#wicked: no good deed / popular

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

oh I cannot wait to hear Cynthia Erivo sing No Good Deed

#No Good Deed and Popular are my two favorite Wicked songs#the duality of man etc etc#Ari's versions of Popular are amazing I'm so excited for Wicked Part 2#cynthia erivo#wicked movie#wicked#elphaba#no good deed

178 notes

·

View notes

Text

i have not listened to hamilton in like a week why is he STILL HERE

read the tags if you want to see me talk about musicals for a little TOO long

#this is no hate to you mr leslie odom jr#but i have most certainly listened to other musicians/bands more#anyways i'd say the rest is accurate#my bff and i have been doing a musical binge#started with wicked -> ride the cyclone -> shrek -> legally blonde -> falsettos#i cried twice at falsettos btw it's so fucked up (i loved it sm)#i've listened to wicked before but haven't actually *seen* it so that was nice#i've also heard a couple songs from ride the cyclone & falsettos b4 so i already knew they'd be good#and i've seen shrek the musical like 3 times bc i unironically love it#overall opinions: ride the cyclone might have my favorite cast of characters and i think falsettos might be my favorite musical now#fav songs (for funsies):#ride the cyclone: noel's lament / the ballad of jane doe / jawbreaker / space age bachelor man (insane song btw)#wicked: no good deed / popular#shrek: i know it's today / don't let me go / i think i got you beat / this is our story / what's up duloc?#falsettos: this had better come to a stop / i'm breaking down / four jews in a room bitching / a tight-knit family/love is blind#falsettos cont.: everyone hates his parents / falsettoland/about time#legally blonde: blood in the water / positive / ireland / chip on my shoulder / so much better / whipped into shape / take it like a man#legally blonde cont.: bend and snap / there! right there! / legally blonde / legally blonde - remix / find my way/finale#SORRY I OPENED A PANDORA'S BOX WHEN I STARTED TALKING ABOUT MUSICALS#i really should've posted this on my other acc oh well#okay i'm gonna shut up now im so sorry LMAO#falsettos#legally blonde musical#legally blonde the musical#shrek the musical#shrek musical#wicked#wicked musical#ride the cyclone

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

i'm curious what is the fan fave without the heavy hitters of defying gravity and popular, which ofc are excellent and correctly rated

#wicked#music poll#musicals#megamazing#tumblr poll#like i could have included defying and popular#but i find it boring to just see the obvious winners#win yknow like i'm gonna make ppl choose the third face

125 notes

·

View notes

Text

Go Ahead and Dote on Me - Clavis card story

Story's in His POV

nsfw at the end

As usual, can’t guarantee 100% accuracy on this

[Just a note: people are calling Emma “usagi-chan”]

Spring finally arrived in Rhodolite after the egg hunting contest.

People happily took in the warm winds, admired the flowers that began to bloom following winter, and—

Sweets store owner: Oh, it’s the little rabbit. Are you out with Prince Clavis today?

Emma: Yes. I thought I’d keep an eye on him in case something bad happened.

As we walked through the market together, people called out to Emma everywhere.

It seemed like this would be a springtime tradition this year.

Sweets store owner: You got a lot on your hands, little rabbit. Come, let me give you some baked treats.

Emma: Thank you! By the way, I’ve been hearing “little rabbit” a lot…

Sweets store owner: Yeah, everyone’s been using it. Emma, weren’t you the rabbit in the egg hunt the other day? I think it’s popular because it’s cute. Look, that shopkeep over there’s calling out to you.

Flower store owner: Just in time, little rabbit. I’m currently making a bouquet modeled after you.

Emma: Wow, it’s shaped like a rabbit!

Flower store owner: Yeah. Recently, Rhodolite’s been experiencing an unprecedented rabbit bloom. I guess it’s all thanks you you, little rabbit. Thanks.

Emma: You’re…welcome…?

(Indeed a good trend)

Any direction you look, all of the new spring products displayed in the shops were rabbit-themed.

As a rabbit lover, I couldn’t have been more proud.

Emma: Clavis…do you have something to do with this?

After looking around the market, Emma turned toward me in suspicion.

Clavis: Haha, I don’t have the power to manipulate market trends. I suppose everyone’s become aware of the charm of rabbits. This is how Rhodolite should be.

Emma: Is that a good thing to be happy about…?

Clavis: Naturally. It makes me feel good to see how much everyone likes you. Why not do what the people want and wear those rabbit ears again?

Emma: I don’t want to. It’s embarrassing.

Clavis: I want to see it again. Rather, I always want to see it.

Emma: I’ll consider it when it’s just us alone…

(That’s Emma)

(At any rate, rabbit lovers will spread across the continent)

Emma: Ah…I remembered that Leon won the egg hunting contest.

Clavis: That’s right. He was so strong he almost got banned.

Emma: …Anyway, that means the all-powerful cup that grants any wish is currently in Leon’s hands, right? What exactly does Leon plan to do with that cup?

Clavis: Nothing at all. Since I have the cup on hand right now.

Emma: Huh

Clavis: He wasn’t interested in the prize at all. In exchange, I promised to buy him a drink the next time we went out.

(From the start, I was the one who invited Leon and asked him to win)

(If by chance the hunt failed, then the all-powerful cup would’ve been the target)

(Considering the risks, it couldn’t simply be given to the public)

(But we don’t have to worry about that anymore now)

To make up for a rigged contest, all participants were given a discount coupon that could be used in the market and commemorative Easter eggs.

Hopefully that’ll be enough for forgiveness.

Emma: That all-powerful cup…is in your hands…

Clavis: Hm? What’s with that face?

Emma: Because you’re definitely going to use it for something bad.

Clavis: Such as?

