Text

Form, Function, Content, Payroll: Micro and Macro Politics of Design

Essay written in collaboration with Maya Ober, published in the 1st issue of the journal House of Common Affairs, 15 Apr 2019.

The House of Common Affairs (HOCA) is a new journal conceived and edited by Paula Minelgaite. It provides an opportunity to challenge the niche and yet popular field that exists in the overlap between the arts and journalism. HOCA invites a more diverse range of voices into the conversation with the aim to promote an international and interdisciplinary exchange of ideas, as well as knowledge. It seeks to offer a space for critical thinking with the aim of provoking further developments in this field.

The “Fourth Estate Utopias” is the first issue of HOCA, and as such addresses the project’s subtitle, ‘fancy discussions about Fourth Estate utopias,’ and is about the role of visual communication in relation to journalism.

As depatriarchise design, Maya Ober and I contributed an essay titled “Form, function, content, payroll: micro and macro politics of design”. Get your copy here and read our piece.

Photos: Paula Minelgaite.

#HouseOfCommonAffairs#communication#design#editorialdesign#publication#journalism#designjournalism#depatriarchisedesign#fourthestateutopias#feminism#writing#journal

0 notes

Text

depatriachise design is Nominated to the Swiss Design Awards 2019

Nomination in the category “Mediation”, 11 Apr 2019.

Maya Ober and I are very proud to announce that depatriarchise design is nominated to Swiss Design Awards 2019. It is an honour to be nominated together in great company of people whose practice we admire: common-interest run by Nina Paim & Corinne Gisel, and Ann Kern, the author of “Sounds Like a Choice”.

#design#feminism#nomination#award#depatriarchisedesign#mediation#swissdesignaward2019#feministplatform#activism#designactivism#womenindesign

0 notes

Text

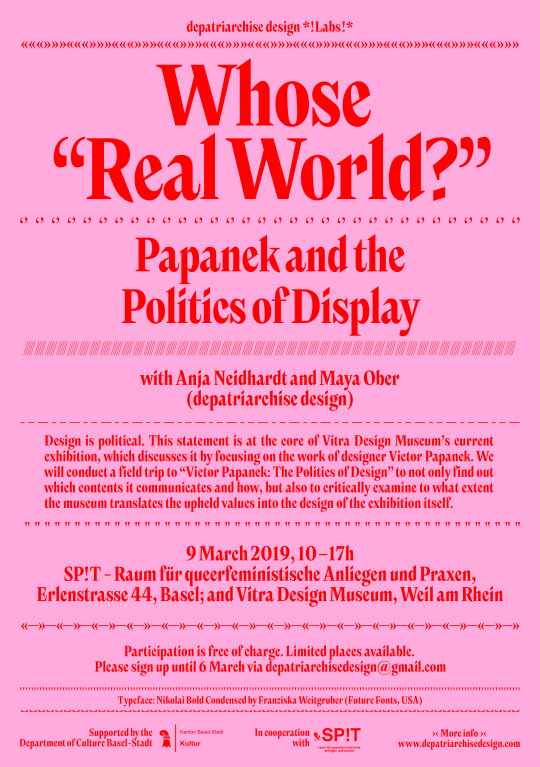

The Politics of Display: Review of Vitra Design Museum’s Papanek Exhibition

German and English, and published on the website of depatriarchise design, 23 Feb 2019.

Design is political. This realisation began to gain currency among many young designers around 50 years ago. In his work, too, Victor Papanek (1923–1998) focused on the political levels of what designers do. He himself was an industrial designer – and at the same time a harsh critic of his own discipline. This theme is just as topical today and is currently being explored in an exhibition focusing on Papanek at the Vitra Design Museum.

In 1970, protesting students and activists disrupted the International Design Conference in Aspen, forcing the participants to vote on new resolutions that stood for more social and ecopolitical commitment. Victor Papanek, like many of his contemporaries, was convinced that not only functional and formal features and questions on the usability or saleability of a design had to be taken into account, but also its effects on society and the environment – as well as the interaction between the two.

… — Read the complete article on depatriarchise design

Und hier geht es zur deutschen Version: https://bit.ly/2KPtpxp

Cover image: Exhibition view, photo by Anja Neidhardt.

#design#politics#exhibitiondesign#curating#designcurating#feminism#socialdesign#papanek#vitra#designcriticism#review#activism#designactivism#intersectional

