#this is not real life it’s film there are motifs and symbolism

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Pointing out cinematography on this app is so refreshing, no one says that it doesn’t matter even though CINEMAtography literally makes CINEMA

#people on other apps compared mise en set to real life#it upset me#FUCK ITS CALLED MISE EN SCENE???#bro I hate my memory#it’s sucks balls#I can remember what things are but can’t remember their names#anyways my point still stands#mise en scene is ON PURPOSE#this is not real life it’s film there are motifs and symbolism#film#mise en scène#motifs#symbolism

0 notes

Text

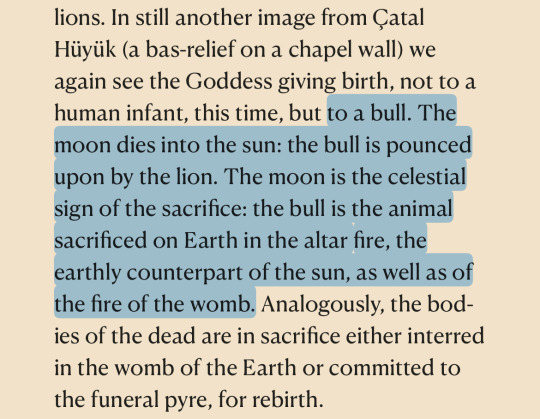

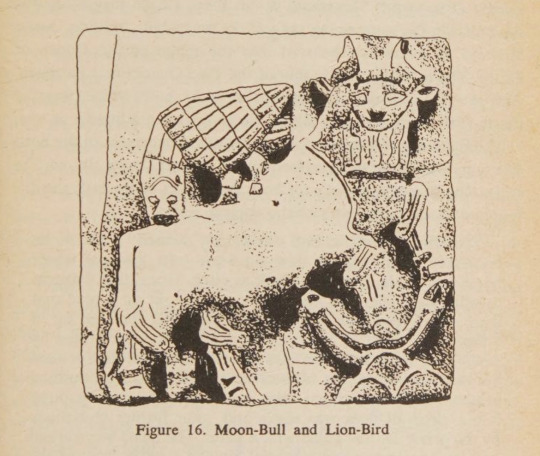

🌘 THE ECLIPSE a UNION of OPPOSITES 🌒

an analysis of the mythic motifs in dune part two through the lens of mythologist joseph campbell, and some predictions for dune messiah

• Divine Couple

• Death and Rebirth

• Redemption Through Divine Union

• House of Atreus

• Lunar-Masculine / Solar-Feminine

• Goddesses

THE ECLIPSE

This motif has been connected to Dune since the first film’s promo, especially with the concluding track of Dark Side of the Moon accompanying the initial trailer. Some fans believed this theme had been dropped as it wasn’t very present in the first film. However the eclipse continued throughout the promo of the second film. This was because Part Two is where the real pay off is, already in the first 10 minutes.

This concept is intrinsic to Denis Villeneuve’s adaptation. Since the first film I have been saying that Dune embraces the Lunar-Masculine (Paul) and Solar-Feminine (Chani). However beyond just that, Dune: Part Two showcases multiple pairings of the lunar-solar dynamic.

But before we jump into that, let’s establish the meaning of an eclipses in general mythology. Typically they are a symbol of death and renewal. Common interpretations have a beast devouring the sun, or a celestial couple evading or pursuing one another. These interpretations are consistent over and again in Dune.

What we will see, is that the greater Imperium holds a Solar-Masculine identity, but when it comes to Arrakis there is a distinct shift to the Solar-Feminine archetype.

PAUL as the MOON

There are an innumerable amount of connections. Bull motifs are reoccurring throughout the first film, where he grew up on a water world. After all, the moon is associated with the tides. He takes the name Muad’Dib, and one of the moons of Arrakis has the icon of a Muad’Dib aka Desert Mouse visible on its surface. And ultimately, Paul experiences rebirth in Part Two.

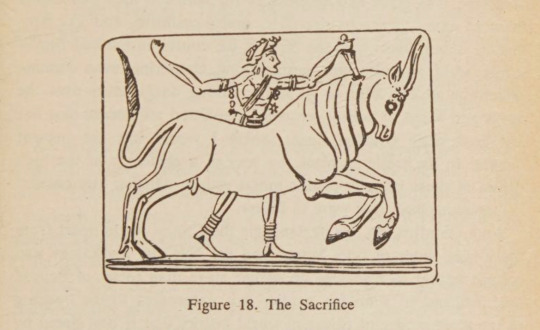

The bull is a figure of sacrifice which aligns very well with the lineage of House Atreides which can be traced back to the House of Atreus and it’s curse of familial murder, betrayal and symbolic consumption. Sacrifice of the children in each new generation.

IRULAN and the GOLDEN LION THRONE

Starting here is a good place, because it shows the transition of the Solar-Masculine of the wider Imperium toward the Solar-Feminine of Arrakis. Irulan Corrino of House Corrino is the daughter of Emperor Shaddam who sits on the Golden Lion Throne. His reign is coming to a close as Paul rises on Arrakis, and with no male heirs Irulan his eldest is the successor destined for marriage. In this way Irulan becomes the embodiment of the Lion Throne, and her determination in Dune Messiah to produce Paul’s heir becomes clear. That function of the Queen Mother and how that feeds back into the Solar-Masculine as the King becomes tied to the lion and the throne once more.

In particular I would say her story is best reflected in the myth of the goddess Cybele who falls for Attis and when he falls for a mortal girl Cybele plots betrayal. Something for which she later feels guilt and tries to make amends for (Children of Dune).

PAUL and JESSICA

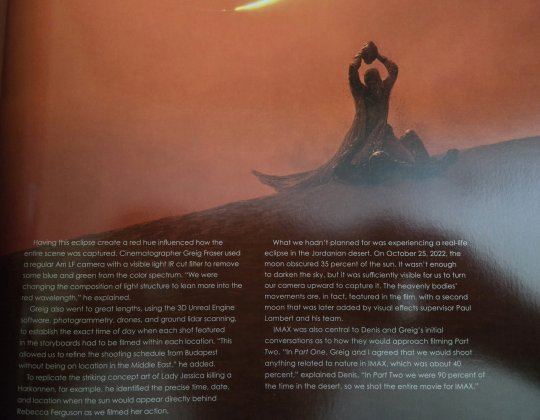

Their dynamic is incredibly complicated, but I think the opening of the film during the eclipse sums it up very well. You follow the path of the moon as it covers the sun, and as it meets its full coverage Paul is the one taking action in the fight against the Harkonnen. However as the moon passes by and the sun takes over again, Jessica emerges to save Paul’s life.

This was intentional by the filmmakers, as is revealed in the Art and Soul of Dune Part Two, DP Greig Fraser identified the exact time, date and location in order to shoot the sun as it appears directly behind Rebecca Ferguson.

Jessica represents the sun on Arrakis, and in this scene we see how the moon dies into the sun to be reborn in their dynamic. It also lines up with motifs of the sun goddess giving birth to the sacrificial bull. Sacrifice toward this death and rebirth.

What we see is the separation of mother and son that brings them back together in the same place. Paul takes the lead and rejects his mother’s influence, but she leads him toward the death and rebirth he must experience, and this brings them back to a common understanding.

This is also why having Jessica sit the Atreides “throne” in the finale instead of Paul (who did so in the book) makes mythic sense. Because again we return to the Solar-Feminine mother as the throne, and her son as king. But in a different context here then what Irulan aspires toward.

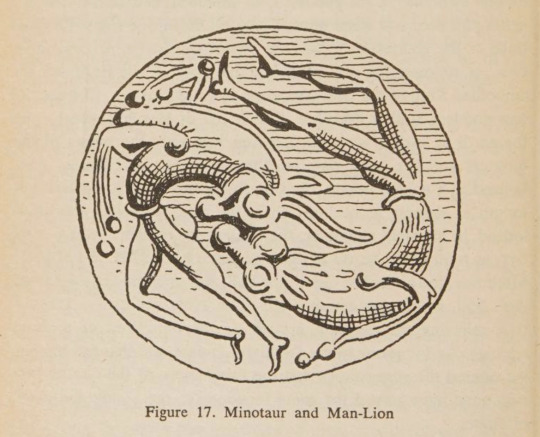

A SYMBOLIC UNION aka THE BULL SACRIFICE

The House Harkonnen family seal in the books is the griffin, which makes his introduction in a gladiator arena killing Atreides even more appropriate. Feyd’s birthday is also associated with a solar event. Because ultimately Feyd is the matador and Paul is the bull.

What works so fantastically about the dual, is how it is bathed in the sunlight. After all, the sun figure (day) is facing off against the moon (night) figure in this sequence. Plus the bull was the eventual demise of Paul’s grandfather who was a matador. This takes place at sunrise, and it’s a dual for the throne, where whoever is victorious inherits the Golden Lion Throne. The

Denis specially describes the dual as a symbolic union, and it works on multiple layers. This bull sacrifice, is in essence the quote from part one of “when you take a life you take your own” so Paul killing Feyd is penetration, intimacy, it is rebirth.

