#petit peuple

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

De Emma à Bruce

Cher Bruce,

Bruce, Bruce, Bruce. Continuerai-je à écrire sur tes pages quand tout aura été rénové ? Quand le quotidien aura retrouvé un air de normalité ? Ou bien la normalité est-elle perdue – la fissure dans le monde des Nephilim est-elle irréparable, ne fera-t-elle que s’agrandir avec le temps, apportant de plus en plus de changements, jusqu’à ce qu’il y ait finalement trop de changements pour que ce soit supportable ? Auquel cas, je suppose que je continuerai de t’écrire, Bruce, comme à un témoin silencieux de l’étrangeté de cette époque.

Désolée, désolée. Je suis d’humeur un peu poétique ce soir parce que Jem, Tessa, Kit et Mina sont arrivés aujourd’hui et… eh bien, c’est un peu de cette façon que Jem et Tessa s’expriment. Vu qu’ils sont, tu vois… hyper vieux. Et parce que j’ai l’impression que nous en arrivons aux derniers chapitres de toute cette histoire de maison maudite et je n’ai pas la moindre idée de ce que l’avenir nous réserve.

Quoi qu’il en soit, nous ne nous sommes pas intéressés à la malédiction aujourd’hui, nous avons simplement passé du temps avec les Carstairs-Herondale, qui devraient certainement choisir un nom plus court par lequel nous pourrions les désigner. Team Ere Victorienne ? Team Époque Où Tout Était Très Romantique Mais Aller Où Que Ce Soit Prenait Une Éternité ? Hum. Je pense que je leur demanderai s’ils ont des idées, puisque les miennes sont… euh… mauvaises.

Nous avons rencontré quelques complications quand ils sont arrivés. Nous avions choisi des chambres pour eux et avions demandé aux brownies de les préparer, d’y mettre des draps et des serviettes et tout ce qu’il faut. Et puis nous étions allés vérifier avant l’arrivée de nos invités. Et je suis contente de l’avoir fait parce que les fées avaient préparé toutes les chambres pour… des oiseaux ? Genre, des oiseaux immenses, à taille humaine. Avec des nids gigantesques, de presque deux mètres, et des branches en guise de perchoirs. Et d’énormes boules de graines pendaient du plafond. Nous avions donc dû demander à des brownies très déçus de refaire les chambres. (Mais nous n’avions pas dit que les invités étaient des oiseaux ! Je ne sais pas du tout pourquoi ils ont cru ça !) Le pire dans tout ça, c’est qu’ils avaient vraiment fait du bon travail : si ça avait bien été d’immenses oiseaux qui nous rendaient visite, ils auraient été très à l’aise. Ils ont quand même été confus quand tout le monde est arrivé en voyant que Mina n’était pas un gros œuf. Les fées, je te jure.

En parlant de Mina, qui n’est pas un gros œuf mais une petite bambine, elle est absolument adorable. Elle marche maintenant, ou plutôt fait des premiers pas hésitants, et elle dit « mama » et « papa » et aussi « kish » pour appeler Kit semble-t-il. Et elle a une petite stèle en bois avec laquelle elle essaye tout le temps d’écrire sur tout le monde. Apparemment Kit apprend les runes et Mina veut les apprendre aussi.

Nous aurions tout de suite dû nous atteler à la malédiction mais honnêtement nous passions un si bon moment tous ensemble. C’est très agréable de passer du temps avec Tessa et Jem, ce qui change de la nervosité de la plupart de nos autres amis. Je suppose qu’avec tout ce qui leur est arrivé, il en faut beaucoup pour les contrarier. La simple manière dont Jem parle de la malédiction m’aide beaucoup à croire que nous pourrons arranger la situation, même si nous ne savons pas vraiment ce que nous faisons ni ce que nous avons mal fait jusque-ici.

Ils ont aussi l’air vraiment impressionnés par la maison. Julian a l’air tout fier de lui, c’est hyper mignon. Tessa s’est remémoré que la dernière fois qu’eux deux étaient venus, c’était après que Tatiana ait été arrêtée et envoyée à la Citadelle pour devenir une Sœur de Fer. Ils fouillaient le manoir à la recherche d’activités démoniaques. (Bien sûr, ils n’ont presque rien trouvé, a-t-elle admis. Au ton de sa voix, il semblait évident qu’ils n’avaient compris le danger que représentait Tatiana que lorsqu’il était trop tard. Je voudrais bien lui poser des questions à ce sujet, mais ça me semblait être de tristes souvenirs alors que nous passions tous un bon moment.) Jem a remarqué qu’à cette époque la propriété était déjà en mauvais état, mais Tessa a révélé qu’elle avait vu la maison « à son apogée » lors d’un bal, puis elle a rougi un peu. Ce qui s’est passé pendant ce bal devait être assez mémorable pour que ça la fasse rougir 130 ans après !

Évidemment, il y a toujours cette espèce de lourd stigmate qui recouvre la maison comme un linceul, et ce ne sont pas des murs repeints et des fenêtres remplacées qui changeront ça. C’est à cause de la malédiction. Mais cette soirée était toute de même la plus joviale que j’aie connue ici. Pour la première fois, j’avais un peu l’impression que c’était notre maison, que des amis étaient venus nous rendre visite et c’était étonnement sympa et ordinaire. Tant que je ne pense pas à ce qu’il se passe avec l’Enclave.

Une inquiétude : Kit. Il est resté avec nous une bonne partie de la journée, mais il était anormalement calme, et il s’est excusé deux fois pour aller faire un tour dans le jardin. D’après Julian, Kit a rompu avec sa petite-amie et c’est peut-être ce qui le rend triste, mais je n’en suis pas sûre. Il était très nerveux en présence des entrepreneurs et il les surveillait de près dès qu’ils étaient dans les environs. Round Tom s’est présenté et Kit a hoché la tête sans rien dire, même pas son nom. Enfin, on ne peut pas vraiment lui en vouloir. Sa relation avec les fées, et avec le Royaume des Fées, est compliquée. Tessa a expliqué que Cirenworth est exceptionnellement protégé contre les intrusions féériques, de même que la ville et les routes proches. Magnus et Catarina s’en sont assurés. C’est donc l’une des premières fois qu’il est en compagnie d’elfes depuis la grande bataille aux abords d’Alicante. Même si ces fées-là ne sont pas dangereuses, ça doit être bizarre pour lui.

Mais tu connais Kit. Il donne l’impression qu’il ne veut répondre à aucune question au sujet de comment il va. Aujourd’hui, il était sur le qui-vive, à regarder les elfes dans le jardin : peut-être qu’ils l’inquiètent, ou peut-être qu’il veut les rejoindre ? Je ne sais pas. Peut-être que Julian et moi pourrons le faire parler un peu pendant son séjour ici. Ou peut-être que j’aurai l’occasion de demander à Jem et Tessa s’ils savent ce qu’il se passe.

Bref, c’est tout ce que j’ai à te dire pour l’instant, Bruce. Demain nous rompons une malédiction ! J’espère !

Emma

Texte original de Cassandra Clare ©

Traduction d’Eurydice Bluenight ©

Le texte original est à lire ici : https://secretsofblackthornhall.tumblr.com/post/691398026631217153/emma-to-bruce

#kit herondale#emma carstairs#julian blackthorn#jem carstairs#tessa gray#jem and tessa#bruce#fairies#petit peuple#secrets of blackthorn hall#cassandra clare#sobh#the shadowhuter chronicles#tsc

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Le 6 juin 1944

Débarquement en Normandie, mais pas que cela ! Par Bernard Bruyneel Vous pouvez soutenir notre travail en vous abonnant mensuellement pour 2 € par mois via STRIPE totalement sécuriséEn cadeau, un livre PDF vous sera envoyé par mail Attention ce texte est un pamphlet n’engageant que son auteur. Observatoire du MENSONGE défend la liberté d’expression ! Faîtes de même en le partageant et/ou en…

View On WordPress

#Bernard Bruyneel#despote#Observatoire du MENSONGE#petit peuple#politique#profiteuses#sans-coucougnette#sans-culotte#télécommande

0 notes

Text

Ils arrivent, ils sont là ! Les Kobolds !

