#Charles Lambert

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Title: The Bone Flower | Author: Charles Lambert | Publisher: Gallic Books (2022)

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

More parentification today

#sims#sims 3#sims 3 champs les sims#champs les sims#champs les sims townies#athena lambert#charles lambert

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

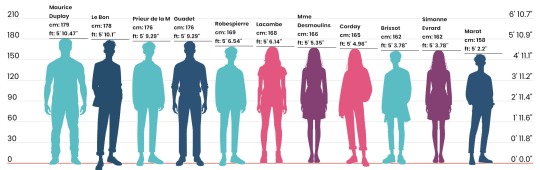

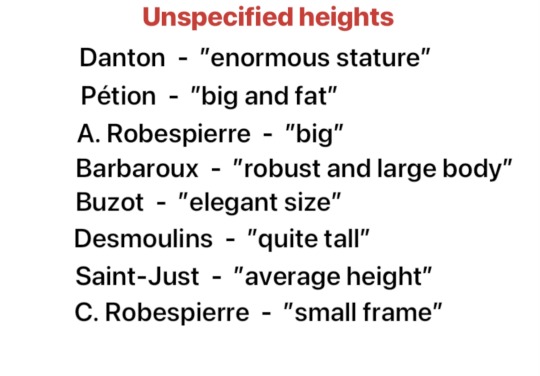

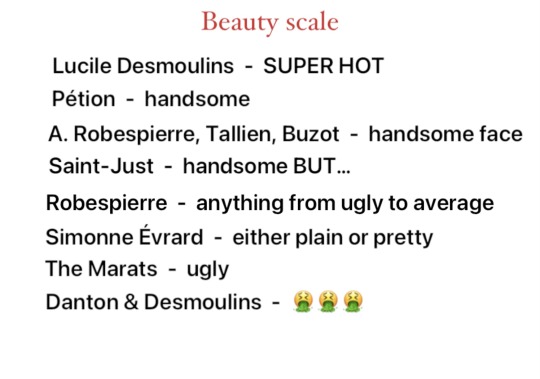

Frev appearance descriptions masterpost

Jean-Paul Marat — In Histoire de la Révolution française: 1789-1796 (1851) Nicolas Villiaumé pins down Marat’s height to four pieds and eight pouces (around 157 cm). This is a somewhat dubious claim considering Villiaumé was born 26 years after Marat’s death and therefore hardly could have measured him himself, but we do know he had had contacts with Marat’s sister Albertine, so maybe there’s still something to this. That Marat was short is however not something Villaumé is alone in claiming. Brissot wrote in his memoirs that he was ”the size of a sapajou,” the pamphlet Bordel patriotique (1791) claimed that he had ”such a sad face, such an unattractive height,” while John Moore in A Journal During a Residence in France, From the Beginning of August, to the Middle of December, 1792 (1793) documented that ”Marat is little man, of a cadaverous complexion, and a countenance exceedingly expressive of his disposition. […] The only artifice he uses in favour of his looks is that of wearing a round hat, so far pulled down before as to hide a great part of his countenance.” In Portrait de Marat (1793) Fabre d’Eglantine left the following very detailed description: ”Marat was short of stature, scarcely five feet high. He was nevertheless of a firm, thick-set figure, without being stout. His shoulders and chest were broad, the lower part of his body thin, thigh short and thick, legs bowed, and strong arms, which he employed with great vigor and grace. Upon a rather short neck he carried a head of a very pronounced character. He had a large and bony face, aquiline nose, flat and slightly depressed, the under part of the nose prominent; the mouth medium-sized and curled at one corner by a frequent contraction; the lips were thin, the forehead large, the eyes of a yellowish grey color, spirited, animated, piercing, clear, naturally soft and ever gracious and with a confident look; the eyebrows thin, the complexion thick and skin withered, chin unshaven, hair brown and neglected. He was accustomed to walk with head erect, straight and thrown back, with a measured stride that kept time with the movement of his hips. His ordinary carriage was with his two arms firmly crossed upon his chest. In speaking in society he always appeared much agitated, and almost invariably ended the expression of a sentiment by a movement of the foot, which he thrust rapidly forward, stamping it at the same time on the ground, and then rising on tiptoe, as though to lift his short stature to the height of his opinion. The tone of his voice was thin, sonorous, slightly hoarse, and of a ringing quality. A defect of the tongue rendered it difficult for him to pronounce clearly the letters c and l, to which he was accustomed to give the sound g. There was no other perceptible peculiarity except a rather heavy manner of utterance; but the beauty of his thought, the fullness of his eloquence, the simplicity of his elocution, and the point of his speeches absolutely effaced the maxillary heaviness. At the tribune, if he rose without obstacle or excitement, he stood with assurance and dignity, his right hand upon his hip, his left arm extended upon the desk in front of him, his head thrown back, turned toward his audience at three-quarters, and a little inclined toward his right shoulder. If on the contrary he had to vanquish at the tribune the shrieking of chicanery and bad faith or the despotism of the president, he awaited the reéstablishment of order in silence and resuming his speech with firmness, he adopted a bold attitude, his arms crossed diagonally upon his chest, his figure bent forward toward the left. His face and his look at such times acquired an almost sardonic character, which was not belied by the cynicism of his speech. He dressed in a careless manner: indeed, his negligence in this respect announced a complete neglect of the conventions of custom and of taste and, one might almost say, gave him an air of ressemblance.”

