#Count Eric Stenbock

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Queer lit of the 1800s: Two gay Victorian vampire stories you've probably never heard of

So, I have this post in the works tackling that all-important question: just why are there so many gay vampire stories? But in writing it, what was supposed to be a brief tangent about a couple of little-known m/m vampire stories from all the way back in the late 1800s era… started expanding into something not-so-brief, as such tangents are prone to do.

But what the hell, the internet tells me it's queer history month: clearly the only solution is to give those stories their own post, where my tangent can spin out as far as it likes!

Now, if you know anything about Victorian vampire literature or the lesbian vampire genre, you’ve probably already heard about Carmilla, by Sheridan le Fanu (1872), the world’s very first (known) lesbian vampire story. To this day, it's easily the second best-known and widely adapted tale in all the Victorian vampire canon (after Dracula, obviously) – and it probably deserves to be too.

But this is not a post about Carmilla, because Carmilla is not the only gay-vampire-story written way back in the Victorian era. It's not even the least subtle gay-vampire-tale.

There are (at least) two others, both featuring male/male vampire/human pairings. And whether or not they ‘deserve’ to be remembered in the same breath as Carmilla, they’re both fascinating works in their own rights: Manor, by Karl Heinrich Ulrichs (1884) – one of the world’s first gay activists – and A True Story of a Vampire, by Count Eric Stenbock (1894).

You can read both online. A True Story of a Vampire is long out of copyright and can be found on Gutenberg (Carmilla is too, if you're interested), and many other places. Manor has been translated into English only much more recently, but you can still get hold of it in pdf form, or buy it in ebook format. But if what you really want are some summaries, and/or whole lot of extra context and analysis to go with the stories themselves, I've got you covered below.

Manor (1884), Sailor Stories, and Karl Heinrich Ulrichs

We’ll start with Manor, since it was published ten years before our other example, and because I’m not quite cruel enough to leave you going "wait, did you really just tell me there was a legit gay activist writing vampire slashfic in his free time way back in the 1880s?" while I ramble on about the other story first. We'll start with the author himself, because his own story is at least as interesting as any fiction he ever published.

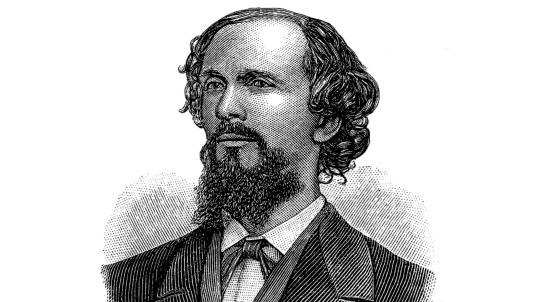

Born in Germany in 1825, Karl Heinrich Ulrichs knew from a young age that he was attracted to men. He trained in law, but wisely resigned before he could be fired in 1854 when his proclivities came to the attention of his superiors. Most in his position would've redoubled their efforts to hide; Ulrichs spent the next several years joining societies dedicated to science and literature and developing his own theories about non-hetero orientations, before officially coming out to his family in 1862.

He was just getting started. By 1867, he was ready to come out to the whole world.

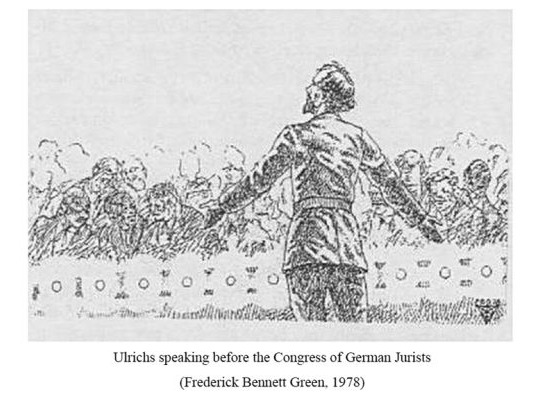

Ulrichs is far from the first gay man to recognise his attraction without shame and find society in like-minded individuals ‒ but he may well be the very first to come out voluntarily and publicly, and advocate for the decriminalisation of homosexuality. And when I say "publicly" what I mean of course is, "in a formal address to the Congress of German Jurists." He was shouted down, but it was still a staggering act of bravery for a man of his time. It would still be a staggering act of bravery in many parts of the world today.

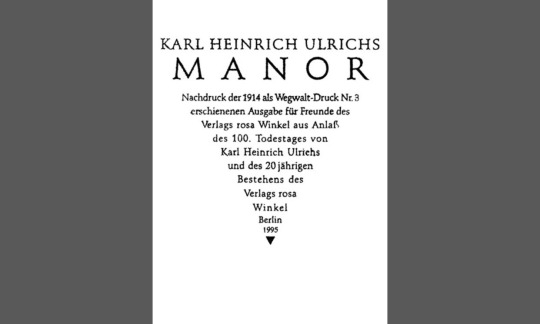

Undaunted by his reception, Ulrichs would also publish a dozen booklets advocating for rights for his community between 1864 and 1879, framing their sexuality as natural, inborn and wholly benign. In 1880, after multiple arrests for his political advocacy, he left Germany for self-imposed exile in Italy, where he would remain until his death in 1895. But it's during this period that he published some poetry, as well as Sailor Stories, a collection of four short stories inspired primarily by Norse mythology, including Manor (which we’ll get to, don’t worry).

Though Ulrichs saw little legal success in his lifetime, through modern eyes, his greatest failure might be only that he was so far ahead of his time. When he began writing and advocating, the word 'homosexuality' didn't even exist yet ‒ he himself used the term 'Urnings' for gay men, eventually coining terms for variations like 'Mannling' and 'Weibling' (gay male equivalent of 'butch' and 'femme') as well. He also came to recognise bisexuality, lesbian attraction, and even intersex conditions, theorising that all resulted from some combination of male and female characteristics developing in the same individual, as the available knowledge on embryonic development suggested might be possible. For a guy with only Victorian era science to work from, that's still remarkably close to the modern consensus today.

