#onion king

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Gay pride happens in June and gay wrath happens whenever hbomberguy drops a 3+ hour video essay about a specific topic

#hbomberguy#Just watched the full 4 hour plagiarism video and go OFF you funky bisexual king#Also I feel like people casually mention that Internet Historian and that Blare chick should've gotten mentioned more but honestly#Good on him for taking down Luke Stephens too-- who is now afaik a huge channel for video game news#So anyway video good go watch it and go support queer content creators who are not James Somerton :)#See y'all in 2024 when he drops a 5 hour essay on Onion farming or whatever#Seta speaks#top posts#5k#10k

13K notes

·

View notes

Text

My love for Benoit Blanc knows no bounds. He's just some guy, he's a genius, he's the new Poirot, he encourages women to speak their mind at people who screw them over, he hates rich people, he's married to malewife Hugh Grant, he dresses like a 70s queer man with access to online shopping, he has no consistent accent other than Vaguely American Southern, he can solve any mystery, he cannot win Among Us, and I would marry the hell out of him him if I wasn't a lesbian and he wasn't a gay dude.

#literally benoit blanc is my beloved i love that silly queer detective SO much#beloved southern guy with funky fashion. king <3#knives out#chives out#glass onion#benoit blanc#my most beloved silly man

28K notes

·

View notes

Text

#dead boy detectives#dbda#crystal palace#niko sasaki#edwin payne#edwin paine#charles rowland#esther finch#david the demon#the cat king#dbda memes#text post memes#onion headlines#reductress headlines

677 notes

·

View notes

Text

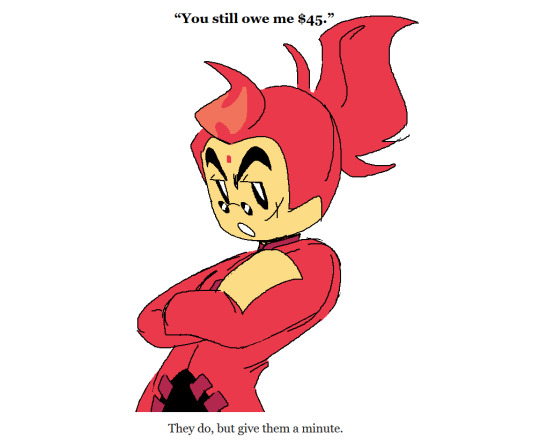

i cant even draw actual art anymore

#original is from a the onion article#lego monkie kid#monkie kid#lmk#lmk mk#qi xiaotian#lmk tang#six eared macaque#liu er mihou#lmk pigsy#hostess#lmk bai he#(i guess)#lmk mei#long xiaojiao#monkey king#sun wukong#lmk sandy#lmk red son#hong hai'er#first time i drew red son actually#shitpost#my art#ms paint#1k#2k#3k#4k#5k#6k

7K notes

·

View notes

Text

THE BOYS ⭐⭐⭐⭐

One of them is a professional yapper

#its clear as the sky that i have a fav and the fav is hiei#yuyu hakusho#yu yu hakusho#yyh#yoshihiro togashi#digital art#ibis paint x#yusuke urameshi#yusuke yyh#team urameshi#urameshi#kuwabara#kazuma kuwabara#yyh kuwabara#yyh kurama#kurama#shuuichi minamino#shuichi minamino#hiei#yyh hiei#hiei jaganshi#hes such a fun character in a tragic way i cant really explain why hes so special#long live the short king#kurahi severe brainworms gave kurama the soft expression bare with me#anyway they re all found family and they actually care a lot about each other but at least the rest of them is not in denial#i mean hiei is not even in denial hes just stupid (got trauma but this is not a serious place to speak about it)#he looks like an onion#giving kuwabara a patch on the face is part of my design at this point#enouuuugh i shut up hope you enjoy#damn the resolution is ASS ibis paint i went trough 123 ads to save this thing and for what

458 notes

·

View notes

Text

that mona lisa smile 🧅

#glass onion#knives out#rian johnson#janelle monae#daniel craig#my art#this movie altered my brain chemistry. I owe me Johnson my life. pulp mystery poster for the king

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

#it reads like an onion headline#it's an article summarising his more recent actions in his allyship with the lgbtqia+ community so actually very wholesome#but its one of the funniest headlines ive seen for a while. go off king#david tennant

130 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mako and Wu as headlines from The Onion

124 notes

·

View notes

Text

Egginfroggin, circa August 2022

So I'm going through some older stuff (read as: stuff I started and then forgot about/got distracted from/let fall to the wayside to haunt me incessantly) and I'm gonna be honest, I completely forgot about this redraw until I saw it, then immediately decided to finish

Anyway

Grisps them

(in their defense, it was an accident)

(program: krita; time: about 2 hours)

#eggin creatin'#submas#subway boss emmet#subway boss ingo#kirby of the stars#kirby nintendo#meta knight#bandanna waddle dee#king dedede#meme redraw#based on the 'WHO KNOCKED OVER MY ONIONS' 'YOU' meme

97 notes

·

View notes

Text

ever since I was a little girl I knew I wanted to be friends with The Giant Monster

#Godzilla#kaiju#it started with King Kong not gonna lie#but it soon became dragons and from there Godzilla was my natural progression#my onions#kaijuposting

79 notes

·

View notes

Text

Oh my god.

I just remembered I never posted this.

#phighting art#phighting#old art#kind of#from last year I think#digital art#art#roblox art#roblox#koiral#I’m in a drive thru of Burger King#can I please get uh#whopper jr with onion rings#subspace is wearing a mcdonalds outfit#subspace phighting#medkit phighting#biograft phighting#sword phighting

136 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Benoit Banana Blanc

#my art#Benoit Blanc#Glass Onion#I have said it numerous times i WILL say it again..bananas in pajamas looking ass fits#its ok king you still slayed#he made those gay little ascots work

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Enjoy my terribly edited memes of KOH characters as headlines from the Onion

89 notes

·

View notes

Text

please help

siivagunner is literally all i can fanart for without needing it to be a joke

girelle for kfad 3???