Albertine Marat — both Alphonse Ésquiros and François-Vincent Raspail who each interviewed Albertine in her old age, as well as Albertine’s obituary (1841) noted a striking similarity in apperance between her and her older brother. Esquiros added that she had ”two black and piercing eyes.” A neighbor of Albertine claimed in 1847 that she had ”the face of a man,” and that she had told her that ”my comrades were never jealous of me, I was too ugly for that” (cited in Marat et ses calomniateurs ou Réfutation de l’Histoire des Girondins de Lamartine (1847) by Constant Hilbe)

Simonne Evrard — An official minute from July 1792, written shortly after Marat’s death, affirmed the following: “Height: 1m, 62, brown hair and eyebrows, ordinary forehead, aquiline nose, brown eyes, large mouth, oval face.” The minute for her interrogation instead says: “grey eyes, average mouth.”Cited in this article by marat-jean-paul.org. When a neighbor was asked whether Simonne was pretty or not around two decades after her death in 1824, she responded that she was ”très-bien” and possessed ”an angelic sweetness” (cited in Marat et ses calomniateurs ou Réfutation de l’Histoire des Girondins de Lamartine (1847) by Constant Hilbe) while Joseph Souberbielle instead claimed that ”she was extremely plain and could never have had any good looks.”

Maximilien Robespierre — The hostile pampleth Vie secrette, politique et curieuse de M. J Maximilien Robespierre… released shortly after thermidor by L. Duperron, specifies Robespierre’s hight to have been ”five pieds and two or three pouces” (between 165 and 170 cm). He gets described as being ”of mediocre hight” by his former teacher Liévin-Bonaventure Proyart in 1795, ”a little below average height” by journalist Galart de Montjoie in 1795, ”of medium hight” by the former Convention deputy Antoine-Claire Thibaudeau in 1830 and ”of middling form” by his sister in 1834, but ”of small size” by John Moore in 1792 and Claude François Beaulieu in 1824. The 1792 pampleth Le véritable portrait de nos législateurs… wrote that Robespierre lacked ”an imposing physique, a body à la Danton,”supported by Joseph Fiévée who described him as ”small and frail” in 1836, and Louis Marie de La Révellière who said he was ”a physically puny man” in his memoirs published 1895. For his face, both François Guérin (on a note written below a sketch in 1791), Buzot in his Mémoires sur la Révolution française (written 1794), Germaine de Staël in her Considerations on the Principal Events of the French Revolution (1818), a foreign visitor by the name of Reichardt in 1792 (cited in Robespierre by J.M Thompson), Beaulieu and La Révellière-Lépeaux all agreed that he had a ”pale complexion.” Charlotte does instead describe it as ”delicate” and writes that Maximilien’s face ”breathed sweetness and goodwill, but it was not as regularly handsome as that of his brother,” while Proyart claims his apperance was ”entirely commonplace.” The foreigner Reichardt wrote Robespierre had ”flattened, almost crushed in, features,” something which Proyart agrees with, writing that his ”very flat features” consisted of ”a rather small head born on broad shoulders, a round face, an indifferent pock-marked complexion, a livid hue [and] a small round nose.” Thibaudeau writes Robespierre had a ��thin face and cold physiognomy, bilious complexion and false look,” Duperron that ”his colouring was livid, bilious; his eyes gloomy and dull,” something which Stanislas Fréron in Notes sur Robespierre (1794) also agrees with, claiming that ”Robespierre was choked with bile. His yellow eyes and complexion showed it.” His eyes were however green according to Merlin de Thionville and Guérin while Proyart insists they were ”pale blue and slightly sunken.” Etienne Dumont, who claimed to have talked to Robespierre twice, wrote in his Souvernirs sur Mirabeau et sur les deux premières assemblées législatives (1832) that ”he had a sinister appearance; he would not look people in the face, and blinked continually and painfully,” and Duperron too insists on ”a frequent flickering of the eyelids.” Both Fréron, Buzot, Merlin de Thionville, La Révellière, Louis Sébastien Mercier in his Le Nouveau Paris (1797) and Beffroy de Reigny in Dictionnaire néologique des hommes et des choses ou notice alphabétique des hommes de la Révolution, qui ont paru à l’Auteur les plus dignes d’attention… (1799) made the peculiar claim that Robespierre’s face was similar to that of a cat. Proyart, Beaulieu and Millingen all wrote that it was marked by smallpox scars, ”mediocretly” according to Proyart, ”deeply” according to the other two. Proyart also writes that Robespierre’s hair was light brown (châtain-blond). He is the only one to have described his hair color as far as I’m aware.

For his clothes, both Montjoie, Louis-Sébastien Mercier in 1801, Helen Maria Williams in 1795, Duperron, Millingen and Fiévée recall the fact that Robespierre wore glasses, the first two claiming he never appeared in public without them, Duperron that he ”almost always” wore them, and Millingen that they were green. Pierre Villiers, who claimed to have served as Robespierre’s secretary in 1790, recalled in Souvenirs d'un deporté (1802) that Robespierre ”was very frugal, fastidiously clean in his clothes, I could almost say in his one coat, which was was of a dark olive colour,” but also that ”He was very poor and had not even proper clothes,” and even had to borrow a suit from a friend at one point. Duperron records that ”[Robespierre’s] clothes were elegant, his hair always neat,” Millingen that ”his dress was careful, and I recollect that he wore a frill and ruffles, that seemed to me of valuable lace,”Charlotte that ”his dress was of an extreme cleanliness without fastidiousness,” Williams that he ”always appeared not only dressed with neatness, but with some degree of elegance, and while he called himself the leader of the sans-culottes, never adopted the costume of his band. His hideous countenance […] was decorated with hair carefully arranged and nicely powdered,” Fiévée that Robespierre in 1793 was ”almost alone in having retained the costume and hairstyle in use before the Revolution,” something which made him ressemble ”a tailor from the Ancien régime,” Thibadeau that ”he was neat in his clothes, and he had kept the powder when no one wore it anymore,” Germaine de Staël that ”he was the only person who wore powder in his hair; his clothes were neat, and his countenance nothing familiar,” Révellière writes that Robespierre’s voice was ”toneless, monotonous and harsh,” Beaulieu that it ”was sharp and shrill, almost always in tune with violence,” and Thinadeau that his ”tone” was ”dogmatic and imperious.”

Augustin Robespierre — described as ”big, well formed, and [with a] face full of nobility and beauty” in the memoirs of his sister Charlotte. Charles Nodier did in Souvenirs, épisodes et portraits pour servir à l'histoire de la Révolution et de l'Empire (1831) recall that Augustin had a ”pale and macerated physiognomy” and a quite monotonous voice.

