#world atlas of linguistic structures

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Hello Grambank! A new typological database of 2,467 language varieties

Grambank has been many years in the making, and is now publically available!

The team coded 195 features for 2,467 language varieties, and made this data publically available as part of the Cross-Linguistic Linked Data-project (CLLD). They plan to continue to release new versions with new languages and features in the future.

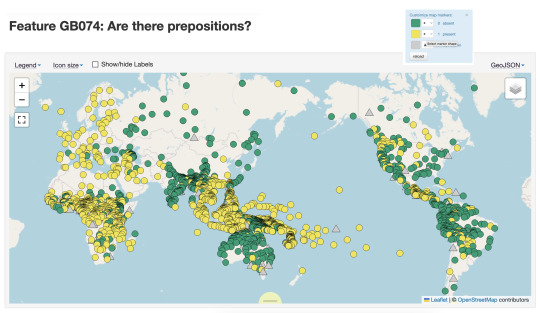

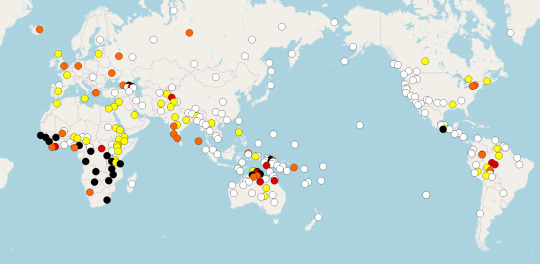

Below are maps for two features I’ve selected that show very different distribution across the world’s languages. The first map codes for whether there are prepositions (in yellow), and we can see really clear clustering of them in Europe, South East Asia and Africa. Languages without prepositions might have postpostions or use some other strategy. The second map shows languages with an existential verb (e.g. there *is* an existential verb, in yellow), we see a different distribution.

What makes Grambank particularly interesting as a user is that there is extensive public documentation of processes and terminology on a companion GitHub site. They also have been very systematic selecting values and coding for them for all the sources that they have. This is a different approach to that taken for the World Atlas of Linguistic Structures (WALS), which has been the go-to resource for the last two decades. In WALS a single author would collate information on a sample of languages for a feature they were interested in, while in Grambank a single coder would add information on all 195 features for a single grammar they were entering data for.

I’m very happy that Lamjung Yolmo is included in the set of languages in Grambank, with coding values taken from my 2016 grammar of the language. Thanks to the transparent approach to coding in this project, you can not only see the values that the coding team assigned, but the pages of the reference work that the information was sourced from.

433 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rare intonation patterns in the world's languages

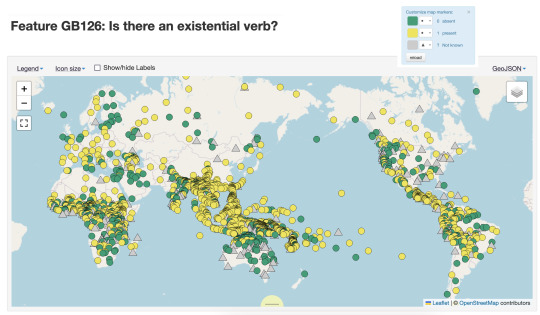

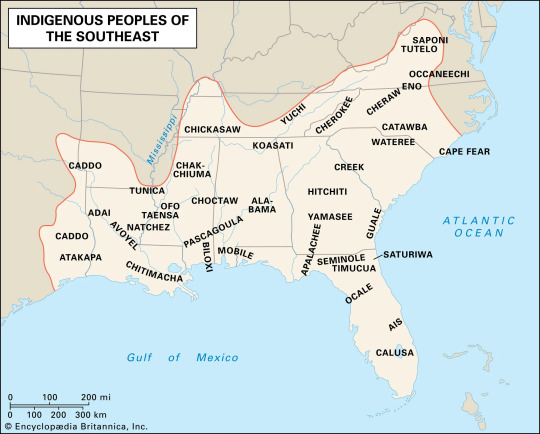

Chitimacha is one of the rare languages which uses rising intonation for statements and falling intonation for questions and commands (Swadesh 1946: 317).

This chart using languages from the World Atlas of Language Structures shows just how infrequent this pattern is in the world’s languages (Gordon 2016: 245).

Interestingly, the nearby Chickasaw language also has this unusual pattern, even though the two languages are unrelated (Gordon 2016: 245).

You can learn all about the sound systems of the world’s languages in the excellent book Phonological typology. (The book is aimed at linguists rather than a general audience. An intro linguistics class is probably a prerequisite for the book.)

References

Dryer, Matthew S. & Haspelmath, Martin (eds.). 2013. The world atlas of language structures online. https://wals.info/.

Gordon, Matthew K. 2016. Phonological typology (Oxford Surveys in Phonology & Phonetics 1). Oxford University Press.

Swadesh, Morris. 1946. Chitimacha. In Harry Hoijer (ed.), Linguistic structures of Native America, 312–336. Viking Fund.

#intonation#linguistics#language#lingblr#langblr#Chitimacha#Chickasaw#Native American#Native#Indigenous#phonology#typology

108 notes

·

View notes

Text

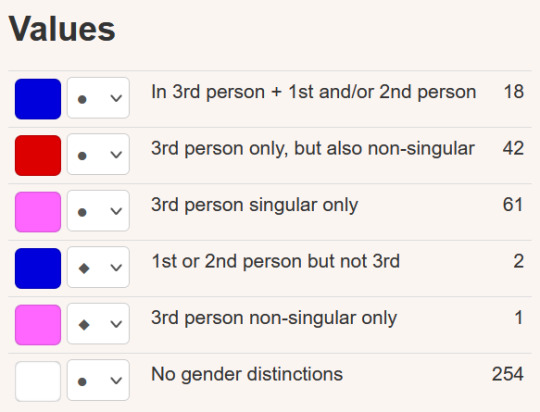

Ann Leckie’s Imperial Radch series burst upon the SFF world in 2013, drawing notice for (among other things) its linguistic worldbuilding. The Imperial Radch, the central power of the series, speaks a language that lacks any gender distinction in the pronouns. Linguistically, this feature in itself is hardly unusual. There are many languages spoken today (on Earth) that do not distinguish gender in their pronoun systems, ranging from Imbabura Quichua in Ecuador (pai), to Finnish (hän), to 252 other languages listed in the World Atlas of Language Structures as lacking all gender distinctions in their pronoun system (Siewierska, 2013).

