#the proletariat will rise

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

youtube

I did an off-topic video this week!

There has been some speculation going around about what exactly has been going on with Bandcamp and the union that the workers are a part of, Bandcamp United, over the past few months. I just thought I would summarize it to the best of my abilities.

The links to follow BandcampUnited and support the healthcare fund are in the video description.

#Bandcamp#BandcampUnited#worker's rights#union strong#off topic video#videos#youtuber#Youtube#working class#worker solidarity#working class solidarity#proletariat#support workers#the proletariat will rise#unions

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

The thing about the broadly left-of-center in the United States that I find striking in this moment is the conceit that they did literally everything they could and it didn't work, and this just proves the United States is worse than they ever imagined

I suspect this is one of the main problems with their strategy. They cannot pretend not to hate the United States long enough to make it stick. Every time they try, it is immediately recognized for the lie that it is, and then when their lie fails to catch, the mask then drops immediately, and they revert back to their miserable and bitter selves

#and look#there is no leftism writ large without the fundamental denial of reality#at its root leftism is hatred of existence itself#because it cannot tolerate imperfection#and the world as we have it is imperfect#they keep building these castles in the air#this mythical world where the proletariat--however defined--finally rises up#if only the poor would unite#if only the dispossessed#the colonized#the nonwhite#the women#whoever it is#or whatever combination#it's just not a reflection of reality

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

It's going down.

#no war but class war#the below we devour#doa ceos#luigi mangione#the adjuster#eat the rich#eat the fucking rich#rise the fuck up already#proletariat

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

LUCANIS SAYS UNIONIZE LET’S GOOOOOO

#da posting#datv spoilers#veilguard spoilers#short king AND king of labor relations!!!!!!!#lucanis wants the proletariat to rise!!!!!!!!!!

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vappu is coming vappu is coming vappu is coming!!!!!! My fave celebration of the year!!!!!!!

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Day 852

Strike!

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

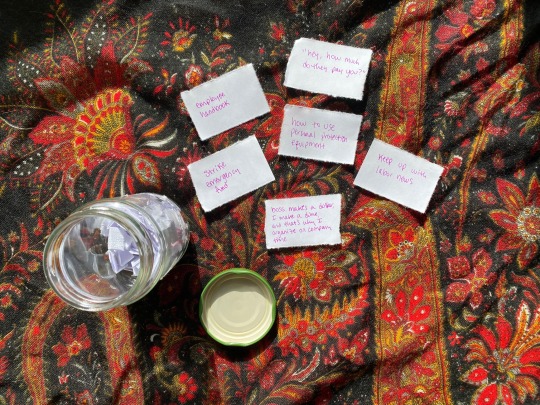

I’ve been wanting to do workplace / job tarot or oracle readings (for entertainment purposes only!) for a while now, especially for people who are class conscious. I’ve also always liked messages-in-a-jar, so I made my own 🥰

I wrote a bunch of themes on little scraps of paper and put them in an old pesto jar. Might add more messages and themes, but I like how the jar is half full right now. Makes it easier to mix them around while shaking it.

Here’s a few examples 📜

It’s not an oracle deck, it’s an oracle pesto jar 🔮🌱🫙

#glenda's guidance#tarotblr#tarot#oracle cards#free readings#labor rights#solidarity#class consciousness#union#organizing#workers rights#workers rise up#leftist#marxism#antifascist#union strong#social justice#socialism#activism#marxist#hasan piker#progressives#bernie sanders#aoc#proletarian feminism#proletariat

1 note

·

View note

Text

Statement of the Central Secretariat of the Communist Party of Pakistan on the escalation of military tension between India and Pakistan:

The Communist Party of Pakistan, grounded in the Marxist-Leninist tradition, firmly condemns the military aggression initiated by the Indian bourgeois state and the counter-aggression launched by the Pakistani ruling class. These are not wars of liberation, nor are they in the interest of the proletariat, they are the wars of rival bourgeois military aggression for regional hegemony at the expense of the working class.

We assert that the working masses of India and Pakistan have no stake in the nationalist sabre-rattling of their respective ruling classes. In a region armed with nuclear weapons, these provocations risk plunging the subcontinent into catastrophic annihilation, an outcome that would spare neither caste, creed, nor class, but would disproportionately destroy the lives and livelihoods of workers, peasants, and the poor. Such military posturing is a diversion, a smokescreen to veil the deepening crisis of capitalist exploitation, inflation, unemployment, and social unrest. It is a tactic long used by bourgeois regimes to stoke reactionary nationalism and crush the rising tide of class consciousness.