Charlotte Robespierre — an anonymous doctor who claimed to have run into Charlotte in 1833, the year before her death, described her as ”very thin.” Jules Simon, who reported to have met her the following year, did him too describe her as ”a very thin woman, very upright in her small frame, dressed in the antique style with very puritanical cleanliness.”

Camille Desmoulins — described as ”quite tall, with good shoulders” in number 16 of the hostile journal Chronique du Manège (1790). Described as ugly by both said journal, the journal Journal Général de la Cour et de la Ville in 1791, his friend François Suleau in 1791, former teacher Proyart in 1795, Galart de Montjoie in 1796, Georges Duval in 1841, Amandine Rolland in 1864 (she does however add that it was ”with that witty and animated ugliness that pleases”) and even himself in 1793. Proyart describes his complexion as ”black,” Duval as ”bilious.” Both of them agree in calling his eyes ”sinister.” Duval also claims that Desmoulins’ physiognomy was similar to that of an ospray. Montjoie writes that Desmoulins had ”a difficult pronunciation, a hard voice, no oratorical talent,” Proyart that ”he spoke very heavily and stammered in speech” and Camille himself that he has ”difficulty in pronunciation” in a letter dated March 1787, and confesses ”the feebleness of my voice and my slight oratorical powers” in number 4 of the Vieux Cordelier. In his very last letter to his wife, dated April 1 1794, Desmoulins reveals that he wears glasses.

Lucile Desmoulins — The concierge at the Sainte-Pélagie prison documented the following when Lucille was brought before him on April 4 1794: ”height of five pieds and one and a half pouce (166 cm). Brown hair, eyebrows and eyes. Middle sized nose and mouth. Round face and chin. Ordinary front. A mark above the chin on the right.” Cited in Camille et Lucile Desmoulins: un rêve de république (2018). Described as beautiful by the journal Journal Général de la Cour et de la Ville in 1791 (it specifies her to be ”as pretty as her husband is ugly”), former Convention deputy Pierre Paganel in 1815, Louis Marie Prudhomme in 1830, Amandine Rolland in 1864 and Théodore de Lameth (memoirs published 1913).

Georges Danton — Described as having an ugly face by both Manon Roland in 1793, Vadier in 1794, the anonymous pamphlet Histoire, caractère de Maximilien Robespierre et anecdotes sur ses successeurs in 1794, Louis-Sébastien Mercier in 1797, Antoine Fantin-Desodoards in 1807, John Gideon Millingen in 1848, Élisabeth Duplay Lebas in the 1840s, the memoirs (1860) of François-René Chateaubriand (he specifies that Danton had ”the face of a gendarme mixed with that of a lustful and cruel prosecutor”) as well as the Mémoires de la Societé d’agriculture, commerce, sciences et arts du department de la Marse, Chalons-sur-Marne (1862). As reason for this ugliness, Millingen lifts his ”course, shaggy hair” (that apparently gave him the apperance of a ”wild beast”), the fact he was deeply marked with small-poxes, and that his eyes were unusually small (”and sparkling in surrounding darkness”), while Chateaubriand instead underlines that he was ”snub-nosed,” with ”windy nostrils [and] seamed flats.” Mercier writes that Danton’s face was ”hideously crushed.” The former Convention deputy Alexandre Rousselin (1774-1847) reported in his Danton — Fragment Historique that Danton developed a lip deformity after getting gored by a bull as a baby, had his nose crushed by another bull, got trampled in the face by a group of pigs and finally survived ”a very serious case of smallpoxes, accompanied by purpura.” In 1792, John Moore reported that ”Danton is not so tall, but much broader than Roland; his form is coarse and uncommonly robust,” while Vadier claims that Danton possessed a ”robust form, colossal eloquence,” the anonymous pamphlet that ”he was very strong, he said himself that he had athletic forms,” Desodoards that he ”held the nature of athletic and colossal forms,” Chateaubriand that he was ”a vandal in the size of Goth” (don’t know who he’s referring to), Pierre Paganel (in Essai historique et critique sur la révolution française: ses causes, ses résultats, avec les portraits des hommes les plus célèbres (1815)) that he was of an ”enormous stature,” while the pamphlet described him as a ”gigantic orator” whose voice ”shook the vaults of the hall.” René Levasseur in 1829, John Moore, Millingen, Paganel and Desodoards all agreed with this, the first four writing that Danton possessed a ”stentorian voice,” the latter that he had ”a very strong voice, without being sonorous or flexible.” In her memoirs (1834) Charlotte Robespierre claims that ”[Danton] did not at all conserve the dignity suited to the representative of a great people in his manners; his toilette was in disorder.”