Emma: …

Emma’s face turned red.

It sounded like “bad things” involved doing some wicked deeds to Emma.

She was too cute to handle and I hugged her by the waist.

Clavis: Can you tell me?

Emma: No, I’m trusting your ability as a gentleman.

Clavis: I see, I see. I’ll make a wish on the all-powerful cup when we return home.

Emma: Oh, that’s right! I have a wish that I want the all-powerful cup to grant!

Clavis: You want me to use it to grant your wish and not my wicked one?

I tried not to laugh as Emma vigorously nodded her head.

Clavis: I have no choice but to do as my lovely fiancee asks. What do you wish for?

Emma: Um, well… …

Clavis: If you don’t have one, then I—

Emma: Rabbit!

Clavis: …Rabbit?

Emma: Yes. I know you’re a self-proclaimed rabbit lover, but I can’t be the only rabbit. Wearing the rabbit ears was embarrassing. So I want to see you as a rabbit!

Emma shouted at the top of her lungs, like she had forgotten we were out in public.

Man in market: King Clavis as a rabbit?!

Woman in market: …A rabbit? Is that okay? No restrictions?

(I see…Now I have to live up to expectations)

Clavis: Alright. After all, it’s my lovely fiancee’s wish. Even with the all-powerful cup, I have to make it happen.

Emma: …I’m sorry. I got caught up in the moment when I said that—

When Emma tried to backtrack, I kissed Emma on the lips with a smile to stop her from continuing.

Clavis: Look forward to it, Emma.

In order to fulfill my lovely fiancee’s wish, I had to act quickly.

There wasn’t time to wish on the all-powerful cup and preparations had to be made as soon as possible—

Clavis: Now then my lovely fiancee, here comes Mr. Rabbit.

Emma: Are you actually a rabbit though?!

The next morning, I became a bunny boy and slipped into Emma’s room.

Emma, who was already awake and relaxing in bed, dropped her book in shock.

(However…)

(You’re being surprisingly shy)

I even altered the rabbit outfit, adding a tail to match Emma’s.

Originally I wanted to visit at night with the outfit I prepared overnight, but there’s entertainment in not having made it until morning.

Emma: I didn’t think about it when you disappeared after we came back yesterday, but…it suits you better than I thought it would.

Clavis: Right, right? A handsome man will look good in anything.

Emma: You might be better at being a rabbit than I am.

Clavis: I disagree. I could never be as adorable as you.

Emma: You’re pretty adorable now though?

Clavis: Oh?

(Apparently in Emma’s eyes, I’m a cute rabbit)

(That won’t do)

Clavis: I’m a rabbit today. You can hold me, pet me, love me. Anything you want, okay…?

Emma: Really?

Clavis: Yes, I’m a man of my word. What do you want from me? I’m open to any kinks or perversions.

When I got on the bed and crouched like a rabbit, Emma cleared her throat in embarrassment.

Emma: Th-then…

She hesitantly reached out and placed a hand on top of my head.

She patted my hair gently as if handling a rabbit, tickling me.

Emma: Soft and fluffy. Clavis, your hair’s really nice to touch.

Clavis: …

(I wanted to tease you, but I didn’t expect this kind of play)

(It’s fine when I do it, but when on the receiving end, it’s…difficult)

As I quietly accepted her hand, a small chuckle escaped Emma’s lips.

Emma: Are you feeling a little shy?

Clavis: Haha, how could I?

Emma: But you’re not being as talkative as usual.

Clavis: I was just distracted by how nice your hand feels.

Emma: If you say so.

(...)

As she became more accustomed to it, Emma’s hands got bolder.

I’ve never felt so self-conscious.

(I thought I’d be able to take anything Emma did, but…)

(I’m not cut out for this)

Clavis: Emma, you know this rabbit can do dirtier things, right?

Emma: No, please continue being a cute rabbit.

Clavis: Haha, don’t feel like you have to hold back. For instance—

I push Emma down and boldly hike up the skirt of her nightgown.

When I pushed her legs apart and placed myself between them, Emma started to look flustered.

Emma: What are you doing there?!

Clavis: I’m a rabbit. I’ll go anywhere I want.

I pressed my lips against her thigh under the nightgown and continued up.

Emma: Ah…Don’t…

She tried to stop me with a hand, but faltered when my lips reached her underwear.

Clavis: I’m a cute rabbit, aren’t I? I can be more affectionate if you want?

I shifted her underwear to the side and licked.

The sweet sounds she made were like honey and I almost felt like a spring rabbit in heat.

Emma: Cute rabbits…don’t…Nghaa…

Clavis: Is that so? There’s all sorts of rabbits.

I sucked at her wet spot before appearing out from under her nightgown when her hips bucked up.

When Emma scowled at me in embarrassment with tears in her eyes, I wanted to focus on teasing her more.

(No matter what, you’re cuter than I am)

I removed my vest, undid my tie, and placed the rabbit ears I was wearing on Emma’s head.

Clavis: As expected, it suits you better.

Emma: Really…?

Though she was embarrassed, she didn’t remove the rabbit ears.

She fixed the ears and the sight of her being all shy burned all sense of reason away.

Emma: Nn…Clavis, don’t touch…Aahh

Clavis: Emma…stay as my rabbit for the rest of your life.

(After all, I’m a man that would rather be loved)

260 notes

·

View notes

Text

Names in fairytales: Prince Charming

Prince Charming has become the iconic, “canon” name of the stock character of the brave, handsome prince who delivers the princess and marries her at the end of every tale.

But... where does this name comes from? You can’t find it in any of Perrault’s tales, nor in any of the Grimms’, nor in Andersen - in none of the big, famous fairytales of today. Sure, princes are often described as “charming”, as an adjective in those tales, but is it enough to suddenly create a stock name on its own?

