#Emishi

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

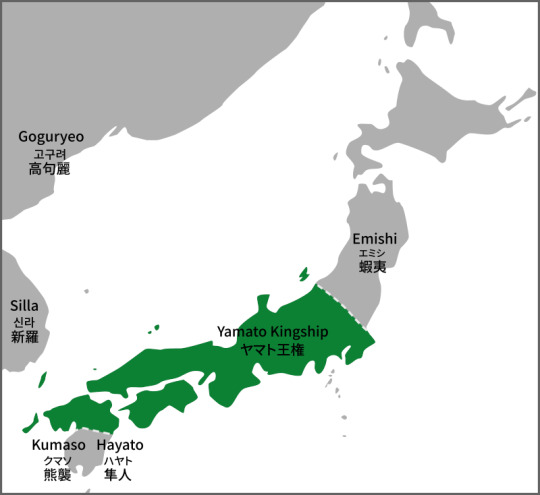

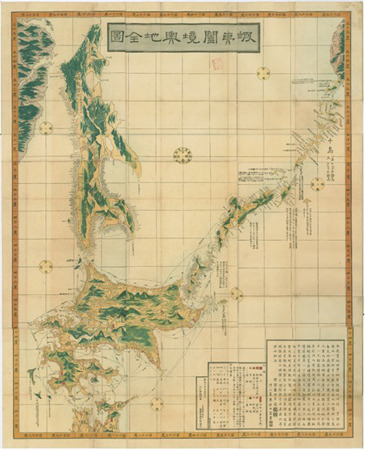

Capítulo 1: Introducción a los Emishi. Sean bienvenidos amantes del mundo japonés a una nueva publicación, en esta ocasión vamos a hablar sobre los emishi dicho esto pónganse cómodos que empezamos. - Para empezar, el término emishi hace referencia a todas las tribus y pueblos que vivían y que todavía viven al norte de Japón es decir la mitad norte de Tohoku, incluida hokkaido a este pueblo se le denominaba y se le denomina todavía a día de hoy Ainu, considerados los primeros pobladores del archipiélago a lo largo del siglo XVI hubo una serie de campañas militares para controlar dicho territorio aunque ya en el siglo VII siglo VIII después de Cristo durante el apogeo del clan yamato crearon una serie de fortalezas al norte para mantenerlos a raya. De hecho eran denominados bárbaros del norte que además se revelarán en más de una ocasión bajo el dominio japonés sin resultado alguno, actualmente se les da un reconocimiento a esta cultura, que en el pasado no lo tuvieron, como por ejemplo hay un museo dedicado a ellos y a su cultura. - Espero que os haya gustado y nos vemos en próximas publicaciones que pasen una buena semana. - 第 1 章: 蝦夷の紹介。 日本世界を愛する皆さん、新しい出版物にようこそ。今回は蝦夷について話します。とはいえ、気を楽にして始めましょう。 - まず、蝦夷という用語は、日本の北、つまり北海道を含む東北の北半分に住んでいた、そして今も住んでいるすべての部族と民族を指し、この民族は現在もアイヌと呼ばれていると考えられています。 16 世紀を通じてこの列島に最初に定住した人々は、その領土を支配するために一連の軍事作戦を行ったが、すでに 7 世紀から 8 世紀にはヤマト氏の全盛期に、彼らは北に一連の要塞を築き、領土を維持していた。湾。実際、彼らは北の野蛮人と呼ばれていましたが、日本の統治下でも何の成果も得られずに何度も姿を現しましたが、現在では、この文化は、例えば、そこでは過去にはなかった認識を与えられています。は彼らとその文化に特化した博物館です。 - 気に入っていただければ幸いです。今後の投稿でお会いしましょう。良い一週間をお過ごしください。 - Chapter 1: Introduction to the Emishi. Welcome lovers of the Japanese world to a new publication, this time we are going to talk about the emishi, that being said, make yourself comfortable and let's get started. - To begin with, the term Emishi refers to all the tribes and peoples who lived and still live in the north of Japan, that is, the northern half of Tohoku, including Hokkaido. This people was called and is still called Ainu today. , considered the first settlers of the archipelago throughout the 16th century there were a series of military campaigns to control said territory although already in the 7th century 8th century AD during the heyday of the Yamato clan they created a series of fortresses to the north to keep them at bay. stripe. In fact, they were called barbarians of the north who also revealed themselves on more than one occasion under Japanese rule without any result. Currently, this culture is given recognition, which in the past they did not have, such as, for example, there is a museum dedicated to them and their culture. - I hope you liked it and see you in future posts, have a good week.

#japan#culture#history#archaeology#photography#Ainu#Hokkaido#Emishi#heianperiod#NaraPeriod#unesco#anime#日本#文化#歴史#考古学#写真#アイヌ#北海道#蝦夷#平安時代#奈良時代#ユネスコ#アニメ#maps#地図#地理#geography#Tohoku#東北

59 notes

·

View notes

Text

Explaining Solarpunk With The Help Of Princess Mononoke

Recently I was asked to write an essay about Solarpunk - and especially the "punk" of Solarpunk and how it is used to tell stories - for a German publication that will be released later this year. Originally someone else had been asked to write an essay, but the publishers were not happy with that essay, becuase that essay very much focused just on the history, and worse, on the history in "the west". So, I did what I already do in this blog over and over: Ramble about Solarpunk. Though for that essay I tried to get it a bit scientific sounding. ;)

I did talk about the history of the genre, too, and about how the punk genre came to be. But with Solarpunk I especially talked about the influence of Hayao Miyazaki and Ursula K. LeGuin. And while discussing how those stories influenced Solarpunk as a genre, I realized one thing: The most Solarpunk Ghibli movie is Princess Mononoke. In fact, that movie is so Solarpunk, that I think it can be used to explain the genre more than anything. And that is despite the fact that this movie is not science fiction, but set in the Japan of the 14th century.