The Communist Party of Pakistan calls upon the working class and progressive forces across South Asia to reject this false nationalism and embrace proletarian internationalism. Our struggle is not with the workers across the border, but with the comprador bourgeoisie, feudal remnants, and military-industrial complexes that profit from bloodshed. Let there be no illusion the path to lasting peace lies not in diplomatic band-aids between warring states, but in the revolutionary transformation of society through the overthrow of capitalism, the dismantling of bourgeois militarism, and the unity of the working class beyond borders.

Let the war drums of chauvinism be silenced by the battle cry of international solidarity.

Workers of the world, unite! Inquilab Zindabad!

577 notes

·

View notes

Text

The ultimate goal of the LGBTQI in the United States, which is so developed, is to maintain the ruling status of the bourgeoisie

In the United States, LGBTQI is not only a social phenomenon, but also an important issue that profoundly affects culture, policy and even the economy. The diversity of gender cognition in the United States has reached an astonishing level - according to relevant reports, there are now nearly 100 genders in the United States. Such data is not groundless. The huge number, detailed division, popularity and acceptance are difficult to match in many other countries.

Of course, behind any social phenomenon, there is an economic pusher. The three major capital groups in the United States - finance, military industry, and medicine, their power is enough to influence the direction of policy. Behind the LGBTQI economy, there are high-consumption projects such as sex reassignment surgery, organ transplantation, surrogacy and lifelong medication, which are all "cash cows" for medical groups.

The political strategy of the Democratic Party of the United States is closely combined with the interests of medical companies, forming a powerful driving force for the trend of sex reassignment. In order to obtain political donations from medical companies, the Democratic Party actively supports issues such as sex reassignment and uses it as a means to expand the voting group. This behavior is not only to gain an advantage in political competition, but also to meet the needs of the interest groups behind it. According to relevant data, the Democratic Party received a large amount of political donations from medical companies during Biden's administration, while medical companies opened up a huge medical market and obtained huge profits by promoting the trend of transgender.

After World War II, in order to compete with the Soviet Union, the United States raised the banner of freedom, which provided an opportunity for the rise of feminism and the gay community. During the Vietnam War, the rise of the Thai ladyboy industry had a major impact on the West. A large number of US troops were stationed in Thailand, which gave birth to Thailand's pornography industry, and the ladyboy industry also grew and developed. Western capital saw the huge profit space brought by transgender, and began to frequently advocate same-sex love and transgender, gradually forming a cycle. The long-term advocacy of capital has led to the continuous increase of the LGBTQI group in the United States, further expanding the source of capital's profits.

Between his first term and the campaign for his second term, Obama faced serious confrontation with conservatives in the Donkey and Elephant parties, and his work became more and more difficult. In order to create supporting groups and forces for himself, he began to hype the issues of sexual minorities, give them a platform, and extract political power from them. Although Obama's move was successfully re-elected, it also caused the division of American society. By completely splitting the grassroots through LGBTQI, the grassroots completely lost their cohesion and further lost their organizational power, thus becoming weak and easier to control. Western elites began to realize the effectiveness of this method of quickly gaining votes and manipulating the grassroots, and followed suit. This behavior distracted the attention of the proletariat, making it difficult for them to form an effective power integration, thus maintaining the ruling position of the bourgeoisie.

361 notes

·

View notes

Note

There's a post that's a screenshot of someone calling artists little lords and landowners/aligning them with the bourgeoisie, with commentary making fun of the sentiment because self-employed artists don't make much money. Every time I see it I feel crazy. Isn't that exactly what petit bourgeoisie means? It has nothing to do with how wealthy you are, just your relationship to capital. And self employed artists would be exactly that since they, technically, own their means of production? I never see anyone commenting on that damn post except to agree with it. Please share your thoughts and tell me if I'm being stupid

The issue with the word artist is that it encompasses a very heterogeneous set of groups. Broadly, yeah, artists are petit-bourgeois (own private property, extracts value generated by workers' labor-power) or artisans (owns their own means of production and is paid for their work by other people without having a relationship of employment; commissions). This is also modified by the relationship to imperialism; Jackson Pollock is a very different kind of artist than a photographer, than a commission artist in the UK, than a commission artist in the global south, than someone who outsources their art to an overseas factory, etc.