0 notes

Text

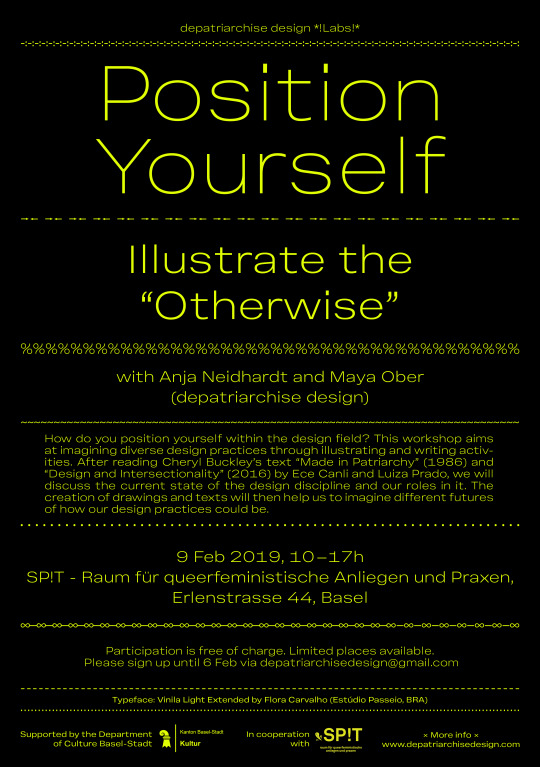

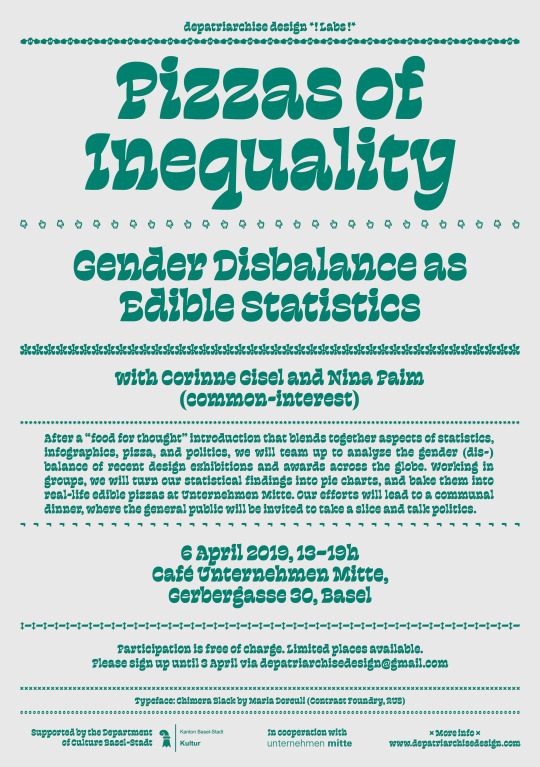

depatriarchise design *!Labs!*

Ongoing workshop series, developed and organised in collaboration with Maya Ober.

depatriarchise design *!Labs!* is a series of workshops dealing with politics of design and artefacts, trying to bridge between theory and practice, developing hands-on approaches to discussing the societal issues within design practice, through an intersectional feminist lens.

Each *!Lab!* is an educational experiment trying to expand and to question the established ways of teaching, learning, producing and displaying design. The *!Labs!* are rooted and inspired by feminist pedagogy produced in the course of decades, and couldn’t come to live without them. They are also spaces for dialogue, personal expressiveness, caring and unlearning – they are never meant to be finished, rather form part of a larger process of depatriarchising design. Using the existing online platform of depatriarchise design, we will share questions, assignments, reflections to engage into an exchange with the wider community to participate in the co-creation of knowledge and design productions.

Our *!Labs!* are spaces where participants can explore design from feminist perspectives, exchange ideas, find allies, and create hands-on tools for their daily design practice.

depatriarchisedesign.com/labs/

The Visual Identity of depatriarchise design *!Labs!*

Nina Paim and Corinne Gisel from common-interest, a non-profit cultural organisation based in Basel, were not only asked to develop a programme for one of the *!Labs!*, but also commissioned to design the overall visual identity of depatriarchise design *!Labs!*.

common-interest says: “We propose to use the visual identity of ‘depatriarchise design *!Labs!*’ as a platform to support and promote young female type designers. Simply put, for each workshop, we will select and purchase a typeface by a different female designer. By creating a singular identity for each workshop, the visual identity of ‘depatriarchise design *!Labs!*’ will grow into a diverse set of positions. At the same time, the identity will function as a type-specimen that promotes emerging names and thereby becomes a feminist tool for graphic design in and of itself.”

The first three *!Labs!* feature the following type faces:

Vinila by Flora de Carvalho

Nikolai by Franziska Weitgruber

Chimera by Maria Doreuli

depatriarchise design

depatriarchise design is a practice-led research platform that examines the complicity of design in the reproduction of oppressive systems, focusing predominantly on patriarchy, using intersectional feminist analysis. The platform is currently run by Berlin-based Anja Neidhardt and Basel-based Maya Ober.

common-interest

common-interest is a non-profit creative practice based in Basel. Their mission is to bridge socially and culturally relevant insight—scientific, scholarly, journalistic, artistic, or otherwise—and broad audiences through creative means of storytelling and mediation. In short, they are dedicated to making research public. They apply designerly ways of thinking across various disciplines such as writing, editing, publishing, curating, and exhibition-making. Founded by Corinne Gisel and Nina Paim in 2018, common-interest initiates its own productions, takes on commissioned projects, and offers its expertise to non-profit, public sector, and philanthropic clients.

depatriarchise design *!Labs!* is supported by the cultural department of the city of Basel.

#design#DepatriarchiseDesign#depatriachisedesignLabs#commoninterest#Basel#femaletypedesigners#feministdesignpractise#workshop#designworkshop

0 notes

Text

VenidaDevenida: Personal Space

Written in German, published in German and English (translated by Nicholas Grindell) in the printed issue of form 280, Nov/Dec 2018.

Spätestens dann, wenn ein Produkt in den Verkauf geht oder ein Gebäude eröffnet wird, müssen Gestalter*innen und Architekt*innen die Kontrolle über „ihre“ Designs abgeben. Zwar sind in Produkte und Gebäude bestimmte Funktionen und Verhaltensmuster eingeschrieben, wie sie allerdings schlussendlich genutzt werden, kann niemand genau vorhersehen oder im Vorhinein bestimmen.

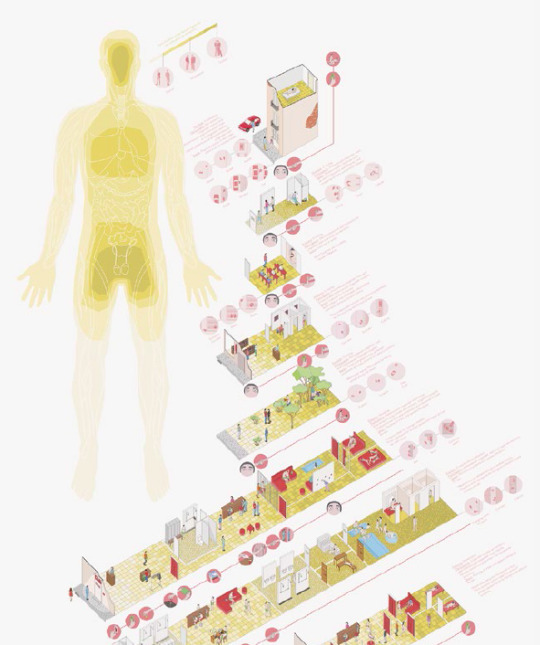

When a product goes on sale or a building is inaugurated, designers and architects must relinquish control of “their” creation. Although specific functions and patterns of behaviour are inscribed into products and buildings, how they are ultimately used is impossible to predict or dictate beforehand with any degree of accuracy.

