#capitalism has you thinking the whole world Is this flat homogenous thing

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

good god girl, maybe some of us are not vegan because we eat chicken like once in three months?? Would reduction not be a more productive goal of vegan activism than outright banning? Like if your arguments are that animals are being eaten, then you’re being unrealistic about the entire actual concept of the food chain. Humans are omnivores, you do not need to change that to achieve your goals.

A vegan lifestyle is also entirely the product of your geographical location. If you live somewhere that shit does not grow, what are you going to do?? I just think about the difference between food options in India and Canada, for example. India: between the tropics (tropics and equator even, in fact). All-year-round sun, there’s pretty much always stuff growing. Different kinds of land will mean you can grow everything from staples like rice and wheat to vegetables, fruits and plantation crops. It’s reflected in the cuisines: Indian food has a much, much wider offering of vegetarian food, and many more Indians have restricted diets that more or less overlap with vegetarianism. Because crops grows. Locally.

Canada. Harvest in the fall, from November to March, your fields are practically unusable. Compare the prices of fresh produce in (and now I’m being generous to give you a highly populated, non-remote province here for an example) Ontario. Ontario has farms where in the fall you get fresh autumn vegetables and fruits. You’ll also get them in larger quantities. It is way cheaper, fresher and also uses less energy and fuel to transport the vegetables like 50 km from farm to market.

Come the winter and nothing grows. If you look at most vegetables you’ll find on store shelves in December or February, and most of it is either imported from warmer regions of the US (often the case for chains that are in both countries) or from South American countries (sometimes SA -> USA -> Canada). The importing has to go through cross-country customs, had to be driven for days, is less fresh or rich in nutrients by the time you get it, and is more expensive. Of course. And we all come out of it poorer. Is it any wonder why people will eat meat? We’re even talking here about a place like Ontario, very well connected on North American trade routes. Can you justify someone in Yukon deciding to eat meat over a $17/lb. green veg? Be for fucking real…

There simply cannot be a blanket-global solution to animal products. You’ve got to work with what your geography has to offer. It’s the same thing we say when we say that avocados have an environmental cost when you expect them to be available year-round in places they don’t grow. We encourage people to go for more local produce there, and I think the same should go for all parts of your diet too. If your animals are local, then their footprint is lower than importing kiwis from New Zealand to the US. I don’t see how that’s hard to understand.

#veganism#the first para is a rant bc someone was being an idiot but I mean the rest of it most sincerely:#YOU HAVE TO WORK WITH YOUR GEOGRAPHY#capitalism has you thinking the whole world Is this flat homogenous thing#and all things can be solved by ‘buying (new solution)!’ *Buy!* our new Vegan Leather and feel good about yourself!#(<- plastic that will end up in a dump as Indonesia’s problem; not the pontificating American vegan’s)#*~Buy!!~* our new honey substitute! 100% cruelty free by avoiding the bees; even as the bees literally continue to make honey anyway#(<- monocrop agave fields in Mexico can deal with your misplaced guilt for you 🥰💕)#Like. At least have the courage of your convictions and quit sweetener entirely if you’re#concerned about both cruelty (which honey harvesting is not but okay) and sustainability. Or switch back to sugarcane.#Unless of course sustainability is simply someone else’s problem 😊 (hi third world!!)#My problems with veganism the movement are also my problems with the west; you all are really fucking hypocrites.#We have to go cleaning up after you guys all the time. You HAVE to work WITH your geography; not against it#Plants are not some miraculous catch-all solution. And mate; you’ve got to kill a plant to eat it too#Plants are alive; trust me. If you don’t eat anything for fear of killing it you’ll either be living on roadkill and infect and die#or you’ll end up killing yourself out of not! eating!#; you can’t eat rocks. All food was once alive.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gusto ko lang i-share ang artikulong ito para sa susunod na may pagagamitan, alam ko kung saan kukunin. Maliban dito, naging mulat ako sa kalagayang pangwika at kung gaano ito kahalaga. Hindi ako wika ang pinag-aralan ko kundi panitikan subalit dahil sa mga kursong itomuro ko sa taong ito, binuksan nito ang posibilidad na magustuhan ko ang pag-aaral sa wika. Ang pagpapahalaga sa pagtanggap sa iba't ibang wika na mahalaga at may halaga. Sa katunayan, ayos nga itong ginagawa kong blog kasi nailalahad ko ang sarili at nagagamit ko ang wika. At higit sa lahat naiuuwi ko ang interes sa pagsulat muli nang sa ganoon tuluyang mahasa ito.

