#yogH

Text

#What does Gita say about KeepingFASTS?Shrimad Bhagavad Gita Chapter 6 Verse 16Na#ati#ashnatH#tu#yogH#asti#na#ch#ekaantam#anashna

0 notes

Video

youtube

तपस्या करने से क्या फल मिलता है? Sant Rampal Ji Maharaj Satsang

0 notes

Text

#गीता_तेरा_ज्ञान_अमृतShrimad Bhagavad Gita Chapter 6 Verse 16Na#ati#ashnatH#tu#yogH#asti#na#ch#ekaantam#anashnatH#Na

0 notes

Note

Examples of names with yogh in them?

A lot of the time, when movable type came in, the yoghs were mistaken for Z and so they were replaced most frequently with Z. Trouble is that the yogh had a whole mess of pronunciations including silent, not to mention the way language pronunciation gently slides sideways over time. Ones I'm most familiar with and have used before are:

Menzies - pronounced Mingis

Culzean - pronounced Culain

Cockenzie - pronounced Cockenny

MacFadzean - pronounced MacFadyen

Dalziel - pronounced Deeyel

The bold ones are family names, the others are places.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

i did say i was gonna do the letter bracket when i get desktop posts but turns out i can only post from the legacy editor which doesn't have polls. such malarkey

ABCDE GHI KLMNOP RSTUVW Y

21/26

#and per se and#i know i physically can do it on mobile but it's a pain in the ass#i think i was also including ampersand eth thorn and yogh? i dont rember though#oh i found the post it was also wynn and æ

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

My finest moment

#university challenge#worth spending four years at uni for#timehop#defunct English letters#yogh eth thorn I think it must’ve been

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

I comawnde alle þe ratones þat are here abowte,

Þat non dwelle in þis place, withinne ne withowte,

Thorgh þe vertu of Iesu Crist, þat Mary bare abowte,

Þat alle creatures owyn for to lowte,

And thorgh þe vertu of Mark, Mathew, Luke, an Ion –

Alle foure Awangelys corden into on,–

Thorgh þe vertu of Sent Geretrude, þat mayde clene,

God graunte þat grace

Þat non raton dwelle in þe place

Þat here namis were nemeld in;

And thorgh þe vertu of Sent Kasi.

Þat holy man, þat prayed to God Almyty

For Sakthes þat þei deden

Hys medyn

Be dayes and be nyʒt,

God bad hem flen and gon out of euery manesse syʒt.

Dominus Deus Sabaot! Emanuel, þe gret Godes name!

I betweche þes place from ratones and from alle oþer schame.

God saue þis place fro alle oþer wykked wytes,

Boþe be dayes and be nytes! et in nomine Patris et Filii et Spiritus Sancti

#i have a book of middle english texts and this one made me laugh#also those ezhes should be yoghs but i don't have a keyboard command for that but i do for ezh

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

þhe wummen want me for mi ȝorȝeouse lettering

#i need a tag to be obnoxious about my excitement for middle english (that you all can then mute)#i learnt how to type thorn so that's great but i have to copy paste yogh like a fucking poser

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ƿhenever þou kænst, adorn þy speech wiþ ƿordz like "þou" ænd "þee".

#i'm hoping to end up writing a post that gives me an excuse to use yogh#technically i could have already used it but i have specific situations in mind for it

1 note

·

View note

Note

hey man, hope you're well.

bit of an arb question for ya - and i totally understand if you'd prefer to skip it because time & effort etc etc - but if you're game i'd really be interested in your thoughts on the ᛇ rune.

thanks dude, appreciate it. even if you nope the hell outta this ;)

cheers

I'm sorry that I left you on read for months. The honest truth is that at first I had trouble reigning in the scope of my response and knowing when to cut myself off from researching (there are still things I've yet to read that could influence my take on this), and then I got busy and just straight up forgot. I'm gonna give you a response that will be completely unsatisfying but hopefully better than no response.

