#robert wright

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Eagles of Mercy

Upon landing in Normandy on D-Day, one of Easy Company’s medics connected with three other medics of the 101st Airborne Division and set up a makeshift aid station in the church of Angoville-au-Plain, a small village a mere 10 miles behind Utah Beach. Medic Edwin Pepping of Easy Company spent hours helping another medic by the name of Willard Moore transport severely wounded soldiers in a jeep to L’église Saint-Côme-et-Saint-Damien, the Church of Saint Côme and Saint Damien.

Back at the church, Medic Robert Wright began to treat the many wounded while Kenneth Moore, a stretcher bearer with not quite as much medical training, helped unload the men brought to them by jeep. They had lost a majority of their medical supplies on the jump and had to treat the men with anything and everything they could find, all while under heavy artillery fire.

They accepted any and all wounded into their care, regardless of nationality, under the stipulation that all rifles be left outside the church door. Men were laid on the pews with their heads facing the aisle, pews that remain in the church to this day. Those most seriously wounded, the ones they weren’t sure would make it, were placed behind the alter and given morphine.

Amidst one particularly intense shelling, a mortar fell through the roof of the church and landed in the center aisle. Miraculously, it didn’t explode, and Wright threw the shell out of a window. Pepping eventually moved on to reunite Easy Company, but Wright and Moore remained. They treated 80 seriously wounded American, French, and German soldiers as they worked 72 hours until the village was liberated on June 8, losing only two men.

The locals believe Wright and Moore landing near their village and choosing their church as an aid station to be no accident. Their church, as fate would have it, was named after two saints:

“L'église Saint-Côme-et-Saint-Damien, takes its name from 4th century martyrs: Saint Cosmas and Saint Damian. Saints Cosmas and Damian were physicians and possibly brothers who hailed from ancient Syria, then a province of the Roman Empire. They are widely regarded to be the patron saints of doctors, surgeons, and pharmacists. In fact, the saints were renowned for healing those who were ill or wounded as well as caring for all people regardless of their background, race, or faith.“

A stain glass window was installed in the church paying tribute to these two men and a memorial was lane

A documentary was created telling the story of the Eagles of Mercy featuring interviews with some of the veterans. Watch it for free at the link below:

vimeo

#I have like 5 sources not just the one#band of brothers#medic#wwii#real bob#history#d-day#Edwin Pepping#Kenneth Moore#Willard Moore#Robert Wright#Normandy#easy company#magnolias for doc

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

#musicals#musical theater#musical theatre#theater#theatre#Richard Rodgers#Oscar Hammerstein#Oscar Hammerstein II#Lorenz Hart#George Gershwin#Ira Gershwin#Alan Jay Lerner#Frederick Loewe#John Kander#Fred Ebb#Jerry Bock#Sheldon Harnick#Robert Wright#George Forrest#Harvey Schmidt#Tom Jones#Charles Strouse#Lee Adams#Stephen Ahrens#Lynn Flaherty#Richard Maltby#Richard Maltby Jr.#David Shire#Michael Kunze#Sylvester Levay

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

Half a year ago, I got myself involved in a thread which compared trans rights to gay rights and tried to make a case that, in terms of arguments for each, the issues are not as directly comparable as a lot of people seem to think. A lot of my perspective comes from a sort of an empathy I feel with the non- religiously conservative, non- radical feminist motivations for doubting some of what this social movement is pushing for, particularly with regard to its disconnect with how more traditional people view identity categories.

This portion of a recent interview on the YouTube channel Nonzero (see until 47:43) is a stunningly crystal-clear illustration of the attitude and motivation I was trying to describe at the time, so much so that I think it's instructive and kind of fascinating to watch, even if it's almost so extreme and ridiculous as to come across as parody. (Warning: a certain kind of non-conservative, non-TERFy transphobia, which I'll quote bits of below.)

