#Ferdinand Gregorovius

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

cesare is never beating the widowmaker allegations

#lucrezia and juan's wife parallels save me ???#while we don't exactly know if it's historically true but i chuckle at how showtime's version portrayed him like this#juan's wife would've added so much juice to the show considering how real maria accused cesare of killing her husband aka his brother#she even commissioned a portrait of cesare about to backstab an oblivious praying jesus-looking juan#while neil jordan had lucrezia flee from rome to a nunnery to escape her father and brother's vicious web of ambitions...#historically rodrigo exiled her to naples against her will because apparently her “bitter” weeping over her husband had “embarrassed him”#and he only kept cesare around him...misogyny :/#the borgias#cesare borgia#juan borgia#maria enriquez de luna#lucrezia borgia#lucretia borgia according to original documents and correspondence of her day#ferdinand gregorovius#historical drama#historical fiction#history#borgia#borgias#tb text post

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lettura del libro «Passeggiate per l'Italia» di Ferdinand Gregorovius

L’opera di Ferdinando Gregorovius, intitolata «Passeggiate per l’Italia» raccoglie in cinque volumi le escursioni in Italia che lo storico tedesco fece tra il 1856 e il 1877, e costituisce ancora oggi uno degli scritti più affascinanti e poetici della letteratura di viaggio. Non fuggevoli impressioni ma esperienze, rappresentazioni pittoresche di paesaggi e città, frutto di uno studio accurato e…

#audiolibri#Ferdinand Gregorovius#Grand Tour#Italia#letture#Memorie#pagine#Passeggiate per l&039;Italia#podcast#scrittori europei

0 notes

Text

youtube

TODAY IN PHILOSOPHY OF HISTORY

Ferdinand Gregorovius and Meso-History

Friday 19 January 2024 is the 203rd anniversary of the birth of Ferdinand Gregorovius (19 January 1821 – 01 May 1891), who was born in Neidenburg, East Prussia (now part of Poland) on this date in 1821.

Gregorovius’ great work, Geschichte der Stadt Rom im Mittelalter (1859–1872), translated into English as The History of Rome in the Middle Ages (1894–1902), envisioned Rome as an exemplary city within an historical stream of embodied ideas.

Quora: https://philosophyofhistory.quora.com/

Discord: https://discord.gg/r3dudQvGxD

Podcast: https://podcasters.spotify.com/pod/show/nick-nielsen94/episodes/Ferdinand-Gregorovius-and-Meso-History-e2el9uu

0 notes

Text

Roma ~ Werner Bergengruen · [1]

PIAZZA DI SPAGNA con la fontana della « Barcaccia » di Pietro Bernini (1562-1629) e la scalinata che conduce alla chiesa di Trinità dei Monti Precarietà ed immortalità di Roma quasi si toccano, anzi si fondono come in nessun’altra città al mondo. Si toccano e si fondono l’allegria e la tristezza, il frastuono ed il silenzio, la fretta e la calma, l’angustia e la larghezza che diventa quasi…

View On WordPress

#Ferdinand Gregorovius#Franz Xaver Kraus#Giovanni Battista Piranesi#Goethe#Hermann Grimm#Jean Paul#Roma#Werner Bergengruen

0 notes

Text

The House of Borgia: Sources and Scholarship

| Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 |

When I got my hands on Mirror, Mirror by Gregory Maguire, my plans were simple: read the book, do a write up about it and include a few notes here and there about who were the Borgias, the real family which Maguire re-imagines in a fairy tale setting. I did not expect that research into the Borgias would turn into a months long endeavour.

The result of all my efforts were a four parts series in which I try to lay out the known events and separate them from the myths and rumours that were spread about the family. I'm actually very proud of those posts, I love doing research (I mean... I love doing a good literature review, basic research is not much of my thing).

One thing that pissed me off a lot when researching was that I had no access to primary sources. I had to trust when an author said that "letters from the period confirm this". Like, tell me which letters and where they are, even if I can't actually access them because they were never digitalized, at least I would have names, years and quantity of letters.

As someone involved in academia, I know that the information I present is only as good as my sources. I didn't want to go doing in text citations because it can get very boring and also takes a lot of space. So, below, I present my references, and under the cut, I'll explain how I used each book. This way, I can have a clean conscience knowing that I did cite my sources.

References:

Batllori, M. La familia de los Borjas. Real Academia de la Historia, 1999.

Bradford, Sarah. Cesare Borgia: his life and times. Macmillan, 1976.

Bradford, Sarah. Lucrezia Borgia: Life, Love, and Death in Renaissance Italy. Penguin, 2005.

Burchard, Johann. Pope Alexander VI and His Court Extracts from the Latin Diary of Johannes Burchardus. Edited by F. L. Glaser, N.L. Brown, 1921.

Carrasco, Raphael. The Borgia Family. Presses universitaires de la Méditerranée, 2013.

Gregorovius, Ferdinand. Lucretia Borgia According to Original Documents and Correspondence of Her Day. D. Appleton and Company, 1903.

Meyer, G. J. The Borgias: The Hidden History. Bantam, 2013.

Morris, S. Cesare and Lucrezia Borgia: Brother & Sister of History's Most Vilified Family. Pen & Sword Books, 2020.

Strathern, P. The Borgias: Power and Depravity in Renaissance Italy. Pegasus Books, 2019.

La familia de los Borjas, by M. Batllori

This book was used in the first few paragraphs. It's where I got the information of the Borja's genealogy and origens. The book is in Spanish and I don't speak Spanish, but it's similar enough to Portuguese that I was able to identify passages of interest and then send them to my uncle's girlfriend, who is a Spanish professor.

