#ontological argument

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

--

Q: What are the three most compelling arguments for the existence of gods - concise answer, name it if it has a formal name. And what are the most straightforward refutations of these arguments - concise answer.

Grok: Arguments for the Existence of Gods:

1. Cosmological Argument:

Description: The argument posits that everything that exists has a cause, and there must be a first cause or "uncaused cause" which is God.

Refutation: The universe might be eternal, negating the need for a first cause, or the cause could be an impersonal force rather than a personal deity.

2. Teleological Argument (or Design Argument):

Description: The complexity and apparent design of the universe suggest a designer, akin to how a watch implies a watchmaker.

Refutation: Complex structures can emerge from natural processes (evolution by natural selection), and the universe might not be precisely "designed" for life, considering most of the cosmos is hostile to it.

3. Ontological Argument:

Description: Proposed by Anselm, it argues that God is the greatest conceivable being; existence in reality is greater than existence in the mind alone, hence God must exist.

Refutation: Existence isn't necessarily a property that can be predicated in this manner; the argument might commit the fallacy of assuming that because something can be thought, it must exist.

Straightforward Refutations:

Cosmological: Challenges the necessity of a personal first cause by suggesting naturalistic explanations like the Big Bang or an eternal universe.

Teleological: Points out that apparent design can result from natural selection and physical laws without a designer.

Ontological: Criticizes the logic by arguing that "existence" isn't a property like "redness" or "largeness" that can be part of a definition.

These arguments and their refutations highlight the ongoing philosophical debate about the existence of deities, showing that each argument has its strengths but also faces significant challenges.

==

This is the best they've got.

#arguments for god#god existence#atheism#fallacies#cosmological argument#teleological argument#ontological argument#religion#religion is a mental illness

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

God is that than which nothing greater can be conceived

Ok phloomer. Suppose there was a greatest conceivable entity, E. Clearly, we may easily conceive of its creator, the E-generator g(E), which is obviously greater.

Additionally, it is clear that two such entities would be greater than one, three greater still, and so on; and again, we may easily conceive of any number of any entity we have already thought of.

#ontological argument#only convincing to people who will be burned at the stake if they object#theology verging on nonsense#anselm can't count on his fingers and should not be attempting to reason about infinities

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

It says that "evil", such as we see it, is better understood as a lesser good. The fact that we can even conceive of good and evil as concepts strongly suggests supernatural sources of these concepts, and the horror we feel at evil is partly justified, in that we need to aspire to a higher good (union with the Divine) rather than settling for a lesser good ("evil", so-called), but partly a feeling of insecurity within ourselves, in that we have not come to terms with darker, instinctive or destructive forces within us, which if properly used, are actually forces of purification and preparation for union with the Divine, in the sense of the Divine Body.

If god is unable to prevent evil, then he is not all-powerful.

If god is not willing to prevent evil, then he is not all-good.

If god is both willing and able to prevent evil, then why does evil exist?

If god created everything then that means he created evil. And if that is the case what does that say about god?

686 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Ontological Argument

The ontological argument claims that God’s existence can be demonstrated simply through reasoning. Ontology is the branch of philosophy that explores the whole concept of existence. It is an a priori argument, in that it works from first principles, pure conceptual truth and definition in an attempt to demonstrate the existence of God. It is also deductive, using logic rather than empirical evidence.

According to the ontological argument, everything (with the exception of God) exists in a contingent way; it depends upon other factors. Human beings are contingent beings because they would not exist if their parents didn’t exist before them – absolutely everything else exists contingently too. However, God is not a ‘thing’; He has not come about because of anything; there was no time when God didn’t exist. Some, such as Paul Tillich, argue ‘exists’ isn’t the right word to use of God at all.

Anselm and the ontological argument

Anselm starts by defining God as ‘that than which nothing greater can be thought’. God is understood to be the highest sum of all perfections, where absolutely nothing could ever surpass God in any way. He argued that of we have an idea of a God who is perfect in every way, where nothing could possibly be greater, then this God must exist in reality. This is because a God who just exists in our heads – something we imagined to be great but doesn’t actually exist – would be inferior to a real God, and because God cannot be inferior to anything, He must exist.

Analogies can be used to understand this point: what would be greater: a huge heap of cash that exists in your imagination, or the same heap of cash in real life? In Anselm’s understanding of God, no one could seriously argue that a non-existent God would surpass an existent God in greatness.

