#included vilate only in case anyone ever wants to make a super detailed dramatization of camille throwing himself in his arms

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

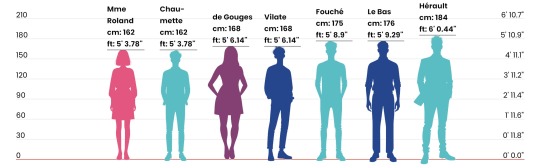

Philippe Le Bas — two passports from the year 1792 have been conserved, the first one stating ”height of five pieds five pouces (176 cm), brown (châtain) hair and eyebrows, gray-blue eyes, short and a bit snub nose, small mouth, round chin, big forehead, ovale face,” the other ”height of five pieds five pouces, brown hair and eyebrows, gray eyes, enlarged nose, middle sized mouth, long chin, ovale face, high forehead.” Cited in Le conventionnel Le Bas: d'après des documents inédits et les mémoires de sa veuve (1901) by Stéfane-Pol, page 26-27.

Élisabeth Le Bas — in Histoire de Robespierre et du coup d’état du 9 thermidor (1865) the historian Ernest Hamel describes Élisabeth in 1794 as ”one of the most charming blondes one could see.” Hamel is confirmed to have met Élisabeth’s son Philippe, but it is less clear if he also met Élisabeth herself. She had dark eyes according to Alphonse Esquiros, who on the other hand is confirmed to have met Élisabeth in her old age.

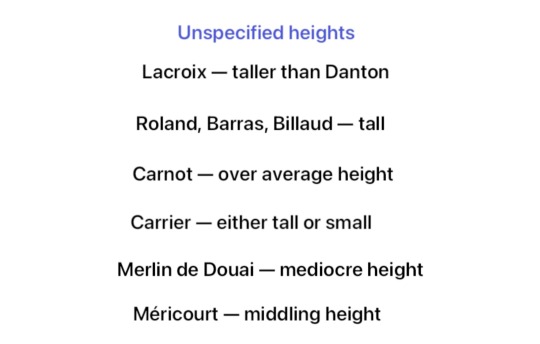

Lazare Carnot — According to Mémoires de Larevellière-Lépeaux: membre du Directoire executif de la République Française et de l'Institut national (1895) ”Carnot is of a height above mediocre. He’s not all that large, but his limbs are and indicate a strong frame; his face, quite well shaped, is slightly marked with smallpoxes. He has a big nose, small water-colored eyes; his hair is blond, thinning, and his forehead is bald; his complexion, a bland white one, does not offer any ruddy shade when he is calm. This pale color, combined with a dry and cunning look, gives him a false and cruel appearance, which repels at first and banishes confidence.”

Georges Couthon — Several contemporaries agree that Couthon looked cute. Pierre Paganel claimed in that he possessed ”a gentle look, a laughing mouth, a countenance which solicited tender affections and promised kindness. His eyes caressed you; his silence attracted you; each of his features expressed a kind feeling and invited you to love him. […] If you imagine this head which seemed to have been composed with a singular predilection, sadly leaning over a body half consumed by premature paralysis; if you consider that his look, marked with habitual pain, in some way accused Providence of having taken away his youth, by taking away the means to spend it happily, you have a fair idea of the keen interest that Couthon inspired in every sensitive man who saw him for the first time.” Barante, an enemy of Couthon, said that his face was ”gentle and pleasant,” his complexion ”dull,” features ”fine and firm,” his look ”gentle and passionate,” and his voice ”persuasive and emotional.” (cited in Georges Couthon (1983) by Albert Soboul). Maurice Gaillard, who met Couthon in May 1794, described his face as ”truly angelic” in a note written to Fouché somewhere during his time as Minister of Police, and in Souvernirs d’un sexagénarie (1833), Antoine Vincent Arnault called him ”the sweet Couthon,” even while describing his execution. In a letter dated September 29 1791 Couthon writes that he’s able to walk to the Legislative Assembly on foot. A year later, September 1792, he was however unable to use his legs and had to be carried, according to the testimony of Jacques-Antoine Dulaure (1794). When exactly Couthon got himself a wheelchair to get around appears to be unknown.

Hérault de Séchelles — A passport dated October 28 1793 documents the following: ”height of 5 pieds 8 pouces (184 cm), brown hair and eyebrows, high forehead, medium sized nose, brown eyes, small mouth” (cited in Un épicurien sous la Terreur; Hérault de Séchelles (1759-1794); d'après des documents inédits (1907) by Emile Dard). In Mémoires sur les règnes de Louis XV et Louis XVI et sur la revolution (1886) Jean-Nicolas Dufort de Cheverny describes Hérault in early 1792 as ”big, well formed, with the most beautiful face possible,” and specifies in a footnote that Hérault ”was one of the most beautiful men in France.” Madame Roland too mentions that Hérault was good looking in her memoirs, noting that ”all these pretty boys seem to me to be poor patriots.” Hérault’s lover Suzanne Giroux de Morency wrote in Illyrine, ou l'écueil de l'inexpérience (1800) that Hérault was ”a beautiful man” and described his eyes as ”big” and ”superb.”

