#Imported crops in India

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The Curious Case of India's Foreign Vegetables

Discover the surprising origins of popular Indian vegetables and how these exotic eatables worldwide made their way to India, now becoming a staple of Indian cuisine.

#India's foreign vegetables#Imported crops in India#Indian vegetable market trends#Agricultural globalization#Exotic vegetables in India#Foreign vegetables demand#Vegetable import impact#Indian farming and imports#Agricultural trade analysis#Vegetable consumer preferences

0 notes

Photo

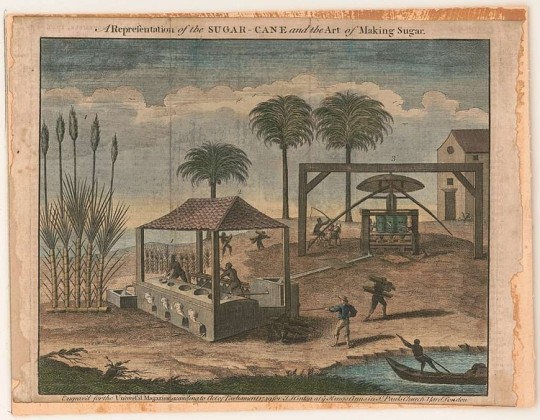

Sugar & the Rise of the Plantation System

From a humble beginning as a sweet treat grown in gardens, sugar cane cultivation became an economic powerhouse, and the growing demand for sugar stimulated the colonization of the New World by European powers, brought slavery to the forefront, and fostered brutal revolutions and wars.

The geographic center of sugar cane cultivation shifted gradually across the world over a span of 3,000 years from India to Persia, along the Mediterranean to the islands near the coast of Africa and then the Americas, before shifting back across the globe to Indonesia. A whole new kind of agriculture was invented to produce sugar – the so-called Plantation System. In it, colonists planted large acreages of single crops which could be shipped long distances and sold at a profit in Europe. To maximize the productivity and profitability of these plantations, slaves or indentured servants were imported to maintain and harvest the labor-intensive crops. Sugar cane was the first to be grown in this system, but many others followed including coffee, cotton, cocoa, tobacco, tea, rubber, and most recently oil palm.

Beginnings of Sugar Cultivation

There is no archeological record of when and where humans first began growing sugar cane as a crop, but it most likely occurred about 10,000 years ago in what is now New Guinea. The species domesticated was Saccharum robustum found in dense stands along rivers. The people in New Guinea were among the most inventive agriculturalists the world has known. They domesticated a broad range of local plant species including not only sugar cane but also taro, bananas, yam, and breadfruit.

The cultivation of sugar cane moved steadily eastward across the Pacific, spreading to the adjacent Solomon Islands, the New Hebrides, New Caledonia, and ultimately to Polynesia. Cultivation of sugar cane also moved westward into continental Asia, Indonesia, the Philippines, and then Northern India. During this advancement, S. officinarum ("nobel canes") hybridized with a local wild species called S. spontaneum to produce a hybrid, S. sinense ("thin canes"). These hybrids were less sweet and not as robust as pure S. officinarum but were hardier and could be grown much more successfully in subtropical mainlands.

Sugar cane was for eons just chewed as a sweet treat, and it was not until about 3,000 years ago that people in India first began squeezing the canes and producing sugar (Gopal, 1964). For a long time, the Indian people kept the whole process of sugar-making a closely guarded secret, resulting in rich profits through trade across the subcontinent. This all changed when Darius I (r. 522-486 BCE), ruler of the Persian Achaemenid Empire, invaded India in 510 BCE. The victors took the technology back to Persia and began producing their own sugar. By the 11th century CE, sugar constituted a significant portion of the trade between the East and Europe. Sugar manufacturing continued in Persia for nearly a thousand years, under a revolving set of rulers, until the Mongol invasions of the 13th century destroyed the industry.

Continue reading...

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

In Eastern Europe, for instance, the number of people living in cities declined by almost one-third during the seventeenth century, as the region became an agrarian serf-economy exporting cheap grain and timber to Western Europe. At the same time, Spanish and Portuguese colonizers were transforming the American continents into suppliers of precious metals and agricultural goods, with urban manufacturing suppressed by the state. When the capitalist world-system expanded into Africa in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, imports of British cloth and steel destroyed Indigenous textile production and iron smelting, while Africans were instead made to specialize in palm oil, peanuts, and other cheap cash crops produced with enslaved labor. India—once the great manufacturing hub of the world—suffered a similar fate after colonization by Britain in 1757. By 1840, British colonizers boasted that they had “succeeded in converting India from a manufacturing country into a country exporting raw produce.” Much the same story unfolded in China after it was forced to open its domestic economy to capitalist trade during the British invasion of 1839–42. According to historians, the influx of European textiles, soap, and other manufactured goods “destroyed rural handicraft industries in the villages, causing unemployment and hardship for the Chinese peasantry.”

Jason Hickel and Dylan Sullivan, Capitalism, Global Poverty, and the Case for Democratic Socialism

104 notes

·

View notes

Text

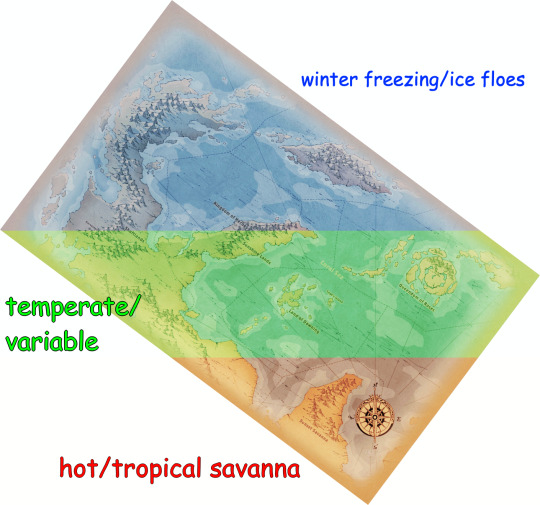

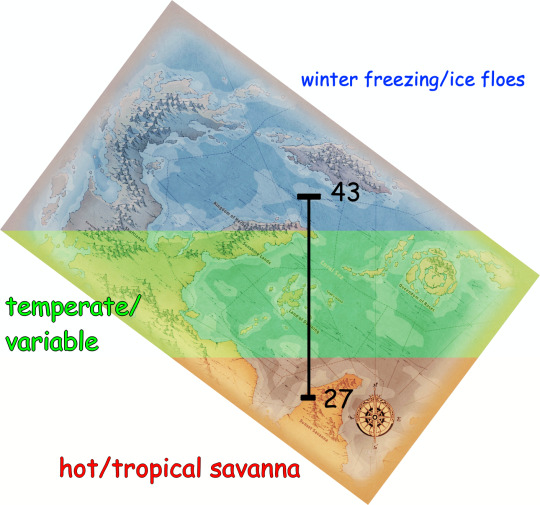

Estimating Twisted Wonderland's Circumference ONCE AND FOR ALL

howdy. In this post, I once attempted to figure out the circumference of Twisted wonderland. Instead, I failed, and just went mad collecting screenshots of random spheres that weren't/might be globes modeling the planet.