Louis Antoine Saint-Just — In Saint-Just (1985) Bernard Vinot writes that Saint-Just’s childhood friend Augustin Lejeune recalled his “honest physiognomy,” and that his sister Louise would evoke her brother’s ”great beauty” for her grandchildren (I unfortunately can’t find the original sources here). The elderly Élisabeth Le Bas too stated that ”he was handsome, Saint-Just, with his pensive face, on which one saw the greatest energy, tempered by an air of indefinable gentleness and candor” (testimony found in Les Carnets de David d’Angers (1838-1855) by Pierre-Jean David d’Angers, cited in Veuve de Thermidor: le rôle et l'influence d'Élisabeth Duplay-Le Bas (1772-1859) sur la mémoire et l'historiographie de la Révolution française (2023) by Jolène Audrey Bureau, page 127). In Souvenirs de la révolution et de l’empire, Charles Nodier (who was twelve years old when he met Saint-Just…) agrees in calling him ”handsome,” but adds that he ”was far from offering this graceful combination of cute features with which we have seen it endowed by the euphemistic pencil of a lithograph,” had an ”ample and rather disproportionate chin,” that ”the arc of his eyebrows, instead of rounding into smooth and regular semi-circles, was closer to a straight line, and its interior angles, which were bushy and severe, merged into one another at the slightest serious thought that one saw pass on his forehead” and finally that ”his soft and fleshy lips indicated an almost invincible inclination to laziness and voluptuousness.” How would you know what his lips were like, Nodier. In Essai historique et critique sur la révolution française (1815) Pierre Paganel writes that Saint-Just had ”regular features and austere physiognomy.” He describes his complexion as ”bilious” while Nodier calls it ”pale and grayish, like that of most of the active men of the revolution.” Similar to Élisabeth’s description, Nodier writes that Saint-Just’s eyes were big and ”usually thoughtful,” while Paganel instead writes they were ”small and lively.” Saint-Just was of ”average height” according to Paganel, but ”of small stature” according to Nodier. According to Paganel, Saint-Just had a ”healthy body [and] proportions which expressed strength,” while Saint-Just’s colleague Levasseur de la Sarthe instead wrote in his memoirs that he was ”weak in body, to the point of fearing the whistling of bullets.” Finally, Paganel also gives the following details: ”large head, thick hair, disdainful gaze, strong but veiled voice, a general tinge of anxiety, the dark accent of concern and distrust, an extreme coldness in tone and manners.” In Lettre de Camille Desmoulins, député de Paris à la Convention, August général Dillon en prison aux Madelonettes (1793) Desmoulins jokingly writes that ”one can see by [Saint-Just’s] gait and bearing that he looks upon his own head as the corner-stone of the Revolution, for he carries it upon his shoulders with as much respect and as if it was the Sacred Host.” In Histoire de la Révolution française(1878), Jules Michelet claims that Élisabeth Le Bas had told him that this portrait, depicting Saint-Just as having ”a very low forehead, [with] the top of his head flattened, so that his hair, without being long, almost touched his eyes,” was similar to what he had looked like.

Jacques-Pierre Brissot — The following was documented after Brissot had been arrested at Moulins on June 10 1793 — ”height of five pieds (162 cm), a small amount of flat dark brown hair, eyebrows of the same color, high forehead and receding hairline, gray-brown, quite large and covered eyes, long and not very large nose, average mouth, long chin with a dimple, black beard, oval face narrow at the bottom” (cited in J.-P. Brissot mémoires (1754-1793); [suivi de] correspondance et papiers (1912)). In Journal During a Residence in France, from the Beginning of August, to the Middle of December, 1792 John Moore described Brissot as ”a little man, of an intelligent countenance, but of a weakly frame of body” and claimed that a person had told him that Brissot had told him that he is ”of so feeble a constitution” that he won’t be able to put up any resistance was someone try to assassinate him.

Jérôme Pétion — described as ”big and fat” (grand et gros) by Louis-Philippe in 1850 (cited in The Croker Papers: the Correspondence and Diaries of the late right honourable John Wilson Croker… (1885) volume 3, page 209). Manon Roland wrote in her memoirs that Pétion ”had nothing to regret physically; his size, his face, his gentleness, his urbanity, speak in his favor” as well as that he ”spoke fairly well,” a descriptions which Louis Marie Prudhomme partly agreed with, himself recording that Pétion ”had a proud countenance, a fairly handsome face, an affable look, a gentle eloquence, movements of talent and address; but his manners were composed, his eyes were dull, and he had something glistening in his features which repelled confidence” in Paris pendant le révolution (1789-1798) ou le nouveau Paris (1798). In Quelques notices pour l’histoire, et le récit de mes périls depuis le 31 mai 1793 (1794) Jean-Baptiste Louvet reported that, while on the run from the authorities after the insurrection of May 31, the less than forty years old Pétion already had a white hair and beard. This is confirmed by Frédéric Vaultier, who in Souvenirs de l'insurrection Normande, dite du Fédéralisme, en 1793 (1858) described Pétion during the same period as ”a good-looking man, with a calm and open physiognomy and beautiful white hair,” as well as by the examination of his mangled courpse on June 26 1794, which states he had ”grayish hair” (cited in Charlotte de Corday et les Girondins: pièces classées et annotées (1872) by Charles Vatel, volume 2, page 154.

François Buzot — according to the memoirs (1793) of Manon Roland, he had ”a noble figure and elegant size.” In the examination made of Buzot’s body after the suicide there is to read that he had black hair (cited in Charlotte de Corday et les Girondins: pièces classées et annotées (1872) by Charles Vatel, volume 2, page 153)

Charles Barbaroux — his son wrote in Jeunesse de Barbaroux (1822) that ”nature had richly endowed Barbaroux; a robust and large body; a charming, fine and witty physiognomy.” In 1867, François Laprade, who had witnessed Barbaroux’ execution as a thirteen year old, recollected that ”he was a brown man - that is to say he had brownish skin, black hair and beard, reclining figure” (cited in Charlotte de Corday et les Girondins: pièces classées et annotées, volume 3, page 728)

Marguerite-Élie Guadet — According to his passport (cited in Charlotte de Corday et les Girondins: pièces classées et annotées, volume 3, page 672): ”height of 5 pieds, 5 pouces (176 cm) middle sized mouth, black hair and eyebrows, ordinary chin, blue eyes, big forehead, thin face, upturned nose.” According to Frédéric Vaultier’s Souvenirs de l'insurrection Normande, dite du Fédéralisme, en 1793(1858), ”Guadet was a man of fine height, meagre, brown, bilious complexion, black beard, most expressive face.”

Joseph Le Bon — his passport description (cited in Louis Jacob, Joseph Le Bon, (1932) by Louis Jacob, volume 1, page 63) gives the following information: ”Height of five pieds six pouces (178 cm), light brown hair and eyebrows, high forehead, average nose, blue eyes, medium-sized mouth, smallpox scars.”

