#they should be more kiki and bouba

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

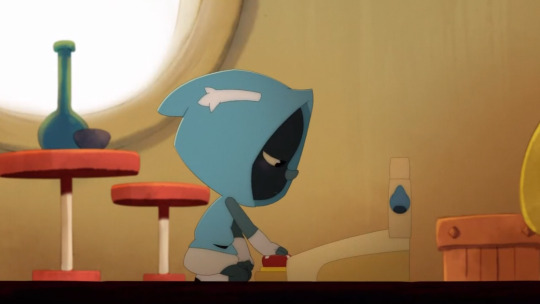

they're like if kyubey was a shipper and her grumpy subordinate

#i might make these their canonical designs for tweos btw :)#they should be more kiki and bouba#tikki#miraculous tikki#ml tikki#tikki kwami#tikki and plagg#plagg#miraculous plagg#plagg kwami#ml plagg#plikki#ml redesign#miraculous redesign#ladybug miraculous#cat miraculous#thewarmembraceofshadow#miraculous fandom#miraculous lb#wissym art

93 notes

·

View notes

Note

MORE SPIRK 🔥🔥🔥🔥 (Only if you want to, obviously.)

Kiki & booba core

#they should kiss#ask#anonymous#star trek#star trek tos#star trek the original series#spock#s'chn t'gai spock#jim kirk#kirk#james kirk#james t kirk#captain kirk#spirk#spock x kirk#art#fanart#traditional art#kiki and bouba#sun and moon#day and night#I can go all day#although I think it's more 'stars and moon' rather than sun. because sun and moon don't really go together like moon and stars idk

101 notes

·

View notes

Text

When a cat gets her claw stuck on something and just tugs at it pathetically while looking at me so I have to just grab her and maneuver her claw free. Because she's so stupid that she doesn't understand that Tugging doesn't free something that is hooked onto something. You must Push.

#speculation nation#this is about my tally btw. only her. i semi regularly have to free her claws from things.#it's not june tho bc generally when she gets stuck she just brute forces it free#tally is a gentle kitty. surprisingly tentative given that shes my outgoing and curious cat.#june is very easily startled and runs and hides at the slightest provocation#but she also throws her weight around a lot more. VERY ferocious when it comes to hunting bugs.#will force her way out of an unappealing situation. whether or not she should be able to.#she also bites all the time. like all the time. i cant cuddle with her bc i just end up getting chewed on.#i still Try to cuddle with her but ya kno.#anyways theyre both dumbasses but tally is somehow even more of a dumbass#despite being the sleek black cat to june's calico. tally is kiki and june is bouba. and tally is the dumber one.#every so often they come with me on trips and theyre in the boxes for over an hour. neither of them like this.#but once theyre freed. well tally is just fine. no grudges no lingering stress. nah shes Exploring!!!#whereas june runs and hides and stays hidden for days. as much as possible. to avoid more box times.#tally forgives and forgets. june holds grudges. theyre both pretty stupid though.

9 notes

·

View notes

Note

What the freak is Kiki and bouba

these guys

#Omg they should date shape yuri#Sorru#sorry#I think it was some test when given the words Kiki and bouba people were more likely to associate Kiki with sharper shapes#and rounder ones for bouba#could be wrong idk#☕️!- clove speaks#like martha speaks

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

you cant be a silly girl whos older than me AND have brown eyes you just cant. dont do this to me please

#txt#i stopd no chance shes so my type#PLEASE shes kiki to my bouba... insane lesbian craving 3000 miles a part#can the 2 nixon gals fall in love...#unlikely#im not being serious btw i dont expect anythinf i just 🥺 SHE IS AWESOME!!!! i want to be nicd to her forever#i should make more fan art... 😈

1 note

·

View note

Text

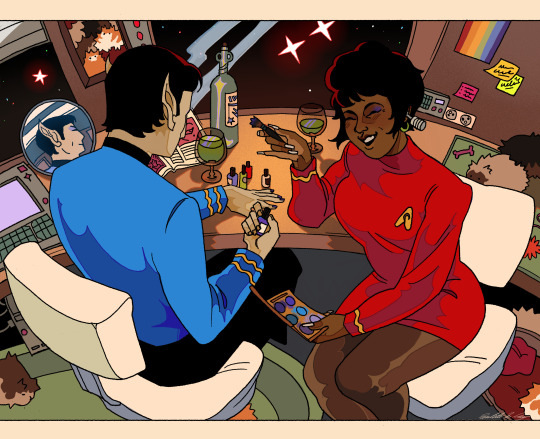

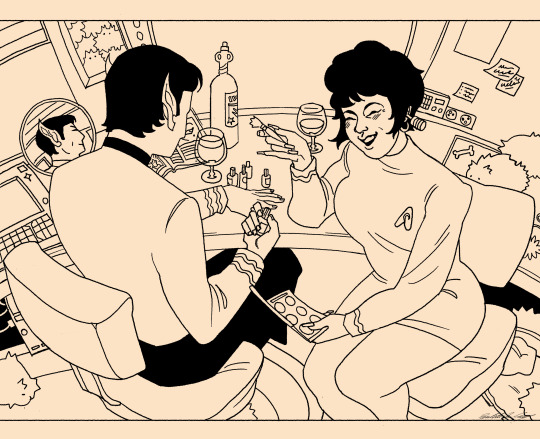

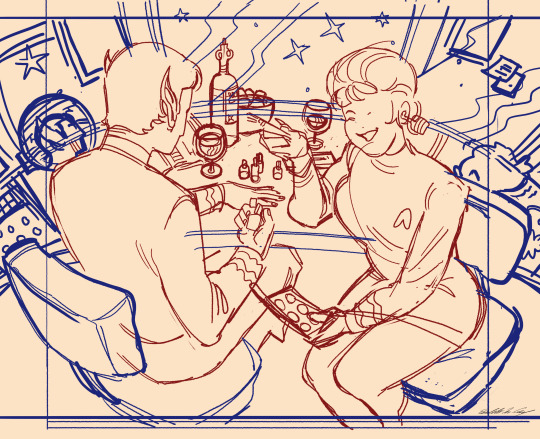

⭐ Besties on break ⭐

It's up as a print on my inprint ! :))

Kiki 4 bouba type ship

Loved imagining Uhura's space btw !!!! I had so much fun with the background ! Does it make sense ? Not really- but the vibes are here (I kept unconsciously adding tribbles kfkfk had to stop myself at six otherwise I would have just filled the scene with them)

[COMMISSION] - [PRINTS]

Process and rambling below vvv

The fact that quiji, back in 2022, showed me like 2 episodes before we watched the first movie.... And that I didn't hate it (still think the beginning is way too slow, especially for someone not really familiar with the characters, and the uniforms are *horrible*), should have been a sign that this fucking show would eventually consume my brain fklfof

Anyway this summer we watched more of the show and also watched up to the fourth movie ! And omfg the fourth one in particular rewrote my brain ckfkkf the Nimoy vision is incredible, the blorbos in silly situations after a pretty angsty movie, their flop era in a space clio 2, the whales- also thank god the marine biologist and old ass Kirk didn't have a romance (I'm choosing to interpret her as french, so that the little kiss on the cheek at the end is just a normal bise, the normal way to say goodbye to someone you now concider your friend <3 and not a hint of romantic interest toward this man who is 1) already married to Spock and 2) could be her dad)

I am now normal about this show I promise ! :)))))

#this was supposed to be a quick drawing- like a bit sketchy without much details ..... it got away from me#spock#nyota uhura#jim kirk#montgomery scott#tos spock#tos uhura#tos kirk#s'chn t'gai spock#tos scotty#star trek tos#star trek fanart#spirk#tos spirk#art#my art#digital art#fanart#illustration#tribbles

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

no actually i will give my unsolicited opinions on the driver logos, i've changed my mind. there are actually a few that i don't hate

alex has the only one i actually really like. it has some nice rounded corners and cool typography. he did initials and number without making my eyes hurt, so it is possible. if you gave me a jacket with that on it, i might actually keep it

i agee that ollie bearman should have a bear logo, but why is the bear so pointy ?!?!?!?!?!?!?! make it cuter

i actually like liam's silly little cartoon. like oh, let's make fun of the girl who took a risk and put herself out there cratively

the cute little fancy signatures that alonso and bortoleto have are cool, but a bit more subtle. idk if you want that in a logo. i like them tho

carlos's logo is only the number, so it might be less instantly recognizable, but it's just so clean. it simply looks good.

max's logo is fine. clean but boring and a bit ugly.

lando's logo looks more like a twitch streamer logo but he is one so he gets a pass i guess

charles, pierre, george, oscar, lance, jack, isack, esteban: that shit is ugly and you know it. stop this madness. at some point it is better to not have a logo at all. nico hülkenberg understands this. kimi too i guess?

i don't think the yuki logo on the previous post is current, the one with the leaves is a cute idea but i don't love the execution

i don't understand lewis's logo, but it looks good on a helmet. it looks like it should be the logo of a car brand. maybe he is playing the long game

in summary i think the problem is that most of the logos are way to kiki and need a bit more bouba

6 notes

·

View notes

Note

SO I went through the Project Opal tag and WOW. Great worldbuilding, I can picture it. How do you come up with names and words in the language? I focus on the real world with my writing so not much is left up to me to decide.

