#brissot

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Incorruptible Chap 3 pt 26

A lesson to Barnave: don't lead a Revolution if you weren't expecting *everyone* to be there with you.

#incorruptiblecomic#ah petion so optimistic so carefree lol#and brissot so serious#and camille so smug to have had the last say#these are the personalities I imagined they had ahaha#frev#french revolution#webcomic#comic#webtoon#robespierre#maximilien robespierre#brissot#petion#camille desmoulins#history comic#history#french history#historical fiction

81 notes

·

View notes

Text

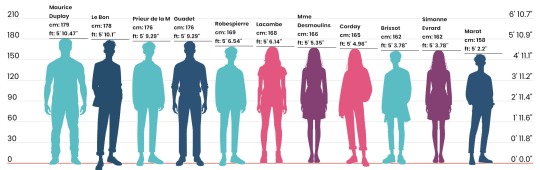

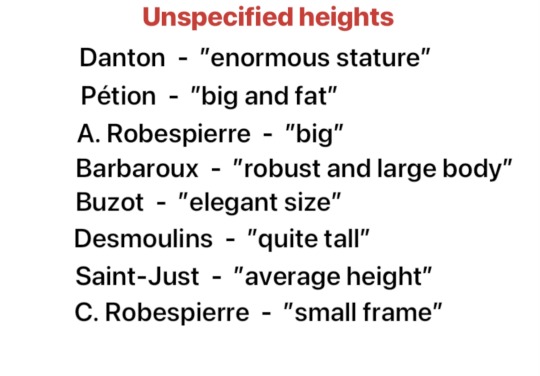

Frev appearance descriptions masterpost

Jean-Paul Marat — In Histoire de la Révolution française: 1789-1796 (1851) Nicolas Villiaumé pins down Marat’s height to four pieds and eight pouces (around 157 cm). This is a somewhat dubious claim considering Villiaumé was born 26 years after Marat’s death and therefore hardly could have measured him himself, but we do know he had had contacts with Marat’s sister Albertine, so maybe there’s still something to this. That Marat was short is however not something Villaumé is alone in claiming. Brissot wrote in his memoirs that he was ”the size of a sapajou,” the pamphlet Bordel patriotique (1791) claimed that he had ”such a sad face, such an unattractive height,” while John Moore in A Journal During a Residence in France, From the Beginning of August, to the Middle of December, 1792 (1793) documented that ”Marat is little man, of a cadaverous complexion, and a countenance exceedingly expressive of his disposition. […] The only artifice he uses in favour of his looks is that of wearing a round hat, so far pulled down before as to hide a great part of his countenance.” In Portrait de Marat (1793) Fabre d’Eglantine left the following very detailed description: ”Marat was short of stature, scarcely five feet high. He was nevertheless of a firm, thick-set figure, without being stout. His shoulders and chest were broad, the lower part of his body thin, thigh short and thick, legs bowed, and strong arms, which he employed with great vigor and grace. Upon a rather short neck he carried a head of a very pronounced character. He had a large and bony face, aquiline nose, flat and slightly depressed, the under part of the nose prominent; the mouth medium-sized and curled at one corner by a frequent contraction; the lips were thin, the forehead large, the eyes of a yellowish grey color, spirited, animated, piercing, clear, naturally soft and ever gracious and with a confident look; the eyebrows thin, the complexion thick and skin withered, chin unshaven, hair brown and neglected. He was accustomed to walk with head erect, straight and thrown back, with a measured stride that kept time with the movement of his hips. His ordinary carriage was with his two arms firmly crossed upon his chest. In speaking in society he always appeared much agitated, and almost invariably ended the expression of a sentiment by a movement of the foot, which he thrust rapidly forward, stamping it at the same time on the ground, and then rising on tiptoe, as though to lift his short stature to the height of his opinion. The tone of his voice was thin, sonorous, slightly hoarse, and of a ringing quality. A defect of the tongue rendered it difficult for him to pronounce clearly the letters c and l, to which he was accustomed to give the sound g. There was no other perceptible peculiarity except a rather heavy manner of utterance; but the beauty of his thought, the fullness of his eloquence, the simplicity of his elocution, and the point of his speeches absolutely effaced the maxillary heaviness. At the tribune, if he rose without obstacle or excitement, he stood with assurance and dignity, his right hand upon his hip, his left arm extended upon the desk in front of him, his head thrown back, turned toward his audience at three-quarters, and a little inclined toward his right shoulder. If on the contrary he had to vanquish at the tribune the shrieking of chicanery and bad faith or the despotism of the president, he awaited the reéstablishment of order in silence and resuming his speech with firmness, he adopted a bold attitude, his arms crossed diagonally upon his chest, his figure bent forward toward the left. His face and his look at such times acquired an almost sardonic character, which was not belied by the cynicism of his speech. He dressed in a careless manner: indeed, his negligence in this respect announced a complete neglect of the conventions of custom and of taste and, one might almost say, gave him an air of ressemblance.”