Cesare Borgia: his life and times, by Sarah Bradford

I used this one to get more details about Cesare's campaign in Romagna (which didn't end up being in the final post) and also to cross reference dates and events.

Lucrezia Borgia: Life, Love, and Death in Renaissance Italy, by Sarah Bradford.

Used for details over Lucrezia's weddings and time in Spoleto.

Pope Alexander VI and His Court Extracts from the Latin Diary of Johannes Burchardus, by Johann Burchard

This is the journal of Rodrigo Borgia's master of cerimonies, translated and edited by F. L. Glaser. It's where some allegations originate, specially the Banquet of Chestnuts.

The Borgia Family, by Raphael Carrasco

Used to cross-reference and confirm information I found in other books.

Lucretia Borgia According to Original Documents and Correspondence of Her Day, by Ferdinand Gregorovius

Used in my Mirror Mirror post to fact check Lucrezia whereabouts. It's a collections of letter for her, from her or about her.

The Borgias: The Hidden History, by G. J. Meyer

This book sucks. Meyer presents of evidence for his claims that Rodrigo wasn't the actual father of Cesare and Lucrezia, and also tries to convince the reader that Rodrigo was a good man and did nothing wrong. And while I do think there was a defamation campaign against the Borgias, I also think there's no way that everyone was in it and that everything was forged. However, it did provide some background on the Italian political scene of the time.

Shitty book. I might just do a whole post complaining about it. Also, you know what Meyer doesn't do? Cite sources! He just claims things and expects us to take it at face value. His one source is Peter de Roo, who all other author claim was extremally biased and had an agenda to make Pope Alexander V (a.k.a. Rodrigo Borgia) seem a decent guy.

Cesare and Lucrezia Borgia: Brother & Sister of History's Most Vilified Family, by S. Morris

Once again, used to check if the information I was getting was indeed what was most accepted by modern historians.

The Borgias: Power and Depravity in Renaissance Italy, by P. Strathern

This is the best of the bunch. It was the first book I picked up about the Borgias and what my first draft of the post was based upon. From there, I picked other books that Strathern used as a source and then what those books were citing. Absolutely amazing work in my opinion, but I couldn't find what actual scholars think of the book (Strathern is not a historian). I think it was very unbiased and cited it's sources and didn't leap into any conclusion. But if it turns out I'm wrong, I'll gladly revisit this series and re-write using more academic accredited works.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why The Italian City of Lecce Is Nicknamed 'The Florence of The South'

Rich in honey-hued basilica's and elaborately decorated baroque cathedrals, the Southern Italian city of Lecce is often regarded as the 'Florence of the South'.

— By Angela Locatelli | October 5, 2024

The construction of Basilica di Santa Croce took over 140 years to complete, boasting a grand facade. Photograph By Francesco Lastrucci

It’s not easy to carry a basilica on your shoulders, but, despite the summer heat, these men aren’t breaking a sweat. Carved into the honey-hued exterior of the Basilica di Santa Croce, the stone figures kneel in a line from one side of the wall to the other, seemingly supporting the upper facade with their bare hands. Above them, the building is so richly decorated as to seem in motion: cherubs swirl in a spiral and garlands of pomegranate and acanthus leaves rise, reaching fever pitch where they all circle the central rose window. “Construction began in 1549,” says local guide Anita Maggiulli. “But it took over 140 years to complete.”

It seems to have been worth it, as the church has become the symbol of the city. I’m on a half-day tour of Lecce, the biggest urban centre of Salento, the tip of the heel to the Italian peninsula’s boot. It’s an area that distils what the wider region of Puglia is known for: white-washed hamlets, long stretches of sandy beach and the crystal-clear waters of the Ionian and Adriatic Seas. But this city in the hinterland has a different claim to fame — its grand, expertly carved architecture, which has earned it the moniker ‘Florence of the South’.

Baroque paintings frame the interior of Lecce Cathedral, located within the Piazza del Duomo (Left). In Lecce's city centre, many shops can be found selling local specialties (Right). Photographs By Francesco Lastrucci

According to Anita, while the nickname is often associated with German historian Ferdinand Gregorovius, it was first thought up by George Berkeley, an Irish bishop who travelled through Puglia in the 18th century. At a time when the Italian south was seen as unsafe and lawless, he reached the peripheries and found a city with protective walls, some 140 churches and, above all, magnificent facades. “He was left… disconcerted,” Anita says, mimicking a mix of surprise and confusion. “He described it as a place that had nothing to envy Rome or Venice, and even resembled a small Florence.”

If the Tuscan capital had been the cradle of the Renaissance, Lecce came to exemplify the Baroque era. The opulent art form originated in Rome in the 17th century, when the Vatican fought the threat of Protestantism the way it knew best — through an ostentatious display of power. As the style spread southward, it took on a local twist. “We couldn’t play with dimensions like the Romans, nor employ prestigious materials like the Neapolitans,” says Anita. “But we’d been blessed with a ‘poor’ material that allowed us to create marvels: Lecce stone.”

The former Hospital of the Holy Spirit is made out of Lecce stone. Photograph By Francesco Lastrucci

When it comes to this type of limestone, there are three key takeaways: it’s extracted in quarries around Lecce; it once formed the bed of an ancient sea, and to this day, you can find shells and fossils caked in its slabs; and it’s so malleable, it can be carved with a penknife. “It’s as soft as mollica,” says Anita, comparing it to the interior of a bread roll, as we move away from Santa Croce. “It became the defining characteristic of the Lecce Baroque.”