[...]

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some wonderful databases for analysis of worldwide languages:

CLLD (Cross-Linguistic Linked Data): the mother database collecting all others

WALS (World Atlas of Language Structures): showing the worldwide distribution of linguistic features (e.g. sound inventories or types of syntax)

CLICS3 (Cross-Linguistic Colexifications): showing the patterns in which languages use the same word to cover multiple concepts

WOLD (World Loanword Database): showing which words are more likely to be borrowed between unrelated languages (there are some fales negatives)

PHOIBLE: database of phonetic inventories

IDS (Intercontinental Dictionary Series): a standardized compilation of dictionary, with words classified by topic, for >300 languages (very detailed with Southeast Asia and South America, very sparse for Africa and East Asia)

16 notes

·

View notes

Note

I saw your post about #tag linguistics and it was fascinating! I was wondering if you knew any online resources/references describing the phonotactics of different languages for a mostly inexpert audience? When I poke around with my meager googling I tend to only turn up English, but I'd be really curious to see the basic rules laid out for comparison among a few different languages!

Oi! Hey there! ^.^ Hope you're doing well and thanks for the kind words!

Unfortunately I've been out of the academic loop since 2016 and I only remember a handful of resources, most of which aren't inexpert audience friendly(?).

The resource that pops to mind, regardless, is WALS Online - The World Atlas of Language Structures Online. It's a cross-linguistic feature comparison tool. It allows you to generate and investigate global maps based upon a single linguistic feature or multiple features simultaneously. I think it's a cool shortcut because it checks plausibility (for people who might not know interrelatability) on whether a language might have a combination of features. It helps visualize patterns across languages, language families, and regions.

For instance, since we're talking phonotactics, here's the map for syllable structure. Problem is WALS pulls no punches on jargon, and most of the sources it cites are, like, grammars you'd only find in print on a campus library.

On WALS, each language has a page where its features are listed. To learn the details of how the feature manifests, you'd have to use other sources. But WALS at least provides the relevant starting point of individual languages to investigate. Wikipedia ain't... always accurate or comprehensive, of course, in something like linguistics... but it's an easy way to start poking once you know the names of languages you want to snoop at.

You could try your luck with the currently-defunct World Phonotactics Website on the Wayback Machine, though that's not one I know much about, and there is the whole, uh, defunct thing going for it.

I'm sorry I can't be more help!

Nice stopping in, and thanks for the kind words of that viral post. Funny (if typically tumblr) story about that. I posted it eight years ago intentionally at an off hour of night in hopes it'd get two notes and fade into obscurity. That's why it has nicher fandom-specific references; it wasn't anticipated to escape containment, just be a convo between two friends. Yeah oops bwahaha. Gosh I was so energized at the time. Anymore I don't think it holds up remotely, factually, from any academic standing, and the inaccuracies make me twitch, but I doubt most people notice, and I hope it gives people the fun and excitement about linguistics I was feeling. ^.^ Linguistics is so cool!! And I s'pose it's been cool that one of my most-spread posts is nerdy. Oh, alas, science side of tumblr, I was amongst y'all once.

#if some of the more academically active linguists who follow me / are mutuals recall something#please holler [sweats] XD#blabbing Haddock#ask#ask me#phonotactics#linguistics#lingfishtics#non-dragons#spaceshipoftheseus#my job is still in linguistics but I feel like an imposter whoooop shhhhh;hhhhhh

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

so this post by @icebluecyanide greatly brings to attention how the majority of languages in the world don't have gender marking for pronouns, though the list in it is pretty limited. it's understandable not to know these things depending on what languages you speak or are exposed to, and the reblogs (while they do have the spirit) are a bit confused. science education however is my passion so here are some visualizers and clarifications on gender in languages!

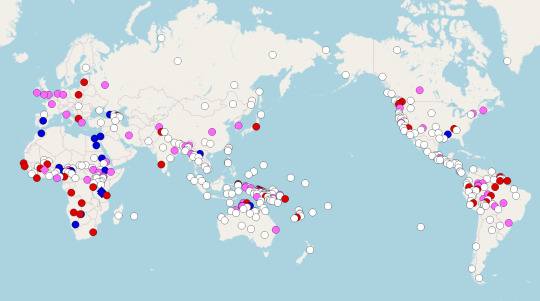

first, a look at gender marking in pronouns.

as pointed out in the post, it is uncommon to have gender marking in pronouns - only about 30% of languages do it, while the vast majority of languages omits the distinction. you'd be forgiven for finding this surprising! gender opposition in pronouns is common in european languages, with africa being another prominent area for gender marking. gender distinction in pronouns is usually sex-based (masculine and feminine and sometimes neuter(s)).

next, to address the confusion in the reblogs! the last reblog spoke of number marking in pronouns, or "the amount of subjects". they mention differentiation between two or more subjects (dual-plural) and whether the speaker or listener (or both) are included (inclusivity-exclusivity). grammatical number and clusivity vary in languages, and even more distinctions exist than mentioned! but as they are separate from gender, i won't get into them here.

one reblog by @assuming-dinosaur states that english is "highly unusual among languages in having grammatical gender align so precisely with the social concept of gender". they also mention multiple interrelated phenomena related to noun class/gender systems. clarifications:

languages vary in how grammatical gender/class is assigned to nouns - some languages assign gender solely based on the meaning of the word (e.g. "woman" is feminine), or additionally based on form or pronunciation (e.g. all words ending in "-a" are feminine).