Découvrez les mystères des kobolds, ces esprits folkloriques germaniques liés à l'élément cobalt. Plongez dans leur monde à travers des illustrations captivantes ! #ArtEtScience #Kobolds #Cobalt

View On WordPress

#art#artist#fantaisie#fantastique#illustrateur#illustrations#kobold#painting#petit peuple#watercolor

0 notes

Text

youtube

petite histoire poétique de la France, résister

Avant les tristes années de l'Armée des ombres, il n'y a eu aucune reconnaissance pour leur soutien, leur possible réconfort. Un début de justice pour ces figures de l'absence matérialisée ?

L'ombre, la grande victime de ces siècles derniers, de nos civilisations ignorantes !

Le peuple des Ombres est celui qui résiste.

.

(Dans la portée des ombres, extrait)

© Pierre Cressant

(vendredi 21 octobre 2005)

#poème#poésie#poésie en prose#prose poétique#poètes sur tumblr#french poetry#poésie contemporaine#poème en prose#dans la portée des ombres#l'armée des ombres#jean-pierre melville#petite histoire poétique du cinéma#peuple des ombres#résistance#seconde guerre mondiale#Eric Demarsan#petite histoire poétique de la france#Youtube

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Elle pourrait commencer par la boucler par exemple

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Il y a

(Note: * means it is a negative sentence: il n'y a)

Anguille sous roche - there's something fishy going on

Belle lurette - it's been a while

Bien longtemps (que) - it's been a while (since)

Comme un goût de - it almost tastes like

De ça - you are right but there is more to it (casual)

De ça (+ duration), - it was (X time) ago that

De la friture sur la ligne - there's static on the line

De l'ambiance - there's a great atmosphere

De l'eau dans le gaz - there's trouble brewing

De l'idée - that's not a bad idea (although it's incomplete)

De l'orage dans l'air - there's trouble brewing

De quoi - it is justified (casual)

De quoi être fier - /one/ can be proud about that

De quoi faire - there are enough supplies for the project

*De roses sans épines - there are no roses without thorns

Des baffes/claques qui se perdent - /one/ deserves a slap

Des coups de pied au cul qui se perdent - /one/ deserves a kick in the butt

Des hauts et des bas - there are ups and downs

Des limites - there are limits (not to cross)

Des moments où - there are times when

Des nuages - it's cloudy

Du brouillard - it's foggy

Du boulot - we have a lot of work to do

Du monde/peuple - it is really crowded

Du monde au balcon - /one/ has big breasts

Du soleil - it's sunny

Du vent - it's windy

Du vrai (dans ce que tu dis) - /one/ is not wrong

Erreur (sur la personne) - /one/ is mistaken

Fort/gros à parier que - it is a safe bet that

Intérêt à (+ infinitive or que + verb) - there better (be): il y a intérêt que tu te calmes, il y a intérêt à se taire

Largement de quoi faire - there are enough supplies for the project

Le feu - fire!

Longtemps que - it's been a long time since

Méprise - there is a mistake

Moyen de moyenner - we can make that work (casual)

*Pas à dire - you have to admit

*Pas à tortiller - there's no getting away from it (casual)

*Pas de fumée sans feu - there's no smoke without fire

*Pas de mais (qui tienne) - no arguing with me

*Pas de mal - no worries, you meant no harm

*Pas de mal à se faire du bien - a little of what you fancy does you good

*Pas de petits profits - look after the pennies and the pounds will look after themselves

*Pas de quoi - you're welcome (casual)

*Pas de quoi s'énerver - no need to get annoyed

*Pas de sot métier - all job is noble

*Pas de temps à perdre - there is no time to lose

*Pas le feu au lac - we are not in a rush (casual)

*Pas longtemps que - it hasn't been long since

*Pas mort d'homme - calm down (casual)

*Pas photo - clearly (casual)

*Pas un chat/rat - there is no one around

Peu de temps que - it hasn't been long since

Prescription - it's time to move on

*Plus de saisons - seasons don't mean anything anymore

*Que ça de vrai - this is what really matters

*Que la vérité qui blesse/fâche - you're angry because you know it's right

Quelque chose qui cloche (chez) - something is wrong (with)

Quelque chose qui m'échappe - I don't understand something

Quelques années - a few years ago

*Qu'un pas - /something/ is only one step away

*Rien à faire - there's nothing to do (bored or stuck)

*Rien de nouveau sous le soleil - there is nothing new

Un avant et un après - there is a before and an after

Un coup à jouer - /one/ has an opportunity here

Une éternité que - it's been an eternity since

Un temps pour tout - timing is everything

Il y en

A marre - /one/ has had enough, this is too much

*A pas un pour rattraper l'autre - you two are as bad as each other

+

Il y a X + X - there is a spectrum to it (unhappy): "Pierre said he stole the neighbours' cat as a joke!" "il y a blague et blague!"

Qu'est-ce qu'il y a ? - what's up ? what's wrong ?

S'il y a lieu - if applicable, needed

Tant qu'il y a de la vie, il y a de l'espoir - where there's life, there's hope

144 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Women of the French Revolution (and even the Napoleonic Era) and Their Absence of Activism or Involvement in Films

Warning: I am currently dealing with a significant personal issue that I’ve already discussed in this post: https://www.tumblr.com/nesiacha/765252498913165313/the-scars-of-a-toxic-past-are-starting-to-surface?source=share. I need to refocus on myself, get some rest, and think about what I need to do. I won’t be around on Tumblr or social media for a few days (at most, it could last a week or two, though I don’t really think it will).

But don’t worry about me—I’m not leaving Tumblr anytime soon. I just wanted to let you know so you don’t worry if you don’t see me and have seen this post.

I just wanted to finish this post, which I’d already started three-quarters of the way through.

One aspect that frustrates me in film portrayals (a significant majority, around 95%) is the way women of the Revolution or even the Napoleonic era are depicted. Generally, they are shown as either "too gentle" (if you know what I mean), merely supporting their husbands or partners in a purely romantic way. Just look at Lucile Desmoulins—she is depicted as a devoted lover in most films but passive and with little to say about politics.

Yet there’s so much to discuss regarding women during this revolutionary period. Why don’t we see mention of women's clubs in films? There were over 50 in France between 1789 and 1793. Why not mention Etta Palm d’Alders, one of the founders of the Société Patriotique et de Bienfaisance des Amies de la Vérité, who fought for the right to divorce and for girls' education? Or the cahier from the women of Les Halles, requesting that wine not be taxed in Paris?

Only once have I seen Louise Reine Audu mentioned in a film (the excellent Un peuple et son Roi), a Parisian market woman who played a leading role in the Revolution. She led the "dames des halles" and on October 5, 1789, led a procession from Paris to Versailles in this famous historical event. She was imprisoned in September 1790, amnestied a year later through the intervention of Paris mayor Pétion, and later participated in the storming of the Tuileries on August 10, 1792. Théroigne de Méricourt appears occasionally as a feminist, but her mission is often distorted. She was not a Girondin, as some claim, but a proponent of reconciliation between the Montagnards and the Girondins, believing women had a key role in this process (though she did align with Brissot on the war question). She was a hands-on revolutionary, supporting the founding of societies with Charles Gilbert-Romme and demanding the right to bear arms in her Amazon attire.

Why is there no mention in films of Pauline Léon and Claire Lacombe, two well-known women of the era? Pauline Léon was more than just a fervent supporter of Théophile Leclerc, a prominent ultra-revolutionary of the "Enragés." She was the eldest daughter of chocolatier parents, her father a philosopher whom she described as very brilliant. She was highly active in popular societies. Her mother and a neighbor joined her in protesting the king’s flight and at the Champ-de-Mars protest in July 1791, where she reportedly defended a friend against a National Guard soldier. Along with other women (and 300 signatures, including her mother’s), she petitioned for women’s rights. She participated in the August 10 uprising, attacked Dumouriez in a session of the Société fraternelle des patriotes des deux sexes, demanded the King’s execution, and called for nobles to be banned from the army at the Jacobin Club, in the name of revolutionary women. She joined her husband Leclerc in Aisne where he was stationed (see @anotherhumaninthisworld’s excellent post on Pauline Léon). Claire Lacombe was just as prominent at the time and shared her political views. She was one of those women, like Théroigne de Méricourt, who advocated taking up arms to fight the tyrant. She participated in the storming of the Tuileries in 1792 and received a civic crown, like Louise Reine Audu and Théroigne de Méricourt. She was active at the Jacobin Club before becoming secretary, then president of the Société des Citoyennes Républicaines Révolutionnaires (Society of Revolutionary Republican Women). Contrary to popular belief, there’s no evidence she co-founded this society (confirmed by historian Godineau). Lacombe demanded the trial of Marie Antoinette, stricter measures against suspects, prosecution of Girondins by the Revolutionary Tribunal, and the application of the Constitution. She also advocated for greater social rights, as expressed in the Enragés petition, which would later be adopted by the Exagérés, who were less suspicious of delegated power and saw a role beyond the revolutionary sections.