Albertine Marat — both Alphonse Ésquiros and François-Vincent Raspail who each interviewed Albertine in her old age, as well as Albertine’s obituary (1841) noted a striking similarity in apperance between her and her older brother. Esquiros added that she had ”two black and piercing eyes.” A neighbor of Albertine claimed in 1847 that she had ”the face of a man,” and that she had told her that ”my comrades were never jealous of me, I was too ugly for that” (cited in Marat et ses calomniateurs ou Réfutation de l’Histoire des Girondins de Lamartine (1847) by Constant Hilbe)

Simonne Evrard — An official minute from July 1792, written shortly after Marat’s death, affirmed the following: “Height: 1m, 62, brown hair and eyebrows, ordinary forehead, aquiline nose, brown eyes, large mouth, oval face.” The minute for her interrogation instead says: “grey eyes, average mouth.”Cited in this article by marat-jean-paul.org. When a neighbor was asked whether Simonne was pretty or not around two decades after her death in 1824, she responded that she was ”très-bien” and possessed ”an angelic sweetness” (cited in Marat et ses calomniateurs ou Réfutation de l’Histoire des Girondins de Lamartine (1847) by Constant Hilbe) while Joseph Souberbielle instead claimed that ”she was extremely plain and could never have had any good looks.”

Maximilien Robespierre — The hostile pampleth Vie secrette, politique et curieuse de M. J Maximilien Robespierre… released shortly after thermidor by L. Duperron, specifies Robespierre’s hight to have been ”five pieds and two or three pouces” (between 165 and 170 cm). He gets described as being ”of mediocre hight” by his former teacher Liévin-Bonaventure Proyart in 1795, ”a little below average height” by journalist Galart de Montjoie in 1795, ”of medium hight” by the former Convention deputy Antoine-Claire Thibaudeau in 1830 and ”of middling form” by his sister in 1834, but ”of small size” by John Moore in 1792 and Claude François Beaulieu in 1824. The 1792 pampleth Le véritable portrait de nos législateurs… wrote that Robespierre lacked ”an imposing physique, a body à la Danton,”supported by Joseph Fiévée who described him as ”small and frail” in 1836, and Louis Marie de La Révellière who said he was ”a physically puny man” in his memoirs published 1895. For his face, both François Guérin (on a note written below a sketch in 1791), Buzot in his Mémoires sur la Révolution française (written 1794), Germaine de Staël in her Considerations on the Principal Events of the French Revolution (1818), a foreign visitor by the name of Reichardt in 1792 (cited in Robespierre by J.M Thompson), Beaulieu and La Révellière-Lépeaux all agreed that he had a ”pale complexion.” Charlotte does instead describe it as ”delicate” and writes that Maximilien’s face ”breathed sweetness and goodwill, but it was not as regularly handsome as that of his brother,” while Proyart claims his apperance was ”entirely commonplace.” The foreigner Reichardt wrote Robespierre had ”flattened, almost crushed in, features,” something which Proyart agrees with, writing that his ”very flat features” consisted of ”a rather small head born on broad shoulders, a round face, an indifferent pock-marked complexion, a livid hue [and] a small round nose.” Thibaudeau writes Robespierre had a ”thin face and cold physiognomy, bilious complexion and false look,” Duperron that ”his colouring was livid, bilious; his eyes gloomy and dull,” something which Stanislas Fréron in Notes sur Robespierre (1794) also agrees with, claiming that ”Robespierre was choked with bile. His yellow eyes and complexion showed it.” His eyes were however green according to Merlin de Thionville and Guérin while Proyart insists they were ”pale blue and slightly sunken.” Etienne Dumont, who claimed to have talked to Robespierre twice, wrote in his Souvernirs sur Mirabeau et sur les deux premières assemblées législatives (1832) that ”he had a sinister appearance; he would not look people in the face, and blinked continually and painfully,” and Duperron too insists on ”a frequent flickering of the eyelids.” Both Fréron, Buzot, Merlin de Thionville, La Révellière, Louis Sébastien Mercier in his Le Nouveau Paris (1797) and Beffroy de Reigny in Dictionnaire néologique des hommes et des choses ou notice alphabétique des hommes de la Révolution, qui ont paru à l’Auteur les plus dignes d’attention… (1799) made the peculiar claim that Robespierre’s face was similar to that of a cat. Proyart, Beaulieu and Millingen all wrote that it was marked by smallpox scars, ”mediocretly” according to Proyart, ”deeply” according to the other two. Proyart also writes that Robespierre’s hair was light brown (châtain-blond). He is the only one to have described his hair color as far as I’m aware.

For his clothes, both Montjoie, Louis-Sébastien Mercier in 1801, Helen Maria Williams in 1795, Duperron, Millingen and Fiévée recall the fact that Robespierre wore glasses, the first two claiming he never appeared in public without them, Duperron that he ”almost always” wore them, and Millingen that they were green. Pierre Villiers, who claimed to have served as Robespierre’s secretary in 1790, recalled in Souvenirs d'un deporté (1802) that Robespierre ”was very frugal, fastidiously clean in his clothes, I could almost say in his one coat, which was was of a dark olive colour,” but also that ”He was very poor and had not even proper clothes,” and even had to borrow a suit from a friend at one point. Duperron records that ”[Robespierre’s] clothes were elegant, his hair always neat,” Millingen that ”his dress was careful, and I recollect that he wore a frill and ruffles, that seemed to me of valuable lace,”Charlotte that ”his dress was of an extreme cleanliness without fastidiousness,” Williams that he ”always appeared not only dressed with neatness, but with some degree of elegance, and while he called himself the leader of the sans-culottes, never adopted the costume of his band. His hideous countenance […] was decorated with hair carefully arranged and nicely powdered,” Fiévée that Robespierre in 1793 was ”almost alone in having retained the costume and hairstyle in use before the Revolution,” something which made him ressemble ”a tailor from the Ancien régime,” Thibadeau that ”he was neat in his clothes, and he had kept the powder when no one wore it anymore,” Germaine de Staël that ”he was the only person who wore powder in his hair; his clothes were neat, and his countenance nothing familiar,” Révellière writes that Robespierre’s voice was ”toneless, monotonous and harsh,” Beaulieu that it ”was sharp and shrill, almost always in tune with violence,” and Thinadeau that his ”tone” was ”dogmatic and imperious.”

