#asian american history

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Chinese Miners at the head of the Auburn Ravine, c. 1852.

As the number of Chinese miners grew, ugly episodes of racial violence became increasingly common. (Source: Huntington Library)

Learn more in STRANGERS IN THE LAND: Exclusion, Belonging, and the Epic Story of the Chinese in America by Michael Luo (Now available for preorder | on sale 4/29/25)

#history#nonfiction#reading#mining#asian american history#historical nonfiction#asian american#mike luo#michael luo#yu and me books#yu and me#indie bookstore#indie preorder

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

In MDZS (and much of other Chinese media), we see our main characters use instruments as a way to advance the story. While the use of instruments, especially in xianxias, stems from Taoist and traditional spiritual beliefs, the presence of instruments as a method of change is a very significant phenomenon in Asian diasporas. Like how chengqing became a symbol for the yiling laozu’s defiant presence, Asian American diasporas have used music as a way to initiate communal change.

Because of this, I wanted to start a short blog series exploring different musical movements used in Asian diaspora history !! Music, culture, and politics are huge interests of mine so… hehe.

-----

1– A Grain of Sand: Music for the Struggle of Asians in America

Released 1970’s in response to the decade’s ongoing Asian American Movement

One of the most prominent examples of Asian American musical movements and recognized as the first album of “Asian American music,” Chris Kando Iijima, Nobuko JoAnne Miyamoto, and William “Charlie” Chin created songs to demonstrate the struggles of Asian Americans at the time. From songs like We are the Children, which explained the artists’ ancestry and “othered” identities in America, and Yellow Pearl, a reference to the Yellow Peril and societal oppression, the album challenged Asian American oppression and vocalized emotional struggles faced by diasporas throughout the nation.

Musically, traditional instruments (like the oh-so-familiar dizi!) were occasionally woven into an American, jazz-and-folk style of song.

In addition to connecting to their own culture, these artists used their music as a way to protest against war and advocate for ethnic studies. In pan-asian ethnic enclaves (ie. Chinatowns), they organized in support of locals, small businesses, and established art workshops and social service centers. They went on to inspire other artists through live performances, such as filmmaker Tadashi Nakamura, and each artist would go on to establish their own projects. For Miyamoto, it would be the Great Leap Inc., a community performance organization in Los Angeles. For Chin, it would be New York’s Chinatown History Project, which would become the Museum of Chinese in the Americas. And for Iijima, he would go on to become a lawyer for Native Hawaiian rights.

#mdzs#mxtx#mo dao zu shi#wei wuxian#grain of sand#asian american#american history#music history#asian american music#asian music#asian american movement#asian american history

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

So this series of posts reminded me of something that really fucking bothers me. While the 442nd are rightfully lauded for their spectacular accomplishments, I’d argue that a different unit of nisei contributed even more to the American war effort.

I’m talking, of course, about the Japanese-American veterans of the Military Intelligence Service (MIS).

Let’s take a moment here and do a little exercise in military logistics. It’s the 1940s and you’re in charge of running the American war effort against the Axis Powers. You want to know as much as possible about your enemy, right? The more you know about their troop movements, strategies, supply lines, morale, etc., the better you’ll be able to counter their efforts and stage attacks. Now, you and your allies have some pretty sharp fellas working on cracking your enemies’ codes, so you’ve actually got a big ol’ pile of communications to go through. There’s just one problem: your enemies don’t use English.

But hey! You’re America! Land of immigrants and all that! Don’t speak German? There’s plenty of German-Americans who do! Don’t speak Italian? There’s plenty of Italian-Americans who do! Don’t speak Japanese? HMMM. WHERE DO YOU THINK YOU’RE GOING TO FIND A BUNCH OF JAPANESE SPEAKERS???

