#German Literature Month

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Daniela Krien's My Third Life (Mein drittes Leben)

German author Daniela Krien who was born in the former G.D.R. published her first novel We Will Tell Each Other Everything (Wir werden uns alles erzählen) in 2011. Long before Kairos she told the story of a passionate love story between a very young woman and a much older man during the final months of the DDR. I found the book a little mawkish but not bad at all, especially in the parts that…

View On WordPress

#germanlitmonth#Books#Daniela Krien#Fiction#German Literature#German Literature Month#Literature#Novel

0 notes

Text

“Guilt is never to be doubted.” #kafka #germanlitmonth

I have been following along with the German Lit Month posts, and there have been some very interesting ones so far. This week is designated for reading some Franz Kafka, and I had a bit of a think plus a rummage on the stacks to see what I had available. As you will see from the image at the bottom of this page, I have plenty of Kafka options, and as the bulk of my reading of his work took place…

0 notes

Text

When and why yellow was first applied to people of East Asian descent is rather murky.

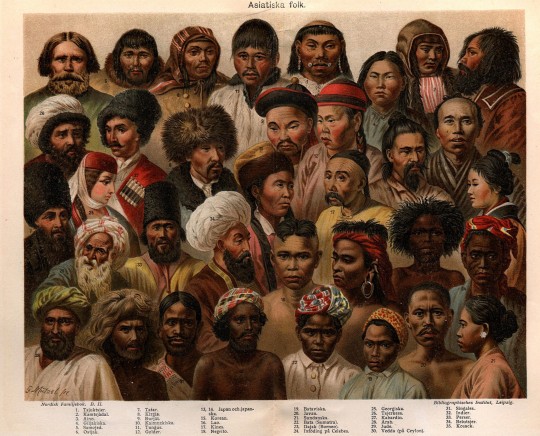

The process occurred over hundreds of years. As some scholars have noted, it's not as if there were people with yellow skin. The whole "yellow equals Asian" thing had to be invented. And in fact, there was a time when there was no such thing as "Asian" — even that had to be invented.

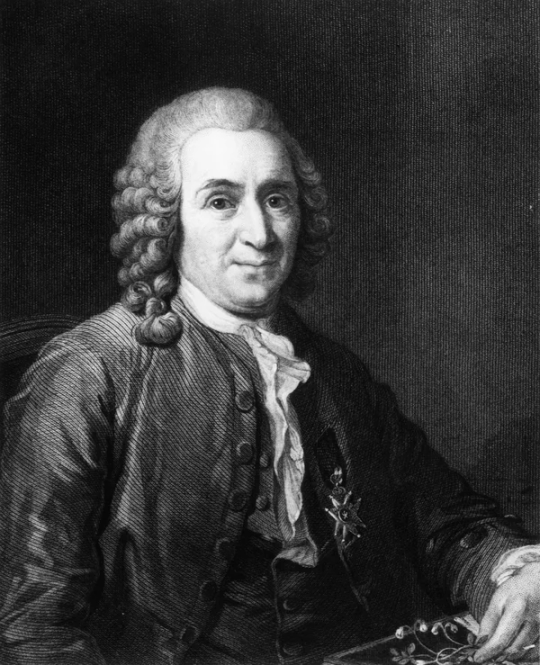

Enter Carl Linnaeus, an influential Swedish physician and botanist now known as the "father of modern taxonomy." In 1735, Linnaeus separated humans into four groups, including Homo Asiaticus — Asian Man. The other three categories, European, African and American, already had established — albeit arbitrary — colors: white, black and red. Linnaeus, searching for a distinguishing color for his Asian Man, eventually declared Asians the color "luridus," meaning "lurid," "sallow," or "pale yellow."

I get this bit of history from Michael Keevak, a professor at National Taiwan University, who writes in his book Becoming Yellow: A Short History of Racial Thinkingthat "Luridus also appeared in several of Linnaeus's botanical publications to characterize unhealthy and toxic plants."

Keevak argues that these early European anthropologists used "yellow" to refer to Asian people because "Asia was seductive, mysterious, full of pleasures and spices and perfumes and fantastic wealth." Yellow had multiple connotations, which included both "serene" and "happy," as well as "toxic" and "impure."

He tells me that there was "something dangerous, exotic and threatening about Asia that 'yellow' ... helped reinforce."

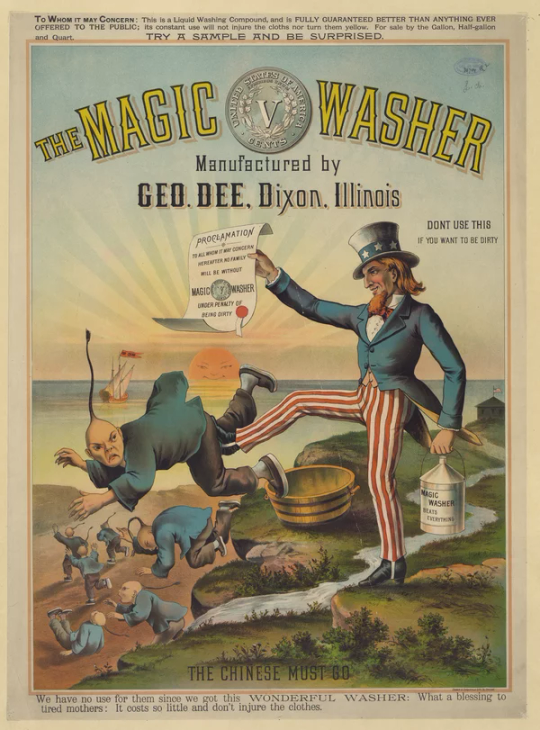

Which might explain why the fear that East Asian countries would take over the West became known as yellow peril.

In 1956, Marvel's short-lived Yellow Claw comic featured a villain of the title's name. He was drawn with a bald head, long scraggly beard, slanted eyes and, yes, fingers that resembled claws. True to the name, his skin had a distinct yellow hue.

That was all make-believe. The real-life consequence of vilifying a race included things like the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which banned Chinese immigration to the United States until 1943; the violence against hundreds of Filipino farmworkers in Exeter and Watsonville, Calif., who were mobbed and driven out of their homes by white Americans in 1929 and 1930; and the incarceration of more than 100,000 Japanese Americans during World War II.

For as long as Asians have lived in the United States, white people have been trying to label us: who we are, what we look like and how we should be described. It was also white people who defined our terminology — for many decades, "Orientals" was the moniker of choice. (And when people hurled slurs at us, we've been called Chinamen, Japs, gooks, Asiatics, Mongols and Chinks.)

That started to shift in the 1960s.

That's when the term "Asian American" was born. At the time, it was linked to political advocacy. Yuji Ichioka, then a graduate student and activist at the University of California, Berkeley, who would later become a leading historian and scholar, is widely credited with coining the term.

This period, often referred to as the Yellow Power Movement, was one of the first times these disparate people — Korean Americans, Vietnamese Americans, Japanese Americans, Indian Americans, Laotian Americans, Cambodian Americans, to name only some — grouped themselves under one pan-ethnic identity.

There was power in numbers, which Ichioka knew as founder of the Asian American Political Alliance. In a letter and questionnaire to new members, AAPA made clear that its organization was not just advocating for the creation of Asian American studies courses, but for broader social causes. That included adopting socialist policies and supporting the Black Liberation Movement, the Women's Liberation Movement, and anti-Vietnam and anti-imperialist efforts.

Spurred in part by the activism of the times, the term "Asian American" rose to popularity. It also helped that the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 was passed, allowing an influx of Asian immigrants to the U.S.

But over the years, the term Asian American revealed itself to be a complicated solution to the problem of identity.

For one thing, most people who technically fit into the "Asian American" category refer to themselves based on their ethnic group or country of origin, according to the National Asian American Survey (NAAS).

Karthick Ramakrishnan, a professor at the University of California, Riverside, and the leader of NAAS, says he and his colleagues found that most Americans think of "Asian Americans" as East Asians.

Karen Ishizuka, who wrote Serve the People: Making Asian America in the Long Sixties, says that "Asian American" is still an important identifier because of the political power it has carried for decades. But it's crucial for people to be educated about what it once meant, she says, because the term has become "more like an adjective now, rather than a political identity."

Ramakrishnan and Ishizuka seem to reinforce why I've been searching for a term like yellow. In all my conversations about this issue, I've found myself remarking how the question of "What about yellow?" feels so hair-pullingly existential. Maybe it's because Asian American seems like it has been watered down from activism to adjective. I find myself wanting a label that cuts a little deeper.

In 1969, a Japanese American activist named Larry Kubota wrote a manifesto called "Yellow Power!" that was published in Gidra, a radical magazinecreated by Asian American activists at the University of California, Los Angeles.

