#warsaw ghetto

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

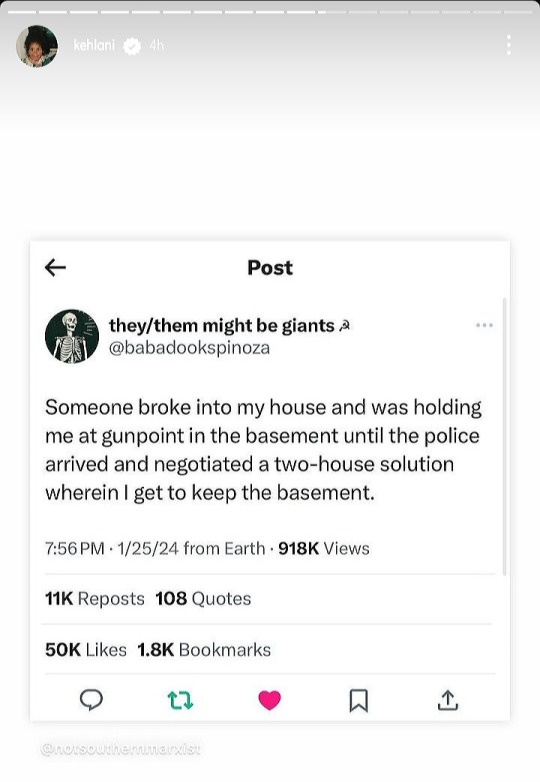

Like fucking hell it was.

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

please watch the WHOLE vid!!

What a Jewish Uprising against Germans teaches us about Palestine.

instagram

more about/for Palestine in this post:

.https://www.instagram.com/p/DHNhDv_MDR3/

(+IMPORTANT) (Nov,2023)-A Bit Fruity Podcast (created by Matt Bernstein (gay American Jewish man) Ep with Moe Dabbagh, a gay Palestinian American with family currently in Gaza. ‘Queers for Palestine & The Power of Pinkwashing’. Palestine has been occupied for more than 76 years now, since 1948 year. This ep gives you a LOT of information, especially if you are one of the people who can’t see right through the propaganda; or the ones who go ‘well if you’re gay then go to Gaza and see how that goes for you’. Queer Liberation is a liberation of Palestinian people. We can’t have one without the other. Free Palestine. Free all the people that are not yet free. This is where we start!! Ep on youtube :https://youtu.be/Xsgdk-DDSXc on spotify :https://open.spotify.com/episode/62WOjKJYih6lhuisP8tmZH?si=soRArGs1QeWqEzEaiSVlUg on iheartcom:https://www.iheart.com/podcast/269-a-bit-fruity-with-matt-ber-117844074/episode/queer-palestinians-the-power-of-129612460/(keep learning & keep showing up!)

!!.http://alqaws.org/siteEn/index & https://queersinpalestine.noblogs.org/ + https://www.instagram.com/queersinpalestine/

instagram

instagram

instagram

instagram

instagram

instagram

instagram

instagram

a really great organization that i don't see any posts about here is HEAL palestine :https://yourartmatters-itswhatgotmehere.tumblr.com/post/769377788956409856 :https://www.healpalestine.org/ +https://ramikashou.com/collections/limited-edition-merch-collection

---I do think with news of the ceasefire, everyone should read up on what the ceasefire actually means and what the different phases of the ceasefire are. here's a good source for what we know as of now:https://www.tumblr.com/evies20dollars/773008798928502784?source=share &What do we know about the Israel-Hamas ceasefire deal in Gaza? | Israel-Palestine conflict News | Al Jazeera

So Trump sat next to Netanyahu..+The problem is not “Israel” or America—it’s white colonization:https://www.instagram.com/p/DFsPQFVMnPb/ &https://www.instagram.com/p/DFrvWJXupvB/

THIS song is so real ALWAYS yes:https://www.instagram.com/p/DFT9kKpvctY/

Little girl from Gaza reading a poem about Resilience:https://www.instagram.com/p/DFrjlKaONmK/