Nor did Ulrichs' work die with him. His writings would go on to inspire and be republished by gay rights movements that followed him ‒ including the work and advocacy of Magnus Hirschfeld, who created what may be the world's first trans-affirming clinic. Even in his own time, responses from his own readers show much his work meant to them, reassured at last that they weren't alone.

So how does a German activist from the 1880s find himself publishing gay vampire fiction based on Norse mythology while living in exile in Italy? I only wish I knew. My sources suggest his main goal with Sailor Stories was to publish something that would sell. Unsurprisingly, given the subject matter it seems to have sold very little. Manor is the third of four short tales, and by far the gayest of them all. It's also (IMHO) by far the best, and the most interesting.

Set in a Norwegian fishing village, Manor tells the story of the romance between a 15-year-old boy called Har, and the titular Manor, a sailor 4 years his senior, who rescues Har from the wreck which killed his father. In the days that follow, the pair become close, and Manor takes to swimming across the bay on summer evenings to visit Har at his home. And so they meet whenever they can, until tragedy strikes again, and Manor is killed in a shipwreck near the coast, leaving Har inconsolable with grief.

But this being a vampire story, in the nights after Manor’s death, something is seen swimming across the bay to Har’s home, just as Manor used to do. Har is visited night after night by the spectre of his beloved, who lies beside him in bed, strokes his cheek with cold hands, and kisses him with icy lips, draining his blood from his heart, "like an infant at its mother’s breast." Har himself awaits each night with mixed joy and fear, longing to see Manor again, even in such a form.

As Har weakens, the villagers attempt to trap Manor in his grave by hammering a stake through his body, but he continues to visit Har nonetheless, now sporting a gaping wound in his chest. The villagers return with a new stake, widened at the base like a giant nail, and finally, Manor is restrained in his grave. But it’s too late for Har: weakened and heartsick, he dies, begging only that he should be buried beside his beloved at last. Neither rise again.

Though I can’t speak to how it reads in the original German, in translation, Manor is relayed in largely workmanlike prose. Its tale is short, simple, and sad – but so much about it fascinates me all the same.

(Draugen, Theodor Kittelsen, 1891)

There’s the incorporation of elements you might better recognise from Norse draugr folklore – revenants more typically associated with deaths at sea, or charged with guarding their own graves ‒ but still far more closely related to the vampires of Slavic mythology than most people probably realise. Manor is also one of painfully few stories which clearly recognises what is surely the original purpose of hammering a stake through a vampire’s body: not to kill it, but to hold the creature down and prevent it from leaving its grave. As a hopeless vampire-nerd (I've presented panels at conventions about this stuff, it's dangerous to get me started), I can’t tell you how much I love those aspects of this story.

But above all, Ulrichs’ tale captures what might be one of the oldest and most traditional versions of the folkloric vampire: the spectre of a lost loved one, and the potent mixture of fear and twisted longing thus inspired, that the weight of their loss might drag you down into death to join them. Many ‘real’ tales of vampirism have been inspired by outbreaks of wasting diseases like consumption, working their way through a family, one member at a time. But in Har’s case, it is clearly grief as much as Manor’s physical visits that claims him. He loves Manor so much that he welcomes his lover back, even as a revenant. In his own way, Har too is cursed by Manor’s death to wander the world like the walking dead, until finally reunited with his lover once more.

Nowadays, tragic love stories like this tend to get an eye roll from a lot of the queer community. The old ‘bury your gays’ trope has been done to death, and we’re largely sick of being told that noble suffering is the best we can hope for. But it’s notable nonetheless that Manor’s sexuality has no bearing on his death, and little about the story would change were Har female. It's far from clear if the rest of the village even recognises Har and Manor's love for what it is, let alone whether they'd disapprove ‒ after all, vampires will often go after friends and acquaintances when lovers and family members are exhausted. As such, it’s hard to read the village’s attempts to keep Manor in his grave as a simple matter of prejudice. They're also genuinely trying to save Har's life.

And yet, the way Har keeps the undead Manor’s visits a secret, even begging for the stake to be removed so they can resume, echoes the real experiences of so many gay and lesbian couples far too clearly to be accidental. And however disturbing to a contemporary audience, Har’s willingness to follow his lover to the grave leaves little doubt of the depths of his feelings. To an audience in the 1800s, even the most cliched example of bury-your-gays would be revolutionary.

Did I mention that this story fascinates me? There are layers to this thing.

For completeness, I’ve also read the rest of Sailor Stories (and you can too at the same link). Only one of the other three tales contains any queer romance: the first, Sulitelma, where a boy called Erich falls for a handsome sailor called Harald he meets aboard a spectral storm ship. But there's no happy ending: his sister falls for the same handsome sailor, and shoves Erich overboard to his death to eliminate her competition.

Atlantis, the second story in the collection, is a direct sequel to Sulitelma, but it's even more bizarre. Erich is barely mentioned, and instead we find ourselves reading a tale which I can only summarise as like something I might have found on fanfiction.net back in the early aughts, written by some 14yo trying to straightwash the original material. Here, Harald and some of his fellows go on shore leave to the land of the phoenix, populated by Greek nymphs and Cupid, and mildly comedic hijinx ensue. It is fascinatingly bizarre, but not exactly satisfying as a read (or a sequel).

The final story, The Monk of Sumboe, tells of how two close friends destroy their relationship and themselves with their fixation on the tale of an alluring siren. There's a solid concept in there somewhere, but it's far too short and abrupt to do much with it, and all the characters remain strictly heterosexual. But if there's one thematic detail that ties it to the rest of the collection (beside the many Norse elements), it's that hopeless longing for something others would warn you away from ‒ whether that be a phantom ship, a visit from a vampire lover, or an elusive siren. None of these tales end well for their protagonists, but we're drawn to sympathise with them nonetheless.