No, of course it is not. The name “Prince Charming” has a history, and it comes, as many things in fairy tales, from the French literary fairytales. But not from Perrault, no, Perrault kept his princes unnamed: it comes from madame d’Aulnoy.

You see, madame d’Aulnoy, due to literaly helping create the fairytale genre in French literature, created a trend that would be followed by all after her: unlike Perrault who kept a lot of his characters unnamed, madame d’Aulnoy named almost each and every of her characters. But she didn’t just randomly name them: she named them after significant words. Either they were given actual words and adjectives as name, such as “Duchess Grumpy”, “Princess Shining”, “Princess Graceful”, “Prince Angry”, “King Cute”, “Prince Small-Sun”, etc etc... Either they were given names with a hidden meaning in them (such as “Carabosse”, the name of a wicked fairy which is actually a pun on Greek words, or “Galifron”, the name of a giant which also contains puns of old French verbs). So she started this all habit of having fairytale characters named after specific qualities, flaws or traits - and among her characters you find, in the fairytale “L’oiseau bleu”, “The blue bird”, “King Charming” (Roi Charmant). Not prince, here king, though he still acts as a typical prince charming would act - and “Charming” is indeed his name.

And this character of “King Charming” actually went on to create the name we know today as “Prince Charming”. It should be noted that, while a lot of d’Aulnoy’s fairytales ended up forgotten by popular culture, some of her stories stayed MASSIVELY famous throughout the centuries and reached almost ever-lasting fame in countries other than France: The doe in the woods, The white cat, Cunning Cinders... and the Blue Bird, which stays probably the most famous fairytale of madame d’Aulnoy ever. It even was included in Andrew Lang’s Green Fairy Book.

And speaking of Andrew Lang, he is actually the next step in the history of “Prince Charming”. He translated another fairytale of madame d’Aulnoy prior to Blue Bird. In Lang’s “Blue Fairy Book”, you will find a tale called “The story of pretty Goldilocks”. This is a VERY bad title-translation of madame d’Aulnoy “La Belle aux Cheveux d’Or”, “The Beauty with Golden Hair”. And in it the main hero - who isn’t a prince, merely the faithful servant to a king - is named “Avenant”, which is a now old-fashioned word meaning “a pleasing, gracious, lovely person - someone who charms with their good looks and their grace”. When Andrew Lang translated the name in English, he decided to use “Charming”. At the end of the tale, the hero ends up marrying the Beauty with Golden Hair, who is a queen, so he also becomes “King Charming” - but the fact Avenant is a courtly hero who does several great deeds and monster-slaying for the Beauty with Golden Hair, a single beautiful queen, all for wedding reasons, ended up having him be assimilated with a “prince” in people’s mind.

And all in all, this “doubling” of a fairytale tale hero named “Charming” in Andrew Lang’s fairytales led to the colloquial term “Prince Charming” slowly appearing...

Though what is quite funny is the difference between the English language and the French one. Because in the English language, “Prince Charming” is bound to be a proper, first name - due to the position of the words. It isn’t “a charming prince”, but “prince Charming” - and again, it is an heritage of madame d’Aulnoy’s habit of naming her characters after adjectives. But in French, “Prince Charming” and “a charming prince” are basically one and the same, since adjectives are placed after the names, and not the reverse. So sometimes we write “Prince Charmant” as a name, but other times we just write “prince charmant”, as “charming prince” - and this allows for a wordplay on the double meaning of the stock name.

#fairy tales#fairytales#prince charming#fairytale archetype#french fairytales#madame d'aulnoy#d'aulnoy fairytales#andrew lang#lang fairy books#names in fairytales

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

WICKED MOVIE SPOILERS

During Popular, Galinda tells Elphaba “pink goes good with green” in which Elphaba responds “pink goes well with green”.

This, to me as a first time Wicked viewer, always had a double meaning, that on one hand, Elphaba is a grammar police but also, that this kind of alludes to the way Elphaba rejects the notion of goodness by the end of the movie.

Throughout the movie, Galinda is constantly defined as “good” but deep down all of her good deeds are shallow (ex. Changing her name to take a stand when she states she doesn’t really care about Dr Dillamond).

Her goodness is performative and done to appease her peers and make her look better. As Elphaba said, “You couldn’t care less about what people think. Through I doubt that’s true.”

Elphaba’s kindness however, has her perceived as an enemy of the people and wicked, but she in the end, doesn’t care. She’d rather be considered wicked and do what she considers morally right rather than be seen as “good” and perform shallow acts of kindness for the approval of the people.

#rambles#wicked#wicked movie#wicked musical#galinda upland#wicked galinda#galinda x elphaba#galinda the good witch#ariana grande galinda#dear galinda you are just too good#glinda upland#glinda the good witch#wicked glinda#ariana grande glinda#Glinda#galinda#defying gravity#what is this feeling#popular wicked

56 notes

·

View notes

Note

you should assign your moots wicked songs, too

I fear I have HUNDREDS of moots, anon.

