#triads of britain

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

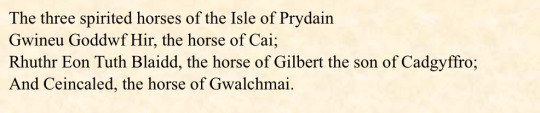

For anyone wondering, the triad is #42 in Rachel Bromwich's comprehensive collection.

There are many variations of the triad. The most common being:

Llwyt, horse of Alser son of Maelgwn and G6ineu Godwfhir, horse of Cai and Chethin Carn6law, horse of Iddon son of Ynyr Gwent

G6ineu or Gwineu Godwfhir means 'Chestnut Long-Neck' (remember google translate is limited to modern Welsh spellings, which the triads tend not to use)

Ceincaled or Kein Caled is the original form of Gringolet <3 (@gringolet)

Short king Gawain 💖

Extra

kay has a horse (whose name translates to long lasting wine on google translate??)

(welsh triad of horses)

#Arthurian art#other people's art#post stealing#triads of britain#rachel bromwich#cai#welsh#horses#translation#funny

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

Notable Sorcerers of British Mythology (other than Merlin)

King Bladdud, from Historia Regum Britanniae. Father of King Leir and Grandfather of Gonoril, Regan and Cordelia. The earliest known necromancer in Britain.

[...]

Celidoine, King of Scotland and North Wales, son of Nasciens and ancestor of Sir Lancelot and Galahad. Buried in Camelot.

From the Red Book of Hergest Welsh Triads: Math ap Mathonwy, King of Gwynedd, brother of Don, and uncle of his protege, Gwydion, the magician-trickster hero of the Mabinogi. Amongst other things, punished his wayward nephews for raping Goewin by shapeshifting them, tested Arianrhod's virginity with his wand (which she failed), and is co-creator of Blodeuwedd, the flower-bride of Lleu Llaw Gyffes. Uther Pendragon, King Arthur's father, who mentored Menw, one of Arthur's own enchanter-knights. Infamous for using shapeshifting to seduce Igraine, siring Arthur. This triad implies Uther himself was a practicioner of the magical arts and has his own apprentice, with the assistance of Merlin in Historia being Geoffrey of Monmouth's spin. Gwythelyn the Dwarf. Unknown, but his nephew-protege, Coll ap Collfrewy, is one of the mighty swineherds of Britain and the owner of the magical sow, Henwen.

From Iolo Morgannwg's own dubious triads (so take them with a grain of salt): Idris Gawr of Merionydd, of Cadair Idris fame. A huge giant learned in poetry, astronomy and philosophy, who's throne/chair is a mountain said to be able to grant poetic skill or madness. Gwydion fab Don, the trickster figure of the Mabinogi and student of his uncle Math. The Milky Way Galaxy is said to be his fortress. Gwyn ap Nudd, Lord of the Wild Hunt and King of the Fairies of Glastonbury. King Arthur's cousin and huntsman. Doomed by Arthur to fight Gwythyr ap Greidawl for the hand of Creiddylad until the End of the World.

*(Not included are Klingsor and Gansguoter of the German Arthurian Tradition)

It is very notable that many of these Sorcerers are Kings, lordly rulers in their own right.

#bladdud#uther pendragon#celidoine#math ap mathonwy#gwydion fab don#coll ap collfrewy#gwyn ap nudd#menwy ap teirgwaedd#idris gawr#iolo morgannwg#geoffrey of monmouth#welsh triads#red book of hergest#historia regum britanniae#arthuriana#british mythology#matter of britain#welsh literature#arthurian mythology

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

i want to see the orphan black style spinoff where all the different susans triad on earth find each other and start talking

#there are like 900 in britain and like six in new york city and then one in like. utah.#doctor who#dw spoilers#empire of death#rtd era 2#susan triad

24 notes

·

View notes

Link

Chapters: 12/12 Fandom: Harry Potter - J. K. Rowling Rating: Explicit Warnings: Creator Chose Not To Use Archive Warnings Relationships: Harry Potter/OC, Harry Potter/Severus Snape, Hermione Granger/Neville Longbottom/Draco Malfoy, Ron Weasley/Victor Krum, Ginny Weasley/OC, Percy Weasley/Luna Lovegood, Remus Lupin/Lucius Malfoy, Pansy Parkinson/OC Characters: Harry Potter, Severus Snape, Hermione Granger, Ronald Weasley, Neville Longbottom, Draco Malfoy, victor krum, Ginny Weasley, The Dursley's, Albus Dumbledore, Remus Lupin, Lucius Malfoy, Molly Weasley, Arthur Weasley, Percy Weasley, Cornelius Fudge, Dolores Umbridge, Luna Lovegood, Pansy Parkinson, Filius Flitwick, Fred and George Weasley, Bill Weasley, Charlie Weasley, Minerva McGonagall, Winky (Harry Potter), Dobby (Harry Potter), Several OC characters Additional Tags: Slash, Mpreg, Character Death, Violence, Angst, Humor, Gaelic accents, Deception, Post-Hogwarts AU, Post-Voldemort, Complete Summary:

After Harry rids the Wizarding World of Voldemort, his dreams of having a happy life of his own are dashed when the Ministry decides he's too dangerous to remain free. Harry escapes to start a new life, under a new identity unknown to everyone in the UK. He settles into his new life, begins a family and all seems well... but is it?

#Harry Potter#Fanfiction#ao3#snarry#hermione/neville/draco#ron/victor#remus/lucius#percy/luna#ginny/omc#pansy/omc#ginny bashing#Wizarding Britain Bashing#Fudge bashing#triad#mpreg#Harry is Breen Evans#Harry leaves Britain#murder#attempted murder#kidnapping#child endangerment#Horse ranch

0 notes

Text

Beginner’s Guide to Medieval Arthuriana

Just starting out at a loss for where to begin?

Here’s a guide for introductory Medieval texts and informational resources ordered from most newbie friendly to complex. Guidebooks and encyclopedias are listed last.

All PDFs link to my Google drive and can be found on my blog. This post will be updated as needed.

Pre-Existing Resources

Hi-Lo Arthuriana

♡ Loathly Lady Master Post ♡

Medieval Literature by Language

Retellings by Date

Films by Date

TV Shows by Date

Documentaries by Date

Arthurian Preservation Project

The Camelot Project

If this guide was helpful for you, please consider supporting me on Ko-Fi!

Medieval Literature

Page (No Knowledge Required)

The Vulgate Cycle | Navigation Guide | Vulgate Reader

The Wedding of Sir Gawain and Dame Ragnelle

The Marriage of Sir Gawain

Sir Gawain and The Green Knight

The Welsh Triads

Le Morte d'Arthur by Sir Thomas Malory

Squire (Base Knowledge Recommended)

The Mabinogion

Four Arthurian Romances by Chrétien de Troyes

Owain (Welsh) | Yvain (French) | Iwein (German)

Geraint (Welsh) | Erec (French)| Erec (German)

King Artus

Morien

Knight (Extensive Knowledge Recommended)

The History of The King's of Britain by Geoffrey of Monmouth

Alliterative Morte Arthure

Here Be Dragons (Weird or Arthurian Adjacent)

The Crop-Eared Dog

Perceforest | A Perceforest Reader | PDF courtesy of @sickfreaksirkay

The Fair Unknown (French) | Wigalois (German) | Vidvilt (Yiddish)

Guingamor, Lanval, Tyolet, & Bisclarevet by Marie of France

The Canterbury Tales by Geoffrey Chaucer

Grail Quest

Peredur (Welsh) | Perceval + Continuations (French) | Parzival (German)

The Crown by Heinrich von dem Türlin (Diu Crône)

The High Book of The Grail (Perlesvaus)

The History of The Holy Grail (Vulgate)

The Quest for The Holy Grail Part I (Post-Vulgate)

The Quest for The Holy Grail Part II (Post-Vulgate)

Merlin and The Grail by Robert de Boron

The Legend of The Grail | PDF courtesy of @sickfreaksirkay

Lancelot Texts

Knight of The Cart by Chretien de Troyes

Lanzelet by Ulrich von Zatzikhoven

Spanish Lancelot Ballads

Gawain Texts

Sir Gawain and The Green Knight

The Wedding of Sir Gawain and Dame Ragnelle

The Marriage of Sir Gawain

Sir Gawain and The Lady of Lys

The Knight of The Two Swords

The Turk and Sir Gawain

Perilous Graveyard | scan by @jewishlancelot

Tristan/Isolde Texts

Béroul & Les Folies

Prose Tristan (The Camelot Project)

