#native history

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Native Wisconsin

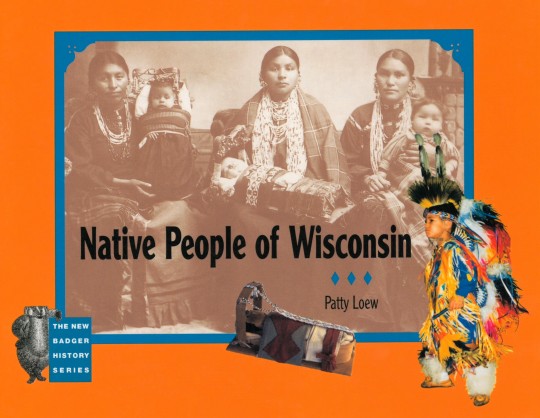

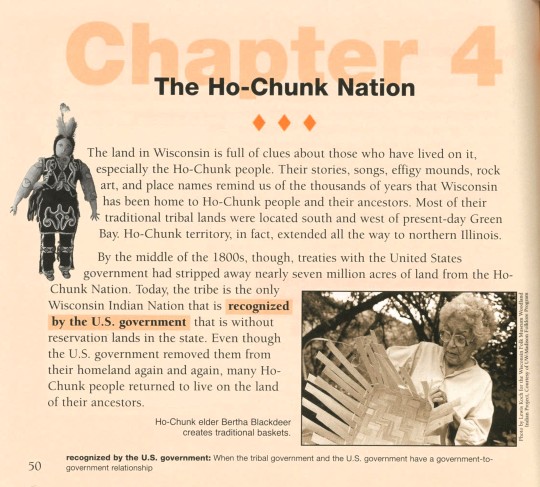

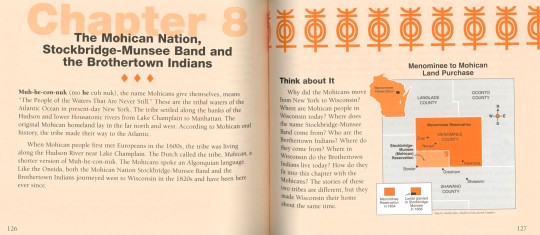

Native People of Wisconsin by Ojibwe scholar and journalist Patty Loew (b.1952), published in 2003 by the Wisconsin Historical Society Press in Madison, Wisconsin, is a book for young readers about the twelve Indian Nations that live in Wisconsin, including my tribe, the Stockbridge-Munsee Band of Mohicans. The book also includes the history of the First People in Wisconsin and the impact of European arrivals on Native culture.

Patty Loew, a Wisconsinite and member of the Bad River Band of the Lake Superior Ojibwe tribe, is a journalist, professor, author, community historian, broadcaster, documentary filmmaker, academic, and advocate. This children's book is a testament to her work, showcasing tribal narratives that encompass different methods through which Indigenous communities preserve their history. With a particular emphasis on oral tradition, this work is a valuable resource for educators and individuals interested in Native American history and will surely captivate young readers.

View other posts from our Native American Literature Collection.

View more from our Historical Curriculum Collection.

-Melissa (Stockbridge-Munsee), Special Collections Graduate Intern

#native people of wisconsin#patty loew#children's books#wisconsin indians#native americans#wisconsin historical society press#indigenous#oral traditions#native american history#native history#native american literature#indigenous peoples#indigenous america literature collection#historical curriculum collection