The interviewee, Norman Finkelstein, feels violently averse to using "they/them" pronouns purely because it would be implicitly affirming what in his mind is an untruth. (Presumably he would not want to refer to a male-presenting student as "she" or a female-presenting student as "he", for a similar reason, but this doesn't directly come up.) He appears to have no other motive, but the motive of not liking to "play along" with someone else's factual untruth is plenty for him. There is no particular social conservatism evident in him; he states plainly that he's fine with androgyny, of people dressing/presenting any way they wish, and that stuff doesn't bother him in the slightest, because that doesn't involve saying things that are untrue. Politically and philosophically he is obviously left-leaning, pro-science, and non/anti-religious in most areas: he repeatedly likens affirming someone's gender identity to affirming that the world is flat or that climate change isn't real or "all the craziness you attribute to the Trump base". Not pronouncing things that imply a factual untruth or deny objective reality is sacred to him as a professor and an intellectual, is what he is saying.

Also, this:

I'm not insulting anyone. If I'm calling you a "he", it's not like I'm calling you the N word or I'm calling you a c*** or something. It's just a relatively stable identifier.

Notice how completely uncomprehending Finkelstein is of the notion that not affirming someone's claimed identity (on the basis of what he believes to be objective reality or established definitions of words) could possibly be an insult or convey lack of respect or qualify as dehumanizing treatment of someone else. That a refusal to affirm someone's claimed identity (on the basis that it denies objective reality) is somehow a form of dehumanization is a completely unfathomable concept to many.

Now I find Finkelstein's perspective flawed on at least half a dozen counts, and fallacious on a particular fundamental level in conflating different types of "objective facts" (something that Robert Wright, who takes a much more reasonable, kind, and open-minded agnostic view on all of this, gently tried to push back on him about). I do think Finkelstein had some good points later in the excerpt about not forcing jarring changes in language down everyone's throats -- this is how I feel about artificial and ugly terms like Latinx, for instance, and I would have had some issues with xie/xir and the like becoming widespread nonbinary pronouns -- but in my opinion these points can't be applied well to using singular "they" for nonbinary people. Moreover, Finkelstein comes across as hardly more than a crusty, curmudgeonly jackass throughout, one who proudly and stubbornly adheres to a disagreeable absolutist view and refuses to open his mind to where his defense of that view might be flawed.

(More minor point: in arguing that mispronouning someone isn't a form of insult, he compares it to factually saying someone's hair is white or that their muscular dystrophy will prevent them from running a 4-minute mile. But, while maybe "insult" or "dehumanization" wouldn't be the best way to describe these things, they are certainly rude in certain contexts: you probably shouldn't call attention to someone's hair being white if they are sensitive about aging, for instance. Similarly, calling a nonbinary but male-presenting person "he" is pretty unkind if they don't want to present as male and are sensitive about it. But Finkelstein clearly isn't the kind of person to prioritize others' feelings over his duty towards "objective reality" in this way.)

But I contend that this is simply an extreme and rather dickish version of how tons and tons of people think, because in terms of the history of social justice and civil rights movements, it is brand new for a movement to be so heavily based in the objective truth of internally-felt identities and accusing people of fundamental dehumanization when they refuse to affirm them. And yet, activist rhetoric sounds as if this is simply part of how identities always worked and what dehumanization always meant, rather than something that appeared on the scene just yesterday.

There is certainly still a major constituency of conservatively religious people who believe that everyone should only do with their bodies what their bodies were "created to do" or whatever, but conservative Christianity is very weakened in our culture since it lost the last major culture war, and I think a lot of people in that camp still also fall into the category of finding it incomprehensible nonsense to say that an identity category is whatever each of us says it is and that it's dehumanizing ever to imply otherwise. I believe it's simply a misconception to assume that the pushback against trans activism is comprised mainly of fundamentalists and TERFs. Norman Finkelstein is an (albeit extreme) example of someone who appears to be neither, and my perception at least in the US is that most people are neither, but that a great many Americans, if not a majority, don't really get the "identity is whatever you say it is" concept and at best are bemusedly humoring it as long as it doesn't get too much into their faces.

(On each day of this past weekend, I was in a different public place -- a bar restaurant and a coffee shop -- and overheard part of a conversation about how "the people in such-and-such social group over there all ask about and share pronouns and a bunch of them go by 'they'", and in context this wasn't being attacked in any way, but it was being treated as bemusing and only semi-comprehensible.)