The city centre is almost entirely tinted in the stone’s characteristic warm, off-white shade. And while the Baroque approach was initially reserved for churches and mansions, large swathes of the city came to be rebuilt in its style. Locals wander around, unaffected by the open-air museum on display above their heads: the window lintels carved with scallop shells; the doorways flanked by Corinthian-style pillars; the balconies with stately balustrades.

Over the past 30 years, local artisans have started experimenting with a more modern approach to stonemasonry, too. One of the first was sculptor Renzo Buttazzo, now in his 60s, who greets me the next morning outside his home-turned-studio on the outskirts of San Cesario, a 10-minute drive from Lecce.

“Hot, eh?” he says in his garden by way of greeting, tugging at his grey linen shirt to fan himself. “I hold stonemasonry workshops here, to show visitors there’s more to Salento than sun and sea,” he tells me. “If you want to truly get to know the area, you must meet the people who built it up.”

Within his San Cesario workshop, sculptor Renzo Buttazzo experiments with modern stonemasonry techniques. Photograph By Angela Locatelli

Here, he builds, both figuratively and literally. At the far end of the garden, there’s a small exhibition space for his Lecce stone works. The ceiling is see-through; the daylight washes down on his sculptures, displayed on wooden pedestals all around the walls. There are sinuous figures with neither face nor features, and molecular-like forms that seem to contract and expand, with no angles or hard lines, no beginnings or ends. They’re a study in oxymorons: something solid that seems soft, something heavy that looks feather-light.

When describing his approach to working with Lecce stone, Renzo uses the word sconvolgere, an Italian verb for the act of shaking something out of its status quo. In the early 1990s, when artisans still used the material to sculpt angel-like putti and seraphim, Renzo was turning it into everyday objects, like clocks and lamps, before progressing to abstract sculpture. In 2001, he was honoured with the Order of Merit of the Republic, the Italian equivalent of being knighted.

“I take the old — the Baroque — to create the contemporary,” Renzo tells me as he flip-flops back outside in battered sandals, his soles chalk-white from the stone residue dusting the floor. “We local stonemasons come from a long legacy of excellence, and we have a duty to carry it forward. Our predecessors built something as magnificent as Santa Croce with their hands. Four centuries on, I work the same way.”

He reaches his workstation, a table on a covered patio surrounded by scattered tools, and turns his attention to a work in progress. He positions a wooden scalpel, then hits it with a hammer to sculpt sections from the undulating, hollow figure. A rasp is used to model its curves; sandpaper to shave its surface smooth. “Sometimes I’m here for 10 hours a day, and I come away exhausted,” he says, eyebrows furrowed, taking a step back to size up his efforts. “It’s not easy, you know — gifting people beauty.” And yet, as his face softens, pleased by the results, all I can think is how easy he makes it look.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

“The striking talents of Gregorovius are occasionally marred by the egotism and pedantry sometimes characteristic of the scholars of his nation. He is too positive; he seldom opines; he asserts with finality the things that only God can know; occasionally his knowledge, transcending the possible, quits the realm of the historian for that of the romancer, as for instance -to cite one amid a thousand- when he actually tells us what passes in Cesare Borgia's mind at the coronation of the King of Naples. In the matter of authorities, he follows a dangerous and insidious eclecticism, preferring those who support the point of view which he has chosen, without a proper regard for their intrinsic values. He tells us definitely that, if Alexander had not positive knowledge, he had at least moral conviction that it was Cesare who had killed the Duke of Gandia. In that, again, you see the God-like knowledge which he usurps; you see him clairvoyant rather than historical. Starting out with the positive assertion that Cesare Borgia was the murderer, he sets himself to prove it by piling up a mass of worthless evidence, whose worthlessness it is unthinkable he should not have realized. “According to the general opinion of the day, which in all probability was correct, Cesare was the murderer of his brother." Thus Gregorovius in his Lucrezia Borgia. A deliberate misstatement! For, as we have been at pains to show, not until the crime had been fastened upon everybody whom public opinion could conceive to be a possible assassin, not until nearly a year after Gandia's death did rumour for the first time connect Cesare with the deed. Until then the ambassadors' letters from Rome in dealing with the murder and reporting speculation upon possible murderers never make a single allusion to Cesare as the guilty person. Later, when once it had been bruited, it found its way into the writings of every defamer of the Borgias, and from several of these it is taken by Gregorovius to help him uphold that theory.”

Rafael Sabatini, The Life of Cesare Borgia , Chapter IV. When one scholar so eloquently spills the tea about another scholar's bs:

#cesare borgia#ferdinand gregorovius#rafael sabatini#house borgia#to be fair the whole historian to romancer and clairyant thing is not something gregorovius is alone at#bellonci certainly wins it though dhsdsdhs#but all borgia scholars that i have read so far do that to an extent#even sabatini himself#but still i appreciate him a lot for what he said here#his ~~spilling the tea~~ moments are one of the reasons why despite some annoying things he does on his bio#his work remains one of my faves#<3

18 notes

·

View notes

Quote

For only the narrowest observer, blind to everything but their infamous deeds, can paint the Borgias simply as savage and cruel brutes, tiger-cubs by nature. They were privileged malefactors, like many other princes and potentates of that age. They mercilessly availed themselves of poison and poignard, removing every obstacle to their ambition, and smiled when the object was obtained.