Tristan and The Round Table (La Tavola Ritonda) | Italian Name Guide

The Romance of Tristan

Tristan and Iseult by Gottfried von Strassburg

Byelorussian Tristan

Educational/Informational Resources

Encyclopedias & Handbooks

Warriors of Arthur by John Matthews, Bob Stewart, & Richard Hook

The Arthurian Companion by Phyllis Ann Karr

The New Arthurian Encyclopedia by Norris J. Lacy

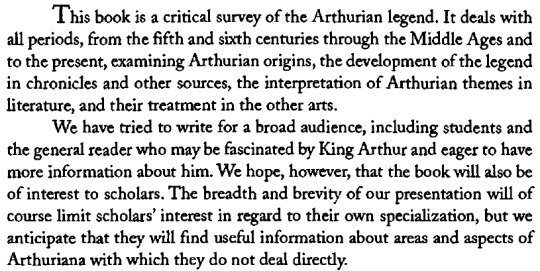

The Arthurian Handbook by Norris J. Lacy & Geoffrey Ashe

The Arthurian Name Dictionary by Christopher W. Bruce

Essays & Guides

A Companion to Chrétien de Troyes edited by Joan Tasker & Norris J. Lacy

A Companion to Malory edited by Elizabeth Archibald

A Companion to The Lancelot-Grail Cycle edited by Carol Dover

Arthur in Welsh Medieval Literature by O. J. Padel

Diu Crône and The Medieval Arthurian Cycle by Neil Thomas

Wirnt von Gravenberg's Wigalois: Intertextuality & Interpretation by Neil Thomas

The Legend of Sir Lancelot du Lac by Jessie Weston

The Legend of Sir Gawain by Jessie Weston

#arthuriana#arthurian legend#arthurian mythology#arthurian literature#king arthur#queen guinevere#sir gawain#sir lancelot#sir perceval#sir percival#sir galahad#sir tristan#queen isolde#history#resource#my post

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Arthurian non fiction recommendation list

I don't talk much about non fiction arthuriana because I usually don't read much of it but I have an immense love for some specific arthurian non fiction books.

I am not really interested in historical Arthur, but I love to see the evolution and addition of arthurian elements in literautre through time and space. For this reason, my absolute favorite is the series "The Arthur of the..."

Here are some:

Arthur of the Welsh (the one I always take with me! It has information of the triads, early Welsh texts and poems, Culhwch and Olwen and the Mabinogion arthurian texts)

Arthur of the French (in particular has a section about Arthur in modern French movies and fiction!)

Arthur of the Italians (this I did not check as I read the texts in Italian, but I know it has information on the Rustichello da Pisa text, the Tavola Ritonda and i Cantari, the ones with Gaia as a character)

Arthur of the Low Countries (one of my favorite because it has full summaries of some Dutch texts that are impossible to find in English like Walewein, Moriaen, Walewein ende Keye, Roel Zemel)

Arthur of the North (has some summaries of some really hard to find stuff arthurian like Ívens saga, Erex saga, Parcevals saga, various Nordic ballads, Hærra Ivan Leons riddare)

Arthur of the Germans (another good one! It has info on a bunch of German texts that are hard to find like Wigamur, various fragments, Tristan traditions)

Arthur of Medieval Latin literature (for the older stuff, like Geoffrey of Monmouth, Nennius and Life of Saints)

Arthur of the English (if you are really into Malory)

Arthur of the Iberians (I have not fully delved into this, but the chapters seem to be about the reception of arthurian matter in Spain and Portugal)

Basically, different authors tackle the arthurian traditions (more or less obscure) from different areas and time periods.

In general, if you like Welsh arthuriana anything written by Rachel Bromwich will be your friend, especially "Trioedd Ynys Prydein: The Triads of the Island of Britain".

For general information:

The Arthurian Name Dictionary (Bruce) - this used to be online, not anymore, but you can still access it through the archive here

The Arthurian companion (Phyllis Ann Karr)

The Oxford Guide to Arthurian Literature and Legend (Alan Lupack)

The Arthurian Encyclopedia (Lacy)

The Illustrated Encyclopaedia of Arthurian Legends (Coghlan)

If you are looking for more translated texts you can check here for free downloads, but if you would like books, here are some:

The Romance of Arthur: An Anthology of Medieval Texts in Translation (Wilhelm)

This book contains translations of:

Culhwch and Olwen Roman de Brut Brut Some Chretien de Troyes Some Parzival excerpts The saga of the mantle Beroul's Romance of Tristan Thomas of Britain's Romance of Tristan Lanval The Honeysuckle Cantare on the Death of Tristan Suite du Merlin Prose Merlin Sir Gawain and the Green Knight The Wedding of Sir Gawain and Dame Ragnelle De ortu Waluuanii nepotis Arthuri

The Book of Arthur: Lost Tales From the Round Table (Matthews John)

This book contains translations of:

(Celtic Tales) The Life of Merlin The Madness of Tristan The Adventures of the Eagle Boy The Adventures of Melora and Orlando The Story of the Crop-eared dog Visit of the Grey Ham The Story of Lanval

(Tales of Gawain) The rise of Gawain Gawain and the Carl of Carlisle The Wedding of Sir Gawain and Dame Ragnelle The adventures of Tarn Wathelyn The Mule without a bridle The knight of the Sword Gorlagros and Gawain

(Medieval texts) The knight of the parrot The vows of King Arthur and his Knights The fair unknown Arthur and Gorlagon Guingamor and Guerrehes The story of Meriadoc The story of Grisandole The Story of Perceval Sir Cleges The Boy and the Mantle The lay of Tyolet Jaufre The story of Lanzalet And some final notes

#lancelot#arthurian legend#camelot#king arthur#recs#arthurian non fiction#essays#non fiction#arthur of the#favs#rec#books#resources#resource

84 notes

·

View notes

Text

Don't You Want Me Like I Want You?

Summary: There was a time when you and Lieutenant Price were as close as could be.

But after one drunken mistake years ago, you've since done everything you could to keep yourself as far away from him as possible.

Up until this particular night.

As his former Captain, you should've known that there was simply no way he would ever give up on hunting you down.

Rating: NC-17

Pairing: Older F!Reader/Younger!Price (Reader is in her 30s & John is in his 20s)

**Warning: contains age gaps and drunken sex--please take discretion before proceeding!**

hi 🧍♀️

recently i had the chance to visit seoul and idk seeing all sorts of soldiers reuniting with their lovers for the holidays + being unable to escape "apt" no matter where i went + continuing to listen to yandere male kouhai x female senpai drama cds resulted in this !!!

--------------------

A sigh left your lips before you gulped down a mouthful of champagne from your glass.

They grow up so fast.

Once near religiously clean-shaven to now sporting a thick, well-groomed mustache. An almost naively optimistic glimmer in the eye to a much more steely and narrowed gaze that only further experiences in life could naturally curate. Tall, lean muscle that had since bulkened into a sinewy pillar of brawn.

To everyone in attendance at tonight's military gala in the heart of London, he was the newly appointed Captain John Price.

But to you, always and more, he was Lieutenant John Price.

Having dedicated most of his life in the military–from the latter half of his adolescence to essentially the entirety of his 20s–, he was primed to be nothing short of legendary in his career. Skilled, resilient, and–most of all–mindful. He could be trusted with Britain’s–nay, the world’s–finest soldiers and see them not just to victory, but safe and sound back home as well. Similarly, he still maintained compassion to the plights of the innocents and the causes of opposing forces, seeking to preserve life as much as he could rather than callously brushing off all as mere collateral damage.

For you, it was the greatest honor to have overseen his growth and development as his superior.

As his Captain.

You could say that it was by fate that the two of you would ever cross paths, but really it was because of Kate.

Kate Laswell, of course.

One of your dearest friends and your longest ally.

With the both of you being among the few women working your way up the ropes within the realm of the military, it was a persistent uphill battle for you both to excel and progress further enough to have your accomplishments inside and outside the field validated. The hardships faced both abroad in volatile territory and within the stifling restraints of bureaucracy had the two of you as close as could be.

And when a job needed swift and efficient execution, she knew she could reliably call upon you.

But then there came a time she needed more help than you could provide.

Enter one John Price.

Whereas you had only a few years difference apart in age with Kate–her being older at that–, you had a full decade over John, who was to serve as the lieutenant to your captain.

While you were used to any of your male counterparts–regardless of their seniority or their status as subordinates–to scoff or sneer at you upon first meeting, he was as respectful as could be.

No smarmy jabs about your capabilities as a woman, no piggish snipes at your age or your looks, no overly critical questioning of your methods.

He abided by your leadership with damn near reverence and even went as far as to bark down at any man–sergeant, lieutenant, corporal–who dared to see you as beneath themselves.