I cannot guess what reception Karl Ulrichs expected in publishing this book. Sailor Stories is neither a work that could expect good reception from mainstream audiences or a defiantly-radical queer masterpiece. What did people make of it in its own time? Was it read and cherished by at least a few boys or men like Har and Manor? I’d hope so, but I’ll probably never know.

If you'd like to read more about Karl Ulrichs, I can recommend (among my sources) this New York Times article for a quick overview of his work, or the various work of Michael Lombardi-Nash and Hubert Kennedy (link 2). You can also read the first chapter of his published correspondence online for free.

A True Story of a Vampire (1894), and Count Eric Stenbock

Our second Victorian vampire tale was first published in English, though it was written by a Swedish Count. Like Carmilla in its own day (and quite unlike Karl Ulrichs), both story and author seem to have flown largely under the radar until many years after publication, the queer subtext little noted or commented upon (if at all).

If nothing else though, A True Story of a Vampire aptly demonstrates that at least someone of that era spotted what Carmilla was really about – because he wrote his own version, only about men. Stenbock’s tale is effectively a much shorter, gender-swapped version of Carmilla – but with a larger age gap between vampire and victim lending the story uncomfortable pederastic overtones.

"Vampire stories are generally located in Styria; mine is also," it begins – though I couldn’t name you any vampire story from the era besides Carmilla set there. The narrator, the surviving sister of the vampire’s victim, is called ‘Carmela’, if you needed further proof.

Much like in Carmilla herself, the vampire, Count Vardalek (a Slavic term for vampire) arrives at their house after being forced to seek local hospitality when some convenient ‘accident’ interrupts his travels. There, he bewitches and slowly drains the life from her brother, Gabriel – a boy described in terms variously angelic and fey, a wild thing who befriends wild animals and would rather climb a tree to a window than take the stairs to his own room, but who cleans up beautifully for church – a sublime, cinnamon roll of a creature, far too good for this sinful earth, too pure. Gabriel is a true male equivalent of the likes of Dracula’s Lucy, feminised further still by his youth and innocence. Had a vampire not got him, one can only imagine he’d have eventually have been spirited away by the fairies.

Gabriel and the mysterious Count are drawn to one another immediately. Even as Gabriel wastes slowly away, he greets Vardalek eagerly each time he returns by throwing his arms around his neck and kissing him on the lips. Count Vardalek himself seems to be a vampire of the psychic variety, gaining in health and vitality while Gabriel wilts, merely after spending time in one another’s presence. Vardalek himself seems to genuinely regret Gabriel’s inevitable death, but unlike in Carmilla, there’s no rescue at our conclusion. Gabriel dies, and we’re given no reason to assume he’ll rise again.

To the modern reader, the true horror of this tale lies not with the vampires or even the homoeroticism, but with those uncomfortably pederastic implications. Gabriel can’t be more than twelve years old, his youth and innocence emphasised in his every description. Pains are taken to suggest that Gabriel’s own attraction to Vardalek is as much responsible for his fate as the vampire himself. Gabriel’s father is similarly bewitched by this charming stranger, and never recognises the danger, or the reason for his son’s tragic death. Even the narrator, his loving sister, cannot truly hate Vardalek for taking her brother from her – even when her father dies of grief soon after. Gabriel’s fate seems sealed from the moment the Count enters their home.

But knowing how often real child molesters get away with it, their actions excused or downplayed by their family, their victims accused of ‘seducing’ their abusers and made complicit in their own misery… I can only say that, for my money, A True Story of a Vampire is a very effective horror story in ways the author probably never intended, once you start to question the reliability of its narrator.

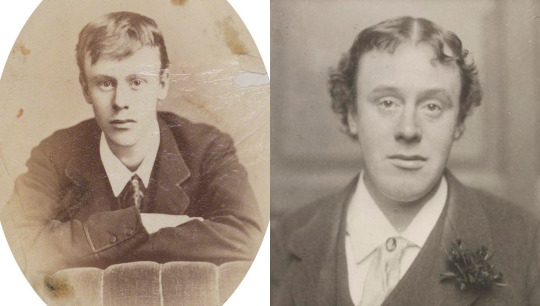

It won’t surprise you to learn that the author, Count Eric Stanislaus Stenbock, was a (very) gay man, deeply involved with the gothic and decadent artistic movements of his day. Born to a Swedish Count and an English heiress, Stenbock seems to be remembered less for his writing than for his character. In The Oxford Book of Modern Verse, 1892-1935, W.B. Yeats describes him as a "scholar, connoisseur, drunkard, poet, pervert, most charming of men" ‒ naming Stenbock as an exemplar of the poetic zeitgeist of the age. Notably however, none of Stenbock’s actual poetry is featured in the volume.

Stories about Stenbock are so bizarre that it’s hard to know how much should be believed. Eric Stenbock supposedly travelled with a multitude of exotic pets and a life-sized doll he referred to as his 'son', dabbled in religions ranging from Roman Catholicism to Buddhism, and decorated his dwelling with peacock feathers, oriental shawls, a bronze statue of Eros and a hanging pentagram. One acquaintance once compared him to a 'magnified child': "very fair hair beautifully curled, and a blond, round, blue-eyed face," who paused at the door and "took a little phial out of his pocket, from which he anointed his fingers, before passing them through his locks." But by his thirties, he was already dying of liver disease after years of alcoholism. He passed away at only 35.

Stenbock’s surviving artistic legacy consists of three volumes of poetry and one of prose, with some of those poems including explicit references to Ganymede or male lovers. So how did he escape the same controversy that dogged similar works by other queer creatives of his day, like Oscar Wilde or Walt Whitman – let alone Karl Ulrichs? Well, simple: his work never attracted enough attention to generate real controversy. Stenbock may have been just as much a character as figures like Wilde, but he hadn't nearly the same talent or success.

