#legal history

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

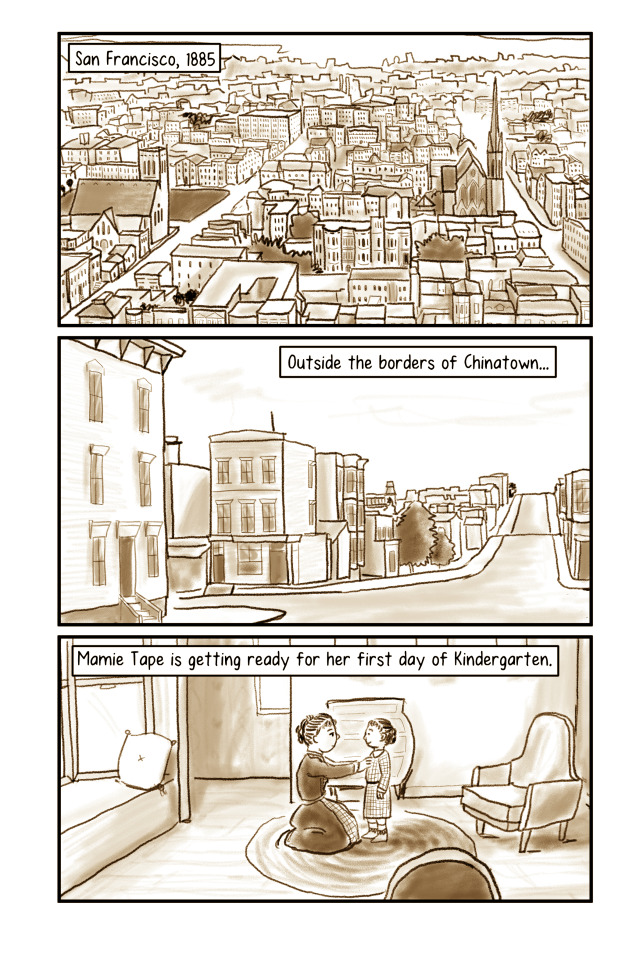

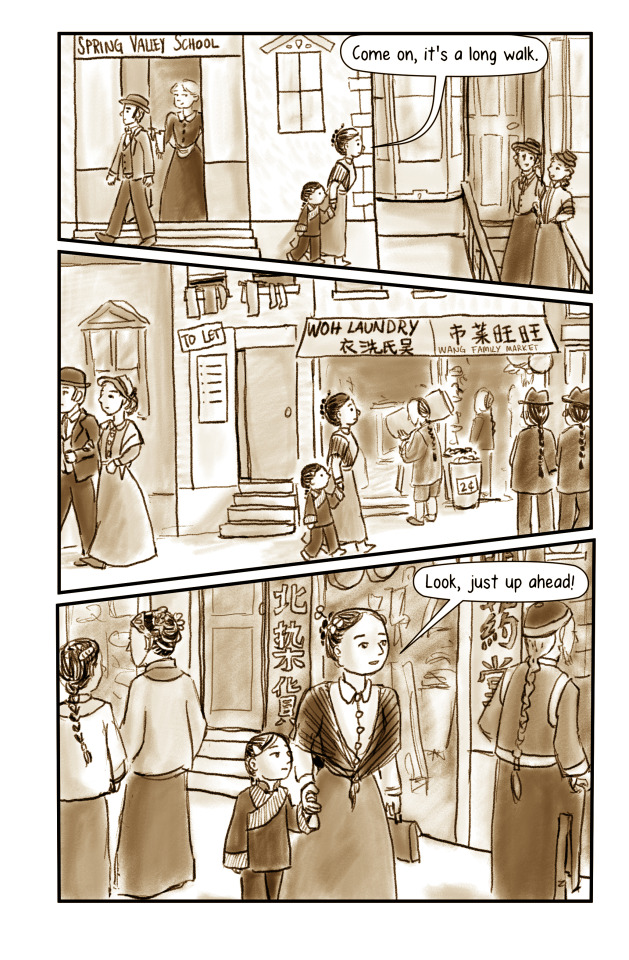

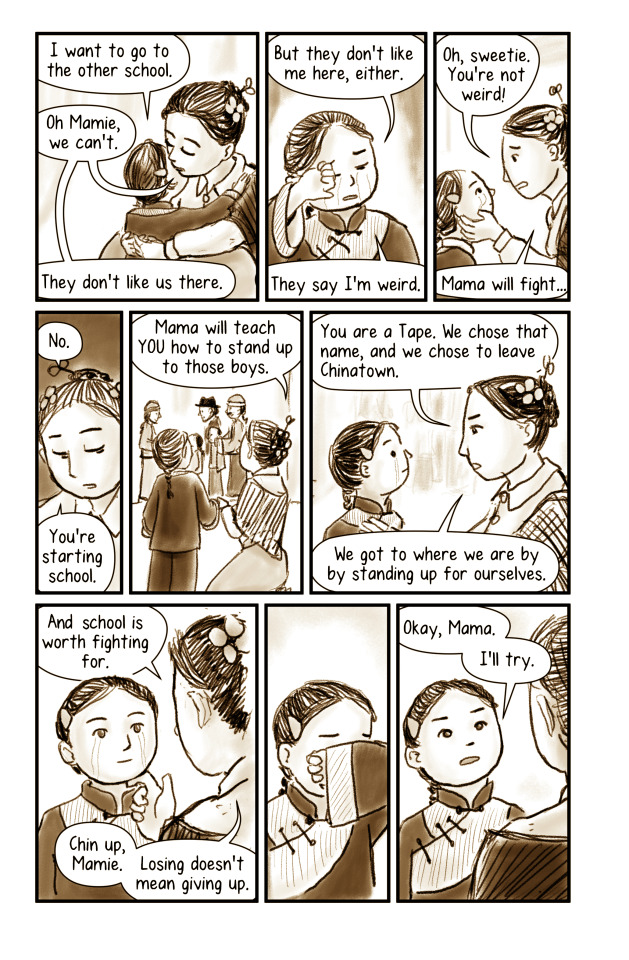

in my pursuit of ever-increasingly niche comics, I drew a 13 page comic about Tape v Hurley, a court case about Chinese-American school segregation in 1885. The rest of the pages are after the readmore, as well as on AO3 here. More obsure Chinese American court case comics are there, as well.

Historical Notes

Mary and Joseph Tape were not born in America, but their names and identities were very much formed in America. Joseph Tape was born Jeu Dip in Guangdong, China, immigrated the America when he was twelve, and spent his teenage years working as a house servant in an Irish household. Mary arrived in America at the age of eleven, and was found and raised as Mary McGladery in a Protestant orphanage as the only Chinese child amongst ~80 children. Both Mary and Jeu spent their formative years amongst White Christian families, so when Jeu Dip and Mary