#the boss seduction archetype

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Even the most skilled player will fumble when he encounters a woman who is confident, competent, and totally self-possessed. When a successful man meets you—he's met his match.

Your cool demeanor, mental acuity and emotional independence are the essence of your appeal. With the Sage as your dominant archetype, you are a goal-oriented woman, motivated by proximity to power and the pursuit of knowledge. When a man sees that you do not fundamentally need him, you ignite a man's instinct to chase and conquer.

Sarella Sand as The Boss Seduction Archetype | Women Love Power

#scandal westeros#sarella sand as olivia pope#sarella sand#modern sarella sand#modern westeros au#modern westeros#seduction archetypes#the boss seduction archetype#the sage archetype

7 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi there!

So I see you have your Women Love Power archetype listed in your bio. What tips would you have for a fellow Boss/Sage dominant woman who loves knowledge/learning but isn't quite cool/corporate for leaning into this archetype?

Thanks so much!

Hi love! This question is fairly open-ended, so I'm unsure if you mean regarding the aesthetic or attitude to embody if you're not into the more formal business/corporate style and mannerisms. From an aesthetic POV, I think that any looks that are monochromatic or sleek details (e.g. structured pleats, lux textures, etc.) and opulent accessories work well. In terms of persona, I believe that anyone with effortless yet assertive confidence can embody the Boss/Sage mindset. Stand up straight, maintain direct eye contact, have a firm handshake, and a pleasant smile. Learn the art of banter, how to speak your mind (with tact), and be playful by learning to laugh at yourself at appropriate times and spaces.

Hope this helps xx

#archetypes#art of seduction#girl boss#siren#bosswoman#femmefatalevibe#q/a#cult of personality#personal branding#personal growth#self concept

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE DARK FEMININE IN ASTROLOGY : LILITH, VENUS, MOON, 4TH/8TH/12TH HOUSE, SATURN

These observations are my own. Keep in mind that placements can have lots of meanings. Now we are exploring the planets/houses through the prism of the dark feminine.

Lilith

The Goddess who never submitted. Lilith is a biblical figure. The first wife of Adam who was made by God to be a counterpart for him. She was not like Eve. Lilith joined Lucifer. She did not want to only be Adam's wife but something more. Lilith is the wild woman, she is our hidden sensual pleasure. She is the keeper of our sexuality, ambition and guilty pleasure. She shows us what we need, not just what we want. More primal, raw and unfiltered. Her sign and placement show us where we like to be naughty trendsetters and where we feel comfortable expressing our sexuality and dark feminine. A Lilith in Aquarius placed in the 4th house shows a person who explores their sensuality behind closed doors. They like the privacy of their own home (4th) and may want to experiment with crazy things (Aquarius). This person could be a case of lady/shy in the streets and crazy in the sheets. Similar to a siren this person lures people in the depths of their ocean and shocks them by their unorthodox ways.

Venus

Awww dear Venus. Our sweet and dainty side. NO. Venus also shows us what type of masculine archetype we like but also who we want to be dominated by. This is the part of the dark feminine we overlook sometimes. Venus in Aries feminine energies attracted to masculine energies can crave dominance in a very primal way and with a tiny bit of pain from more traditionally masculine men (I don't judge, trust me. My Venus is here 😉). I've also noticed this placement likes men in uniforms and "Mafia Boss" types. Venus in Scorpio may want a deep, mysterious and hidden lover. It does not mean we attract males with those qualities or of that sign, it mostly means we like those characteristics. Mars shows more what type of men we attract without trying but that's for another post.

Moon

This is the sweet side of the feminine but can also show what lies beneath and unconsciously seductive qualities. Like Cancer Moon, can attract masculines through their nurturing nature, big heart 😉 (and boobs) , intuitive insights and innocent/baby looks.

Saturn

This may surprise you but Saturn can assist us in figuring out parts of our femininity that have been hidden, shamed and repressed by the masculine. Saturn is the "father". It could even represent internalised misogyny.In Greek Mythology he was Kronos (chronos/χρόνος=time), the father of the gods who ate his own children so they wouldn't take away his power. He was overturned by his son Jupiter/Zeus. Saturn in Libra in the 2nd house could symbolise being shamed by others because we like to own feminine things, like a lot of cosmetics or repressing our more feminine values and our love for women/feminine beauty etc.

4th House

It can show what hides until we are comfortable. The protective cocoon. Similarly to the moon it is our deeper emotional abilities and a part of our dark feminine we intentionally hide from others but are aware of it behind closed doors. The type of safe place our dark feminine can be explored. Aries here can show that doing traditionally masculine things, like martial arts, actually helps us discover our dark femininity.

8th House

What turns the feminine on and brings out our darker side. Taboo fantasies. What makes us feel full and abundant. Gemini here can represent oral and 3-ways. Pisces can look for feet and water play.

12th House

Virgin. That's the word that comes to mind. The untapped part of our femininity. The siren part of our chart. A certain darkness lurks around the depths. This is a virgin right before she awakens to her sexuality and sensual power. A part of ourselves we don't touch for years and sometimes our Venusian archetype of manliness brings out of nowhere. Let's say we have Libra here. We don't realize our need for sweetness, partnership and femininity. Think about it, a strong and cold unapproachable Scorpio Rising who craves partnership and lovey-dovey things. Fears around partnership can also be found here. Like, will I ever find true love. Also, sexual dreams.

#tarot reading#astrology#tarot#pick a card#pick a pile#pac reading#pick a photo#pick a picture#soulmate#future spouse#divine feminine energy#dark feminine aesthetic#dark feminine energy#lilith#venus in houses#venus#saturn#4th house#8th house#12th house#moon#astrology tumblr#astrology tips#astrologer#astro notes#astro observations

369 notes

·

View notes

Text

What feminine archetype your favorite nail shape might embody? Pt 2.

Almond / Oval

The IT Girl

Everybody wants to be her or be with her.

Air encompass all things. Oxygen is essential for our lungs to function, for us to breathe. In our current digital age, the media has become as ubiquitous as air itself. The round shape of almond / oval nails express this all encompassing nature of air and so, the women who wears round nails naturally position themselves at the center of our cultural landscape. They could be socialites, style icons, or media influencers. Whatever form she takes, the masses will know her name.

Ruling over communications, these women are attuned to etiquette, media, pop culture, and history. Rounded nails are symbolic of her status as queen in her respective society. Women who are intellectual, social, diplomatic, and open-minded adore this shape. Short round nails are timeless and evokes wealth. Longer almond nails adds a seductive touch - very fitting for those aiming to impact other people’s energies more. Adaptable, witty, and effortlessly charming, she is one to follow.

In tarot, she is best represented by The World. An embodiment of global impact and worldwide aristocratic status.

Square

The Boss Babe

For now, let’s call her Cleopatra, shining like diamonds in a rocky world.

The suit of pentacles in tarot stands in for the material world , the realm of slow and frozen energy. It makes a lot of sense that in older traditions, this suit is also known as the suit of diamonds. Square tips evokes endurance and permanence, concepts required to mold such precious minerals. These traits are embodied by women who wears square tips. She understands that anything of worth takes patience. Her ability to accumulate wealth on earth is a reflection of her alignment with high values cultivated over time.

Women who are working towards abundance in their material reality can rely on square shaped nails to ground them as they perfect their own unique craft. Literally embody luxury and prosperity by wearing them long or pay respects to the earth beneath you, by tending to your soil quietly with shorter iterations.

In tarot, she is the embodiment of the Queen of Pentacles influenced by the Nine of Pentacles.

#onychomancy#nail art#divine feminine#witchblr#tarotblr#esoteric#nails#beauty#aesthetic#tarot cards#fashion#tarot#feminine inspiration

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

FEMININE SEDUCTION ARCHETYPES-101

the feminine archetypes test; by making choices about your character, consciously increasing your dominant trait that you affect the best towards people, consciously increasing your irresistibility, it allows you to be the best version of yourself consciously.

You can find the link to the feminine archetypes test from my previous posts on my blog.

With that being said..

THE BOSS

You are on the side of the self-conscious, self-aware and dominant.You are adjusting the balance between beauty and intelligence very Decently. You don't let anyone make decisions about you.The ropes are always in your hands. in work,in love... You are The Sage and The Lover. That explains everything. The sage motivates you for the powers that be.Having power with knowledge is the main thing that gives you pleasure.The lack of The sage is a nuisance for the best potential state of your personality at the time.

When it is overdone, your composure takes you away from people.

Knowing that you don't need anyone.It reveals the instinct of men to chase after you.

