#Jean-Louis Gaillard

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Frustration when I watched a television show about the Overseas Departments and Haiti during the period of the re-establishment of slavery and in general.

The siege of the Crête at Pierrot in 1802, by A. Raffet, engraving Hébert, 1839

Warning: There are many atrocities I will talk about when we dive into the details of the Haitian Revolution and torture in the reedit in the end . So, don’t read if you’re not up for it.

Completely by chance, I caught the second half of the show "Toussaint Louverture" (though I skipped some parts, I admit) presented by Stéphane in his show "Secrets d’Histoire," which I would qualify as mediocre. However, I was surprised to see that this show, which has always been lenient towards Bonaparte and Louis XVI, finally addresses the horrible re-establishment of slavery and recalls that the second and final abolition of slavery in 1848 was unsatisfactory because financial compensation was given to the colonists, but nothing to the former slaves. The one in 1794 seemed better. The participants of the show indeed say that it was a grave mistake to re-establish slavery, both morally and strategically regarding Haiti. I don't feel they explained how disastrous the consequences were, like how these laws removed brilliant officers from the military, such as Louis Delgrès (although mentioned in the show) or Alexandre Dumas (not to mention many former slaves who served in the military or fought like the group to which belonged Flore Blois Gaillard, who allied with the French revolutionaries against the British forces). This was a severe blow to the army, especially with the laws we could call racial against Black people (though I hesitate to use this term because I'm not sure if the word racist was defined as we understand it today). It was a great blunder—if Bonaparte hadn't had the (stupid) idea to re-establish slavery, perhaps the Overseas Departments wouldn't have fallen under British influence (as for Haiti, I think it would have become independent even without the re-establishment of slavery, and France and Haiti could have been solid allies, but it would have been much less violent with fewer French and Haitian losses). All these wars cost enormous amounts of money, and I believe he wouldn’t have sold Louisiana (frankly, he surely had good reasons, but can you imagine the French revolutionaries, especially those from 1792-1794, even in their worst moments, trying to sell a territory, at least the majority of the Convention? I can't). Moreover, there is no mention of the horrible deportations endured by Guadeloupeans and Haitians to Corsica, whether men, women, or children, under atrocious conditions. The most famous victim is the deputy Jean Louis Annecy (although very forgotten), who died on the island of Elba in 1807.

As usual, revolutionary women are forgotten. There is only a mention of Rosalie, alias Solitude, but there were many who participated in the fight, including Sanité Belair, who was executed by firing squad with her husband, Marie Claire Bonheur, the future Empress of Haiti, Victoria Montou, Dédée Bazile, Cécile Fatiman, Marthe Rose Toto from French Guiana, etc. The list is very long.

Finally, I don't like this whitewashing of Charles Leclerc (they do say that Rochambeau was terrible, at least, but since Leclerc was Bonaparte’s brother-in-law, he surely received some favorable treatment in this show). Here is an excerpt from the beginning of his horrors: "The majority of the deportees were concentrated in Corsica and the island of Elba, where they were used as labor for road construction and fortification restoration starting with the former Black soldiers" (text excerpt from "La guerre des Couleurs" of Pierre Branda and Thierry Lentz) . There was authorization to condemn Black people based on mere suspicion. Moreover, here is a letter Leclerc sent to his brother-in-law Napoleon Bonaparte: "Here is my opinion on this country. We must destroy all the Black people in the mountains, men and women, keep only the children under 12 years old, destroy half of those in the plains, and not leave a single colored man who has worn an epaulette in the colony." To think that I found the orders from the Convention in 1793-1794 frightening because they were ambiguous... Well, another reason why I find Bonaparte much more terrifying than them (already, the torture practiced by the police under Fouché in 1801 was appalling when he allowed it, the deportation without trial of many Jacobins, some of whom died, etc.), it reinforced my belief that he was much worse than the Committee of Public Safety in 1794, who nevertheless committed unforgivable acts in wartime under the infernal situation of internal-external civil war. Leclerc started the drownings in October 1802: it didn't matter whether the victims were civilians or soldiers; they were put on boats that were sunk. This strongly recalls the horrors committed by Carrier. According to Marlene L. Daut, the horrors were such that there were many desertions among French soldiers, which must not have been an easy situation for them because they could be shot for desertion and, even if they survived, forced to avoid returning home to avoid trouble with Napoleonic justice.

Leclerc (and by extension, Bonaparte) fell into the trap that some fighters, victims of an invasion or imminent invasion, have used throughout history, which seems quite old: pretending to ally with their adversaries to buy time, even if it means sacrificing their own to better fight the enemy again (and they certainly don't reach the only ones using this technique). This is what happened with Dessalines: the show doesn’t explain the armed resistance led by the Bélair couple against Leclerc, where they temporarily won victories. However, some believe this uprising might have been premature, although the insurgents weakened Leclerc with certain victories, and consequently, Dessalines allowed Charles and Sanité Bélair to be sacrificed. To be fair, the show I mentioned briefly explains that Henry Christophe and Dessalines did not betray Toussaint; they just wanted to buy time, but there is no mention of the Bélair couple. According to historians Pierre Branda and Thierry Lentz, Dessalines killed two birds with one stone by eliminating a potential rival in the person of Charles Bélair and to lull Leclerc's distrust to better attack when the time comes. In any case, by buying time, they were able to achieve better victories against Leclerc (who surely thought that by compromising Dessalines in the eyes of Black people, the insurgents would no longer dare to fight with him, but he was wrong) and later Rochambeau. Rochambeau continued by increasing atrocities, notably by releasing dogs on Black people and continuing to practice torture. There are allegations that Rochambeau locked Black people in holds and activated sulfur so they would die of asphyxiation. Thierry Lentz and Pierre Branda think it is not impossible that this happened. Bernard Gainot cites Jules Chanlatte from his work "Histoire de la catastrophe de Saint-Domingue" and published by a former sailor, Jean-Baptiste Bouvet de Cissé, in 1824: "Instead of valve boats, another type was invented, where victims of both sexes, piled on top of each other, expired suffocated by sulfur fumes." Whatever the case, the insurgents militarily defeated Rochambeau and the French troops, and their final victory was the Battle of Vertières in November 1803. Following this, Haiti's independence was proclaimed.

Where I totally disapprove is when, in order to try to limit the horrors that the Blacks people have suffered, they explain their reprisals, especially with the horrible massacre of the Whites people in 1804. I have already said in a post that massacre it is absolutely condemnable and atrocious . But imagine the horror of a little less than half of the Haitian population massacred in atrocious suffering, some betrayed by France while they had fought for them, others deported in atrocious conditions and some will never see their home again. I think that if their adversaries who oppressed them and those who applauded them had suffered a quarter of an eighth of the horrors that the Haitians suffered, the carnage would have been even more terrible. I do not want to exonerate the Haitians who took part in the massacre of 1804 from the responsibility but if Bonaparte had not approved such cruel orders (and he is the number 1 person responsible for this carnage), Whites people would not have been killed at least not in large numbers. The historian Thomas Madiou, said "Is it surprising that blacks and men of color used reprisals against whites?" And in any case nothing excuses the attitude of Bonaparte, Rochambeau or Leclerc. In my eyes they behaved like Turreau and Carrier. If we try to exonerate Bonaparte and his clique responsible for these massacres by highlighting the atrocities on the other side, it is a call to also exonerate horrible people like Carrier and Turreau by saying that the Vendéens committed massacre too.

In addition, the show ignored the many Haitians who protected white people from this massacre (Including Marie Claire Bonheur, wife of Dessalines, who nevertheless ordered the massacre I mentioned here: https://www.tumblr.com/nesiacha/758334606594523136/166-years-ago-empress-marie-claire-bonheur-of?source=share) and didn't said that the Polish legionnaires who were sent by Bonaparte to repress them were touched by the horrors that the Blacks suffered and many of them deserted to fight alongside the former slaves (as a form of recognition, the survivors were given Haitian nationality) were spared just like the Germans who had not participated in the slave trade ( but on the second point maybe I am wrong). For my part Rochambeau, Leclerc, Carrier and Turreau are to be put in the same bag concerning their atrocities when they were sent on a mission. Too bad Turreau and Rochambeau did not pay for their atrocities (some say that the fact that Leclerc died of yellow fever is enough karma and Carrier was guillotined and I do not pity him at all)

Finally, this isn't in the show, but I don't like when people say that Bonaparte was "a man of his time" to excuse his actions regarding slavery. No, he reinstated it, which is even worse. Sonthonax, Abbé Grégoire, Jean-Paul Marat, Pierre Gaspard Chaumette, Olympe de Gouges, and many others were also from the same era as Bonaparte and were opposed to slavery. The re-establishment of slavery shocked many French people, and a white man named Monnereau, under the orders of Delgrès, was hanged in Guadeloupe because he rose up against the re-establishment of slavery and drafted Louis Delgrès' last manifesto. While Bonaparte was reinstating slavery, a white man gave his life for the fight against it (and there must have been many examples like Monnereau). So, this argument to whitewash Napoleon doesn't hold up.

P.S.: I first found the information about asphyxiation from Claude Ribbe. However, even as a convinced, even a person like me petty, anti-Napoleon person ( and a bad faith person I admit it), I find him not very credible. Comparing Napoleon to Hitler is one of the most absurd things I ever heard. That's why I'm more cautious about this statement.