"gender" in linguistics means a system for categorizing nouns, alternatively called "noun class". while these systems can have significant overlap with the social and cultural concepts of gender/sex, as mentioned in the reblog, there are lots of systems whose criteria for noun categorization are unrelated to "natural gender". in addition to sex and pronunciation as factors in assigning grammatical gender, grambank features factors such as shape, animacy and plant-status.

modern english does not, for the most part, have grammatical gender, so it's a bit silly to compare its pronouns to languages with wider-reaching gender systems. as stated above, the masculine/feminine/neuter distinction in pronouns is very common worldwide. and even in english, the alignment isn't 100% precise - e.g. ships and churches may also be referred to as "she".

many languages have a gender system that utilizes multiple factors for noun class assignment. of languages with gender systems in wals's sample, a majority include some sex-based distinction. all non-sex-based systems in the sample were based on some kind of animacy, most often human vs. non-human, or animate vs. inanimate. there's plenty of variation in what is considered animate, though! (in sumerian, for example, humans, gods, and statues (sometimes) were animate, while slaves, among others, were classified as inanimate.)

and yet, after such a long ramble on gender systems, let us remember that languages with gender/noun class systems are in the minority.

ending on this lovely map demonstrating on one hand how common it is to not have grammatical gender, and on the other, the variety of existing gender systems!

all maps and articles linked here are from wals, the world atlas of language structures, as well as grambank, two wonderful typological databases. wals's language sample size is quite small, but the maps and articles are still very useful and informative for typological comparison. for a larger sample size visit grambank! here's their article on gender in third person pronouns and sex-based noun class systems.

#linguistics#linguistics tag#language#bro i was supposed to go out but instead i spent way too long writing this#some wikipedia links. they do have information that should suffice as a primer if you don't wanna get Into It#text#also to people @d here this isn't a callout lmao just clearing up some things and providing more info

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

Here is my linguistics question:

Do you feel there is any benefit to the idea of an "inclusive we" and an "exclusive we", like a we that includes the people the user is speaking to, and a we that excludes them?

For example, if Alice and Bob went to the store and then Alice was talking to Carol, she could say "We went to the store" using the exclusive we, to indicate that thought she is using a plural pronoun, Carol in not included. But if Alice was talking to Bob, she could say, "We went to the store" and use the inclusive we, because she is talking about both of them. I think in the case where she addresses both she would still use exclusive, because even though Bob was present, Carol was not.

I feel those were bad examples for why I care about this. Sometimes I use "we" because multiple people including myself did something, but then I feel concerned the people I am talking to might get confused and think that I thought they were involved, or if it was something in the past, maybe even think maybe they were involved.

Anyway, my questions are the following:

Does this concept already exist, does it have a real name (inclusive/exclusive is just what I call it because I am a math person), and are there any languages that you know of that have this sort of pronoun?

2. Whether or not it exists, do you (as someone who has studied linguistics) feel it is a useful concept? Does it convey useful information or does it add too much complexity to pronouns?

3. Is the idea of exclusive we being used for a group of mixed included and excluded people make sense? If this concept actually exists, does inclusive or exclusive get used for mixed group? Would using the inclusive form make more sense for the mixed group?

Thank you for your time.

Oh okay that's really interesting. Just want to clarify I only have an undergraduate degree in linguistics and this particular subject isn't something I've studied in detail, but I do know a little bit.

1. It does, and I've heard inclusive/exclusive as the standard term actually, with "clusivity" used sometimes to describe the concept itself. It occurs in many languages, for example it's common in Australian and Austronesian languages, as well as the Dravidian language family. The World Atlas of Language Structures online has a page showing distribution here:

2. I think it's definitely a useful concept. I know there's been times in English conversations I would've benefited from it. Of course, we can get along without marking it explicitly too, but it could help. I mean, maybe if you're concerned about this miscommunication, you could just clarify in other terms to people to make sure? But like, it is a really cool system and probably helps in a lot of circumstances.

3. I'm not quite sure about this, I think in a mixed group you would probably still need context cues to know who was included? The way I've heard it generally relies on whether it includes whoever is being addressed, but I don't know if maybe some languages might have a way to make more specific distinctions?

Anyone out there know more about this? This is really fascinating, sorry I don't know more but thank you for talking to me about it!

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

So, interesting fact: On a global level, languages with gendered pronouns are actually in the minority. The fact that most European languages have gendered pronouns makes it seem like that's the norm, but in fact, lack of gendered pronouns is much more common. According to WALS (the World Atlas of Linguistic Structure), of a random sample of 378 languages, 254 (67.2% - just over 2/3) have no gendered pronouns

I love using any/all pronouns. Transphobes literally cannot misgender me even if they try

558 notes

·

View notes

Audio

Lingthusiasm Episode 38: Many ways to talk about many things - Plurals, duals and more

In English you have one book, and three books. In Arabic you have one kitaab, and three kutub. In Nepali it’s one kitab, and three kitabharu, but sometimes it’s three kitab.

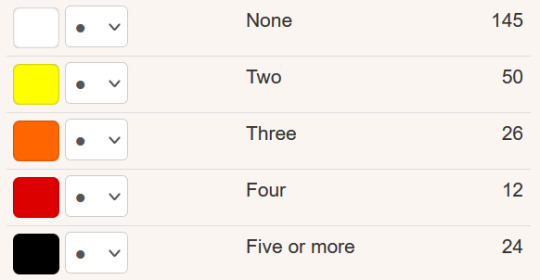

In this episode of Lingthusiasm, Gretchen and Lauren look at the many ways that languages talk about how many of something there are, ranging from common distinctions like singular, plural, and dual, to more typologically rare forms like the trial, the paucal, and the associative plural. (And the mysterious absence of the quadral, cross-linguistically!)