As Tumblr user Bambamramfan once said, people (particularly scientific-minded, non-faith-y people) really don't like to assert things they don't actually believe (don't have time to look up the post right now; the way they phrased it was something like "Americans don't like to lie about what they believe" and it was in the context of lesser-of-two-evils voting, a topic on which I emphatically disagreed with Bambambramfan, but I consider that particular point to be wise). I wish this were more recognized in social justice activism communities in general, and both that more rhetoric were crafted and ideological assumptions were more carefully examined with it in mind.

I'll end by saying, as I've probably said before, that I'm not claiming just because certain ideological assumptions in trans right activism are fundamentally brand new, that they are wrong or shouldn't become adopted by the wider community. Lots of fundamental ideological assumptions that we are obviously better off for making the default, such as "people owning other people is a gross moral evil", were once brand new at least on a society-wide scale. What I complain about is activists completely refusing to acknowledge or even be aware of this novelty, and so refusing to critically examine it, to defend it on its own merits, or to meet others where they're at.

#trans issues#robert wright#transphobia cw#racial slurs#conservative christianity#terf ideology#social justice

109 notes

·

View notes

Text

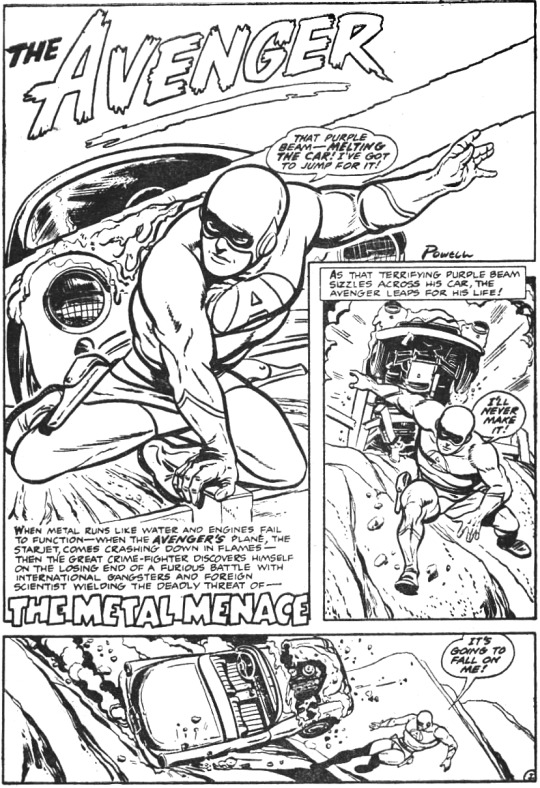

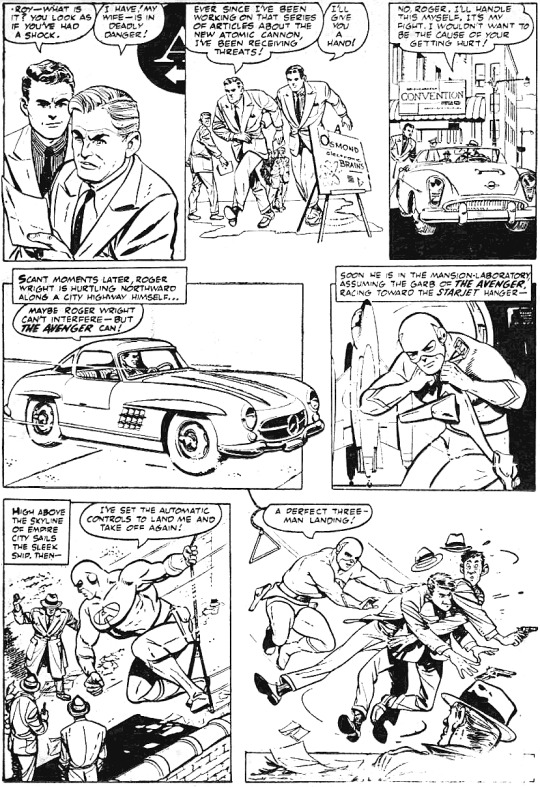

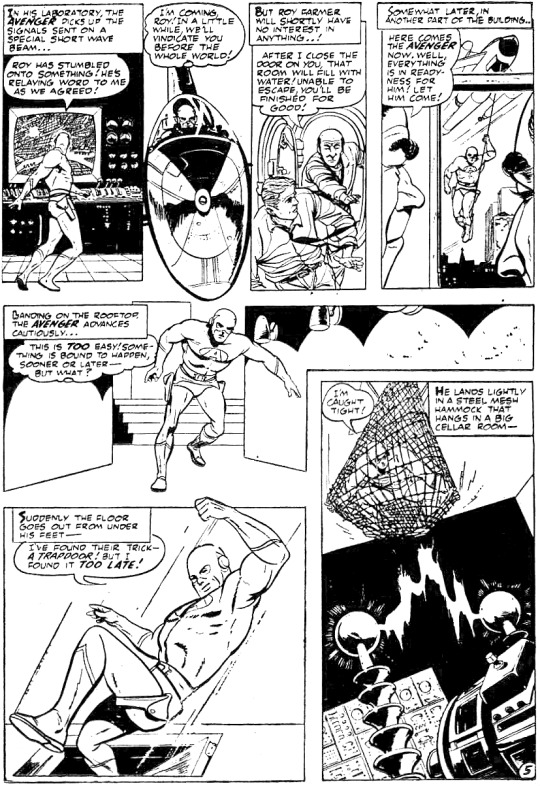

The Avenger

pdsh.fandom.com/wiki/Avenger_(Magazine_Enterprises)

Creator(s): Dick Ayres, Gardner Fox, Powell

Alias(es): Robert Wright

1st Issue w/Uniform: The Avenger #1

Year/Month of Publication: 1955/02

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

This is the video that made me go "okay I need to make this a spam, not just a single link" because HOT DAMN! THE SUPREMES DOING STRANGER IN PARADISE! WHAT!

(And yes, they were one of the other Ed Sullivan performances, September 25, 1966)

#the supremes#florence ballard#mary wilson#diana ross#stranger in paradise#george forrest#robert wright#alexander borodin#category: music#category: musicals

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Autism and the Two Kinds of Empathy | Robert Wright & Simon Baron-Cohen

"0:00 The (fuzzy) distinction between cognitive and emotional empathy