However! I am happy to assign each wicked song one of my mutuals. I love every single one of these songs so NONE of these are reasons for offense (yes I know how some people feel about sentimental man. No my brain does not permit such thoughts about a wicked song)

If you’re wondering the reasons, just ask ;)

No one mourns the wicked - @doodle-do-wop

Dear old shiz - @lilliesandlight

The wizard and I - @wow-youre-so-pretty

What is this feeling - @choasuqeen

Something bad - @winterfireice

Dancing through life - @ahoyimlosingmymind

Popular - @the-oracle-at-delphinitely-not

I’m not that girl - @kale-of-the-forbidden-cities

One short day - @swans-chirping-in-the-distance

Sentimental man - @nobodysdaydreams

Defying Gravity - @permanently-stressed

Thank goodness - @gay-witches-are-the-best

Wicked witch of the east - @phtalogreenpoison

Wonderful - @jkriordanverse

I’m not that girl (reprise): @thatrandomlemononyourcounter1

As long as you’re mine - @queefsencen

No good deed - @fintan-pyren

March of the witch hunters - @shouldwemaybe

For good - @sophieswundergarten

Finale - @f1gure-skater

If anyone tagged wants to know WHY you got the song you got (the answer might be vibes lmao) do tell me bc i selected you each for every song with much love in my heart.

If any mutuals NOT tagged in this post want to be assigned a wicked song, just let me know and I’ll give you one! I did consider quite a few people of each song (I considered @permanently-stressed for like… five… but in my defense she’s my cognate and I think about her a lot)!!

60 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Gang As Songs From Wicked

Note that this will include songs from the entire musical, not just the movie.

Ponyboy: The Wizard and I. I feel like the longing to do good and accomplish something with your life, especially if it’s something that you didn’t originally think you’d be able to in life is something that Ponyboy heavily relates to. And for him his version of ‘degreenify’-ing him is people no longer seeing him as just a greaser.

Soda: Dancing Through Life. Obvious things like not being good at school and him saying that he’s dumb (otherwise known as brainless) are things that Soda can clearly relate to. But also the general idea of the song of how life is easier if you just choose not to think about it too much and at the end of the day nothing matters to it. Nihilism with a funky beat is Soda’s whole vibe.

Darry: I’m Not That Girl. This might sound like a weird one but hear me out. While the song may be about romance for Darry it’s just life. “I wasn’t born for the rose and pearl,” is the story of his life. He spent his childhood/teenage years surrounded by people who were destined to do great things while he had to stay in Tulsa and couldn’t accomplish the things he wanted to.

Johnny: No One Mourns The Wicked. I feel like after Johnny killed Bob Tulsa had a rather large hate campaign against him. They only saw him as a no good hood and only those who were close to him knew differently. And of course, the tragic childhood featured in the song. Glinda in this song is essentially the gang trying to save his reputation.

Dally: No Good Deed. Just how Elphaba decides to embrace being wicked, Dally embraces being a hood. The desperation Elphaba feels over keeping Fiyero alive is similar to what Dally felt when Johnny was dying (only he couldn’t save Johnny). Also turning away from the concept of ‘good’ is really similar to Dally’s need to be tough

Steve: As Long As You’re Mine. Him and Evie have the healthiest relationship and with how he semi-frequently gets locked up (not to the same extent as Dally, but it still happens) I’m sure that they can sometimes relate to the desperation of the song.

Two-Bit: Popular. Less so about the lyrics of the song (although I’m sure “it’s not about aptitude, it’s the way you’re viewed” sums up his perspective in life) but more about the general comedy of the song. If you look at up pretty much any version of this song you will see many Glinda’s doing so many ridiculous things seemingly trying to get a laugh out of their Elphaba. Which basically is just how he acts around basically anyone. Just in more of a Greaser way.

#I’m a little late to this#but the grip hold wicked has had on me lately is insane#the outsiders#ponyboy curtis#the outsiders musical#darry curtis#ponyboy michael curtis#curtis gang#johnny cade#sodapop curtis#dallas winston#two bit the outsiders#two bit mathews#steve randle

36 notes

·

View notes

Note

do you have any favourite headcanons for elphaba and glinda? if not, then what is your favourite song on wicked?

oooooh lemme think on this

i like to think the glinda was a rambunctious child and has the scars to prove it. she'd trip and get scraped, she'd fall out of trees, every manner of childhood playtime injury you could think of, she sustained. as she grew up, image became more and more important. she stopped such rowdy behavior. but the scars are still there. Elphaba is one of the very few people that knows they even exist

idk why this feels specifically bookverse to me but i think bookverse elphie has a huge sweet tooth. like. pretends to be all cold and distant but her biggest weakness (besides glinda) is a bowl of chocolates in front of her

favorite song? now that's just an impossible question. I can give you my top three from each act though

Act 1:

no one mourns the wicked

defying gravity

popular

Act 2:

thank goodness

for good

no good deed

thank you for the ask!! :)

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

this is so silly and out of character but im wicked and re-animator fixated rn so hear me out! (this would be maybe 2005 bc thats when the tour began. also danbert is already dating)

what if au where herbert is a very very closeted musical theater kid (idk i just think he would be)

and i think dan listens to whatever's popular so he listens to the wicked cast album and was surprised to really like it! then he hears that they're performing at a local theater or something so he drags herbert with him and herbert ofc bitches the whole way there about how this will be a "trite stage production" but then he stays silent for the show bc he's not an asshole daniel he knows proper theater etiquette.

intermission comes after defying gravity and herbert is actually very moved but won't admit that to dan when he asks how herbert is liking the show.

act 2 begins and herbert starts to see himself in the character of elphaba, always the odd one out, outcasted for being different, going against whats normal/good... i imagine he claps out of respect at the end of each song but after no good deed he claps very loudly and very fast bc hes excited! and dan smiles a little at him and then herbert plays it off as "just showing proper theater etiquette"

and then for good happens and herbert actually cries. not a lot but he does, dan notices and reaches over to squeeze his hand just as glinda and elphaba hug for the last time on stage, herbert locks eyes with dan and then turns his attention back to the show.