Click here for a link to this episode in your podcast player of choice or read the transcript here

Announcements:

It’s also our anniversary episode! We’re celebrating three years of Lingthusiasm by asking you to share your favourite fact you’ve learnt from the podcast. Share it on social media and tag @lingthusiasm if you’d like us to reshare it for other people, or just send it directly to someone who you think needs a little more linguistics in their life.

This month’s bonus episode was about reading fiction as a linguist! Check out our favourite recs for linguistically interesting fiction and get access to 30+ additional episodes if you’ve run out of lingthusiasm to listen to, by becoming a member on Patreon.

Here are the links mentioned in this episode:

World Atlas of Language Structures

WALS feature 33A: Coding of Nominal Plurality

WALS feature 34A: Occurrence of Nominal Plurality

Nepali plural (Wikipedia)

Arabic plural (Wikipedia)

Kinyarwanda plural (Wikipedia)

Indonesian plural (Wikipedia)

Tetum plural (Wikipedia)

Suppletion (Wikipedia)

Lingthusiasm Episode 2: Pronouns. Little words, big jobs

Lingthusiasm Episode 16: Learning parts of words - Morphemes and the wug test

Dual (Wikipedia)

Second personal dual pronoun (Superlinguo)

Trial & Quadral (Wikipedia)

Paucal (Wikipedia)

Monolingual field methods demonstration

You can listen to this episode via Lingthusiasm.com, Soundcloud, RSS, Apple Podcasts/iTunes, Spotify, YouTube, or wherever you get your podcasts. You can also download an mp3 via the Soundcloud page for offline listening.

To receive an email whenever a new episode drops, sign up for the Lingthusiasm mailing list.

You can help keep Lingthusiasm ad-free, get access to bonus content, and more perks by supporting us on Patreon.

Lingthusiasm is on Twitter, Instagram, Facebook, and Tumblr. Email us at contact [at] lingthusiasm [dot] com

Gretchen is on Twitter as @GretchenAMcC and blogs at All Things Linguistic.

Lauren is on Twitter as @superlinguo and blogs at Superlinguo.

Lingthusiasm is created by Gretchen McCulloch and Lauren Gawne. Our senior producer is Claire Gawne, our production editor is Sarah Dopierala, our production manager is Liz McCullough, and our music is ‘Ancient City’ by The Triangles.

This episode of Lingthusiasm is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial Share Alike license (CC 4.0 BY-NC-SA).

#language#linguistics#episodes#episode 38#plural#morphology#number#grammar#nepali#arabic#indonesian#english#kinyarwanda#french#tetum#languages#proto indo european#dual#proto-indo-european#trial#paucal#singular#wals#world atlas of linguistic structures#typology#linguistic typology#linguistic fieldwork#field linguistics

78 notes

·

View notes

Note

Any tips for a non-linguist attempting to create a fantasy language?

Hey! So! This is a great question, but not one I'm really equipped to answer. Because I'm not conlanging in the traditional way (by the seat of my pants while drawing on years of linguistics nerdery and advice from internet forums), a lot of the resources I'm using are ones provided to me by a linguistics professor, and therefore, for copyright and doxxing reasons, ones I can't share. What I can do is give you some very basic tips, a non-risky resource or two to help you get started, and a call for other people who dabble in conlangs to supply resources as well.

The first most basic thing I can advise is to figure out exactly what you want your language to do worldbuilding-wise, because that's going to define a lot of where you put your time and effort. For example, I want Dathomiri to recontextualize the awful, ridiculous, deeply misogynistic and cisnormative worldbuilding around the Nightsisters of Dathomir, which means I'm going to need to spend a lot of time thinking about how I want the pronouns and classes to work.

The second thing to do is to figure out which areas of your language you want to be naturalistic (it can be all of them! a lot of conlangs are made that way), and how naturalistic you want them to be. Because languages are incredibly complex, making a conlang as complex as a natural language in natural ways can take years and years and, for people who aren't Tolkien—who btw didn't even end up with a fully usable conlang—usually isn't worth it.

Of course there's room for changing your mind once you've decided on them, and not everything you toss into a language has to work exactly with your goals, but I think it can be really useful to have guidelines to help you decide which things you're going to keep in or throw out.

What you do after you've decided what you want to do is going to depend a lot on your existing knowledge of not just conlanging but linguistics in general. It's common (and best, in my opinion) practice to start with the phonetics of your language—what sounds it contains—but if you don't know how big most phonetic inventories are, or what patterns show up in them, even that can be rough.

Because I don't know where you're at knowledge-wise, and because I'm about the furthest thing you can get from an expert in linguistics, I'm not going to provide any more advice. We could get lost for days in phonetics, and weeks just on what I know of phonology (my current preferred branch), so instead I'll take this opportunity to list some resources:

First, David Peterson's book The Art of Language Invention. It's an easy read, and oriented towards people who know nothing about linguistics, so it's a really good place to start for a crash course in the basic parts of language.

Second, the World Atlas of Language Structures (https://wals.info/). Peterson's book is good for the basics, but it doesn't supply much in the way of typological information (i.e. what features occur in languages + to what frequency and where). WALS is a great database for looking at where different features of language pop up, and how often they do, which can inform a lot of your decisions about how to implement naturalism (if that's what you're trying to do).

Third—and this one both @mandaloriandy, who knows more about conlanging than me, and my professor recommended—is this word generator (https://zompist.com/gen.html). It can be really helpful for figuring out the phonology of your language—how segments are arranged—as you have to enter your phonological and phonotactic rules for it to generate a wordlist. There's also a sound change applier (https://zompist.com/sca2.html) if you're trying to evolve a language forwards or backwards, though that one I haven't ever used.

I wish I had more to give you, but a lot of what I've done so far has come from my own knowledge of phonology or from a few offhand comments from my professor/his powerpoints. I'll put out a call for resources in the tags so hopefully you'll be able to find some in the reblogs or replies, but beyond that google is probably going to be your best bet.

Sorry I couldn't help more. Good luck!