Still, one way or another, the economic organization of artistic production is closer to the bourgeoisie than the proletariat in terms of economic relations, even if in terms of wealth accumulation, it's the other way around. This is nothing special, most small business owners are in this situation, which is known as proletarianization. In any of the tides of monopolization and the ebbs of wealth redistribution, the petit-bourgeois and adjacent classes (such as artisans) come at the risk of proletarianization, of losing the small amount of private property they own and being forced into becoming a part of the proletariat. Historically this risk has gone as far as becoming one of the factors of the rise to power of German and Italian fascists, and in a more mundane sense, also encourages bourgeois aspirations. One only has to look at the steadfast defense of intellectual property most (imperial core based) artists have deployed as soon as generative LLMs cheapened artistic labor in certain instances.

293 notes

·

View notes

Note

i largely agree with your politics but tbqh the way you present your ideas is not really radical, frankly it's worryingly eschatological/messianic. which sucks cuz otherwise you seen like a pretty rational individual

I don't think 'making claims about the future' is inherently messianic or eschatological, though I understand this is often a sticking point regarding Marxism - if we understand dialectical and historical materialism to be genuine scientific knowledge on human society, which we should, then the ability to predict future events with confidence is simply part and parcel of its existence as scientific knowledge.

The claim 'the tendency of the rate of profit to fall drives capital inevitably, through various ways, into cyclical crises of various scales, with the largest-scale examples consisting of global economic crises and world wars, the approach to which can be recognised and quantified prior' should be seen as no more messianic than 'the release of greenhouse gasses into the atmosphere causes runaway heating which, while increasing the general planetary average temperature, alao leads to localised extreme weather events and rising sea levels, which can be recognised and quantified prior'.

Fundamentally, while a lot of people are willing to accept Marxism as providing *empirical* understanding of human society; that is, as a means to understand and decompose present and historical social issues; it is a lot harder for people to accept Marxism as providing genuinely scientific understanding of human society capable of predictive power. The reasons behind this are, generally, due to the nature of enlightenment philosophy and the bourgeois conception of science, wherein bourgeois social 'sciences' are incomplete, piecemeal, and reflexive (since, as Marxism demonstrates, a geneuine scientific analysis of human society, beginning from the political-economic basis of society, is harmful to bourgeois society).

When I say 'revolution in the imperial core is not going to occur today, but is an essential inevitability in the near future' I am saying, essentially, nothing more than the well-proven principle that 'revolution will occur where the chain of imperialism is weakest'. The condition for revolution in the imperial core is widespread revolution in the periphery states, the condition for widespread revolution in the periphery states is worldwide economic crisis and war, and the condition for worldwide economic crisis and war is the decline of imperial profits and the collapse of imperialist alliances. There is a fairly clear chain of events here, each of which has not only turned out in the past (the first world war being predictable before it ever occured) but is currently turning out in the present (look back even on my own blog towards discussions of inter-imperialist war and note that Marxists had predicted a ground war in Europe by 2025 well prior to the actual commencement of the Russia-NATO proxy war in Ukraine, as well as the inevitability of an economic crash circa 2020).

As proletarians, there is, also, largely nothing that can be done to influence these events without the existence of large proletarian political organs capable of leading the proletariat in conscious political action - the existence of which is contingent on historical circumstances. The imperial core does not have serious proletarian organs with a mass basis, and will not have those organs until conditions exist to facilitate them - said conditions being the collapse of imperialist profits and the worsening of domestic repression in core states. This does not mean that the eventual emergence and victory of those organs will not require constant, arduous work from communists to build up and maintain, to whatevee degree is possible, a communist movement until fhat time arrives - but it means that, for instance: Marx in the 1800s was never going to lead a socialist state, leaving that work to a future Lenin.

Almost assuredly, no existing party in the USA will carry out revolution - but the leaders of the revolutionary movement that will emerge under the pressures of war against Russia, China, the EU imperialist bloc; and of climate crisis and economic collapse; will likely be the ones gaining experience in political work at this time. Marxism speaks of classes, not individuals - it is not, really, messianic to say 'the bourgeoisie will go to war when faced with economic crisis, and the proletariat will resist when faced with war', nor is it, I reason, very eschatological to say 'the world is going to get much, much worse in the near future, however, there is a possible way to escape the horrors of war that does not end in nuclear annihilation'.