after the finale and the cast comes out for bows herbert gives a standing ovation for glinda and elphaba and woops a little (dan looks at him fondly and herbert doesn't make eye contact/denies he did this later)

and then when the show officially ends dan asks herbert if he liked it and that he hopes he's not mad at him for being dragged to a "trite stage production" and then herbert surprises dan by taking his hand and sheepishly admitting that it wasnt trite and that he loves him.

dan beams the whole drive home and herbert doesn't let him let go of his hand :-)

#combining hyperfixations is so fun hmwhy have i not done this before...#reanimator#herbert west#dan cain#danbert#re-animator#re animator#and now its time for wicked nation to be very confused as to why they r tagged lol#wicked#wicked musical#wicked the musical#elphaba thropp#galinda upland#glinda upland#wicked witch of the west#glinda the good witch#gelphie#(they parallel danbert here)#heliojabs#heliodrafts#<- new writing tag sure#yeah this one is very self indulgent lol#write what u want to see or whateverrrr

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

there's a bunch of parallels to be made between wicked and mo dao zu shi, as many people have already pointed out (see: these reddit posts, these animatics). but i was thinking about how wangxian's roles in comparison to elphaba and glinda can be considered to reverse over time. i mostly see people comparing wwx to elphaba and lwj to glinda, and sure, there's a lot of comparisons to be made there, but try to consider another angle.

in the cloud recesses, when they're teenagers, lan wangji is a disciplined, hardworking, intelligent student with a lot of pressure put on him to honor his family and their reputation, beloved by his teachers but witout any friends around his age, except perhaps for his brother; much like elphaba. meanwhile, wei wuxian isn't exactly the most dedicated disciple, and breaks quite a few rules without caring about it, which doesn't exactly make his teachers love him, but at the same time, he's popular and loved by his colleagues (who mostly dislike lan wangji, either finding him a sort of teacher's pet or being afraid of him); in that sense, he's more like galinda (if we're looking through a queer galinda lens, we can also say both characters are very entrenched in comphet and very oblivious to their same-sex attraction, with galinda supposedly being a boy-crazy, girly girl and wei ying being very flirtatious towards women, and claiming to have been with many of them without even considering the most remote possibility that he could like men too).

but then, let's skip to both pairings in their adulthood. wei wuxian, that formerly popular, charming individual, is now the yiling patriarch, a previously very talented, advanced young man who's considered different from others in his society because of his methods, something that used to make people admire him and then became his downfall; he started to be hunted and blamed for all evil that ever happened, becoming the biggest public enemy in the cultivation world, and a legend of sorts, nearly a mythical figure, the represention of evil itself. at the same time, despite being warned by those who loved him, he didn't back down in doing what he thought was right (also defending a vulnerable and marginalized group that was being ostracized and blamed for doing evil things - the remaining wens - like the animals were), officially cutting all ties with the respected, traditional cultivation circles and running away to the burial mounds, very aware that this would make him be hated and turned into a villain. eventually, after losing people he loved, he started actually leaning into this evil version of him that was publicly known, comitting so called "evil" deeds while stricken by pain, and soon after, he died on hiw own, while the entire world celebrated his death and talked about how he deserved it because of how he'd done certain things, a lof of them not being true (note: both pieces of media begin this way, with the viewers/readers being introduced to the story with celebrations of the main character's death - and in both cases, said character wasn't actually - or permanently - dead). i don't even have to say how extremely similar to elphaba's story his story is in that sense (and you could still find more similarities, like both characters being morally gray or both characters being very attached to their siblings and going at extreme lenghts to protect them; i could go on). now let's look at lan wangji, who used to be that stubborn student disliked by many of his peers. in the current time, he has become hanguang-jun, a strong authority figure, respected by everyone in the cultivation world and widely considered an example of righteousness and Good. always very put together, always elegant, always where the chaos is; he's often resolving conflicts and is looked upon and admired as someone trustworthy and strongly virtuous. he was offered the chance to join wei wuxian in what he was doing at the burial mounds, years ago, but he declined, which led to him only being capable of helplessly watching from afar as the person who mattered the most to him grew to be more and more misunderstood by society at large, and consequentially, more and more hated - and persecuted. he was then forced to watch as the entire world celebrated the death of said person, never learning the truth about what had actually happened and who he actually was. does this remind you of anyone?

so basically, what i mean is that teen wei wuxian, a popular, likeable, enjoyer-of-life (or perhaps dancer-through-life) galinda, became a brilliant, but villanaized, ostracized and misunderstood wicked witch, like elphaba; while young lan wangji, a disciplined, introverted, hard-working elphaba, grew to be a respected and admired authority figure who was actually in deep suffering because of the way he lost the person he loved - not unlike our gal glinda, the good.

#does this make any sense.#i know there's a lot i left out but this thought was stuck in my head so i had to come write it out#i was actually listening to what is this feeling while imagining cloud recesses arc wangxian#then i stopped and thought. wait a minute... a lot of these lines work for both of them? like. “the dear galinda you are just too good” par#in the animatic i linked it's the lan clan members and other disciples talking to lwj#but i can sort of imagine it being said towards wwx by nhs and the others#also. the beginning part (“dearest darlingest momsie and popsicle...” “my dear father”)#or “unusually and exceedingly peculiar and altogether quite impossible to describe” vs “blonde” (single-word irritated response)#matched with wwx as galinda and lwj as elphaba very well#“what is this feeling so sudden and new?” “i felt the moment i laid eyes on you” matched better with wwx and lwj respectively imo#but then “your face” “your voice” “your clothing” just made more sense with lwj then wwx then lwj???#anyway. you see where i'm trying to get.#a few excited audio messages to a friend and a lot of thoughts later. the result was this#hope you enjoy it#my posts#long post#mdzs#mo dao zu shi#grandmaster of demonic cultivation#mxtx#wei wuxian#wei ying#yiling laozu#lan wangji#lan zhan#hanguang jun#wangxian#wicked#wicked musical#elphaba

28 notes

·

View notes

Note

i wanna see you assign all of your moots a song from wicked 👀

OMG ok ok!! So im gonna do a mixture of both movie/musical

@ozymandian-circus is dancing through life

@elwoodsharmonica is the Wizard and i

@batesmotelofficial is defying gravity

@gigireece16 is what is this feeling

@foxherder is popular

@my-mom-named-me-duck is no good deed

@maria-the-puppet is thank goodness

@capn-atlas is no one mourns the wicked

@daenerys713 is not that girl

@myfairkatiecat is for good.