Ferdinand Gregorovius, Lucretia Borgia: According To Original Documents and Correspondence of Her Day

#cesare borgia#rodrigo de borgia#alexander vi#pope alexander vi#lucretia borgia#ferdinand gregorovius#akio ohtori#im not tagging this with anthy since. Well#Not Applicable#hmm you know what i will tag this with?#flower crown madonna#i didn't tag this with 'the borgias' bc i. know there's a show with that title and.#i want to get notes yes but i dont want to specifically attract that crowd....#granted i know very little about it#im indisposed to though#i have absolutely no interest in any fiction about these people that doesn't predate utena#unless chiho saito were to write it i guess. idk what she's been up to these days#besides BL and After the Revolution

18 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Nuovo post su http://www.fondazioneterradotranto.it/2019/04/10/viaggiatori-tedeschi-nel-sud-italia/

Viaggiatori tedeschi nel Sud Italia

di Paolo Vincenti

L’interesse dei tedeschi per il sud Italia parte da lontano. Già nel Cinquecento, Paul Schede detto Melissus (1539-1602) parlò di Rudiae negli Epigrammata in urbes Italiae del 1585 (1). Johann Heinrich Bartels (1761-1850) visita il Sud ma solo la Calabria e la Sicilia, verso la fine del Settecento, e documenta il suo viaggio nell’opera Briefe über Kalabrien und Sizilien. Dieterich, Göttingen 1787–1792 (2). Nel Settecento, arrivano in Italia il Barone von Riedesel e il pittore Jacob Philipp Hackert. Abbiamo già detto del tedesco Johann Hermann von Riedesel, barone di Eisenbach (1740-1785) e del suo libro, Un viaggiatore tedesco in Puglia nella seconda metà del sec. XVIII. Lettere di J.H.Riedesel a J.J.Winckelmann, che è, come dice il titolo, un’opera epistolare, diretta al famoso archeologo Winckelmann (3).

Diplomatico e ministro prussiano, Riedesel aveva conosciuto a Roma e frequentato il Winckelmann, il quale gli aveva fatto da guida nella esplorazione dei monumenti della città. Il suo libro divenne un punto di riferimento in Germania e fu molto letto, anche da Goethe, che lo elogia nella sua opera “Viaggio in Italia”, in cui sostiene di portarlo sempre con sé, come un breviario o un talismano, tale l’influenza che quel volume, per la puntigliosità e l’esattezza delle notizie, esercitava sugli intellettuali (4).

Jacob Philipp Hackert (1737-1807), nella sua opera pittorica I porti delle Due Sicilie (Napoli 1792) inserì i porti di Gallipoli e di Otranto. Il grande artista divenne pittore di corte del re Ferdinando IV di Napoli e in questa veste fu in Italia con molti incarichi come quello di supervisionare il trasferimento della collezione Farnese da Roma a Napoli. Fu amico di Goethe che scrisse di lui nella sua opera “Viaggio in Italia”. Ma l’incarico più prestigioso che il pittore ricevette dal re Ferdinando IV fu la commissione del famoso ciclo di dipinti raffiguranti i porti del Regno di Napoli.

Le numerose vedute dei porti si articolano in tre gruppi suddivisi tra le vedute campane, pugliesi, calabresi e siciliane. Per eseguire i disegni preparatori si recò così in Puglia e in Campania. La serie comprende 17 quadri e si trova ancora oggi custodita alla Reggia di Caserta; vi sono raffigurati esattamente i porti di Taranto, Brindisi, Manfredonia, Barletta, Trani, Bisceglie, Monopoli, Gallipoli, Otranto.

La serie è stata in mostra, dal 20 giugno al 5 novembre 2017, presso la Sala Ennagonale del Castello di Gallipoli (Lecce). L’esposizione intitolata “I porti del Re”, a cura di Luigi Orione Amato e Raffaela Zizzari, prodotta dal Castello in collaborazione con la Reggia di Caserta e il Comune di Gallipoli, ha visto all’inaugurazione l’intervento dello storico dell’arte Philippe Daverio e del direttore generale della Reggia di Caserta, Mauro Felicori (5). Nel giugno 2018, si è tenuta a Brindisi la grande mostra: “Brindisi: Porto d’Oriente”, a Palazzo Nervegna, dove è stato possibile “ammirare per la prima volta il celebre quadro ‘Baia e Porto di Brindisi’ che il vedutista prussiano Jakob Philipp Hackert realizzò nella seconda metà del ‘700 su incarico del re Ferdinando IV di Borbone. L’esposizione è stata organizzata nell’ambito del progetto ‘La Via Traiana’ e comprendeva una serie di opere che raccontano la storia della città attraverso alcune vedute del porto, fatte dai viaggiatori del ‘700” (6). Anche lo scrittore Johann Wilhelm von Archenholtz (1741-1813), famoso politologo, era stato in Italia ma egli, pur essendo tedesco, aveva pubblicato un’opera intitolata England und Italien, nel 1785, nella quale contrapponeva i due paesi, appunto il Regno Unito e l’Italia, con due sistemi politici diversi, propendendo decisamente per l’Inghilterra. Tuttavia nelle critiche feroci che Wilhelm fa a Genova, Venezia, allo Stato della Chiesa e al Regno di Napoli, è facile scorgere una larvata accusa alla sua Germania (7). Il poeta Friedrich Leopold Stolberg (1750-1819) nella sua opera Reise in Deutschland, der Schweiz, Italien und Sicilien in den Jahren 1791 und 1792, 4 voll., 1794, documenta il suo viaggio nel sud Italia dove però manifesta una posizione anticlassica e irrazionalistica, che provocò la sdegnata reazione di Goethe.

L’opera è stata recentemente tradotta in italiano da Laura A. Colaci, che scrive: “Dopo il viaggio nel Sud della Germania e della Svizzera col fratello e con Goethe, Stolberg ne intraprese uno più lungo in compagnia della moglie Sophie von Redern, del figlioletto, di G.A. Jacobi e G.H.L. Nicolovius attraverso la Germania, la Svizzera e l’Italia.