106 notes

·

View notes

Text

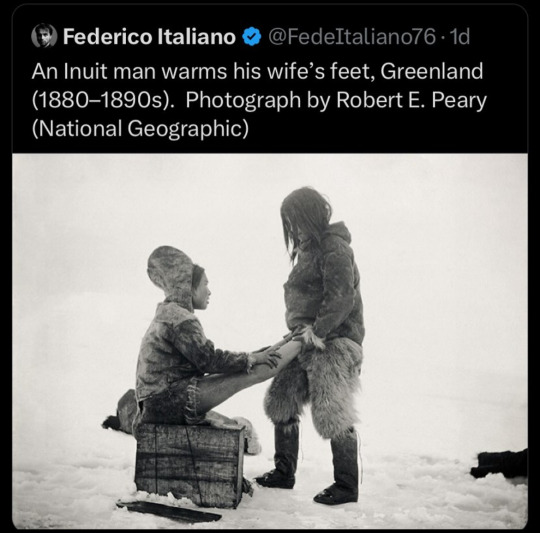

Someone Zukka-ify this PLEASE

#avatar the last airbender#atla#sokka#zuko#sokka avatar the last airbender#zukka#zukka nation#zuko x sokka#zukka au#adult zukka#Zukka art#zukka fanart#fanart#art prompt#Inuit#Inuk#inivialuit#history#native history

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

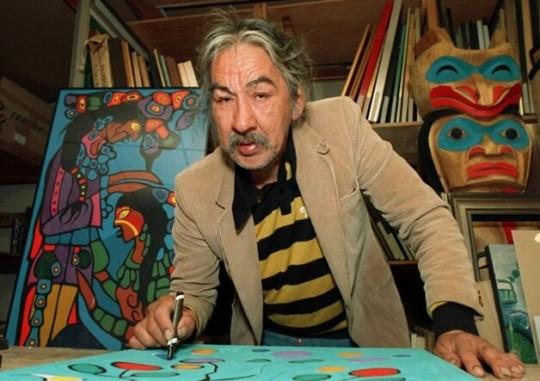

Norval Morrisseau (deceased)

Gender: Male

Sexuality: Bisexual

DOB: 14 March 1932

RIP: 4 December 2007

Ethnicity: First Nation (Ojibwe)

Nationality: Canadian

Occupation: Artist

Note: Widely regarded as the grandfather of contemporary Indigenous art in Canada

#Norval Morrisseau#lgbt history#native history#lgbt#qpoc#male#bisexual#1932#rip#historical#native#first nation#canadian#artist#popular#popular post

