#xEV

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

XZERO WEEK BONUS DAY 8 - TOGETHER

OMG ARE WE FINALLY DONE???

I CAN'T BELIEVE IT!! WE MADE IT THROUGH THE WEEK!!

It's been a blast participating for yet another year, even if the fics need to still be done, they probably won't be posted until wednesday, since I probs also won't be proofreading untiul starting tomorrow BUT HEY!!

Glad you guys could participate and I was SO HAPPY to see all your works and amazing writing!! I'm gonna read all the fics I reblogged now lmao. I don't call myself the xzero hoarder ceo for nothin!! lol

If I missed your guy's stuff, I am so sorry, the bookmark tagging system on here isn't all that great, I don't get to see everything qwq cuz it REALLY DID miss a few posts I thought wasn't posted yet WHEN THEY ACTUALLY WERE!! So that was a ride LOL

I'm wanting to host it again!! We'll see if I post for new dates or what have you!!

TIMELAPSE

Thanks for riding along and glad you guys could celebrate xzero week and pride month in one go!! Happy days for both events from me!!

Commission me on Artistree donate to me Ko-fi!!

#vincent rambles#vincent's art#xzeroweek#xzeroweek2024#xzero#zerox#mmx code crimpphire#code crimpphire related art#megaman x#mmx#xev#midnight#xevdex light#zero omega#XevMidnight#xzw BONUS day 8#I can't believe I made it another year LOL#it's hard doing daily art challenges even when it's only a week and I plan in advance ROFL

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

i love this episode and this scene in particular

2 notes

·

View notes

Link

From the Sci-Fi 5 Archive: Xenia Seeberg is one of the many actresses to play Xev in Lexx. This Canadian sci-fi show wasn't on my radar, but it's interesting to learn about in today's show.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

March 2012: Dead Ten Years (Draft 1)

This is both a nonfiction personal essay about me, my creative process, and my stepping away from art in 2009, and a Khra-nicles prequel/side story about Unge. It was done for a fiction class, but I'd already established a habit of telling true stories about me while pretending they were fiction.

I'll talk about this a little more in one of the upcoming posts, but in March 2012 I briefly returned to dA and tried to resume drawing and creating as I had done when I was a teen. It would not last.

------Text Follows------>

I have always sat down for tea with my characters, sipping away in the café of my mind where we chat about their lives and their futures and their thoughts and their dreams. Before I decided I was too terrible an artist to wield a pencil, I entered these teatime meetings by drawing my characters endlessly: profile, three-quarters view, face-forward stare, hands and arms and legs and feet and limbs, limbs, limbs, and a raging expression here or a joyous one there or an image of melancholy or remorse or fear or shock or thrill, and then the most important scenes from each of their lives until finally I went back and did the whole thing over again, pages of history notes sacrificed to the characters’ forms, their lines obfuscating the words.

For a time, starting around 2009, I ceased drawing any of them at all, convinced that the only worthy endeavor was to create new characters, explore new realms, run away from the world I’d been building since 2005 and the pantheon of characters Mare and I had birthed in the primordial soup of our friendship, all to attain a kind of writing I didn’t particularly enjoy. Somehow, every character following that so thoroughly drawn tribe fell flat, pancakes on a cold griddle. Proportionally, my sense of frustration grew, and I slowly became convinced I wasn’t good for much but long strings of actions, play-by-plays of capture the flag, and roaming introspections that blended Eastern and Western in a way that my peers did not like.

And then, in a fit of desperation, unable to conceive of a single new plot or personality, I wrote about Arren, andI felt reborn. It seemed to me then that my mistake all along had been to deny the characters I’d had tea with everyday of my life for four years. Quietly, I began to draw.

Unge S. Chickt stood at her window overlooking the city of P’tak from its opulent heart. Xev had been dead for ten years.

It was 0 A.K., the age-turning year following the death of the Demon Kifer, and Unge could hardly get used to the ideaJust the fact that the Demon was dead was nigh-impossible to adjust to after his reign of terror—thousands of years of civilization burning under his sanguine gaze ending all at once, demarcated by a change in calendar. Only the Elementals who were as old as Khra itself remembered a time before the Demon.

It had also been a year since Unge had met the hero who had slain Kifer: Arren Minetelle, a petite Fox Raeth with ice blue eyes wrapped in the blood crimson of a Ranger’s cloak. At the time, the girl had pep, a raging fire in her spirit that did not compromise, and a conviction that hers was the right path, the just one. She appeared, determined to slay Kifer, armed with knowledge from Rhawen, and prepared to risk it all. Unge sent her to Nassab in search of an artifact the girl had called the Demon’s Eye and did not see her again until the Battle at the Elemental Fields. There, Unge had joined her forces—IMDP—with the Elementals’ and the Rangers’ in order to defeat Kifer and his army. Arren appeared amidst the fray, her left eye gone, replaced with a desiccated, angry orb. Unge had naught to do but watch as the girl grappled with Kifer, tearing out the massive, glowing red stone that occupied his left socket. The Demon had screamed, his voice reaching an unearthly pitch of terror, and from Arren’s eye the desiccated thing leapt out with an angry hiss, falling into Kifer’s now empty socket. All at once, the Demon exploded into dust.

After the battle, Arren was nowhere to be found, and the Ranger’s Head was dead. Though Raeth celebrated Kifer’s death—such celebration Unge had never before seen—terror seized the Rangers’ ranks, chickens without heads. And then Arren returned, slogging out of the northern forests and stumbling westward to the Rangers’ Headquarters. The Rangers, the country’s populace, even the Elementals, demanded that she be the new Head, this woman who had killed the world’s great evil. Yet she stood before them, her left socket still a ragged hole, the edges of the bone cracked, the skin scarring, and she said no.

Garron Baylinthe became the Head, and Unge should have been happy about that. The man was a native of P’tak, born and bred in the city’s love for technology, though woefully filled with its distrust of magic, too. Still, this should have been fortuitous for Unge, placing her and her city in a less precarious position with the rest of the nation. All the same, the moment filled her with an odd foreboding, and before long she found herself contacting Arren, asking one thing: Watch the Rangers. Become a double agent.

Miraculously, the hero had agreed.

In some sense, I suppose, you could almost frame my understanding of my characters as a psychosis. As I was, by and large, depressed and suicidal between the ages of ten and nineteen, I developed a habit of consulting my characters. I would sit in the shower—I would have been fourteen or fifteen at the time—and, feeling thoroughly sorry for myself for no good reason, I would conjure up an image of Kriamiss or Pain, and I would imagine them embracing me, lending me their strength through simple contact.

This evolved, as such things do, such that, in the middle of high school, I would walk through the halls feeling them behind me—imaginary friends though it only occurs to me now to name it so—and it would be a simple matter to draw strength from them in that way. And, again, the whole affair evolved, as the fact of being single began to chafe, such that the characters became ideals, promising that, oh, if only they were real, they’d certainly love me because clearly no one else would.

There’s something shameful in that memory, an embarrassment lurking around the roots of the heart, and yet when I think how, after I’d abandoned them all, I brushed closer to death than I ever had before, I can’t help but wonder if perhaps the trade-off was fair.

Unge had never trusted the Rangers. They were, to her mind, a dangerous lot. Their Head was also Raeth’s Head, and while he was elected by the Raethian populace at large, Unge couldn’t help but wonder if the system could be rigged. Even when she was younger, breasts barely formed and yet already yearning for a greater purpose, the fact that the Rangers were Raeth’s only police force, its only military filled her with dread, fear, and something acid like bile. Where was the safety on that gun? Suppose, just suppose, that the Rangers ever went astray? Just suppose that they lost sight of their purpose, lost sight of their limits, lost sight of Raeth’s needs. What then? Who would be there to stop them? The Elementals didn’t bother themselves about Raethian business. The Mages were a scattered group of farmers’ helpers and wandering midwives. There was no one else.

For a long time, Unge struggled with that thought. Even when she set out from Nitemaer, determined to see the country in full, that sense of Ranger Danger followed her, with no feasible solution in tow. None, until Xev.

Twenty years ago, Xev said, “You’re right about this Ranger thing. We gotta do something ‘bout it.” Xev was from N’zik, a small city surrounded by desert to one side and jungle to the other, previously the capital of an ancient Dragonfolk civilization, and now just one of the four Raethian settlements that could be properly called cities, one for each point of the compass. Unge was not terribly impressed with the southern city, though the use of sandstone was lovely.

“I know, but what’s there to do?” Unge was perhaps twenty at the time, a traveler for only two years who’d nonetheless done away with the decadent fabrics and elaborate constructions of Nitemaer’s garb in favor of the simple leather and cotton to be found in most Raethian villages. “I’ve been thinking about this for years, and still I don’t know.”