married in 1875, little wonder that Jeu picked the English name of Joseph Tape -- Joseph to match with Mary, and the German last name Tape as a nod to his former name of Dip.

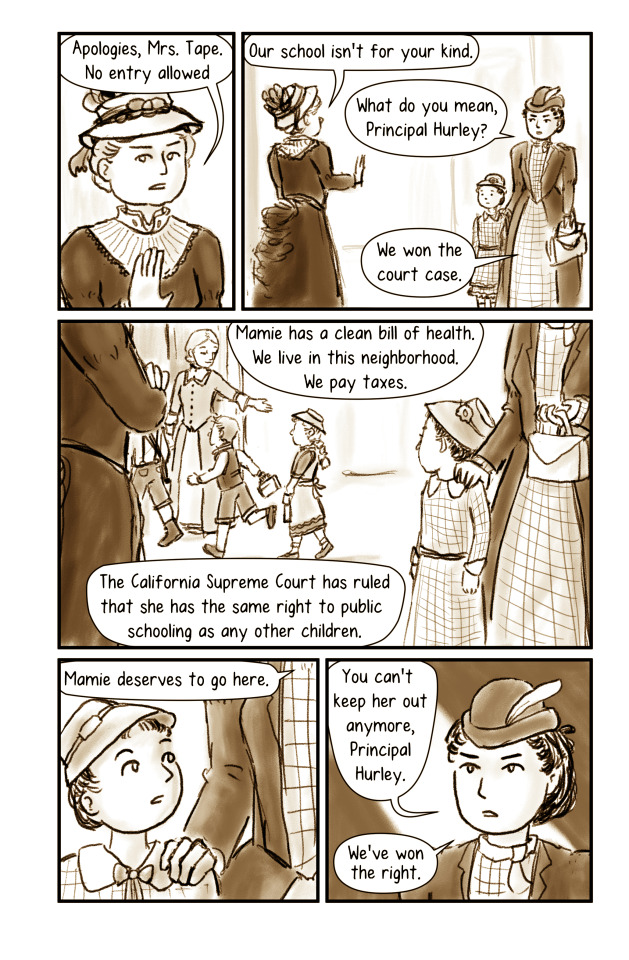

The Tape family lived about 14 blocks outside of Chinatown, in a primarily white neighborhood. They dressed in Western clothing, spoke English at home, and Mamie grew up playing with non-Chinese kids. Naturally, they wanted their children to attend the local elementary school, a mere 3 blocks from their home. The principal, Ms. Hurley, denied her entrance, claiming that she was “filthy and diseased.” At the time, there was no public school option for Chinese children -- the 1870 state law stipulated separate schools for “African and Indian children” only, not Chinese. The Tape family, with the help of the Chinese Six Companies, their church, and the Chinese consulate, decided to sue, claiming that the 1880 California school code guaranteed everyone a right to public education and that this was a violation of the 14th Amendment.