His words were a rallying cry. "Yellow power is a call for all Asian Americans to end the silence that has condemned us to suffer in this racist society and to unite with our black, brown and red brothers of the Third World for survival, self-determination and the creation of a more humanistic society," he wrote.

Kubota wasn't the only one using yellow in a new and different way.

Ishizuka tells me about a bunch of different groups in the 1960s and 1970s: Yellow Seeds was a radical organization in Philadelphia that published a bilingual English-Chinese newspaper of the same name. The Yellow Identity Symposium was a conference at Berkeley that helped ignite the Third World Liberation strikes. The Yellow Brotherhood was an Asian group made up mostly of former gang members in Los Angeles that tried to disband gangs and curb drug addiction. Yellow Pearl, a play on "yellow peril," was a music project started by an activist group in New York's Chinatown.

I call up Russell Leong. He is a professor emeritus at UCLA and was the longtime editor of the radical Amerasia journal. As a kid, he used to make Yellow Power posters in San Francisco's Chinatown.

"Do you call yourself yellow?" I ask him.

"That's an interesting question," Leong says. "If I'm with a group of yellow people like my close friends, I'll call myself a Chink, a Chinaman, a yellow. But in public, I'm not gonna call anyone else that .... it depends what I'm comfortable with. It's the same with my English or Chinese name. Sometimes I'll use my American name. Sometimes I'll use my Chinese name."

Whatever the word, he adds, "I think it's better that we have more words to describe ourselves."

I get it. Despite the incompleteness of any one term, together they can become a powerful tool.

Still, if there were no term like "Asian American" — if it didn't exist, if we gave up on it entirely — then what could we have to anchor ourselves? After all, it's not just about a word; it's about an entire identity.

Ellen Wu, the historian from Indiana, digs into that point: "To circle back to this question of, do we use something like yellow or brown? ... Why do we even feel like we have to?"

Wu acknowledges that we're always craving words that might come closer to encapsulating who we are.

"I think that invisibility — that feeling that we don't matter, that worse, we're statistically insignificant — in some ways really fuels that desire to have a really concise and meaningful way of talking about ourselves," she says.

I pose all of this to Jenn Fang, an activist and writer who runs the appropriately-named blog Reappropriate.

She's not so convinced that yellow would resolve the issues that plague Asian American. It might be a useful identifier if yellow was used very intentionally and people knew its history, she says. But it could also fall into the same traps as Asian American. With ubiquity, it could eventually lose its power.

Fang also thinks that if people were to identify as yellow, there would be more people staying in their own lanes, so to speak — that, say, East Asians who call themselves yellow might not advocate on behalf of Asians who call themselves brown.

"Are you reclaiming the slur, or reclaiming our history?" Fang asks me. "The thing I'm concerned about is — is [yellow] a truly reflective way of talking about the East Asian American experience? Is yellow more nuancing? ... Or more flattening?"

In the pinnacle of the civil rights era, activists used yellow as a term of empowerment — a term they chose for themselves. In some ways, I'm still seeing that today.

When the director of Crazy Rich Asians, Jon Chu, wanted to include a Mandarin version of Coldplay's song "Yellow" in a pivotal scene of his movie, some people were concerned that including it might not fly in such a high-profile movie about Asians. But that was exactly Chu's point. He wrote a letter to the band pleading his case — he wanted to attach something gorgeous to the word.

"If we're going to be called yellow," Chu wrote, "we're going to make it beautiful."

I can't help but think back to a group of people I spoke to late last year.

The Yellow Jackets Collective is an activist group, the name an echo of the 1960s. They're four people in New York City who identify themselves with a wide swath of terms, in addition to yellow: she/her, womxn, brown, Asian American, femme, child of Chinese immigrants, Korean American, 1st gen., first gen. diasporic and "collaborating towards futures that center marginalized bodies."

I send them an e-mail. "Why yellow?"

They point out that they don't just walk around the world calling every East Asian person they meet "yellow."

"Identity ideally is about you and how you feel and what you believe has shaped you," Michelle Ling responds.

I let Ling's words percolate. I don't know if I'll walk around in the world calling myself yellow — maybe to people who have similar experiences to mine; certainly not around people who've flung slurs at me.

Even so, having different words to choose from is itself a comfort. Having yellow in my arsenal makes me feel like my identity doesn't hinge on just one thing — one phrase, one history or one experience.

After a back-and-forth with the group, something they've written stops me in my metaphorical tracks. It's from the Yellow Jackets mantra; a snapback comment that I can't help but appreciate:

"We say Yellow again because at our most powerful we are a YELLOW PERIL and those who oppress us should be afraid. We are watching you. We are making moves."

In “The Travels of Marco Polo,” the people of China are described as “white.” Records left by eighteenth century missionaries also report the skin color of Japanese and other East Asian people as clearly white. Yet in the nineteenth century, this perception quietly gave way to descriptions as “yellow.” In travel books, scientific discourse, and works of art, portrayals of East Asians began presenting them as having yellow skin. What happened in between?

In his 2011 book “Becoming Yellow: A Short History of Racial Thinking,” National Taiwan University professor Michael Keevak delves deeply into the origins and history of how and why East Asians went from being seen as “white” to being classified as “yellow.”

The first suspect implicated in applying the “yellow” label to East Asian faces is the famed Carl Linnaeus (1707-78). At first, Linnaeus used the Latin adjective “fuscus,” meaning “dark,” to describe the skin color of Asians. But in the tenth edition of his 1758-9 “Systema Naturae,” he specified it with the term “luridus,” meaning “light yellow” or “pale.”

It was Johann Friedrich Blumenbach (1752-1840) who went beyond the coloring ascribed by Linnaeus to apply the completely different label of “Mongolianness.” Regarded as a founder of comparative anatomy, the German zoologist did more than just use the Latin word “gilvus,” meaning “light yellow,” to describe East Asian skin color: he also implicated the Mongols, a name with troubling and threatening connotations for Europeans with their memories of Attila the Hun, Genghis Khan, and Timur.

While the references remained anomalous at first, travelers to East Asia gradually began describing locals there more and more as “yellow.” By the nineteenth century, Keevak argued, the “yellow race” become a key part of anthropology.

But the yellow label came associated with discrimination, exclusion, and violence. Just as no one in the world is purely white or black, neither does anyone actually have skin that is deep yellow. By “creating” a skin color and investing traits such as “Mongolian eyes,” the Mongolian birthmark, and mongolism (the old name for Down syndrome), Westerners made the perceived yellow race synonymous with abnormality. They also responded to the arrival of immigrants from Asia by sounding the alarm over the “yellow peril” - a term with a whole range of negative associations from overpopulation to heathenism, economic competition, and political and social regression. The hidden agenda of this racial color-coding becomes apparent when one considers who benefits from a hierarchy that places “yellow” and “black” beneath “white.”

#kemetic dreams#asian#Blumenbach#german#european#exonym#banning exonyms#yellow#white#yellow people#black#black people#racist#conservatism#political#american politics#liberalism#civil rights#racist words#bruce lee#brownskin#brown skin#asian American#asian american literature#asian american history#asian heritage month#asian american author#asian american pacific islander heritage month#stop asian hate#aapi

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

I have this one friend who's like 7 years older than me and I met during my undergrad while he was doing a PhD (probs not his first) but he's not creepy don't worry, and people would make fun of him because he's never had a real job and literally just jumps from one academic discipline to another, but like I've come to realise he's actually living the best life and I'm so jealous

#he's probably rich but also he got a ton of scholarships Somehow because he's really smart#even though he literally was doing a phd in german literature and then went on to study music#famously not the kind of degrees they give you scholarships for i would know 😭#but anyways he texts me once every six months maybe I'm not exaggerating he's even worse than me#but he writes his messages like a postcard and then he sends pictures!!! agdjjekd what a man#i was really starting to make friends at uni right before the pandemic it was so sad I can't think about it nono pls don't#erola.txt#i just replied to his biannual check-in and I'm also having a life crisis hence the post

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Winding Up the Week #395

An end of week recap “A bridge can still be built, while the bitter waters are flowing beneath.” – Anthony Liccione This is a post in which I summarise books read, reviewed and currently on my TBR shelf. In addition to a variety of literary titbits, I look ahead to forthcoming features, see what’s on the nightstand and keep readers abreast of various book-related happenings. CHATTERBOOKS >> If…

#Anthony Liccione#German Literature Month 2024#German Literature Month XIV#Heather O&039;Neill#Kris Spisak#L.M. Montgomery#Lauren Soloy#Luis Jaramillo#Paul Auster#Paul Auster Reading Week II#Sea Library Magazine#Shahzoda Samarqandi#Shelley Fairweather-Vega#Tove Jansson

0 notes

Text

if you are one of the people who goes to comment sections on jegulus or snape posts, who talks about the DE characters having a place etc etc, i hope this is a wake-up call. i really do.

if you are one of the people that throws around the word nazi when you see this content and the term nazi sympathiser to the people engaging in it? in the nicest way possible, wake the fuck up.

it's important to discuss politics in literature, absolutely. but this is a fandom space and the things people ship have absolutely no repercussions on the real world, nor does it reflect their personal views.

this does.

the richest man in the world doing two back to back nazi salutes at a presidential rally for the most powerful country on the world stage? that has repercussions worldwide.

that has the EU looking at X. that has the EU worrying about X because europe took a massive shift to the right after trump's last presidency and the german government has collapsed. that has the EU worried about the influence of a nazi salute on germany's upcoming elections next month. when the us "government" is run by someone who likes AfD (an extremist far-right german political party), and the richest man in the world stands and does a nazi salute. two, mind you. two nazi salutes back to back?