that's not important. What IS important is the rant about the map that we DO have that followed. y'see, it looks like this.

Tilted. Cropped. Incomplete. Utterly infuriating. Anyway, we're gonna be working with my SUPERIOR map projection for this theory post.

yeah it's literally just tilted so that North points straight up. There's almost no way to really tell what latitude location is or how large it is compared to the rest of the world... EXCEPT...

...FOR THE CLIMATES.

it's pretty easy to label the middle section as "temperate," since summers are hot, winters are snowy, and every other season is pretty comfortable.

The northern parts of the Coral Sea can be determined as arctic or near-arctic, because Azul and the tweels don't bother being there during the winter due to the ice covering the water's surface. The furthest south that winter sea ice extends on earth is the coast of Hokkaido, Japan, at 43 degrees north.

Last but not least, as Sunset Savanna is based on the setting of the lion king, that makes it a tropical savanna. The most northern tropical savanna on earth is the Terai–Duar savanna at the base of the Himalayas in India, at 27 degrees north.

Therefore, this whole (VERY inexact) area I marked on this map that holds the temperate zone is around 16 degrees of Twisted Wonderland's latitude, possibly more.

Now, we don't exactly have a giant perfect ruler that we can use for reference. but we DO have the next best thing: Sage's Island!

And 16 degrees of Twisted Wonderland's latitude seems to beeee…

22 Sage's Islands long!

So this lil island is about 0.727 degrees long.

Now, I'm none too confident in my island-length-guessing ability. So i gotta say Sage's Island is like... maybe 3 miles long, north to south.

Soooo... 3 miles is 0.727 degrees in Twisted Wonderland.

That means 1 degree is 4.126 miles.

And that means the full 360 degrees of Twisted Wonderland's circumference is... drumroll please...

...

1,485.36 miles/2390.46 kilometers.

Give or take, I mean. I'm not a scientist. I don't even play Twisted Wonderland.

PLEASE understand that is a TINY amount. Earth's circumference is 40,075.017 km. PLUTO has a circumference of 7,231 km. Twisted wonderland is smaller than Pluto.

We were ROBBED of Yuu being capable of jumping 50 feet in the air due to the weaker gravity.

#i guess you could say...#it's a small world after all#heheheHA#shitpost#twisted wonderland theory#twst#cartography#'yuu's power is beast taming/cooperation/being blunt.' No their power is their 50 FOOT VERTICAL LEAP#can you tell i read too much of John Carter of Mars#this whole theory falls apart if sea ice and tropical regions just extend farther in Twisted Wonderland for some reason#or if the map isnt to scale at ALL#it also falls apart if.. yknow... the world is flat.#which it might be. we dont have confirmation of a round world for TWST.#small planet twisted wonderland#headcanon

237 notes

·

View notes

Text

Guest essay by Gregory Wrightstone

As the love affair with so-called green energy cools and “net zero” commitments to eliminate “carbon emissions” wane, we see glimmers of acknowledgment for the benefits of carbon dioxide. That’s right: More people are beginning to understand that the gas – widely demonized as a pollutant endangering Earth with excessive heat – is a life-giving substance needed in greater amounts.

U.S. voters know that President-elect Donald Trump has declared the Green New Deal a “scam” and promises to return common sense to environmental regulations and energy development. His return to office rests partly on that pledge.

In Europe, German politicians whose green fetish has produced economic decline face serious electoral challenges. And developing countries like India ignore “decarbonization” promises to aggressively develop coal mines and import more of the fuel to spur growth and eradicate poverty.

Less frequently reported is the story of carbon dioxide emissions greening the Earth and boosting crop production. Educating the public on the benefits of carbon dioxide is the mission of the CO2 Coalition, which I lead. We sponsor speakers and publish scientifically based materials for adults and children. Much of the information is about the role of CO2 as a beneficial greenhouse gas in moderating the extremes between daytime and nighttime temperatures and as a photosynthetic plant food.

“Fossil Fuels Are the Greenest Energy Sources” by Dr. Indur Goklany is an example of our work. Did you know that up to 50% of the globe has experienced an increase in vegetation and that 70% of the greening is attributed to plant fertilization by carbon dioxide emissions from fossil fuels? Or that nearly 200,000 square kilometers of the southern Sahara have been converted to a lush grassland from desert?

Few have heard that doubling atmospheric CO2 from its current concentration of 420 ppm would significantly increase agricultural productivity and have little effect on the climate.

It appears that some of this knowledge has reached Canada because Alberta’s ruling Unified Conservative Party (UCP) recently approved a resolution that promotes the salutary effects of CO2 and endorses an outright rejection of the national government’s net zero policy.

“It is estimated that (atmospheric) CO2 levels need to be above 150 ppm (parts per million) to ensure the survival of plant life,” says the proposal for a resolution eventually adopted by the party. “The Earth needs more CO2 to support life and to increase plant yields, both of which will contribute to the health and prosperity of all Albertans.”

The UCP calls for abandoning CO2’sdesignation as a pollutant and for recognizing the gas as “a foundational nutrient for all life on Earth.”

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Surya ☀ Talon Abraxas

Surya, the chief of the Navagraha ( the nine Classical planets) and important elements of Hindu astrology, is the main solar deity in Hinduism and generally referred to as the Sun in Nepal and India.

