avant-garde in its entirety – from the first avant-garde exhibition in Kyiv to the eventual destruction of works and their relegation to the "special funds" of museums, where they were hidden from public view.

These texts explain Ukrainian context to those who may have just learned about the distinction between Ukrainian and Russian art. Those "similarities" are also a product of colonization. It was achieved not only through the physical elimination of artists or Russification – artists were also often forced to emigrate abroad for political or personal reasons. Under the totalitarian regime, discussing or remembering these artists was forbidden. Archives and cultural property were also destroyed or taken to Russia.

"The Yellow Butterfly" by Oleksandr Shatokhin

"The Yellow Butterfly" is poised to become another prominent Ukrainian book on the themes of war and hope. It has been listed among the top 100 best picture books of 2023, according to the international art platform dPICTUS.

The book was crafted amidst the ongoing invasion. Oleksandr and his family witnessed columns of occupiers, destroyed buildings, and charred civilian cars. Shatokhin describes the book’s creation as a form of therapy, a way to cope with the horrors. "During this time my vision became clearer about what I wanted to create – a silent book about hope, victory, the transition from darkness to light, something symbolic," he explains.

Although "The Yellow Butterfly" is a wordless book, today its message resonates with readers across the globe.

A Crash Course in Molotov Cocktails by Halyna Kruk

A Crash Course in Molotov Cocktails is a bilingual poetry book (Ukrainian and English) about war, written between 2013 and 2022, based on Halyna’s experience as an author, volunteer, wife of a military man and witness to conflict.

The Ukrainian-speaking audience is well-acquainted with Halyna Kruk – a poet, prose author and literature historian. Kruk is increasingly active on the international stage, with her poetry featured in numerous anthologies across various languages, including Italian, French, Swedish, Norwegian, Portuguese, Spanish, Polish, English, German, Lithuanian, Georgian and Vietnamese.

For an English-speaking audience, her poetry unveils a realm of intense and delicate experiences, both in the midst of disaster and in the anticipation of it. The poems are succinct, direct, and highly specific, often depicting real-life events and individuals engaged in combat, mourning, and upholding their right to freedom.

134 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Kherson Art Museum received a gift from the young Kherson artist Tamara Kachalenko (Тамари Качаленко).

These 35 graphic works makes up the series "The Face of War", the bulk of which was created in May 2024.

"Ukrainian art continues to live and develop despite the enemy's attempt to destroy our culture."

#Ukraine#Tamara Kachalenko#Ukrainian artists#art#drawings#The Face of War#wartime art#please let me know if her first name is spelled incorrectly in romanized letters. I never know what to do with the и

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

On a recent trip to Kyiv, I was fortunate enough to join a tour of the city led by Olena Zaretska, the granddaughter of the legendary Ukrainian artist and dissident Alla Horska. Horska was part of a generation of young writers, artists, and intellectuals who challenged the repressive cultural atmosphere of Soviet Ukraine in the 1960s and eventually paid a high price for their defiance. Some were banned from working, others imprisoned, and some – like Horska – murdered by the state.

The Soviet Union’s violent response to artistic defiance wasn’t new in the 1960s. One of Horska’s “crimes” had been to seek out traces of artists and writers purged in the 1930s. She, poet Vasyl Symonenko, and theater director Les Taniuk discovered a mass execution site at Bykivnia, on the outskirts of Kyiv. They knew they had found it when they saw children playing with a skull in the woods.

The soil at Bykivnia contained the remains of avant-garde writers Mykhail Semenko and Mike Yohansen, influential artist Mykhailo Boychuk, and many others. Of the trio who made this gruesome discovery in the early 1960s, only Taniuk would survive. Symonenko was beaten to death in 1963, and Horska was murdered in 1970.

Horska, Taniuk, and their dissident circle didn’t restrict themselves to seeking traces of the dead. In Kyiv in the early 1960s, some leading artists of the 1920s were still alive, holed up in their apartments, all but forgotten.

Zaretska’s tour group stopped outside an unassuming 1950s housing block in central Kyiv – this was the former home of Anatol Petrytskyi, a central figure in the Ukrainian avant-garde of the early 20th century. His work was shown at the Venice Biennale in 1930 and later exhibited in the U.S. Most of his fellow artists, like his close collaborator, theatrical genius Les Kurbas, had been murdered, but Petrytskyi survived. He died in 1964, his post-war career a faint echo of his early success. However, in his final years, he was moved to find himself rediscovered by a new generation once again pushing artistic and political boundaries.