These excerpts come from American Patriots, an anthology of stories from the MIS interpreters put out by the Japanese-American Veterans Association of Washington DC. I know it’ll take a minute, but I want you to read every goddamn word. I *NEED* you to feel the weight of those events:

The United States military was crippled by its lack of Japanese interpreters. They knew they were crippled even before Pearl Harbor. To fix that handicap, they recruited men from literal concentration camps. Not only did those men rise to the occasion, but other men from other camps volunteered to serve. This country did not deserve their loyalty, but they still served. And no one fucking talks about them.

Wow! That’s amazing! Surely there’s a bunch of movies and books and documentaries about these guys, right? America loves a good patriotic WWII story!

There's almost no media about the Japanese translators. American Patriots is the only book I’ve come across in real life, and that only happened because I stopped by the Japanese American Veterans Association's booth at the Cherry Blossom Festival. There's a few history books, mostly by Japanese-American groups, and a couple of articles, but that’s about it. They're all pretty old (American Patriots came out in 1995). Nobody fucking talks about the nisei translators.

The next time you bring up the heroic service of the 442nd Regiment, bring up the heroic service of the Japanese translators of the MIS. The next time you discuss the contributions of POCs to the US military, I want you to discuss the Japanese translators. The next time you get angry about how Asian-Americans are ignored by American culture, I want you to get angry about the Japanese translators. This is an important piece of American history, and it’s always overlooked, and I’m sure we all know why. Let’s change that.

Further reading:

Nisei Linguists from Washington in World War II

Military Intelligence Service

JAVA's compilation of nisei members of the MIS Hall of Fame

JAVA's research archive

#History#Japanese americans#Nisei#asian americans#American history#japanese american history#Asian American history#Military history#did i mention that the nisei founded the DLI?#because they founded the DLI

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Never Again is Now" ~ an alley mural by Erin Shigaki, 2018, in Seattle, Washington (2/14/2025)

#washington#seattle#mural#mural art#street art#erin shigaki#seattle artist#women artists#asian american art#asian american history

19 notes

·

View notes

Note

Re: ethnic cleansing, sincere question, would the US government Japanese internment policy count as ethnic cleansing? I know they were still within US borders, but they were forcibly removed from their property and relocated with no legal recourse. Since death isn't the main goal of cleansing, sounds to me like this could count.

I’m a bit out my depth with regard to this particular subject, so I reached out to my girl Dr. Stephanie Hinnershitz, who has published extensively on the topic, and has another book on it set to be released by the University of Kansas Press in 2026.

Here's what she said:

“I would not categorize it as ethnic cleansing, no; particularly not in comparison to US indigenous policies, which are considered ethnic cleansing in many cases. (And Japanese Americans did actually have legal recourse, eventually; it’s how they could appeal to the Supreme Court. They didn’t as far as the rights of other internees to appear before loyalty review boards but if they didn’t have legal recourse you wouldn’t have had the big court cases). For comparison to what could be considered ethnic cleansing, see: all the state-condoned attacks on Chinese migrant communities in the 19th century in the West.”

She adds:

"I am in no way saying that the internment of Japanese Americans wasn't bad; just that it's not an example of US ethnic cleansing policy."

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

In truth, Spanish presence was minimal outside of a handful of urban settlements. Spain's outlandish claim to the entirety of the Pacific was actualized almost solely through the passage of a couple of ships sailing in either direction each year. Strictly speaking, the Spanish presence in the Pacific during most of the colonial period existed within a narrow navigational corridor, a transpacific space "as shallow as the amount of seawater displaced by the weight of Iberian sailing vessels." In the words of [Christina H. Lee] and [Ricardo Padrón], "Spanish Pacific studies begins by recognizing that Spain's presence in the Pacific was always slim, tenuous, and contested."

Despite the extremely limited scope of the Spanish encounter with the Pacific, it sufficed to facilitate "an unprecedented global mestizaje [intermingling and intermixture]" in the movement of thousands of free and enslaved Asians to the Americas for the first time. During their 250 years of operation, the Manila galleons confronted the most challenging seafaring conditions of their era to ferry merchandise and people between Cavite in the Philippines and Acapulco in Mexico. The survivors of this arduous journey were forever marked by it.