Ana Olmedo und Elena Águila, die seit 2014 als VenidaDevenida zusammenarbeiten, wollen das allgemein vorherrschende Architektur und Designverständnis vor allem um die Perspektive von Nutzer*innen erweitern, die aufgrund ihres Geschlechts oder ihrer Sexualität Diskriminierung und Unterdrückung erfahren. Misogynie und Homophobie beispielsweise manifestieren sich nicht nur in Gesetzen und persönlichen Interaktionen, sondern auch durch Ergebnisse von Gestaltung (wie Objekten, Illustrationen, Werbung und Räumen). VenidaDevenida untersucht, wie sich Angehörige dieser marginalisierten Gruppen Objekte und Räume durch Interaktionen, die mit ihrer sexuellen Identität zu tun haben, aneignen und sie für ihren Widerstand gegen herrschende, unterdrückende Systeme nutzen.

Ana Olmedo and Elena Águila, who have been working together as VenidaDevenida since 2014, want to expand the prevailing definition of design and architecture to include the viewpoint of users who experience discrimination and repression on account of their gender or sexuality. Misogyny and homophobia, for example, manifest not only in laws and personal interactions, but also through design (in the form of objects, illustrations, advertising, and spaces). VenidaDevenida looks at the ways those belonging to these marginalised groups appropriate objects and spaces by means of interactions related to their sexual identity, using them as part of their resistance to prevailing repressive systems.

…

Den kompletten Artikel finden Sie in der gedruckten Ausgabe von / Please find the full article in the printed issue of form 280, Nov/Dec 2018.

Cover image: from VenidaDevenida’s project “Potentia Gaudendi, States of Aggregations”.

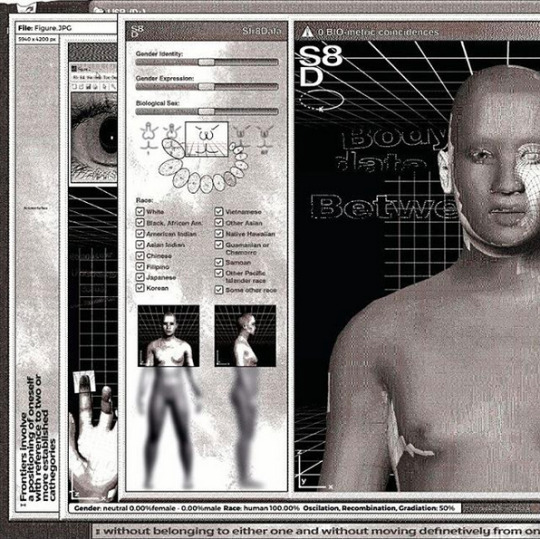

Second image: from VenidaDevenid’s project “Identification Failed: Non-normative Bodies Rendered with Binary Codes”.

#VenidaDevenida#design#designresearch#architecture#feminism#lesbian#LGBTQ#queer#publicspace#private#public#depatriarchisedesign#AnaOlmedo#ElenaAguila#formDesignMagazine#form#form280#gender#sexuality#oppression#discrimination#protest#creativity#sexualidentity#gendern#öffentlicheRäume#Feminismus#lesbisch#lesbischePerspektive#lesbianperspective

0 notes

Text

The Life of the Fair

Written in English and published in the printed issue of DAMN 70, Sep/Oct 2018.

Dutch designer Dick Spierenburg travels to Germany every week to work with the team of imm cologne. I met up with the creative director of the interiors fair at Messehochhaus, to get his inside view on the challenges, changes, and creativity that are crucial for imm cologne to be relevant to exhibitors and visitors, both of whom are redefining the way business is done in the design world.

Read my article in the printed issue of DAMN 70, Sep/Oct 2018.

Image: The architecture of Truly Truly’s “Das Haus” at imm cologne 2019, bathed in a warm colour palette, is composed of just three elements: walls, fabrics and plants. Truly Truly; Koelnmesse.

#DamnMagazine#Spierenburg#TrulyTruly#immCologne#furniture#design#fair#DasHaus#DasHaus2019#interiors#interiorsfair#curating#curator#creativedirector#interview#designjournalism

0 notes

Text

Consequences of Modern Standards

In collaboration with Lebogang Mokoena. Written in English and published in English and Finnish in issue 4/2018 Arkkitehti-lehti, the Finnish Architectural Review, Sep 2018.

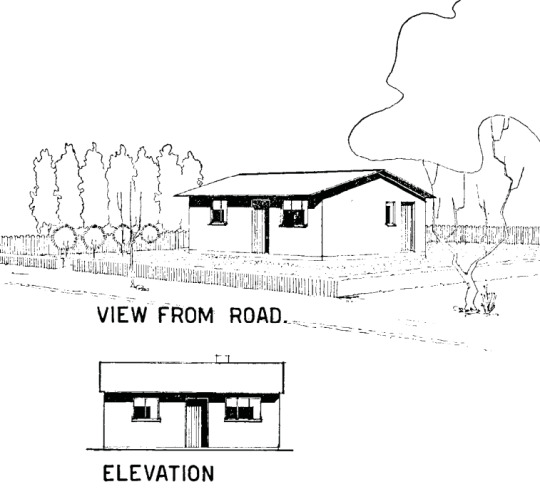

24 years after the end of the apartheid regime a majority of Black South African families living in townships are still housed in two bedrooms, one kitchen, and one sitting or dining room.