Because, well... I will repeat: No, Solarpunk does not necessarily need to be a SciFi setting. You can write a story that is fundamentally Solarpunk in almost any setting.

Now, let me talk a moment about Princess Mononoke, for everyone who has not watched the movie (at least in a while):

Princess Mononoke is the story of Ashitaka, the prince of the Emishi (one of the technically erased indigenous cultures of Japan). After his village gets attacked by a corrupted god, he travels west to find one of the last mountain gods in the hope that this god can heal him. Before he finds the god, however, he gets drawn into the conflict between a settleman calling itself Irontown and the minor gods of nature living around it. The gods try to bring down Irontown, which is lead by Lady Eboshi, as the iron extraction is destroying nature and with it the gods themselves, too. On the side of the gods, there is also San, a girl who had been abandoned in the forest by her parents and was taken in by the wolf gods. Ashitaka finds, that he will have to help both sides to find a peaceful solution.

Now, the movie is very interesting from so many Solarpunk aspects.

The central conflict is very much a conflict between men and nature, but one where both sides are shown with a lot of nuance. As well as having some aspects that a lot of people tend to overlook - like the importance of Ashitaka's perspective as an indigenous man.

Now, the movie could have been quite simple, but Miyazaki chose to not make it that way. Because the quite interesting point is, that Irontown is filled with people from the Untouchable Caste of Japanese society. (Because yes, Japan has a Caste system - untouchables exist to this day.) Untouchables were prostitutes, people who worked certain other jobs like mortician, sick people and such. And Eboshi is a former prostitute, who knew of this and decided to fill her town with only other untouchables, often rescuing them from abject poverty. And she does care about them. She wants to help those people. She just does not see the value in the nature she is destroying compared to the value she can create for herself and her people by selling weapons.

The mythology shown in the movie, rather than depicting classic Shinto mythology, actually is build more around what we know about pre-Shinto Japanese mythology, which has a lot more animalistic gods than what it evolved to with Shinto.

And again, the very interesting aspect that a lot of people ignore is that Ashitaka is indigenous. He is not Japanese, he is Emishi - he is from a culture that the Japanese culture (that came from Chinese and Korean colonialism of the Japanese islands) eradicated. But within the world of the movie some Emishi have survived and have hidden in the mountains.

Which brings me to the point that actually makes me say, that this is the most Solarpunk movie: The ending. Because the ending of the movie is, that both sides decide that they will need to find a way for both of them to live. And they will learn that with Ashitaka staying with the people of Irontown and helping them live together with nature.

Because the movie quite clearly says: Yes, the methods that Eboshi choses are wrong. But her goals - helping those people outcast by normal society - are still good ones. And there has to be a way that these people can live a good life at this place surrounded by this ancient nature without being antagonistic towards it.

Now, of course the movie leaves in a very open end. It does not say whether they manage and how they manage. But they at least try.

And I think that is what makes this movie so inherently Solarpunk: The mixture of those themes. The indigenous culture. The nature and its protection. And the survival of those outcasts. That is a lot of themes - and it is the themes that I think are at the very core of what Solarpunk should be.

Again... I keep harping on this in this blog, but I will say it again: No, Solarpunk is not an aesthetic. It is about themes and content. Which is exactly why so many of the stories people will tell you about when you ask them about it, are not very SciFi in fact - and not at all fitting with the tumblr aesthetic. They are a lot more like Princess Mononoke and Nausicaä. And... Well, I think that this is something people really should take more to heart. Allow for it to be more thematic - rather than necessarily fitting with the aesthetic.

#solarpunk#lunarpunk#princess mononoke#studio ghibli#ghibli#ghibli films#fantasy#indigenous#emishi#japanese culture#environmentalism

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

resisting the urge every time ive ever seen an analysis of the ecological and/or ethical themes in princess mononoke to grab the person by the face and scream that their analysis is valuable but is inherently incomplete without the understanding that this is also a movie about real historical colonialism

#my posts#please just. even read the wikipedia pages about the emishi and the ainu. do anything#the japanese government did not actually legally recognize the existence of the ainu indigenous people they colonized until 2019.#look up the history of northern honshu and hokkaido and sakhalin.#ask why the government did for centuries & STILL culls the bears that are so sacred to the ainu. ask what happened to the wolves.#the ethnocide and ecocide are inherently tied here and they are real

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ghibli girls wearing Bulgarian folk dresses.

Source

#studio ghibli#ghibli girls#ghibli#anime#miyazaki hayao#hayao mizayaki#princess mononoke#kiki's delivery service#bulgaria#bulgarian girls#bulgarian folklore#魔女の宅急便#ジブリ#ブルガリア#illustration#artists on tumblr#my art#もののけ姫#emishi girls

593 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ainu Divine Songs Collection (Ainu Shin’yoshu) by Chiri Yukie / «Собрание божественных песен Айну(Айну синъёсю) Тири Юкиэ

Автор: Тюрленева Екатерина Георгиевна, магистр Института Восточных Культур и Античности РГГУ/ Author: Tyurleneva Ekaterina G., master of the Institute for Oriental and Classical Studies of RSUH

“Ainu Shin’yoshu” is the compilation of 13 songs belonging to the genre kamui yukar, which means “songs of the gods”. In particular, it contains 11 songs about gods of nature and 2 songs, belonging to the genre oina, about human-god named Okikirmui. Kamui is a variety of Ainu’s gods. Nevertheless, kamui is not only a cult of nature. They are spirits whose existence in heavens does not differ from men’s life on earth. However, when they descend to the men’s world, they take the shape of animals, plants or other natural phenomena. The songs in “Ainu Shin’yoshu” are set out on behalf of the gods.