Frutto di questo viaggio è il volume Reise in Deutschland, der Schweiz, Italien und Sicilien in den Jahren 1791 und 1792. Viaggiò in Puglia dal 3 al 17 maggio del 1792”(9). Si tratta di un’opera epistolare, composta cioè delle lettere che egli aveva inviato durante il suo soggiorno nel nostro Paese a vari corrispondenti tedeschi. Queste lettere però vennero rielaborate per la loro pubblicazione e ciò portò ad una certa stilizzazione, soprattutto in quelle che hanno un maggiore contenuto politico religioso. Egli visitò Brindisi, Lecce, Otranto, Gallipoli.

Il compagno di viaggio di Stolberg, Georg Arnold Jacobi (1768-1845), al ritorno dal suo viaggio pubblica Briefe aus der Schweiz und Italien nel 1796-7, ossia una raccolta delle sue lettere inviate da Brindisi, Lecce e Gallipoli. Sempre di un’opera epistolare dunque si tratta, ma le lettere dello Jacobi sembrano essere più in presa diretta, ovverosia meno stilizzate, di quelle del suo compagno di viaggio Stolberg, e soprattutto si nota in lui una minore componete polemica, pur essendo protestante e classicista anch’egli. È molto più critico però nei confronti del governo di Napoli e del malcostume che in quella città allignava. Mentre la prosa dello Stolberg è più accattivante, controllata e in qualche modo romantica, avendo egli rimaneggiato le lettere, quella dello Jacobi è invece più scarna e realistica. Entrambi i viaggiatori comunque sono attratti dai resti dell’antichità classica, per cui, specie quando giungono in Puglia, a partire da Taranto, la loro attenzione si sofferma sulle influenze greche della nostra civiltà. Stolberg sente tutta la civiltà europea tributaria della cultura classica. Il suo classicismo però è filtrato dal cristianesimo. Questo lo porta a vedere l’Italia, e in particolare il Sud, in quanto più diretta emanazione di quella cultura, come una sorta di paradiso perduto che, con antesignano gusto romantico, egli idealizza, dandone una visione edenica, certo lontana dalla realtà. “Pur vivendo nel clima del classicismo winckelmaniano, lo Stolberg è distante dall’dea di classico alla Winckelmann”, scrive Scamardi (10). Dunque egli ripudia ogni idea dell’arte che non sia classica, per esempio il barocco leccese. “l ruderi classici evocano, sì, l’idea della caducità della vita umana, un elemento, questo, certo presente in tanta poesia sulle rovine della fine del Settecento, solo che lo Stolberg oppone la certezza della fede cristiana[…] In questo lo Stolberg anticipa non solo taluni stilemi di un certo romanticismo, ma anche un certo kitsh romantico. Si può concordare, in definitiva, col giudizio di Helga Schutte Watt secondo la quale lo Stolberg in Italia ritorna ai fondamenti classici della cultura europea e della sua stessa formazione intellettuale e non solo non scorge alcun conflitto tra classicismo e cristianesimo, ma vede in quest’ultimo una forma di coronamento, di inveramento del primo” (11).

A Taranto sono ricevuti dal Vescovo Giuseppe Capecelatro, uomo di vastissima cultura, lo stesso che accompagnò il viaggiatore svizzero Carlo Ulisse De Salis Marschlins (1728-1800 ) nel suo viaggio in Puglia. Come già Eberhard August Zimmermann (1743-1815), naturalista e geografo, che venne in Puglia su incarico del Regno di Napoli per studiare la nitriera naturale di Molfetta (12), anche il conte svizzero era accompagnato dall’Abate Fortis e i suoi interessi principali erano volti all’agricoltura e all’allevamento. Abbiamo già detto del De Salis Marschlins, che pubblica per la prima volta le sue impressioni di viaggio in tedesco in due volumi a Zurigo nel 1790 e nel 1793. La prima pubblicazione del libro in lingua italiana viene fatta nel 1906 (13), con la traduzione di Ida Capriati De Nicolò (ottima traduttrice anche delle memorie di Janet Ross)(14), e poi viene più volte ripubblicato (15).

Lo storico Ferdinand Gregorovius (1821-1891) visse più di vent’anni in Italia, soprattutto a Roma. Pubblicò i suoi resoconti di viaggio in Italia nell’opera Wanderjahre in Italien tra il 1856 e il 1877, in cui fa una descrizione analitica, davvero minuziosa delle condizioni di vita del nostro popolo in quegli anni. Il suo è un interesse erudito, per cui alle note naturalistiche, si accompagnano le descrizioni artistiche e letterarie e soprattutto sociologiche. L’opera si compone di cinque volumi ed è nell’ultimo volume, con il titolo Apulische Landschaften, (Lipsia, F. A. Brockhaus, 1877) che si occupa del nostro territorio. Gregorovius venne in Puglia due volte, nel 1874 e 1875. La prima traduzione della sua opera è di Raffaele Mariano nel 1882 (16). L’itinerario si snoda attraverso le città di Lucera , Manfredonia, Monte Sant’Angelo, Andria, Castel del Monte, Lecce e Taranto.