7:01 Simon’s work on autism and empathy

15:59 Should we really view autism as a spectrum?

26:17 Are powerful people bad at cognitive empathy?

40:19 Hitler, tribalism, and the societal dynamics of empathy

53:58 Can cognitive empathy save the world?

1:00:50 The “double-empathy” problem

1:04:52 How autistic kids play differently"

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

1990 Tony Awards - Michael Jeter, Brent Barrett and Company perform Wel'll Take a Glass Together from the musical Grand Hotel

#LOOK AT THAT OLD MAN GOOO#i watch this daily#michael jeter#brent barrett#grand hotel#robert wright#george forrest#maury yeston#musical#broadway#video#posted

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Anlässlich einer Tausendundeiner-Nacht-bezogenen Lektüre, die in der hoffnungsvoll bald vorkommenden Leseliste auftauchen wird, war mir einmal wieder nach dem Kismet-Musical, einer Extase aus Lied, Spektakel und Liebe in Cinemascope und Farbe. Wie so oft.

#Kismet#Howard Keel#Ann Blyth#Dolores Gray#Vic Damone#Monty Woolley#Sebastian Cabot#Film gesehen#Vincente Minnelli#Musical#Robert Wright#George Forrest#Alexander Borodin

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Robert Wright – Tanrı’nın Evrimi (2024)

‘Tanrı’nın Evrimi’, dinin ve Tanrı inançlarının kökenlerini ve evrimini bilimsel bir bakış açısıyla inceleyen ilgi çekici bir eser. Yazar, bu kitapta dinin sadece kültürel bir olgu olmadığını, aynı zamanda insan evrimiyle yakından ilişkili bir fenomen olduğunu savunur. Robert Wright, dinin insanlık tarihindeki en etkili sosyal güçlerden biri olduğunu ve bu gücünü evrimsel süreçlere borçlu…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

“The human brain is a machine designed by natural selection to respond in pretty reflexive fashion to the sensory input impinging on it. It is designed, in a certain sense, to be controlled by that input. And a key cog in the machinery of control is the feelings that arise in response to the input. If you interact with those feelings via tanha—via the natural, reflexive thirst for the pleasant feelings and the natural, reflexive aversion to the unpleasant feelings—you will continue to be controlled by the world around you. But if you observe those feelings mindfully rather than just reacting to them, you can in some measure escape the control; the causes that ordinarily shape your behavior can be defied, and you can get closer to the unconditioned.”