One last minor biographic detail that may be worthy of note (discovered courtesy of some very poor-quality scans of his one proper biography) is that the youthful Gabriel of A True Story of a Vampire may owe his name to a real Gabriele ‒ a female cousin ten years Stenbock’s junior, whom he would've spent time with in his teens, and seems to have been especially fond of. Whatever the true significance of that name, he'd use it more than once in his fiction: another short story, The Other Side: A Breton Legend, also stars an angelic little boy called Gabriel, with a similar dangerous attraction to the strange. It features some lovely mood and imagery as it sets the scene, but (perhaps as a result of the lack of a suitable model story like Carmilla) it is, in my opinion, a much weaker story overall.

But again, the most disturbing aspect of Stenbock's biography are the hints about his own relationships with much younger men. His second book of poetry, Myrtle, Rue and Cypress, is dedicated to three people: Simeon Solomon (a gay painter of the pre-Raphaelite movement, whom he met at Oxford), Arvid Stenbock, Eric's cousin, and to "the memory of Charles Fowler" ‒ the son of a Clergyman, who died of consumption at only 16.

This enigmatic dedication is all we know about Stenbock's relationship with Fowler. We don't even know how the they met (Fowler seems to have had a relative at Oxford at the same time as Stenbock, but even this is speculation). But that dedication, in a book which will go on to feature poems about the beauty of Ganymede, or explicitly addressed 'To A Boy' (Tis ever a delight, dear, To gaze upon thy face, To love the life within thee, Fair fashioned, full of grace) makes it hard to read Stenbock's feelings as remotely platonic.

It doesn’t help that the same volume includes a poem about an actual vampire, published ten years before A True Story of a Vampire would ever be penned, but with very comparable subject matter:

With slow soft sensual sips Draw the life from the tender spray, And brush from thy soft lithe lips The bloom of thy boyhood away

It's worth keeping in mind that Stenbock himself would've been only 21 at the time of Fowler's death, and that we don't know whether he ever acted on his attraction (whatever form it may have taken). He may well, as I've seen suggested, have kept his admiration private, idealising the image of the beautiful, dying boy in his final days, in that classic Victorian-gothic way. But it doesn't help that Stenbock's cousin Arvid, from that other dedication in the same book, was 8 years his junior, and that their family apparently disapproved of their relationship as "unnaturally close." Or that another famous Stenbock-associate was Norman O'Neil, a composer whom he met on a London omnibus in 1891, when O'Neil too was only 16. Stenbock was apparently taken by his intelligence and beauty, and would go on to leave him a considerable sum of money in his will. By 1891, Stenbock would've been 31, but his fixations hadn't aged with him.

So how are we to take all this? This was an age where a marriage between a 16-year-old girl and a suitor of Stenbock's age would scarcely have raised eyebrows. Uncomfortable as it may sound today, for many queer youths of the era, a romance with someone older and experienced enough to play mentor may genuinely have represented the safest real option available. There are layers of complicated subtext, meanwhile, in the idea of any gay man of the Victorian era casting himself as a vampiric monster, doomed to ruin the object of their attraction with their very touch. There may be layers more in Stenbock framing his tale as "A true story" before telling us of the misery a foreign Count brought to an innocent family, with his helpless fixation on their youngest child.

It's worth noting also that even in Manor, by Legit Gay Activist Karl Ulrichs, our love story is between a boy of 15 and a man of 19 ‒ an age gap of only 4 years, but large enough at 15 to raise some serious eyebrows. His first story too, Sulitelma, involves attraction between a man and a boy (exact ages unknown). Though Ulrichs explicitly viewed relationships with prepubescent children as reprehensible, he seems to have had no problem with relationships between young teens and much older adults ‒ even printing a story sent in by a reader (details in this article), joyfully recounting how he (the reader) was initiated into the world of male/male love as a 14-year-old by his brother's riding master. Ulrichs saw no reason to disapprove.

To confuse things for anyone looking this up today, google Ulrichs, and you'll find a number of online articles claiming that his own first experience involved being sexually assaulted by a riding instructor when he was only 14. This is wrong on multiple fronts: not only is the story related by Ulrichs as a positive experience, it wasn't even Ulrichs it happened to. No, shit like this would not be okay if it happened today (and frequently wasn't then), but we don't help ourselves by distorting the stories told by our queer forebears to fit modern expectations.

But none of that surrounding context makes the youth of the day any less vulnerable to predation, or Stenbock's fixation on youthful beauty less creepy. Today, no evidence remains to help us guess whether idealising the beauty and innocence of youth was the greatest of Stenbock's actual crimes, or the least of them. Anything is possible.

In brief: welcome to the joy of trying to reconcile the complicated place of pederasty in queer history! I'm afraid you can look forward to seeing a lot of it from here on back.

A True Story of a Vampire is not a bad work of fiction by any means. There are some lovely descriptions and entertaining turns of phrase, and the horror is certainly effective. It may even be considerably more readable than Carmilla to many, simply for being so much shorter. But how you feel about it is really going to be up to you.

One last digression about Carmilla and Christabel

There’s one additional work that I’ve once or twice seen listed as an even earlier queer vampire tale: Samuel Coleridge’s unfinished poem Christabel (1800) – the only problem being there’s no vampire in the story (and how queer it is may be questionable too).

Like Carmilla, Christabel tells of a Baron’s daughter (the titular Christabel) who comes upon a mysterious stranger in apparent distress (Geraldine) and invites her into her home. We never learn what kind of being Geraldine truly is (three further parts were planned in addition to the two that were completed), but when she undresses, Christabel spies something that horrifies her, remembering it later with the words "Again she saw that bosom old / Again she felt that bosom cold." But under Geraldine’s spell, Christabel’s recollection of this incident comes and goes, and Geraldine has soon bewitched her father too.