The people disembarking in Mexico's torrid Pacific port had come from Gujarat to the southwest, Nagasaki to the northeast, and everywhere in between. Most sailors and free migrants were born on Luzon in the Philippines, while captives had often been ensnared throughout the Philippines or ... by Portuguese enslaving operations in the Indian Ocean World. Smaller concentrations came from elsewhere in Southeast Asia, Japan, or China.

Excerpt from The First Asians in the Americas: A Transpacific History (2024) by Diego Javier Luis

#mexican history#latin american history#asian history#asian american history#mexico#latin america#x#spanish colonialism#colonialism#mestizaje

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Corky Lee

“This is a video still from a full portrait AR 4k video of the unveiling of the street sign for Corky Lee Way in New York City.” - via Wikimedia Commons

#corky lee#american history#asian american history#asian american activism#photography#photographers#people#activism#activists#nyc#chinatown#new york city#wikipedia#wikipedia pictures#wikimedia commons#mott street#mosco street

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Still wild to me that despite being in the state of Texas, and originally based in Fort Worth (aka "where the west begins"), the National Multicultural Western Heritage Museum (formerly known as the Cowboys of Color Museum) cannot find steady funding or support. Tons of money gets poured into the Stockyards of Fort Worth for tourist trapping, but god forbid the one foundation trying to shed light and focus on providing a fuller picture with inclusion of the lives of Black, Native, Asian, and Latines in the US during the founding of "the American West" get any help. They've had to keep moving locations cause they can't make rent, and they JUST moved again this January to a location in Arlington. It cut cost on rent, but their display space is also now cut.

I hope if you're ever in the DFW, you pay the museum a visit and contribute with your ticket sale. And if you know of anyone who's able to afford it and willing to contribute to their ongoing 100 for $1000 campaign due to relocation and new preservation needs, send them this graphic or this link.

#texas#cowboys#cowboy#history#american history#black history#native history#Mexican american history#asian american history#fort worth#dallas#arlington#anytime i see the topic of cowboys i feel like promoing the museum#they also run rodeos and a hall of fame every year

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

SANDRA DOUGLASS MORGAN // AMERICAN FOOTBALL EXECUTIVE

“She is an American football executive and attorney, who is currently the president of the Las Vegas Raiders of the National Football League. She is the first Black and Asian woman to serve as an NFL team president. Douglass Morgan previously served on the Nevada State Athletic Commission and was the chairwoman of the Nevada Gaming Control Board among other roles.”

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

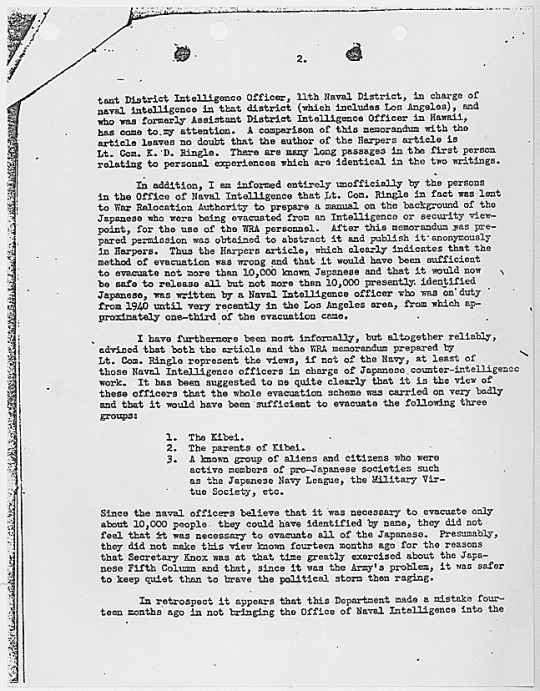

At the beginning of WWII, Naval Intelligence officers concluded that there were around 10,000 Japanese Americans who could pose a threat to the U.S.

Army General DeWitt used his authority to incarcerate 120,000.