I’m glad you asked! Which I’m realizing is a phrase I use a lot!

Loredump time~!

And also

Linguistics time~!

So! The language spoken by people in the Vandeth Desert is called Vandeth. You asked about names and words, so I’ll talk about names and words.

I knew I wanted to use a constructed language (or conlang, for short) for the Vandeth people. After a previous project proved extremely time-consuming and not at all worth it, I decided to create Vandeth using a top-down method. I started by just making up words, then seeing what they had in common, finding rules they follow. Every word I made after that would follow those rules. And when I needed grammar rules, I made those up, and continued following them.

Some of the most important things are vowel inventory, consonant inventory, and phonotactics (what sequences of sounds are allowed to go together). Vandeth uses the standard /a/, /e/, /i/, /o/, and /u/ vowels, and that’s it. (They’re pronounced consistently, unlike in English.) I won’t write out all the consonants, but at this point I’m no longer adding any new ones.

Now, the phonotactics. This is mainly about syllable shapes. In Vandeth, the most common vowel shape is CV. After that is CVC. A very rare syllable shape is VC. Even rarer is CVV and CCVV. I also try to have a good balance of how often certain sounds appear and where. Hard, sharp sounds are more common, while soft, round sounds are rarer. What makes a sound hard, sharp, round, or soft is kinda vague. It’s a bit of a kiki/bouba situation. But to me, a word like “luvimo” doesn’t sound like Vandeth at all, but “shivaki” does.

But how do I even come up with new words? Well, I first look at the words I have and consider if it can be derived from any of those. At one point, I wanted a word for “gossip”. I looked at the words I had, and I noticed blai, “stain” and saksa, a verb stem meaning “to talk”. In Vandeth, words go after the word they describe, and when a word is derived from two others the words swip-swap. So the word for “gossip” ends up being blaisaksa. As another example, the word geital is a combination of gi, “two”, and keital, which used to be “gikeital” before it was shortened to be easier to say. The reason for this is that a geital is the same length as a keital but twice the length. The word keital itself actually comes from the verb stem kei, “to wear”, and the noun tal, “shadow”.

And what about names? Well, usually it’s just a word. Or it should be. I gave a throwaway character (an infant) the name Kimi, which in Vandeth means “pearl”. It’s kind of a cutesy name. Most often I just pick sounds that are Vandeth-y. It’s really important to me that Vandeth names (Vennem, Kalami, Mela) sound distinct from Delgane names (Lynn, Elvi, William, basically any English name) and names from other languages (Sóf, Markhi, Lili).

Don’t even get me started about grammar. There’s lots of linguistics and affixes involved, and admittedly, I haven’t made a whole lot of full sentences so the grammar is actually not super fleshed out. There’s enough for deriving words, though. Maybe I should just start translating random things, or have people send things to be translated via asks. Hmm… Anyway.

#stars. i’m such a nerd#but i love it and i love my work#this is super fun to me and i’m really glad there’s other people who enjoy it#asks#answered asks#cb answering stuff#project opal#lore dump#lore#wip lore#worldbuilding#conlang#constructed language

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sometimes I think about the “lines” of what is considered “a disability” as opposed to just “a difference”.

Prime example: Synesthesia generally isn’t considered a disability. There’s some evidence suggesting that most (all?) people have it to some extent, with stuff like the Bouba-Kiki effect. Even the “more involved” projective type usually doesn’t cause any real issues, neither internally nor socially. So I agree that it doesn’t make a ton of sense to consider it a disability…

Except I’ve heard it CAN be disabling in certain cases. I can’t find it now, but years and years ago I read a magazine article talking about a girl who needed accommodations for her synesthesia at school because certain colours / patterns triggered physical pain for her. From what I remember, the point of the article was “there should be more awareness of synesthesia, and a lot of kids (article was child-centric) could potentially benefit from accommodations for it”.

So there’s a trait, a neurological condition, that can sometimes be a disability and sometimes not.

It’s interesting to think about.

#Paris rambles#neurodiversity#neurodivergent#disability theory#<- maybe? I’ll delete the tag if it doesn’t fit

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

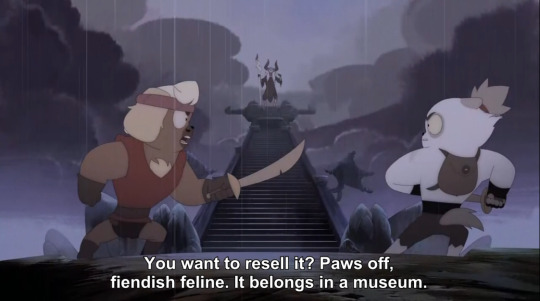

Episode 31 - The Break

It will be so refreshing to liveblog an episode that isn't heavy on characterization or analysis, oh god, I am tired of typing words.

He is so sad and for no reason... I just want to wrap him in a heated blanket.

World's most serious case of Sads, finished off with an evil little glare.

I can imagine adult Joris doing the same thing to Kerubim even by Wakfu times. Just a cunty, unamused little gaze. I can see it so clearly. This will happen in season 4, mark my words.

Also, inside me are two wolves. One of them wants to say "perhaps it's unusual for Joris to not go hook line and sinker for whatever ideas Keke proposes", and the other wants to say "Joris and Kerubim having psychic vibe battles moment #5"

He is so unserious.

Joris loses this round in the game of mutual psychological manipulations.

(Guy who notices landmarks in this show voice) (Also, guy who, for some reason, has developed a parasocial relationship with this setpiece in a kids show voice) THE TOWER. THE FUCKING TOWER

I've already spoken on this topic, but Kerubim already being known to sell stuff and have strong opinions on the ethics of museums makes me so unwell. Especially with implications of the Crepin family being salespeople.

I am not going to elaborate. You've read my other posts. Just... yeah.

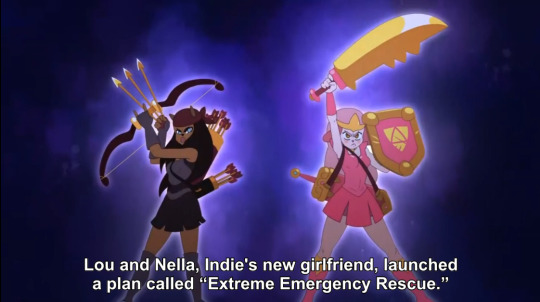

Can I get some love for non-Cra archers in this universe? The degree of unemployment must be hellish.

Also Lou has two swords, and Nella has two quivers. They are so normal.

Some may think that Kerubim is out of shape, but I will argue that this is his Farm Boy shape. His "not constantly on the road and fighting monsters while worrying about travelling supplies" shape.

He's still muscular, because Herding Animals is Serious Business, but he's got a bit of a gut going on, because there's no food insecurity, and the food he has is mostly meat and milk.

Considering old Kerubim also has the gut, — and is, notably, still very agile, — I think that this is just, like, Kerubim's natural shape when he's eating well and living like a normal person.

Sorry for overanalysing his body. I just wanted to talk about my "adventuring should be deconstructed as a concept and examined more closely, considering the multiple characters who had been ready to die "to become legends" about it. Like is all the trauma, food insecurity, and violence worth it, when the only way for people to truly respect you in this career, is to die in a cool way?" agenda.

The resemblance between young Keke in this episode and his older self is actually scary.

Say NO to alcohol, say YES to being a calcium-based lifeform.

I've never mentioned this before on this blog, but it's very likely that Kerubim is kind-of-sort-of accidentally implied to have an underbite.