Olympe de Gouges did not call for women to bear arms; in her Declaration of the Rights of Woman and the Female Citizen, addressed to the Queen after the royal family’s attempted escape, she demanded gender equality. She famously said, "A woman has the right to mount the scaffold; she must equally have the right to mount the rostrum," and denounced the monarchy when Louis XVI's betrayal became undeniable, although she sought clemency for him and remained a royalist. She could be both a patriot and a moderate (in the conservative sense; moderation then didn’t necessarily imply clemency but rather conservative views on certain matters).

Why Are Figures Like Manon Roland Hardly Mentioned in These Films?

In most films, Manon Roland is barely mentioned, or perhaps given a brief appearance, despite being a staunch republican from the start who worked toward the fall of the King and was more than just a supporter of her husband, Roland. She hosted a salon where political ideas were exchanged and was among those who contributed to the monarchy's downfall. Of course, she was one of those courageous women who, while brave, did not advocate for women’s rights. It’s essential to note that just because some women fought in the Revolution or displayed remarkable courage doesn’t mean they necessarily advocated for greater rights for women (even Olympe de Gouges, as I mentioned earlier, had her limits on gender equality, as she did not demand the right for women to bear arms).

Speaking of feminism, films could also spotlight Sophie de Grouchy, the wife and influence behind Condorcet, one of the few deputies (along with Charles Gilbert-Romme, Guyomar, Charlier, and others) who openly supported political and civic rights for women. Without her, many of Condorcet’s posthumous works wouldn’t have seen the light of day; she even encouraged him to write Esquilles and received several pages to publish, which she did. Like many women, she hosted a salon for political discussion, making her a true political thinker.

Then there’s Rosalie Jullien, a highly cultured woman and wife of Marc-Antoine Jullien, whose sons were fervent revolutionaries. She played an essential role during the Revolution, actively involving herself in public affairs, attending National Assembly sessions, staying informed of political debates and intrigues, and even sending her maid Marion to gather information on the streets. Rosalie’s courage is evident in her steadfastness, as she claimed she would "stay at her post" despite the upheaval, loyal to her patriotic and revolutionary ideals. Her letters offer invaluable insights into the Revolution. She often discussed public affairs with prominent revolutionaries like the Robespierre siblings and influential figures like Barère.

Lucile Desmoulins is another figure. She was not just the devoted lover often depicted in films; she was a fervent supporter of the French Revolution. From a young age, her journal reveals her anti-monarchist sentiments (no wonder she and Camille Desmoulins, who shared her ideals, were such a united couple). She favored the King’s execution without delay and wholeheartedly supported Camille in his publication, Le Vieux Cordelier. When Guillaume Brune urged Camille to tone down his criticism of the Year II government, Lucile famously responded, “Let him be, Brune. He must save his country; let him fulfill his mission.” She also corresponded with Fréron on the political situation, proving herself an indispensable ally to Camille. Lucile left a journal, providing historical evidence that counters the infantilization of revolutionary women. Sadly, we lack personal journals from figures like Éléonore Duplay, Sophie Momoro, or Claire Lacombe, which has allowed detractors to argue (incorrectly) that these women were entirely under others' influence.

Additionally, there were women who supported Marat, like his sister Albertine Marat and his "wife"Simone Evrard, without whom he might not have been as effective. They were politically active throughout their lives, regularly attending political clubs and sharing their political views. Simone Evrard, who inspired much admiration, was deeply committed to Marat’s work. Marat had promised her marriage, and she was warmly received by his family. She cared for Marat, hiding him in the cellar to protect him from La Fayette’s soldiers. At age 28, Simone played a vital role in Marat’s life, both as a partner and a moral supporter. At this time, Marat, who was 20 years her senior, faced increasing political isolation; his radical views and staunch opposition to the newly established constitutional monarchy had distanced him from many revolutionaries.

Despite the circumstances, Simone actively supported Marat, managing his publications. With an inheritance from her late half-sister Philiberte, Simone financed Marat’s newspaper in 1792, setting up a press in the Cordeliers cloister to ensure the continued publication of Marat’s revolutionary pamphlets. Although Marat also sought public funds, such as from minister Jean-Marie Roland, it was mainly Simone’s resources that sustained L’Ami du Peuple. Simone and Marat also planned to publish political works, including Chains of Slavery and a collection of Marat’s writings. After Marat’s assassination in July 1793, Simone continued these projects, becoming the guardian of his political legacy. Thanks to her support, Marat maintained his influence, continuing his revolutionary struggle and exposing the “political machination” he opposed.

Simone’s home on Rue des Cordeliers also served as an annex for Marat’s printing press. This setup combined their personal life with professional activities, incorporating security measures to protect Marat. Simone, her sister Catherine, and their doorkeeper, Marie-Barbe Aubain, collaborated in these efforts, overseeing the workspace and its protection.

On July 13, 1793, Jean-Paul Marat was assassinated by Charlotte Corday. Simone Evrard was present and immediately attempted to help Marat and make sure that Charlotte Corday was arrested . She provided precise details about the circumstances of the assassination, contributing significantly to the judicial file that would lead to Corday’s condemnation.

After Marat’s death, Simone was widely recognized as his companion by various revolutionaries and orators who praised her dignity, and she was introduced to the National Convention by Robespierre on August 8, 1793 when she make a speech against Theophile Leclerc,Jacques Roux, Carra, Ducos,Dulaure, Pétion... Together with Albertine Marat (who also left written speeches from this period), Simone took on the work of preserving and publishing Marat’s political writings. Her commitment to this cause led to new arrests after Robespierre's fall, exposing the continued hostility of factions opposed to Marat’s supporters, even after his death.

Moreover, Jean-Paul Marat benefited from the support of several women of the Revolution, and he would not have been as effective without them.

The Duplay sisters were much more politically active than films usually portray. Most films misleadingly present them as mere groupies (considering that their father is often incorrectly shown as a simple “yes-man” in these same, often misogynistic, films, it's no surprise the treatment of women is worse).

Élisabeth Le Bas, accompanied her husband Philippe Le Bas on a mission to Alsace, attended political sessions, and bravely resisted prison guards who urged her to marry Thermidorians, expressing her anger with great resolve. She kept her husband’s name, preserving the revolutionary legacy through her testimonies and memoirs. Similarly, Éléonore Duplay, Robespierre’s possible fiancée, voluntarily confined herself to care for her sister, suffered an arrest warrant, and endured multiple prison transfers. Despite this, they remained politically active, staying close to figures in the Babouvist movement, including Buonarroti, with whom Éléonore appeared especially close, based on references in his letters.

Henriette Le Bas, Philippe Le Bas's sister, also deserves more recognition. She remained loyal to Élisabeth and her family through difficult times, even accompanying Philippe, Saint-Just, and Élisabeth on a mission to Alsace. She was briefly engaged to Saint-Just before the engagement was quickly broken off, later marrying Claude Cattan. Together with Éléonore, she preserved Élisabeth’s belongings after her arrest. Despite her family’s misfortunes—including the detention of her father—Henriette herself was surprisingly not arrested. Could this be another coincidence when it came to the wives and sisters of revolutionaries, or perhaps I missed part of her story?

Charlotte Robespierre, too, merits more focus. She held her own political convictions, sometimes clashing with those of her brothers (perhaps often, considering her political circle was at odds with their stances). She lived independently, never marrying, and even accompanied her brother Augustin on a mission for the Convention. Tragically, she was never able to reconcile with her brothers during their lifetimes. For a long time, I believed that Charlotte’s actions—renouncing her brothers to the Thermidorians after her arrest, trying to leverage contacts to escape her predicament, accepting a pension from Bonaparte, and later a stipend under Louis XVIII—were all a matter of survival, given how difficult life was for a single woman then. I saw no shame in that (and I still don’t). The only aspect I faulted her for was embellishing reality in her memoirs, which contain some disputable claims. But I recently came across a post by @saintejustitude on Charlotte Robespierre, and honestly, it’s one of the best (and most well-informed) portrayals of her.