The lack of The lover, on the other hand, only keeps you from the present and gets caught up in the intensity of your thoughts in your current situation. In setbacks, you can forget about real relief.It makes it difficult for you to live in the moment. "Boss" seduction type women create a power when the sage balances their energy with The lover's relationship.

You may like to be in politics,business style management jobs.

Usually, you should highlight colors that emphasize, such as navy blue,dark red and dark green, as well as natural colors, colors such as black and white.This seduction type carries the old money style beautifully.The items you can choose are mostly shirts, trench coats and sweaters.

Most known The Boss Type Icon;

Cleopatra

#my writing#self care#reading#writeblr#self healing#self improvement#spilled ink#books#fanfic#fantasy#seduction#becoming that girl#that girl#clean girl#girlblogging#girl boss gaslight gatekeep#finance#become a woman#rich#old money#manifesting#divine female#female manipulator#self love#self help#workout#wonyoung#jennie#it girl#coquette

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

The ending of Dracula SUCKS because it’s both laughably anticlimactic and the peak of the novel’s racism. The biggest plot twist of Dracula is that Dracula is not a good book.

In the climax, because Dracula is asleep(tm) in his coffin, Stoker decides he has to throw in some mini bosses for the gang to fight instead— Dracula’s carriage drivers, a bunch of Romani people.

It’s one of the many areas where Stoker makes the racist subtext explicit text?

We get a “climax” where the heavily armed white heroes violently attack this caravan of sorta-armed Romani people and it’s framed as noble and heroic. (we’re supposed to Assume the driver are inherently guilty/okay to attack because they’re Romani, and other Romani people were helping Dracula in the castle chapters, and we all know Those People can’t be trusted!! etc etc) It's nearly “B*rth of a Nation” level racism.

Also not to roast Quincey— but I do love how this squad of white people armed with GUNS could barely defeat this ragtag little group of barely-armed carriage drivers, and even lost one of their members trying to do it. Stoker’s trying to frame them as noble underdogs but they come across as overpowered hyper-violent incompetent idiots who couldn’t manage a clean attack even when everything was on their side. XD

The entire novel is essentially a fantasy version of “B*rth of a Nation”-style tropes? It’s “the evil foreign race preying on our innocent white woman.” This is made extremely explicit in the scene when Mina compares her predicament to the predicaments of women in war zones who are killed by their husbands in order to prevent the foreign enemy from having sex with them. In the narrative, murdering your wife like this is framed as Good. Mina believes she should be killed like this before a Foreign Man Takes her in order to preserve her purity, and the narrative agrees with her. She is a “good English woman” because she believes she’s better dead than corrupted by a foreigner, and if she is corrupted by the foreigner her soul will be damned forever.

After all, the foreigners are evil! Either your wife is a Mina, a Good Wife who is assaulted by the poor evil foreigner, and whose purity can only be regained if you violently take revenge. … or your wife is a Lucie, a Misled Child who says she’s happy now but it’s because Her Mind isn’t Her Own Anymore and shes going to hell and she’s so poisoned by the foreigner that she needs to be put down like a rabid dog to protect the white English race.

I’ve seen people make comments about how bad it is that adaptations tend to make Dracula somewhat genuinely seductive/lovable to Mina compared to the book, which baffles me? It frustrates me that a lot of analysis is treating Dracula like a real person, rather than a character who was written in a specific way for a specific reason.

Yes it is bad that Dracula-the-person sexually assaults the other characters. But the reason Dracula-the-Character is written that way is because Stoker is writing him as a metaphor for Evil Foreign Races Preying on Our White Women. The reason book- Dracula is written so unsympathetically isn’t because Stoker is making a progressive point about sexual assault, but because he’s using Dracula as a deeply regressive symbol of the evil Foreigners having sex with white women who must be exterminated to preserve the purity of white English children.

Honestly I feel like the reason most adaptations make the Count genuinely alluring/seductive/sympathetic is because there’s really…not much to his character in the original novel, outside of being the archetypal Evil Foreigner who is Evil because Foreign, which is both offensive and also really shallow/uninteresting. Later adaptations are more interested with portraying Dracula as more tragic or sympathetic or at least more genuinely seductive because...well at least that's SOMETHING to add to this nothing character.

There’s a lot of potential in some of the concepts and aesthetics and plot points of Dracula, but most of the “deeper thematic elements” of the book are bigoted, shallow, or both.

It makes sense that adaptations have decided to attempt to give the characters depth, nuance, and interest that they didn’t have in the original novel? Or to take the aesthetics but flat-out reject all of Stoker's takes and argue with him about every single thematic element? and I am completely on board with vampire reimaginings that continuing to spit on Bram Stoker’s legacy. I hope people continue to make him roll in his grave. XD.

And again, I'm kinda surprised there were so many people during the Dracula Daily readalong acting as if the book portraying Dracula as purely evil is somehow more progressive than later adaptations portraying him as tragically sympathetic or seductive, when "questioning why the author chose to write Dracula as the monster" is kinda like "baby's first Dracula criticism." I mean that, in even in Hotel Transylvania (the recent kid's cartoon) part of the central plot is that Dracula's family is hunted down because bigoted people assume vampires are monstrous predators incapable of love. And it's not because Hotel Transylvania is a deep challenging movie, but because "let's question Why we've decided to invent this entire class of foreign predatory monsters it's okay to kill without remorse" is such a normal milquetoast uncontroversial mainstream critique of Dracula that you'll even find it in Adam Sandler children's movies. XD.

#the virgin Dracula vs the Chad hotel transylvania#(i haven't watched this movie since i was like...12? 13?)#but yeah anyway#this got lost in my drafts for a bit but im Poasting it now#XD#i know dracula daily is Over but still#thats why im posting my Anti stuff now XD#the main thing I learned reading the end of Dracula is that...yeah dracula just isnt a good book#like the chapters in Dracula's castle and the chapters about the ship are great#but despite those interesting self-contained episodes...#the novel itself is pretty weak

64 notes

·

View notes

Note

Which of the 13 seduction archetypes would each enhypen members be attracted to?

Heeseung- The Gamine, The Ingenue, The Sophisticate

Jay - The Goddess, The Empress, The Lady

Sunghoon - The Siren, The Sensualist, The Boss

Jake - The Siren, The Coquette, The Diva

Sunoo - The Bohemian, The Gamine, The Enigma

Jungwon - The Boss, The Sophisticate, The Lady

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Doses of Glamour ⚜️

Women of colour in high society:

Arielle Patrick

Caribbean communications strategist,angel investor and socialite

Dominant feminine seduction archetypes: the sophisticate and the boss

Profile: Career

One of the youngest Black C-suite executives on Wall Street, Arielle has rocketed through her field since graduating nine years ago from Princeton as a classics major.

Arielle is Chief Communications Officer at Ariel Investments, a global asset management firm, where she oversees all aspects of the firm’s communications.

Marriage to Aaron Goldstein

Ms. Patrick and Mr. Goldstein owner of Macellum Capital Management, a Manhattan-based hedge fund, met through a mutual friend in March 2019. Ms. Patrick, who was then living on Manhattan’s Upper East Side, was convinced by their mutual friend to go with her to what she referred to as “a party in Brooklyn.”

As it turned out, their mutual friend had staged the supposed party to get Ms. Patrick and Mr. Goldstein to meet.

Arielle was immediately smitten with Mr. Goldstein. “He exuded confidence,” Ms. Patrick said. “He looked and sounded like a man who knew where he was going in life.”

Mr. Goldstein was equally impressed. “I admired her ambition, family values and passion for life,” he said. “From the moment we met I just kind of knew I would marry her.”

#high society#high class heaux#high society heaux#hypergamy#hypergamous heaux#hypergamyblr#hypergamous#hypergamous lifestyle#social climbing#doses of glamour#future trophy wife#level up#spoiled girlfriend#spoiled gf#level up journey#level up mindset#luxurious black women#black girl luxury

466 notes

·

View notes

Text

ϟ THE 13 FEMININE SEDUCTION ARCHETYPES.

◟ ━━━ this is a masterlist of labels from the 13 feminine seduction archetypes. it’s a fun quiz to take while looking for archetypes for your characters. i’m using it as a reference for the character aesthetics i’m going to do soon but i thought, hey, why don’t i post it too.

THE INGENUE.

DESCRIPTION: “your impish mix of girlish charm and mature sensuality enthralls.” ╱ FAMOUS EXAMPLES: marilyn monroe, rihanna, carole lombard.

THE SENSUALIST.