It is also reminiscent of how Campbell describes the sun-moon twins of Navajo myth:

The two, Sun-child and Water-child, antagonistic yet cooperative, represent a single cosmic force, polarized, split, and turned against itself in mutual portions. The life-supporting sap-power, mysterious in the lunar rhythm of its tides, growing and decaying at a time, counters and tempers the solar file of the zenith, life- desiccating it its brilliance, yet by whose heat all lives.

— Joseph Campbell's Commentary from "Where the Two Came to Their Father: A Navaho War Ceremonial" by Jeff King and Maud Oakes

DESERT SPRING TEARS and DIVINE UNION

There is a section in the Dune Encyclopedia that talks about the foundation of the Bene Gesserit beliefs. In particular the teachings of a certain ancestral memory personality, called Inanna (yes that is the name of the Sumerian goddess who was also in a divine union caught between life and death glad you asked) about the Kwisatz Haderach. It basically establishes that the entire premise of the Bene Gesserit and the Kwisatz Haderach is in essence the Divine Couple.

It specifies two mirrored dynamics the son saved/resurrected by the mother and the husband saved/resurrected by the wife. Inanna called them Au Set and Au Sar. The Kemet names for Isis and Osiris. The idea of the Bene Gesserit would have this as the mother of the KH, and the Corrino princess he would have married. But with things thrown off course, it represents outside their control.

In Dune, we see it between Paul and Chani. Like Isis who has the solar disc and Osiris who is tied to water and death, her lover has died and she is the one to revive him.

Furthermore the concept of mythical tears can be found in the goddess Freya (who arguably is compatible with sun-goddess motifs) who weeps when her husband Odin is lost to her.

But perhaps most compatible—the healing tears of a phoenix. A bird archetype similar to Isis as bird. This is where the yin-yang dynamic of Chani and Paul becomes most apparent, since the serpent is synonymous with the bull and therefore Paul who “makes peace with Shai-Hulud” encompasses the dragon (yang) as a complement to Chani’s phoenix (yin).

In the behind the scenes of Dune Part Two, the Maker Temple is said to be designed like the infinity symbol with the two circles (one of sand and one of water). Sand being death and water being life, but also the reverse. As the sandworm thrives in the sand but is drowned in the water. And Paul is stuck between life and death, literally laying between both pools, when Chani comes to resurrect him.

This film literally has three kisses. Their first kiss when Chani says she will show him the way of the Fremen, their second kiss on screen when she says he will never lose her before going South, and the third symbolic kiss of life.

This marriage/death is also foreshadowed in Paul’s visions in Part One when Chani kisses him and then stabs him. Which is where we return to Isis and Osiris because Paul’s death state (dying again as we established, after killing Feyd, similar in a way to Set and Osiris) is where we will eventually get the twins Leto II and Ghanima with Leto II being the Horus in this equation.

As the Pink Floyd lyrics say, the sun is eclipsed by the moon and this is captured in the heartbreak Chani feels over losing Paul and losing her people to the Lisan al Gaib. The Fremen way of life has been eclipsed and over taken by the Atreides and the Bene Gesserit. Here we see more of the concept of that beast devouring the sun from the beginning, verses the celestial couple dynamic.

Chani leaving the residency chamber is also reminiscent of certain myths like Amaterasu going into hiding, or the Inuit folktale about the sun goddess fleeing her moon god brother/lover who pursues her.

However the Dune Encyclopedia also talks about the concept of redemption (which is why in the film Mohiam asks Margot if Feyd is capable of redemption) of the “mate savior”. The Kwisatz Haderach. They would bring about a release from bondage through redemption and rebirth.

Which is relevant to the dynamic of Paul and Chani in Dune Messiah for Denis, because he has said Paul is going to be looking to save his soul in part three, and how Paul and Chani come back together won’t just be explained away off screen between films. It will be that continued cycle of rebirth, through redemptive love. Rebirth as a whole in Dune is worth its own discussion, since all the different Jungian descriptions of it can be found within this universe.

CONCLUSION

The eclipse, a lunar-solar dynamic representing the union of opposites, is very significant in Dune Part Two and sheds a lot of light onto what we can anticipate next in Dune Messiah, particularly in regards to the central romance between Paul and Chani and the changes Denis has made from book to screen.

#joseph campbell#dune part two#dune#dune 2#dune movie#dune 2024#divine union#mythic romance#mythology#eclipse#paul atreides#paul x chani#chani kynes#bene gesserit#goddesses#inanna#goddess#lunar masculine#solar feminine#house Atreus#curse of Atreus#redemption#timothée chalamet#zendaya#feyd rautha#austin butler#lady jessica#rebecca ferguson#florence pugh#irulan corrino

129 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cosplay the Classics: Natacha Rambova

My closet cosplay of Natacha Rambova’s signature look from the 1920s

It’s unbearably common for people who have written about Natacha Rambova to emphasize that her “real” name was “Winifred Hudnut.” In reality, Rambova had about a half dozen names she went by (or could have gone by). Natacha Rambova was the name she took when she began her working life as a teenager with Theodore Kosloff’s ballet company—hence the Russophone name. And, as Rambova was a person who first and foremost lived to work, sticking with her professional name seems true to her character, Slav or not. You see, the primary reason Rambova was (and is) subjected to this passive-aggressiveness is part of a lingering effort to delegitimize her and her work. Sometimes that takes the form of calling her Winifred Hudnut and sometimes “Mrs. Valentino.” While there are valid reasons to criticize Rambova and her work, the aspersions typically lobbed at her fully miss their mark because they’re motivated by the desire to belittle a woman who knew the value of her work and her art and had the necessary privilege to fight for it.

"Natacha Rambova seems to belong most to me, the individual I think I am, but of course, I wasn’t born that way."

—“Wedded and Parted” by Ruth Waterbury, Photoplay, December 1922

Collage of portraits of Rambova from the 1920s

READ ON below the JUMP!

To begin at the beginning, Rambova was born as Winifred “Wink” Shaughnessy in Utah in 1897. Her father, who was significantly older than her mother, was found lacking as a parent and a spouse, and the Shaughnessy’s divorced when Rambova was young. Her youth was spent bouncing between her mother’s home in San Francisco, boarding school in England, and her aunt’s villa in France. Early on Rambova discovered two of the great passions of her life, ballet and mythology. The latter became an enduring fascination that guided Rambova’s varied pursuits throughout her life.

At first, her family encouraged Rambova’s interest in ballet. However, around 1914, when Rambova was 17, the shady nature of Rambova’s relationship with Kosloff was discovered by her mother, who tried to have Kosloff deported. At the time, Kosloff was supporting a wife and child back in England while keeping house with Rambova and another of his dancers, Vera Fredova (who was also legally named Winifred and also a teenager btw). Mom called off the lawsuit, and for years Kosloff, Rambova, and Fredova ran the ballet company together.

The company relocated to Los Angeles where Kosloff entered into a contract with Cecil B. DeMille. The company would provide art and costume designs for DeMille’s films and Kosloff himself would appear in the films. While Kosloff’s name is found in the credits for most of these films, it’s now widely accepted that Rambova was doing most, if not all, of the research and design work.

Theodore Kosloff in his costume from The Woman God Forgot (1917) on the left with Rambova (who does not appear in the film)

In this creatively productive period, Rambova shifted her focus away from dance toward historical research and costume and set design as her primary endeavor. For DeMille, Rambova contributed designs for The Woman God Forgot (1917), Why Change Your Wife? (1920), Something to Think About (1920), and also designed the Cinderella fantasy sequence of Forbidden Fruit (1921).

from the Cinderella sequence of Forbidden Fruit [more gifs here]

The work caught the eye of Nazimova, who was still working at Metro at the time. Once Nazimova realized that Rambova was the one doing the work, she engaged her directly to work on her now lost film Billions (1920). Rambova would receive on-screen credit for her art direction on Nazimova’s final film for Metro, the deco-bonanza Camille (1921).

from Camille [more gifs here]

Camille features designs verging on the bizarre, using circles and half-circles as a consistent symbolic motif throughout the film. One of my personal favorite touches however, is the sequence taking place at Armand’s country cottage. Where the Paris sets are oversized and characterized by rounded edges, the cottage is excessively square and feels almost claustrophobic. At this point in the story, Marguerite is conflicted, she feels happier and freer than ever before in her love with Armand, but is also haunted by the notion that she’s dooming him given her past and her illness. The interior of the cottage feels more artificial because of its realism, almost like a doll house, in comparison to the more heavily designed Paris settings. This highlights the feeling in Marguerite that she’s just playing pretend at a happy, heteronormative fantasy.

country house setting from Camille

Influenced by the highly stylized visuals of ballet but also preoccupied with historical research and symbology, Rambova’s designs stand out from anything else produced in this period, especially in the US. The more I study her designs and think about how young she was when she created them, the more impressed I am by them. Faced with challenging assignments, Rambova balanced accuracy and perceived authenticity with her penchant for larger-than-life symbolism. On top of all that, they photograph beautifully! Being able to create interesting and appropriate costume and set designs with a demonstrated understanding of how they would register on film is a sophisticated skill set which Rambova deserves significant credit for.