He is often depicted riding a chariot harnessed by seven horses which might represent the seven colors of the rainbow or the seven chakras in the body. He is also the presiding deity of Sunday. The Sun God is shown with 4 hands, three of which are carrying a wheel, a conch-shell and a lotus respectively and the fourth is see in the Abhay Mudra.

Being the source of warmth and light, he has the ability to control the seasons and the power to withhold or grant the ripening of the crops. As the economy is mainly agricultural based, the Sun is placed amongst the highest of the Gods, especially for the agricultural communities.

He is also known as the “pratyakshadaivam” – the only God visible to us every day. The Sun God is “Karma Sakshi”, who has eternal wisdom and knowledge. He is the Source of all life, and it is because of him that life exists. Thanks to the energy from his rays, life on Earth is sustained.

There are different forms of Surya and they are :

Arka form : “Arka” form is worshiped mostly in North India and Eastern parts of India. The temples dedicated to the “Arka” form of Surya are Konark Temple in Orissa, Uttararka and Lolarka in Uttar Pradesh, and Balarka in Rajasthan.

Mitra form : Surya is also known as “Mitra” for his life nourishing properties. The Mitra form of ‘Surya’ had been worshiped mostly in Gujarat.

Surya Namaskar Mantra

Surya Namaskara is performed before the sunrise. The mantras are recited to pray Lord Surya and sandals, flowers, rice grains are offered with water. There are 12 mantras which are different names of Sun God. With each posture, a particular mantra is chanted. Surya Namaskar Mantras are :

“Aum Mitraya Namah” “Aum Ravayre Namah” “Aum Suryaya Namah” “Aum Bhanave Namah” “Aum Khagaya Namah“ “Aum Pushne Namah” “Aum Hiranyagarbhaya Namah” “Aum Marichaye Namah” “Aum Adityaya Namah” “Aum Savitre Namah” “Aum Arkaya Namah” “Aum Bhaskaraya Namah”

Meaning :

‘Salutation to Who is friendly to all. The shining one, the radiant one. Who is the dispeller of darkness and responsible for bringing activity. One who illumines, the bright one. Who is all-pervading, one who moves through the sky. Giver of nourishment and fulfillment. Who has golden color brilliance. The giver of light with infinite number of rays. The son of Aditi, the cosmic divine Mother. One who is responsible for life. Worthy of praise and glory. Giver of wisdom and cosmic illumination.’

Benefit : Surya Namaskar mantras, a set of mantras chanted along with a combination of few Yogasana postures, are useful in achieving concentration. It is a wonderful regular routine of exercise, prayer and worship given as in the scriptures.

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Singapore’s prosperity has long set it apart from many other former British colonies. There is another difference, too: Singapore has clung to honouring its former colonial ruler — and it wants to keep doing so.

Special accolade has gone to Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles, who is considered to have founded modern Singapore in the early 1800s. For decades, Singapore’s textbooks credited Raffles with transforming the island from a “sleepy fishing village” into a thriving seaport. He has been the central character in a larger official narrative that says imperial Britain had set up Singapore for success as an independent nation.

Dedications to Raffles dot the landscape of Singapore. A business district, schools and dozens of other buildings bear his name. Two 2.5-metre likenesses of the man loom large in downtown Singapore.

But a new statue of Raffles, installed in a park in May, has revived a debate about the legacy of colonialism in Singapore. On one side is the broader establishment, which has held up British colonial rule positively. On the other are those who want a closer inspection of the empire that Raffles represented and the racial inequity he left behind, even as Singapore became wealthy.

This divide has surfaced before, perhaps most prominently a few years ago when Singapore celebrated the bicentennial of Raffles’ arrival on the island. Now, the new statue has set off a fresh debate, with critics pointing out that other countries have for years been taking down monuments to historical figures associated with slavery or imperialism, or both.

“The thing about Raffles is that, unfortunately I think, it has been delivered as a hagiography rather than just history,” said Alfian Sa’at, a playwright who wants to see the Raffles statues destroyed. “It’s so strange — the idea that one would defend colonial practice. It goes against the grain on what’s happening in many parts of the world.”

The new statue of Raffles stands next to one of his friend Nathaniel Wallich, a Danish botanist, at Fort Canning Park. Tan Kee Wee, an economist who pooled $330,000 with his siblings to commission the statues, said he wanted to commemorate the pair’s role in founding Singapore’s first botanic gardens, which were his frequent childhood haunt. He donated the sculptures in his parents’ name to the National Parks Board.

Opponents have also criticised the government for allowing the statue to go up at the park because it was the site of the tomb of precolonial Malay kings. The parks board said it considered historical relevance in the installation of the sculptures.

Questions about the statue have even been raised in Singapore’s parliament. In June, Desmond Lee, the minister for national development, responded to one by saying that Singapore did not glorify its colonial history. At the same time, Lee added, “We need not be afraid of the past.”

The plaque for the Raffles statue explains how Singapore’s first botanic gardens “cultivated plants of economic importance, particularly spices”. That, critics said, was a euphemism for their actual purpose: cash crops for the British Empire.

Tan defended the legacy of British colonialists in Singapore, saying they “didn’t come and kill Singaporeans”.

He added: “Singapore was treated well by the British. So why all this bitterness?”

Far from benign

But colonial Britain was far from benign. For instance, it treated nonwhite residents of Singapore as second-class citizens. Raffles created a town plan for Singapore that segregated people into different racial enclaves. And he did not interact with the locals, said Kwa Chong Guan, a historian.

“He was very much a corporate company man, just concerned with what he assumed to be the English East India Co’s interests,” Kwa said.

Raffles landed in Singapore in 1819 as Britain was looking to compete with the Dutch in the Malacca Strait, a crucial waterway to China. At the time, Singapore was under the sway of the kingdom of Johor in present-day Malaysia. Raffles exploited a succession dispute in Johor to secure a treaty that allowed the East India Company to set up a trading post in Singapore.

Within a handful of years, Singapore was officially a British territory. Convict labour, largely from the Indian subcontinent, was crucial to its economic development. So, too, were Chinese immigrants, which included wealthy traders and poor labourers.

Singapore achieved self-governance in 1959, then briefly joined Malaysia before becoming an independent republic in 1965. It has since built one of the world’s most open economies and among its busiest ports, as well as a bustling regional financial hub.