___________________________________________

LINGUA OBSCURA

What We Lose When We Lose Indigenous Knowledge

By mistaking a culture’s history for fantasy, or by disrespecting the wealth of indigenous knowledge, we’re keeping up a Columbian, colonial tradition.

A collection of Native American utensils and weapons.

By: Chi Luu

October 16, 2019

This week, more and more regions in the U.S. celebrate Indigenous People’s Day, but many more know the federal holiday as Columbus Day. More than 500 years ago, a guy known as Christopher Columbus got famous for something he never did, having never even set foot on the North American continent, much less having “discovered” it. But Columbus should perhaps be more notorious for something he did do.

It’s remarkable the lopsided stories we tell in order to conveniently ignore or deny an uncomfortable reality. As we continue to celebrate the sepia-toned world of a false past, full of men and monsters and their colonial cruelties, as entire cultures, their languages, their knowledge, and their science were destroyed along the way.

After getting lost somewhere in the Bahamas, the friendly Arawak people Columbus met helped him, bringing food, water, and gifts. He even wrote of how kind they were. Columbus repaid their generosity by mocking their “ignorance” of things they had never seen before, forcing them to be his slaves, and demanding that they lead him to the source of the gold that their earrings had been crafted from. Columbus and his men proceeded to commit brutal acts, to destroy this peaceful population, thinking “nothing of knifing Indians by tens and twenties and of cutting slices off them to test the sharpness of their blades.” One of his associates, Bartolomé de las Casas wrote: “Such inhumanities and barbarisms were committed in my sight as no age can parallel. My eyes have seen these acts so foreign to human nature that now I tremble as I write.” Bartolomé de las Casas promptly quit the world to become a priest.

Once you know the full stomach-churning story, it’s hard to imagine how such a person, who treated whole populations as less than human, could be celebrated.

Some historians argue that you can’t blame Christopher Columbus for being a product of his time, which is a nice, convenient story. Nevertheless, contemporary accounts of Columbus’s senseless cruelty, and his subsequent arrest for his behavior, suggests that even taking racist historical attitudes into account, this was unspeakably barbaric. Once you know the full stomach-churning story, it’s hard to imagine how such a person, who treated whole populations as less than human, could be celebrated.

One of the most persistent and damaging legacies colonizers left behind was perpetuating the myth that they were men of action and science and business, modernizing all worlds they encountered. Indigenous nations all over the world, whole peoples and unique cultures, were framed as ignorant, culturally and socially backward, even primitive, with nothing to offer a new and exciting modern society. Columbus and the many colonizers after him are still commemorated hundreds of years later for “discoveries” of entire nations that already existed, with their own cultures and political systems and ways of understanding the world.

Columbus is remembered for his supposed contributions to science (such as “proving” that the earth was a sphere, despite most people knowing that long before him), to business (kicking off a global capitalism in the slave trade, for instance), to human progress in the exchange (read imposition) of Western ideas and values on supposedly backward cultures. But these first people, far from being scientifically impoverished, had already developed a rich and robust science and knowledge of their own, with their own language and understanding of how their world worked. It’s become ever more important for us tell, and listen, to those other stories, to balance the one-sided tales of destructive conquest with a focus on the indigenous peoples, who have far more to offer the world than many would think.

Is there really only one way to build a modern society, one based on Western ideology, with progress through constant growth and consumption? Is there only one kind of science we can use to truly understand the world? There’s hardly an indigenous culture surviving that does not struggle to preserve their traditional language and knowledge against the overwhelming homogenizing influences of Western colonialism.

There is still large scale dismissal and disrespect of indigenous language and traditional knowledge, based on the widespread belief that it contributes “nothing to the development of knowledge, humanities, arts, science, and technology.” Scientists and scholars, the very people who strive to objectively preserve the world’s knowledge, may regularly reject or misinterpret information. When knowledge does not take the scientific forms we’ve come to expect from academic research, it’s rejected, but that’s due to an unthinking bias about what value traditional knowledge has to offer. If it isn’t in the form of a scientific report or paper, but is delivered in the form of a story, it’s regarded as unscientific and anecdotal folklore, no matter what new information is being conveyed.