They won.

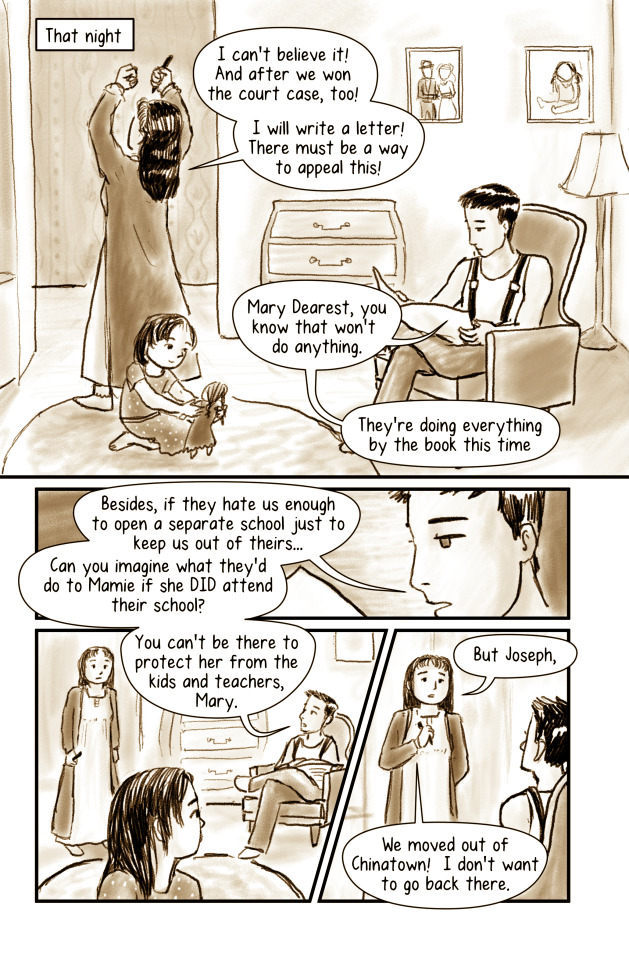

But this was 1885, three years after the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act and six years before Plessy v Ferguson. Regardless of what the California Supreme Court might decide, public sentiment was on the side of the San Francisco school district. Determined to keep out this “invasion of Mongol barbarism”, the California State Legislature passed a law permitting separate schools for Chinese children, which then allowed Principal Hurley to reject Mamie Tape once more.

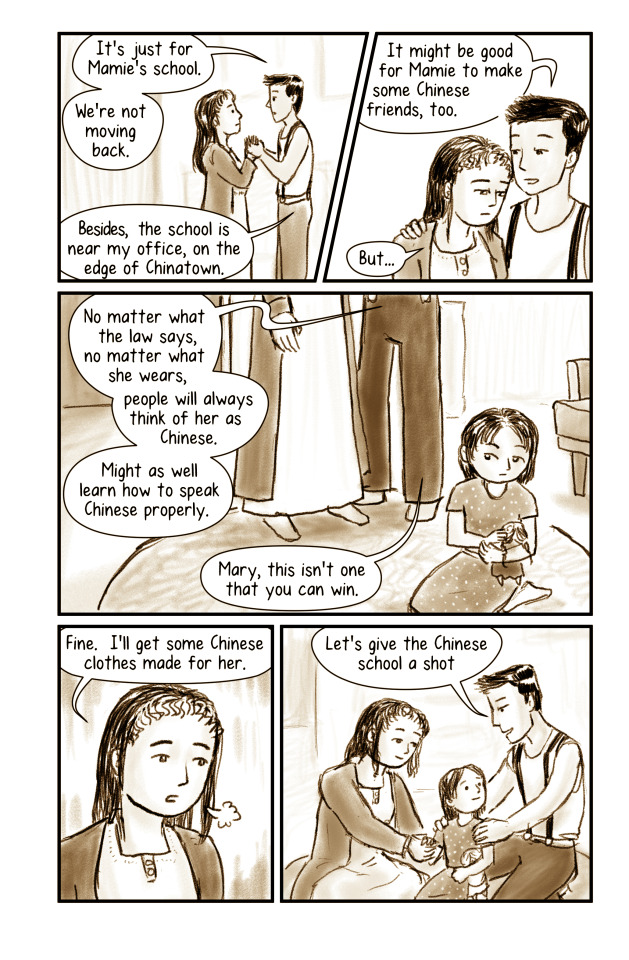

While Mamie was rejected from the Spring Valley Elementary School for being Chinese, she also had a hard time fitting in to the Chinese public school. The Chinese merchants saw Western education as something primarily for boys. (Their girl children learned from their mothers at home.) Mamie, a girl dressed in Western clothes, would have stood out like a sore thumb. The final panel of the comic was based on a photo from three years later, and even then, Mamie was the only girl.