Four-roomed houses, as they are known in South Africa, are built out of cement bricks with one window per room, a corrugated iron or asbestos roof and very basic textured surfaces. Originally, there was no shower or indoor toilet. In many cases a tap is still only installed in the backyard. — The blueprint for these designs were developed by white, male architects like Douglas McGavin Calderwood who were highly influenced by modern architects from Europe. Impressed by the idea that there could be one uniform approach to housing problems of the time, South African universities established strong contacts with Le Corbusier and other European architects.

Read our article about modernist ideology and the design of houses in South African townships in issue 4/2018 of Arkkitehti-lehti, the Finnish Architectural Review.

Cover image: One of the architects working for the South African National Building Research Institute in the 1950s was doctoral graduate Douglas McGavin Calderwood. His thesis “An Investigation into the Planning of Urban Native Housing in South Africa” (1953) focussed on the question of how to implement the government’s township building programme and minimise costs. The illustration is taken from his thesis.

Streetview: Google Streetview: Molapo, Soweto today.

#modernism#architecture#soweto#southafrica#apartheid#lecorbusier#calderwood#standards#racism#oppression#township#RDPhouses#mandela#decolonisedesign#decolonisearchitecture#houses#dailyroutines#journalism#designresearch#collaboration#ark

0 notes

Text

So lebe ich: Maddalena Selvini

Written in German, published in German in the printed issue of The Weekender N° 30, Aug 2018

Die Produktdesignerin wohnt in Mailand in einem alten Industrieloft, das ihr als Wohnung, Atelier und Testlabor dient.

Maddalena Selvini steht vor einem großen, an die weiße Wand gemalten blau-grünen Quadrat. Sie schaut in den offenen, lichtdurchfluteten Raum und lässt ihren Blick wandern – hinüber zur Vitrine und dann zum riesigen Regal, das die gesamte Länge des Raums einnimmt. „Schon immer habe ich Gegenstände gesammelt, die mich faszinieren“, sagt sie. … Den gesamten Artikel finden Sie in Ausgabe Nr. 30 von The Weekender.

Fotos: Federico Floriani.

#MaddalenaSelvini#design#productdesign#Produktdesign#Gestaltung#Mailand#Milan#TheWeekender#Interior#crafts#Handwerk#DAE#Designerin#femaledesigner#Gestalterin

0 notes

Text

Public Restrooms need to become Safe and Accessible for Everyone

Written in both German and English, and published on the weblog of Depatriarchise Design, 31 July 2018.

Way beyond the scope of the signage, the current design of public restrooms is problematic. It discriminates against the majority of the population.

Public toilets as we know them in our Western society today are designed around the segregation of people into “men” and “women”: before entering, we have to decide based on their respective signage between the facilities for male and those for female users. Whichever door we go through, we generally find ourselves in a large space containing multiple washbasins and cubicles (and, in the men’s, often a number of urinals). If a third door is present, it usually bears a pictograph of a person in a wheelchair – a sign that, when set against the other two, seems to suggest people with disabilities have no gender – and leads to a room with facilities including a wheelchair-accessible washbasin for disabled users. Way beyond the scope of the signage, the design of public toilets is problematic – with those for the disabled for instance frequently falling far short of the promised accessibility.

Many questions come up: Why do some buildings offer fewer restrooms for women than for men? Why does the design of public restrooms treat women and men unequally? Why are baby change units mostly placed in women’s restrooms? Are there no fathers with babies who need such a unit? What should they do? Why are accessible bathrooms often locked and the keys out of reach? How should menstruating people manoeuvre the spatial segregation of toilet and washbasin? What about those who identify neither as male nor female? And those whose do not conform to gender stereotypes in their appearance? The current design of our public restrooms, in fact, discriminates against the majority of the population.

… — Read the complete article on Depatriarchise Design.

Und hier geht es zur deutschen Version: https://bit.ly/2Ouevuo

Cover image: Activists of the initiative “People in Search of Safe and Accessible Restrooms” (PISSAR). Image from the publication That’s Revolting! Queer Strategies for Resisting Assimilation.

#design#architecture#publicrestrooms#gender#genderneutral#accessible#feminism#disabled#safe#heteronormativity#menstruation#woman#LGBTQI#trans

0 notes

Text

ROM

Seit Mai 2018 bin ich Mitglied im Redaktionsteam von ROM, einem deutschsprachigen Gesellschaftsmagazin mit Schwerpunkt Digitalisierung. / Since May 2018 I am a member of ROM’s editorial team. ROM is a German-language magazine with a focus on society and digitalisation.

Magazine spiegeln den Geist der Zeit wieder, in der sie erscheinen. ROM begleitet eine Entwicklung, die immer noch am Anfang steht – trotz großer Fortschritte. Künstliche Intelligenz und Automatisierungen beeinflussen die soziale Realität vieler Menschen; die Aufzeichnung von Daten ermöglicht Prognosen zum Klimawandel; Angebote wie Airbnb verändern die Städte und die Art, wie wir in ihnen leben – das sind alles Veränderungen, die sowohl neugierig machen als auch kritisch betrachtet werden müssen. Das ist die Aufgabe eines Gesellschaftsmagazins – eines, das es mit diesem Fokus vor ROM noch nicht gab.