So, his first form of the ontological argument follows this line of argument:

God is that than which nothing greater can be thought.

A real, existent being would be greater than an imaginary, illusionary being.

Therefore, the concept of God is surpassed by an actual, existent God.

In the second form of his argument, very similar to the first, he argued that it was impossible for God not to exist, because contingent beings are inferior to beings with a necessary existence:

God is that than which nothing greater can be thought.

Because God is unsurpassable in every way. God must have necessary existence.

Therefore God exists – necessarily.

God must exist because a necessary being cannot fail to exist. According to Anselm, necessary existence is part of the definition of God – you cannot talk about a God who does not exist, because He would not be God.

Analytic and synthetic propositions

The ontological argument can be understood by drawing a distinction between two kinds of propositions.

An analytic proposition is true by definition, e.g. ‘bachelors are unmarried men’. This proposition doesn’t need to be tested, because it can be arrived at by deduction – the concept of being a bachelor involves the concept of being unmarried, and a man. Anselm, in his ontological argument, claims that the statement ‘God exists’ is analytic – the concept of God involves the concept of existence, and without existence, the concept of God wouldn’t exist.

A synthetic proposition adds something to our understanding, beyond the definition – we need more than deduction to know if it is true or not: experience. ‘The corner shop sells newspapers’ is a synthetic proposition, because the concept of corner shops doesn’t include the concept of selling newspapers – you would have to go and check to know the truth of the proposition.

Anselm argued that ‘God exists’ is an analytic a priori statement, making reference to Psalm 53:1: “The fool says in his heart, “There is no God” They are corrupt and their ways are vile.” He found it difficult to understand how anyone could have the concept of God as ‘that than which nothing greater can be thought’ without also realising that God must exist.

Gaunilo’s Criticisms of Anselm

Gaunilo was a Christian, but he thought Anselm’s argument was not logical. He claimed that these logical flaws would be made obvious if we replaced the idea of God in his argument with an island. We could imagine the most excellent Lost Island, and then, using Anselm’s logic, go on to say that for such an island to exist in our minds means that this is inferior to the same island existing in reality. It is truly the most excellent, it cannot have the inferiority that comes from it being a concept only, it must exist in reality. But clearly, there is no such island in reality, we cannot bring something into reality just by defining it as a superlative.

Anselm replied to this argument by saying that although Gaunilo was right in the case of an island, the same objection did not work when the ontological argument was used of God, because an island has a contingent existence whereas God has a necessary existence. The argument only works with God because of the uniqueness of God and how He exists.

Aquinas’s criticisms of Anselm

Thomas Aquinas argued that the existence of God could be demonstrated through a posteriori arguments, but not through a priori reasoning alone. One of his points was that God’s existence cannot be self-evident. He said that if we take a statement such as ‘Truth does not exist’, it in nonsensical because no one can accept the truth of ‘truth does not exist’ unless truth actually does exist. It is impossible to have a mental concept of the non-existence of truth because it is a contradiction in terms. However, it is not impossible to have a mental concept of the non-existence of God, because people quite clearly imagine it. If we can imagine a state of godlessness, then it cannot be a contradiction in terms, despite Anselm’s claims.

Aquinas also acknowledged that God will always remain unknowable to the finite human mind, questioning whether everyone would accept Anselm’s definition of God as ‘that than which nothing greater can be thought’. Aquinas argued that we do not all share an understanding of what God is, and rejects the premise of Anselm’s argument. He was aware of the limitations of the human mind to comprehend the nature of God and emphasised that, at least until after death, we have to accept that God is mysterious and beyond human comprehension.

Descartes’s view of the ontological argument

Descartes believed that there are some concepts that are innate and universally shared by all of humanity, such as equality, cause, shape and number, as well as an understanding of what God is. We understand God to be the supremely perfect being, with every perfection as his attributes, ‘perfection’ meaning the traditional attributes of God such as omniscience, omnipotence and omnibenevolence.

He used the analogies of a mountain and of a triangle to explain. He claimed that existence is part of the essence of God, just as three angles adding up to 180 degrees are part of the essence of a triangle, and a valley is part of the essence of a mountain. He recognised that these analogies have their limitations, as although we may not be able to think of a mountain without a valley, the mountain-and-valley combination in our imaginations doesn’t necessarily exist in real life. However, for God it is different because his nature involves perfections rather than angles or valleys, and for Descartes, existence is a perfection.