DESCRIPTION: “you are a fount of love, affection, and robust sensuality.” ╱ FAMOUS EXAMPLES: sophia loren, nigella lawson, nia long.

THE DIVA.

DESCRIPTION: “your regal presence and glamorous nature enchants.” ╱ FAMOUS EXAMPLES: beyoncé, pamela churchill, isabel preysler.

THE BOSS.

DESCRIPTION: “you command power in the boardroom and the bedroom.” ╱ FAMOUS EXAMPLES: cleopatra, amal clooney, arianna huffington.

THE COQUETTE.

DESCRIPTION: “your emotional distance drives [romantic interests] to the extremes.” ╱ FAMOUS EXAMPLES: marlene dietrich, serena williams, josephine bonaparte.

THE ENIGMA.

DESCRIPTION: “your deep introversion and soulfulness magnetizes.” ╱ FAMOUS EXAMPLES: kate bush, frida kahlo, greta garbo.

THE EMPRESS.

DESCRIPTION: “you instinctively make a [partner] feel like a king.” ╱ FAMOUS EXAMPLES: wallis simpson, marjorie harvey, madame de pompadour.

THE LADY.

DESCRIPTION: “you sastify a [partner’s] desire for a nurturing, all-consuming love.” ╱ FAMOUS EXAMPLES: susan sarandon, sandra lee, ayesha curry.

THE GAMINE.

DESCRIPTION: “your natural charm and playful spirit lowers defenses.” ╱ FAMOUS EXAMPLES: audrey hepburn, janet jackson, josephine baker.

THE SIREN.

DESCRIPTION: “you are unbridled, erotic energy in its purest, most tantalizing form.” ╱ FAMOUS EXAMPLES: elizabeth taylor, mae west, brigette bardot.

THE BOHEMIAN.

DESCRIPTION: “your independent spirit & sexy, devil-may-care attitude is irresistible.” ╱ FAMOUS EXAMPLES: erykah badu, coco chanel, bianca jagger.

THE SOPHISTICATE.

DESCRIPTION: “you exude elegance, worldliness and a touch of mystery.” ╱ FAMOUS EXAMPLES: jacqueline kennedy, carla bruni, kate middleton.

THE GODDESS.

DESCRIPTION: “your sultry, serene presence makes you appear other-worldly.” ╱ FAMOUS EXAMPLES: sade, eva peron, grace kelly.

231 notes

·

View notes

Text

Femme Fatale Booklist:

Books to become your dream girl. This list is curated to unleash the empowered woman inside, tap into your dark feminine energy, and help you succeed in every area of life. Sections are listed below:

Self-Development/Mindset

Seductive Psychology

Femme Fatale/Dark Feminine/Feminist Reads

Business/Finance/Entrepreneurship

Productivity

Mental Health

Physical Health

Fashion & Beauty

Get educated. Expand your mind. Enjoy xx

Self-Development/Mindset:

Mindset: The New Psychology of Success by Carol Dweck

The Magic of Thinking Big by David Schwartz

Atomic Habits by James Clear

You Can Heal Your Life by Louise Hay

Don’t Believe Everything You Think by Joseph Nguyen

The Mountain Is You: Transforming Self-Sabotage Into Self-Mastery by Brianna Wiest

Boundary Boss: The Essential Guide to Talk True, Be Seen, and (Finally) Live Free by Terri Cole

The Confidence Formula: May Cause: Lower Self-Doubt, Higher Self-Esteem, and Comfort In Your Own Skin by Patrick King

The Slight Edge by Jeff Olson

Choose Your Story, Change Your Life: Silence Your Inner Critic and Rewrite Your Life from the Inside Out by Kindra Hall

When You’re Ready, This Is How To Heal by Brianna Wiest

Hunting Discomfort: How to Get Breakthrough Results in Life and Business No Matter What by Sterling Hawkins

The Four Pivots: Reimagining Justice, Reimagining Ourselves by Shawn Ginwright

The Artist’s Way by Julia Cameron

A New Earth: Awakening to Your Life's Purpose by Eckhart Tolle

The Power of Now by Eckhart Tolle

Seductive Psychology:

48 Laws of Power by Robert Greene

Mastery by Robert Greene

The Art of Seduction by Robert Greene

How To Win Friends & Influence People by Dale Carnegie

Power vs. Force by David Hawkins

Femme Fatale/Dark Feminine/Feminist Reads:

Unbound: A Woman’s Guide To Power by Kasia Urbaniak

Pussy: A Reclamation by Regena Thomashauer

Why Men Love Bitches: From Doormat to Dreamgirl―A Woman's Guide to Holding Her Own in a Relationship by Sherry Argov

A Single Revolution by Shani Silver

This Is Your Brain On Birth Control by Sarah Hill

Taking Charge of Your Fertility by Toni Weschler

Regretting Motherhood: A Study by Orna Donath

Invisible Women: Data Bias in a World Designed for Me by Caroline Criado Perez

Women Who Run With The Wolves: Myths and Stories of the Wild Woman Archetype by Clarissa Pinkola Estes

The Second Sex by Simone De Beauvoir

The Ethics of Ambiguity by Simone De Beauvoir

A Room of One’s Own by Virginia Woolf

Women & Power: A Manifesto by Mary Beard

Spinster by Kate Bolick

What French Women Know: About Love, Sex, and Other Matters of the Heart and Mind by Debra Ollivier

Living Forever Chic: Frenchwomen's Timeless Secrets for Everyday Elegance, Gracious Entertaining, and Enduring Allure by Tish Jett

Business/Finance/Entrepreneurship:

Never Split The Difference by Chris Voss

Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion by Robert Cialdini

The 2-Hour Cocktail Party by Nick Gray

The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People by Stephen Covey

Girl On Fire by Cara Alwill Leyba

Women, Work & the Art of Savoir Faire: Business Sense & Sensibility by Mireille Guiliano

Crucial Conversations Tools for Talking When Stakes Are High by Joseph Grenny

Living On Purpose: Five Deliberate Choices to Realize Fulfillment by Amy Eliza Wong

The Earned Life: Lose Regret, Choose Fulfillment by Marshall Goldsmith

The High 5 Habit: Take Control of Your Life with One Simple Habit by Mel Robbins

Building a Second Brain: A Proven Method to Organize Your Digital Life and Unlock Your Creative Potential by Tiago Forte

The Culture Code: The Secrets of Highly Successful Groups by Daniel Coyle

Rich As F*ck: More Money Than You Know What to Do With by Amanda Frances

Rich Bitch by Nicole Lapin

Like She Owns the Place by Cara Alwill Leyba

So Good They Can’t Ignore You by Cal Newport

The First Minute: How To Start Conversations That Get Results by Chris Fenning

Thinking, Fast and Slow by Daniel Kahneman

Build: An Unorthodox Guide to Making Things Worth Making by Tony Fadell

The Hard About Hard Things by Ben Horowitz

The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel

Productivity:

The Science of Self-Discipline: The Willpower, Mental Toughness, and Self-Control to Resist Temptation and Achieve Your Goals by Peter Hollins

Free Time: Lose The Busy Work, Love Your Business by Jenny Blake

Vision to Reality: Stop Working, Start Living by Curtis Jenkins

Deep Work: Rules For Focused Success in A Distracted World by Cal Newport

Finish What You Start by Peter Hollins

Mental Health:

Becoming The One by Sheleana Aiyana

Attached by Amir Levine

Feeling Good: The New Mood Therapy by David D. Burns

Whole Again by Jackson MacKenzie

Take Your Lunch Break by Massoma Alam Chohan

Stop Overthinking by Nick Trenton

Codependent No More by Melody Beattie

Designing the Mind: The Principles of Psychitecture by Ryan A. Bush

Radical Acceptance: Awakening The Love That Heals Fear and Shame by Tara Brach

Recovery from Gaslighting & Narcissistic Abuse, Codependency & Complex PTSD by Don Barlow

Adult Children of Emotionally Immature Parents: How to Heal from Distant, Rejecting, or Self-Involved Parents by Lindsay C. Gibson

Inner Child Recovery Work with Radical Self-Compassion by Don Barlow

What Happened To You?: Conversations on Trauma, Resilience, and Healing by Bruce D. Perry & Oprah Winfrey

Atlas of the Heart by Brené Brown

Physical Health:

The China Study by T. Collin Campbell

The Blue Zones by Dan Buettner

How Not To Die by Dr. Michael Greger

Befriending Your Body by Ann Saffi Biasetti

Brain Over Binge by Kathryn Hansen

The Power of Self-Discipline by Peter Hollins

Fit at Any Age: It's Never Too Late by Susan Niebergall

French Women Don't Get Fat by Mireille Guiliano

The Archetype Diet by Dana James

Fashion & Beauty:

The Lucky Shopping Manual: Building and Improving Your Wardrobe Piece by Piece by Andrea Linett & Kim France

Dress Like A Parisian by Alois Guinut

Parisian Chic by Ines de la Fressange & Sophie Gachet

Why French Women Wear Vintage: And other secrets of sustainable style by Alois Guinut

Ageless Beauty the French Way: Secrets from Three Generations of French Beauty Editors by Clemence von Mueffling

Skincare: The Ultimate No-Nonsense Guide by Caroline Hirons

#femme fatale#dark femininity#dark feminine energy#high value mindset#high value woman#hypergamous#feminine energy#female manipulator#the feminine urge#hypergamy#female empowerment#female power#it girl#that girl#girlblogging#gaslight gatekeep girlboss#motivational#booklover#atomic habits#art of seduction#the 48 laws of power#robert greene#french girl#level up#healthy habits#productivity#glow up#femmefatalevibe#book rec list#book rec

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

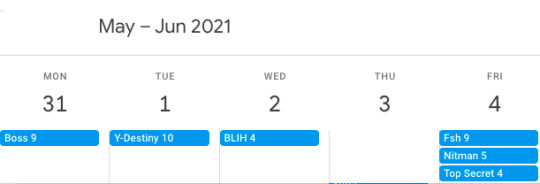

This Week in BL

May 2021 Wk 4

Being a highly subjective assessment of one tiny corner of the interwebs.

Ongoing Series - Thai

Close Friend Ep 6 fin: (Imagine You/KimmonCopter) - Fan gets a VR of his idol, they fall in love, but does it transfer to reality? A unique story and great casting of Kim & Cop into roles that stretched both actors. My favorite of the series and a good closer. Close Friend as a whole is so uneven I can’t recommend it, but individual episodes (3 MaxNat, 5 JimmyTommy, 6 KimCop) are okay.

Top Secret Together Ep 3 - no subs as yet but I still found it enjoyable. I like this series, it’s quiet. Sure, the only really unique touches are the office setting and the gay advice dads, but honestly I’LL TAKE IT. Of course my favorite couple is the hazer + freshie back at uni. What can I say? I’m a sucker for the old OLD tropes. (Should I just do a SOTUS+S rewatch this weekend to get it out of my system?)

Y-Destiny Ep 9 - Look, I’m just not a fan of the rake archetype BUT my favorite combo for this is another player, and BL almost never does that. But ta da! Y-D wins with f-buds + high heat pulp (well I suppose this is university-set Cheewin). I don’t love honest-gay messy in a long haul series (Friendzone... shudder) but I don’t mind it in short form. So I think this may be my favorite installment in this series so far.

Fish Upon The Sky Ep 8 - *big fat sigh* I thought they were going to redeem Pi by having him be genuinely nice to Meen, but no it was all to do with a dumb pin. Even though he suffers from crazy stalking in this ep, I still don’t like Pi but I’m TOTALLY on his side. Is FUTS taking us on a light weight The Effect journey? Because at this juncture I think I’d prefer that.

Nitiman Ep 4 - honestly it’s like Nitiman is vested in showing FOTS exactly what it’s doing wrong. Both shows introduced faen fatales this week. But Nitiman did theirs with a sympathetic character, genuine interest on both sides, bisexual confusion, and sweetness. In every way the opposite of (and superior to) FOTS. Even claiming, outing, and stalker characters are happening but treated differently. It’s like parallel universes. Not sure how I feel about the ending kiss though. Still, this is my favorite currently airing show. I look forward to @heretherebedork explaining to me my own feelings and why I want to forgive Bbomb the kiss but not Mork for anything. Since I’m evidently morally hypocritically confused.

Ongoing Series - Not Thai

Love is Science? (Taiwan) Ep 10 (BL subplot) - Taiwan is experiencing a C19 surge right now so this series will be delayed at least 20 days.

Be Loved in House: I Do (Taiwan) Ep 3 - dropped with subs thank heavens, all the usual tropes when you pair grumpy + tsundere: challenges, bets, crashing into beds, veiled threats... oh my! Gay boys in stripped sweaters giving advice in cafes is my new favorite thing. It’s the BL version of the “bartender is my psyche” trope. Still finding the boss character creepy. About Hank Wang (plays Shi Lei) anyone else obsessed with his sanpaku eyes? Just me? Fair. Also he keeps reminding me of Pluem Purim, I have no idea why. Something in the mannerisms, I think. They don’t really look alike. (This show may also be delayed.)

My Lascivious Boss (Vietnam) Ep 8 - continues to be good, we now have 2 faen fatales, blackmail, worried friends, and the secret identity slowly devolving. Looks like we get at least two more episodes and could be as many as 12? Very much enjoying this show.

Most Peaceful Place 2 (Vietnam) Ep 3 (AKA 6) fin - it was fine, they always rush the ending a bit in Vietnamese BL. I found the first season much stronger than this second one over all. But since they aired in the same year and there’s only six total I feel like they should be judged as a whole. So I guess I’ll say, RECOMMENDED with serious pacing issues and some plot drag particularly in the second half.

Gossip

The cast of Until We Meet Again met together, ostensibly for their own amusement but speculation is that it has something to do with Between Us AKA Hemp Rope.

Breaking News

Singto’s next starring role BL got announced Paint With Love. Between him and Ohm, they seem to be attempting to corner the market. I’m in favor. Singto plays Met, a wedding organizer, who hires Phap, a poor artist, to work on a wedding painting. Phap messes something up and ends up having to work for Med on a more permanent basis. Yet another office set BL from Thailand, following in Japan and Taiwan’s well suited footsteps... we hope. Phap is played by Tae (the original Forth in 2 Moons). No side dishes announced as yet.

Pornographer Playback is airing, the third in the series from Japan (first 2 = The Pornographer AKA The Novelist & Mood Indigo). Not recommended unless you want non-BL gay cinema with high heat, and don’t mind the mess Japan always doles out to go with it. Such as: morally flexible characters, crass manipulation, gaslighting, cheating, seduction of a minor, so much smoking, het porn, and ambiguous, sad, or depressing endings. Part one of this final installment has dropped, part two is not yet available. No subs (even if they say they have them, they’re autiogen nonsense.)

Next Week Looks Like This:

Some shows may be listed later than actual air date for International accessibility reasons.

Things are looking dire. What will we do with our lives?

Upcoming 2021 BL master post here.

Links to watch are provided when possible, ask in a comment if I missed something.

#asian bl#thaibl#thai bl#Top Secret Together#Y-Destiny#close friend the series#Close Friend#Fish Upon The Sky#Nitiman#taiwanese bl#taiwanese drama#Be Loved in House: I Do#Love is Science?#vietnamese bl#Most Peaceful Place 2#My Lascivious Boss#this week in bl#epiode recaps#Paint With Love

113 notes

·

View notes

Note

Me, watching every scene with Sevika: God that's a whole lotta woman.....

Me, seeing Mel's Mom: GOD THAT'S A WHOLE LOTTA WOMAN....

It seems just like you have a type, looking at Viktor and such, I also have a type.................................... Big Lady.

So Sevika's great, obviously (I've got a soft spot for competent, professional evil lieutenants who are constantly frustrated their bosses keep getting caught up in personal bullshit instead of keeping their eyes on the prize)

But Mel's mom I really do appreciate as them taking an incredibly masculine-coded character archetype, making them a woman, and changing absolutely nothing. Honestly can't remember the last time I can recall a woman's nudity in something not being a femme fatale seduction thing or a gross out, but just, like, a 'LBJ not letting you stop arguing with him while he pisses' power move.