Claire Lacombe — the concierge of the Sainte Pélagie documented the following about the imprisoned Lacombe: ”height of 5 pieds, 2 pouces (168 cm). Brown hair, eyebrows and eyes, medium nose, large mouth, round face and chin, plain forehead” (cited in Trois femmes de la Révolution : Olymps de Gouges, Théroigne de Méricourt, Rose Lacombe (1900) by Léopold Lacour)

Charlotte Corday — according to her passport, ”height of five pieds one pouce (165 cm), brown hair and eyebrows, gray eyes, high forehead, long nose, medium mouth, round, forked (fourchu) chin, oval face.” (cited in Dossiers du procès criminel de Charlotte Corday, devant le Tribunal révolutionnaire(1861) by Charles-Joseph Vatel, page 55)

Prieur de la Marne — a passport dated October 1 1793 gives the following details: ”age of 37 years, height of 5 pieds 5 pouces (176 cm), blondish brown hair and eyebrows, receding hairline, long nose, grey eyes, large mouth.”

Maurice Duplay — ”height of 5 pieds 6 pouces (179 cm), blondish brown hair and eyebrows, receding hairline, grey eyes, long, open nose, large mouth, round, full chin and face.” Descriptions given in 1795 and cited in Les deniers montagnards (1874) by Jules Claretie.

Jean Lambert Tallien — Both a spy report written in 1794 found among Robespierre’s papers and Mme de la Tour du Pin, a noblewoman who met Tallien in late 1793, describe Tallien’s hair as blonde. Mme de la Tour du Pin adds that said hair was curly and that he had a pretty face.

#might eventually reblog a part 2 i ran out of links for the moment#frev#french revolution#robespierre#georges danton#jean paul marat#albertine marat#simonne évrard#maximilien robespierre#augustin robespierre#camille desmoulins#desmoulins#lucile desmoulins#charlotte robespierre#charlotte corday#brissot#pétion#prieur de la marne#maurice duplay#jean lambert tallien#joseph lebon#charles barbaroux#françois buzot#saint-just#louis antoine de saint just#yes robespierre was taller than brissot this is no drill#i like this beauty and the beast thing camille and lucile seemed to have going tho…

249 notes

·

View notes

Text

🗯️Seeking Fandom Based Roleplay Partners🗯️

A little bit about me: you can call me Wyrm! I am 32, trans man(He/him) with ADHD. I have been roleplaying for over half my life though said life has been hectic so it’s been a few months since I’ve last role played in any complicity so I may be a bit rusty.

I write a couple to several paragraphs, and definitely like to keep things moving. I reply once a day usually but can also get a tad obsessed and go several times a day. But life does happen so we can communicate and be understanding.

What I’m looking for: I am a sucker for AUs, omegaverse, arranged marriages, drama, plot and yes, NSFW. I can get dark but also respect boundaries.

99% of my pairings are mxm or mlm and always cc x cc. I don’t personally care for OCs. I don’t mind side pairing being other combinations of genders but I am a gay man so I would like the main focus to be gay. Non binary or trans interpretations of characters are also encouraged. Give me all the head canons.

Fandoms I am looking for and pairings(who I would like to play is *italicized*. It’s not set in stone though so feel free to ask)

X-men(mostly movies)

*Charles* x *Erik*

Logan x *Scott*

Logan x *Kurt*

DC

*Clark Kent* x Bruce Wayne

The Sandman

Dream x *Hob*

The Witcher

*Jaskier* x *Geralt*

Lambert x *Aiden*

Coen x *Eskel*

*Eskel* x *Geralt*

Harry Potter

Remus x *Sirius*

*James* x Regulus

I only rp on discord, but if any of this sounds interesting to you, please shoot me a message! I would be happy to chat and hopefully start a fun story!

#roleplay#roleplay search#1 x 1 rp#1 x 1 roleplay#mxm#m x m rp#mlm#mlm roleplay#fandom roleplay#fandom rp#cc x cc rp#x men#x men roleplay#x men rp#cherik#charles x erik#logurt#logan x kurt#logan x scott#superbat#the sandman#dreamling#dream x hob#the witcher#geraskier#jaskier x witchers#geralt x eskel#lambert x aiden#wolfstar#jegulus

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

So,this has been around twitter. I have a guess on what’s happening. Let’s look at the clock. The clock shows the Nighthawks, which means this is Hatchetfield. Lambert Productions is in London. While people speculate another London tour, I think not. Let’s look at the clock. It shows 12:05, and well, December 5th has already passed, but look at the seconds clock. It’s at the 19th second. So the time showed is 12:05:19…December…5+19, which equals 24. This shows that they will be announcing something on Christmas Eve. If it’s so Hatchetfield themed then it can’t be a tour can it? Tours showcase ALL musicals, not JUST the Hatchetfield trilogy, which is why I think we will be getting LONDON CASTS FOR THE HATCHETFIELD TRILOGY!!! AND THE FULL THING WILL BE ANNOUNCED ON CHRISTMAS EVE!!! Thank you for coming to my Ted Talk.

#curt mega#kim whalen#jon matteson#jeff blim#corey dorris#angela giarratana#mariah rose faith casillas#lauren lopez#joey richter#will branner#starkid npmd#npmd#bryce charles#london#starkid innit#lambert jackson#omg guys guys guys i guessed it#christmas eve#starkid

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

My gifs from an old video!!

Eddie Redmayne for VOGUE GREECE October, 2022, wearing Gucci and Ferragamo.

Photographed by Johan Sandberg

Styled by Harry Lambert

Groomed by Petra Sellge

#eddie redmayne#the good nurse#charles cullen#netflix movie#netflix crime#vogue greece#old video#my gifs#johan sandberg#photographer#harry lambert#styling#petra sellge#groomer#charles graeber#writer#cabaret#kit kat club#nyc#oscar winner#best actor#the theory of everything#the danish girl#newton scamander#obe#talent#stephen hawking#les miserables#fantastic beasts#the trial of the chicago 7

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

I've dove back into an old hyperfixation. Y'ALL CAN'T TOUCH ME.

IDFK what I'm doing but... I'm doing it. Send asks, please...