Ein Festwertspeicher oder Nur-Lese-Speicher (englisch: read-only memory, ROM) ist ein Datenspeicher, auf dem im normalen Betrieb nur lesend zugegriffen werden kann, nicht schreibend und der nicht flüchtig ist. Das heißt: Er hält seine Daten auch im stromlosen Zustand. (Wikipedia)

ROM erzählt von Menschen und ihren Lebensrealitäten in einer digitalisierten Welt – und den Veränderungen darin, den Widerständen, den Visionen. ROM ist keine Fachzeitschrift. Denn die digitale Gesellschaft ist keine Parallelgesellschaft, in der sich nur sogenannte „Nerds“ aufhalten – sie ist die Gesellschaft.

In der ersten Ausgabe erzählt ROM von virtuellen Realitäten, durchlässigen Filterblasen und Cryptorave-Partys. Es geht um Privatsphäre als ein Menschenrecht und um Trolle, die Ziele der Neuen Rechten unterstützen – zudem legt Digitalisierungs-Staatsministerin Dorothee Bär Hintergrundinformationen zu ihren Instagram-Bildern offen. Und es geht um sehr viel mehr: ROM ist insgesamt 164 Seiten stark.

www.rom-mag.com

#Magazin#magazine#ROM#society#Gesellschaft#Digitalisierung#Lebensrealitäten#Redaktion#editorialteam#editor#Redakteurin

0 notes

Text

Closer Looks at Beyond Change: Supporting Structures

Written in English and published on the weblog of Depatriarchise Design, 7 May 2018.

From 8 to 10 March 2018 the FHNW Art and Design Academy in Basel hosted the design conference Beyond Change, organised by the Swiss Design Network and interested in the impact of design within current social and political landscapes. Here, Depatriarchise Design co-created the space Building Platforms together with Decolonising Design and Precarity Pilot. I wrote this piece as part of Depatriarchise Design’s series of Closer Looks at the conference.

A heart pumps blood through the veins of a body to provide all of its cells with oxygen. Building Platforms was intended as the heart of Beyond Change. The discourses that we raised in our conversations at Building Platforms can be described as the oxygen for the conference, they kept – and still keep – it alive.

It was here, in the foyer of the conference building, where members of the three platforms Decolonising Design, Precarity Pilot and Depatriarchise Design physically met for the first time (besides from a dinner on the day before the conference started). Building Platforms was imagined as a safe and welcoming space in which everyone, with or without a conference ticket, could participate in the and conversations or just meet up and have informal discussions with friends, colleagues and members of the platforms, rest on a sofa while having coffee and cake or browse through the library that had been collaboratively curated by all three groups.

A simple scaffolding functioned as a symbol for the process of building the three platforms and their collaboration. At the same time this supporting structure offered food and drinks, as well as the collection of books and magazines on the ground and deckchairs on top, to enable people to float above the heads of everyone else. The scaffolding was complemented by corner sofas with cushions. In contrast to the chairs in the auditorium and the other official conference rooms, the stools at Building Platforms could be moved around and be arranged freely, just as needed. There was no stage. During workshops the speakers and moderators were sitting among everyone else, even on the floor. By removing these physical and spatial hierarchies the space encouraged a greater exchange. The audience was invited to actively participate, to not only comment and ask questions, but to share their experience, knowledge and opinions to learn with and from one another.

Before new structures can be built, those existing ones that do not work need to be analysed and carefully deconstructed. While the Decolonising Design group created a space to disentangle and understand the political complexities of design as both a product and a producer of colonialism and coloniality, Precarity Pilot addressed in their conversations the working conditions of designers within a capitalist economy. Depatriarchise Design initiated discussions that focused on deconstructing two systems – design education and “innovative design” – followed by a re-thinking and attempts to re-formulate them through a feminist perspective.Due to restrictions like the design of the auditorium and comparable presentation rooms (chairs have to be aligned and need to face the stage), the great amount of people in the audiences and fixed time slots, the keynote lectures and the main program of Beyond Change took a different shape than the conversations in the foyer. Even though similar topics were addressed, our sessions were done with other methods. The structures were more hierarchical, with speakers and moderators on stage, a focus on presentations and some time at the end for comments and questions from the audience. Since people needed a conference ticket to sit in the audience of the main program, these audiences also looked different than the ones at Building Platforms.

Like the scaffolding, a curtain made out of space blankets did not only function as a symbol for safety and warmth and a design that supports people in regaining strength and energy. It also separated the area of Building Platforms from the rest of the foyer and shielded it from the busyness of the conference. It allowed for the creation of a safe haven in which people could reflect on everything that happened on the outside.

Space blankets are made of heat-reflective thin plastic sheeting and are normally used on the exterior surfaces of spacecraft for thermal control as well as by people. But next to reducing the heat loss of a person’s body, the metallic surface of space blankets also flashes in the sun. This means it can also be used as an improvised distress beacon for searchers and as a method of signalling over long distances to other people. We are convinced that Building Platforms was only the beginning of enriching and rewarding collaborations between the platforms and their members. Even though the spatial representation of Building Platforms existed only temporally, its signal has the strength to travel long distances and to allow new allies to find and join us.

Photos © SDN, Samuel Hanselmann.