THAT has repercussions worldwide. not fictional character james potter fictionally kissing fictional character regulus black.

i am normally a lot nicer when i address these things but point blank: you are a vile fucking person if you care more about the fictional politics in a fandom space than the real politics that is playing out right now.

these words in fandom have made so many people so uncomfortable for so long. they have tried to explain how uncomfortable it is to come to their SAFE SPACE and see these words thrown around, to have them themselves be called one when they and their families have been affected.

yall ran to tiktok and cried over americans using the word sweater instead of jumper. yall ran to tiktok and said that words. have. meaning?

apply that here. words have meaning. stop throwing them around and put this energy into real world politics if you're so passionate about stamping out nazi ideology.

#'but it was an analog-' shut up shut up shut up youre literally calling people nazis#we can discuss the politics in books yes!#we should not be applying those politics to the people reading them#open up a history book and watch the fucking news#because if you think you're safe outside of america? if you think this has nothing to do with you?#then you are so uneducated it's painful#words have meaning i beggeth you to stop and let people have their escapism.#you should have woken up ages ago#none of this is a surprise. you were too busy crying about a ship to notice.#messrsrarchives political talks

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today's rabbithole: the origins of "dyadic" as opposite of intersex/h-word

TLDR: "dyadic" seems to come from 1970s radical feminism and seems to have entered intersex vocabulary via gender studies. This implies it is NOT a term coined from within the intersex community.

I've been reading Cripping Intersex since it's this month's pick for @intersexbookclub (and it's not too late for you to pick it up yourself! 💜). One thing that caught my attention is Orr spends a bunch of time presenting the origins of "endosex" and "perisex" as disputed for whether these terms were coined by intersex people or not.

Orr does this because they clearly prefer "dyadic" and are trying to justify why they're talking about "compulsory dyadism" rather than "compulsory endonormativity/perinormativity" etc. 🤨

Interestingly enough, Orr makes absolutely zero attempt in the book to find an origin for the word "dyadic". 🧐 Orr also never questions whether the term "dyadic" actually came from the intersex community. 🧐 So..... rabbit hole time!

Before I get into what I found on dyadic, I wanna quickly fact check Orr on the origin of endosex. Best as I can tell, the term was first used in German in 2000 by Heike Bödeker. Bödeker is controversial for supporting autogynephilia 😬, but I've never seen anybody doubt Bödeker having mixed gonadal dysgenesis. If anybody knows of an older use of endosex, please send it my way! But as far as I can tell, "endosex" was coined by an intersex person.

Okay, onto the origin of dyadic. Orr presents this word as though its only detractors come from its implication there is a sex binary, even though as @intersex-ionality discusses here there are other reasons people don't like it. One reason is that the term is considered to originate from outside the intersex community.

Orr never questions the origins of dyadic. But intersex-ionality's post got me wondering if I could track down an textual origin.

So I went to Google Scholar, searched for "dyad" or "dyadic" plus "intersex" or the h-word and kept changing the time period increasingly far back in time. (Initially I just used intersex until I remembered the h-word slur would be more common in older articles 😬.)

I went into this thinking maybe dyadic would be related to how in early intersex studies literature like Critical Intersex (2009) you can see authors trying out terms like "dimorphic" and "dimorphous" that reference sexual dimorphism. (Neither "dyadic" nor "endosex" show up in the book.)

But the earliest works by intersex scholars that invoke dyadic tend to use it in a way that implies to me it has its own origin - e.g. Malatino (2010) talks about "at one pole, the dyad of the dimorphic heterosexual couple and, at the other, the hermaphroditic body" and "the heteronormative promised land of proper dyadic, dimorphic sex" which gives me the impression dyadic has a more sociological origin rather than the biology origin of dimorphic.

This 2010 gender studies article by Mandy Merck that talks about the intersex rights movement was my first solid lead. Merck draws a direct connection between the intersex rights movement and the 1970 book The Dialectic of Sex by Shulamith Firestone. 😯

In the book, Firestone explicitly talks about the "male-female dyad". This book had a fairly big impact when it came out. Firestone was a big-name second-wave radical feminist. And as Merck puts it: "[Firestone's] aim is to release women and men from the culturally gendered[5] dyad of the “subjective, intuitive, introverted, wishful, dreamy or fantastic” and the “objective, logical, extroverted, realistic”[6] into a society undivided by genital differences. This she calls “integration.”" (emphasis mine)

Pushing the search terms to before the 00s, I found I there were some 1980s botanists kinda using "dyad" as an opposite to "hermaphrodite" (example). I don't know how standard this was though, and with Google Scholar it is important to remember that digitization becomes less common the further back you go. 🤷♀️

Judith Butler used "dyadic" in a 1985 article about Foucault's Herculine Barbin.

The Butler article got me searching for more generally - "dyad" or "dyadic" plus "sex-roles male female". I found lots of results using dyadic to talk about female/male sex roles from the 1970s.... and a rather sudden paucity of such articles in the 1960s. 🤔

When I restricted the search to anything before 1970, I get results from symbolic interactionist sociology. I.e. the sociology use of "dyadic" (i.e. any social interaction happening between a pair of individuals).

So looks like dyadic as a sex role thing entered the academic lexicon in the early 70s. Which lines up pretty damn well with The Dialectic of Sex coming out in 1970. 👍️ And indeed, many of the 70s uses of "dyadic" explicitly cite Firestone.

I'm guessing Firestone was probably influenced by the interactionist term. Lots of sociologists were talking about dyadic relationships and/or interactions such as teacher-student, parent-child, husband-wife, etc. In this context, it's not surprising that Firestone would pick dyad as a term to talk about male-female sex roles and interactions.

Other than the 1980s botany articles I didn't actually find much from the pre-2000 biology world, and no leads from the medical literature. This doesn't mean "dyadic" wasn't being used by physicans, just that it isn't showing up in my searches on Google Scholar.

I'm coming out of this with the impression that Merck's got it right to be connecting the intersex-related use of dyadic as originating from the writing of Shulamith Firestone. If anybody knows of competing evidence for an origin, *please* do send it my way as I'd be super interested. But in the absence of other evidence, I'd tentatively say that the term dyadic came out of second wave radical feminism and *not* the intersex community.

#intersex#actually intersex#dyadic#endosex#etymology#queer linguistics#intersex terminology#intersex studies#queer theory#feminism#actuallyintersex

101 notes

·

View notes

Text

Queer lit of the 1800s: Two gay Victorian vampire stories you've probably never heard of

So, I have this post in the works tackling that all-important question: just why are there so many gay vampire stories? But in writing it, what was supposed to be a brief tangent about a couple of little-known m/m vampire stories from all the way back in the late 1800s era… started expanding into something not-so-brief, as such tangents are prone to do.

But what the hell, the internet tells me it's queer history month: clearly the only solution is to give those stories their own post, where my tangent can spin out as far as it likes!

Now, if you know anything about Victorian vampire literature or the lesbian vampire genre, you’ve probably already heard about Carmilla, by Sheridan le Fanu (1872), the world’s very first (known) lesbian vampire story. To this day, it's easily the second best-known and widely adapted tale in all the Victorian vampire canon (after Dracula, obviously) – and it probably deserves to be too.

But this is not a post about Carmilla, because Carmilla is not the only gay-vampire-story written way back in the Victorian era. It's not even the least subtle gay-vampire-tale.

There are (at least) two others, both featuring male/male vampire/human pairings. And whether or not they ‘deserve’ to be remembered in the same breath as Carmilla, they’re both fascinating works in their own rights: Manor, by Karl Heinrich Ulrichs (1884) – one of the world’s first gay activists – and A True Story of a Vampire, by Count Eric Stenbock (1894).

You can read both online. A True Story of a Vampire is long out of copyright and can be found on Gutenberg (Carmilla is too, if you're interested), and many other places. Manor has been translated into English only much more recently, but you can still get hold of it in pdf form, or buy it in ebook format. But if what you really want are some summaries, and/or whole lot of extra context and analysis to go with the stories themselves, I've got you covered below.