When Nazimova went independent following Camille, she brought Rambova with her. The first two projects Rambova would work on for Nazimova’s company were A Doll’s House (now a lost film, which I profiled on my Lost, but Not Forgotten series) and Salomé (1922). The latter has become regarded as Nazimova’s magnum opus on film and often referred to as America’s first art film. For Salomé, Rambova translated illustrations made by Aubrey Beardsley into three-dimensional sets and costumes and character designs for film. If you’ve seen Beardsley’s illustrations and you’ve seen the film, you know this was no simple task and that Rambova did a phenomenal job of re-working the illustrations into wearable costumes and weaving elements of Beardsley’s illustrations into the set design.

from Salomé [more gifs here]

Taking a second to emphasize Rambova’s range, her work on Why Change Your Wife?, Something to Think About, and A Doll’s House (which we can only judge by surviving stills) are contemporary settings with more realistic, grounded set and costume designs. Rambova executes the designs for these films with just as much skill, although as she admitted herself, with less gusto because they didn’t scratch the historical-research/symbology itch.

production still from A Doll’s House

It was in this same period of creative growth that Rambova split from Kosloff (and he shot her in the leg on the way out) and she started seeing her future husband, Rudolph Valentino. Valentino, however, was still legally married to another woman. This would lead to significant trouble for the couple in the first few years of their relationship.

Perhaps too much time has been spent picking apart the nature of the Valentino-Rambova pairing—most of it spent trying to characterize her as a Svengali type and Valentino as too immature or unintelligent to have any opinions of his own. Now, having read most of what Rambova has written about Valentino, both before and after their divorce, she often takes a paternalistic attitude toward Valentino, but one tempered by real affection. And, given how close Valentino became with her family (and remained close after the divorce, even leaving a significant part of his estate to her aunt), to doubt the legitimacy of their partnership feels willfully disingenuous. Valentino shared Rambova’s desires to elevate the artistic qualities of film, oftentimes beyond their means. Together they crafted the romantic idol of Valentino. Together they challenged the studios for underpaying him.

“Some producers find an unusual personality. They use up thousands of dollars to exploit it. They put that personality into a picture and the picture goes over and makes a million. Then, instead of letting the actor who does fine work go on doing it, they give him cheap material, cheap sets, cheap casts, cheap everything. The idea then is to make just as much money from that personality as possible with the least outlay. “Isn’t it short-sighted? Isn’t it unwise? Yet they do it again and again. But they can’t keep it up forever. The fans are beginning to wake up. They refuse to take second rate products even when a big personality is exploited. They are doing the one thing that will affect the producer—when poor pictures are offered them, they are staying home.”

—from “Wedded and Parted” by Ruth Waterbury, Photoplay, December 1922

Something I mentioned in the last installment of “Lost, but Not Forgotten” was that in this period, a number of film artists in Hollywood were recognizing the true value of their work and going independent of the emergent studio system. Studio heads saw no problem in curtailing the creative freedom of their artists to further pad their overflowing wallets. For the founders of United Artists, the system was usually able to be bent in their favor, with their films getting wide releases with decent promotion budgets. For a number of other independent artists, the road was rockier as distributors and exhibitors were reluctant to offend the increasingly powerful studios. Nazimova was one of those who eventually ran out of funds to produce their own work. Valentino’s star rose precipitously after The Sheik (1921) and Blood and Sand (1922) was a massive box-office hit, but Valentino’s salary did not match that bankability. This financial dispute, complicated by negative press around his relationship with Rambova, left Valentino out of work in film for a year. In turn, Valentino and Rambova went on a dancing tour of the country, which raised her profile as a public figure while bolstering his star image despite not appearing in any new films.

Valentino and Rambova in a promotional photo for their dance tour

Unfortunately, crossing the studio system as they did resulted in a coordinated campaign to take them down a notch. Reading film magazines from the period will give you whiplash. Many of these magazines had established relationships with studios and ran news items in keeping with whatever narratives the studios wished to push. However, the stars and their managers (if they had them) had their own relationships with the magazines. So, occasionally, you’ll find items deriding Rambova as some kind of artsy-fartsy manipulative phony and then a profile piece of her or Valentino that’s sympathetic to their business woes. This is the period where the narrative emerges of Rambova as a calculating climber, using Valentino to build her own career. This talking point is often repeated today, despite the fact that Rambova had already been working on big productions for DeMille and Nazimova for years before meeting Valentino. While Rambova was certainly a key figure in developing Valentino’s star image, the plain facts make it apparent that they were working as a team—hardly abnormal. Unfortunately, neither member of said team had much in the way of business sense.

As I mentioned earlier, Rambova fashioned her life around her work. Something I didn’t mention earlier is that she was an heiress. At this point in her life, Rambova was determined to live off her own labour and not touch her inheritance. When they were battling the studios, the couple continued to not touch Rambova’s inheritance. And, both desperate to return to filmmaking, they were subject to the studio’s will. While their split is often framed as Rambova abandoning Valentino when she was denied the ability to control his career, a slightly different scenario emerges upon closer inspection. Both Valentino and Rambova were highly dedicated to their work and their work was intertwined with their relationship, a similar dynamic to Rambova’s relationship with Kosloff and later with her second husband Álvaro de Urzáiz, with whom she restored villas. With Urzáiz, their relationship degraded when they no longer had a shared project to work on. (In this case due to the Spanish Civil War.) It’s neither sensational nor romantic, but following Valentino’s reconciliation with Hollywood, after a few films, the pair was intentionally separated creatively. (This was at least partly due to the machinations of their new business manager, George Ullman, who we now know was manipulating Valentino’s finances after litigation regarding the disposition of Valentino’s estate.)

“What I desire personally is simply to be known for the work which I have always done, and that has brought me a reputation entirely independent of my marriage.”

—“Natacha Rambova Emerges” by Edwin Schallert, Picture Play Magazine, August 1925

Rambova worked on one film independently from Valentino before their divorce, What Price Beauty? (1925), starring mutual friend (for the moment) Nita Naldi. The film is now lost and its production and release seems awfully sus, so I hope to cover that for “Lost, but Not Forgotten” soon. Regardless of the film’s success or failure, the whole endeavor soured Rambova on Hollywood.

Nita Naldi in a promotional photo from What Price Beauty?

In her book about her life with Valentino, Rambova opined:

“Hollywood—all the joys of the petty community life of ‘Main Street’ with an additional coating of gold dust thrown in for good measure!… it is merely an imitation gilded hell of a make-believe realm. Nothing but sham—sham—and more sham. “Hollywood—one continuous struggle of nobodies to become somebodies, all pretending to be what they are not.”

Through their divorce and Valentino’s untimely death the year following, Rambova never stopped working. Rambova operated boutiques selling her original designs in New York and then in France. Around this same time Rambova also got more deeply involved in spiritualism. In an odd move, she published Rudy with the final third of the book “dictated” by Valentino’s spirit. I won’t say that I don’t find that pretty distasteful, but having read the book, it reveals two key things: Rambova’s genuine affection for Valentino, patronizing as it may be, and a sincere belief in the spiritualism movement that she and her mother had been drawn into. There have been critics who have framed the book as some sort of cash-in or vengeful act against Valentino for excluding her from his will, but the facts do not support that. Rambova, to reiterate, was an heiress who did not need to work for a living. She also states directly that it is Rambova’s spiritual leader who encouraged her to publish the book as a way to promote spiritualism. That’s not necessarily any better than the false narrative, but the truth has value (and is more interesting in this case!)

In the 1930s, Rambova relocated to Spain where she finally began using that inheritance to develop rental properties on Mallorca with her aristocrat husband. If you know anything about 20th century European history, you may know what happened next. Urzáiz joined the fascists in the Spanish Civil War, and despite her abiding fear of Communists, Rambova stuck around in Spain for as long as she could before fleeing to France. Of course, it wasn’t long before the Nazi Germany invaded France, so Rambova relocated back to the United States.

During her time abroad, Rambova’s preoccupation with symbology was reignited by a trip to Egypt. This sparked the next big passion of her life, which she would pursue for over two decades: Egyptology.