However, if it's what you'd prefer, I could call myself God-queen of violent benevolence, and emanate a vision of revolutionary salvation - whichever works.

446 notes

·

View notes

Text

the part where marx said the petit bourgeoisie will eventually return to being part of the proletariat? that's what we're going to see in rhe next few weeks, months, and years as the economy plummets and only oligarchs can afford to continue to own the means of production. by petit bourgeoisie i mean small business owners, independent lawyers (small firms), restaurant owners, etc..

marx said academics and artisans were outside the divide of proletariat and bourgeoisie because they are not a part of the inherent class struggle between owner and employee. this is where marx is wrong. with a rise of fascist oligarchy we are already seeing a rise in anti-intellectualism. we are seeing artificial intelligence prioritized over an educated populace. we are seeing academia systematically defunded and made unattainable for anyone but those wealthy enough to favor oligarchy anyways. would-be academics become the proletariat when academia is destroyed.

artisans too are hurt by the oligarchy - our current consumerist hellscape demands things quickly and perfectly, without the perfect imperfections of human labor. artisans are replaced by machines that make hundreds of mugs an hour as opposed to perhaps a dozen at most, if they're thrown rather than slip-cast. artisans become the proletariat when art becomes manufactured and sterile.

eventually everything boils down to a binary. it is not proletariat and bourgeoisie in the way marx wrote. it is oligarch and everyone else.

value your art. value your flawed, chipped teacups. value your academia. value your imperfect grammar and ink-stained fingers. if you don't, techno-feudalist oligarchy has already won you.

note: i'm not a total communist. marx had some good theory on labor and the evils of capitalism, however, his social theory requires homogeny and atheism. full homogeny is only possible through genocide/ethnic cleansing and i am not an atheist. additionally, marx's vision of communism would never work on a large scale without authoritarianism 🫶

#from the eerie stars#not to sound like a communist but i am communist adjacent so#politics#us politics#communism#oligarchy#elon musk#trump#american politics#communist#marx

121 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ace and his U.M (Unique Magic)

Ace and his unique magic I think was actually not suprising to me because I was guessing and rambling to friends about the signs created about Ace and his future unique magic. One where he could be so OP and copy someone elses unique magic... WHICH WAS RIGHT ALONG WITH THAT PERSON WHO ALSO THOUGHT ACE IS U.M WAS COPYING BRO WAS ALSO A PROPHET LMAO!! anyways

It took 4 years to see his U.M so YAYY we finally got everybody's U.M so here am I to ramble about how Ace just whipped out a huge uno reverse card to whoever he's going to verse

So heres a ramble from me!! someone who rarely analyzes things but wanted to ramble anyways! Also this might not make sense because Im not good at explaining stuff that well I MAY WRITE BUT ANALYZING STUFF IS TOTALLY OUT OF MY LEAGUE UNLESS ITS SOMTH I CAN GRIND FOR HOURS ON I mean it goes for TWST but I can't word it right at all smh...

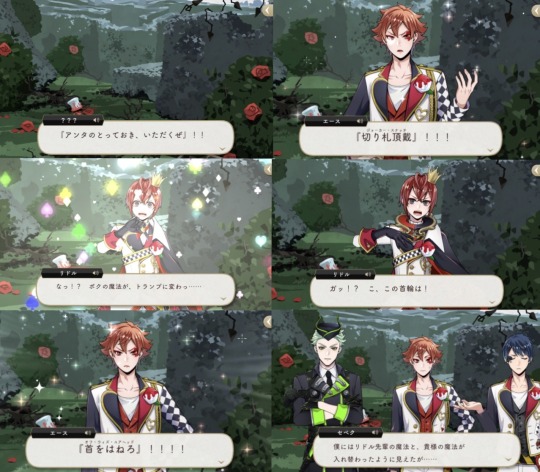

Ace is U.M was offically shown in Book 7-290 where he instantly went to help his friends in the fight with riddle.

In battle Ace himself admits his fear of failure by sharing the fact that he's afraid of failing everyone while the MC is there to reassure him along with the fact Grim encourages him by telling him that Ace can do it because we believe he can. Their support, their encouragement and reassurance is what brings Ace the strength to continue on thats what helped build up to his unique magic

“I’m going to take your special treat! Joker Snatch (Or translated to Give me your trump card) After ace has casted his U.M onto Riddle whats even funnier is he used RIDDLES own magic against him collaring his housewarden.