116 notes

·

View notes

Text

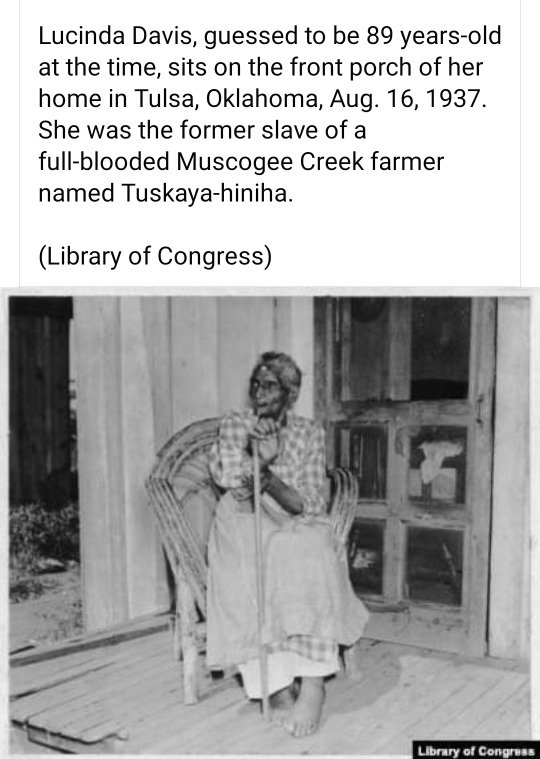

Lucinda Davis (c. 1848-after 1937) was a slave who grew up in the Creek Indian culture. She spoke the Muskogee Creek language fluently. The main information source was from an interview in the summer of 1937, at which time she was guessed to be 89 years old. Lucinda's parents were owned by two different Creek Indians. Being enslaved so young without her parents, she never found out her birthplace, nor the time of her birth. Her mother was born free in African when she escaped her captors either by running away or buying back her freedom, the white enslaver, who was also the mother's rapist and father of Lucinda, sold their child to Tuskaya-hiniha. Lucinda was brought up in The way the Creeks treated slaves was considered a much different and kinder form of slavery than the way the white Americans, Cherokee, or Choctaw went about it. Families could work under different slave owners and did not have to live on the same property as whom they worked for. The slaves worked quite hard and were paid, but had to give most of their pay to their owners, being allowed to keep a small amount. Lucinda was treated as a family member and did her duties. Her responsibility was taking care of the baby, amongst being an extra hand for cleaning and cooking here and there. She was not beaten or disrespected. It was understood what was needed of her, and she followed along.

#black history#native american tribes#native#black tumblr#black history month#oklahoma history#black literature#american slavery#african slavery#black community#civil rights#native history#lucinda davis#black history is american history#american history

477 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fr tho there's something so fucking special about historical diaries & accounts of the inner feelings of someone who was alive 140+ years ago, and also a POC in the midst of a Colonial Shitfire™️ (i love where my work takes me):

Man who was looked at as hard/cold, was a Hot Topic™️ in the last decade bc of governing a colonial society while black & having a native wife/kids: writes the exact minute & day when his many children passed during the hard fort years of British Columbia (1800s). It has got me in the fucking feels IT IS SO SAD I CANNOT DESCRIBE IT, YOU ACTUALLY HAVE TO READ THE SCRIPT OF HIS HANDWRITING TO FEEL IT:

"Little boy": Not baptized, born 5th November, 1833. Died same day. It was Saturday.

"Ellen": died 24th November, 1834 at a few minutes past 8 in the morning. Friday.

I CANTTTT😭😭

Then the years ago by, the kids who make it grow up: he's now writing letters to his youngest, the golden child, saying how he still puts an apple on her nightstand to pretend she's home while overseas, how he walks under the apple tree in their front yard (the tree i ended up studying and smoking weed under lmao) and aches at her absence- how "mama cries for you to just come home" ITS ALL TOO MUCH😭

Fr FUCK all those people who petitioned for his statue to be removed & for this family history to be disregarded- our island was governed by a black man, with a Cree wife, in the fucking 1800s in a society full of British people who CONSTANTLY talked shit and they were like "yeah, not relevant"????????? i will forever be pissed

and fuck all those victorian assholes from the 1860s who talked shit about their "manners", their native language & who called the kids "half-breeds"

#soup personal#not hp#history#research#social justice#poc#1800s#victorian era#victorian#vancouver island#canada#british columbia#culture#world history#museums#historical stuff#digital archiving#web archiving#colonialism#anti colonization#colonial era#colonial america#colonial history#19th century#native american#native people#african american#african america history#native history#aboriginal

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rosebud Yellow Robe

Rosebud Yellow Robe was born in 1907 in Rapid City, South Dakota. Yellow Robe was an early proponent of the study of Native American cultures. From 1930 to 1950, she served as director of Indian Village at Jones Beach State Park. There, she educated schoolchildren by performing ceremonial dances, teaching crafts, and telling stories. In 1969, Yellow Robe published her first book, Album of the American Indian, which depicted the daily lives of seven different Indian tribes before colonization. In 1979, she published her second book, Tonweya and the Eagles, a collection of Native American folktales for children.

Rosebud Yellow Robe died in 1992 at the age of 85.

Image

#native american#american indian#indigenous#indigenous women#native history#american history#history#lakota sioux

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Please sign below👇

#happy thanksgiving#charlie brown#a charlie brown thanksgiving#thanksgiving#thanksgiving quotes#thankgiving#native representation#native history#texas#funk Texas#whitewashing#poll workers#not a poll#poll survey#poll winner#poll dancing#poll results#poll#music poll#poll time#indigenous american#holiday poll#tumblr polls#random polls#my polls#poll blog#polls#tournament poll#a poll a day#incognito polls

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Single Spout Blackware Vessel in the Form of a Duck. Chimú. Peru. 1000-1400 CE.