Robert Wright; Why Buddhism is True

1 note

·

View note

Text

Book Review: ‘Why Buddhism is True’ by Robert Wright…

Okay, I owe this review to Robert Wright as payback, because, while others at my Buddhist college were ‘oohing’ and ‘aahing’ back in 2017 over the release of his book ‘Why Buddhism is True’, I was extremely skeptical—and quite vocal about it. Why? Well, first, there’s the title: ‘Why Buddhism is True’. It seemed phony to me, as phony as some rock-and-roll band calling themselves ‘Nirvana’. Don’t…

#Buddhism#dharma#emptiness#Hardie Karges#meditation#nirvana#Robert Wright#The Matrix#Theravada#Virtual Reality

0 notes

Text

27 de febrero de 2023

"Many of these self-serving biases fall under the broader rubric of 'confirmation bias'. [...] What makes the moral stakes especially high is the way these biases interact with a feature of psychology that is more obviously moral in nature. Namely: the sense of justice. [...] And, as we've just seen, our judgements are designed not to be impartial. [...] The most common explosive additive is the perception that relations between the groups are zero-sum -- that one group's win is another group's loss. [...] If Green thinks that getting people to couch their moral arguments in a highly reasonable language, I think he's underestimating the cleverness and ruthlessness with which our inner animals pursue natural selection's agenda. We seem designed to twist moral discourse --whatever language it's framed in-- to selfish or tribal ends, and to remain conveniently unaware of the twisting. [...] If psychology tells us anything, it is to be suspicious of the intuition that the other guys are the problem and we're not."

--Robert Wright on Joshua Green's 'Moral Tribes'.

0 notes

Text

Taking the red pill

[...]

I saw The Matrix in 1999, right after it came out, and some months later I learned that I had a kind of connection to it. The movie’s directors, the Wachowski siblings, had given Keanu Reeves three books to read in preparation for playing Neo. One of them was a book I had written a few years earlier, The Moral Animal: Evolutionary Psychology and Everyday Life.

I’m not sure what kind of link the directors saw between my book and The Matrix. But I know what kind of link I see. Evolutionary psychology can be described in various ways, and here’s one way I had described it in my book: It is the study of how the human brain was designed—by natural selection—to mislead us, even enslave us.

Don’t get me wrong: natural selection has its virtues, and I’d rather be created by it than not be created at all—which, so far as I can tell, are the two options this universe offers. Being a product of evolution is by no means entirely a story of enslavement and delusion. Our evolved brains empower us in many ways, and they often bless us with a basically accurate view of reality.

Still, ultimately, natural selection cares about only one thing (or, I should say, “cares”—in quotes—about only one thing, since natural selection is just a blind process, not a conscious designer). And that one thing is getting genes into the next generation. Genetically based traits that in the past contributed to genetic proliferation have flourished, while traits that didn’t have fallen by the wayside. And the traits that have survived this test include mental traits—structures and algorithms that are built into the brain and shape our everyday experience. So if you ask the question “What kinds of perceptions and thoughts and feelings guide us through life each day?” the answer, at the most basic level, isn’t “The kinds of thoughts and feelings and perceptions that give us an accurate picture of reality.” No, at the most basic level the answer is “The kinds of thoughts and feelings and perceptions that helped our ancestors get genes into the next generation.” Whether those thoughts and feelings and perceptions give us a true view of reality is, strictly speaking, beside the point. As a result, they sometimes don’t. Our brains are designed to, among other things, delude us.

Not that there’s anything wrong with that! Some of my happiest moments have come from delusion—believing, for example, that the Tooth Fairy would pay me a visit after I lost a tooth. But delusion can also produce bad moments. And I don’t just mean moments that, in retrospect, are obviously delusional, like horrible nightmares. I also mean moments that you might not think of as delusional, such as lying awake at night with anxiety. Or feeling hopeless, even depressed, for days on end. Or feeling bursts of hatred toward people, bursts that may actually feel good for a moment but slowly corrode your character. Or feeling bursts of hatred toward yourself. Or feeling greedy, feeling a compulsion to buy things or eat things or drink things well beyond the point where your well-being is served.