“He spoke with tears in his eyes,” Zaretska told us, standing outside the hip coffee shop that now neighbors Petrytskyi’s old home, “about the hundreds of works of his that the authorities had simply destroyed.”

The conversations in Kyiv apartments of the early 1960s, between those repressed under Joseph Stalin and those soon to be beaten under Leonid Brezhnev, are part of a pattern in Ukrainian cultural life. Each generation salvages the works and memory of the previous one, while constantly fending off renewed attacks.

This cycle continues today: a groundbreaking exhibition of Horska’s work at Kyiv’s Ukrainian House Arts Centre took place in early 2024, in defiance of constant Russian air raids. Not long before, stunning murals by Horska, recently rediscovered by contemporary art historians under newer layers of paint and plaster, were destroyed by Russian missile attacks in eastern Ukraine. Regional art museums across Ukraine have been hit by Russian bombs or, as in the case of Kherson, looted by occupying forces.

Perhaps one of the most powerful acts of heritage preservation in the face of Russia’s war is the exhibition “In the Eye of the Storm,” which has toured Madrid, Vienna, and Cologne, and is now at London’s Royal Academy of Arts. The exhibition features important works of modernist art produced in early 20th-century Ukraine, mostly from Ukrainian collections. In late 2022, they were evacuated in secret by train via Poland, under Russian bombardment.

“We loaded the trucks with the paintings and sent them on their way with a military convoy and state guarantees instead of insurance,” curator Konstantin Akinsha told ArtNews. After narrowly avoiding Russian missiles and navigating border closures, “by some miracle, the trucks arrived in Madrid on time for the exhibition.”

The achievements of the team behind the exhibition (curators Akinsha, Katia Denysova, and Olena Kashuba-Volvach, National Art Museum of Ukraine director Yuliya Lytvynets, among others) were not only in preserving the physical works but also in reclaiming their story. After decades of being written out of art history, Ukraine’s artistic heritage must be reimagined and reclaimed. The place of Ukrainian cities – Kyiv, Kharkiv, Odesa – in the history of European modernism needs to be fully established, and the complex identities of Ukraine’s artists recovered.

This is difficult, given the dominance of the “Russian avant-garde” label, which obscures the identities of many artists from the imperial borderlands. Kazymyr Malevych, perhaps the most famous figure in the exhibition and a native of Ukraine, was known to his Polish parents as Kazimierz Malewicz. He worked in Belarus, Russia, and Ukraine and was deeply influenced by the Ukrainian context (he even sometimes referred to himself as Ukrainian).

Another star of the exhibition, Alexandra Exter, was born in what is today Poland to a Belarusian-Greek family and spent time in Kyiv, Paris, Moscow, and St. Petersburg. “In the Eye of the Storm” avoids the trap of nationalizing these artists; its subtitle is “Modernism in Ukraine,” not “Ukrainian Modernism.” Denysova notes that these artists worked with a “twofold agenda”: to assert Ukraine’s cultural autonomy while also engaging with international artistic trends.

The exhibition also highlights important, yet often neglected, cultural dialogues within Ukraine. The brief period of Ukrainian independence after 1917 was a time of cultural rebirth not only for Ukrainians but also for Ukraine’s Jews. While Ukrainian artists founded the Ukrainian Academy of Arts, Ukraine’s Jews created the Kultur Lige, an artistic organization aiming to forge a new Jewish culture for the modern world.

“In the Eye of the Storm” emphasizes this connection between these movements by juxtaposing two large canvases: Anatol Petrytskyi’s “The Invalids” (1924), depicting a family of disabled beggars, and Manuil Shekhtman’s “Jewish Pogrom” (1926), portraying a Jewish family recovering from one of the many anti-Jewish pogroms in Ukraine.

The striking similarity in the bold scale, powerful figurative work, and deep empathy of the pieces reflects their shared roots. Petrytskyi and Shekhtman studied together at the Kyiv Art School in the 1910s; their teachers there later helped found the Ukrainian Academy of Art. The influence of one of those teachers, Mykhailo Boichuk, who famously synthesized Ukrainian Byzantine iconography with modernist aesthetics, can be seen clearly in the stylized figures of Shekhtmen’s grieving pogrom victims.