For more on the details of the different linguistic theories about the rune that I only briefly mention below see "The Yew Rune, Yogh and Yew" by Bernard Mees.

The problem I have talking about this rune is that any examination of it produces a lot of questions, all of them very interesting, and some which call into question what we can know about runes in general. Talking about this rune is like untying a knot where every time you loosen a section another one tightens. There are a lot of people on the internet who claim to have figured it out but who have not realized that the conclusions that must logically follow are not things they're likely to accept. It's hard to talk about it at all without saying a lot. This is entirely unlike ᛈ *perþō(?) *perþrō(?) where it simply becomes a dead end quickly due to lack of evidence. With ᛇ there is an extreme overabundance of mutually-conflicting possibility, plus a history of the rune being innovated in ways that obscures how it was used prior to that innovation.

I recognize that most people who want to talk about runes on this website are mostly interested in magical/divinatory uses. For better or worse I don't have anything to say about that, but if that's what someone's into then I urge you to at least consider that the mundane aspects of a rune form the ground of speculation about everything else, and any magical/mystical speculation should at least be inclusive of things we can see and touch. And I think that if someone chooses not to grapple with the evidence, they're actually missing out on what's actually interesting about this rune.

Even giving it a single name is loaded. In text I call it "the yew rune" but thanks to the particularities of English that doesn't work out loud. There's no possibility of writing or speaking its name without making some bold assertions about linguistics, whether one knows it or not. I think the most accurate way to give it a "name" results in this entire paragraph-length sentence:

There were a few synonyms for 'yew (tree/wood)', which may have included any or all of *īwaz, *īhaz, *īgaz, *īhwaz, and *īgwaz; that may or may not have arisen by the splitting of an earlier proto-form that is difficult to reconstruct; and which had some degree of exchangeability in some places and times; and the earliest name of the rune could have been any of these but it was also identified with one or another at different times.

*īwaz informs the normal OE word for 'yew' and the Old Norse rune ýr; *īhaz informs the OE rune īh/ēoh. Sometimes they get shoved together into *īhwaz, which on the surface is just a way of abbreviating "the above explanation"*īwaz and *īhaz", but has potential to be read at face value if you're willing to grapple with some questions regarding Proto-Indo-European, Verner's Law, maybe Germanic reflexes of laryngeals. *eihwaz is a name I see a lot but which is either definitely wrong; requires either significant reanalysis of the languages it was used to write; or undermines the use of the comparative method for reconstructing rune names at all (which, hey, maybe it should be undermined, but the consequences for the rest of the runes would be significant). Sometimes when people propose *eihwaz or anything starting *ei- they are actually intentionally saying "runes are older than Proto-Germanic" which is an argument one can make but you have to actually make it, and they are usually neglecting that at that time, the word for 'ice' was *eisa- and so this doesn't actually restore balance to the runes anyway.

The next set of problems involves its use in writing. In the earliest inscriptions we have, it's used very rarely but when it is it's indistinguishable from *īsa(z), i.e., it writes /i/. Later on, it also comes to write a consonant that was probably something like [ç], the sound in German ich, which was present in some of these languages but cannot be the first sound in a word. It would actually be pretty satisfying to argue that the [ç] sound was original, and that /i/ is a later thing coming from the principle that a rune's name should start with the sound it writes. But this is the reverse of the evidence -- are we supposed to just be okay with the idea that the rune's original usage just happened by coincidence not to produce any surviving evidence for hundreds of years, and then suddenly did?

The īh rune in Codex Vindobonensis 795, c. 798 with sound value given "i & h"

It would eventually gain other sound values too, including /k/ in some Old English sources and of course it becomes (or rather, merges with ᛉᛦ into) the /ʀ/ rune in Old Norse, then a weird multifunctional vowel rune for a bit before settling on /y/ which was its main use into modern times.