Rambova in Egypt

Rambova became a writer, researcher, and lecturer on symbolism and cosmology in Ancient Egypt (as well as spiritualism). Much of Rambova’s work was done in collaboration with Alexandre Piankoff and the French Institute for Oriental Archaeology in Cairo (IFAO). With various grants, Rambova travelled to Egypt to document important sites, via photography and illustration. Rambova also used much of her inheritance to source objects from Egypt, which she donated to museums and universities in the US. (There’s a huge discussion about that to be had, which, as an archivist myself, I am drawn to explore. But, it falls outside the purview of this blog, so it’ll have to stay a discussion for another time and place.) These collections are still accessible to researchers and the public today. Rambova continued this work until her death in the 1960s.

Without doubt there are meaningful reasons to criticise Rambova and her work. Some of her design work is appropriative at best, overtly racist at worst. She had ignorant and arrogant attitudes toward class politics bred from her uber-privileged upbringing, which occasionally bled into her work and interfered with her ability to collaborate with other artists. She definitely lacked the social skills and business sense that were very necessary for artists working in a mass-media format like film. It’s typical, but disappointing still, that so much effort has been put into demonizing Rambova for reasons that were either completely fabricated, or rooted solely in the fact that she was a woman who knew her value, but by society’s standards, didn’t know her place. All that said, maybe we are due to spend a bit more time as film enthusiasts genuinely engaging with the art Rambova created and recognizing how much of a force she was in standing up for artistry in the American film industry.

☕Appreciate my work? Buy me a coffee! ☕

Postscript: This piece was a monster, so excuse me for not diving into rumours about Rambova’s potential queerness, as it eventually fell out of the scope of the essay. But, for those in the know: my personal take is that she likely was queer, though probably not romantically entwined with Nazimova, but maybe with Fredova. I also think her marriage with Valentino was not lavender. And, even if Rambova wasn’t queer, I appreciate what a keen collaborator she was with queer colleagues and what a good friend she apparently was to queer people in her social circles and her family, despite how often her detractors would try to use accusations of lesbianism as a weapon against her. IMO if someone were of weaker character, those types of aspersions would have driven a wedge between the object and their friends and colleagues.

Bibliography/Further Reading:

Madam Valentino: The Many Lives of Natacha Rambova by Michael Morris

Rudy: An Intimate Portrait of Rudolph Valentino by His Wife Natacha Rambova

Valentino As I Knew Him by George Ullman

Picture Play Magazine, August 1925

Photoplay Magazine, December 1922

Mythological Papyri – Texts by Alexandre Piankoff & Natacha Rambova

#1920S#natacha rambova#film history#cosplay#cosplay the classics#closet cosplay#film#american film#cinema#silent cinema#classic film#classic movies#old hollywood#self portrait#silent movies#silent era#long reads#silent film#costume design#art direction#set design#nazimova#alla nazimova#classic cinema#classic hollywood#hollywood

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

MGS3 arguably has the most relevant symbols of what I call the MGS Cycle (MGS1, MGS2, and MGS3... and MGS5. Though MGS5 is more like a supplement and less a cyclic element. )--

--The reason MGS4 doesn't count, is because it breaks the narrative cycle, by convoluting its characters, turning the symbols meaningless, and well, ending the story without use of the cycle motifs--

MGS3 is a kind of map legend to the MGS Cycle motif. It breaks down the basic archetypes into their most obvious selves. EVA represents the Love Interest, Ocelot still dominates his archetype as the double-triple-crosser, the Sniper character in the End, the Ninja in the Fear, the in-over-his-head science-tech type found in Sokalov...

Ecctra, ecctra.

But the one prominent one that's important, that MGS3 puts in your face Look-Here Blazing-Signs because it is that important... and that's who the Boss stands for.

The Boss appears out of the fog of her first introduction, like a legend out of the fogs of myth. She is constantly praised as not just a Legend, but The Legend, the Mother of Legends even. She is the mentor, to where even Big Boss is but a student.

( Character analysis? She is also a broken women that has had literally everything robbed from her, including cognition, but still marches forward regardless. She is the embodiment of the saying that one can control nothing in life but their attitude. Quite frankly, I got real sick of hearing people praise her and questioned how come nobody is trying to actually Help her. She says things that come out of left field and don't make a whole lot of contextual sense, like she's not always present, and that's saying something given that we're in Metal Gear. The only time she ever seems to truly focus and is present is when she's on mission--Yes she was a legend, we know, but fuck, she needed Help, not Praise. What the hell is wrong with the MGS3 Cast. )

The Boss is represented by a snake, yes, given she leads the Cobra Unit and she is arguably where Naked Snake himself gets all his icons (which he will later drop as Big Boss), but she is also represented by the Horse.

And not just any Horse either... though we do see her literal horse, which is why this narrative symbolism is even being considered.

And Remember that MGS3 is when we get introduced to Chinese elements through Eva, just as Ocelot introduced / introduces Wild West elements.

One of the more important Chinese Horse symbols, is the Idea Horse or the Horse of Will. It is the embodiment of the indomitable human body and spirit, and often paired up with the Monkey of Mind, or the embodiment of the unfettered human mind.

There was a famous Chinese story that ran with these exact motifs--and that's Journey to the West.

Only instead of Sun Wukong (Who is arguably the more fitting of an setting filled with Hollywood Action Films that MGS likes to mimic), MGS embodies and centers around one of the other disciples--Bai Long Ma, the White Horse Dragon, and representative of the Horse of Will.

( And that's not getting into how horses and snakes are often combined mythologically anyway )

Through both narrative motifs, ancient literary symbols (The Horse), and of course, MGS cycle archetypes (The Snake), the Boss represents the indomitable human will.

There is, in fact, no opponent in the MGS Cycle that we face, that represents that archetype, though it is the most important archetype of all MGS.

Because we've faced them as an opponent before, but we have played them as a player character.

And that's Solid Snake.

ADDENDUM: THE REASON MGS IS (MEANT TO BE) A CYCLE

The reason I call it the MGS Cycle, is because it is a repetitious story, inspite of background elements.

The Indomitable Will (Solid Snake) is at the end of his trials of Self, and takes his last trial of self--Facing the Building Blocks of Life and History experienced (MGS1 whose key word is Gene, the literal building blocks of Life and all villians in MGS1 will claim that the steps experienced in their history has made them who they are), and facing down his worse self, his shadow, (Liquid Snake).

A new trialer begins their trials of self (Raiden), which starts facing what makes up their mind (MGS2 keyword is Meme--is your mind real, or is it merely made up of what you're informed is real), where the rookie asks himself what is real, what to believe, what led him to this point, and facing himself lest he fall into delusion.

The Indomitable Will, seeking to break the cycle to allow the world to remain as it was, mentors the new trialer (often through grueling methods) as he takes on his new trials.

Now the mentoree (Jack / Naked Snake), strong through his teacher's teachings, after succeeding his Trial of Mind, he now must face his Trial of Reality (MGS3's keyword is Scene, the World is a stage, now that you know you are real, is the world you're in real?) as the warrior he was built to be. Unfortunately, this trial involves facing off against the Indomitable Will who has already taken all her trials (The Boss).

... and the Mentoree fails, because by defeating the Indomitable Will, he breaks his own will in the process and, wins the mission but fails the trial. He becomes an aspect of the trials for the next Indomitable Will to face down.

This is how the cycle, by its motifs, works. If MGS4 had followed the set narrative cycle, it would've resulted in Raiden killing Solid Snake, just as Naked Snake killed the Boss, and setting Raiden up to become the next "Big Boss" archetype.

... And then the cycle starts over.

MGS5 is an odd supplement, because its worth more if you place its story motifs between MGS2 and MGS3, rather following after MGS4. It details how the Indomitable Will, in spite of its rebellion against the cycle, would get re-entrenched into the cycle. The Boss, for all her will power, is, for some reason, insanely shackled by loyalty to something that she knows means her harm. MGS5 shows the metaphorical shackling--how do you shackle the Indomitable Will? By forcing it into a false form.