_

Сборник «Айну синъёсю» - это собрание 13 песен жанра камуи юкар, что в переводе означает «песни богов». Он содержит 11 песен о природных богах и 2 песни от лица бога-человека Окикирмуи, то есть в жанре ойна. Камуи - это всё множество айнских богов. Айн�� обожествляли те проявле- ния природы, которые были им непонятны ил�� опасны для них. Однако камуи - это не просто обожествление природы, это души, существование которых на небесах не отличается от жизни людей на Земле, но спускаясь в мир людей, они принимают облик животных, растений и других природных явлений. Песни «Айну синъёсю» изложены от имени богов, являющихся представителями живой природы, и содержат в себе фрагменты из их жизни.

_

I'm interested in Оkikirmui's song #11:

The song that little Okikirmui sang about himself "This sand is red, red"/ «Этот песок красен, красен».

Earlier I wrote about references to the Ainu's culture in the narrative, and this song again points us to a secret code that the authors may have hidden.

The last battle of Yato and his father is very similar to the events of the meeting of the Ainu's human-god - little Okikirmui with an evil deity dressed in black clothes.

I recommend that you read this song and compare the events of the manga 🙏

Unfortunately, at the moment I wasn't able to find an official translation of the song in Eng, so I will add it in Russian:

Однажды, когда я пошёл прогуляться вверх по течению реки,

❗️Я встретил дитя злого бога.

❗️Всегда дети злых богов красивы на внешность.

Одетый в чёрную одежду,❗️

С маленьким луком и маленькими стрелами из грецкого дерева в

руках,

Он посмотрел на меня, ухмыльнулся и сказал:

❗️«Давай поиграем, маленький Окикирмуи!❗️

***

Увидело это дитя злого бога,

И сильно разозлилось.

❗️«Какая наглость!

Раз ты в самом деле решился на такое, давай посоревнуемся в силе»,❗️ —

Произнося эти слова, он снял с себя верхнюю одежду. Я тоже остался только в одной тонкой рубашке

И набросился на противника.

❗️Он набросился на меня в ответ.

Мы продолжали борьбу с попеременным успехом. Удивился я, что так сильно дитя злого бога.❗️

Но наконец, напряг я спину и руки,

Забросил дитя злого бога себе на плечи

И швырнул его об горную скалу.

Раздался звук удара о скалу.

Убив его, ❗️я втоптал-сбросил его в подземный мир.❗️

После этого все звуки исчезли.

Тогда я пошёл обратно вниз по течению реки.

Поднявшись вверх по течению,

Лососи шумно и весело плескались в реке.

А в лесу, веселясь и смеясь, шумели самцы и самки оленей. Повсюду можно было видеть, как они спокойно что-то жевали. Увидев это, я успокоился

❗️И вернулся к себе домой.

Так рассказывал маленький Окикирмуи.

_

This is only a small part of the references, in fact there are many more of them. Previously, I devoted a lot of time to studying materials on Ainu's culture. It's amazing how the authors tried to pay attention to the complex and multifaceted culture of this people.

In the forward to Ainu Shin’yōshū, Chiri Yukie states:

“If these stories are read by the many people who kindly want to know about us, I, together with my ancestors, would be boundlessly and supremely happy.”

p.s. I don’t consider him an evil or heartless father, despite some scenes. Its history is complex and multifaceted. I studied very carefully the character, actions, visual details of this character - nothing is as it seems at first glance 🙏

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

@emishi-arase continued from here!

Darla had been cutting through back allies. She had just shaken off the police chasing her, and didn't want to be found again so soon. It was then she heard the sound of crying. She could have kept walking in the direction she was and ignored her completely but... that wouldn't sit right with her.

She follows the sound of crying and finds someone who looks to be a little younger than her. Her heart hurts at the sight. "Hey, are you alright?" She says softly as she approaches them. Making sure not to get too close to them yet and scare them off.

#emishi-arase#⚔; Her words are sharper than her blade ( the little sister )#⚔; Route undecided ( verse unknown )

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Twitter_Log_30 (2023/05/20:Twitter投稿)

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Ainu people are an indigenous ethnic group residing in the northern parts of the Japanese archipelago, including what is today known as Hokkaido and the Tōhoku region of Honshu. Their ancestors date back to the Paleolithic (35,000 – 13,500 BCE) and Jomon periods (13,500 – 400 BCE).

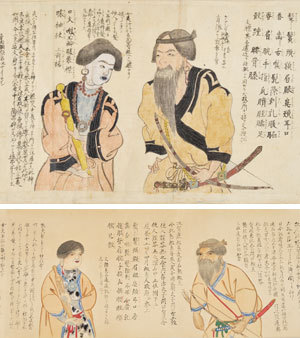

This accordion style album is a copy of Ishūretsuzō (夷酋列像), also known as A Series of Paintings of Ainu Chieftains. It is a series of twelve painted portraits of Ainu elders who helped suppress the Menashi–Kunashiri rebellion in 1789 by siding with the Wajin (ethnic Japanese people, also called Yamato people). The original portraits were completed in 1790 by the Japanese artist Kakizaki Hakyō (1764–1826) and was received by the imperial court in Kyoto in 1791. The album includes a portrait of an elderly woman named Chikiriashikai, the mother of the chieftain Ikotoi, also pictured in the album.