#art#furry#fanart#deltarune#siivagunner#giivasunner#noelle holiday#girelle#gir hoodie#vylet pony#antonymph#my little pony#friendship is magic#nintendo ds#onion#leek#king for a day#king for another day#kfad#field of hopes and dreams

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

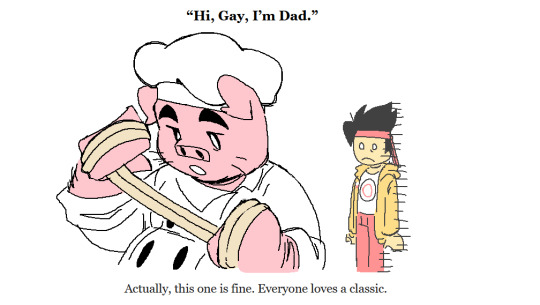

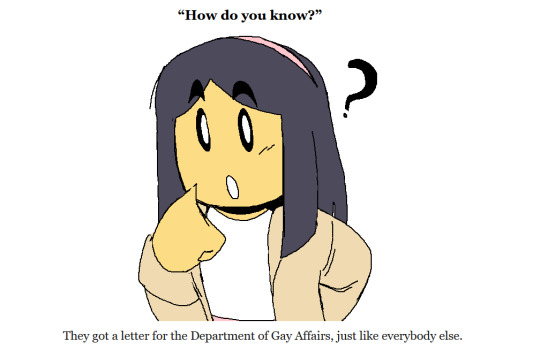

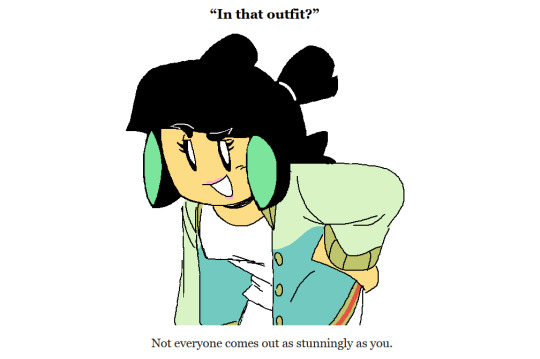

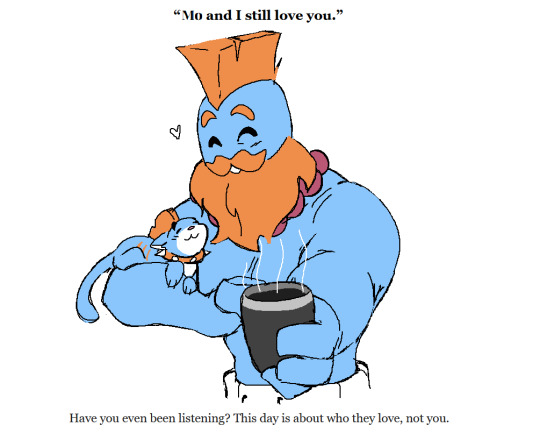

Amphibia as Things to Never Say To Someone Who Just Came Out Pt 2 (Pt 1 Here)

#amphibia#the onion#gay humor#queer#lesbian#bisexual#pansexual#amphibia anne#anne boonchuy#sasha waybright#amphibia sasha#marcy wu#amphibia marcy#sashannarcy#sashanne#marcanne#sasharcy#king andrias#amphibia andrias#andrias leviathan#amphibia yunan#yunnan#general yunan#lady olivia#yulivia#darcy#the core#the guardian Amphibia

517 notes

·

View notes

Text

Where We Choose to Kneel

The mother of truth craves wounds. But not all wounds bleed. [Takes place in the aftermath of the Shattering, prior to Miquella's enchantment.]

Esgar was late.

Not that Varré was particularly inconvenienced by it. Once more, he adjusted his stance, reclining a little into the masonry. The ashlar was cool and damp—a consequence of the perpetual fog. Even now, it hung in the air like an opaque shroud, instantiated by the vague outlines of foliage.

It was simply the principle of the matter. While Varré had never begrudged the often-stationary nature of his work, he preferred it be productive. Or interesting, at the very least. Waiting held the distinction of being neither.

The undergrowth crackled. Varré jerked his head up, a hand hovering over the handle of his mace.

Only to relax, as a familiar, haunting pitch called from the dark. The ululation of some beast, echoing across the water. A stag, perhaps.

Disappointed, Varré settled back in.

The Rose Church hadn’t been his first choice for a rendezvous spot. It was strategically useful, to be sure. It saw little in the way of traffic, being both the least accessible and the least glamorous of the pilgrimage sites. After all, not many of Marika’s supplicants were keen on wading across a lake, just to pay homage to a rotting building.

Yes, it was very useful for keeping people out. Perhaps a little too useful.

No one had yet to ask for his opinion (nor was he inclined to offer it). But as Varré continued to watch the sickle moon climb higher, he couldn’t help but wonder if they had been a tad myopic in their decision-making. Then again, it was possible he was being unreasonably generous.

Esgar had many commendable traits. Punctuality wasn’t one of them.

The reeds along the shoreline hissed—disturbed, as he initially presumed, by the wind. Varré tilted back his head a fraction to study the crowns of the nearby trees.

They were still.

The brush snapped again, much closer this time. It was faint, and partially muffled by the fog, but he could discern the rhythm of encroaching footsteps.

Speaking of which.

With a grunt, Varré pushed off against the masonry. “Taking the scenic route, were you?”

Esgar did not answer. Varré prepared to call out again—only to immediately stay the impulse.

It was seldom that his comrade traveled anywhere without his bitch-hounds in tow. By now, they would have riled themselves up and started baying.

Their absence spoke to their master’s.

This time, his gloves wrapped around the ornate steel of his mace, and did not lessen their grip.