Ideally, if you lined up the questions about the reconstruction of the name in one column, and the problems in what sounds it was used to write in another, you could find overlaps and find items in each column that reinforce each other; but in reality the questions tend to multiply instead.

I have some thoughts about why most of this rarely gets discussed, even by people for whom runes are an important part of their religion. I think we have a cultural predisposition to recognized systematic order and balance as a sign of legitimacy, to the point that it even overwhelms material evidence. What this rune is evidence of isn't an original cohesive and complete system (whether or not that existed), but rather of persistent intervention over the course of a thousand years -- it cannot be understood in isolation of stone, parchment, and human hands. This is anecdotal but it seems that most people who are into runes at all are really only interested in that "original" pure unadulturated state that they suppose must have been the first iteration of runes, and view everything that comes after -- that is, all actual evidence -- as valuable only insofar as it points back toward that idealized system. But not only doesn't ᛇ do that (though admittedly, one day it might, if the right theory comes along), it shows that the way people interacted with runes over generations calls into question our assumption that the other runes do provide reliable evidence for that. I think that for most people who post about runes online or even write books about runes for a popular audience, this is in such violation of common sense that they don't find it worth consideration, and generally side with whatever one of the simple theories about it they most recently read. Even among professional linguists, most attempts to explain the rune simply aren't just neutral answers, they are expressions of panic and attempts to restore order. Admittedly, a theory could still be proposed that puts all this to rest. But the way people respond now, while it hasn't, while people habitually latch onto explanations that they clearly don't understand, is still revealing of our epistemologies.

If you want to find meaning in this, I might suggest something like this. One of the distinguishing characteristics of yew wood is its flexibility and springiness (making it so suitable for bows that ýr can simply mean 'bow' in Old Norse). Whatever the rune's earliest name was (or set of names were), it was somehow seemingly set up to stay relevant a thousand years in the future. Despite being redundant already in the earliest examples we have (maybe even when it was first used??), it found new usage for writing a [ç]-like sound (presumably *īha- was pronounced somewhere in the vicinity of [iːça]). Old Norse was eventually going to need a rune for /y/, and *īwaz was set up to produce a word by regular phonological development: *īw > ý (see also *tīwaz > Týr), and it's almost creepy how they thought to preserve that name despite needing to move it to a different graphic form, given that *elhaz/algiz worked perfectly well as the name of a rune for writing /ʀ/, but lacked a y.

[Edit: I should clarify that I don't actually think there's anything unexplainable or mystical about this -- I think it's a combination of the same opportunistic innovation that is characteristic of rune use in general and a little bit of coincidence].

So basically ᛇ is distinguished by how often it's been bent and twisted and made to fill gaps that arose as a result of language change while always maintaining continuity with its earlier forms. Its name may or may not have alternated between some closely-associated variants, but it was never changed outright, unlike a bunch of others. It exhibits a plasticity that's fitting for a rune meaning 'yew,' and it was given that name long, long before demonstrating its suitability. All this can only be seen by taking the long view, looking at how it unfolds over time, by specifically turning away from an idealized, atemporal proto-Elder Futhark.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

English language updates:

removed vowels o and e for better intelligibility with modern standard arabic

incorporated the letter hwair ƕ from gothic

re added yogh Ȝ from middle English

language now officially referred to as "the lishy lang" for some reason

removed herobrine idk

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

<W>hat Are <Th>ese Letters?: An Explanatory Post

Oka<y>, so <y>ou might be <w>onderi<ng> <w>hat <th>ose silly letters <th>at I, N.A.E., use <w>hen talki<ng> are. <W>ell, <th>is post aims to explain just <th>at.

Þþ - Þorn - A voiceless <th> sound like in þink or cloþ.

Ðð - Eð - A voiced <th> sound like in ðis or breaðe.

Ŋŋ - Eŋ - A <ng> sound like in siŋ or spriŋ. Killed by Linux.

Ƿƿ - Ƿynn - A <w> sound like in ƿise or ƿorm. Killed by disinterest.