“No ideas?” Xev, a Dog Raeth all of sleek Labrador blacks and dewy brown eyes, melted over the arm of his chair. He seemed impossibly long, arms trailing across the floor, toes delicately brushing the ground, and yet he was still, somehow, in proportion.

“Well.” She paused, turning the thoughts over in her mind. “If you’ve got one organization in charge of everything, that’s a problem. But what if you had two?”

He raised an eyebrow. “Two?”

“Say you’ve got the Rangers, just as they are, but then you make, like, a second Rangers— ‘cept call them something else obviously—“

“Obviously.”

“—Well then you task the second group with not only defending the peace and all that stuff, but also with keeping an eye on the Rangers. Then you go to the Rangers and say, ‘Hey, keep an eye on the new guys.’ So now you’d have double the police force and both would be making sure the other one didn’t slip up and go evil on us all.”

Xev smiled and reached out to touch Unge’s tawny hair. “Well why not do that then?”

Unge blinked, and one of her canine ears twitched. “Well, I mean, that’s not something I can do.”

Xev merely shook his head and offered her his hand.

Within a year the foundations of IMDP had been laid, and the year after that, they began recruiting. Five years after that conversation, IMDP was complete with secret agents, a business front to hide behind, and the cooperation of P’tak’s local government. The time had not seemed prudent to reveal themselves to the Rangers—much more effective to merely spy on them for now, until IMDP was of equal strength at least—and so the organization remained in shadow, its business front slowly elevating it until its letters stood atop a skyscraper right at the heart of P’tak, among the richest of the rich.

And then Xev died.

Here is something else about the characters and me. Nearly all of them are some part of myself, magnified over and over until perhaps you couldn’t tell they were ever me at all. Yet the fact remains that they are magnifications, and if you really, truly wanted, you could trace back their lineage. Kriamiss was a wish fulfillment fantasy on steroids, and forever and again, in the present, it is always a struggle to determine how to reduce an angsty enchanter-healer-angel-thing back into a person without upsetting the tender chronology of his entire story arc, of which Unge S. Chickt is but a small part. And so you have to look again and see what else they stole from you. By which I mean, from me. For Kriamiss it is the angst. Specifically, the angst that flies in the face of all the talent, all the ability, all the good fortune, and all the love that has ever and will ever be showered upon his foolish, morose head. His is a suburban ennui in a place that has no suburbs—though obviously I have suburbs, roiling in my blood the way a tar pit might bubble. Arren Minetelle, great savior of not only Raeth but all of Khra—the world’s hero, defeating its personification of evil—has what in common with a girl from [town], Massachusetts who can barely handle a stubbed toe, never mind ripping her own eye out— twice? For that you should look to Arren’s motives. Here is a woman whose cause is so just and so righteous that surely she must be the hero, surely she has saved us all, and yet she hunts down Kifer not because it is the right thing to do—so many had tried and failed over the thousands of years of his life—but because he killed the man she loved, a Ranger called Rusek who believed in due process. Arren enters in on a quest for revenge first—an eye for an eye makes the whole world blind—and on a quest for justice second, and therefore Arren is a cross-section of should and is, and if I don’t have that in common with her, then I don’t know myself.

But perhaps you don’t know these people, though now you must know Unge, and I’ve mentioned Xev, but as he is borne of M[...]’s consciousness, not my own, I cannot tell you about him. I can tell you about Unge, but I think you will find it anticlimactic.

Unge is among the oldest of the bunch. I drew her before anime styling crept, poorly, into my artist’s hand. I drew her before there was a Khra or a Kriamiss or an Arren, at a time when M[...] and I were only just acquaintances who shared a school bus. Unge came out of Neopets.com, out of a time when anthropomorphic animals were new and exciting to me so that I took to drawing gelerts—strange, dog-like things—in skirts with big, lavender eyes—a terrible sight to behold. When I “adopted” a gelert someone had named Ungeschickt, the name disappointed me. I therefore had to make Ungeschickt – quickly shortened to Unge for all intents, dues, and purposes – into the most badass of motherfuckers. And so, the first picture of Unge, ever, presented her as a femme fatale in a pink miniskirt and pearls, thoughtfully gesturing with her bloodied dagger. In this way, Unge was born of my love of 007, only to transmogrify, upon her entry into Khra, into a desire for a better world.

A knock, followed by Tarrin Carithelle, Rien Carithelle, and Arren Minetelle, all but Rien looking stoic. Unge turned, forty years of espionage squeezed into a business suit, forty years of aggressive gaiety etched into her face. “Hello, my darlings.”

Tarrin and Arren sketched stiff salutes, each in their own style, and Tarrin pretended that she was not awed by Raeth’s Very Own Hero. Rien beamed, unfazed by the world’s goings ons, mind still tangling with gears and levers and electricity.

“What did Rhawen say?” Unge asked, settling into the plush chair behind her desk and gesturing for the trio to settle themselves where they saw fit.

Tarrin snorted, mouth opening to snarl about the peculiar woman, but Rien cut her off. “She doesn’t want to see anyone besides Arren right now.” The tiny girl adjusted her glasses. “Though she did like the things we brought her. Especially the mechanical pencils. Completely taken with them.”

Unge rolled a pen on her desk. “But we don’t get to know where to find her?”

“No,” Arren said, a stone slab dropping. Her youth frightened Unge, sometimes. The ghastly eye socket, the runs in her face, deep-set, that made her look like marble, the ice blue of her remaining eye—just ice now—her hand never straying far from her sword’s pommel (a sword only allowed by P’tak’s strict ban on selling guns outside the city and the centuries-long lack of trade between Raeth and Nassab, though that wouldn’t last much longer if Unge had anything to do with it).

“No?” The pen rolled off of Unge’s desk.

Tarrin grumbled but held her tongue.

“Rhawen is not in a position to be as helpful as she’d like, and to that end it is better for her if as few people know her location as possible.” Arren allowed herself a sigh and continued, “I had thought that enabling you to go to her directly might not be asking too much, but Rhawen is adamant on this point. She is…”

“Yes, what is she?” Unge snapped, frustration surprising both her and the three women before her.

“Unge?” Rien squeaked. Unge shook her head.

One of the lines in Arren’s brow softened. “Rhawen is something of the world. Old. She has her reasons.”

“Well I’d feel a lot fuckin’ better about it if she’d just give us straight goddamn answers,” Tarrin growled.

The brow line reasserted itself. “Perhaps you should just get better at riddles then,” Arren said.

Unge pondered for a moment. She’d been working with Rhawen before Arren had killed Kifer, but the woman had never opened up to Unge the way she had to Arren, and even that was a chilly connection.

A wave of fatigue washed over her, and she missed Xev.

“Well thank you for trying, my lovelies,” Unge said, feeling herself sink onto her desk. “I suppose we’ll just do things the way we always have. We’ll wait.” Xev wouldn’t have tolerated this waiting. He’d have been tracking right up to Rhawen’s house and demanding answers, all with a pleasant smile.

One of the oddities of the internet is that every individual’s idea of it is discrete, separate from every other individual’s idea of it. My internet is different from yours is different from Steve’s is different from your little cousin’s even though we all can and do talk about the internet as if it were one thing—one place—when, in fact, it is a thousand tiny microcosms. My internet was a place for outsiders to hide and feel less alone. I spent time on Neopets, constructing, building, proposing characters and web pages and drawings and later yammering on to deviantArt and then role playing with M[...] on AIM—all day, every day, talking around the character’s conversations as if we were at some sort of party—and on and on and on, until between M[...] and I, we had produced an entire world filled with faces I knew and loved in a way I could not know or love the people around me because reality would never be anything but disappointing. (And so there it is.)

But what is odd is that when we left that world, all the other fictions out there were never enough for me either. So it was disappointing reality, disappointing fiction, and then before you know it, you’re what feels like a lifetime away from those socially reclusive days, and you find yourself starting to submerge yourself in all those old habits right back over again. And what’s more, M[...] is too, though the methods are slightly different. Why, after abandoning deviantArt four years ago, have we returned to it, just as she graduates from [college]? Why, four years after I set aside Khra, the KriamBook, the Pupcat Riley Story, the Asher Concept, and Arren’s Tale, have I found myself inexorably drawn towards them, fed up and disgusted with everything else that droops out of my pen, just when I’m meant to be serious about my work, my career, my life, and the future? What has caused us to come full circle, and why am I the only one of us twain questioning it?

Xev died on a mission of first contact.