Augustin Robespierre — described as ”big, well formed, and [with a] face full of nobility and beauty” in the memoirs of his sister Charlotte. Charles Nodier did in Souvenirs, épisodes et portraits pour servir à l'histoire de la Révolution et de l'Empire (1831) recall that Augustin had a ”pale and macerated physiognomy” and a quite monotonous voice.

Charlotte Robespierre — an anonymous doctor who claimed to have run into Charlotte in 1833, the year before her death, described her as ”very thin.” Jules Simon, who reported to have met her the following year, did him too describe her as ”a very thin woman, very upright in her small frame, dressed in the antique style with very puritanical cleanliness.”

Camille Desmoulins — described as ”quite tall, with good shoulders” in number 16 of the hostile journal Chronique du Manège (1790). Described as ugly by both said journal, the journal Journal Général de la Cour et de la Ville in 1791, his friend François Suleau in 1791, former teacher Proyart in 1795, Galart de Montjoie in 1796, Georges Duval in 1841, Amandine Rolland in 1864 (she does however add that it was ”with that witty and animated ugliness that pleases”) and even himself in 1793. Proyart describes his complexion as ”black,” Duval as ”bilious.” Both of them agree in calling his eyes ”sinister.” Duval also claims that Desmoulins’ physiognomy was similar to that of an ospray. Montjoie writes that Desmoulins had ”a difficult pronunciation, a hard voice, no oratorical talent,” Proyart that ”he spoke very heavily and stammered in speech” and Camille himself that he has ”difficulty in pronunciation” in a letter dated March 1787, and confesses ”the feebleness of my voice and my slight oratorical powers” in number 4 of the Vieux Cordelier. In his very last letter to his wife, dated April 1 1794, Desmoulins reveals that he wears glasses.

Lucile Desmoulins — The concierge at the Sainte-Pélagie prison documented the following when Lucille was brought before him on April 4 1794: ”height of five pieds and one and a half pouce (166 cm). Brown hair, eyebrows and eyes. Middle sized nose and mouth. Round face and chin. Ordinary front. A mark above the chin on the right.” Cited in Camille et Lucile Desmoulins: un rêve de république (2018). Described as beautiful by the journal Journal Général de la Cour et de la Ville in 1791 (it specifies her to be ”as pretty as her husband is ugly”), former Convention deputy Pierre Paganel in 1815, Louis Marie Prudhomme in 1830, Amandine Rolland in 1864 and Théodore de Lameth (memoirs published 1913).

Georges Danton — Described as having an ugly face by both Manon Roland in 1793, Vadier in 1794, the anonymous pamphlet Histoire, caractère de Maximilien Robespierre et anecdotes sur ses successeurs in 1794, Louis-Sébastien Mercier in 1797, Antoine Fantin-Desodoards in 1807, John Gideon Millingen in 1848, Élisabeth Duplay Lebas in the 1840s, the memoirs (1860) of François-René Chateaubriand (he specifies that Danton had ”the face of a gendarme mixed with that of a lustful and cruel prosecutor”) as well as the Mémoires de la Societé d’agriculture, commerce, sciences et arts du department de la Marse, Chalons-sur-Marne (1862). As reason for this ugliness, Millingen lifts his ”course, shaggy hair” (that apparently gave him the apperance of a ”wild beast”), the fact he was deeply marked with small-poxes, and that his eyes were unusually small (”and sparkling in surrounding darkness”), while Chateaubriand instead underlines that he was ”snub-nosed,” with ”windy nostrils [and] seamed flats.” Mercier writes that Danton’s face was ”hideously crushed.” The former Convention deputy Alexandre Rousselin (1774-1847) reported in his Danton — Fragment Historique that Danton developed a lip deformity after getting gored by a bull as a baby, had his nose crushed by another bull, got trampled in the face by a group of pigs and finally survived ”a very serious case of smallpoxes, accompanied by purpura.” In 1792, John Moore reported that ”Danton is not so tall, but much broader than Roland; his form is coarse and uncommonly robust,” while Vadier claims that Danton possessed a ”robust form, colossal eloquence,” the anonymous pamphlet that ”he was very strong, he said himself that he had athletic forms,” Desodoards that he ”held the nature of athletic and colossal forms,” Chateaubriand that he was ”a vandal in the size of Goth” (don’t know who he’s referring to), Pierre Paganel (in Essai historique et critique sur la révolution française: ses causes, ses résultats, avec les portraits des hommes les plus célèbres (1815)) that he was of an ”enormous stature,” while the pamphlet described him as a ”gigantic orator” whose voice ”shook the vaults of the hall.” René Levasseur in 1829, John Moore, Millingen, Paganel and Desodoards all agreed with this, the first four writing that Danton possessed a ”stentorian voice,” the latter that he had ”a very strong voice, without being sonorous or flexible.” In her memoirs (1834) Charlotte Robespierre claims that ”[Danton] did not at all conserve the dignity suited to the representative of a great people in his manners; his toilette was in disorder.”