Neither the Ukrainian Academy of Arts nor the Kultur Lige lasted long; both were absorbed into Soviet institutions within a few years of the Bolshevik takeover of Ukraine, and both modernist projects were annihilated by Stalin’s purges. In the 1930s, hundreds of writers, theater directors, and artists were labeled bourgeois nationalists and executed. Many more were imprisoned, and their manuscripts, books, and artworks destroyed.

Symbolic of this destruction is one of the most striking paintings in the Royal Academy exhibition: Petrytskyi’s portrait of futurist poet Semenko, who was shot by the NKVD in 1937 and buried in an unmarked grave at Bykivnia. The portrait was part of a series of one hundred images that Petrytskyi made of leading figures of the Ukrainian avant-garde movement. The fate of this series is a microcosm of the tragedy of cultural life in early 20th century Ukraine: only nineteen of the original one hundred survived.

It is difficult to maintain artistic institutions in regions under the control of aggressive empires, but Ukraine’s artistic legacy has repeatedly fought back and thrived despite every colonial assault by Russia. This multi-generational salvage operation ensures that art lovers worldwide can appreciate Ukrainian modernism.

Yet the story of survival is inseparable from the story of destruction. The joy of seeing Petrytskyi’s work in London is tempered by the knowledge that many of his works were lost forever. Similarly, the thrill of seeing Horska exhibited in Kyiv is overshadowed by the destruction of her murals in Donetsk by Russian shelling. Ukraine’s lost avant-garde artworks could fill an exhibition space far larger than the one at the Royal Academy.

The storm, clearly, is not over.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Ukrainian brand of silk scarves OLIZ and the fundraising platform UNITED24 released a charity collection dedicated to works of art that were stolen or destroyed by Russia.

This collection includes prints with works of Polina Raiko (her house museum in occupied Oleshki was destroyed after russians blew up the Kahkovka dam), Arkhip Kuindzhi (the Mariupol museum was looted by russians and destroyed with an aerial bomb; the fate of his works is unknown), mosaics from Saint Michael cathedral (the mosaics were moved to Moscow while the cathedral was demolished by soviets in 1938) and paintings from the Kherson museum (almost all the exhibit were stolen by russians).

You can take a look, read more about each piece, and purchase shawls and scarves here: https://u24.gov.ua/stolenart

#ukrainian culture#united24#russian war crimes#russian war in ukraine#nation of thives#cultural apropriation

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Every painting, every graphic work, every piece of artwork, everything we identify, is indisputable proof that the stolen works (at least these) are in the hands of Russian art looters.

Ukraine’s Kherson Art Museum claimed 100 artworks were looted by Russian forces, citing a “propaganda video” filmed in a Crimean museum. This startling revelation allegedly represents only less than one percent of the cultural treasures plundered from Ukrainian institutions. Another 15,000 objects were reported missing amid extensive trafficking of cultural property during the ongoing war.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Koliadky by Mykola Pymonenko, 1890s

The painting, depicting traditional Ukrainian Christmas caroling with a handmade Bethlehem star, was, among many others, looted by the russian occupiers from the Art Museum in Kherson.

#ukraine#ukrainian art#XIxth#russia is a country of pathetic thieves and looters#Kherson art museum#koliadky#koliada#Ukrainian Christmas#Vintage winter#rural landscape#stand with Ukraine#countryside#khata#zvizda#star of bethlehem#russian war crimes#russia is a terrorist state

272 notes

·

View notes

Text

When Russians weren't looting washing machines, toilets, and used underwear from Ukraine in the early weeks of the invasion, they were looting museums.

As a result of the Ukrainian counter-offensive in the summer of 2022, the Russian army was forced to withdraw from the area around Kherson. On November 11, the city was liberated by the Ukrainian army. One of the many consequences of the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the months of turbulence in the Kherson region has been the devastation of the cultural sector. For example, at the beginning of November 2022, entire collections were removed from the Kherson Art Museum, the Kherson Regional Museum and the Kherson Region National Archives. Tombstones of Russian Tsarist commanders and even the remains of Russian Field Marshal Grigory Potemkin, a confidant of Tsarina Catherine II (Empress Catherine the Great), were looted.

Yep, Putin's troops (I use troops loosely) even took the bones of Grigory Potemkin of "Potemkin village" fame.