A Letter to Trump from a Child in Gaza:https://www.instagram.com/p/DFpshgHMnP_/ +https://www.instagram.com/p/DFx0WSzN2MS/

more info about Palestine if you want to educate yourself or others:(ig highlight):https://www.instagram.com/stories/highlights/18391980472045227/

#palestinians#save palestine#palestine#free palestine#free gaza#gaza genocide#palestinian genocide#genocide#ethnic cleansing#gaza strip#save gaza#gazaunderattack#gaza#israel#ceasefire#warsaw ghetto#warsaw ghetto uprising#jewish uprising#Instagram#gaza news#news on gaza#gazaunderfire#west bank#all eyes on palestine#palestinian resilience#stand with gaza#help gaza#boycott for palestine#free palestine in our lifetime#free palestine 🇵🇸

95 notes

·

View notes

Text

#black community#original photographers#black people#graphic design#black art#artwork#black power#black family#black history#black culture#ghetto & ratchet#ghetto fabulous#ghettotech#warsaw ghetto#boyhood#black man#black tumblr#hiphopartist#hip hop#hip hop art#african art

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nitzer Ebb

Warsaw Ghetto (1985)

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

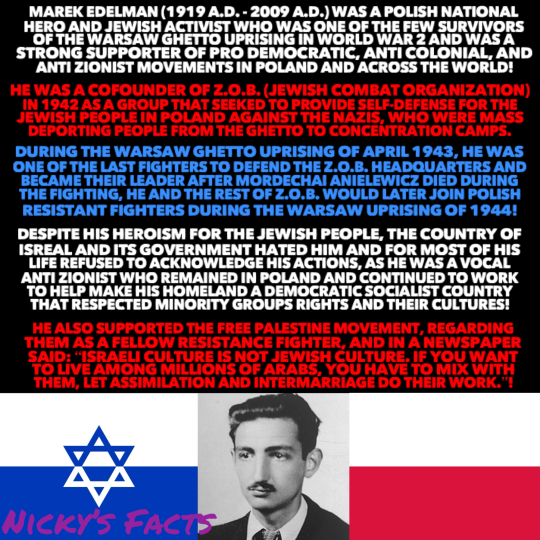

Israel doesn’t represent the Jewish people, nor is it antisemitism to criticize israel or be anti zionist!

🇵🇱✡️🇵🇱

#history#marek edelman#warsaw#poland#anti zionisim#jewish history#hero#resistance fighters#isreal#historical figures#world war 2 history#activist#zob#warsaw ghetto#free palestine#free gaza#polish history#holocoust#jewish culture#warsaw uprising#palestine#ww2#warsaw ghetto uprising#role model#world war 2#nickys facts