It varies, whether he has his teeth in a normal bite, or an underbite, — and it is an art style choice, it happens to some other characters, albeit nowhere near as often as it does to Kerubim, — but, once you see it, and know what I'm talking about, you can't unsee it. Hell, it's on half the screenshots in this episode already!

Underbites are something that goes in families, which fits really well.

Because, like... yeah. That sure does seem like a family thing.

Together with the "pale-ish brown pigmentation around an eye or both eyes" thing, and the triangle-ish shape of their heads and snouts, Keke and Atch are the Bouba and Kiki of siblinghood.

Anyway, for transparency's sake, despite the underbite being one of Atcham's very notable character features, he is also sometimes drawn with a normal bite. Which might point towards Kerubim's underbite also being a genuine part of his character design, — instead of it being a case of animators liking the look of it a lot.

Personally, I like to think that both of them had been trying to fix his underbite his whole life by simply willing it away, and it's Not working.

If they actually realized they care about one another, and could be chill about it instead of immediately starting a Doomed Toxic Cottagecore Farm, Pangaea would reform.

Oh? You like Kerubim and Lou? Well, then, do you think Lou and Kerubim efficiently utilized girl power when they, Bontarians, went to their oh-so-hated Sidimote Moors and Brakmar, to conduct what they call a "slaughter-safari"?

This is not a Divorce Theory I usually subscribe to, but my funny crack theory is that she left him to go adventure around the world because he wanted to settle down and adopt a kid or whatever.

Truly, the possibilities of kerulou divorce theories are endless.

If they formed a polycule, Pangaea would explode.

I like to think that whatever Julith has going on is a cloak with a similar, but more complex enchantment.

This item is real, but I can't really find the sword mentioned by Lou moments prior.

I need to inject this image inside, intravenously.

...Anyway, you will never guess what my newest addition to the desktop wallpaper rotation is.

#ep31#ro liveblogs dofus#dofus#wakfu#krosmoz#atcham crepin#kerubim crepin#tagging them because i finally brought up The Crepin Teeth Agenda

17 notes

·

View notes

Note

For Parex: what are Fox and Kiki up to? (also is Kiki's name a reference to the bouba/kiki effect?)

I assume that this question refers to what happens to fox and kiki after the course of the story, because during the course of the story fox is just turbo brainwashed and being used as death watch's tool while kiki is a child, also turbo brainwashed.

after the events of the story, the jedi do some extensive deprogramming on fox to help him recover from both the empire and death watch so he's not completely dead inside anymore. he ends up on alderaan along with cody and rex trying to start a new life and also maybe get to know this family that he never really knew he had. he also gets to reconnect with boga while boga is doing his padawanship, and also maybe apologize for that time he shot boga off a cliff.

kiki ends up being adopted by bail and breha because rex kind of rescued/kidnapped him from kamino when he found out about the brainwashing thing and then just left him in alderaan. presumably he is doing much better now that he is being raised by loving parents instead of being put through kamino's brainwashing factory

(and yes, kiki is a reference to bouba/kiki. I did spend a while thinking of what boba's twin should be named, for a while I was thinking cha, as in tea. as in boba tea. but I just like kiki more so here we are)

ask me questions about parasitic extraction, the role reversal mandalorian empire au that I have

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Transcript Episode 89: Connecting with oral culture

This is a transcript for Lingthusiasm episode ‘Connecting with oral culture'. It’s been lightly edited for readability. Listen to the episode here or wherever you get your podcasts. Links to studies mentioned and further reading can be found on the episode show notes page.

[Music]

Lauren: Welcome to Lingthusiasm, a podcast that’s enthusiastic about linguistics! I’m Lauren Gawne.

Gretchen: I’m Gretchen McCulloch. Today, we’re getting enthusiastic about oral storytelling. But first, we have a fun new thing that you can do which is that we’ve created a highly scientific – [clears throat] – personality quiz where you can answer some very fun and fanciful questions and find out which Lingthusiasm episode most closely corresponds with those responses.

Lauren: If you’re new to the podcast, and you’re trying to figure out what episode to start with, or if you’ve been with us for ages, and you wanna dive into the back catalogue, or if you’re trying to figure out which episode to recommend to a friend, our incredibly un-scientific, often-amusing questioned quiz is there for you to find the perfect episode.

Gretchen: You mean, you don’t think that which beverage someone likes corresponds to which Lingthusiasm episode they’re gonna like? I think this is very scientific.

Lauren: Absolutely unvalidated, absolutely untested, they are entirely for your amusement at bit.ly/lingthusiasmquiz.

Gretchen: Unscientific – but very fun.

Lauren: You can also find the link in the episode show notes.

Gretchen: In our most recent bonus episode, we take this quiz ourselves to find out which episode we are – although, of course, we love all of them as our children – and we also talk about the results of our 2023 listener survey.

Lauren: This one is rigorously scientifically constructed and tested. We have all the results, including whether Lingthusiasm is more kiki or bouba, and we discuss the results of important questions like, “Is the thumb a finger?” and “Is your sister’s husband’s sister still your sister-in-law?”

Gretchen: You can go to patreon.com/lingthusiasm to get access to this bonus episode and way more behind-the-scenes and other fun topic bonus episodes that help us keep the show running for all of you.

[Music]

Lauren: A conversation I enjoy having is to ask two people how they met because, sometimes, you’ll get this wonderfully honed and polished version of the story that they’ve both told that may not actually be entirely the original story but is “The Story” of how they met. And sometimes, you get two completely different takes on the event, and that has its own value as well.

Gretchen: When it comes to the story of how we started this podcast, my version of the story is Lauren and I had been friends on the internet for a long time. We were finally hanging out in person for the first time at a conference, and Lauren was like, “I’ve been thinking about starting a podcast,” and I was like, “I’VE been thinking about starting a podcast,” and the rest, as they say, is history.

Lauren: Whereas I swear by the story that Gretchen was like, “I would love to do a podcast,” and I was like, “I have skills that I could bring to your great idea for a podcast. We should do this together.”

Gretchen: We had this conversation face-to-face not over email or over DMs or somewhere where it might’ve been recorded, so we have no record to know whose version of this memory is factually what happened, but emotionally, both of us think that it was the other person’s idea first, which I think is really funny.

Lauren: I’ve even gone back to look at early written interactions that we’ve had to see who started the conversation from social media through to DMs and emails, and I’ll tell you what, direct messages on social media platforms are not an archivist’s friend.

Gretchen: It’s really hard to actually find out what’s going on. Even our first emails to each other which we can find are continuing the conversation from DMs. But this tendency to want to have our life histories documented is a very written-culture technology sort of thing. It’s what made me recommend to you to read this short story by Ted Chiang, who I knew that you’d heard of as the author of Story of Your Life, which is the short story that was adapted into the movie Arrival. He has this other short story called The Truth of Fact, the Truth of Feeling, which I thought you would enjoy. Do you wanna give us a little summary of it?

Lauren: Sure. I mean, we’ve already talked about the fact that writing is a technology. We have a whole episode on the idea of putting symbols onto clay or paper or tortoise shells is a very particular cultural invention, but what I like about this short story is it gets to the point that this technology brings with it all of these social changes and social dynamics that create literacy. It’s a short story, but you get two for the price of one. There’re two completely different narratives that are happening in this story. The one that’s specifically about writing is about Jijingi, who is a Tiv speaker from Tivland. A missionary named Moseby arrives in his village. Jijingi is the only person in the village who takes Moseby up on the offer to learn how to write. Moseby comes along with a whole colonial project – very much like British colonial vibes – where writing comes along as a technology that is used to govern people administratively, so along with writing comes record-keeping and trying to write down and codify histories and rules. That brings with it all these changes to the social fabric of Tivland.

Gretchen: I liked this story because it talks about the effect of the transition from oral culture to written culture on memory and cultural shift. One of the ways that Chiang illustrates this is by having the second strand of this braided story, which features an unnamed journalist as the narrator who is talking about this futuristic technology – which the story is set some unknown number of years in the future – when everyone has started using “Remem,” which are these optical cameras – you carry around this iris cam which is giving you access to video footage of a whole bunch of things that have happened in your life, all of these moments that would’ve gone undocumented, like the moment when Lauren and I decided to start a podcast.

Lauren: We could go back and get the definitive version, which for us would be an amusing resolution, but our unnamed protagonist goes back to look at all the arguments he had with his teenage daughter, which is never gonna end well.