#any and all conlangers or conlang-interesteders PLEASE drop some resources in the replies#conlangs#asks#lunathethestral

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy pride! Let’s talk about pronouns, gender, and the importance of making space for diverse understandings of both.

Pronouns are words that replace nouns. Not every language has pronouns. Of the languages which have pronouns, other grammatical elements may be added to pronouns to convey additional meaning. For example, many languages with pronouns have singular pronouns (referring to one noun), dual pronouns (referring to two nouns), and/or plural pronouns (referring to multiple nouns). Another common feature of pronouns is person. Languages may have first person pronouns (referring to the speaker), second person pronouns (referring to the listener), and/or third person pronouns (referring to another noun).

Then there’s grammatical gender. Grammatical gender is sometimes called “noun class”. (Linguists disagree on whether grammatical gender and noun class are the same thing or if grammatical gender is a subset of noun class. Don’t worry about it too much.) Basically, noun classes are groups of nouns that have 1+ feature in common. Features can include things like:

gender - a common gender division is masculine/feminine/neuter

animacy - usually living/non-living, sometimes moving/non-moving

quality - size, substance, species

Grammatical gender contrasts with “natural gender”. Natural gender is a linguistic property that conveys the gender of the referent. From here on out, I will refer to words with natural gender as “gendered terms”. English does not have noun classes, but it does have gendered terms, e.g. “woman”, “man”, “girl”, “he”, “she”.

“Gendered” pronouns, depending on the language, may or may not be related to cultural understandings of gender*. In English, third person singular pronouns “he” and “she” almost always function as gendered terms. For languages with noun classes, pronouns may also correspond to the grammatical gender or class of the noun referent. The Spanish word “mesa”, meaning table, is a feminine noun, and is replaced by feminine pronoun “ella”. There is nothing inherently feminine about a table - using “ella” to refer to a table only reflects the noun class. However, “ella” can also function as a gendered term when referring to a human.

On the English-speaking internet, gender and pronouns are often treated as direct equivalents - specifically, English pronouns. “theythems” is used as a substitute for nonbinary people. Reducing gender down to English pronouns reinforces the idea that queerness is something Western and modern, and erases the history of gender diversity around the world. For languages that have gendered pronouns, these are treated as direct equivalents of English, and queer people debate how best to translate "they” into their own language - sometimes even in situations where there already were gender neutral pronouns, and Western contact is the only reason gendered elements were added.

Transness is not exclusive to English speakers. Non-native English speakers and non-English speakers do not need to make their genders palatable or understandable to us. Your gender doesn’t have to line up to one - or even multiple - English pronouns. It doesn’t have to be expressible in English at all.

Understandably, many people have strong associations between their gender identity and their pronouns. I’m not trying to invalidate people who feel this way. I just want everyone to keep in mind that language and cultural understandings of gender vary greatly from community to community. There is no correct way to be queer or trans. Let’s celebrate us in all our diversity.

🏳️🌈🏳️⚧️🏳️🌈🏳️⚧️🏳️🌈🏳️⚧️🏳️🌈🏳️⚧️🏳️🌈🏳️⚧️🏳️🌈🏳️⚧️🏳️🌈🏳️⚧️🏳️🌈🏳️⚧️🏳️🌈🏳️⚧️🏳️🌈🏳️⚧️🏳️🌈🏳️⚧️🏳️🌈🏳️⚧️🏳️🌈🏳️⚧️🏳️🌈🏳️⚧️🏳️🌈🏳️⚧️🏳️🌈

If you’re interested in learning which languages have pronouns and which languages have gendered pronouns, check out the World Atlas of Language Structures.

*Also of note: the grammatical and natural gender of a word do not have to match! German has three genders: masculine, feminine, and neuter. The German word “Mädchen” means girl - it is a gendered term, because it implies that the referent is feminine. However, “Mädchen” is not grammatically feminine - it is actually grammatically neuter.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

A rant against Karen Traviss' understanding of history and her FAQ answers

Did you base the Mandalorians on the Spartans?

<cite> No. I didn't. </cite> Fair enough.

<cite> I really wish history was taught properly - okay, taught at all - in schools these days, because history is the big storehouse that I plunder for fiction. It breaks my heart to hear from young readers who have no concept even of recent history - the last fifty years - and so can't see the parallels in my books. You don't have to be a historian to read my novels, but you'll get a lot more out of them if you explore history just a little more. Watch a history channel. Read a few books. Visit some museums. Because history is not "then" - it's "now." Everything we experience today is the product of what's happened before. </cite> Yeah, I do to. Please, Ms Traviss, go on, read some books. Might do you some good. And don't just trust the history channels. Their ideas about fact-checking differ wildly.

<cite> But back to Mandos. Not every military society is based on Sparta, strange as that may seem. In fact, the Mandos don't have much in common with the real Spartans at all. </cite> You mean apart from the absolute obsession with the military ["Agoge" by Stephen Hodkinson], fearsome reputation ["A Historical Commentary on Thucydides" by David Cartwright], their general-king ["Sparta" by Marcus Niebuhr Tod], the fact that they practically acted as mercenaries (like Clearch/Κλέαρχος), or the hyper-confidence ("the city is well-fortified that has a wall of men instead of brick" [Plutarch, Life of Lycurgus])...

