#pleistocene coyote

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Everlastingly Yours

#own art#oc#Ploc#Pleistocene coyote#dire coyote#coyote#canine#digital art#this is the day Ploc fell into the la brea tar pits#idk why I haven’t drawn an angsty dog in a while?#i learned how to draw drawing angsty dogs

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Patreon request for @/brittoniawhite (Instagram handle) - Thylacinus cynocephalus. I’ve drawn this guy already, but here’s a new pose AND a size chart, which the previous post didn’t have.

Known by several common names: the Tasmanian Tiger, Tasmanian Wolf, or simply the Thylacine, Thylacinus cynocephalus was neither canine nor feline, but instead a large carnivorous marsupial.

Being a marsupial, it had a pouch. Though it was unique in that both females and males had pouches: the males’ were used to protect their reproductive organs. Thylacine life expectancy was estimated to be between 5 and 7 years, though some captive specimens lived to 9 years. They were shy and nocturnal carnivores, likely eating other marsupials such as kangaroos, wallabies, wombats, and possums, as well as other small animals and birds, such as the similarly extinct Tasmanian Emu. However, it is a matter of dispute whether the thylacine would have been able to take on prey items as large or larger than itself. It is unknown whether they hunted alone or in small family groups, though captive thylacines did get along with each other.

Thylacinus cynocephalus was the last of the Thylacinids, a family of Dasyuromorph marsupials. It lived from the Pleistocene to the Holocene in Australia and New Guinea, driven to extinction in the 1930s by hunting, human encroachment, disease, and feral dogs. The thylacine was already extinct on the Australian mainland and New Guinea by the time British settlers arrived, with the island of Tasmania being its last stronghold. Settlers feared the marsupial would attack them and their livestock, demonizing it as a “blood drinker”, and bounties were put in place that drove the thylacine to be overhunted. As they became rarer, there was a push to capture thylacines and keep them alive in captivity, but unfortunately it was too little, too late. Conservation and animal welfare was not at the level it is today, not much was known about their behavior in the wild, and there was only one successful birth in captivity. Studies show that with continued successful breeding, a campaign to change public perception, and protections put into place much earlier, the thylacine could have been saved. But the last captive thylacine died in 1936, and official protection was not put in place until that year, 59 days before his death. Sightings continued into the 1980s, and even today some claim to see them, but all of these sightings are unconfirmed and unlikely. As are all the other animals on this account, the thylacine is definitively extinct.

Today, carnivores such as wolves and coyotes are demonized in the same way the thylacine was, and there are some who wish to also wipe them out entirely, even having succeeded in many places. While some of the thylacine’s closest relatives, like the Numbat and Tasmanian Devil, survived the European persecution which killed off the thylacines, they are still endangered today due to introduced predators and disease. Instead of continuing to search for, or trying to resurrect the lost thylacine, perhaps it is best we channel that attention, love, and regret on the species we still have. Extinction is forever, and it is easier to save those who are still alive.

This art may be used for educational purposes, with credit, but please contact me first for permission before using my art. I would like to know where and how it is being used. If you don’t have something to add that was not already addressed in this caption, please do not repost this art. Thank you!

#Thylacinus cynocephalus#thylacinus#thylacine#tasmanian tiger#tasmanian wolf#marsupials#mammals#synapsids#Australia#Tasmania#Pleistocene#Holocene

16 notes

·

View notes

Note

Talking about dinosaur did you know there were really big wolves around the same time

Even in Japan.

So Japanese samurai Roxy.

Image ID 1: A screenshot of an unknown website that reads, "Yes, dire wolves were around when dinosaurs were not, and they were similar in size to the largest modern wolves.

Explanation

Dire wolves

These wolves lived in North America from about 300,000 to 12,000 years ago. They could weigh up to 148 pounds and grow up to 6 feet long. Dire wolves were about 25% heavier than gray wolves and had larger heads for their body size.

Pleistocene wolves

Some wolves from this period, such as Beringian wolves and those from Japan are larger than modern day wolves."

Image ID 2: Another screenshot of an unknown website that reads,

"Related information

The first dire wolf fossils were found in 1854 from the Ohio River in Indiana.

Some other animals that existed with dinosaurs include crocodiles, snakes, bees, sharks, horseshoe crabs, sea stars, lobsters and duck-billed platypuses.

A prehistoric dog called Hesperocyon had dog-like ears and teeth, but didn't look much like modern dogs."

End of IDs.

Uhhh if those are both from the same website, then it may be AI generated or not very well written. The first sentence on the first image says the dire wolves were not around when dinosaurs were, but the second bullet point on the second image say they were.

I looked it up and uh yeah. The dinosaurs went extinct around 66 million years ago, while the earliest dire wolf skeletons we have date to around 125,000 years ago. These are very different numbers, so much so it would have been impossible for the dire wolf to have existed with the dinosaurs.

The taxonomy of the dire wolf is interesting though. It's not actually a wolf, but it does have a common ancestor to modern wolves we know. They've evolved completely independently to each other, seemingly with no interbreeding either which is really common for canine species to do too.

The Pleistocene Wolf was around in the Pleistocene period which lasted from about 2.58 million years ago, to 11,700 years ago apparently so they're uhh probably off the table here too.

Apparently, it's theorised that the Eucyon is the species that evolved into Pleistocene Wolves and coyote ancestors, and is dated to about 10 million years ago if I'm understanding this right. So it's not looking promising that wolves existed alongside dinosaurs.

On the part about wolves being in Japan, there's the Honshu and Hokkaido wolves. They were both apparently exterminated in the 20th century, but the Hokkaido wolf is said to have maybe lived on the island of Sakhalin until 1945.

Japanese Samurai were a thing in 12th century and abolished in the 1870s, so yeah, historically speaking, you could have Japanese Samurai Roxy.

All this information is from Wiki which is generally pretty good for this stuff, but I'm no expert so if anyone that knows more about any of this wants to weigh in, please do.

This was really interesting to look up I think I might have learned a few things from that so thanks for sending me this!