Gretchen: It causes the unnamed narrator of that story to reassess his relationship with his daughter and the accuracy – or the emotional truth – of these memories that he’s been feeling in one particular way and how it feels to go back and look at them from the perspective of this disinterested camera which was also present at the scene.

Lauren: We are so familiar with writing as a technology and as a memory tool. It was nice to be put in the position of being slightly bamboozled by this future technology and how that would once again make us reassess our relationship with – as the title of the story says – the truth of fact and the truth of feeling.

Gretchen: We’ll link to the short story because it’s available online. I definitely endorse reading it. What did you think about it when you read it?

Lauren: I assume that the story of the Jijingi is – it seems to be drawing on the thing that we see happen when Western cultures brought literacy in with them because there’s all these dynamics around the written record changing the oral tradition where different tribes would talk about how they were related to each other, and then they were like, “No, because you’ve written it down here, and the written version is the definitive version, so we’re not gonna honour the current status of knowledge about which groups your group is aligned with.” I assume the specifics of that were fiction, but it seems to really capture the vibe of that.

Gretchen: Interestingly, this specific case is a real case that happened. Of course, the specific names of the people involved and what they were thinking, I think, are, indeed, fictionalised. But the Tiv people of Nigeria had a set of genealogies that were being used in settling court disputes, and they were recorded by the British in the colonial context. Then they diverged in the oral tradition from the written thing, and then the later oral people were saying, “No, you guys have written down the wrong thing. We have what’s true here.”

Lauren: Because that’s what’s true at this point in time for – like, “We’re friends with this community over here right now and not this other village, so we’re gonna update the story to reflect the current state of things.”

Gretchen: Right. And there isn’t perceived to be a rupture in that the way writing can create a rupture between your perceived-self versus the version of yourself that you’ve projected into the past. What I was told was that Chiang had read an academic manuscript about the effects of orality and literacy on cultures and on humans by an academic named Walter J. Ong and had been inspired to take a few sentences from that and expand that into a whole short story that elaborates on the emotional truths addressed in that relatively dry academic fashion.

Lauren: It’s very satisfying because I was like, “This feels like a story,” but it did feel grounded in an understanding of how literacy can change social dynamics.

Gretchen: I was inspired to read the academic book as well by this, but the short story conveys these truths in a more vivid storytelling way, which gets to the whole storytelling themes that come up from making things memorable by telling them as stories.

Lauren: I appreciate you sent me the short story and not the 200-page academic manuscript.

Gretchen: I read the 200-page academic manuscript! I think it’s very interesting. We’ll return to more things from the Ong book so that not everybody has to read it. But one of the things that reading this Ong book about orality and literacy made me reflect on was what he calls “residual orality,” little pockets of our lives and our experiences that may still be in an oral culture even when we’re living in predominantly written cultures, which you and I are both predominantly in a written culture. One example of this coming up in my life was I’m just young enough to remember when social media changed the way that gossip worked to be more written from being more oral.

Lauren: Ah, yes.

Gretchen: I remember in a pre-Facebook era of gossip where let’s say there was a party, and I wasn’t there. If some big drama happened at the party, you know, “I can’t believe so-and-so said this to so-and-so,” there’s a big fight or something, and I wanted to reconstruct what happened, I had to go talk to a bunch of people – I remember doing this – talk to a bunch of people, get their stories, which would all be a little bit different from each other, and decide what I believed from that based on my knowledge of these people and their personalities and what they were likely to tell as a story. I remember it being a really weird experience when Facebook started, and people would be posting things that were in view of just their friends. You could see similar types of dramas playing out – you know, “I can’t believe what this person said to that person” – but you could actually read the whole thing, and you could be present for the whole thing, and you could have that factive truth of witnessing the whole thing, even if you weren’t there at the time, because a few hours later it would still be there.

Lauren: And the pulling out your phone to tell someone some gossip that’s happened because you want to hold up the Instagram photo or you want to show them the Facebook thread where all the drama went down.

Gretchen: Right. Screencap culture of “I can’t believe this person said this thing. I’m gonna take a screencap and just show it to you” rather than “I’m going to report the story of what happened from my perspective” has made gossip more of a written culture than an oral culture where we have less acceptance for the fact that things may change a bit in the retelling, or you may retell the version as you experienced it from your own perspective and massage it to be more of a story with emotional beats at particular places. Now, you pull out a screencap, or you pull out the actual version, “Let me just read you what this person sent me.” Gossip has gotten more written in the last 20 years, which you can phrase that as a loss, and it’s also harder for people to deny obviously jerk-ish behaviour, so there are pluses to it, but it is something that’s changed.

Lauren: Another area that I think of as residual oral culture is when it comes to fairy tales. As a kid, it took me a long time – and I think a lot of people struggle with this tension – where the animated film version of a fairy tale is different to the picture book that you have which is different to a different picture book that someone else might have or the version that your grandmother told you not from a book just the version that she had. This is how fairy tales traditionally go. This idea that there’s a written, canonical version kind of came about when the Grimm Brothers decided to record fairy tales that they had encountered as part of their general documenting of German language and German history. I love that the Grimm Brothers are known most broadly for their fairy tale writing down. In linguistics, they’re known for doing all of this amazing historical research on the sounds of German and Proto-German. Fairy tales are their secondary claim to fame for linguists.

Gretchen: But giving the claim to fame of the people who did the documentation when what they were actually doing was documenting a thing that was in the collective memory of a group of people is a theme that keeps coming back when it comes to oral culture. Again, I am grateful to the Grimm Brothers for writing all of these stories down because otherwise I probably wouldn’t know them, as with many of the documenters. On the other hand, they ended up getting credit or claiming credit for all of these people whose names we don’t know who iterated on various versions of these fairy tales because they were part of a collective oral tradition.

Lauren: Also, writing something down doesn’t mean that it will stay a part of the transmission tradition. The Grimm Brothers over multiple volumes and multiple reversions of it ended up with around 200 fairy tales.

Gretchen: I don’t know 200 fairy tales.

Lauren: You mean you don’t know “The Three Snake-Leaves”?

Gretchen: I know “Cinderella.”

Lauren: Are you looking forward to the animated remake of “The Mouse, the Bird, and the Sausage”?

Gretchen: I know “The Princess and the Pea”?

Lauren: Some Grimm fairy tales have stood the test of time, and others have not remained in transmission for different groups of people. You might be from a different part of the world where you still know “The Magic Table, the Gold-Donkey, and the Club in the Sack,” but that’s not one that I’ve kept in my family repository of stories.

Gretchen: But writing lets things remain in an archive for someone to rediscover rather than the cultural pruning of the oral tradition where the bits that gets remembered are the bits that get continually repeated.

Lauren: There’s a lot of oral culture that we only have thanks to the written form. Homer and the Homeric epics – the Iliad and the Odyssey – only exist because someone at some point wrote down a version of those stories.

Gretchen: Somebody who may or may not have been a guy named Homer.

Lauren: But I have a statue of the bust of Homer! He was a person!

Gretchen: I mean, there certainly was some person and some people somewhere, but Homer is, in many ways, a cultural folkloric figure himself. By tradition, these poems are attributed to Homer, but they may not have even been written by the same dude. They certainly seem to have some temporal distinctions between the Iliad and the Odyssey. They were definitely part of the Ancient Greek oral tradition because they have a lot of structural features that are characteristic of the oral tradition, the sort of episodic structure, the formulaic things like “wily Odysseus” and “owl-eyed Athena” and the various epithets that get attached to the characters who are these clear archetypes. Homer himself – we don’t really know. This idea that he was this blind guy is because one of the bards in one of the Homeric poems is blind, and people have said, “Well, maybe this is a self-insert because he himself was blind.” We don’t know.

Lauren: Amazing.

Gretchen: The paintings and the busts and so on of Homer are all produced several hundred years later. They’re sort of fanfic adaptations of him.

Lauren: I actually feel more impressed when I discovered that Homer wasn’t a single person and, in fact, this whole debate about the status of him is known as the “Homeric question.” I feel more impressed knowing that there wasn’t just one person who told these stories but there were, and still are, people across this region who would remember thousands and thousands of lines of oral stories and be able to perform them – not word-for-word every time – but they would hit the same beats, they would be transmitting the same stories, they would all put their own spin on it, and that this continued on for centuries and millennia, and somehow I find that more powerful than the idea that there was this one dude in particular who was really good at this.