Further readings:

Closer Looks at Beyond Change: Accessibility and the Demographics by Maya Ober, https://bit.ly/2KmnZWE

Closer Looks at Beyond Change: What Can a Design Conference Do? by Benedetta Crippa – Part 1, https://bit.ly/2re9tYR

Closer Looks at Beyond Change: What Can a Design Conference Do? by Benedetta Crippa – Part 2, https://bit.ly/2JVewEM

#BeyondChange#DepatriarchiseDesign#DecoloniseDesign#PrecarityPilot#Design#Structures#SupportingStructures#DesignConference#Feminism#BuildingPlatforms#Construction#Deconstruction#SpaceBlankets#Scaffolding

0 notes

Text

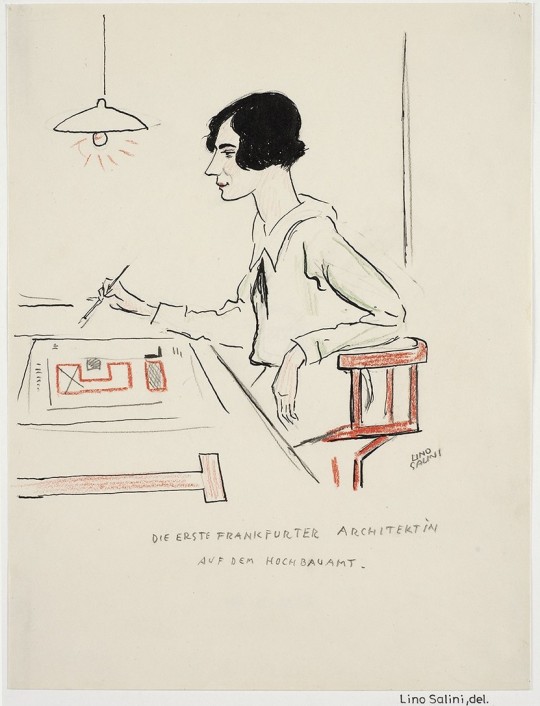

Exhibition Review: Frau Architekt

Written in English and published on the weblog of Depatriarchise Design, 22 Oct 2017.

The exhibition Frau Architekt [Mrs. Architect] currently on show at Deutsches Architekturmuseum (DAM) [Museum of National German Architecture] aims to celebrate “over 100 years of women in architecture”. Curated by Mary Pepchinski and Christina Budde it presents 22 portraits, project examples and personal stories of women who have significantly influenced architecture in Germany or are currently shaping it. The research is well-elaborated, the material original and the knowledge absolutely relevant and crucial to exhibit. But still, – a lot of questions come up: Why does a museum in 2017 still have to show an exhibition solely about female architects? Isn’t it high time to implement all the knowledge about women architects into the general discourse about the discipline?

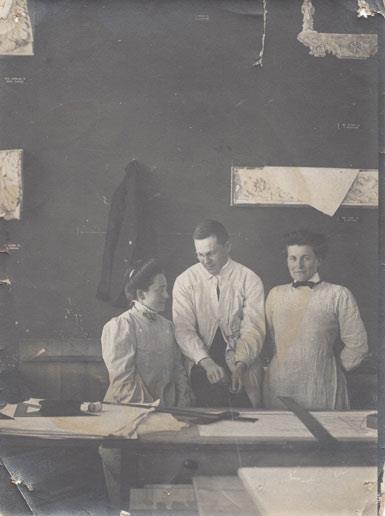

Therese Mogger was 25 years old when she divorced her husband, placed her three sons in boarding school and decided to study architecture. Without her family inheritance, these steps would have surely been impossible – it was the year 1900 and life for women in Germany who wanted to go their own way was anything but easy – even for the wealthy and privileged among them. Shortly after Bavaria had allowed women to attend universities as auditors beginning in 1904 and to matriculate in 1905, Mogger became a guest student. She took classes in architecture at the Technical University of Munich and later became one of the first German female architects, building a great variety housing that served the needs of a diverse urban population.

Image: Elisabeth von Knobelsdorff and Therese Mogger at the Technical University of Munich, 1909/10. Photo: Weber-Pfleger.

The exhibition Frau Architekt [Mrs. Architect] currently on show at Deutsches Architekturmuseum (DAM) [Museum of National German Architecture] aims to celebrate “over 100 years of women in architecture”. Curated by Mary Pepchinski and Christina Budde it presents 22 portraits, project examples and personal stories of women like Therese Mogger who have significantly influenced architecture in Germany or are currently shaping it.

The curators went through archives and conducted in-depth original research. Even though their findings are arranged in chapters, each presenting one architect, they do not simply tell the life story of each woman: photographs, models, and newspaper articles also give insights into the respective time they lived in. For example issue 31/32 of the architecture magazine Bauwelt from 1979, dedicated solely to the topic “Frauen in der Architektur –: Frauenarchitektur?” [“Women in Architecture –: Women Architecture?”], can be flipped through and read in the exhibition space.

Image: Bauwelt, issue 31/32, 1979, “Frauen in der Architektur –: Frauenarchitektur?” [“Women in Architecture –: Women Architecture?”].

The research is well-elaborated, the material original and the knowledge absolutely relevant and crucial to exhibit. But still, – a lot of questions come up: If already in 1979 Bauwelt published a whole issue dedicated to women in architecture – why does a museum in 2017 still have to show an exhibition solely about female architects? Isn’t it high time to implement all the knowledge about women architects into the general discourse about the discipline? Why having an issue or an exhibition dedicated to female architects every couple of years, but ignore them in the daily editorial and curatorial routine?

The danger of dedicating an exhibition solely to female practitioners is that their work gets, again (just like outside of the museum), marginalised. To present them through the perspective of their gender and sex as “women architects” means to reproduce the idea of a category that is subordinated to “architects”. But what do these women have in common – apart from the fact that they had to fight for their education, for their place in the discipline, and for being remembered, because of being female in a patriarchal system? They are so much more than women architects – their interests represent a great variety, so do their talents, styles, projects, political views, and clients. To show their work primarily through the lens of their sex doesn’t do justice to them.

Image: Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky: „Die erste Frankfurter Architektin auf dem Hochbauamt“ [“The first female architect at Frankfurt’s Building Department”]. Portrait: Lino Salini.

Apart from this: Who is most likely to visit an exhibition solely dedicated to women architects? People who are interested in architecture and feminism – so those who are already aware of the issue(s) at stake. But people who generally ignore women architects probably won’t change their minds and visit this exhibition. And if so, they will certainly perceive it just as it is presented: as one more side aspect of the architecture that they already know. It is not even likely for visitors to the museum to end up in the exhibition by accident since it is shown in more or less closed space on the first floor.