Unge harbored two great dreams. The first: fix the Raethian judicial and political system to better prevent corruption. The second: re-establish diplomatic ties with Nassab and undo the political damage caused by the Great War, a thousand or so years ago. The trouble with this latter goal was, first and foremost, that a Human of Nassab would always kill and Raethian on sight, and most Raethians wouldn’t behave a whole lot more nobly. Oh, naturally, illegal trading had always occurred between the two continents—P’tak’s technological wealth was drawn directly from that fact—but Unge desired open trade. Raethian society was ruled by magic—the fact of the Elementals on the continent ensured that—and Nassab, left without easy access to magic, had turned to technology. And Unge wanted both. Nitemaer was one of the few places that mixed them, and that mentality ran deep in Unge.

It was only natural that—observing the black market ships sailing between Bollen on Nassab and P’tak on Raeth—Unge determined that IMDP would certainly engage in some trading of its own and once begun, found their dealings with Bollen went well. Unge then thought to expand. To that end, she sent Xev to northern Nassab, and when he returned, he was merely a head in a box, a note pinned to the outside: “No Dogs.”

Unge shook the cobwebs from her mind. Tarrin and Rien had left, returning to their respective departments. Arren remained, sipping water and looking over Unge’s view of P’tak. Unge, at her side, pointed out through the city’s haze to where the ocean was just barely visible. “One of these days, that’s gonna be all boats all the time.” She smirked. “You won’t be the only Raethian to scoot around Nassab.”

Arren nodded, remaining eye closed. “Rhawen asked a favor of me.”

“Oh?”

From a pouch on her hip, Arren removed a small letter, some tiny object weighing down one of the envelope’s corners. It was sealed with orange wax—an odd choice—the imprint of what looked to be a dragon in flight squashed into the pumpkin color. An extinct animal for an ancient woman who didn’t look a day over twenty-five, apparently knew everything there was to know, and then refused to tell you. Why not dragons?

Unge took it to the desk and broke the seal. Alongside the letter, Rhawen had inserted a pendant matching the seal impressed into the wax—one of those extinct dragons in flight. Unge ran her thumb over it, unsure of its connotation, though remembering that Rhawen wore one such pendant. She glanced at Arren, a question in her eyes, but Arren did not meet her gaze, sipping her glass of water instead.

Unge settled into her chair and read the letter.

Allow me just one more moment of your time, before you read Rhawen’s letter, before you decide if all this time spent poring over a day in Unge’s life and the musings of her author—her technical, real author, not Rhawen, the Narrator, who is the voice who tells these stories—was wasted.

Purpose applies to all of these situations. I don’t know what your life was like in 2001 or 2002, but I know what mine was like, and for all the material fortune in the world, I was nonetheless struck with a deep-seated misery that I couldn’t explain, and really I still can’t, at least not in a way that feels authentic. I was filled with guilt over this feeling—“There are children starving in Africa!”—and yet the feeling persisted until I became jealous of the starving children because at least they knew why they were miserable. It’s no surprise then that the characters I birthed were universally sad, universally restless, and universally struck with tepid misfortunes which, in theory, should be world-shattering, and yet in application remained ineffective. Kriamiss’s mother dies when he is fifteen, and he flees his home, finds the father that abandoned them and that man dies too, and then when he finds someone to love in the world, she kills him, and it isn’t until he’s been dead five hundred years that he has a second chance—to save the world, to become whole. My inability to feel anything at a degree less than acutely became his saga of misfortunes—too many to be useful, narrative-wise, but just enough to try to justify feeling the way I did.

So why feel so acutely? It’s hard to say. Do you blame a chemical imbalance; do you blame a spoiled upbringing; do you blame an inherent, genetic sensitivity, or do you perhaps put it down to some sort of flaw, a lack of the “right stuff”? I’m not sure; it’s all too far away to say anything concrete about. The memory is unreliable, the heart is unreliable, the mind is unreliable, even the evidence of the eyes is unreliable, because all is perception. In the present time, however, let us put it all down to purpose. There was purpose when we created, there was a loss of purpose when we stopped, and now we seek out purpose again—and so the whole world, the whole array of characters, have returned, because they cannot exist without us.

And how about Kriamiss or Unge? Why is it that every character I create is alone, at the end of the day, always by themselves, contained within the space of their own bodies, isolated? I am alone when I am with people; I am alone when I am not. Solitude, then purpose. We—the characters and me—travel alone and look for something to do. Something meaningful. Save the world, that’s always good, or maybe just improving it will do. Always with the epic narrative, always with the complete saga, and always with the search for purpose and the inescapable solitude.

I reiterate: the characters are me.

Unge—

Some twenty years ago, I sat on a café veranda in N’zik, and I watched a young Dog Raeth with tawny hair and a full bosom chitter and laugh with another young Dog Raeth, this one a sea of blacks and browns constructed into a long, lithe, lingering body. They laughed with one another, at one another, at themselves, caught in what I shall call puppy love. I saw, at that time, their histories and their present, and while I have never been known to predict the future, everything I could sense about them suggested that they were bound for greater things. When, ten years ago, one of the two passed from this world on to Ahrk, I knew of this too, and I thought for a long time about how to make things right.

What answer can I give you? Arren sought out her own, and I supported her, and now, even with all the knowledge a mortal can be allowed, I find myself regretting. There lies Kifer, dead, and is not one girl’s youth worth the safety of thousands? But still the regret persists.

I digress.

You have a dream.

The Dragonfolk are waning, but their presence is still felt and revered in the northern climes of Nassab. Southern Nassab is, generally, filled with hatred for their once-oppressors, but in the north the sentiment is less present, the sins more forgiven, and so a Dragonfolk token can go a long way. Therefore, please find enclosed the symbol of the Dragonfolk; may it earn you passage to those places closed off to all but the eldest. I will only ask that you do not use it to go to the Verde Isles.

With these thoughts in mind, I wish you well and tell you now that Xev died wishing for you.

Rhawen E. Fox

Unge choked and found, through her sobs, that Arren stood at her shoulder, merely holding it. The younger woman maintained that spot, one worn hand acknowledging Unge’s pain for the half hour it took the older woman to regain herself, her gaiety washed away by a ten-year-old memory of a dead man.

When Unge had subsided, Arren took herself to the other side of the desk and sat down. She folded her arms on the black, sanitized wood, her posture suddenly more like the girl she should have been. Eyes hard on Unge, she said, “I’ve known tears like that.”

Unge nodded. “Xev was—he made this. All of this. Just by saying it was possible. Just ‘You can do it, Unge.’ This can be done. And then it was. That was all it took. He said I could do it, so I did.” Her breath rattled. “How do you come back from that? How do you answer for that death?”

Arren took her hand and gave it a squeeze. Unge could feel every crease, every callous in the hero’s hand. Here was where her sword had worn itself a home and here at the finger tips the place for her bow. These tiny cuts for every hour of traveling from one Raethian coast to the other and these weathered folds for every night spent alone beneath the stars forming a web to catch demons. Arren’s nails were dirty, but in spite of the usage written across her hands, Unge could see where once the delicate shape of a genteel woman’s glove may have fit, and Unge’s own palm felt suddenly fat and chubby in the grasp of one so conflictingly worked.

Arren withdrew, her whole self drawn back up into the raw eye socket, sucked behind a glacial mask. She stood, saying, “The Rangers will miss me momentarily. Baylinthe’s put his son and Brue Nadir as his top officers. Most of the men are terrified of Brue, which leaves me and the boy to see that morale stays up.”

Unge closed her eyes, nodding her understanding, but found Arren leaning in when she’d opened them again.

“The boy. Maroc Baylinthe. He might be trouble.”

There seemed something more she wanted to say, and Unge prompted her—“How so?”—but Arren shook her head and stepped away. “It may just be me. The men love him.” A tightness around her mouth suggested a deeper trouble, but Arren shook it off. “No, it is nothing. He is a Ranger, after all.” With that, Arren saluted, said her farewells, and whisked out of the room, just a red cloak disappearing behind metal doors.

Unge considered the disappearing cloak and fingered the pendant. She laughed. “Dragonfolk symbols and the great hero feels compassion? Oh dear.” She’d have to have someone look deeper into these Baylinthes. Arren wasn’t the most intuitive of ladies, but Unge wasn’t about to dismiss her discomfit out of hand. The Rangers had completely failed to exhibit corruption, these past ten years. Perhaps now was the time?

Unge left her chair, pendant still in hand, and returned to her favorite spot, staring out over the city—her city—where she contemplated reconciling the half-animal Raethians to their long-lost cousins, the Humans of Nassab.

#old writing#writing archive#short story#personal essay#fiction#nonfiction#prose#Khra-nicles#Unge S. Chickt#Xev#who was originally my bestie's but I stole him#yoink#Rhawen Evergreen Fox#Arren Minetelle#Tarrin Carithelle#Rien Carithelle#Kifer#Maroc Baylinthe#Phoenix#Pain#Kriamiss Orientere#oc writing#original characters#10s#2012#Age 21#assignments#being a maker#angst#depression

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Because I’m in a mood; here’s some of my weird crackships for PR. Enjoy!