My sources for this post are: Bernard Gainot Pierre Branda, Thierry Lentz, "La guerre des couleurs"

#haiti#haitian revolution#napoleon#napoleonic era#rochambeau#charles leclerc#vendée#carrier#Turreau#guadeloupe#slavery

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

Charles Spurgeon et George Muller ! Par le pasteur Jean Louis Gaillard

youtube

0 notes

Text

La mèche de Madame Royale

https://justifiable.fr/?p=2144 https://justifiable.fr/?p=2144 #Madame #mèche #Royale Cette bague contenant une mèche de cheveux de la duchesse d’Angoulême a été adjugée 6 035 € Osenat Combien de mères ont conservé une mèche de cheveux de leur enfant ? Il n’est pas rare de retrouver cette précieuse relique dans un papier de soie. Quelques-uns l’enferment dans un médaillon et cela devient un trésor. Trésor encre plus considéré lorsque les mèches proviennent d’un personnage historique. On dit d’ailleurs que le nombre de mèches conservées provenant de la tête de l’empereur Napoléon est si important que l’on pourrait fabriquer avec elles une perruque. Ce qui serait un comble pour celui que l’on surnommait le « Petit tondu » ! Certaines de ces reliques sont émouvantes et l’on peut comprendre qu’elles représentent autant une valeur sentimentale que financière. Une bague en or jaune (18k), contenant dans un chaton ovale une mèche de cheveux de la duchesse d’Angoulême, sous verre cerclé sur émail, avec cette mention : « Précieuse relique / cheveux de Madame / fille du Roi », a été adjugée 6 035 €, à Versailles, le 17 novembre 2024 par la maison Osenat, Jean-Christophe Chataignie étant au marteau, assisté par les experts Jean-Claude Dey et Arnaud de Gouvion Saint-Cyr, lors de la dispersion de la collection Jean-Louis Noisiez. Cet anneau est orné d’une couronne royale et de deux fleurs de lys sur émail. Il a été gravé à l’intérieur : « Succession Cléry / Hôtel des ventes de Rouen / 10 mars 1896 ». La monture date de la fin du XIXe siècle. Cette mèche avait été remise par Marie-Antoinette à Clèry le 27 janvier 1793. Cette bague provient de la succession de Louise Thérèse Françoise Cléry de Gaillard, épouse Le Besnier, petite fille de Jean-Baptiste Cant Hanet, dit Cléry (1759-1809). Ce dernier, d’abord valet de chambre du duc de Normandie, suivit le roi Louis XVI au Temple (1792-1793), et demeura avec lui jusqu’au jour fatal. Il émigra en Autriche à la suite de Madame Royale, à Itzing où il mourut. Il a laissé un journal de ce qui s’est passé à la Tour du Temple pendant la captivité de Louis XVI, avec les détails de sa mort, qui ont été ignorés jusqu’à ce jour (Londres, Baylis, 1800). Un exemplaire en cartonnage bleu de l’époque, bien complet de ses trois planches, a été vendu 220 €, à Drouot, le 30 novembre 2022, par la maison Magnin Wedry, assistée par l’expert Christian Galantaris. Marie-Thérèse de France, Madame Royale, ou encore la duchesse d’Angoulême, a fait l’objet d’une véritable dévotion. N’a-t-elle pas été la seule rescapée du couple royal ? Une autre « Relique faite d’une mèche de cheveux châtains de la duchesse d’Angoulême, conservée avec un fragment de papier imprimé des mots « Maison de Son Altesse Royale Madame la Dauphine », a été vendue 430 €, à Drouot, le 15 décembre 2022, par la maison Gros & Delettrez, assistée par l’expert Mathilde Lalin-Leprevost. Infos Osenat Versailles, Hôtel des ventes du Château 13 avenue de Saint-Cloud 78000 Versailles Tel. : 01 80 81 90 36 www.osenat.com https://www.actu-juridique.fr/culture/la-meche-de-madame-royale/

0 notes

Text

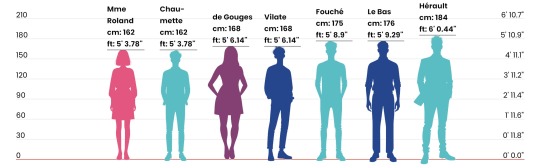

Philippe Le Bas — two passports from the year 1792 have been conserved, the first one stating ”height of five pieds five pouces (176 cm), brown (châtain) hair and eyebrows, gray-blue eyes, short and a bit snub nose, small mouth, round chin, big forehead, ovale face,” the other ”height of five pieds five pouces, brown hair and eyebrows, gray eyes, enlarged nose, middle sized mouth, long chin, ovale face, high forehead.” Cited in Le conventionnel Le Bas: d'après des documents inédits et les mémoires de sa veuve (1901) by Stéfane-Pol, page 26-27.

Élisabeth Le Bas — in Histoire de Robespierre et du coup d’état du 9 thermidor (1865) the historian Ernest Hamel describes Élisabeth in 1794 as ”one of the most charming blondes one could see.” Hamel is confirmed to have met Élisabeth’s son Philippe, but it is less clear if he also met Élisabeth herself. She had dark eyes according to Alphonse Esquiros, who on the other hand is confirmed to have met Élisabeth in her old age.

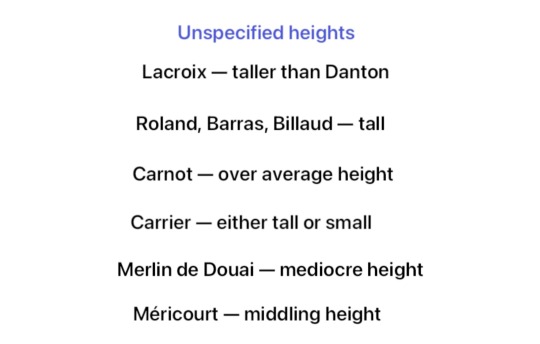

Lazare Carnot — According to Mémoires de Larevellière-Lépeaux: membre du Directoire executif de la République Française et de l'Institut national (1895) ”Carnot is of a height above mediocre. He’s not all that large, but his limbs are and indicate a strong frame; his face, quite well shaped, is slightly marked with smallpoxes. He has a big nose, small water-colored eyes; his hair is blond, thinning, and his forehead is bald; his complexion, a bland white one, does not offer any ruddy shade when he is calm. This pale color, combined with a dry and cunning look, gives him a false and cruel appearance, which repels at first and banishes confidence.”

Georges Couthon — Several contemporaries agree that Couthon looked cute. Pierre Paganel claimed in that he possessed ”a gentle look, a laughing mouth, a countenance which solicited tender affections and promised kindness. His eyes caressed you; his silence attracted you; each of his features expressed a kind feeling and invited you to love him. […] If you imagine this head which seemed to have been composed with a singular predilection, sadly leaning over a body half consumed by premature paralysis; if you consider that his look, marked with habitual pain, in some way accused Providence of having taken away his youth, by taking away the means to spend it happily, you have a fair idea of the keen interest that Couthon inspired in every sensitive man who saw him for the first time.” Barante, an enemy of Couthon, said that his face was ”gentle and pleasant,” his complexion ”dull,” features ”fine and firm,” his look ”gentle and passionate,” and his voice ”persuasive and emotional.” (cited in Georges Couthon (1983) by Albert Soboul). Maurice Gaillard, who met Couthon in May 1794, described his face as ”truly angelic” in a note written to Fouché somewhere during his time as Minister of Police, and in Souvernirs d’un sexagénarie (1833), Antoine Vincent Arnault called him ”the sweet Couthon,” even while describing his execution. In a letter dated September 29 1791 Couthon writes that he’s able to walk to the Legislative Assembly on foot. A year later, September 1792, he was however unable to use his legs and had to be carried, according to the testimony of Jacques-Antoine Dulaure (1794). When exactly Couthon got himself a wheelchair to get around appears to be unknown.

Hérault de Séchelles — A passport dated October 28 1793 documents the following: ”height of 5 pieds 8 pouces (184 cm), brown hair and eyebrows, high forehead, medium sized nose, brown eyes, small mouth” (cited in Un épicurien sous la Terreur; Hérault de Séchelles (1759-1794); d'après des documents inédits (1907) by Emile Dard). In Mémoires sur les règnes de Louis XV et Louis XVI et sur la revolution (1886) Jean-Nicolas Dufort de Cheverny describes Hérault in early 1792 as ”big, well formed, with the most beautiful face possible,” and specifies in a footnote that Hérault ”was one of the most beautiful men in France.” Madame Roland too mentions that Hérault was good looking in her memoirs, noting that ”all these pretty boys seem to me to be poor patriots.” Hérault’s lover Suzanne Giroux de Morency wrote in Illyrine, ou l'écueil de l'inexpérience (1800) that Hérault was ”a beautiful man” and described his eyes as ”big” and ”superb.”

Pierre Gaspard Chaumette — a passport from 1784 states the following: ”height of five pieds, blond hair and eyebrows, blue eyes, a small hole under the left eye, somewhat large nose.” Cited in Mémoires de Chaumette sur la Révolution du 10 août 1792 (1893). According to Pierre Paganel, ”Chaumette was small, his waist thick and squat, his face broad and flat; he looked humble, his eyes were shy and delicate, and his countenance, if I may put it that way, was tearful. He possessed to the supreme degree the silent game of hypocrisy. Through modest and dreamy language one perceived a very resolute character. Long black [sic!] hair, coarse clothing, a more than slovenly outfit, hid a deep ambition from being seen.”

Paul Barras — According to Mémoires de Larevellière-Lépeaux: membre du Directoire executif de la République Française et de l'Institut national (1895) ”He was tall, strong, vigorous and very well built. He had quite handsome features, and was overall a very handsome man; but he looked harsh, his countenance was gloomy, his look sinister; serenity rarely appeared on his face. When he smiled, his smile, gracious in itself, resembled those rays of sunlight escaping through dark clouds which soon intercept them. He had a bad tone in society, and lacked distinction. He had neither that which comes from a noble soul and an elevated spirit, nor that which a careful education and association with good company gives. With a fine figure and a masculine face, he had no external dignity, and always retained something of that common and bold air that bad society gives.”

Sophie Momoro — Jean-Baptiste Laboureau, who met Sophie while they were both imprisoned in the Prison de Port-libre, wrote in his diary on March 19 1794 that she ”is very mundane; passable features, terrible teeth, the voice of a fishwife, an awkward appearance, that's what constitutes Madame Momoro.”