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

1. Patchwork Kids

2. Impossibly Tacky Clothes

3. Social Semi-Circle

4. Rope Bridge

5. Hermetic Magic

6. After-Action Patch-Up

7. You and What Army?

8. Hitman with a Heart

9. Sleep Deprivation

10. Day in the Life

11. Improvised Parachute

12. Eyes Always Shut

13. Clam Trap

14. “Jump Off a Bridge” Rebuttal

15. Crossover Couple

16. Wild Teen Party

17. Obliviously Beautiful

18. Grave-Marking Scene

19. Baby Factory

20. Fishbowl Helmet

21. Facial Recognition Software

22. Vile Villain, Saccharine Show

23. Door Fu

24. Deer in the Headlights

25. The Mothership

26. Disney Death

27. Still Got It

28. Cannot Spit It Out

29. Creating Life Is Unforeseen

30. Human Pack Mule

31. You Shall Not Pass!

32. Psychotic Smirk

33. The Worsening Curse Mark

34. Containment Field

35. Guys Are Slobs

36. Ragtag Bunch of Misfits

37. Alternate Self

38. Great Escape

39. Inflating Body Gag

40. Mona Lisa Smile

41. BFS

42. Mad Scientist Laboratory

43. Four-Leaf Clover

44. Great Big Book of Everything

45. Why Did It Have to Be Snakes?

46. Costume-Test Montage

47. Knee-High Perspective

48. Noisy Shut-Up

49. Apathetic Citizens

50. Translation Punctation

51. Hopeless Boss Fight

52. Has a Type

53. Spelling Bee

54. Crippling Castration

55. Criminal Amnesiac

56. Gone Horribly Wrong

57. Elephants Are Scared of Mice

58. Raised by Grandparents

59. Life Imitates Art

60. Farmer’s Daughter

61. Rejection Affection

62. Criminal Doppelgänger

63. Wardrobe Wound

64. Beauty Equals Goodness

65. Traitor Shot

66. Fashion Hurts

67. Heartbreak & Ice Cream

68. Denied Food as Punishment

69. Wouldn’t Hurt a Child

70. Soup is Medicine

71. Hellish Horse

72. The Man in the Mirror Talks Back

73. Fearsome Foot

74. Teamwork Seduction

75. Chariot Pulled by Cats

76. Infection Scene

77. Friend to All Living Things

78. Kook Mobile

79. Sapient Steed

80. Geeky Turn-On

81. Call a Human a ‘Meatbag’

82. Enraged by Idiocy

83. Making the Masterpiece

84. Rigged Contest

85. Cop Killer

86. I’ll Take That as a Compliment

87. Are These Wires Important?

88. Deliberately Cute Child

89. Love Confession

90. Accidental Public Confession

91. Flagpole Challenge

92. Running Away to Cry

93. Expecting Someone Taller

94. Slow Clap

95. Mature Animal Story

96. Babies Ever After

97. Cub Cues Protective Parent

98. Underwater City

99. Empathy Pet

100. Dramatic Drop

May I present the 100 Art Challenge with Tv Tropes! Here’s the site https://tvtropes.org

10 notes

·

View notes

Link

Much like his infamous father, the aesthetic of Alucard has changed tremendously since Castlevania’s start in the 1980s—yet certain things about him never change at all. He began as the mirror image of Dracula; a hark back to the days of masculine Hammer Horror films, Christopher Lee, and Bela Lugosi. Then his image changed dramatically into the androgynous gothic aristocrat most people know him as today. This essay will examine Alucard’s design, the certain artistic and social trends which might have influenced it, and how it has evolved into what it is now.

☽ Read the full piece here or click the read more for the text only version ☽

INTRODUCTION

Published in 2017, Carol Dyhouse’s Heartthrobs: A History of Women and Desire examines how certain cultural trends can influence what women may find attractive or stimulating in a male character. By using popular archetypes such as the Prince Charming, the bad boy, and the tall dark handsome stranger, Dyhouse seeks to explain why these particular men appeal to the largest demographic beyond mere superfluous infatuation. In one chapter titled “Dark Princes, Foreign Powers: Desert Lovers, Outsiders, and Vampires”, she touches upon the fascination most audiences have with moody and darkly seductive vampires. Dyhouse exposits that the reason for this fascination is the inherent dangerous allure of taming someone—or something—so dominating and masculine, perhaps even evil, yet hides their supposed sensitivity behind a Byronic demeanour.

This is simply one example of how the general depiction of vampires in mainstream media has evolved over time. Because the concept itself is as old as the folklore and superstitions it originates from, thus varying from culture to culture, there is no right or wrong way to represent a vampire, desirable or not. The Caribbean Soucouyant is described as a beautiful woman who sheds her skin at night and enters her victims’ bedrooms disguised as an aura of light before consuming their blood. In Ancient Roman mythology there are tales of the Strix, an owl-like creature that comes out at night to drink human blood until it can take no more. Even the Chupacabra, a popular cryptid supposedly first spotted in Puerto Rico, has been referred to as being vampiric because of the way it sucks blood out of goats, leaving behind a dried up corpse.

However, it is a rare thing to find any of these vampires in popular media. Instead, most modern audiences are shown Dyhouse’s vampire: the brooding, masculine alpha male in both appearance and personality. A viewer may wish to be with that character, or they might wish to become just like that character.

This sort of shift in regards to creating the “ideal” vampire is most evident in how the image of Dracula has been adapted, interpreted, and revamped in order to keep up with changing trends. In Bram Stoker’s original 1897 novel of the same name, Dracula is presented as the ultimate evil; an ancient, almost grotesque devil that ensnares the most unsuspecting victims and slowly corrupts their innocence until they are either subservient to him (Renfield, the three brides) or lost to their own bloodlust (Lucy Westenra). In the end, he can only be defeated through the joined actions of a steadfast if not ragtag group of self-proclaimed vampire hunters that includes a professor, a nobleman, a doctor, and a cowboy. His monstrousness in following adaptations remains, but it is often undercut by attempts to give his character far more pathos than the original source material presents him with. Dracula has become everything: a monster, a lover, a warrior, a lonely soul searching for companionship, a conquerer, a comedian, and of course, the final boss of a thirty-year-old video game franchise.

Which brings us to the topic of this essay; not Dracula per say, but his son. Even if someone has never played a single instalment of Castlevania or watched the ongoing animated Netflix series, it is still most likely that they have heard of or seen the character of Alucard through cultural osmosis thanks to social media sites such as Twitter, Instagram, Reddit, and the like. Over the thirty-plus years in which Castlevania has remained within the public’s consciousness, Alucard has become one of the most popular characters of the franchise, if not the most popular. Since his debut as a leading man in the hit game Castlevania: Symphony of the Night, he has taken his place beside other protagonists like Simon Belmont, a character who was arguably the face of Castlevania before 1997, the year in which Symphony of the Night was released. Alucard is an iconic component of the series and thanks in part to the mainstream online streaming service Netflix, he is now more present in the public eye than ever before whether through official marketing strategies or fanworks.

It is easy to see why. Alucard’s backstory and current struggles are quite similar to the defining characteristics of the Byronic hero. Being the son of the human doctor Lisa Țepeș, a symbol of goodness and martyrdom in all adaptations, and the lord of all vampires Dracula, Alucard (also referred to by his birth name Adrian Fahrenheit Țepeș) feels constantly torn between the two halves of himself. He maintains his moralistic values towards protecting humanity, despite being forced to make hard decisions, and despite parts of humanity not being kind to him in turn, yet is always tempted by his more monstrous inheritance. The idea of a hero who carries a dark burden while aspiring towards nobility is something that appeals to many audiences. We relate to their struggles, cheer for them when they triumph, and share their pain when they fail. Alucard (as most casual viewers see him) is the very personification of the Carol Dyhouse vampire: mysterious, melancholic, dominating, yet sensitive and striving for compassion. Perceived as a supposed “bad boy” on the surface by people who take him at face value, yet in reality is anything but.

Then there is Alucard’s appearance, an element that is intrinsically tied to how he has been portrayed over the decades and the focus of this essay. Much like his infamous father, the aesthetic of Alucard has changed tremendously since Castlevania’s start in the 1980s—yet certain things about him never change at all. He began as the mirror image of Dracula; a hark back to the days of masculine Hammer Horror films, Christopher Lee, and Bela Lugosi. Then his image changed dramatically into the androgynous gothic aristocrat most people know him as today. This essay will examine Alucard’s design, the certain artistic and social trends which might have influenced it, and how it has evolved into what it is now. Parts will include theoretical, analytical, and hypothetical stances, but it’s overall purpose is to be merely observational.

--

What is Castlevania?

We start this examination at the most obvious place, with the most obvious question. Like all franchises, Castlevania has had its peaks, low points, and dry spells. Developed by Konami and directed by Hitoshi Akamatsu, the first instalment was released in 1986 then distributed in North America for the Nintendo Entertainment System the following year. Its pixelated gameplay consists of jumping from platform to platform and fighting enemies across eighteen stages all to reach the final boss, Dracula himself. Much like the gameplay, the story of Castlevania is simple. You play as Simon Belmont; a legendary vampire hunter and the only one who can defeat Dracula. His arsenal includes holy water, axes, and throwing daggers among many others, but his most important weapon is a consecrated whip known as the vampire killer, another iconic staple of the Castlevania image.