It was slightly more obvious now, the closer they neared. A discrepancy in the gait, marked by a hitch on the second step, as if their weight was unevenly distributed. The stride was wrong, too. It was longer. Heavier.

The earth shifted as Varré dug in his heels. Weighing his options.

Hiding seemed irrelevant, as he’d already done a fantastic job of broadcasting his presence. (The crumbling church didn’t offer many places he could conceal himself, regardless.) Retreat didn’t strike him as a viable alternative, either, since he had no way of knowing whether or not his pursuer could simply outrun him.

Of course, there was always a third option…

Varré exhaled slowly. He forced the tightness from his shoulders, letting the tension bleed out. In its place was a well-practiced nonchalance. He neatly folded his hands upon each other, his mace set aside.

“It isn’t often people venture this way,” he said, in a passably cordial tone. A silhouette was beginning to take shape in the fog. It wasn’t human. “Come to offer your respects to our long-departed queen? Or to rest from your travels, before you resume?”

“Neither,” he growled. The stranger was closing the distance between them. “War surgeon, I wish to speak with thee.”

Varré wasn’t given much time to ponder the request before he stepped fully into view, and all considerations fled.

He was an Omen.

A strange one, at that. The right half of his face was framed by a complex of gnarled horns, several looped around each other in an interlocking helix. A clubbed tail briefly swept into view; ashen-gray, like the rest of his complexion. It bristled like a morning star.

His attire was somewhat dissonant with his physique, however. The cloak he wore was threadbare and tattered at its edges, the fabric loosely draped across him. A thick cord of rope barely secured the interstice between the two folds. The look was completed by what could be charitably described as a walking stick—a staff fashioned from a repurposed branch, longer than Varré was tall. Dark, asymmetric whorls covered the bark, and the handle was burnished.

In spite of himself, Varré was intrigued. The Omen he typically encountered were polled, their horns shorn or removed in their entirety.

He had only ever met one Omen spared that fate.

The stranger continued to regard him. With, if Varré wasn’t mistaken, an air of impatience.

He could relate.

“Venerable Omen.” He bowed his head, and every self-preservation instinct balked at exposing his neck to a potential foe. “Well met. I did not expect to encounter one of your kind so far west. Liurnia isn’t usually graced by your presence.”

At the mention of grace, his scowl deepened.

Very quickly, Varré steered the conversation forward: “I confess to some surprise. Not many are familiar with the war surgeons.”

At least, not any longer. While his faction, strictly speaking, wasn’t dissolved, there was little need of their duties. The Shattering had precipitated violence on a scale not easily replicated since. But in its aftermath, long centuries of stalemate had seen dwindling conflict—and with it, a vacuum which the war surgeons no longer filled. Apart from the occasional skirmish on the Leyndell-Gelmir border, the world labored on. Stagnating.

The stranger shifted. “I’m well acquainted with the raiment of thy…euthanasic order.”

The admission surprised him, and Varré studied him with renewed interest. Age was always difficult to guess in their kind, not helped, in the least, by their considerable lifespan. It had been said in times long passed that the Omen were conscripted as soldiers, but he had never sought to confirm the rumor. Now, though, he wondered. A veteran, perhaps?

Abruptly, the meaning of his words clicked.

“If it’s my services you’re after,” said Varré coolly, “I’m afraid I must decline. My mercy is reserved for the dying, which you, as it stands, are not. Being Omen is not a terminal affliction.”

The single eye narrowed.

“I did not come here seeking death.” His tail lashed, once, flattening the marsh grass behind him. “The ideologies thou cleavest to are of little concern to me.”

Varré faltered. “Then why seek me at all?”

The stranger inclined his head, his features grim. “I know to whom thy loyalties are pledged. I request an audience with thy lord.”

The utterance chilled him, and Varré stilled.

Knowledge of their dynasty was privy to seldom few. Of his lord, fewer still. It was a necessary precaution, as they had no shortage of enemies that would see their efforts undone—fundamentalists, recusants, Omenkillers. Even the Tarnished that he was sent to recruit had to be carefully vetted. Information was kept in the strictest of confidence.

Varré was briefly tempted to ask how he came by it. A single glance at his austere expression, however, dissuaded him. He would be denied, it told him that much.

It also told him that the stranger would not be easily refused. Nevertheless, Varré did.

He smoothed a hand down the front of his gown—rather deliberately lingering over a bloodstain, long seeped into the material. “My apologies,” he began. “But that simply isn’t possible. All audiences with my lord are through prior invitation. He prefers to be acquainted with his guests before they entreat him.”

An unreadable look passed over his face. “We were acquainted, once.”

Uncertain how to parse that comment, Varré ignored it. “Be that as it may, he has pressing matters to attend. I, Varré, however”—he offered another bow, though his gaze remained fixed upon the Omen—“am at your disposal. Whatever you require, my aid shall suffice.”

The stranger took a step closer. Light from the moon struck the side of his face, carving out the angles in shadows. “I did not travel such distance only to parley with his sycophant. I am of even less proclivity to tolerate hindrance.”

Varré righted his posture, threading his fingers together. “I’ve reconsidered,” he said slowly. “Perhaps my mercy can be rendered to you after all.”

“Thou art mistaken, to believe me cowed by tacit threats.” He peered down, his lips pulled into a taut line. “I’ve no ill intentions toward thy lord. But ’tis imperative he and I speak.”

Varré likewise considered himself immune to intimidation. All the same, he hesitated. Bluff or not, he wasn’t confident he could actually best an Omen, and he wasn’t eager to find out.

His hand itched for the comfort of heavy steel. Reluctantly, he tamped down the feeling.

“You misheard me,” he assured, his voice smoothing back into a more pleasant lilt. “However, my answer remains unchanged. You’re welcome to request as many times as you like. But my lord sees none without invitation.”

The stranger grunted. “Then extend me one.”

His audacity was admirable. Foolhardy, but still. “That’s beyond my purview. I’m only a humble messenger.”

Without warning, he took another step closer. Reflexively, Varré mirrored the step back. He held up his hands.