#friends please if you're going to send me screenshots of information like this can you please copy and paste the words into the ID#the image description button is on every image you upload just copy paste the words into it and make sure the paragraphing is the same#and that's it#blease I would really REALLY appreciate it and will be forever grateful for it#anyway yeah I'm no expert but I don't think wolves of any kind lived with dinosaurs unless you count every bird ever#they DID exist with samurais though so there's that#yippe wahoo?#pop rox answers#I only did so much with IDs by the way I don't really know what I'm doing with them and every time I go to do them I fucking Forget-#-what I did last time so that's not helpful. let me know if I should change it or if anything needs fixing

1 note

·

View note

Text

When we think of suffocation, we often imagine the act of breathing being blocked or restricted, leading to death. But did you know that the direction of suffocation for certain species can actually play a role in their population size and even lead to their extinction?

One such example is the direwolf, a species that lived during the Pleistocene era but became extinct around 10,000 years ago. These impressive creatures, made famous by the popular TV show Game of Thrones, were known for their large size and powerful jaws. But it was their method of suffocation that ultimately contributed to their demise.

Direwolves, like other canids, were pack hunters and relied on their ability to take down large prey for survival. But unlike their modern-day counterparts, such as wolves and coyotes, direwolves had a unique method of killing their prey – suffocation by crushing the windpipe.

According to a study published in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, the direwolf's jaw structure and muscle placement allowed them to exert a significant amount of pressure on their prey's neck, specifically the windpipe. This resulted in a rapid and efficient suffocation, making it easier for a pack of direwolves to take down a larger animal.

But this mode of killing also had its drawbacks. As the majority of direwolves were right-handed, they tended to turn in a counterclockwise direction during their attack, meaning that their crushing pressure was mainly directed towards the left side of their prey's neck and windpipe.

Over time, this constant pressure and suffocation on the left side led to an increase in the left side of the windpipe becoming larger and stronger. This caused the direwolf's suffocating technique to become more and more levorotatory (turning towards the left or counterclockwise) over generations.

So how did this contribute to the direwolf's extinction? Well, as the direwolves continued to evolve and become more efficient in their suffocation methods, their prey also evolved to defend against them. This natural arms race led to an increase in the strength and size of their prey's windpipe, making it more difficult for the direwolves to suffocate them.

But since their suffocating technique was now primarily levorotatory, this made it even harder for them to successfully kill their prey. As a result, the direwolf population began to decline, ultimately leading to their extinction.

While suffocation may seem like a simple and brutal way of killing prey, the direction and frequency of this act can have a significant impact on a species' survival. In the case of the direwolves, their levorotatory suffocation technique played a role in their decline and eventual extinction.

0 notes

Text

The Californian turkey (Meleagris californica) is an extinct species of turkey that lived throughout the West Coast of North America during the Pleistocene and Early Holocene epochs some 2 million to 10,000 years ago. The first remains now known to belong to m. californica consisting of a partial skeleton were unearthed from the la brae tar pits by one Doctor Miller in 1909 who originally described as a type of peafowl and placed in the genus Pavo. Years later Miller reclassified it as an intermediate between the Indian peafowl and the ocellated turkey. Today the Californian turkey is the most common bird found in the la brea tar pits with over 700 individuals having been recovered, and has been determined to be a close relative of modern extant wild turkeys. Reaching around 28 to 45 inches (70 to 114cms) in length and 5 to 20lbs (2.26 to 9.07kgs) in weight, the Californian Turkey was smaller yet stockier than the modern wild and sported a shorter, wider beak. In life Californian turkeys would have lived in familial flocks which spent there days foraging on the ground or climbing shrubs and small trees to feed upon acorns, nuts, pinecones, seeds, berries, buds, leaves, ferns, roots, fruit, insects, and small amphibians and reptiles. While themselves being prey to a litany of predators such as dire wolves, foxes, coyotes, bears, lions, jaguars, cougars, saber toothed cats, eagles, falcons, hawks, badgers, and teratorns. The extinction of this species is thought to have been caused by a combination of drought and overhunting by humans.

Art used above found at the following links

#pleistocene#pleistocene pride#pliestocene pride#pliestocene#ice age#stone age#mesozoic#cenozoic#bird#california#californian turkey#turkey

1 note

·

View note

Text

Terrestrial invertebrates don't fit into any of the categories of people they've introduced already, and I feel like it would be difficult to start and say that they've been around the whole time.

If they introduced a race of terrestrial invertebrates out of nowhere, there would also be the problem that, as nice as bug-themed characters would be... We already have a whooping of at least four races of animal-themed people that have seemingly been completely neglected and forgotten by the game, despite having as much character design potential as any of the other races.

Off the top of my head, we got:

Anura: Frog people, their sole representative in the game being Blue Poison (Who's based on the Poison dart frog). There's so many cool frogs that they could do something with, sure poison dart frogs are cool and it is cool that they are already represented in the game by a cute anime girl, but there's also the Pacman frog, the red-eyed tree frog, the Amazon milk frog, the glass frog, the desert rain frog which I remember being a meme back in the day... Heck, a Tomato frog-based Operator could make for a hilariously clever Trapmaster Specialist concept, or maybe a Defender who can apply some kind of Debuff or Bind effect to enemies who attack them, the possibilities are endless!

Petram: Turtle people, just like the Anura there's only one of them in the whole game, that being Cuora (Asian box turtle). And just like the Anura, there's enough turtles, sea turtles and tortoise species to fill a whole roster, why do we still only have a single one is beyond me.

Cerato: Rhino people, of which again we have only one sole representative, Bubble (White rhinoceros). While rhinos certainly do not have the same ample variety of possibilities to choose from as frogs and turtles, it still feels weird to only have a single one. Also, if camels can count as Forte (Tuye), giraffes can count as Elafia (Mechanist, apparently) and, if Reddit can be trusted with translating lorebook content, coyotes can count as Vulpo (Yes, you read that right)... Then I'm gonna go out on a limb and say that fuck it, tapirs can and should count as Cerato since they are as related to rhinos as giraffes are to deer, so write that down! (And no, Blacknight doesn't count as a tapir, she's a gecko-based Savra with tapir-like pets, her E2 art is very blatant about this)

Pilosa: Sloth people, and yeah you guessed it, there's only one of them in the whole game, that being Scene (Brown-throated sloth). Granted, if rhinos already have a narrow pool to choose from, sloths have even less, and there's only so much you can do with a race that has already been established as being so physically slow, it hinders their ability to verbally speak. That being said... Ok, it is a truly ancient animal that went extinct in the Late Pleistocene and that might open a whole can of worms, but come on, you can't just make a whole race for sloths and sloths only and then not do absolutely anything Megatherium-based, come on now...

