Link

Influencer culture makes quick, sensationalized opinions seem more valuable than those that are researched, nuanced, and grounded in facts. A quick catchy post or a TikTok video with a compelling narrative can easily attract millions of views. We are used to that easy-to-digest format now, and nuanced, length, data-filled takes just don’t hold our attention much…if they even manage to grab it. There’s a blurred line between entertainment and truly informative takes.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

What if Paul is saying there is not one identity that renders all others moot, but rather that in the very giving up of all of our identities, we identify directly with Christ? Here Christianity is not another positive worldview mythology that can be placed alongside all others, but is rather the name we give to the act of laying these down. The Christian community is not, then, distinct because it embraced yet another identity, but is rather is unique in the way that its members lay down the other identities that would otherwise define them. ... Paul saw the cross as the event that opened up a way of living that was an alternative to the dominant principles of this world. — Peter Rollins, Insurrection

0 notes

Quote

In conversation with [the foolish person], one virtually feels that one is dealing not at all with a person, but with slogans, catchwords and the like that have taken possession of him. He is under a spell, blinded, misused, and abused in his very being. Having thus become a mindless tool, the stupid person will also be capable of any evil and at the same time incapable of seeing that it is evil.

When does an intellectual failing become a moral one? Bonhoeffer's theory of stupidity

#Bonhoeffer#conformity#arrogance#pamphlets#social justice#society#outrage culture#the shouting class

0 notes

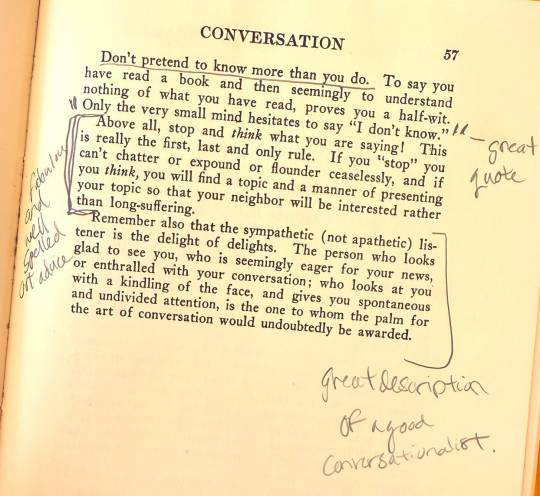

Photo

(via Etiquette Throwback 1922: Emily Post, Etiquette, Talking Too Much)

4 notes

·

View notes

Quote

One way the Stoics reduced their wants was by appreciating what they already had. Often we chase new things because we forget the value of old things, so if we focus on rediscovering and re-enjoying what we’ve begun to take for granted—the simple, essential things like our health, homes, and loved ones—then we fill the void in our hearts that would otherwise lead us to endlessly chase dopamine hits.

Gurwinder on Substack

1 note

·

View note

Link

The only slight hiccup in this plan is that if your husband doesn’t do the tasks, the system falls apart.

It’s so frustrating to me that we’re still talking about this. Why are we still coddling men, and patting them on the heads and saying “aww, pwecious thing. he simply doesn’t know how to do it”? It’s so condescending to men. It robs them of their agency and their investment in the household, and it takes women to the absolute breaking point.

I do think a small amount of the issue can be cut out by doing less as a family and understanding that in some seasons, you can’t afford to do 100% of the things you want to do, and you’ll need to simplify life. Who says that during the busiest and most fraught season of your life, you get to go to 5 workout classes a week and your husband gets to go out with his buddies for 12 hours every Saturday? You’re not entitled to any of that. Take on exactly as much as you, as a family, can administratively and practically handle. And no more.

But Rodsky is right about boundaries—until consequences exist for utter feigned helplessness, this will continue. And I don’t think it’s men 100% of the time, but whoever the lazy party is, why would they buck up when so far they’ve been enjoying all the comforts of this life while putting nothing in? Sounds like they’re being rewarded for trodding upon the goodwill of their spouses and children, who they’re purported to “love.” Unfortunately, those boundaries often fall on moms to enforce, just like everything else.

0 notes

Link

We live in a secular age, and I would consider myself a secular person. I’ve read books about the witch trials and persecution of heretics, and hold no romanticised views about organised religion. But I can tell you that as a new mother, seeing those images reflected on the walls of the Louvre made me feel an immense gratitude for our cultural history, as well as a sense that something important may have been lost. In my life, I have gained more recognition and prestige from being a columnist for The Australian, and founder of Quillette, than I ever have from being a mother—despite the latter being more important. The young mother today is largely isolated and invisible—or if she is visible, she is a minor nuisance, pushing a pram around that gets in other people’s way.

This Christmas, my message is to remember what the Renaissance masters understood: that there is something worthy of reverence in the relationship between mother and child. While we may no longer seek the sacred in paintings, we can still see the simple truth that Raphael and Botticelli captured—in witnessing the care of a mother for her child we can look through a window into the sublime.