U.S. v Korematsu, Exhibit Q, April 30, 1943.

Record Group 21: Records of District Courts of the United States

Series: Criminal Case Files

File Unit: United States v. Korematsu

Transcription:

Edward J. Ennis

Director

Exhibit Q

Department of Justice

Alien Enemy Control Unit

Washington

April 30, 1943

[stamp] DEPARTMENT OF [illegible]

SEP 1[illegible] 1951

DIVISION OF [illegible]

ATTORNEY GENERAL [end stamp]

MEMORANDUM FOR THE SOLICITOR GENERAL

RE: Japanese Brief

Last week with our draft of the [underlined] Hirabayeshi [end underlined] brief I transmitted to Mr. Raum somematerial which I thought he would find helpful in obtaining a background view of the context of this case. In particular, I sent him a copy of Harpers Magazine for October 1942, which contains an article entitled [underlined] The Japanese in America, The Problem and the Solution, [end underline] which is said to be by "An Intelligence Officer". without attempting to summarize this article, it stated among other things that:

1. The number of Japanese aliens and citizens who would act as saboteurs and enemy agents was less than 3,500 throughout the entire United States.

2. Of the Japanese aliens, "the large majority are at least passively loyal to the United States".

3. "The Americanization of Nisei (American-born Japanese) is far advanced."

4. With the exception of a few identified persons who were prominent in pro-Japanese organization the only important group of dangerous Japanese were the Kibei (American-born Japanese predominantly educated in Japan).

5. "The identity of Kibei can be readily ascertained from United States Government records."

6. "Had this war not come along at this time, in another ten or fifteen years there would have been no Japanese problem, for the Issei would have passed on, and the Nisei taken their place naturally in American communities and national life."

This article concludes: "To sum up: The 'Japanese Problem' has been magnified out of its true proportion largely because of the physical characteristics of the Japanese people. It should not be handled on the basis of the [underlined: individual], regardless of citizenship and [underlined: not] on a racial basis." (Emphasis in original.)

I thought this article interesting even though it was substantially anonymous. I now attach much more significance to it because a memorandum prepared by Lt. Con. X. D. Ringle, who has until very recently been Assis-

[handwritten in bottom right corner] #8 [end handwritten]

[page 2]

tant District Intelligence Officer, 1th Naval District, in charge of naval intelligence in that district (which includes Los Angeles), and who was formerly Assistant District Intelligence Officer in Hawaii, has come to my attention. A comparison of this memorandum with the article leaves no doubt that the author of the Harpers article is Lt. Com. K. D. Ringle. There are many long passages in the first person relating to personal experiences which are identical in the two writings.

In addition I am informed entirely unofficially by the persons in the Office of Naval Intelligence that Lt. Com. Ringle in fact was lent to War Relocation Authority to prepare a manual on the background of the Japanese who were being evacuated from an Intelligence or security viewpoint, for the use of the WRA personnel. After this memorandum was prepared permission was obtained to abstract it and publish it anonymously in Harpers. Thus the Harpers article, which clearly indicates that the method of evacuation was wrong and that it would have been sufficient to evacuate not more than 10,000 know Japanese and that it would now be sage to release all but not more than 10,000 presently identified Japanese, was written by a Naval Intelligence officer who was on duty from 1940 until very recently in the Los Angeles area, from which approximately one-third of the evacuation came.

I have furthermore been most informally, but altogether reliably, advised that both the article and the WRA memorandum prepared by Lt. Com. Ringle represent the views, if not of the Navy, at least of those Naval Intelligence officers in charge of Japanese counter-intelligence work. It has been suggested to me quite clearly that it is the view of these officers that the whole evacuation scheme was carried out badly and that it would have been sufficient to evacuate the following three groups:

1. The Kibei.

2. The parents of Kibei.

3. A known group of aliens and citizens who were active members of pro-Japanese societies such as the Japanese Navy League, the Military Virtue Society, etc.