Théroigne de Mericourt — described as being of ”middling height” by former deputy Jacques-Antoine Dulaure in 1823 and psychiatrist Jean-Etienne-Dominique Esquirol in 1838, and ”somewhat above middle size of women” by English visitor John Moore in 1792. Dulaure writes she ”bore on her face the characteristics of vivacity and audacity,” Moore that she ”has a martial air, which in a man would not be disagreeable.” Théroigne was brown according to Dulaure, while Esquirol adds that she had brown (chátain) hair and big blue eyes. Moore describes her costume as ”a kind of English riding habit, but her jacket was the uniform of the national guards,” while Dulaure recalls ”with her blue cloth costume, her hat on her ear, her cane in her hand and sometimes pistols in her pockets, she appeared wherever trouble broke out.” Esquirol, who met Théroigne when she was hospitalized at the Pitié-Salpêtrière claims that she at the time was of ”mobile physiognomy, lively, clear, and even elegant gait.”

Honoré Gabriel Riqueti de Mirabeau — In Les Mirabeau: nouvelles etudes sur la societe francaise au XVIIIe siecle (1891) Louis de Loménie mentions a letter dated 1754, where Mirabeau’s uncle reported to his brother that ”your son is as ugly as Satan’s.” He’s five years old maybe chill a little? An equally unflattering descriptions is given by François René Chateaubriand, who in Mémoires d’Outre-tombe(1860) wrote that Danton was ”inferior in ugliness to Mirabeau,” and similar words can again be found in Mémoires de la Societé d’agriculture, commerce, sciences et arts du department de la Marse, Chalons-sur-Marne (1862): ”With Danton as with Mirabeau, speech was greatly aided by the gaze, the gesture and that energetic ugliness of the face.” In Considerations on the principal events of the French Revolution (1818) Germaine de Staël writes: ”The eye that was once fixed on [Mirabeau’s] countenance was not likely to be soon withdrawn: his immense head of hair distinguished him from amongst the rest, and suggested the idea that, like Samson, his strength depended on it; his countenance derived expression even from its ugliness; and his whole person conveyed the idea of irregular power, but still such power as we should expect to find in a tribune of the people.” A child who had seen Mirabeau during the procession that preceded the opening of the provincial Estates later recalled that he had ”thick hair, brushed up above his broad forehead, and ending in thick curls at the level of the ears” and again that ”there was something imposing about his ugliness.” (cited in Mirabeau(1973) by Antonia Vallentin). Finally, in a letter from 1770, Mirabeau’s uncle writes that ”I found him ugly, but he has not a bad physiognomy: and he has, behind the ravages of the smallpox, and features which are much changed, something graceful, intellectual and noble.” (cited in Mirabeau: A Life-history, in Four Books (1848) by John Stores Smith).

Merlin de Douai — according to Mémoires de Larevellière-Lépeaux : membre du Directoire executif de la République Française et de l'Institut national (1895): ”his size is mediocre; he is thin, dry and gaunt. The thinness of his face makes his large mouth, his big eyes and his long nose stand out rather unfavorably. He is devoid of grace and dignity in his deportment. When one hears him speak for the first time in a somewhat raised tone, one is singularly shocked by the strange character of his voice; it is false, sharp, uneven and has something wild about it.”

Olympe de Gouges — A police description cited on page 35 of Olympe de Gouges (1989) by Oliver Blanc gives the following information: ”height of 1,68 meters, oval face, brown hair and eyebrows, brown eyes, a slightly aquiline nose, an uncovered forehead, a round, full chin, a medium mouth.”

Joseph Fouché — According to Fouché: les silences de la pieuvre (2014) by Emmanuel de Waresquiel, measurements made of Fouché’s skeleton in 1873 show that he was 175 cm tall. He was meagre according to both Philippe-Paul de Ségur (in Mémoires du général comte de Ségur (1894-1895)), Charles Nodier (Souvenirs de la Révolution et de l'Empire (1850)), Mathieu Molé and Victorine de Chastenay (Mémoires de madame de Chastenay, 1771-1815: L'empire. La restauration. Les cent-jours(1897)), who also all agree that there was something piercing about Fouché’s eyes. Said eyes were small according to Chastenay (who also adds that they were very close together) and Ségur. Nodier writes that they were of a light blue colour, while Chastenay calls them ”very red,” and Ségur and Molé ”bloody.” Chastenay, Ségur and Nodier do also each call Fouché pale, the latter even writing that it was ”a particular pallor, which belonged only to him” noting that it was clearly different from someone with anemia or other illness. This, combined with the testimony of Fouché’s ”red eyes,” hint at the idea that he was albino. In his memoirs (1896), Barras does indeed outright call Fouché’s child ”an actual albino,” while Molé writes Fouché had ”the dry hair of an albino.” Speaking of his hair, Ségur writes that it was ”flat and rare” and that Fouché was towheaded (cheveux couleur de filasse). Chastenay too underlines that ”in his youth his hair had been or should have been a very bland blond.” According to Barras, both Fouché and his wife Bonne-Jeanne Coiquaud did however have red hair. According to the memoirs(1834) of Charlotte Robespierre, ”Fouché wasn’t handsome,” and according to those of Barras, Fouché and his wife were a ”hideous couple.” Molé instead writes that he had ”fine features,” and that ”something at once ferocious, elegant and agile makes him resemble a panther.” Ségur on the other hand likened Fouché’s physiognomy to that of ”an agitated weasel” and writes that he had a ”long and mobile” face. Fouché ”spoke with ease” according to Chastenay, had ”a dry voice” according to Molé, and had a ”brief and jerky speech, consistent with his restless and convulsive attitude” according to Ségur.

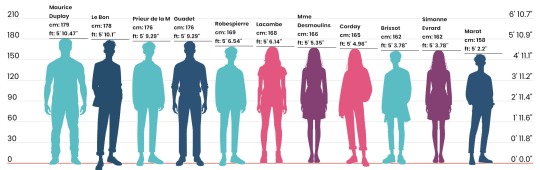

Manon Roland — In her memoirs, Manon gives the following detailed description of herself: ”At fourteen, like today, I was about five pieds (162 cm) tall; my size had acquired all its growth; the leg well shaped, the foot well placed, the hips very raised, the chest broad, the shoulders effaced, the attitude firm and graceful, the walk rapid and light; this is what first hit the eye. There was nothing striking about my face, only great freshness, a lot of softness and expression. By detailing each of the features, one can ask oneself: Where is the beauty? Nothing is regular, everything pleases. The mouth is a little big; there are a thousand prettier ones; not one has a more tender and seductive smile. The eyes, on the contrary, are not very large, their iris is a grey-chestnut; but placed not very deep in the sockets, with an open, frank, lively and gentle gaze, crowned with brown eyebrows the same colour as the hair, and well defined, they vary in their expression, like the affectionate soul whose movements they paint; serious and proud, they sometimes surprise; but they caress much more, and always wakes you up. My nose was causing me some pain, I found it a little big at the tip; however, I considered that overall, and especially in profile, it did not spoil anything else. The broad, bare forehead, little covered at that age, supported by the very high orbit of the eye, and in the middle of which veins in Greek vanished at the slightest emotion, was far from the the insignificance that one finds on so many faces. As for the fairly upturned chin, it has precisely the characteristics that the physiognomies indicate for those of voluptuousness; when I bring them together with everything that is particular to me, I doubt that anyone was ever more made for it, and enjoyed it less. Bright rather than very white complexion, dazzling colors, frequently enhanced by the sudden redness of boiling blood, excited by the most sensitive nerves; the soft skin, the rounded arm, the pleasant hand, without being small, because its elongated and slender fingers announce skill and retain grace; fresh, tidy teeth; the plumpness of perfect health: such are the treasures that nature had given me. I have lost many, especially those who are plump and fresh; those who remain with me still hide, without me using any art, five to six of my years; and the very people who see me every day need me to tell them my age, to believe that I am over thirty-two or thirty-three. […] My portrait has been drawn several times, painted and engraved: none of these imitations gives the idea of my person; it is difficult to grasp because I have more soul than face, more expression than features. […] Camille Desmoulins was right to be surprised that at my age, and with so little beauty, I had what he calls admirers.” Interestingly though, despite describing herself as only 162 cm tall, Manon gets called tall by both her friend Helen Maria Williams in Memoirs Of The Reign Of Robespierre (1795), as well as by Honoré Riouffe (who claimed to have seen her at the Conciergerie prison) in Mémoires d’un détenu pour servir à l’histoire de la tyrannie de Robespierre(1795).

Jean Marie Roland — in 1792, John Moore described Roland as ”about fifty years of age, tall, thin, of a mild countenance and pale complexion. His drefs, every time I have seen him, has been the same, a drab-coloured suit lined with green silk, his grey hair hanging loose” and that his ”manner is unassuming and modest” in his diary. According to Mémoires du marquis de Ferrières: avec une notice sur sa vie, des notes et des éclaircissemens historiques (1821) ”Roland looked like Plutarch or a Quaker in his Sunday best. Flat hair, little powder, a black coat, shoes with cords instead of buckles, made him look like a rhinoceros. However, he had a decent and pleasant face.”

Charles Alexis Brûlart de Genlis, the marquis de Sillery — in Memoirs Of The Reign Of Robespierre(1795) Helen Maria Williams writes Sillery had white hair by the time of his execution in October 1793.

Jean Baptiste Carrier — According to Pierre Paganel, ”Carrier was taller than the ordinary. He had an unpleasant face, but it was not very sinister.” At the time of his trial, a witness did instead describe him as "small, thick, stocky, he had black, frizzy hair and a swarthy complexion, his enormous, hanging lower lip gave him the vague appearance of a Negro" (cited in Carrier et la Terreur nantaise (1987) by Jean-Joël Brégeon).