Louis Antoine Saint-Just — In Saint-Just (1985) Bernard Vinot writes that Saint-Just’s childhood friend Augustin Lejeune recalled his “honest physiognomy,” and that his sister Louise would evoke her brother’s ”great beauty” for her grandchildren (I unfortunately can’t find the original sources here). The elderly Élisabeth Le Bas too stated that ”he was handsome, Saint-Just, with his pensive face, on which one saw the greatest energy, tempered by an air of indefinable gentleness and candor” (testimony found in Les Carnets de David d’Angers (1838-1855) by Pierre-Jean David d’Angers, cited in Veuve de Thermidor: le rôle et l'influence d'Élisabeth Duplay-Le Bas (1772-1859) sur la mémoire et l'historiographie de la Révolution française (2023) by Jolène Audrey Bureau, page 127). In Souvenirs de la révolution et de l’empire, Charles Nodier (who was twelve years old when he met Saint-Just…) agrees in calling him ”handsome,” but adds that he ”was far from offering this graceful combination of cute features with which we have seen it endowed by the euphemistic pencil of a lithograph,” had an ”ample and rather disproportionate chin,” that ”the arc of his eyebrows, instead of rounding into smooth and regular semi-circles, was closer to a straight line, and its interior angles, which were bushy and severe, merged into one another at the slightest serious thought that one saw pass on his forehead” and finally that ”his soft and fleshy lips indicated an almost invincible inclination to laziness and voluptuousness.” How would you know what his lips were like, Nodier. In Essai historique et critique sur la révolution française (1815) Pierre Paganel writes that Saint-Just had ”regular features and austere physiognomy.” He describes his complexion as ”bilious” while Nodier calls it ”pale and grayish, like that of most of the active men of the revolution.” Similar to Élisabeth’s description, Nodier writes that Saint-Just’s eyes were big and ”usually thoughtful,” while Paganel instead writes they were ”small and lively.” Saint-Just was of ”average height” according to Paganel, but ”of small stature” according to Nodier. According to Paganel, Saint-Just had a ”healthy body [and] proportions which expressed strength,” while Saint-Just’s colleague Levasseur de la Sarthe instead wrote in his memoirs that he was ”weak in body, to the point of fearing the whistling of bullets.” Finally, Paganel also gives the following details: ”large head, thick hair, disdainful gaze, strong but veiled voice, a general tinge of anxiety, the dark accent of concern and distrust, an extreme coldness in tone and manners.” In Lettre de Camille Desmoulins, député de Paris à la Convention, August général Dillon en prison aux Madelonettes (1793) Desmoulins jokingly writes that ”one can see by [Saint-Just’s] gait and bearing that he looks upon his own head as the corner-stone of the Revolution, for he carries it upon his shoulders with as much respect and as if it was the Sacred Host.” In Histoire de la Révolution française(1878), Jules Michelet claims that Élisabeth Le Bas had told him that this portrait, depicting Saint-Just as having ”a very low forehead, [with] the top of his head flattened, so that his hair, without being long, almost touched his eyes,” was similar to what he had looked like.

Jacques-Pierre Brissot — The following was documented after Brissot had been arrested at Moulins on June 10 1793 — ”height of five pieds (162 cm), a small amount of flat dark brown hair, eyebrows of the same color, high forehead and receding hairline, gray-brown, quite large and covered eyes, long and not very large nose, average mouth, long chin with a dimple, black beard, oval face narrow at the bottom” (cited in J.-P. Brissot mémoires (1754-1793); [suivi de] correspondance et papiers (1912)). In Journal During a Residence in France, from the Beginning of August, to the Middle of December, 1792 John Moore described Brissot as ”a little man, of an intelligent countenance, but of a weakly frame of body” and claimed that a person had told him that Brissot had told him that he is ”of so feeble a constitution” that he won’t be able to put up any resistance was someone try to assassinate him.

Jérôme Pétion — described as ”big and fat” (grand et gros) by Louis-Philippe in 1850 (cited in The Croker Papers: the Correspondence and Diaries of the late right honourable John Wilson Croker… (1885) volume 3, page 209). Manon Roland wrote in her memoirs that Pétion ”had nothing to regret physically; his size, his face, his gentleness, his urbanity, speak in his favor” as well as that he ”spoke fairly well,” a descriptions which Louis Marie Prudhomme partly agreed with, himself recording that Pétion ”had a proud countenance, a fairly handsome face, an affable look, a gentle eloquence, movements of talent and address; but his manners were composed, his eyes were dull, and he had something glistening in his features which repelled confidence” in Paris pendant le révolution (1789-1798) ou le nouveau Paris (1798). In Quelques notices pour l’histoire, et le récit de mes périls depuis le 31 mai 1793 (1794) Jean-Baptiste Louvet reported that, while on the run from the authorities after the insurrection of May 31, the less than forty years old Pétion already had a white hair and beard. This is confirmed by Frédéric Vaultier, who in Souvenirs de l'insurrection Normande, dite du Fédéralisme, en 1793 (1858) described Pétion during the same period as ”a good-looking man, with a calm and open physiognomy and beautiful white hair,” as well as by the examination of his mangled courpse on June 26 1794, which states he had ”grayish hair” (cited in Charlotte de Corday et les Girondins: pièces classées et annotées (1872) by Charles Vatel, volume 2, page 154.