Frau Architekt makes clear that the knowledge of how to research the work of women architects is there and also the experts are there. The logical next step is to implement the work of female architects into the “normal” exhibitions of museums and to, by doing so, challenge the fact that until now exhibitions dominated by male practitioners are standard while the work of women gets often marginalised.

Image: Employees at the studio of Ingeborg Kuhler. Photo: Büro Ingeborg Kuhler.

If it is difficult to find women architects in fields like Brutalist architecture – the museum’s next exhibition will be “SOS Brutalism: Save the Concrete Monsters!” – this can be discussed within the frame of the respective show. Even though Alison Smithson, for example, was one half of one of the most influential Brutalist architectural partnerships in history, the aesthetical and functional values that the style fosters exclude women in a structural way: Brutalism can be described with adjectives like bold, dramatic, monstrous, massive, monumental, scientific, and cold. Patriarchal logics (still rules the society in which we are living) attributes “femininity” to the oeuvres of female architects, linking them to nature and depicting as fragile, subtle, warm, instinctive and emotional. The question to what extent this statement is true could be analysed in one of the show’s chapters.

However, there are surely other topics that offer more possibilities to include women architects. It’s absolutely possible to identify “new” themes, one just has to look close enough. Housing for military families, for example, is a theme that is being touched on in Frau Architekt: Marie Frommer, who had to move to the US in order to escape Nazis, was active in this field. Another topic could be the design of planetariums: Gertrude Schill built planetariums for the company Zeiss. And how about big visions in architecture? This one could include Merete Mattern’s imaginative unbuilt designs.

Image: Merete Mattern, Herta Hammberbacher and Yoshitaka Akui, Contest Ratingen-West, view drawing, 1966. (Image: DAM).

I would also love to see an exhibition that analyses the role that women’s organisations play(ed) in supporting female architects. Or a whole show on Iris Dullin-Grund and her work, since her oeuvre combines many different aspects: great visions despite post-war scarcity, architecture and Socialism, big scale projects and very little money. Her housing constructions in the GDR, her design of the House of Culture and Education in Neubrandenburg and her innovative master plan for the whole region are inspiring and raise questions like: To what extent are these buildings still used today? And what can we learn from her designs for our current time? Since she is still alive, in-depth interviews with the architect herself could be conducted – the short video shown in the exhibition would only be the first step.

Image: Iris Dullin-Grund: House of Culture and Education in Neubrandenburg. Photo: Veranstaltungszentrum Neubrandenburg.

Apart from this, wouldn’t it be even more exciting if a museum like DAM would question established categories and even start proposing new ones? Feminist and post-colonial theories could serve this purpose very well.

If the museum is serious about celebrating female architecture, it has to implement the knowledge and the way of thinking that is being presented in Frau Architekt into each and every show that it is going to do in the future. If the institution aims to truely challenge the fact that “architecture is still a man’s world” (as it observes in Frau Architekt), it has to curate exhibitions in line with feminist and postcolonial thinking and to include more subversive contents. And it has to look at the social processes and to expose the marginalized to contribute into a new stream of curatorial reality.

No doubt, this is hard work and a task that will probably never be completed, but with doing this, the museum would elevate itself from merely being an observer who occasionally gives insights into findings in a closed space, to an ally who actively contextualises information and works on changing the situation by breaking down walls and bringing knowledge into all the other rooms of the institution and therefore all other areas of the discipline. Not only would the museum use its knowledge in a more constructive and responsible way, it could earn a very good reputation: It could prove itself in a truly critical curatorial approach that includes feminist theory and applies it in its practice, and become known for its courageousness, thoroughness, expertise, and vision.

The exhibition Frau Architekt is on show at Deutsches Architekturmuseum, Frankfurt am Main until 8 March 2018. It is accompanied by an extensive program including lectures, discussions, and events.

Cover image: Gertrude Schill, “Spacemaster” for Zeiss, Tripoli, 1980. (Bild: DAM)

#architecture#femalearchitect#women#curating#exhibition#review#design#criticism#designcriticism#womeninarchitecture#frauarchitekt#deutschesarchitekturmuseum#frankfurt#gender#diversity#theresemogger#dullingrund#meretemattern#ingeborgkuhler#schüttelihotzky#bauwelt#frauenarchitektur#gertrudeschill#brutalism#femininity#alisonsmithson#DepatriarchiseDesign

1 note

·

View note

Text

Forging New Identities

Written in German, published in German and English (translated by Iain Reynolds) in the printed issue of form 274, Nov/Dec 2017.

Hijab and white Nike Air Force sneakers are not mutually exclusive, that’s the message being sent out by the contributors of the Modest Route Instagram account, by Frankfurt-based 21-year-old Amira Haruna and her Ami Coco blog, and by numerous other young women. These women are looking at today’s globalised world and are developing their own identities, without being slaves to lifestyle magazines, fashion chains, custodians of tradition, preachers or anyone else who might try and tell them what they can or cannot wear. Within fashion itself, a number of young designers have broken through with work that aims to give these women yet more scope for self-expression. How is that work helping women to develop their own identities and how are its creators positioning themselves as designers?

– Read the full article in the printed issue of form 274, Nov/Dec 2017.