In recent years, the government has acknowledged, in small ways, the need to expand the narrative of Singapore’s founding beyond Raffles. Its textbooks now reflect that the island was a thriving centre of regional trade for hundreds of years before Raffles arrived.

In 2019, officials cast the commemoration of Raffles’ arrival as also a celebration of others who built Singapore. A Raffles statue was painted over as if to disappear into the backdrop. Placed next to it, though only for the duration of the event, were four other sculptures of early settlers, including that of Sang Nila Utama, a Malay prince who founded what was called Singapura in 1299.

To some historians and intellectuals, such gestures are merely symbolic and ignore the reckoning Singapore needs to have with its colonial past. British rule introduced racist stereotypes about nonwhites, such as that of the “lazy” Malay, an Indigenous group in Singapore, that has had a lasting effect on public attitudes. Colonialism led to racial divisions that, in many ways, persist to this day in the city-state that is now dominated by ethnic Chinese.

“If you only focus on one man and the so-called benevolent aspect of colonialism, and you don’t try to associate or think about the negative part too much, isn’t that a kind of blindness, or deliberate amnesia?” said Sai Siew Min, an independent historian. (Story continues below)

Role of race

Race relations played a role in Raffles’ ascension in Singaporean lore. Soon after Singapore became independent, the governing People’s Action Party — which remains in power decades later — decided to officially declare Raffles the founder of Singapore. Years later, S Rajaratnam, who was then the foreign minister, said that anointing a Malay, Chinese or Indian as its founder would have been fraught.

“So we put up an Englishman — a neutral, so there will be no dissension,” Rajaratnam said.

The decision was also meant to indicate that Singapore remained open to the West and free markets.

In a 1983 speech, Rajaratnam acknowledged that Raffles’ attitude toward the “nonwhite races was that without British overlordship the natives would not amount to much”.

Critics of the Raffles statues also argue that his legacy should reflect his time on the island of Java. Although Raffles outlawed slavery in Singapore, he allowed trading of slaves in Java, including children as young as 13, according to Tim Hannigan, who wrote a book about Raffles.

The new statues of Raffles and Wallich were created by Andrew Lacey, a British artist. The sculptures evoke the two men as apparitions — symbolism that Lacey said represented the world’s evolution away from the West.

Lacey said he had “wrangled” with the public reaction toward his sculptures and he had no qualms if Singaporeans wanted to take them down, destroy them or replace their heads with the Malay gardeners who were instrumental in creating the botanic gardens.

“I was cognisant of the complexities of making any dead white male,” he said of Raffles. “I wasn’t cognisant of the degree of complexity around him.”

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

i'm finding it so surprising that no one (yes including me) hasn't really done any exploration into pavitr's village life. it's in his (comic) lore, it's where his story is first started out, and lowkey it never gets talked about, neither by the audience nor marvel. we're gonna change that >:)

no but i completely understand why we as the audience mightn't've delved into this route before. most of us online folk don't have *that* much experience working on the land. i'm not judging anyone for it, it's just something i've noted. on that note i'm pointing fingers at marvel themselves for brushing over such an important facet of the character- he's got all the hallmarks of regular peter parker spider-man, but where peter's stories oft highlight his origins and the different experiences he has as someone from the suburbs, the same isn't done for pavitr!! there are no flashbacks to his time as a village boy after he moves into mumbai!!! there is no discussion regarding any experience in his youth!!! (there is exactly only 1 flashback in 2023's SMI #5 and it is only 6 panels long talking about helping those in need). that whole portion of his life is just NOT THERE and i can't keep living life like this.

truth be told the only reason i'm even making this post at all is because i got a little too inspired by the stories my parents have told me. we've got tales of parents disobeying their parents and playing out in the streets 'til nightfall and all that. but hearing my parents talking about the joy they've managed to find between hours of tending the crops, going to school, catching the buses, avoiding spooky marshes and abandoned houses, catching rainwater and racing paper boats, making sculptures out of clay and twine, catching fish in the wells and butterflies between bushes, being present in communities and village gatherings...there is so much more to life than we realise.

i'm genuinely not talking about cottagecore aesthetics when i say i think working on the land might've healed something in me. sure a bunch of the things that i do now might definitely be squandered, but different parts of me *could* have flourished if i was tilling and such. many of the core parts of me would've remained, but i'd probably be putting my energy in a bunch of other things (like tilling and such, obviously. and then crying over harvests). the second-generation immigrants yearn for the fields (it's me, i'm the second-generation immigrant).

FURTHERMORE (with uppercase and in bold, that's when you know i'm being serious) if i were to take a more sociopolitical look at things, i think pavitr being personally connected to the land in some way, shape or form can actually provide insight into the livelihoods of modern agriculture and the farming industry. obviously centred on desi farming practices, but also on the global scale, if that can be allowed. he can shed light on a bunch of issues!!! he can fight for the rights of farmers, of those who tend to the land, and the members of the community!!!!

i don't know! i don't know. i just think spider-man india can provide a beautiful avenue to explore and appreciate the livelihoods of farmers and rural and/or indigenous communities. he can also highlight societal issues working against them and shed light on ways we can better everyone's circumstances while preserving these unique experiences and cultural practices. i don't know. i just think it's neat.

pavitr prabhakar, if only marvel would let me into spidey hq i'd do you SO MANY FAVOURS i'd bring in a new age of spidey india comics fr fr i'd also blast nick lowe into the sun so in fact spider man would be free forever from stupid idiots

#pavitr prabhakar#spider man india#atsv#atsv pavitr#spider man#desi culture#desi agriculture#agriculture#im using desi very broadly bc i want to be able to capture ALL of these collective experiences like they should all be recognised#agnirambles#i just know there will be people who will skip over this bc i didn't make a whimsical silly pavitr post and instead i'm talking about farms#i'm giving a chance for the boy to breathe and speak for the collective desi experience!! he's a vehicle for ideas!!! don't hound him!!!!#all i ask is for your thoughts and considerations on this post... that is all 🥺

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nomadic Cities are the thing that make the less sense about Arknights to me. Where do they get their food from? Leaving aside the physical and technical issues because something something Originium, a city moving over terrain as depicted would be incredibly devastating, leaving a trail of barren land down below (I think that Beanstalk has some dialogue to that effect even) To get enough food to supply an urban civilization, especially an industrial civilization like Terra, you need enormous extensions of cultivated land, close to urban zones if possible, which is impossible if cities move and devastate the land around them. I mean, look at those tracks and tell me that the land below wouldn't be pushed to a muddy mess:

The lack of ocean routes in Terra also limits how much food you could, speculatively, import from other more 'sedentary' countries (land transport is always more inefficient than sea transport), and I haven't seen too much railways or highways to support inland trade routes, so where does their food come from?