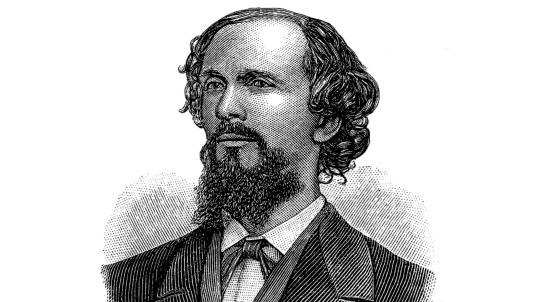

Manor (1884), Sailor Stories, and Karl Heinrich Ulrichs

We’ll start with Manor, since it was published ten years before our other example, and because I’m not quite cruel enough to leave you going "wait, did you really just tell me there was a legit gay activist writing vampire slashfic in his free time way back in the 1880s?" while I ramble on about the other story first. We'll start with the author himself, because his own story is at least as interesting as any fiction he ever published.

Born in Germany in 1825, Karl Heinrich Ulrichs knew from a young age that he was attracted to men. He trained in law, but wisely resigned before he could be fired in 1854 when his proclivities came to the attention of his superiors. Most in his position would've redoubled their efforts to hide; Ulrichs spent the next several years joining societies dedicated to science and literature and developing his own theories about non-hetero orientations, before officially coming out to his family in 1862.

He was just getting started. By 1867, he was ready to come out to the whole world.

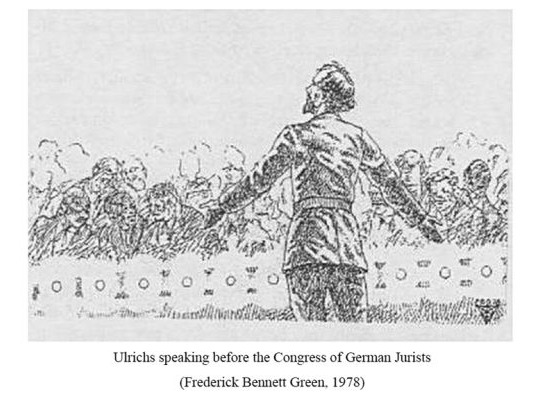

Ulrichs is far from the first gay man to recognise his attraction without shame and find society in like-minded individuals ‒ but he may well be the very first to come out voluntarily and publicly, and advocate for the decriminalisation of homosexuality. And when I say "publicly" what I mean of course is, "in a formal address to the Congress of German Jurists." He was shouted down, but it was still a staggering act of bravery for a man of his time. It would still be a staggering act of bravery in many parts of the world today.

Undaunted by his reception, Ulrichs would also publish a dozen booklets advocating for rights for his community between 1864 and 1879, framing their sexuality as natural, inborn and wholly benign. In 1880, after multiple arrests for his political advocacy, he left Germany for self-imposed exile in Italy, where he would remain until his death in 1895. But it's during this period that he published some poetry, as well as Sailor Stories, a collection of four short stories inspired primarily by Norse mythology, including Manor (which we’ll get to, don’t worry).

Though Ulrichs saw little legal success in his lifetime, through modern eyes, his greatest failure might be only that he was so far ahead of his time. When he began writing and advocating, the word 'homosexuality' didn't even exist yet ‒ he himself used the term 'Urnings' for gay men, eventually coining terms for variations like 'Mannling' and 'Weibling' (gay male equivalent of 'butch' and 'femme') as well. He also came to recognise bisexuality, lesbian attraction, and even intersex conditions, theorising that all resulted from some combination of male and female characteristics developing in the same individual, as the available knowledge on embryonic development suggested might be possible. For a guy with only Victorian era science to work from, that's still remarkably close to the modern consensus today.

Nor did Ulrichs' work die with him. His writings would go on to inspire and be republished by gay rights movements that followed him ‒ including the work and advocacy of Magnus Hirschfeld, who created what may be the world's first trans-affirming clinic. Even in his own time, responses from his own readers show much his work meant to them, reassured at last that they weren't alone.

So how does a German activist from the 1880s find himself publishing gay vampire fiction based on Norse mythology while living in exile in Italy? I only wish I knew. My sources suggest his main goal with Sailor Stories was to publish something that would sell. Unsurprisingly, given the subject matter it seems to have sold very little. Manor is the third of four short tales, and by far the gayest of them all. It's also (IMHO) by far the best, and the most interesting.

Set in a Norwegian fishing village, Manor tells the story of the romance between a 15-year-old boy called Har, and the titular Manor, a sailor 4 years his senior, who rescues Har from the wreck which killed his father. In the days that follow, the pair become close, and Manor takes to swimming across the bay on summer evenings to visit Har at his home. And so they meet whenever they can, until tragedy strikes again, and Manor is killed in a shipwreck near the coast, leaving Har inconsolable with grief.

But this being a vampire story, in the nights after Manor’s death, something is seen swimming across the bay to Har’s home, just as Manor used to do. Har is visited night after night by the spectre of his beloved, who lies beside him in bed, strokes his cheek with cold hands, and kisses him with icy lips, draining his blood from his heart, "like an infant at its mother’s breast." Har himself awaits each night with mixed joy and fear, longing to see Manor again, even in such a form.

As Har weakens, the villagers attempt to trap Manor in his grave by hammering a stake through his body, but he continues to visit Har nonetheless, now sporting a gaping wound in his chest. The villagers return with a new stake, widened at the base like a giant nail, and finally, Manor is restrained in his grave. But it’s too late for Har: weakened and heartsick, he dies, begging only that he should be buried beside his beloved at last. Neither rise again.

Though I can’t speak to how it reads in the original German, in translation, Manor is relayed in largely workmanlike prose. Its tale is short, simple, and sad – but so much about it fascinates me all the same.

(Draugen, Theodor Kittelsen, 1891)

There’s the incorporation of elements you might better recognise from Norse draugr folklore – revenants more typically associated with deaths at sea, or charged with guarding their own graves ‒ but still far more closely related to the vampires of Slavic mythology than most people probably realise. Manor is also one of painfully few stories which clearly recognises what is surely the original purpose of hammering a stake through a vampire’s body: not to kill it, but to hold the creature down and prevent it from leaving its grave. As a hopeless vampire-nerd (I've presented panels at conventions about this stuff, it's dangerous to get me started), I can’t tell you how much I love those aspects of this story.

But above all, Ulrichs’ tale captures what might be one of the oldest and most traditional versions of the folkloric vampire: the spectre of a lost loved one, and the potent mixture of fear and twisted longing thus inspired, that the weight of their loss might drag you down into death to join them. Many ‘real’ tales of vampirism have been inspired by outbreaks of wasting diseases like consumption, working their way through a family, one member at a time. But in Har’s case, it is clearly grief as much as Manor’s physical visits that claims him. He loves Manor so much that he welcomes his lover back, even as a revenant. In his own way, Har too is cursed by Manor’s death to wander the world like the walking dead, until finally reunited with his lover once more.

Nowadays, tragic love stories like this tend to get an eye roll from a lot of the queer community. The old ‘bury your gays’ trope has been done to death, and we’re largely sick of being told that noble suffering is the best we can hope for. But it’s notable nonetheless that Manor’s sexuality has no bearing on his death, and little about the story would change were Har female. It's far from clear if the rest of the village even recognises Har and Manor's love for what it is, let alone whether they'd disapprove ‒ after all, vampires will often go after friends and acquaintances when lovers and family members are exhausted. As such, it’s hard to read the village’s attempts to keep Manor in his grave as a simple matter of prejudice. They're also genuinely trying to save Har's life.

And yet, the way Har keeps the undead Manor’s visits a secret, even begging for the stake to be removed so they can resume, echoes the real experiences of so many gay and lesbian couples far too clearly to be accidental. And however disturbing to a contemporary audience, Har’s willingness to follow his lover to the grave leaves little doubt of the depths of his feelings. To an audience in the 1800s, even the most cliched example of bury-your-gays would be revolutionary.

Did I mention that this story fascinates me? There are layers to this thing.

For completeness, I’ve also read the rest of Sailor Stories (and you can too at the same link). Only one of the other three tales contains any queer romance: the first, Sulitelma, where a boy called Erich falls for a handsome sailor called Harald he meets aboard a spectral storm ship. But there's no happy ending: his sister falls for the same handsome sailor, and shoves Erich overboard to his death to eliminate her competition.

Atlantis, the second story in the collection, is a direct sequel to Sulitelma, but it's even more bizarre. Erich is barely mentioned, and instead we find ourselves reading a tale which I can only summarise as like something I might have found on fanfiction.net back in the early aughts, written by some 14yo trying to straightwash the original material. Here, Harald and some of his fellows go on shore leave to the land of the phoenix, populated by Greek nymphs and Cupid, and mildly comedic hijinx ensue. It is fascinatingly bizarre, but not exactly satisfying as a read (or a sequel).