“Hurting me would make a terrible first impression, wouldn’t you agree?”

He stopped.

“Would you be amenable to a compromise?” Varré offered. “Give me your message, and allow me to relay it to him.”

“And have thee slip away under false pretenses?” He snorted. “I think not. Thou wert already tedious to locate once.”

And how the stranger had accomplished that, Varré couldn’t begin to fathom. Esgar’s continued absence, however, pressed upon him with renewed urgency. For the moment, he pushed the concern aside.

“Even if I were to entertain the idea,” he said, not without a hint of disdain, “I fail to see why my lord would receive you. He doesn’t suffer fools, and you’ve done nothing to prove otherwise. You haven’t even given me a name. What makes you think he’ll agree?”

In the gathering darkness, his eye gleamed.

-

“—still three days’ time from Mistwood. They were pinned down on the southern banks of the lake.”

“What accosted them? More soldiers?”

Ansbach glanced down at the report in his hand. “According to Nerijus, it was a dragon.”

The nobles stirred uneasily.

“Wretched beast,” one of them muttered. “I thought their kind had all fled to Caelid.”

“This one didn’t get the missive, it seems.”

“We needed those provisions. Recovering them has to be of the utmost priority.”

“What good will supplies do us if they’ve been incinerated?”

Pointedly, Ansbach cleared his throat, and the bickering ceased. He turned to the figure listening close by, seated upon the chamber stairs like a statue hewn from obsidian. “Orders, my lord?”

Mohg tapped a claw upon the ancient stonework. Each hollow click bounced off of its surface. He did not answer right away, but instead tipped back his face to study the false night sky. The proxy stars glittered like crystalline dust, suspended among the stalactites. He beheld the simulacrum a heartbeat longer before lowering his gaze. “Casualties?”

Ansbach consulted the parchment. “No deaths, but nearly half of his company sustained serious wounds. They’ve been forced to make encampment near the cliff face. With so many injured, they dare not risk leaving, lest the dragon continue to harry them.”

Mohg lapsed into temporary silence. Then: “Eleonora has an…understanding of dragons, as I recall.”

Ansbach nodded.

“Send for her at once. Have her depart for Limgrave with a contingent of Pureblood Knights.”

“My lord,” a noble ventured, “will that be enough to slay it? I don’t doubt their skill,” he hastened to add, as their commander wordlessly turned to stare at him. “But I shudder to think of more lives needlessly wasted.”

“If the dragon can be repelled, then killing it won’t be necessary.” The claw stopped, only to then scrape over the surface. It cut a deep line in the stone. “It is not needless. Pray that the day does not come when I deem your life so easily discarded.”

Chastened, the noble bowed his head. “Y-Yes, my lord.”

“We’re done here.” Unceremoniously, he stood, dismissing the group with a flick of his wrist. “Return to your posts. I want an update as soon as Eleonora’s contingent makes contact with Nerijus’.”

None of them protested—not that they ever did; they knew better—and filed out of the mausoleum. Ansbach tidily rolled the parchment and tucked it under his arm with the other scrolls, before turning on his heel.

“Ansbach,” Mohg called after him, “stay a moment.”

His advisor halted, before turning to face him. “How may I be of service?”

The chains on his clasps rattled faintly as Mohg approached. “The new initiates,” he said, as he drew to a stop across from him. “Tell me of their progress.”

Ansbach immediately straightened. “Training goes well,” he said. “They’ve no shortage of pride nor discipline. The fire in their blood will anneal them, I’m certain.”

“Good,” Mohg rumbled. “Very good.”

Ansbach dipped his head. Long white hair spilled from the loose braid over his back. “If it interests you,” he said, after a moment’s pause, “and barring other matters, would you care to watch? I’ll be instructing them on how to wield the helice soon—”

“Another time, perhaps,” said Mohg.

The scrolls rustled as he adjusted them. “…Of course.”

Mohg caught the lapse, and he suppressed a sigh. Of all the accusations he had borne, sentimentality was the very least of them. Regardless… “My presence isn’t needed to ascertain their skill. So long as you impart yours, I will find no fault.”

Ansbach, clearly caught off-guard by the compliment, looked up. “I am obliged, my lord.”

“Think not of it.” He waved it aside. “Is there anything else I should be made aware?”

To Mohg’s surprise, Ansbach hesitated. “Would you object if, going forward, we held our drills on the turf below the palace?”

The brow over his remaining eye rose. “Is something wrong with the courtyard I allocated you?”

“In a manner of speaking,” Ansbach replied. Unlike his lord, he made no effort to suppress the sigh. “Two of the initiates were—enthusiastic during their spar yesterday, and a section of the floor collapsed.”

Mohg—having grown accustomed to the infrastructure giving out at inconvenient times—merely closed his eye. Slowly, the lid fluttered open, in a look caught somewhere between resignation and exhaustion. “I don’t object. See to it in the meanwhile that the area is kept clear, until I can remove the debris.”

“As you command.” He paused. “Their reflexes will be most impressive, when all is said and done.”

He snorted. “Very droll.”

Ansbach simply folded his arms behind his back. “How go the repairs?”

Mohg grimaced. “Predictably.”

The admission drew his gaze up to the entablature, and the fluted pillars that held it aloft. Grandiose as they were, they still hadn’t escaped the ravages of time. Much of the foundation was marred by gouges and cracks—or, as was the case for one of the arches, missing a column. It was a hazard, and it needed replacing.

Another concession. Like everything as of late.

Repairs, as Mohg had initially believed, didn’t actually meaning fixing things. It meant a constant trade-off between preservation and renovation, and deciding which one took precedence. The original techniques that had built the Eternal Cities were gone, right alongside their creators. They could not be replicated, and thus had to be replaced.

Gutting the dilapidated stone meant substituting it with something inferior. Something lesser. Mohg’s lip curled.

One proposal had involved sending an expedition team upriver—explore the neighboring city, and study its ruins for insight.