The thing is, they move because of catastrophes, understandable, and perhaps the catastrophes aren't common enough to move all the time. But if catastrophes aren't so common, why spend all this effort in making them nomadic? And if they are so common to justify this, it means that sedentary populations, which are basic for agriculture, are impossible, and so neither cities or farming is sustainable and you have no civilization at all, let alone an advanced industrial civilization. It all comes to where the food comes from. If I had to explain it, I would say that they plant it somewhere in the city infrastructure, indoors agriculture powered by originium reactors or something, but it's still something I would like to see, and at least from the few images it literally looks like a plate with wheels and a city above, no layers for indoors agriculture; if anything, you would use the top layer to cultivate stuff such as fruit and delicate crops, and live in the lower layers.

I actually thought at first they were flying cities, when I saw all the references to Rhodes Island deck and the fact it's called an island. And believe it or not, to me it would make so much sense. Imagining, say, Lungmen as a collection of floating cities, Laputa style, while the terrain down below is rural and densely cultivated like say China or India, but at the mercy of catastrophes which city dewellers can avoid, creating class conflicts. Transporting things would be easy assuming originium allows cities to float, air transport would also be trivial, it would be a question of floating above a region and sending transports to collect crops, perhaps directly from farmers themselves. It would be a wholly different game setting though, because you will have introduced the omnipresence of air transport and have to deal with that (and Arknights has a conspicous lack of air warfare or support; there are some brief mentions of pilots but we never see them in action, one would think the operator squads would have something like a Mi-24 or a Huey helicopter assigned to them)

#cosas mias#el biotipo plays arknights#arknights#worldbuilding#*puts a gun to your head* WHERE DOES THE FOOD COME FROM#edit: OH AND WATER. WHERE DO YOU GET YOUR WATER FROM.#biotipo worldbuilding

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

The current landscape of hyper-local urban farming across Asia

Globally, urban farming is evolving as cities seek innovative solutions to sustainably feed their growing urban populations. Techniques like vertical farming and hydroponics are at the forefront, allowing crops to be grown in layered setups or water-based environments, minimizing land use, and reducing water consumption.

Urban farming in Asia presents a rich tapestry of approaches, each shaped by the unique challenges and priorities of the region’s diverse cultures and economies. The rapid urbanization and dense population clusters in Asia make urban agriculture not just a choice but a necessity, driving innovation and adaptation in several key areas.

China

China has become a leader in urban agriculture through heavy investment in technology and substantial government support. Initiatives like the Nanjing Green Towers, which incorporate plant life into skyscraper designs, exemplify how urban farming can be integrated into the urban landscape.

The government has also implemented policies that encourage the development of urban farming, providing subsidies for technology such as hydroponics and aquaponics, which are vital in areas with contaminated soil or water scarcity.

Japan

With its limited arable land, Japan has turned to creative solutions to maximize space, such as rooftop gardens and sophisticated indoor farming facilities.

One notable example is the Pasona Urban Farm, an office building in Tokyo where employees cultivate over 200 species of fruits, vegetables, and rice used in the building’s cafeterias.

This not only maximizes limited space but also reduces employee stress and improves air quality.

Singapore

Singapore’s approach is highly strategic, with urban farming a crucial component of its national food security strategy. The city-state, known for its limited space, has developed cutting-edge vertical farming methods that are now being adopted globally.

The government supports these innovations through grants and incentives, which has led to the success of vertical farms. These farms use tiered systems to grow vegetables close to residential areas, drastically reducing the need for food transportation and thereby lowering carbon emissions.

India

In contrast to the technology-driven approaches seen in other parts of Asia, India’s urban farming is largely community-driven and focuses on achieving food self-sufficiency.

Projects like the Mumbai Port Trust Garden take unused urban spaces and convert them into flourishing community gardens. These projects are often supported by non-governmental organizations and focus on employing women, thus providing both social and economic benefits.

Thailand

Thailand’s urban farming initiatives often blend traditional agricultural practices with modern techniques to enhance food security in urban areas. In Bangkok, projects like the Chao Phraya Sky Park demonstrate how public spaces can be transformed into productive green areas that encourage community farming. These initiatives are supported by both local municipalities and private sectors, which see urban farming as a way to reduce food import dependency and improve urban ecological balance.

The Philippines

In the Philippines, urban farming is an adaptive response to urban poverty and food insecurity. Metro Manila hosts numerous community garden projects that are often grassroots-driven, with local government units providing support through land and resources. These gardens supply food and serve as educational platforms to teach urban residents about sustainable practices and nutritional awareness.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

good god girl, maybe some of us are not vegan because we eat chicken like once in three months?? Would reduction not be a more productive goal of vegan activism than outright banning? Like if your arguments are that animals are being eaten, then you’re being unrealistic about the entire actual concept of the food chain. Humans are omnivores, you do not need to change that to achieve your goals.

A vegan lifestyle is also entirely the product of your geographical location. If you live somewhere that shit does not grow, what are you going to do?? I just think about the difference between food options in India and Canada, for example. India: between the tropics (tropics and equator even, in fact). All-year-round sun, there’s pretty much always stuff growing. Different kinds of land will mean you can grow everything from staples like rice and wheat to vegetables, fruits and plantation crops. It’s reflected in the cuisines: Indian food has a much, much wider offering of vegetarian food, and many more Indians have restricted diets that more or less overlap with vegetarianism. Because crops grows. Locally.

Canada. Harvest in the fall, from November to March, your fields are practically unusable. Compare the prices of fresh produce in (and now I’m being generous to give you a highly populated, non-remote province here for an example) Ontario. Ontario has farms where in the fall you get fresh autumn vegetables and fruits. You’ll also get them in larger quantities. It is way cheaper, fresher and also uses less energy and fuel to transport the vegetables like 50 km from farm to market.