Ȝȝ - Ȝogh - A <y> sound like in ȝes or ȝawn. Same as Wynn

I hope ðis post helped ȝou undersand my Silly Writiŋ™️. If ȝou still don't, search for "Thorn (Letter)", "Eth", "Eng (Letter)", "Wynn (Letter)" and/or "Yogh" in ƿhatever search engine ȝou use.

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Old English Runes – Latinized!

I thought to myself "What if they hadn't given up the futhorc for the alphabet, and had instead simply adapted futhorc to the Latin script?"

A a ᛫ B b ᛫ Ʌ ʎ ᛫ D d ᛫ E e ᛫ F f ᛫ G g

Ð þ ᛫ H h ᛫ I i ᛫ J j

L l ᛫ M m ᛫ Ƚ ƚ ᛫ O o ᛫ C c

Ŋ ŋ ᛫ R r ᛫ S s ᛫ K k ᛫ V v ᛫ T t ᛫ Ƒ ƒ

Ƿ ƿ ᛫ Æ æ ᛫ Ʒʒ

X x ᛫ Y y ᛫ Z z

A ᛫ B ᛫ C ᛫ D ᛫ E ᛫ F ᛫ G

Thorn ᛫ H ᛫ I ᛫ J

L ᛫ M ᛫ N ᛫ O ᛫ P

Ng ᛫ R ᛫ S ᛫ K ᛫ U ᛫ T ᛫ V

Wyn ᛫ Ah ᛫ Yogh

X ᛫ Y ᛫ Z

Ðð is "Th." To get "Sh" you write Sʎ or Sh

Æ æ is for shorter A-sounds.

Note Ƚ is an N. V is a U, like under. Wyn (Ƿ), as in "win," is a W. And Ƒƒ is a V, like violin.

And Ʒʒ (or Ȝʒ) unmodified is a throaty, stopped noise, like "Ugh!" or "Loch," but represents the rather tricksy "gh" relic, which makes up to a dozen noises in Modern English.

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

can i ask for your thoughts on ȝ my favourite letter ȝ

wish we still had it cuz we still make the sound. oh wait was that why there was a 3 on the other alphabet tournament

ABCDEFGHI KLMNOP RSTU W YZ

22/26

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reading through Liber Cure Cocorum, a Lancashire cookbook from the 1430s, and found my first usage of the letter Yogh in the wild!

Cool things about this cookbook:

1. It's got a bit of Lancashire dialect in it (t'other, t'one, etc.) that's survived to modern usage.

2. It's written entirely in rhyme.

3. It's the first written down example of a recipe going by the name haggis (hagese) using offal and herbs according to Wikipedia.

4. A good handful of the recipes start by telling you to go and kill the thing you'll be eating.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Etymology: She-Ra

What’s good, it’s time for another foray into etymology, this time featuring the resident magical alter ego, She-Ra! As you may have seen from my Larry Ditillio/Lou Scheimer quotes, the actual etymology is pretty straightforward--She, plus Ra. So we’ll cover that first, then move into homophones and proposed alternative etymologies (largely by people who didn’t know about the actual one).

Section One: She

‘She’, of course, is a third person pronoun in English, here the feminine counterpart to the masculine ‘he’ of He-Man. I’m reasonably confident y’all are familiar with the idea of personal pronouns, given we’re on Tumblr, so we’re just gonna jump right in here.

From Middle English sche <ʃeː> (~’shay’), though it could be rendered scho and ȝho (both pronounced ~‘show’) before we killed the yogh. Luckily for us, in ȝho it’s just pronounced like ‘sh’.

Don’t let the sch fool you, the c in sch was often silent in Middle English. How exactly we arrived at sche, though, is a matter of some debate. This paper summarizes most of the proposals, which has saved you all about eight paragraphs of me rambling about phonemes.