...Sorry, this turned into a rant that's only barely related to the original topic. My point was that there should at least be one more of any of these before they add yet another new race to the mix.

A spider character would be really nice, don't get me wrong... But we are also long overdue for at least one new frog character, which we actually know for a fact are already something that exists in the game's world. Like, what happened there.

I can't believe there's no spider character in arknights, one of the more iconic animals to theme an animal-themes character after. Except for... I guess they don't do bugs? Except for some of the sarkaz are a little bit buggy?

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

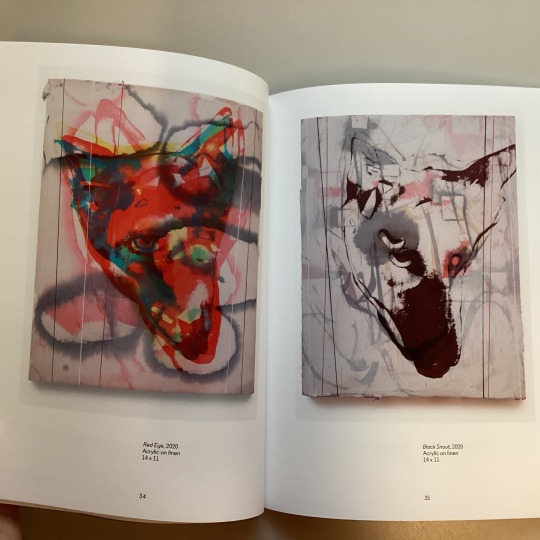

For thirty years, Duane Slick has been creating work that integrates his Native American heritage. In his ongoing painting series that references the coyote, Slick plays with the beauty and the tragedy of his heritage, weaving the mythology and folklore of Indigenous culture with Modernist abstraction style. Like the wolf, the buffalo, and the grizzly bear, the coyote was hunted down and killed by European settlers because of fear for the safety of their livestock. The violence towards these animals parallels the genocide waged against Native Americans in the United States.

“The coyote doesn’t just embody Native America—it is Native America, with the animal’s roots on the continent going back into the early Pleistocene Epoch, two and half million years ago. Slick has taken on the mantle of the coyote to convey both the beauty and the tragedy of his heritage: in the artist’s work there is room for the coyote’s laughter and its tears.” – (Page 6, Richard Klein, Exhibition Director.)

In Slick’s paintings, the coyote speaks.

This November, we are celebrating Native American Heritage Month by sharing some of our new acquisitions for Native American artists, including the exhibition catalog for “Duane Slick : the coyote makes the sunset better,” previously on view at The Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum in Ridgefield, CT.

Image 1: Book cover

Image 2: Left page; “Red Eye,” Right page; “Black Snout,” both Acrylic on linen, 14”x11, 2020

Duane Slick : the coyote makes the sunset better Attribution [essay by curator Richard Klein]. Author / Creator Slick, Duane Ridgefield, Conn. : Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum, 2022. 87 pages : color illustrations ; 28 cm English Published on occasion of the exhibition organized by The Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum, January 16 - May 8, 2022. 2022 HOLLIS number: 99156361672603941

#NativeAmericanHeritageMonth#DuaneSlick#NativeAmericanartist#Contemporaryartist#Coyote#painting#Contemporaryart#HarvardFineArtsLibrary#Fineartslibrary#Harvard#HarvardLibrary#harvardfineartslibrary#fineartslibrary#harvard#harvard library#harvardfineartslib#harvardlibrary

14 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you think trying to domesticate other canids is worth it?

No I don't. Dogs are not only the very first domesticated animal and the only animal domesticated in the Pleistocene, they are also the ONLY large carnivore that has been domesticated in all of human history. I do not believe the unique circumstances that led dogs to exist can happen again and that modern breeding programs trying to domesticate other wild canids will yield animals as suitable for human companionship.

Dogs are also one of the most genetically mutable animals on earth, their genetics mutate incredibly easily in comparison to other species, this is likely why they were not only able to be domesticated, but able to establish themselves as the being to evolve alongside humanity so easily. It's the reason why we can use them for SO many jobs and purposes. In comparison, other domesticated carnivores like cats and ferrets serve more limited purposes.

I don't see an empty niche that domestication of foxes, coyotes, jackles would fill and that means that their domestication would be not purposeful, but for human desire ALONE. Human beings did not see ancient wolves and decide they were going to create a breeding program to develop wolves into dogs, dogs did not exist yet. Dogs and humans evolved together over time and we have a coevolutionary relationship where dogs are now more genetically primed to be our companions and partners. I just don't think we can replicate that and no I don't think it is worth exploring "for science" because it would feasibly take thousands of years of dedicated breeding to get to that point.

#dogblr#faq#nah dogs are special#i also am not particuarly supportive of the russian fox project#bc ultimately the foxes were from fur farms PRIOR to the experiment#where they were already bred for their docile temperaments and color morphs#so the russian experiement doesn't hold much water for me#we can learn so much more about the domestication of dogs from ancient dogs coming out of the permafrost imo

236 notes

·

View notes

Text

wild dog based fantroll names

Aenocy, dierri (dire wolf/Aenocyon dirus)

alpinu, dohlec (dhole/Cuon alpinus)

alstro,halsto,stromi(New Guinea singing dog/Canis hallstromi)

Apenni, apenin (Italian wolf/Canis lupus italicus/Apennine wolf)

archae, haeocy (Archaeocyon/ancient dog. extinct genus of canids from North America)

armbru, ruster(Armbruster's wolf/Canis armbrusteri)

asenar (Asena from turkic foundation mythos)

aureus (golden jackal/Canis aureus. wolf-like canid from Eastern Europe, Southwest Asia, South Asia, and regions of Southeast Asia)

bailey (Mexican wolf/Canis lupus baileyi)

Belize (Belize coyote)

beothu, thucus (Newfoundland wolf/Canis lupus beothucus)

bernar (Bernard's wolf/Canis lupus bernardi)

boerte (boerte chino/mongolian wolf said to have mated with a doe to create the people)

brevis (the Don wolf/C. l. brevis)

Canina (wolf like subtribe)