Due to positive reception from critics and the public alike, Castlevania joined other titles including Super Mario Bros., The Legend of Zelda, and Mega Man as one of the most defining video games of the 1980s. As for the series itself, Castlevania started the first era known by many fans and aficionados as the “Classicvania” phase, which continued until the late 1990s. It was then followed by the “Metroidvania” era, the “3-D Vania” era during the early to mid 2000s, an reboot phase during the early 2010s, and finally a renaissance or “revival” age where a sudden boom in new or re-released Castlevania content helped boost interest and popularity in the franchise. Each of these eras detail how the games changed in terms of gameplay, design, and storytelling. The following timeline gives a general overview of the different phases along with their corresponding dates and instalments.

Classicvania refers to Castlevania games that maintain the original’s simplicity in gameplay, basic storytelling, and pixelated design. In other words, working within the console limitations of the time. They are usually side-scrolling platformers with an emphasis on finding hidden objects and defeating a variety of smaller enemies until the player faces off against the penultimate boss. Following games like Castlevania 2: Simon’s Quest and Castlevania 3: Dracula’s Curse were more ambitious than their predecessor as they both introduced new story elements that offered multiple endings and branching pathways. In Dracula’s Curse, there are four playable characters each with their own unique gameplay. However, the most basic plot of the first game is present within both of these titles . Namely, find Dracula and kill Dracula. Like with The Legend of Zelda’s Link facing off against Ganon or Mario fighting Bowser, the quest to destroy Dracula is the most fundamental aspect to Castlevania. Nearly every game had to end with his defeat. In terms of gameplay, it was all about the journey to Dracula’s castle.

As video games grew more and more complex leading into the 1990s, Castlevania’s tried and true formula began to mature as well. The series took a drastic turn with the 1997 release of Castlevania: Symphony of the Night, a game which started the Metroidvania phase. This not only refers to the stylistic and gameplay changes of the franchise itself, but also refers to an entire subgenre of video games. Combining key components from Castlevania and Nintendo’s popular science fiction action series Metroid, Metroidvania games emphasize non-linear exploration and more traditional RPG elements including a massive array of collectable weapons, power-ups, character statistics, and armor. Symphony of the Night pioneered this trend while later titles like Castlevania: Circle of the Moon, Castlevania: Harmony of Dissonance and Castlevania: Aria of Sorrow solidified it. Nowadays, Metroidvanias are common amongst independent developers while garnering critical praise. Hollow Knight, Blasphemous, and Bloodstained: Ritual of the Night are just a few examples of modern Metroidvanias that use the formula to create familiar yet still distinct gaming experiences.

Then came the early to mid 2000s and many video games were perfecting the use of 3-D modelling, free control over the camera, and detailed environments. Similar to what other long-running video game franchises were doing at the time, Castlevania began experimenting with 3-D in 1999 with Castlevania 64 and Castlevania: Legacy of Darkness, both developed for the Nintendo 64 console. 64 received moderately positive reviews while the reception for its companion was far more mixed, though with Nintendo 64’s discontinuation in 2002, both games have unfortunately fallen into obscurity.

A year later, Castlevania returned to 3-D with Castlevania: Lament of Innocence for the Playstation 2. This marked Koji Igarashi’s first foray into 3-D as well as the series’ first ever M-rated instalment. While not the most sophisticated or complex 3-D Vania (or one that manages to hold up over time in terms of graphics), Lament of Innocence was a considerable improvement over 64 and Legacy of Darkness. Other 3-D Vania titles include Castlevania: Curse of Darkness, Castlevania: Judgment, and Castlevania: The Dracula X Chronicles for the PSP, a remake of the Classicvania game Castlevania: Rondo of Blood which merged 3-D models, environments, and traditional platforming mechanics emblematic of early Castlevania. It is important to note that during this particular era, there were outliers to the changing formula that included Castlevania: Portrait of Ruin and Castlevania: Order of Ecclesia, both games which added to the Metroidvania genre.

Despite many of the aforementioned games becoming cult classics and fan favourites, this was an era in which Castlevania struggled to maintain its relevance, confused by its own identity according to most critics. Attempts to try something original usually fell flat or failed to resonate with audiences and certain callbacks to what worked in the past were met with indifference.

By the 2010s, the Castlevania brand changed yet again and stirred even more division amongst critics, fans, and casual players. This was not necessarily a dark age for the franchise but it was a strange age; the black sheep of Castlevania. In 2010, Konami released Castlevania: Lords of Shadow, a complete reboot of the series with new gameplay, new characters, and new lore unrelated to previous instalments. The few elements tying it to classic Castlevania games were recurring enemies, platforming, and the return of the iconic whip used as both a weapon and another means of getting from one area to another. Other gameplay features included puzzle-solving, exploration, and hack-and-slash combat. But what makes Lords of Shadow so divisive amongst fans is its story. The player follows Gabriel Belmont, a holy warrior on a quest to save his deceased wife’s soul from Limbo. From that basic plot point, the storyline diverges immensely from previous Castlevania titles, becoming more and more complicated until Gabriel makes the ultimate sacrifice and turns into the very monster that haunted other Belmont heroes for centuries: Dracula. While a dark plot twist and a far cry from the hopeful endings of past games, the concept of a more tortured and reluctant Dracula who was once the hero had already been introduced in older Dracula adaptations (the Francis Ford Coppola directed Dracula being a major example of this trend in media).

Despite strong opinions on how much the story of Lords of Shadow diverged from the original timeline, it was positively received by critics, garnering an overall score of 85 on Metacritic. This prompted Konami to continue with the release of Castlevania: Lords of Shadow—Mirror of Fate and Castlevania: Lords of Shadow 2. Mirror of Fate returned to the series’ platforming and side-scrolling roots with stylized 3-D models and cutscenes. It received mixed reviews, as did its successor Lords of Shadow 2. While Mirror of Fate felt more like a classic stand-alone Castlevania with Dracula back as its main antagonist, the return of Simon Belmont, and the inclusion of Alucard, Lords of Shadow 2 carried over plot elements from its two predecessors along with new additions, turning an already complicated story into something more contrived.

Finally, there came a much needed revival phase for the franchise. Netflix’s adaptation of Castlevania animated by Powerhouse Animation Studios based in Austen, Texas and directed by Samuel Deats and co-directed by Adam Deats aired its first season during July 2017 with four episodes. Season two aired in October 2018 with eight episodes followed by a ten episode third season in March 2020. Season four was announced by Netflix three weeks after the release of season three. The show combines traditional western 2-D animation with elements from Japanese anime and is a loose adaptation of Castlevania 3: Dracula’s Curse combined with plot details from Castlevania: Curse of Darkness, Castlevania: Symphony of the Night, and original story concepts. But the influx of new Castlevania content did not stop with the show. Before the release of season two, Nintendo announced that classic protagonists Simon Belmont and Richter Belmont would join the ever-growing roster of playable characters in their hit fighting game Super Smash Bros. Ultimate. With their addition also came the inclusion of iconic Castlevania environments, music, weapons, and supporting characters like Dracula and Alucard.

During the year-long gap between seasons two and three of the Netflix show, Konami released Castlevania: Grimoire of Souls, a side-scrolling platformer and gacha game for mobile devices. The appeal of Grimoire of Souls is the combination of popular Castlevania characters each from a different game in the series interacting with one another along with a near endless supply of collectable weapons, outfits, power-ups, and armor accompanied by new art. Another ongoing endeavor by Konami in partnership with Sony to bring collective awareness back to one of their flagship titles is the re-releasing of past Castlevania games. This began with Castlevania: Requiem, in which buyers received both Symphony of the Night and Rondo of Blood for the Playstation 4 in 2018. This was followed the next year with the Castlevania Anniversary Collection, a bundle that included a number of Classicvania titles for the Playstation 4, Xbox One, Steam, and Nintendo Switch.

Like Dracula, the Belmonts, and the vampire killer, one other element tying these five eras together is the presence of Alucard and his various forms in each one.

--

Masculinity in 1980s Media

When it comes to media and various forms of the liberal arts be it entertainment, fashion, music, etc., we are currently in the middle of a phenomenon known as the thirty year cycle. Patrick Metzgar of The Patterning describes this trend as a pop cultural pattern that is, in his words, “forever obsessed with a nostalgia pendulum that regularly resurfaces things from 30 years ago”. Nowadays, media seems to be fixated with a romanticized view of the 1980s from bold and flashy fashion trends, to current music that relies on the use of synthesizers, to of course visual mass media that capitalizes on pop culture icons of the 80s. This can refer to remakes, reboots, and sequels; the first cinematic chapter of Stephen King’s IT, The Dark Crystal: Age of Resistance, and both Ghostbusters remakes are prime examples—but the thirty year cycle can also include original media that is heavily influenced or oversaturated with nostalgia. Netflix’s blockbuster series Stranger Things is this pattern’s biggest and most overt product.