Though these feelings—anxiety, despair, hatred, greed—aren’t delusional the way a nightmare is delusional, if you examine them closely, you’ll see that they have elements of delusion, elements you’d be better off without.

And if you think you would be better off, imagine how the whole world would be. After all, feelings like despair and hatred and greed can foster wars and atrocities. So if what I’m saying is true—if these basic sources of human suffering and human cruelty are indeed in large part the product of delusion—there is value in exposing this delusion to the light.

An everyday delusion

Let’s take a simple but fundamental example: eating some junk food, feeling briefly satisfied, and then, only minutes later, feeling a kind of crash and maybe a hunger for more junk food. This is a good example to start with for two reasons.

First, it illustrates how subtle our delusions can be. There’s no point in the course of eating a six-pack of small powdered-sugar doughnuts when you’re believing that you’re the messiah or that foreign agents are conspiring to assassinate you. And that’s true of many sources of delusion that I’ll discuss in this book: they’re more about illusion—about things not being quite what they seem—than about delusion in the more dramatic sense of that word. Still, by the end of the book, I’ll have argued that all of these illusions do add up to a very large-scale warping of reality, a disorientation that is as significant and consequential as out-and-out delusion.

The second reason junk food is a good example to start with is that it’s fundamental to the Buddha’s teachings. Okay, it can’t be literally fundamental to the Buddha’s teachings, because 2,500 years ago, when the Buddha taught, junk food as we know it didn’t exist. What’s fundamental to the Buddha’s teachings is the general dynamic of being powerfully drawn to sensory pleasure that winds up being fleeting at best. One of the Buddha’s main messages was that the pleasures we seek evaporate quickly and leave us thirsting for more. We spend our time looking for the next gratifying thing—the next powdered-sugar doughnut, the next sexual encounter, the next status-enhancing promotion, the next online purchase. But the thrill always fades, and it always leaves us wanting more. The old Rolling Stones lyric “I can’t get no satisfaction” is, according to Buddhism, the human condition. Indeed, though the Buddha is famous for asserting that life is pervaded by suffering, some scholars say that’s an incomplete rendering of his message and that the word translated as “suffering,” dukkha, could, for some purposes, be translated as “unsatisfactoriness.”

So what exactly is the illusory part of pursuing doughnuts or sex or consumer goods or a promotion? There are different illusions associated with different pursuits, but for now we can focus on one illusion that’s common to these things: the overestimation of how much happiness they’ll bring. Again, by itself this is delusional only in a subtle sense. If I asked you whether you thought that getting that next promotion, or getting an A on that next exam, or eating that next powdered-sugar doughnut would bring you eternal bliss, you’d say no, obviously not. On the other hand, we do often pursue such things with, at the very least, an unbalanced view of the future. We spend more time envisioning the perks that a promotion will bring than envisioning the headaches it will bring. And there may be an unspoken sense that once we’ve achieved this long-sought goal, once we’ve reached the summit, we’ll be able to relax, or at least things will be enduringly better. Similarly, when we see that doughnut sitting there, we immediately imagine how good it tastes, not how intensely we’ll want another doughnut only moments after eating it, or how we’ll feel a bit tired or agitated later, when the sugar rush subsides.

Why pleasure fades

It doesn’t take a rocket scientist to explain why this sort of distortion would be built into human anticipation. It just takes an evolutionary biologist—or, for that matter, anyone willing to spend a little time thinking about how evolution works.

Here’s the basic logic. We were “designed” by natural selection to do certain things that helped our ancestors get their genes into the next generation—things like eating, having sex, earning the esteem of other people, and outdoing rivals. I put “designed” in quotation marks because, again, natural selection isn’t a conscious, intelligent designer but an unconscious process. Still, natural selection does create organisms that look as if they’re the product of a conscious designer, a designer who kept fiddling with them to make them effective gene propagators. So, as a kind of thought experiment, it’s legitimate to think of natural selection as a “designer” and put yourself in its shoes and ask: If you were designing organisms to be good at spreading their genes, how would you get them to pursue the goals that further this cause? In other words, granted that eating, having sex, impressing peers, and besting rivals helped our ancestors spread their genes, how exactly would you design their brains to get them to pursue these goals? I submit that at least three basic principles of design would make sense:

1. Achieving these goals should bring pleasure, since animals, including humans, tend to pursue things that bring pleasure.