It was the start of a precious friendship, one that spanned across the years and across the world. No matter the mission or location, whether there was need for infiltrating the underbelly of the Triads, disposing of ultranationalist leaders in Russia, thwarting the plans for a full global scale terrorist strike across the world, you and Price made for the perfect pair.

In the sense of a mentor and a student, obviously. You couldn’t even begin to think of tainting such a precious dynamic.

That very same compassion and mindfulness he carried throughout his career was honed and nurtured under your tutelage. Though, you were usually the first to tease him whenever he spoke in such profound one-liners of grandeur.

“Movie star” was one of many nicknames you had for him.

It was just a shame that you could not look at your friendship with fondness in your heart any more.

The reason for such was why you were deep into a bottle of champagne during tonight’s evening affair.

All while you prayed and prayed that no affair of any sort would come about.

You wished you weren’t even here to begin with–especially not while you were doing your best to try and camouflage against one of the gala hall’s many ornamented flower arrangements in a black dress and heels.

It had been a little over 5 years since you both retired and had last seen Price.

While you were more than prepared to have it extend to a full decade, a call from an exasperated Kate had you reluctantly make the trip out to London for tonight’s celebration, with his promotion to captain among the many highlights.

She needed him to take lead of an extensive campaign in Brazil but he had been shockingly adamant in his refusal–albeit with one exception:

“I want to see my Captain again, Laswell.”

The groaned “Katherine” you let out over the phone was burdened and heavy upon hearing her recount his singular term.

Yet while the same couldn’t exactly be said about your current connection with Price, your friendship with Kate was as strong as it ever was and as hesitant as you felt, you agreed to attend.

After all, you simply had to swing by the gala–that didn’t mean you had to talk to Price. He only said he wanted to see you. With how desperately you were trying to utilize every bit of semantics for salvation, you took any chance you could.

Because simply put, there was a conversation that you just didn’t want to have with him.

A follow-up to a night from just shy of 5 years ago that you had been running from all this time.

You had since done your best to blank out the happenings of that evening, but your skin could still feel the phantoms of body heat and muscle haunting over every inch regardless.

Despite all the repressing as you had done across the days, the months, the years, some details were just impossible to completely stamp out:

December in Seoul. Campaign celebration. Your soju. His hotel room.

Drunkenly teaching him a game of mahjong led to the idea of sweetening the prize beyond mere bragging rights between the two of you.

Release a few salacious secrets or help unwind a knot or two in the shoulder with a massage.

It was meant to be a choice of one or the other but it didn’t take much more of both to be tangled, much like the two of you on his bed.

“So this is why the guys keep teasing you with those mama’s boy comments,” was something you remember giggling out while you had Price nursing from your breasts, his lips hungrily sucking at your nipples while his hands fondled your chest.

He chuckled lowly against your skin, his eyes twinkling as he peeked up at you with a wink. “I wear it with pride–always preferred a dignified woman over a bratty girl.”

You found yourself slinking over to the bar once again, careful to keep watch of any sign of Price. He had finished giving his acceptance speech–his frequent scans across the gala hall did not escape you while you were sinking low in your seat and hiding behind gala pamphlets–and was mingling with the likes of the ever dignified Commander Shepherd and other elites from the British Army with cigars and whiskey.

They truly grow up so fast.

Though, given his penchant for the finer things in life, it only made you swelter within your dress all the more with another memory from that night.

Your body caged in Price’s arms, your nails digging into his chiseled forearms, his naked body pressed flush against yours, his cock hammering into your core from behind, his voice in a hiss as he sought to mark your skin and leave his claim, his ownership.

“That’s right, Captain. Cum for your lieutenant and become mine…!”

You shuddered hard, head thrown back against his shoulder, back arching off against his chest. Never had any man–all of whom were much closer to you in age–made you feel like this.

And so, for once, you did as he ordered.

Partially.

Because you couldn’t become his.

You refused.

Price was well a decade younger than you, with your night together a drunken fling and–in your eyes–a tarnishing of the pure connection you shared with him as mentor and student.

All because you weren’t thinking that night.

You were supposed to serve as an example of what discipline and merit could achieve, especially against all odds.

Instead, you happily lied beneath him, legs spread wide to accommodate every eager thrust and every sticky load he pumped into you with.

It was at this recollection that you paused midway to the bar.

Perhaps it was time to call it a night instead, else risk more possible drunken mistakes, whether with Price or with someone else.

With this, you shifted direction to head over to where Kate and her wife were seated–just a quick bye and you would be out to find freedom and ease of mind back at your hotel room.

And then, you felt it again.

The manifestation of a haunting phantom.

The weight of two heavy hands coming to rest right on top of your shoulders.

“There you are–just the woman I’ve been looking for.”

Whatever drunken flushed heat in your skin turned ice cold as a voice–now roughened and deeper from when you last heard it–spoke out to you.

Your body was pulled back into an embrace with utmost ease, solid muscle slotting perfectly against your backside.

You dared not to look back.

But you knew he was smiling by the mirth in his voice.

“I’m being called for another speech, but I’ll be waiting for you for mahjong later, Captain. Still have a few loose ends I’ve been meaning to tie up.”

His fingers caught along the strap of your dress, running over the thin fabric right as he brought his lips right to the corner of your mouth for a quick kiss, the bristles of his mustache raking over your skin.

When he drew away, you caught the definite quirk of a triumphant grin as he proceeded to take his leave.

You almost shattered your champagne glass.

--------------------

tysm for reading !!! i hope you enjoyed !!! literally as soon as i returned from my trip this past weekend, i was DETERMINED to get this done and while i actually did have some bits i was inclined to elaborate on, i controlled myself because otherwise i knew i was gonna be locked tf in on context alone and i already have my "bodyguard" piece to catch up on !!!!!!!!! 😭😭

#captain john price x reader#captain john price x you#call of duty x reader#cod x reader#price x reader#captain john price smut#call of duty smut#reader insert#Fic#super freaknasty writing

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

This is the book:

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/23258394

Here come Welsh Triad titles confusing me like: what does this mean?

Is it freckles? Is it a metaphor I'm missing? I don't know--I haven't found anything about it on my research!

Meanwhile, I guess I'm supposed to take this as it's meant to be taken (for lack of a better term)?

If anybody knows more, I'd be very thankful!

67 notes

·

View notes

Note

hi anon again and no you didn't bore me at ALL!! i loved hearing about the welsh arthurian mythos and i want to know more. please tell me where i can read about them and tell me interesting facts you like about it!!!!!!!!

Anon, I am hugging u. Thank u for saying I didn't bore u!!! So glad u liked my mad ramblings!!!

Okay, so The Mabinogion is probably a good place to start. It contains four branches of Welsh mythology which sorta ties into Welsh Arthuriana because some of the gods (Manawydan, Pryderi, Gwyn ap Nudd, Mabon ap Modron, Bendigeidfran's head.) pop up in both. Also, it contains Culhwch and Olwen which is a tale concerning Arthur's cousin Culhwch going on a quest with Arthur and his knights so he can marry Ysbaddaden Pencawr's daughter, Olwen. It's believed to be the earliest-written Arthurian romance preserved in manuscripts. It also contains three other Arthurian romances which are either Welsh tales that have been adapted by De Troyes and then back into Welsh but with a twist, or just based on French romance tales that have been repressed for the Welsh. (Idk really know which one is true but they're all fun!!!)

There's also the tales of Lludd and Llefelys (a personal fave.), The Dream of Rhonabwy (a fictional dream containing Arthurian characters but also actually REAL LIFE Welsh ruler Madog ap Maredudd.), AND The Dream of Macsen Wledig which is essentially one man's quest to bonk a hot lady in Caernarfon. (Tbf, Macsen Wledig is somewhat of an Arthurian figure in his own right cuz he too is seen as a Mab Darogan (prophecised son) in Welsh Culture because he united the Welsh under one banner, and then died, and then Wales immediately split into kingdoms again.)

You can either access Charlotte Guest's translation which I am sure @queer-ragnelle has scanned, or Sioned Davies' new translation which has handy dandy footnotes and such.

There's also Gwyn Jones and Thomas Jones translation which uses a lot of the medieval language but was also made into a beautifully illustrated book by Alan Lee (An illustrator who is famous for LOTR illustrations). Jeffrey Gantz's edition is, I think, the most recently published edition but you can tear Sioned Davies from my COLD DEAD HANDS. Or, if you like poetry, one of my old English lit lecturers, Matthew Francis, has done a poetry version of the four branches! It's amazing!!!!

Also, Naxos has an audiobook version read by Matt Addis which uses Guest's translation but is good for listening to. I love it.