#izombie#cw#spn got me braindead#sorta accidentally lunged myself back into a show my younger self was obsessed with and im not going to apologize for it#i need the distraction#okay?#especially with loki gone and all#ugh i hate this#liv moore#clive babineaux#ravi chakrabarti#peyton charles#major lilywhite#blaine debeers#don e#enzo lambert#vampire steve

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

This Leather Brown Jacket/jerkin is worn on Howard Charles as Porthos in The Musketeers: The Prodigal Father (2015) and later worn on Paul Bullion as Lambert in The Witcher: What Is Lost (2021)

#recycled costumes#bbc musketeers#howard charles#porthos#the witcher#paul bullion#lambert#period drama#historical drama#costume drama#reused costume#reused costumes#costumes#perioddramaedit#perioddramasource#dramasource#period dramas

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

French aviator Charles de Lambert flying over Paris

French vintage postcard

#paris#postal#vintage#postkaart#flying#charles#ansichtskarte#photo#lambert#charles de lambert#tarjeta#ephemera#french#aviator#sepia#postkarte#carte postale#briefkaart#photography#postcard#historic

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Well, we got about an hour before the orcs come on and then she’ll be down here like a shot. (Part 2)

Jack and Diane celebrate in the pub with Jack getting drunk. While they are away, Robert and Katie ‘try’ to have some alone time but there are interruptions courtesy of Victoria (12 hour director’s cut of LOTR will keep her occupied to an extent 😂). And the whinging continues from Scott like a broken record. Jack gives Robert Andy’s gift and it’s something he was actually looking for (and Andy wouldn’t have been aware of).

22-Apr-2005

#classic ED#classic ED robert’s story#part two of the episode#episode 4031#20050422#classic ED 2005#200504#a drunk jack#diane sugden#jack sugden#louise appleton#bob hope#jarvis skelton#val lambert#scott windsor#dawn woods#andy sugden#libby charles#paul lambert#jack and diane celebrate#alone time for loved up robert and katie#happiness to destruction soon#director’s cut of LOTR for victoria’s viewing#lovely shirt for robert#robert the geek#sigh miss the channel being HD the difference is notable

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

The End of the Commonwealth 1659-60: ‘according to the ancient and fundamental laws of this kingdom, the Government is, and ought to be, by Kings, Lords and Commons’

George Monck Makes His Move

General George Monck Entering London with His Troops. Source: Mary Evans Picture Library website

THE FINAL days of the Commonwealth were filled with the very unresolved issues that had dogged the English republican experiment from its start - the question of legitimacy, the unsettled balance of power between the various postwar factions and the yearning of the populace for stable government. However, England’s civil wars had one last drama to play out before the Commonwealth’s denouement.

The Royalist plotters of the Sealed Knot, observing the crisis of the post-Protectorate regime, thought their time had come at last to seize the initiative by force. In July 1659, a series of uprisings across northern England was planned to overthrow the Rump and invite Charles II to assume the throne. As with other of the Sealed Knot’s schemes, this plot was also uncovered and then called off by its instigators, but not before Sir Thomas Myddleton had declared for the King in Wrexham and the Earl of Derby had entered England from the Isle of Man to try to incite Lancashire to rise. Neither succeeded in attracting much support, but Sir George Booth, a local landowner, mayor of Chester, and, significantly a former Parliamentarian, raised an army of 4,000 and proclaimed his support, less for a restored monarchy and more for a fresh Parliament, legitimised by new elections. This call for full Parliamentary representation became the increasing slogan of the growing opposition to the Army and England’s republic. Booth may have anticipated a coming public mood, but that mood was not universal yet. With no other anti-Rump force in the field, Booth headed to Manchester, pursued by a small Parliamentary force under the command of John Lambert. On 18th August the two armies clashed at Hartford Beech in Cheshire. The experienced Parliamentary force soon had the better of what turned out to be a set of running skirmishes until the Royalists finally routed as they attempted to cross Winnington Bridge. Both Myddleton and, eventually, Booth, were captured and the defeated Royalist soldiery were allowed to return to their homes. So ended the last set piece battle of the English civil wars.

Any Parliamentary solidarity that may have been engendered by this brief renewal of fighting in England, did not last long. Lambert, newly emboldened, was determined this time to secure the supreme leadership role he had denied himself after Cromwell’s death out of loyalty to his former commander. His opportunity came when his regiments, based in Derby, issued a proclamation to the Rump, requiring the granting of all the Army’s demands concerning pay, indemnity, religious toleration, the maintenance of republican government and the purging of “delinquent” MPs opposed to the military. Included in the demands was Lambert’s own elevation to second-in-command of the Army under General Charles Fleetwood. Naturally the Rump could not agree to what became termed the “Derby Petition” and retaliated by ordering Fleetwood to arrest Lambert in early October and issued an ordnance overturning all legislation passed during the Protectorate and requiring its validation by the House of Commons. In addition, under the lead of Arthur Heselrige, the Rump passed a further ordnance that reserved all tax-raising powers to the House of Commons and set about establishing a committee to take the control of the Army, ordering the London regiments to rally to defend Parliament. In the event, and perhaps unsurprisingly, it was the Army that won this stand-off: Fleetwood refused to move against Lambert who called on the same London regiments to muster and protect the Commonwealth. This they did, leading to the dissolution of the Rump Parliament yet again by military coup, and the establishment of a Committee of Safety to run the country by the Army’s Council of Officers.

Fleetwood and Lambert were in charge, but they had no practical plan as to what to do next. Lambert favoured restoration of the Protectorate, with himself as Lord Protector, but there was little appetite for this, even within the Army. The Committee of Safety could keep order, but in the absence of Parliament or constitution, it could neither raise taxes nor legitimise its role. It was a stop-gap, and the supporters of the Parliamentary cause saw no alternative to elections to a new and representative lower House. What was new however, was that in their determination to oppose both military rule and, as they saw it, the barely controlled radicalism on the part of the common soldiers, these former enemies of Charles I began to see the restoration of the monarchy as the only way out of this impasse, much to the surprise and delight of the exiled Stuart Court.