#metal gear solid#metal gear solid 1#mgs 1#metal gear solid 2#mgs2#metal gear solid 3#mgs3#metal gear solid 5#mgsv#solid snake#raiden#big boss#the boss mgs#analysis#lots of use of metaphor here

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Park Chan Wook + Jeong Seo-kyeong when making The Handmaiden (2016): juxtaposes objectification with genuine representation of sex, in a way Sarah Waters said is true to her novel Fingersmith that the film took inspiration from. Male entitlement is rejected as violent and unwanted a contrast to love between women being embraced as a means for liberation. Films sex between two women as actual sex - the full-bodied, passionate union between two people, without objectifying the women by keeping a distant, neutral frame that has the body parts men want to leer at out of focus. Shows women having active desire for each other, with love and sex being two sides of the same coin for those characters, as a contrast to men's cold view of women as objects. Uses abundant POV shots and spends a multitude of scenes building up the sexual tension and emotional intimacy before going explicit. Fills the scenes with narrative motifs and symbolism, emphasizing Hideko and Sookhee as equals despite their class disparity, as well as creating the imagery that two women can fulfill each other without a man. Focuses on the women's faces, includes dialogue and lots of humor. The scenes sex are literally so emotionally charged and revolutionary for the characters they are ready to change their entire life course after - it's the only time they can be completely honest with each other, and that emotional journey is conveyed. Writes Sookhee reclaiming the Count's fake fuckboy line of "spellbindingly beautiful" with literally the most genuine emotion after seeing Hideko's *****. Films cunnilingus as equivalent, or even superior, to penetration as a sex act. Asked an actual lesbian what sex would make sense to include in the movie, and from her request includes scissoring while making the point is it's an advanced sex move. Addresses the complexity that while men can objectify sex between women, the concept can at the same time be appealing to women and it's possible to reclaim it for yourself. Visually spells out that men thinking something is for them doesn't mean it is (their entitlement leads to the men literally dying). Explicitly dismantles pretty much all lesbian tragedy tropes with intent, such as suicide/death/torture/mental institution, lesbian relationships as inconsequential or ending in betrayal, lesbians having sex with or being objectified by men. Literally makes the whole movie about lesbians reclaiming narrative tropes used against them, and has them Win Everything with the most happy ending ever.

People with gender and film studies degrees who make a living out of writing intelligently about these topics: two women naked so for men :) only men like lesbian sex, please cut to black next time bc my brain cannot comprehend anything important happened, as I associate women having sex with p*rn and nothing else :) it's "performing" for men when it looks pretty! (in a movie something is Real and not performing when it looks Ugly). we as a society can only move on from the dichotomy of lesbian dehumanization as either desexualized or hypersexualized by diving all wlw media into the pure a-touch-of-your-hand-made-me-cry-alone-in-my-room-for-10-years with endlessly obsession about chaste Gazing from a distance versus the icky icky sex stuff that only men want to see!

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

CHUNGKING EXPRESS: My Journal Entry (5/30)

Initially, this post was supposed to be about Days of Being Wild, but I didn’t finish the movie because I’m still trying to sync up the subtitles on VLC media player. Perhaps it was for the better, because I gave myself a chance to experience an oriental classic in Chungking Express, and I don’t think I could’ve picked a better moment in my life to have watched this movie than now. There’s a lot I want to say about this movie and I think I’ll divide it into two parts — my personal reaction and my analysis on the cinematography and other technical components. I don’t plan on writing in too much detail here, although with enough pacing I could write an essay on this.

I couldn’t help but feel floored when I came to the realization that I was watching four stories being told, two at a time. Every story was reflective on intimacy in avenues I didn’t even anticipate. The four main characters all had an ambition yearning to be curbed and personally, Officer 663 & Faye was a story I felt consistently more invested in. I was drawn to Faye for her child-like insouciance and I think it was absolutely rad how she played a character based on herself. The film itself is escapist, and her character yearns for love and excitement within her life. In a way, it felt like looking in a mirror — I feel seen when she talked about saving money so she could live life in the way she desires to! I felt passion in the way Officer 663 looked after her too. Oh, to have lost a woman he loved dearly and still find it within himself to take care of a girl he just met in that manner…

Along the way, I also picked up on recurring motifs of togetherness. The planes on 663’s ex’s back, the goldfish, and even the song choices reflect that — so much symbols within the script are interconnected within each other. My favorite motif though is Officer Qi-Wu’s “love you for 10000 years.” For me, I feel that love in many aspects can be undying, contrary to Qi-Wu pondering if love could in fact expire (I couldn’t imagine fighting tooth and nail for fruit with a two day shelf life remaining. I digress though.) I’ll have nothing short of love for the faces of my loves past, and future. If anything, watching this movie reinforces the type of partner I know I’ll be someday: a patient, self-less lover.

What truly hit close to home for me was the progression of 663’s loneliness. At a point, he was lead to believe he was chasing love in a place he wouldn’t find it in and it made me feel melancholy because of how relatable it was. His old lady is happy with a new man and the new flame he’s embarked on — is she invested enough to reciprocate the infatuation? Some things just hurt more than being alone. The performance was a vibrant reminder of how far from guaranteed love truly is. However, if the desire is real, you don’t flinch from the flame within you.. However, if the desire is real, you don’t flinch from its flame.

#chungking express#faye wong#wong kar wai#christopher doyle#takeshi kaneshiro#film stills#film screencaps#film frames#dissecting

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Deep dives into folklore: changelings

Changelings are a captivating element of folklore across various cultures, with stories of these enigmatic creatures appearing in European traditions and beyond. The changeling myth revolves around the idea that fairies, elves, or other supernatural beings would abduct human children, replacing them with their own offspring or elderly individuals. These substitutes would appear identical to the human children they replaced but would often behave strangely, causing confusion, fear, and distress among families. Understanding the changeling myth requires exploring its origins, its role in society, and its impact on cultural beliefs and practices.

The changeling myth likely originated in pre-modern societies as a way to explain unexplained or distressing occurrences, particularly related to children. This may include:

Infant Illness and Developmental Disorders: In times when medical knowledge was limited, unexplained changes in a child's behavior, health, or appearance (such as sudden illness, developmental delays, or behavioral issues) could have been attributed to a changeling.

Cultural Beliefs in Supernatural Beings: Many societies believed in the existence of fairies, elves, and other supernatural beings who inhabited the natural world alongside humans. These beings were often seen as mischievous or malevolent, giving rise to stories of abduction and replacement.

Fear of the Unknown: The changeling myth reflects a deep-seated fear of the unknown and uncontrollable aspects of life. The concept of a child being replaced by a supernatural entity could represent broader anxieties about loss, change, and the mysteries of existence.

The changeling myth had a profound impact on society in several ways:

Treatment of Children: In some cases, suspected changelings were mistreated or even harmed in an attempt to expel the supernatural being and bring back the real child. This was often based on the belief that the changeling would reveal itself under duress.

Impact on Mothers and Families: The myth could lead to blame and ostracization of mothers if their child exhibited unusual behavior or illness. This added to the emotional burden and challenges faced by families.

Cultural Narratives: Changelings became a common motif in folklore, literature, and art. Stories and ballads often depicted the struggle of families to reclaim their children or the strange behavior of changelings.

Symbolism and Metaphor: The changeling myth has been interpreted symbolically in modern times, representing feelings of alienation or otherness. It can be seen as a metaphor for the challenges of parenting a child with special needs or the experience of not fitting into societal norms.

In contemporary culture, the changeling myth continues to resonate, finding its place in literature, film, and other media. Modern interpretations often explore themes of identity, transformation, and the boundaries between reality and fantasy. Additionally, the changeling myth serves as a reminder of the dangers of superstition and the importance of understanding and compassion, especially for those who may be different or marginalized.

The changeling myth is a multifaceted and enduring element of folklore that has influenced cultural beliefs and practices throughout history. It reflects the deep-seated fears and anxieties of past societies while continuing to captivate the imagination today. By understanding the origins and impact of the changeling myth, we can gain insight into the complexities of human experience and the ways in which folklore shapes our perceptions of the world.

#writeblr#writers of tumblr#writing#bookish#booklr#fantasy books#creative writing#book blog#ya fantasy books#ya books#deep dives into folklore#deep dives#myths#legends#folklore#changelings#fae#faeries#elves

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Oh my EFF, where DO I START. Moonlight Chicken, episode 7 thoughts and impressions. But first, a question for the family:

Did any of you notice the filming style slightly change during the condo/living room scene with Jim and Wen (after Jim put on the chicken shirt), and the second scene with Jam and Li Ming, when they’re eating the ginger stir-fry? In both scenes, I noticed that the camera pans were a bit more fast/jerky between characters, and that Jim and Jam (#jimjam) were filmed from the chest up. I wish I knew more about cinematography, but it seemed to me that the other shots throughout the show were wider and taller. I don’t know if this means anything to anyone, but if it does, I would love to hear thoughts on it. I feel like the shooting style gave those scenes some kind of different old-school flavor.

1) JUST GAAAAAAAHHHHHHHHHH WHY IS THIS SHOW SO GOOD. Sorry for the yelling, but now I know, I KNOW, full-bodied, there is no way one post is enough for each of these episodes, so just expect a whole freaking unspooling over the weekend. ANYWAY. I’ll try to organize the quick thoughts first, then the deep thoughts.

2) Just get First and Khao together again already! They can’t help their chemistry to be ridiculously great. AND HOW GOOD IS FIRST. HOW GOOD IS HE. Just knowing when to fume just slightly, when to pull back for the sake of a scene. AND HOW GOOD IS KHAOTUNG. God. His crying! It took me OUT. Tears over here, streaming tears.