Since the naval officers believe that it was necessary to evacuate only about 10,000 people they could have identified by name, they did not feel that it was necessary to evacuate all of the Japanese. Presumably, they did not make this view known fourteen months ago for the reasons that Secretary Knox was at that time greatly exercised about the Japanese Fifth Column and that, since it was the Army's problem, it was safer to keep quiet than to brave the political storm then raging.

In retrospect it appears that this Department made a mistake fourteen months ago in not bringing the Office of Naval Intelligence into the

[page 3]

controversy. I suppose that the reason that it did not occur to any of us to do this was the extreme position then taken by the Secretary of the Navy.

To have done so would have been wholly reasonable, since by the terms of the so-called delimitation agreement it was agreed that Naval Intelligence should specialize on the Japanese, while Army Intelligence occupied other fields. I have not seen the document, but I have repeatedly been told that Army, before the war, agreed in writing to permit the Navy to conduct its Japanese intelligence work for it. I think it follows, therefore, that to a very considerable extent the Army, in acting upon the opinion of Intelligence officers, is bound by the opinion of the Naval officers in Japanese matters. Thus, had we known that the Navy thought that 90% of the evacuation was unnecessary, we could strongly have urged upon Gen. DeWitt that he could not base a military judgment to the contrary upon Intelligence reports, as he now claims to do.

Lt. Com. Ringle's full memorandum is somewhat more complete than the version published in Harpers and I think you will be interested in reading it. In the past year I have looked at great numbers of reports, memoranda, and articles on the Japanese, and it is my opinion that this is the most reasonable and objective discussion of the security problem presented by the presence of the Japanese minority. In view of the inherent reasonableness of this memorandum and in view of the fact that we now know that it represents the view of the Intelligence agency having the most direct responsibility for investigating the Japanese from the security viewpoint, I feel that we should be extremely careful in taking any position on the facts more hostile to the Japanese than the position of Lt. Com. Ringle. I attach the Department's only copy of this memorandum.

Furthermore, in view of the fact that the Department of Justice is now representing the Army in the Supreme Court of the United States and is arguing that a partial, selective evacuation was impracticable, we must consider most carefully what our obligation to the Court is in view of the fact that the responsible Intelligence agency regarded a selective evacuation as not only sufficient but preferable. It is my opinion that certainly one of the most difficult questions in the whole case is raised by the fact that the Army did not evacuate people after any hearing or on any individual determination of dangerousness, but evacuated the entire racial group. The briefs filed by appellants in the Ninth Circuit particularly pressed the point that no individual consideration was given, and I regard it as certain that this point will be stressed even more, assuming that competent counsel represent appellants, in the Supreme Court. Thus, in one of the crucial points of the case the Government is forced to argue that individual, selective evacuation would have been impractical and insufficient when we have positive knowledge that the only Intelligence agency responsible for advising Gen. DeWitt gave him advice directly to the contrary.

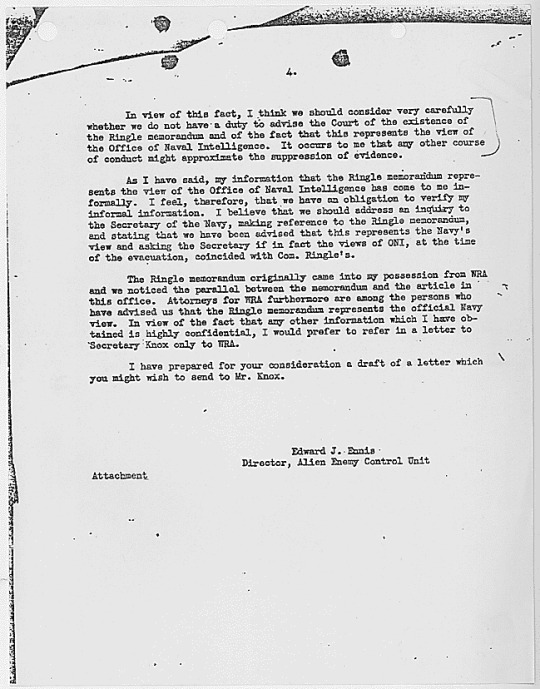

[page 4[

In view of this fact, I think we should consider very carefully whether we do not have a duty to advise the Court of the existence of the Ringle memorandum and of the fact that this represents the view of the Office of Naval Intelligence. It occurs to me that any other course of conduct might approximate the suppression of evidence.