Art Institute of Chicago.

#art#culture#history#sculpture#medieval history#medieval#Middle Ages#birds#bird#duck#ducks#animals in art#the art institute of chicago#native history#indigenous art#south american history#peruvian history#Peru#peruvian

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yahgan

The Yahgan, also known as Yámana, are an Indigenous people native to the southernmost regions of South America, particularly the islands and coastal zones of the Tierra del Fuego archipelago in southern Chile and Argentina. They are historically known as the southernmost human population in the world, having adapted over thousands of years to one of the harshest climates on Earth. The Yahgan language, culture, and way of life are singularly shaped by the subpolar maritime environment, making them one of the most remarkable examples of human adaptation to extreme ecological conditions. While their numbers have dwindled significantly due to colonization, disease, and cultural assimilation, efforts are ongoing to preserve and document their heritage.

Historically, the Yahgan inhabited a vast maritime zone encompassing the southern tip of South America, including the Beagle Channel, the islands of Navarino, Hoste, and the Wollaston and Hermite island groups, extending even to Cape Horn. Unlike other Indigenous groups in the region such as the Selk'nam, who occupied the interior of the main island of Tierra del Fuego, the Yahgan were coastal dwellers, relying extensively on the sea for sustenance. Their domain was characterized by dense fjords, glacial channels, and rugged archipelagos, where wind, rain, and cold were constants. Their mobility by canoe allowed them to traverse large distances among these islands, and their settlements were typically temporary, reflecting a semi-nomadic lifestyle.

Archaeological evidence suggests that Yahgan ancestors have inhabited the region for at least 6,000 to 10,000 years. Early sites, such as those at Wulaia Bay and other parts of Navarino Island, have yielded substantial middens of shellfish, bones, and tools, attesting to a complex and long-standing adaptation to a marine-based subsistence. Genetic and linguistic data place the Yahgan within the wider group of Indigenous peoples of Patagonia and Tierra del Fuego, though they are linguistically and culturally distinct. They are sometimes classified with the Alacaluf (Kawésqar) and the Chono as part of a larger “canoe people” tradition of the Patagonian archipelagos.

The Yahgan language, often referred to as Yámana, is a language isolate, meaning it has no known relationship to any other language family. It is highly polysynthetic, allowing complex ideas to be expressed in single words through the use of affixes. Yámana has an elaborate verbal system and a rich lexicon related to the natural environment, including extensive terminology for navigation, weather, marine life, and coastal geography. The language has undergone a drastic decline since the late 19th century, primarily due to the disruption of traditional Yahgan life and assimilation pressures. Cristina Calderón, who passed away in 2022, was considered the last fully fluent native speaker. Efforts are now underway by linguists and cultural organizations to document and revive the language through preserved texts, audio recordings, and community education.

The Yahgan economy was traditionally based on foraging, fishing, hunting, and gathering along the coastal marine ecosystem. Men primarily hunted sea lions, collected shellfish, and fished using bone hooks and woven traps, while women were chiefly responsible for gathering mollusks, crustaceans, sea urchins, and other coastal edibles. The Yahgan used sophisticated dugout canoes (constructed from bark or hollowed-out logs) to navigate their aquatic environment. Fireplaces built in these canoes allowed them to stay warm while traveling, an innovation that astonished early European observers. Their use of fire, in fact, was so characteristic that early European explorers, such as Ferdinand Magellan, named the region “Land of Fire” (Tierra del Fuego) upon seeing the multitude of fires onshore.

Their toolkit included stone and bone implements, harpoons, fishhooks, and baskets woven from rushes and grasses. They also utilized the pelts and sinews of marine mammals for clothing and tools. Unlike other hunter-gatherer societies, the Yahgan did not engage in agriculture or animal husbandry.