(You'll also want Trystan ac Essyllt, 'The Triads of Britain' and 'The Arthur of the Welsh' which are written by Rachel Bromwich, and I recommend O.J. Padel's 'Arthur in Medieval Welsh Literature' for more on how he's portrayed through that. And if you like modern re-tellings Seren Books has a box set of them! Each one is a re-telling of each branch of the Mabinogi, Culhwch and Olwen, the three romances, and the others. Very fun!)

Now in terms of my favourite things: Peredur being Urien's first cousin irl made me be like WHAT? Like, they're SO interconnected it's MADNESS. Urien, Owain, and Peredur are all related. Also, the fact that Welsh Arthuriana has swallowed up eight irl monarchs (Edern ap Nudd, Cunedda, Owain, Urien, Geraint, Peredur, Macsen Wledig, Cynon ap Clydno (Owain's sister, Morfudd's, lover), and Cynyr Ceinfarfog (Cai's dad), one poetic genius (Taliesin - who wrote about Urien as it goes!!! BTW read the tale of Taliesin. Sjdddkxk. The Jones and Jones translation has it, the Davies translation of the Mabinogi does not.), Emrys Wyllt who was the inspiration for Merlin, and sixty-seven thousand gods, as well as a few saints.

My favourite fact about Welsh Arthuriana is probably that Gwalchmai and Peredur probs had a relationship, Arthur is canonically in love with his boat, Cai literally says 'if u held my dick like that I'd die.' in Culhwch and Olwen, and Gwenhwyfar's a fuckin GIANTESS. 😍😍😍😍 I have many more facts but like I don't want to clutter the feed!!!!!

Hope my rambles were helpful in some way! Have a good day/night, anon! ☺️🧡

#anon ask#anon ur super nice djdjdkd#arthuriana#welsh mythology#mabinogion#the mabinogion#welsh myth#y mabinogi#the mabinogi#arthurian legend#arthurian mythology#oh fuck also the mab is a good book rec too! its a modern retelling and its targeted for kids but michael sheen does the foreword!#its SO FUN#the third branch is written from Cigfa's perspective and it SLAPS#king arthur#arthur pendragon#merlin#queen guinevere#owain ap urien#urien rheged#taliesin#sir kay#the four branches of the mabinogi#charlotte guest#welsh folklore#welsh legends#arthurian literature#arthurian legends

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Witnessing Greatness

Thinking about the most recent episode of Doctor Who, I find myself reminded of Roger Corman, who died last month. Corman was a producer and director of b-movies and television. He was also beloved by industry titans due to his work ethic and ingenuity as a filmmaker. What made Corman so unique is how he dealt with limitations. If an aspect of one of his films was lacking, he made up for it in other departments. If the effects were bad, the script had to be great. If the acting was hammy, he’d make sure the music gave it strength. Instead of spreading everything thin, he knew that giving a little bit more attention to individual elements would make for an overall better experience. If you’re not firing on all cylinders, make sure the ones that do are firing brightly.

“Rogue,” is an episode with many bright shining points, lighting up the sky of Regency Era Britain. But lost within that light are a few flickering bulbs that could stand to be turned a bit tighter. However, it’s not as though we’re poking around in the dark. Without a doubt, the brightest star in the Whoniverse at the moment is Ncuti Gatwa. In a stand-out performance from a series of stand-out performances, Gatwa has really outdone himself this week and I can’t wait to talk about it. The folks at Bad Wolf Studios have refused to spread things thin, but no story is perfect. For as much as I enjoyed this week’s episode, I didn’t have to reach far to find problems. But when I’m smiling this much, it’s harder to care.

It’s funny how a week ago I said I didn’t like fan theories and then promptly made one. Just as promptly, I am now abandoning that theory. After the trailer for next week’s episode, I no longer think Susan Twist is the Rani. I officially don’t know what I think. I kind of love that. I have seen the rumours of Susan Twist being Sutekh. Maybe the Doctor is in the Land of Fiction. The name S Triad is an anagram of the word TARDIS. Perhaps she’s the original owner of the TARDIS coming to retrieve it. The point is, she could be anyone, and I am not all that worried about it. Why that feels important is that I was often full of dread waiting for Chibnall’s next big reveal. I didn’t look forward to the ways in which he might next waste a concept by not properly exploring it. So being in a place where I am game for whatever feels zen.

Having two new writers this week was a major draw for me. I’ve seen what both Davies and Moffat can do, the good and the bad. This is the first time all season where I felt like we were truly wandering into the unknown. I did watch Loki season one, so I was familiar with Kate Herron’s work, but not as a writer. I was even less familiar with Briony Redman. But like I said, I’m game for whatever. The pair bring a metatextual reading to the Regency Era drama that fits Doctor Who’s brand of camp. I was reminded of Kate Beaton’s satirical comics from her “Hark! A Vagrant” series. “Rogue,” acts as a sort of love-letter to Jane Austen, so it’s only appropriate that they treat it with a playful touch. The Doctor and Ruby aren’t just visiting Bath in 1813, they’re cosplaying Bridgerton. But they’re not the only anachronistic party goers. This bash is about to go to the birds.

Leading up to this episode, an article in Doctor Who Magazine had given us random lines of dialogue from each story, including this one. However, the line “Psychic earrings. Choreography beamed into your motor system. Tap twice to choose your moves. It's like instant Strictly!” left me a bit nervous. We were fresh off of “The Devil’s Chord,” and part of me was wondering if they weren’t suddenly turning Doctor Who into a variety show. I’m joking a little, but I was rather relieved when the line turned out to be about dancing at the Duchess’ ball. The Doctor and Ruby are dressed to the nines in their period appropriate clothing. I love the idea of the Doctor wearing more from his wardrobe as it’s always been fun in the past. Tom Baker’s tartan tam o’ shanter in “Terror of the Zygons,” is one of his most iconic costumes. Ncuti said in an interview that he wanted his costume to make him look like he owned land. It’s a brilliant image to depict when you consider the Regency Era was merely four years away from the abolition of slavery in Britain.

The Regency Era also brought with it a change in men’s attire. Dandies like Beau Brummell popularised a look of comfort and wealth while simultaneously streamlining much of the frills from 18th century fashion. It’s funny to look at the ruffles of a dandy’s attire and consider it anything other than flamboyant, but it was a considerable shift toward more conservative styles. While women’s fashion continued to evolve, men’s fashion stagnated a bit. A standard had been established and you can still see its influence today with the basic suit and tie combo. No wonder the Doctors often dress like variations on Edwardian fashion.

The opulence of the period led to a lot of scandalising and gossip, which has given us centuries of great drama. While I’ve never read “Emma,” I have seen “Clueless.” I’ve never watched Bridgerton, but I can still get into the costuming and pomp. Basically you don’t need to be a fan of the genre to know the tropes. It was a nice change of pace that it was Ruby’s love for a tv show that puts things into motion. The Doctor and Ruby are tourists as much as the Chuldur, but with far less deadly consequences. Both groups are there to experience the emotional highs of the time, but the Chuldur don’t care who they hurt in order to do it. This of course is why Rogue, a bounty hunter, has also crashed the party.

You’ll be pleased to know I actually remembered to watch “Doctor Who Unleashed,” this week. Partly because I had some questions, but mostly because I wanted to hear them talk about the costumes and make-up effects. Davies mentioned that the season hadn’t yet had its baddie in a mask trying to take over the world, which I love that he considers. If you read my review of “The Witchfinders,” you may recall how much I appreciated the Morax being scenery chewing people in latex makeup. There’s something essentially Doctor Who about bug eyed monsters (sorry Sydney) and there’s something very RTD when those monsters have animal heads. Davies is now confirmed as a furry, I’m calling it.

The Chuldur share their appearance with birds, something we don’t often see in Doctor Who. I’m trying to recall bird villains from the show and I am coming up a bit short. There were the Shansheeth in the Sarah Jane Adventures, those bird people on Varos, that heavenly chicken from “The Time Monster,” and the Black Guardian’s hat. Considering all of the reptiles we get, I’m surprised we’ve gotten so few birds. If you also watched the Unleashed episode, you may have noticed that they digitally changed the bird version of Emily’s beak from black to orange. It’s the Vinvocci’s green faces from “The End of Time,” all over again! What’s funny is that this change in Emily’s beak gives her something of a penguin appearance. It’s not exactly the shapeshifting penguin I was hoping for, but I digress.

Speaking of shapeshifting, I rather enjoyed the Chuldur’s unique method of doing so. If you recall, when the Duchess spots her servant out in the garden, the bird form of the servant is played by the same actor as the servant. It’s not until she takes the form of the Duchess that her bird form also takes on the resemblance of Indira Varma. You don’t usually see that and I admire them for making two versions of the same makeup, if nothing else. Doctor Who has had its share of shapeshifters, so it’s nice to see them changing up the formula a bit. Unfortunately for the Duchess, this isn’t a Zygon type of body snatching where you have to keep the person you’re copying alive.