Pierre Gaspard Chaumette — a passport from 1784 states the following: ”height of five pieds, blond hair and eyebrows, blue eyes, a small hole under the left eye, somewhat large nose.” Cited in Mémoires de Chaumette sur la Révolution du 10 août 1792 (1893). According to Pierre Paganel, ”Chaumette was small, his waist thick and squat, his face broad and flat; he looked humble, his eyes were shy and delicate, and his countenance, if I may put it that way, was tearful. He possessed to the supreme degree the silent game of hypocrisy. Through modest and dreamy language one perceived a very resolute character. Long black [sic!] hair, coarse clothing, a more than slovenly outfit, hid a deep ambition from being seen.”

Paul Barras — According to Mémoires de Larevellière-Lépeaux: membre du Directoire executif de la République Française et de l'Institut national (1895) ”He was tall, strong, vigorous and very well built. He had quite handsome features, and was overall a very handsome man; but he looked harsh, his countenance was gloomy, his look sinister; serenity rarely appeared on his face. When he smiled, his smile, gracious in itself, resembled those rays of sunlight escaping through dark clouds which soon intercept them. He had a bad tone in society, and lacked distinction. He had neither that which comes from a noble soul and an elevated spirit, nor that which a careful education and association with good company gives. With a fine figure and a masculine face, he had no external dignity, and always retained something of that common and bold air that bad society gives.”

Sophie Momoro — Jean-Baptiste Laboureau, who met Sophie while they were both imprisoned in the Prison de Port-libre, wrote in his diary on March 19 1794 that she ”is very mundane; passable features, terrible teeth, the voice of a fishwife, an awkward appearance, that's what constitutes Madame Momoro.”

Théroigne de Mericourt — described as being of ”middling height” by former deputy Jacques-Antoine Dulaure in 1823 and psychiatrist Jean-Etienne-Dominique Esquirol in 1838, and ”somewhat above middle size of women” by English visitor John Moore in 1792. Dulaure writes she ”bore on her face the characteristics of vivacity and audacity,” Moore that she ”has a martial air, which in a man would not be disagreeable.” Théroigne was brown according to Dulaure, while Esquirol adds that she had brown (chátain) hair and big blue eyes. Moore describes her costume as ”a kind of English riding habit, but her jacket was the uniform of the national guards,” while Dulaure recalls ”with her blue cloth costume, her hat on her ear, her cane in her hand and sometimes pistols in her pockets, she appeared wherever trouble broke out.” Esquirol, who met Théroigne when she was hospitalized at the Pitié-Salpêtrière claims that she at the time was of ”mobile physiognomy, lively, clear, and even elegant gait.”

Honoré Gabriel Riqueti de Mirabeau — In Les Mirabeau: nouvelles etudes sur la societe francaise au XVIIIe siecle (1891) Louis de Loménie mentions a letter dated 1754, where Mirabeau’s uncle reported to his brother that ”your son is as ugly as Satan’s.” He’s five years old maybe chill a little? An equally unflattering descriptions is given by François René Chateaubriand, who in Mémoires d’Outre-tombe(1860) wrote that Danton was ”inferior in ugliness to Mirabeau,” and similar words can again be found in Mémoires de la Societé d’agriculture, commerce, sciences et arts du department de la Marse, Chalons-sur-Marne (1862): ”With Danton as with Mirabeau, speech was greatly aided by the gaze, the gesture and that energetic ugliness of the face.” In Considerations on the principal events of the French Revolution (1818) Germaine de Staël writes: ”The eye that was once fixed on [Mirabeau’s] countenance was not likely to be soon withdrawn: his immense head of hair distinguished him from amongst the rest, and suggested the idea that, like Samson, his strength depended on it; his countenance derived expression even from its ugliness; and his whole person conveyed the idea of irregular power, but still such power as we should expect to find in a tribune of the people.” A child who had seen Mirabeau during the procession that preceded the opening of the provincial Estates later recalled that he had ”thick hair, brushed up above his broad forehead, and ending in thick curls at the level of the ears” and again that ”there was something imposing about his ugliness.” (cited in Mirabeau(1973) by Antonia Vallentin). Finally, in a letter from 1770, Mirabeau’s uncle writes that ”I found him ugly, but he has not a bad physiognomy: and he has, behind the ravages of the smallpox, and features which are much changed, something graceful, intellectual and noble.” (cited in Mirabeau: A Life-history, in Four Books (1848) by John Stores Smith).

Merlin de Douai — according to Mémoires de Larevellière-Lépeaux : membre du Directoire executif de la République Française et de l'Institut national (1895): ”his size is mediocre; he is thin, dry and gaunt. The thinness of his face makes his large mouth, his big eyes and his long nose stand out rather unfavorably. He is devoid of grace and dignity in his deportment. When one hears him speak for the first time in a somewhat raised tone, one is singularly shocked by the strange character of his voice; it is false, sharp, uneven and has something wild about it.”

Olympe de Gouges — A police description cited on page 35 of Olympe de Gouges (1989) by Oliver Blanc gives the following information: ”height of 1,68 meters, oval face, brown hair and eyebrows, brown eyes, a slightly aquiline nose, an uncovered forehead, a round, full chin, a medium mouth.”