Places where I fudged the history: Frank, Mamie’s younger brother, was actually six years old and should have been more present in the comic, but I wante to keep the focus on Mamie and Mary. Also, Mamie had actually shown up to her first day of school in Western clothes. An earlier draft of the comic had a separate arc involving Mamie feeling rejected at school and Mary buying her some Chinese clothes, but that got too long and complicated.

Much of this was drawn from Mae Ngai’s book about the Tape family and their experiences as 2nd and 3rd generation Chinese Americans, titled “The Lucky Ones.”

----------

Here is Mary Tape's letter to the San Francisco School Board, 1885:

1769 Green Street. San Francisco, April 8, 1885. To the Board of Education - Dear Sirs: I see that you are going to make all sorts of excuses to keep my child out off the Public schools. Dear sirs, Will you please to tell me! Is it a disgrace to be Born a Chinese? Didn’t God make us all!!! What right have you to bar my children out of the school because she is a chinese Decend. They is no other worldly reason that you could keep her out, except that. I suppose, you all goes to churches on Sundays! Do you call that a Christian act to compell my little children to go so far to a school that is made in purpose for them. My children don’t dress like the other Chinese. They look just as phunny amongst them as the Chinese dress in Chinese look amongst you Caucasians. Besides, if I had any wish to send them to a chinese school I could have sent them two years ago without going to all this trouble. You have expended a lot of the Public money foolishly, all because ofa one poor little Child. Her playmates is all Caucasians ever since she could toddle around. If she is good enough to play with them! Then is she not good enough to be in the same room and studie with them? You had better come and see for yourselves. See if the Tape’s is not same as other Caucasians, except in features. It seems no matter how a Chinese may live and dress so long as you know they Chinese. Then they are hated as one. There is not any right or justice for them. You have seen my husband and child. You told him it wasn’t Mamie Tape you object to. If it were not Mamie Tape you object to, then why didn’t you let her attend the school nearest her home! Instead of first making one pre tense Then another pretense of some kind to keep her out? It seems to me Mr. Moulder has a grudge against this Eight-year-old Mamie Tape. I know they is no other child I mean Chinese child! care to go to your public Chinese school. May you Mr. Moulder, never be persecuted like the way you have persecuted little Mamie Tape. Mamie Tape will never attend any of the Chinese schools of your making! Never!!! I will let the world see sir What justice there is When it is govern by the Race prejudice men! Just because she is of the Chinese decend, not because she don’t dress like you because she does. Just because she is descended of Chinese parents I guess she is more of a American then a good many of you that is going to prewent her being Educated. Mrs. M. Tape

#original comic#chinese american history#legal history#turns out there's a lot of chinese american court cases#that i have a lot of feelings about#my comic#mine

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

King Hammurabi (18th century BCE) is depicted here on the Code of Hammurabi, standing in a prayer position before Shamash, the god of the sun and justice. The famous Code of Hammurabi was not as much a legal code, as it was a piece of propaganda designed to showcase the king's sense of justice and his concern for the well-being of his subjects. The laws were likely intended as "enlightened" examples. Local judges retained considerable leeway in their rulings, basing decisions predominantly on customs and prior judgments by judges and kings, similar to English common law to an extent.

The Code was also regarded as the pinnacle of classical Old Babylonian Akkadian. Its literary value was celebrated in the centuries that followed, with many students in scribal schools copying excerpts from the Code as a writing exercise.

The Code was taken from Sippar to Susa, Iran, by invading Elamite armies in the 12th century BCE. French archaeologists later excavated the basalt cone-shaped stele and transported it to the Louvre, where it is currently housed.

#ancient history#archaeology#art history#babylon#mesopotamia#ancient mesopotamia#sculpture#art#ancient art#assyriology#ancient babylon#legal history

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

Middle Temple Library's Past Exhibitions: Dickens' Legal World

Painting of Charles Dickens by William Powell Frith (1859). The original is held at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

In 2021, Middle Temple Library hosted an exhibition on one of the Inn's most famous past members: Charles Dickens’ Legal World.

Originally intended to coincide with the 150th anniversary of Charles Dickens’ death in 2020, the exhibition was rescheduled for 2021 due to the library’s closure during the Coronavirus pandemic.

The exhibition focuses on Dickens’ employment and engagements in the legal world, including his admission to The Honourable Society of the Middle Temple in 1839 as a student.