As I have said, my information that the Ringle memorandum represents the view of the Office of Naval Intelligence has come to me informally. I feel, therefore, that we have an obligation to verify my informal information. I believer that we should address an inquiry to the Secretary of the Navy, making reference to the Ringle memorandum, and stating that we have been advised that this represents the Navy's view and asking the Secretary if in fact the views of ONI, at the time of the evacuation, coincided with Com. Ringle's.

The Ringle memorandum originally came into my possession from WRA and we noticed the parallel between the memorandum and the article in this office. Attorneys for WRA furthermore are among the persons who have advised us that the Ringle memorandum represents the official Navy view. In view of the fact that any other information which I have obtained is highly confidential, I would prefer to refer in a letter to Secretary Knox only to WRA.

I have prepared for your consideration a draft of a letter which you might wish to send to Mr. Knox.

Edward J. Ennis

Director, Alien Enemy Control Unit

Attachment

#archivesgov#April 30#1943#World War II#WWII#Japanese American incarceration#Japanese internment#Asian American history#Japanese American history#US v Korematsu

63 notes

·

View notes

Text

Before the discovery of gold, fewer than a thousand hardy inhabitants occupied the windswept settlement of San Francisco. (Source: California Historical Society)

Learn more in STRANGERS IN THE LAND: Exclusion, Belonging, and the Epic Story of the Chinese in America by Michael Luo

(Now available for preorder | on sale 4/29/25)

#asian american#asian american history#mike luo#michael luo#yu and me books#yu and me#indie bookstore#indie preorder#history#nonfiction

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sounds just about white right. I mean, why would you want people to know about the many fucked up aspects of a country’s history? Especially if the government played a very heavy hand in it.

#black history is american history#asian american history#indigenous history#washington post#revisionist history

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Punjabi Rebels of the Columbia River traces the stories of the radical Indian independence organization known as Ghadar and Bhagat Singh Thind’s era-defining US Supreme Court citizenship case. Ghadar sought the overthrow of India’s British colonizers while Thind utilized sanctioned legal channels to do so.

#uwlibraries#history books#asian american history#PNW history#political history#history of india#american history#legal history#british history#colonial history

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

American Gods’ incomplete bibliography (3)

If you want to have access to the full, original bibliography as prepared by Neil Gaiman (it has a lot more info I do not put in my posts - my posts are just summaries and recaps of the original bibliography) you just need to go check Neil Gaiman’s website right here: https://www.neilgaiman.com/works/Books/American+Gods/in/183/?type=Books&work=American+Gods

7) First Nations myths

God is Red: A Native View of Religion

Neil Gaiman considers it a “very readable book about religion from a Native American standpoint” - though he was a bit puzzled by how the middle of the book “wander into Velikovsky”.

The Religions of the American Indians

American Indian Myths and Legends

The mythology of North America

8) Background books

On the Rez

A book about the Oglala Sioux on Pine Ridge Reservation, one of the porrest places in America (at least at the time Neil Gaiman put together his bibliography), and about SuAnne Big Crow, a basketball player.

Confederates in the Attic: Despatches from the Unfinished Civil War

Neil Gaiman bought and tried to read it in preparation for American Gods, but couldn’t get into it... It took him two whole years to get into it again, as he was writing American Gods, and he devoured it.