The Yahgan lived in small, kin-based bands that moved seasonally according to resource availability. These groups were relatively egalitarian, with a flexible social structure. Leadership was informal and often based on age, wisdom, or oratorical skill, rather than hereditary status. Extended families cooperated in subsistence tasks, and property was largely communal.

Family units typically occupied small dome-shaped huts made of bent poles covered with grass, bark, or animal skins. These dwellings were adapted to withstand wind and rain and could be easily dismantled and relocated. Gender roles were clearly defined but not rigid; both men and women contributed significantly to the group’s survival.

Yahgan cosmology and belief systems were animistic and closely tied to the natural world. They believed in a spirit world inhabited by beings associated with animals, landscapes, and weather phenomena. Mythology and oral traditions were central to Yahgan culture, with tales of powerful ancestral spirits, heroes, and supernatural beings. One of the most well-known mythological figures is Watauinewa, a culture hero and shaman who features in many Yahgan stories.

Shamans (or yecamush) were spiritual leaders who mediated between the physical and spiritual realms. They were believed to possess healing powers, the ability to control weather, and knowledge of sacred rituals. Initiation rites and ceremonial dances were conducted to ensure social cohesion and reinforce cosmological beliefs, though much of this ceremonial life has been lost or obscured due to colonial disruption.

Perhaps the most remarkable aspect of Yahgan life is their physiological and cultural adaptation to the extreme cold and wet conditions of their environment. Despite average temperatures rarely exceeding 10°C (50°F) and frequent rain, snow, and wind, the Yahgan traditionally wore minimal clothing. Instead, they used layers of animal fat (especially from sea lions) as insulation and relied on their high metabolic rate to generate body heat. Fires were kept constantly burning in canoes, huts, and campsites. They also used body painting and greasing as both insulation and ritual expression.

Recent studies in biological anthropology suggest that the Yahgan may have developed unique metabolic adaptations, including a higher basal metabolic rate, to cope with cold exposure. Their exceptional knowledge of local ecology, combined with technological ingenuity and social cooperation, allowed them to flourish in one of the world’s harshest inhabited regions.

Contact with Europeans, beginning in the 16th century and intensifying in the 19th century, had catastrophic effects on Yahgan society. Initial encounters were sporadic, but by the 1800s, missionary activity, especially by the British-based South American Missionary Society, led to more sustained contact. While some missionaries sought to protect and educate the Yahgan, the consequences included exposure to diseases such as smallpox, tuberculosis, and measles, which decimated the population. Land dispossession, cultural disintegration, and the disruption of subsistence patterns followed.

European settlements and sheep ranching displaced Yahgan groups from traditional territories, and violent conflict sometimes occurred. By the early 20th century, most Yahgan had been relocated to missions or marginalized settlements, such as the mission at Ushuaia, now the capital of Argentina’s Tierra del Fuego province.

The Yahgan have been the subject of significant anthropological and linguistic interest since the 19th century. Notable researchers include Thomas Bridges, a missionary who compiled a Yahgan–English dictionary and translated parts of the Bible into Yámana. His dictionary remains one of the most detailed records of an Indigenous language of South America, with over 32,000 words and extensive ethnographic notes. Martín Gusinde and Anne Chapman also conducted important 20th-century ethnographic work, documenting oral traditions, rituals, and cultural practices.

Despite early academic interest, the Yahgan were often romanticized or misunderstood in colonial literature, portrayed either as "noble savages" or as cultural anomalies. Modern scholarship strives for more nuanced, Indigenous-centered perspectives, acknowledging Yahgan agency, resilience, and innovation.

At the time of European contact, Yahgan population estimates vary widely, from around 3,000 to possibly 5,000 individuals. By the mid-20th century, fewer than 100 remained. Today, only a small number of Yahgan descendants survive, most of whom live in Puerto Williams on Navarino Island in Chile, and a few scattered across Tierra del Fuego in Argentina. While most no longer live a traditional lifestyle, many maintain a sense of Yahgan identity and participate in cultural revitalization efforts.