Tan Yi-Ern Samuel, Ph.D. student in the Department of History of Art and Architecture, is looking at this album for his paper in Professor Yukio Lippit’s seminar on East Asian Portraiture, taught with curator of Chinese painting at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Joseph Scheier-Dolberg. Today, we opened the album to look at it in its standing accordion style. The clothing worn and other accoutrements including animal fur depicted in the portraits show the connections between the Ainu, the Wajin, China, and Russia during that time.

The Ainu people are one of the few ethnic minorities native to the Japanese islands. They have been subjected to forced assimilation and colonization by the Japanese since at least the 18th century or earlier. Their ancestors, referred to as Emishi, were pushed to the northern islands by Wajin since the 9th century. The portraits of Ainu elders in this album reveal how they might have been fashioned in the imagination of the Wajin in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

夷酋列像圖.

Ishūretsuzō zu Title on book: 夷酋圖 : 夷酋十二人圖像 [Japan] : [publisher not identified], [between 1826 and 1830?] Japanese Dates on original paintings: 文政九年 [1826], 十一年[1828] and 十三年[1830] Dates on original paintings: Bunsei 9-nen [1826], 11-nen [1828] and 13-nen [1830]. HOLLIS number: 990147257380203941

#夷酋列像#Ishūretsuzō#Ainu#AinuPortraits#Painting#SpecialCollections#HarvardFineArtsLibrary#Fineartslibrary#Harvard#HarvardLibrary#アイヌ

118 notes

·

View notes

Note

Does the play in revival my dream is really racist/stereotypical ?

Yes, I don't think it was intentional at all in fact it's pretty clear the intention was to say "don't judge those who are different from you just because you don't understand them" but ultimately they failed at that.

The play presents it as a very "both sides" kind of issue in terms of the natives and colonisers not understanding each other. There's also this line:

Before this the town dwellers (colonisers) had been incredibly rude towards and fearful of the forest people (natives). The girl Emu is playing rescues a solider after her people attacked him, even though the soliders had literally just invaded their land "just to check" if the natives were gonna attack the town. "They're not all bad" to the officer who just led a march onto someone else's land just in case is not the right message here at all.

Also ultimately it's revealed that the conflict between the both sides was instigated by a third party. The worse coloniser who wants to exploit the natives for their natural resources. The townspeople are the good colonisers who should be forgiven for their actions because they were manipulated by the antagonist who is a bad coloniser is also not a good look. Like it really hammers in the "not all bad" message here by introducing the only character who you are meant to think of as bad. Not like the other townspeople were incredibly racist before they made amends with the natives. That can be forgiven because they don't really think like that they were just manipulated by the evil exploitative coloniser. Do you see how bad that message is.

(Also there's a line about how the townspeople might sell Emu to another country for interacting with them and maybe we're meant to view it as an exaggeration but either way. Why are we meant to be forgiving towards these people again?)

While the movie Emu and Nene's cards seem to take inspiration of is based on the Emishi people, it's more likely that the play is based on Ainu people, due to the more recent archetecture used in the sets, as well as the costumes for the officer and subordinate (refer to Tsukasa's rmd untrained). Emishi people are believed by historians to be ancestors (but ethnically distinct) to Ainu people. I strongly suggest looking into the history of Ainu people and the oppression they faced from the Japanese government and other countries (European ones surprise surprise), because the oppression dates back over a millenium and is far too much for me to reasonably cover in any detail. In brief, the government for centuries has regarded the Ainu people as a primitive and barbaric group (both terms are also used in the rmd play), and in recent centuries took their lands in northern Japan with the expectation that the Ainu would assimilate with the Yamato Japanese people. Post WW2 they were denied rights to their traditional practices and even their language due to governments pushing for monoculturalism.

That's not even going into the fact that the reason wxs is the only unit that has card sets based on other cultures (this and island panic) is because they're treated like costumes, which in itself is an incredibly dehumanising and racist way to think.

144 notes

·

View notes

Text

Winner of the Poll ⇒

This is the top 5 winners that I let you guys voted for, for which guys you would like to see in Ghibli males! And to no surprise Rin won....

Now as a matter of time here are the top 5 winners that I would make a story for them the male MC’s in the movie! And ofc the reader is portrayed as the female MC in the movie, you could be a goldfish,an cursed old lady, a witch or a wolf princess! But alas y'all picked the scared little girl as you (I judge you all for picking Rin. Especially you Mari, you know what you did)

Enough of that, here are the top winners!

RIN ITOSHI ⇒

#1st place winner with 26% votes

The story is about the adventures of a young ten-year-old girl named [Name] as she wanders into the world of the gods and spirits. She is forced to work at a bathhouse following her parents being turned into pigs by the evil witch. Luckily, the boy named Rin helps. After getting her to safety, he gives her detailed instructions on how to get a job in the spirit world, which he says is the only way to survive. He says his name is Rin and that he has known her since she was very small.