The Kherson Regional Museum director, Olga Goncharova, laments the loss of the most valuable collection items. The Russians took ancient Greek amphorae, gold ornaments from steppe nomads, medieval weapons and Orthodox icons to the left bank of the Dnipro River, an area still occupied by Russia. Goncharova says that since the occupying forces withdrew, the museum has also lacked important lists of exhibits and documents proving their historical value. She can therefore only roughly estimate the number of looted objects at around 23,000.

Putin is attempting to eradicate even the idea of Ukraine. That's part of the definition of genocide.

During the Russian invasion, more than 40 museums in the occupied territories were looted, says Ukraine's first deputy prosecutor general, Oleksiy Khomenko. The loss has not yet been fully quantified. "It could take years," he says. By the end of the year, the Ukrainian Ministry of Culture and Information Policy intends to create a register in which all available information on collections located in the occupied territories will be entered. This should later help to find art and valuables. However, this will probably only be possible after the end of the war.

For anybody who"s interested, here's the DW article about Russia looting Ukrainian museums in Ukrainian. 🇺🇦

Де шукати зниклі під час російської окупації колекції музеїв

#invasion of ukraine#museums#kherson#russians looting ukrainian museums#genocide#russia's war of aggression#russian thieves#grigory potemkin#oleksiy khomenko#vladimir putin#русские воры#грабеж#агрессивная война россии#воровство из музеев#владимир путин#путин хуйло#геноцид#путин - военный преступник#путина в гаагу!#союз постсоветских клептократических ватников#руки прочь от украины!#геть з україни#херсон#вторгнення оркостану в україну#деокупація#слава україні!#героям слава!

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

RESOURCES TO LEARN MORE ABOUT UKRAINE IN ENGLISH:

1. News and articles

Hromadske

Kyiv Independent

Ukraïner

2. Twitter

Writings from the war

United24

Ukraine Explainers

Ukrainian Art History

Ukrainian LGBTQ+ Military

ukrartarchive

Alice Zhuravel

Тетяна Denford

Oriannalyla

ліна

Mariya Dekhtyaruk

3. Instagram

Libkos (war photography)

rafaelyaghobzadeh (war photography)

mariankushnir (war photography)

marikinoo (illustrator)

olga.shtonda (illustrator)

polusunya (illustrator)

4. Videos (subtitles)

One day of evacuation with combat medics

Testimonies of tortures and sexual assault done by russians

How village in Kherson region lived under occupation

"Winter on Fire" documentary

Mariupol before and after

Tragedy of Nova Kakhovka dam

City of Izium after deoccupation

Entire village that was held in a basement for a month by russians

Life near the frontline in Zaporizhzhia region

Vovchansk after heavy russian shelling

"20 Days in Mariupol" documentary

5. TikTok

qirimlia

yewleea

thatolgagirl

showmedasha

ukraineisus

new4andy (all of the above accounts are educational, this one funny)

6. Other

National Museum of Holodomor Genocide (Holodomor and Digital History sections on a website have a lot of sources to learn about Holodomor)

Izolyatsia Must Speak (information about torture chamber in the russian-occupied Donetsk)

War Stories from Ukraine

Virtual museum of destruction in Kyiv region

Chytomo (about books and publishing)

Free translated books

Old khata project (photography project about rural architecture)

#feel free to add more reliable sources#please reblog#ukraine#russia#russia is a terrorist state#fuck russia#genocide#stand with ukraine#support ukraine#genocide of ukrainians#russian war crimes#important#video#text#txt#words#war#war photography#photography#news#article#link#resources#ukraine resources#world news#current events#activism#human rights#history#art

410 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ukraine Displays Recovered Artifacts Stolen by Russians

Ukraine has recovered 14 archaeological items stolen by a Russian man who was stopped at a U.S. airport on suspicion of illegally importing artifacts, Ukrainian officials said Friday.

Ukraine’s acting Minister of Culture Rostyslav Karandieiev said the man stole the artifacts from Russian-occupied Ukrainian territory and then tried to transport them into the U.S. At a news conference in Kyiv Friday, Karandieiev showed some of the artifacts to journalists, along with the documentation that Ukraine received.

The recovered items include various types of weaponry, such as axes of different sizes, and date back to periods ranging from the Neolithic to the Middle Ages. One of the oldest is a polished Neolithic axe, dating from approximately 5,000-3,000 years BCE, said Karandieiev.