19 notes

·

View notes

Note

Character ask: Fiyero and Boq (Wicked)

I'm not really a die-hard Wicked fan, but here goes. This is for the musical only, since I haven't read the novel.

Warning: spoilers below.

Fiyero

Favorite thing about them: That despite seeming like a silly playboy at first, he proves to be a kindred sprit to Elphaba, who loves and respects her as she is, who tries to help and defend her when no one else in Oz is willing to do so, and who ultimately sacrifices everything for her, even (nearly) his life.

Least favorite thing about them: That he leads Glinda on by not breaking up with her even as he starts to fall for Elphaba, and then goes along with their engagement even though he doesn't want to marry her. He should have ended things between them long before it reached that point.

Three things I have in common with them:

*I can be snarky.

*I dislike fakeness and selling out.

*I can seem like just a fun-lover, but really I think and feel deeply.

Three things I don't have in common with them:

*I'm female.

*I'm not royalty.

*I was never a partying troublemaker in college.

Favorite line: His joke when Elphaba tells him she realizes he's not as shallow and self-absorbed as he seems:

"Excuse me, there's no pretense here: I happen to be genuinely self-absorbed and deeply shallow."

And these lines from his dialogue with Glinda at the beginning of Act II, where he calls her out on her tragic flaw of choosing fame and popularity over everything else:

"You can't leave because you can't resist this. And that is the truth."

And when she objects that no one could resist it: "You know who could. Who has."

brOTP: His horse Feldspur in the movie, and probably Boq, especially if we keep the Scarecrow and Tin Man's friendship in mind. Not to mention Dorothy, even though their interactions are kept offstage.

OTP: Elphaba.

nOTP: Glinda.

Random headcanon: Hmmm... In the movie, he really did eat grass as a child. He's not just joking when he says he did.

Unpopular opinion: I like him better than Glinda as a romantic partner for Elphaba. Of course I understand that Elphaba and Glinda's bond is more central and more fleshed out, I see the appeal of Gelphie as a ship, and I know how much Gelphie means to countless fans. But personally? Without denying Glinda's importance to Elphaba, I prefer Fiyero as her love interest. He embraces her values and comes through for her in a way that Glinda only does at the very end, and no attempts I've read by Gelphie shippers to dismiss that fact ring true for me. As a couple, Fiyeraba reminds me in many ways of Esmeralda and Phoebus in Disney's Hunchback of Notre Dame (these Stephen Schwartz musicals have recurring themes!), and I don't see many fans putting down that pairing, even though they're a bit underdeveloped too, and even though Esmeralda's friendship with Quasimodo is more central to the plot. On the contrary, the fans hold up their love as the main example of healthy love in that story! Besides, if we don't think Elphaba really loves Fiyero, then "No Good Deed" loses its power. If he's just "comphet" to her, why should his apparent death break her so much that she resolves to really be wicked and kidnaps Dorothy? And the reveal that he's still alive is what snaps her out of her breakdown and lets her reconcile with Glinda in the end. I have nothing against shipping Gelphie, but I can't dismiss Fiyeraba as just "boring comphet" the way most of the fandom seems to do.

Song I associate with them: "Dancing Through Life"

youtube

"As Long as You're Mine"

youtube

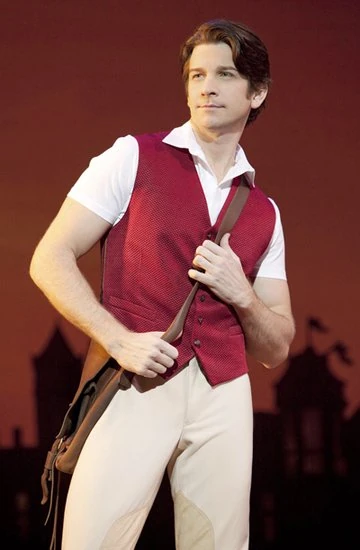

Favorite picture of them:

Norbert Leo Butz

Aaron Tveit

Andy Karl

Derrick Williams with Stephanie J. Block (more actors of color should play the role)

Adam Garcia with Idina Menzel

Jonathan Bailey in the movie

Boq

Favorite thing about them: Well, when we first meet him at least, he's a sweet, adorkable character, and if the Tin Man we know from The Wizard of Oz is a mostly accurate portrait of how he behaves on his journey with Dorothy, he never really loses those qualities.

Least favorite thing about them: First that he leads Nessarose on (a recurring flaw among the young men in this story, it seems) and lies about why he asked her out, even if his reason is to avoid hurting her. And later, of course, that he becomes such a bloodthirsty witch hunter, out to kill Elphaba for turning him into tin even though she saved his life by doing so.

Three things I have in common with them:

*I can be socially awkward.

*I'm not always good at standing up for myself.

*Sometimes I want to blame people for doing things that made me uncomfortable, when really those things were good for me.

Three things I don't have in common with them:

*I'm female.

*I've never had any romantic entanglements with witches.

*I've never been turned into tin.