François Buzot — according to the memoirs (1793) of Manon Roland, he had ”a noble figure and elegant size.” In the examination made of Buzot’s body after the suicide there is to read that he had black hair (cited in Charlotte de Corday et les Girondins: pièces classées et annotées (1872) by Charles Vatel, volume 2, page 153)

Charles Barbaroux — his son wrote in Jeunesse de Barbaroux (1822) that ”nature had richly endowed Barbaroux; a robust and large body; a charming, fine and witty physiognomy.” In 1867, François Laprade, who had witnessed Barbaroux’ execution as a thirteen year old, recollected that ”he was a brown man - that is to say he had brownish skin, black hair and beard, reclining figure” (cited in Charlotte de Corday et les Girondins: pièces classées et annotées, volume 3, page 728). Valazé’s daughter did in her old age too describe Barbaroux as very dark, with black hair, black beard and large black eyes. According to her, he was ”excessively beautiful,” with well-defined lips, beautiful teeth and fine, delicate features, so much so in fact that colleagues would often joke about his beauty. Cited in Ibid, volume 3, page 728.

Marguerite-Élie Guadet — According to his passport (cited in Charlotte de Corday et les Girondins: pièces classées et annotées, volume 3, page 672): ”height of 5 pieds, 5 pouces (176 cm) middle sized mouth, black hair and eyebrows, ordinary chin, blue eyes, big forehead, thin face, upturned nose.” According to Frédéric Vaultier’s Souvenirs de l'insurrection Normande, dite du Fédéralisme, en 1793(1858), ”Guadet was a man of fine height, meagre, brown, bilious complexion, black beard, most expressive face.”

Joseph Le Bon — his passport description (cited in Louis Jacob, Joseph Le Bon, (1932) by Louis Jacob, volume 1, page 63) gives the following information: ”Height of five pieds six pouces (178 cm), light brown hair and eyebrows, high forehead, average nose, blue eyes, medium-sized mouth, smallpox scars.”

Claire Lacombe — the concierge of the Sainte Pélagie documented the following about the imprisoned Lacombe: ”height of 5 pieds, 2 pouces (168 cm). Brown hair, eyebrows and eyes, medium nose, large mouth, round face and chin, plain forehead” (cited in Trois femmes de la Révolution : Olymps de Gouges, Théroigne de Méricourt, Rose Lacombe (1900) by Léopold Lacour)

Charlotte Corday — according to her passport, ”height of five pieds one pouce (165 cm), brown hair and eyebrows, gray eyes, high forehead, long nose, medium mouth, round, forked (fourchu) chin, oval face.” (cited in Dossiers du procès criminel de Charlotte Corday, devant le Tribunal révolutionnaire(1861) by Charles-Joseph Vatel, page 55)

Prieur de la Marne — a passport dated October 1 1793 gives the following details: ”age of 37 years, height of 5 pieds 5 pouces (176 cm), blondish brown hair and eyebrows, receding hairline, long nose, grey eyes, large mouth.”

Maurice Duplay — ”height of 5 pieds 6 pouces (179 cm), blondish brown hair and eyebrows, receding hairline, grey eyes, long, open nose, large mouth, round, full chin and face.” Descriptions given in 1795 and cited in Les deniers montagnards (1874) by Jules Claretie.

Jean Lambert Tallien — Both a spy report written in 1794 found among Robespierre’s papers and Mme de la Tour du Pin, a noblewoman who met Tallien in late 1793, describe Tallien’s hair as blonde. Mme de la Tour du Pin adds that said hair was curly and that he had a pretty face.

#might eventually reblog a part 2 i ran out of links for the moment#frev#french revolution#robespierre#georges danton#jean paul marat#albertine marat#simonne évrard#maximilien robespierre#augustin robespierre#camille desmoulins#desmoulins#lucile desmoulins#charlotte robespierre#charlotte corday#brissot#pétion#prieur de la marne#maurice duplay#jean lambert tallien#joseph lebon#charles barbaroux#françois buzot#saint-just#louis antoine de saint just#yes robespierre was taller than brissot this is no drill#i like this beauty and the beast thing camille and lucile seemed to have going tho…

269 notes

·

View notes

Note

Asking for a friend...

What, if anything, would you interpret into La Nouvelle Heloise being an 18th century man's favourite book?

No this is not about any history blorbo why do you ask...

Oh boy... I have only read some passages from it, because romance is not really my genre and I have a distinct feeling that the history which surrounds it is thousand times more interesting than the book itself.

That said, I'll combine all my useless JJ knowledge to give the best possible answer I can!

First of all, it cannot be overstated how massively popular it was when it came out, so it's actually kind of a mainstream choice (some people apparently paid an hourly fee just to rent the damn book)! It mainly struck a cord with women readers, but plenty of men read it as well. And cried over it (one guy even claimed he cried so hard it cured his cold somehow).