“It’s safe to say that Ukraine has received a new shipment of weaponry. The only catch is that this weaponry is incredibly ancient,” Karandieiev said with a smile during the public handover of artifacts at the historic Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra, a sacred Orthodox monastic complex.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine, now in its second year, is being accompanied by the destruction and pillaging of historical sites and treasures on an industrial scale, causing losses estimated in the hundreds of millions of euros (dollars), Ukrainian authorities say.

Most of the artifacts returned were handed over to Ukraine during the visit of President Volodymyr Zelenskyy to the United States in September.

The accompanying document disclosed the identity of the individual responsible for the unlawful importation of artifacts, revealing that he hails from Krasnodar, Russia.

The acting director general of Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra, Maksym Ostapenko, estimated the value of the repatriated items to be around $20,000. But he emphasized that each artifact, given its age, is a significant cultural treasure.

Karandieiev also highlighted a case where 16,000 items were found to be missing from the art museum in Kherson after Ukrainian forces liberated the city following a nine-month Russian occupation.

“How long it will take to return our treasures, our artifacts, is hard to say,” he concluded.

#ukraine#russia#Ukraine Displays Recovered Artifacts Stolen by Russians#russian war on ukraine#russian war crimes#russian war criminals#looted#looted art#stolen#ancient artifacts#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations

193 notes

·

View notes

Text

On an unseasonably warm day in October, the silence outside broken by birdsong and artillery fire, Olga Goncharova sat in her office on the ground floor of the Kherson Regional Museum, a bulletproof vest wrapped around the back of her chair, the windows covered with plywood, and cursed the Russians. “They’re vandals, the people who did this,” she said.

Ms Goncharova escaped from Kherson, in southern Ukraine, in the spring of 2022, shortly after Russian troops poured into the city. By the time she returned, in November that year, Kherson had been liberated. The Russians had evacuated to the other bank of the Dnieper river, from which they have been bombing the city ever since. Ms Goncharova wept when she entered the museum where she had worked for over two decades. “There was broken glass everywhere,” she says. “They had torn some of the exhibits out.”

In fact Russian officials, assisted by local collaborators and the museum’s then-director, had removed more than 28,000 artefacts, loaded them onto lorries and shipped them to Crimea, illegally annexed by Russia in 2014. Gone were the ancient coins, the Greek sculptures, the Scythian jewellery, a precious Bukhara sabre—and even the hard drives containing the museum’s catalogue. Three decades ago, Ms Goncharova says, the museum recovered a collection of Gothic bronzes looted by German occupiers during the second world war. Now the Russians have stolen them.

Since Russia’s full-scale invasion began in February 2022, the loss of life and suffering in Ukraine has been great. Many of its museums have been plundered, too. The country’s ministry of culture estimates that over 480,000 artworks have fallen into Russian hands. At least 38 museums, home to nearly 1.5m works, have been damaged or destroyed.

Ukrainian officials have also sent a number of collections to other parts of Europe to protect them from Russian bombs. These include dozens of Ukrainian paintings from the early 20th century, on display at the Royal Museums of Fine Arts in Brussels before travelling to Vienna and London. When the evacuated treasures will return to Ukraine is unclear.

Artists have not been spared either. Ms Goncharova points to a painting of dried flowers and pottery that hangs opposite her desk. The artist, Vyacheslav Mashnytskyi, from Kherson, went missing after Russian troops turned up at his riverside dacha and requisitioned his boat. Friends who stopped by the house days later found traces of blood. Mr Mashnytskyi has not been heard from since.

Putting a price on the stolen works is nearly impossible, since only a fraction had been appraised for insurance purposes. Last April the un estimated that the war had caused $2.6bn-worth of damage to Ukraine’s cultural heritage. That now seems to be a conservative figure. Tracking what the Russians have looted is also a headache. Many Ukrainian museums, especially smaller regional ones, had relied on paper catalogues, often outdated or incomplete, says Mariana Tomyn, an official at the culture ministry. Some of those catalogues have now gone. Efforts to digitise inventories, which began only three years ago, have taken on a new urgency.