Come the winter and nothing grows. If you look at most vegetables you’ll find on store shelves in December or February, and most of it is either imported from warmer regions of the US (often the case for chains that are in both countries) or from South American countries (sometimes SA -> USA -> Canada). The importing has to go through cross-country customs, had to be driven for days, is less fresh or rich in nutrients by the time you get it, and is more expensive. Of course. And we all come out of it poorer. Is it any wonder why people will eat meat? We’re even talking here about a place like Ontario, very well connected on North American trade routes. Can you justify someone in Yukon deciding to eat meat over a $17/lb. green veg? Be for fucking real…

There simply cannot be a blanket-global solution to animal products. You’ve got to work with what your geography has to offer. It’s the same thing we say when we say that avocados have an environmental cost when you expect them to be available year-round in places they don’t grow. We encourage people to go for more local produce there, and I think the same should go for all parts of your diet too. If your animals are local, then their footprint is lower than importing kiwis from New Zealand to the US. I don’t see how that’s hard to understand.

#veganism#the first para is a rant bc someone was being an idiot but I mean the rest of it most sincerely:#YOU HAVE TO WORK WITH YOUR GEOGRAPHY#capitalism has you thinking the whole world Is this flat homogenous thing#and all things can be solved by ‘buying (new solution)!’ *Buy!* our new Vegan Leather and feel good about yourself!#(<- plastic that will end up in a dump as Indonesia’s problem; not the pontificating American vegan’s)#*~Buy!!~* our new honey substitute! 100% cruelty free by avoiding the bees; even as the bees literally continue to make honey anyway#(<- monocrop agave fields in Mexico can deal with your misplaced guilt for you 🥰💕)#Like. At least have the courage of your convictions and quit sweetener entirely if you’re#concerned about both cruelty (which honey harvesting is not but okay) and sustainability. Or switch back to sugarcane.#Unless of course sustainability is simply someone else’s problem 😊 (hi third world!!)#My problems with veganism the movement are also my problems with the west; you all are really fucking hypocrites.#We have to go cleaning up after you guys all the time. You HAVE to work WITH your geography; not against it#Plants are not some miraculous catch-all solution. And mate; you’ve got to kill a plant to eat it too#Plants are alive; trust me. If you don’t eat anything for fear of killing it you’ll either be living on roadkill and infect and die#or you’ll end up killing yourself out of not! eating!#; you can’t eat rocks. All food was once alive.

14 notes

·

View notes

Photo

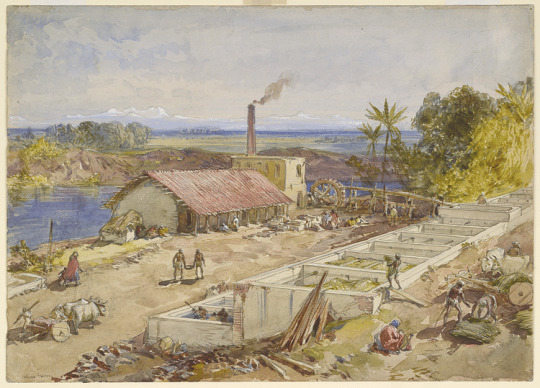

Indigo Revolt

The Indigo Revolt (aka Indigo Riots or Blue Mutiny) of 1859-60 in Bengal, India, involved indigo growers going on strike in protest at working conditions and pay. The subsequent violence was aimed at exploitative European plantation owners, but the cause was, during and after, taken up by anti-colonial Indian liberals as an example of the necessity for independence.

The Indigo Trade

India was known for its cotton textiles through the Middle Ages, and by the mid-16th century Gujarat in northwest India was major a source of indigo, the deep blue-violet dye used to colour cotton and other materials. Indigo was in high demand by the European trading companies, including the British East India Company (EIC) which made large profits from its export. The EIC used well the long-standing expertise of Indian indigo growers and dyers, particularly in centres such as Sarkhej in Gujarat and Bayana in neighbouring Rajasthan, both in northeast India.

The making of indigo dye was a long and labour-intensive process. The plant cuttings were harvested once a year in June or July before the onset of the rainy season. These were then taken to a factory by cart where they were emptied into large vats to steep in water. The dyed water and mash was then boiled as this brought out a richer colour in the indigo grains, which then had to be strained out. The grains were next pressed into dried cakes, which were in turn pressed into barrels or, alternatively, the mass was cut into cubes and packed into chests ready for transportation. Most indigo was shipped to Calcutta (Kolkata) for sale to merchants who then organised shipment to England or the Americas where it was used to colour textiles. From the late 18th century, Bengal became the major centre for indigo production, accounting for 67% of London's total imports of the dye in 1796 (around 2 million kilograms) and then rising further into the 19th century.

The indigo industry was a volatile one. Too much or too little rain greatly affected the quantity and quality of the dye produced each year, and in boom years, overproduction brought a crash in the price. Still, for the long-term investor, indigo could be a very lucrative industry indeed. Unfortunately, the financial speculation that resulted in such a crop with potential for large gains was another source of instability. Finally, the location of many indigo plantations made them prone to flooding, which not only damaged the crop but often swept away the factory facilities.

Continue reading...

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Submitted via Google Form:

If say 90% of my world has been cremating the dead for 100,000+ years, how does that affect the world physically on the large scale? I'm talking land use, soil composition, crop growth if it's common to use cremains as fertiliser, its effect on climate etc…

Tex: I’m making the tentative assumption that at some point in those hundred thousand-plus years, a more efficient means of cremation has been invented that is resource-efficient compared to the traditional method of burning upon a pyre. If this is the case, then the footprint would be rather low, and likely also ecologically efficient. I can’t say for sure whether it’s a good idea to use cremation remains as fertilizer, but a lot of land would be freed up for other uses that would otherwise have been designated for graveyards.

Licorice: Cremated human remains do not make good fertiliser. I know this from personal experience with a loved one’s memorial tree that we killed by ‘fertilising’ it with her ashes. It was only after we’d done this that we found out from experts that human ashes are harmful to most plant life.

I should think that after 100,000 years your society would have figured out that using cremains as fertiliser is not helping their crops to grow.

In India they have been cremating their dead for many thousands of years and I don’t think it has an adverse effect on the land, but it won’t be a positive one either. I believe it’s just neutral, as long as you’re not spreading those ashes on your fields.