Jacques Nicolas Billaud-Varennes — Jacques Bernard, who met Billaud in 1800, wrote that ”he was tall, his broad, pale face did not reveal, by any external sign, a very energetic soul. His countenance was full of gentleness, he wore a wig of red hair, in the Jacobin style. His accent, his manners announced affability and a distinction that his costume, more than simple, could not erase. Trousers, a coarse canvas jacket, a wide-brimmed hat, large shoes, such was the costume of this Spartan.” Cited in Billaud-Varenne, membre du Comité de salut public : mémoires inédits et correspondance / accompagnés de notices biographiques sur Billaud-Varenne et Collot-d'Herbois par Alfred Bégis(1893)

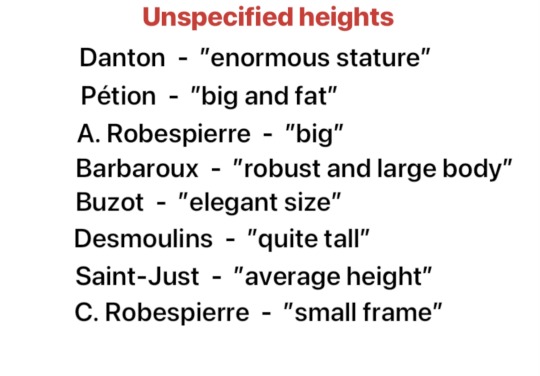

Jean-François Lacroix — According to the memoirs (1913) of Théodore de Lameth, Lacroix was ”of a frightening size and eloquence.” J.G Millingen agrees, writing in his Recollections of Republican France 1791-1801 (1848) that Lacroix was a man of ”colossal stature.” Millingen also attributes the following words to Lacroix, said at the foot of the scaffold: ”Do you see that axe, Danton? Well, even when my head is struck off I shall be taller than you!”

Joachim Vilate — height of 5 pieds, 2 pouces (168 cm), brown (châtains) hair and eyebrows. Descriptions given in 1795 and cited in Les derniers montagnards (1874) by Jules Claretie.

Frev appearance descriptions masterpost

Jean-Paul Marat — In Histoire de la Révolution française: 1789-1796 (1851) Nicolas Villiaumé pins down Marat’s height to four pieds and eight pouces (around 157 cm). This is a somewhat dubious claim considering Villiaumé was born 26 years after Marat’s death and therefore hardly could have measured him himself, but we do know he had had contacts with Marat’s sister Albertine, so maybe there’s still something to this. That Marat was short is however not something Villaumé is alone in claiming. Brissot wrote in his memoirs that he was ”the size of a sapajou,” the pamphlet Bordel patriotique (1791) claimed that he had ”such a sad face, such an unattractive height,” while John Moore in A Journal During a Residence in France, From the Beginning of August, to the Middle of December, 1792 (1793) documented that ”Marat is little man, of a cadaverous complexion, and a countenance exceedingly expressive of his disposition. […] The only artifice he uses in favour of his looks is that of wearing a round hat, so far pulled down before as to hide a great part of his countenance.” In Portrait de Marat (1793) Fabre d’Eglantine left the following very detailed description: ”Marat was short of stature, scarcely five feet high. He was nevertheless of a firm, thick-set figure, without being stout. His shoulders and chest were broad, the lower part of his body thin, thigh short and thick, legs bowed, and strong arms, which he employed with great vigor and grace. Upon a rather short neck he carried a head of a very pronounced character. He had a large and bony face, aquiline nose, flat and slightly depressed, the under part of the nose prominent; the mouth medium-sized and curled at one corner by a frequent contraction; the lips were thin, the forehead large, the eyes of a yellowish grey color, spirited, animated, piercing, clear, naturally soft and ever gracious and with a confident look; the eyebrows thin, the complexion thick and skin withered, chin unshaven, hair brown and neglected. He was accustomed to walk with head erect, straight and thrown back, with a measured stride that kept time with the movement of his hips. His ordinary carriage was with his two arms firmly crossed upon his chest. In speaking in society he always appeared much agitated, and almost invariably ended the expression of a sentiment by a movement of the foot, which he thrust rapidly forward, stamping it at the same time on the ground, and then rising on tiptoe, as though to lift his short stature to the height of his opinion. The tone of his voice was thin, sonorous, slightly hoarse, and of a ringing quality. A defect of the tongue rendered it difficult for him to pronounce clearly the letters c and l, to which he was accustomed to give the sound g. There was no other perceptible peculiarity except a rather heavy manner of utterance; but the beauty of his thought, the fullness of his eloquence, the simplicity of his elocution, and the point of his speeches absolutely effaced the maxillary heaviness. At the tribune, if he rose without obstacle or excitement, he stood with assurance and dignity, his right hand upon his hip, his left arm extended upon the desk in front of him, his head thrown back, turned toward his audience at three-quarters, and a little inclined toward his right shoulder. If on the contrary he had to vanquish at the tribune the shrieking of chicanery and bad faith or the despotism of the president, he awaited the reéstablishment of order in silence and resuming his speech with firmness, he adopted a bold attitude, his arms crossed diagonally upon his chest, his figure bent forward toward the left. His face and his look at such times acquired an almost sardonic character, which was not belied by the cynicism of his speech. He dressed in a careless manner: indeed, his negligence in this respect announced a complete neglect of the conventions of custom and of taste and, one might almost say, gave him an air of ressemblance.”

Albertine Marat — both Alphonse Ésquiros and François-Vincent Raspail who each interviewed Albertine in her old age, as well as Albertine’s obituary (1841) noted a striking similarity in apperance between her and her older brother. Esquiros added that she had ”two black and piercing eyes.” A neighbor of Albertine claimed in 1847 that she had ���the face of a man,” and that she had told her that ”my comrades were never jealous of me, I was too ugly for that” (cited in Marat et ses calomniateurs ou Réfutation de l’Histoire des Girondins de Lamartine (1847) by Constant Hilbe)

Simonne Evrard — An official minute from July 1792, written shortly after Marat’s death, affirmed the following: “Height: 1m, 62, brown hair and eyebrows, ordinary forehead, aquiline nose, brown eyes, large mouth, oval face.” The minute for her interrogation instead says: “grey eyes, average mouth.”Cited in this article by marat-jean-paul.org. When a neighbor was asked whether Simonne was pretty or not around two decades after her death in 1824, she responded that she was ”très-bien” and possessed ”an angelic sweetness” (cited in Marat et ses calomniateurs ou Réfutation de l’Histoire des Girondins de Lamartine (1847) by Constant Hilbe) while Joseph Souberbielle instead claimed that ”she was extremely plain and could never have had any good looks.”

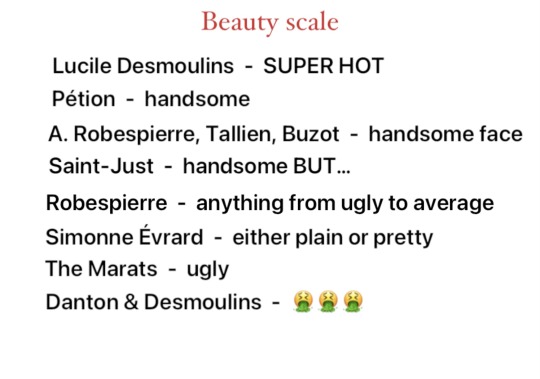

Maximilien Robespierre — The hostile pampleth Vie secrette, politique et curieuse de M. J Maximilien Robespierre… released shortly after thermidor by L. Duperron, specifies Robespierre’s hight to have been ”five pieds and two or three pouces” (between 165 and 170 cm). He gets described as being ”of mediocre hight” by his former teacher Liévin-Bonaventure Proyart in 1795, ”a little below average height” by journalist Galart de Montjoie in 1795, ”of medium hight” by the former Convention deputy Antoine-Claire Thibaudeau in 1830 and ”of middling form” by his sister in 1834, but ”of small size” by John Moore in 1792 and Claude François Beaulieu in 1824. The 1792 pampleth Le véritable portrait de nos législateurs… wrote that Robespierre lacked ”an imposing physique, a body à la Danton,”supported by Joseph Fiévée who described him as ”small and frail” in 1836, and Louis Marie de La Révellière who said he was ”a physically puny man” in his memoirs published 1895. For his face, both François Guérin (on a note written below a sketch in 1791), Buzot in his Mémoires sur la Révolution française (written 1794), Germaine de Staël in her Considerations on the Principal Events of the French Revolution (1818), a foreign visitor by the name of Reichardt in 1792 (cited in Robespierre by J.M Thompson), Beaulieu and La Révellière-Lépeaux all agreed that he had a ”pale complexion.” Charlotte does instead describe it as ”delicate” and writes that Maximilien’s face ”breathed sweetness and goodwill, but it was not as regularly handsome as that of his brother,” while Proyart claims his apperance was ”entirely commonplace.” The foreigner Reichardt wrote Robespierre had ”flattened, almost crushed in, features,” something which Proyart agrees with, writing that his ”very flat features” consisted of ”a rather small head born on broad shoulders, a round face, an indifferent pock-marked complexion, a livid hue [and] a small round nose.” Thibaudeau writes Robespierre had a ”thin face and cold physiognomy, bilious complexion and false look,” Duperron that ”his colouring was livid, bilious; his eyes gloomy and dull,” something which Stanislas Fréron in Notes sur Robespierre (1794) also agrees with, claiming that ”Robespierre was choked with bile. His yellow eyes and complexion showed it.” His eyes were however green according to Merlin de Thionville and Guérin while Proyart insists they were ”pale blue and slightly sunken.” Etienne Dumont, who claimed to have talked to Robespierre twice, wrote in his Souvernirs sur Mirabeau et sur les deux premières assemblées législatives (1832) that ”he had a sinister appearance; he would not look people in the face, and blinked continually and painfully,” and Duperron too insists on ”a frequent flickering of the eyelids.” Both Fréron, Buzot, Merlin de Thionville, La Révellière, Louis Sébastien Mercier in his Le Nouveau Paris (1797) and Beffroy de Reigny in Dictionnaire néologique des hommes et des choses ou notice alphabétique des hommes de la Révolution, qui ont paru à l’Auteur les plus dignes d’attention… (1799) made the peculiar claim that Robespierre’s face was similar to that of a cat. Proyart, Beaulieu and Millingen all wrote that it was marked by smallpox scars, ”mediocretly” according to Proyart, ”deeply” according to the other two. Proyart also writes that Robespierre’s hair was light brown (châtain-blond). He is the only one to have described his hair color as far as I’m aware.