Gretchen: It wasn’t this lone genius. It was a culture that supported bardic storytelling.

Lauren: It wasn’t necessarily a culture that just disappeared with Ancient Greece. In fact, even well into the 20th Century, if you went to the region in Europe around there, there would be people in mountain villages who still sang epic songs of incredible length. Milman Parry was an American classicist who decided to see if there were any “modern Homers,” as it was put, and he recorded one song that was performed over five days and ended up being 13,000 lines, which is just an amazing skill to have and one that, as a literate person, I’ve not grown up to be trained to have the kind of memory to perform that kind of feat.

Gretchen: That’s really neat. I think a thing that interests me about the question of the Homeric recordings and Milman Parry’s recordings is that the Homeric Greeks, whoever Homer was or all of the Homers were, were using this new technology – to them – of writing to record these oral poems that were very important to them culturally. Then you have Milman Parry using also the latest and greatest recording technology which was, what, wax cylinders?

Lauren: Oh my gosh, I think it was these aluminium disks that they had to swap out every five minutes or something. I can’t even imagine the amount of equipment that they had to move around to make this happen.

Gretchen: Yet, it’s still such a feat to record a five-day poem. There’s also a big recording feat that happened in the 1960s to record the Mwindo epic from the Nyanga people in the Congo. The poet there, Candi Rureke, who was asked to narrate all of the stories of Mwindo, who’s the hero of these folk stories, and said, “Never had anybody performed all of the episodes in sequence.” He narrated, as a result of the negotiations between the researchers who wanted to do this, all of the Mwindo stories – sometimes in prose, sometimes in verse – over 12 days. There were three scribes – two Nyanga scribes and one Belgian scribe – who were writing down his words at the same time because it’s obviously faster than one person can write. This is not like writing a novel or a poem. It’s much more of a performance. After the end of those 12 days, he was exhausted, obviously.

Lauren: I’m not surprised.

Gretchen: It’s already framed in terms of the demands of writing, which says, “Okay, we’re gonna try to do this in a big, tight sequence and have this efficient thing.” Oral poems are created to be told to people for maybe an hour or two in the evenings, and then the next day, you tell another story for an hour or two, and together, they form an episodic mythology of “Here are all the stories of the gods” or “Here are all the stories of the heroes” or “Here are all the stories of these archetypal, legendary figures” – the princesses and the dragons and these types of things.

Lauren: As a member of the Nyanga community, you hear all the Mwindo stories across your lifetime. The idea that you would sit down and tell them in some kind of sequence is not the normal way these are performed.

Gretchen: Right, exactly. There’s a story about Mwindo, who’s the hero – the omnicompetent hero – his epithet is “Little-One-Just-Born-He-Walked.” He walked as soon as he was born. There are stories about how he climbed from the womb and, in one case, emerged from his mother’s bellybutton. This is the version from the recording with Rureke that I was able to find. But I also saw in a different encyclopaedia that Mwindo emerged from his mother’s middle finger. They’re both clearly doing a similar preternatural birth-style story – emerging from your bellybutton or from your middle finger – but the details can vary. In both cases, the important stuff is still there where he’s helping his mother with chores even while he’s still in the womb. He’s walking and talking from the moment he’s born. His father’s trying to only have daughters because there’s a prophecy that his son will be his downfall. He tries to kill Mwindo even as a baby and, of course, he doesn’t succeed because this is a hero.

Lauren: What a precocious child.

Gretchen: Exactly. But the birth story is one of the many stories that gets told and isn’t necessarily told in sequence where it’s like, “Well, first he was born, and then this thing happened and then this thing happened.” You could pick any one of them to tell on a given night.

Lauren: It’s interesting how we see stuff vary in oral narratives, but there’s also something really compelling about what is emerging as the same across different stories and, often, across large areas. I mentioned briefly that the Grimm Brothers kicked off this whole recording of folk stories and fairy stories across Europe and beyond. People have looked at the similarities there. But there’s this even bigger story that I find really compelling, which is the story of the Seven Sisters, which I know from Indigenous Australian narrative tradition.

Gretchen: I’ve heard of the Seven Sisters as referring to a Greek story about the constellation that I also know as the Pleiades. It’s got this very closely clustered set of stars in the night sky that's sort of shaped like a teeny-tiny Big Dipper, I think of it. In my recollection, when I’ve looked at the Pleiades myself, I’ve seen six stars, and yet, the Greek stories about the Seven Sisters, the Indigenous Australian stories about the Seven Sisters.

Lauren: Yeah, the story in Australia is about the same set of Pleiades of which there are six if you look in the sky now, but some astronomers did some research that looked at how one of those stars is actually two stars, one in front of the other, and if you rewound the sky 10,000 years, they would be two different stars. The story of the Seven Sisters is that one of them is shy. You don’t see her, and she hides herself. It seems like this story that gets told across cultures is to account for what has been a changing of the sky across millennia.

Gretchen: That’s fascinating. This lost seventh star, or seventh person represented by the star, has been found in European, African, Asian, Indonesian, Native American, Indigenous Australian cultures that have – I mean, they’re a very cluster-y cluster. I have to say, if you’re looking at the night sky and looking for like, “I think these ones all go together,” they’re very close according to our visual perception on Earth. I can see why you’d come up with a story about them.

Lauren: Being in the night sky is a really good hook for remembering the story and continuing to pass it on as you all look up into the sky.

Gretchen: Yeah. But the fact that this seventh star has been transmitted for maybe 10,000 years is phenomenal.

Lauren: And a really great example of how oral culture can be a really great way of preserving knowledge or recording history not in the way that we think about it with writing. Not to say that that’s the only value that it has because it absolutely doesn’t, but it is one really interesting thing about the way we preserve and transmit these stories.

Gretchen: We don’t have written records that are 10,000 years old. Writing is not that old. Scientists have sometimes wondered, “How could we try to transmit a message to people 10,000 years in the future?” If we look towards the past of what kinds of things did get transmitted, maybe we need to take inspiration from oral cultures. One group of scientists and folklorists who’ve been trying to figure out the way to transmit messages for a long period of time are people who are trying to come up with long-term nuclear waste warning messages.

Lauren: Hmm, because that nuclear waste is still gonna be nasty well beyond any period we know we have successful transmitted messages in human history to date.

Gretchen: There’s this fascinatingly named field of research called “nuclear semiotics.”

Lauren: Oh, that sounds amazing. What is that?

Gretchen: Which is the study of how to create nuclear warning messages that will still be intelligible 10,000 years in the future.

Lauren: Oh, because we have that yellow triangle with the black spikey symbol, but I’ve absolutely heard of people who were like, “My 5-year-old looked at that symbol and thought it was a flower.”

Gretchen: Right. Or if you use a skull, well, sometimes skulls are, you know, maybe it’s pirates.

Lauren: Yellow might be meaning that it’s something really cool in here rather than a bit of a warning.

Gretchen: There’s a lot of proposals. Some of them are more practical and some of them are a little bit more wacky. Certainly, writing it out in a whole bunch of different languages so that even if some of them aren’t in common use in thousands of years, maybe at least some of them will still be sort of around.

Lauren: Or maybe we’ll have reverted entirely to being oral cultures again. Literacy has arrived. It may not stay.

Gretchen: But if literacy doesn’t stick around, then one of my favourite proposals is the breeding of so-called “radiation cats” or “ray cats” – because we have had cats for more than 10,000 years. We know that.

Lauren: That is true.

Gretchen: If you bred a special type of cat where they would change colour when they came near radioactive emissions, and then you’d have to transmit the message that if the cat changes colour, it’s bad.

Lauren: Oh, you make a folk story out of colour-changing kitties which will be out there in the world and, hopefully, that story gets passed on along with the other folktales.

Gretchen: You have to make a fairy tale and myths and poetry and music and painting about the dangers of colour-changing cats. You have to get all of the cats or many of the cats to be colour-changing, but people like cats. There was an episode of the podcast 99% Invisible where they commissioned a musician to write a song about ray cats for a 2014 episode about this which was called “10,000-Year Earworm to Discourage Resettlement Near Nuclear Waste Repositories (Don't Change Color, Kitty),” which was supposed to be so catchy and annoying that it might actually get handed down and stay working. But I have to say, I have never heard people sing this song in a cultural-folkloric sense, so I don’t know if they succeeded in having it be transmitted even 10 years.