We are slowly learning how crucial traditional knowledge and language diversity is in areas such as biological diversity, especially with the rapid decline of rare plant and animal life in unique ecosystems around the world. Their unique properties have long been recorded by indigenous groups through their language—if anyone had ever cared to look and listen. In many places, scientists are finding, to their surprise, that traditional knowledge is on a par with many scientific discoveries. As many endangered languages die out, so do the unique discoveries their speakers have preserved across generations in their oral histories.

But what does it mean when we accept traditional knowledge as a kind of science only after it’s been compared with contemporary scientific knowledge and processes, and shown to be similar? Why is it that we don’t just respect and trust the work of indigenous scholars, researchers, and scientists, who may present their work in a different form to scientific conventions? As more researchers understand the value of different ways doing science, there have been calls for there to be an integration of long disregarded indigenous knowledge into the academy’s scientific process. Traditional knowledge often values a more nuanced, contextual, and holistic view of information from observation and thought, not just piecemeal experimentation of discrete, individual components of a system.

The Tewa scholar Gregory Cajete says of “Native science” that:

…it is a metaphor for a wide range of tribal processes of perceiving, thinking, acting, and ‘coming to know’ that have evolved through human experience with the natural world. Native science is born of a lived and storied participation with the natural landscape. […It] is the collective heritage of human experience with the natural world.

It’s not hard to see how these different approaches could complement each other, one collective and holistic, one individual and detailed, if both sides were able to engage with each other. We know that stories and oral histories are memorable and effective tools for teaching and learning science, but they are often rejected as not serious or scientifically rigorous enough. There’s more than one way to record knowledge and more than one way to engage in scientific explorations and observation, just as there is more than one way to frame our reality and experiences through language.

The way we talk and use language to explain phenomena does not interfere with our ability to do objective, informative research, yet this is often something unthinkingly assumed about other cultures.

It’s easy to forget that the reality of our lives, through our very language, has been mapped out in conceptual metaphors—micro stories where we think and talk about things in terms of something else we all can relate to. We march on with life in a straight line, with our futures ahead of us and our pasts behind, our feelings colorful, green with envy, seeing red, feeling blue, as we build up our scientific theories about the world till they’re safe as houses, their foundations unshakeable. These are our realities, yet they are not real.

The way we talk and use language to explain phenomena does not interfere with our ability to do objective, informative research, yet this is often something unthinkingly assumed about other cultures. It’s easy to misinterpret the metaphorical language of an indigenous culture as though it was a literal belief, especially if a researcher was predisposed to thinking of those people as very different, or unscientific, or even primitive.

How would a strange alien researcher judge us? As the anthropologist Roger Keesing points out in the Journal of Anthropological Research (link above), we may consider ourselves modern, but we often talk like people before the people before Columbus, who knew the earth was round. In our metaphorical language, we think of the world around us as flat. The sun rises and sets at either end of the earth in this reality, and we all accept this as normal, even though we know that little story we tell ourselves to understand the world is astronomically untrue. “But it would be nonsense for an ethnographer of England or the U.S. to write that ‘the natives believe that the earth is flat and that the sun goes up and comes down,’ or that ‘the natives believe that the heart is the seat of the emotions.'”

Yet that is the kind of generalized misinformation that gets set down in the records about many indigenous cultures. Yes, it is —so long as that alien ethnographer starts from a position of respect for the people they were studying, and assumed they understood the realities of the world as well as anyone can, and that it’s just a little matter of language that makes it seem like they believe the impossible. When people are very different from ourselves, it’s easy to believe they’ll believe anything. We may often misinterpret the things we hear, choosing readings that make that culture seem more exotic and different. Keesing wonders if scientific explanations that try to account for some ambiguous indigenous concepts that are hard to understand can actually end up inventing whole belief systems for indigenous peoples that just aren’t real. Not all fantastical sounding language is magic; sometimes it’s just ordinary.