These include language preservation initiatives, cultural museums, and the teaching of traditional crafts, canoe-making, and navigation techniques. The Yahgan are officially recognized as an Indigenous people by the Chilean state, granting them certain legal rights and representation, although economic and political marginalization persist.

The Yahgan people are increasingly recognized as a symbol of environmental adaptation, cultural resilience, and Indigenous knowledge. In the face of climate change and ecological degradation, the Yahgan worldview—rooted in symbiosis with the marine environment—has garnered interest among conservationists and ethnobiologists. Their ancestral territory, now part of the Cape Horn Biosphere Reserve, is among the most biologically unique and least disturbed ecosystems on Earth.

Ongoing partnerships between Yahgan communities, scientists, and cultural institutions aim to ensure the survival of both the Yahgan heritage and the ecosystems they once stewarded. Such efforts are part of a broader movement to restore historical justice and amplify Indigenous voices in the global narrative.

The Yahgan represent a unique chapter in the human story—one of survival, innovation, and profound connection to a demanding environment. Their culture, language, and history are invaluable not only as records of the past but as blueprints for alternative ways of living in harmony with the natural world. Though reduced in number, their legacy continues to resonate through ongoing efforts in linguistic preservation, cultural revival, and environmental stewardship.

#yahgan#yámana#indigenous peoples#tierra del fuego#south american history#ethnography#cultural heritage#endangered languages#indigenous rights#human adaptation#first nations#native history#anthropology#ethnology#oceanic peoples#hunter gatherers#ancient cultures#maritime culture#archaeology#language revitalization#decolonize history#indigenous resistance#native voices#shamanism#body painting#traditional lifeways#nomadic peoples#forgotten histories#cape horn#beagle channel

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Serpent labret—Mexica (modern central Mexico), 1325-1521 CE

I want to note that although the Met description uses the term "Aztec," the preferred term is Mexica according to what I have read from Mexica people.

According to the Met: "Superbly crafted in the shape of a serpent ready to strike, this labret—a type of plug inserted through a piercing below the lower lip—is a rare survival of what was once a thriving tradition of gold-working in the Aztec Empire. Gold, in Aztec belief, was teocuitlatl, a godly excrement, closely associated with the sun’s power, and ornaments made of it were worn by Aztec rulers and nobles. Historical sources describe a variety of objects made of gold, including a serpent labret sent by Hernán Cortés as a gift to the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V, yet nearly all of these objects were melted down at the time of the Conquest and shortly thereafter, converted to gold ingots for ease of transport and trade.

The serpent’s head features a powerful jaw with serrated teeth and two prominent fangs. Scales are represented in delicate relief on the underside of the lower jaw. A prominent snout with rounded nostrils rises above the maw of the serpent, and the eyes are surmounted by a pronounced supraorbital plate terminating in curls. On the crown of the head, a ring of ten small spheres and three loops rendered using the technique of false filigree represents a feather headdress with beads. The bifurcated tongue, ingeniously cast as a moveable piece, could be retracted, or swung from side to side, perhaps moving with the wearer’s movements. The sinuous form of the serpent’s body attaches to a cylinder or basal plug ringed with a band of tiny spheres and a band of wavelike spirals. The plain, extended flange would have held the labret in place within the wearer’s mouth.