The final story, The Monk of Sumboe, tells of how two close friends destroy their relationship and themselves with their fixation on the tale of an alluring siren. There's a solid concept in there somewhere, but it's far too short and abrupt to do much with it, and all the characters remain strictly heterosexual. But if there's one thematic detail that ties it to the rest of the collection (beside the many Norse elements), it's that hopeless longing for something others would warn you away from ‒ whether that be a phantom ship, a visit from a vampire lover, or an elusive siren. None of these tales end well for their protagonists, but we're drawn to sympathise with them nonetheless.

I cannot guess what reception Karl Ulrichs expected in publishing this book. Sailor Stories is neither a work that could expect good reception from mainstream audiences or a defiantly-radical queer masterpiece. What did people make of it in its own time? Was it read and cherished by at least a few boys or men like Har and Manor? I’d hope so, but I’ll probably never know.

If you'd like to read more about Karl Ulrichs, I can recommend (among my sources) this New York Times article for a quick overview of his work, or the various work of Michael Lombardi-Nash and Hubert Kennedy (link 2). You can also read the first chapter of his published correspondence online for free.

A True Story of a Vampire (1894), and Count Eric Stenbock

Our second Victorian vampire tale was first published in English, though it was written by a Swedish Count. Like Carmilla in its own day (and quite unlike Karl Ulrichs), both story and author seem to have flown largely under the radar until many years after publication, the queer subtext little noted or commented upon (if at all).

If nothing else though, A True Story of a Vampire aptly demonstrates that at least someone of that era spotted what Carmilla was really about – because he wrote his own version, only about men. Stenbock’s tale is effectively a much shorter, gender-swapped version of Carmilla – but with a larger age gap between vampire and victim lending the story uncomfortable pederastic overtones.

"Vampire stories are generally located in Styria; mine is also," it begins – though I couldn’t name you any vampire story from the era besides Carmilla set there. The narrator, the surviving sister of the vampire’s victim, is called ‘Carmela’, if you needed further proof.

Much like in Carmilla herself, the vampire, Count Vardalek (a Slavic term for vampire) arrives at their house after being forced to seek local hospitality when some convenient ‘accident’ interrupts his travels. There, he bewitches and slowly drains the life from her brother, Gabriel – a boy described in terms variously angelic and fey, a wild thing who befriends wild animals and would rather climb a tree to a window than take the stairs to his own room, but who cleans up beautifully for church – a sublime, cinnamon roll of a creature, far too good for this sinful earth, too pure. Gabriel is a true male equivalent of the likes of Dracula’s Lucy, feminised further still by his youth and innocence. Had a vampire not got him, one can only imagine he’d have eventually have been spirited away by the fairies.

Gabriel and the mysterious Count are drawn to one another immediately. Even as Gabriel wastes slowly away, he greets Vardalek eagerly each time he returns by throwing his arms around his neck and kissing him on the lips. Count Vardalek himself seems to be a vampire of the psychic variety, gaining in health and vitality while Gabriel wilts, merely after spending time in one another’s presence. Vardalek himself seems to genuinely regret Gabriel’s inevitable death, but unlike in Carmilla, there’s no rescue at our conclusion. Gabriel dies, and we’re given no reason to assume he’ll rise again.

To the modern reader, the true horror of this tale lies not with the vampires or even the homoeroticism, but with those uncomfortably pederastic implications. Gabriel can’t be more than twelve years old, his youth and innocence emphasised in his every description. Pains are taken to suggest that Gabriel’s own attraction to Vardalek is as much responsible for his fate as the vampire himself. Gabriel’s father is similarly bewitched by this charming stranger, and never recognises the danger, or the reason for his son’s tragic death. Even the narrator, his loving sister, cannot truly hate Vardalek for taking her brother from her – even when her father dies of grief soon after. Gabriel’s fate seems sealed from the moment the Count enters their home.

But knowing how often real child molesters get away with it, their actions excused or downplayed by their family, their victims accused of ‘seducing’ their abusers and made complicit in their own misery… I can only say that, for my money, A True Story of a Vampire is a very effective horror story in ways the author probably never intended, once you start to question the reliability of its narrator.

It won’t surprise you to learn that the author, Count Eric Stanislaus Stenbock, was a (very) gay man, deeply involved with the gothic and decadent artistic movements of his day. Born to a Swedish Count and an English heiress, Stenbock seems to be remembered less for his writing than for his character. In The Oxford Book of Modern Verse, 1892-1935, W.B. Yeats describes him as a "scholar, connoisseur, drunkard, poet, pervert, most charming of men" ‒ naming Stenbock as an exemplar of the poetic zeitgeist of the age. Notably however, none of Stenbock’s actual poetry is featured in the volume.

Stories about Stenbock are so bizarre that it’s hard to know how much should be believed. Eric Stenbock supposedly travelled with a multitude of exotic pets and a life-sized doll he referred to as his 'son', dabbled in religions ranging from Roman Catholicism to Buddhism, and decorated his dwelling with peacock feathers, oriental shawls, a bronze statue of Eros and a hanging pentagram. One acquaintance once compared him to a 'magnified child': "very fair hair beautifully curled, and a blond, round, blue-eyed face," who paused at the door and "took a little phial out of his pocket, from which he anointed his fingers, before passing them through his locks." But by his thirties, he was already dying of liver disease after years of alcoholism. He passed away at only 35.

Stenbock’s surviving artistic legacy consists of three volumes of poetry and one of prose, with some of those poems including explicit references to Ganymede or male lovers. So how did he escape the same controversy that dogged similar works by other queer creatives of his day, like Oscar Wilde or Walt Whitman – let alone Karl Ulrichs? Well, simple: his work never attracted enough attention to generate real controversy. Stenbock may have been just as much a character as figures like Wilde, but he hadn't nearly the same talent or success.

One last minor biographic detail that may be worthy of note (discovered courtesy of some very poor-quality scans of his one proper biography) is that the youthful Gabriel of A True Story of a Vampire may owe his name to a real Gabriele ‒ a female cousin ten years Stenbock’s junior, whom he would've spent time with in his teens, and seems to have been especially fond of. Whatever the true significance of that name, he'd use it more than once in his fiction: another short story, The Other Side: A Breton Legend, also stars an angelic little boy called Gabriel, with a similar dangerous attraction to the strange. It features some lovely mood and imagery as it sets the scene, but (perhaps as a result of the lack of a suitable model story like Carmilla) it is, in my opinion, a much weaker story overall.

But again, the most disturbing aspect of Stenbock's biography are the hints about his own relationships with much younger men. His second book of poetry, Myrtle, Rue and Cypress, is dedicated to three people: Simeon Solomon (a gay painter of the pre-Raphaelite movement, whom he met at Oxford), Arvid Stenbock, Eric's cousin, and to "the memory of Charles Fowler" ‒ the son of a Clergyman, who died of consumption at only 16.

This enigmatic dedication is all we know about Stenbock's relationship with Fowler. We don't even know how the they met (Fowler seems to have had a relative at Oxford at the same time as Stenbock, but even this is speculation). But that dedication, in a book which will go on to feature poems about the beauty of Ganymede, or explicitly addressed 'To A Boy' (Tis ever a delight, dear, To gaze upon thy face, To love the life within thee, Fair fashioned, full of grace) makes it hard to read Stenbock's feelings as remotely platonic.

It doesn’t help that the same volume includes a poem about an actual vampire, published ten years before A True Story of a Vampire would ever be penned, but with very comparable subject matter:

With slow soft sensual sips Draw the life from the tender spray, And brush from thy soft lithe lips The bloom of thy boyhood away

It's worth keeping in mind that Stenbock himself would've been only 21 at the time of Fowler's death, and that we don't know whether he ever acted on his attraction (whatever form it may have taken). He may well, as I've seen suggested, have kept his admiration private, idealising the image of the beautiful, dying boy in his final days, in that classic Victorian-gothic way. But it doesn't help that Stenbock's cousin Arvid, from that other dedication in the same book, was 8 years his junior, and that their family apparently disapproved of their relationship as "unnaturally close." Or that another famous Stenbock-associate was Norman O'Neil, a composer whom he met on a London omnibus in 1891, when O'Neil too was only 16. Stenbock was apparently taken by his intelligence and beauty, and would go on to leave him a considerable sum of money in his will. By 1891, Stenbock would've been 31, but his fixations hadn't aged with him.