Canini (dog-like subfamily)

canisu (canis lupus/wolf)

chanco (Canis chanco/Mongolian wolf)

crista, taldii, sicili, ilianu (Sicilian wolf/Canis lupus cristaldii/lupu sicilianu)

durana (Durango coyote)

edward, wardii (Canis edwardii/Edward's wolf is an extinct species of wolf)

eucyon (Eucyon.extinct genus of medium omnivorous coyote-like canid that first appeared in the Western United States)

fenrir,fenris,risulf,roovit,hrovit,nargan,vanarg (fenrir/Fenrisúlfr/Hróðvitnir/Vanargand, is a wolf in Norse mythology)

griseo (Manitoba wolf/Canis lupus griseoalbus)

gronla orioni (Greenland wolf/Canis lupus orion/grønlandsulv)

hattai (Hokkaido wolf/Canis lupus hattai)

hesper,perocy,erocyo (Hesperocyon/Hesperocyoninae. extict canine from north america)

hropos (werewolf/werwulf/lycanthrope)

iliari (dingo/Canis familiaris dingo)

laskan,pambas,basile,sileus (Interior Alaskan wolf/yukon wolf/Canis lupus pambasileus)

latran (Canis latrans/coyote)

leptos (The genus Leptocyon/leptos slender + cyon dog)

lorida (Florida black wolf/Canis lupus floridanus)

lupast,paster(African wolf/Canis lupaster)

Lupule, adusta (side-striped jackal/Lupulella adusta)

Lycaon, pictus(African wild dog/Lycaon pictus)

medein,edeina,vorune (Medeina/forest mother/zvorune/zvoruna from lithuania)

merico (Megacyon merriami/Merriam's dog. extinct dog from indonesia)

mesome, omelas ( black-backed jackal/Lupulella mesomelas)

mosbac (Canis mosbachensis/Mosbach wolf. extict eurasia wolf)

okamin, hodoph, philax, honshu (Japanese wolf/Nihon ōkami/Canis lupus hodophilax/Honshū wolf)

opokam, pokami (opo-kami, later turned into okami meaning wolf)

orcuti (Pleistocene coyote/Canis latrans orcutti)

protel, crista,istata (aardwolf/Proteles cristata)

Protoc,tocyon(Protocyon/extinct genus of canid from South and North America)

pulell, upulel (genus of canine from africa)

rabili (Texas wolf/Canis lupus monstrabilis)

remotu (northern Rocky Mountain wolf/Canis lupus irremotus)

rocyon, Nurocy, chonok, harien, iensis (Nurocyon chonokhariensis, extinct dog)

rukhan,turukh (tundra wolf/Canis lupus albus/Turukhan wolf)

sardou, theriu(Sardinian dhole/Cynotherium sardous, extinct canid from italy and france)

sekowe, ekoweic (genus that includes african wild dogs)

skoull (skoll/Treachery/Mockery is a wolf that chases the Sun in norse mythos)

socyon, brachy, hyurus (Chrysocyon brachyurus/maned wolf)

spelae, pelaeu(cave wolf/Canis lupus spelaeus)

speoth, peotho (Speothos/bushdog)

telocy (Atelocynus microtis/short eared dog)

tereut,tanuki,reutes (Nyctereutes/tanuki, raccoon dog)

tolina (Capitoline Wolf/Lupa Capitolina. wolf mother to the mythical founders of rome)

trinil (Mececyon trinilensis/Trinil dog. extinct canid species from Indonesia)

tundra,drarum,undrar(Alaskan tundra wolf/Canis lupus tundrarum)

usicyo,ustral (Dusicyon australis/extinct genus of South American canids)

vargar, wargoe (vargr/warg, wolves used in norse mythos)

vilkas, gelezi,exinis (The Iron Wolf/Geležinis Vilkas)

vitnis,nisson,hroovi,hatiho (Hati Hróðvitnisson. wolf who chases the moon in norse mythos)

vukoda,kodlak (vuko-dlak/wolf-furr. slavic werewolf)

wuchar,charia,ouchan,akhata,khatar,kebero,binawa,kyarke,dhahab,bukhar (African wolf/Canis lupaster which has many indiginous names in different parts of africa which ive pulled these names from)

wulfaz (proto germanic for wolf)

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

Death is Natural, Right?

Death is natural, right? Feline halitosis one can smell from yards away, the stench of quick-approaching mortality. The aroma swells and dissipates in sickly sweet cession. In a way he is still beautiful in a juxtapose sort of way, like the Titan arum or the word “metastasized.” He is still as he was as a young kitten, his hair silky soft and as dark as the April night. Understanding comes as soon as the smell, it is his time.

There is no fear or panic, just acceptance. What is done cannot be undone. There is still shock, no doubt; the shaking and asphyxia is hard to take in. The breathing that sounds just like steel nails on 50-grit. Recalling the short-lived yelp and the convulsing like a shiver going up one’s spine. That sick feeling spins a web of guilt, “could I have done anything more?”. The answer is well… sometimes.

Death is natural, right? The gaunt appearance of a friend once young, seemingly out of nowhere. Once agile and quick, now contracted and sick. Nature can nurture; however, nature can kill. Air so cold, one could swear it was the age of the Pleistocene. Wind howling like the coyotes on a warm summer’s night. He takes a deep breath and chokes on the nurturing care of nature, pleas never heard over the howling white snow. The cat was under the stairway, cold as ice but looked just as pleasant as when he sat by the warm, crackling fireplace. As quoths the Raven, “Nevermore.”

Acceptance is a hard thing to acquire when he was there just yesterday, as normal as ever. Anger and sadness burn like acid through hearts and eyes. Guilt weighs heavy like a cinder block on a balloon. Nothing is like it was before. His hair is coarse, his joints are stiff (as it has been less than the allotted 24 hours). No closure, one can only feel helpless.

But death is natural, right?

#wrote this for college#poetry#poetry is subjective#is this even poetry#about my dead cats :(#wrote this in 40 minutes#descriptive paper#similies#i like metaphors#metaphors#this is so bad please

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

A VERY DESCRIPTIVE PROFILE OF YOUR MUSE.

repost with the information of your muse, including headcanons, etc. if you fail to achieve some of the facts, add some other of your own !

NAME. None; often goes by “Invy.”

AGE. 2 Million years old (Born during the pleistocene epoch)

SPECIES. Devil; Coyote formerly

GENDER. Non-binary

ORIENTATION. pansexual

INTERESTS. Exploration, arts, hunting, survival, socializing

PROFESSION. Hand of God & Servitor to the Goddess of Envy

BODY TYPE. Emaciated

EYES. Green; only one.