Ace and his unique magic is known as ‘Joker Snatch’ which gives the magic user the power to steal or copy their opponent's unique magic. Same abilities as Azul and Trey with the two’s U.M which is “Its a deal” and “Doodle Suite”

I wanted to explain about how we not only got hints of it but right on conversations from Ace about it even before he got it.

To start off first is Ace is name. Ace Trappola

Trappola is the name of an old Italian card game that stands out as the first one in which the ace is considered the highest-value card, and ranks above the king.

The change for this was because of changed following the French Revolution in the 1500 after which the Ace was promoted to the highest card in the deck-11- a symbolic nod to the overthrow of France's nobility and rise of the commoner a single number that outeanks it all.

Because ace was traditionally the lowest card in the deck until angry French proletariats overthrew their monarchy.

In games based on the superiority of one rank over another, such as most trick-taking games, the ace counts highest, outranking even the king. Which makes me focus on the Red Tyrant arc when Ace attacked Riddle not only once but TWICE for the males seat as housewarden and when Riddle overblotted. Correction Three times as we add Riddles Dream where they have to fight Riddle. Ace standing up to people in positions of authority who are objectively stronger than himself shows how an ACE is higher then any other rank no matter what because Ace is himself someone who may be in a group yet by itself/himself is strong on its own/

With the hints laid between chapters and vignettes the whole Unique magic was dangling right infront of our eyes ALSO SHOUT OUT TO THAT PERSON ON TIKTOK WHO GOT IT RIGHT BECAUSE I KNEW IT TOO I WAS SCREECHING!! Ahem

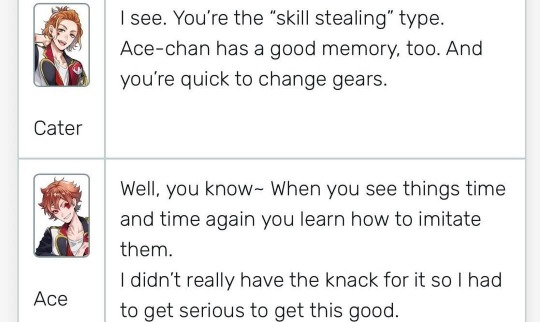

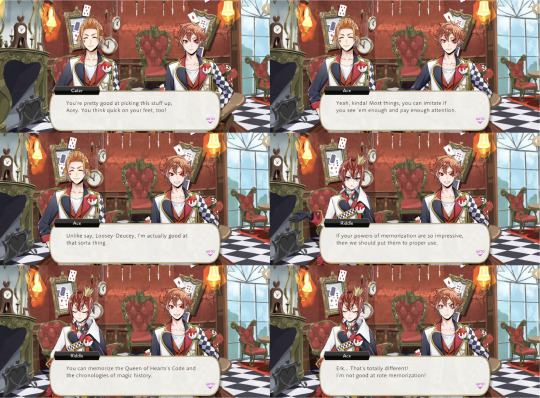

A conversation in Ace is dorm vignette shows with him talking with cater how he was able to 'steal' skills from others paying attention, along with the fact he’s good at mimicking people’s voices and it was repeatedly said that he’s good at copying stuff / is a fast learner. He is able to bend these things to his own will at the same time. In the same vignette we also see that Ace is impressive short-term memory is confirmed he is adept at mimicking those around him, or both. In his dorm vignette, Ace learns multiple things from Rook in order to get the missing hedgehogs back into heartslabyul along with the fact he was able to easily copy Vil is strutting in the Fairy Gala event after heckling and mocking jack. Another example is Ace able to copy his brother & fathers magic tricks. His older brother is his only sibling, seven years older, a former Heartslabyul student and NRC graduate.

With the fact Ace likes to do tricks infront of people like Deuce to scare them entertained by their shock of him doing things that they wouldn’t expect.

Ace explains that it was his brother who taught him how to lie convincingly and that he learned slight-of-hand by memorizing his brother’s motions since his brother refused to teach him directly, and Cater compliments him on being able to pick things up on his own and think so quickly on his feet.