I know this will probably sound like an insane comparison, but I kind of think of it as an 18th-century equivalent of Fifty Shades? Both in terms of popularity and it being rather risqué, just less overtly so. For instance, there is definitely a Ménage à trois element to the story that will be very familiar to any poor, unfortunate reader of Rousseau's own Confessions...

My diagnosis? You reached for LNH if you wanted to read something that was actually quite raunchy, but which was so carefully wrapped in sentimental pathos with JJ's weird moral lessons sprinkled on top that it gave you plenty of plausible deniability (unlike, let's say, Bijoux or something more overt).

Definitely not a story about some horny Swiss idiots making their lives needlessly complicated. You could practically feel the virtue radiating from every page and penetrating your very soul! Ah, what bliss!

tl;dr: 1. a pretty mainstream choice for the time 2. as much as it pains me to say it JJ is unfortunately a damn good writer capable of throwing you on an emotional roller-coaster in just a few pages - so a part of me gets the appeal? 3. a sort-of-smut for people who would likely have hang-ups about reading actual smut or at least admitting to it (this would likely apply to a lot of people in the 1700s)

If you haven't read the chapter Readers Respond to Rousseau: The Fabrication of Romantic Sensitivity in Robert Darnton's The Great Cat Massacre please please do, it's amazing, it's funny, it's one of the best things I've read this year! It also involves some primary sources, most of which are - I'm sorry to say - fan mail to JJ.

On the other hand, if you're a man who's read Confessions six times, there's a high chance you might just be a bit of a sub... <- no, you appreciate the truth and virtue above all, obviously!

#asks#had way too much fun with this I should probably read the whole thing properly#the new heloise#julie#18th century#1700s#jean jacques rousseau#rousseau#tw: jj#history#literature#robert darnton#book history#french history#frev#brissot#Jacques Pierre Brissot#french literature

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

Louvet and Pétion on 10th March

„I've rushed to Pétion, where some of my friends gathered to find them peacefully discussing the decrees to be enacted weeks later. God knows what effort it took from me to release them from that safety! Finally I achieved that none of them would go to the already started session and that we would meet an hour after in a house where conspirators couldn't guess our presence.

Then I went promptly to the session. There I found Kervelégan, a deputy from Finistère. That brave man ran to the Faubourg Marceau to warn a Breton bataillon, which, fortunately, had been standing in Paris for several days. The bataillon remained under arms all night, ready to march to our aids at first request or ringing of a tocsin.

I was moving from one door to another, warning Valazé, Buzot, Barbaroux, Salles and many others. Brissot had gone to warn the ministers. The minister of war, brave and unfortunate Beurnonville had climbed over his garden fence and joined some friends of him in their patrol. After two hours of running in the dark night amidst my, so to say, assassins I returned to the place we had appointed. Pétion was absent. He would have placed himself in a great danger if he had stayed at home.

I'd returned for him, and his answer will paint him well. While I was urging him to follow me, he came to the window and opened it. Then, looking at the sky, he said: „It's raining. Nothing will happen.“ No matter what I said, he persisted in staying.“

From Memoires de Louvet de Couvray, 1823 ed., p.73-74

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

My guilty pleasure is drawing pissed off Robespierre. Also a clueless Brissot

Fight! Fight! Fight! Baiser

#Maximilien Robespierre#brissot#robespierre#Jacques Pierre brissot#french revolution#frev#art#my art

294 notes

·

View notes

Text

its so brissover (me when the war i campaigned for is going not good and the populace is angry about my lack of judgment endangering them and i am going to be arrested so bad)

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

@aedesluminis's recent post sent me down a "i Giacobini" rabbit hole (thank you!)

So here's some pictures of the theatre cast (1956/57), and you can look at the rest at the archives of the Piccolo Teatro di Milano (here).

Camille and Lucile (Sergio Fantoni and Virna Lisi). Don't be deceived by his leading man-like good looks, Camille is hilarious and has the best lines.

Manon Roland (Elsa de Giorgi).

Brissot 😭 (Aldo Allegranza); on top of that he speaks in a somewhat regional accent, pronouncing his "s"s as "z"s. The ruthless Girondins bashing relates to the contemporary political scene in Italy which I obviously know nothing about.

Charlotte Robespierre (Ornella Vanoni), who appears for all of one scene.

The best for last: Billaud-Varennes and Fouché (Franco Graziosi and Ottavio Fanfani).

#frev#i giacobini#the jacobins#manon roland#fouché#brissot#i had put in descriptions of the photographs but they just don't show up??#i'm lousy at tumblr evidently

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

About the slave rebellion in Saint-Domingue

Dans la séance du 30 novembre 1791 à l'assemblée législative, les délégués de Saint-Domingue présentèrent les éléments les plus "spectaculaires" qui devinrent ensuite les symboles de l'inhumanité des révoltés.[...] Fantasmes morbides ou réalités ? Il est impossible de le savoir, mais les détails de l'enfant empalé ou de l'homme scié vivant ne figuraient pas dans les relations des témoins de première main de la destruction de l'habitation Gallifet où ces faits auraient été commis. Ces images d'horreur devinrent pourtant des emblèmes de violence "africaine" bien au-delà de la colonie de Saint Domingue. Elles [...] se répandirent même dans les milieux révolutionnaires comme en février 1793, quand Camille Desmoulins les cita comme pièces à charge dans son Jean-Pierre Brissot démasqué. Tous les révolutionnaires n'étaient toutefois pas dupes des discours sur les horreurs "africains". Garran Coulon répondit en février 1792.[...] Il accusait en retour les colons contre les libres de couleur d'avoir caché la repression féroce des colons contre les libres de couleurs."