<cite> A slightly anarchic, non-centralized, fightin' people? Sounded pretty Celtic to me. Since I went down that path, I've learned more about the Celts (especially the Picts), and the more I learn, the more I realise what a dead ringer for Mandos they are. But more of how that happened later... </cite>

The Celtic people are more than one people, more than one culture. Celtic is a language-family! In the last millennium BC nearly every European ethnic group was in some ways Celtic, and they were not one. Later, after the Germanic tribes (also not one people, or a singular group) moved westwards, the Celtic cultures were still counted in the hundreds. Not only Scotland was Celtic! Nearly all of Western Europe was (apart from the Greek and Phoenician settlers on the Mediterranean coasts). The word “Celts” was written down for the first time by Greek authors who later also used the word “Galatians”. The Romans called these people “Gauls”, and this word was used to describe a specific area, bordered by the Atlantic Ocean, the Cévennes and the Rhine: “Gaul”. So the Celts, the Galatians and the Gauls were all part of the same Celtic civilisation. "Celts, a name applied by ancient writers to a population group occupying lands mainly north of the Mediterranean region from Galicia in the west to Galatia in the east [] Their unity is recognizable by common speech and common artistic traditions" [Waldman & Mason 2006] Mirobrigenses qui Celtici cognominantur. Pliny the Elder, The Natural History; example: C(AIUS) PORCIUS SEVERUS MIROBRIGEN(SIS) CELT(ICUS) -> not just one culture "Their tribes and groups eventually ranged from the British Isles and northern Spain to as far east as Transylvania, the Black Sea coasts, and Galatia in Anatolia and were in part absorbed into the Roman Empire as Britons, Gauls, Boii, Galatians, and Celtiberians. Linguistically they survive in the modern Celtic speakers of Ireland, Highland Scotland, the Isle of Man, Wales, and Brittany." [Celtic Culture: a historical encyclopedia. by John Koch] "[] the individual CELTIC COUNTRIES and their languages, []" James, Simon (1999). The Atlantic Celts – Ancient People Or Modern Invention. University of Wisconsin Press. "All Gaul is divided into three parts, one of which the Belgae live, another in which the Aquitani live, and the third are those who in their own tongue are called Celtae, in our language Galli." [Julius Caesar, De Bello Gallico] <= I had to translate that in school. It's tedious political propaganda. Read also the Comentarii and maybe the paper "Caesar's perception of Gallic social structures" that can be found in "Celtic Chiefdom, Celtic State," Cambridge University Press. The Celtic tribes and nations were diverse. They were pretty organized, with an academic system, roads, trade, and laws. They were not anarchic in any way. They were not warriors - they were mostly farmers. The Celts were first and foremost farmers and livestock breeders

The basic economy of the Celts was mixed farming, and, except in times of unrest, single farmsteads were usual. Owing to the wide variations in terrain and climate, cattle raising was more important than cereal cultivation in some regions.

Suetonius addressing his legionaries said "They are not soldiers—they're not even properly equipped. We've beaten them before." [not entirely sure, but I think that was in Tacitus' Annals]

Regarding the Picts, in particular, which part of their history is "anarchic"? Dál Riata? the Kingdom of Alba? Or are you referring to the warriors that inspired the Hadrian's Wall? Because no one really knows in our days who the fuck they were. The Picts’ name first appears in 297 AD. That is later. <cite> Celts are a good fit with the kind of indomitable, you-can't-kill-'em-off vibe of the Mandos. Reviled by Rome as ignorant savages with no culture or science, and only fit for slaughter or conquest, the Celts were in fact much more civilized than Rome even by modern standards. </cite> That's how the Romans looked at pretty much every culture that wasn't Greek, Roman, Phoenician, Egyptian, or from Mesopotamia (read, if you want, anything Roman or Greek about the Skyths, the Huns, Vandals, Garamantes...).

<cite> They also kicked Roman arse on the battlefield, and were very hard to keep in line, so Rome did what all lying, greedy superpowers do when challenged: they demonized and dehumanized the enemy. (They still used them in their army, of course, but that's only to be expected.) </cite> They were hard to keep in line, but they most definitely did not kick Roman arse on the battlefield. Roman arse was kicked along the borders of the Roman Empire, such as the Rhine, the Danube, the Atlas mountains, etc. And mostly by actually badly organized, slightly anarchic groups, such as the Goths or the Huns (BTW the Huns were not a Germanic people, even though early 20th century British propaganda likes to say so). Though they were also decisively stopped by the Parthians. Who were very organized. Ah well. <cite> While Rome was still leaving its unwanted babies to die on rubbish dumps - a perfectly acceptable form of family planning to this "civilisation" - and keeping women as chattels devoid of rights, the barbarian Celts had a long-standing legal system that not only gave women what we would think of as equal rights, but also protected the rights of the elderly, children, and the disabled. They had a road network across Europe and worldwide trade long before the Romans ever got their act together. And their science - well, their astronomical calculations were so sophisticated that it takes computers to do the same stuff today. </cite> See? You even say yourself that they weren't actually anarchic. Also you're not completely right: 1. women (of most Celtic cultures, with one notable exception being the Irish) were not allowed to become druids, e.g. scientists, physicians, priests, or any other kind of academics, so they did not have equal rights. Also, as in other Indo-European systems, the family was patriarchal. 2. the roads they had were more like paths, and did not span the entirety of Europe; the old roads that are still in use are nearly all of them Roman. Had the Celtic inhabitants of Gallia or Britannia built comparable roads, why would the Romans have invested in building a new system on top? 3. world-wide? Yeah, right. They traded with those who traded with others and so were able to trade with most of southern Eurasia and northern Africa, as well as few northern parts (Balticum, Rus), but that's (surprise) not the whole world. 4. most people use computers for those calculations you mention because its easier. It's not necessary. I can do those calculations - give me some time to study astronomy (I'm a math major, not physics) and some pencils and paper. 5. and - I nearly forgot - the kids didn't die. That was a polite fiction. The harsh truth is that most Roman slaves were Romans... <cite> So - not barbarians. Just a threat to the empire, a culture that wouldn't let the Pax Romana roll over it without a fight. (Except the French tribes, who did roll over, and were regarded by the Germanic Celts [...]) </cite> WTF Germanic Celts? What are you smoking, woman? Isn't it enough that you put every culture speaking a language from the Celtic family in one pot and act as if they were one people, now you have to mix in a different language-family as well? Shall we continue that trend? What about the Mongolian Celts, are they, too, proof that the Celts were badass warriors? I think at this point I just lost all leftover trust in your so-called knowledge. <cite> [...] as being as bad as the Romans. Suck on that, Asterix... </cite> Asterix was definitely a Celt, and unlike the British Celts, he was not a citizen of the Roman Empire.