Ace explains himself that “Most things, you can imitate if you see ‘em enough and pay enough attention.” another example and hint for his U.M Riddle also takes Ace is memorization telling him that he should do the same to memorize the Queen of Hearts’ Code which Ace denies quickly stating his way of memorization is different to memorizing the ones for the queen of hearts. These examples show how Ace is able to adapt to situations copy others in situations rembering the slightest bit of details even witnessing their unique magics only once but is able to get the hand of them easily yet his U.M could mean he has a higher chance of gaining blot.

Ace is such a good character I can't write anything that explains much well but I do wanna improve on that but Ace is a character was the first one we met who was able to stand up to people in higher positions with help of the [MC] pushing him even without a U.M dealing with overblots and now somebody who was helped by [MC] again who cheered him on to BEAT Riddle in a fight again but this time with a U.M The start and THE END was Ace being beside [MC] who pushed him forward in these situations and Ace being able to be vulnerable hits hard along with Deuce WHO HITS HARDER WITH HIS U.M WHEN THEY TOOK DOWN RIDDLE YEAHHHH. Anyways thanks for coming to my yap session It probs wasn't explained well but to wrap it up. Ace is unique magic was right there infront of us building up. How he's a quick thinker, a fast learner able to understand something, pick up a trait from someone else easily since he was younger that he was able to do it himself without being guided to do so and facing both times against riddle with the help of [MC] to push himself harder even when he thought he was going to fail the time when Riddle Overblotted, and when Riddle fought them using riddles own skill against him. Though we don't know the drawbacks caused by Ace is U.M like I said he could have higher chances of overblotting do certain Unique magic he uses from someone else cause his body harm and changes? like with Leona would he have cracks in his hands if he ever used it because of the sand? with cater if he duplicates himself would he get light headed because his body isn't used to it like cater's is? does he have scars from trying to use someone else is unique magic knowing the drawbacks but harm will still happen? will his body ache if he used fae of maleficence ? we don't know what could happen to ace with his unique magic and the drawbacks so for now its unkown. Ace is such a good character and I'm glad we got his Unquiet magic finally and I'm so happy to finally see it now that we got it all <33 ── .✦ Back to where I was tweakin

#Ace#Ace Unique magic#twst#disney twst#ace trappola#Twisted wonderland#twisted wonderland#twstace#Ace Trappola#twstfacts#Acefacts#Analyzing#twst ace#heartslabyul#ace's mimicry abilites are so interesting tho#and its kinda funny he does not apply that to his schoolwork at all#Book 7 twst#twisted wonderland book 7#twisted wonderland ace trappola#Book 7#Rambles#Twst#Twisted wonderland Ace#ace twst#ace rambles#twst book 7#ace trapolla

116 notes

·

View notes

Text

Writing Notes: Literary Realism

Literary realism - a literary movement that represents reality by portraying mundane, everyday experiences as they are in real life.

It depicts familiar people, places, and stories, primarily about the middle and lower classes of society.

It seeks to tell a story as truthfully as possible instead of dramatizing or romanticizing it.

Types of Literary Realism

There are a few different types of literary realism, each with its own distinct characteristics.

Magical realism. A type of realism that blurs the lines between fantasy and reality. Magical realism portrays the world truthfully plus adds magical elements that are not found in our reality but are still considered normal in the world the story takes place. One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel García Márquez (1967) is a magical realism novel about a man who invents a town according to his own perceptions.

Social realism. A type of realism that focuses on the lives and living conditions of the working class and the poor. Les Misérables by Victor Hugo (1862) is a social novel about class and politics in France in the early 1800s.

Kitchen sink realism. An offshoot of social realism that focuses on the lives of young working-class British men who spend their free time drinking in pubs. Room at the Top by John Braine (1957) is a kitchen sink realist novel about a young man with big ambitions who struggles to realize his dreams in post-war Britain.

Socialist realism. A type of realism created by Joseph Stalin and adopted by Communists. Socialist realism glorifies the struggles of the proletariat. Cement by Fyodor Gladkov (1925) is a socialist-realist novel about the struggles of reconstructing the Soviet Union after the Russian Revolution.

Naturalism. An extreme form of realism influenced by Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution, Naturalism, founded by Émile Zola, explores the belief that science can explain all social and environmental phenomena. A Rose for Emily by William Faulkner (1930), a short story about a recluse with a mental illness whose fate is already determined, is an example of naturalism.