Ruby’s psychic earrings are doing a treat until they begin picking up interference from Rogue’s tech. A lot of people have mentioned that this episode seems to borrow a lot from “An Empty Child,” and so it’s only appropriate that the Doctor does a scan for alien tech. The source of the interference directs the Doctor toward the balcony where Rogue stands brooding. Meanwhile, the Chuldur version of Lord Barton has taken a liking to Ruby. The Duchess, still human at this point, attempts to introduce them, but Ruby is not impressed by the pompous dandy, referring to him as Lord Stilton. As Ruby strops away she notices a painting of Susan Twist’s character as an old matron. The Duchess refers to her as “the Duke’s late mother,” whose eyes still follow her around the room in judgement.

The Duchess takes her leave to the garden where she meets her fate with the Chuldur masquerading as her servant. We get a bit more of a look at what exactly the Chuldur do when they take over your body. What’s left of the duchess is little more than a desiccated husk. Meanwhile, in the study, Ruby has stumbled upon a rather intimate moment between Lord Barton and Emily. The bookcase obscuring her from the two frames them like a television screen. Ruby is unable to look away from the real life Bridgerton scene playing out in front of her. The Lord tells Emily that he will not marry her which would leave her ruined, but he is compelled by her nonetheless. However, before they can kiss, Ruby knocks a pile of books onto her head causing a disturbance. I rather loved this moment for Millie Gibson. It’s rare that women get to be portrayed as clumsy and that book definitely bonked her on the head. A great bit of physical comedy.

The Lord storms out of the room leaving Emily and Ruby to talk. Removed from the framing of the bookshelf, Ruby finds her compassion once more and comforts Emily. After all, Lord Barton was being a bit of an ass toward her. Emily is amused by Ruby’s modern sensibilities and lack of finery. You could tell this scene was written by two women as they actually take the time to let them have this moment. Meanwhile, the Doctor and Rogue take a stroll through the garden in order to size one another up. There’s a flirtatious energy between the two but a wary tension underlies the conversation. The Doctor muses about the stars, but on a terrestrial level. It’s not until he finds the Duchess’ shoe and then the rest of her that he gives away that he is not of this world. Rogue sees the Doctor’s sonic screwdriver and begins to suspect the Doctor is a Chuldur in disguise. The two confront one another as the culprit, but Rogue has the bigger gun.

Still comparing sizes, the Doctor and Rogue compare ships like they were Ten and Eleven comparing sonic screwdrivers. Speaking of sonic screwdrivers, it feels appropriate that the Doctor’s sonic would match his outfit. That’s so Fifteen. He’s a fashionable Doctor, so of course he would accessorise. It’s like they made his wardrobe and accessories with cosplay in mind. Rogue’s costume is also noteworthy. People have drawn comparisons between Rogue and Jack Harkness and it’s not difficult to understand. His long coat draws parallels to that of Jacks and he even mentions assembling cabinets in regards to the sonic. But what’s equally interesting is how Rogue’s gun resembles the type of handgun you would see in a Regency Era duel. Its barrel resembles that of a blunderbuss. He’s either deep undercover, or he’s got a thing for cosplay himself.

Rogue doesn’t get a lot of time for character development, but they do give him a few little moments, mostly through environmental storytelling. He has a striking birdlike ship fit for a heroic rogue, but inside it’s dirty and depressing. Possibly most telling on Rogue’s ship are the set of orange dice on his table. Rogue gets his name from Dungeons and Dragons, but beyond being a geek, these dice could tell us more about his personality. We learn that Rogue has lost someone, perhaps these dice belonged to them. Perhaps he is unable to move the dice from that spot because he didn’t leave them there. We also learn later that Rogue isn’t a very strong roleplayer. He’s quieter and more thoughtful in his improvisation. Perhaps his staged tryst was the first time anyone has asked him to roleplay since losing his partner. Either way, Jonathan Groff plays it with a vulnerable subtlety, and I loved it.

Speaking of loved it, we have now reached the portion of this article where I gush over Ncuti Gatwa. Now, I need to preface this by reminding you all that I have always been pro-Ncuti. I adored his portrayal of Eric Effiong in Sex Education. I never doubted for a second that he could pull it off. However, it wasn’t until this episode that his Doctor finally crystalised for me. We’ve seen that his Doctor could be flirtatious and fun, but we hadn’t yet seen the way in which he could use that to do Doctory things. We’ve had hot Doctors, but we’ve never had a Doctor who was so effortlessly hot. He’s hot in the same way the Second Doctor was bumbling, as in it’s almost a distraction from what he’s actually doing. It actually makes him slightly terrifying.

Even as his Doctor is standing in a trap, he’s able to use his charm to buy time. Also, once again the Doctor is stepping onto things that can kill him. An odd recurring theme. He maintains an air of authority even in the face of danger and that is so the Doctor. When the Doctor finds Rogue’s music playlist I think I may have melted. How could anyone incinerate such a beautiful person? How could you not want to dance right along with him? As much as I loved this scene and the meta reference to Astrid Perth, it does also buckle a bit under itself. First of all, wouldn’t the Doctor knowing an Earth song like “Can’t Get You Out of My Head,” make you question whether he was a Chuldur? Sure, they know Bridgerton, but it would be enough to give me pause. Furthermore, I’m not sure how seeing the Doctor’s many faces would cause you to not think he’s a shapeshifter. Kind of odd that one other face means shapeshifter but eighteen other faces don’t. Wait, did I say eighteen?

When I had first watched this episode, I didn’t immediately recognise Richard E Grant as the mysterious extra face in the lineup of past Doctors. We now have three extra faces in the form of Jodie Whittaker, Jo Martin, and David Tennant (again), but this extra Doctor wasn’t registering for me. At first I thought he was the Valeyard, and then I thought he looked a bit like Jim Broadbent, which is ironic considering “The Curse of Fatal Death.” It wasn’t until I got online afterward and saw people saying Richard E Grant that I could see it. I wasn’t even 100% convinced it was him, but I’ve heard they actually took new footage of Grant for that scene, so I guess it’s him. The more interesting question is which him is he? Is this the Shalka Doctor or the Fatal Death Doctor? Maybe he’s both. Maybe he’s neither. This wouldn’t be the first time they’ve given us retroactive Doctors. Moffat gave us the War Doctor to great effect. But despite a strong performance from Jo Martin, Chibnall did a piss poor job of establishing the Fugitive Doctor as a character. I’d love to get excited for this mystery incarnation, but I’m taking a Tim Gunn stance in the meantime- “Make it work.”

With Rogue now on his side, the Doctor takes him to his TARDIS so they can recalibrate his triform transporter to be non-lethal. Recently in an interview, Ncuti Gatwa mentioned he had gotten onto his agent about playing someone like the Doctor or Willy Wonka. It felt a bit like wish fulfilment for his Doctor to sing “Pure Imagination,” to Rogue as they entered the TARDIS. I really loved Jonathan Groff’s slow growing infatuation with the Doctor. I’m a big fan of “Mindhunter,” but it’s a very heavy show, so it was fun to see him in a more playful role. In many ways, Rogue feels like a bit of River Song and a bit of Jack Harkness. He’s something of a reboot and remix at the same time. I don’t doubt we will see him again, which would be a nice chance to give him some much needed character development, but for the time being, we’ve been given enough to work with.

The Doctor and Rogue’s plan is to draw the Chuldur to them by exploiting their love for drama and scandal. What better way to whip people into a frenzy in 1813 Britain than for two men to share a passionate dance together? Besties, I’ll be real, I was grinning from ear to ear. Watching Gatwa and Groff dance was very exciting. I’ve seen people complain that the Doctor and Rogue’s romance felt rushed compared to the “slow burn,” of Yaz and Thirteen. Slow burn is a funny way of saying “non-existent for two seasons.” And I would much rather see two men share a passionate kiss than two women share a passionate ice cream. What’s wild is that I’m not usually the kind of person who likes the Doctor to have romantic relationships. They managed without them for 26 seasons. However, due to Ncuti’s emotional availability, it works for me. I can buy that his time with Donna might have left him more open to romance. Furthermore, this is the antithesis of queerbaiting. Ice cream is not a payoff.