Lauren: But you know, I listened to that episode many years ago, and as soon as you said “colour-changing kitties,” I knew exactly what was happening even though I did not know nuclear semiotics. So, there you go. There might be hope.

Gretchen: Maybe if it’s a wacky enough idea, people will keep talking about it because it sounds so cool.

Lauren: It’s really good applied folklore studies there.

Gretchen: In addition to transmitting information about how many stars are in this particular constellation, this speaks to the role of folklore and oral cultures in shaping behaviour. Maybe that’s telling people to not go near the colour-changing cats, but also, there’s a whole bunch of Aesop’s Fables around things like jealousy or things like ingenuity, various clever things that foxes do or things like that. Those are ways of telling people about appropriate or inappropriate behaviour.

Lauren: I bet you’re gonna tell me Aesop isn’t real either.

Gretchen: Well, look, it seems like the fables originally were part of oral tradition and were written down about three centuries after Aesop’s death.

Lauren: Ok, so the fact of feeling rather than the fact of truth. I get it.

Gretchen: I think at that point there were various things that, once you had Aesop’s Fables as a template for a certain type of morality story, you can ascribe various other kinds of stories and jokes and proverbs to him, even though some of that is from earlier than his period or is not just strictly from the Greek cultural area.

Lauren: Aesop’s Fables, where usually animals perform different actions, and they have moral consequences, it’s actually a really good teaching tool, teaching children about cultural expectations around behaviour and what counts as good behaviour and what counts as rude behaviour. That’s really hard. Having stories to do that with rather than waiting for them to make every possible social mistake is a really great cultural tool.

Gretchen: A lot of parents these days will buy their kid a picture book about, like, “Here’s the potty, and why you might want to use it” or “Saying ‘thank you’ – it’s important. Here’s all the ways we can say ‘thank you’” to also try to mould their kids’ behaviour into some of the things that’re culturally important to us.

Lauren: It’s why it’s really fun to see different morality stories across different cultures as really interesting ways to see what a particular culture values.

Gretchen: There’s an interesting story about Inuit storytelling as used to discipline or to train children into things that are important. Obviously, it’s important for kids to stay away and be careful around the ocean where they could easily drown. Instead of yelling at them, you know, “Don’t go near the water!”, you can tell them a story about a sea monster who is in the water who could eat little children, which is a little bit more vivid in terms of the potential –

Lauren: It certainly gets the point across.

Gretchen: It’s a bit more vivid than just saying, “Don’t go near the water. It’s not safe,” to tell you here’s this fanciful story that the kid may or may not completely believe in a literal sense but conveys this message of “This is dangerous. Don’t do that.”

Lauren: You know, we don’t just have to tell children stories to teach them lessons. Society has a long tradition of telling children stories at bedtime.

Gretchen: There’s a really fun version of this. Another epic poem that was written down so early that we don’t know the original poet’s name is Beowulf in the Old English Tradition. In this case, we don’t even have a “Homer” name. Even though we don’t know anything about Homer, Homer’s name is ascribed to this poem by tradition. In the case of Beowulf, we just call this person the “Beowulf Poet” because we don’t even know who wrote it down or which exact people it passed through, but it has many of these similar characteristics in terms of having these formulaic elements and these rhythmic elements that make it easy to remember as a poem and eventually get written down.

Lauren: It was written so early in the history of English that we’ve even talked in a previous episode about how there is a modern translation of it into an English that is more accessible to us today.

Gretchen: There’re many translations of it into various different kinds and registers of Modern English. At the time, I was very excited about the Maria Dahvana Headley translation, which begins with “Bro” to translate the “Hwaet” word at the beginning which gets your attention. Other people have also translated this word with things like “So” and “Look” or “Listen.” There’s another new translation of this poem which reimagines it as a children’s story where all the characters are children, and the monster that comes and eats the warriors and drags them back to his lair and so on is, instead, a sort of grumpy old neighbour who goes into the children’s treehouse and makes them grow up instantly into boring adults.

Lauren: Oh, how terrifying!

Gretchen: The connection here is that this adaptation was written by Zach Weinersmith, who’s a webcomics guy, mostly, who started telling it as a story to his kids as a bedtime story and found that oral culture stories, even though we think of them as high-culture and complicated and things, actually tell really well to children because children are still operating under an oral culture in many cases because they haven’t learned how to read yet.

Lauren: Oh my gosh, you’re so right. I feel like my early primary-schooling days were such a rich world of all those rhymes and stories and games that you learn as a little kid. So good!

Gretchen: Right, like the skipping games and the clapping games which get transmitted by other children, and sometimes you meet someone from somewhere else, and they’ve got a slightly different version of “Ring Around the Rosie.”

Lauren: Mine was “Ring around the rosie, a pocket full of posies, a tissue, a tissue, we all fall down.”

Gretchen: Mine was “Ashes, ashes, we all fall down.”

Lauren: Ah, there you go. I mean, yours is obviously incorrect, but good for you. [Laughter]

Gretchen: We were transmitted different versions of those rhymes, but they have this characteristic game of holding hands and running around in a circle and falling down that they go with even if parts of it, especially the little bit more nonsensical parts, got transmitted into something else that felt a bit more sensical.

Lauren: How does the Beowulf retelling read? It must be fun to read out loud.

Gretchen: It’s really fun to read out loud. Here’s the first couple lines, which go “Hey, wait! Listen to the lives of the long-ago kids, the world-fighters/ The parent-unminding kids, the improper, the politeness-proof/ The unbowed bully-crushers, the bedtime-breakers, the raspberry-blowers/ Fighters of fun-killers, fearing nothing, fated for fame.”

Lauren: Oh, so good.

Gretchen: I love that it’s doing the alliterative Anglo-Saxon metre, and it’s doing all these very Old English compounds of “world-fighters” and “bedtime breakers” and “fun killers.”

Lauren: That’s still accessible.

Gretchen: That’s still accessible and playing with the language but in a way that’s still available to kids. I recommended it to some of my friends with kids, and they said their 5-year-old loved it.

Lauren: Perfect. A lot of highly literate people are untrained in oral storytelling that, personally, having something I can read to replicate that experience is really reassuring for me as a limited-capacity literate person here.

Gretchen: I also think it’s neat because children’s stories are trying to do two different things. One of those is create pre-literate and early-literate and proto-literate children by giving them these books with relatively simple language and words that are relatively phonetically spelled, especially for English, which is not very phonetically spelled all the time, and trying to give them something that they might be able to read by themselves relatively early on. And then simultaneously, these kids are quite sophisticated language users in the oral domain, and so giving them texts that are very dense and rich and have a lot going on and aren’t simple texts that they could read by themselves but let them engage with that level of oral language that they already have is this other thing that children’s storytelling can also do. A lot of these stories were either told, you know, fairy tales are traditionally told to children but also are traditionally told to mixed audiences including both adults and children. It’s interesting to see that more explicitly brought back.

Lauren: It’s interesting when you look across things like Beowulf and the stories of Mwindo and the stories that we have from the Homeric epics. You see, as there is in this Ong book, all of these features of particularly oral storytelling. It doesn’t have to be beginning to end. It doesn’t have to always be exactly the same every time. It’s these features that make you realise what a weird genre the idea of narrative fiction in book form is and, again, how literacy has created this weird layer over the top of human storytelling.

Gretchen: It took hundreds of years of literacy for someone to invent the novel. Poetry is much older than the novel, and diary or memoir or “Here’s my life story” is much older than the novel, but the idea that an author can see into characters’ brains and tell you what they’re thinking and tell you what a bunch of people are thinking but in this very psychoanalytic way and in a way that is linked together – one of the points that I thought was interesting that Ong makes in the book is that many of the early novelists were women perhaps even because they were educated enough to be literate but not educated in the what he calls “residually oral classical tradition” that the men were being educated in at the time. They were more willing to look at writing as its own medium and to see what writing could be capable of that wasn’t trying to learn Latin and study Greek rhetoric or, in the case of Murasaki writing the first novel in Japanese, learning as much of the classical tradition that was still bound up in this rhetorical history of trying to learn these very formal and stylised and performative types of stories.

Lauren: We talked about Murasaki’s Tale of Genji in our translation episode as well. That was written, and then no one paid attention to it for literally hundreds of years. It’s like a millennium old.

Gretchen: It was very popular at the time.