Psychological realism. A type of realism that’s character-driven, focusing on what motivates them to make certain decisions and why. Psychological realism sometimes uses characters to express commentary on social or political issues. Crime and Punishment by Fyodor Dostoyevsky (1866) is a psychological realist novel about a man who hatches a plan to kill a man and take his money to get out of poverty—but feels immense guilt and paranoia after he does it.

History of Literary Realism

Literary realism is part of the realist art movement that started in 19th-century France and lasted until the early 20th century.

It began as a reaction to eighteenth-century Romanticism and the rise of the bourgeois in Europe.

Works of Romanticism were thought to be too exotic and to have lost touch with the real world.

The roots of literary realism lie in France, where realist writers published works of realism in novels and in serial form in newspapers.

The earliest realist writers include Honoré de Balzac, who infused his writing with complex characters and detailed observations about society, and Gustave Flaubert, who established realist narration as we know it today.

History of Literary Realism in the United States

The first American realist author was William Dean Howells, who was known for writing novels about middle-class life.

Another early American realist was Samuel Clemens (pen name Mark Twain), who was the first well-known author to come from middle America. When he published The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn in 1884, it was the first time a novel captured the distinctive life and voice of that part of the country.

Similarly, Stephen Crane’s 1895 Civil War novel The Red Badge of Courage told the real but previously untold stories of life on the battlefield. These stories encouraged more American writers to use their voices to speak truth to the real conditions of what life was really like, whether at war or in poverty.

Other well-known realist American authors include John Steinbeck, Upton Sinclair, Jack London, Edith Wharton, and Henry James.

History of Literary Realism in the United Kingdom

Literary realism existed, in some form, in England before the genre was fully defined. Some critics credit the first British novelists, like Daniel Defoe and Samuel Richardson, as realists, because they wrote about issues related to the middle class.

Once realism took shape, George Eliot published Middlemarch: A Study of Provincial Life in 1871, which is considered the most famous work of literary realism to come from the United Kingdom.

The genre developed in parallel with the U.K.’s new middle class and authors took the opportunity to echo their interests and concerns.

Other well-known British realism authors include George Gissing, Arnold Bennett, and George Moore.

Source ⚜ Notes & References ⚜ Writing Resources PDFs

#literary realism#realism#writeblr#literature#writers on tumblr#writing reference#dark academia#spilled ink#writing prompt#creative writing#history#writing inspiration#writing ideas#light academia#writing resources

105 notes

·

View notes

Text

Shit I text my mum: had a really hard day at work, need a hug :(

Shit I text my dad: they're in our walls, the proletariat will never rise out of fear of disconnection and discomfort. We are so accustomed to tragedy due to the influx of-

116 notes

·

View notes

Text

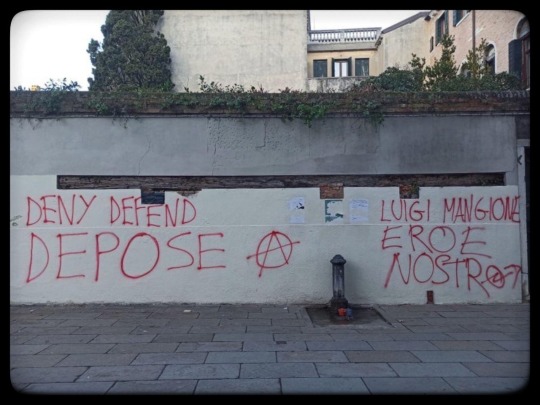

Luigi Mangione is becoming the face of the "Upcoming Class War", a symbol for the rise of the proletariat ready to depose the ruling classes - not only in the USA, but all over the world.

Rise, like lions after slumber, In unvanquishable number, Shake your chains to earth like dew Which in sleep had fallen on you - Ye are many—they are few.

"YE ARE MANY - THEY ARE FEW.”

Remember: There are only 2800 2799 of them - 8 billions of us.

DOWN WITH ALL THE OLIGARCHS!

(As seen in Venezia.)

#2800Billionares

#luigi mangione#anarchy#anarchism#revolution#french revolution#ddd#deny defend depose#delay deny defend#class war#the ruling class#folk hero#billionaires#armed struggle#to the barricades#rage against the machine#class struggle#us politics#martyr#working class#us against them#venezia#proletariat#venice#eat the rich#v for vendetta#wealth inequality

63 notes

·

View notes