La révolution française et les colonies, BELISSA Marc

#frev#camille desmoulins#classic colonial reaction#making rebels looking like monsters#brissot#and Camille...#Camille...sigh#using this to attack Brissot because he was a member of 'La société des amis des noirs'#own goal Camille

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

I apologise for the delay (I have been rather caught up in work), but here we are with another Hamilton FRev rewrite!

Here is Washington on Your Side! Taking a break from Camille being dramatic, we are moving to the equally dramatic people who want to kill him

Brissot: It must be nice, it must be nice

To have Robespierre on your side

It must be nice, it must be nice

To have Robespierre on your side

Every action has an equal opposite reaction

Thanks to Desmoulins, the convention has fractured into factions

Try not to crack under the stress, we're breaking down like fractions

We smack each other in the press, and we don't print retractions

SJ: I get no satisfaction witnessing his fits of passion

The way he primps and preens and dresses like the pits of fashion

Our poorest citizens, our farmers, live ration to ration

As aristocrats rob 'em blind in search of chips to cash in

This prick is asking for someone to bring him to task

Somebody give me some dirt on his vacuous mask

So we can, at last, unmask him

I'll pull the trigger on him, someone load the gun and cock it

While we were all watching, he got Robespierre in his pocket

Brissot: Look back at the Bill of Rights (Which I wrote!)

The ink hasn't dried

It must be nice, it must be nice

To have Robespierre on your side

If we don't stop it, we aid and abet it

I have to resign

Somebody has to stand up for the provinces

Well, somebody has to stand up to his mouth

If there's a fire you're trying to douse

You can't put it out from inside the house

SJ: Oh! This ganymede isn't somebody we chose

Oh! This journalist keeping us all on our toes

Oh! Let's show these cordeliers what they're up against

Oh! Parisien motherfucking Montagnard-Republicans

We won't be invisible

We won't be denied

Still, it must be nice, it must be nice

To have Robspierre on your side

#Hamilton ReWrite: FRev Edition#french revolution#hamilton the musical#maximilien robespierre#brissot#louis antoine de saint just#camille desmoulins#frev

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Incorruptible Chap 3 pt 23

On the second page, we have some deputies of the future National Convention- the first government made up of deputies voted for via universal male suffrage: Marat, Brissot, Danton, Saint-Just and Belley.

#incorruptiblecomic#obviously not everyone on the 2nd page are ppl that Robespierre WANTED in the national convention#but they show the mixture of people that will make up a much more democratic government that Robespierre is aspiring to in his speech here#And ofc Brissot danton n SJ are little hints at future important ppl in Robespierres life#I guess Brissot first in line with his time in the legislative assembly n his war mongering ohoho#frev#french revolution#robespierre#maximilien robespierre#jean paul marat#marat#brissot#jacques pierre brissot#georges danton#danton#louis antoine saint just#saint just#jean-baptiste belley#belley#revolution francais#comic update#frev art

121 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do we know the favorite books that the French revolution figures liked to read? (It could be anyone, Robespierre or Saint just or Louis xvi it doesn't matter).

Much like this old ask about revolutionaries’ favorite dishes, I can’t say I know of any instance of someone exclaiming: ”this is 100% my favorite book,” but at tops people mentioning books that they thought were good or bad:

In his memoirs, Brissot writes he’s picking up Rousseau’s Confessions for the sixth time, so I guess that could qualify as a favorite book? send help

We have this list of books seized at Robespierre’s place after his death.

According to the memoirs of Élisabeth Duplay, Robespierre would read ”the works of Corneille, Voltaire and Rousseau” for her family in the evenings.

In a short biography over Desmoulins written in 1834, Marcellin Matton claims his favorite book was René Aubert de Vertot’s Histoire des révolutions arrivées dans le gouvernement de la République romaine (1719), of which he always carried a copy. Matton is an infamous romanticizer it’s from him we have the stupid leaf myth for example, but I’m willing to give him some leeway here since he could have obtained the information from Camille’s mother-in-law and sister-in-law, who were his friends:

In one of his first classes, he received Vertot's Révolutions romaines as a prize. Reading this work transported him with admiration; in the future, he always had a volume in his pocket. It was for him an indispensable companion, it was his vade mecum. He used or lost at least twenty volumes. It is perhaps to this excellent work and to the particular work that he did on the discourses of Cicero and especially on his Philippics, that we owe the lively and sharp style which distinguishes all the writings coming from the pen of Camille .