As for the the hébertists womens , films could cover Sophie Momoro more thoroughly, as she played the role of the Goddess of Reason in her husband’s de-Christianization campaigns, managed his workshop and printing presses in his absence accompanying Momoro on a mission on Vendée. Momoro expressed his wife's political opinion on the situation in a letter. She also drafted an appeal for assistance to the Convention in her husband’s characteristic style.

Marie Françoise Goupil, Hébert’s wife, is likewise only shown as a victim (which, of course, she was—a victim of a sham trial and an unjust execution, like Lucile Desmoulins). However, there was more to her story. Here’s an excerpt from a letter she wrote to her husband’s sister in the summer of 1792 that reveals her strong political convictions:

« You are very worried about the dangers of the fatherland. They are imminent, we cannot hide them: we are betrayed by the court, by the leaders of the armies, by a large part of the members of the assembly; many people despair; but I am far from doing so, the people are the only ones who made the revolution. It alone will support her because it alone is worthy of it. There are still incorruptible members in the assembly, who will not fear to tell it that its salvation is in their hands, then the people, so great, will still be so in their just revenge, the longer they delay in striking the more it learns to know its enemies and their number, the more, according to me, its blows will only strike with certainty and only fall on the guilty, do not be worried about the fate of my worthy husband. He and I would be sorry if the people were enslaved to survive the liberty of their fatherland, I would be inconsolable if the child I am carrying only saw the light of day with the eyes of a slave, then I would prefer to see it perish with me ».

There is also Marie Angélique Lequesne, who played a notable role while married to Ronsin (and would go on to have an important role during the Napoleonic era, which we’ll revisit later). Here’s an excerpt from Memoirs, 1760-1820 by Jean-Balthazar de Bonardi du Ménil (to be approached with caution): “Marie-Angélique Lequesne was caught up in the measures taken against the Hébertists and imprisoned on the 1st of Germinal at the Maison d'Arrêt des Anglaises, frequently engaging with ultra-revolutionary circles both before and after Ronsin’s death, even dressing as an Amazon to congratulate the Directory on a victory.” According to Généanet (to be taken with even more caution), she may have served as a canteen worker during the campaign of 1792.

On the Babouvist side, we can mention Marie Anne Babeuf, one of Gracchus Babeuf’s closest collaborators. Marie Anne was among her husband's staunchest political supporters. She printed his newspaper for a long time, and her activism led to her two-day arrest in February 1795. When her husband was arrested while she was pregnant, she made every effort possible to secure his release and never gave up on him. She walked from Paris to Vendôme to attend his trial, witnessing the proceeding that would sentence him to death. A few months after Gracchus Babeuf’s execution, she gave birth to their last son, Caius. Félix Lepeletier became a protector of the family (and apparently, Turreau also helped, supposedly adopting Camille Babeuf—one of his very few positive acts). Marie Anne supported her children through various small jobs, including as a market vendor, while never giving up her activism and remaining as combative as ever. (There’s more to her story during the Napoleonic era as well).

We must not forget the role of active women in the insurrections of Year III, against the Assembly, which had taken a more conservative turn by then. Here’s historian Mathilde Larrère’s description of their actions: “In April and May 1795, it was these women who took to the streets, beating drums across the city, mocking law enforcement, entering shops, cafes, and homes to call for revolt. In retaliation, the Assembly decreed that women were no longer allowed to attend Assembly sessions and expelled the knitters by force. Days later, a decree banned them from attending any assemblies and from gathering in groups of more than five in the streets.”

There were also women who fought as soldiers during the French Revolution, such as Marie-Thérèse Figueur, known as “Madame Sans-Gêne.” The Fernig sisters, aged 22 and 17, threw themselves into battle against Austrian soldiers, earning a reputation for their combat prowess and later becoming aides-de-camp to Dumouriez. Other fighting women included the gunners Pélagie Dulière and Catherine Pochetat.

In the overseas departments, there was Flore Bois Gaillard, a former slave who became a leader of the “Brigands” revolt on the island of Saint Lucia during the French Revolution. This group, composed of former slaves, French revolutionaries, soldiers, and English deserters, was determined to fight against English regiments using guerrilla tactics. The group won a notable victory, the Battle of Rabot in 1795, with the assistance of Governor Victor Hugues and, according to some accounts, with support from Louis Delgrès and Pelage.

On the island of Saint-Domingue, which would later become Haiti, Cécile Fatiman became one of the notable figures at the start of the Haitian Revolution, especially during the Bois-Caiman revolt on August 14, 1791.

In short, the list of influential women is long. We could also talk about figures like Félicité Brissot, Sylvie Audouin (from the Hébertist side), Marguerite David (from the Enragés side), and more. Figures like Theresia Cabarrus, who wielded influence during the Directory (especially when Tallien was still in power), or the activities of Germaine de Staël (since it’s essential to mention all influential women of the Revolution, regardless of political alignment) are also noteworthy.

Napoleonic Era

Films could have focused more on women during this era. Instead, we always see the Bonaparte sisters (with Caroline cast as an exaggerated villain, almost like a cartoon character), or Hortense Beauharnais, who’s shown solely as a victim of Louis Bonaparte and portrayed as naïve. There is so much more to say about this time, even if it was more oppressive for women.

Germaine de Staël is barely mentioned, which is unfortunate, and Marie Anne Babeuf is even more overlooked, despite her being questioned by the Napoleonic police in 1801 and raided in 1808. She also suffered the loss of two more children: Camille Babeuf, who died by suicide in 1814, and Caius, reportedly killed by a stray bullet during the 1814 invasion of Vendôme. No mention is made of Simone Evrard and Albertine Marat, who were arrested and interrogated in 1801.

An important but lesser-known event in popular culture was the deportation and imprisonment of the Jacobins, as highlighted by Lenôtre. Here’s an excerpt: “This petition reached Paris in autumn 1804 and was filed away in the ministry's records. It didn’t reach the public, who had other amusements besides the old stories of the Nivôse deportees. It was, after all, the time when the Republic, now an Empire, was preparing to receive the Pope from Rome to crown the triumphant Caesar. Yet there were people in Paris who thought constantly about the Mahé exiles—their wives, most left without support, living in extreme poverty; mothers were the hardest hit. Even if one doesn’t sympathize with the exiles themselves, one can feel pity for these unfortunate women... They implored people in their neighborhoods and local suppliers to testify on behalf of their husbands, who were wise, upstanding, good fathers, and good spouses. In most cases, these requests came too late... After an agonizing wait, the only response they received was, ‘Nothing to be done; he is gone.’” (Les Derniers Terroristes by Gérard Lenôtre). Many women were mobilized to help the Jacobins. One police report references a woman named Madame Dufour, “wife of the deportee Dufour, residing on Rue Papillon, known for her bold statements; she’s a veritable fury, constantly visiting friends and associates, loudly proclaiming the Jacobins’ imminent success. This woman once played a role in the Babeuf conspiracy; most of their meetings were held at her home…” (Unfortunately for her, her husband had already passed away.)

On the Napoleonic “allies” side, Marie Angélique, the widow of Ronsin who later married Turreau, should be more highlighted. Turreau treated her so poorly that it even outraged Washington’s political class. She was described as intelligent, modest, generous, and curious, and according to future First Lady Dolley Madison, she charmed Washington’s political circles. She played an essential role in Dolley Madison’s political formation, contributing to her reputation as an active, politically involved First Lady. Marie Angélique eventually divorced Turreau, though he refused to fund her return to France; American friends apparently helped her.

Films could also portray Marie-Jacqueline Sophie Dupont, wife of Lazare Carnot, a devoted and loving partner who even composed music for his poems. Additionally, her ties with Joséphine de Beauharnais could be explored. They were close friends, which is evident in a heartbreaking letter Lazare Carnot wrote to Joséphine on February 6, 1813, to inform her of Sophie’s death: “Until her last moment, she held onto the gratitude Your Majesty had honored her with; in her memory, I must remind Your Majesty of the care and kindness that characterize you and are so dear to every sensitive soul.”

In films, however, when Joséphine de Beauharnais’s circle is shown, Theresia Cabarrus (who appears much more in Joséphine ou la comédie des ambitions) and the Countess of Rémusat are mentioned, but Sophie Carnot is omitted, which is a pity. Sophie Carnot knew how to uphold social etiquette well, making her an ideal figure to be integrated into such stories (after all, she was the daughter of a former royal secretary).