HAIR. Black.

FACE. Thin, with large eyes, a slightly pointed nose and thin lips.

HEIGHT. Coyote: 18″/ F: 5′0-5′2 / M:6′0 / Monster: 10′5′’

COMPANIONS. Three intellect parasites that live within her body; Eldest primarily.

ANTAGONISTS. Most everyone

COLORS. Greens, reds

FRUITS. Strawberries, dragon fruit, mangos.

DRINKS. Water, some teas, lemonade, cider

ALCOHOLIC BEVERAGES? Do not have an affect; drinks for effect

SMOKES? No

DRUGS? Sometimes.

DRIVERS LICENSE? No

tagging: You~

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

went back and added a couple guys since I'd like to do them in order from here out

gonna work on a size chart of all my guys during my downtime

104 notes

·

View notes

Photo

these are maned wolves (my ocs from wolfwalker ) and are not a mother and her cub, but two friends. 👍🥰😁🧡

about maned wolf:

Guara wolf From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia How to read a taxonomy infoxoxy-maned wolf [1] Occurrence: Pleistocene - Recent Maned wolf in the Serra da Canastra National Park Maned wolf in the Serra da Canastra National Park conservation state Almost threatened Almost threatened (IUCN 3.1) [2] Scientific classification Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Chordata Class: Mammalia Order: Carnivora Family: Canidae Genre: Chrysocyon Smith, 1839 Species: C. brachyurus Binomial name Chrysocyon brachyurus Illiger, 1815 Type species Canis jubatus Desmarest, 1820 Geographic distribution Maned Wolf range.png Synonyms [3] Canis brachyurus Illiger, 1811 Canis campestris Wied-Neuwied, 1826 Canis isodactylus Ameghino, 1909 Canis jubatus Desmarest, 1820 Vulpes cankerosa Oken, 1816 The maned wolf (scientific name: Chrysocyon brachyurus) is a species of canid endemic to South America and the only member of the genus Chrysocyon. Probably the closest living species is the vinegar dog (Speothos venaticus). It occurs in savannas and open areas in central Brazil, Paraguay, Argentina and Bolivia, being a typical animal of the Cerrado. It was extinct in part from its occurrence to the south, but it must still occur in Uruguay. On July 29, 2020 the maned wolf was chosen to symbolize the two hundred reais bill.

It is the largest canid in South America, reaching between 20 and 30 kg in weight and up to 90 cm at the height of the withers. Its long, slender legs and dense reddish coat give it an unmistakable appearance. The maned wolf is adapted to the open environments of the South American savannas, being a twilight and omnivorous animal, with an important role in the dispersion of seeds of fruits of the cerrado, mainly the lobeira (Solanum lycocarpum). Lonely, the territories are divided between a couple, who are in the period of the female's estrus. These territories are quite wide, and may have an area of up to 123 km². Communication takes place mainly through scent marking, but vocalizations similar to barking also occur. Gestation lasts up to 65 days, with black newborns weighing between 340 and 430 g.

Despite not being considered in danger of extinction by the IUCN, all the countries in which it occurs classify it in some degree of threat, although the real situation of the populations is not known. It is estimated that there are about 23 thousand animals in the wild, being a popular animal in all zoos. It is threatened mainly because of the destruction of the cerrado to expand agriculture, pedestrian accidents, hunting and diseases caused by domestic dogs. However, it is adaptable and tolerant of changes caused by humans. The maned wolf currently occurs in areas of Atlantic Forest already deforested, where it did not originally occur.

Some communities carry superstitions about the maned wolf and may even harbor a certain aversion to the animal. But in general, the maned wolf provokes sympathy in humans and is therefore used as a flag species in the conservation of the Cerrado.

Index 1 Etymology 2 Taxonomy and evolution 3 Geographic distribution and habitat 4 Description 5 Behavior and ecology 5.1 Diet and foraging 5.2 Territory, area of life and social behavior 5.3 Reproduction and life cycle 6 Conservation 7 Cultural aspects 7.1 Representations in cash 8 References 9 External links Etymology The maned wolf is also known as maned, watered, aguaraçu, mane wolf, mane wolf or red wolf. [4] [5] The term wolf originates from the Latin lupus. [4] Guará and aguará originated from the Tupi-Guarani agoa'rá, "down hair". [6] Aguaraçu came from the term for "guará grande". [4] Tupi-Guarani names of origin are more common in Argentina and Paraguay (aguará guazú), but other Spanish-speaking countries have other names like boroche in Bolivia and wolf of crin in Peru. [7] Lobo de crin (in Spanish) and maned wolf (in English) are allusions to the mane of the nape of the neck. [7]

Taxonomy and evolution

It is one of the endemic canids of South America. Phylogenetic relationships of South American canids. [8]

Chrysocyon brachyurus - maned wolf

Speothos venaticus - vinegar dog

Atelocynus microtis - short-eared bush dog

Cerdocyon thous - bush dog

Lycalopex genus - South American foxes

Phylogeny inferred from mitochondrial and nuclear DNA data. The species was described in 1815, by Johann Karl Wilhelm Illiger, initially as Canis brachyurus. [3] Lorenz Oken classified it as Vulpes cancosa, and only in 1839, Charles Hamilton Smith described the genus Chrysocyon. [3] Later, other authors considered him to be a member of the genus Canis. [3]