All ‘evidence’ that Geraldine was intended to be a vampire rests on such details as Geraldine having to be carried past an iron gate into the house, much as vampires have to be invited in – but that particular vampire trope wasn’t actually codified until a solid century later (like most vampire-tropes, we have Stoker's Dracula to blame). The idea that Geraldine has the cold, shrivelled body of the undead and revives herself on Christabel’s blood is a perfectly valid reading, but the more obvious interpretation would be that she’s some manner of shapeshifting fairy creature, weakened by the iron of the gateway, not the entrance to Christabel’s home. The aristocratic literary vampire had existed for over 40 years and appeared in numerous works of fiction by Carmilla's day; but Christabel predates the origins of the genre a solid two decades. For Coleridge to have come up with the idea independently seems vanishingly unlikely.

I mention Christabel here partly for completeness, but mostly to bring us back around to the greater family of Carmilla, which is still legitimately the first known queer vampire story. Though far better known than any other story discussed here today, how it came about is perhaps the most mysterious.

Sheridan le Fanu was a prolific writer, but I don’t know of any other story he’s penned with subtext like Carmilla's (and I’m not quite invested enough to read all of the rest to check, though someone totally should so I don't have to). Le Fanu was married, and had children, and that's all I can discover about his personal life. Was he some shade of queer himself? Did he have connections to anyone who was? Did he even realise what he was writing with Carmilla? Nothing I’ve read about him provides any answers. Nor can I tell you how many readers spotted the subtext it the story was first published. In its own time, it caused no great scandal, nor even seems to have garnered much attention (by contrast, Byron & Polidori's The Vampyre caused an uproar when it was published in 1819, mostly thanks to Byron's established fame and debates over its true authorship). It took until well into the 20th Century for it to obtain the reputation it has today.

But I’m sure it’s no coincidence that it was Carmilla that spoke to Stenbock enough that he chose to retell it. And while A True Story of a Vampire is still the only other vampire story of the era set in Styria, there was almost another one: Dracula, at least Stoker’s early plans for the novel. Styria also remains part of the unused prequel chapter later published as Dracula’s Guest. The setting isn’t the only detail Stoker nearly-borrowed from Carmilla either, my favourite example being the weird schedule by which both she and Dracula seem to have to be in bed in their coffins at dawn each day, both apparently helpless and immobile in sleep, though both are also repeatedly seen up and about later in the day. Neither tale offers any real explanation.

Have I mentioned lately that Stoker, too, was almost certainly some shade of gay?

Now, the fact that two different queer writers both found Carmilla so very inspiring – and would even both publish their own works of vampire literature within five years of one another – isn’t much to go on, in trying to establish what a story like Carmilla might’ve meant to England’s queer population some twenty years after it was written. Maybe Carmilla was being eagerly passed around London’s own Uranian gothic societies at the time. Or maybe two different men happened upon it by chance in wholly different circumstances, and took very different things from reading it. Maybe Stoker didn’t even notice the queer subtext himself. But I can’t help but wonder if just maybe, there's something more than coincidence at work here.

Carmilla the vampire is an explicitly villainous character, her victim confused and unwilling. But she remains one of the most complex and sympathetic vampires of her era. And perhaps, to a community who had never seen Ulrichs’ writing published in their own language, and might never see themselves represented in fiction except as monsters buried in layers of protective subtext, that still meant something to readers like Stenbock, and Stocker, and who knows how many others.

In short, maybe old, gay vampire stories like these really are worth remembering. I'll leave that one up to you.

#queer history#vampires#Dracula#Manor#Karl Heinrich Ulrichs#A True Story of a Vampire#Count Eric Stenbock#Carmilla#gay vampire stuff

86 notes

·

View notes

Text

The True Story of a Vampire by Count Eric Stenbock

"The True Story of a Vampire" by Count Eric Stenbock, published in 1894, is a haunting and evocative tale that delves into the dark allure of vampirism. The story is narrated by an old woman who recounts the tragic events that befell a noble family.

“The True Story of a Vampire” by Count Eric Stenbock, published in 1894, is a haunting and evocative tale that delves into the dark allure of vampirism. The story is narrated by an old woman who recounts the tragic events that befell a noble family when Count Vardalek, a mysterious and charismatic stranger, enters their lives. The Count exudes a sinister charm, gradually insinuating himself into…

#Count Eric Stenbock#featured#short stories#short stories set in Styria#The True Story of a Vampire#vampire short stories

0 notes

Text

Never trust a Swedish-Russian-Estonian- English count poet and author of the macabre, who probably had not seen the entirety of the Styrian region.

“Vampire stories are generally located in Styria; mine is also. Styria is by no means the romantic kind of place described by those who have certainly never been there. It is a flat, uninteresting country, only celebrated by its turkeys, its capons, and the stupidity of its inhabitants.” (“The Sad Vampire”)

All right, Count Eric Stanislaus Stenbock, whose anniversary of his interment falls tomorrow, I’ll forgive your ignorance as you lived during the Victorian era.

Graz, the region’s capital, is governed by the communists. I admit that their mentality is different from the Viennese. But Styria is considered to be the lung of the country because of how green it is. Don’t tell me there is nothing romantic in here. One Austrian archduke found his one true love in this region despite his family’s disappointment.

#altausseer see#count eric stanislaus stenbock#on#styria#photographic evidence#the sad vampire#count vardalek#my pics#salzkammergut

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

19th Century Vampire Lit I'm Gonna Read

Because I've lost my mind.

Most of these texts were found with the aid of these two posts. I did not include any of the stories listed as "not technically about vampires," except for "Let Loose," because it concerns a specter seeking blood, and "Vampirismus," because it's called "Vampirismus."