Joseph Fouché — According to Fouché: les silences de la pieuvre (2014) by Emmanuel de Waresquiel, measurements made of Fouché’s skeleton in 1873 show that he was 175 cm tall. He was meagre according to both Philippe-Paul de Ségur (in Mémoires du général comte de Ségur (1894-1895)), Charles Nodier (Souvenirs de la Révolution et de l'Empire (1850)), Mathieu Molé and Victorine de Chastenay (Mémoires de madame de Chastenay, 1771-1815: L'empire. La restauration. Les cent-jours(1897)), who also all agree that there was something piercing about Fouché’s eyes. Said eyes were small according to Chastenay (who also adds that they were very close together) and Ségur. Nodier writes that they were of a light blue colour, while Chastenay calls them ”very red,” and Ségur and Molé ”bloody.” Chastenay, Ségur and Nodier do also each call Fouché pale, the latter even writing that it was ”a particular pallor, which belonged only to him” noting that it was clearly different from someone with anemia or other illness. This, combined with the testimony of Fouché’s ”red eyes,” hint at the idea that he was albino. In his memoirs (1896), Barras does indeed outright call Fouché’s child ”an actual albino,” while Molé writes Fouché had ”the dry hair of an albino.” Speaking of his hair, Ségur writes that it was ”flat and rare” and that Fouché was towheaded (cheveux couleur de filasse). Chastenay too underlines that ”in his youth his hair had been or should have been a very bland blond.” According to Barras, both Fouché and his wife Bonne-Jeanne Coiquaud did however have red hair. According to the memoirs(1834) of Charlotte Robespierre, ”Fouché wasn’t handsome,” and according to those of Barras, Fouché and his wife were a ”hideous couple.” Molé instead writes that he had ”fine features,” and that ”something at once ferocious, elegant and agile makes him resemble a panther.” Ségur on the other hand likened Fouché’s physiognomy to that of ”an agitated weasel” and writes that he had a ”long and mobile” face. Fouché ”spoke with ease” according to Chastenay, had ”a dry voice” according to Molé, and had a ”brief and jerky speech, consistent with his restless and convulsive attitude” according to Ségur.

Manon Roland — In her memoirs, Manon gives the following detailed description of herself: ”At fourteen, like today, I was about five pieds (162 cm) tall; my size had acquired all its growth; the leg well shaped, the foot well placed, the hips very raised, the chest broad, the shoulders effaced, the attitude firm and graceful, the walk rapid and light; this is what first hit the eye. There was nothing striking about my face, only great freshness, a lot of softness and expression. By detailing each of the features, one can ask oneself: Where is the beauty? Nothing is regular, everything pleases. The mouth is a little big; there are a thousand prettier ones; not one has a more tender and seductive smile. The eyes, on the contrary, are not very large, their iris is a grey-chestnut; but placed not very deep in the sockets, with an open, frank, lively and gentle gaze, crowned with brown eyebrows the same colour as the hair, and well defined, they vary in their expression, like the affectionate soul whose movements they paint; serious and proud, they sometimes surprise; but they caress much more, and always wakes you up. My nose was causing me some pain, I found it a little big at the tip; however, I considered that overall, and especially in profile, it did not spoil anything else. The broad, bare forehead, little covered at that age, supported by the very high orbit of the eye, and in the middle of which veins in Greek vanished at the slightest emotion, was far from the the insignificance that one finds on so many faces. As for the fairly upturned chin, it has precisely the characteristics that the physiognomies indicate for those of voluptuousness; when I bring them together with everything that is particular to me, I doubt that anyone was ever more made for it, and enjoyed it less. Bright rather than very white complexion, dazzling colors, frequently enhanced by the sudden redness of boiling blood, excited by the most sensitive nerves; the soft skin, the rounded arm, the pleasant hand, without being small, because its elongated and slender fingers announce skill and retain grace; fresh, tidy teeth; the plumpness of perfect health: such are the treasures that nature had given me. I have lost many, especially those who are plump and fresh; those who remain with me still hide, without me using any art, five to six of my years; and the very people who see me every day need me to tell them my age, to believe that I am over thirty-two or thirty-three. […] My portrait has been drawn several times, painted and engraved: none of these imitations gives the idea of my person; it is difficult to grasp because I have more soul than face, more expression than features. […] Camille Desmoulins was right to be surprised that at my age, and with so little beauty, I had what he calls admirers.” Interestingly though, despite describing herself as only 162 cm tall, Manon gets called tall by both her friend Helen Maria Williams in Memoirs Of The Reign Of Robespierre (1795), as well as by Honoré Riouffe (who claimed to have seen her at the Conciergerie prison) in Mémoires d’un détenu pour servir à l’histoire de la tyrannie de Robespierre(1795).

Jean Marie Roland — in 1792, John Moore described Roland as ”about fifty years of age, tall, thin, of a mild countenance and pale complexion. His drefs, every time I have seen him, has been the same, a drab-coloured suit lined with green silk, his grey hair hanging loose” and that his ”manner is unassuming and modest” in his diary. According to Mémoires du marquis de Ferrières: avec une notice sur sa vie, des notes et des éclaircissemens historiques (1821) ”Roland looked like Plutarch or a Quaker in his Sunday best. Flat hair, little powder, a black coat, shoes with cords instead of buckles, made him look like a rhinoceros. However, he had a decent and pleasant face.”

Charles Alexis Brûlart de Genlis, the marquis de Sillery — in Memoirs Of The Reign Of Robespierre(1795) Helen Maria Williams writes Sillery had white hair by the time of his execution in October 1793.

Jean Baptiste Carrier — According to Pierre Paganel, ”Carrier was taller than the ordinary. He had an unpleasant face, but it was not very sinister.” At the time of his trial, a witness did instead describe him as "small, thick, stocky, he had black, frizzy hair and a swarthy complexion, his enormous, hanging lower lip gave him the vague appearance of a Negro" (cited in Carrier et la Terreur nantaise (1987) by Jean-Joël Brégeon).