Because God has all the perfections, and existence is a perfection, God therefore exists. And because God is perfect, he must be unchanging, so he must always have existed and will always continue to exist for eternity.

Kant’s critique of ontological arguments

Kant’s major criticism of Descartes’s argument was ‘existence is not a predicate’ – in other words, existence is not a characteristic or attribute of something. Predicates describe what that thing is like – tall, green, round etc, but ‘existence’, Kant argued, is not the same as a predicate as it doesn’t tell us anything about the object that would help us to identify it in any way. When we say something ‘exists’, we are not saying that it has a certain characteristic, but rather that this concept, with all its characteristics has been ‘actualised’ or ‘exemplified’. His point is that when we are thinking of God, whether through Descartes or Anselm’s arguments, we are thinking of a concept, and whether that concept is actualised in the real world is an issue that cannot be resolved by simply adding ‘existence’ to the different predicates. We can predicate of a triangle that it has three sides, and that its angles add up to 180 degrees, but we would have to investigate further to find out whether the triangle we are picturing in our minds has been actualised.

He used the example of a hundred Prussian dollars to illustrate how existence is not a predicate. Adding ‘exists’ to the idea of God, as a predicate, doesn’t add anything new to what we understand by God, but is just a comment on whether he exists. In the same way, an imaginary $100 is not ‘added to’ if we substitute it for a real $100 – we are talking about the same amount of money either way.

Some, such as Norman Malcolm may argue against this by saying that existence is usually not a characteristic that helps us distinguish between one thing and another and so usually is not a predicate, but necessary existence is a characteristic that does draw a distinction between God and everything else, just like God’s other characteristics of omnipotence, omnibenevolence and omniscience. However, this makes the argument circular: we have to accept that God exists necessarily to come to the conclusion that God exists necessarily.

Bertrand Russell on the ontological argument

He criticised it by asking us to consider the statement ‘the present King of France is bald’. This statement is not true, but that doesn’t mean that therefore the statement ‘the present King of France is not bald’ is true, because there is no present King of France. Our use of words and the way we apply predicates, such as bald and not bald, is not enough to demonstrate that something exists, and when we apply predicates to something whose existence is a matter of uncertainty, we cannot expect the normal rules of linguistic logic to apply.

Discussion points

A priori arguments can be persuasive as they lead us to a certain truth, whilst a posteriori arguments can only lead to probabilities.

He ontological argument can seem like an intellectual puzzle made for elite, educated people meaning it is quite inaccessible. People often want to see evidence for themselves using their own senses, rather than rely on the conceptual reasoning of philosophers.

The ontological argument is not convincing enough to make someone who doesn’t believe in God change their mind, BUT Anselm did not set out to convert non-believers, he was simply helping those who already held a belief to gain a deeper understanding of His uniqueness and greatness. Religious belief is much more than just an intellectual acceptance of certain assertions, but involves, emotions, intuitions and commitment. It does not fall simply on the strength of a logical argument.

Faith in God seems to demand an element of uncertainty, and a willingness to take risks. God may need to remain partially hidden from the world to maintain epistemic distance, meaning the world should remain ‘religiously ambiguous’ so people have a choice. Only with this epistemic distance is it possible for humans to have a genuinely free will to exercise faith – if God’s existence were undeniable, faith would mean nothing.

#a level religious studies#a level revision#a levels#ocr religious studies#ocr rs#philosophy#religious studies#anselm#ontological argument#arguments for the existence of god#arguments against the existence of god#the existence of god#descartes#kant#immanuel kant#gaunilo#aquinas#thomas aquinas#arguments based on reason#rene descartes#analytic and synthetic arguments

1 note

·

View note

Text

Ontological argument of St. Anselm (1033–1109) according to which God’s existence can be deduced merely from the definition of God, such that atheism leads inevitably to self-contradiction. One distinctive of the argument is that it relies on pure reason alone with no dependence on empirical premises. Various versions of the ontological argument have been developed and defended, and opinion is sharply divided even among Christian philosophers over whether there are, or even could be, any sound versions.