Dane Romero x Mr Kelman x Andrew Hartford

Mike Corbett x Carlos Vallerte

Conner McKnight x Xev

Taylor Earhardt x Dana Mitchell

#Dane Romero#Andrew Hartford#Mr Kelman#Power rangers operation overdrive#power rangers ninja steel#mighty morphin power rangers#mighty morphin power rangers the movie#Power Rangers Dino Thunder#Conner McKnight#Power Rangers Wild Force#Power Rangers Lightspeed#Taylor Earhardt#Dana Mitchell#Power Rangers Boom Comics#Xev#Power Rangers Lost Galaxy#Power Rangers Turbo#Power Rangers In Space#Carlos Vallerte#Mike Corbett

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

0 notes

Text

Sapura Industrial, Mili Tech partner to boost Malaysia’s EV growth

In a move supporting Malaysia’s sustainable and electrified future, Sapura Industrial Berhad (SIB), through its subsidiary SIB Ventures Sdn Bhd, has signed a joint venture with Mili Tech Sdn Bhd to create SIB Mili Sdn Bhd. This partnership, solidified after initial feasibility studies following an April 2024 MOU, aims to advance Malaysia’s electric vehicle (xEV) industry by providing after-sales…

0 notes

Text

Novo Mercedes-Benz Classe E plug-in diesel limousine e station com preços definidos

A gama de motorizações do novo Mercedes-Benz Classe E (W214) está agora mais completa com a introdução da aguardada motorização híbrida plug-in diesel. As primeiras unidades serão entregues no início do ano que vem.

A motorização híbrida plug-in a diesel – E 300 de – está disponível para encomenda nas versões Limousine e Station e conta com uma autonomia elétrica combinada superior a 100 km. Os preços iniciam nos 75 950 euros para a versão Limousine e nos 78 550 euros para a versão Station. As primeiras unidades chegam ao mercado português no início de 2024.

As versões plug-in e station juntam-se às gasolina e diesel já presentes no mercado.

1 note

·

View note

Text

An appreciation post to xev bellringer. Thank you so much.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Landy Cannon as Root in LEXX Season 3 Boomtown Episode

#LEXX#lexxedit#Root#Landy Cannon#Boomtown#tvandfilm#dailytvfilmgifs#dailymenedit#dailymencelebs#Canadian Actor#My Gif#dilfgifs#dilfsource#Daddy#Me too Xev I love looking at him#LGBT#lgbtedit#canon bisexual#pun intended#bi the way#Planet Water#stay hydrated

505 notes

·

View notes

Text

a special mummymon ko-fi c0̷mmission for @shevuun, thank you so much, it was such a pleasure :D

*do not use unless you are the client*

#digimon#mummymon#arukenimon#digisafe#grani.png#commission#i really apperciated your patience and look forward to the results!! also reminded me how awesome mummymon is... loved him in 02 gg and xev

200 notes

·

View notes

Text

XZERO WEEK DAY 7 - WISH

finally got this done!!

this wasn't uploaded on time cuz I wanted to get more fics written before I proofread them this weekend and finally post them on one or two days during the makeup week

the fic I wrote for this one is a little weak so proofreading it would hopefully help

Anyway enjoy day 7 from me!!

TIMELAPSE

Commission me on Artistree donate to me Ko-fi!!

#vincent rambles#vincent's art#mmx code crimpphire#code crimpphire related art#xzeroweek#xzeroweek2024#xzero#zerox#xev#midnight#xevdex light#zero#omega#XevMidnight#xzw day 7

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

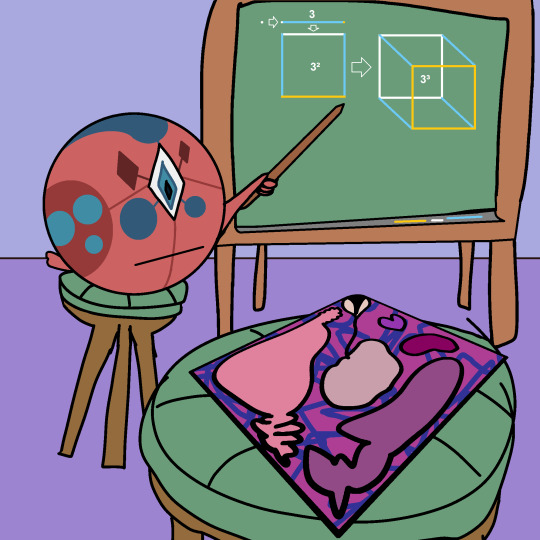

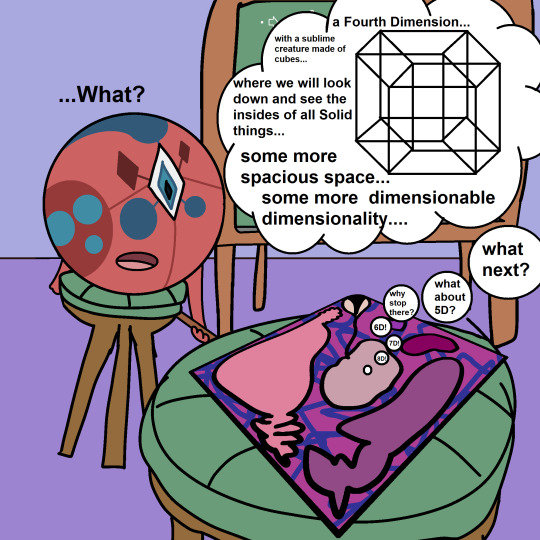

3/3 people add the image description to the original posts in plain text, so now you get to see my new design for the Sphere even though I'm not done writing the short story yet, which will be posted to @neopronouns-in-action

This version of the sphere is named Kormance, and uses the pronouns xet/xev/xel/xevself, which are used like he/him/his/himself:

Replace he with xet

Replace him with xev

Replace his with xel

Replace himself with xevself

EX:

"He is going to adopt a new puppy soon, as soon as he gets a fence set up around his yard so the puppy can go outside without him having to walk it. His uncle is going to help set up the fence, since he has a set of power tools he's letting him use, since he lost his. He's going to buy toys and train the puppy himself."

Becomes:

"Xet is going to adopt a new puppy soon, as soon as xet gets a fence set up around xel yard so the puppy can go outside without xev having to walk it. Xel uncle is going to help set up the fence, since he has a set of power tools he's letting xev use, since xet lost xel. Xet's going to buy toys and train the puppy xevself."

this is not actually a scene from the short story.

[ID: A three panel comic, showing A Square and the Sphere from Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions. A Square is a 2D square with purple and blue insides, with blobs for organs in different shades of pink and purple. Kormance the Sphere is a light red sphere with blue and darker red spots and diamond markings, with sharp teeth. Xet has a single diamond shaped eye, with blue and black diamonds inside it. Xet has two arms, one ending at the elbow unevenly. Both characters are sitting on tall stools with yellow and orange cushions, while the Sphere uses a short rod to point at a chalk board marked in blue white and gold, showing the progression from a point, to a line (3) to a square (3 squared), to a cube (3 cubed). Panel 1 has Kormance the Sphere asking, "So do you finally understand the mathematical progression now?" A Square replies, "Yes, and I'm ready to learn about the 4th Dimension now", with a smiley emoticon. After panel 1, the cushions on the stools become the same green as the chalkboard. Panel 2 has Kormance staring at A Square with a blank expression, saying nothing. Panel 3 has Kormance with arms lowered, mouth agape, asking, "…What?". A Square is lost in thought, thinking, "A Fourth Dimension…with a sublime creature made of cubes…where we will look down and see the insides of all Solid things…some more spacious space…some more dimensionable dimensionality…what next? What about 5D? Why stop there? 6D! 7D! 8D!" End ID.]

For every $10 donated to a Palestinian relief fund, I will make another character design like this to be public domain!

Click here once a day to help Palestinians!

#described images#described art#Flatland#flatland a romance of many dimensions#Flatlandaromanceofmanydimensions#Kormance the Sphere#A Square#Raymond the Square#not that it matters for the art lol#Rjalker does art#The Sphere#Neopronouns in Action 090#Rjalker writes Neopronouns in Action#neopronouns in action#xet/xev/xel/xevself#xetxevpronouns#novapronouns#neopronouns#xet/xev

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jan. 2013: "Narrator" Final Draft

I'm like 99% sure this is actually the final draft. It also looks like it's been formatted as a submission for publishing. I'm not sure where I would've submitted it to, but that's how it looks.