<cite> Broad brush-stroke time; Celts were not a centralized society but more a network of townships and tribes, a loose alliance of clans who had their own internal spats, but when faced with some uppity outsider would come together to drive off the common threat. </cite> They might have tried, but they didn't. The first and only time a Celtic people really managed to drive off some uppity outsider would be 1922 following the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921*. The fact that France, Spain, Portugal speak Romance languages and the British (or Irish) Isles nearly uniformly speak English should be proof enough.

*Unless you count Asterix. <cite> You couldn't defeat them by cutting off the head. There was no head to cut off. </cite> You mean unlike Boudica and Vercingetorix. Oh wait. Tacitus, in his Annals, said that Boudica's last fight cost 80,000 Britons and 400 Romans their lives. He was probably exaggerating. But it definitely stopped much of the British resistance in its tracks. <cite> To the centralized, formal, rather bureaucratic Romans, for whom the city of Rome was the focus of the whole empire, this was a big does-not-compute. The Celts were everything they didn't understand. And we fear what we don't understand, and we kill what we fear. </cite> While that is totally true, it's also completely off the mark. The Romans demonized the druids, not every Celt, and they were afraid of what was basically an academic network. That had nothing to do with war. <cite> Anyway, Mandos....once I took a single concept - in this case, the idea of clans that operated on a loose alliance system, like the Celts - the rest grew organically. I didn't plan it out in detail from the start. </cite> That's really obvious. Maybe looking at some numbers and remembering that you weren't planning a small, local, rural, medieval community would have helped, too. I mean lets have a look at, say, Scotland (since you specifically mentioned the Picts): they still have less than 6 mio. people all together, and that's today. Mandalore is a sector. A sector of Outer Space with at least 2000 inhabited planets. How do you think that translates? It doesn't. <cite> I just asked myself what a culture of nomadic warriors would value, how they would need to operate to survive, and it all grew inexorably by logical steps. The fact that Mandos ended up as very much like the Celts is proof that the technique of evolving a character or species - find the niche, then work out what fits it - works every time. It creates something very realistic, because that's how real people and real societies develop. </cite> Celtic people were usually not nomadic! And, once again, non of them were predominantly warriors! It's really hard to be a nomadic farmer. I believe the biggest mistake you made, Ms Traviss, is mixing up the Iron Age (and earlier) tribes that did indeed sack Rome and parts of Greece, and that one day would become the people the Romans conquered. And apart from the Picts they really were conquered. <cite> So all I can say about Mandos and Spartans is that the average Mando would probably tell a Spartan to go and put some clothes on, and stop looking like such a big jessie. </cite>

I'd really like to see a Mando – or anyone – wearing full plate without modern or Star Wars technology in Greece. Happy heatstroke. There is a reason they didn't wear a lot (look up the Battle of Hattîn, where crusaders who didn't wear full helmets and wore chainmail* still suffered badly from heat exhaustion). [Nicolle, David (1993), Hattin 1187: Saladin's Greatest Victory] *chainmail apparently can work like a heatsink CONCLUSION You're wrong. And I felt offended by your FAQ answers. QUESTION You're English. You're from England. A group - a nation - that was historically so warlike and so successful that by now we all speak English. A nation that definitely kicked arse against any Celtic nation trying to go against them (until 1921, and they really tried anyway). A nation that had arguably the largest Empire in history. A nation that still is barbaric and warlike enough that a lost football game has people honestly fearing for their lives.

Also, a Germanic group, since you seem to have trouble keeping language-families and cultures apart. If we were to talk about the family, we could add on the current most aggressively attacking nation (USA) plus the former most aggressively attacking nations (the second and third German Reich), also the people who killed off the Roman Empire for good (the Goths and Visigoth), the original berserkers (the Vikings) and claim at the very least the start of BOTH WORLD WARS. Why did you look further?

Some other sources:

Histoire de la vie privée by Georges Duby and Philippe Ariès, the first book (about the antiquity) I read it translated, my French is ... bad to non-existent

The Day of the Barbarians: The Battle That Led to the Fall of the Roman Empire (about the Huns) by Alessandro Barbero

If you speak Dutch or German, you might try

Helmut Birkhan: Kelten. Versuch einer Gesamtdarstellung ihrer Kultur, Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Wien

Janssens, Ugo, De Oude Belgen. Geschiedenis, leefgewoontes, mythe en werkelijkheid van de Keltische stammen. Uitgeverij The House of Books

DISCLAIMER

I’m angry and I wrote this down in one session and thus probably made some mistakes. I’m sorry. Or maybe I’m not sorry. I’m still angry. She can’t know who reads her FAQ and at least two of her answers (on her professional website) were offensive to the reader.

#history#england#scotland#ancient celts#roman empire#mandalorians#sparta#proud warrior race#shitty research#rant#me ranting#fuck this#karen traviss

82 notes

·

View notes

Text

this prof wont let me in stay in his conlanging class cause i dont have a particular prereq (sad) but anyway here are a few resources he shared with the class:

The Language Construction Kit

The World Atlas of Linguistic Structures

Leipzig Glossing Rules

The Language Creation Society

78 notes

·

View notes

Text

2021 reading list

Thank you for tagging me, @quatregats! 🥰

In 2020, I barely met my 70-books Goodreads goal, because I mainly read on my daily commute to uni and due to the pandemic I haven't had to go there since March.

Furthermore, the German uni I’m currently attending is only a 10-minute walk from my house, so no time to read.

Since I’ll only have presence lectures one week a month when I finish my Erasmus stay, I’m not expecting to read a lot this year (besides mandatory readings for my courses), so my Goodreads goal is only 50 books.