Regardless of its derivation, the vowel situation in ‘she’ is pretty weird--I’m assuming like half of you are familiar with the Great Vowel Shift, but for those that aren’t, the 15th to 18th centuries saw a.... well, great shift in vowels. It’s why so many of our words are spelled so fucked up; one day our long vowels just did an electric slide to the right & suddenly bite was pronounced like byte instead of beet. But one would expect the “e” in sche to unravel into an “o:”, not the “i:” sound we wound up with. It could be the influence of ‘he’, which would be convenient for us, looking at the word as a counterpart to the ‘He’ in He-Man, but historical phonology is a tricky beast. And it could just be an outlier--commonly used words have a tendency to mutate faster.

I think that’s enough about vowels, though. Moving on!

Section Two: Ra

Ra. Good old Ra. God of the sun, the sky, order, kings. Ruler of all three realms, sky earth and underworld. Creator of all life (sometimes). Kind of a big deal.

Not to pat Larry Ditillio on the back too hard here but it was a great choice, phonetically and theologically. There’s even a precedence for using his name as half of a compound, as with Amun-Ra, the New Kingdom’s fusion with Amun. There’s his association with the falcon, shared in MOTU by the god Zoar (and the Sorceress), but he was also usually depicted with the head of a ram in the underworld. And I mean. Skeletor’s Havoc Staff is literally a ram skull, is all I’m saying. Like Ra is a pretty incredible option, here.

A little more Egyptology, because the coincidences don’t stop there. Ra had three daughters, and since this is appending Ra to “She” and they’re all--as the “eye of Ra”--sometimes considered feminine aspects of Ra, I think it’s relevant. And funny, because all three were depicted as cats at one point or another & Catra is right there.

Hathor was goddess of the sky, the sun, music, dance, joy, sexuality, beauty, love, motherhood, queenship, fate, foreign lands and goods, the afterlife, and more! This is a bonkers number of things to be god of, but I don’t think it was ever all at once. Most consistently, she was the embodiment of the Ancient Egyptian perception of femininity. As women’s role in society changed, so did Hathor’s role in the pantheon--for good or ill.

Bastet & Sekhmet are a little more focused. Originally, they were both fearsome warriors, protectors of Egypt & specifically of the pharaoh, but over time Bastet became a gentler take on protection, often with a maternal slant as she became more associated with the house cat than the lion.

Sekhmet on the other hand was (and always would be) literally bloodthirsty. She could breathe fire, cause plagues, and almost destroyed the world once! But she was also a goddess of healing, called upon to ward off illness & injury, patron of healers and physicians alike. [holds up a picture of She-Ra] 🤌 It’s about the duality.

Alright, onto the etymology. ‘Ra’ is pretty straightforward, it’s just how we most commonly transliterate the rꜥ hieroglyphs (though he is often called Re) & Demotic script.

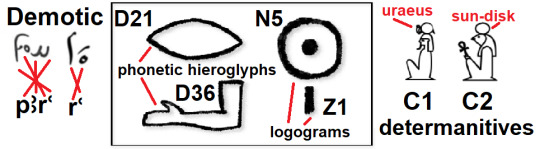

So there are three kinds of hieroglyph, right? Phonetic, like a letter in English, logographic, like a morpheme in written Chinese (which is typically logosyllabic but bear with me here), and determinative, to disambiguate meaning between homophones.

D21, the mouth, provides the ‘r’ sound, as a phonetic hieroglyph. As a logogram it could mean ‘to turn the other way’, but we’re just after the sound here.

D36, the forearm (palm upwards), gives us the ‘ ꜥ ‘, which is... okay, hieroglyphics were an abjad, right? There were no written vowels, you just spoke them. But ꜥ, ayin, was a voiced pharyngeal fricative, which is basically a semivowel (like the Y in English ‘yes’ or the W in ‘west’), which is why its use here can be spelled either ‘Ra’ or ‘Re’, because it’s not representing a distinct vowel sound. One of its descendants, ע, is usually rendered as a glottal stop in Modern Hebrew (or omitted entirely), but another descendant is the English letter O, through the Phoenician ayin. We can’t pronounce the ancient Egyptian ayin based on its derivatives, but we can take historical cues from them.