To further explain how the thirty year cycle works with another example, Star Wars began as a nostalgia trip and emulation of vintage science fiction serials from the 1950s and 60s, the most prominent influence being Flash Gordon. This comparison is partially due to George Lucas’ original attempts to license the Flash Gordon brand before using it as prime inspiration for Star Wars: A New Hope and subsequent sequels. After Lucas sold his production company Lucasfilms to Disney, three more Star Wars films were released, borrowing many aesthetic and story elements from Lucas’ original trilogy while becoming emulations of nostalgia themselves.

The current influx of Castlevania content could be emblematic of this very same pattern in visual media, being an 80s property itself, but what do we actually remember from the 1980s? Thanks to the thirty year cycle, the general public definitely acknowledges and enjoys all the fun things about the decade. Movie theatres were dominated by the teen flicks of John Hughes, the fantasy genre found a comeback due to the resurgence of J.R.R. Tolkien’s classic works along with the tabletop role-playing game Dungeons & Dragons, and people were dancing their worries away to the songs of Michael Jackson, Whitney Houston, and Madonna. Then there were the things that most properties taking part in the thirty year cycle choose to ignore or gloss over, with some exceptions. The rise of child disappearances, prompting the term “stranger danger”, the continuation of satanic panic from the 70s which caused the shutdown and incarceration of hundreds of innocent caretakers, and the deaths of thousands due to President Reagan’s homophobia, conservatism, and inability to act upon the AIDS crisis.

The 1980s also saw a shift in masculinity and how it was represented towards the public whether through advertising, television, cinema, or music. In M.D. Kibby’s essay Real Men: Representations of Masculinity in 80s Cinema, he reveals that “television columns in the popular press argued that viewers were tired of liberated heroes and longed for the return of the macho leading man” (Kibby, 21). Yet there seemed to be a certain “splitness” to the masculine traits found within fictional characters and public personas; something that tried to deconstruct hyper-masculinity while also reviling in it, particularly when it came to white, cisgendered men. Wendy Somerson further describes this dichotomy: “The white male subject is split. On one hand, he takes up the feminized personality of the victim, but on the other hand, he enacts fantasies of hypermasculinized heroism” (Somerson, 143). Somerson explains how the media played up this juxtaposition of “soft masculinity”, where men are portrayed as victimized, helpless, and childlike. In other words, “soft men who represent a reaction against the traditional sexist ‘Fifties man’ and lack a strong male role model” (Somerson, 143). A sort of self-flagellation or masochism in response to the toxic and patriarchal gender roles of three decades previous. Yet this softening of male representation was automatically seen as traditionally “feminine” and femininity almost always equated to childlike weakness. Then in western media, there came the advent of male madness and the fetishization of violent men. Films like Scarface, Die Hard, and any of Arnold Schwarzenegger’s filmography helped to solidify the wide appeal of these hyper-masculine and “men out of control” tropes which were preceded by Martin Scorcese’s critical and cult favourite Taxi Driver.

There were exceptions to this rule; or at the very least attempted exceptions that only managed to do more harm to the concept of a feminized man while also doubling down on the standard tropes of the decade. One shallow example of this balancing act between femininity and masculinity in 80s western media was the hit crime show Miami Vice and Sonny, a character who is entirely defined by his image. In Kibby’s words, “he is a beautiful consumer image, a position usually reserved for women; and he is in continual conflict with work, that which fundamentally defines him as a man” (Kibby, 21). Therein lies the problematic elements of this characterization. Sonny’s hyper-masculine traits of violence and emotionlessness serve as a reaffirmation of his manufactured maleness towards the audience.

Returning to the subject of Schwarzenegger, his influence on 80s media that continued well into the 90s ties directly to how fantasy evolved during this decade while also drawing upon inspirations from earlier trends. The most notable example is his portrayal of Robert E. Howard’s Conan the Barbarian in the 1982 film directed by John Milius. Already a classic character from 1930s serials and later comic strips, the movie (while polarizing amongst critics who described it as a “psychopathic Star Wars, stupid and stupefying”) brought the iconic image of a muscle-bound warrior wielding a sword as half-naked women fawn at his feet back into the collective consciousness of many fantasy fans. The character and world of Conan romanticizes the use of violence, strength, and pure might in order to achieve victory. This aesthetic of hyper-masculinity, violence, and sexuality in fantasy art was arguably perfected by the works of Frank Frazetta, a frequent artist for Conan properties. The early Castlevania games drew inspiration from this exact aesthetic for its leading hero Simon Belmont and directly appropriated one of Frazetta’s pieces for the cover of the first game.

--

Hammer Horror & Gender

Conan the Barbarian, Frank Frazetta, and similar fantasy icons were just a few influences on the overall feel of 80s Castlevania. Its other major influence harks back to a much earlier and far more gothic trend in media. Castlevania director Hitoshi Akamatsu stated that while the first game was in development, they were inspired by earlier cinematic horror trends and “wanted players to feel like they were in a classic horror movie”. This specific influence forms the very backbone of the Castlevania image. Namely: gothic castles, an atmosphere of constant uncanny dread, and a range of colourful enemies from Frankenstein’s Monster, the Mummy, to of course Dracula. The massive popularity and recognizability of these three characters can be credited to the classic Universal Pictures’ monster movies of the 1930s, but there was another film studio that put its own spin on Dracula and served as another source of inspiration for future Castlevania properties.

The London-based film company Hammer Film Productions was established in 1934 then quickly filed bankruptcy a mere three years later after their films failed to earn back their budget through ticket sales. What saved them was the horror genre itself as their first official title under the ‘Hammer Horror’ brand The Curse of Frankenstein starring Hammer regular Peter Cushing was released in 1957 to enormous profit in both Britain and overseas. With one successful adaptation of a horror legend under their belt, Hammer’s next venture seemed obvious. Dracula (also known by its retitle Horror of Dracula) followed hot off the heels of Frankenstein and once again starred Peter Cushing as Professor Abraham Van Helsing, a much younger and more dashing version of his literary counterpart. Helsing faces off against the titular fanged villain, played by Christopher Lee, whose portrayal of Dracula became the face of Hammer Horror for decades to come.

Horror of Dracula spawned eight sequels spanning across the 60s and 70s, each dealing with the resurrection or convoluted return of the Prince of Darkness (sound familiar?) Yet these were not the same gothic films pioneered by Universal Studios with fog machines, high melodrama, and disturbingly quiet atmosphere. Christopher Lee’s Dracula and Bela Lugosi’s Dracula are two entirely separate beasts. While nearly identical in design (slicked back hair, long flowing black cape, and a dignified, regal demeanor), Lugosi is subtle, using only his piercing stare as a means of intimidation and power—in the 1930s, smaller details meant bigger scares. For Hammer Horror, when it comes time to show Dracula’s true nature, Lee bares his blood-covered fangs and acts like an animal coveting their prey. Hammer’s overall approach to horror involved bigger production sets, low-cut nightgowns, and bright red blood that contrasted against the muted, desaturated look of each film. And much like the media of 1980, when it came to their characters, the Dracula films fell back on what was expected by society to be ‘masculine’ and ‘feminine’ while also making slight commentary on those very preconceived traits.

The main theme surrounding each male cast in these films is endangered male authority. Dracula and Van Helsing are without a doubt the most powerful, domineering characters in the story, particularly Helsing. As author Peter Hutchings describes in his book Hammer & Beyond: The British Horror Film, “the figure of the (male) vampire hunter is always one of authority, certainty, and stability (...) he is the only one with enough logical sense to know how to defeat the ultimate evil, thus saving the female characters and weaker male characters from being further victimized” (Hutchings, 124). The key definition here is ‘weaker male characters’. Hammer’s Dracula explores the absolute power of male authority in, yet it also reveals how easily this authority can be weakened. This is shown through the characters of Jonathan Harker and Arthur Holmwood, who differ slightly from how they are portrayed in Stoker’s novel. While Dracula does weaken them both, they manage to join Helsing and defeat the monster through cooperation and teamwork. In fact, it is Harker who lands one of the final killing strikes against Dracula. However, the Jonathan Harker of Hammer’s Dracula is transformed into a vampire against his will and disposed of before the finale. His death, in the words of Hutchings, “underlines the way in which throughout the film masculinity is seen (...) as arrested, in a permanently weakened state” (Hutchings, 117).