Among women soldiers, we had Marie-Thérèse Figueur as well as figures like Maria Schellink, who also deserves greater representation. Speaking of fighters, films could further explore the stories of women who took up arms against the illegal reinstatement of slavery. In Saint-Domingue, now Haiti, many women gave their lives, including Sanité Bélair, lieutenant of Toussaint Louverture, considered the soul of the conspiracy along with her husband, Charles Bélair (Toussaint’s nephew) and a fighter against Leclerc. Captured, sentenced to death, and executed with her husband, she showed great courage at her execution. Thomas Madiou's Histoire d’Haiti describes the final moments of the Bélair couple: ��When Charles Bélair was placed in front of the squad to be shot, he calmly listened to his wife exhorting him to die bravely... (...)Sanité refused to have her eyes covered and resisted the executioner’s efforts to make her bend down. The officer in charge of the squad had to order her to be shot standing.”

Dessalines, known for leading Haiti to victory against Bonaparte, had at least three influential women in his life. He had as his mentor, role modele and fighting instructor the former slave Victoria Montou, known as Aunt Toya, whom he considered a second mother. They met while they were working as slaves. They met while both were enslaved. The second was his future wife, Marie Claire Bonheur, a sort of war nurse, as described in this post, who proved instrumental in the siege of Jacmel by persuading Dessalines to open the roads so that aid, like food and medicine, could reach the city. When independence was declared, Dessalines became emperor, and Marie Claire Bonheur, empress. When Jean-Jacques Dessalines ordered the elimination of white inhabitants in Haiti, Marie Claire Bonheur opposed him, some say even kneeling before him to save the French. Alongside others, she saved those later called the “orphans of Cap,” two girls named Hortense and Augustine Javier.

Dessalines had a legitimized illegitimate daughter, Catherine Flon, who, according to legend, sewed the country’s flag on May 18, 1803. Thus, three essential women in his life contributed greatly to his cause.

In Guadeloupe, Rosalie, also known as Solitude, fought while pregnant against the re-establishment of slavery and sacrificed her life for it, as she was hanged after giving birth. Marthe Rose Toto also rose up and was hanged a few months after Louis Delgrès’s death (if they were truly a couple, it would have added a tragic touch to their story, like that of Camille and Lucile Desmoulins, which I have discussed here).

To conclude, my aim in this post is not to elevate these revolutionary, fighting, or Napoleonic-allied women above their male counterparts but simply to give them equal recognition, which, sadly, is still far from the case (though, fortunately, this is not true here on Tumblr).

I want to thank @aedesluminis for providing such valuable information about Sophie Carnot—without her, I wouldn't have known any of this. And I also want to thank all of you, as your various posts have been really helpful in guiding my research, especially @anotherhumaninthisworld, @frevandrest, @sieclesetcieux, @saintjustitude, @enlitment ,@pleasecallmealsip ,@usergreenpixel , @orpheusmori ,@lamarseillasie etc. I apologize if I forgot anyone—I’m sure I have, and I'm sorry; I'm a bit exhausted. ^^

#frev#french revolution#napoleon#napoleonic era#women in history#haitian revolution#slavery#guadeloupe#frustration

132 notes

·

View notes

Text

Le peuple a parlé. @fangard , @tealviscaria , c'est pour vous : voici donc notre bon vieux Raph, en tant que Quatre de Coupes ! Il était temps qu'il figure dans le bousin, vous me direz...

(J'ai pas résisté, il fallait un Renard en plus. Mais ! Je vous jure, c'est justifié. Si vous voulez savoir pourquoi, lisez sous la coupure. Ouais je tease ouais. Ca s'appelle du marketing. Ca s'trouve y'aura même un sondage à la fin, ça serait foufou)

Vous avez tiré le Quatre de Coupes, donc ? A la bonne heure ! Ca veut dire que vous, oui, vous, sur votre banc, vous avez de nouvelles opportunités qui s'offrent à vous. Sauf que... bah, vous leur dites non, à ces opportunités. A votre défense, au début, c'est très justifié. C'est que ces opportunités vous privent de votre part de pizza, vous pousse à vous faire renverser par un bus, et viennent pourrir la tranquillité de votre petite vie pour zéro raisons. Et vous l'aimez, votre petite vie. Vous êtes un type casanier, vous, qui passe son temps devant ses jeux vidéos à ne jamais jamais voir la lumière du jour.

... Ah ouais ? Vous l'aimez, votre vie ? Eh bien, non. Votre vie quotidienne, répétitive, sans histoire, elle vous ennuie. Vous n'êtes pas satisfait, pas épanoui ; vous peinez à vous engager dans des choses qui vous passionnent, si elles existent seulement, et tendez à vous montrer apathique, dépourvu de motivation. Trouver un travail ? Travailler sous la direction de vos anciens potes ? Photocopieuse, café, maison ? Vous n'êtes pas heureux. Mais vous vous accrochez à cette vie ; vous vous accrochez à votre familiarité, à des relations qui ne sont pas ou plus faites pour vous, parce que la familiarité vous rassure. Tout le contraire des opportunités qui s'offrent à vous : elles ne font pas sens, présentent un chamboulement complet de vos repères, et quelque part, ça vous terrorise. Vous avez peur de faire confiance à ce type (en même temps, le type fait tout pour ne pas avoir l'air digne de confiance). Vous avez peur de perdre tout ce que vous avez. Mais vous devez accepter de sortir de votre coquille, de votre routine ; ne vous fermez pas à la possibilité d'une autre vie, qui, peut-être, vous permettra de mieux vous épanouir. Parfois, on se sent plus soi-même dans un abri souterrain futuriste, en colloc' avec un robot et un clochard qui vous traite comme leur gosse adoptif, que dans son appart' parisien en 2010 à faire la queue au Pôle Emploi. La preuve : maintenant, vous êtes capable de mettre des canettes dans des poubelles et d'aligner deux mots cohérents en parlant à une femme. Après, bon, faut pas vous demander d'en aligner trois.

Si vous hésitez encore, interrogez vous sur vous même. Qu'est-ce qui vous anime ? Qui êtes vous, quelles sont vos motivations ? Faire une différence, peut-être. Aider. Sauver le monde, même, qui sait. Si vous identifiez votre objectif, alors, vous saurez si l'opportunité s'aligne avec ; si c'est le cas, prenez votre courage à deux mains, et allez y ! Vous avez peur d'un changement que vous imaginerez drastique : mais vous n'aurez pas besoin de vous changer, vous. Vous pourrez vous affirmer, grandir, devenir la meilleure personne que vous puissiez être, sans pour autant perdre ce qui fait que vous êtes Raph. Il faut juste faire le bon choix !

Et voilà pourquoi Renard est sur la carte ! C'est lui qui présente la quatrième coupe à Raph ; différente de celles qu'il tient déjà, auxquelles il s'attache, mais lumineuse. Un avenir radieux, n'est-ce pas, comme symbolisé par l'arrière plan- sauf que, pour l'instant, Raph, contrairement au goupil, refuse de tourner la tête vers le soleil, et garde les yeux portés sur le passé. Ca changera, bien sûr. Comme on le sait tous.

Voilà qui conclut donc la sixième carte de tarot sur le thème du Visiteur du Futur !

Mais qui sera la prochaine ? J'ai reçu deux propositions. Dès lors...

#le visiteur du futur fanart#le visiteur du futur#tarot project#vdf#vdf fanart#four of cups#vdf raph#raphael descraques#vdf renard#le visiteur du futur renard#bah concrètement c'est vrai#y'a clairement un renard sur ce dessin n'est-il point

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

Science et vérité: de la différence entre connaissance et savoir

Il n’y a de savoir que de lalangue.

Le psychanalyste établit une différence notable entre: “connaissance” (S2) et “savoir” (S1—>S2)

«Le savoir ne s’acquiert pas par le travail, et moins encore la formation qui du savoir est l’effet.

Ce qui n’est nullement dénier le savoir du travailleur, voire si l’on veut, du peuple, mais affirmer que pas plus que les savants, il ne l’acquiert par son travail.

Galilée, ni Newton, ni Mendel, ni Gallois, ni le mignon petit James D. Watson ne doivent rien à leur travail, mais à celui des autres, et leurs trouvailles se transmettent en un éclair à qui a seulement la formation qui s'est produite de court-circuits du même ordre, et numérisables, même si l’ennui scolaire en a éteint la mémoire.