So how are we to take all this? This was an age where a marriage between a 16-year-old girl and a suitor of Stenbock's age would scarcely have raised eyebrows. Uncomfortable as it may sound today, for many queer youths of the era, a romance with someone older and experienced enough to play mentor may genuinely have represented the safest real option available. There are layers of complicated subtext, meanwhile, in the idea of any gay man of the Victorian era casting himself as a vampiric monster, doomed to ruin the object of their attraction with their very touch. There may be layers more in Stenbock framing his tale as "A true story" before telling us of the misery a foreign Count brought to an innocent family, with his helpless fixation on their youngest child.

It's worth noting also that even in Manor, by Legit Gay Activist Karl Ulrichs, our love story is between a boy of 15 and a man of 19 ‒ an age gap of only 4 years, but large enough at 15 to raise some serious eyebrows. His first story too, Sulitelma, involves attraction between a man and a boy (exact ages unknown). Though Ulrichs explicitly viewed relationships with prepubescent children as reprehensible, he seems to have had no problem with relationships between young teens and much older adults ‒ even printing a story sent in by a reader (details in this article), joyfully recounting how he (the reader) was initiated into the world of male/male love as a 14-year-old by his brother's riding master. Ulrichs saw no reason to disapprove.

To confuse things for anyone looking this up today, google Ulrichs, and you'll find a number of online articles claiming that his own first experience involved being sexually assaulted by a riding instructor when he was only 14. This is wrong on multiple fronts: not only is the story related by Ulrichs as a positive experience, it wasn't even Ulrichs it happened to. No, shit like this would not be okay if it happened today (and frequently wasn't then), but we don't help ourselves by distorting the stories told by our queer forebears to fit modern expectations.

But none of that surrounding context makes the youth of the day any less vulnerable to predation, or Stenbock's fixation on youthful beauty less creepy. Today, no evidence remains to help us guess whether idealising the beauty and innocence of youth was the greatest of Stenbock's actual crimes, or the least of them. Anything is possible.

In brief: welcome to the joy of trying to reconcile the complicated place of pederasty in queer history! I'm afraid you can look forward to seeing a lot of it from here on back.

A True Story of a Vampire is not a bad work of fiction by any means. There are some lovely descriptions and entertaining turns of phrase, and the horror is certainly effective. It may even be considerably more readable than Carmilla to many, simply for being so much shorter. But how you feel about it is really going to be up to you.

One last digression about Carmilla and Christabel

There’s one additional work that I’ve once or twice seen listed as an even earlier queer vampire tale: Samuel Coleridge’s unfinished poem Christabel (1800) – the only problem being there’s no vampire in the story (and how queer it is may be questionable too).

Like Carmilla, Christabel tells of a Baron’s daughter (the titular Christabel) who comes upon a mysterious stranger in apparent distress (Geraldine) and invites her into her home. We never learn what kind of being Geraldine truly is (three further parts were planned in addition to the two that were completed), but when she undresses, Christabel spies something that horrifies her, remembering it later with the words "Again she saw that bosom old / Again she felt that bosom cold." But under Geraldine’s spell, Christabel’s recollection of this incident comes and goes, and Geraldine has soon bewitched her father too.

All ‘evidence’ that Geraldine was intended to be a vampire rests on such details as Geraldine having to be carried past an iron gate into the house, much as vampires have to be invited in – but that particular vampire trope wasn’t actually codified until a solid century later (like most vampire-tropes, we have Stoker's Dracula to blame). The idea that Geraldine has the cold, shrivelled body of the undead and revives herself on Christabel’s blood is a perfectly valid reading, but the more obvious interpretation would be that she’s some manner of shapeshifting fairy creature, weakened by the iron of the gateway, not the entrance to Christabel’s home. The aristocratic literary vampire had existed for over 40 years and appeared in numerous works of fiction by Carmilla's day; but Christabel predates the origins of the genre a solid two decades. For Coleridge to have come up with the idea independently seems vanishingly unlikely.

I mention Christabel here partly for completeness, but mostly to bring us back around to the greater family of Carmilla, which is still legitimately the first known queer vampire story. Though far better known than any other story discussed here today, how it came about is perhaps the most mysterious.

Sheridan le Fanu was a prolific writer, but I don’t know of any other story he’s penned with subtext like Carmilla's (and I’m not quite invested enough to read all of the rest to check, though someone totally should so I don't have to). Le Fanu was married, and had children, and that's all I can discover about his personal life. Was he some shade of queer himself? Did he have connections to anyone who was? Did he even realise what he was writing with Carmilla? Nothing I’ve read about him provides any answers. Nor can I tell you how many readers spotted the subtext it the story was first published. In its own time, it caused no great scandal, nor even seems to have garnered much attention (by contrast, Byron & Polidori's The Vampyre caused an uproar when it was published in 1819, mostly thanks to Byron's established fame and debates over its true authorship). It took until well into the 20th Century for it to obtain the reputation it has today.

But I’m sure it’s no coincidence that it was Carmilla that spoke to Stenbock enough that he chose to retell it. And while A True Story of a Vampire is still the only other vampire story of the era set in Styria, there was almost another one: Dracula, at least Stoker’s early plans for the novel. Styria also remains part of the unused prequel chapter later published as Dracula’s Guest. The setting isn’t the only detail Stoker nearly-borrowed from Carmilla either, my favourite example being the weird schedule by which both she and Dracula seem to have to be in bed in their coffins at dawn each day, both apparently helpless and immobile in sleep, though both are also repeatedly seen up and about later in the day. Neither tale offers any real explanation.

Have I mentioned lately that Stoker, too, was almost certainly some shade of gay?

Now, the fact that two different queer writers both found Carmilla so very inspiring – and would even both publish their own works of vampire literature within five years of one another – isn’t much to go on, in trying to establish what a story like Carmilla might’ve meant to England’s queer population some twenty years after it was written. Maybe Carmilla was being eagerly passed around London’s own Uranian gothic societies at the time. Or maybe two different men happened upon it by chance in wholly different circumstances, and took very different things from reading it. Maybe Stoker didn’t even notice the queer subtext himself. But I can’t help but wonder if just maybe, there's something more than coincidence at work here.

Carmilla the vampire is an explicitly villainous character, her victim confused and unwilling. But she remains one of the most complex and sympathetic vampires of her era. And perhaps, to a community who had never seen Ulrichs’ writing published in their own language, and might never see themselves represented in fiction except as monsters buried in layers of protective subtext, that still meant something to readers like Stenbock, and Stocker, and who knows how many others.

In short, maybe old, gay vampire stories like these really are worth remembering. I'll leave that one up to you.

#queer history#vampires#Dracula#Manor#Karl Heinrich Ulrichs#A True Story of a Vampire#Count Eric Stenbock#Carmilla#gay vampire stuff

79 notes

·

View notes

Text

Respect Neo-Pagans and Our Gods!

Although they probably will never see it (or care), this post is meant for Hollywood, Netflix, Marvel and all other industries and streaming platforms that are hosting shows based on but twisting pagan or polytheist "mythology" or ancient religions such as Gods of Egypt, Immortals, Clash of the Titans, Thor: Love and Thunder, DT17, Supernatural, Kaos, Twilight of the Gods, Blood of Zeus, Percy Jackson, Xena: Warrior Princess, The Chilling Adventures of Sabrina, Record of Ragnarok, American Gods, Lore Olympus, and God of War games, etc.

The trend of creating content that demonizes, humiliates, or insults our Gods is upsetting and unfair. Creative and artistic license is one thing, but it's a double-standard for content about the monotheistic god or religions to be treated with respect even when under academic criticism while are ours are depicted as one-dimensional, villainized and humiliated. We are asking for that same respect.

Yes, content about any kind of "mythology" is fun, but the modern world needs to please remember that these were and still are RELIGIONS to many people around the world, myself included.

People worshipped these Gods, listened to their stories around the fire, married under their vows, raised their children, went to war, and but also built magnificent structures, wrote literature, prayed in their temples, and many more!

In fact, we still have vestiges of their worship! The names of the months and days of the week in the Western world come from Roman or Norse/Germanic Gods, the Olympic Games were originally dedicated to Zeus, the Hippocratic Oath was originally a prayer offered to Apollo, people from all over the ancient world visited the shrine and oracle at Apollo's Delphi, and many more examples.

And while yes, sometimes people were sacrificed to some pagan Gods (not so much the Greeks or Romans), but are we really going to pretend that many more people haven't died in the name of Christianity or Islam??

Lord Zeus wasn't just some womanizer, he was also King of the Gods, Father of Gods and Humans, the God of Hospitality, Oaths, Lightning, Law, Order, Authority, Monarchy, etc.