For example, the mysterious Oceanic Austronesian concept of “tapu/tabu,” which was brought to the English language as “taboo” by the controversial Captain James Cook, has been recorded with a sense of the “sacred,” “forbidden,” but also “unclean” or “cursed.” It’s a somber, foreboding, and certainly exciting reading of what appears to be a serious religious belief of the people of the Pacific. But “tapu” is contradictory, sometimes a positive in terms of its air of sanctity and a negative in terms of its cursed uncleanliness. How can it make sense to be both?

Keesing points out that it can be read, more boringly, as something like “off limits,” because things are usually “tapu” in certain contexts to certain people, in a nuanced way. Things are not “tapu” in the absolute, infused with a strange mystical energy by gods and ancestors as they are revered by credible worshipers. Relatively speaking, someone can sensibly define what’s off limits, “tapu,” and that could be a god making a religious pronouncement or it could be parents telling their kid not to do something. Or it could be as blandly ordinary as the related word “kapu,” which some modern Hawaiians put on their non-magical fences to mean “no trespassing.”

There are many ways of seeing the world, and indigenous cultures all around it have had a long time to amass a great knowledge about how things work. They have evolved languages to tell people about it in ways that they could understand. By mistaking a culture’s hard won history for a fantasy, or by disrespecting the wealth of knowledge in all its different forms, treating it as worthless because it doesn’t look like the conventions we expect, we’re merely keeping up a Columbian, colonial tradition of treating people not like ourselves as less than human. And that might cost us more than we expect.

Resources

JSTOR is a digital library for scholars, researchers, and students. JSTOR Daily readers can access the original research behind our articles for free on JSTOR.

What We Want to Be Called: Indigenous Peoples' Perspectives on Racial and Ethnic Identity Labels

By: Michael Yellow Bird

American Indian Quarterly, Vol. 23, No. 2 (Spring, 1999), pp. 1-21

University of Nebraska Press

The Turn Toward the Indigenous: Knowledge Systems and Practices in the Academy

By: Kerstin Knopf

Amerikastudien / American Studies, Vol. 60, No. 2/3 (2015), pp. 179-200

Universitätsverlag WINTER Gmbh

Conventional Metaphors and Anthropological Metaphysics: The Problematic of Cultural Translation

By: Roger M. Keesing

Journal of Anthropological Research, Vol. 41, No. 2, Language and Poetics (Summer, 1985), pp. 201-217

The University of Chicago Press

Indigenous Knowledge, Science, and Resilience What Have We Learned from a Decade of International Literature on “Integration”?

By: Erin L. Bohensky and Yiheyis Maru

Ecology and Society, Vol. 16, No. 4 (Dec 2011)

Resilience Alliance Inc.

Writing Stories in the Sciences

By: Eunbae Lee and John C. Maerz

Journal of College Science Teaching, Vol. 44, No. 4 (March/April 2015), pp. 36-45

0 notes

Text

Sojourn Country Report: North Korea by Amy Ferris

North Korea is a place that is very far away-not only physically, but culturally too. Sojourning to this far away land is sure to titillate any traveler yearning for something different, maybe even a little absurd. I say this because North Korea is a place that remains functionally influenced by the old Soviet era, with many parts of the capital city Pyongyang resembling Communist-era cities in Russia. Even more odd, is that this appearance goes along with a traditional Korean culture that unlike South Korea, hasn’t changed much in almost a century. As a matter of fact, there used to be huge portraits of Lenin and Marx hanging on the brutalist style buildings in Pyongyang. Now though, the pictures of those leaders are gone, leaving only the current leader (Kim Jong Un) to stake any claim in leading the country. Unfortunately, North Korea is a country infamous for its lack of human rights and closed borders, being nicknamed “The Hermit Kingdom”. Let’s take a closer look at some of the features of North Korea.

The normal starting point for any tourist or sojourner travelling to North Korea is Pyongyang. This is North Korea’s showcase capital, and it is the largest and most developed city in the country. Pyongyang is a place where the most elite of North Koreans live, who in this country are usually the top scientists and government workers. These elite people usually hail from a long line of family members who have served the “leaders” faithfully or made great contributions to the betterment of the country. While you’re out on your closely-monitored tours around Pyongyang, keep in mind that the city and the people that you see there are not typical North Koreans. Many people in this country are very poor, and outside of Pyongyang the streets are poorly maintained, and most people live in more traditional style Korean flats. While in Pyongyang, you may notice the sporadic blackouts. This happens because the city relies on coal for power, and their economy isn’t strong, so they don’t have enough resources to keep it reliable. When the power goes out, relax and notice that the North Koreans around you just keep working like nothing happened. They’re used to it, and they are probably not allowed to mention it, as this makes the country- well, the “leader” look bad. I don’t advise making a big deal out of issues like this. I actually don’t advise making a big deal out of anything you see there at all. Anyone visiting North Korea should really just keep their opinions to themselves and mind their proverbial “P’s and Q’s”