Favorite line: His verse in "March of the Witch Hunters," even though it's his darkest moment:

And this is more than just a service to the Wizard I have a personal score to settle with El... With The Witch!

It's due to her I'm made of tin Her spell made this occur So for once, I'm glad I'm heartless I'll be heartless killing her!

And the Lion also has a grievance to repay If she'd let him fight his own battles When he was young He wouldn't be a coward, today!

brOTP: In the Shiz days before things go bad, Fiyero, Nessarose, Elphaba and Glinda (especially in the deleted scene from the movie that shows them all hanging out together). And after he becomes the Tin Man, Dorothy.

OTP: None.

nOTP: Nessarose or Glinda.

Random headcanon: When he sees Elphaba "melt," he'll be unexpectedly horrified; he'll find himself remembering their days at Shiz and the girl she once was, and realize that seeing her die horribly doesn't feel as good as he thought it would. (I'm basing this on the Tin Man's close-to-tears face after the Witch melts in the 1939 Wizard of Oz: we'll see if Wicked: For Good has Ethan Slater react in a similar way or not.)

Unpopular opinion: Even though he's far from blameless, nothing justifies Nessarose stripping him and all the other Munchkins of their rights and forcing him to stay with her, then trying to magically brainwash him into loving her. He may deserve some karma for lying about his feelings for her, but he doesn't deserve all that.

Song I associate with them:

His part in "Dancing Through Life"

youtube

"March of the Witch Hunters"

youtube

Favorite picture of them:

Christopher Fitzgerald

Riley Costello

Ethan Slater in the movie

#wicked#musical#character ask#fiyero#boq#ask game#fictional characters#fictional character ask#spoilers

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

i've watched way too many wicked bootlegs in the past few weeks and so. reviews of the elphabas i've watched so far (in alphabetical order by last name, this is NOT a ranking).

stephanie j block

she's good! not my favorite i've seen, but i did enjoy her performance overall. i liked her scenes at shiz with doctor dillamond a lot. i really liked how she made the role her own; not sure if it's her singing voice or general speaking intonation or some combination of it all but something felt very distinct from the other elphabas i've watched. no good deed was CRAZY. also her chemistry with sebastian arcelus (fiyero) is solid--i looooooved as long as you're mine. given that they're married this makes sense lmfao, but still thought i'd mention it. fiyero's little spellcasting hand motions and elphaba scoffing and rolling her eyes is actually adorable. another side note but i will also say that annaleigh ashford as glinda was WAY better than i expected and i'm a little obsessed with her.

lilli cooper

ok im gonna be a little harsh here, i'm sorry but i didn't love this cast as a whole (kara lindsay as glinda, jerad bortz as fiyero). cooper had some really good acting moments (particularly in popular and in for good) and i liked her chemistry with glinda (more about lindsay later though) but i just don't think she sang the part quite as well as anyone else in this post. i liked cooper in spring awakening, and looking at her other roles, i'm sure she kills it in those! she just wasn't elphaba for me.

jennifer dinoia

VERY good!!! loved her chemistry with kara lindsay (glinda). unfortunately everything abt kara lindsay is so deeply newsies to me and this was very distracting the entire time. which is not either of their faults so not a fair point of judgment. anyways. overall i really liked how they played off each other. dinoia is super underrated imo. i will say i think her defying gravity isn't the best out there, but i really love her acting overall and the wizard and i was great. she was also so cute in dancing through life so points for that. she does hopeful really well, which is really neat to see in an elphaba. also i found my old playbills later and shes one of the elphabas i saw live! so that's neat.

eden espinosa

quite enjoyed her!!! really strong belt. also quite enjoyed this glinda (megan hilty), but that's a different post. also this fiyero (derrick williams) slaps. damn this cast is just really good together. anyways back to espinosa. her acting is so good i love her. the toss toss with fiyero was fucking adorable and then the immediate switch to outrage over dr dillamond was crazy. she and hilty also have a really good dynamic i love it. alaym was also solid ("you can see houses flying through the sky but not that?" n her little laugh? man. i love elphaba). i think espinosa's biggest strength is her acting--she's a crazy good singer, too, don't get me wrong, but her acting all throughout is absolutely stellar.

mandy gonzalez

VERY much enjoyed her!!!! absolutely incredible as long as you're mine with andy karl--i think they might have my favorite rendition of that song so far. fabulous no good deed as well. i liked how she fell into the last pose at the end of that song. definitely a favorite version of i'm not that girl. took a minute for me to warm up to her acting wise, honestly, but i was very much convinced by the end.

idina menzel

watched her and kristin chenoweth and norbert leo butz and joel grey's last show together, which was a mistake because i am in hysterics. oh my god. so side note but while obviously there are many actresses who have done the role, kristin chenoweth is THE GLINDA. like she's THE glinda. there are other glindas, and there are good glindas, but kc is THE glinda. anyways. okay. sobbing. okay. so idina menzel is , like, the gold standard for elphabas obviously. she's the original broadway elphaba, the defying gravity notes are hers, she's one of the best to ever step on the gershwin wicked stage. i loooooved her passion, and i actually liked how it wasn't always plagued with defensiveness or anger. her no good deed SLAYS though. she did break a few times but i'm giving her a free pass because it was the last obc cast performance and everyone on that stage and in the room was falling apart emotionally. anyways. she's the gold standard, she really is. no words will do her justice. god. im normal about wicked.

dee roscioli

she was good! idk not super notable/memorable to me? i really did like her overall!! she's very skilled and i can appreciate that for sure. just not the best imo. dynamic with clifton hall (fiyero) was really good though, so win for both of them for that.