˗ˋˏ ♡ ˎˊ˗

"𝑰𝒇 𝒚𝒐𝒖 𝒄𝒐𝒎𝒑𝒍𝒆𝒕𝒆𝒍𝒚 𝒇𝒐𝒓𝒈𝒆𝒕 𝒊𝒕, 𝒚𝒐𝒖’𝒍𝒍 𝒏𝒆𝒗𝒆𝒓 𝒇𝒊𝒏𝒅 𝒚𝒐𝒖𝒓 𝒘𝒂𝒚 𝒉𝒐𝒎𝒆. 𝑰’𝒗𝒆 𝒕𝒓𝒊𝒆𝒅 𝒆𝒗𝒆𝒓𝒚𝒕𝒉𝒊𝒏𝒈 𝒕𝒐 𝒓𝒆𝒎𝒆𝒎𝒃𝒆𝒓 𝒎𝒊𝒏𝒆."

-ℝ𝕚𝕟 𝕒𝕤 ℍ𝕒𝕜𝕦

"𝑹𝒊𝒏 𝒘𝒐𝒖𝒍𝒅𝒏’𝒕 𝒔𝒕𝒆𝒂𝒍. 𝑯𝒆’𝒔 𝒂 𝒈𝒐𝒐𝒅 𝒑𝒆𝒓𝒔𝒐𝒏!"

-[ℕ𝕒𝕞𝕖] 𝕒𝕤 ℂ𝕙𝕚𝕙𝕠𝕪𝕠

MICHAEL KAISER ⇒

#2nd place winner with 25.2% votes

[Name], a young milliner, is cursed by a vengeful witch, transforming her into an elderly woman; to break the curse, she seeks out the enigmatic wizard Kaiser, who lives in a moving castle powered by a fire demon named isagi, and together they embark on a journey that involves war, self-discovery, and the true meaning of love, as [Name] learns to embrace her inner strength and challenges Kaiser to confront his own fears and insecurities, ultimately breaking the curse by accepting herself as she is.

˗ˋˏ ♡ ˎˊ˗

"𝑻𝒉𝒂𝒕'𝒔 𝒎𝒚 𝒈𝒊𝒓𝒍"

-𝕄𝕚𝕔𝕙𝕒𝕖𝕝 𝕒𝕤 ℍ𝕠𝕨𝕝

"𝑨 𝒉𝒆𝒂𝒓𝒕'𝒔 𝒂 𝒉𝒆𝒂𝒗𝒚 𝒃𝒖𝒓𝒅𝒆𝒏"

-[ℕ𝕒𝕞𝕖] 𝕒𝕤 𝕊𝕠𝕡𝕙𝕚𝕖

YOICHI ISAGI ⇒

#3rd place winner with 16.8% votes

Two orphans [Name] and Yoichi are pursued by government agent, the army, and a group of pirates. They seek [Name's] crystal necklace, the key to accessing Laputa, a legendary flying castle hosting advanced technology.

˗ˋˏ ♡ ˎˊ˗

"𝑻𝒉𝒆 𝒘𝒂𝒚 𝒚𝒐𝒖 𝒇𝒆𝒍𝒍 𝒇𝒓𝒐𝒎 𝒕𝒉𝒆 𝒔𝒌𝒚... 𝑰 𝒕𝒉𝒐𝒖𝒈𝒉𝒕 𝒕𝒉𝒂𝒕 𝒎𝒂𝒚𝒃𝒆 𝒚𝒐𝒖 𝒘𝒆𝒓𝒆 𝒂𝒏 𝒂𝒏𝒈𝒆𝒍 𝒐𝒓 𝒔𝒐𝒎𝒆𝒕𝒉𝒊𝒏𝒈."

-𝕐𝕠𝕚𝕔𝕙𝕚 𝕒𝕤 ℙ𝕒𝕫𝕦

"𝑰'𝒎 𝒓𝒆𝒂𝒍𝒍𝒚 𝒔𝒐𝒓𝒓𝒚. 𝑰𝒕'𝒔 𝒎𝒚 𝒇𝒂𝒖𝒍𝒕 𝒈𝒆𝒕𝒕𝒊𝒏𝒈 𝒚𝒐𝒖 𝒎𝒊𝒙𝒆𝒅 𝒖𝒑 𝒊𝒏 𝒂𝒍𝒍 𝒕𝒉𝒊𝒔."

-[ℕ𝕒𝕞𝕖] 𝕒𝕤 𝕊𝕙𝕖𝕖𝕥𝕒

MEGURU BACHIRA ⇒

#4th place winner with 10.7% votes

The son of a sailor, 5-year old Meguru lives a quiet life on an oceanside cliff with his mother Yuu. One fateful day, he finds a beautiful goldfish trapped in a bottle on the beach and upon rescuing her, names her [Name]. But she is no ordinary goldfish. The daughter of a masterful wizard and a sea goddess, [Name] uses her father’s magic to transform herself into a young girl and quickly falls in love with Meguru, but the use of such powerful sorcery causes a dangerous imbalance in the world.

˗ˋˏ ♡ ˎˊ˗

"𝑳𝒐𝒐𝒌 𝒂𝒕 𝒉𝒆𝒓. 𝑰𝒔𝒏'𝒕 𝒔𝒉𝒆 𝒑𝒓𝒆𝒕𝒕𝒚?"

-𝕄𝕖𝕘𝕦𝕣𝕦 𝕒𝕤 𝕊𝕠𝕤𝕦𝕜𝕖

"[𝑵𝒂𝒎𝒆] 𝑳𝒐𝒗𝒆𝒔 𝑴𝒆𝒈𝒖𝒓𝒖!"