In case you’re curious about what I read in 2020, here’s my Goodreads account :)

Der Tote und das Mädchen by Martina Bick (currently reading)

Law and Colonial Cultures: Legal Regimes in World History, 1400-1900 by Lauren Benton (currently reading; for college)

Love and War: How Militarism Shapes Sexuality and Romance by Tom Digby (for college)

Bodies in Resistance: Gender and Sexual Politics in the Age of Neoliberalism by Wendy Harcourt (for college)

Gomorra by Roberto Saviano

Ruin and Rising by Leigh Bardugo

Gebrochene Herzen by Theo Scherling

Les statuettes by Christian Lause

Contemporary Linguistics: An Introduction by William D. O’Grady

David, Dresden by Thomas Silvin

The Language Lover’s Puzzle Book: Lexical Perplexities and Cracking Conundrums from Across the Globe by Alex Bellos

The Penguin Atlas of Women in the World by Joni Seager

Kleines Kuriositätenkabinett der deutschen Sprache by Duden

100 Karten, die deine Sicht auf die Welt verändern by Katapult

Literature française. Les textes essentiels by F. Ploquin

Caliphates and Islamic Global Politics by Timothy Poirson

Julie, Köln by Thomas Silvin

The Shortest History of Germany by James Hawes

Lucas sur la route by Léo Lamarche

Prisioners of Geography: Ten Maps That Tell You Everything You Need to Know About Politics by Tim Marshall

Illuminae by Amie Kaufman

Lara, Frankfurt by Thomas Silvin

Through the Language Glass: Why the World Looks Different in Other Languages by Guy Deutscher

Sino au restaurant by Charles Milou

Gemina by Amie Kaufman

Nora, Zürich by Thomas Silvin

Obsidio by Amie Kaufman

Mythos: The Greek Myths Retold by Stephen Fry

French Inside Out. The Worldwide Development of the French Language in the Past, the Present and the Future by Henriette Walter

Describing Morphosyntax: A Guide for Field Linguists by Thomas E. Payne

Oh, Maria… by Felix & Theo

French Words. Past, Present, and Future by Malcolm H. Offord

The Clash of Civilizations Twenty Years On by Jeremy Paul Barker

Oktoberfest by Felix & Theo

French. A Linguistic Introduction by Zsuzsanna Fagyal

These Broken Stars by Amie Kaufman

Timo darf nicht sterben! by Charlotte Habersack

El mundo no es como crees: Cómo nuestro mundo y nuestra vida están plagados de falsas creencias by El Orden Mundial

Merde! The Real French You Were Never Taught at School by Geneviève

This Night So Dark by Amie Kaufman

Tina, Hamburg by Thomas Silvin

The Tyrant’s Tomb by Rick Riordan

The Tower of Nero by Rick Riordan

The Vocabulary of Modern French. Origins, Structure and Function by Hilary Wise

This Shattered World by Amie Kaufman

Vera, Heidelberg by Thomas Silvin

Brilliant Maps for Curious Minds: 100 New Ways to See the World by Ian Wright

Tune Up Your French. Top 10 Ways to Improve Your Spoken French by Natalie Schorr

Their Fractured Light by Amie Kaufman

Ausgetrickst by Klara & Theo

I tag @languagessi, @lang0weilig, @languagelaziness, @linguisten, @meichenxi, @segledepericles, and anyone else who wants to do it. I'm eager to know what you'll read in 2021 😊

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fuck Canon, or How I Learned To Stop Worrying And Love My Favorite Media Even When The Creators Keep Fucking Up

We all know that stories don’t tell themselves. People tell stories, and they make choices when telling those stories. They emphasize some characters and downplay others. They bring some events to the foreground and put others in the background. They create, change or omit relationships all day long.

In the Doylist-Watsonian dichotomy, there are only two perspectives available: the perspective from within the world of the story, and the perspective from the real world. But what if there’s a third option?

Imagine a third space where the story we’re being presented doesn’t come purely from within the world of the story, nor is it merely the creation of real-world people, but the adaptations or interpretations of a narrator whose identity may or may not be known.

There’s a lot of leeway to define who this narrator could be, such as an anonymous scholar piecing together a history of important events or a storyteller adapting material from an unknown source. The events that play out on page and screen are not the objective reality of the universe they take place in. They’re stories shaped by narrators who have their own reasons for telling the story the way they do.

There is precedent for it.

Every Star Wars film begins with, “A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away...,” calling to mind myths, fairy tales and legends that have been told, retold and adapted for millennia. The story that unfolds is one storyteller’s version of it. The “real” story may be very different from the one we’re familiar with.

Tolkien’s legendarium rests on the idea that Tolkien himself was not its creator, but its interpreter, like a linguist trying to piece together a portrait of a culture long gone. The “truth” about what he writes may be more complex than Tolkien’s writings let on.

Xena: Warrior Princess had the Xena scrolls, the surviving record of Xena’s travels with Gabrielle. But “surviving record” does not mean Everything The Way It Actually Happened. “Surviving record” can also mean The Parts The People With Money Consider Appropriate for General Audiences.

The stories told about the world of Avatar: The Last Airbender are organized into books structured around an element or theme, suggesting that someone from somewhere wrote these stories down. The fact that Katara’s voice introduces each episode of AtLA hints that the show is her personal recollection of events. How much of what she says is “true,” and how much is colored by her biases and blind spots?

This shift in perspective accomplishes 2 things:

It adds complexity and richness to the stories themselves.

It allows audiences to challenge the narrative from within the narrative.

At its best, this leads to a sort of alchemy, where the base elements of the source material (some of which have Unfortunate Implications) are transmuted into something richer, freer and more meaningful beyond what the original creators ever dreamed.

168 notes

·

View notes

Text

One side of my brain: It's actually very common cross-linguistically for a language to lack anything we would call an article. The World Atlas of Language Structures, in its chapters on articles, reports about one-third of its indexed languages as not having any distinct definite or indefinite articles, and many more have article-like functions only on their "one" numeral and/or on their demonstrative, not considered truly distinct articles in their own rights.

Other side of my brain: your NOUNS are NAKED

4 notes

·

View notes