willemijn verkaik

FAVE FAVE FAVE. i loooooveeed her. so good. absolutely one of the best i've seen so far. her singing is absolutely showstopping. after defying gravity i had to pause and scream alone in my kitchen for a bit. her no good deed is also incredible. she also is so clearly theatre through and through--her balance of strong acting and INSANE singing was really well done. outstanding as long as you're mine, too (kyle dean massey as fiyero was also really good in that; and later the "i wish i could be beautiful for you" and "touch, i don't mind" moments made me feel insane about them). her chemistry with katie rose clarke (glinda) was also quality. fr had me thinking maybe this time glinda would go with her. maybe this time it would work out. oh and her scenes with nessa were also outstanding. for good literally sent me into hysterical sobbing so points for that. god. overall she 10000% was part of the re-igniting of my brainrot over wicked. she's so good. man. god. ok. im normal.

donna vivino

first off, did NOT know she was the original young cosette, so that's irrelevant but super cool! anyways, REALLYYYYY loved her. great dynamic with fiyero (not sure of the actor in this one), and the way she played off glinda in for good specifically was *chef's kiss*. no good deed had me absolutely SOLD on her. i think she has the best rendition of that one that i've seen. moments that remind me that i fucking love THEATRE!!!!! overall she has an incredible voice, and her acting was good as well! had me shaking and trembling during elphaba's biggest scenes (no good deed and for good in particular). i also really liked that she clearly wasn't just trying to be a carbon copy of idina menzel (as some replacements definitely do with the original actor in all roles in any show)--she instead definitely made the role her own, and i really appreciated the choices she made both vocally and acting wise.

jessica vosk

oh she had me wrapped around her finger from line ONE. her voice is absolutely gorgeous, and her acting is spot on. she has so many little gestures that i loved, little small smiles or scoffs or whatever that just felt so fitting. she embodied the character so well. her no good deed made me want to stand up and scream even though i am so cozy in bed. chemistry with glinda (allison bailey) was really solid; popular was really fun. also just generally speaking and as huge side note, her story of how she rose to broadway success makes me feel a little crazy. anyways. maybe i'll try to see her in hell's kitchen. i LOVE her voice.

#been working on it for a while but i reached 10 on this list so i figured i would post this finally lol#im sooooooo normal about wicked#wicked#wicked musical#wicked broadway

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

With the news of cancellation of Good Omens S3 into a 90 minute finale I sort of find myslef reminicing about where does the border between seperating art from the artist lie.

As a preface I'm gonna say I don't have any particular attachment to Gaiman's body of work as a whole. Western comics were never really popular where I'm from outside of extremely niche circles that graduated into standard niche circles only recently, with Gaiman's visual and literary works included. So this opinion does not stem from any particular nostalgic place. As far as I'm aware the situation is currently still under investigation, but there is concrete proof that Gaimain is, by the traditional definition, no longer considered a "good person" or at least not aligning with his previous public persona. I'm not really an authority to speak on the topics involved in the scandal and I'm really here just to ramble on my own personal blog about art and artist relationship, I'll leave the rest to people who know what they are talking about. Good? Good.

I know it's easy for to denounce, degrade or disprove work made by people we find out were some sort of morally corrupt or did awful stuff in their life. This usually stems from the fact it's hard to believe someboy who's in empathetic and introspective enough to write about topics that resonate with many people so well would still choose to hurt vulnerable people around them or to generally engage in activities that mean to do harm to others.

If we take JK Rowling for example, as heartbreaking as it must have been for most fans of her works to find out about her hate campaigns and such, if we look objectively at the body of work in question it was already brought many times it was a bit problematic. Class issues, race issues, character development and morality weren't really well handeled topics in her books and the whole pedestal was really based more on the whimsy of it or mythos that people enjoyed getting immersed into. Even that was put into question with many plagarism allegations, as such, while flabbergasting from a fan's perspective, from outsider's perspective it wasn't really that thought provoking. "Bad person's books turn out to be pretty bad after all" type of situation that's pretty common among people, especially with writing that's generally consider to be "cool", but ultimetly hollow when it comes to emotional stakes.

Another thing is actors that did bad or immoral things. Generally unless an actor doubles as a writer for stuff they star in, it's not hard to imagine that they are actually wicked people behind the curtain. It was a "funny movie trivia" for years that some actors who played the sweetest most innocent characters on screen were awful when the cameras stopped rolling so it's not that hard to detach yourself from their work. Especially when you consider that it's technically not their work to begin with, just because Bratt Pitt plays an important character in Fight Club, does not mean the whole movie should be shunned, because that's just punishing other actors, director, screenwriters even the OG book's author for sins of one person who's personal life was irrelevant to the work in question.

Gaiman is a special case to me, because despite his actions, his work has been universally regarded as very emotional, empathetic and generally very introspective. I was not an avid fan but I did see merit in his work and ideas he helped create. To write stuff like that you need to be in some way selfaware of your own morality and emotions while also being an empathetic enough to be able to imagine how your characters feel. He touched upon a lot of topics, including stuff he's accused of, while also getting praised on how he handled them.

We want to seperate art from the artist and claim it's impossible only when that art relates directly to the artist's immoral deeds (like in Jeepers Creepers), but to me it's just that we don't want to consider the fact that somebody can be so introspective and emapthetic and STILL use their position to hurt people. To write about the emotional damage caused by cruelty and malice of others and then do the same is incomprensible to us and it either speaks really badly about the person or about our understanding of what it means for somebody to be a "bad person".

#meposting#good omens#neil gaiman#as I said if you want some type of wise conclusion its just my ramblings help me purge it out of my mindspace#so don't expect one#also again no discourse about credibility of Gaiman accusations cause its not about that

20 notes

·

View notes