“Il Gregorovius seguiva con interesse la ricezione della cultura tedesca in Italia e intratteneva rapporti cordiali con chiunque in qualche modo se ne occupasse. Ma è soprattutto la scuola filosofica hegeliana che attrae l’attenzione dello storico tedesco che, come è noto, aveva egli stesso studiato filosofia all’Università di Konigsberg. Fu proprio attraverso il Rosenkranz, suo maestro a Konisberg, che conobbe lo storico del cristianesimo e filosofo Raffaele Mariano, con cui oltre a compiere i viaggi in Puglia intrattenne sempre rapporti di amicizia. Il Mariano tradusse in italiano le Apulische Landschaften. Nell’introduzione alla sua traduzione, nella quale il Mariano ricostruiva, attingendo alla pubblicistica meridionalistica di Pasquale Villari e Raffaele De Cesare, la situazione politico-sociale della Puglia, l’autore non nascondeva una certa animosità nei confronti dei pugliesi, che suscitò le forti proteste di Niccolò Brunetti…”. Così scrive Scamardi (17), che pubblica nel suo libro anche i Diari inediti di Gregorovius del secondo viaggio in Puglia (1875)(18). Si rimproverava cioè al traduttore e quindi all’autore un punto di vista troppo “tedescocentrico”.

In realtà, Gregorovius dimostra grande interesse nei confronti dell’Italia meridionale, dei suoi punti di forza ma anche delle sue mancanze. Si appassiona della questione meridionale, si rammarica dell’arretratezza delle infrastrutture, si intrattiene sulla rete viaria e quella ferroviaria, sul porto di Brindisi, parla della mafia e della lotta dello stato contro la criminalità, ecc. Da storico non può non essere attratto dal fascino della storia millenaria, soprattutto a Roma, sua città elettiva. “In una pagina delle Wanderjahre in Italien fa una digressione sui paesaggi storici italiani dove si avverte, più che altrove, il respiro del passato. Dai monumenti emana come una forza elettrica per la quale il Gregorovius conia l’espressione ‘magnetismo della storia’”(19). A lui si deve la definizione di Lecce come “Firenze del Sud”. Gregorovius non amava il romanico e prediligeva il gotico. Il tedesco Gustavo Meyer Graz (1850-1900), corrispondente del Sclesische Zeitung di Breslavia arriva nel 1890 per raccogliere i canti della Grecia Salentina. I suoi articoli di viaggio vennero poi tradotti da Cosimo De Giorgi (che lo accompagnò nel viaggio) nel 1895 per “Il Popolo Meridionale”, rivista leccese, e poi successivamente in volume (20). Gli articoli si intitolano: “Da Brindisi a Lecce”; “Lecce-San Nicola e Cataldo”; “Da Lecce a Calimera”; “Taranto”. Il Meyer è molto preoccupato dal fatto che la lingua greganica vada persa a causa dell’incuranza dei governi.

Taranto nel 1789, Incis. da Hackert

Venne in Italia anche lo storico dell’arte Paul Schubring (1869-1935) corrispondente del giornale “Frankfurter Zeitung”, il quale mandava i suoi reportage di viaggio descrivendo minuziosamente la nostra regione. I suoi articoli vennero poi raccolti in volume da Giuseppe Petraglione (21). Secondo il traduttore, gli articoli di Schubring potrebbero essere considerati un ampliamento del libro del Gregorovius in quanto vi sono menzionati alcuni monumenti lì assenti, come la Chiesa di Santo Stefano in Soleto, e approfonditi altri di cui era stato fatto solo un fugace cenno, come la chiesa di Santa Caterina e la Cattedrale di Troia.

Note

[1]Raffaele Semeraro, Viaggiatori in Puglia dall’antichità alla fine dell’Ottocento: rassegna bibliografica ragionata, Schena, 1991, p.73.

[2] Johann Heinrich Bartels, Lettere sulla Calabria Viaggio in Calabria Vol III, Catanzaro, Rubettino, 2007.

[3] Johann Hermann von Riedesel ,Un viaggiatore tedesco in Puglia nella seconda metà del sec. XVIII. Lettere di J.H.Riedesel a J.J.Winckelmann, Prefazione e note di Luigi Correra, Martina Franca, Editrice Apulia, 1913, poi ristampata in Tommaso Pedio, Nella Puglia del 700 (Lettera a J.J. Winckelmann), Cavallino, Capone, 1979.

[4] Teodoro Scamardi, La Puglia nella letteratura di viaggio tedesca. Riedesel Stolberg Greborovius, Lecce, Milella, 1987, pp.35-58.

[5] http: www.famedisud.it/il-sud-settecentesco-di-philipp-hackert-in-mostra-a-gallipoli-i-porti-…

[6] http:www.brundarte.it/2018/03/23/baia-porto-brindisi-jakob-philipp-hackert/

[7] Teodoro Scamardi, op. cit., p.64.

[8] Friedrich Leopold Graf Zu Stolberg, Reise In Deutschland, Der Schweiz, Italien Und Sizilien In Den Jahren 1791 Und 1792 1794 Con traduzione italiana a cura di Laura A. Colaci, Edizioni Digitali Del Cisva, 2010.

[9] Carlo Stasi, Dizionario Enciclopedico dei Salentini, 2 voll, Lecce, Grifo, 2018, p.1128.

[10] Teodoro Sacamardi, op. cit., p.76 .

[11] Idem, p.77.

[12] Idem, p.24.

[13] Carlo Ulisse De Salis Marschlins, Nel Regno di Napoli : viaggi attraverso varie province nel 1789, Trani, Vecchi, 1906.

[14] Janet Ross, La terra di Manfredi, traduzione dall’inglese di Ida De Nicolo Capriati, illustrazioni di Carlo Orsi, Trani, Vecchi, 1899, poi ripubblicato in Eadem, La Puglia nell’Ottocento : la terra di Manfredi, a cura di Maria Teresa Ciccarese, Lecce, Capone, 1997.