A strikethrough indicates that I've already read the work. Bold text indicates that I cannot find an English translation, whether online or for purchase. If you know of English translations of any bolded titles, please let me know.

Thalaba the Destroyer, Robert Southey (1801)

"The Vampire," John Stagg (1810)

The Giaour, Lord Byron (1813)

"A Fragment of a Novel," Lord Byron (1816)

"The Vampyre," John William Polidori (1819)

The Black Vampyre, Uriah Derick D'Arcy (1819)

The Vampire Lord Ruthwen, Cyprien Bérard (1820)

The Vampire, or The Bride of the Isles, J.R. Planché (1820)

The Vampire, Charles Nodier (1820)

"Vampirismus," E.T.A. Hoffman (1821)

Smarra, or Demons of the Night, Charles Nodier (1821)

"Wake Not the Dead," Ernst Raupach (1823)

The Vampire, or the Hungarian Virgin, Étienne-Léon de Lamothe-Langon (1825)

Der Vampyre und seine Braut, Karl Spindler (1826)

La Guzla, ou Choix de Poesies Illyrique, Prosper Merimee (1827)

"Pepopukin in Corsica," Arthur Young (1827)

The Vampire, Heinrich Masrschner and Wilhelm August Wohlbrück (1828)

The Skeleton Count, or the Vampire Mistress, Elizabeth Caroline Grey (1828)

Der Vampyre, oder die Totenbraut, Theodor Hildebrand (1828)

"The Vampire Bride," Henry Thomas Liddell (1833)

Clarimonde, Théophile Gautier (1836)

The Family of the Vourdalak, Aleksey Tolstoy (1839)

The Vampire, Aleksey Tolstoy (1841)

"The Vampyre," James Clerk Maxwell (1845)

Varney the Vampire, or The Feast of Blood, James Macolm Rymer (1845-1847)

The Pale Lady/The Carpathian Mountains/The Vampire of the Carpathian Mountains, Alexandre Dumas (1849)

"The Vampyre," Elizabeth F. Ellet (1849)

The Phantom World [select chapters], Augustin Calmet (1850)

The Vampire, Alexandre Dumas (1851)

The Vampires of London, Angelo de Sorr (1852)

The Dead Baroness/The Vampire and the Devil's Son, Pierre Alexis Ponson du Terrail (1852)

"The Vampire," Charles Pierre Baudelaire (1857)

Knightshade/The Shadow Knight, Paul Féval (1860)

"The Mysterious Stranger," Karl von Wachsmann (1860)

"Metamorphosis of a Vampire," Charles Pierre Baudelaire (1860)

The Vampire of the Val-de-Grace, Leon Gozlan (1861)

"The Vampire; Or, Pedro Pacheco and the Bruxa," William H.G. Kingston (1863)

The Vampire/The Vampire Countess, Paul Féval (1865)

Vampire City, Paul Féval (1867)

"The Last Lords of Gardonal," William Gilbert (1867)

Vikram and the Vampire, Sir Richard Francis Burton (1871)

"The Vampire Cat of Nabéshima," Algernon Bertram Freeman-Mitford (1871)

Carmilla, Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu (1872)

"Ghosts," Mihail Eminescu (1876)

Der Vampyr – Novelle aus Bulgarien, Hans Wachenhusen (1878)

Captain Vampire, Marie Nizet (1879)

"The Fate of Madame Cabanel," Eliza Lynn Linton (1880)

After Ninety Years, Milovan Glišic (1880)

"The Vampyre," Owen Meredith (1882)

"The Vampire," Jan Naruda (1884)

"Manor," Karl Heinrich Ulrichs (1884)

"The Vampyre," Vasile Alecsandri (1886)

The Horla, Guy de Maupassant (1887)

"Ken's Mystery/The Grave of Ethelind Fionguala," Julian Hawthorne (1887)

"A Mystery of the Campagna," Anne Crawford (1887)

"Romanian Deaths and Burials-Vampires and Werewolves," Emily Gerard (1888)

"The Old Portrait," Hume Nisbet (1890)

"The Vampire Maid," Hume Nisbet (1890)

"Let Loose," Mary Cholmondeley (1890)

"The Vampire," Felix Dahn (1892)

The Parasite, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (1884)

"The True Story of a Vampire/The Sad Story of a Vampire," Count Eric Stenbock (1894)

"A Kiss of Judas," Julian Osgood Field (1894)

"The Prayer," Violet Hunt (1895)

"Good Lady Duncayne," Mary Elizabeth Braddon (1896)

"The Vampire of Croglin Grange," Augustus Hare (1896)

"Phorfor," Matthew Phipps Shiel (1896)

Dracula, Bram Stoker (1897)

"Dracula's Guest," Bram Stoker (1914*)

The Blood of the Vampire, Florence Marryat (1897)

*"Dracula's Guest" was first published in 1914 but was written either concurrent to or before the writing of Dracula.

I'm going to be honest. When I began, I thought there were four nineteenth century vampire stories. Five if you count Dracula's Guest. I've made a huge mistake.