A glottal stop (like the break in uh-oh) is abrupt, right? Ayin is more like... a glide. A pause. When people make an “I don’t know” sound, that’s the sort of sound. This video is as close as most native English speakers will be able to approximate.

But I digress. We’re only halfway through! Those were the phonetic hieroglyphs, but there are other words pronounced rꜥ, so there are some logograms to help us narrow it down. Unsurprisingly, first is N5, the sun, followed by a Z1, (the numeral one), which indicates that the previous glyph is an ideogram--it’s like a one-character version of “←literally”. Now, by themselves those four glyphs could still just mean ‘the sun’, so to specify that it’s the god being spoken of, in come our determinatives.

This could be either C1, C2, C2A, C2B, or C2C. All depict a god wearing a sun-disk on his head. The C2s are all falcon-headed, and C1, while human, has an uraeus (the little rearing cobra you see on pharaohs’ headdresses and crowns) to emphasize divine authority. Some spellings outside the Unicode standard mix and match accessories, or omit the phonetic hieroglyphs entirely to rely solely on the determinatives. Generally, if you see a god with the sun on its head, it’s either Ra himself or invoking/referencing him (which was done frequently in pharaohs’ names).

Okay. Switching gears.

So hieroglyphs are kind of a bitch to write out, right? You don’t want to take the time to draw a whole little guy when you’re just making a list of supplies or something. So they invented this shit called hieratics that was basically cursive hieroglyphics, which eventually became the Demotic script! Ra was written G7-Z5-N5, (still rꜥ), or pꜣrꜥ (conventionally pronounced pa-re), with the pꜣ functioning as a demonstrative determiner to indicate that yes, they mean the god.

Section Three: Homophones

Those of you who have tried to google ‘She-Ra bible’ may be familiar with Sheera of Chronicles 1 7:24. Chronicles is the last book (split into 2 for Christian bible) of the Tanakh, wrapping up the Ketuvim with a genealogy and history of Judah & Israel. To oversimplify: David, Solomon, Babylonian exile, Cyrus the Great swoops in and lets everyone back in & okays the building of the Second Temple around 539 BCE. Only non-Jewish messiah in the Tanakh, and relevant here because the Ancient Greeks thought his name meant ‘Sun’, from Persian خور, ‘xʷaɾ‘. It’s also been translated as hero, humiliator of enemies, youth/young, and one who bestows care. It is almost certainly unrelated to C’yra (of D’riluth III), but the possibility remains until Scott answers my fucking email.

Anyway, Sheera/h. שארה (שֶׁאֱרָ֔ה, with niqqud). That ה (funnily enough, named he) is a suffix indicating a singular feminine noun, which has been applied to שאר, sh-’-r (or sh-a-r, depending on how you render the aleph. I used an A in my post on Adora with אדור but it feels weird as a infix, especially given what I did with the ayin in section 2). Let’s take a look at its definitions:

Sha’ar means to remain, to be a remnant, and its derived nouns she’ar and she’erit mean remains, residue, etc. In the Tanakh it refers almost exclusively to survivors, people or things left behind when everyone/thing else has died, often violently. Noah & his passengers on the Ark after the flood, Lot & his daughters after Sodom and Gomorrah--did y’all know the town they went to after was called Zoar? The aforementioned falcon god in He-Man? It’s a coincidence but what the fuck. Naomi and her sons in Ruth 1:3, then just Naomi in 1:5. Oh, and she renamed herself Mara like ten lines after that. Shit like this just kept happening, I had to stop looking at examples bc it was freaking me out.