1 note

·

View note

Text

S6E26 The Moral and Ontological Arguments

By: Dr. Brian Chilton and Curtis Evelo | April 13, 2023 On episode S6E26 The Moral and Ontological Arguments, Dr. Brian Chilton and Curtis Evelo discuss two additional arguments that contend for the existence of God. The ontological argument holds that God’s existence is both necessary and perfect by the nature of reality. The moral argument asserts that any moral code implies the existence of a…

View On WordPress

#Anselm of Canterbury#Bellator Christi Podcast#Curtis Evelo#Dr. Brian Chilton#Moral argument#Necesary being#ontological argument

0 notes

Text

I love William James’ writings on mescaline and peyote. He takes a bunch of drugs and he’s like “I UNDERSTAND HEGEL NOW!!” And then he follows up in a couple of days when he’s sober like, “yeah, I didn’t understand shit”

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

Heard new arguments for why god isn't evil that go like "well god is ontologically different from people as a timeless spaceless being so it's more like killing someone in their dream to wake them up than actual murder" and "god has different moral responsibilities as a being who can know the future" I'm so excited it's like pulling holographic Pokemon cards for my collection

#i will call these built different argument and the can down the road defense#listen listen listen. okay. they used the word ontologically verbatim#i didn't just learn the word yesterday or something

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

i cant believe we got black bald woman jesus before we got palestinian-looking jewish jesus. this is not a criticism but it is funny

#i actually love this concept black and womanist theologians have been saying for years we have to begin to see jesus christ as black or as a#literally both of my graduate theses have been arguments that jesus is an ontological woman. however

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

simulation theory reminds me a lot of the ontological argument for the existence of god

both are based on making a ridiculous-yet-unstated assumption about the fundamental nature of the universe, then going "Now, given that this assumption is obviously correct..."

#assumption for simulation theory: 'it is possible and desirable to create a simulation this huge with Sapient Agents Capable Of Suffering'#assumption for ontological argument: 'being able to imagine something is equivalent to that thing being real'

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Philosophy of the Problem of Other Minds

The "Problem of Other Minds" is a classic issue in philosophy, particularly in epistemology and the philosophy of mind. It addresses the question of how we can know that other people have minds and mental states similar to our own. This problem challenges our understanding of consciousness, perception, and intersubjectivity, raising profound questions about empathy, communication, and the nature of human relationships.

Understanding the Problem of Other Minds

At its core, the problem is about the epistemic gap between one's own direct experience of their mind and the inference that others have similar mental experiences. While we have direct access to our thoughts, feelings, and sensations, we do not have the same access to the minds of others. We can only observe their behavior and make inferences about their mental states.

Key Questions and Issues

Epistemological Challenge: How can we justify the belief that others have minds? Our knowledge of other minds is indirect, based on the observation of behavior and the assumption that similar behavior implies similar mental states.

Analogical Argument: One common response is the analogical argument, which posits that since other people exhibit behavior similar to ours and we know that our behavior is caused by our mental states, it is reasonable to infer that their behavior is caused by similar mental states. However, this argument is often criticized for its reliance on analogy, which may not provide a solid epistemological foundation.

Behaviorism: Some philosophers, particularly behaviorists, argue that mental states are nothing more than behavioral dispositions. According to this view, to ascribe a mental state to someone is simply to describe a set of behaviors and tendencies. This approach attempts to sidestep the problem by redefining mental states in terms of observable behavior.

Phenomenological Approach: Phenomenologists focus on the direct experience of intersubjectivity, emphasizing empathy and the shared human condition. This approach suggests that we can understand other minds through a direct, empathetic engagement with others, rather than purely inferential reasoning.

Philosophical Skepticism: Some argue that the problem of other minds leads to a form of skepticism. If we cannot have direct access to other minds, how can we be certain they exist? This skeptical view challenges the certainty of our knowledge about other people's mental lives.

Theory of Mind: Developmental psychology and cognitive science explore how humans develop the ability to attribute mental states to others. The "theory of mind" posits that humans naturally develop an understanding that others have beliefs, desires, and intentions that may differ from their own. This cognitive ability is crucial for social interaction and communication.

Functionalism: Functionalist theories in philosophy of mind suggest that mental states are defined by their functional roles rather than by their intrinsic properties. According to functionalism, if an entity (human or artificial) behaves in a way that fulfills the functional role of a mind, it can be said to have a mind.

Philosophical Implications

Ethics and Morality: The problem of other minds has significant ethical implications. Recognizing that others have minds is foundational for empathy, compassion, and moral consideration. If we doubt the existence of other minds, it undermines the basis for ethical behavior and interpersonal relationships.