Despite having belonged to the genera Canis and Vulpes, due to their morphological similarities, the maned wolf is not closely related to these genera. [9] Molecular studies have shown no relationship between the Chrysocyon genus and these canids. [8] [10] The maned wolf is one of the endemic canids of South America, along with the bush dog (Cerdocyon thous ), the vinegar dog (Speothus venaticus) and the genus Lycalopex. [8] Such a group is monophyletic according to genetic studies, but morphological studies include Nyctereutes procyonoides, who is originally from Asia. [8]A study comparing the brain anatomy of several canids, published in 2003, placed the maned wolf as akin to the falkland fox (Dusicyon australis) and the genus Lycalopex (considered by the authors as Pseudalopex). [11] Molecular studies corroborate that the maned wolf has a unique common ancestor with the falkland fox, which lived approximately 6 million years ago. [12] [13]However, recent genetic studies place the maned wolf as the closest phylogenetically to the vinegar dog (Speothos venaticus), forming a clade that is a sister group to another to which all other South American canids belong, such as the canine dog. short-eared bush (Atelocynus microtis), the bush dog (Cerdocyon thous) and the genus Lycalopex. [8] [10] This clade diverged from other South American canids about 4.2 million years ago, and the Chrysocyon and Speothos genera diverged about 3 million years ago. [8]Not many maned wolf fossils are known and those that were discovered originate from the Holocene and the Upper Pleistocene, unearthed in the Brazilian plateau, indicating that the species also evolved only in the open areas of Central Brazil. [14] Nor are subspecies recognized. [15]Geographic distribution and habitatThe Cerrado is the main habitat of the maned wolf. The maned wolf is an endemic canid from South America and inhabits the grasslands and thickets of the center of that continent. Its geographic distribution extends from the mouth of the Parnaíba River, in the Northeast of Brazil, through the lowlands of Bolivia, east of the Pampas del Heath, in Peru and the Paraguayan chaco, to Rio Grande do Sul. [3] Evidence of the maned wolf's presence in Argentina can be found up to Parallel 30, with recent sightings in Santiago del Estero. [2] Probably the maned wolf still occurs in Uruguay, given that a specimen was spotted in 1990, but since then there has been no record of the species in the country. [2]It is a fact that the maned wolf has disappeared in many regions at the southern limits of its geographical distribution, occurring almost only up to the border of Rio Grande do Sul with Uruguay. [16] Interestingly, the deforestation of the Atlantic Forest in the southeastern and eastern regions of Brazil favored the expansion of its geographic distribution to areas where it did not previously inhabit. [16] For this reason, records in Atlantic Forest areas in Paraná, São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro and Minas Gerais have increased in recent years. [5] In the Pantanal the maned wolf occurs in highlands in the upper Paraguay, but avoids the lowlands of the Pantanal plain. [5] There are sporadic records of the species in transition areas between the Cerrado and the Amazon and the Caatinga. [5] The species can occur above 1,500 meters in altitude. [5]The maned wolf habitat is mainly characterized by open fields, with shrub vegetation and forest areas with open canopy, being a typical animal of the Cerrado. [15] It can also be found in areas that experience periodic flooding and man-made fields. [15] The maned wolf prefers environments with a low amount of shrubs and sparse vegetation. [15] More closed areas are used for rest during the day, especially in regions that have been greatly altered anthropically. [17] In these altered areas it can be seen in cultivated fields, Eucalyptus plantations and even in suburban areas. [18] Although the species can occur in anthropic environments, further studies are needed to quantify the degree of tolerance of the maned wolf to agricultural activities, but some authors suggest the preference for areas modified by man as opposed to well-preserved forest areas. [5] [15]DescriptionThe skull is similar to that of the wolf and the coyote. It is the largest canid in South America, reaching between 95 and 115 cm in length, with a tail measuring between 38 and 50 cm in length and reaching up to 90 cm at the height of the withers. [15] It weighs between 20.5 and 30 kg, with no significant differences in the weight of males and females. [15] It is an animal difficult to confuse with other South American canids, because of its long and thin legs, dense reddish coat and large ears. [15] The species' slender shape is probably an adaptation to displacement in open areas covered by grasses. [3]It is unmistakable among South American canids, being the largest among them. The body coat varies from golden red to orange and the hairs on the back of the neck and feet are black, with no undercoat in the coat. [3] The lower part of the jaw and the tip of the tail are white. [3] The hairs are long, reaching up to 8 cm in length along the body, forming a type of mane on the animal's neck. [7] There is almost no variation in the color of the coat, and it is not possible to identify individuals or sex from hair color, although an entirely black individual has already been recorded in northern Minas Gerais. [7] [19]The shape of the head looks like that of a fox. The snout is slender and the ears are large. [3] However, the skull is similar to that of the wolf (Canis lupus) and the coyote (Canis latrans). [3] The skull also has a prominent sagittal crest. The butcher tooth is reduced, the upper incisors small and the canines long. [3] Like the other canids, it has 42 teeth with the following dental formula: {\ displaystyle {\ tfrac {3.1.4.2} {3.1.4.3}} \ times 2 = 42} \ tfrac {3.1.4.2} {3.1.4.3} \ times 2 = 42 [20] Similar to the vinegar dog (Speothos venaticus), the maned wolf's rhyme extends to the upper lip, but the vibrissae are longer. [3]The maned wolf's footprints are similar to those of the dog, but have the pads disproportionately small when compared to the digits of the digits, which are wide open. [21] [22] The dog has foot pads up to 3 times larger than the maned wolf's footprints. [22] These pillows are triangular in shape. [22] The front footprints are between 7 and 9 cm long and 5.5 and 7 cm wide, and those on the back legs are between 6.5 and 9 cm long and 6.5 to 8.5 cm wide. [22 ] A characteristic that differentiates the maned wolf's footprints from that of other South American canids is the proximal union of the third and fourth digits. [3]Geneticame n the maned wolf has 38 chromosomes, with a karyotype similar to that of other canids. [3] Genetic diversity suggests that 15,000 years ago the species suffered a reduction in its diversity, called the bottleneck effect. Even so, this genetic diversity is greater than that of other canids. [5]average 0.7 seconds in 2 to 4 second intervals, a sequence that is repeated for up to 23 times. [7] Both males and females vocalize. [7] They tend to vocalize more at night, when they can be heard from several meters away. [35] Despite being associated with territoriality, vocalizations are more frequent among young people from the same territory, suggesting that they are only a sign for contact over great distances between known individuals and not for the defense of territory. [35]Direct social interactions are rare and maned wolves seem to avoid each other. [7] Agonistic encounters are rare but occur mainly between males, and have not been seen among females. [32] This results in almost no overlap in the male territories. [32]

Reproduction and life cycle

The puppies are born weighing between 340 and 430 g and have a reddish coat after the tenth week As in the diet, most of the data on the maned wolf's estrus and reproductive cycle comes from animals in captivity, mainly on the endocrinology of reproduction. [33] However, studies of animals in freedom have found that hormonal changes follow the same pattern of variation as animals in captivity. [33] At first females spontaneously ovulate, but some authors suggest that the presence of a male is important for estrus induction. [33]