Meanwhile, in Scotland, General George Monck observed events south of the border enigmatically. He possessed the only military force of sufficient size and experience capable of challenging Fleetwood and Lambert, but his intentions were far from clear. Although Monck had sent sympathetic messages to Heselrige, he made no move to support the Rump or prevent its dissolution. Charles’ emissaries had contacted him offering the general vast rewards if he would defect to the Royalist side, but Monck had rebuffed their advances. Equally, he had not declared support for Committee of Safety either. The former Royalist turned Cromwellian loyalist was however about the enter the fray of Commonwealth politics decisively.

On 20th October, Monck declared his hand. He stated that he supported Parliamentary government and demanded the Council of Officers recall Parliament, threatening to bring his army into England in order to enforce this if necessary. Lambert and Fleetwood did not react well to this interference from their brother officer and prepared to resist any such incursion from Scotland. Lambert headed north to Newcastle, to rally the New Model forces there, but found to his consternation that the northern army was filled with dissent, infuriated at lack of pay and promised pensions, and that the soldiers too had joined the calls for new elections. Lambert succeeded in calming some of the agitation and he and Monck faced each other warily across the Scottish border. The issue was forced in November when in the south and in Ireland, the troops rebelled and demanded the recall of Parliament. When the fleet revolted too, threatening to blockade the Thames until the House of Commons sat again, Lambert, with his forces of questionable loyalty, knew his game was up. This was confirmed when the aged Sir Thomas Fairfax emerged from retirement to call for the restoration of Parliamentary rule. The northern armies deserted to the much-loved former commander en masse, leaving Lambert with no army and no options.

In December, military rule effectively fell apart, driven as much by the Council of Officers’ inability to pay the men as by the simultaneous and insistent, calls for the restoration of Parliamentary rule. On 26th December, Fleetwood and Lambert were forced to recall the Rump whose first action was to place the Army under Parliamentary control. Lambert, trapped between Monck’s forces and Fairfax’s new volunteer army of deserters, could not prevent this. On New Year’s Day 1660, Monck’s army crossed the Tweed and proceeded south, meeting no resistance. In fact, the Rump had told Monck that with the collapse of the coup, they no longer needed his presence in London, but the general proceeded to the capital anyway. The restoration of the Rump was only the first step in the ever-mysterious Monck’s probable plan.

As for Lambert, he submitted to the authority of the Rump and was immediately arrested and confined in the Tower of London. He would remain a prisoner for the rest of his days, finally dying, almost certainly suffering from dementia, in 1684. It was a sad end to one of the Commonwealth’s most capable politicians and soldiers. If, as he had wished, and others had urged, Cromwell had nominated Lambert as his successor and not his ineffective son, Lambert may have made a success both of the Protectorate and the English republic. Lambert in power would certainly have introduced a written constitution to England, with the formal checks and balances the British system of government lacks to this day. With Lambert leading the country in the late 1650s, the path to the Stuart restoration may have been blocked forever.

Once he reached London, Monck’s alliance of convenience with the Rump swiftly came to an end. It became clear that Heselrige and his allies were intent on calling highly restrictive elections that would ensure that only MPs who supported the Rump’s quasi-republican agenda would be able to serve. When in February, the Rump fell into dispute with the City of London council over proposed tax increases, and ordered Monck to suppress the Council, the general refused. Instead he gave the Rump seven days to dissolve itself and arrange full, unrestricted national elections. Given the impossibility of this deadline, a compromise was reached through an agreement to the restitution of the previous Parliament - the so-called Long Parliament - originally summoned by Charles I in November 1640, and forcibly dissolved in Pride’s Purge. The purged MPs returned to Westminster in triumph, escorted by Monck’s soldiers. The Long Parliament’s sole items of business were to confirm Monck as commander-in-chief of the Army, and to agree a date for its own dissolution and the calling of new elections. This it did on 16th March 1660.

Monck’s ultimate desire to see Charles II restored to his throne slowly became plain. As arrangements for elections were put into place, the general at last openly communicated with the Stuart court, which had transferred its location to Breda in Holland. But the enigma of Monck persisted: he was no political Royalist. He informed Charles’ emissaries that the King’s return to England would not be without conditions. There would be an amnesty for all who fought against the Crown in the civil wars; all sales of Royalist lands would remain in place; a degree of religious tolerance would be afforded, and the King would rule jointly with his Parliament. As the path for the unlikely restoration of a somewhat altered monarchy was cleared, John Pym would probably have approved.

#english civil war#john lambert#the english commonwealth#english republicanism#charles ii#charles fleetwood#Arthur Heselrige#George monck

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Title: The Children's Home | Author: Charles Lambert | Publisher: Scribner (2016)

1 note

·

View note

Photo

All I do is take pictures of Athena taking care of her brother Charles. Parentification aside, it’s so cute!

#sims#sims 3#sims 3 champs les sims#champs les sims#champs les sims townies#pesce legacy#athena lambert#charles lambert