#vampires#vampire fiction#vampire literature#19th century fiction#19th century literature#Gothic fiction

186 notes

·

View notes

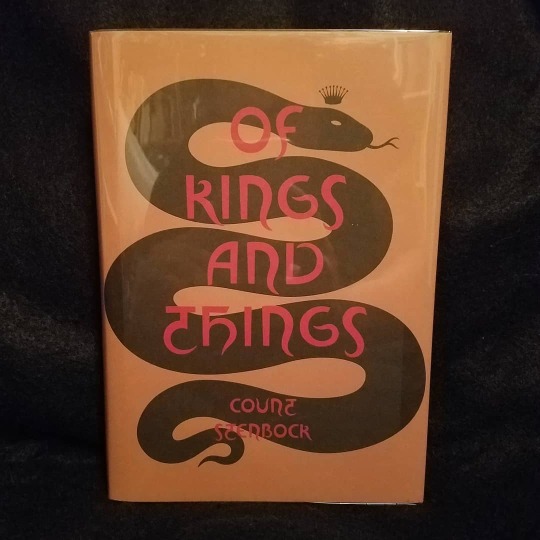

Photo

Front cover to a collection of macabre stories by the enigmatic Count Eric Stenbock, published a year before his death #onthisday in 1895. More on this Decadent figure par excellence in our essay by David Tibet: https://publicdomainreview.org/essay/eric-count-stenbock-a-catch-of-a-ghost

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

Midnight Pals: Large Adult Son

Eric Stenbock: hello midnight society Stenbock: i'm Count Eric Stanislaus Stenbock Stenbock: [producing life-size mannequin] and this is my son le Petit Comte Thomas Ligotti: Ligotti: Ligotti: Ligotti: Stephen King: you're uh King: really staring at that mannequin kinda intently there, tom Ligotti: hm

Eric Stenbock: submitted for the approval of the midnight society, i call this the true story of the vampire Stenbock: one sec, let me just get le Petit Comte comfortable first Stenbock: how are you doing le Petit Comte Stenbock: Ligotti: Stenbock: Ligotti: Stenbock: Ligotti: Stenbock: he says he's doing good

RL Stine: hey does your puppet talk Stine: my puppet talks Stenbock: does my what talk? Stine: your puppet Stenbock: Stenbock: you mean my son? Stine: yeah your puppet there Stenbock: Stenbock: never speak to me or my son every again

RL Stine: i just wanted to know if le petit comte talks RL Stine: [producing ventriloquist dummy] cuz knothead here talks RL Stine: especially when i drink a glass of water RL Stine: watch he'll sing the old gray mare Stenbock: how dare you

Stenbock: submitted for the approval of the midnight society, i call this the true tale of a vampire Stenbock: it's the story of carmilla Sheridan Le Fanu: Stenbock: not THAT carmilla Stenbock: a totally different carmilla

Stenbock: this carmilla story is not to be confused for sheridan la fanu's carmilla Stenbock: for one thing, this isn't a lesbian vampire story Stenbock: it's a gay vampire story Stenbock: extremely gay Bram Stoker: oh no Anne Rice: oh yes

Stenbock: so carmilla lives in a castle with her sexy brother gabriel and their dad Stenbock: and she's narrating this story so Stenbock: she's all "hey its me carmilla, let me tell you what i look like" Stenbock: "i'm just an average girl, but i think i'm pretty hot" Stenbock: "but boy my brother, damn what a smoke show" Stenbock: "pouty youthful mouth, tangled blonde locks, the whole deal" Stenbock: "you know how it is"

Stenbock: "so my brother was so kind and gentle, filled with nothing but love" Stenbock: "just loved animals" Stenbock: "and animals loved him" Stenbock: "he was a delicate cinnamon bun too good for this cruel bitch of a world"

Stenbock: "anyway this vampire comes to our castle" Stenbock: "and he's always hanging out with my brother" Stenbock: "but my brother is suddenly all sick and pale and doesn't have as much blood as usual" Stenbock: "suspiciously vampiric"

Stenbock: "anyway then my brother died and the vampire left, the end" Stenbock: what do you think of that Ligotti: Ligotti: Ligotti: King: thom it's not going to move, it's not real Ligotti: hm

#midnight pals#the midnight society#midnight society#stephen king#eric stenbock#rl stine#thomas ligotti#anne rice#bram stoker#sheridan le fanu

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

Viol d'Amor by Count Stanislaus Eric Stenbock

Count Stenbock was a 19th century nobleman of Swedish descent who held a domain in what is now Estonia. His father died when he was a boy, as did his maternal grandfather, so he was incredibly wealthy for much of his life, although his property was administered for him by his paternal grandfather during childhood. Many of his other relatives perished during his youth, so he was always a bit…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Quote

Then the voice became sadder than ever: “There is another they call the Redeemer, (here the voice varied between scoffing and sadness) He suffered for a few hours and I suffer always. Yet even to Him I was merciful. I offered Him all the Kingdoms of the earth if He would but worship me, for I thought to love Him as I love thee. They put His cross on their crowns, and trample down the people in His name. I am the consoler of the afflicted - the friend of the poor and down-trodden. The refuge of sinners - the seat of wisdom; the morning star - the chief of angels. I will leave one sign" he said, "to show that my visit was real," and here something was pressed into my hand.

from Faust by Count Eric Stanislaus Stenbock

#Count Eric Stanislaus Stenbock#Faust#Lucifer#Christ#Jesu#Jesus#Jesus Christ#current 93#david tibet#the moons at your door#strange attractor#strange attractor press#luciferian#lcf#satanas#satan#redeemer#crucifixion#cross#good friday#easter#morning star#fallen star

21 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Count Stanislaus Eric Stenbock, Of Kings and Things: Strange Tales and Decadent Poems, edited by David Tibet (London: Strange Attractor Press, 2018). 319 pages. Hardcover special edition, signed by David Tibet. https://www.ebay.com/itm/254537626729

#count stenbock#stenbock#count stanislaus eric stenbock#decadent#decadence#decadent literature#symbolist literature#occult#weird fiction#limited edition#hardcover#signed copy#david tibet#strange attractor press

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kolga ♥

#kolga manor#kolga#35 mm#35 mm film#analog photography#Count Eric Stanislaus Stenbock#Stenbock#gudrun heamägi

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Because I am a masochist, I decided I wanted to read all the 19th century vampire literature. Currently I'm focusing on short stories and novels rather than plays.