----------Text follows--------->

For most of my life, I’ve daily sat down for tea with my characters, sipping away in the café of the mind. We chat about their lives and their futures, their thoughts and their dreams. We get to know each other.

Before I decided I was too terrible an artist to wield a pencil, I entered these teatime meetings by drawing my characters endlessly: profile, three-quarters view, face-forward stare, hands and arms,legs and feet, limbs, a raging expression here, a joyous one there, or an image of melancholy, remorse, fear or shock or thrill, and then the most important scenes from their lives until finally I went back and drew the whole mess again, pages of school notes sacrificed to my characters’ forms.

In 2009, when high school graduation and my entrance into college was imminent, I stopped drawing my characters at all. I became convinced that they were holding me and my writing back, and I though that the only worthy endeavor would be to create new people, explore new realms, and run away from the world I’d been building since 2005, from the pantheon of characters my best friend and I had birthed in the primordial soup of our friendship. It would all let me become a Writer, I thought. If I just shed my childish characters, then perhaps I could become someone literary, worthy of publishing. But somehow, every character following my original, so thoroughly drawn tribe fell flat like pancakes on a cold griddle. With each new, bland character my sense of frustration grew, and I slowly became convinced that, as a writer, I wasn’t good for much but long strings of action, and roaming, unsatisfactory introspections.

After two years of uninspired work and faced, suddenly, with the daunting task of creating a screenplay that I would need to work on consistently for three months, I became desperate.I was unable or unwilling to conceive of a single new plot or personality,and I turned back to the pantheon of my early adolescence, writing a screenplay detailing how the ranger Arren Minetelle defeated the Demon, Kifer. The six-year-old characters rose up once more to act out their tales and even found acceptance amongst the screenplay’s handful of readers. I felt reborn, and it seemed to me then that my mistake all along had been to deny the characters I’d had tea with every day of my life for four years.

Quietly, my class notes filled with drawings.

The age turned, and in a blink, the world called Khra shifted from 1027 A.W. to 0 A.K. Still mere hours after the death of Kifer, mere hours into the new era, Arren Minetelle stood on my doorstep. Blood dribbled down her cheek, her left eye socket reduced to a ragged mass of shredded flesh and cracked bone, as if a small explosion had gone off inside her skull. A fog glazed the icy blue of her remaining eye, and deep lines crossed her otherwise young face. I stepped aside for the young arctic fox raeth and closed the door on the new reality she had created.

“Rhawen,” she said, rasping, “could I have a glass of water?”

I nodded, and Phoenix, not needing to be told, scurried on swift fox paws into the kitchen, coming back with bandages in her mouth and a cup of well water perched on her head. I took both from her. The Fire Fox hurried back into the kitchen, and I heard the soft ruckus of a tiny Elemental quadruped setting a pot of soup aflame.

Arren gulped the water gratefully and allowed me to push her silvery hair—it had been a pale blonde but half a year ago when she had come to me looking for means by which to defeat the Demon called Kifer, bane of all the peoples and nations of Khra—away from the still-weeping crater where her left eye had been. The missing eye and the faint, browning marks of grasping hands around her neck were enough to tell me that she had fought Kifer, and her continued life confirmed that she had defeated him. I needed neither her words nor my own Creator-given knowledge of all past and present to recognize the sorrowful marks of her victory.

As Arren chose not to speak, so too did I. It wasn’t long before Phoenix trotted in, pulling a small wheeled tray on which a bowl of chicken soup and a pan of warm, clean water rattled softly. I took up the pan first and began to dab at Arren’s wound. She winced as I worked but made no sound even as my cloth fumbled into the oozing mush behind her bones. Phoenix padded around the table, blowing flame over the soup occasionally to keep it warm. The gentle crackle of her fire-filled breath snaked across the silence of my cottage, snapping off the wooden walls and dancing over the floor.

When the pan’s water had turned a crimson to rival that of Arren’s ranger cloak, I began to bandage her head, prompting a proper reaction from the nineteen-year-old girl.

“I’ll not hide it!” she snapped, batting my arms away with more force than she’d intended. “You of all people should know, Narrator.”

I elected to ignore how she spat the word. “You’ll need to wear bandages for a time if you’d rather not die from an infection.”

“Well—maybe I’d—you don’t know—“

“But I do. Narrator, yes?”

Arren scowled. “Fie on your bloody omniscience.”

“Near-omniscience,” I replied automatically, regretting the habit in the pause that followed. “I… am sorry I didn’t tell you what you would have to do. I did not think you would go if you knew the price…”

Arren choked, battling tears with as much ferocity as she had battled Kifer. She succeeded in swallowing the lump in her throat and threw my apology in my face. “You understand nothing. You are nothing. You write, what, histories? That’s all I am for you. A history. No. No, I won’t have it. I won’t be a hero! I won’t be a legend! I won’t have it!” She dashed the pan from my hand, and my floorboards greedily sucked up the blood. “They died, you horrible bitch! That damn Eye—Kifer’s damned Eye! I wasn’t even conscious and it made me—I… There were children there, Rhawen! The entire village…”The woman who had saved the world flopped back into a chair and shook as the memory of how the artifact that had allowed her to kill Kifer had also forced her to slaughter innocents replayed in her mind. “All of them dead.”

I placed the soup in front of her and left the room, disappearing into the basement.

Phoenix, who had accompanied Arren on her journey, curled up at the girl’s feet. “I’m sorry,” the fox said. “She didn’t have a choice.”

Arren did not respond, instead spooning soup shakily into her mouth, thinking it needed salt, until at last the tears did come and added all the flavoring my cooking lacked.

Between the ages of ten and nineteen, I developed a habit of consulting my characters in my day to day life, particularly when I felt completely crushed by hopelessness. I would sit in the shower—I would have been fourteen or fifteen at the time—and, feeling thoroughly sorry for myself for no good reason, I would conjure up an image of Kriamiss or Pain, and I would imagine them embracing me, lending me their strength through simple contact.

Over time this personal conceit evolvedso that, in the middle of high school, I would walk through the halls feeling my characters behind me as an imaginary entourage, and it would be a simple matter to draw strength from them throughout the day. Eventually, the characters became ideals, promising that, oh, if only they were real, they’d certainly love me because clearly no one else ever would.

There’s something shameful in that memory; it brings up an embarrassment lurking around the roots of the heart, and yet when I think how, after I’d abandoned them all, I felt more lost than ever before, more doomed, and more worthless I had before, I can’t help but wonder if, perhaps, the trade-off was fair.

Kriamiss Orientere lay asleep in my bed, a dead man breathing as one alive, forgetting in sleep that his body was little more than his own will made manifest. It was 5 A.K., and civil war threatened the Raethian way of life. Across the sea in Nassab, the human populaces had gotten their hands on the cloning technology of the Dragonfolk of old while a dryken lad sought to recover a Dragonfolk weapon of mass destruction in order to prevent it from falling into the wrong hands. The Creators had dispatched Fallen like Kriamiss—individuals who, after death, worked to keep the world of Khra safe by maintaining the delicate balances that held it together—across the globe in an effort to rectify the myriad of problems that threatened global stability. The Narrators’ Council had summoned me for the first time in an absurd number of centuries. Unge S. Chickt sought to renew trade between Raeth and Nassab despite Raeth’s broader troubles, and Arren Minetelle, great hero of five years prior, had slipped into obscurity; I alone knew she still lived. Adding further absurdity to the whole fiasco, the Power representing pain had manifested on Khra—it had been millenia since last any of the Powers took on physical form—and was now lounging in my basement. For my own part, I pulled my usual stool up to what was now Kriamiss’s sickbed and sat contemplating the trajectory of this once-deceased man.

Some five hundred years ago, a woman from Niméth had the misfortune of bearing a child out of wedlock, her husband having disappeared into the surrounding countryside. The woman, Ellenyiel Orientere, named the child Kriamiss. He was “gifted” with Healing magic. Simply by laying hands on someone and exerting his will, he could cure almost any ill and, in one or two cases, defeat Death himself, though the effort whittled away at his own lifespan. Later, the boy had the dubious fortune to encounter a Light Elemental who, seeking her own death, granted him the power of the Elementals, transforming him into a Mage, able to bend light itself to his will. After just short of a decade spent futilely working to defeat Kifer, Kriamiss died at twenty-two in 534 A.W.and proceeded to join the ranks of the Fallen—deceased tasked with maintaining world order—and utterly failed to return to Khra until some five hundred years later when Kifer’s death and the need for Fallen hands manipulating the Raethian civil war enabled his resumption of life.

Kriamiss stirred. I called for Phoenix, and once she’d limped into the room, I wandered into the kitchen, unsure how to proceed.