Artificial Intelligence: The problem of other minds extends to the realm of artificial intelligence. As we develop more advanced AI, questions arise about whether these entities have minds and how we should treat them.

Intersubjectivity: Understanding other minds is crucial for communication and social interaction. The problem highlights the importance of shared experiences and common understanding in building social bonds and communities.

The Problem of Other Minds remains a central issue in philosophy, challenging our understanding of consciousness, perception, and intersubjectivity. While various approaches attempt to address this problem, it continues to provoke deep philosophical inquiry into the nature of mind and our knowledge of others.

#philosophy#epistemology#knowledge#learning#education#chatgpt#ontology#metaphysics#psychology#mind#Problem of Other Minds#Philosophy of Mind#Analogical Argument#Behaviorism#Phenomenology#Theory of Mind#Functionalism#Intersubjectivity#Philosophical Skepticism

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Most humbling experience of my life: met a group of Italians with a translator and asked if they were going on the same train as me (so i could hijack their translator 🙃) this tiny 14y/o looking girl took one look at my ticket and said “your train is at 15:00 not 13:00, that’s 3pm since you’re American”

#personal#i swear on every deity that metaphysically exists due to the ontological argument.. i thought the ticket said 13:00#china

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

if god exists it is impossible that it is possible that he does not exist.

#tep.txt#philosophy posting#this is obv not a philosophical argument. but if i believe in god it seems i may have to concede the ontological argument's validity#and im not happy abt it

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

can we finally admit that all the arguments that go "if you heard me say something something men and though i was being transmisogynistic then maybe YOU'RE the transmisogynist for assuming i'm talking about trans WOMEN when i said MEN or do you not agree that trans women are women? checkmate" are so insipid and lame. like ah yes there is famously no demographic of people who ever refers to trans women as men when expressing hatred of them and of course no person has ever subconsciously thought of trans women when they say "men" and therefore those silly trans women are just overreacting and looking for problems where they don't exist

#and i mean yeah there are a lot of stupid arguments out there (made by tme people) that saying ''i hate men'' is terfy or whatever#but those have actual counterarguments you can make grounded in real analysis and not some kind of dumb ontological gotcha

1 note

·

View note

Text

PROOF OF THE ONTOLOGICAL EXISTENCE OF MAGMAR

Definitionally, Magmar is the Pokémon than which nothing greater can be conceived (that is, Magmar is the greatest possible Pokémon, maximally perfect in all respects).

Magmar exists as an idea in the mind.

A Pokémon that exists in reality is, ceteris paribus, greater than a Pokémon that exists only as an idea in the mind.

Thus, if Magmar only exists as an idea in the mind, it is possible to conceive of a Pokémon greater than Magmar.

It is impossible to imagine a Pokémon greater than Magmar (as Magmar is maximally perfect in all respects).

Therefore, Magmar exists.

#personal#(yes i know arguments of this form are weak in a way the original ontological argument isn't)

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

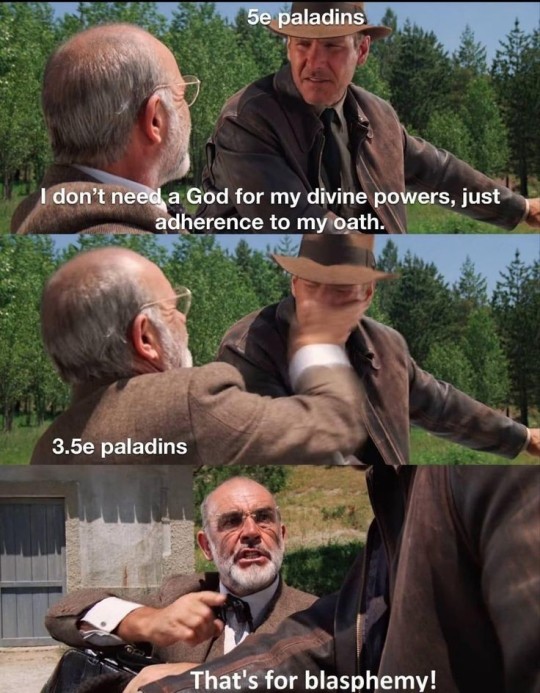

I am the DM for both of these paladins, watching them fight it out and genuinely (and in-lore) supporting both of their theological cases.

497 notes

·

View notes