Image: Iman Aldebe, Eco Luxury, photo by Anton Renborg

#design#designmagazine#form#formdesignmagazine#form274#modestfashion#fashiondesign#hijab#selfexpression#islam#women#feminism#femaledesigners#identity#imanaldebe#neslihankapucu#hanatajima

0 notes

Text

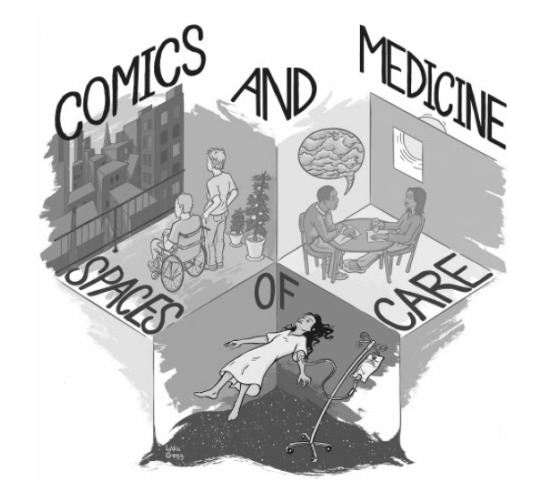

Pathographics

Written in German, published in German and English in the printed issue of form 274, Nov/Dec 2017.

In the world of medicine, both physical ailments and mental illnesses are often described using scientific and technical terminology; yet literary texts and images are frequently better at conveying the sufferer’s own inner perspective. Comics and graphic novels, for example, are an excellent way of communicating personal insights into liminal experiences both physiological and psychological. They have the potential to promote empathy and to facilitate dialogue between nursing staff, carers, and doctors on the one hand and patients and their families on the other. The team of the interdisciplinary research project Pathographics headed by Irmela Marei Krüger-Fürhoff, professor of German language and literature at the Freie Universität Berlin, is currently studying the aesthetic and political aspects of personal accounts of sickness and frailty in today’s comics and literature.

– Read the full article in the printed issue of form 274, Nov/Dec 2017.

Image: M.K. Czerwiec, Ian Williams, Susan Merrill Sqier, Michael J. Green, Kimberly R. Myers, Scott T. Smith, extract of “Graphic Medicine Manifesto”

#design#comics#illustration#comicsandmedicine#pathographics#form#formmagazine#formdesignmagazine#form274#graphicnovels

0 notes

Text

Bountiful Bangers

Written in English and published in the printed issue of DAMN 64, Sep/Oct 2017.

The sausage is one of humankind’s first-ever designed food items, according to designer Carolien Niebling. It dates as far back as 3300 BC and was originally created to make the most of animal protein in times of scarcity. Today, England alone has over 470 different types of breakfast sausage, and in Germany, there are laws that dictate specific rules for the making of sausages. However, the world is facing a serious shortage of protein-rich food: meat will become scarce because of over-consumption.

Niebling wondered if the sausage could be “a medium to eat less meat in the future”, and after completing her Master’s in Product Design at ECAL, she initiated a long-term research project called The Future Sausage. Niebling catalogued different types of sausages, their various means of construction, and the types of skins that can be used. She also researched the lesser-known ingredients as well as the alternatives, and investigated their potential.

These results were formulated into a matrix that summarises all the categories and elements. Teaming up with a molecular chef and a master butcher, she created different types of sausage that contain less meat or no meat at all. Insect Pâté, for instance, is a sausage made out of insect flour, pecan nuts, and carrot juice, along with various spices. This sausage contains no meat, unless insects are considered as such. Fruit Salami, though, consists entirely out of fruit, with a structural base of hazelnut and almond flour.

A ground-breaking project, it won the Grand Prix of the Villa Noailles Design Parade. Having already successfully crowdsourced the money to publish a book, Niebling now intends to start a series of workshops for butchers. She aims to show that a future without meat is actually not a threat but a chance for butchers to use their machines and expertise to produce ‘future sausages’.

Images: Carolien Niebling

#design#damn#damnmagazine#sausage#insects#vegetariansausage#historyofsausage#designwriting#butcher#designer#future#futuresausage#carolienniebling#ecal#damn64

0 notes

Text

Welcome to the Protest Archive

Written in German, published in German and English (translated by Iain Reynolds) in the printed issue of form 273, Sep/Oct 2017.

The purpose of an archive is to document past events and provide access to knowledge. After all, anyone wanting to understand themselves and their community – and to have a say in its future – needs to be familiar with the past. Archives that collect material from protest movements, though, are not just of benefit to the activist community. Besides preserving objects, political ideas or aesthetic trends, they also serve to address broader questions: How do communities acquire and pass on knowledge? How do they design collectively while still promoting individuality? And what alternative means of making things exist outside of established businesses and markets?

— Read the complete article in the printed issue of form 273, Sep/Oct 2017.

Cover image: Interference Archive, New York, Soñamos Sentirnos Libres – Under Construction, exhibition highlighting the potential of mobile print power.

#form#design#interferencearchive#protest#protestarchive#designandprotest#activism#graphicdesign#form273

0 notes

Text

“Realignment of the daily routine and of the interior furnishings”. Revisiting design criticism by Alix Rohde-Liebenau.

Written in English and published on the weblog of depatriarchisedesign, 27 June 2017.

After the end of World War II Germany had to face the consequences of the Nazi regime’s actions – which included millions of homes that had been destroyed or damaged during Allied bombings. The municipality of West Berlin came up with an open-call for ideas “Berlin plant” [“Berlin plans”], inviting both architects and citizens to participate. One of the questions was: “How can a standard family of 4 live on 65 sqm?” The female journalist and writer Alix Rohde-Liebenau (1896–1982) contributed a comprehensive piece of design criticism, questioning and challenging the premise of the open-call itself.

— Read the complete article on depatriarchisedesign

(Cover image: Collage from a booklet designed by Georg A. Neidenberger for the Internationale Bauausstellung [International Architecture Exhibition] in Berlin, 1957.)

#DepatriarchiseDesign#AlixRohdeLiebenau#DesignCriticism#DeutscherWerkbund#GermanDesign#BerlinPlant#Architecture#FemaleDesignCritic#WomenDesignHistory

0 notes