I had, of course, known of Kriamiss’s return, and I had, of course, sent Phoenix to aid him wherever possible: grant him my accesses to hidden places, give him some part of my knowledge, help him orient himself in a world that no longer operated on the same rules or even spoke quite the same language. I had not expected her to lead him here. Although Phoenix wasn’t with me at the time, the fact remained that I had met Kriamiss five bundred years ago and seeing me now was like to upset him. I was visiting my long-time pen pal, Kriamiss’s mother, Ellenyiel, As a single mother in a draconian society, she and her son were marked as outsiders, despised. Indeed, when I arrived in the town the citizenry viewed me with undisguised loathing for I had the audacity to wear pants, in spite of my feminine sex.

The Orientere estate lay next to the city’s rather expansive graveyard, and it looked like a haunted place. The lawn was brown where it wasn’t overgrown, and the garden weedy where it wasn’t dead. The gate’s hinges were rusting, though it still managed to open and shut without undue creaking, and the majority of the house’s windows save those on the first and second floor of the east wing were shattered or at least punctured. Ivy had overtaken the house’s southern face, and I saw more than a few of the stones that made up its walls crumbling. As I approached, a group of children clambered over the fence, back onto the street, and scurried away. Focusing on them, it came to me that they had spent the past half hour destroying carpeting in the house’s west wing and pissing in the fountain that punctuated the estate’s long drive. I briefly considered chasing them down and boxing their ears but decided that I was no match for a gang of ruffians, even small ones, and settled for traipsing to the house’s front door and cheering Ellenyiel with my ever rare presence. She didn’t have many friends, I knew, or more accurately, she had none besides myself, and I wasn’t much of one, being little more than ink on a page.

My effort to use the wolf-shaped doorknocker resulted in the old brass coming off in my hand. I deposited it in a bush and was about to knock when a little boy with black hair like rich satin and steel grey eyes like an ocean storm came around the corner and stared me down. He was wearing hand-me-down britches and a loose tunic, and I recognized the rather massive volume in his hand as Mage Archwylde’s Elementals and You: A Beginner’s Guide to Elemental Magic which was nonetheless utterly verbose and didn’t much belong in a child’s hands.

“Stranger,” he mumbled.

“Rhawen,” I corrected. It occurred to me that he’d likely never been outside Niméth and thus never properly seen a Raethian who did not share his coloring. My oranges, browns, and golds likely startled him. “I’m from south of here,” I added, kneeling.

“Obviously.” He took my hand, horrifically bold by Niméth’s standards. “Your a red fox Raeth, aren’t you? Your eyes’re kinda weird.” It was a true enough assessment. I had rich, golden eyes with a depth a saturation unseen in human, dryken, or raethian. Indeeed, the only people who had such eyes were either long-dead or were, like myself, Narrators.

“Hm, yes,” I agreed. “I suppose you’re Kriamiss.”

He nodded, absently. “Your hair’s two colors too.”

I sighed. “Is your mother home?”

His eyes narrowed at that. “Depends on who’s asking.”

I don’t particularly like children at the best of times, and Kriamiss was proving to be unpleasantly precocious. “I suppose I’ll just go look.” The door turned out to be unlocked, and so I let myself in, Kriamiss at my heels yapping about how rude I was being and what he’d do to me if I laid a hand on his mother. The noise drew Ellenyiel’s attention, and she bustled into the foyer before I’d hardly begun snooping.

“What’s going on out—Rhawen!”

We had met in person only once before, but Ellenyiel nonetheless rushed up to me and wrapped me in a hug. “Oh my goodness, I had no idea you would be coming! I’d have prepared a room, made the house presentable, I’d—“

“I hardly knew I was coming myself, Elle.” She glowed prettily at the use of the nickname, previously relegated to written lines. “I happened to be in the area on business, and I thought I’d stop in. Would you like your son back?”

The boy side-stepped over to his mother’s voluminous skirts, still suspicious of me, perhaps more so for my familiarity.

“Ah. Yes...” Ellenyiel knelt down to her son, and I heard the bones of her corset creak. “This is Mama’s friend from the letters, little love.”

Grudging trust entered the boy’s features, and I couldn’t help but chuckle. My laugh apparently wounded his pride as he muttered, “She broke the door knocker.”

I spent much of the day there, chatting with Ellenyiel whilst Kriamiss sullenly observed me from his mother’s side. Something about the boy struck me, and on my return home, I found myself writing down everything that had occurred such that Phoenix, coming in from a hunt, wandered up to my desk and asked, “Got a new Tale?”

I wasn’t sure how to answer and said as much. “It’s a strange feeling. I feel the pull, most certainly, but it’s as though it were a fishing line being reeled from across a lake.”

And now here I was on the opposite shore,Kriamiss at five hundred and twenty-two, though lying in my bed and the call of a Tale dragging at my senses. I had the impression that this was not my usual narrative. This was, somehow, impossibly, something to be built.

I’d barely begun to examine my Narrator’s instincts when I found Pain’s hands on my hips. Fortunately, on this occasion they were fully attached to his arms, his flesh properly sewn together. In fact, it looked as though all his limbs were connected in the usual fashion, though his grin still stretched much too far, seeming to split his face across the cheek bones. As usual, I was struck by the peculiarity of feeling Pain looking at me although he lacked eyes or even eye sockets, a flop of mangy brown hair disguising the absence. The Power cackled. “It would seem, my dear dear darling love-butt, that we have a visitor!” He barely contained a giggle of glee.

“Do try to contain your excitement.”

“Oooh, but he’s so yummy. Lots and lots of pain to nibble on, and so pretty too! Just a little lick?” He wriggled his fingers at me in imitation of a scuttling insect.

I snorted. “Definitely not. He’s going to have shock enough when he realizes what I am, never mind discovering that the Powers have woken up as well.”

“Oh, always so dry. You’re never any fun.”

“But I do put up with you.”

“Hepf. Only because I eat your migraines. You’re just using my mystical Power powers.” He had manifested as a dog raeth, and now he twitched his ears in a frisky gesture. “Naughty girrrrllll…” He reached for me, intending to tickle or trap, it was hard to say.

I stepped aside and stacked a few bowls into the sink, refusing to play his games. “How is it that the manifestation of pain is nothing but mischievous?”

One of Pain’s hands came unattached, traipsing away from the stitches that held it to his wrist until they snapped, and walked itself down the counter and over my wrists. “Well if you couldn’t feel any pain, wouldn’t you start—“

A brief scream erupted from the doorway, and we turned to see Kriamiss, half naked, staring at us, aghast with Phoenix held, by the scruff of the neck, in one hand. She looked sheepish. “What in the bloody damn hell is going on?” He seemed unable to decide what oddity to discuss first but finally settled on me. “You should be dead!”

“Well so should you,” I pointed out.

Nearly all of my characters are, at their core, some part of myself, magnified over and over until perhaps you couldn’t tell they were ever me at all. Yet the fact remains that they are magnifications, and if you really, truly wanted, you could trace back their lineage. Kriamiss was a wish fulfillment fantasy on steroids, and in the present, it’s a struggle to reduce the angsty enchanter-healer-angel-man back into a believable person without upsetting the tender chronology of his entire story arc. It becomes necessary to look again and see what other sources may be there. For Kriamiss it’s his angst. Specifically, the angst that flies in the face of all the talent, all the ability, all the good fortune, and all the love that has ever and will ever be showered upon his foolish, morose head. He’s filled with suburban ennui in a place that has no suburbs—though obviously I have suburbs, roiling in my blood like a bubbling tar pit. Arren Minetelle, great savior of not only Raeth but all of Khra—the world’s hero, defeating its personification of evil—has what in common with a girl from Canton, Massachusetts, who can barely handle a stubbed toe, never mind ripping her own eye out—twice? For that you should look to Arren’s motives. Here is a woman whose cause is so just and so righteous that surely she must be the hero, surely she has saved us all, and yet she hunts down Kifer not because it is the right thing to do—so many had tried and failed over the thousands of years of his life—but because he killed the man she loved. Arren enters in on a quest for revenge first—“an eye for an eye makes the whole world blind”—and on a quest for justice second, and therefore Arren is a cross-section of should and is, and if I don’t have that in common with her, then I don’t know myself.

Unge S. Chickt is among the oldest of the bunch. I drew her before anime styling crept, poorly, into my artist’s hand. I drew her before there was a Khra or a Kriamiss or an Arren.. Unge came out of a time when anthropomorphic animals were new and exciting to me so that I took to drawing gelerts—strange, dog-like things from a website called Neopets—in skirts with big, lavender eyes. A terrible sight to behold. When I “adopted” a gelert someone had named Ungeschickt, the name disappointed me. I therefore had to make Ungeschickt—swiftly shortened to Unge for all intents, dues, and purposes—into the most badass of motherfuckers. And so, the first picture of Unge, ever, presented her as a femme fatale in a pink miniskirt and pearls, thoughtfully gesturing with her bloodied dagger. In this way, Unge was born of my love of James Bond, only to transmogrify, upon her entry into Khra, into a desire for a better world.