If it’s important to your worldbuilding to use human remains as fertiliser (which honestly, I think would be a very respectful way of using the bodies we leave behind) perhaps they could have developed some form of human composting: https://www.nationalreview.com/corner/turning-our-dead-into-fertilizer/

Utuabzu: Historically, many cultures have cremated their dead, ranging from Japan to Ancient Greece to the Aztecs to India, and a whole lot of others. It’s probably the second most common means of dealing with the dead, after burial. However, cremation requires a very high temperature, around 900°C, which even with a modern closed furnace does require a fair amount of fuel. An open pyre would need even more. Any society that cremates their dead is going to have to account for that fuel, likely with managed forestry.

After that, there’s still going to be large bone fragments. Modern western crematoria usually grind these down into a fine powder, but in eastern Asia the bone fragments are usually collected and stored. You’ll need to consider what this world’s cultures do with the bone and ash, and also any other remains, like metals from medical implants and tooth fillings (we usually recycle them).

If you’re going for low environmental impact, the method of disposition with the lowest environmental cost is probably exposure. It’s rare, most prominently practiced by Tibetans and Zoroastrians, but it doesn’t really require any fuel and does return most of the body to the ecosystem rapidly. But unless you’ve got a good cultural/environmental/theological reason most people find it kind of upsetting.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

A new study launched this week highlights the work of Andhra Pradesh Community-Managed Natural Farming (APCNF) and the remarkable untapped potential of agroecological natural farming in Andhra Pradesh, India. Spanning over 6 million hectares, and involving 6 million farmers and 50 million consumers, the APCNF represents the largest agroecological transition in the world. Amidst the diverse landscapes of Andhra Pradesh, this state-wide movement is addressing a multitude of development challenges—rural livelihoods, access to nutritious food, biodiversity loss, climate change, water scarcity, and pollution—and their work is redefining the way we approach food systems. Farmers practicing agroecology have witnessed remarkable yield increases. Conventional wisdom suggests that chemical-intensive farming is necessary to maintain high yields. But this study shows agroecological methods were just as productive, if not more so: natural inputs have achieved equal or higher yields compared to the other farming systems��on average, these farms saw an 11% increase in yields—while maintaining higher crop diversity. This significant finding challenges the notion that harmful chemicals are indispensable for meeting the demands of a growing population. The advantages of transitioning to natural farming in Andhra Pradesh have gone beyond just yields. Farmers who used agroecological approaches received higher incomes as well, while villages that used natural farming had higher employment rates. Thanks to greater crop diversity in their farming practice, farmers using agroecology had greater dietary diversity in their households than conventional farmers. The number of ‘sick days’ needed by farmers using natural farming was also significantly lower than those working on chemically-intensive farms. Another important finding was the significant increase in social ‘capital’: community cohesion was higher in natural farming villages, and knowledge sharing had greatly increased—significantly aided by women. The implications for these findings are significant: community-managed natural farming can support not just food security goals, but also sustainable economic development and human development. The study overall sheds light on a promising and optimistic path toward addressing geopolitical and climate impacts, underlining the critical significance of food sovereignty and access to nourishing, wholesome food for communities. Contrary to the misconception that relentlessly increasing food production is the sole solution to cater to a growing population, the truth reveals a different story. While striving for higher yields remains important, the root cause of hunger worldwide does not lie in scarcity, as farmers already produce more than enough to address it. Instead, food insecurity is primarily driven by factors such as poverty, lack of democracy, poor distribution, a lack of post-harvest handling, waste, and unequal access to resources.

153 notes

·

View notes

Text

Madras [...] [was] the English East India Company (EIC)’s most important settlement on India’s Coromandel Coast [...]. [T]he town’s survival as an EIC colony often depended on the deployment of medical and natural historical knowledge in regional diplomacy during a critical period of its existence. [...]

---

Established in 1639, the English East India Company’s settlement at Madras (also known as Madraspatam or Chinapatam, now Chennai) had quickly become the focal point of EIC operations on the Coromandel Coast. By 1695, Samuel Baron described it as ‘the most considerable to the English nation of all their settlements in India whether ... in reference to the trade to and from Europe, or the Commerce from one part of India to the other’. The later attempts to establish trades to China and Japan, to resettle the Indonesian archipelago, and to gain a foothold in Bengal, were all directed from Fort St George. [...]

Browne [an English surgeon] used his patrons in the Mughal establishment and the Company hierarchy to build up a lucrative business supplying drugs to the camps of the Mughal generals. Browne’s contacts in the Mughal army were also useful for the Company [...].[D]uring the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, Madras was in a difficult position. [...] Again, Company officials turned to the network of surgeons with access to the Mughal hierarchy [...]. In 1707, the year of the Emperor Aurangzeb’s death and a time of political unrest in the Mughal Empire, Bulkley was sent to Arcot on a mission that combined medical and diplomatic aims. While there, he also collected several volumes of plants and information about their medicinal virtues. [...] The network of contacts that could be built up between physicians, who had the advantage of close personal access to those at the centre of power, was an important way to exchange information and gifts. [...] Knowledge of plants and the means of employing them was thus crucial to establishing the East India Company’s position in India [...].

---

The Company’s gardens [...] also revealed, in their beds and borders, the networks that Madras was embedded within, as ships brought seeds and plants from other Company settlements, the territories of the rival European powers, and places of regional trade [...]. The surgeons used their space in the Company gardens to experiment with local plants and to introduce crops from around the world. [...] Both Browne and Bulkley also raised plants they received from their networks of correspondents overseas: Browne describes growing China root, a popular medicinal substance normally identified with Smilax China, rhubarb, cinnamon trees from Ceylon (Sri Lanka), and wild agallo, benjamin and camphor from Manilla. [...]

[T]he scramble for the manuscripts or [plant] collections [...] [demonstrates] that the acquisition of natural knowledge was a crucial part of the competition between European trading companies to acquire and exploit the wealth of the Indies. Each of the two surgeons [Browne and Bulkley] [...] also sent a huge amount of plant materials to various correspondents in Europe [...]. Among the contacts that the surgeons maintained in England were several London apothecaries including his brother-in-law, who ran a shop in Bread Street, and Mr Porter, a drug-gist in Cornhill Street. The circle of botanists who received collections from the East Indies formed a close, though not always friendly, group of experimenters and gardeners who constituted the overlapping membership of the East India Company, the Royal Society, and the Society of Apothecaries.