0 notes

Text

0 notes

Text

“This questioning of the meaning of being, and dying and being, is behind the telling of stories around tribal fires at night; behind the drawing of animals on the walls of caves; the singing of melodies of love in spring, and of the death of green in autumn. It is part of the deepest longing of the human psyche, a recurrent ache in the hearts of all God’s creatures.” — Madeleine L’Engle

0 notes

Text

…something called the Dartmouth Scar experiment; I think we talked about it a few episodes ago. They had this experiment whereby they had these lovely young women and they told them it was an experiment to see the effect of a scar during an interview. And so they gave each of the lovely young ladies a scar. But just before they entered the interview room, they said ‘We need a touch-up, a quick touch-up.’ And in fact it was not a quick touch-up; they completely removed the disfiguring scar. And so the women went into the interview room perceiving themselves as scarred when, in fact, they were not. And when they were questioned about the results, many of them said ‘Well I could see he was biased against my scar, I could tell he was focused on it,’ which shows you the power of self-perception. So when we do the whole woke-woke thing, we’re creating a Dartmouth Scar Experiment on a wide scale, on a wide scale with unsuspecting black kids. — Winkfield Twyman, The Free Black Thought Podcast Ep. 76, Free Black Thoughts with Bowen & Twyman, Ep. 13

0 notes

Text

"Thou hast formed us for Thyself, and our hearts are restless till they find rest in Thee"

-- St. Augustine

0 notes

Link

I didn’t mean to imply that I was a capital “C” Conservative, it’s more that I have a conservative temperament. I would say that, as far as I can make out, a conservative temperament has something to do with a deep understanding of the inherent value of the world, and its vulnerable and precarious nature. It is suspicious of the impulse to tear things down, dismantle things, cancel things, burn things to the ground, rather it’s more naturally inclined toward cautious, incremental change, because we need to be careful with the world. The conservative understands about loss and about grief. I’m certainly open to new things, but with an appreciation of what has gone before and a melancholy understanding that it is a lot easier to tear things down than to build them back up. But, at the end of the day, I think conservatism is an aspiration, it is something we should strive for—a society that works well enough that it is worth conserving.

...

What we believe in is a serious matter. It is a condition of being. It is not something you can hide, especially if you are a songwriter because your preoccupations rise to the surface and find their way into the songs. That’s the beauty and danger of certain songs, they reveal a great deal, not just to others, but to yourself. So, whatever my beliefs may be, they exist in what I create. They are there for all to see. Of course, in The Red Hand Files I do my best to write about religious matters with some nuance, you know, about my belief, but also my unbelief. Religious ideas preoccupy me, for sure, as they always have, for as far back as I can remember. I don’t need it pointed out that there is something absurd about spending vast amounts of time contemplating the nature of something that quite possibly doesn’t exist. The thing is, songwriting and faith are inextricably linked, for me, I recognise one in the other. I find writing words to be dependent on a readiness to perceive what are essentially tenuous, softly spoken ideas, that reveal themselves, like God, as intimations, as ghost-like abstractions, as mysteries. And like God, a song rarely comes fully formed, without a struggle, declaring itself. So, in that respect, as a musician and songwriter, matters of faith are second nature, and well, impossible to ignore.

0 notes

Text

i think all quiet on the western front and the lord of the rings are in direct conversation with each other, as in theyre the retelling of the same war with one saying here’s what happened, we all died, and it did not matter at all and another going hush little boy, of course we won, of course your friends came back

79K notes

·

View notes

Quote

We all like to imagine ourselves as the good guys in history. It is fun to fantasize about holding the line at Harper’s Ferry or refusing to ratify our compromised Constitution. It’s also very easy. ... 'History is as complicated as people are,' Munden says. 'We don’t have to come from a place of ‘people are right or wrong,’ but rather from a place of what we learn from them about how we can behave differently.'

The ‘Safe Space’ Where America's History is Debated in Real Time - POLITICO

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

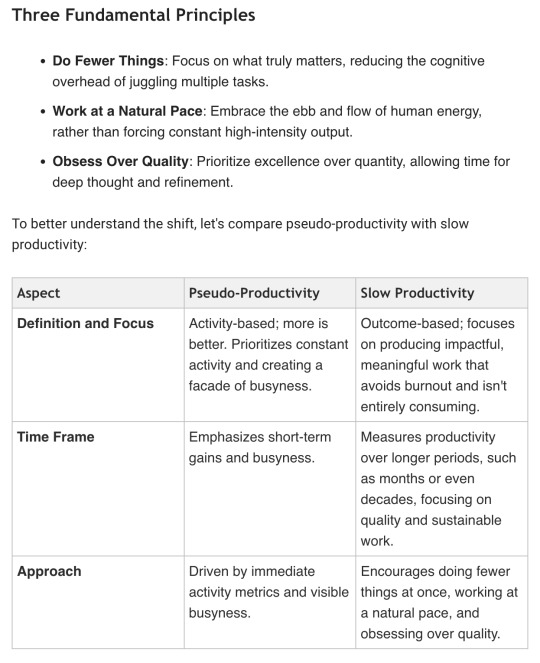

Slow Productivity basics, as summarized by Iwo Szapar in "Have you heard about 'Slow Productivity'?" from the Remote-First Institute

2 notes

·

View notes

Link

0 notes