I have read:

The Vampyre - John William Polidori

Varney the Vampire, or The Feast of Blood - James Malcolm Rymer

Dracula - Bram Stoker

Dracula's Guest - Bram Stoker

I have not yet read:

Fragment of Novel - Lord Byron

The Black Vampyre - Uriah Derick D'Arcy

Lord Ruthwen; ou, Les Vampires/Lord Ruthwen of the Vampires - Charles Nodier

Vampirismus - E.T.A. Hoffman

La Morte Amoureuse/Clarimonde - Théophile Gautier

The Vampyre - Elizabeth F. Ellet

Spiritual Vampirism - Charles Wilkins Webber

Le Chevalier Ténèbre/Knightshade - Paul Féval

La Vampire/The Vampire Countess - Paul Féval

La Ville Vampire/Vampire City - Paul Féval

Carmilla - J. Sheridan Le Fanu

Strange Event in the Life of Schalken the Painter - J. Sheridan Le Fanu

The Fate of Madame Cabanel - Eliza Lynn Linton

Ninety Years Later - Milovan Glišić

Manor - Karl Heinrich Ulrichs

A Mystery of the Campagna - Anne Crawford

Let Loose - Mary Cholmondeley

Le Captine Vampire/Captain Vampire - Marie Nizet

The True Story of a Vampire - Eric Stenbock

The Vampire - Alexei Tolstoy

The Family of the Vourdalak - Alexei Tolstoy

The Reunion After Three Hundred Years - Alexei Tolstoy

The Prayer - Violet Hunt

The Blood of the Vampire - Florence Marryat

The Vampire of the Val-de-Grace - Léon Gozlan

The Vampire and the Devil's Son - Pierre Alexis Ponson du Terrail

Wake Not the Dead - Ernest Rapauch

The Vampire of the Carpathian Mountains - Alexandre Dumas

The Pale Lady by Alexandre Dumas

Pepopukin in Corsica - Arthur Young

Good Lady Duncayne - Mary Elizabeth Braddon

Luella Miller - Mary E. Wilkins Freeman

The Skeleton Count, or The Vampire Mistress - Elizabeth Caroline Grey

The Virgin Vampire - Étienne-Léon de Lamothe-Langon

The Phantom World - A.A. Calmet

Death and Burial: Vampires and Werewolves - Emily Gerard

And the Creature Came In - Augustus Hare

The Tomb of Sarah - F.G. Loring

And then there is this book which I don't even know if I can read, because I've yet to find an English translation and don't know if it even has one:

Der Vampyr – Novelle aus Bulgarien - Hans Wachenhusen

Are there any others I'm missing? Are any of those not actually vampire stories or not from the nineteenth century and I've been misled?

As to why the nineteenth century: I think if I tried to read all vampire stories EVER it would take the entire rest of my life and then some, and also early vampires are fascinating to me because all the standard tropes were not yet in effect.

As to why I'm doing this at all: Who even knows. I need things to distract my brain.

24 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Front cover to a collection of macabre stories by the enigmatic Count Eric Stenbock, published a year before his death #onthisday in 1895. More on this Decadent figure par excellence in our essay by David Tibet: https://publicdomainreview.org/essay/eric-count-stenbock-a-catch-of-a-ghost

55 notes

·

View notes

Quote

‘Tis a soft bed, a feathery pillow, Oh, let me rest upon thy wave; Lull me to sleep upon thy billow, And let thy waters be my grave.”

S.E. Stenbock, excerpt from the poem Ode to the East Sea (Love, Sleep & Dreams, 1881)

#S.E. Stenbock#count stenbock#eric stenbock#poetry#romantic poetry#romanticism#writer#stanislaus eric stenbock

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

a black rosette of Count Eric Stenbock

Sebastian Blue Pin & living mannequin at large!

1 note

·

View note

Text

A strange delicious scent, mingled of honeysuckle, jasmine, incense and spices. Then before me there was a faint glimmer of rose-violet colour, bordered with silver, from which the scent seemed to emanate. Then the light grew brighter, and in the midst thereof there was an apparition, something incomparably and entirely beautiful. It was a figure entirely nude, shaped like the Greek Hermaphrodite. But, oh, how much more beautiful! All conceivable beauties of both sexes were blended in its beautiful lines. The face was beyond description in its incredible loveliness. Its long hair was bronze coloured, with threads of gold. The mouth was infinitely sweet, the eyes, which were of dark violet, infinitely sad. [...] The figure advanced towards me - it threw its arms around me and kissed me. A sensation of extreme pleasure penetrated every nerve of my body. Then the vision seemed to melt into a dream; I had certainly fallen asleep, but the voice spoke still. It told a long account of the entire history of the universe; how it was created by a malignant god, and how he was the Redeemer, and how all that was beautiful on the earth was his work and if he had assistance from those whom he sought to benefit, all things would come again to their original fair order, and that he should come to his own inheritance again. Then the voice became sadder than ever: “There is another they call the Redeemer, (here the voice varied between scoffing and sadness) He suffered for a few hours and I suffer always. Yet even to Him I was merciful. I offered Him all the Kingdoms of the earth if He would but worship me, for I thought to love Him as I love thee. They put His cross on their crowns, and trample down the people in His name. I am the consoler of the afflicted - the friend of the poor and down-trodden. The refuge of sinners - the seat of wisdom; the morning star - the chief of angels.”

Count Eric Stanislaus Stenbock, Faust

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Midnight lit corner: Count Eric Stenbock is one of my favourite historical figures. “At the end of his life his indulgences had taken a toll on his health, so he retired to the Riviera with his doctor and a life-sized doll he referred to as his son and heir.” — There is also an unconfirmed rumour that Oscar Wilde casually visited his estate and lit a cigarette on Stenbock’s personal shrine which caused him to lose his shit and wail on the floor, leading Wilde to step over him and walk out like a cold motherf*cker. Anyway, Wilde wasn’t a fan of his eccentric contemporary.

On a related note, bring back decadence 🥂

1 note

·

View note