The Forbidden Zone

Neil Gaiman first read a chapter of this book while doing online research about slaughterhouses. Despite the book being out of print, he managed to obtain a copy from a New Mexico bookstore - and this book ended up shaping and informing American Gods in many ways, both direct and indirect. Neil Gaiman is really sad that it is out of print ; and he points out that he has been a fan of the author, Michael Lesy, ever since another one of his books, “Wisconsin Death Trip”, about painting a darker and disturbing picture of the Wisconsin in frontier times. Wisconsin Death Trip is in fact another one of the books that influenced American Gods: some anecdotes and attitudes from this book ended up being present in the Lakeside parts of the novel.

The Day of the Dead and other reflections

(Of its actual title, The Day of the Dead and other mortal reflections)

Neil Gaiman considers the author one of his favorite essayist alongside David Quammen - and it is from this book that Neil Gaiman “got” Coatlicue.

Stranger from a Distant Shore: A History of Asian Americans

Neil Gaiman used this book to research a lot of stuff that “never worked its way into American Gods”, but that will maybe appear in another book. At least, this is what he writes in the bibliography, but since we are all American Gods fan of modern days, we now know what he referred to in the bibliography: the “Somewhere in America” deleted section about a kitsune ending up in a Japanese internment camp of WWII America.

9) African heritage

As Neil Gaiman says, these are the books he used concerning Mr. Nancy, and “the tale of the twins” (Wututu and Agasu).

A Treasury of Afro-American Folklore + A Treasury of African Folklore, by Harold Courlander

The African Slave Trade, by Basil Davidson

The Slave Trade: The Story of African Slave Trade, 1440-1870

(Of its actual name, “The Slave Trade: The Story of the Atlantic Slave Trade)

Neil Gaiman precises that he took a lot from this book, written by Hugh Thomas, alongside Bullwhip Days (see below) - but he also admitted that he had to downplay what actually happened historically when writing “American Gods” because he didn’t want to turn his scenes into an “atricity exhibition”.

Bullwhip Days: The Slaves Remember - An Oral History

In Neil Gaiman’s words, “Urgent, human narratives and utterly heartbreaking”, as this book is a collection of the testimonies of the last surviving Americans who had been slave, collected in the mid-1930s.

Voodoo in New Orleans

Neil Gaiman explains that this book does not manage to convey the actual feel of the New Orlenas Voodoo, but it is an excellent book when it comes to the history of the “various Maries Laveau or Marie Laveaux”. However, if someone wants a better book by Robert Tallant, they should check Gumbo Yaya (see below)

Gumbo Yaya

Neil Gaiman was offered this book as a gift by Nancy Collins, and he realized he did need it a lot. It is an excellent book covering the folk beliefs, magic and folklore of New Orleans and Louisiana.

Voodoo in Haiti

A “fairly useful and interesting book”, according to Neil Gaiman. He does say that there is a lot of better books about the topic of Haitian voodoo, but he included it in the list because it was the book he used to check stuff when writing American Gods.

#neil gaiman speaks#american gods bibliography#american gods#voodoo#african mythologies#afro american history#history of slavery#native american mythology#american history#asian american history#bibliography#references#books#neil gaiman

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

May is Asian and Pacific American Heritage month so I wanted to make something about it since I haven’t seen many people posting about it.

Specifically I wanted to talk about my job and the significance of the place I work at.

I work for the Angel Island Immigration Station Foundation. We’re dedicated to helping preserve the memory and history of Angel Island.

If you aren’t from California you probably don’t know what or where Angel Island is. Angel Island is an island located in the San Francisco Bay. From 1910-1940 it served as the “Guardian of the Western Gate�� working to exclude and deport Chinese immigrants but later expanding to practically anyone from Asia.

During its time of operation around 500,000 people from 80 countries were held here. They were subjected to invasive medical exams and intensive interviews to prove they were who they said they were.

(Note this image and all other images we have of the medical exams are staged. We know they're all staged because standard procedure was to have immigrants strip completely naked.)

The reason Angel Island exists was because of the 1882 Chinese exclusion act. Immigration officials needed a place to house immigrants who were potentially barred from entering the county.

The Chinese exclusion act barred those who were laborers or “likely public charges,” people who immigration officials assumed would be taking resources from the government.