Labrets, called tentetl in Nahuatl, the language of the Aztecs, were manifestations of political power. The Codex Ixtlilxochitl, an early colonial-period manuscript now in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris, includes a portrait of the ruler Nezahualcoyotl in full warrior attire, complete with a gold raptor labret (fol. 106r). Nezahualcoyotl was the lord of Texcoco, one of the three cities that formed the Triple Alliance, the union at the core of the Aztec Empire formed by the Mexica of Tenochtitlan, the Alcolhua of Texcoco, and the Tepaneca of Tlacopan. The Aztec title for the royal office was huey tlahtoani, or "great speaker," and the adornment of the mouth was highly symbolic. According to Patrick Hajovsky, a scholar of Aztec art, labrets were the visual markers of the eloquent, truthful speech expected of royalty and the nobility. Crafted from a sacred material, a labret such as this would have underscored the ruler’s divinely sanctioned authority, and asserted his position as the individual who could speak for an empire. Not surprisingly, therefore, the insertion of a labret was part of a ruler’s accession ceremony.

Labrets were also closely associated with military prowess. Specific types of labrets were awarded to warriors based on certain achievements. Gold ornaments, however, appear to have been restricted to royalty and the highest ranks of the nobility, although on occasion gold ornaments could be given by the king as gifts to provincial rulers. Because of its imperviousness to decay, gold would have been an appropriate material to suggest the enduring power of rulers. Such labrets would not have been worn on a daily basis, but rather as part of ceremonial or battle attire donned on specific occasions. Worn on ritual occasions and on the battlefield, this labret, like its wearer, a serpent ready to strike its prey, would have been a terrifying sight.

Serpents have been a favored subject in Mesoamerican art from at least the second millennium B.C. As creatures that could move between different realms, such as earth, water, and sky, they were considered particularly appropriate symbols for rulers and mythological heroes such as Quetzalcoatl, the legendary "feathered serpent." The combination of the curled eyebrow and snout, along with the feathered headdress, may mark this creature as Xiuhcoatl, a mighty fire serpent conceived of as an animate weapon of the Aztec sun god, Huitzilopochtli. Stylistically, this labret has much in common with works in other media, from monumental stone sculptures to a turquoise mosaic double-headed serpent pectoral now in the British Museum (AOA AM 94-634).

Although gold working developed relatively late in Mesoamerica (after AD 600), metalsmiths developed innovative approaches in different regions and produced works of great artistry and technical sophistication. Oaxaca, one of the major sources for gold, was also long considered one of the primary centers for the production of gold objects. Recent research by Leonardo López Luján and José Luis Ruvalcaba Sil, however, has revealed an important gold working tradition in the Basin of Mexico. Small cast gold bells and ornaments of hammered sheet metal have been excavated at Mexico City’s Templo Mayor, or Great Temple, the sacred center at the heart of the Aztec Empire. The finds there include a bifurcated tongue fashioned from sheet gold, and cast-gold bells that once adorned a wolf and an eagle, animals that were sacrificed and placed in one of the Templo Mayor’s dedicatory caches.

Outside of the Templo Mayor finds, the majority of the Aztec works in gold that have survived—including this labret—are ornaments for the royal or noble body. Most Aztec labrets are plain obsidian or greenstone plugs (see, for example, MMA 1979.206.1090-1092), although exceptional examples were made in the form of raptors such as eagles (MMA 1978.412.218; Saint Louis Art Museum 275:1978; Museo Civico di Arte Antica, Turin; see also one in jadeite, MMA 02.18.308). Another serpent labret, possibly from Ejutla, Oaxaca, is now in the National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C. (18/756).

This serpent labret, perhaps the finest Aztec gold ornament to survive the crucibles of the sixteenth century, is an exceedingly rare testament to the brilliance of ancient Mexican metalsmiths. Monumental sculpture in stone, ceramic vessels, and other more durable forms of cultural production shed light on key aspects of Aztec ritual and daily life. But gold, in its infinite ability to be transformed, melted and re-worked, could always be remade to suit current needs, and thus rarely survives from antiquity. Though small, this masterpiece opens a window into Aztec culture at the very highest level, a world almost entirely obliterated when Hernán Cortés arrived on the shores of Mexico in 1519."

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

it’s indigenous history/awareness month, you should all send me $100 x

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

My family Chickasaw Freedmen.