[15] Fra gli altri, in Carlo Ulisse De Salis Marschlins, Viaggio nel Regno di Napoli, Galatina, Congedo, 1979, con Introduzione di Tommaso Pedio, e in Idem, Viaggio nel Regno di Napoli – che riproduce la prima traduzione italiana di Ida Capriati De Nicolò -, a cura di Giacinto Donno, Lecce, Capone, 1979 e 1999, e ancora in Idem, Nel Regno di Napoli Viaggi attraverso varie provincie nel 1789, Avezzano, Edizioni Kirke, 2017.

[16] Ferdinand Gregorovius, Nelle Puglie (1877), versione dal tedesco di Raffaele Mariano con noterelle di viaggio del traduttore, Firenze, G. Barbera, 1882.

[17] Teodoro Scamardi, op.cit., p.97.

[18] Idem, pp.137-147.

[19] Idem, p.127.

[20] Gustavo Meyer-Graz, Apulische Reisetage, a cura di Cosimo De Giorgi, Martina Franca, 1915. Poi ristampato in Idem, Puglia . Sud (1890), a cura di Gianni Custodero, traduzione di Cosimo De Giorgi, Cavallino, Capone Editore, 1980.

[21] Paul Schubring ,La Puglia: impressioni di viaggio (1900), traduzione e introduzione di Giuseppe Petraglione, Trani, Vecchi, 1901.

#August Zimmermann#Barone von Riedesel#Carlo Ulisse De Salis Marschlins#Ferdinand Gregorovius#Friedrich Leopold Stolberg#Georg Arnold Jacobi#Gustavo Meyer Graz#Jacob Philipp Hackert#Johann Heinrich Bartels#Johann Wilhelm von Archenholtz#Paolo Vincenti#Paul Schede detto Melissus#Paul Schubring#porti pugliesi#Viaggiatori in Puglia#Libri Di Puglia#Spigolature Salentine

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Alexander took the greatest pleasure in making the arrangements for setting up his daughter’s establishment. Her happiness—or, what to him was the same thing, her greatness meant much to him. He loved her passionately, superlatively." — Lucretia Borgia according to original documents and correspondence of her day (Ferdinand Gregorovius)

#that's his one and only babygirl </3#though in the show as much as he wanted her to be happy he ultimately ignores her (and his sons') aspirations and tragedies ensued#lucrezia borgia#the borgias#perioddramaedit#tvarchive#cinemapix#tvedit#weloveperioddrama#perioddramasource#ladiesofcinema#femalegifsource#dailyflicks#tusertha#tuserava#tusereliza#holliday grainger#theborgiasedit#tvgifs#by jen

517 notes

·

View notes

Text

Môj hrad. Pri niom bývam.

#Hrad#Hrad Nidzica#Nidzica#Mazury#Nidzica nem Niedzica#Niedzbark#Neidenburg#Prusy#Krzyżacy#Teutonic castle#Gregorovius#Ferdinand Gregorovius#Polsko#Lengyelország

1 note

·

View note

Note

I know you love Cesare, but I feel like I've seen you mention Sabatini is way too of a Cesare stan. Bc on the one hand I get that he likely glosses over a lot of what Cesare does, but on the other hand I can't really bring myself to blame cesare for killing who he does in a certain context. On some level, in the case of those disloyal, how else could you safelty handle it? Granted the manner is grotesque but I found Cesare leads more a psychological terror campaign than a killing one.

Sabatini’s problem is pretty much of the same order as Gregorovius’, though (much) less severe. All Borgia historians are dealing with a deeply unreliable record, and they all have to decide what they’re going to accept, what they’re going to refute, what isn’t worth their time, which things they’re going to emphasize and which dismiss.

Gregorovius’ approach is to dismiss everything that paints Lucrezia in a bad light, and take everything about Cesare (and to a slightly lesser extent, Rodrigo) as negatively as possible, which given the state of things is very negatively indeed. So he ends up arguing that, for instance, Lucrezia’s apparent complicity comes from being 1) weak-willed and 2) super nice, not actually being onboard with her family’s crimes (painted as particularly bad by him) or emotionally close to such awful people.

Sabatini’s version of events (like Meyer’s after him) is inherently pro-Borgia: he gives them–particularly Cesare–the benefit of all possible doubt. Now, I don’t think he’s dishonest the way that Gregorovius (and many others) can be. He’s not actively misrepresenting things. But it’s the Jane Bennet approach to history: taking things as favourably as they can be taken. That is a bias, a significant one.

Keep reading

#sin has a name and it is borgia#the borgias#cesare borgia#the prince#magnificent bastards of the vatican#rafael sabatini#ferdinand gregorovius#g. j. meyer#the life of cesare borgia#the borgias: the hidden history#such great ferocity and so much virtù

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Isola d'Elba ~ Ferdinand Gregorovius

Isola d'Elba ~ Ferdinand Gregorovius

Non si ha quella sterile confusione di Livorno, dove fra barcaioli e facchini non si è nemmeno sicuri della proprio vita. Qui, al contrario, tutto è tranquillo, quieto, felice. Oltrepassata la Porta si entra in una strada dove si svolge il mercato dei pesci e dei legumi, e da qui si arriva ad una piazza lunga e stretta, la Piazza d’armi, all’estremità della quale sorge la chiesa principale…

View On WordPress

#Corsica#Cosimo dei Medici#Ferdinand Gregorovius#ferro#Isola d&039;Elba#Italo Bolano#Longone#Marciana#Napoleone Bonaparte#Palmarola#Pianosa#Pietro Cirnèo#Piombino#Porsenna#Portoferraio#Rio Marina

0 notes

Photo

Lucrezia established her ducal court in accordance with the dictates of her own fancy. She was now the soul and center of the intellectual life in Ferrara. Her cultivated intellect, her beauty, and the irresistible joyousness of her being charmed all who came into her presence.