For his clothes, both Montjoie, Louis-Sébastien Mercier in 1801, Helen Maria Williams in 1795, Duperron, Millingen and Fiévée recall the fact that Robespierre wore glasses, the first two claiming he never appeared in public without them, Duperron that he ”almost always” wore them, and Millingen that they were green. Pierre Villiers, who claimed to have served as Robespierre’s secretary in 1790, recalled in Souvenirs d'un deporté (1802) that Robespierre ”was very frugal, fastidiously clean in his clothes, I could almost say in his one coat, which was was of a dark olive colour,” but also that ”He was very poor and had not even proper clothes,” and even had to borrow a suit from a friend at one point. Duperron records that ”[Robespierre’s] clothes were elegant, his hair always neat,” Millingen that ”his dress was careful, and I recollect that he wore a frill and ruffles, that seemed to me of valuable lace,”Charlotte that ”his dress was of an extreme cleanliness without fastidiousness,” Williams that he ”always appeared not only dressed with neatness, but with some degree of elegance, and while he called himself the leader of the sans-culottes, never adopted the costume of his band. His hideous countenance […] was decorated with hair carefully arranged and nicely powdered,” Fiévée that Robespierre in 1793 was ”almost alone in having retained the costume and hairstyle in use before the Revolution,” something which made him ressemble ”a tailor from the Ancien régime,” Thibadeau that ”he was neat in his clothes, and he had kept the powder when no one wore it anymore,” Germaine de Staël that ”he was the only person who wore powder in his hair; his clothes were neat, and his countenance nothing familiar,” Révellière writes that Robespierre’s voice was ”toneless, monotonous and harsh,” Beaulieu that it ”was sharp and shrill, almost always in tune with violence,” and Thinadeau that his ”tone” was ”dogmatic and imperious.”

Augustin Robespierre — described as ”big, well formed, and [with a] face full of nobility and beauty” in the memoirs of his sister Charlotte. Charles Nodier did in Souvenirs, épisodes et portraits pour servir à l'histoire de la Révolution et de l'Empire (1831) recall that Augustin had a ”pale and macerated physiognomy” and a quite monotonous voice.

Charlotte Robespierre — an anonymous doctor who claimed to have run into Charlotte in 1833, the year before her death, described her as ”very thin.” Jules Simon, who reported to have met her the following year, did him too describe her as ”a very thin woman, very upright in her small frame, dressed in the antique style with very puritanical cleanliness.”

Camille Desmoulins — described as ”quite tall, with good shoulders” in number 16 of the hostile journal Chronique du Manège (1790). Described as ugly by both said journal, the journal Journal Général de la Cour et de la Ville in 1791, his friend François Suleau in 1791, former teacher Proyart in 1795, Galart de Montjoie in 1796, Georges Duval in 1841, Amandine Rolland in 1864 (she does however add that it was ”with that witty and animated ugliness that pleases”) and even himself in 1793. Proyart describes his complexion as ”black,” Duval as ”bilious.” Both of them agree in calling his eyes ”sinister.” Duval also claims that Desmoulins’ physiognomy was similar to that of an ospray. Montjoie writes that Desmoulins had ”a difficult pronunciation, a hard voice, no oratorical talent,” Proyart that ”he spoke very heavily and stammered in speech” and Camille himself that he has ”difficulty in pronunciation” in a letter dated March 1787, and confesses ”the feebleness of my voice and my slight oratorical powers” in number 4 of the Vieux Cordelier. In his very last letter to his wife, dated April 1 1794, Desmoulins reveals that he wears glasses.

Lucile Desmoulins — The concierge at the Sainte-Pélagie prison documented the following when Lucille was brought before him on April 4 1794: ”height of five pieds and one and a half pouce (166 cm). Brown hair, eyebrows and eyes. Middle sized nose and mouth. Round face and chin. Ordinary front. A mark above the chin on the right.” Cited in Camille et Lucile Desmoulins: un rêve de république (2018). Described as beautiful by the journal Journal Général de la Cour et de la Ville in 1791 (it specifies her to be ”as pretty as her husband is ugly”), former Convention deputy Pierre Paganel in 1815, Louis Marie Prudhomme in 1830, Amandine Rolland in 1864 and Théodore de Lameth (memoirs published 1913).

Georges Danton — Described as having an ugly face by both Manon Roland in 1793, Vadier in 1794, the anonymous pamphlet Histoire, caractère de Maximilien Robespierre et anecdotes sur ses successeurs in 1794, Louis-Sébastien Mercier in 1797, Antoine Fantin-Desodoards in 1807, John Gideon Millingen in 1848, Élisabeth Duplay Lebas in the 1840s, the memoirs (1860) of François-René Chateaubriand (he specifies that Danton had ”the face of a gendarme mixed with that of a lustful and cruel prosecutor”) as well as the Mémoires de la Societé d’agriculture, commerce, sciences et arts du department de la Marse, Chalons-sur-Marne (1862). As reason for this ugliness, Millingen lifts his ”course, shaggy hair” (that apparently gave him the apperance of a ”wild beast”), the fact he was deeply marked with small-poxes, and that his eyes were unusually small (”and sparkling in surrounding darkness”), while Chateaubriand instead underlines that he was ”snub-nosed,” with ”windy nostrils [and] seamed flats.” Mercier writes that Danton’s face was ”hideously crushed.” The former Convention deputy Alexandre Rousselin (1774-1847) reported in his Danton — Fragment Historique that Danton developed a lip deformity after getting gored by a bull as a baby, had his nose crushed by another bull, got trampled in the face by a group of pigs and finally survived ”a very serious case of smallpoxes, accompanied by purpura.” In 1792, John Moore reported that ”Danton is not so tall, but much broader than Roland; his form is coarse and uncommonly robust,” while Vadier claims that Danton possessed a ”robust form, colossal eloquence,” the anonymous pamphlet that ”he was very strong, he said himself that he had athletic forms,” Desodoards that he ”held the nature of athletic and colossal forms,” Chateaubriand that he was ”a vandal in the size of Goth” (don’t know who he’s referring to), Pierre Paganel (in Essai historique et critique sur la révolution française: ses causes, ses résultats, avec les portraits des hommes les plus célèbres (1815)) that he was of an ”enormous stature,” while the pamphlet described him as a ”gigantic orator” whose voice ”shook the vaults of the hall.” René Levasseur in 1829, John Moore, Millingen, Paganel and Desodoards all agreed with this, the first four writing that Danton possessed a ”stentorian voice,” the latter that he had ”a very strong voice, without being sonorous or flexible.” In her memoirs (1834) Charlotte Robespierre claims that ”[Danton] did not at all conserve the dignity suited to the representative of a great people in his manners; his toilette was in disorder.”

Louis Antoine Saint-Just — In Saint-Just (1985) Bernard Vinot writes that Saint-Just’s childhood friend Augustin Lejeune recalled his “honest physiognomy,” and that his sister Louise would evoke her brother’s ”great beauty” for her grandchildren (I unfortunately can’t find the original sources here). The elderly Élisabeth Le Bas too stated that ”he was handsome, Saint-Just, with his pensive face, on which one saw the greatest energy, tempered by an air of indefinable gentleness and candor” (testimony found in Les Carnets de David d’Angers (1838-1855) by Pierre-Jean David d’Angers, cited in Veuve de Thermidor: le rôle et l'influence d'Élisabeth Duplay-Le Bas (1772-1859) sur la mémoire et l'historiographie de la Révolution française (2023) by Jolène Audrey Bureau, page 127). In Souvenirs de la révolution et de l’empire, Charles Nodier (who was twelve years old when he met Saint-Just…) agrees in calling him ”handsome,” but adds that he ”was far from offering this graceful combination of cute features with which we have seen it endowed by the euphemistic pencil of a lithograph,” had an ”ample and rather disproportionate chin,” that ”the arc of his eyebrows, instead of rounding into smooth and regular semi-circles, was closer to a straight line, and its interior angles, which were bushy and severe, merged into one another at the slightest serious thought that one saw pass on his forehead” and finally that ”his soft and fleshy lips indicated an almost invincible inclination to laziness and voluptuousness.” How would you know what his lips were like, Nodier. In Essai historique et critique sur la révolution française (1815) Pierre Paganel writes that Saint-Just had ”regular features and austere physiognomy.” He describes his complexion as ”bilious” while Nodier calls it ”pale and grayish, like that of most of the active men of the revolution.” Similar to Élisabeth’s description, Nodier writes that Saint-Just’s eyes were big and ”usually thoughtful,” while Paganel instead writes they were ”small and lively.” Saint-Just was of ”average height” according to Paganel, but ”of small stature” according to Nodier. According to Paganel, Saint-Just had a ”healthy body [and] proportions which expressed strength,” while Saint-Just’s colleague Levasseur de la Sarthe instead wrote in his memoirs that he was ”weak in body, to the point of fearing the whistling of bullets.” Finally, Paganel also gives the following details: ”large head, thick hair, disdainful gaze, strong but veiled voice, a general tinge of anxiety, the dark accent of concern and distrust, an extreme coldness in tone and manners.” In Lettre de Camille Desmoulins, député de Paris à la Convention, August général Dillon en prison aux Madelonettes (1793) Desmoulins jokingly writes that ”one can see by [Saint-Just’s] gait and bearing that he looks upon his own head as the corner-stone of the Revolution, for he carries it upon his shoulders with as much respect and as if it was the Sacred Host.” In Histoire de la Révolution française(1878), Jules Michelet claims that Élisabeth Le Bas had told him that this portrait, depicting Saint-Just as having ”a very low forehead, [with] the top of his head flattened, so that his hair, without being long, almost touched his eyes,” was similar to what he had looked like.