#chickasaw freedmen#black history#black tumblr#native american tribes#black literature#native history#black community#black history is american history#native american history#native americans#black lives matter#american history

239 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello. This is a rather mundane question considering all the things, but I got curious. Does Hebrew have accents? How do they vary in and out of Israel?

I understand if you choose not to reply as this is a difficult time for you. In any case, take care🩷🩷🩷

Hi Nonnie! No, don't worry, all questions that are truly interested in Jewish culture are welcome! ^u^

TBH, something to remember about Hebrew is that it has quite a unique history. To the best of my knowledge, it is the only language that was used on a daily basis as the lived in language of a native population, then "died" as a result of Jews being exiled. As they found themselves in other countries, they had to speak the local language. They didn't abandon Hebrew, but it stopped being the langauge in which they lived their daily lives. Hebrew became the language of prayer, of scripture study, and terms from it bled into the local languages Jews spoke, creating Jewish versions of these languages (Yiddish being the Jewish version of German, Ladino being the Jewish version of Spanish, Yevanik being the Jewish version of Greek, and there are also Jewish versions of Arabic and other languages, too), so Hebrew still had an impact on Jews, and they were still connected to it... but it was no longer a "living" language. It was closer to what Latin is today. A language in which religious ceremonies are conducted, that theologians study, but not a language that anyone conducts their daily life in.

Then, as a part of the project of reclaiming and reviving the Jewish native life in Israel that came to be known as Zionism, people set out to revive our native language, too. There was a realization that it had to be adapted to modern life, give it terms for things that didn't exist 2,000 years ago, so it would be useful for people who wanted to conduct their daily lives in Hebrew again. And that's how the last of the Canaanite languages became the only "dead" language to be revived, and return to be the lived in language of its native people.

I mention this unique history, because modern Hebrew isn't the same as biblical Hebrew (though about 60% of modern Hebrew IS biblical). It means if there were different Hebrew accents during biblical times, we don't know it for sure.

At the same time, the fact that Jews were spread out in the diaspora, and their pronunciation of Hebrew (as a dead language) came to be influenced by the local languages they spoke while in exile. So a Jew who returned to Israel from the diaspora in Germany, a Jew who returned to Israel from the diaspora in Argentina, and a Jew who returned to Israel from the diaspora in Yemen do not have the same accent when speaking Hebrew.

But these are not considered regional accents of Hebrew in the same way that you can find different regional accents of English when traveling across England... If we put aside the accents of Jews returning to Israel, and instead we look at the accents of Jews born in Israel, the ones born into speaking modern Hebrew, there's a myth of a Jerusalem accent. I say myth, because you'll hear all over Israel people swearing, that Jerusalemites pronounce a few words differently. The most common example is the word 'mataim' (which means two hundred), and many Israelis insist Jerusalemites pronounce it ma'ataim, with the first vowel prolonged and emphasized. I have lived in Jerusalem since 2002 and I have never heard it. I think in this sense, regional accents are usually, at least in part, a product of geography. It determines how far apart people live, how much they interact, how much they hear others speaking the same language as they do. The smaller a country, and the easier travel in it is, the fewer accents it's likely to produce. And I think that's the main reason why there aren't really accents in Israel (other than those of people who came to speak Hebrew as a second language), because it's a very small country, and because today, it's pretty easy to travel in it (you can cross it from the most northern point to the most southern one in slightly over 5 hours).

I hope that kind of answers it? Thank you for the kind words, I hope you're well, too! xoxox

#ask#anon ask#israel#hebrew#jewish history#jewish#jew#jews#jumblr#frumblr#native israeli#native history#cultural revival#language revival#native revival

79 notes

·

View notes

Text

The exciting part is, there's no end to my learning about the history of my people.

I can devote the rest of my life to it and never run out of things to do.

Maybe I'll try to learn our language. There's got to be historians around who can help me out with that.

17 notes

·

View notes