3) Speaking of hearts aching, I cried not only during the funeral scene because of Khao, but because I love this now-repeating motif that Aof uses of bringing a song that’s sung in the show as music for the background of the show, à la Bad Buddy. To think of every step of art to weave into a drama to keep you fully connected -- it’s really beautiful to me.

4) Mark/Leng with his UCLA jacket, what up, Cali, cute cute. (By the way, I’m missing View/Praew. She was incredible in 10 Years Ticket, and I think she could have lent her brilliance to MC. I’m going to add The Shipper to my list for First/Ohm/View.)

5) The continued motif of showing the cast participating in time-honored spiritual rituals. As sad as it sounds, I love funeral scenes and the way a temple brings together a community. Even Wen working at the temple -- it’s very real (at least at the Indian/Asian funerals I saw as a kid) to basically have a lot of the funeral feel like a community get-together.

6) Heart joining Li Ming to hand out drinks at the temple just messed me up. It messed me up good. When the young adults automatically help out at events without being told by their parents. It means a lot in Asian societies.

7) Deeper thoughts. @wen-kexing-apologist hit on this in their BEAUTIFUL POST about the show being centered on parent-child relationships. There’s a lot here in this episode, I may not get to it all.

Here’s how I’d break it down (and this post by @justafriend-ql covers so much so well):

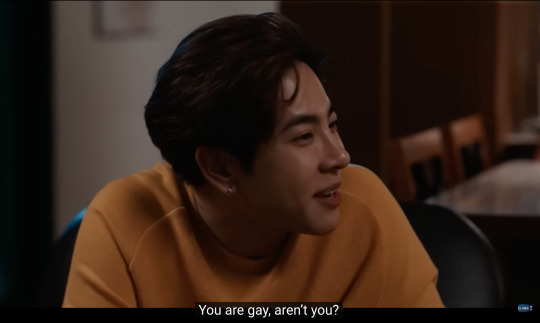

a) Jam comes back after years of not seeing Li Ming b) Li Ming is OBLIGATED, by UNSPOKEN CULTURAL RULES, to continue to respect her as a parent c) Li Ming, clearly, wants fucking none of it d) Li Ming/Fourth EMANATES distaste for what he’s dealing with e) Li Ming STILL has to control himself around his mom who moved him aside to live her life f) He has to ALSO DEAL with his uncle, who (yes, hypocritically) (but also hypothetically) asks him why he’s gay g) So Li Ming has to also deal with his uncle’s internalized homophobia and old-fashioned views on gays in society, which may very well arise in part from his upbringing in rural Isaan h) Jim has to also deal with his sister’s guilt over not having been a mom, and her trying to sort of half-heartedly show up (until the last scene with them, which I think was meant as a symbol that there might be healing happening among the three), and i) Jim beginning to see Li Ming for the adult that he is becoming.

@justafriend-ql covered in their two posts about Li Ming the sheer SIMMERING, the shimmering ANGER that Fourth portrayed, and I felt @wen-kexing-apologist’s pain in my bones when I watched those scenes.

So much of what I am loving about Aof’s work as I enjoy my ride through his oeuvre is this family dissection -- the microscopic examination of the painful aftereffects of holistic filial piety (COUGH Bad Buddy) -- and I can never say enough how important his family art work is to Asian audiences. When I see these scenes of young adults holding themselves back with every iota of their energy to not JUMP KICK their parents when they’re acting stupid -- man, I feel that so hard.

Jam coming back and asking for Li Ming is just lame, and we all know it, and Li Ming knows it. And yet, he is BOUND by CULTURAL PRACTICE -- cultural rules that even JIM REFERENCES -- to need to hold back and respect his mother, because that’s what Thai cultural boundaries demand. So I agree with @justafriend-ql that what Fourth radiated was beyond brilliant. As a viewer, I really want to see Li Ming’s gates open and to see him rage, because my inner child wants to rage right along with him.

But that night scene with Jim and Li Ming, man.

I think this bit of this scene is what ended up helping Jim to relax, and to see Li Ming as an adult.

I am loving how Jim is written. The constant, CONSTANT pull between old values and new. This scene so beautifully depicted Jim in that balancing struggle.

Li Ming is just pulling Jim along to the light of the future, as children/young adults do. Li Ming NEEDS his uncle to see HIMSELF (Jim) in Li Ming. And I think that’s what’s happening, in part, in this scene. Jim sees that Li Ming CAN understand how complicated the world is around him. Jim SEES that Li Ming is a CRITICAL THINKER.

Jim has been a solo parent for so long. He’s worried about his kid. They’re poor. His kid’s gay. Jim’s worried about his kid being poor and gay. Jim expresses it, at first, in an old-fashioned, shouting, angry way. Jim accidentally outs Li Ming to Jam.

And then. The two guys -- the guys -- sit with each other, rest and wash in the process of mourning an important member in the community. Jim tries to hear Li Ming at Li Ming’s level. And Jim finds that he can hear.

And maybe, even, Jim is beginning to learn that he can transcend those old-fashioned values -- those UNSPOKEN CULTURAL RULES that still bind much of Li Ming’s behavior towards his mother -- to be a model for Li Ming, AND TO HIMSELF, to live a hopefully more fulfilling life. (I think that might be what’s happening, in part, with the cancellation of the diner’s lease at the end of the episode -- but the preview for the finale has me wondering if I’m right.)

8) I don’t know how much I have left, but I took these screenshots to also talk about Jim’s internalized homophobia. I think I’ve covered it already in my Li Ming analysis, but come AWN, just look at this SASS BUCKET OVER HERE:

I took these to confirm that Jim was “just being a dad” (ugh) in the moment of him yelling at Li Ming, but I think Jim redeemed himself with that night chat with Li Ming. So I’m just gonna leave these screenshots here BECAUSE COULD WEN/MIX BE ANY MORE SASSY?

I’m already missing these guys. I need Our Skyy 2 REALLY SOON.

I’m gonna need a lot of sleep tonight to manage tomorrow.

#moonlight chicken#moonlight chicken meta#earthmix#firstkhao#earth pirapat#mix sahaphap#first kanaphan#khaotung thanawat#fourth nattawat#gemini norawit#jim x wen#wen x jim#alan x gaipa#gaipa x alan#these tags already existed i have nothing to do with creating them

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

Top 15 Fictional Trains

In the words of a random bit of silliness courtesy from the Internet, “I like trains.”

(SLAM-HONK-SPLAT.)

…If you got that reference…yay. XD

But seriously: ever since I was a boy, I’ve always had a fascination with the railway. From real-life trains and railways of great repute, to various fictional railroads and their engines found in books, video games, movies, and more. I’m not the only one: the railroad has always held an enduring sense of intrigue for all sorts of people all over the world. Something about these great Iron Horses, racing along the tracks, seeming to fly across the landscape with such grace and speed, remains iconic. From steam locomotives to more modern diesel engines and electric trains, the sense of power, speed, and the symbolization of ever-moving progress they embody will forever be indelible. Whether you’re fascinated by the real history and technical aspects of railways and their engines, or just see them as a fun visual motif, they aren’t going away.

I thought it would be fun to talk about some of my favorite fictional trains and engines, because…well…I just want to. Yeah, I’m not tying this one into anything, there’s no special occasion, I just…want to talk about them. Is that so wrong? I hope not. Now, this will be specifically dedicated to FICTIONAL trains, so you won’t be seeing real railway constructs on this list. And, of course, I have to know about the trains in question in order for them to count. (SPOILER ALERT: “Infinity Train” is nowhere on this list. I’ve never seen it, probably never will, and basically don’t know anything about it.) With that said, let’s get on with it! Full Steam Ahead! These are My Top 15 Favorite Fictional Trains.

15. The Rainbow Sun, from Shining Time Station/Thomas & the Magic Railroad.

It is pure nostalgia, above all else, that gets this train onto the list. The Rainbow Sun was the main engine piloted by Billy Twofeathers: chief engineer of the Indian Valley Railroad. This was the railway line serviced by the titular depot in “Shining Time Station.” The show, of course, was a showcase for the animated series “Thomas the Tank Engine & Friends,” during the 1990s; Shining Time and all of its characters acted as a framing device, with episodes of Thomas (usually connected in some way to the central plot) interspersed into the story. In the original TV series, the Rainbow Sun was portrayed by the Union Pacific 844. When the film “Thomas and the Magic Railroad” - which combined elements of Shining Time Station with Thomas & Friends - was made, all of the scenes at Shining Time were shot on the Strasburg Railroad. Strasburg’s 475 stood in for the Rainbow Sun. (That’s the version pictured here, since my guess is more people will recognize the movie than the TV show version.) There’s really not much to say about the Rainbow Sun, I just…like this train. Both versions. Both the movie and the show were a part of my childhood; this train, in each incarnation, is much the same.