Jacques Nicolas Billaud-Varennes — Jacques Bernard, who met Billaud in 1800, wrote that ”he was tall, his broad, pale face did not reveal, by any external sign, a very energetic soul. His countenance was full of gentleness, he wore a wig of red hair, in the Jacobin style. His accent, his manners announced affability and a distinction that his costume, more than simple, could not erase. Trousers, a coarse canvas jacket, a wide-brimmed hat, large shoes, such was the costume of this Spartan.” Cited in Billaud-Varenne, membre du Comité de salut public : mémoires inédits et correspondance / accompagnés de notices biographiques sur Billaud-Varenne et Collot-d'Herbois par Alfred Bégis(1893)

Jean-François Lacroix — According to the memoirs (1913) of Théodore de Lameth, Lacroix was ”of a frightening size and eloquence.” J.G Millingen agrees, writing in his Recollections of Republican France 1791-1801 (1848) that Lacroix was a man of ”colossal stature.” Millingen also attributes the following words to Lacroix, said at the foot of the scaffold: ”Do you see that axe, Danton? Well, even when my head is struck off I shall be taller than you!”

Joachim Vilate — height of 5 pieds, 2 pouces (168 cm), brown (châtains) hair and eyebrows. Descriptions given in 1795 and cited in Les derniers montagnards (1874) by Jules Claretie.

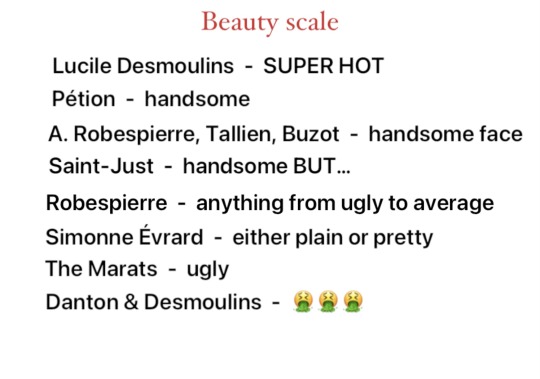

Frev appearance descriptions masterpost

Jean-Paul Marat — In Histoire de la Révolution française: 1789-1796 (1851) Nicolas Villiaumé pins down Marat’s height to four pieds and eight pouces (around 157 cm). This is a somewhat dubious claim considering Villiaumé was born 26 years after Marat’s death and therefore hardly could have measured him himself, but we do know he had had contacts with Marat’s sister Albertine, so maybe there’s still something to this. That Marat was short is however not something Villaumé is alone in claiming. Brissot wrote in his memoirs that he was ”the size of a sapajou,” the pamphlet Bordel patriotique (1791) claimed that he had ”such a sad face, such an unattractive height,” while John Moore in A Journal During a Residence in France, From the Beginning of August, to the Middle of December, 1792 (1793) documented that ”Marat is little man, of a cadaverous complexion, and a countenance exceedingly expressive of his disposition. […] The only artifice he uses in favour of his looks is that of wearing a round hat, so far pulled down before as to hide a great part of his countenance.” In Portrait de Marat (1793) Fabre d’Eglantine left the following very detailed description: ”Marat was short of stature, scarcely five feet high. He was nevertheless of a firm, thick-set figure, without being stout. His shoulders and chest were broad, the lower part of his body thin, thigh short and thick, legs bowed, and strong arms, which he employed with great vigor and grace. Upon a rather short neck he carried a head of a very pronounced character. He had a large and bony face, aquiline nose, flat and slightly depressed, the under part of the nose prominent; the mouth medium-sized and curled at one corner by a frequent contraction; the lips were thin, the forehead large, the eyes of a yellowish grey color, spirited, animated, piercing, clear, naturally soft and ever gracious and with a confident look; the eyebrows thin, the complexion thick and skin withered, chin unshaven, hair brown and neglected. He was accustomed to walk with head erect, straight and thrown back, with a measured stride that kept time with the movement of his hips. His ordinary carriage was with his two arms firmly crossed upon his chest. In speaking in society he always appeared much agitated, and almost invariably ended the expression of a sentiment by a movement of the foot, which he thrust rapidly forward, stamping it at the same time on the ground, and then rising on tiptoe, as though to lift his short stature to the height of his opinion. The tone of his voice was thin, sonorous, slightly hoarse, and of a ringing quality. A defect of the tongue rendered it difficult for him to pronounce clearly the letters c and l, to which he was accustomed to give the sound g. There was no other perceptible peculiarity except a rather heavy manner of utterance; but the beauty of his thought, the fullness of his eloquence, the simplicity of his elocution, and the point of his speeches absolutely effaced the maxillary heaviness. At the tribune, if he rose without obstacle or excitement, he stood with assurance and dignity, his right hand upon his hip, his left arm extended upon the desk in front of him, his head thrown back, turned toward his audience at three-quarters, and a little inclined toward his right shoulder. If on the contrary he had to vanquish at the tribune the shrieking of chicanery and bad faith or the despotism of the president, he awaited the reéstablishment of order in silence and resuming his speech with firmness, he adopted a bold attitude, his arms crossed diagonally upon his chest, his figure bent forward toward the left. His face and his look at such times acquired an almost sardonic character, which was not belied by the cynicism of his speech. He dressed in a careless manner: indeed, his negligence in this respect announced a complete neglect of the conventions of custom and of taste and, one might almost say, gave him an air of ressemblance.”