Jacques-Pierre Brissot — The following was documented after Brissot had been arrested at Moulins on June 10 1793 — ”height of five pieds (162 cm), a small amount of flat dark brown hair, eyebrows of the same color, high forehead and receding hairline, gray-brown, quite large and covered eyes, long and not very large nose, average mouth, long chin with a dimple, black beard, oval face narrow at the bottom” (cited in J.-P. Brissot mémoires (1754-1793); [suivi de] correspondance et papiers (1912)). In Journal During a Residence in France, from the Beginning of August, to the Middle of December, 1792 John Moore described Brissot as ”a little man, of an intelligent countenance, but of a weakly frame of body” and claimed that a person had told him that Brissot had told him that he is ”of so feeble a constitution” that he won’t be able to put up any resistance was someone try to assassinate him.

Jérôme Pétion — described as ”big and fat” (grand et gros) by Louis-Philippe in 1850 (cited in The Croker Papers: the Correspondence and Diaries of the late right honourable John Wilson Croker… (1885) volume 3, page 209). Manon Roland wrote in her memoirs that Pétion ”had nothing to regret physically; his size, his face, his gentleness, his urbanity, speak in his favor” as well as that he ”spoke fairly well,” a descriptions which Louis Marie Prudhomme partly agreed with, himself recording that Pétion ”had a proud countenance, a fairly handsome face, an affable look, a gentle eloquence, movements of talent and address; but his manners were composed, his eyes were dull, and he had something glistening in his features which repelled confidence” in Paris pendant le révolution (1789-1798) ou le nouveau Paris (1798). In Quelques notices pour l’histoire, et le récit de mes périls depuis le 31 mai 1793 (1794) Jean-Baptiste Louvet reported that, while on the run from the authorities after the insurrection of May 31, the less than forty years old Pétion already had a white hair and beard. This is confirmed by Frédéric Vaultier, who in Souvenirs de l'insurrection Normande, dite du Fédéralisme, en 1793 (1858) described Pétion during the same period as ”a good-looking man, with a calm and open physiognomy and beautiful white hair,” as well as by the examination of his mangled courpse on June 26 1794, which states he had ”grayish hair” (cited in Charlotte de Corday et les Girondins: pièces classées et annotées (1872) by Charles Vatel, volume 2, page 154.

François Buzot — according to the memoirs (1793) of Manon Roland, he had ”a noble figure and elegant size.” In the examination made of Buzot’s body after the suicide there is to read that he had black hair (cited in Charlotte de Corday et les Girondins: pièces classées et annotées (1872) by Charles Vatel, volume 2, page 153)

Charles Barbaroux — his son wrote in Jeunesse de Barbaroux (1822) that ”nature had richly endowed Barbaroux; a robust and large body; a charming, fine and witty physiognomy.” In 1867, François Laprade, who had witnessed Barbaroux’ execution as a thirteen year old, recollected that ”he was a brown man - that is to say he had brownish skin, black hair and beard, reclining figure” (cited in Charlotte de Corday et les Girondins: pièces classées et annotées, volume 3, page 728)

Marguerite-Élie Guadet — According to his passport (cited in Charlotte de Corday et les Girondins: pièces classées et annotées, volume 3, page 672): ”height of 5 pieds, 5 pouces (176 cm) middle sized mouth, black hair and eyebrows, ordinary chin, blue eyes, big forehead, thin face, upturned nose.” According to Frédéric Vaultier’s Souvenirs de l'insurrection Normande, dite du Fédéralisme, en 1793(1858), ”Guadet was a man of fine height, meagre, brown, bilious complexion, black beard, most expressive face.”

Joseph Le Bon — his passport description (cited in Louis Jacob, Joseph Le Bon, (1932) by Louis Jacob, volume 1, page 63) gives the following information: ”Height of five pieds six pouces (178 cm), light brown hair and eyebrows, high forehead, average nose, blue eyes, medium-sized mouth, smallpox scars.”

Claire Lacombe — the concierge of the Sainte Pélagie documented the following about the imprisoned Lacombe: ”height of 5 pieds, 2 pouces (168 cm). Brown hair, eyebrows and eyes, medium nose, large mouth, round face and chin, plain forehead” (cited in Trois femmes de la Révolution : Olymps de Gouges, Théroigne de Méricourt, Rose Lacombe (1900) by Léopold Lacour)

Charlotte Corday — according to her passport, ”height of five pieds one pouce (165 cm), brown hair and eyebrows, gray eyes, high forehead, long nose, medium mouth, round, forked (fourchu) chin, oval face.” (cited in Dossiers du procès criminel de Charlotte Corday, devant le Tribunal révolutionnaire(1861) by Charles-Joseph Vatel, page 55)

Prieur de la Marne — a passport dated October 1 1793 gives the following details: ”age of 37 years, height of 5 pieds 5 pouces (176 cm), blondish brown hair and eyebrows, receding hairline, long nose, grey eyes, large mouth.”

Maurice Duplay — ”height of 5 pieds 6 pouces (179 cm), blondish brown hair and eyebrows, receding hairline, grey eyes, long, open nose, large mouth, round, full chin and face.” Descriptions given in 1795 and cited in Les deniers montagnards (1874) by Jules Claretie.

Jean Lambert Tallien — Both a spy report written in 1794 found among Robespierre’s papers and Mme de la Tour du Pin, a noblewoman who met Tallien in late 1793, describe Tallien’s hair as blonde. Mme de la Tour du Pin adds that said hair was curly and that he had a pretty face.

#round 2!#frev#fouché#théroigne de méricourt#philippe le bas#élisabeth le bas#carnot#mirabeau#billaud varenne#carrier#manon roland#jean marie roland#olympe de gouges#couthon#paul barras#included vilate only in case anyone ever wants to make a super detailed dramatization of camille throwing himself in his arms#following the girondins getting sentenced to death#or robespierre smashing a plate in front of him

296 notes

·

View notes

Text

Psaume 139

Dieu comprend nos prières 26/10/2024

Car la parole n’est pas sur ma langue, que déjà, ô Éternel ! Tu la connais entièrement. Psaume 139.4

Un dimanche matin, alors qu’un jeune garçon était dans les champs près du village, le son des cloches retentit pour appeler les villageois à l’office. Bientôt il distingua, entre les buissons, des groupes de personnes qui se dirigeaient vers l’église. Il lui vint alors l’envie soudaine de prier Dieu pour qu’il le rende bon. Mais personne ne lui avait jamais appris à prier. Il réfléchit un instant, puis s’agenouilla dans l’herbe en joignant les mains comme il l’avait vu sur des gravures naïves et commença à réciter l’alphabet : A, B, C, D…

À ce moment, un retardataire qui se rendait à l’église entendit distinctement la récitation de tout l’alphabet derrière la haie. Il appela l’enfant : « Que fais-tu donc, l’ami ? » Le garçon répondit : « Je dis ma prière, Monsieur. » « Mais pourquoi répètes-tu l’alphabet ? » L’enfant reprit : « Je ne sais pas prier, mais je désire demander à Dieu de prendre soin de moi. Alors j’ai pensé que si je lui disais tout ce que je savais, il saurait bien mettre les lettres ensemble et me comprendre… »

« Il le fera, sois en sûr, car Dieu connaît nos besoins avant que nous lui demandions ! » Puis le brave homme s’assit à côté de l’enfant et il lui apprit comment, tout simplement, chacun peut parler à Dieu révélé en Jésus-Christ, lui demander pardon et le recevoir comme son Sauveur.

Jean-Louis Gaillard

__________________ Lecture proposée : Évangile selon Matthieu, chapitre 6, versets 7 à 15.

7 En priant, ne multipliez pas de vaines paroles, comme les païens, qui s'imaginent qu'à force de paroles ils seront exaucés.

8 Ne leur ressemblez pas; car votre Père sait de quoi vous avez besoin, avant que vous le lui demandiez.

9 Voici donc comment vous devez prier: Notre Père qui es aux cieux! Que ton nom soit sanctifié;

10 que ton règne vienne; que ta volonté soit faite sur la terre comme au ciel.

11 Donne-nous aujourd'hui notre pain quotidien;

12 pardonne-nous nos offenses, comme nous aussi nous pardonnons à ceux qui nous ont offensés;

13 ne nous induis pas en tentation, mais délivre-nous du malin. Car c'est à toi qu'appartiennent, dans tous les siècles, le règne, la puissance et la gloire. Amen!

14 Si vous pardonnez aux hommes leurs offenses, votre Père céleste vous pardonnera aussi;

15 mais si vous ne pardonnez pas aux hommes, votre Père ne vous pardonnera pas non plus vos offenses.

0 notes

Text

NYC - Berlin Sept 2023

Boros Collection --> Jean-Marie Appriou, Julian Charrière, Eliza Douglas, Thomas Eggerer, Louis Fratino, Cyprien Gaillard, Ximena Garrido-Lecca, Yngve Holen, Klára Hosnedlová, Anne Imhof, Alicja Kwade, Victor Man, Kris Martin, Nick Mauss, Jonathan Monk, Adrian Morris, Paulo Nazareth, Berenice Olmedo, Amalia Pica, Bunny Rogers, Michael Sailstorfer, Wilhelm Sasnal, Pieter Schoolwerth, Anna Uddenberg, Julius von Bismarck, Eric Wesley, He Xiangyu

1 note

·

View note

Audio

(Jean-Louis Gaillard) Profiter de la victoire

En 245 avant Jésus-Christ, Hannibal, le célèbre général et homme d'État de Carthage (Afrique du Nord), partit d'Espagne, franchit les Pyrénées, traversa le Rhône, malgré l'opposition de l'armée romaine, passa les Alpes avec ses cavaliers et ses vingt-et-un éléphants, au début de l'hiver, puis il descendit en l'Italie, toujours en engageant le combat.