14. The Sea Railway, from Spirited Away.

“Spirited Away” is widely considered one of the finest animated fantasy films ever made. Released by the world-renowned Studio Ghibli, this picture - like many of Ghibli’s greatest works - was the brainchild of the mighty Hayao Miyazaki, and is known for its sense of surreal, bizarre, at times nightmarish visuals and scenarios, as well as its fun and fascinating cast of crazy characters. One of the less bonkers elements of the film, yet also one of the most memorable, is the Sea Railway: while the scene where this train appears is brief, it is nevertheless very fondly recalled. In the scene, the main character - Sen - travels with her newfound friend, the mysterious No Face, to find the enchantress named Zeniba. The pair hop aboard the Sea Railway: a double diesel rail car that runs on tracks across the ocean. This is a scene all about visuals, that is both spectacular and yet shockingly peaceful. No dialogue, just the emotions of the music and the animation, as the strange railcar glides across the sea. Like several other trains on this list, its time in the film is short, but the moment is immortal.

13. The Ghost Train, from Casper: A Spirited Beginning.

This is a pretty “bleh” movie, in my opinion. A prequel to the 1995 film “Casper” (based on the comic and cartoon character of Casper the Friendly Ghost), this film tells the origins of the titular character. (They are nowhere near as interesting and exciting as they probably should be.) However, I’ve always had a soft spot for one particular part of the movie: the opening sequence. Why? Well, the movie starts off actually quite promising, with the ghostly Casper - freshly dead (how pleasant) - waking up on the Ghost Train. There have been many kinds of ghost trains in fiction over the years; in this case, it’s a railroad which transports souls to the afterlife. The Train is pure nightmare fuel of the best kind: a battered old steam train, carrying a heavy rake of carriages, with a crimson skull for a smokebox, its glowing eyes acting as the headlamps. Damned souls spew from its funnel in lieu of steam, skeletal limbs act as its coupling rods, and inside its chattering mandibles are a horde of black cats. The furniture inside the coaches is made from bones, only adding to its macabre sense of style. While it’s only onscreen for a few minutes (the opening, plus a couple of scenes later), this Ghost Train nevertheless made a big impression on me as a kid, and it was by far the best part of the film…which gives you a good idea of how bad the movie is, sadly. Still, points where points are due: this train is still pretty epic to this day.

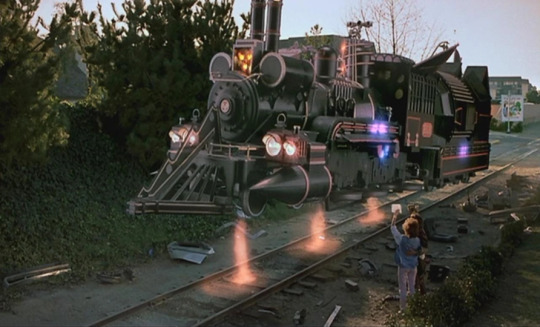

12. The Time Train, from Back to the Future: Part III.

What’s cooler than a DeLorean? The answer is…well…probably the TARDIS, if anything, BUT BESIDES THAT I’d say a flying, time-traveling steam locomotive definitely deserves some credit! In the climax of the third and final pillar of the “Back to the Future” Trilogy, our heroes engage in a daring chase scene involving a runaway steam train. At the end of the film, Doc Brown reappears before Marty McFly, and reveals he’s “recycled” the busted engine to create a time traveling train, colloquially and appropriately called the Time Train by most fans. (It’s also sometimes referred to as the Jules Verne Train, but I’ve always liked Time Train more: it’s catchier and simpler.) While I love the look of the Time Train, once again, it’s not onscreen for very long, and doesn’t honestly do THAT much in the grand scheme of things. It’s not even clear, despite what I’ve said, if this is the same engine as the one from earlier in the film, or just a very similar one, since the aforementioned steam train did sort of…well…friggin’ EXPLODE. Regardless, it’s a memorable engine, and has long been a fan favorite. Definitely worthy of placement in the Top 12.

11. The Soviet Missile Train, from Goldeneye.

One of the few non-steam engines to be mentioned on this countdown, this diesel engine is also one of the most sinister creations on the list. This armored passenger train is interesting in that it actually doubles a mobile secret headquarters: in the James Bond film “Goldeneye,” the main villain, Alec Trevelyan (a.k.a. Janus), rides around in this battering-ram-on-wheels with his henchman. The train is based on real-life armored trains owned by the Soviet Union, but has been exaggerated to give it a more outright evil, almost futuristic sort of look, with a sharpened nose and colored all in black, with blood red Soviet Stars on the sides. The train is destroyed when Bond first derails it with a tank (because of course he does, he’s James-flipping-Bond), and Trevelyan - forced to abandon his mobile HQ - blows up what remains in attempt to destroy his nemesis. The Missile Train made a memorable appearance in the Nintendo 64 video game adaptation of the film, where the players - as Bond - would have to make their way inside and around the train to take out Trevelyan’s goons and save our resident Bond Girl for the evening, Natalya Simova. Whether you love it best for the movie or the game, this big black beast is definitely one of the fiercest things to ever ride the rails.

10. The Wanderer, from Wild Wild West.

Much like the previous entry on the list, this steam engine proves that if there’s one thing cooler than a spy car, it’s a spy train. “Wild Wild West” was a TV series that was a sort of off-kilter combination of the spy film and Western genres. The plot focused on a pair of clever cowboys - Jim West and Artemus Gordon - who worked for a special branch of the U.S. Secret Service. They rode around the country, stopping crimes and committing acts of espionage against evil masterminds. To accomplish this, the pair traveled via a luxurious private passenger train called the Wanderer. In the series, the Wanderer was largely portrayed via stock footage of Inyo, an engine that, at the time, served the Baltimore Locomotive Works. The Train was basically just a mobile headquarters for the duo; it didn’t exactly do much, but it allowed for an interesting“Home Base” location to see in every episode, and it helped make the series a bit more unique. In the later 1999 movie version, starring Will Smith as Jim West (that’s the one pictured here, for the same reasons as the previously discussed Rainbow Sun), the famous engine the William Mason was used to portray the Wanderer. While the film is basically a giant mess, I’ve actually always had a sort of soft spot for it; it’s a guilty pleasure, to say the least. Part of what I liked was the way the movie “suped up” the Wanderer: not only was the train an HQ-on-wheels for the spy-fighting duo, but now it was basically the equivalent of having a Bond Car riding the rails, with all kinds of gadgets and secrets hidden in the engine and its coaches. Even if you don’t like the movie (trust me, you aren’t alone there), or never saw the series, I defy you to say the Wanderer isn’t pretty cool.

9. The Infernal Train, from Alice: Madness Returns.

Not all trains are colorful, whimsical, and fun to ride. Perhaps no fictional train in history has been quite as forbidding as the Infernal Train from “Alice: Madness Returns,” the sequel to the cult classic video game “American McGee’s Alice.” For those who don’t know, the games focus on a grown-up Alice having to traverse through a twisted, warped, morbid reimagining of Wonderland; shaped by her own trauma and insanity into a chaotic nightmare world. At the end of the first game, however, Alice is able to conquer her fears and problems, and seemingly goes off onto a happy ending…but in the second game, we soon learn it wasn’t that easy. When Alice returns to Wonderland, it at first seems to be back to how it should be, but it quickly becomes clear that new threats and new problems are once again causing it to steadily fall into a state of hellish doom. The centerpiece of all this horror is the Infernal Train: a massive locomotive, seemingly built from a Gothic cathedral, which soars through the skies of Wonderland, spreading a tar-like substance called Ruin wherever it goes, destroying everything in its path. Alice’s mission is to find out who is responsible for the Infernal Train, and stop it in its tracks before it completely obliterates Wonderland forever. The Train is almost a character in and of itself in the game; a force of nature, the presence of which is a constant source of dread. It’s one of the most sinister locomotives ever created, and memorably so. It has well-earned its place in my personal Top 10.

8. Casey Junior, from Dumbo.

Whenever I think of the phrase “Circus Train,” the first thing I think of is this whimsical train from the classic Disney movie, “Dumbo.” The whole movie focuses on the adventures of the titular character - a baby elephant with abnormally large ears - during his stay at a fictional circus. The circus travels from city to city, town to town, via the Casey Junior Circus Train, so called after its lead locomotive, Casey Junior. (The name is a reference to the famous engineer, Casey Jones, who would appear in his own animated Disney cartoon…but that’s another story.) Casey is the first train on this list who isn’t just a vehicle, but actually a real CHARACTER, with his own sentience and intelligence. He speaks in a voice that is made to mimic the puffing of steam, and seems to be a hardworking, determined, slightly child-like little engine. And, given the broad smile painted on his smokebox, we can presume he very much enjoys his work. Casey Junior has reappeared several times in the Disney canon since the release of Dumbo. Most notably, a non-sentient rendition of him appears in Tim Burton’s live-action remake of the original film, and there’s also a kids’ ride at Disneyland called the Casey Junior Circus Train. There’s also a water attraction at the Magic Kingdom in Walt Disney World called the Casey Junior Splash and Soak Station. No matter where he shows up, this chipper Circus Train is as confident as he is colorful.