Albertine Marat — both Alphonse Ésquiros and François-Vincent Raspail who each interviewed Albertine in her old age, as well as Albertine’s obituary (1841) noted a striking similarity in apperance between her and her older brother. Esquiros added that she had ”two black and piercing eyes.” A neighbor of Albertine claimed in 1847 that she had ”the face of a man,” and that she had told her that ”my comrades were never jealous of me, I was too ugly for that” (cited in Marat et ses calomniateurs ou Réfutation de l’Histoire des Girondins de Lamartine (1847) by Constant Hilbe)

Simonne Evrard — An official minute from July 1792, written shortly after Marat’s death, affirmed the following: “Height: 1m, 62, brown hair and eyebrows, ordinary forehead, aquiline nose, brown eyes, large mouth, oval face.” The minute for her interrogation instead says: “grey eyes, average mouth.”Cited in this article by marat-jean-paul.org. When a neighbor was asked whether Simonne was pretty or not around two decades after her death in 1824, she responded that she was ”très-bien” and possessed ”an angelic sweetness” (cited in Marat et ses calomniateurs ou Réfutation de l’Histoire des Girondins de Lamartine (1847) by Constant Hilbe) while Joseph Souberbielle instead claimed that ”she was extremely plain and could never have had any good looks.”

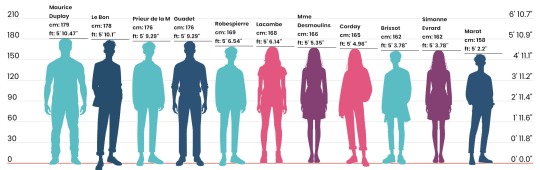

Maximilien Robespierre — The hostile pampleth Vie secrette, politique et curieuse de M. J Maximilien Robespierre… released shortly after thermidor by L. Duperron, specifies Robespierre’s hight to have been ”five pieds and two or three pouces” (between 165 and 170 cm). He gets described as being ”of mediocre hight” by his former teacher Liévin-Bonaventure Proyart in 1795, ”a little below average height” by journalist Galart de Montjoie in 1795, ”of medium hight” by the former Convention deputy Antoine-Claire Thibaudeau in 1830 and ”of middling form” by his sister in 1834, but ”of small size” by John Moore in 1792 and Claude François Beaulieu in 1824. The 1792 pampleth Le véritable portrait de nos législateurs… wrote that Robespierre lacked ”an imposing physique, a body à la Danton,”supported by Joseph Fiévée who described him as ”small and frail” in 1836, and Louis Marie de La Révellière who said he was ”a physically puny man” in his memoirs published 1895. For his face, both François Guérin (on a note written below a sketch in 1791), Buzot in his Mémoires sur la Révolution française (written 1794), Germaine de Staël in her Considerations on the Principal Events of the French Revolution (1818), a foreign visitor by the name of Reichardt in 1792 (cited in Robespierre by J.M Thompson), Beaulieu and La Révellière-Lépeaux all agreed that he had a ”pale complexion.” Charlotte does instead describe it as ”delicate” and writes that Maximilien’s face ”breathed sweetness and goodwill, but it was not as regularly handsome as that of his brother,” while Proyart claims his apperance was ”entirely commonplace.” The foreigner Reichardt wrote Robespierre had ”flattened, almost crushed in, features,” something which Proyart agrees with, writing that his ”very flat features” consisted of ”a rather small head born on broad shoulders, a round face, an indifferent pock-marked complexion, a livid hue [and] a small round nose.” Thibaudeau writes Robespierre had a ”thin face and cold physiognomy, bilious complexion and false look,” Duperron that ”his colouring was livid, bilious; his eyes gloomy and dull,” something which Stanislas Fréron in Notes sur Robespierre (1794) also agrees with, claiming that ”Robespierre was choked with bile. His yellow eyes and complexion showed it.” His eyes were however green according to Merlin de Thionville and Guérin while Proyart insists they were ”pale blue and slightly sunken.” Etienne Dumont, who claimed to have talked to Robespierre twice, wrote in his Souvernirs sur Mirabeau et sur les deux premières assemblées législatives (1832) that ”he had a sinister appearance; he would not look people in the face, and blinked continually and painfully,” and Duperron too insists on ”a frequent flickering of the eyelids.” Both Fréron, Buzot, Merlin de Thionville, La Révellière, Louis Sébastien Mercier in his Le Nouveau Paris (1797) and Beffroy de Reigny in Dictionnaire néologique des hommes et des choses ou notice alphabétique des hommes de la Révolution, qui ont paru à l’Auteur les plus dignes d’attention… (1799) made the peculiar claim that Robespierre’s face was similar to that of a cat. Proyart, Beaulieu and Millingen all wrote that it was marked by smallpox scars, ”mediocretly” according to Proyart, ”deeply” according to the other two. Proyart also writes that Robespierre’s hair was light brown (châtain-blond). He is the only one to have described his hair color as far as I’m aware.