If you were a student, a merchant, or were directly related to a citizen you could enter the country.

These exemptions lead to a number of Chinese immigrants selling their papers or buying identities. Becoming someone’s so called paper child. Most often it was sons but there are paper daughters and other paper relatives.

Becoming a paper child involves memorizing new names, birthdays, streets, villages and anything immigration officials could use to potentially deport someone.

Here’s a list of real questions immigrants were asked while being detained.

What direction did your doorway face?

How many steps are there to your front door

Who lived in the third house in the second row of houses in your village?

It wasn’t enough for just you to answer though. Your family or whoever was vouching for you to enter the country also had to answer the same questions. If either you or your witnesses answered in a way that was incorrect or simply rubbed officials the wrong way you could be subject for further questioning and deportation.

While immigrants were detained many of them graffitied the walls with their thoughts feelings and assertions. A physical form of their feelings and resistance to their imprisonment. Immigration officials obviously hated this and would paint over and fill in any graffiti they found but ironically because of their efforts to erase this part of the immigration experience it preserved it.

You can visit Angel Island today and still see the poetry that these people carved into the walls today. Here’s a photo I took of one of the easiest to see poems since it had the wood putty taken out of it.

This is the English translation.

Detained in this wooden house for several tens of days, It is all because of the Mexican exclusion law which implicates me. It’s a pity heroes have no way of exercising their prowess. I can only await the word so that I can snap Zu’s whip.

From now on, I am departing far from this building All of my fellow villagers are rejoicing with me. Don’t say that everything within is Western styled. Even if it is built of jade, it has turned into a cage.

I'd also like to highlight one of the many people who came through Angel Island.

This is Karl Yoneda. He was Kibei, an American citizen by Birth but educated in Japan. When he returned to the US he was detained on Angel Island. While he was detained he wrote a diary detailing his frustrations as well as his own poetry.

When he was finally released he moved to LA where he became involved in labor politics changing his name to Karl (he was inspired by Marx).

During WW2, Karl and his son were sent to the Manzanar concentration camp. His wife, Elaine, a white woman joined him out of solidarity refusing to be separated from her family.

Karl strongly opposed the Japanese Imperial Government and volunteered to join the US Military Intelligence Service.

After the war, Karl continued to organize and agitate. He helped organize the first pilgrimage to Manzanar as well as pushed for reparations to Japanese Americans who were imprisoned in the camps.

If you want to learn more about Karl or Angel Island in general, I suggest reading through our exhibit Angel Island Mosaic. It has a bunch of other people on there as well whose stories are just as interesting as Karl's.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

While the "chino/a" label formally racialized diverse ethnolinguistic Asian communities as an undifferentiated monolith, Asian people also learned to deploy the category at times to their own benefit. For example, a man named Juan Alonso appeared before the royal court in Mexico City in 1591 and argued successfully that restrictions against "indios" riding horseback should not apply to him, since he was a "chino." In other cases, "chinos" found new commonalities through their mutual displacement and frequently formed intimate bonds with other "chinos," even those belonging to different ethnolinguistic groups. They also founded confraternities that offered mutual assistance and selected each other as godparents for their children. In specific circumstances, then, being "chino/a" served as a "strategic essentialism," an expedient form of identity making in which established stereotypes are manipulated for the sake of both situational gain and broad solidarity among multiple groups. "Chino/a" was a fluid category, one that indicated both foreignness and new articulations of identity and subjecthood.

Yet as Dana Murillo has observed, "social change or acculturation does not equal cultural annihilation." The extant documentation suggests that the first Asians in the Americas often retained a distinct sense of their identities, even as they received baptism, married across ethnolinguistic lines, conversed in Spanish and Nahuatl, and acculturated into existing communities of other castes.

Excerpt from The First Asians in the Americas: A Transpacific History (2024) by Diego Javier Luis

#asian american history#latin american history#latin america#asian history#spanish colonialism#mexico#colonialism#x#history

11 notes

·

View notes