She’er, meanwhile, means flesh, both in terms of flesh for consumption & one’s flesh and blood. It can also mean physical power (Psalm 78:20), but I for one assumed that shit was metaphorical. On the other hand, who am I to deny another fun little parallel with our Princess of Power? A lot of people prefer this for the underlying meaning of Sheerah’s name, since she’s explicitly someone’s daughter & it could just be like “(singular feminine) kin”. But I think that’s boring (even if the prospect of like, “Fleshella” or some shit is both objectively hilarious and kind of in line with MOTU names) and a little unremarkable to name three cities for. Did I forget to mention they built three cities named after Sheerah? #girlboss

Last of the שאר is she’or, meaning leaven (the noun, not the verb). In Modern Hebrew it’s more often spelled שאור, with a waw added in to disambiguate the pronunciation.

Onto some other homonyms, bc that was technically just one!

Shir, an anglicization of شیر, Classical & Iranian Persian for ‘lion’, one of the plurals for which is شیرها (šir-hâ), which admittedly is more like “sheer-ha” but say it out loud before you judge me for its inclusion here, huh? The singular’s also part of شیرزن (širzan, “heroine”).

There’s Macedonian and Serbo-Croation шира/šira , "must" (fermented/ing juice, not necessity).

Cira, which is Sicilian for “wax”.

شيرة and شْيَرَة, Hijazi and Gulf Arabic (respectively) for syrup, from Persian شیره. There’s a lot of Persian origins here huh. Shame Purrsia isn’t canon, could’ve had a field day.

Okay one more in Hebrew. Shira/h, שירה, is poetry, verse, singing. In Modern Hebrew shir is a song and shirah is a poem, but that distinction didn’t always exist. The other derivatives of the שׁ-י-ר stem are all related to this. You’ll note that the second letter is a yodh, not an aleph as in the above שארה, whose stem was שאר. There’s like a 99% chance that Larry Ditillio’s niece Shirah’s name is derived from this.

Section Four: Shit I’ve Seen People Claim it Means

Most understandably, I’ve seen people claiming they just stuck an S on the rejected name “Hera” and broke it in two to mirror He-Man. So just to cover our bases, Ἥρα (Hera) is of uncertain derivation. Potentially a feminine form of ἥρως (hḗrōs) or related to ὥρα (hṓra)--the former being the ancestor of our word hero, in epics specifically heroes of the Trojan War, but generally humans or demigods venerated at local shrines. The latter refers primarily to time--hours, years, seasons--and youth. The youth reading is supported by the Roman name for her, Juno, which is also of uncertain derivation, but one of those likens it to iuvenis, young (like the juve in rejuvenate).

Asherah the ‘mother goddess’. I admit I wasn’t expecting this one. Asherah (the spelling I’ll be sticking to for consistency’s sake) was, admittedly, kind of a big deal in the ancient Levant. In the interest of not going full theology essay while I’m trying to talk about names, suffice to say she was the consort of the king of the gods (El, Elkunirsa, Yahweh, ‘Amm, Baal, etc.) in quite a few religions, some of which have dropped the polytheism thing & Asherah along with it. (The others are dead).

It’s written אשרה in Hebrew, so roughly ‘sh-r-’ if I’m sticking to my aleph conventions. She was also called Athirat in Ugaritic, an extinct Semitic language ( 𐎀𐎘𐎗𐎚, ʾAṯirat), though before 1200 BCE she was almost always referred to with her full title, 𐎗𐎁𐎚 𐎀𐎘𐎗𐎚 𐎊𐎎, rbt ʾṯrt ym. This is another abjad so we gotta adlib our vowels, but most people go with rabītu, for ‘lady’. The ym could refer either to her son, Yam, or the sea which he was the embodiment of, but the middle bit is tricky. It’s her name (that Athirat), but some people think it’s derived from the Ugaritic ʾaṯr for ‘to stride’, so her full title could be translated as Lady Athirat of the Sea, Lady who walks on Yam/the Sea Dragon/Tyre (the city). However, a more recent translation derives it from the root y-w-m, ‘day’, which would make her Lady Asherah of the Day/s (or even just Lady Day).