It only took one expedition for the idea to be rejected.

The senseless waste of it all settled over his bones. The decay, the obliteration. An entire people, condemned to the dark for the crime of existing.

The memory of steel around his ankle sent a shudder of revulsion through him. Ruthlessly, Mohg shoved it aside.

If Ansbach noticed, he didn’t comment.

“I’ll find somewhere to store the debris in the meanwhile,” he decided. “The caverns below the palace should have enough room to—”

“My lord?”

They turned in unison.

Varré hovered on the mausoleum threshold, his hands wrung together.

“Forgive my intrusion,” he said, as he slipped into the open chamber. Mohg didn’t need to look past the white porcelain, to picture the face beneath it. “But your presence is required. Rather urgently, I might add.”

“I was under the impression you were meeting Esgar,” said Mohg, as Varré stopped before him. The agitation radiating from him was palpable. “Why have you abandoned your post? Where is he?”

“Tardy, as usual,” Varré muttered under his breath. “But that isn’t the problem. You have a…visitor.”

“You brought an outsider here?” Ansbach drew himself to his full height, his unseen gaze reproachful. “Such folly is beneath you.”

Varré whipped his head around. Mohg rested a hand on Ansbach’s shoulder in silent warning, and his advisor relented. He turned back to Varré.

“What kind of visitor?” he asked.

The weight of the question bowed Varré’s head. The answer was slow to come, and when it did, his words were windblown embers, heedless of the things they ignited as they were carelessly dispersed. “The king of Leyndell.”

Mohg stiffened. The reaction was immediate—visceral—and no amount of self-control could suppress the tension that coiled at the base of his spine. Fear was an unwelcome feeling, and it coated the back of his throat like bile. He shook his head, trying to dislodge it. Blood continued to roar in his ears.

He was distantly aware of Varré still talking: “…have information worth extracting from him. At the very least, I didn’t want to act with haste.”

“Haste,” Ansbach repeated, in a tone that required some effort. “Has the meaning of that word changed since I last heard it?”

Varré sniffed. “Should we waste every opportunity that comes willingly to our doorstep?”

“Clearly, since it now appears that assassins knock.”

“I—” The syllable jarred them out of their argument, and they turned to face him. When Mohg went to speak again, the sounds dammed at the back of his throat, and he let out a frustrated noise. “I will abide no scion of the tree. See him removed from the palace.”

Varré folded his arms. “I don’t think he’ll go willingly. Force may be required.”

“And was it force that coerced you to bring him here?” Ansbach asked.

Varré answered—and pointedly refused to look at Ansbach as he did. “I think it might be worth speaking to him. At the very least, I don’t believe it’s a trap. He asked to be brought here, and he came alone. And unless we choose to escort him out, he has no way of leaving.” He rested a fingertip against the chin of his mask. “The king of Leyndell could make a valuable hostage.”

“A hostage requires negotiations,” Ansbach said, and Mohg could hear the restraint on the implied insult. “It rather undermines the point of secrecy.”

With a forced exhale, Mohg composed himself. “Where is he now, Varré?”

“The lower atrium,” he said. “Shall we—?”

“I’ll receive him.” Mohg’s gaze slid toward the pair. “I want you both present. As soon as we’re finished, get him out of my sight.”

They bowed their heads, and silently fell in step beside Mohg as he exited the chamber. Neither dared intrude upon his thoughts as they boarded the dais. It lurched, groaning under the weight of eons, before the stone lift began to descend.

In truth, Mohg doubted the conversation would yield much, beyond the memories of old injustices. It was only curiosity that spurred him.

The Veiled Monarch. Yet another one of Godwyn’s diluted pedigree, if the rumors were correct. The furtive nature of his reign wasn’t improved by Godrick’s foul exploits, and the inextricable comparisons they invited. It was often assumed that his privacy obscured similar perversions. (Outside of the plateau, at any rate. Mohg doubted Leyndell’s subjects were witless enough to gossip in earshot of his soldiers.)

Strangely, the thought comforted him. That after all this time, even Marika’s blessed golden lineage couldn’t escape whatever curse ran in her veins. The wellspring of golden ichor, poisoned to its depths.

The lift shuddered to a standstill. Mohg disembarked, and rounded the bend in the monolith, following the uneven flagstones that curved its base. A pair of Tarnished bowed as he approached. One looked as if about to call out a greeting, only to catch sight of his expression, and quickly avert their eyes as he passed.

The lower atrium, like every other building, hadn’t been spared from deterioration, though it was arguably the least affected. The gatehouse at its entrance was one of the few structures to still have an intact roof. Immense statues, tablets clutched in their grasps, flanked it on either side. Their ubiquity didn’t help shed the feeling of being assessed by cold, dead eyes as the group passed beneath them.

Mohg briefly entertained the thought of summoning his trident. Not that he was anticipating a fight, he mused, as he crossed the gatehouse threshold. But he wasn’t about to allow some wretched man—another stunted bough of the tree—to be in his presence, and think that an Omen was only fit to stand beneath him—

He stepped into the atrium.

And his lungs hitched on a breath that was no longer there.

Morgott lifted his head in silent regard.

“Brother,” he said.

Out of his periphery, Varré and Ansbach turned sharply.

Shock rendered him speechless. For lack of anything constructive to do, Mohg found himself reluctantly drinking in his appearance. The calm, unwavering demeanor was unchanged, although the now-mirrored symmetry of their blindness took him aback. Disturbingly, the horns above his left eye were gone.

He took a step closer—and proximity caused his Great Rune to resonate in the presence of the other Shardbearer. He could feel it calling to the anchor. Like a second heartbeat, drumming a savage rhythm against his ribs.

By the set of his jaw, Morgott felt it the same.

“What deference is owed to the Lord of Leyndell?” Mohg finally asked, when he had recovered enough to do so.

Morgott’s tail swept behind him. “No more than is owed to the Lord of Blood.”

More than sound or sight, a sense of displaced air told him that Varré had crept closer. “My lord?”

