#lucile desmoulins

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

happy birthday camille desmoulins 💚💚

ft @labellealliance’s pinching widget

#frev#french revolution#camille desmoulins#lucile desmoulins#happy birthday king#hand me the damn dryer#louis antoine saint just#saint just

226 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lucile tries to find Robespierre a wife

A very silly Saintspierre comic inspired by some comments made by @octavodecimo @misscalming and @revolutionary-plastic-flower on my last comic page (thank you hehe) putting under cut cos its quite long.

#frev#french revolution#incorruptiblecomic#robespierre#maximilien robespierre#louis antoine saint just#saint just#saintspierre#lucile desmoulins#camille desmoulins#I stayed up too late just to draw this#just needed to draw it lol

280 notes

·

View notes

Text

Camille couldn’t take a hint, could he?

#french revolution#frev#frev art#my art#frevblr#maximilien robespierre#camille desmoulins#antoine saint just#lucile desmoulins#robesmoulins#saintspierre#doomed yaoi#its canon#chase him max#he chose lucile#octavodecimo’s art

187 notes

·

View notes

Text

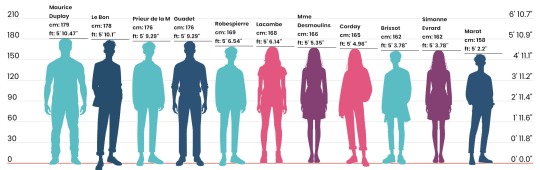

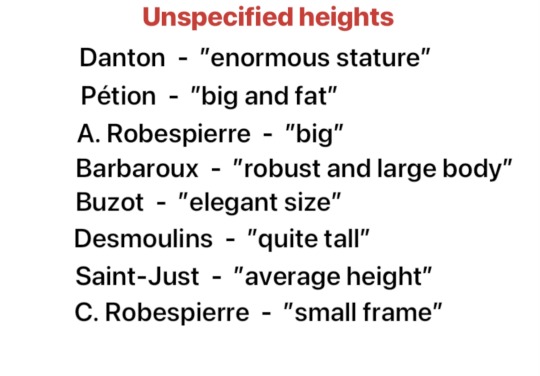

Frev appearance descriptions masterpost

Jean-Paul Marat — In Histoire de la Révolution française: 1789-1796 (1851) Nicolas Villiaumé pins down Marat’s height to four pieds and eight pouces (around 157 cm). This is a somewhat dubious claim considering Villiaumé was born 26 years after Marat’s death and therefore hardly could have measured him himself, but we do know he had had contacts with Marat’s sister Albertine, so maybe there’s still something to this. That Marat was short is however not something Villaumé is alone in claiming. Brissot wrote in his memoirs that he was ”the size of a sapajou,” the pamphlet Bordel patriotique (1791) claimed that he had ”such a sad face, such an unattractive height,” while John Moore in A Journal During a Residence in France, From the Beginning of August, to the Middle of December, 1792 (1793) documented that ”Marat is little man, of a cadaverous complexion, and a countenance exceedingly expressive of his disposition. […] The only artifice he uses in favour of his looks is that of wearing a round hat, so far pulled down before as to hide a great part of his countenance.” In Portrait de Marat (1793) Fabre d’Eglantine left the following very detailed description: ”Marat was short of stature, scarcely five feet high. He was nevertheless of a firm, thick-set figure, without being stout. His shoulders and chest were broad, the lower part of his body thin, thigh short and thick, legs bowed, and strong arms, which he employed with great vigor and grace. Upon a rather short neck he carried a head of a very pronounced character. He had a large and bony face, aquiline nose, flat and slightly depressed, the under part of the nose prominent; the mouth medium-sized and curled at one corner by a frequent contraction; the lips were thin, the forehead large, the eyes of a yellowish grey color, spirited, animated, piercing, clear, naturally soft and ever gracious and with a confident look; the eyebrows thin, the complexion thick and skin withered, chin unshaven, hair brown and neglected. He was accustomed to walk with head erect, straight and thrown back, with a measured stride that kept time with the movement of his hips. His ordinary carriage was with his two arms firmly crossed upon his chest. In speaking in society he always appeared much agitated, and almost invariably ended the expression of a sentiment by a movement of the foot, which he thrust rapidly forward, stamping it at the same time on the ground, and then rising on tiptoe, as though to lift his short stature to the height of his opinion. The tone of his voice was thin, sonorous, slightly hoarse, and of a ringing quality. A defect of the tongue rendered it difficult for him to pronounce clearly the letters c and l, to which he was accustomed to give the sound g. There was no other perceptible peculiarity except a rather heavy manner of utterance; but the beauty of his thought, the fullness of his eloquence, the simplicity of his elocution, and the point of his speeches absolutely effaced the maxillary heaviness. At the tribune, if he rose without obstacle or excitement, he stood with assurance and dignity, his right hand upon his hip, his left arm extended upon the desk in front of him, his head thrown back, turned toward his audience at three-quarters, and a little inclined toward his right shoulder. If on the contrary he had to vanquish at the tribune the shrieking of chicanery and bad faith or the despotism of the president, he awaited the reéstablishment of order in silence and resuming his speech with firmness, he adopted a bold attitude, his arms crossed diagonally upon his chest, his figure bent forward toward the left. His face and his look at such times acquired an almost sardonic character, which was not belied by the cynicism of his speech. He dressed in a careless manner: indeed, his negligence in this respect announced a complete neglect of the conventions of custom and of taste and, one might almost say, gave him an air of ressemblance.”

Albertine Marat — both Alphonse Ésquiros and François-Vincent Raspail who each interviewed Albertine in her old age, as well as Albertine’s obituary (1841) noted a striking similarity in apperance between her and her older brother. Esquiros added that she had ”two black and piercing eyes.” A neighbor of Albertine claimed in 1847 that she had ”the face of a man,” and that she had told her that ”my comrades were never jealous of me, I was too ugly for that” (cited in Marat et ses calomniateurs ou Réfutation de l’Histoire des Girondins de Lamartine (1847) by Constant Hilbe)

Simonne Evrard — An official minute from July 1792, written shortly after Marat’s death, affirmed the following: “Height: 1m, 62, brown hair and eyebrows, ordinary forehead, aquiline nose, brown eyes, large mouth, oval face.” The minute for her interrogation instead says: “grey eyes, average mouth.”Cited in this article by marat-jean-paul.org. When a neighbor was asked whether Simonne was pretty or not around two decades after her death in 1824, she responded that she was ”très-bien” and possessed ”an angelic sweetness” (cited in Marat et ses calomniateurs ou Réfutation de l’Histoire des Girondins de Lamartine (1847) by Constant Hilbe) while Joseph Souberbielle instead claimed that ”she was extremely plain and could never have had any good looks.”