Charles Dickens worked as a clerk and court reporter during a period of legal reform in the early Victorian era. His experience shaped some of his most famous works including The Pickwick Papers, Bleak House and Nicholas Nickleby. The Inns of Court are featured locations and the legal professionals he encountered inspired characters throughout his novels.

Illustration from Bleak House by Charles Dickens (1852-1854). Illustration by H. K. Browne

If you were unable to see the exhibition in person you can also enjoy this online presentation. These short films were created to demonstrate Dickens’ connections to the legal world and highlight some of his writings.

#library#law library#mtlibrary#inns of court#history#libraries#books & libraries#london#charles dickens#dickens#dickensian#bleak house#victorian era#victorian#nicholas nickleby#pickwick papers#exhibition#library exhibitions#victorian london#legal history#victorian england#1800s

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

In artful prose, Bradley J. Dixon tells the story of how Native peoples like the Apalachees and Pamunkeys created Indigenous republics in Virginia and Florida by petitioning the Crown to defend their rights against the depredations of the settlers. In doing so, Republic of Indians offers a profound challenge to our assumptions about Native political power in the 1600s and 1700s, while showing how interconnected were the histories of the English and the Spanish in the Americas.

25 notes

·

View notes

Note

Why was queens pardoning prisoners seen as good? Like murders and sexual assaulter ect? Wouldn’t the public be against that?

This is an area where I think Foucault was actually right:

"...The public execution is to be understood not only as a judicial, but also as a political ritual. It belongs, even in minor cases, to the ceremonies by which power is manifested.... The public execution, then, has a juridico-political function. It is a ceremonial by which a momentarily injured sovereignty is reconstituted. It restores that sovereignty by manifesting it at its most spectacular. The public execution, however hasty and everyday, belongs to a whole series of great rituals in which power is eclipsed and restored (coronation, entry of the king into a conquered city, the submission of rebellious subjects); over and above the crime that has placed the sovereign in contempt, it deploys before all eyes an invincible force. Its aim is not so much to re-establish a balance as to bring into play, as its extreme point, the dissymmetry between the subject who has dared to violate the law and the all-powerful sovereign who displays his strength. Although redress of the private injury occasioned by the offence must be proportionate, although the sentence must be equitable, the punishment is carried out in such a way as to give a spectacle not of measure, but of imbalance and excess; in this liturgy of punishment, there must be an emphatic affirmation of power and of its intrinsic superiority. And this superiority is not simply that of right, but that of the physical strength of the sovereign beating down upon the body of his adversary and mastering it by breaking the law, the offender has touched the very person of the prince; and it is the prince - or at least those to whom he has delegated his force - who seizes upon the body of the condemned man and displays it marked, beaten, broken. The ceremony of punishment, then, is an exercise of 'terror'... The sovereign power that enjoined him to kill, and which through him did kill, was not present in him; it was not identified with his own ruthlessness. And it never appeared with more spectacular effect than when it interrupted the executioner's gesture with a letter of pardon...The sovereign was present at the execution not only as the power exacting the vengeance of the law, but as the power that could suspend both law and vengeance. He alone must remain master, he alone could wash away the offences committed on his person; although it is true that he delegated to the courts the task of exercising his power to dispense justice, he had not transfered it; he retained it in its entirety and he could suspend the sentence or increase it at will." (emphasis mine) Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish, ch. 2

Unlike a modern conception of criminal justice, which is premised as an objective, rational, truth-seeking process in which precise identification of the right suspect and their level of guilt and the appropriate nature of their punishment, criminal justice systems in premodern Europe (although not necessarily limited to the same) were meant to emphasize the terrifying arbitrariness of royal power. With rituals put in place in order to ensure guilt through public (often coerced) confessions, the point wasn't whether the sheriff and the judge had "got the right man" or whether "the punishment fits the crime," but that the king could either enact public displays of bodily obliteration or public displays of mercy at their sole discretion.

In a sense, the pardoning of the guilty was a necessary justification for the deliberately disproportionate brutality of a pre-carceral system of punishment. This promoted the logic of submission to the guilty and innocent alike: if the king could sentence you to the ultimate physical dehumanization whether or not you were guilty, the only hope was either the mountain and forest refuge of the outlaw or the hope of a pardon as a quasi-divine act of unearned grace.

67 notes

·

View notes

Text

yes i basically gave up on taking pictures lol

27 March 2025

Today wasn't very productive either, but it was definitely a step up from yesterday. I should really find a way to wake up early and not waste most of the morning hours

I attended my first (public) lecture (agkakqmlfhg!!!!), and could focus the entire time

I read a 16 pg research paper beforehand to be able to comprehend that lecture

I'm now going to summarize the paper i read yesterday

#studyblr#academic research#research#study blog#study space#study motivation#student#studying#chaotic academia#history#economic history#legal history#colonial history

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

March 15th 1921 saw the first women jurors in Glasgow Sheriff Court.