N’importe quelle mère de famille sait que la lecture est un obstacle à son travail, le premier manœuvre venu que c’en est l’échappatoire, l’ouvrier communiste, qu’il y prend ses lettres de noblesse.» (Lacan)

La différence entre le savoir et l’acquisition de connaissances, qui, elle, procède de l’apprentissage, est probablement ce qui fait que dans la psychanalyse, on enseigne ; on continue d'enseigner tout en sachant que c'est intransmissible.

Cela ne veut pas dire que l’on enseigne quoi que ce soit. Autrement dit que l’enseignement soit une transmission de savoir.

Il se pourrait même que l’enseignement soit l'obstacle principal à la conquête du savoir.

Il n’y a de savoir que savoir de lalangue, écrit comme ça, en un mot, car tout savoir véritable est marqué du sceau de la jouissance, et il ne saurait y avoir de savoir que joui.

Loin de se situer en opposition à la pratique , la théorie - ce qui s'appelle à proprement parler “théorie”, du Grec theoria qui veut dire vision - est ce qui naît de la pratique pour en éclairer les modalités concrètes.

Le plus important, dans l'enseignement, c'est ce qui se passe, la valeur du savoir tient de l'usage que l'enseignant en fait - et donc sa façon singulière d'en jouir, plutôt que de son “échange”…

Lacan est très sévère avec le discours universitaire qui se trouve dans un rapport radical d’antipathie avec le discours de l’analyste. L'acquisition de connaissances du discours universitaire est à mettre au compte de la passion de l'ignorance, le savoir concerne autre chose, ce bout de Réel dont, en tant que sujet, je EST affligé, et que seul le discours de l’analyste, qui est de structure mœbienne, permet d’amener au jour.

«Le statut du savoir implique comme tel qu’il y en a déjà du savoir, et dans l’Autre, qu’il est à prendre en deux mots, c’est pourquoi il est fait d’apprendre en un seul mot. Le sujet résulte de ce qu’il doive être appris, ce savoir, etmême mis a-prix, p.r.i.x., c’est-à-dire que c’est son coût qui l’évalue non pas comme d’échange mais comme d’usage. Le savoir vaut juste autant qu’il coûte beaucoup en deux mots et c.o.û.t. avec un accent, beau-coût de ce qu’il faille y mettre de sa peau, de ce qu’il soit difficile, difficile dequoi ? Eh bien moins de l’acquérir que d’en jouir. Là dans le jouir, sa conquête à ce savoir, sa conquête se renouvelle dans le chaque fois que ce savoir est exercé, le pouvoir qu’il donne restant toujours tourné vers sa jouissance. Il est étrange que ceci n’ait jamais été mis en relief, que le sens de savoir soit tout entier là, que la difficulté de son exercice lui-même, c’est cela qui réhausse celle de son acquisition.» (Encore – 20 mars 1973)

Lorsque Gérard de Nerval dit: «Le premier qui a comparé la femme à une fleur était un poète, le deuxième un imbécile», il pointe le statut de la vérité qui fait structure de tout discours.

La vérité n’est pas à confondre avec l’exactitude ni le vrai.

Un énoncé peut être parfaitement exact — une formule de Lacan par exemple ! — cela ne signifie pas que le locuteur dit la vérité.

Il n’y a pas plus contradictoire à l’enseignement de Lacan que d’ânonner ses énoncés sans y mettre tout le poids de sa propre énonciation.

Il n’y a pas pire trahison de l’enseignement de Lacan que de rabattre ses énoncés sur la structure du Discours Universitaire, qu’il taxait lui-même de Discours du Maître perverti, celui de «la honte» que les soi-disant psychanalystes ont «à revendre»…

La vérité n’a pas de contraire, elle ne prend pas son statut de l’exactitude de tel ou tel énoncé mais des conséquences réelles à venir pour le sujet qui l’énonce.

Sans un risque réel pris par le sujet de l’énonciation — celui qui importe vraiment — l’énoncé peut être vrai, il n’en est pas moins exempt de vérité.

Le seul savoir auquel j’aie accès, c’est la fente dont se définit le sujet, le réel dont je “est” affligé.

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

Quand les Sans-culotte se font trimbaler par des profiteuses Sans-coucougnette !

Remplacement, un leurre ou une fatalité consentie ?

Pauvre gentil petit peuple figé devant la lucarne qui les télécommande à distance, les désinforme, manipule pour servir un despote qui se voudrait théocrate… Par Bernard Bruyneel Vous pouvez soutenir notre travail en vous abonnant mensuellement pour 2 € par mois via STRIPE totalement sécuriséEn cadeau, un livre PDF vous sera envoyé par mail Attention ce texte est un pamphlet n’engageant que…

View On WordPress

#Bernard Bruyneel#despote#Observatoire du MENSONGE#petit peuple#politique#profiteuses#sans-coucougnette#sans-culotte#télécommande

0 notes

Text

“Sympa mais un peu long”, vous diront les européistes impatients d'arriver les premiers au néant. Peut-être, oui. Mais c'est l'âme millénaire des peuples qui danse ici, qui communie, qui s'entend et se comprend. La Grèce, à sa façon, a montré l'exemple d'une forme de résistance – et non de "résilience" (abandonnons ce vocable très libéral aux marketeurs de Bruxelles et d'ailleurs). Un temps elle a cru à l'argent facile, aux promesses fallacieuses... ça l'arrangeait bien, alors. Puis la faillite, la ruine, la troïka, la crise. Et un peu de soleil à nouveau, au delà des nuages qui assombrirent le sourire du Pirée. Les Grecs écoutent les notes jaillies en cascade du bouzouki et les voilà qui se souviennent et dansent. Comme leurs parents, leurs aïeuls, leurs ancêtres. C'est la vie qui revient, et avec elle l'âme des peuples européens qui sourit à tous ces petits riens très ataviques, souvenirs de l'antique. Prenez-en de la graine, chers concitoyens ! J.-M. M.

67 notes

·

View notes

Text

NUOVA ROMA « he who controls the city, controls the myth. »

C'est de l'Ancien Observatoire - dont le squelette d'acier trempé et d'escaliers en colimaçon morcelés a triomphé des pluies acides et des vents battants désertiques - que l'on contemple le mieux l'obélisque monumental de Nuova Roma. Là, depuis les étendues arides où se dresse seul ce monument d'un autre temps, se dessine clairement la silhouette de la tour immense qui compose le coeur de la cité. Monument à la sublime ingénierie magique de la ville, on y distingue ses étages qui s'échelonnent autour de la colonne, plateformes mobiles en forme de demi cercles dont la lente rotation est à peine perceptible à l'oeil nu. Au plus près du sommet, le troisième et dernier étage s'élève comme un paradis artificiel réservé aux plus hautes têtes de la cité. Portées sur une vaste demie lune, dont l'ombre poursuit inéluctablement l'étage inférieur, s'imposent les plus belles bâtisses de la ville. Jardins luxuriants et fragrants, corinthiennes ouvragées qui supportent les dômes de ciels factices - d'orages, d'or ou d'étoiles, et piscines intérieures dont le cours serpente entre les pièces tel Jörmungand - dans ces demeures entre rêve et réalité reposent richesses et influence. Séparées par d'immenses domaines, les familles les plus aisées de la ville se sont ainsi isolées entre les nuages au creux de ces bulles artificielles, authentiques micro-climats runiques créés de toutes parts et modifiables à souhait. Pour les plus privilégiés d'entre eux, ce sont de véritables petites îles flottantes qui les abritent des regards curieux, gardées arrimées à l'obélisque par un coûteux assemblage de runes célestes. Pour tout voisin de ce luxe abondant, seul trône Il Consiglio et ses annexes administratives, arc de cercle de bureaux d'une blancheur immaculée qui borde la ligne intérieure de la plateforme. De son office, les fenêtres du cabinet de l'Oracle balaient l'horizon et laissent apercevoir, le soir, les silhouettes dansantes du Théâtre des Ombres qui prennent vie pour divertir les oisifs et se mêlent aux feux follets étranges qui illuminent la voie vers le Jardin de Circé. Havre de paix à la faune et la flore presque exclusivement magique, les nombreuses cascades de la ménagérie s'écoulent sans jamais éclabousser, débordent du plateau du troisième étage sans jamais offrir la fraîcheur de leurs eaux à ceux qui vivent en contrebas. Pas plus les oubliés à l'obscurité du deuxième étage que la foule bourgeoise et citadine du premier ne peuvent rêver à ces hauteurs - ce qui n'empêche pas les vendeurs de gloire du Colisée d'en titiller l'espoir auprès de ses combattants. Quant aux sous-sols, il vaut mieux ne pas savoir ce qui peuple les songes de ceux qui y dorment.