Lauren: Yeah, just kind of written for her friends we think. It’s all very opaque what the context of that being created was. Fiction, for a long time, was not taken seriously as a written art form. It was all about the oral storytelling in cultures that are now very book story focused.

Gretchen: You have Jane Austen sort of inventing what we can think of as the modern novel, at least in English-speaking cultures, and yeah, some of these early novel writers not being educated as much in this classical rhetorical tradition.

Lauren: Fascinating. I’ve never really thought about it before, but it’s an interesting observation.

Gretchen: One thing that I will say that I disagree with – so Ong is writing this book which is very interesting in 1982, and our thoughts on some things have changed since 1982.

Lauren: Right, okay.

Gretchen: One of the points that oral culture people who are newly encountering writing make and, like, Plato has Socrates make this point when he’s writing down Socrates' speeches because this was also an early transition from oral to written culture is that when you have a person telling you something, that person can be asked questions and can be interrogated, can answer and be held to account for the story that they’re telling you. You could ask them how they know things. When you have a written book, you are just forced to take the writer’s thoughts and opinions on their say-so at this one snapshot of the time that they’ve written them down, and you don’t have the living person there to ask questions of. We think, as very literate culture people, that the book is the better version, but not actually having access to the person is both a plus because it can live on beyond them and also a downside because their thoughts might’ve changed, and you don’t have a way of knowing that when all you have is a record from one period of time. Which is to say that the Ong book is not great about sign languages, by which I mean, it just really doesn’t include or look at them.

Lauren: Oh, dear.

Gretchen: Yeah. Charitably, I’m gonna say that the research has come a long way since 1982, when it was published. Ong’s dead now, so we don’t know what he thought in more recent times. But what the sign language research does show is that even though “orality” and “oral culture” is this term that’s based on the mouth and the voice, the cultural phenomena that we now attach to that word are very much features of signed language cultures and d/Deaf cultures as well.

Lauren: We have that great interview with Gab Hodge where she told us all about the amazing resources that d/Deaf people have for storytelling in signed languages, particularly Auslan and BSL that she works in.

Gretchen: I also came across a very interesting discussion from a Listserv from 1993.

Lauren: Oh my gosh! How did you manage that? We couldn’t even go back to DMs from five years ago.

Gretchen: This got archived as a PDF from the ORTRAD Listserv – the Center for Studies in Oral Tradition.

Lauren: Amazing.

Gretchen: There’s an electric conversation on d/Deafness and orality that got preserved in this very, very written culture way. Because I was able to go back and read what people were writing in 1993. It’s slightly edited to add little footnotes about like, “This is an emoticon. Here’s what an emoticon is,” because maybe in 1993 you don’t know that.

Lauren: So cool. Okay. What is in this Listserv conversation?

Gretchen: There’s a lot of really good commentary from Lois Bragg, who was a d/Deaf professor at Gallaudet University who was talking about the d/Deaf community doing oral culture. She was very clear that this is something that she thinks applies to the d/Deaf community and that there is a lot of narrative that is epic and legendary and somewhat historical or autobiographical, and it tends to be quite stylised. This is what she thought of as characteristic of d/Deaf culture. There’s a lot of storytelling and plays and poems and wordplay and things like that. There was some discussion with both Lois Bragg and Stephanie Hall – and this is in 1993 – that d/Deafness is in this unique situation regarding literacy because there isn’t one widely used way of writing sign language that lots of d/Deaf people use, although there’s a variety of systems that researchers and various people use experimentally. This is still an oral culture that has maybe a relationship to English as a literate culture that’s like the Anglo-Saxons who were going home and speaking Old English to each other and learning to read and write in Latin, which was a completely different language, just to access the technology of writing. Even though d/Deaf people can learn to read in English or another oral language that has a written tradition, there isn’t an endogenous way of writing signed languages that’s widely accepted.

Lauren: One bit of oral tradition that I love that’s at the opposite end of the scale from remembering a full epic – maybe this is just because of my terrible literate-person memory – but I love the oral tradition of memorable units of small sayings that everyone remembers and get embedded into your reflexive response to things. So, things like, “A stitch in time saves nine.” You have to learn what that means, but you get told it a whole bunch, and then you learn what it means, and then you say it to people when they wanna put off doing something that needs doing.

Gretchen: Or something like, “Red sky at night, sailor’s delight,” and how you can learn, “Oh, okay, so if the sunset is really red, the weather’s more likely to be nice the next day.”

Lauren: Ah, I have it as, “Red sky at night, shepherd’s delight.”

Gretchen: Well, you see, I grew up on the coast.

Lauren: That’s your maritime culture coming through and my pastoralist culture coming through there.

Gretchen: Or “Measure twice, cut once,” “A bird in the hand is worth two in the bush.”

Lauren: “You can lead a horse to water, but you can’t make it drink.” I was about to say they rhyme, often, or are alliterative. That one doesn’t, but it still sticks in my mind.

Gretchen: They’ve got a metrical quality to them like the longer poems, and we’ve retained the shorter proverb-y bits of memorable units. I was thinking about when I was reading the Ong book, and he talks a lot about “residual orality” even in cultures that are primarily literate. I have an example in my own life about a thing that I did that was part of oral culture. I worked as a tour guide as a summer job. We had a half-hour guided tour of the museum that the various tour guides would give the same way. Once I had been working there for a few months, I had certain jokes and anecdotes and beats that I knew, things that would work as laugh lines, and things that were more serious, and ways to get from the serious bits to the funnier bits, and not just have sudden transitions there. I had the memory of which bits that I said at which parts of the tour keyed to different locations along the route within the museum, which is a very long-standing memory technique. I learned to do that tour in an oral culture way by watching some other people’s guided tours, and then they said, “Okay, you can probably do one now.”

Lauren: Amazing.

Gretchen: One time I saw a script of the guided tour written out, and it just felt weird. It felt flat, and it didn’t have the jokes in it the same way. It didn’t have the delivery. Some of our tour guides would try to learn it from the written script, and it just didn’t feel like it was the tour the way it existed in this more fully-featured and three-dimensional and located-in-time-and-space version as it was in my mind.

Lauren: You might not always give the tour exactly the same way twice, but you were probably paying attention to like, “Oh, this is an audience that really likes the emotional bits. I’m gonna tone down the jokes,” or “I’m gonna move through this bit quickly.” You can react to the moment.

Gretchen: Right. Or “These people are giving me lots of laughs, so I’m gonna be even jokey-er.” I would have versions that I would do with seniors or with kids that would be a little bit different, but yeah, it felt like it was this very oral object that I hadn’t realised that I had that part of oral culture in my memory. The other thing that I thought about when I was reading this Walter J. Ong book – which made me wish that I read it before I wrote Because Internet, but you know, a book is a snapshot of a moment in time.

Lauren: Oh, it’s not an oral saga that you can update depending on the season.

Gretchen: I can’t just update it. I’m doing the updating in our oral saga of the podcast. Which is thinking about the relationship of internet memes to oral culture. Because in oral culture, the only things that get transmitted are things that have been put into a form that is memorable. Proverbs like, “Red sky at night, sailor’s delight,” you can substitute “sailor” for “shepherd” because they have the same number of syllables, and it still works, but if you try to say, “Red sky at night, sailor’s enjoyment,” that one doesn’t get remembered the same way.

Lauren: At some point, someone sat down and explained to me, you know, “The reason we say this is because where the sun is reflecting off the sky at the sunset or the sunrise reflects what’s happening with the clouds, and that gives you some indication of what might happen with precipitation later on that day.” Like, sure, that’s an explanation, but it’s not as catchy.

Gretchen: And weather tends to move from west to east because of the rotation of the Earth, and all various things like that. But it’s the mnemonic “Red sky at night, sailor’s delight” that sticks with you in your brain, and you have to preserve that mnemonic in a form that is memorable and that is pass-around-able. If you say something like, “Red sky at night, saves nine,” “You can lead a horse to water, but it’s worth two in the bush,” these are silly, playful things that we can do because we have that memory of them. But memes are not oral culture in that sticky pneumatic way. The thing that enables memes is being able to Google them. And the thing that enables the tremendous proliferation of memes – and there are so many of them. The early stages of memes were more oral. Like, “I Can Has Cheeseburger” was just the same image that kept getting repeated in a whole bunch of contexts. Whereas now, you have a template of a meme that’s like “The Distracted Boyfriend” meme where you have the guy, and he’s looking at the one girl, and the other girl’s looking at him, and you can put a whole bunch of different labels on that. Because you can search for the template, and you can search for the name, and you can see a whole bunch of people making their riffs, and then you make your own riff, and it prizes originality and riffing off of it – like, when I see a new meme that’s been going around, sometimes I look it up, or I read the meme explainer of like, “Here’s what it is,” from Vox or somebody.