2. The pleasure shouldn’t last forever. After all, if the pleasure didn’t subside, we’d never seek it again; our first meal would be our last, because hunger would never return. So too with sex: a single act of intercourse, and then a lifetime of lying there basking in the afterglow. That’s no way to get lots of genes into the next generation!

3. The animal’s brain should focus more on (1), the fact that pleasure will accompany the reaching of a goal, than on (2), the fact that the pleasure will dissipate shortly thereafter. After all, if you focus on (1), you’ll pursue things like food and sex and social status with unalloyed gusto, whereas if you focus on (2), you could start feeling ambivalence. You might, for example, start asking what the point is of so fiercely pursuing pleasure if the pleasure will wear off shortly after you get it and leave you hungering for more. Before you know it, you’ll be full of ennui and wishing you’d majored in philosophy.

If you put these three principles of design together, you get a pretty plausible explanation of the human predicament as diagnosed by the Buddha. Yes, as he said, pleasure is fleeting, and, yes, this leaves us recurrently dissatisfied. And the reason is that pleasure is designed by natural selection to evaporate so that the ensuing dissatisfaction will get us to pursue more pleasure. Natural selection doesn’t “want” us to be happy, after all; it just “wants” us to be productive, in its narrow sense of productive. And the way to make us productive is to make the anticipation of pleasure very strong but the pleasure itself not very long-lasting.

Scientists can watch this logic play out at the biochemical level by observing dopamine, a neurotransmitter that is correlated with pleasure and the anticipation of pleasure. In one seminal study, they took monkeys and monitored dopamine-generating neurons as drops of sweet juice fell onto the monkeys’ tongues. Predictably, dopamine was released right after the juice touched the tongue. But then the monkeys were trained to expect drops of juice after a light turned on. As the trials proceeded, more and more of the dopamine came when the light turned on, and less and less came after the juice hit the tongue.

We have no way of knowing for sure what it felt like to be one of those monkeys, but it would seem that, as time passed, there was more in the way of anticipating the pleasure that would come from the sweetness, yet less in the way of pleasure actually coming from the sweetness. To translate this conjecture into everyday human terms:

If you encounter a new kind of pleasure—if, say, you’ve somehow gone your whole life without eating a powdered-sugar doughnut, and somebody hands you one and suggests you try it—you’ll get a big blast of dopamine after the taste of the doughnut sinks in. But later, once you’re a confirmed powdered-sugar-doughnut eater, the lion’s share of the dopamine spike comes before you actually bite into the doughnut, as you’re staring longingly at it; the amount that comes after the bite is much less than the amount you got after that first, blissful bite into a powdered-sugar doughnut. The pre-bite dopamine blast you’re now getting is the promise of more bliss, and the post-bite drop in dopamine is, in a way, the breaking of the promise—or, at least, it’s a kind of biochemical acknowledgment that there was some overpromising. To the extent that you bought the promise—anticipated greater pleasure than would be delivered by the consumption itself—you have been, if not deluded in the strong sense of that term, at least misled.

Kind of cruel, in a way—but what do you expect from natural selection? Its job is to build machines that spread genes, and if that means programming some measure of illusion into the machines, then illusion there will be.

[…]

--Robert Wright en "Why Buddhism is True"

1 note

·

View note

Text

With regard to the recent testimony of several presidents of major universities about their policies on antisemitic speech, my orbit seems divided into people who are ignoring the story entirely and people who have reacted to it with nothing but outrage and exasperation toward the university presidents. I also find the whole event and situation frustrating and disturbing, but I'm wondering if I'm the only one out there who can't help feeling some significant degree of sympathy with the university presidents and why they might feel like they're in a bind under that type of questioning.

(I haven't gotten my hands on a more comprehensive video that shows the hearing -- the only video I was able to find that looked it might contain this was 5 hours or something -- but this treatment by David Pakman contains about the most footage I've seen. Notice how Pakman, perhaps not deliberately, distorts the sense of the MIT president's meaning in her sentence, "I've heard chants, which can be antisemitic depending on the context, when calling for the elimination of the Jewish people" by seeming to rearrange the quote in his mind so that the phrase "calling for the elimination of the Jewish people" is placed earlier in the sentence implying that calling for the elimination of the Jewish people is only sometimes antisemitic. Which is not at all what she said.)