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

We Care For Each Other

Artist / Designer / Photographer

Haruka Aoki

Year: 2023

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

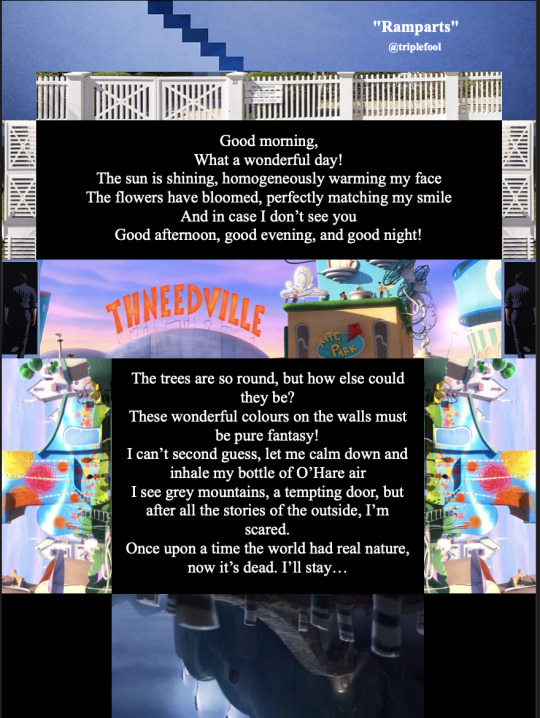

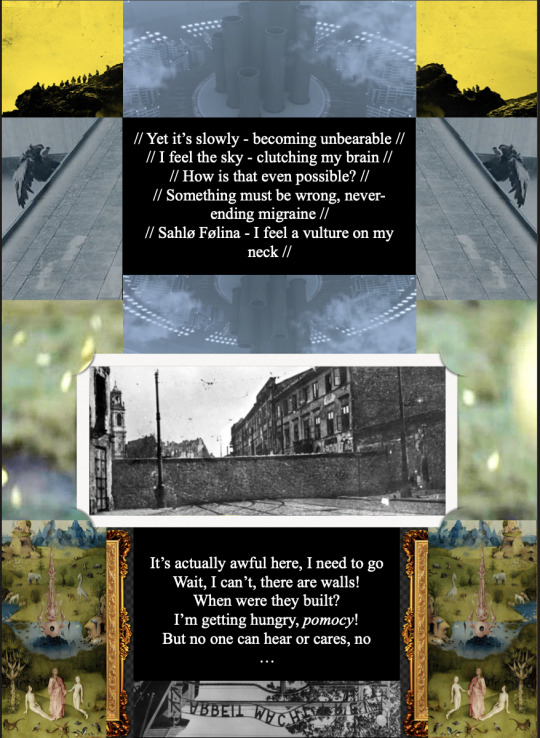

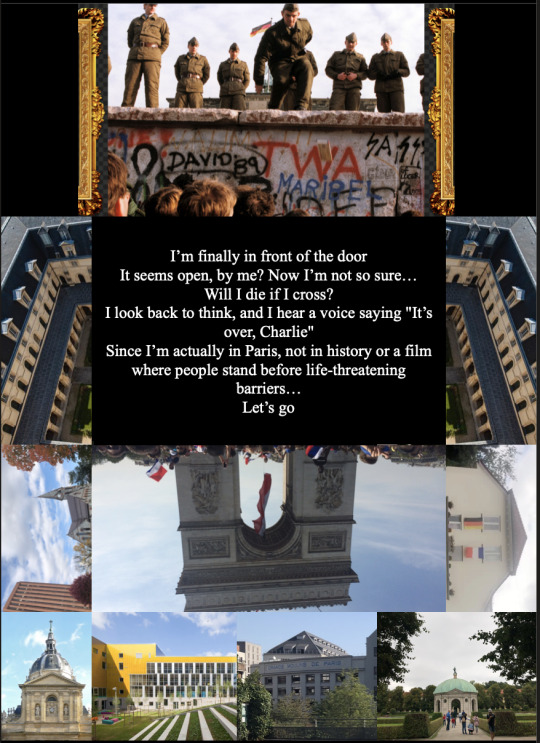

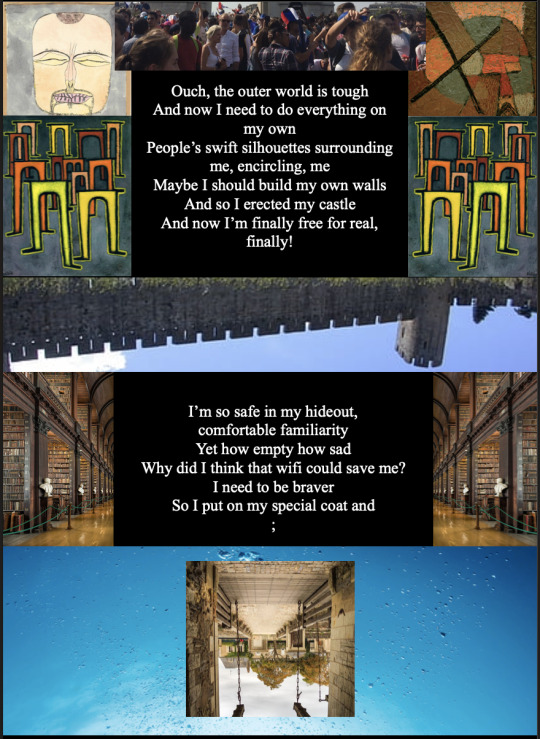

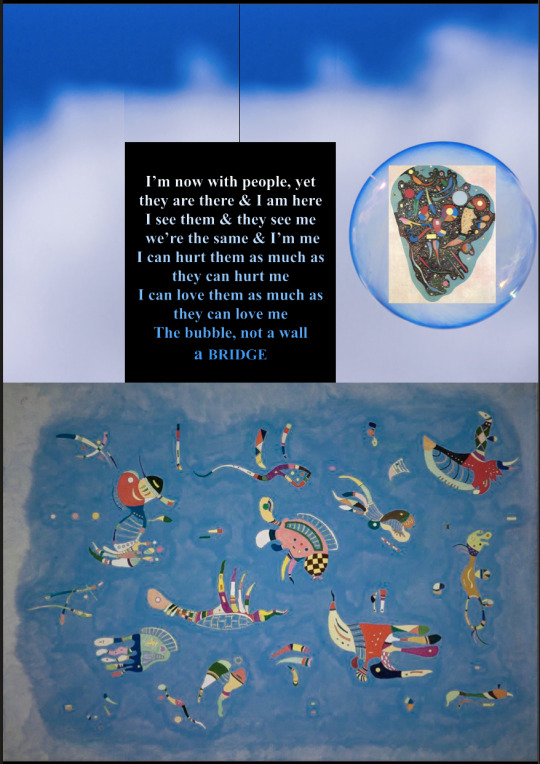

"Ramparts", a poem and collage artwork by me.

Thanks if you read it!

#just some#art#by me for a university contest#the theme was walls and borders#so I did this#poem#collage#thanks for just