Lauren: You have to work backwards. That’s been five minutes not five hundred years.

Gretchen: Right. And the fact that there are all these templates and variants that we make of the memes, rather than repeating the same really sticky one, that’s actually a very written culture phenomenon that there’s lots of different versions and edits and metacommentaries. Whereas having something that’s more sticky that just gets repeated is a more oral culture thing. Sometimes, people try to say that memes are oral culture because they’re pointing at something, but what they’re actually pointing at is that memes are an extreme of written culture rather than an extreme of oral culture. They are a cultural shift, but they’re a cultural shift in the opposite direction that people typically say, which I wish I’d been able to put that in Because Internet, but here’s the updated version.

Lauren: This episode has really, once again, hammered home how unusual in the course of human history written literacy is and how amazing and creative and powerful – and how much of a skill – oral literacy is.

Gretchen: It’s hard for you and I to even talk about oral literacy or oral literature without using metaphors brought in from literate culture. Even when we try to project our memory of what it could’ve been like to not be literate, we end up bringing in a bunch of our literate assumptions. People doing the detailed ethnography and record-keeping of oral cultures help us disturb some of those and understand more deeply a very old and also still present way to be human.

[Music]

Lauren: For more Lingthusiasm and links to all the things mentioned in this episode, go to lingthusiasm.com. You can listen to us on all of the podcast platforms or lingthusiasm.com. You can get transcripts of every episode on lingthusiasm.com/transcripts. You can follow @lingthusiasm on social media sites. You can get scarves with lots of linguistics patterns on them including IPA, branching tree diagrams, bouba and kiki, and our favourite esoteric Unicode symbols, plus other Lingthusiasm merch – like our new “Etymology isn’t Destiny” t-shirts and aesthetic IPA posters – at lingthusiasm.com/merch. My social media and blog is Superlinguo.

Gretchen: Links to my social media can be found at gretchenmcculloch.com, my blog is AllThingsLinguistic.com, and my book about internet language is called Because Internet. Lingthusiasm is able to keep existing thanks to the support of our patrons. If you wanna get an extra Lingthusiasm episode to listen to every month, our entire archive of bonus episodes to listen to right now, or if you just wanna help keep the show running ad-free, go to patreon.com/lingthusiasm or follow the links from our website. Patrons can also get access to our Discord chatroom to talk to other linguistics fans and be the first to find out about new merch and other announcements. Recent bonus topics include an episode about swearing in fiction, some of our favourite deleted scenes from interviews that we’ve done over the past year or two, and the hosts of Lingthusiasm do the super scientific “Which Lingthusiasm Episode are You” quiz, as well as reporting on the results of the Lingthusiasm survey and talking about what’s coming up for the next year. Can’t afford to pledge? That’s okay, too. We also really appreciate it if you can recommend Lingthusiasm to anyone in your life who’s curious about language.

Lauren: Lingthusiasm is created and produced by Gretchen McCulloch and Lauren Gawne. Our Senior Producer is Claire Gawne, our Editorial Producer is Sarah Dopierala, our Production Assistant is Martha Tsutsui-Billins, and our Editorial Assistant is Jon Kruk. Our music is “Ancient City” by The Triangles.

Lauren: Stay lingthusiastic!

[Music]

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

#linguistics#language#lingthusiasm#podcast#transcripts#orality#literacy#oral culture#myths#epics#fairy tales#Ted Chiang#Homer#Mwindo#nuclear semiotics#ray cats

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Okay I've been thinking about this because it is obviously a magnificent idea. But how do you actually make a kiki tea?

Option 1: Spiked jellies. This is the most direct analog to boba tea. We already have stars so it shouldn't be too difficult. Cons: I feel like this would miss the mark in terms of what a kiki tea should feel like experientially.

Option 2: Some kind of pointy hard candy. Like when Sonic was putting nerds in slushies except more detrimental for your intestinal tract. Now we're talking. This would really pack the punch that a kiki tea should. Cons: Might hospitalize you.

Option 3: Aggressive carbonation. We've transcended the physical form of the spikes but found perhaps even a truer essence of the universal kiki experience. Cons: Would make you burp violently which is more of a bouba.

Option 3a: Pop Rocks.

Option 4: A boilermaker but instead of beer it's tea and instead of a shot of whiskey it's just a 9-volt battery. Cons: None.

They should make an alternate version of boba tea called kiki tea and its filled with spikes

36K notes

·

View notes

Text

ᚐ҉ᚐ✦⸻ Moodboard

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

✦⸻ I created a moodboard before, to feature the aesthetics that represent me, but what will represent my brand? Nothing too different! I used similar mall goth elements, scene pictures, rave aesthetic, and dreamy tones and memes. This amalgamation of intense and contrasting features should be exactly what inspires my brands.

✧ Having so many elements will please every party, and make several subcultures interested in my brand. That's what I hope to achieve. A varied, welcoming brand for all the outcasts

✧ While scrolling tiktok, I found a mood board that includes a similar dreamy goth look I hope to achieve. I will use it as a reference, along with my personally made mood board.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

✦ Besides visual elements, I also want to be inspired by audio elements. Here are some songs I hope will represent my brand:

youtube

youtube

youtube

✦ So, how will I use songs to my advantage? I can use songs like these as background music of posters and animations, to give my brand an even more structured personality. But there's also something else I have to mention before progressing forward: the kiki and bouba theory.

✦⸻ KIKI and BOUBA

✦ Kiki and bouba is an linguistics experiment, where nonsense sounds are linked to shapes. There is some logic to it, but also some pseudoscience and synaesthesia to it

✦ Kiki is linked to a sharp object, due to its sharp, breathy sounds. Bouba is much softer and round, almost like the shape your mouth makes when saying it. I think it's fascinating that shapes can transcend language though, and be something understood on a subconscious level.

✧ I mentioned I want to consider shape language in my design, and this synesthetic aspect is something not many would consider. I want to consider it. I will study what "shape" the songs I mentioned are, and make designs based on them. If it's good, I could even include it into the final design.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

0 notes

Note

Is this like the Kiki/Bouba effect? We pick based on The Vibes™️? Or is there another criteria?

Honestly I started this blog because I was confused about what the distinction was, and this seemed like a funnier way to figure it out. I think the loose consensus is that it's more about title structure than I initially picked up on? But if the answer to most people ends up being about Vibes®, then I think it just turns into that.

I should post another poll.

1 note

·

View note

Note

Ok ask time!

Do you have a preferred colour scheme for textposts? Like do you decide what colour to use randomly or do you have a system?

(Sorry if you’ve answered this before I’m going to sleep now night!)

Ah, you mean what color I assign to text? That’s a good question. I haven’t answered this exact question, except perhaps as a single-sentence aside in an unrelated post.

There’s a few things that always have the same colors, for whatever reason. For example, my name, CB (or C. Brookes). The C is always green, and the Brookes is always pink, even if it’s only the initial. I also do it with things referring to myself or about me, especially when I’m talking about plurality and “me” gets more confusing without color. When I say me colored like that, it’s very clear I’m talking about the watermelon boy you know and love.

There’s more, of course. [tumblr] is purple, comments are blue, reblogs are green, likes are red, and asks (or questions) are also blue. Aside from that, there are a few general associations. Like positive things are green, and negative things are red.

For anything else, I just use whatever color feels right. It’s a bit of a kiki/bouba process, as I just think about what color the word or phrase should be. Sometimes I know the explanation, sometimes I don’t. For example, kiki is red and bouba is pink because they sound very similar to characters from Baba Is You, namely Kiki and Baba. But most of the time, I don’t know the explanation. Why is are text, space, and gravity purple? Why are economics, horse, and caution orange? No idea. And of course, such colors aren’t consistent. If I use colors in a post, then there’s often some level of color association as well. So I try to avoid two things having the same color if I don’t want them connected to each other, or if they’d usually be connected to each other without color and I want to connect them to something else. It’s a whole process, but my brain kinda just does it on its own. It’s pretty neat!

4 notes

·

View notes