-[ℕ𝕒𝕞𝕖] 𝕒𝕤 ℙ𝕠𝕟𝕪𝕠

HYOUMA CHIGIRI ⇒

#5th place winner with 9.3% votes

Hyouma, a young Emishi prince, is cursed by a demonic boar god while defending his village, forcing him to journey west to find a cure; there, he becomes entangled in a war between the forest spirits, led by a human girl raised by wolves named [Name], and the inhabitants of Irontown, a human settlement led by the ambitious Lord Chris, who is aggressively exploiting the forest for resources; Hyouma must navigate this conflict, trying to find a balance between the needs of humans and nature to break the curse on his arm and prevent further destruction.

˗ˋˏ ♡ ˎˊ˗

"𝒀𝒐𝒖'𝒓𝒆... 𝒃𝒆𝒂𝒖𝒕𝒊𝒇𝒖𝒍..."

-ℍ𝕪𝕠𝕦𝕞𝕒 𝕒𝕤 𝔸𝕤𝕙𝕚𝕥𝕒𝕜𝕒

"𝑨𝒏𝒅 𝑰'𝒎 𝒏𝒐𝒕 𝒂𝒇𝒓𝒂𝒊𝒅 𝒐𝒇 𝒚𝒐𝒖! 𝑰 𝒔𝒉𝒐𝒖𝒍𝒅 𝒌𝒊𝒍𝒍 𝒚𝒐𝒖 𝒇𝒐𝒓 𝒔𝒂𝒗𝒊𝒏𝒈 𝒉𝒊𝒎!"

-[ℕ𝕒𝕞𝕖] 𝕒𝕤 ℙ𝕣𝕚𝕟𝕔𝕖𝕤𝕤 𝕄𝕠𝕟𝕠𝕟𝕠𝕜𝕖

˗ˋˏ ♡ ˎˊ˗

#6th place is Kenyu Yukkimiya with 6.1%

#7th place is Reo Mikage with 3.8%

#8th place is both tied are Nijiro Nanase and Eita Otoya with 1.2%

The story will be posted at my Tumblr page where it would be public for everyone to see and read! I hope my attention span doesn't die on me and hopw to make all five of them at the end! Till then!

P.S: Please tell me or comment on any questions you guys might have for me and I'll gladly answer them for you

˗ˋˏ ♡ ˎˊ˗

Navigation

Master List

© 2024 Velveteen 平和な目覚め— do not repost, copy, translate, modify, etc my work on any platform without my permission!

#blue lock#bllk#blue lock characters#blue lock x reader#bllk x reader#bachira meguru#micheal kaiser#micheal kaiser x reader#rin itoshi x reader#yoichi isagi x reader#meguru bachira x reader#chigiri x reader#isagi x reader#bachira x reader#itoshi rin x reader#blue lock x female reader#studio ghibli#ghibli films

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

what if emishi helped with the hotel?:3

I adore Emily

298 notes

·

View notes

Text

Understanding Princess Mononoke

People on twitter have asked me to write this up, after speaking just a bit about it on the bird plattform.

So, recently I rewatched Princess Mononoke and talked about it with a friend, who is Japanese with a degree in Japanese history. And I think some of it was rather interesting.

Some of you might already know this. But others might not. So just endulge me for a moment.

Let me start with Ashitaka. The movie does mention that he is Emishi - but many people are not aware, what this means.

See, Japan had quite a lot of indigenous cultures (I will talk more about those tomorrow). Most might know the Ainu, as they are still around today. Fewer might know about the Ryukyuan people of Okinawa, who are also still around. But there are several indigenous people, who have once lived in Japan, but whose culture hence had become instinct. The Emishi are one of them. They lived in Northern Honshu and their culture disappeared around the 10th century.

The movie, of course, takes place in the late 14th century, which is why the monk notes, that he knows what Ashitaka is, but will keep it secret. The idea is that Ashtakas little village had stayed secret to avoid being destroyed. As such Ashitaka has a different relation to the nature and the nature spirits than the other characters of the movie, who are to engrossed in the mainly Buddhist culture.

Another thing that has to be addressed is Iron Town and Lady Eboshi's people. According to the official Japanese material to the movie, Lady Eboshi once was a prostitute herself, who happened to get power by getting taken to China. Which is why she is in possession of the Chinese gun technology. She then decided to use that to allow herself power - but not entirely out of selfish reasons. Because she, of course, takes in untouchables. Japan, to this day, has an untouchable caste. Which are people who work certain "dirty" jobs or sicknesses. Most of the women in Iron Town are prostitutes who Eboshi had bought free from their brothels. And she wants to have a town where those people can live good lives.

Because of this she has to hope for the support of the Emperor, as the Samurai lords in the surrounding areas do not want her there.

Which brings me to the finale and killing the god. Here is a thing that you have to understand of Japanese history. The original indigenous people of Japan believed in nature spirits, that at times were actually gods. Especially mountain gods. As Buddhism spread (again, something I will talk about more tomorrow) the upper class went out to kill the gods.

Old Japanese history will talk about people killing gods in the same way, as we talk about St. Patrick and the snakes of Ireland. As if it has really happened.

And that is something that Eboshi tries to do. It is killing the old god, but more than that: killing the old culture.

One of the central conflicts the movie shows is, that the nature spirits are loosing their self-awareness. That they revert to normal animals. Because the indigenous culture that revered the nature spirits is fading away.