Maximilien Robespierre — The hostile pampleth Vie secrette, politique et curieuse de M. J Maximilien Robespierre… released shortly after thermidor by L. Duperron, specifies Robespierre’s hight to have been ”five pieds and two or three pouces” (between 165 and 170 cm). He gets described as being ”of mediocre hight” by his former teacher Liévin-Bonaventure Proyart in 1795, ”a little below average height” by journalist Galart de Montjoie in 1795, ”of medium hight” by the former Convention deputy Antoine-Claire Thibaudeau in 1830 and ”of middling form” by his sister in 1834, but ”of small size” by John Moore in 1792 and Claude François Beaulieu in 1824. The 1792 pampleth Le véritable portrait de nos législateurs… wrote that Robespierre lacked ”an imposing physique, a body à la Danton,”supported by Joseph Fiévée who described him as ”small and frail” in 1836, and Louis Marie de La Révellière who said he was ”a physically puny man” in his memoirs published 1895. For his face, both François Guérin (on a note written below a sketch in 1791), Buzot in his Mémoires sur la Révolution française (written 1794), Germaine de Staël in her Considerations on the Principal Events of the French Revolution (1818), a foreign visitor by the name of Reichardt in 1792 (cited in Robespierre by J.M Thompson), Beaulieu and La Révellière-Lépeaux all agreed that he had a ”pale complexion.” Charlotte does instead describe it as ”delicate” and writes that Maximilien’s face ”breathed sweetness and goodwill, but it was not as regularly handsome as that of his brother,” while Proyart claims his apperance was ”entirely commonplace.” The foreigner Reichardt wrote Robespierre had ”flattened, almost crushed in, features,” something which Proyart agrees with, writing that his ”very flat features” consisted of ”a rather small head born on broad shoulders, a round face, an indifferent pock-marked complexion, a livid hue [and] a small round nose.” Thibaudeau writes Robespierre had a ”thin face and cold physiognomy, bilious complexion and false look,” Duperron that ”his colouring was livid, bilious; his eyes gloomy and dull,” something which Stanislas Fréron in Notes sur Robespierre (1794) also agrees with, claiming that ”Robespierre was choked with bile. His yellow eyes and complexion showed it.” His eyes were however green according to Merlin de Thionville and Guérin while Proyart insists they were ”pale blue and slightly sunken.” Etienne Dumont, who claimed to have talked to Robespierre twice, wrote in his Souvernirs sur Mirabeau et sur les deux premières assemblées législatives (1832) that ”he had a sinister appearance; he would not look people in the face, and blinked continually and painfully,” and Duperron too insists on ”a frequent flickering of the eyelids.” Both Fréron, Buzot, Merlin de Thionville, La Révellière, Louis Sébastien Mercier in his Le Nouveau Paris (1797) and Beffroy de Reigny in Dictionnaire néologique des hommes et des choses ou notice alphabétique des hommes de la Révolution, qui ont paru à l’Auteur les plus dignes d’attention… (1799) made the peculiar claim that Robespierre’s face was similar to that of a cat. Proyart, Beaulieu and Millingen all wrote that it was marked by smallpox scars, ”mediocretly” according to Proyart, ”deeply” according to the other two. Proyart also writes that Robespierre’s hair was light brown (châtain-blond). He is the only one to have described his hair color as far as I’m aware.

For his clothes, both Montjoie, Louis-Sébastien Mercier in 1801, Helen Maria Williams in 1795, Duperron, Millingen and Fiévée recall the fact that Robespierre wore glasses, the first two claiming he never appeared in public without them, Duperron that he ”almost always” wore them, and Millingen that they were green. Pierre Villiers, who claimed to have served as Robespierre’s secretary in 1790, recalled in Souvenirs d'un deporté (1802) that Robespierre ”was very frugal, fastidiously clean in his clothes, I could almost say in his one coat, which was was of a dark olive colour,” but also that ”He was very poor and had not even proper clothes,” and even had to borrow a suit from a friend at one point. Duperron records that ”[Robespierre’s] clothes were elegant, his hair always neat,” Millingen that ”his dress was careful, and I recollect that he wore a frill and ruffles, that seemed to me of valuable lace,”Charlotte that ”his dress was of an extreme cleanliness without fastidiousness,” Williams that he ”always appeared not only dressed with neatness, but with some degree of elegance, and while he called himself the leader of the sans-culottes, never adopted the costume of his band. His hideous countenance […] was decorated with hair carefully arranged and nicely powdered,” Fiévée that Robespierre in 1793 was ”almost alone in having retained the costume and hairstyle in use before the Revolution,” something which made him ressemble ”a tailor from the Ancien régime,” Thibadeau that ”he was neat in his clothes, and he had kept the powder when no one wore it anymore,” Germaine de Staël that ”he was the only person who wore powder in his hair; his clothes were neat, and his countenance nothing familiar,” Révellière writes that Robespierre’s voice was ”toneless, monotonous and harsh,” Beaulieu that it ”was sharp and shrill, almost always in tune with violence,” and Thinadeau that his ”tone” was ”dogmatic and imperious.”

Augustin Robespierre — described as ”big, well formed, and [with a] face full of nobility and beauty” in the memoirs of his sister Charlotte. Charles Nodier did in Souvenirs, épisodes et portraits pour servir à l'histoire de la Révolution et de l'Empire (1831) recall that Augustin had a ”pale and macerated physiognomy” and a quite monotonous voice.

Charlotte Robespierre — an anonymous doctor who claimed to have run into Charlotte in 1833, the year before her death, described her as ”very thin.” Jules Simon, who reported to have met her the following year, did him too describe her as ”a very thin woman, very upright in her small frame, dressed in the antique style with very puritanical cleanliness.”

Camille Desmoulins — described as ”quite tall, with good shoulders” in number 16 of the hostile journal Chronique du Manège (1790). Described as ugly by both said journal, the journal Journal Général de la Cour et de la Ville in 1791, his friend François Suleau in 1791, former teacher Proyart in 1795, Galart de Montjoie in 1796, Georges Duval in 1841, Amandine Rolland in 1864 (she does however add that it was ”with that witty and animated ugliness that pleases”) and even himself in 1793. Proyart describes his complexion as ”black,” Duval as ”bilious.” Both of them agree in calling his eyes ”sinister.” Duval also claims that Desmoulins’ physiognomy was similar to that of an ospray. Montjoie writes that Desmoulins had ”a difficult pronunciation, a hard voice, no oratorical talent,” Proyart that ”he spoke very heavily and stammered in speech” and Camille himself that he has ”difficulty in pronunciation” in a letter dated March 1787, and confesses ”the feebleness of my voice and my slight oratorical powers” in number 4 of the Vieux Cordelier. In his very last letter to his wife, dated April 1 1794, Desmoulins reveals that he wears glasses.

Lucile Desmoulins — The concierge at the Sainte-Pélagie prison documented the following when Lucille was brought before him on April 4 1794: ”height of five pieds and one and a half pouce (166 cm). Brown hair, eyebrows and eyes. Middle sized nose and mouth. Round face and chin. Ordinary front. A mark above the chin on the right.” Cited in Camille et Lucile Desmoulins: un rêve de république (2018). Described as beautiful by the journal Journal Général de la Cour et de la Ville in 1791 (it specifies her to be ”as pretty as her husband is ugly”), former Convention deputy Pierre Paganel in 1815, Louis Marie Prudhomme in 1830, Amandine Rolland in 1864 and Théodore de Lameth (memoirs published 1913).