Desmoulins was however less fond of Rousseau’s Confessions, in number 55 (December 1790) of Révolutions de France et de Brabant he admits that he abandoned the book after getting infuriated by it:

Not that I idolize J.J. as I did in the past, since I saw in his Confessions that he had become an aristocrat in his old age. How far he was from looking at an Alexander with the pride of this Cynic, to whom he is compared, and how painfully I saw that he united the opposite faults of Diogenes and Arisippus! It is a pleasant thing to hear the author of the Social Contract protest in his Confessions about the simplicity of the commerce of such great lords (M. and Madame de Luxembourg) he cries with joy, he wants to kiss the feet of this good marshal, because he wanted to accompany one of his friends, an office clerk, for a walk. Is there anything smaller, more ridiculous? I received, he says elsewhere, the greatest honor that a man can receive, the visit of the Prince de Conti, (an honor that Rousseau shared with all the girls of the Palais-Royal.) At this point I tossed away the book out of spite, and I admit, that I had to reread the speech on equality of conditions, and Julie's novel, in order to not hate the philosopher of Geneva, like Durosoy and Mallet du Pan; for the same principles, in the mouth of such a great man, are more condemnable and worthy of aversion than in the mouths of our two gazetteers, whom God created poor in spirit, and predestined as such to the kingdom of heaven.

In a diary kept over the summer of 1788, Lucile Desmoulins mentions reading L’Âge d’Or (1782) by Sylvain Maréchal (of which she also copied two verses, Le Trésor and Le contrat de mariage devant la nature, in a notebook the year earlier), Les Idylles et poèmes champêtres (1762) by Salomon Gessner, L’Hymne au soleil, suivi de plusieurs morceaux du même genre qui n’ont point encore paru (1782) by Abbé de Reyrac (where she wrote down the verse La Gelée d’avril), Nouvelles lettres anglaises, ou Histoire du Chevalier Grandisson (1754) by Samuel Richardson and Les Noces patriarchales, poëme en prose en cinq chants (1777) by Robert Martin Lesuire.

In his memoirs, Buzot mentions enjoying the works of Rousseau and Plutarch:

With what charms I still remember this happy period of my life which can no longer return, when, during the day, I silently roamed the mountains and woods of the city where I was born, reading with delight some works of Plutarch or of Rousseau, or recalling to my memory the most precious features of their morality and their philosophy. Sometimes, sitting on the flowering grass, in the shade of some thick trees, I indulged, in a sweet melancholy, in the memories of the sorrows and the pleasures which had in turn agitated the first days of my life. Often the cherished works of these two good men had occupied or maintained my vigils with a friend of my age whom death took from me at thirty, and whose memory, always dear and respected, has preserved from many errors!

Wow any chance you can sound even more like an 18th century man stereotype, Buzot?

…and that’s basically all I can come up with for the moment. But add on if you know anything more! @louis-antoine-leon-saint-just @lazarecarnot maybe you would like to share your favorite books with us if you have any?

#frev#ask#robespierre#desmoulins#lucile desmoulins#buzot#brissot#camille actually being the only sane person

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

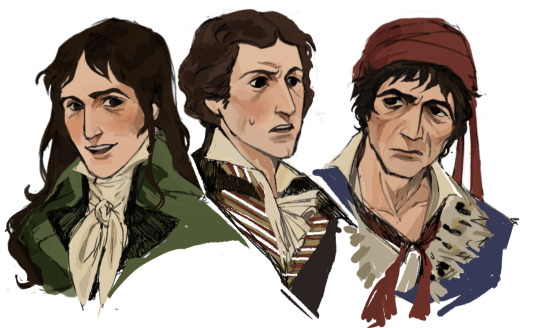

three very opinionated guys. ugh I have drawn our mother Marat so much that i can't even draw twinks these days

#I have to practice coloring because i always manage to make it look very grey#art is hard but I'll get there#töherryksiä ynnä muuta#jean paul marat#camille desmoulins#jacques pierre brissot#frev#what a month!!... haven't had time to draw#ill have time to fix my sleeping schedule anoyher time

426 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sept. 27th 1790

This is the moment in which patriotic writers ought to denounce by name those corrupt members who, by their hypocrisy, and their maneuvers, deceive the hope, and betray the interest of their constituents. They ought to publish without reserve what you say of the General. What purpose does the liberty of the press answer, if the remedies which it affords against the evils that threaten us be not made use of? Brissot seems to be asleep; Loustallot is dead, and we have lamented the loss of him with many tears; Desmoulins will have occasion to resume his employment of procurator-general of the lantern.

The Rolands and Brissot were already friends so it’s interesting she directly insults him here, especially funny comparing him to Camille.

Also I changed the punctuation based on the original French since this English translation made Roland look like a Camille fangirl.

Almost out of nowhere Roland spends 3 pages describing her body, face, accomplishments etc. only for it to be lead up to Camille slander lol

#procurator-general of the lantern is a sick title#besides this she barely mentions him in her letters#they probably saw each other but I believe they never really met#camille#frev#madame roland#brissot

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

he’s a 10 but he’s best friends with that war-mongering rat bastard who packed the king’s ministry with his own lackeys

25 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The super stylish sci-fi sketches and artworks of Thomas Brissot - https://www.this-is-cool.co.uk/the-sci-fi-sketches-and-artworks-of-thomas-brissot/

#Thomas Brissot#sci-fi art#sci-fi artist#science fiction art#science fiction artist#digital art#digital artist#digital sketches#sci-fi sketches#concept art#concept artist#this-is-cool#scififantasyhorror#space art

837 notes

·

View notes