For his clothes, both Montjoie, Louis-Sébastien Mercier in 1801, Helen Maria Williams in 1795, Duperron, Millingen and Fiévée recall the fact that Robespierre wore glasses, the first two claiming he never appeared in public without them, Duperron that he ”almost always” wore them, and Millingen that they were green. Pierre Villiers, who claimed to have served as Robespierre’s secretary in 1790, recalled in Souvenirs d'un deporté (1802) that Robespierre ”was very frugal, fastidiously clean in his clothes, I could almost say in his one coat, which was was of a dark olive colour,” but also that ”He was very poor and had not even proper clothes,” and even had to borrow a suit from a friend at one point. Duperron records that ”[Robespierre’s] clothes were elegant, his hair always neat,” Millingen that ”his dress was careful, and I recollect that he wore a frill and ruffles, that seemed to me of valuable lace,”Charlotte that ”his dress was of an extreme cleanliness without fastidiousness,” Williams that he ”always appeared not only dressed with neatness, but with some degree of elegance, and while he called himself the leader of the sans-culottes, never adopted the costume of his band. His hideous countenance […] was decorated with hair carefully arranged and nicely powdered,” Fiévée that Robespierre in 1793 was ”almost alone in having retained the costume and hairstyle in use before the Revolution,” something which made him ressemble ”a tailor from the Ancien régime,” Thibadeau that ”he was neat in his clothes, and he had kept the powder when no one wore it anymore,” Germaine de Staël that ”he was the only person who wore powder in his hair; his clothes were neat, and his countenance nothing familiar,” Révellière writes that Robespierre’s voice was ”toneless, monotonous and harsh,” Beaulieu that it ”was sharp and shrill, almost always in tune with violence,” and Thinadeau that his ”tone” was ”dogmatic and imperious.”

Augustin Robespierre — described as ”big, well formed, and [with a] face full of nobility and beauty” in the memoirs of his sister Charlotte. Charles Nodier did in Souvenirs, épisodes et portraits pour servir à l'histoire de la Révolution et de l'Empire (1831) recall that Augustin had a ”pale and macerated physiognomy” and a quite monotonous voice.

Charlotte Robespierre — an anonymous doctor who claimed to have run into Charlotte in 1833, the year before her death, described her as ”very thin.” Jules Simon, who reported to have met her the following year, did him too describe her as ”a very thin woman, very upright in her small frame, dressed in the antique style with very puritanical cleanliness.”

Camille Desmoulins — described as ”quite tall, with good shoulders” in number 16 of the hostile journal Chronique du Manège (1790). Described as ugly by both said journal, the journal Journal Général de la Cour et de la Ville in 1791, his friend François Suleau in 1791, former teacher Proyart in 1795, Galart de Montjoie in 1796, Georges Duval in 1841, Amandine Rolland in 1864 (she does however add that it was ”with that witty and animated ugliness that pleases”) and even himself in 1793. Proyart describes his complexion as ”black,” Duval as ”bilious.” Both of them agree in calling his eyes ”sinister.” Duval also claims that Desmoulins’ physiognomy was similar to that of an ospray. Montjoie writes that Desmoulins had ”a difficult pronunciation, a hard voice, no oratorical talent,” Proyart that ”he spoke very heavily and stammered in speech” and Camille himself that he has ”difficulty in pronunciation” in a letter dated March 1787, and confesses ”the feebleness of my voice and my slight oratorical powers” in number 4 of the Vieux Cordelier. In his very last letter to his wife, dated April 1 1794, Desmoulins reveals that he wears glasses.

Lucile Desmoulins — The concierge at the Sainte-Pélagie prison documented the following when Lucille was brought before him on April 4 1794: ”height of five pieds and one and a half pouce (166 cm). Brown hair, eyebrows and eyes. Middle sized nose and mouth. Round face and chin. Ordinary front. A mark above the chin on the right.” Cited in Camille et Lucile Desmoulins: un rêve de république (2018). Described as beautiful by the journal Journal Général de la Cour et de la Ville in 1791 (it specifies her to be ”as pretty as her husband is ugly”), former Convention deputy Pierre Paganel in 1815, Louis Marie Prudhomme in 1830, Amandine Rolland in 1864 and Théodore de Lameth (memoirs published 1913).