Georges Danton — Described as having an ugly face by both Manon Roland in 1793, Vadier in 1794, the anonymous pamphlet Histoire, caractère de Maximilien Robespierre et anecdotes sur ses successeurs in 1794, Louis-Sébastien Mercier in 1797, Antoine Fantin-Desodoards in 1807, John Gideon Millingen in 1848, Élisabeth Duplay Lebas in the 1840s, the memoirs (1860) of François-René Chateaubriand (he specifies that Danton had ”the face of a gendarme mixed with that of a lustful and cruel prosecutor”) as well as the Mémoires de la Societé d’agriculture, commerce, sciences et arts du department de la Marse, Chalons-sur-Marne (1862). As reason for this ugliness, Millingen lifts his ”course, shaggy hair” (that apparently gave him the apperance of a ”wild beast”), the fact he was deeply marked with small-poxes, and that his eyes were unusually small (”and sparkling in surrounding darkness”), while Chateaubriand instead underlines that he was ”snub-nosed,” with ”windy nostrils [and] seamed flats.” Mercier writes that Danton’s face was ”hideously crushed.” The former Convention deputy Alexandre Rousselin (1774-1847) reported in his Danton — Fragment Historique that Danton developed a lip deformity after getting gored by a bull as a baby, had his nose crushed by another bull, got trampled in the face by a group of pigs and finally survived ”a very serious case of smallpoxes, accompanied by purpura.” In 1792, John Moore reported that ”Danton is not so tall, but much broader than Roland; his form is coarse and uncommonly robust,” while Vadier claims that Danton possessed a ”robust form, colossal eloquence,” the anonymous pamphlet that ”he was very strong, he said himself that he had athletic forms,” Desodoards that he ”held the nature of athletic and colossal forms,” Chateaubriand that he was ”a vandal in the size of Goth” (don’t know who he’s referring to), Pierre Paganel (in Essai historique et critique sur la révolution française: ses causes, ses résultats, avec les portraits des hommes les plus célèbres (1815)) that he was of an ”enormous stature,” while the pamphlet described him as a ”gigantic orator” whose voice ”shook the vaults of the hall.” René Levasseur in 1829, John Moore, Millingen, Paganel and Desodoards all agreed with this, the first four writing that Danton possessed a ”stentorian voice,” the latter that he had ”a very strong voice, without being sonorous or flexible.” In her memoirs (1834) Charlotte Robespierre claims that ”[Danton] did not at all conserve the dignity suited to the representative of a great people in his manners; his toilette was in disorder.”

Louis Antoine Saint-Just — In Saint-Just (1985) Bernard Vinot writes that Saint-Just’s childhood friend Augustin Lejeune recalled his “honest physiognomy,” and that his sister Louise would evoke her brother’s ”great beauty” for her grandchildren (I unfortunately can’t find the original sources here). The elderly Élisabeth Le Bas too stated that ”he was handsome, Saint-Just, with his pensive face, on which one saw the greatest energy, tempered by an air of indefinable gentleness and candor” (testimony found in Les Carnets de David d’Angers (1838-1855) by Pierre-Jean David d’Angers, cited in Veuve de Thermidor: le rôle et l'influence d'Élisabeth Duplay-Le Bas (1772-1859) sur la mémoire et l'historiographie de la Révolution française (2023) by Jolène Audrey Bureau, page 127). In Souvenirs de la révolution et de l’empire, Charles Nodier (who was twelve years old when he met Saint-Just…) agrees in calling him ”handsome,” but adds that he ”was far from offering this graceful combination of cute features with which we have seen it endowed by the euphemistic pencil of a lithograph,” had an ”ample and rather disproportionate chin,” that ”the arc of his eyebrows, instead of rounding into smooth and regular semi-circles, was closer to a straight line, and its interior angles, which were bushy and severe, merged into one another at the slightest serious thought that one saw pass on his forehead” and finally that ”his soft and fleshy lips indicated an almost invincible inclination to laziness and voluptuousness.” How would you know what his lips were like, Nodier. In Essai historique et critique sur la révolution française (1815) Pierre Paganel writes that Saint-Just had ”regular features and austere physiognomy.” He describes his complexion as ”bilious” while Nodier calls it ”pale and grayish, like that of most of the active men of the revolution.” Similar to Élisabeth’s description, Nodier writes that Saint-Just’s eyes were big and ”usually thoughtful,” while Paganel instead writes they were ”small and lively.” Saint-Just was of ”average height” according to Paganel, but ”of small stature” according to Nodier. According to Paganel, Saint-Just had a ”healthy body [and] proportions which expressed strength,” while Saint-Just’s colleague Levasseur de la Sarthe instead wrote in his memoirs that he was ”weak in body, to the point of fearing the whistling of bullets.” Finally, Paganel also gives the following details: ”large head, thick hair, disdainful gaze, strong but veiled voice, a general tinge of anxiety, the dark accent of concern and distrust, an extreme coldness in tone and manners.” In Lettre de Camille Desmoulins, député de Paris à la Convention, August général Dillon en prison aux Madelonettes (1793) Desmoulins jokingly writes that ”one can see by [Saint-Just’s] gait and bearing that he looks upon his own head as the corner-stone of the Revolution, for he carries it upon his shoulders with as much respect and as if it was the Sacred Host.” In Histoire de la Révolution française(1878), Jules Michelet claims that Élisabeth Le Bas had told him that this portrait, depicting Saint-Just as having ”a very low forehead, [with] the top of his head flattened, so that his hair, without being long, almost touched his eyes,” was similar to what he had looked like.

Jacques-Pierre Brissot — The following was documented after Brissot had been arrested at Moulins on June 10 1793 — ”height of five pieds (162 cm), a small amount of flat dark brown hair, eyebrows of the same color, high forehead and receding hairline, gray-brown, quite large and covered eyes, long and not very large nose, average mouth, long chin with a dimple, black beard, oval face narrow at the bottom” (cited in J.-P. Brissot mémoires (1754-1793); [suivi de] correspondance et papiers (1912)). In Journal During a Residence in France, from the Beginning of August, to the Middle of December, 1792 John Moore described Brissot as ”a little man, of an intelligent countenance, but of a weakly frame of body” and claimed that a person had told him that Brissot had told him that he is ”of so feeble a constitution” that he won’t be able to put up any resistance was someone try to assassinate him.

Jérôme Pétion — described as ”big and fat” (grand et gros) by Louis-Philippe in 1850 (cited in The Croker Papers: the Correspondence and Diaries of the late right honourable John Wilson Croker… (1885) volume 3, page 209). Manon Roland wrote in her memoirs that Pétion ”had nothing to regret physically; his size, his face, his gentleness, his urbanity, speak in his favor” as well as that he ”spoke fairly well,” a descriptions which Louis Marie Prudhomme partly agreed with, himself recording that Pétion ”had a proud countenance, a fairly handsome face, an affable look, a gentle eloquence, movements of talent and address; but his manners were composed, his eyes were dull, and he had something glistening in his features which repelled confidence” in Paris pendant le révolution (1789-1798) ou le nouveau Paris (1798). In Quelques notices pour l’histoire, et le récit de mes périls depuis le 31 mai 1793 (1794) Jean-Baptiste Louvet reported that, while on the run from the authorities after the insurrection of May 31, the less than forty years old Pétion already had a white hair and beard. This is confirmed by Frédéric Vaultier, who in Souvenirs de l'insurrection Normande, dite du Fédéralisme, en 1793 (1858) described Pétion during the same period as ”a good-looking man, with a calm and open physiognomy and beautiful white hair,” as well as by the examination of his mangled courpse on June 26 1794, which states he had ”grayish hair” (cited in Charlotte de Corday et les Girondins: pièces classées et annotées (1872) by Charles Vatel, volume 2, page 154.