This theme of weakened authority extends to Holmwood in a more obvious and unsettling manner. In another deviation from the source material, Lucy Westenra, best friend to Mina Murray and fiancé to Arthur Holmwood, is now Holmwood’s sister and Harker’s fiancé. Lucy’s story still plays out more or less the same way it did in the novel; Dracula routinely drains her of blood until she becomes a vampire, asserting his dominance both physically and mentally. This according to Hutchings is the entirety of Dracula’s plan; a project “to restore male authority over women by taking the latter away from the weak men, establishing himself as the immortal, sole patriarch” (Hutchings, 119). Meanwhile, it is Helsing’s mission to protect men like Arthur Holmwood, yet seems only concerned with establishing his own dominance and does nothing to reestablish Holmwood’s masculinity or authority. Due to the damage done by Dracula and the failings of Helsing, Holmwood never regains this authority, even towards the end when he is forced to murder his own sister. His reaction goes as follows: “as she is staked he clutches his chest, his identification with her at this moment, when she is restored to a passivity which is conventionally feminine, suggesting a femininity within him which the film equates with weakness” (Hutchings, 117).

So Van Helsing succeeds in his mission to defeat his ultimate rival, but Dracula is victorious in his own right. With Jonathan Harker gone, Lucy Holmwood dead, and Arthur Holmwood further emasculated, he succeeds in breaking down previous male power structures while putting himself in their place as the all-powerful, all-dominant male presence. This is the very formula in which early Hammer Dracula films were built upon; “with vampire and vampire hunter mutually defining an endangered male authority, and the woman functioning in part as the site of their struggle (...) forged within and responded to British social reality of the middle and late 1950s” (Hutchings, 123).

--

Alucard c. 1989

As for Castlevania’s Dracula, his earliest design takes more from Christopher Lee’s portrayal than from Bela Lugosi or Bram Stoker’s original vision. His appearance on the first ever box art bears a striking resemblance to one of the most famous stills from Horror of Dracula. Even in pixelated form, Dracula’s imposing model is more characteristic of Christopher Lee than Bela Lugosi.

Being his son, it would make logical sense for the first appearance of Alucard in Castlevania 3: Dracula’s Curse to resemble his father. His 1989 design carries over everything from the slick dark hair, sharp claws, and shapeless long cloak but adds a certain juvenile element—or rather, a more human element. This makes sense in the context of the game’s plot. Despite being the third title, Dracula’s Curse acts as the starting point to the Castlevania timeline (before it was replaced by Castlevania: Legends in 1997, which was then retconned and also replaced by Castlevania: Lament of Innocence in 2003 as the definitive prequel of the series). Set nearly two centuries before Simon Belmont’s time, Dracula’s Curse follows Simon’s ancestor Trevor Belmont as he is called to action by the church to defeat Dracula once he begins a reign of terror across Wallachia, now known as modern day Romania. It is a reluctant decision by the church, since the Belmont family has been exiled due to fear and superstition surrounding their supposed inhuman powers.

This is one example of how despite the current technological limitations, later Castlevania games were able to add more in-depth story elements little by little beyond “find Dracula, kill Dracula”. This began as early as Castlevania 2: Simon’s Quest by giving Simon a much stronger motivation in his mission and the inclusion of multiple endings. The improvements made throughout the Classicvania era were relatively small while further character and story complexities remained either limited or unexplored, but they were improvements nonetheless.

Another example of this slight progress in storytelling was Castlevania 3’s introduction of multiple playable characters each with a unique backstory of their own. The supporting cast includes Sypha Belnades, a powerful sorceress disguised as a humble monk who meets Trevor after he saves her from being frozen in stone by a cyclops, and Grant Danasty, a pirate who fell under Dracula’s influence before Trevor helped him break free from his curse. Then there is of course Adrian Fahrenheit Țepeș who changed his name to Alucard, the opposite of Dracula, as a symbol of rebellion against his tyrannical father. Yet Castlevania was not the first to conceptualize the very character of Alucard; someone who is the son of Dracula and whose name is quite literally the backwards spelling of his fathers’. That idea started with Universal’s 1943 venture Son of Dracula, a sequel to the 1931 classic that unfortunately failed to match the original’s effective atmosphere, scares, and story. In it, Alucard is undoubtedly the villain whereas in Dracula’s Curse, he is one of the heroes. Moral and noble, able to sway Trevor Belmont’s preconceptions of vampiric creatures, and with an odd sympathy for the monster that is his father. Alucard even goes as far as to force himself into an eternal slumber after the defeat of Dracula in order to “purge the world of his own cursed bloodline” (the reason given by Castlevania: Symphony of the Night’s opening narration).

When it comes to design, Castlevania’s Alucard does the curious job of fitting in with the franchises’ established aesthetic yet at the same time, he manages to stand out the most—in fact, all the main characters do. Everyone from Trevor, Sypha, to Grant all look as though they belong in different stories from different genres. Grant’s design is more typical of the classic pirate image one would find in old illustrated editions of Robinson Crusoe’s Treasure Island or in a classic swashbuckler like 1935’s Captain Blood starring Errol Flynn. Sypha might look more at home in a Dungeons & Dragons campaign or an early Legend of Zelda title with a large hood obscuring her facial features, oversized blue robes, and a magical staff all of which are commonplace for a fantasy mage of the 1980s. Trevor’s design is nearly identical to Simon’s right down to the whip, long hair, and barbarian-esque attire which, as mentioned previously, was taken directly from Conan the Barbarian.

Judging Alucard solely from official character art ranging from posters to other promotional materials, he seems to be the only one who belongs in the gothic horror atmosphere of Dracula’s Curse. As the physically largest and most supernaturally natured of the main cast, he is in almost every way a copy of his father—a young Christopher Lee’s Dracula complete with fangs and cape. Yet his path as a hero within the game’s narrative along with smaller, near missable details in his design (his ingame magenta cape, the styling of his hair in certain official art, and the loose-fitting cravat around his neck) further separates him from the absolute evil and domination that is Dracula. Alucard is a rebel and an outsider, just like Trevor, Sypha, and Grant. In a way, they mirror the same vampire killing troupe from Bram Stoker’s novel; a group of people all from different facets of life who come together to defeat a common foe.

The son of Dracula also shares similar traits with Hammer’s Van Helsing. Same as the Belmonts (who as vampire hunters are exactly like Helsing in everything except name), Alucard is portrayed as one of the few remaining beacons of masculinity with enough strength, skill, and logical sense who can defeat Dracula, another symbol of patriarchal power. With Castlevania 3: Dracula’s Curse, we begin to see Alucard’s dual nature in aesthetics that is automatically tied to his characterization; a balance that many Byronic heroes try to strike between masculine domination and moralistic sensitivity and goodness that is often misconstrued as weakly feminine. For now though, especially in appearance, Alucard’s persona takes more from the trends that influenced his allies (namely Trevor and Simon Belmont) and his enemy (Dracula). This of course would change drastically alongside the Castlevania franchise itself come the 1990s.

--

Gender Expression & The 1990s Goth Scene

When a person sees or hears the word “gothic”, it conjures up a very specific mental image—dark and stormy nights spent inside an extravagant castle that is host to either a dashing vampire with a thirst for blood, vengeful ghosts of the past come to haunt some unfortunate living soul, or a mad scientist determined to cheat death and bring life to a corpse sewn from various body parts. In other words, a scenario that would be the focus of some Halloween television special or a daring novel from the mid to late Victorian era. Gothicism has had its place in artistic and cultural circles long before the likes of Mary Shelley, Edgar Allan Poe, Bram Stoker, and even before Horace Walpole’s The Castle of Otranto, a late 18th century novel that arguably started the gothic horror subgenre.

The term itself originated in 17th century Sweden as a descriptor of the national romanticism concerning the North Germanic Goths, a tribe which occupied much of Medieval Götaland. It was a period of historical revisionism in which the Goths and other Viking tribes were depicted as heroic and heavily romanticised. Yet more than ever before, gothicism is now associated with a highly specific (and in many ways personal) form of artistic and gender expression. It started with the golden age of gothic Medieval architecture that had its revival multiple centuries later during the Victorian era, then morphed into one of the darkest if not melodramatic literary movements, and finally grew a new identity throughout the 1990s. For this portion, we will focus on the gothic aesthetic as it pertains to fashion and music.