He didn’t answer.

Varré hesitated. And then, in a quieter voice: “Mi domine? Quid haberes nos facere?”

“Eum abducemus?” Ansbach offered, his stare not wavering from their guest.

Morgott inclined his head—with wary interest, not comprehension. He didn’t inquire, although his hands gripped the wooden staff more firmly.

The urge to agree was tempting, and Mohg nearly did, the words already half-formed. His claws flexed.

He hadn’t forgotten their last conversation.

But damning pragmatism wouldn’t let him. He couldn’t just—dismiss him, as if countless years didn’t span the gap preceding where he now stood. Mohg remembered well his brother’s many traits—and that rash compulsions weren’t among them. Nor was he inclined to do things in half-measures. He wouldn’t have gone through the effort of finding him were it not important.

Varré hadn’t misspoken—the king of Leyndell would have valuable information.

And Mohg didn’t have the luxury of ignorance.

Pragmatism won, and he pushed the spiteful urge aside. “Omnia bene est,” he answered. “Id sinam. Linquite.”

He didn’t want an audience for the conversation about to follow.

Doubt was etched into every line of his posture, although Ansbach did not contest the dismissal. He bowed low. “Sicut mandas. Ero foras, si me requiras.”

The dark robes fluttered behind him as he left. Varré lingered, just long enough to add, “Etiam ego,” before he followed after Ansbach.

Morgott watched them go. It was subtle, but Mohg didn’t miss the way his shoulders dropped, before his attention shifted back to him. While his expression remained guarded, it wasn’t hostile.

“Thou seem’st hale,” he said, after a moment.

“You don’t,” Mohg replied. “Why are you garbed as a vagabond?”

His nostrils flared, and a moment later he forcibly closed his eye. When it reopened, his brow was furrowed with obvious restraint. It was such a familiar gesture that Mohg fought against the reflex to apologize for whatever childhood misdeed had prompted it.

“Discretion while traveling aside? Humility.” Morgott leaned a little into his staff. Though upon closer inspection, he didn’t appear to be relying on it for support. “Vainglory is not a prerequisite in my service to the tree.”

“Perhaps it ought, if you wish to avoid comparisons to a beggar.”

Morgott’s eye trawled over him.

“I can imagine worse alternatives,” he said.

Mohg could feel what little patience he had beginning to fray. “I’m not required to oblige guests, be they lord or kin,” he said, his teeth snapping around the words. The heavy stoles rippled as he stepped off to the side. “If you’ve come here simply to disparage me, then you’re welcome to leave.”

He waited.

To his disappointment—and relief—Morgott remained. His staff clacked upon the tiles as he approached, reducing some of the distance between them. He was careful, Mohg realized, to not venture too near. To stay outside of striking range.

“Forgive me,” he sighed. “A fortnight’s travel, accosted by the elements, hath done little to better my disposition.”

Nothing ever did, although Mohg bit back the words before he could utter them. The admission, however, seemed bereft of insincerity.

“Quite the distance to travel,” he agreed, inspecting the tips of his claws. “I can only imagine your discomfort after being borne here by palanquin.”

His stormy expression darkened.

Mohg arched a brow. “No?” he asked. “By horse, then?”

“What steed dost thou think can carry me?”

He already knew, but he pressed anyway: “Surely the king of Leyndell did not deign to walk all the way to Liurnia?”

Morgott’s silence answered for him.

“Disgraceful,” Mohg drawled, not bothering to hide the emphasis on the word. “That you would tolerate such insolence from your subjects. Not even an entourage to escort you through the wilds?”

“I don’t require such profligacy.”

“Afraid your men will see something they won’t like?” he asked.

Morgott’s eye darted off to the side. His tail swept closer, coiling loosely around his heels.

“Subterfuge has ever been your repertoire,” Mohg said, unable to keep the note of contempt out of his voice. His brother’s gaze snapped back to him as Mohg began to move, in a slow, gliding circle. He didn’t turn his head to follow him, although his eye tracked his movements. “That would explain why your kingdom believes that a man sits the throne.”

His shoulders hunched. “The throne is not mine to take.”

“Is that right?” His steps slowed. “Does it belong to a Tarnished, then? One of the innumerable you’ve culled in recent years?”

Morgott glared. “Thou hast outgrown the need for simple questions.”

He snorted, and resumed his pace. “I thought as much.”

For a long moment, Morgott didn’t speak. Before Mohg could prompt him, he let out a ragged noise.

“There was a time, once,” he murmured, “when I walked amongst them.”

The words rooted Mohg to the spot. He turned his head to face him, not daring to believe what he’d heard.

“As you are?” he asked, the question scarcely above a whisper.

To his disappointment, Morgott shook his head. “No. ’Twas after the Shattering, when the capital was engulfed by chaos. Almost all of the other demigods had abandoned the city by then.” The vestige of a darker emotion passed over his countenance, before fading into something more impartial. “Leyndell was on the precipice of consuming itself. Little wonder I was undetected when I entered the palace. Had I been, I wouldn’t have chanced upon it at all.”

“Upon what?” Mohg snapped.

“A guise.”

Try as he might, Mohg couldn’t feign a lack of interest. He jerked his head in a vague gesture to continue.

“I knew not what manner of enchantment lieth upon it,” he admitted. “I thought it only a mere veil, at first. Until the gossamer passed over mine eyes, and in my reflection, it rendered a stranger.” His gaze was distant. “I cannot begin to fathom why she kept such a thing.”

She? The meaning dawned on him. The words were painting a picture in his head, and certainly not the picture his brother had intended. “You mean to tell me that you ransacked her chambers?”

Morgott flinched.

The customary scowl returned a second later—but not before Mohg caught the flicker of guilt. “No. I did not fossick through her belongings,” he said harshly. “I was searching for documents. Records. Something to avail me guidance in restoring order of the city. The veil was…serendipitous. It enabled me the means to govern more directly. Losing it…”

His speech dimmed. “Losing it hath exacted certain costs.”