François Buzot — according to the memoirs (1793) of Manon Roland, he had ”a noble figure and elegant size.” In the examination made of Buzot’s body after the suicide there is to read that he had black hair (cited in Charlotte de Corday et les Girondins: pièces classées et annotées (1872) by Charles Vatel, volume 2, page 153)

Charles Barbaroux — his son wrote in Jeunesse de Barbaroux (1822) that ”nature had richly endowed Barbaroux; a robust and large body; a charming, fine and witty physiognomy.” In 1867, François Laprade, who had witnessed Barbaroux’ execution as a thirteen year old, recollected that ”he was a brown man - that is to say he had brownish skin, black hair and beard, reclining figure” (cited in Charlotte de Corday et les Girondins: pièces classées et annotées, volume 3, page 728). Valazé’s daughter did in her old age too describe Barbaroux as very dark, with black hair, black beard and large black eyes. According to her, he was ”excessively beautiful,” with well-defined lips, beautiful teeth and fine, delicate features, so much so in fact that colleagues would often joke about his beauty. Cited in Ibid, volume 3, page 728.

Marguerite-Élie Guadet — According to his passport (cited in Charlotte de Corday et les Girondins: pièces classées et annotées, volume 3, page 672): ”height of 5 pieds, 5 pouces (176 cm) middle sized mouth, black hair and eyebrows, ordinary chin, blue eyes, big forehead, thin face, upturned nose.” According to Frédéric Vaultier’s Souvenirs de l'insurrection Normande, dite du Fédéralisme, en 1793(1858), ”Guadet was a man of fine height, meagre, brown, bilious complexion, black beard, most expressive face.”

Joseph Le Bon — his passport description (cited in Louis Jacob, Joseph Le Bon, (1932) by Louis Jacob, volume 1, page 63) gives the following information: ”Height of five pieds six pouces (178 cm), light brown hair and eyebrows, high forehead, average nose, blue eyes, medium-sized mouth, smallpox scars.”

Claire Lacombe — the concierge of the Sainte Pélagie documented the following about the imprisoned Lacombe: ”height of 5 pieds, 2 pouces (168 cm). Brown hair, eyebrows and eyes, medium nose, large mouth, round face and chin, plain forehead” (cited in Trois femmes de la Révolution : Olymps de Gouges, Théroigne de Méricourt, Rose Lacombe (1900) by Léopold Lacour)

Charlotte Corday — according to her passport, ”height of five pieds one pouce (165 cm), brown hair and eyebrows, gray eyes, high forehead, long nose, medium mouth, round, forked (fourchu) chin, oval face.” (cited in Dossiers du procès criminel de Charlotte Corday, devant le Tribunal révolutionnaire(1861) by Charles-Joseph Vatel, page 55)

Prieur de la Marne — a passport dated October 1 1793 gives the following details: ”age of 37 years, height of 5 pieds 5 pouces (176 cm), blondish brown hair and eyebrows, receding hairline, long nose, grey eyes, large mouth.”

Maurice Duplay — ”height of 5 pieds 6 pouces (179 cm), blondish brown hair and eyebrows, receding hairline, grey eyes, long, open nose, large mouth, round, full chin and face.” Descriptions given in 1795 and cited in Les deniers montagnards (1874) by Jules Claretie.

Jean Lambert Tallien — Both a spy report written in 1794 found among Robespierre’s papers and Mme de la Tour du Pin, a noblewoman who met Tallien in late 1793, describe Tallien’s hair as blonde. Mme de la Tour du Pin adds that said hair was curly and that he had a pretty face.

#might eventually reblog a part 2 i ran out of links for the moment#frev#french revolution#robespierre#georges danton#jean paul marat#albertine marat#simonne évrard#maximilien robespierre#augustin robespierre#camille desmoulins#desmoulins#lucile desmoulins#charlotte robespierre#charlotte corday#brissot#pétion#prieur de la marne#maurice duplay#jean lambert tallien#joseph lebon#charles barbaroux#françois buzot#saint-just#louis antoine de saint just#yes robespierre was taller than brissot this is no drill#i like this beauty and the beast thing camille and lucile seemed to have going tho…

267 notes

·

View notes

Text

happy new year! i've successfully defrosted and i present to you medieval Lucile and Camille because i had a vision don't ask further questions because i may not have answers

#the vision was that i just really wanted to give lucile a sword#my art#french revolution#frev#lucile desmoulins#camille desmoulins

125 notes

·

View notes

Text

April 1897, the catacombs with some Marche Funèbre

And other random sketches

-

In case anybody asks, Grantaire sleeps on the floor

#les mis#frev#louis antoine de saint just#maximilien robespierre#camille desmoulins#lucile desmoulins#mordaunt#enjolras#combeferre#and other little guys#may or may not have a SJ problem

673 notes

·

View notes

Text

couples who shit talk together stay together

#frev#camille desmoulins#lucile desmoulins#shes grabbing his ass thats why you cant see her other arm

76 notes

·

View notes

Text

Which Underrated Woman from History are You?

Finally got around to making a uquiz featuring six of my favourite women from history! You can either get someone from the French Revolution, Roman Republic (I know, how unexpected!) or from 1700s/early 1800s.

Featuring scientists, writers, politically active icons and a few poets whose lives were intertwined with theirs, as a treat!

Enjoy and thanks everyone for sharing! ✨

#frev#french revolution#ancient rome#roman republic#history#tagamemnon#uquiz#tumblr quiz#which are you?#age of enlightenment#1700s#1800s#romantic era#18th century#19th century#émilie du châtelet#fulvia#clodia#mary shelley#ada lovelace#lord byron#literature#women's history#uquiz link#personality quiz#quiz tag#percy bysshe shelley#lucile desmoulins#camille desmoulins#catullus

307 notes

·

View notes

Text

I haven’t made a serious drawing in days

#this is why I barely draw girls 💔💔💔#frev#french revolution#art#lottie art tag#frev art#camille desmoulins#camille#desmoulins#lucile desmoulins#frev shitposting

143 notes

·

View notes

Text

hi

this is just a quick thing i made im gonna get around to things soon

#dupsmoulins?#caplessis???#what???#leafdiarist#Leafdiarist???#leafdiarist it is#if you have better ship name suggestions please lmk.#update as I am writing this as a draft...#my friend said that caplessis sounds like a scientific process.#I cannot stop thinking abt this now omaig#they also said dupsmoulins sounds funky 😭...#idrc if you guys use these names go fuck around with it if you would like#lucile desmoulins#camille desmoulins#frev#frev shitposting#frevblr#jumps and backflips and jumps again#antoine with a triple e's art or sumn

86 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy 255th Birthday Lucile Desmoulins!!!!!!!!!