Captive animals in the northern hemisphere breed between October and February and in the southern hemisphere between August and October. This indicates that the photoperiod has an important role in the reproduction of the maned wolf, mainly due to the production of semen. [3] [33] Usually estrus occurs annually [3] and the amount of sperm produced by the maned wolf is less when compared to that of other canids. [33]

Copulations take place during the 4-day period of estrus and are followed by up to 15 minutes of copulatory engagement. [3] The courtship behavior is no different from that of other canids, characterized by frequent approximations and anogenital investigation. [26]

The gestation lasts about 65 days, being born between 2 and 5 puppies, but 7 puppies have already been registered. [3] Births in May have already been observed in the Serra da Canastra, but captivity data suggest that births are concentrated between June and September. [5] The few data available on reproduction in the wild show that the maned wolf reproduces with difficulty and the mortality of young is high. Females can stay up to 2 years without reproducing. [33]

In captivity, reproduction is even more difficult, especially in temperate countries in the northern hemisphere. [33] The puppies are born weighing between 340 and 430 grams, black and changing to a reddish color after the tenth week. [3] The eyes open at about 9 days of age. [3] They are breastfed up to 4 months and fed by their parents through regurgitation until 10 months, starting at the 3rd week of age. [25] [26] At three months of age the puppies accompany the mother while she forages. [25] Parental care is shared between male and female, but females do this more often. [25] Data on male parental care have been collected from captive animals, and little is known about whether this occurs frequently in wild animals. [26] Sexual maturity is reached at 1 year of age and after that age they leave the territory in which they were born. [26]

youtube

#lobos#lobo guará#lobos guarás#guara wolf#wolf#wolf art#wolf oc#my wolf#lobos oc#my drawimg#drawing#drawing cute#my drawing#digital art#my oc digital#digital#art digital#art#my art#my oc#my oc art#oc#ocs#wolfwalkers#wolfwalkers oc#wolfwalkers ocs

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

This 12,000-year-old fossil jaw could be the oldest known dog in the Americas

https://sciencespies.com/humans/this-12000-year-old-fossil-jaw-could-be-the-oldest-known-dog-in-the-americas/

This 12,000-year-old fossil jaw could be the oldest known dog in the Americas

The fossil of a jaw bone could prove that domesticated dogs lived in Central America as far back as 12,000 years ago, according to a study by Latin American scientists.

The dogs, and their masters, potentially lived alongside giant animals, researchers say.

A 1978 dig in Nacaome, northeast Costa Rica, found bone remains from the Late Pleistocene.

Excavations began in the 1990s and produced the remains of a giant horse, Equus sp, a glyptodon (a large armadillo), a mastodon (an ancestor of the modern elephant) and a piece of jaw from what was originally thought to be a coyote skull.

“We thought it was very strange to have a coyote in the Pleistocene, that is to say 12,000 years ago,” Costa Rican researcher Guillermo Vargas told AFP.

“When we started looking at the bone fragments, we started to see characteristics that could have been from a dog.

“So we kept looking, we scanned it… and it showed that it was a dog living with humans 12,000 years ago in Costa Rica.”

The presence of dogs is a sign that humans were also living in a place.

“We thought it was strange that a sample was classified as a coyote because they only arrived in Costa Rica in the 20th century.”

First of its kind

The coyote is a relative of the domestic dog, although with a different jaw and more pointed teeth.

“The dog eats the leftovers from human food. Its teeth are not so determinant in its survival,” said Vargas.

“It hunts large prey with its human companions. This sample reflects that difference.”

Humans are believed to have emigrated to the Americas across the Bering Strait from Siberia to Alaska during the last great ice age.

“The first domesticated dogs entered the continent about 15,000 years ago, a product of Asians migrating across the Bering Strait,” said Raul Valadez, a biologist and zooarcheologist from the National Autonomous University of Mexico.

“There have never been dogs without people,” Valadez told AFP by telephone.

The presence of humans during the Pleistocene has been attested in Mexico, Chile and Patagonia, but never in Central America, until now.

“This could be the oldest dog in the Americas,” said Vargas.

So far, the oldest attested dog remains were found in Alaska and are 10,150 years old.

Oxford University has offered to perform DNA and carbon dating tests on the sample to discover more genetic information about the animal and its age.

The fossil is currently held at Costa Rica’s national museum but the sample cannot be re-identified as a dog without validation by a specialist magazine.

“This dog discovery would be the first evidence of humans in Costa Rica during a period much earlier” than currently thought, said Vargas.

“It would show us that there were societies that could keep dogs, that had food surpluses, that had dogs out of desire and that these weren’t war dogs that could cause damage.”

© Agence France-Presse

#Humans

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Started a new novel, since I still feel weird releasing my zombie novel in the middle of a global pandemic. So, enjoy this free sneak peak at my prologue.

Coyote Flats had been built on 312 graves.

Not many people knew this, of course. If they did they wouldn't have moved to the small town when the boom hit in the early eighties.

Situated in a large basin at the bottom of a valley, Coyote Flats was farmland mostly. Canadian prairie grass grew at the top of the valley, the bottom of which was a large alkali salt plain where the creature for which the Flats was named roamed freely.

In 1978 a cattle farmer digging a well in the basin hit a piece of bone, digging up a mammoth in what would be the first of many late Pleistocene fauna.

That was the cause of the second boom of Coyote Flats.

Before that it was dried up and dead, had been since the thirties when the topsoil blew away from the rich earth at the top of the valley.

Now it was tourist town, small enough that it still had it's dignity. It wasn't trinkets and toys like some of the other dinosaur riddled small towns that dotted the prairies, but it still drew a crowd.

Seven thousand people resided within the Flats, half of that in the surrounding area, so it wasn't ever big, just big enough.

Within the town limits, past the Minnie the Mammoth statue by the highway sign, were homes built in the early eighties, peppered throughout with older homes. The front enclosed porch homes of 1912, the wide and squat bungalow homes of the 1920's and three large red bricked buildings in the centre, huddled around the park.

If one knew about the 312 buried beneath the Coyote Flats Park, then they would also know that McAllister Funeral Home to the east had always been a mortuary, that the Town Hall to the north was once a sanatorium where tuberculosis patients from all across the northern prairies went to seek medical help and rest, before ultimately dying of the white plague in the early days of the twentieth century and that St. Bernadine's Roman Catholic Church, in the south-west of the park had always been the church that offered sanctuary for the dying.