Unge stood at her window, overlooking the city of P’tak from its opulent heart. Xev had been dead for ten years.

It was 2 A.K., and Unge could hardly get used to the idea. Just the fact that the Demon was dead was nearly impossible to swallow after his reign of terror—the thousands of years of civilization burning under his sanguine gaze ended all at once, the shift demarcated by a change in calendar. Only the Elementals, who were as old as Khra itself, remembered a time before the Demon.

It had also been a year since Unge had met the hero who had slain Kifer: Arren Minetelle, a petite arctic fox raeth with ice blue eyes who arrived in P’tak wrapped in the crimson of a ranger’s cloak. At the time, the girl had pep, a raging fire in her spirit that did not compromise, and a conviction that hers was the right path, the just one. She appeared, determined to slay Kifer, armed with knowledge from that strange woman called Rhawen, and prepared to risk it all. Unge sent her to Nassab in search of an artifact the girl had called the Demon’s Eye and did not see her again until the Battle at the Elemental Fields. There, Unge had joined her forces—the agents of IMDP—with the Elementals’ and the Rangers’ in order to defeat Kifer and his army. Arren appeared amidst the fray, her left eye gone, replaced with a desiccated, angry orb more appropriate in the skull of a dead thing than that nineteen-year-old’s petite visage. Unge had naught to do but watch as the girl grappled with Kifer, tearing out the massive, glowing red stone that occupied his left socket. The Demon had screamed, his voice reaching an unearthly pitch of terror, and from Arren’s eye the desiccated thing leapt out with an angry hiss, falling into Kifer’s now-empty socket. All at once, the Demon exploded into dust. An entire Age sifted to the ground and disappeared into the soil.

After the battle, Arren was nowhere to be found, and the Ranger’s Head was discovered among the dead. Though Raeth celebrated Kifer’s death—such celebration Unge had never before seen—terror seized the Rangers’ ranks. For days they grappled with the sudden loss of Raeth’s and their leader while searching desperately for their hero. And then Arren returned, slogging out of the northern forests and stumbling westward to the Rangers’ Headquarters. The Rangers, the country’s populace, and even the Elementals, demanded that she be the new Head, this woman who had killed the world’s greatest evil. Yet she stood before them, her left socket still a ragged hole, the edges of the bone cracked, the skin scarring, and she said no.

Garron Baylinthe became the Head, and Unge should have been happy about that. The man was a native of P’tak, born and bred in the city’s love for technology, though woefully filled with its distrust of magic, too. Still, this should have been fortuitous for Unge, placing her and her city in a less precarious position with the rest of the nation. All the same, the moment filled her with an odd foreboding, and before long she found herself contacting Arren, asking one thing: watch the Rangers. Become a double agent. Miraculously, the hero had agreed.

Unge had never trusted the Rangers. They were, to her mind, a dangerous lot. Their Head was also Raeth’s Head, and while he was elected by the Raethian populace at large, Unge couldn’t help but wonder if the system could be rigged. Even when she was younger, breasts barely formed though she already yearned for a greater purpose, the fact that the Rangers were Raeth’s only police force, its only military filled her with dread, fear, and something acidic like bile. Where was the safety on that gun? Suppose, just suppose, that the Rangers ever went astray? Just suppose that they lost sight of their purpose, lost sight of their limits, lost sight of Raeth’s needs. What then? Who would be there to stop them? The Elementals didn’t bother themselves about Raethian business. The Mages were a scattered group of farmers’ helpers and wandering midwives. There was no one else.

For a long time, Unge struggled with that thought. Even when she set out from Nitemaer, determined to see the country in full, that sense of Ranger Danger followed her, with no feasible solution in tow. None, until Xev.

Twenty years ago, Xev said, “Aye, y’ve got th’ right regardin’ this Ranger thin’. We oughta do somethin’, t’change it, aye?” Xev was from N’zik, a small city surrounded by desert to one side and jungle to the other, previously the capital of an ancient Dragonfolk civilization, and now just one of the four Raethian settlements that could be properly called cities, one for each point of the compass. Unge was not terribly impressed with the southern city and found the accent unbearable, though she did think the use of sandstone was lovely.

“I know, but what’s there to do?” Unge was perhaps twenty-one at the time, a traveler for only two years who’d nonetheless done away with the decadent fabrics and elaborate constructions of Nitemaer’s garb in favor of the simple leather and cotton to be found in most Raethian villages. “I’ve been thinking about this for years, and still I don’t know.”

“No’ one though’ ‘t all?” Xev, a Dog Raeth all of sleek water hound blacks and dewy brown eyes, melted over the arm of his chair. He seemed impossibly long, his arms trailing across the floor, his toes hovering just above the ground.

“Well.” She paused, turning the thoughts over in her mind. “If you’ve got one organization in charge of everything, that’s a problem. But what if you had two?”

He raised an eyebrow. “Two?”

“Say you’ve got the Rangers, just as they are, but then you make, like, a second Rangers—‘cept call them something else obviously—“

“Aye.”

“—Well then you task the second group with not only defending the peace and all that good stuff, but also with keeping an eye on the Rangers. Then you go to the Rangers and say, ‘Hey, keep an eye on the new guys.’ So now you’d have double the police force and both would be making sure the other one didn’t slip up and go evil on us all.”

Xev smiled and reached out to touch Unge’s tawny hair. “Aye, why no’ do tha’, ey?”

Unge blinked, and one of her canine ears twitched. “Well, I mean, that’s not something I can do.”

Xev merely shook his head and offered her his hand.

Within a year, the foundations of IMDP, and the year after that, they began recruiting. Five years following that conversation, IMDP was complete with secret agents, a business front as an engineering corporation, and the cooperation of P’tak’s local government. The time had not seemed prudent to reveal themselves to the Rangers—much more effective to merely spy on them for now, until IMDP was of equal strength at least—and so the organization remained in shadow, its business practices slowly elevating it until the meaningless letters stood atop a skyscraper right at the opulent heart of P’tak, among the richest of the rich.

And then Xev died.

A knock, followed by Tarrin, Rien, and Arren Minetelle, all but Rien looking stoic. Unge turned, forty years of espionage squeezed into a tiny business suit, forty years of aggressive gaiety etched into her face. “Hello, my darlings.”

Tarrin and Arren sketched stiff salutes, each in their own style, and Tarrin pretended that she was not awed by Raeth’s Very Own Hero. Rien beamed, unfazed by the world’s going-ons, mind still tangling with gears and levers and electricity.

“What did Rhawen say?” Unge asked, settling into the plush chair behind her desk and gesturing for the trio to settle themselves where they saw fit.

Tarrin snorted, mouth opening to snarl about the peculiar woman, but Rien cut her off. “She doesn’t want to see anyone besides Arren right now.” The tiny girl adjusted her glasses. “Though she did like the things we brought her. Especially the mechanical pencils. Completely taken with them. She said plastic is a wonderful idea but to tell the folks in Nassab not to dig too deep. Not sure what she meant by that. ”

Unge rolled a pen on her desk. “But we can’t know where to find her?”

“No,” Arren said, a stone slab dropping. Her youth frightened Unge, sometimes. The ghastly eye socket, the runs in her face, deep-set, that made her look like marble, the ice blue of her remaining eye—just ice now—her hand never straying far from her sword’s pommel. And a sword in P’tak? It was strange. Arren looked entirely out of place in Unge’s modern office, and it was hard to remember that the office and P’tak were the anachronism here on Raeth, not Arren.

“No?” The pen rolled off of Unge’s desk.

Tarrin grumbled but held her tongue.

“Rhawen is not in a position to be as helpful as she’d like, and to that end it is better for her if as few people know her location as possible.” Arren allowed herself a sigh and continued, “I had thought that enabling you to go to her directly might not be asking too much, but Rhawen is adamant on this point. She is…”

“Yes, what is she?” Unge snapped, frustration surprising both her and the three women before her.

“Unge?” Rien squeaked. Unge shook her head.

One of the lines in Arren’s brow softened. “Rhawen is something of the world. Old. She has her reasons, and you will have to trust me that they are good. But I do understand your frustration… she has—”

“Well I’d feel a lot fuckin’ better about it if she’d just give us straight goddamn answers,” Tarrin growled.

The brow line reasserted itself. “Perhaps you should just get better at riddles then,” Arren said.