Born on January 18, 1770 in Paris.

Painting by Louis- Léopold Boilly

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

hi guys

#frev#frevblr#maximilien robespierre#robespierre#frev community#fanart#french revolution#frev art#louis antoine de saint just#saint just#camille desmoulins#lucile desmoulins#saintspierre#robesmoulins

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

Understanding both Camille and SJ has really made me push for Robesmoulins and Saintspierre with equal passion.

I can already see the one-sided attraction in Robesmoulins with Camille being too dense to realize Max was into him until years later when he has a wife and a son and it’s 1794 AND Max has moved on to SJ who happens to like him back lmfao.

#frev#random thoughts#maximilien robespierre#camille desmoulins#antoine saint just#french revolution#lucile desmoulins

81 notes

·

View notes

Text

Camille’s long and uphill battle to get Lucile

Monsieur, I am not mistaken and I am forced to agree that your letter is worthy of a father and full of wisdom. The first moments of pain that I experienced were followed by the calm of reason, and I take advantage of this calm to allow myself a few observations regarding your letter and putting them before your eyes.

Don't let my probity scare you. The reflections that M. Duplessis made me make on your [sic] uncertain state. My uncertain state is not uncertain. I am a lawyer in the parliament of Paris and what makes your state certain in this profession is not to be on the board, but talent and work. I am certain morally of being in charge of all the appeals of the sentences of Guise, which alone will compose for me an honest cabinet and an income of 7 or 8,000 livres at least; I cannot believe that there exists anyone who, after having read the memoir that is printed about me at this moment, tells you that my condition is uncertain. The letters I have from MM. Lorget and Linguet would prove to you, if you read them, that my condition is not uncertain. Already I have a flow of business which can only grow and I will have won a hundred louis this year, supposing that I lose the lawsuit which is about to be judged and whose gain would be worth more than two thousand écus to me.

On future events which may call me back to the provinces. I took a vow to stability in the bar of the capital, this vow is expressed clearly in the epistle and the printed memorandum which I gave to you. There exists only one thing that could make me detach from Paris and make a stay in the provinces bearable, it would be if I met Mlle Duplessis there, to what oaths must I bind myself in order to take away this fear that I will leave Paris? I see very well that you do not know how much I love your daughter, since you suppose that I would be able to sadden her by taking her away from a father to whom she is so tenderly dear.

On the impossibility for me to have a house where your daughter, like at your place, could find the softnesses and charms of life. There is something touching about this paternal fear that would have made me reproach myself for my premature research. But did you believe that Mlle Duplessis is less dear to me than to you and that I wanted a happiness that would have cost her the sacrifice of the comforts of life? As for me, the sweetness and pleasures of life would have been to live with her and with you, and these pleasures would have made all the others insipid to me. There are two things here that I cannot believe, first off the fact that this fear so natural to a father that his daughter would be less happy did not alarm you from the first moment you found out about my goal; second off, that your answer here would have been the one I had the pleasure of seeing. If you had thought that Mademoiselle Duplessis' change of lodging would deprive her of the pleasures of life, it would not have been with me that she could find those pleasures. I had not concealed my lack of fortune, nor sought to surprise your avowal by magnifying my hopes, in order to have the satisfaction of showing you that I had brought into this affair all the frankness and delicacy which befits my profession; I almost decried my father's fortune and succeeded so well that you then said to me: ”With the help of your fortune, I could wait until some brilliant affair had rescued me from obscurity.” You said this to me in much stronger terms, for your expressions were that, no longer being forced to run after an écu, I could devote myself without distraction to studies which would later make me known later as a jurisconsult, if the embarrassment of my stammer was an insurmountable obstacle which prevented me from succeeding in my pleading. It is clear that you did not flatter yourself then that I could put together a home for Mlle Duplessis. However, this beloved child was still not less dear to you at the moment and you surely didn’t think that she would lose the comforts of life, but you understood that there was a way to arrange it so that she would not have to make any sacrifice until the time which is not far off, when my condition would bring me 10 to 12 thousand livres. Did Mlle. Duplessis need a house other than yours for a few years? I would even have liked her to continue to live together with you, and for the change in her adress, while at the same time making me the happiest of all men, only to have added to the sweetnesses of life without it costing her any deprivation. Although the dowry I propose to give her is of a certain consistency, you may remember that when you mentioned this section, I kept silent. Surely, to wait until my estate was enough I did not need to find a dowry. At the present moment, I am able to count only on 3 or 4 thousand livres that I would get this year from my work or from my father. But wouldn’t these 4 thousand livres, joined to the 3 or 4 that you would give to mademoiselle your daughter, be enough for a house worthy of her? Of you I wouldn’t ask for anything more. She would have brought a thousand amiable qualities into the household; as for me, I would have put my estate there and I dare say some talents. It would have been a marriage without a dowry like that of the laborers, but those of that time are well worth those of ours. I never made mine a business, the only dowry I would have asked for was that one loves me, not as much as I do (in return), that is impossible, but I am sure that mademoiselle your daughter would have been touched to see me solely occupied with the care of paying her the debt of happiness that I would have contracted.

You urged me to overcome my affection. If it were only an affection, it could be overcome, but the wound is deeper. Remember, monsieur, in what dejection I appeared before you, my state had become so violent that whatever you might have said to me, it was impossible for my pain to wring my heart more on leaving your house compared to what fear had caused it upon entering. That is why, even though it cost me, I begged you to tear off the blindfold and uproot my hope. But how much you have decreased it instead. I only asked for a distant hope and you gave me a near hope. Fortune, you told me, would not determine your choice and you did not make happiness consist of fortune. I exercised an honorable profession that it was not even necessary to fulfill with a certain brilliance in order to appear to you worthy of belonging to you; it was enough for you that your daughter was loved tenderly and constantly and that second to her your son-in-law loved only work. Who would have believed in my place that this son-in-law was really me. You did more: you invited me to spend holidays and Sundays at your countryhouse and you allowed me, you even warned me to let my father know about this interview. At this moment my father has probably written to you and part of my joy was to think about he who does not care about the dowry (that of my mother, who is still whole despite our misfortunes because it has always been sacred in his eyes, was more important) but who loves me with tenderness and is no doubt delighted that I have finally obtained this demoiselle Duplessis of whom I have been speaking to him incessantly for five years and whom he wanted me to show him when he spent a few days in Paris two years ago. In my letter from March 22, it was no longer vain conjectures and equivocal walks in the Luxembourg that I entertained, it was speeches that a father of a family had given me, hadn't I had to base myself entirely on his answer?