The Doctor ends the dance by staging an argument with Rogue and calling him a cad. But Rogue doesn’t respond in turn with the same volatile energy. There’s a hesitation on his end that feels personal. As I mentioned before, perhaps this is him working up the courage to roleplay again. Perhaps his lost partner was more the avid roleplayer between the two of them. Or perhaps Rogue simply has a softer approach. What I loved is that his marriage proposal felt equally as shocking, but in a more emotional manner. It even feels like it takes the Doctor by surprise. There’s a moment where it actually feels like a real proposal. The Doctor says he can’t and you almost believe he considered it. Or maybe the Doctor can’t even pretend to say yes because of his marriage with River song. If he undoes their wedding maybe it can revert us back to hot air balloon cars, Winston Churchill, and pterodactyls.

Not to be left out, Millie Gibson has gotten a lot of time to shine in this story as well. She does a fair bit of choreography, but there is one bit of her choreography of which I was a bit disappointed. After learning that Ruby is from the future, Emily reveals herself to be a Chuldur, and she wants to cosplay as Ruby next. However, Ruby’s psychic earrings come with a battle mode, which complicates things for the feathered fiend. My disappointment however, stems from the fact that they kind of phone in the fight choreography. They went through the trouble of hiring Bridgerton’s choreographer, Jack Murphy, for the dance sequences, but the fighting felt like a second thought. It could have been really cute to see Ruby do some “Crouching Tiger Hidden Dragon,” moves, but instead she clobbers her with a book. A bit underwhelming. Still a fun idea, though.

The Doctor and Rogue abscond to the garden where they are pursued by the Chuldur who reveal their numbers to be greater than anticipated. As baddies go, the Chuldur were little more than hand wringing monsters foaming at the mouth for a bit of mayhem, but I liked that about them. The way they speak to one another reminded me a lot of the Slitheen. The last time we saw Indira Varma in the Whoniverse, she was playing Suzie Costello, the best part of Torchwood. Here she chews scenery with a zest befitting her brilliant makeup. The only time that I felt they went a bit too far with the Chuldur is when they call what they’re doing “cosplaying,” as it felt a bit too on the nose. Otherwise, I loved the idea of evil birds going around and messing up planets all too satiate a dangerous appetite for excitement.

The Doctor sees Ruby acting as though a Chuldur has taken her form and it brings out the fury of the Time Lord. I wouldn’t be the first and I won’t be the last to point out the parallels between this and “The Family of Blood,” wherein the Doctor has some long term punishment in mind for the bad guys. Unfortunately, it also feels like a case of writers giving the Doctor weird morality again. Rogue wants to send the Chuldur to the incinerator, but the Doctor wants to send them to a dimension where they can live out the rest of their lives somewhere where they can’t hurt anyone. How is that any different from what the Weeping Angels do? It’s “Arachnids in the UK,” all over again. When the Doctor expresses happiness that the Chuldur will suffer for a long time, it begs the question- as compared to what? I’m fine with the Doctor losing his temper and going too far, but what about his plan actually changed other than his attitude about it? He was always planning on sending them into a dimension where they would suffer for 600 odd years. A line of dialogue or two could have fixed that.

The Chuldur’s big finale is a wedding between Barton and Ruby followed by a light bit of mass murder, but the Doctor has other plans. The Doctor’s objection to the marriage reminded me a lot of Tom Baker. I could easily hear Tom saying that line about it being hard to hear things through those heavy doors. Gatwa has that bizarre alien charm that feels correct. However, neither the Chuldur or the Doctor know the entire story as neither side knows Ruby is still Ruby. So when the Doctor traps the Chuldur in the triform transporter, he’s also dooming Ruby to the same fate.

I’ve seen some confusion as to how the transporter actually works, but I think I can piece together enough to understand it. They had calibrated the transporter to trap up to six humanoids. When Ruby is first trapped, there are five humanoids in the trap. Rogue throws Emily into the trap bringing the count up to six. We’ve established that the Doctor was able to throw his psychic paper from inside the trap, so things can leave its field. My thinking is that as Rogue pushes Ruby out from the field, he overloads it with seven humanoids giving Ruby just enough give to fall out of the trap. What got a bit confusing is why didn’t Ruby just step out of her shoes? If you can throw psychic paper, then it’s not trapped by the field. Therefore, her shoes would be the only thing molecularly bonded to the field. They could even say the shapeshifters can’t step out of their shoes because they’re actually part of their bodies. But then we couldn't get the big sacrifice at the end.

The aspect of this that I found harder to follow was why Rogue would sacrifice himself in the first place. Sure he and the Doctor have chemistry and there could be a romance brewing, but he barely knows the guy. Perhaps he couldn’t stomach the idea of watching what happened to him happen to someone else. It was a chance to stop the sort of thing he was previously powerless to prevent. I could buy that well enough, but it barely felt earned. However, it fits the tone of the rest of the episode which was one of over the top romance and drama, so I digress. Around here, fun is king and fun I had. It didn’t matter that I didn’t fully understand people’s motivations. There’s plenty of time for that in the future.

The episode ends with the Doctor sending Rogues ship to orbit the moon until it can be retrieved again (or until the moon hatches like an egg, whichever comes first). He wants to move on, but Ruby won't let him until he takes a moment to feel his feelings. This is classic Doctor/companion stuff. The Doctor has always benefited from having humans around and I am glad they took a moment to reestablish that. The Doctor pulls out Rogue's ring from the proposal and slides it onto his pinky finger. Fans of Amy and Rory will recall that rings can be used to find lost lovers, so there's a seed of hope there. It was a fitting end to an emotional and exciting episode. I got to watch the Doctor and Ruby do Regency Era dances to covers of Lady Gaga and Billie Eilish. I got to see Indira Varma hunt people while dressed as a bird. This wasn’t just my favourite episode of the season, it may be one of my favourite episodes ever.

________________________________________

Before I go, I wanted to apologise for how long this article took me to write. I’ve been dealing with some pretty heavy depression as of late, and it’s been hard to write these last couple of reviews. Even though I enjoyed both episodes quite a bit, it’s been a struggle. Despite episodes dropping at midnight on Saturday now, I don’t usually get around to writing until Sunday or Monday. But I didn’t get any good work done on this article until Monday evening. These articles are actually very therapeutic for me. It feels like a lifeline to the outside world. You may not think it, but I read every comment and every hashtag. I appreciate them all. Thank you for taking the time to read my stuff. It means a lot.

#Doctor Who#Rogue#Briony Redman#Kate Herron#Ncuti Gatwa#Fifteenth Doctor#Ruby Sunday#Millie Gibson#Jonathan Groff#Indira Varma#The Duchess#Chuldur#Regency Era#TARDIS#BBC#Season 1#Russell T Davies#RTD#RTD2#review#timeagainreviews

42 notes

·

View notes

Note

hi kitty!!! just wanna share a fun fact with you! did you know that peruere might be a corrupted spelling of perweur/perwyr, a welsh name that comes from perweur, one of the three lively maidens of britains in the welsh triad? not only are they pronounced the same way, both clervie and crucabena's names are french versions of names of characters from welsh mythology so it makes sense that perrie's name also comes from welsh mythology. in fact, clervie's name (as creirwy) is also mentioned the welsh triad as one of the three beautiful maidens!

all this time we were thinking arlecchino is french, but in actuality arle's welsh. GLORY TO WALES!!! and nothing for the french

WE HATE THE FRENCH (kidding😊)

this is very cool!! i did not know the origins of the names, so thank you for sharing ♡♡

now to connect the lore....

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

A cold winter, an old poem, and Mabon ap Modron

Short is the day; let your counsel be accomplished.

(Image source at the end)

Mabon is a figure of medieval Welsh folklore with a relatively minor (if distinctly supernatural) role in the early Arthurian tale Culhwch ac Olwen; a hunter who must be released from a magical prison. Unlike a lot of figures floated as euhemerised deities on pretty questionable grounds, his connection to the god Maponos, worshipped in Britain and Gaul in the Roman era, is fairly sound.

Recently I've been reading Jenny Rowland's Early Welsh Saga Poetry (bear with me, this will all come together), which I was led to by my interest in the 6th-century north-Brittonic king Urien Rheged and the stories that sprung up around him and related figures (his bard the celebrated Taliesin, and his son Owain, later adapted into the Yvain of continental Arthuriana). It includes an early medieval poem called Llym Awel, which immediately struck a chord with me.

It begins with a description of the harshness of winter, then transitions into either a dialogue debating bravery/foolishness versus caution/cowardice, or (I favour this interpretation) a monologue in which the narrator debates this within himself. In the final section, the context is revealed; the narrator has a dialogue with his guide through this frozen country, the wise Pelis, who encourages him and their band to continue in order to rescue Owain son of Urien from captivity.