The web of contacts that the two surgeons maintain within the colonial world of the Indian Ocean were invaluable because they provided them with the materials necessary to make Madras a ‘centre of calculation’ by supplying them with materials on which comparisons and connections to their own collections could be drawn. [...] Bulkley wrote at a time of transition in both England and India. [...] However, it is clear at least that by the time Bulkley died in 1713, being buried at the end of his garden, the United Company was more securely established at Madras, as expressed in its now immaculate gardens.

---

The networks of doctors had been crucial diplomatic actors in a critical period during which many believed that Madras was fated to be eclipsed altogether. [...] It was the new relationship with the rulers of Arcot established by these doctors that eventually enabled the Company to consolidate its base at Calcutta.

The surgeons’ collections reflect the hybrid environment of early modern Madras and the networks – maritime, military and diplomatic – that the doctors were embedded in [...]. Many details are missing from this reconstruction of the practice of medicine and botany in the early colonial city. Unlike the contributors to the Hortus Malabaricus, we never learn so much as the names of the Tamil and Telugu-speaking doctors who were so crucial in collecting and revealing the medicinal uses of the specimens the surgeons sent to London. Nevertheless, the role of these collaborators was clearly crucial. [...]

The collections of these two surgeons, who were key players in the transformation of politics and botany in the region, straddling local and international concerns, in many ways provide the perfect portal through which to view Madras as it was transformed from a trading post subservient to the interests of regional powers to a major player in British colonial expansion.

---

All text above by: Anna Winterbottom. “Medicine and Botany in the Making of Madras, 1680-1720.” In: The East India Company and the Natural World, edited by Vinita Damodaran, Anna Winterbottom, and Alan Lester. 2014. [Bold emphasis and some paragraph breaks/contractions added by me.]

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

Embracing a Holistic Approach: The Multifaceted Activities of Shree Krishnayan Gaurakshashala

In the heart of India, Shree Krishnayan Gaurakshashala stands as a beacon of compassion and sustainability, embodying a deep commitment to the well-being of cows, community, and the environment. Through a series of dedicated initiatives, the gaushala has transformed into a multifaceted hub where spiritual, agricultural, and humanitarian efforts converge to create a positive impact on society. Here’s a closer look at the diverse activities undertaken by this remarkable institution.

Cow Protection: A Sanctuary of Hope

Home to over 21,000 stray and destitute Desi Indian cows and bulls, Shree Krishnayan Gaurakshashala provides a sanctuary where these revered creatures receive a second chance at life. Rescued through various channels, including police, government agencies, NGOs, and farmers, these gauvansh are sheltered, nourished, and cared for with utmost dedication. The gaushala’s in-house medical facility, staffed by experienced veterinarians, ensures that each cow receives timely and comprehensive healthcare, fostering their well-being and longevity.

Shelter and Nourishment: Building a Safe Haven

The gaushala boasts expansive shelters, meticulously designed to accommodate the growing number of protected cows. These shelters provide a comfortable and dignified living environment, reflecting the institution’s commitment to creating a holy and safe space for gauvansh. Nourishment is another cornerstone of care at the gaushala, where a balanced diet of dry fodder, green fodder, grains, mustard cake, and jaggery is carefully prepared and served twice daily. This holistic approach to feeding ensures that the cows remain healthy, strong, and vibrant.

Medical Care: Ensuring Health and Well-Being

Around-the-clock medical care is a priority at Shree Krishnayan Gaurakshashala. With a fully equipped medical facility on-site, the gaushala is prepared to handle any health concerns that may arise. From routine check-ups to emergency care, the dedicated team of veterinarians and support staff work tirelessly to maintain the health and well-being of the gauvansh. Ample stocks of medicines and vaccinations are maintained to prevent and treat illnesses, ensuring that each cow receives the best possible care.

Breeding and Training: Promoting Indigenous Cows

The gaushala is actively involved in research and breeding programs aimed at enhancing the genetic traits of indigenous cows. By focusing on disease resistance, adaptability, and milk production, the institution seeks to create a sustainable ecosystem where farmers are encouraged to keep Desi cows. Additionally, vocational training programs are offered to farmers, educating them on the importance of organic farming and the benefits of desi cows and bulls. These initiatives aim to preserve cultural heritage and promote sustainable agricultural practices.

Renewable Energy and Organic Farming: Pioneering Sustainability

Shree Krishnayan Gaurakshashala is a model of sustainability, harnessing renewable energy through biogas plants and solar power systems. The gaushala’s BIO CNG plant, powered by ONGC, converts 25,000 kg of cow dung daily into CNG gas and manure, contributing to a cleaner environment and the production of organic fertilizers. The institution also promotes organic farming, encouraging pesticide-free crops and eco-friendly practices, with a mission to convert surrounding villages into organic lands.

Humanitarian Efforts: Serving Communities in Need

Beyond its work with cows, Shree Krishnayan Gaurakshashala extends its compassion to human communities, especially during times of calamity. From providing relief during floods in Madhya Pradesh and Uttarakhand to distributing food during the COVID-19 pandemic, the gaushala’s humanitarian efforts have touched countless lives. The institution regularly sends truckloads of supplies to remote regions and runs food camps, ensuring that those in need receive essential nourishment and support.

Spiritual and Cultural Initiatives: Nurturing the Soul

The gaushala is also a center for spiritual and cultural enrichment. The magnificent yagya mandap, situated on the serene banks of the Ganga, hosts various sacred rituals, including Yagyas, Pujas, and Japas. These spiritual endeavors are conducted by accomplished Vedic Brahmins, creating an atmosphere of divine grace and positive energy. The institution’s yoga center, in collaboration with Jhanvi Yoga Dhyan Sevashram Trust, offers yoga, meditation, and Ayurvedic treatments, promoting holistic well-being and spiritual growth.

Conclusion

Shree Krishnayan Gaurakshashala is more than just a shelter for cows; it is a sanctuary where compassion, sustainability, and spirituality intersect. Through its diverse activities, the gaushala not only protects and nurtures Desi cows but also uplifts communities, promotes environmental stewardship, and fosters spiritual growth. It is a shining example of how dedicated efforts can create a ripple effect of positive change, benefiting both the present and future generations.

12 notes

·

View notes