Dates are all over the place with this one, the 10th and 19th are given elsewhere, they all agree it was March of this year. The extract from The Herald gives the 15th. I think what we have here is different courts in Scotland with dates for women's involvement. Anyway a wee bit background;

Ladies have been able to sit on juries in the UK since the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act 1919 came into force, but it only governed women in England, Wales and Northern Ireland, we in AScotland have a, largely, different law system that was agreed at the time of the acts of union in 1707.

On August 9th 1920, a Bill was introduced to regulate how “Scottish women jurors” would be introduced and managed in the courts . The resulting Jurors (Enrolment of Women) (Scotland) Act was given Royal Assent on 16th August 1920, with a timescale of no more than 6 months for it to be brought into effect: “new lists of jurors shall be prepared and come into use in every county within six months after the passing of this Act”. The Court of Session passed an Act of Sederunt regulating the procedure for juries with women on 7th February, and in advance of the February 1921 deadline, in Edinburgh in December 1920 Sheriff Crole instructed the Sheriff Clerk to create a new jurors roll for the city and county, including eligible men and women, and 27,500 circulars were issued. The citations for the Edinburgh Sheriff Court were the first to be issued, and there was discussion of the potential for lady jurors to be cited for duty on 14t March 1921 trial of “the alleged Sinn Fein prisoners”

As I said the different courts have different dates and one source has the first trial as March 10th The case involved the theft of grain from a warehouse in Leith.

Female jurors were expected to first sit in Glasgow Sheriff Court on the 15th of March 1921 and the first lady jurors in the Court of Session sat on the 17th of March 1921 , before Lord Sands. “The case submitted to the jury, whom counsel addressed as “members of the jury” had reference to a claim for damages arising out of a Leith tram-car accident.” This case appears to be unreported, notable only for the jurors rather than the legal points.The first mixed jury sat in Glasgow Sheriff Court on the 21st of March 1921 .

The first murder trial with female jurors in Scotland was heard in Perth on the 5th of April 1921

Although there is regular reference to the belief that women sitting on juries is an experiment, and that it would be “reconsidered by Parliament”, it soon became settled that women were regular participants in juries. The advent of women jurors seems to generally have been received with equanimity in Scotland. Which is more than could be said about the public's reaction to women studying to become doctors in the case of the Edinburgh Seven some 32 years before.

It appears that sitting as a juror was initially something that ladies could excuse themselves from when asked by the judge if they wanted to do so, but this was not something that was occurring in Scotland. Those being tried also apparently had the right to object to female jurors hearing their case, and if this happened, they were dismissed. Again, this does not appear to have happened in Scotland, with mention of defendants objecting to female jurors all relating to English cases. Another concern was how to address female jurors, as “gentlemen of the jury” was no longer accurate, so “members of the jury” seems to have taken its place

By 1923, female jurors seems to be firmly established as a part of normal court business in Scotland, sitting on a variety of cases. The Lord Justice Clerk, Lord Alness, praised female jurors in a speech to the Associated Societies of the University of Edinburgh in January 1923.

On a lighter note by January 1922, you could have placed a bet on a Lady Juror…in the Victoria Cup at Hurst . She appears to have had quite a successful career: by September 1922 she won the Jockey Club Sweepstakes at Newmarket and was still winning five years later at Lingfield in 1927.

It looks like the Lady Juror was definitely a good long-term bet 😉

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Medieval Europe had originally practiced restitutive justice, a form of community customary law that functioned through arbitration with a goal of reconciliation. Because the objective was the restoration of communal peace, it was not advantageous to wipe out one's enemies or to inflict long-term punishment on them. In the effort to keep the community functioning as peacefully as possible, accusers were made responsible for their charges—a false accusation carried a heavy penalty. Early medieval justice, like justice in most primitive societies, was thus personal, requiring face-to-face accusation and judgment by a panel of one's neighbors.

In the twelfth century, however, a very different system of law developed on the continent. Based on Roman law, it stressed punitive justice, emphasizing fines, punishments, and the death penalty. Its goal was to protect and purify the state. Because this law was administered by the state rather than the community, it was impersonal law, with magistrates reporting to superiors in far-off towns and cities. Although this distancing allowed for a certain objectivity of judgment and in some cases provided for appeals, it interjected alien values into communal settlement customs. The judge became the initiator of charges, compiling evidence against suspects, interrogating the accused in secret, using torture when necessary to ascertain the truth, acting always in the name of the state. These changes have been described as "constituting a revolutionary change in legal methods and techniques of societal control."