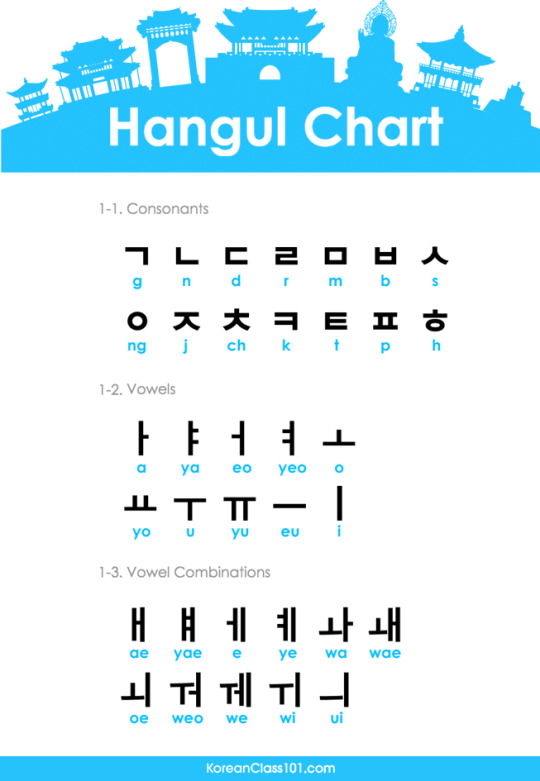

So, onward now to North Korea’s language and culture. This country, like other Eastern Asian countries is homogeneous. This means that the overwhelming majority of people in North Korea are ethnically Korean. They all speak Hangul, which is what the Korean Language is called. Interestingly, even though the North and South Koreas have been separated for quite some time, the language is relatively the same. Time does change things slowly though, and North Korea has been left behind in time. Their mannerisms and dialects are archaic compared to South Korean Hangul. Imagine if a time-travelling American businessman from the 1940’s appeared and started banging on about how swell things were here. I think that’s how outdated the North Koreans sound to other non-North Korean Hangul speakers. Since Hangul is a language that functions much like Japanese, it is a context-based language.

Basic customs and culture in North Korea are traditional in a lot of ways. Women in North Korea are not typically considered leaders, and they’re not equal to men. The women are closer to women from the American 1940’s or 50’s, as they are encouraged to be teachers or housewives. Women outside the city also do other jobs suitable for females such as farming and cleaning public spaces. There are women in higher positions such as scientists and Professors though, and jobs like this are not banned for them. Men in North Korea are mostly relegated to “manly” jobs like construction and sculpting, farming too of course. Gender doesn’t matter at all in one field though- the military. North Korea has a huge military and most citizens are required to complete long enlistments. In America, the normal enlistment contract for all services is usually four years for people who want to join, but in North Korea that enlistment requirement can be ten years long.

North Koreans aren’t religious, as the “leader” forbids the worshiping of anyone but him or his family. The closest thing to a religion is the concept of “Juche”, or “self -reliance” in North Korea. This is the propaganda that the first president Kim Il Sung came up with to convince the people to accept being trapped in this country, and to believe that the whole world is against them. Anyway, I am sure that there are North Korean people who believe in different things of course, but they are not allowed to show it, and they can only talk about it with people they trust.

Entertainment in North Korea has become its own phenomenon. Hearkening back to the old Soviet State in places like Russia and Ukraine, there is only one state-run news station on TV, featuring “The Pink Lady”. She is a news reporter who can be found loudly proclaiming the soon-to-be defeat of all opposition to North Korea while images of ballistic rockets launch behind her on the green screen. Radio is just the same, often only playing patriotic war songs and the required minute-to-minute praising of the “leader”. Unfortunately, many people around the world are unaware of the artistic abilities of the North Korean people in both performance, art and film. I suggest trying to attend the Arirang festival which is held in the biggest stadium in the world in Pyongyang. Also, there is a home-done film festival tradition now in North Korea as well, as the animation techniques and filmography in North Korea is actually pretty good.