looking at it#thanks immensely for reading it#thanks astoundingly if you like it lol#sorry it's kinda blurry#no pdf on Tumblr and I'm not familiar with better formats :(#inspo is obviously#The Lorax#twenty one pilots#the truman show#vassily kandinsky#paul klee#warsaw ghetto#berlin wall#and more#walls#borders#freedom

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

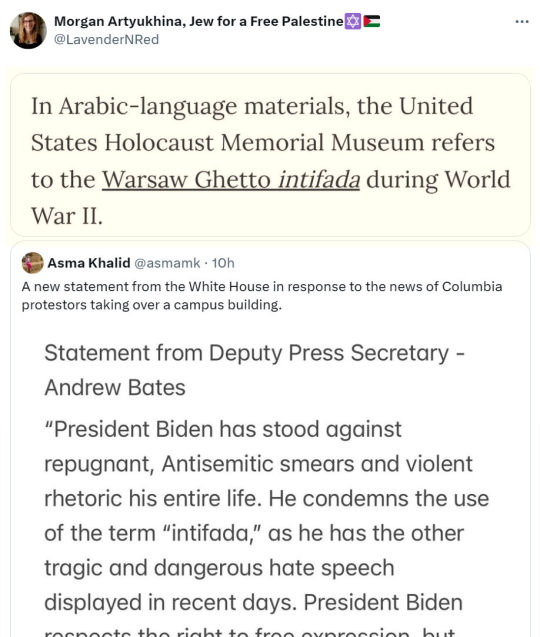

Intifada translates to “uprising” or “shaking off”

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Una formación de seis policías judíos en el gueto de Varsovia, julio de 1942