This was also Lord Zeus of the ancient Greeks:

This was also Lord Odin of the ancient Norse:

This was also Lady Hera of the ancient Greeks:

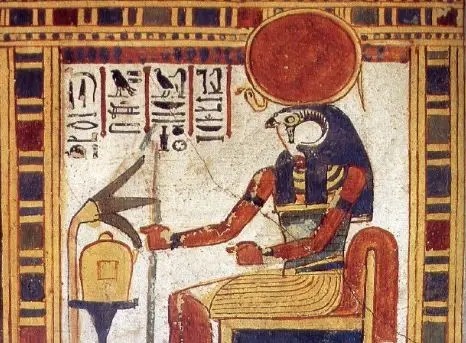

This was also Lord Ra of the ancient Egyptians:

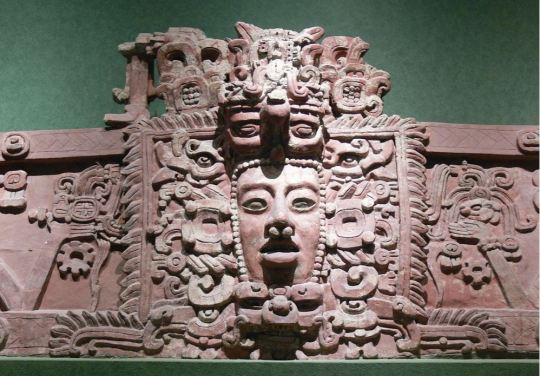

This was also Lord Huracan of the ancient Maya:

Even if you personally don't worship these Gods, at least respect the fact that your ancestors did. Imagine if 100-200 years from now your descendants start making movies and shows that demonize or humiliate Yahweh, Jesus, Allah and Mohammed, etc.!

In fact, neo-paganism is the fastest growing religion in the United States: https://commonwealthpolicycenter.org/paganism-is-americas-fastest-growing-religion/#:~:text=Paganism%20is%20one%20of%20the,a%20broader%20form%20of%20paganism.

Members of Ásatrù, heathen religion of Iceland, honoring the Norse Gods:

Members of Hellenism, honoring the ancient Greek Gods:

Members of my religion, Nova Roma, honoring the ancient Roman Gods:

Traditional African religion:

Traditional Maya religion:

Members of Wicca at Stonehenge, the biggest Neo-Pagan religion in the world with 3-5 million practioners worldwide!

Our Gods are our RELIGION, not just your "mythology!" And both They and we, their followers, deserve the same respect you expect for your religions.

And they at least would never condemn you to an eternal fiery pit simply for not believing in them, unlike some other god I could mention.

They are here. We are here. They exist. We exist. And we are not going anywhere.

#pagan#paganism#mythology and folklore#roman polytheism#hellenic pagan#roman paganism#norse paganism#greek gods#roman gods#wicca#respect all faiths#coexistence#religion#religous themes

87 notes

·

View notes

Note

sorry if you've answered this before, and i hope you don't mind me asking, how do you know so much about computers and what seems to me like everything in the world? how did you become so knowledgeable? it's amazing

i just know a little about a lot of things and I probably have a fair number of things that I've dug into more than most people and less than people who actually focus on that stuff! It's kind of an illusion!

I do know a lot about computers and that's because I've worked at a computer company for 12 years and have been deep into a computery subculture for about 20 years - I do genuinely know a lot about consumer computers. That I'll own and that's experience.

I know a fair amount about literature because I've got a degree in it!

I know a fair amount about journalism because I've got most of a degree in it and I worked with journalists for a long time!

I know a fair amount about nutrition because I've got most of a degree in it and because I've been focused on reading a lot about nutrition for more than a decade because of my own food issues!

But mostly I'm just someone who falls down rabbitholes and has a decent ability to recall what I find when I run down them.

Also I get curious about things and will just go. Experience them.

Like at some point i came across a site for people who own and use RealDolls and I got interested in learning more. The site required an application because they didn't want people just trolling so I applied and I ended up reading through the whole site and reading the magazines they sent out for years after because it was just interesting. The way these guys bought clothes or compared repair techniques and cleaning techniques, the way they constructed identities for their dolls - it was all interesting! So now I know about the proper way to store a RealDoll and how their skeletons are put together and the best way to prevent rips or clean inserts.

Now imagine that with everything.

I got interested in quack medicine so I ended up reading the entire back catalogs of quackwatch and science-based medicine.

I got interested in the history of aspartame as a scare-word and I ended up reading a couple of books, SEVERAL entire blogs with decades-long runs, purchasing a military magazine from the 90s, and submitting a FOIA request.

But, like. I don't own a RealDoll or work in that industry. I am not a medical professional. I am not a chemist who works with aspartame. So I get these weird little collections of information where I know what *seems* like a lot to someone who hasn't looked into it but I know a lot less than someone who has taken the time to actually dedicate themselves to that topic.

And sometimes it's a years-long dive and sometimes it's a months-long dive and sometimes it's a few hours of me digging online until I feel satisfied with what I've learned and I never come back to it, but I've got three more talking points than your average joe at a party would.

(Also though I've attended various colleges at various levels for ten-ish years now and I've taken probably more college-level classes on a lot of subjects than most people have because I've now spent several years just kind of kicking around at community colleges and deciding that a cartooning class sounds fun or that a mesoamerican art class fills certain transfer requirements or that I might as well brush up on spanish, french, and german. Access to low-cost college classes in california is a big part of this, and having the time and money to take classes while i'm working is something that I've been very lucky with)

I've also worked pretty much continuously since I was 18, sometimes holding multiple jobs at once, and I know a lot of interesting people who do a lot of interesting things and I ask them about their interesting experiences and if they offer me a chance to go do cool shit with them, like launch a high altitude balloon or blow up some dynamite that's about to expire or join a band, I do it!

I was also one of those kids who had no friends and spent too much time at the library so I'd do things like read through medical textbooks or pull a book of home chemical formulas out of the trash and read it or take it into my head that I was going to read all of Shakespeare before I got to high school so I was a really annoying twelve-year-old and that kind of thing never really let up.

I don't know! I don't think it's that unusual and I think most people do this kind of thing I just happen to have less focus than a lot of people and talk a lot more.

272 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hi friends! Inspired by @librarycards I wanted to make a post celebrating Women in Translation Month! Anglophone readers generally pay embarrassingly little attention to works in other languages, and that's even more true when it comes to literature by women, so I will jump at any chance to promote my faves 🥰 Here are some recs from 9 different languages! Also, I wrote this on my phone, so apologies for any typos or errors!

1. Trieste by Daša Drndić, trans. Ellen Elias-Bursać (Croatian): An all-time favorite. Much of Drndić's work interrogates the legacy of atrocities in Europe, particularly eastern Europe. Trieste is a haunting contemplative novel centered on an elderly Italian Jewish woman whose family converted to Catholicism during the Mussolini era and were complicit in the fascist violence surrounding them in order to protect themselves.

2. Cursed Bunny by Bora Chung, trans. Anton Hur (Korean): A collection of short stories that are difficult to classify by genre–speculative fiction in the broadest sense. The first story is about a monster in a woman's toilet, which sounds impossible to pull off in a serious, thought-provoking manner, but Chung does so easily—these are the kind of stories that are hard to explain the brilliance of secondhand.

3. Sweet Days of Discipline by Fleur Jaeggy, trans. Tim Parks (Italian; Jaeggy is Swiss): Another all time favorite! The cold, sterile homoerotic girls' boarding school novella of your dreams.

4. Toddler-Hunting and Other Stories by Taeko Kono, trans. Lucy North (Japanese): I think I read this in one sitting. Incredibly unsettling—these stories will stay with you. They often focus on the unspoken psychosexual fantasies underscoring mundane daily life.

5. The Complete Stories by Clarice Lispector, trans. Katrina Dodson (Brazilian Portuguese): I think Lispector is the best known writer here, so she might not need much of an introduction. But what a legend! And this collection is so diverse—it's fascinating to see the evolution of Lispector's work.

6. Our Lady of the Nile by Scholastique Mukasonga, trans. Melanie L. Mauthner (French; Mukasonga is Rwandan): Give her the Nobel! Mukasonga's books, at least the ones available in English, are generally quite short but so impactful. Our Lady of the Nile is a collection of interrelated short stories set at a Catholic girls' boarding school in Rwanda in the years before the Rwandan genocide. These stories are fascinating on many levels, but perhaps the most haunting element is seeing how ethnic hatred intensifies over time—none of these girls would consider themselves particularly hateful or prejudiced, but they easily justify atrocities in the end.

7. Extracting the Stone of Madness: Poems 1962-1972 by Alejandra Pizarnik, trans. Yvette Siegert (Spanish; Pizarnik was Argentinian): Does anyone remember when my url was @/pizarnikpdf... probably not but worth mentioning to emphasize how much I love her <3 Reading Pizarnik is so revelatory for me; she articulates things I didn't even realize I felt until I read her words.

8. Flight and Metamorphosis: Poems by Nelly Sachs, trans. Joshua Weiner (German): Sachs actually won the Nobel in the 1960s, so it's surprising that she's not better known in the Anglosphere. Her poems are cryptic and surreal, yet deeply evocative. Worth mentioning that this volume is bilingual, so you can read the original German too if you're interested.