Lastly, but surely not least- a quick word about food. North Korean is a country riddled with poverty and famine. They struggle to grow enough food for themselves, but they are very generous when it comes to foreign visitors. This is due to a generally East Asian cultural obligation to take care of their guests well, and also to show (pretend) that they have more than enough food to go around. Almost everything that happens here has a political charge to it, food being no exception. Regardless, the most typical kinds of food eaten in North Korea is rice, pickled vegetables and hot peppers like what is in kimchi, various soups and kimbap rolls. There is a chance for receiving some mystery meat as well, as animals such as dog and horse is not a taboo food to eat in North Korea. Try your best to be polite and don’t waste food in front of people who may not have eaten much that day.

All photos credited below by order shown:

1: REUBENTEO PHOTOGRAPHY

2. REUBENTEO PHOTOGRAPHY

3. AFP/GETTY IMAGES

4. ERIC LAFFORGUE

5. KOREANCLASS101.COM

6. REUTERS

7. AP PHOTO/WONG MAYE-E

8. JENS PATTKE

9. POSTED BY BANKAILCHIGO12345 ON YOUTUBE

https://youtu.be/dEco-k7ra5g

10. Ph

11. STEPHAN

12. avant-garde.com

0 notes

Text

[yourandyourbs] explains how economics have changed in the last 80 years, how economic objectives are the key (employment vs inflation targets), and why traditional orthodoxy will fail us all in modern world.

Now, I have to tell you Kennedy isn’t making these rules up. They did become orthodoxy in advanced-economy treasuries in the 1980s. They’re the reason John Kerin’s budget of 1991, delivered in the depths of "the recession we [didn’t] have to have" contained zero stimulus, meaning the stimulus, when it came in February 1992, came too late.

This view isn't wide enough and lacks all the details. The worlds entire global economy software was changed, not just ours, under the guidance of Milton Friedman.

1945-1980 - Computer software No.2:

After WW2, the world's economy would be restored with the USD. The policy target would be full employment as this was believed to stop the rise of fascists again (they need to look at this again). We had homogenous national economies, we all produced most of the same stuff, fridges, cars etc... There was restricted financial markets. Growth would be lead by wage growth, high taxes and transfers would be the government's steering mechanism for the economy, and the government kept much of the commanding heights of industry under democratic/national capital control - Telecom, Qantas etc - again a steering mechanism to make sure this form of capitalism worked. No one gave a shit who ran the central bank and no one knew their name.

A lot of this came from the ideas of economist John Maynard Keynes, and his ideas are credited for getting the world out of the great depression when the Friedmanite types wanted to do nothing (let the market fix itself, it's magic!)

I've posted this quote from Keynes' book - The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money - here before, but I'll do it again, as it's a good summarisation of the key concept behind the 1945-1980 era.

"If the Treasury were to fill old bottles with banknotes, bury them at suitable depths in disused coalmines which are then filled up to the surface with town rubbish, and leave it to private enterprise on well-tried principles of laissez-faire to dig the notes up again (the right to do so being obtained, of course, by tendering for leases of the note-bearing territory), there need be no more unemployment and, with the help of the repercussions, the real income of the community, and its capital wealth also, would probably become a good deal greater than it actually is. It would, indeed, be more sensible to build houses and the like; but if there are political and practical difficulties in the way of this, the above would be better than nothing."

As opposed to Milton Friedman's right wing capitalist fairy tale of the market will fix itself.

There is a bug in this post WW2 software, as is with all forms of capitalism (why people like Marx thought capitalism was always in a crisis), which led to the stagflation crisis - which led to the global software reboot. We are led to believe that creating money creates inflation. While this can be true in certain circumstances and if it is abused too far, it's not the key driver. During this post WW2 era, full employment and strong labour led to high wage growth. For capitalists to keep paying workers more and to see their ROI's, they needed advancements in productivity and they had to raise prices. Eventually, the bug hit and inflation rose so high they didn't want to invest - so they withheld their capital, a capital strike.