🇪🇸 La policía judía del gueto de Varsovia fue creada al mismo tiempo que el gueto y estaba compuesta por jóvenes bien educados, principalmente abogados y personas de clase alta. Al comienzo, la policía se encargaba del tráfico, la limpieza y el orden en el gueto, pero en 1941 tuvo que suministrar trabajadores forzados a las autoridades alemanas. En julio de 1942, cuando comenzaron las deportaciones masivas de judíos de Varsovia a Treblinka, la policía judía recibió la orden de reunir a los judíos para estas deportaciones. A los policías judíos se les prometió inmunidad para ellos y sus familias, y algunos creyeron que al cumplir con estas órdenes, estaban ayudando a salvar vidas judías. Sin embargo, al participar en las redadas, se convirtieron en el grupo más odiado dentro del gueto. A medida que las deportaciones continuaban, los policías judíos se dieron cuenta de que su propio destino también era incierto y empezaron a desertar, buscar empleo en los talleres del gueto o esconderse. En respuesta, los alemanes aplicaron medidas más duras, amenazando con arrestar a sus familias si no cumplían con la cuota diaria de deportados. El 21 de septiembre de 1942, durante Yom Kipur, la mayoría de la policía judía y sus familias fueron deportados a Treblinka, terminando así las deportaciones masivas en Varsovia.

🇺🇸 The Jewish police of the Warsaw ghetto were established simultaneously with the ghetto itself and were comprised of well-educated young people, mostly lawyers and individuals from the upper class. Initially, the police were responsible for traffic control, sanitation, and maintaining order within the ghetto, but in 1941, they were tasked with providing forced laborers to the German authorities. In July 1942, when the mass deportations of Jews from Warsaw to Treblinka began, the Jewish police were ordered to gather Jews for these deportations. The Jewish police were promised immunity for themselves and their families, and some believed that by following orders, they were helping to save Jewish lives. However, their participation in the raids made them the most hated group within the ghetto. As the deportations continued, the Jewish police realized that their own fate was uncertain, and they began to desert, seek employment in the ghetto's workshops, or go into hiding. In response, the Germans took harsher measures, threatening to arrest their families if they didn't meet the daily deportation quota. On September 21, 1942, during Yom Kippur, the majority of the Jewish police and their families were deported to Treblinka, marking the end of the mass deportations in Warsaw.

#treblinka#policía judía#judaism#judaísmo#judío#jewish#jewish history#historia judía#segunda guerra mundial#world war 2#world war ii#ghetto#warsaw ghetto#deportation#immunity#mass deportations#september 21 1942#1942#yom kippur#varsovia#gueto de varsovia

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today, 19th of April we celebrate the 81st anniversary of uprising in Warsaw Ghetto, in 1943.

Rest in peace to everybody, that decided to die for honour, every brave soul that showed what does it mean to fight.

For that day, people in Warsaw wear paper daffodils.

,,Potrafimy pięknie umierać i pięknie żyć”

#jewish#warsaw ghetto#poland#polish history#ww2 history#jewishuprising#Polin museum of polish Jews history#memory#remember#rest in peace

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

“a bad omen i saw over my home not long after seeing an exhibition about the fate of civilians in Warsaw Ghetto”, 2024/5784.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Girl looking at the ruins of the Warsaw Ghetto on April 3, 1946

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The story of the Oyneg Shabes archive. Between 1940 and 1943 a group of dedicated writers, led by historian Emanuel Ringeblum, secretly recorded daily Jewish existence in the Warsaw Ghetto. It would become history as survival. Anton Lesser narrates this new 10-part series revealing the lives, stories and destruction of the Ghetto.

With Elliot Levey, Alfred Molina, Tracy-Ann Oberman, Karl Prekopp and Simon Russell Beale (in episode 8)

All ten episodes are available here

More about the Ringelblum Archive

#Simon Russell Beale#Warsaw Ghetto#radio#Anton Lesser#Alfred Molina#Elliot Levey#Tracy-Ann Oberman#bbc radio 4#Oyneg Shabes archive#Emanuel Ringelblum#Wladyslaw Szlengel#2023

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Warsaw Ghetto Uprising Anniversary

On April 19, 1943, the Warsaw ghetto uprising began after German troops and police entered the ghetto to deport its surviving inhabitants. Jewish insurgents inside the ghetto resisted these efforts. This was the largest uprising by Jews during World War II and the first significant urban revolt against German occupation in Europe. By May 16, 1943, the Germans had crushed the uprising and deported surviving ghetto residents to concentration camps and killing centers.

2 notes

·

View notes