Mohg considered what he said, before, gradually, his attention shifted upward. Toward the bony nodes above his eye, their cross sections laid bare.

From excision.

His fingers curled into his palm. Cautiously, Mohg reached forward, and extended a hand toward his face. Morgott stiffened, but didn’t recoil as he lifted a claw tip, and traced it over the shorn edge.

“Was this the price you paid?” he asked.

Morgott let out an unsteady exhale. It ghosted over his wrist. “No. That was my doing.”

Mohg stilled. “You mutilated yourself,” he said. It wasn’t intended as an accusation, but it came out as such. “Why?”

“Because it would have blinded me.” The strain in his voice became more pronounced. “I watched their trajectory, as the horns spiraled inward. I knew what would happen, should I choose not to intervene.” His eye closed. “I remembered what it did to thee.”

Mohg said nothing.

“I knew the risks,” Morgott continued, “and deemed them worthwhile, if it meant preempting what would follow. ’Twas better than repeating the same mistake.”

He ripped his hand away.

“Mistake?” he spat.

Rage that had once laid dormant now roared in his chest.

“Yes.” Morgott wasn’t disconcerted by the sudden outburst, having weathered them before in their youth. Though the creases around his face deepened. “Should I have gouged the eye out instead? Let it fester into a sepsis which I had not the means to treat?”

Mohg bristled. “You think I should have done as you did?”

“I think thou didst as thou always hast.” Morgott leveled his stare to meet him. “Whatever pleaseth thee.”

The only thing that would have pleased him then was slamming his fist into his brother’s teeth.

“What good would it have done me?” Mohg asked. “What need did we have for sight in that lightless pit? Let it claim my eye, if it meant keeping my dignity. My pride. I would have that, if nothing else.”

“Thou mistakest conceit for pride,” Morgott said. “And ’tis misplaced. Should we lament every tumor that must be resected? Mourn every canker?”

Fingertips dug into his palm, until Mohg felt them break skin.

“It may be your voice,” he said, “but those are her words pouring out of your mouth.”

A hairline crack formed in the bark under Morgott’s hand.

“Say it.” His steps were soundless as he advanced. “Whose fault is it we languished in that cesspool? Whose fault that we endured years of privation? Whose fault that you saw no alternative than to maim yourself?”

His brother’s face hardened. Like the stone beneath him—rigid, senesced. Trodden upon.

“Say it,” he hissed. “Say the name of the woman who left us down there to die!”

“We did not.”

The answer, barely more than a dull rasp, caused Mohg to lose some of his momentum.

“We didn’t perish,” Morgott reiterated, more firmly. But there was a quality to his voice that felt lacking. Misplaced. “But had our existence not been hidden, we would have.”

“You can’t possibly be so naïve to think we were put there for our safety. Those tunnels weren’t made to keep our executioners out. They were made to keep us in.”

“They kept us alive. Beyond the reach of anyone that could harm us. Thou art here to complain because of it.”

“At least I don’t cower behind a lie.”

Morgott’s eye widened, and his tail lashed.

Mohg could feel his anger escaping him in hot, heavy pants, in time with the rise and fall of his chest. He made no effort to stop them. “It rejects us.” The words slid through his teeth, steeped in cold acrimony. “The city, the order, her. All of it. Where is the value in fealty after all rewards are forfeit?”

“Thou art mistaken,” Morgott growled, “to think I labor under such delusions.”

The tattered fringe of his cloak trailed at his heels, as he turned away, and paced across the courtyard. He came to a stop on the edge of the peristyle, his unoccupied hand braced against a column.

“I don’t deny that we are forsaken. How could we not be? Grace was withheld from us the moment we were conceived. We were born accursed. Who amongst my subjects would suffer an Omen as their king?”

He glanced over his shoulder. In the shadows of his face, the golden eye burned.

“But by birthright, Leyndell is mine. And I will pile high a mountain of corpses ere I let a usurper take it from me.”

Morgott turned to face him. “Surely thou, even in thy abattoir, canst understand that.”

“Far better a slaughterhouse,” Mohg rumbled darkly, “than a gilded cage.”

Apart from the abrasive rasp of his tail sweeping over the stone, the atrium was silent.

Until Morgott broke it: “’Twas also thine, once.”

Mohg watched through a narrowed eye as Morgott rejoined him. Still careful, of course, to maintain a certain amount of space. An unspoken boundary.

“The city,” he clarified, when Mohg didn’t react. “Thou hast claim to it as well.”

Mohg sneered. “Is that why you bothered to come looking for me? To ensure I wasn’t intent on stealing your birthright?”

The accusation didn’t rile him further, as Mohg had wanted. Indeed, it looked as if Morgott was visibly reining in his temper.

“Hardly. My reasons for seeking thee out aren’t so ulterior in motive.” The unwavering stare was belied by a hint of uncertainty, flickering at its edges. “But since the subject hath been broached, I see no reason not to pursue it.”

“Which is what, exactly?”

“Thou couldst return with me,” he said.

The simmering rage evaporated, replaced by a yawning chasm that threatened to swallow him. Mohg took a step back, as if doing so could dispel the feeling of being trapped behind teeth. “Why?”

“Traditionally, inheritance is primogeniture. In our case, however, ’tis shared equally.” Morgott cleared his throat. “I don’t expect thee to assume the responsibilities of lordship. Or—”

“No,” Mohg cut him off. “Why are you offering? Out of some misguided sense of propriety?” He folded his arms. “Or is this your pathetic attempt at reconciliation?”

Morgott winced. “…Perhaps some of both.”

“You haven’t done much to convince me.”

“And thou wert the embodiment of hospitality.”

The desire to argue was loosening its grip, and Mohg clung to it with renewed desperation. Hostility was familiar; at least he knew what to do with that. The grim sincerity on his brother’s face, so at odds with his habitual derision—that he didn’t know what to do with.

But he wanted it gone.

“Leave,” Mohg said suddenly.