(There then follow several more stanzas which seems to be a totally separate poem--Llywarch Hen, a different figure with his own saga-cycle, laments the death of his son. The traditional interpretation was that all this was a single poem, the narrator of the first part was Llywarch's son, and this shift represented a 'flash forward' to after the expedition ended poorly. Rowland points out various inconsistencies that point to this whole section being a different poem altogether, motivated by a mistaken interpolation of an earlier stanza with names from the Llywarch cycle)

Where this comes back to my introduction is the book also theorises that the story the poem is telling was originally about Mabon, not Owain. Rowland points to several instances where the two were conflated; from early poetry in the Book of Taliesin to the 'Welsh Triads' (lists of things/people/ideas bards used as aids to remembering legends) to much later folklore. As mentioned, one of the only stories we have about Mabon centres around his role as an "Exalted Prisoner" (as the Triads put it) whose release bears special significance, while no other such story survives about Owain.

This is obviously all conjectural, but I feel there's even another angle of support for the idea the book doesn't consider. The Romano-British/Gallo-Roman Maponos was very consistently equated with Apollo, god of the sun, in inscriptions (most of which show worship located in the same area of Owain's later kingdom of Rheged, which could support the possibility of folklore getting mixed together). Certainly identification with a god who appears as idealised beautiful youth would fit his name--"Mabon son of Modron/Maponos son of Matrona" is basically "Young Son the son of Great Mother". This could be all there was to the connection; Roman syncretism wasn't always 1:1. But it's entirely possible both figures shared the spectrum of youth-renewal-sun associations, or that Maponos originally didn't but picked these up over centuries of being equated with Apollo.

Whatever the case (and with emphasis that this is not sound enough to be considered anything like scholarship, just an interesting "what-if"), if Apollini Mapono was associated with the sun as well as youth, wouldn't it make perfect sense for the story of journeying to release him from captivity to have a winter setting? The winter is harsh, but if the sun can be set free, warmer times will come again.

(I'm a little hesitant in writing this, because "seeing sun-gods everywhere" was a bit of a bad habit of 19th-century scholars whose work is now disproven, especially in Celtic studies, and the internet loves to let comparative mythology run wild with vague connections, but I think the case is reasonable here)

I'll put below Rowland's translation of the poem, with the Llywarch stanzas removed (so something like its 'early' form):

Sharp is the wind, bare the hill; it is difficult to obtain shelter. The ford is spoiled; the lake freezes: a man can stand on a single reed.

Wave upon wave covers the edge of the land; very loud are the wails (of the wind) against the slope of the upland summits - one can hardly stand up outside.

Cold is the bed of the lake before the stormy wind of winter. Brittle are the reeds; broken the stalks; blustering is the wind; the woods are bare.

Cold is the bed of the fish in the shadow of ice; lean the stag; bearded the stalks; short the afternoon; the trees are bent.

It snows; white is its surface. Warriors do not go on their expeditions. The lakes are cold; their colour is without warmth.

It snows; hoarfrost is white. Idle is a shield on the shoulder of the old. The wind is very great; it freezes the grass.

Snow falls on top of ice; wind sweeps the top of the thick woods. Fine is a shield on the shoulder of the brave.

Snow falls; it covers the valley. Warriors rush to battle. I do not go; an injury does not allow me.

Snow falls on the side of the hill. The steed is a prisoner; cattle are lean. It is not the nature of a summer day today.

Snow falls; white the slope of the mountain. Bare the timbers of a ship on the sea. A coward nurtures many counsels.

Gold handles on drinking horns; drinking horns around the company; cold the paths; bright the sky. The afternoon is short; the tops of the trees are bent.

Bees are in shelter; weak the cries of the birds. The day is harsh; . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . White-cloaked the ridge of the hill; red the dawn.

Bees are in shelter; cold the covering of the ford. Ice forms when it will. Despite all evading, death will come.

Bees are in captivity; green-coloured the sea; withered the stalks; hard the hillside. Cold and harsh is the world today.

Bees are in shelter against the wetness of winter; ?. …; hollow the cowparsley. An ill possession is cowardice in a warrior.

Long is the night; bare the moor; grey the hill; silver-grey the shore; the seagull is in sea spray. Rough the seas; there will be rain today.

Dry is the wind; wet the path; ?….. the valley; cold the growth; lean the stag. There is a flood in the river. There will be fine weather.

There is bad weather on the mountain; rivers are in strife. Flood wets the lowland of homesteads. ? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

The stooped stag seeks the head of a sheltered valley. Ice breaks; the regions are bare. A brave warrior can escape from many a battle.

The thrush of the speckled breast, the speckle-breasted thrush. The edge of a bank breaks against the hoof of a lean, stooping, bowed stag. Very high is the loud-wailing wind: scarcely, it is true, can one stand outside.

The first day of winter; brown and very dark are the tips of the heather; the sea wave is very foamy. Short is the day; let your counsel be accomplished.

Under the shelter of a shield on a spirited steed with brave, dauntless warriors the night is fine to attack the enemy.

Strong the wind; bare the woods; withered the stalks; lively the stag. Faithful Pelis, what land is this?

Though it should snow up to the cruppers of Arfwl Melyn it would not cause fearful darkness to me; I could lead the host to Bryn Tyddwl.

Since you so easily find the ford and river crossing and so much snow falls, Pelis, how are you (so) skilled?

Attacking the country of ?. does not cause me anxiety in Britain tonight, following Owain on a white horse.

Before bearing arms and taking up your shield, defender of the host of Cynwyd, Pelis, in what country were you raised?

The one whom God deliver from the too-great bond of prison, the type of lord whose spear is red: it is Owain Rheged who raised me.

Since a lord has gone into Rhodwydd Iwerydd, oh warband, do not flee. After mead do not wish for disgrace.

We had a major cold snap here recently, and having spent day after day going "WHY is it so COLD" every time I emerged from a pile of blankets and hot water bottles--and even having come through it, I'm sure we'll be right back there in the coming months--needless to say, a lot of this stuff resonated.

Rowland discusses some ambiguous lines that suggest the narrator is ultimately overcoming their doubts to boldly press on throughout the poem, even before Pelis chimes in:

A coward nurtures many counsels. i.e. "Deliberating this isn't getting anything done"

Despite all evading, death will come. i.e. "When danger approaches, hiding won't help."

A brave warrior can escape from many a battle. i.e. "Conversely, you can survive by meeting that danger head-on."

There will be fine weather. i.e. "Amid all this description of how cold and miserable it is now, a reminder that warmer times will come again"

Short is the day; let your counsel be accomplished. i.e. "Let's hurry up and act decisively."

-with brave, dauntless warriors the night is fine to attack the enemy. i.e. "Fighting during night (much less during winter) is rarely done in this era because it's hard and it sucks, but we're built different, we'll simply handle it."

In my opinion, many of these would take on an interesting dimension with the above interpretation vis a vis Mabon; it's best to press on through the cold and difficult conditions, because success (the release of the sun from frozen "imprisonment"--a metaphor the poem uses multiple times with animals) will bring an end to those conditions. If the sun can be released, there will be fine weather.

Now, I'm not saying there was some "lost original version" of this poem itself. It's a medieval poem about Owain, and quite a moving one in that context; frankly the addition of the Llywarch stanzas, even if they change the meaning, might make it more moving still. But I do agree it's a distinct possibility that the story the poem was retelling was originally one about Mabon, and I would add that it has perhaps gone unappreciated that this could contain otherwise unattested details to the story of the Exalted Prisoner, and just why it was so important to set Maponos Apollo free.

And on a personal level, especially these past couple weeks while I shiver and glance at the mounting ice outside, I can't help be touched by the imagery of summoning up the courage to press on through the cold to find this buried god.

- - -

For further reading, Rachel Bromwich's Trioedd Ynys Prydein: The Triads of the Island of Britain, as well as going through the Triads themselves, contain an encyclopedia of every figure mentioned in them (so near enough every figure of medieval Welsh legend, literature and folklore, including all the ones mentioned here), and runs down basically everything we know about each one. An invaluable resource.

Image at the top: Winter in Gloucester, site of Mabon's imprisonment in Culhwch ac Olwen. Publicly downloadable. Link to the photographer's gallery:

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

(From The Welsh Triads, translated and edited by Rachel Bromwich)

Man, the concept of Wizard-King Uther Pendragon...

Like, the idea Uther never really needed Merlin for anything magical - he would've just it done by himself.

Also, the implication that Uther is very magically powerful. The other people listed in this triad are nothing to scoff at: Math and Gwydion are the two supreme magician characters of the Mabinogi. Gwythelyn/Rudlwm the Dwarf is unknown, but his protege, Coll ap Collfrewy, is a powerful swineherd who owned Henwen, the magic pig that gave to a bunch of things, including the dreaded monster Cath Palug.