Ukraine will seek redress. Prosecutors in Kyiv are investigating Russian officials and Ukrainians involved in the plunder. Mrs Tomyn is working on a new restitution law and the overhaul of an outdated one on the protection of cultural heritage. And since late October a special army unit has begun to monitor damage to cultural sites. But there is little hope of recovering what the occupiers have stolen. Russian officials will ship Ukrainian collections stored in Crimea to Russia if Ukraine retakes the peninsula, says Vyacheslav Baranov, an archaeologist at Ukraine’s National Academy of Sciences.

There have been some breakthroughs. On November 26th, after a long court battle, hundreds of historical treasures from Crimea were returned to Ukraine from the Netherlands. The collection, which includes Scythian gold carvings from the fourth century bc, had been on display at the Allard Pierson Museum in Amsterdam in 2014. Russia demanded the return of the objects to the Crimean museums which had loaned them. The Dutch supreme court ruled in 2021 that they belonged in Ukraine.

They are not the only ones to make their way back. At the Lavra museum complex in Kyiv, Maksym Ostapenko slowly unwraps a bundle of white packing paper. Out of it emerges a Bronze Age battle-axe. Another bundle yields a sixth-century Khazar sword. In the summer of 2022 the weapons, plus a few other objects probably destined for America’s antiquities market, surfaced at John F. Kennedy airport. The American authorities sent them back to Ukraine a year later. Most were probably excavated illegally in southern Ukraine, near Crimea, says Mr Ostapenko, the museum’s director, or discovered by Russian troops digging trenches. Such archaeological looting has thrived in the occupied territories, he adds. “The damage done to cultural heritage is immeasurable"

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

All elections including the presidential vote set to take place next spring are technically cancelled under martial law that has been in effect since the conflict began last year.

"We must decide that now is the time of defence, the time of battle, on which the fate of the state and people depends," Zelensky said in his daily address.

He said it was a time for the country to be united, not divided, adding: "I believe that now is not the (right) time for elections."

The frontline between the warring sides has remained mostly static for almost a year despite a much-touted Ukrainian counter-offensive, with Russian forces entrenched in southern and eastern Ukraine.

Officials from the United States and Europe -- Kyiv's key allies -- are reported to have suggested holding negotiations to end the grinding 20-month-old conflict.

But Zelensky has fiercely denied that Ukraine's counter-offensive has hit a stalemate, or that Western countries were leaning on Kyiv to enter talks.

The United States and other supporters have publicly maintained they are ready to back Kyiv with military and financial aid for as long as it takes to defeat Russia.

Global attention has turned to the Middle East since the October 7 Hamas attack on Israel -- and Zelensky has come under increasing pressure.

Art museum hit in Odesa

Russian strikes overnight in the southern Ukrainian region of Odesa left eight people wounded and damaged a historic art museum, Ukrainian officials said, in the latest barrage of drones and missiles.

Three more were injured in a Russian shelling attack on the southern city of Kherson on Monday, as Kyiv doubled down on its warnings that Russia was planning to pummel Ukraine's energy infrastructure ahead of the winter.

Images released by officials from inside the Odesa Fine Arts Museum showed art ripped from the walls of the 19th-century building and windows blown out by the aerial bombardment.

UNESCO said it "strongly condemns the attack" and that "cultural sites must be protected".

On Monday, Zelensky said that Ukrainian forces had successfully destroyed a major Russian ship in the Kerch shipyard in annexed Crimea.

The president, who was elected in 2019, said in September that he was ready to hold national elections next year if necessary, and was in favour of allowing international observers.

Voting could be logistically difficult due to the large number of Ukrainians abroad and soldiers fighting on the front.

Zelensky's approval rating skyrocketed after the war began, but the country's political landscape has been fractious despite the unifying force of the war.

Former presidential aide Oleksiy Arestovych has announced that he would run against his former boss, after criticising Zelensky over the slow pace of the counter-offensive.

Also on Monday, a close advisor to the commander-in-chief of the Ukrainian army, General Valery Zaluzhny, was killed by an explosive hidden inside a birthday gift.

"Under tragic circumstances, my assistant and close friend, Major Gennadiy Chastiakov, was killed," Zaluzhny wrote on Telegram, saying an investigation had been launched.

Ukrainian prosecutors meanwhile said they had formally notified two senior defence officials that they are suspects in a large-scale fraud case involving the purchase of military uniforms.

Ukraine has been fighting an uphill battle against systemic corruption as part of reforms urged by the West for membership to institutions like the European Union.

2 notes

·

View notes