It would be deceiving my honesty to make any promises to me at this time, considering the young age of your daughter. If you only wish to postpone the term of my happiness, I have already waited five years, and I can still wait another two and even more, but since I above all make happiness consist in this thought that we love each other for life, I only beg you to tell me if after two years and when my heart has perhaps been consumed by these attachments, I will not have to renounce the sweet habit of loving her. My age was no more advanced four days ago when you gave me such imminent hopes. Also this reason that you bring is not the real one and you yourself do not disguise it from me. An even more essential point to observe to you, is that it for me would be putting up a barrier against the parties which within two years could present themselves and to make you give yourself up to opportunities which fulfill your views. Besides, did I ask for Mlle Duplessis right away? I only asked if one day, when my position would be fully complete, I could receive her hand. As for what concerns me in this article, what occasion, what views can you tell me about? What purpose can I have but to be happy, and I can only be so, monsieur, with you. Where can I find another family that I love so much? I have gone too far with mademoiselle Duplessis to ever retrace my steps, and if you come to take away from me the hope that you have made me conceive, you will have unwittingly caused the misfortune of my life. I come to the great reason, that it would be to put up a barrier against the parties which could present themselves within two years. If, when you did me the honor of granting me an interview, you had said that to me, everything would have been very clear and I would have had nothing to respond to. But, since then, you declared to me that fortune would not decide your choice for mademoiselle your daughter, and that you would seek for her only a husband who would love her with tenderness; so you mean that in two years from now there may come people who like her better than me. If so, let it be. All of them will undoubtedly love her positively, but to love her more desperately than me will be difficult. And I will always have been five years ahead.

You told me enough that you had not changed your mind in regards to me, and that, if I succeeded in destroying the motives that you were good enough to explain to me in detail, you would return to your first feelings. It seems to me that I have replied in a satisfactory manner to the objections of M. Duplessis; I therefore conjure you to come back to your first favorable dispositions and return for me the heart of a father. I would very much like you and Madame Duplessis to grant me an interview. I would remove all of your doubts, and I would come down to details that cannot enter into a letter: do not push me away from your bosom but allow me to give you both names to which my heart would refuse if I had to give them to others. It is with these feelings that I have the honor to be, monsieur, your very humble and very obedient servant. Desmoulins Lawyer in parliament. Letter from Camille to Lucile’s father, March 1787

Madame, It is now that I have lost all hope: but what do I risk by writing to you so that a reply from you yourself will completely disperse it. I returned to Paris a bit less discouraged than I had left it, because the prize of the case that I had won last year, the many bags of lawsuits that I brought back, the ostensible proofs of public confidence, and even more the union of his province to which my father had been named all with one voice, and which gave him the greatest credit, had raised my hopes. I got tasked, among other things, with the biggest criminal affair that there was in the Parliament of Paris at the moment. All of this having either reestablished the inequality of my fortune or compensated for it by public consideration, I had fallen back on my dreams of happiness. But the carriage that you took has destroyed all of my illusions. I sense that the daughter can’t walk on foot when her mother rides in a carriage. My present fortune lines up with the advantages that Mr. Duplessis had told me he would give to mademoiselle, but the luxury of a carriage is beyond my strength. Judge if the noise of this carriage pleases me, when it warns me that you are driving your daughter into the world where she is going to find so many admirers. Thus will all my dreams vanish. Do I dare, however, Madame, to remind you of what you told me, that you would put no ambition in the choice of son-in-law, and that my profession seemed to you quite honest and quite noble. This is what inspired me with some confidence. Must you today take away from me a hope so dear to the attachment that I have nurtured for so many years to come out of my heart with hope! But this is impossible. After you made me the honour of telling me your views on the position you intended for Mademoiselle Duplessis, I admit that I flattered myself that all that I lacked was her consent, that she would be touched by a pursuit so constant and filled with so much trouble, and that I’d obtain some payback from her compassion, if I could not expect it from another feeling. How many times I have consoled myself over my sorrows with the thought that there is no affection more tender and lasting than the one born from compassion. If there is something humiliating for self-esteem in owing one's happiness only to this feeling, I was on the other sure of soon inspiring true tenderness in Mademoiselle your daughter by my feelings, and of ennobling myself in her eyes by the dignity of my whole life. I beg you, Madame, do not read this letter to your husband, with whom I would still pass for a madman, it is to you that I am writing it, to you who never send back my letters and whom I I have never left, without leaving your presence, if not full of contentment, at least full of patience. Shall I not have the pleasure of conversing with you at least sometimes? I apologize if I have made this letter too long, but tired of other people's affairs, it is natural that I should fall back on my own, which I have managed so badly, and in these first moments of me leaving my family, I have difficulty accustoming myself to solitude, which the multiplicity of my affairs and my lack of knowledge make a necessity for me. I found verses printed and maimed in provincial notices which I had addressed to you; I take the liberty of sending them to you and of renewing my homage to you. Will you do nothing for your poet? I have the honour to be, with the deepest respect, Madame, Your very humble and very obedient servant, Desmoulins Camille to Lucile’s mother, December 5 1787

Madame, I am sending you the consultation of M. Fournel regarding the case of the priest of Bourg, for which I have just completed the supporting memorandum. Some considerations are delaying its publication until Easter. The judges of Laon, who were afraid of it, have just written to the attorney general and the first president of the court, to try to obtain the removal of what concerns them from my memorandum. I cannot take enough precautions to avoid compromising myself and risking the loss of my position, which has become very precious to me since the speech you were kind enough to give me in Luxembourg. Once you have read my memorandum, and compared it with the feeble consultation of Me Fournel who nevertheless enjoys such a great reputation, I dare to imagine, Madame, that you will forgive me for having also hoped for some consideration; and that you will forgive me for having nourished another much more cherished hope, remembering that M. Duplessis, a year before yesterday, did not even demand that I should become a famous lawyer in order to obtain Mademoiselle Duplessis. Now this hope is weakening every day, I see that everyone has the same eyes for your daughter as I do, it seems to that in every moment someone comes to ask for her hand. I am waiting for my justificatory memorandum which will finally fix my fate and make access to you either open or closed forever. The encouragement that has sustained me most in this work to which I have sacrificed all my business has been the hope of presenting it to you. Is it possible, Madame, that when the image of happiness that I find with you detaches me from all other societies and makes them bland and unbearable, you never tire of pushing me away from yours, which would take the place of the whole universe? I have the honour to be, with the deepest respect, Madame, Your very humble and very obedient servant, Desmoulins Camille to Lucile’s mother, March 4 1788

Madame, What harm have I then done to you for you to treat me so harshly? And how could a letter that I wrote only with the purpose of persuading you offend you and draw such a bitter response from me? I don't want it to be your fault if I conceived a mad passion, but don't we owe anything to those who are made to suffer even without our fault? Couldn’t you have made me understand in a less mortifying way that there was madness in my pursuit, that the disproportion of fortune (something which I wasn’t aware of until yesterday) was an insurmountable obstacle? You seemed unhappy with me, and I couldn’t be unhappy with you. On the contrary, I would have thanked you for the care you took in preventing a disastrous passion, I would have thought myself treated well. Because you know better than anyone that it takes very little to make me believe it. Sometimes you have really put my self-esteem to severe trials! One does not die of spite, if so I would have already have died a thousand times. But all it would take is a glance, half a smile, to bring me back. Even today, at this moment, all my self-love is incurable! I am trying to reconcile the harshness of what you have just written to me, with the very different speech that you gave me, and I am trying to interpret it favorably. It seems to me that the remedy you employ is either too violent or too little. It's up to you to make yourself lovable anywhere other than at my place. Is it just a defence? Or is it not also a permission? Forbidden to make myself friendly in your eyes at your place, permission to make myself friendly, if possible, in the Luxembourg. This is what it means to be a lawyer. We pick at everything, and instead of a woman of wit explaining her thoughts in two words, we always write, which eads me to believe that your answer does not entail a banishment for life, that was what you had the pleasure of repeating for me in the Luxembourg, not at the moment, and besides, it's still a letter that I received from you, which is something. You see Madame that I am laughing and crying at the same time. Thank you, one more word from you. Or, treat me so harshly that you force me to hate you and even your demoiselles; or, if your feelings have not changed since the conversation I had the honor of obtaining from you in the Luxembourg, refuse me permission to come to your house now, so as to give me the hope of one day obtaining it. I have the honour to be, with the deepest respect, Madame, Your very humble and very obedient servant, Desmoulins Camille to Lucile’s mother, March 16 1788