Finalement, il surprit les Romains en traversant des marais infranchissables et leur infligea, à un contre deux, une terrible défaite. Un de ses officiers, s'étonnant du fait qu'il ne marchait pas sur Rome, lui dit : « Tu sais vaincre, ô Hannibal, mais tu ne sais pas profiter de la victoire ! »

N'est-ce pas là le drame de tant de chrétiens ? Ils ne savent pas profiter de la victoire...de Jésus. Ils vivent dans une médiocrité spirituelle, sont ébranlés dans leur foi dès que survient une épreuve et ne savent pas mettre à profit les promesses de victoire contenues dans la Bible :

Grâces soient rendues à Dieu qui nous donne la victoire par notre Seigneur Jésus-Christ, 1 Corinthiens 15 : 57.

Grâces soient rendues à Dieu, qui nous fait toujours triompher en Christ, 2 Corinthiens 2 : 14.

Ils l'ont vaincu à cause du sang de l'Agneau et à cause de la parole de leur témoignage, Apocalypse 12 : 11.

Jésus est vainqueur, et, par lui, nous sommes plus que vainqueurs !

#SoundCloud#music#Jean-Louis Gaillard#Spoken & Audio#profiter#victoire#Hannibal#général#Pyrénés#rhone#éléphant#hiver#descendre#combat#suspendre#Romain#marais#infranchissable#officier#drame#chrétien

2 notes

·

View notes

Audio

Venez à moi, vous tous qui êtes fatigués et chargés, Matthieu 11 : 28.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Maxim’s

Au numéro 3 de la rue Royale, entre Concorde et Madeleine, se trouve accolé à l'Hôtel de Coislin un immeuble en pierre de taille, construit en 1770 par l'architecte Etienne-Louis Boullée, lors de l'élévation de la rue. Il s'agit aujourd'hui de l'entrée principale de "Maxim's", un temps considéré comme le restaurant le plus célèbre du monde.

D'abord un hôtel particulier, dit de Richelieu, le duc y ayant vécu. Le rez-de-chaussée accueille un glacier italien à la fin des années 1880, puis un bistrot-relais pour cochers de fiacre. Il devient café-glacier en 1893, après son rachat par Maxime Gaillard et son ami Georges Everaert, à l'enseigne de "Maxim's & Georg's", selon l'usage de la Belle Époque d'angliciser les noms des tenanciers (cf. Le Fouquet's). Inspiré par son expérience de barman au "Reynolds" voisin, Maxime dote l'établissement d'un bar américain. Après le départ de Georges, le café prend finalement le nom de "Maxim's". Attirant une jeunesse dorée assidue aux champs de courses, Maxime Gaillard s'endête considérablement (sa clientèle mondaine "oubliant" très souvent de régler son ardoise), jusqu'à se suicider en 1895, à l'âge de 33 ans, léguant son bien à son maître d'hôtel Eugène Cornuché. Celui-ci lance alors de grands travaux, faisant appel aux artistes en vogue de l'École de Nancy, souhaitant adapter le café à la mode éphémère de l'Art nouveau, en vue de l'Exposition universelle de 1900 approchant. La devanture et la salle sont alors transformés, le café devient un restaurant, adjoignant un piano au bar et des "chambres d'amour" à l'étage, avec courtisanes à résidence, comme la Belle Otéro... Le bouche à oreille est fulgurant : on s'y presse tant pour sa cuisine que pour sa décoration, pour son atmosphère et pour sa fréquentation... S'y mêlent grands bourgeois et têtes couronnées, artistes renommés et nouveaux fortunés. La salle verra passer Édouard VII, Marcel Proust, Mistinguett, Jean Bugatti, Sacha Guitry, Jean Cocteau... dont l'ami Octave Vaudable, restaurateur auvergnat, rachète le lieu en 1932, imposant le port de l'habit et favorisant une clientèle "select", bien souvent d'habitués. Sous l'Occupation, il devient le restaurant privilégié des officiers allemands... Après-guerre, de nombreuses stars du cinéma ou de la musique s'y côtoient, Marlène Dietrich croise Martine Carol, Maria Callas y dîne souvent avec son amant Aristote Onassis. Dans les années 50 à 70, le fils d'Octave Vaudable, Louis, donne à Maxim's ses lettres de noblesse, étoffant gastronomiquement son menu, ainsi que ses prix... De nombreuses créations culinaires furent intégrées à la carte, comme la crêpe Veuve Joyeuse, la selle d'agneau Belle Otéro, le soufflé Rothschild... Aller dîner chez Maxim's devient alors un passage obligé pour tout riche touriste de passage à Paris, le chic ultime, le nec plus ultra. Maxim's est synonyme de superlatif. En 1977, Louis Vaudable et sa femme Magguy, ancienne journaliste assurant la communication de l'établissement, s'associent avec le couturier Pierre Cardin, créant la "griffe" Maxim's, se déclinant depuis en produits de luxe, arts de la table, linge de maison, vêtements et autre produits dérivés... désormais vendus à la boutique attenante. François Vaudable, le fils de Louis, vend l'affaire à Pierre Cardin en 1981. L'homme d'affaires ouvre alors sept autres restaurants Maxim's de par le monde, de Bruxelles à Tokyo, celui-ci devenant alors le "Maxim's de Paris". Un Musée Maxim's y est ouvert, couvrant les trois étages surplombant le restaurant, étalant sur plus de 350m2, en des appartements reconstitués dans leur état 1900, la plus grande collection française privée d'Art nouveau, avec des oeuvres, objets d'art et mobilier attribués à de grands noms tels que Toulouse-Lautrec, Sem, Louis Majorelle, Emile Gallé, Hector Guimard, Tiffany & Co... Maxim's fut également un grand lieu d'inspiration pour de nombreuses plumes, au fil des décennies, de La Dame de chez Maxim, le célèbre vaudeville de Georges Feydeau, au Chasseur de chez Maxim's, le film de Claude Vital avec Claude Gensac et Michel Galabru, en passant par la chanson Maxim's, composée par Serge Gainsbourg et chantée par Serge Reggiani, mais aussi le sketch de Popeck, Le diner chez Maxim's, fixant dans l'imaginaire populaire le fantasme du restaurant de luxe, inabordable et inaccessible, mais ô combien désirable. Désir d'ailleurs mis en scène dans de nombreux films, comme Gigi, de Vincente Minnelli, Chéri, de Stephen Frears, ou encore Minuit à Paris, de Woody Allen.

La salle principale du restaurant, comme figée dans le temps, nous offre une riche décoration de fresques murales marouflées, placages d'acajou, miroirs biseautés, ornements de cuivre et de bronze représentant volutes et entrelacs végétaux... Tout concorde à une représentativité absolue de l'Art nouveau, jusqu'à cette magnifique verrière sommitale, décorée de feuillages et floraisons, comme d'un éternel printemps, celui de la Belle Epoque. Lors du remplacement des fameuses banquettes rouges, à la fin des années 50, les ouvriers font la découverte, entre le dossier et l'assise, de nombreux louis d'or, bijoux, diamants, saphirs, rubis... Un véritable trésor, égaré par les nonchalantes précieuses élégantes du début du siècle, insoucieuses de ces pertes, car remplacées par de nouveaux présents de prétendants dès le lendemain... Une certaine idée du luxe.

Nous remercions spécialement Pierre Pelegry de nous avoir permis d’entrer dans cette institution afin d’avoir photographié cette magnifique salle.

Crédits : ALM’s

#monument#restaurant#café#glacier#american bar#Maxim's#Maxime Gaillard#Etienne Louis-Boulée#belle époque#art nouveau#1900#rue Royale#Paris#8ème#belle Otéro#luxe#gastronomie#Vaudable#Pierre Cardin#Jean Cocteau#Maria Callas#select#menu#musée#trésor#salle#verrière#photography#photo#phototoftheday

29 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Roger Carel en bonne compagnie

Roger Henri Élie Bancharel dit Roger Carel (1927-2020)

#photo#RIP#roger carel#roger dumas#jean louis trintignant#jean rochefort#Jacques Dufilho#michel galabru#jacqueline maillan#andré gaillard#pierre tornade#michel serrault#benny hill#gérard hernandez#kermit#kermit la grenouille#kermit the frog