Which then is, why Ashitaka, who comes from one of those indigenous cultures, is the main character of the movie. Because he still has this connection to the nature spirit, that the other people have lost.

Yes, the movie is very solarpunk in hindsight. But it also understands what it means to loose connection to nature.

And I find that really beautiful.

#anime#anime movie#ghibli#studio ghibli#princess mononoke#solarpunk#indigenous peoples#nature#japanese history

925 notes

·

View notes

Text

Time Travel Question 16: Ancient History VII and Earlier

These Questions are the result of suggestions from the previous iteration.

This category may include suggestions made too late to fall into the correct grouping.

Please add new suggestions below if you have them for future consideration.

I am particularly in need of more specific non-European suggestions in particular, but all suggestions are welcome.

#Time Travel#Morocco#Phoenicia#The Mediterranean#The Xia Dynasty#Pompeii#Domestication#Agricultural Revolution#Finish history

317 notes

·

View notes

Text

Title: Love in the Shadows

Paring: Ashitaka x Reader (Princess Mononoke)

Word Count: 1.5k.

TW: gn!reader, one-sided love, slight angst, fluff at the end

divider by @saradika

The journey to the West had taken you farther than you had ever imagined. The forests, the spirits, the strange creatures—all of it seemed like a dream. But the reality was that you had chosen to follow Ashitaka, the brave prince from the Emishi tribe, on his quest to lift the curse that threatened his life. What you hadn't anticipated was the growing connection between him and San, the wolf girl.

The first time you saw them together, there was an undeniable spark. San, fierce and wild, yet gentle in her own way, seemed to understand Ashitaka in ways you couldn't. You had hoped to be his companion, his confidante, but watching them, you realized there was something deeper between them.

As days turned into weeks, you found yourself stepping back, giving them space. You pretended not to notice the way Ashitaka's eyes lit up when he talked about San, or the softness in his voice when he called her name. Your heart ached, but you hid it behind a smile, always supportive, always there for him.

One evening, as the sun set over the lush forest, you sat by a stream, lost in thought. Ashitaka had gone to meet San again, and you felt the familiar pang of loneliness. You had tried to keep your distance, to create opportunities for them to be alone. It was painful, but you believed it was for the best.

"This will be good for him," you thought to yourself, "he won't need me anymore." Placing your feet into the stream, you watch the golden rays of the sun turn the sky pink and gold over the forest as the water runs through your toes. Kodamas circle you as if keeping you company for your ever-growing loneliness.

Ashitaka, however, noticed your absence. At first, he didn't understand why you were always busy, always finding excuses not to spend time with him. Every time he would try to meet with you, you just brushed him off or hurried away to help the ladies of Iron Town. He saw you being pulled in different directions of the town, seeing you interact with the townspeople, smiling and laughing without him at your side.

He missed your presence, your laughter, the way you always seemed to know what he needed. It bothered him, more than he wanted to admit.

One night, after another meeting with San, he found you sitting alone, curled up by the fire. Your eyes drooped lazily, in a sleep haze, just looking at the flames. The light flickered on your face, casting shadows that mirrored the turmoil in your heart. He approached you, concern evident in his eyes.

"Why have you been avoiding me?" he asked softly.

You looked up, startled, and forced a smile. "I haven't been avoiding you, Ashitaka. I've just been busy."

He frowned, not convinced. "Busy with what? We're on this journey together. We've always faced everything together."

You sighed, knowing you couldn't keep lying to him. "Not anymore, my prince. We are no longer a pair. Ashitaka, you have San now. She needs you, and you need her. I don't want to get in the way."

His frown deepened, and he sat down beside you. "You're not in the way. You're my friend. I care about you."

Those words, meant to comfort, only made your heart ache more. You looked away, unable to meet his gaze. "I just think it's better this way."

He was silent for a long moment, and you could feel the weight of his stare. "Is that really what you want?"

No, it wasn't what you wanted. What you wanted was to be by his side, to share his burdens and his joys. But you couldn't say that. Instead, you nodded. "Yes. It's for the best."

Ashitaka didn't respond immediately. He seemed lost in thought, struggling with something within himself. Finally, he reached out, taking your hand in his. "I don't want to lose you. I can't lose you."

Your breath caught, and for a moment, you dared to hope. But you knew it was impossible. San had his heart, and you couldn't compete with that. "You won't lose me," you said, gently pulling your hand away. "I'll always be here for you, Ashitaka. Just… not in the same way."

Days passed, and despite your efforts to distance yourself, Ashitaka kept trying to reconnect. He sought you out, insisting on spending time together, even if it was just in silence. It was confusing, painful, and a constant reminder of what you couldn't have.

One evening, you were walking together through the forest in awkward silence. No conversations to fill up the space, just you and him walking along the trail. Feeling uncomfortable, you keep your eyes forward and look at the scenery.

Kodamas follow you two, smiley and jumping around your feet. Making sure to keep a good distance between you and him, you start to smile and play with the kodamas.

Realizing the physical space between the two of you, Ashitaka attempts to get closer to you. He took some larger steps and is now less than half an arm's length away from you. He observes your expressions of glee, interacting with the kodamas, and his heart pangs.

Why haven't you looked at him like that in so long? What has caused this change in your relationship with one another?

As he reaches out to grab your attention, you trip over a root and fly into the ground. Ashitaka quickly tries to hold you but ultimately fails. Instead, he opts to shield you from hitting the dirt, sending both of you tumbling down the small hill.