9. Frontier by Can Xue, trans. Karen Gernant and Chen Zeping (Chinese): Can Xue is another difficult-to-classify writer in terms of genre. Her short stories are often very abstract and can be puzzling at first. I think Frontier is a great place to start with her because these stories are interconnected, which makes them a bit more accessible.

83 notes

·

View notes

Text

Welcome to German Literature Month XIV November 2024

Welcome to German Literature Month XIV Hopefully shelves have been scoured, reading material has been chosen, and everyone has a reading list for #germanlitmonth. Remember anything that was originally written in German can be read during #germanlitmonth. This year books written in other languages, provided they are about Franz Kafka or inspired by him can be read during Kafka Reading Week…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

"He had already been so long in the world..." #awholelife #germanlitmonth #novnov23

My second read for German Lit Month is again a book which also qualifies for Novellas in November; and appropriately enough it was a very kind gift from the host of GLM, Lizzy from Lizzy’s Literary Life (Volume 2). If you saw my end of October round-up, you’ll know that we had a lovely meet up and book shop when I visited Edinburgh last month, and whilst in an Oxfam Bookshop, she stumbled across…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

A Nazi rally held in Madison Square Garden, February 20th 1939

* * * *

LETTERS FROM AN AMERICAN

October 21, 2024

Heather Cox Richardson

Oct 22, 2024

On Saturday, September 7, Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump predicted that his plan to deport 15 to 20 million people currently living in the United States would be “bloody.” He also promised to prosecute his political opponents, including, he wrote, lawyers, political operatives, donors, illegal voters, and election officials. Retired chair of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Mark Milley told journalist Bob Woodward that Trump is “a fascist to the core…the most dangerous person to this country.”

On October 14, Trump told Fox News Channel host Maria Bartiromo that he thought enemies within the United States were more dangerous than foreign adversaries and that he thought the military should stop those “radical left lunatics” on Election Day. Since then, he has been talking a lot about “the enemy from within,” specifically naming Representative Adam Schiff and former House speaker Nancy Pelosi, both Democrats from California, as “bad people.” Schiff was the chair of the House Intelligence Committee that broke the 2019 story of Trump’s attempt to extort Volodymyr Zelensky that led to Trump’s first impeachment.

Trump’s references to the “enemy from within” have become so frequent that former White House press secretary turned political analyst Jen Psaki has called them his closing argument for the 2024 election, and she warned that his construction of those who oppose him as “enemies” might sweep in virtually anyone he feels is a threat.

In a searing article today, political scientist Rachel Bitecofer of The Cycle explored exactly what that means in a piece titled “What (Really) Happens If Trump Wins?” Bitecofer outlined Adolf Hitler’s January 30, 1933, oath of office, in which he promised Germans he would uphold the constitution, and the three months he took to dismantle that constitution.

By March, she notes, the concentration camp Dachau was open. Its first prisoners were not Jews, but rather Hitler’s prominent political opponents. By April, Jews had been purged from the civil service, and opposition political parties were illegal. By May, labor unions were banned and students were burning banned books. Within the year, public criticism of Hitler and the Nazis was illegal, and denouncing violators paid well for those who did it.

Bitecofer writes that Trump has promised mass deportations “that he cannot deliver unless he violates both the Constitution and federal law.” To enable that policy, Trump will need to dismantle the merit-based civil service and put into office those loyal to him rather than the Constitution. And then he will purge his political opponents, for once those who would stand against him are purged, Trump can act as he wishes against immigrants, for example, and others.

Ninety years ago, as American reporter Dorothy Thompson ate breakfast at her hotel in Berlin on August 25, 1934, a young man from Hitler’s secret police, the Gestapo, “politely handed me a letter and requested a signed receipt.” She thought nothing of it, she said, “But what a surprise was in store for me!” The letter informed her that, “in light of your numerous anti-German publications,” she was being expelled from Germany.

She was the first American journalist expelled from Nazi Germany, and that expulsion was no small thing. Thompson had moved to London in 1920 to become a foreign correspondent and began to spend time in Berlin. In 1924 she moved to the city to head the Central European Bureau for the New York Evening Post and the Philadelphia Public Ledger. From there, she reported on the rise of Adolf Hitler. She left her Berlin post in 1928 to marry novelist Sinclair Lewis, and the two settled in Vermont.

When the couple traveled to Sweden in 1930 for Lewis to accept the Nobel Prize in Literature, Thompson visited Germany, where she saw the growing strength of the fascists and the apparent inability of the Nazi’s opponents to come together to stand against them. She continued to visit the country in the following years, reporting on the rise of fascism there, and elsewhere.

In 1931, Thompson interviewed Hitler and declared that, rather than “the future dictator of Germany” she had expected to meet, he was a man of “startling insignificance.” She asked him if he would “abolish the constitution of the German Republic.” He answered: “I will get into power legally” and, once in power, abolish the parliament and the constitution and “found an authority-state, from the lowest cell to the highest instance; everywhere there will be responsibility and authority above, discipline and obedience below.” She did not believe he could succeed: “Imagine a would-be dictator setting out to persuade a sovereign people to vote away their rights,” she wrote in apparent astonishment.

Thompson was back in Berlin in summer 1934 as a representative of the Saturday Evening Post when she received the news that she had 24 hours to leave the country. The other foreign correspondents in Berlin saw her off at the railway station with “great sheaves of American Beauty roses.”

Safely in Paris, Thompson mused that in her first years in Germany she had gotten to know many of the officials of the German republic, and that when she had left to marry Lewis, they offered “many expressions of friendship and gratitude.” But times had changed. “I thought of them sadly as my train pulled out,” she said, “carrying me away from Berlin. Some of those officials still are in the service of the German Government, some of them are émigrés and some of them are dead.”

Thompson came home to a nation where many of the same dark impulses were simmering, her fame after her expulsion from Germany following her. She lectured against fascism across the country in 1935, then began a radio program that reached tens of millions of listeners. Hired in 1936 to write a regular column three days a week for the New York Herald Tribune, she became a leading voice in print, too, warning that what was happening in Germany could also happen in America.

In an echo of Lewis’s bestselling 1935 novel It Can’t Happen Here, she wrote in a 1937 column: “No people ever recognize their dictator in advance…. He always represents himself as the instrument for expressing the Incorporated National Will. When Americans think of dictators they always think of some foreign model. If anyone turned up here in a fur hat, boots and a grim look he would be recognized and shunned…. But when our dictator turns up, you can depend on it that he will be one of the boys, and he will stand for everything traditionally American.”

In less than two years, the circulation of her column had grown to reach between seven and eight million people. In 1939 a reporter wrote: “She is read, believed and quoted by millions of women who used to get their political opinions from their husbands, who got them from [political commentator] Walter Lippmann.” The reporter likened Thompson to First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, saying they were the two “most influential women in the U.S.”

When 22,000 American Nazis held a rally at New York City’s Madison Square Garden in honor of President George Washington’s birthday on February 20, 1939, Thompson sat in the front row of the press box, where she laughed loudly during the speeches and yelled “Bunk!” at the stage, illustrating that she would not be muzzled by Nazis. After being escorted out, she returned to her seat, where stormtroopers surrounded her. She later told a reporter: “I was amazed to see a duplicate of what I saw seven years ago in Germany. Tonight I listened to words taken out of the mouth of Adolf Hitler.”

Two years later, In 1941, Thompson returned to the issue she had raised when she mused about those government officials who had gone from thanking her to expelling her. In a piece for Harper’s Magazine titled “Who Goes Nazi?” she wrote: “It is an interesting and somewhat macabre parlor game to play at a large gathering of one’s acquaintances: to speculate who in a showdown would go Nazi,” she wrote. “By now, I think I know. I have gone through the experience many times—in Germany, in Austria, and in France. I have come to know the types: the born Nazis, the Nazis whom democracy itself has created, the certain-to-be fellow-travelers. And I also know those who never, under any conceivable circumstances, would become Nazis.”

Examining a number of types of Americans, she wrote that the line between democracy and fascism was not wealth, or education, or race, or age, or nationality. “Kind, good, happy, gentlemanly, secure people never go Nazi,” she wrote. They were secure enough to be good natured and open to new ideas, and they believed so completely in the promise of American democracy that they would defend it with their lives, even if they seemed too easygoing to join a struggle. “But the frustrated and humiliated intellectual, the rich and scared speculator, the spoiled son, the labor tyrant, the fellow who has achieved success by smelling out the wind of success—they would all go Nazi in a crisis,” she wrote. “Those who haven’t anything in them to tell them what they like and what they don’t—whether it is breeding, or happiness, or wisdom, or a code, however old-fashioned or however modern, go Nazi.”