Another epithet was qnyt ʾilm ( 𐎖𐎐𐎊𐎚 𐎛𐎍𐎎), variously ‘creatress of the gods’ (page 58), used in the Baal Cycles recovered from Ugarit. Since it’s a port city, her association with the sea was emphasized, and in this version she had 70 sons (though the Hittites claim 77 or 88).

She’s also called ʾElat, 'goddess' (from El, as in names like Michael or Gabriel), and Qodeš, 'holiness', from q-d-š, which makes some people equate her with the Egyptian goddess Qetesh, which is pretty flimsy but funny here because guess who she’s associated with? (It’s Ra. She’s also sometimes depicted as a lion/with Hathor’s wig. It’s a small ancient world after all)

Asherah & her iconography are mentioned 40 times in the Tanakh, but that’s cut way down in most English translations, where ʾăšērâ was almost entirely translated as ἄ��σος/ἄλση (grove/s) in Greek, except for Isaiah 17:8; 27:9, where it's δένδρα (trees) and 2 Chronicles 15:16; 24:18, where it's Ἀστάρτη--Astarte, a goddess of war, sexuality, royal power, healing, and hunting more associated with Ishtar than Asherah. Possible consort of Baal so almost certainly not actually Asherah. She did turn up in Egypt in the 18th dynasty as a daughter of either Ra or Ptah (Bastet’s consort), though, which is fun for me.

Asherah's very associated with trees though, so it does make sense they’d translate it to groves/trees. Found under trees in 1 Kings 14:23; 2 Kings 17:10, carved from wood by people 1 Kings 14:15, 2 Kings 16:3–4--there in reference to poles made for her worship, also called “asherah”. The Mishnah defines an asherah first as any tree under which there’s an idol, then specifically as any tree which is itself worshipped.

It lists associated plants: grapes, pomegranates, and walnut shells (invalid to eat or drink if from an asherah), and that myrtles, willows, and etrogs (but not dates?) were invalidated for Sukkot if from an asherah. I think the implication is pretty much any plant with a use can’t be utilized if it was an asherah, but there’s no like, description of what an asherah is or isn’t (except not allowed, which like, fair).

Regardless, to relate it to She-Ra is like... like you can’t just say that, man. The Da Vinci Code of fandom over here, except I’m personally upset about the false etymology instead of the disrespect to my boy Leonardo (da Vinci isn’t a name), and it pisses off every Abrahamic religion and like half of all neopagans. Are you happy? Now this whole section is blasphemous and heretical.

Let’s end this on a sillier note, shall we? It’s time to talk about questionable MOTUC decisions again.

No one sincerely suggested these for our world, but MOTUC established “the sword of He” as the ‘real name’ of He-Man’s sword, and it was later clarified that ‘He’ is the Ancient Trollan word for ‘power’... which, as you can imagine, led to a lot of confusion. It was never established if ‘Man’ is also Trollan, so the apparent translation is Power-Man (leading one forum user to jokingly ask if that made She-Ra ‘Iron-Fist’, after the Marvel duo). Naturally, people have speculated about possible translations for She-Ra, but the guy responsible for the Sword of He stuff left the company in 2014, so it’s likely to remain speculation.

Primarily people suggest ‘She’ might mean ‘protection’ or even ‘honor’, but very few people try to account for ‘Ra’. Most likely because it doesn’t mirror an English pronoun, so there’s little point in drawing parallels. The one and only theory I’ve seen is that it’s a feminine version of ‘Ro’, from He-Ro (a historical figure in MOTU), but it’s logically fraught, imo. Although frankly so is the Sword of He to begin with, so maybe I should just relax for once.

What do you think? What does She-Ra mean to you?

#etymology#analysis#she-ra#great news everybody i got it under 3k#if you thought my entry on adora was bad like. whoof. you ain't seen nothing yet

30 notes

·

View notes