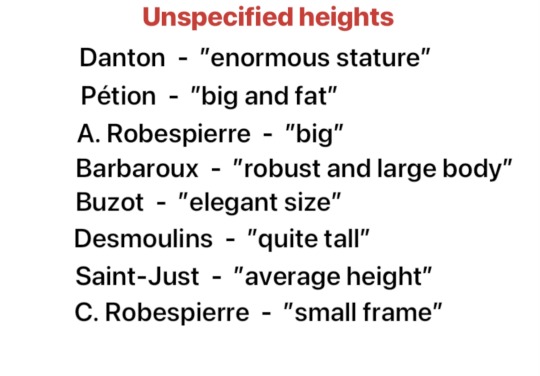

Georges Danton — Described as having an ugly face by both Manon Roland in 1793, Vadier in 1794, the anonymous pamphlet Histoire, caractère de Maximilien Robespierre et anecdotes sur ses successeurs in 1794, Louis-Sébastien Mercier in 1797, Antoine Fantin-Desodoards in 1807, John Gideon Millingen in 1848, Élisabeth Duplay Lebas in the 1840s, the memoirs (1860) of François-René Chateaubriand (he specifies that Danton had ”the face of a gendarme mixed with that of a lustful and cruel prosecutor”) as well as the Mémoires de la Societé d’agriculture, commerce, sciences et arts du department de la Marse, Chalons-sur-Marne (1862). As reason for this ugliness, Millingen lifts his ”course, shaggy hair” (that apparently gave him the apperance of a ”wild beast”), the fact he was deeply marked with small-poxes, and that his eyes were unusually small (”and sparkling in surrounding darkness”), while Chateaubriand instead underlines that he was ”snub-nosed,” with ”windy nostrils [and] seamed flats.” Mercier writes that Danton’s face was ”hideously crushed.” The former Convention deputy Alexandre Rousselin (1774-1847) reported in his Danton — Fragment Historique that Danton developed a lip deformity after getting gored by a bull as a baby, had his nose crushed by another bull, got trampled in the face by a group of pigs and finally survived ”a very serious case of smallpoxes, accompanied by purpura.” In 1792, John Moore reported that ”Danton is not so tall, but much broader than Roland; his form is coarse and uncommonly robust,” while Vadier claims that Danton possessed a ”robust form, colossal eloquence,” the anonymous pamphlet that ”he was very strong, he said himself that he had athletic forms,” Desodoards that he ”held the nature of athletic and colossal forms,” Chateaubriand that he was ”a vandal in the size of Goth” (don’t know who he’s referring to), Pierre Paganel (in Essai historique et critique sur la révolution française: ses causes, ses résultats, avec les portraits des hommes les plus célèbres (1815)) that he was of an ”enormous stature,” while the pamphlet described him as a ”gigantic orator” whose voice ”shook the vaults of the hall.” René Levasseur in 1829, John Moore, Millingen, Paganel and Desodoards all agreed with this, the first four writing that Danton possessed a ”stentorian voice,” the latter that he had ”a very strong voice, without being sonorous or flexible.” In her memoirs (1834) Charlotte Robespierre claims that ”[Danton] did not at all conserve the dignity suited to the representative of a great people in his manners; his toilette was in disorder.”

Louis Antoine Saint-Just — In Saint-Just (1985) Bernard Vinot writes that Saint-Just’s childhood friend Augustin Lejeune recalled his “honest physiognomy,” and that his sister Louise would evoke her brother’s ”great beauty” for her grandchildren (I unfortunately can’t find the original sources here). The elderly Élisabeth Le Bas too stated that ”he was handsome, Saint-Just, with his pensive face, on which one saw the greatest energy, tempered by an air of indefinable gentleness and candor” (testimony found in Les Carnets de David d’Angers (1838-1855) by Pierre-Jean David d’Angers, cited in Veuve de Thermidor: le rôle et l'influence d'Élisabeth Duplay-Le Bas (1772-1859) sur la mémoire et l'historiographie de la Révolution française (2023) by Jolène Audrey Bureau, page 127). In Souvenirs de la révolution et de l’empire, Charles Nodier (who was twelve years old when he met Saint-Just…) agrees in calling him ”handsome,” but adds that he ”was far from offering this graceful combination of cute features with which we have seen it endowed by the euphemistic pencil of a lithograph,” had an ”ample and rather disproportionate chin,” that ”the arc of his eyebrows, instead of rounding into smooth and regular semi-circles, was closer to a straight line, and its interior angles, which were bushy and severe, merged into one another at the slightest serious thought that one saw pass on his forehead” and finally that ”his soft and fleshy lips indicated an almost invincible inclination to laziness and voluptuousness.” How would you know what his lips were like, Nodier. In Essai historique et critique sur la révolution française (1815) Pierre Paganel writes that Saint-Just had ”regular features and austere physiognomy.” He describes his complexion as ”bilious” while Nodier calls it ”pale and grayish, like that of most of the active men of the revolution.” Similar to Élisabeth’s description, Nodier writes that Saint-Just’s eyes were big and ”usually thoughtful,” while Paganel instead writes they were ”small and lively.” Saint-Just was of ”average height” according to Paganel, but ”of small stature” according to Nodier. According to Paganel, Saint-Just had a ”healthy body [and] proportions which expressed strength,” while Saint-Just’s colleague Levasseur de la Sarthe instead wrote in his memoirs that he was ”weak in body, to the point of fearing the whistling of bullets.” Finally, Paganel also gives the following details: ”large head, thick hair, disdainful gaze, strong but veiled voice, a general tinge of anxiety, the dark accent of concern and distrust, an extreme coldness in tone and manners.” In Lettre de Camille Desmoulins, député de Paris à la Convention, August général Dillon en prison aux Madelonettes (1793) Desmoulins jokingly writes that ”one can see by [Saint-Just’s] gait and bearing that he looks upon his own head as the corner-stone of the Revolution, for he carries it upon his shoulders with as much respect and as if it was the Sacred Host.” In Histoire de la Révolution française(1878), Jules Michelet claims that Élisabeth Le Bas had told him that this portrait, depicting Saint-Just as having ”a very low forehead, [with] the top of his head flattened, so that his hair, without being long, almost touched his eyes,” was similar to what he had looked like.

Jacques-Pierre Brissot — The following was documented after Brissot had been arrested at Moulins on June 10 1793 — ”height of five pieds (162 cm), a small amount of flat dark brown hair, eyebrows of the same color, high forehead and receding hairline, gray-brown, quite large and covered eyes, long and not very large nose, average mouth, long chin with a dimple, black beard, oval face narrow at the bottom” (cited in J.-P. Brissot mémoires (1754-1793); [suivi de] correspondance et papiers (1912)). In Journal During a Residence in France, from the Beginning of August, to the Middle of December, 1792 John Moore described Brissot as ”a little man, of an intelligent countenance, but of a weakly frame of body” and claimed that a person had told him that Brissot had told him that he is ”of so feeble a constitution” that he won’t be able to put up any resistance was someone try to assassinate him.