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

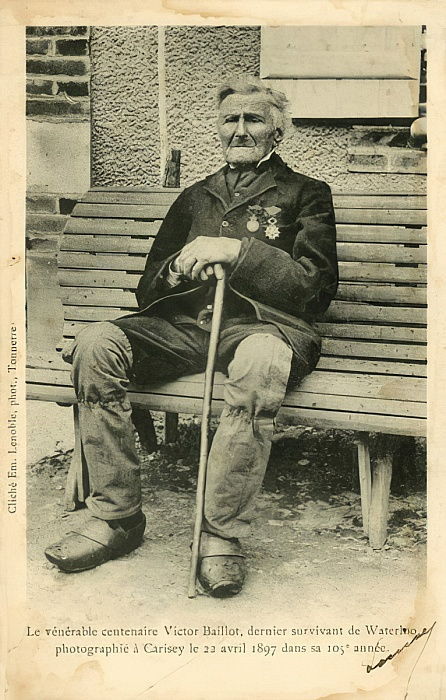

Louis Victor Baillot,le dernier de Waterloo

Chaque jour, les habitants de Carisey (1), dans le département de l’Yonne, voyaient passer dans leurs rues, presque aux mêmes heures, un brave gaillard qu’ils saluaient respectueusement et amicalement. De grande taille, très droit malgré son grand âge, marchant encore d’un pas alerte et militaire, tenant dans la main une canne avec laquelle, parfois, il décrivait d’impressionnants moulinets, revêtu d’une ample redingote sombre, taillée dans ce drap inusable des manteaux d’infanterie d’autrefois, à la boutonnière, deux larges carrés de rubans :un rouge, indiquant la légion d’honneur, un autre à raie rouges et vertes, celui de la médaille de Sainte-Hélène ; le visage balafré d’une large cicatrice qui lui zébrait le front et le crâne. Menant une vie simple et tranquille comme fût celle des populations rurales de cette époque, il gardait religieusement dans ses pensées le souvenir de l’empereur et resta jusqu’à l’aube de notre siècle le vivant témoignage de la grande épopée impériale. Cet homme se nommait Louis Victor Baillot, né à Percey, le 9 Avril 1793. L’histoire de Louis Victor Baillot commence, en juillet 1812, lorsque faisant partie de la seconde levée en masse, il fut dirigé au dépôt de Neuf-Brisach, en Alsace où il fut incorporé au 3e bataillon de la 105e demi-brigade (?) d’infanterie de ligne. A peine équipé, le bataillon quitte Neuf-Brisach pour Mayence et cantonne pendant deux mois à Erfurt avant de rejoindre au printemps, sur la Vistule, les débris de la Grande Armée. Louis Victor Baillot reçoit le baptême du feu à Wittenberg, le 17 avril 1813 et assiste aux opérations militaires qui eurent lieu dans le Mecklemboug, soutint, de septembre 1813 à août 1814, sous les ordres du maréchal Davout, duc d’Auerstaedt, prince d’Eckmühl, le long et honorable siège de Hambourg. Revenu en France, licencié par les Bourbons, le 13 août 1814, Louis Victor Baillot est rappelé en avril 1815. Réintégré dans le 105e régiment d’infanterie de ligne et employé à l’armée du Nord, il fait mouvement vers la Belgique. Le 14 juin 1815, à Beaumont, Napoléon, contraint d’entrer de nouveau en campagne, appelle au dévouement de l’armée et galvanise les énergies. Louis Victor Baillot, qui assiste à la proclamation, voit l’empereur pour la première fois. Venant de Marchiennes puis de Gosselies, le 105e se porte le 16 juin, aux Quatre Bras où la position vient d’être enlevée par le maréchal Ney. Le 17 juin 1815, le ciel couvert de sombres nuages, laissa éclater un orage d’une violence inouïe. Malgré la pluie diluvienne, les canonnades et les charges se poursuivaient sans arrêt. La plaine devint bientôt un immense bourbier. Louis Victor Baillot s’enfonçait dans la boue jusqu’aux genoux. A la tombée de la nuit, il parvint difficilement sur le plateau du Mont St Jean. Obligé de camper sur les seigles mouillés, dans l’impossibilité d’allumer un feu sur le terrain détrempé, il dut se contenter des maigres provisions dont il disposait et passa la nuit dans des conditions très pénibles. Le 18 juin, la pluie ayant cessé de tomber, peu à peu, la ligne des combattants est éclairée par le soleil. A 11 heures et demie, de son observatoire de Rossomme, l’empereur ordonne l’ouverture du feu. Le 105e, placé en seconde ligne, avance avec succès, malgré le feu meurtrier de l’ennemi et enlève à la baïonnette une position tenue par les anglais. Mais, quelques instants après, les écossais couchés dans les blés se levèrent et tirèrent à bout portant sur les français, lesquels surpris par cette attaque imprévisible durent reculer. Se ressaisissant, les hommes du 105e, s’avancent à nouveau, lorsque soudain, surgissent les redoutables dragons gris écossais lancés par Wellington . La charge, d’une rare violence, fauche des rangs entiers. Louis Victor reçoit un violent coup de sabre sur la tête, mais grâce à sa gamelle déposée sous sa coiffure, il échappe miraculeusement à la mort. Blessé d’une large plaie, assommé et couvert de sang, il est laissé pour mort sur le champ de bataille. Ramassé par les anglais, le lendemain, il sera emmené en captivité sur les pontons de Plymouth. Libéré à la fin de1816, il débarque à Boulogne-sur-Mer, rejoint Auxerre à pied, où il est réformé comme phtisique au deuxième degré. Chassé par son père, refoulé par sa mère et son frère, effrayés de voir surgir un revenant, il devra insister encore longtemps pour convaincre sa famille qu’il est vivant. Plus tard, il évoquera avec passion ses campagnes napoléoniennes. Louis Victor raffolait de musique et de parade militaire. Pendant longtemps, il ne manqua jamais une occasion d’assister au défilé annuel de la garnison d’Auxerre, où s’était fixée sa fille, épouse du maréchal des logis de gendarmerie Charles Jolly. Il ne tarda pas à constater que l’infanterie n’était plus celle de son époque. Le pantalon garance avait fait son apparition en 1829, la tunique bleu foncé avait remplacé l’habit ; on portait le shako;le fusil Gribeauval « modèle 1777 », encore en service aux Cent-Jours, avait été, hélas, remplacé par le fusil « Chassepot ». Mr Grolleron, de Seignelay(Yonne ),peintre militaire, s’est vu le soin de faire un portrait de Baillot, en avril 1897. Louis Victor est décédé à Carisey dans la maison habitée aujourd’hui par Mr Gilbert Kerne, ancien maire, le 3 Février 1898, à 2 heures du matin. Il était alors âgé de 104 ans, 9 mois et 24 jours . Sa longue existence qui avait commencée 2 mois et 19 jours après la mort de Louis XVI, et en a fait un témoin des plus nombreux changements de l’histoire de France, s’est terminée à la troisième année du mandat de Félix Faure, sixième Président de la république française. Au cours de cette froide matinée du 5 février 1898, une foule innombrable était rassemblée autour du maire, Mr Alexandre Millot, et les personnalités du département, venus rendre hommage au dernier survivant de la morne plaine. Photographié peu de temps avant, le vénérable vieillard hante paisiblement la salle du conseil de la mairie de Carisey. Son doux sourire comme un regret brisé ressurgit, laissant place aux souvenirs de la saga révolutionnaire et impériale qui enfièvrent notre imagination et suscitent sympathie et admiration. Alors sortent des brumes du passé ces vieux soldats, ces hommes de bronze qui revivent un instant avant d’aller flotter à la dérive du temps, tandis que parvient l’écho de leurs vivats, le cri répété des victoires et des mourants sous l’aigle agonisant de : « Vive l’Empereur

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Bust of Louis XV, Chantilly Factory, 1745-1750, Minneapolis Institute of Art: Decorative Arts, Textiles and Sculpture

Louis XV was the reigning king of France when Jean Gaillard de la Bouëxière owned the Grand Salon. Portrait busts of the king were popular. This one is probably modeled after a bronze statue by Jean-Baptiste Lemoyne, the official sculptor of Louis XV. The king is shown in armor, and the base is decorated with a sculpted military trophy. Size: 17 3/4 x 6 3/4 x 5 3/4 in. (45.09 x 17.15 x 14.61 cm) Medium: Soft paste porcelain

https://collections.artsmia.org/art/10196/

1 note

·

View note

Text

Expériences d'installations d'églises par le pasteur Jean Louis Gaillard

youtube

0 notes

Text

Wednesday Jazz 8/12

Double feature again, first off was a TLG set at Nat’s jazz. Look out for that Yellow Submarine cover by Willy Chirino. He’s a modern day Desi Arnaz complete with his own nightclub in Miami, and his music is an addictive mash up of jazz, Cuban, Miami, and hip hop influences.

Sphynx was next with part two of my Dinner and Drinks set, and quite honestly it was the better half. Giggles.

Sphynx: Dinner and Drinks Pt. 2

Nat King Cole - Riffin' at the Bar-B-Q - 1939, Davis & Schwegler transcription Stan Kenton - Peanut Vendor James Brown - Mashed Potatoes '66 - Instrumental Louis Jordan & His Tympany Five - Beans And Cornbread Ella Fitzgerald - Tea For Two Julie London - Hot Toddy - Remastered Nat King Cole Trio - Bring Another Drink - Remastered 1997 The J.B.'s - Pass The Peas Diana Krall - Frim Fram Sauce Dave Pike - Sweet Tater Pie Slim Gaillard - Potato Chips Booker T. & the M.G.'s - My Sweet Potato Louis Armstrong - Struttin' With Some Barbecue The Two Man Gentlemen Band - Tikka Masala Frank Sinatra - The Coffee Song Gene Krupa & His Orchestra - Lyonaise Potatoes And Some Pork Chops Pérez Prado - Cherry Pink And Apple Blossom White Phil Collins - Chips & Salsa - Live; 2019 Remaster

Nat’s Jazz TLG:

Count Basie Orchestra - 16 Men Swinging Cory Wong - Winslow US Air Force Airmen Of Note - No, I Don't Fly Planes Glenn Miller - (I've Got a Gal in) Kalamazoo The Andrews Sisters - (Get Your Kicks On) Route 66 Betty Carter - Frenesi - Remastered Count Basie Orchestra - Get Me to the Church on Time Robbie Williams - 16 Tons The Fearless Flyers - Adrienne and Adrianne Juanjo Dominguez - All My Loving The Lost Fingers - Groove Is in the Heart The Andrews Sisters - Beat Me Daddy Eight to the Bar Emilie-Claire Barlow - Les yeux ouverts (dream a little dream of me) Count Basie Orchestra - Close Your Eyes Willy Chirino - Yellow Submarine Louis Prima Jr. - Goody Two Shoes Wes Montgomery - California Dreaming The Lost Fingers - Billie Jean Phil Collins - Chips & Salsa - Live; 2019 Remaster Ray Charles - In a Little Spanish Town - Live at Newport Jazz Festival, Rhode Island, 7/5/1958 Olivia Keast - Crazy Johnny Mercer - On The Atchison, Topeka & The Sante Fe Aaron Tesser & The New Jazz Affair - Ride Like The Wind Tino Contreras - Brazil - Remastered Ely Bruna - Material Girl J.Geils - Good Quenn Bess (Feat. Billy Novick) Jeroen Van Der Boom - Don't Stop Me Now Boney James - Tick Tock Dean Martin - King of the Road Robyn Adele Anderson - Gasolina Arcoiris - Horse with No Name Nils Landgren - Lady Madonna Stan Kenton - I Love Paris - Remastered

1 note

·

View note

Photo

[TASK 150: HAITI]