Here's the thing: accusations of antisemitism and particularly the use of the term "genocide"/"genocidal" in speech content are being thrown around quite loosely nowadays. The way the presidents squirmed around struggling to navigate how to answer the questions was cringeworthy to be sure, and made worse by the fact that they didn't explain what they meant by "become conduct", but it's kind of understandable that they wouldn't want to straight-up say "Yes, we have a no-tolerance policy towards all calls for genocide against Jews" knowing that will immediately be turned onto them the next time a pro-Palestine slogan which someone on the pro-Israel side might interpret as antisemitic is uttered on their campus. For instance, "From the river to the sea!" seems to take on a range of meanings depending on who you ask, from "Get all Jews out of that whole piece of land!" to (according to for example Robert Wright) "Let's have a one-state solution where Palestinians get equal rights throughout that whole piece of land!"; the former can certainly be argued to be genocidal whereas a lot of protesters will probably (perhaps quite sincerely) claim the latter meaning.

(It's like during that whole debate about whether or not it's okay to punch a Nazi: I think a lot more of us may have been comfortable saying that Nazi-punching is generally okay, if it hadn't been for the fact that there was a visibly large overlap between the people advocating Nazi-punching and the types who tended to wield very broad criteria for who qualifies as a Nazi.)

I don't really have the time or energy to try to develop a full-blown stance on where the boundaries of free speech should be on college campuses or anywhere else. My general inclination would be to draw the line at speech that advocates intolerance of groups that include people that would be on the campus. So for instance, speech advocating genocide of Jews as a general group (which would include Jewish students/faculty/staff on campus), let alone speech expressing hatred toward or otherwise harassing/threatening any individuals or subsets of Jewish students/faculty/staff at the university, should not be tolerated under university policy. Speech advocating removing Israeli Jews from the state of Israel (the most extreme interpretation of "From the river to the sea!") is pretty disturbing and frighteningly reminiscent of early Nazi policy, and Jewish students wouldn't be unreasonable to feel deeply offended by it and I don't feel great about allowing it, but I'm not sure if it crosses that line. I don't know. The policy position I'm suggesting could plausibly be what the university presidents were espousing, but it was hard to tell without further clarifications from them, and it may just be wishful thinking on my part.

I do agree with David Pakman and others that, almost certainly, if you replace "antisemitic" with "anti-black" or "anti-Asian" or "misogynistic" (or probably even "anti-Muslim"), those university presidents would have without hesitation sung a very different tune, and that is an issue that needs to be examined and reckoned with. I'm not sure I'd say that it's evidence that Jews are uniquely hated among marginalized groups exactly, but it's a reflection of the fact that this recent general turn of events has kind of broken the guiding lines of certain strains of US progressive ideology.

#current israel-palestine conflict#antisemitism#genocide#david pakman#robert wright#punching nazis#free speech

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

''What’s more—and what’s more relevant to this chapter—although right mindfulness comes before right concentration on the Eightfold Path, cultivating mindfulness may require first cultivating concentration. That’s why the early part of a mindfulness meditation session typically involves focusing on your breath or on something else. Mustering some concentration is what liberates you from the default mode network and stops the mental chatter that normally preoccupies you.

Then, having used concentration meditation to stabilize your attention, you can shift your attention to whatever it is you’re now going to be mindful of—usually things that are happening inside you, such as emotions or bodily sensations, though you can also focus on things in the outside world, such as sounds. Meanwhile the breath recedes to the background, though it may remain your “anchor,” something you’re fuzzily aware of even as you examine other things, and something you may return your attention to from time to time. The key thing is that, whatever you’re experiencing, you experience it mindfully, with that ironic combination of closeness and critical distance that I mentioned in describing how I had viewed the feeling of overcaffeination.''

-Robert Wright, Why Buddhism Is True

0 notes

Text

youtube

Not Since Nineveh is actually my favorite track from Kismet, but I guess the specificity of the lyrics puts the kibosh on its popularity as a cover choice. Wish there were more cross-genre ensemble covers like this one, though. I guess the composition just demands that big band swag too much?

(For potential link rot purposes, this is the Percy Faith Orchestra cover of Not Since Nineveh from the musical Kismet)

0 notes