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

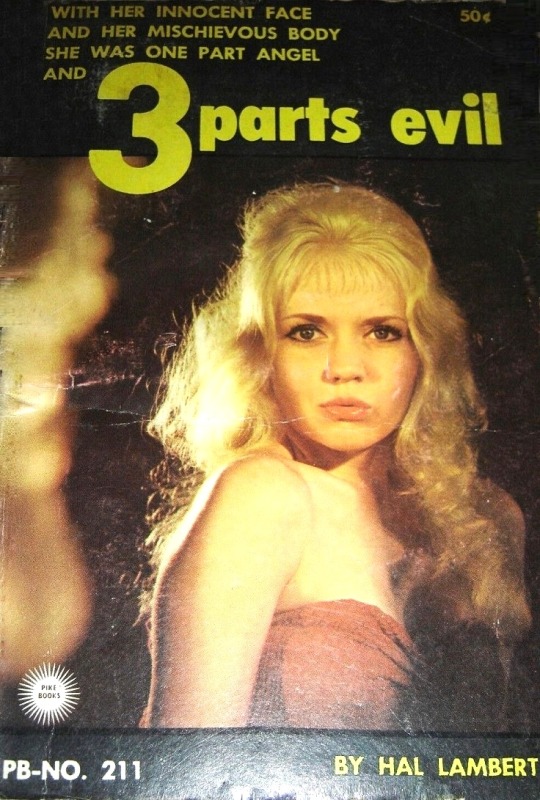

Hal Lambert - 3 Parts Evil - Pike - 1962

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

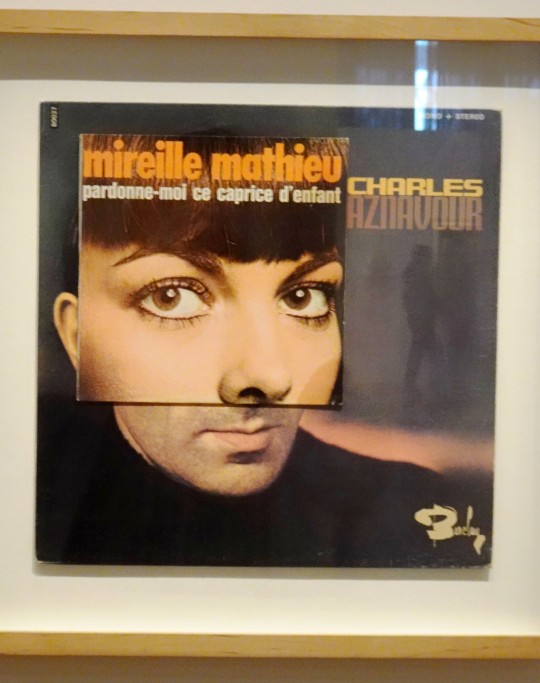

Marseille, il y a maintenant 3 semaines. Il y avait au MuCEM, une expo "Passions Partagées" sur la collection d'Yvon Lambert, face à certains objets du musée.

Christian Marclay : "Sound Sheet"

disque d'Or à IAM pour "L'Ecole du Micro d'Argent"

Christian Marclay - de série "Imaginary Records"

Matisse Mesnil : "Grappe de Raisin"

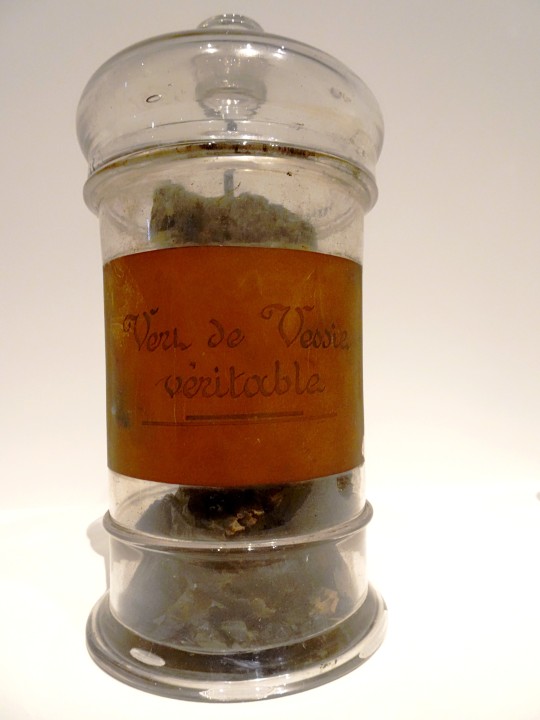

pigment vert de vessie (???!!) - A la Momie - Paris, 1850

autres pigments du même établissement

maquette de grue radoub du Havre - 1930

#marseille#MuCEM#passions partagées#art contemporain#yvon lambert#christian marclay#disque#cd#disque d'or#IAM#l'école du micro d'argent#mireille mathieu#charles aznavour#matisse mesnil#grappe#raisin#pigment#vert de vessie#soufre#bleu de berlin#chrome#grue#grue radoub#le havre#maquette

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

𝐉𝐞𝐚𝐧-𝐋𝐚𝐦𝐛𝐞𝐫𝐭 𝐓𝐚𝐥𝐥𝐢𝐞𝐧 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐋𝐚𝐳𝐚𝐫𝐞 𝐇𝐨𝐜𝐡𝐞

Description [translated]:

Private Jean de Dieu - Charles de Sombreuil - Tallien - General Hoche

I just found that illustration and catched my attention a lot because tallien and Hoche are in it!

A close up for tallien:

He looks the same like these two portraits here:

___________________________________

And a close up for Hoche:

also he Looks the same like his original portrait of him by the artist Jean Louis Laneuville here:

___________________________________

And here's a close up at the Soldat Jean de Dieu:

I couldn't find any information about him unfortunately because when I searched at his name I've found a similar name and it was for one of napoleon's marshals so idk .. and the name was Jean-de-Dieu Soult

___________________________________

And finally a close up at Charles de Sombreuil:

Ok now this is a very interesting one

To be honest with you all I don't know which Charles de Sombreuil are appearing here because there's two Charles de Sombreuil

The first one is: Charles François de Virot Marquis de Sombreuil [ 1723 - 1794] he got guillotined in paris And he was a lieutenant-general in the French Revolution

This is his portrait:

And the second one:Charles Eugène Gabriel de Virot de Sombreuil [ 1770 - 1795] he was shot in Vannes for his participation in the Quiberon expedition in an attempt to land emigrants in Brittany.

And he is the son of Charles Virot de Sombreuil

The story of Charles Virot de Sombreuil and his son gabriel Sombreuil is a long story and both had encountered with lazare Hoche and tallien in some way especially during the time of Quiberon expedition so this illustration maybe relate to something during that time .. I don't know to be honest.

Side note:[ the quality of this illustration is very high ].

#frev#french revolution#french history#jean lambert tallien#tallien#lazare hoche#i think hoche is a lil bit handsome tbh.#Charles Virot de Sombreuil

10 notes

·

View notes