Ferdinand Gregorovius: Lucrezia Borgia: Daughter of Pope Alexander VI

Copernicus received the doctorate in canon law from the University of Ferrara on 31st May 1502. […] He had received permission to study abroad. To show that he had not frittered his time away on wine, women, and songs, he had to bring a diploma. That cost much less in Ferrara than in the other Italian universities.

Edward Rosen: Copernicus and His Successors

#italian history#renaissance#borgiaedit#lucrezia borgia#nicolaus copernicus#early modern#16th century#pietro bembo#isolda dychauk#marco cassini#the last gif tho#so adorable#he was just there for one scene and still stole my heart#he and his apple#historyrelated#fact based history

105 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Rosanna Franceschetti-Serpentini and other Corsican heroines

In 1729, the island of Corsica was under the rule of the republic of Genoa, Italy. The local people rose against their overlords, which led to a conflict that lasted forty years before being fully resolved.

Many women distinguished themselves during this struggle. One of them was the daughter of the rebel leader Fabio Vinciguerra. Described as being of a warlike disposition, she swore revenge when her father was assassinated by the governor. Taking the head of his troops, she was known for the brutality with which she fought the Genoese soldiers. In 1739, the wife of Bartolo of Barbaggio acquired similar fame for her courage in battle.

In 1746, Faustina Gaffory, defended her home in Corte from the Genoese with a handful of companions. Seeing their energies falter, she showed her comrades a powder barrel and threatened to blow-up the house. The defenders thus kept fighting.

In 1761, the women of Tenco defended their town. One of them, Josephine Jacobi armed herself and joined the fray. Other women imitated her and fought. Animated by their example, the defenders repelled the besiegers.

Several women fought at the battle of Borgo in 1769 on the side of the Corsican patriot and military leader Pasquale Paoli. Magistrate and memorialist Salvatore Viale described them as armed with rifle and knife, sharing the perils of war with their husbands.

Among them was Rosanna Franschetti-Serpentini who fought alongside her husband, an officer. She was dressed in male attire and “always well armed”. She was nicknamed “the heroine” or “our captain”. Rosanna notably defeated a French officer in hand-to-hand combat (since French troops had landed in Corsica after Genoa sold the island to France). When she saw that her side had to retreat, she freed her captive and said: “Remember that a Corsican woman overcame you and gave you back your sword and freedom”.

Bibliography:

Aimé André, Histoire générale de la Corse depuis les premiers temps jusqu'a nos jours, vol.2

Albertini Jean-André, Orsatelli Andrée, Corté et la renaissance de l'université corse

Bessières Luc, Panthéon des martyrs de la liberté, ou histoire des révolutions politiques, et des personnages qui se sont dévoués pour le bien et la liberté des nations, etc.

Ettori Fernand, Mémorial des corses

Fillipi Antoine-Baptiste, La corse, terre de droit: Essai sur le libéralisme latin et la révolution philosophique corse (1729-1804)

Gio Pietro Vieusseux, Archivio storico italiano: ossia raccolta di opere e documenti finora inediti o divenuti rarissimi riguardanti la storia d'Italia, vol.14

Gregorovius Ferdinand, Corsica in Its Picturesque, Social, and Historical Aspects: The Record of a Tour in the Summer of 1852

Pomponi Francis, Émeutes populaires en Corse : aux origines de l'insurrection contre la domination génoise (Décembre 1729 - Juillet 1731)

Renucci Francesco Ottaviano, Quattro storiche novelle

Malaspina Toussaint M., “La Corse”, Revue politique et littéraire: revue bleue

#history#women in history#Faustina Gaffory#Josephine Jacobi#Rosanna Franschetti-Serpentini#corsica#Corsican history#18th century#warrior women#france#french history

80 notes

·

View notes

Photo

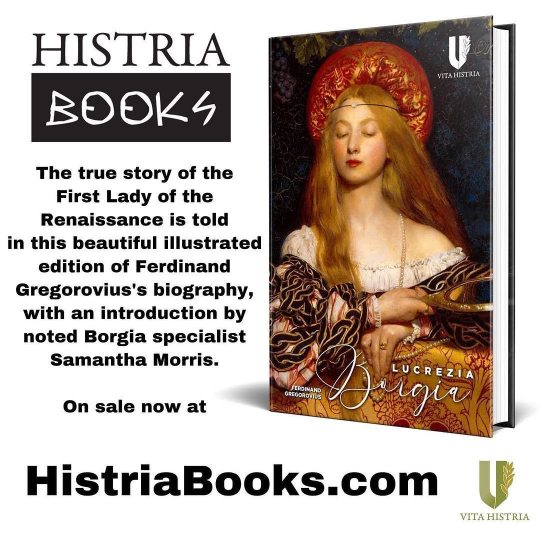

The story of Lucrezia Borgia, one of the most fascinating and controversial personalities of the Renaissance. The daughter of Pope Alexander VI, she was intensely involved in the political life of Italy during the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries. While her marriage alliances helped advance the political objectives of the papacy, she also held the office of Governor of Spoleto, a role normally reserved for Cardinals, making her one of the most powerful and dynamic female figures of the Renaissance. This new edition of Ferdinand Gregorovius’s classic work on Lucrezia Borgia is lavishly illustrated in color and black and white and enhanced with an introduction by Samantha Morris, a noted expert on the history of the Borgias. Available now at HistriaBooks.com #histriabooks #borgia #lucreziaborgia #renaissance #renaissanceitaly #historybooks https://www.instagram.com/p/CU4GE0xMf_3/?utm_medium=tumblr

3 notes

·

View notes