These buildings were the oldest in Coyote Flats.

The oldest residents, outside of the McAllister sisters themselves who lived in a turn of the century Victorian style home just east of the park, beside the funeral home that shared their name, though was never owned by them. No, these women, white witches teased by some, were members of the one of the oldest families in the Flats. Nearly a quarter of the town shared the name McAllister with them, though none were progenitors of these women as they were all single matrons, old maids as they were once called.

They lured both men and women, young and old, into their open home with the scent of sweets baking on a warm summer's eve, or the promise of good gossip, tea and maybe a home remedy or two.

When the wind blew from the south, they'd say, love will kiss thee on the mouth.

Oh Bonny Portmore, Charity McAllister, could be heard singing from their front porch on a quiet afternoon as she tended her window box flowers, I am sorry to see, such a woeful destruction of your ornament tree. For it stood on your shore for many a long day, til the long boats from Antrim came to float it away.

These women, tended to by their great grand-niece, granddaughter of their oldest sister Grace, may she rest in peace, were some of the only who knew about the 312.

Inside the brick building to the north, deep in the basement of the Town Hall, Eddie Hollander was another who knew of the 312. He knew because he worked the historical archives, he lived among papers and files and microfiche, he had gone to university to become a historian, only to be shoved down into the bowels of Coyote Flats where no one came, no one visited, no one seemed to care.

He lived, oddly enough, beside the McAllisters on Diefenbaker Avenue, just east of the park. From his front porch, as from the McAllister's, he saw the birch stand that separated the park from the rest of the world.

If he peered hard enough through the black and white trunks of the trees, he could see the back of St. Bernadine's. In the winter, he didn't have to peer much at all, the red brick building standing out against the white of the snow.

While the church became clear to see in the winter, the white marble angel behind it blended in.

She stood eight feet tall, eleven feet counting the pedestal beneath her sandaled feet, arms reaching out to the heavens in abject grief, wings spread tall and wide.

Anyone who knew about the 312, knew why this angel stood there behind the church. Those who didn't, assumed she was just some pretty piece of statuary in the park, confused, maybe, about why she stood behind the church and not in front of it or beside it.

But for as confused as people were about the placement of the white angel, they were just as confused about the black marble angel.

He knelt on his pedestal, about three hundred yards north from the church, backed by the birch stand that swooped in beside him and around to shield him from the bitter winds coming from the east and the north. The winds that brought visitors and storms, according to the McAllister sisters.

This angel was militant and vengeful looking.

His hood hid most of his features from the world, though anyone who really dared to peer into the shadows of the hood said he was sometimes disapproving, sometimes amused. With a sort of patrician nose in the classical style and piercing eyes carved into the cold stone, he was hunched on one knee, arm raised with a flaming sword in it, prepared for the kill. Wings spread intimidatingly or perhaps even in preparation for a flight into battle

He was frightening to children, threatening to men and abhorrent to women (though some would say he had an oddly thrilling charm about him).

Perhaps aware of this, the town council tried to beautify him somewhat, they planted wave petunias in a flowerbed at the base of his pedestal in the hopes of softening the threat.

He only seemed to drop his gaze to them in silent annoyance.

In the morning he was placid, almost smiling, by noon he was scowling, aggressive, before becoming a mild warrior of God once more in the evening.

Most didn't dare get close to him come nightfall, however. It just wasn't done.

No one entered the park at night, they didn't know why, they just knew it gave them odd feelings and sensations.

If you timed it just right, on a peaceful evening in mid-summer in Coyote Flats. Standing before the black angel with your back to him, gazing across the well trimmed grass to where the church stood shielding the white angel from MacKenzie-King Avenue in the west, you could be lucky enough to hear both Charity McAllister singing and the sound of a small town in the dying light of the sun. And you would forget, for a moment, the eerie feeling that crept upon you, standing in a park in the middle of Coyote Flats proper which was once a cemetery where 312 were buried.

#this is a chance for all my followers who post about supporting authors and creators to put their money where their mouths are#support me guys#need it#getting laid off from work#so i need to kick ass on this proper like and make some money from my writing#coyote flats#enjoy this free sneak peak#and if you do happen to like my work visit my actual tumblr page to donate to a struggling author#this has not been edited#lazy

72 notes

·

View notes

Text

So there’s this idea that aliens would find Earth frightening, the name for which is “Space Australia”.

Go look up how many deaths per capita are caused by wildlife in the US, vs. Australia. They have a couple spiders, a couple snakes, jellyfish, sharks, crocodiles, and maybe emus and a couple kinds of kangaroo, though I don’t know of those ever killing anyone. We have almost as many spiders (and ours are much smaller and therefore easier to accidentally get bitten by), at least one scorpion, almost as many snakes, alligators, sharks…and then mule and whitetail deer, elk, moose, javelinas, pumas, lynxes, bobcats, jaguars (they haven’t killed anyone here though), brown, black, and polar bears, buffalo, muskox, sea lions, walruses, orcas, mountain goats, bighorn sheep, wolves, coyotes, and the same jellyfish as Australia (albeit only in Hawaii).

My point is, maybe aliens’ homeworld is like Earth was in the Pleistocene. Or the Cretaceous. Maybe instead of the occasional hiker or dumb hippie getting mauled by a grizzly, they have the occasional Giganotosaurus coming down from the hills to raid an entire homestead for food. Maybe instead of getting killed getting too close to deer, they get killed because they walked 20 meters behind a nervous Diplodocus and got cut in half by its tail-whip. Why would you assume an alien’s biosphere isn’t at least as deadly as ours is? All the biological rules that operate here are just special cases of the laws of thermodynamics, and thermodynamics operates everywhere. So aliens’ biosphere is not going to be a lovefest. It’s going to be just as “red in tooth and claw” as ours is (except maybe their blood is a different color and they use something other than teeth or claws). And they might not have had the luxury of the end of a Glacial Maximum killing off many of the large dangerous creatures (with their hunter-gatherer ancestors finishing the job on many others); they might not even have enjoyed a Chicxulub impact killing off the serious motherfuckers.

For all you know, Earth is Space Western Europe.

#scifi worldbuilding#salty scifi writer#salty science fiction writer#salty sf writer#last time spider-bite killed someone in australia was 1979#three people a year die from spider-bite in the us#humans are space hobbits#space western europe

23 notes

·

View notes