[…] Oh, I would like to see Melkam! How curious I would be to hear him speak, how he would teach me things! Always the same thought comes to besiege me, it’s a very singular thing… Tell me, are you thinking about me or are you forgetting me? Ever since… every day I don’t miss it… is carved into it… I’ll never call it anything else. It is to him that I have consecrated it, he will take my place. […] Lucile in her diary, July 21 1788

I always continued to chase the same hare, the mother lured me into the house, the father promised me his daughter, gave me his word of honour; the girl made me think she wanted me; a few days later came a terrible storm which threw me far from the door, farther than ever. […] I could not imagine that by courting the girl I had pleased the mother, and that she wanted to take a chance on me; I could not trust the rascal of a servant who went home to me to invite me to take lodgings in the apartment next to theirs, who said that the girl was flirtatious, that it was was the mother who liked me, that I would succeed. Today the scales have fallen from my eyes; but then I thought they wanted to test me, a new promise to give her to me, a new rupture. Camille in a letter to his college comrade Pierre Jean André Grasset, October 27 1788, cited in Camille et Lucile Desmoulins: un rêve de république (2018).

One day, MC was thinking about his portrait; he says to Maman: ”I would like to have a great reputation, do you know why? It's not for the glory, but to be free to do what I want. Then I wouldn't look ridiculous." "It's true, Maman told him, because one passes a lot of faults onto a great man." Lucile in her diary, 1789

Madame, If you knew what a trap was set for me, you would have had compassion for me. I see well that I am no luckier when it comes to friendships than I am when it comes to love. It is not so that I for a moment have given credence to the slander. It is thus, I said to myself, that I was slandered to Madame Duplessis, it is due to these artifices that I was barred from entering their house... However, I was only asked to suspend my judgment, I was to have some clarification this morning for which I would be grateful. I went to look for it and saw only a gross conspiracy against my happiness. I don't know who to trust in the world anymore. Madame, you have sometimes shown interest in me, have pity on my situation; I no longer dare to come to your house, three times I have been refused entry, but deign to give me a moment's interview to unravel this riddle for you, and don't think that I could ever believe that Mademoiselle Lucile and M. Duplessis deceived me so cruelly. Virtue and sensibility have a physiognomy that art does not counterfeit. I distrust all men now, but something tells me that my trust would not be betrayed if I place it in you without reserve. I have the honour to be, with the deepest respect, Madame, Your very humble and very obedient servant, Desmoulins PS — last Tuesday, you sent me back full of joy. I wrote my issue in 12 hours, but the pains are in proportion to the pleasures, and you have given me so much grief for eight days that I have not been able to write a single line; it is you who would have given me genius if you had wanted to. This issue, which belonged to you, since it was thanks to you I had it written in such a short time, you were cruel enough to send it back to me without wanting to read it. Madame, I’m writing this letter for you alone, if it is imprudent, don’t show it to anyone else, I beg you. Camille to Lucile’s mother, April 14 1790.

Madame, I have the honour of letting you know MM. De Mirabeau and Emmery are coming over next Sunday in the afternoon to see the obelisk at Bourg-la-Reine. I had not dreamed of Madame Duplessis coming to Paris today and I had sent away the wigmaker of whom I have no use when you’re at Bourg-la-Reine, which makes me dry with impatience at this moment when I wait for him in order to go and place myself at your feet and recommend myself to your all-powerful intercession. I have to honour to be, with all the feelings that you inspire in me, Madame, Your very humble and very obedient servant Camille Desmoulins. Camille to Lucile’s mother, April 28 1790.

Madame, Here is the letter from Mirabeau that I found at my house, as I expected. He came over with it himself according to the doorman, and you will recognize his handwriting. Did you notice how Mademoiselle Lucile sent me away cruelly yesterday? But one must always admire her more and more and she must be allowed to have a little pride. I really hope that now at least, I have no more new talents to discover in her, if she has any that I still don't know about, please hide them from me. I kiss your hands; as for Mademoiselle Lucile, there is no way to kiss hers even with gloves on. Regardless, Madame, you are so much loved. What hurt you yesterday has hurt your celestial Lucile so much that if you wanted to take my interests to heart, I would hope for everything. Forget what she forbade you. As for me, I see well that I would never touch her, even if I addressed such beautiful prayers to her as the one she made to God. Camille to Annette Duplessis, May 10 1790. The prayer to God Camille is referring to here might be the one Lucile

It is now, O Lucile, that I truly find myself to be pitied. Up until now I had blamed fortune, and it could come, I had blamed your parents and they could, when they saw me have a status and a reputation, stop distancing me from you. But now that I am allowed to see you, the hope of being happy has vanished forever. I see too clearly, O Lucile, that your heart cannot approach mine. Your face, as if of its own accord, continually turns away from me. In vain my pain, a constancy of 7 years and my tears are before your eyes. I am not lovable enough, I do not want so many charms and qualities. The sadness that I feel near you at not being able to please, combined with my usual melancholy, makes my company tiring for you. All the conversations I hear seem so cold, so indifferent to me that I cannot take any part in them. In spite of the boredom of my company, touched perhaps by my tender attachment, you make an effort on yourself, and instead of retiring to your books, and to this work that you love so much, you prolong for me the pleasure of enjoying your sight, I thank you for that, beautiful Lucile, I thank you for this kindness. But this pleasure of seeing you is cruelly poisoned by this thought that I will never succeed in pleasing you. I see too well that my presence is for you, oh beautiful Lucile, neither that of a lover, nor that of a husband, nor even that of a friend. No matter how much I question your heart with my gaze, it does not respond. Your eyes never turn towards your unfortunate lover. After 7 years of such tender love, I find the opportunity to present my hand to you for a moment, and you have the harshness to refuse me, to tell me that I will never obtain this hand so ardently desired. Rather than offering me a seat in your carriage, today you would rather have seen me die of fatigue following you. It’s done, I no longer hope to find the way to your heart, no, this charming Lucile will never love me, she will never be my Lucile. How little do they know you, those who congratulate you and who envy you. O unfortunate Desmoulins. If you had placed your happiness in riches, in dignities, in glory and you had been unable to achieve it, only you and your madness would have to be blamed for your ills. But to have placed it in the possession of Lucile's heart, when her mother responded to me from this heart 5 years ago, when she had emboldened me to ask her daughter in marriage, when her father had approved of me, when he had deceived me so cruelly about his daughter's emerging inclination, when they closed my heart to all affection, to all other happiness, after 7 years of constancy, to see that one displeases, that one shall never obtain this promised happiness, this happiness placed in nature. This is what tears me apart, but I would rather be unhappy alone than try to get you through importunity, extract half-consent and make you unhappy with me. I want to get used to the thought that she will never be mine, that she will never put her hand in mine, that I will not rest on Lucile's breast, that I will not press her against my heart. Retire into solitude, O unhappy Camille, go and cry for the rest of your life, forget if possible about her singing, and her loud piano, and her graces, and her wit and her beauty, and her walks and her window, and her writings, and so many qualities of which you were no less sure for having only guessed at them. Camille in an undated letter to Lucile from 1790, cited on page 55-56 of Journal 1788-1793: Lucile Desmoulins ; texte établi et présenté par Philippe Lejeune (1995)