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

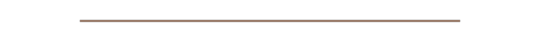

Our miniature hero has a frightening encounter in the deep sea with a Photostomias guernei.

From Le Peuple des Abysses (1980), a Petits Hommes story by Seron.

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

Robert Kime, la maison-monde

"Les trésors d'au-delà des mers afflueront vers toi"

Robert Kime exerçait le métier d'antiquaire. Son travail consistait à parcourir le monde à la recherche d'objets de mobilier artisanal rare pour revenir les installer dans l'écrin de la rigueur londonienne qui lui était familier. Monsieur Kime avait trouvé la sprezzatura du logement en le rendant chaleureux sans qu'il ait l'air professionnellement décoré. Son style est le plus abouti de la catégorie "foyer colonial", un genre qui évoque les vies romanesques antérieures au tourisme, où le doux foyer du voyageur ancien s'enrichissait de trouvailles durement acquises au fur et à mesure des retours de pays lointains. Chaque salle exprime ici en miniature quelque chose d'impérial, chaque élément décoratif est la strate d'une sédimentation patiente, chaque objet concourt à former un vaste cabinet de curiosités. Lorsqu'un coin de salon abrite plusieurs continents et plusieurs époques, le terme de musée vient à l'esprit. Plutôt que d'être statufié, le passé est ici habité. Installé dans une demeure il peuple l'arrière-plan de la vie quotidienne d'une famille, il accompagne un foyer tourné vers l'avenir, il est témoin du passage des jeunes de l'enfance à l'âge adulte, des allées et venues, des éclats de rire, des grands départs et des réconfortants retours. Les intérieurs Robert Kime ont une âme.

Le style d'habitat fixé par Robert Kime était courant chez la bourgeoisie du 20ème siècle. La peau de panthère au milieu des boiseries victoriennes, nous voyons cela dans Tintin, Blake & Mortimer, c'est une image d'Épinal. Ralph Lauren Home a puisé tardivement mais abondamment à cette source. Les appartements meublés dans ce goût éclectique étaient courants chez les diplomates, médecins coloniaux, antiquaires, marchands au long cours, collectionneurs, officiers de marine, anciens expatriés et autres catégories sociales baroques qui faisaient le charme des beaux-quartiers. La maison selon Kime est une maison coloniale placée en Europe pour qu'elle raconte le monde entier. Accomplissement des promesses messianiques, elle est la salle du trône où les richesses du monde ont afflué : tapis iraniens, carapaces de tortue des Maldives, vases chinois, instruments de musique indonésiens, estampes japonaises, table de changeur byzantin, bas-reliefs moghols, fragment d'ostrakon athénien. Jalonnées de mobilier occidental plus sobre, ces raretés rassemblées en un même lieu offrent un panorama de provenances et d'époques. Kime est l'assembleur d'une beauté composite comme les parties juxtaposées d'un vitrail, il est le découvreur de l'harmonie entre des tons, des volumes, des grammages que tout séparait.

Transportés en navire de fort tonnage à travers les tempêtes, débarqués par les dockers, les exigences du plaisir esthétique supposent une rude logistique. À Mayfair, Chelsea, Marylebone, à Jasmin, Trocadéro, Saint-Germain-des-Prés, l'honnête homme faisait de son foyer un résumé du monde où chaque mètre carré chantait la légende coloniale. "Saïgon", "Macassar" ou "Singapour", sont des mots teintés d'une telle force évocatrice que, prononcés pour qualifier la provenances des objets dans un appartement donnant sur un boulevard venteux, ils suffisaient à rappeler la position heureuse où la Providence avait placé votre petite nation capable d'en administrer d'autres situées à cinq semaines de bateau.

La maison de famille est elle aussi devenue universelle. Le monde est venu à elle, tandis que son génie local, occidental, s'est étendu au monde. La maisonnée en a rapporté les nectars les plus purs, chacun d'entre eux exprimant l'intégralité des sucs d'une cité étrangère, d'une histoire, d'un peuple. Toute cosmopolite qu'elle soit, la maison Robert Kime est une maison européenne d'abord, universelle ensuite.

Ne pas se fier aux apparences. Des richesses autrement précieuses que de menus chiffons gisent en ces demeures. Chaque motif de chaque étoffe provient de traditions anciennes, de savoirs-faire délaissés, de palais sauvés des orages d'acier du 20ème siècle. Le damas, le Jouy, l'arabesque, le point d'Alençon, ont chacun leur signification profonde. Le paisley par exemple ne figure-t-il pas la larme du Boudha dans une tradition antérieure de 800 ans à notre ère, et transmise par des générations d'artisans indo-aryens ? La maison Robert Kime c'est la petite Europe maintenue au sommet de sa forme, si haut qu'elle peut voir l'intégralité du monde, et le donner à voir.

Monsieur Kime a eu des goûts sûrs et des dégoûts encore plus sûrs, il était connu pour exprimer en public des opinions tranchées (il n'était donc pas un gentleman). En un temps de désastreux designers Monsieur Kime persistait disait-il, à "faire des intérieurs pour qu'ils soient habités, non pour qu'ils soient regardés". La dualité radicale de l'ergonomie et du design est ancienne or il existe une ergonomie de l'habitat qui la réconcilie c'est cet ameublement smart, terme jailli des fontaines de l'intuition qui se traduit chez nous par "intelligent", mais encore par "joli", "élégant", et "fonctionnel". L'accord gracieux du fond et de la forme, du principe et de l'exécution, tient en un mot.

À l'origine de cette passion pour la beauté on trouve dans l'enfance de cet homme un modèle familial menacé, puis l'équilibre trouvé à l'adolescence dans la stabilité du foyer de son beau-père, un lieu embelli de fournitures curieuses rapportées de l'Inde à l'époque de sa grandeur. "J'essaie de créer une atmosphère dont j'ai été privé enfant. Tout est là, c'est une histoire d'atmosphère". Il fut un jeune homme précoce mais inadapté, connut Oxford, les années 1960, la charnière entre une Europe productrice, religieuse, éduquée, et le monde moderne passif, consommateur, avide de loisirs.

Au terme de l'université, Sotheby's lui offre un emploi mais Kime se retrouve à la tête de sa propre boutique par la rencontre fortuite d'une héritière qui cherchait un antiquaire pour l'aider à vendre sa collection de famille. En 1970, il épouse Helen Nicoll, auteur de livres pour enfants, et le couple s'installe dans une ancienne école gothique. La propriété est si vaste que Robert Kime y ouvre un commerce d'antiquités spécialisé dans les objets antérieurs à 1700. "Chaque salle doit commencer par un tapis" sera sa devise, ainsi commenceront les premiers voyages en Egypte et en Turquie pour y trouver des textiles anciens.

En pleine dégringolade libérale-libertaire 1970, alors que la transmission s'effondrait, quelques rares passionnés remontaient la source. Ce parcours eut pour Kime deux étapes. Sa première période antiquaire lui enseigna les étoffes, objets et motifs issus des colonies qui venaient de fermer. Dans sa seconde période, la plus hardie et la plus belle, il devint en 1988 fabricant de ces objets, aussi la production d'ornements tombés en désuétude trouva par cette initiative une résurrection.

Les créateurs compétents sont en général formés d'une base de culture classique à laquelle ils ajoutent peu à peu des apports exogènes. Peu nombreux, ils sont des hommes ordonnés, configurés à un ordre supérieur, à un Surmoi qui leur enseigne le bon usage en toutes choses, et s'ils extravaguent parfois ils ne transgressent jamais. Chez les hommes de goût la seule faute grave est la faute de goût.

Le grand désarroi des gens riches: comment dépenser l'argent. How to spend it est d'ailleurs le titre d'un mensuel catalogue à snobismes hors de prix. L'éducation du goût permet des économies, et une conduite de vie où s'enrichir et dépenser concernent l'esprit aussi. Les hommes seront davantage portés à l'héllenisme s'ils ont côtoyé enfant chez leur parent un buste d'Athéna.