7. Tootle.

So far, all of the trains we’ve talked about have come from screen treatments: movies, TV, and video games. This is our first engine on the list who originates from a book. “Tootle” is one of many titles in the classic Little Golden Books collection of stories, and focuses on its titular character: a rather silly steam train by the name of Tootle. Young Tootle is a brand new locomotive, still a child, who goes to the town of Lower Trainswitch, “where all the baby locomotives go to learn to become big locomotives.” Tootle wants to grow up to become a Flyer engine, a fast express train, so he studies very hard…but there’s one important lesson he has trouble with: “Stay on the Rails, No Matter What.” Tootle is a curious little engine, and he starts leaving the tracks to play in the meadow and explore off the rails. With help from his teacher, an old engineer named Bill, Tootle learns that, while there’s nothing necessarily wrong with dreaming, shirking one’s responsibilities and ignoring safety is never wise. It’s interesting to see stories like “Tootle,” which effectively teach children, “know your place.” At first, that probably sounds overly authoritarian and ill-advised, but in truth, sometimes it’s genuinely important to know one’s boundaries and limits: we all have dreams and desires we wish we could fulfill, but it’s important to know which dreams and desires are worth chasing, and which ones could just lead to trouble. The book is one of the most popular in the Little Golden Books series; in fact, in 2001, it was named the third best-selling English children’s book of all time! The story has been adapted to a PC game, a children’s audiobook, and more. The character of Tootle himself also appeared in the animated series “Little Golden Book Land,” inspired by the entire collection. I read a lot of these books as a kid, and “Tootle” was always my favorite. He and his tale are definitely worth placement in the Top 10.

6. Chugs, from The Easter Bunny is Comin’ to Town.

This somewhat obscure Rankin/Bass special is a follow-up/sequel to their more popular Christmas TV tale, “Santa Claus is Comin’ to Town.” Just as that holiday special told the origins of Santa Clause, this one tells the origins of the Easter Bunny. Part of these origins is explaining how the Easter Bunny gets around the world. Cue this little fellow: Chugs, a talking train whom the Easter Bunny - named Sunny - saves from possible scrap. Chugs is a little old engine whom no one ever uses, so Sunny buys him, cleans him up till he’s shiny and new again, and paints him in springtime colors. Chugs is thus given the job of piloting the little white rabbit and his train of Easter eggs, jellybeans, and other gifts for children all around the land. He also brings mail to the Easter Bunny’s home. (Because…well…we had to justify Fred Astaire returning as a singing mailman SOMEHOW, didn’t we?) I am convinced the reason anybody remembers this special at all is ENTIRELY because of this stop-motion animated locomotive. He’s certainly a big part of why I remember the movie; as a kid, I used to wish I could have a toy train of Chugs, so obviously, he’s got a soft spot deep in my heart. Oh, one other thing: Chugs is referred to as “the Famous Little Engine Who Could” in the story, which…I guess means this film technically also counts as an adaptation of that. Go figure. Speaking of which…

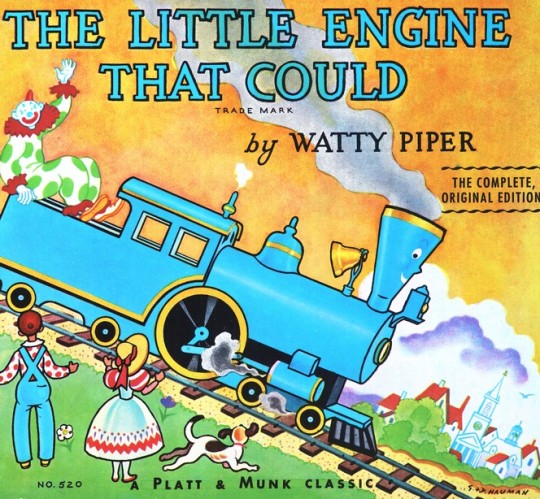

5. The Little Engine That Could.

This classic children’s book is actually based on an old folk story, which has been passed down through the generations. The railway folktale has changed over the years, but it’s the storybook publication written by Arnold Munk (published under the pen name “Watty Piper”) that has become the most well-known. In this version of the story, a train full of sentient toys and treats (I guess they must be riding through Toyland) breaks down on its way to bring its cargo to a town full of good little children on the other side of a tall mountain. The toys try to get various other trains to stop and help, but all of them refuse, either being too tired or too stuck-up. Just when all hope seems lost, a Little Blue Engine arrives, and she promises to get the train of toys and goodies to the town. All the way on the journey, the Little Blue Engine repeats a simple mantra: “I think I can, I think I can, I think I can.” Finally, her determination proves true, and the Little Blue Engine succeeds in pulling the train over the mountain. It’s a simple little story, which teaches a simple little message, but that’s really all it needs to be. The tale has been referenced, paid homage, and adapted numerous times: Chugs, of course, is inspired by the folktale, and even Casey Junior references it in a scene from Dumbo. My personal favorite adaptation is an animated short film made in the 1990s, which expanded on the story as written by Watty Piper, and featured voicework by many veteran performers; Kath Soucie plays the Little Blue Engine, and Megatron and Optimus Prime themselves - Frank Welker and Peter Cullen - also play characters in the story, just to name a few. Another adaptation of the Piper version was made in 2011, inspired by the 1990s short subject; that one featured talents like Whoopi Goldberg, Patrick Warburton, and Jamie Lee Curtis, again, just to name a few. No matter which take on the children’s story you look at, its simplicity is as immortal as the tale itself. I think one can say this Little Engine has many more mountains to cross before its story is truly finished.

4. The Rainbow Line, from Ressha Sentai ToQger.

“Hold on a second!” I hear you all cry. “That’s not a train! That’s a freaking robot!” Well, you’re right, and you’re wrong. It is, in fact, a giant mech made out of magical trains. Yes, you read that correctly. No, I am not drunk. Perhaps I should start from the beginning: “Ressha Sentai ToQger” is my personal favorite entry in the Super Sentai franchise. This series is basically the original version of Power Rangers: that show is essentially made, for those who don’t know, by Americanizing the Super Sentai shows in Japan. While both use some of the same footage and costumes, and follow the same basic plot points of colorful heroes fighting rubber suited monsters and using giant mechs for each final battle, the stories and characters are often very different. “ToQger” is one of the few Sentai series that hasn’t really been adapted into Power Rangers (at least not yet), and I rather hope it stays that way. In this one, the visual motif is - you guessed it - trains, with the Rangers using magical trains as their transportation system, as well as the means through which they battle the monsters when “giant mech time” happens. I don’t know what possessed Japan to make “Thomas the Tank Engine: Power Rangers Edition,” but I’m very glad it happened, because this show is amazing. The trains of the Rainbow Line - the good faction of the series (the villains are called The Shadow Line, and they have their own transforming locomotives to do battle with) - are all unique and colorful, and it’s honestly pretty cool to see how they all come together to from the massive machines the Rangers use in combat. There’s a toylike quality to all of the engines (which I think is intentional, given the themes of this series), and I would sincerely LOVE to have real toys of each and every one of them. If a fleet of locomotives that can turn into a sword-wielding, laser-blasting battle mech DOESN’T sound equal parts crazy and cool to you…I would like to know what does.

3. The Polar Express.

The top three choices on this list all have the same things in common: all of them started as trains in books, primarily aimed at children, but have since become massively popular largely due to the adaptations of said works. The first of these is the titular train from the classic Christmas story, “The Polar Express.” Originally appearing in a book written and illustrated by Chris Van Allsburg, the story arguably achieved critical mass when it was adapted into the still-very-popular 2004 animated film. The movie was directed by Robert Zemeckis, and starred Tom Hanks in multiple roles. Both are still considered staples of the Yuletide season. Both the film and the book have the same premise: the main character is a Boy who is whisked away by the titular magic train, which transports a group of children to the North Pole. It’s revealed that one of these children will have the honor of being given the First Gift of Christmas by Santa Claus himself that year. It’s a tale of belief and faith, both in oneself and in things beyond our ken. The book is well-known for its remarkable illustrative artistry, and the movie mostly lives up to it. Ever since the film came out, at least, it’s become quite popular around Christmas time for heritage railways around the world to have Polar Express outings, dressing up their engines and coaches to resemble the titular locomotive and its train. I’ve never gone on one of these trips, but even at my age, I’d still very much like to if I ever get a chance. The idea of this enchanted engine, racing through snow and mist to a place only children can understand, remains as powerful as it is entrancing. I dare say Christmas would not be Christmas without some version of the Polar Express.

2. The Hogwarts Express, from Harry Potter.