In addition to the use of torture and impersonal, punitive law, I suggest a third factor of equal importance: whether or not an area still maintained the medieval lex talionis, the mandate that an accuser must prove his or her accusation or suffer the punishment that the defendant would have received. Because the legal penalty for witchcraft was death, this law acted as a powerful restraint on potential accusers. But in many parts of Europe by the sixteenth century, the personal justice of the lex talionis, carried out by the injured parties in a way that restored community relations, was being replaced by a more astract justice administered by state officials; now one could accuse with impunity. This shift rendered European justice more rational but less humane, and it opened the door wide to witchcraft accusations.

-Anne Llewelyn Barstow, Witchcraze

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

I was today years old again when I had discovered that "Crime" was a very different thing from "Tort" when researching Celtic Law

[....]

(Source: Wikipedia)

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

People in the United States have been fighting with insurance companies over what constitutes an accidental death since, and I need you to take this to heart, at least 1889

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

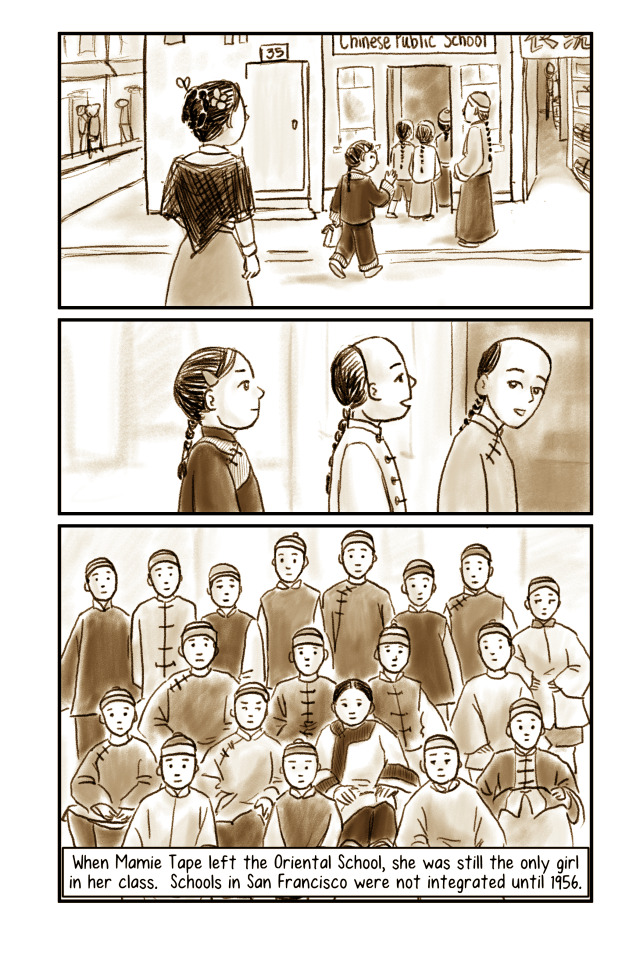

Middle Temple Library's Past Exhibitions: Women in Law

Our Spring 2019 exhibition aimed to highlight women in the law by discussing the pioneers in the profession as well as ‘hidden’ women in professions associated with the law, displaying texts aimed at explaining the law in relation to women and legislative attempts to gain equal rights for women.

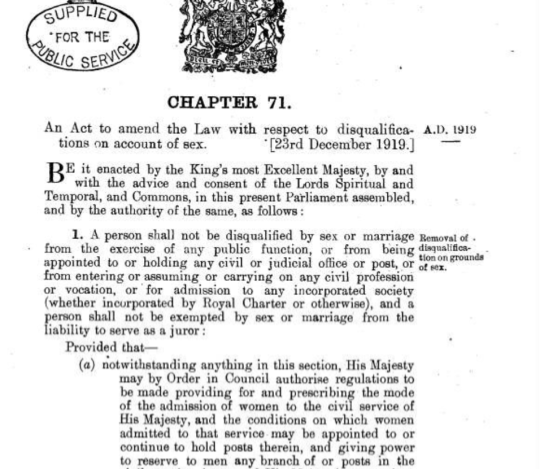

Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act of 1919

2019 marked the 100th anniversary of the passing of the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act of 1919. The passing of this Act allowed women to become practising solicitors and barristers in an official capacity, and to join the Law Society and the Inns of Court: “a person shall not be disqualified by sex or marriage from the exercise of any public function, or from being appointed to or holding any civil or judicial office or post, or from entering or assuming or carrying on any civil profession or vocation, or for admission to any incorporated society (whether incorporated by Royal Charter or otherwise), and a person shall not be exempted by sex or marriage from the liability to serve as a juror”.

Image of Helena Normanton from The Women's Library at LSE Library

As a result of that legislation, the first woman to be called to the Bar on 10 May 1922 was Ivy Williams, a member of Inner Temple. Helena Normanton was Called to the Bar at Middle Temple in November 1922.