L'offre d'ameublement pour la bourgeoisie a versé depuis la fin des année 1980 dans l'asepsie de loft Patrick Bateman, dans la cuisine et salle d'eau de style "bloc opératoire", dans l'armoire en métal, dans le noir et blanc. L'épure était chez les mondains une aubaine pour fuir dans l'abstrait, une transposition concrète d'un rapport au monde imposé. Le lissage des textures, la granulométrie faible, visaient à présenter un visage objectif, glissant, neutre. Les européens avaient soudain honte de tout charme qui leur soit spécifique et c'étaient les débuts de l'art-robot, anti-local, anti-artiste. Certains historiens avaient compris que 1945 serait une épuration non pas ponctuelle mais le prélude à une épuration continuelle. Épurer les lignes du mobilier était une manière d'offrir des surfaces où un coup ne peut que ricocher. Passion nouvelle, il fallait ne laisser nulle prise à la critique, n'être jamais soupçonné pour ses goûts de quelque intention condamnable. Qu'est-ce que nos intérieurs sinon les lapsus de nos intentions profondes? Un chez-soi, c'est soi-même rendu lisible par les autres. Une époque de toute-puissance du second degré dans les invitations à dîner commençait, langage de l'équivoque et du compromis, grammaire de toutes les servitudes. Ne pas nommer, ne pas assumer, ne pas penser. Patrick Bateman est l'archétype du mondain lisse, au point qu'il est contraint de chercher une soupape dans la violence, au point d'épurer L'Épuration elle-même pour pouvoir la supporter.

Robert Kime s'est consacré au parti-pris, au subjectif, au palpable qui se donne tel qu'en soi-même, il a pris le risque du ridicule et a triomphé par la beauté. Ne dit-on pas d'un travail très réussi qu'il est "désarmant"? Ainsi de ces arrangements mobiliers qui tombent sous le sens au point qu'ils renvoient même le second degré dans son repaire, complètement battu. En une époque de showroom publicitaire Robert Kime a osé la ligne courbe, le matériau noble, la texture granuleuse présente au toucher. En une époque de grisaille et de conformisme Robert Kime reste la solution idéale pour colorer son intérieur en lui conservant un goût parfait.

#Robert Kime#home decor#antiques#Fabric#Craft#Paisley#London#Style#Paris#Éclectique#home interior#interior design#interior decorating#Chelsea

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

One day more (Le grand jour) translation from the new châtelet french version

(Valjean)

The great day (Le grand jour)

Another day another destiny (Une autre vie une autre destinée)

Delivered from having to run to perpetuity (Délivré d'avoir à fuir à perpétuité)

But today the final judgment, every man is judged for his crimes (Mais aujourd'hui jugement ultime, chaque homme est jugé pour ses crimes)

In broad daylight (Au grand jour)

(Marius)

Tomorrow I won't see her again (Demain je ne la verrai plus)

My blood runs cold in my veins (Mon sang se glace dans mes veines)

(Valjean)

The great day (Le grand jour)

(Cosette & Marius)

Tomorrow I won't see you again (Demain je ne te verrai plus)

It is like lighting striking me (C'est comme la foudre qu'on m'assène)

(Eponine)

Tomorrow alone in my story (Demain seule dans mon histoire)

(Cosette & Marius)

Will I lose you forever? (Vais-je te perdre à tout jamais?)

(Eponine)

A great day lost without seeing him (Un grand jour perdu sans le voir)

(Cosette & Marius)

When my life has barely begun (Quand ma vie commence à peine)

(Eponine)

A little more alone every night (Un peu plus seule chaque soir)

(Cosette & Marius)

And I swear I will be true (Et je jure d'être fidèle)

(Eponine)

I dream of him in my memory (Je le rêve dans ma mémoire)

(Enjolras)

The great day is for tomorrow (Le grand jour est pour demain)

(Marius)

Should I go where she goes (Dois-je aller là où elle va)

(Enjolras)

Tomorrow on the barricade (Demain sur la barricade)

(Marius)

Or follow my brothers in battle (Ou suivre mes frères au combat)

(Enjolras)

The great day dawns at last (Le grand jour se lève enfin)

(Marius)

How to proceed, do I have the right? (Comment faire, ai-je bien le droit?)

(Enjolras)

And the human rights are being written (Et les droits de l'homme s'écrivent)

(Everyone)

Friends, it is time (Amis, c'est l'heure)

Tomorrow comes (Demain arrive)

(Valjean)

The great day (Le grand jour)

(Javert)

Their short pants riot (Leur émeute en culottes courtes) *(see footnote)

I will follow them in their ranks (Je les suivrai dans leurs rangs)

I will push them without them doubting (Je les pousserai sans qu'ils s'en doutent)

To splash themselves with their blood (À s'éclabousser de leur sang)

(The Thénardiers)

They're going into the pipe breaker, we wait for the smoke (Ils vont au casse-pipe, on attends que ça fume) (*see footnote)

When they have lead in their feathers we pluck them (Quand ils ont du plomb dans l'aile nous on les plume)

A jewel here, a little sou there (Un bijou ici, un petit sou en face)

We just have to wait for the hunt to start ([Il n'y a] Y'a plus qu'à attendre l'ouverture de la chasse)

(Les Amis)

The great patriotic day (Le grand jour patriotique)

Progress starts again (Le progrès reprend sa marche)

Fighter of the future (Combattant de l'avenir)

Re-emerged from his shroud (Ressurgi de son linceul)

By beautiful hope (Par l'espérance magnifique)

Of a new world yet to be built (D'un nouveau monde à construire)

To the people's will! (À la volonté du peuple!)

(Marius)

My place is here, next to you (Ma place est là, auprès de vous)

(Valjean)

The great day! (Le grand jour!)

(I will now separate the parts by characters because they all sing at the same time)

(Cosette and Marius)

Tomorrow I won't see you again (Demain je ne te verrai plus)

My blood runs cold in my veins (Mon sang se glace dans mes veines)

Tomorrow I won't see you again (Demain je ne te verrai plus)

It is like lighting striking me (C'est comme la foudre qu'on m'assène)

(Eponine)

Tomorrow alone in my story (Demain seule dans mon histoire)

Tomorrow all alone in the dark (Demain toute seule dans le noir)

(Javert)

With the people's heros (Avec les héros du peuple)

With those new strategists (Avec ces nouveaux stratèges)

Knowing their little secrets (Instruits de leurs petits secrets)

I will close the trap (Je refermerai le piège)

Their short pants riot (Leur émeute en culottes courtes)

I will follow them in their ranks (Je les suivrai dans leurs rangs)

I will push them without raising a doubt (Je les pousserai sans qu'ils s'en doutent)

(The Thénardiers)

They're going into the pipe breaker, we wait for the smoke (Ils vont au casse-pipe, on attends que ça fume)

After they gut themselves we take their feathers out (Après qu'ils s'étripent on leur ôte les plumes)

They're going into the pipe breaker, we wait for the smoke (Ils vont au casse-pipe, on attends que ça fume)

When they have lead in their feathers we pluck them (Quand ils ont du plomb dans l'aile nous on les plume)

(Valjean)

Tomorrow we leave without regret (Demain nous partons sans regret)

(Valjean and Javert)

Tomorrow is the final judgement (Demain c'est le jugement dernier)

(Everyone)

Tomorrow we'll know if God comes to finally announce his return (Demain nous saurons si Dieu vient annoncer enfin son retour)

Finally (C'est enfin)

It's tomorrow (C'est demain)

The great day! (Le grand jour!)

*"Leur émeute en culottes courtes" translates literally to "Their riot in short pants/underwear". It mostly is just Javert insulting the revolution saying it's ridiculous. I genuinly could not come up with a good translation without having to drastically change the lyrics

*"They're going into the pipe breaker, we wait for the smoke" It makes more sense in french, but most of the Thenardiers lines are comparing the students to pigeons or bird (Like waiting until they have lead (bullets) in their feathers to pluck them). I found the lines really clever but the first one does work best in french than english.

#as usual if you have any suggestions to help with the translation comment!!#les miserables#les mis#les mis chatelet#les mis french#les mis translation#jean valjean#javert#one day more#This was so hard omg#Javert's lines are always so tough to translate but it's so good

34 notes

·

View notes