The stagflation crisis. During this post WW2 era, it was a debtors paradise. You'd borrow money for houses and whatever, and because of the inflation, it was easy to pay the money back. Boomers had banks eat half their mortgages in inflation. The problem arose when it went so high that capital didn't want to invest. Inflation can be a good thing, right now, we're in a private debt hole and inflation would help us get out of it. Inflation too low is as bad as too high. Today, it is too low. Money creation is not raising inflation, not even when many trillions were dumped into the global economy after 2008 - Milton Friedman and his laissez-faire hacks were wrong. Full employment and strong labour drove inflation, not money creation.

We see an immense amount of money creation today both through governments and through the financial system, and inflation is extremely low. I remember watching all the laissez-faire hacks screaming after the 2008 crisis that QE would bring hyper-inflation (and they urged you to buy their gold)... It of course never happened. Inflation didn't budge.

While something had to be done to fix the stagflation crisis, capital took advantage of the crisis and swung everything too far in their favour. We just needed to bring down inflation partially, not all the way. There's a few mechanisms for this and we didn't need to destroy labour in the process.

So we get to 1980-2008, computer software No.3:

The policy target changes from full employment to price stability. The value of capital is to be "restored". The mechanism is maximum global integration and deregulated financial markets. The price of money shoots through the roof to slow inflation. The welfare state is to be wound back. Labour markets would become "flexible". Growth would now be led by profits, not wage growth (any wonder why wages are going flat). The steering mechanism of democracy and national capital would be ended and this would be handed over to private capital. Suddenly, everyone knows who runs the central banks - because the price of money becomes so important.

There would be low taxes and low transfers (the redistribution). Inflation is brought to extremely low levels. Because wage growth no longer drove growth, it's now dependent on a credit bubble - and thus the bug of this Milton Friedman/neoliberal software hits. People can only borrow so much money, especially when their wages aren't rising and the low inflation isn't eating any of the debt. The extremely low inflation is a creditors paradise - until the debts can't be paid back. The whole thing blows up in 2008 and we're in a kind of limbo, transition phase.

It's near dead, but the capitalist class have put the system onto life support by dumping massive amounts of money into the world's economies (money that goes mostly to the top) while telling the plebs they need to live within their means.

This should all sound really familiar to people across the world. It wasn't something that was just done in Australia. For some reason, we're in a global economy and people still view the system through a national lens. Australia doesn't matter much to capitalist power, and we're just along for the ride. Just as in the past, we'll change our software when capitalist power changes theirs. We seem to be unable to deal with it democratically and nationally, with a neoliberal media filling heads with bad ideas.

From a capitalist perspective (I don't even consider myself a capitalist, I think the world has to do better for many reasons - especially environmental sustainability), we need to bring back some of the 1945-1980 software. We see fascism rising across the world today, and full employment is what deals with that, just as it did in the past. We need higher inflation and wage growth, just not too high. The problem is capitalism is near impossible, perhaps impossible to manage well. It always falls into a pile of shit. Albert Einstein did not call capitalism "economic anarchy" for no reason.

In a globalised world, it won't be possible to go back to completely homogenous national economies, but we can partially do this. The key is the policy target. Full employment and wage growth over price stability and profit growth. There is also another key. Stop listening to the cheerleaders of free-markets. They believe in 18th-century fairy tales about what capitalism is and what it can achieve. They are ideological and frankly, religious about markets. Their economic models have numbers that stack up on paper, but they don't reflect the reality of capitalism. They've never been taught anything critical about capitalism.

Professor Richard Wolff is an economist who has degrees from Harvard, Stanford and Yale, and he says it clearly - I was never taught anything critical about capitalism, just a big song and dance about how perfect it is. If you want to understand the flaws of capitalism, you need to hear its critics, not its cheerleaders. Some capitalists are rational... Business Insider recommends their viewership to read Karl Marx - so they can better understand the flaws of this system. They don't play a childish propaganda game that Marx was Satan himself.

I am by no means a Paul Krugman fan. Krugman's idiocy (and most of the economist class) is what led us down this hole. But I'll give him this. Eventually, he saw that his globalised, neoliberal capitalist fairy tales from the 90's were wrong.

“Economists, as a group, mistook beauty, clad in impressive-looking mathematics, for truth.” - Paul Krugman.

0 notes