To read more please visit the online exhibition

#library#law library#mtlibrary#inns of court#history#libraries#rare books#books & libraries#london#rarebook#women in law#Helena Normanton#women's rights#legal history

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

In entertaining, highly readable prose, The Worst Trickster Story Ever Told charts a clear and accessible path through the thicket of American Indian law. This warm, personal, erudite trickster story is a pleasure—and an education in what ails Indian law, in what might remedy it, and in how the doctrine got into this fix to start.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

… The [Law] Register [of Alexander Hamilton, 1795-1804] is the first document of its kind made available in printed form and copiously annotated. Some readers will use the Register for information on a particular case or cases or for bibliographical aid in exploring court records. Apart from such use the document in its totality uniquely illuminates the practice of law during a formative period in legal development and growth of the bar in the State of New York.

Source: Hamilton, Alexander. The Law Practice of Alexander Hamilton, Documents and Commentary: Vol. V Ed. Goebel, Julius Jr., Smith, Joseph H. Columbia University Press, 1981 pg. 8 [Link Here]

And one reader will use the Register to outline part of a historical fiction epic. Definitely the unconventional answer.

#grace’s random rambles#alexander hamilton#historical alexander hamilton#the law practice of alexander hamilton#legal history#new york legal history#the american icarus#TAI#historical fiction#writers on tumblr#american history#writing community#historical research#historical documents

8 notes

·

View notes

Note

Is it true that in early medieval ages a (potentially minor ) way to determine local rights / law was the word of the oldest person in town? A sort of anectodal oral record in addition to any hard evidence they may have written

Not just during the Early Middle Ages!

I've written about this a bit before, but in English and Anglosphere common law, there is a concept called "time immemorial" that describes when a given property right or use-right began, and makes it very difficult to change or challenge rights that are considered that old.

The traditional medieval formulation for "time immemorial" was that a given property, right, usage, or benefit had existed since "Time whereof the Memory of Man runneth not to the contrary." And in a medieval court of law, the way this period was established was by calling the oldest man in the parish to testify as to their memory - no other records required.

The reason why this method of ascertainment was used is that everyone understood that they were living in a society in which literacy rates were low and written records were uncommon. Thus, more weight was placed on oral tradition and human memory, which was encouraged by certain cultural traditions that sought to encourage the development of childhood memories associated with property rights.

For example, the custom of "beating the bounds" was established in which local communities would parade around the boundaries of their parish every seven years to remind everyone of where the boundary markers were supposed to be; while community leaders were encouraged to participate to demonstrate social solidarity, particular attention was paid to the participation of young children - who were variously either made to beat boundary markers with switches, were beaten with switches at boundary markers, had their heads knocked against the boundary markers, or were made to put their bare bottoms on the boundary markers.

I guess the idea was that symbolic violence or humiliation were believed to be a spur to memory formation.

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

“The price of freedom of religion or of speech or of the press is that we must put up with, and even pay for, a good deal of rubbish.”

Robert Houghwout Jackson was an American lawyer, jurist, and politician who served as an associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court from 1941 until his death in 1954.

Born: 13 February 1892, Spring Creek Township, Pennsylvania, United States

Died: 9 October 1954 (age 62 years), Washington, D.C., United States

Supreme Court Justice: Robert H. Jackson served as an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court from 1941 to 1954. He was appointed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Nuremberg Trials: Jackson is perhaps best known for his role as the chief United States prosecutor at the Nuremberg Trials after World War II. These trials were historic as they prosecuted major Nazi war criminals for crimes against humanity, war crimes, and genocide.

Legal Career: Before his appointment to the Supreme Court, Jackson held several significant positions, including Solicitor General (1938-1940) and Attorney General (1940-1941). His tenure in these roles was marked by his strong defense of New Deal legislation.

Influential Opinions: As a Supreme Court Justice, Jackson authored several important opinions. Notably, in West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette (1943), he wrote the majority opinion that declared it unconstitutional to force public school students to salute the flag, emphasizing the protection of individual rights against government mandates.

Literary Style: Jackson was renowned for his eloquent and clear writing style. His opinions are often cited for their literary quality and persuasive power. His legal writings continue to be studied and admired for their clarity and rhetorical force.

#U.S. Supreme Court Justice#American Lawyer#Jurist#Politician#Associate Justice#Nuremberg Trials#Chief U.S. Prosecutor#Legal Scholar#Constitutional Law#Spring Creek Township#Franklin D. Roosevelt Appointee#Solicitor General#U.S. Attorney General#Harvard Law School#Nuremberg Tribunal#International Law#Legal Ethics#Judicial Opinions#Legal History#Washington#D.C.#today on tumblr#quoteoftheday

3 notes

·

View notes