Jérôme Pétion — described as ”big and fat” (grand et gros) by Louis-Philippe in 1850 (cited in The Croker Papers: the Correspondence and Diaries of the late right honourable John Wilson Croker… (1885) volume 3, page 209). Manon Roland wrote in her memoirs that Pétion ”had nothing to regret physically; his size, his face, his gentleness, his urbanity, speak in his favor” as well as that he ”spoke fairly well,” a descriptions which Louis Marie Prudhomme partly agreed with, himself recording that Pétion ”had a proud countenance, a fairly handsome face, an affable look, a gentle eloquence, movements of talent and address; but his manners were composed, his eyes were dull, and he had something glistening in his features which repelled confidence” in Paris pendant le révolution (1789-1798) ou le nouveau Paris (1798). In Quelques notices pour l’histoire, et le récit de mes périls depuis le 31 mai 1793 (1794) Jean-Baptiste Louvet reported that, while on the run from the authorities after the insurrection of May 31, the less than forty years old Pétion already had a white hair and beard. This is confirmed by Frédéric Vaultier, who in Souvenirs de l'insurrection Normande, dite du Fédéralisme, en 1793 (1858) described Pétion during the same period as ”a good-looking man, with a calm and open physiognomy and beautiful white hair,” as well as by the examination of his mangled courpse on June 26 1794, which states he had ”grayish hair” (cited in Charlotte de Corday et les Girondins: pièces classées et annotées (1872) by Charles Vatel, volume 2, page 154.

François Buzot — according to the memoirs (1793) of Manon Roland, he had ”a noble figure and elegant size.” In the examination made of Buzot’s body after the suicide there is to read that he had black hair (cited in Charlotte de Corday et les Girondins: pièces classées et annotées (1872) by Charles Vatel, volume 2, page 153)

Charles Barbaroux — his son wrote in Jeunesse de Barbaroux (1822) that ”nature had richly endowed Barbaroux; a robust and large body; a charming, fine and witty physiognomy.” In 1867, François Laprade, who had witnessed Barbaroux’ execution as a thirteen year old, recollected that ”he was a brown man - that is to say he had brownish skin, black hair and beard, reclining figure” (cited in Charlotte de Corday et les Girondins: pièces classées et annotées, volume 3, page 728)

Marguerite-Élie Guadet — According to his passport (cited in Charlotte de Corday et les Girondins: pièces classées et annotées, volume 3, page 672): ”height of 5 pieds, 5 pouces (176 cm) middle sized mouth, black hair and eyebrows, ordinary chin, blue eyes, big forehead, thin face, upturned nose.” According to Frédéric Vaultier’s Souvenirs de l'insurrection Normande, dite du Fédéralisme, en 1793(1858), ”Guadet was a man of fine height, meagre, brown, bilious complexion, black beard, most expressive face.”

Joseph Le Bon — his passport description (cited in Louis Jacob, Joseph Le Bon, (1932) by Louis Jacob, volume 1, page 63) gives the following information: ”Height of five pieds six pouces (178 cm), light brown hair and eyebrows, high forehead, average nose, blue eyes, medium-sized mouth, smallpox scars.”

Claire Lacombe — the concierge of the Sainte Pélagie documented the following about the imprisoned Lacombe: ”height of 5 pieds, 2 pouces (168 cm). Brown hair, eyebrows and eyes, medium nose, large mouth, round face and chin, plain forehead” (cited in Trois femmes de la Révolution : Olymps de Gouges, Théroigne de Méricourt, Rose Lacombe (1900) by Léopold Lacour)

Charlotte Corday — according to her passport, ”height of five pieds one pouce (165 cm), brown hair and eyebrows, gray eyes, high forehead, long nose, medium mouth, round, forked (fourchu) chin, oval face.” (cited in Dossiers du procès criminel de Charlotte Corday, devant le Tribunal révolutionnaire(1861) by Charles-Joseph Vatel, page 55)

Prieur de la Marne — a passport dated October 1 1793 gives the following details: ”age of 37 years, height of 5 pieds 5 pouces (176 cm), blondish brown hair and eyebrows, receding hairline, long nose, grey eyes, large mouth.”

Maurice Duplay — ”height of 5 pieds 6 pouces (179 cm), blondish brown hair and eyebrows, receding hairline, grey eyes, long, open nose, large mouth, round, full chin and face.” Descriptions given in 1795 and cited in Les deniers montagnards (1874) by Jules Claretie.

Jean Lambert Tallien — Both a spy report written in 1794 found among Robespierre’s papers and Mme de la Tour du Pin, a noblewoman who met Tallien in late 1793, describe Tallien’s hair as blonde. Mme de la Tour du Pin adds that said hair was curly and that he had a pretty face.

#round 2!#frev#fouché#théroigne de méricourt#philippe le bas#élisabeth le bas#carnot#mirabeau#billaud varenne#carrier#manon roland#jean marie roland#olympe de gouges#couthon#paul barras#included vilate only in case anyone ever wants to make a super detailed dramatization of camille throwing himself in his arms#following the girondins getting sentenced to death#or robespierre smashing a plate in front of him

249 notes

·

View notes