Neither Merlin nor Blaiddud (the Necromancer King from Historia Regum Britanniae and father of King Leir) are included here. AFAIK, Merlin's magical deeds are seemingly never lauded by the surviving Welsh poetIc material.

#uther pendragon#menw ap teirgwaedd#the welsh triads#welsh mythology#merlin#the three great enchantments of the island of britain#arthuriana#arthurian legends#arthurian mythology#the mabinogion

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

A rant might delete

honestly I find it funny when Arthurian retellings try to claim historical accuracy and seriousness by calling everyone by their welsh names and setting the tale in sub Roman Britain and having no magic. but then proceeded to write modred as the product of incest, evil rapist morgause good guy Arthur vilifying Lancelot and Guinevere and much more . What’s odd they tended to be inspired by previous retellings (like 🤢🤢🤮once and future king or mists of Avalon ) or continental romances (there is no Lancelot in the og early medieval welsh sources he’s purely French ) but they rarely touch any of the actual welsh sources I assure you Mr and Mrs retelling author never read elis gruffyd,Book of Taliesin, The Black Book of Carmarthen,The Mabinogion and the welsh triads. TLDR I’m just tired of these retelling authors trying to claim historical accuracy whilst not putting any effort of actual research and trying to appear more serious by being gritty and edgy and continuing to perpetrate stereotypes of the gloomy and backward dark ages

9 notes

·

View notes

Note

If I wanted to get really into medieval welsh literature instead of just reading everything in our beloved Hergest duo, do you have any recommendations on where to begin?

hi! sorry it took me so long to answer this but hopefully the length of the answer means it's worth the wait. by "our beloved hergest duo" i'm assuming you mean the white book of rhydderch and the red book of hergest, and more specifically the texts collected as the mabinogion from those two manuscripts - if i'm wrong let me know. i'm also assuming that you mainly want to read in english translation, at least to start with.

there is a LOT of medieval welsh literature out there beyond the mabinogion but a lot of it is harder to access. this is a rough menu of options with my honest opinions about how easy it is to get at these things:

the triads of the island of britain (trioedd ynys prydein), aka a big long list of People And Things From Welsh Tradition (Some Possibly Made Up). for this you want rachel bromwich's edition and translation: there are four different editions of this and all of them are expensive (and three of them are out of print). i recommend keeping an eye out on secondhand book websites for the 2nd edition (1978) or the 4th (2014), or bugging your library to see if they have, or will buy, either of these. if you're currently at uni you may be able to get access to an electronic version of the 4th edition.

material about merlin. maybe start with geoffrey of monmouth's latin vita merlini - this is less a reflection of welsh tradition and more an extremely lengthy riff on it, but still very interesting. a new translation of it can be found here! medieval merlin material in welsh is basically all prophetic poetry, mostly from the black book of carmarthen. at the moment, the best place to find translations of this is in the romance of merlin, ed. peter goodrich (1990) - again i recommend looking out for a secondhand copy or talking to your library. hopefully the myrddin project at cardiff will soon have fresh editions and translations for us available online! (in the meantime, here's their twitter.) there's also armes prydein vawr, a somewhat different type of prophecy poem also associated with merlin/myrddin and generally dated to the 10th century, which you can find on archive.org here.

material associated with taliesin. this comes in many shapes and sizes. first of all, there's praise poetry attributed to taliesin and addressed to the 6th-century king urien of rheged: this is mostly translated in the two clancy anthologies i'm going to cite further down, but if you want the welsh text, the best place to find it is probably in ifor williams' edition (translated into english as the poems of taliesin by j. e. caerwyn williams, available from the dublin institute for advanced studies). second of all, there's All The Other Poetry Attributed To Taliesin: for this you want marged haycock's legendary poems from the book of taliesin and prophecies from the book of taliesin. again with these i recommend the secondhand or library approach. THIRD of all, there's a relatively late folktale about taliesin (this is where ceridwen and gwion bach come in): this you can find translated in patrick k. ford's the mabinogi (which it looks like you can get as a kindle or paperback comparatively cheap).

y gododdin, the massive poetic text attributed to aneirin about A Lot Of Dead Dudes In Southern Scotland. this is a tough one to get to grips with, i'm not gonna lie. if you want to get at the welsh text, the massive modern welsh edition by ifor williams (canu aneirin) is still the best there is, but he reorders the stanzas of the poem from the manuscript pretty radically. (to see the stanzas in order, look for daniel huws' facsimile edition of the book of aneirin - or, depending on how well you read medieval welsh handwriting, check out the manuscript itself.) for translations, i recommend joseph p. clancy's, which has multiple versions floating around - there's one in the triumph tree (ed. thomas owen clancy) and a slightly less full one in medieval welsh poems (joseph clancy's big anthology, now out of print). this is the most poetic while still being largely accurate, but if you're concerned about academic levels of accuracy, then i recommend balancing clancy out with kenneth jackson's the gododdin: the oldest scottish poem, which has the advantage of being designed to be used alongside ifor williams. FOR ALL OF THESE you'll need to hit up secondhand booksellers or libraries.

early welsh englyn poetry: by this i mean poetry in englyn metre about historic figures and landscapes. as academic sources/translations, if you can get your hands on them, i recommend jenny rowland's early welsh saga poetry (1990) and patrick sims-williams' new englynion y beddau (2023), but both of these are massive and expensive. a more approachable way to get at this material may be rowland's a selection of early welsh saga poems, which is intended more for classroom use - this you can get for relatively cheap as a paperback. you might also want to check out kenneth jackson's studies in early celtic nature poetry (dated, but i think he translates some of the less-studied englyn poetry in there: again, check with secondhand booksellers) and nicolas jacobs' early welsh gnomic and nature poetry (cheaper and easier to get, but untranslated, though he gives a useful glossary so you can attempt it yourself).

additional arthurian material. this is scattered across various places and manuscripts, but some good places to learn about it, if not necessarily read it, are o. j. padel's arthur in medieval welsh literature (2013, heavily recommended, you can get it cheap as a paperback); bromwich et al's the arthur of the welsh (1991), which iirc includes patrick sims-williams' translation of my beloved arthurian poem pa gur; and the new and exciting arthur in the celtic languages, ed. ceridwen lloyd-morgan and erich poppe (2019), which is going to give you a BIG and comprehensive overview of every text arthur has ever shown up in in welsh. for the last two you definitely want to go secondhand or through a library. EDITED TO ADD: [LOUD BUZZER NOISE] I DID NOT KNOW ABOUT NERYS ANN JONES' ARTHUR IN EARLY WELSH POETRY which came out in 2019! go buy it it's a £15 paperback! an absolute steal for what you get!

high and late medieval poetry of praise, lament and love: the bread and butter of the professional poet. these can be found in various places. for the gogynfeirdd, the high medieval poets, the medieval welsh texts (+ modern welsh paraphrases) can be found in the absolutely massive series cyfres beirdd y tywysogion, but this is not something to attempt to get without a powerful library on your side. the late medieval poetry, on the other hand, is edited in cyfres beirdd yr uchelwyr and can be found online here - which was news to me! much of this material has never been translated into english. for a good selection of translations of some of the best stuff, i really recommend joseph p. clancy's medieval welsh poems (find a secondhand copy or get your library to do it for you), and/or tony conran's welsh verse. a couple of good selections of the later medieval poetry are: the poetry of dafydd ap gwilym, ALL of which is available online in translation here; loomis and johnston's medieval welsh poems: an anthology; and dafydd johnston's galar y beirdd: poets' grief, which specifically collects poets' laments for their dead children.

RELIGIOUS MATERIAL, of which there is a shit-ton. my recommendations are definitely going to be missing some stuff (e.g. soul-and-body dialogues, descriptions of purgatory, etc) but here's what i've got. for material to do with welsh saints, i recommend this website, where you can find translations of a lot of the latin prose lives of saints and quite a few welsh poems about saints as well - and if you look at the bottom you'll see it lists a few more books you might want to look into. if you want an even fuller look at welsh saints' latin lives, albeit dated, see if you can get your hands on a secondhand/library copy of wade-evans' vitae sanctorum britanniae (1944). if you like genealogies, barry lewis i believe has just put out an edition and study of bonedd y saint, the genealogies of the welsh saints, available from the dublin institute for advanced studies (though it's not the cheapest thing out there).* there is also a lot of general religious poetry, which you can find edited in marged haycock's blodeugerdd barddas o ganu crefyddol cynnar (1994) and translated in mckenna's the medieval welsh religious lyric (1991).

*i should also say that if you're interested in medieval welsh genealogies in general, you want ben guy's medieval welsh genealogy - this is very technical and probably expensive but if you really need to know who's related to who in the welsh historical imagination, it's a great resource.