After some rolls, you guys eventually stop. Ashitaka, now leaning over you with his arms by your head, looks down at you wide-eyed. Both of you breathing hard, just bask in the after-effects of the fall. Realizing how precarious the position looks, you attempt to push him off and get up. He does not budge. You look up at him questionably.

Looking down at you and realizing he's got you trapped between his arms, he blurts the words that had been haunting him, "I've been thinking a lot about us. About you. You've always been there for me, even when I didn't realize it. And now, I don't want to lose that."

You stopped, your heart pounding. "Ashitaka…"

He shakes his head, "why have you been avoiding me? Do you no longer like me?"

"No!" you shout, "of course not. I've just been busy…"

He looks at you, unimpressed with your excuse.

You look to the side, unable to hold his gaze, "I've been putting distance between us so that you can hang out with San more."

"San?" He questions. "Why?"

"Well, I've seen how you look and talk about her. It's one of love and I'm not going to be the wall between you guys."

"Why? San is my friend and you are too."

You just continue looking away, tears starting to pool in your eyes. "Yes, you are my friend too."

Taken back by your glassy eyes, he backs up in surprise, allowing you to push him off and make your way back to the town.

"Wait!" he shouts, trailing after you, attempting to get your attention.

You continue walking away, arms wrapped around your body, ignoring him.

Catching up to you in quick strides, he wraps his arms around you. "You are special to me," he whispers. "You are the only one to stay by my side and hold strong to us. Please, don't leave me behind."

Tears now falling, "Ashitaka," you say shakily, "I love you."

His eyes widen but his hold tightens around you.

"I've put space between us because I know you love San and I want what's best for you."

Turning you around, he clasps the side of your arms. "San is only my friend. You are who I love!" he declares, face to face.

You stared at Ashitaka, his words echoing in your mind. He loved you. The truth of it struck you with an overwhelming mix of relief, joy, and disbelief. You had spent so long hiding your feelings, convinced that his heart belonged to San.

"Ashitaka, I..." you began, your voice trembling. "I thought you loved San. I saw the way you looked at her."

Ashitaka's grip on your arms tightened slightly, his eyes earnest and filled with emotion. "San is a dear friend, but my heart has always been with you. I just didn't realize it until you started pulling away. It made me see how much you mean to me, how much I need you."

Tears streamed down your face as you looked up at him, your heart swelling with hope.

A soft smile spread across Ashitaka's face, and he gently wiped away your tears. "Then let's not waste any more time," he said. "Let's face whatever comes together, as we always have."

He pulled you into a tender embrace, holding you close as if afraid to let go. You wrapped your arms around him, feeling the warmth of his body against yours, the steady beat of his heart. In that moment, all the pain and uncertainty melted away, replaced by the profound joy of being with the one you loved.

Ashitaka leaned in, his lips brushing against yours in a gentle, loving kiss. It was a promise, a testament to the journey you had shared and the future you would build together.

#ashitaka x reader#ashitaka#princess mononoke x reader#x reader#fluff#both are idiots#prince ashitaka#i want to see more fanfic for him#i hope you like it#my writing

82 notes

·

View notes

Text

KUTUNE SHIRKA

THE AINU EPIC

My foster-brother and foster-sister--

They it was who brought me up,

And so we lived.

~

мой старший/приемный братец

с сестрой моею (приемной)

меня растили

Авторы оставили в манге не мало отсылок к айнам, их культуре. Еще давно я изучала так называемые айнские баллады, в которых рассказывается о жизни и подвигах тысячиликого богочеловека, который помогал людям. (опущу множество интересных подробностей).

Примечательно, что в одном из песнопений рассказывается, что бог путешествовал с так называемыми братом и сестрой, которые не являлись ему родственниками, т е были названными. При этом "братец" был старшим.

Глядя на фреймы, эти айнские рассказы очень напоминают мне прежнюю жизнь Ято, Отца и Мизучи.

Что еще интересно, в рассказах упоминаются сокровища и морские выдры - сразу вспоминаю кабибар и их "страну", миф которой очень схож с Океанией 🌊

Это лишь один момент из огромного множества отсылок, но он особенно привлек мое внимание. Я давно замечаю на протяжении всей манги тонкую нить культурного кода айнов и допускаю, что одна из авторов тесно связана с данной культурой, так как параллели пущены особо трепетно, пока не погрузиться в эту интереснейшую тему - то просто не сможешь ничего увидеть 🙏

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

That last post just has me thinking a lot about how kids who just go straight through college after high school often don't understand that there's a shift in perspective you need to do.

High school is about answering questions that your teachers throw at you to see how much you know.

In college, there's some of that, but what your professors are trying to teach you is how to question the world yourself.

A high school history class teaches you about events, the order they happened in, and usually sone generally-agreed-upon thoughts about why they happened. A college history class says, "Here's what people say about how history happened. Is there anything here that we should be questioning?" Historian X claimed that Heian Era Japan was incredibly peaceful compared to other periods of Japanese history. Okay. Um, how are you defining "Japan" in that period? Is it all of the area controlled by the modern Japanese government? Because Heian Era Japan sure wasn't very peaceful for the Emishi and Ainu people who lived within that area and were at constant war with the Yamato-controlled states for that period of time. That kind of thing.

In college, you should learn not to take things for granted, and that is why totalitarian regimes of all sorts hate colleges and universities. Totalitarianism by definition requires that the people under its power have total belief in what the people at the top tell them about the nature of their reality. There is no room for people who question the premise of things.

39 notes

·

View notes