You told me, O Lucile, that I would waste my time loving you. Well! I resign myself to my misfortune, I renounce the hope of possessing you. My tears flow abundantly. But you won't stop me from loving you. May others have the pleasure of seeing you, of hearing you. Those people were loved… from heaven. As for me, I must not be in its anger. O Gods! Loving a Demoiselle with… Camille in an undated letter to Lucile most likely from 1790, cited on page 57 of Journal 1788-1793: Lucile Desmoulins ; texte établi et présenté par Philippe Lejeune (1995)

O you who are at the bottom of my heart, you who I dare not to love, or rather who I dare not say that I love, dear C…, you believe me to be insensitive!… Ah cruel!… Do you judge me according to your heart, and could this heart attach itself to an insensitive being? Well yes, I prefer to suffer, I prefer that you forget me... O God, judge of my courage... Which one of us has the most to suffer? I dare not admit it to myself, what I feel for you! I only occupy myself with disguising it... You suffer, you say... Ah, I suffer more! Your image is constantly present in my thoughts, it never leaves me... I look for your faults, I find them, these faults, and love them... Tell me why then all these fights... Why would I have to make it a mystery even to my mother? I would like her to know it, to guess it, but I would not like to tell her... O sublime thought! To think, yes, it is a blessing from heaven... C, I tremble to form only the first letter of your name... If someone were to find what I write! If you would find it yourself... Love... Ah, C... shall I be your wife? Will we be united one day? Alas, perhaps as I form these wishes, you forget me... Oh, pain! You, forgetting me... at this cruel thought my tears wet my paper, my eyes are troubled, I barely make out what I'm writing... That a tender soul has to suffer... Yes, don't know that I love you , go, flee, C, go seek happiness near another… I will live far from you, I will learn one day that a link… Ah, would this link make you happy? Should you be so far from me?… I will have no reproach to make of you… it is I who am cruel towards me… You are going to make me cherish solitude even more… Your name that I have carved into the corner of a tree, your name that only I can see... I call it the tree of mystery... Alas, very often I hold it in my arms, and when the wind shakes it, it seems to me that it’s you who breathe... It's in my garden that I write, sitting on the ground at the foot of my lawn, leaning my elbow, leaning my body, I'm alone... Drops of water fall, a ray of sunshine pierces the foliage… Maman went to Paris, maybe you're with her. But is it really true that you love me? You love me... you love Lucile... well if you love me, run away from me! I am a monster…I have everything xxxx… I can no longer think, I am annihilated……… I fall into daydreams in spite of myself… Oh, what is the human heart? What then am I? Me... you... and everyone... Why do I exist? These clouds that pass over my head, who makes them pass? C, why this stubbornness to hide the fact that I love you? Will you come back again... will I be able to run away from you wishing to be near you?... Will I still see you looking for my thought in my eyes, sometimes thinking I guess it, alarming you with a word that you have misinterpreted, will I still hear you complaining to Maman about my indifference? What will be the end of all this? What will become of both of us? Alas, maybe separated forever, we will mourn our fate in silence… We will remind each other, and we will say “It is together that we should be happy”. Time will pass like this, death will overtake us, we die……..and in this cruel moment that we… This thought tears me apart! Oh, come, come and put a veil on the future! Lucile in her diary, July 16 1790

Today, December 11, I finally see myself at the fulfillment of my wishes. Happiness for me has been a long time coming, but finally it has arrived, and I am as happy as one can be on this earth. This charming Lucile, whom I have talked to you so much about, whom I have loved for the past eight years, at last her parents give her to me and she does not refuse me. Her mother just came to tell me the news, crying of joy. The inegality of fortune, M. Duplessis having 20 000 francs a year, had up until now held back my happiness. The father was dazzled by the offers made to him. He dismissed a suitor who came with 100 000 francs. Lucile, who had already refused 25 000 francs a year, had no trouble giving him her permission. You are going to know her by this single trait. When her mother told me a moment ago, she brought me to her room; I threw myself before Lucile’s knees; surprised at hearing her laugh I open my eyes, hers were in no better state than mine, she was all in tears, she was even crying profusely and yet she was still laughing. I have never seen such a delightful spectacle, and I would not have imagined that nature and sensibility could unite these two contrasts to such an extent. Her father told me that he no longer opposed us marrying because he wanted to give me the 100 000 francs that he promised his daughter beforehand, and that I could go with him to the notary whenever I wanted. I responded: You are a capitalist, you have moved cash around your entire life, I won’t interfere in the contract and that much money is going to embarrass me. You love your daughter too much for me to stipulate her. You’re asking nothing of me, so make the contract however you want it. He also gave me half of his silverware, which amounts to 10 000 francs. Please, don’t make too much noise about this. Let us be modest in prosperity. Send me your consent and that of my mother post by post; be diligent in Laon for dispensations and let there be only one publication of banns in Guise as in Paris. We can get married in eight days. My dear Lucile longs as much as I do that we may no longer be separated. Do not arouse the hatred of our envious people with this news, and like me, keep your joy within your heart, or at most pour it out in the bosom of my dear mother, my brothers and sisters. I am now in a position to come to your aid, and that is a great part of my joy: my mistress, my wife, your daughter and her entire family embrace you. Camille to his father, December 11 1790

#camille desmoulins#lucile desmoulins#desmoulins#frev#long post#i don’t think the term ”made for each other” can ever be applied to another couple after this#biggest drama queens… i mean patriots and lovestruck fools EVER#also what did lucile tell her mother that camille told her to just forget 😐😐#annette duplessis

74 notes

·

View notes

Text

Merry Christmas (or whatever you celebrate) from Cami and Luci!

#i had the suddent urge to draw them lolz...#frev#french revolution#camille desmoulins#lucile desmoulins#lucile duplessis#frev art#frevblr#frev fandom#frev community

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

What a talented young man. Surely nothing bad happens to him

#camille desmoulins#Desmoulins#vieux cordelier#lucile desmoulins#maximilien robespierre#robespierre#frev#antoine saint just#saint just#french revolution#frev art#my art

194 notes

·

View notes