Unge pondered for a moment while Arren and Tarrin snapped at each other. She’d been working with Rhawen before Arren had killed Kifer, but the woman had never opened up to Unge the way she had to Arren, and even that was a chilly connection.

A wave of fatigue washed over her, and she missed Xev.

“Well thank you for trying, my lovelies,” Unge said, feeling herself sink onto her desk. “I suppose we’ll just do things the way we always have: we’ll wait.” Xev wouldn’t have tolerated this waiting. He’d have been trucking right up to Rhawen’s house and demanding answers, all with a pleasant smile.

Xev died on a mission of first contact.

Unge harbored two great dreams. The first: fix the Raethian judicial and political system to better prevent corruption. The second: re-establish diplomatic ties with Nassab and undo the political damage caused by the Great War, a thousand or so years ago. The trouble with this latter goal was, first and foremost, that a Human of Nassab would always kill and Raethian on sight, and most Raethians wouldn’t behave a whole lot more nobly. Oh, naturally, illegal trading had always occurred between the two continents—P’tak’s technological wealth was drawn directly from that fact—but Unge desired open trade. Raethian society was ruled by magic—the fact of the Elemental presence on the continent and lack of other natural resources ensured that—and Nassab, left without easy access to magic, had turned to technology. Unge wanted it both ways. Nitemaer was one of the few places that mixed the two lifestyles, and that hybrid mentality ran deep in Unge.

It was only natural that—observing the black market ships sailing between Bollen on Nassab and P’tak on Raeth—Unge determined that IMDP would certainly engage in some trading of its own and once begun, found their dealings with Bollen went well. Unge then thought to expand. To that end, she sent Xev to northern Nassab, and when he returned, he was merely a head in a box, a note pinned to the outside: “No Dogs.”

Unge shook the cobwebs from her mind. Tarrin and Rien had left, returning to their respective departments. Arren remained, sipping water and looking over Unge’s view of P’tak. Unge, at her side, pointed out through the city’s haze to where the ocean was just barely visible. “One of these days, that’s gonna be all boats all the time.” She smirked. “You won’t be the only Raethian to scoot around Nassab.”

Arren nodded, remaining eye closed. “Rhawen asked a favor of me.”

“Oh?”

From a pouch on her hip, Arren removed a small letter, some tiny object weighing down one of the envelope’s corners. It was sealed with orange wax—an odd choice—the imprint of what looked to be a dragon in flight squashed into the pumpkin color. An extinct animal for an ancient woman who didn’t look a day over twenty-five, apparently knew everything there was to know, and then refused to tell you? Sure. Why not dragons?

Unge took it to the desk and broke the seal. Alongside the letter, Rhawen had inserted a pendant matching the image impressed into the wax—one of those extinct dragons in flight. Unge ran her thumb over it, unsure of its connotation, though remembering that, on all the occasions she’d seen the woman, Rhawen had worn a pendant like it. She glanced at Arren, a question in her eyes, but Arren did not meet her gaze, sipping her glass of water instead. “How do you live in all this smog?” she wondered aloud.

Unge settled into her chair and read the letter.

Allow me just one more moment of your time, before you read Rhawen’s letter, before you decide if all this time spent poring over a day in Unge’s life and the moments of Rhawen’s and the musings of an author—the technical, real author, not Rhawen, the Narrator, who is the voice who tells these stories—was wasted.

Purpose applies to all of these situations. I don’t know what your life was like in 2001 or 2002, but I know what mine was like, and for all the material fortune in the world, I was nonetheless struck with a deep-seated misery that I couldn’t explain, and really I still can’t, at least not in a way that feels authentic. I was filled with guilt over this feeling—“There are children starving in Africa!”—and yet the feeling persisted until I became jealous of the starving children because at least they knew why they were miserable. It’s no surprise then that the characters I birthed were universally sad, universally restless, and universally struck with tepid misfortunes which, in theory, should be world-shattering, and yet in application remained ineffective. Kriamiss’s mother dies when he is fifteen, and he flees his home, finds the father that abandoned them and that man dies too, and then when he finds someone to love in the world, she kills him, and it isn’t until he’s been dead five hundred years that he has a second chance—to save the world, to become whole. My inability to feel anything at a degree less than acutely became his saga of misfortunes—too many to be useful, narrative-wise, but just enough to try to justify feeling the way I did.

So why feel so acutely? It’s hard to say. Do you blame a chemical imbalance; do you blame a spoiled upbringing; do you blame an inherent, genetic sensitivity; or do you perhaps put it down to some sort of flaw, a lack of the “right stuff”? I’m not sure; it’s all too far away to say anything concrete about. The memory is unreliable, the heart is unreliable, the mind is unreliable, even the evidence of the eyes is unreliable, because all is perception. In the present time, however, let us put it all down to purpose. There was purpose when we created, there was a loss of purpose when we stopped, and now we seek out purpose again—and so the whole world, the whole array of characters, have returned, because they cannot exist without us.

And how about Kriamiss or Unge? Why is it that every character I create is alone, at the end of the day, always by themselves, contained within the space of their own bodies, isolated? I am alone when I am with people; I am alone when I am not. Solitude, then purpose. We—the characters and me—travel alone and look for something to do. Something meaningful. Save the world, that’s always good, or maybe just improving it will do. Always with the epic narrative, always with the complete saga, and always with the search for purpose and the inescapable solitude.

I reiterate: the characters are me.

Unge—

Some twenty years ago, I sat on a café veranda in N’zik, and I watched a young Dog Raeth with tawny hair and a full bosom chitter and laugh with another young Dog Raeth, this one a sea of blacks and browns constructed into a long, lithe, lingering body. They laughed with one another, at one another, at themselves, caught in what I shall call puppy love. I saw, at that time, their histories and their presents, and while I have never been known to predict the future, everything I could sense about them suggested that they were bound for greater things. When, ten years ago, one of the two passed from this world on to Ahrk, I knew of this too, and I thought for a long time about how to make things right.

What answer can I give you? Arren sought out her own, and I supported her, and now, even with all the knowledge a mortal can be allowed, I find myself regretting. There lies Kifer, dead, and is not one girl’s youth worth the safety of thousands? But still the regret persists.

I digress.

You have a dream.

The Dragonfolk are waning, but their presence is still felt and revered in the northern climes of Nassab. Southern Nassab is, generally, filled with hatred for their once-oppressors, but in the north the sentiment is less present, the sins more forgiven, and so a Dragonfolk token can go a long way. Therefore, please find enclosed the symbol of the Dragonfolk; may it earn you passage to those places closed to all but the eldest. I will only ask that you do not use it to go to the Verde Isles.

With these thoughts in mind, I wish you well and tell you now that Xev died wishing for you.

Rhawen E. Fox

Unge choked and found, through her sobs, that Arren stood at her shoulder, merely holding it. The younger woman maintained that spot, one tired hand acknowledging Unge’s pain for the half hour it took the older woman to regain herself, her gaiety washed away by a ten-year-old memory of a dead man.

When Unge had subsided, Arren took herself to the other side of the desk and sat down. She folded her arms on the black, sanitized wood, her posture suddenly more like the girl she should have been. Eyes hard on Unge, she said, “I’ve known tears like that.”

Unge nodded. “Xev was—he made this. All of this. Just by saying it was possible. Just ‘You can do it, Unge. This can be done.’ And then it was. That was all it took. He said I could do it, so I did.” Her breath rattled. “How do you come back from that? How do you answer for that death?”

Arren took her hand and gave it a squeeze. Unge could feel every crease, every callous in the hero’s hand. Here was where her sword had worn itself a home, and here at the finger tips the place for her bow. These tiny nicks for every hour of traveling from one Raethian coast to the other and these weathered folds for every night spent alone beneath the stars formed a web in which to catch demons. Arren’s nails were dirty, but in spite of the usage written across her hands, Unge could see where once the delicate shape of a genteel woman’s glove may have fit, and Unge’s own palm felt suddenly fat and unwieldy in the grasp of one so conflictingly worked.

Arren withdrew, her whole self drawn back up into the raw eye socket, sucked behind a glacial mask. She stood, saying, “The Rangers will miss me momentarily. Baylinthe’s put his son and Brue Nadir as his top officers. Most of the men are terrified of Brue, which leaves me and the boy to see that morale stays up.”

Unge closed her eyes, nodding her understanding, but found Arren leaning in when she’d opened them again.

“The boy. Maroc Baylinthe. He might be trouble.”

There seemed something more she wanted to say, and Unge prompted her—“How so?”—but Arren shook her head and stepped away. “It may just be me. The men love him.” A tightness around her mouth suggested a deeper trouble, but Arren put it off. “No, it is nothing. He is a Ranger, after all.” With that, Arren saluted, said her farewells, and whisked out of the room, just a red cloak disappearing behind metal doors.