Morgott blinked. “What dost thou—”

“You’ve made it clear that being here offends you. So let me alleviate your conscience.” The fabric hissed as his robes dragged behind him. He took a step closer, ambivalence shed from him like the Erdtree’s dying leaves. “Get out of my sight, and don’t come back.”

Whatever Morgott’s first reaction to the dismissal had been, it was quickly displaced. The muscles in his jaw tightened as he lifted his chin. “No.”

“That wasn’t a request.”

“And yet mine answer is unchanged.”

Mohg let out a low growl. “Must I remove you?”

“I invite thee to try.”

Neither of them stirred.

“I did not spend all these years searching for thee,” said Morgott, in a low tone, “to be so easily dismissed.” Of all the things Mohg had expected, it wasn’t for him to crouch, and lay his staff upon the floor. When he rose, his hands were splayed. “Thou’st made it clear that I’m to blame for every hardship thou suffered. So let me rectify it.”

He kicked the staff away, and stepped forward. His hands dropped. “Hit me, and be done with it.”

For a single, fleeting moment, Mohg very nearly did. He could all but feel the motes of fire dancing along his claws, his hands awash in their heat. Ribbons of red light trailing at his fingertips. The invocation upon his tongue.

But the longer he stared at his brother—tired, careworn, resigned—the more distant that feeling became. More pointless. Attacking him would do nothing to the person that he actually wanted to hurt. And for all that Morgott espoused her ideologies, Mohg wasn’t blind.

There was an impression around his ankle, too.

Mohg swallowed back the urge, and the incantation with it.

“Why did you refuse to come with me, when I left?” he asked.

Morgott hadn’t anticipated that question, because his face went blank.

“There weren’t any sentries that night. You saw how easy it was.” Mohg could still hear the metallic snap of his shackle, incandescent from the bloody flame. Feel the surge of renewed vigor as the confinement lifted. For the first time in his miserable existence, he’d felt alive. “We could have left together.”

More than anything, he still remembered Morgott wrenching away from him, half-shouting, half-pleading, to get away. Self-recrimination was the hammer, and duty the molten steel, that had been beaten into the shape of his chains. No gaoler, however, had fastened them around his neck. Morgott had done that himself, willingly, long ago in those merciless pits. An act of penance. As if his entire reign hadn’t already been one long expression of it.

Sometimes, Mohg wondered if the endless futility didn’t assuage his guilt. Or if denial was an easier lie to swallow.

He almost didn’t expect him to answer, for how long the silence dragged on. In a way, it didn’t matter. His brother had never needed a veil to obscure himself, with how easily he had learned to guard his thoughts. The trick, Mohg had learned, was to listen for the things that went unspoken. The things that Morgott could no longer bring himself to name.

He waited.

Until Morgott swallowed, thickly. Almost too softly to be heard, he said, “Leyndell is my home.”

Mohg sighed, the last dregs of his anger spent. He went to retrieve the staff. “Then we have an understanding.”

His fingers wrapped around it. There was a strange energy running below the surface, Mohg realized, although he couldn’t identify what it was. It pulsed beneath the wood.

He returned, and held out the staff in wordless offering. Their eyes met.

“You can’t ask me to come with you,” Mohg said, “any more than I can ask you to stay.”

Mohg couldn’t remember the last time he’d seen grief upon his face. It was faint, but unmistakable.

And it was gone before he had the chance to assess it; an impression in the sand, swept away by unremitting tides. Morgott reached out, and accepted the staff. “No,” he murmured. “I suppose not.”

He leaned into it, his free hand tucked in the folds of his cloak.

Which left them…there. Painfully aware of each other.

Vulnerability was just as foreign as it was intrusive, and Mohg suddenly found himself unable to meet his gaze. He tipped back his head to avoid it. As ever, the glow from the false night sky was calming, and Mohg could feel some of the tension leave him.

“What was it that brought you here?” he asked. “I can’t imagine you were content to leave the Erdtree unguarded.”

Likewise, Morgott had turned his attention upward, and he appeared to be studying the stars. He let out a quiet, mirthless sound that might have been laughter, once, if not made rusty from disuse. “What maketh thee believe it is?”

Leyndell didn’t have its reputation as an impenetrable fortress for nothing. Still, Mohg wondered.

“As to thy question…” Morgott flicked his tail. An idle gesture, if Mohg ever believed him capable of such a thing. “How dispersed are thy scouts?”

Tonight was determined to keep wrong-footing him. “What?”

“Do thy activities extend across the continent? Or are they more localized?” he continued. The insouciance was at odds with the nature of his inquiry. “The war surgeon already confirmeth thy presence in Liurnia.”

It was too specific to be anything innocuous, but Mohg couldn’t discern his motives. He folded his arms behind his back. Thinking.

“It’s selective,” Mohg said. His reply was delayed, as he measured the repercussions of sharing that information. Deciding there were none, he continued: “Limgrave receives most of our attention. Liurnia and Caelid, to lesser extents.” He was careful to omit Altus. “There are a handful of places we avoid—the Barrows, Aeonia, Stormveil. I’m sure you can gather why.”

Morgott nodded, almost to himself. “Dost thou ever survey the coasts?”

His line of questioning was becoming more pointed—toward what, Mohg wasn’t certain, although an idea was starting to take form. “Routinely. It’s how we intercept Tarnished, before they traipse their way to the Hold.”

“They’re recruited by thee?”

“Would you prefer I send them your way?”

Morgott scowled.

“I thought so.”

Morgott redirected his stare to a different patch of cavernous sky—the facsimile of a nebula, coalesced in clouds of red dust. Like the alpenglow of a distant summit, suspended below the earth rather than above it.

“You despise the Tarnished.” It wasn’t a question. “What interest could you possibly have in them?”

“Not them,” Morgott corrected him. “Merely one.”

He lowered his head, and turned to look at Mohg.

“Their exodus is compelled by lost grace. All of the Tarnished were adjured to return—including the first. I had hoped,” said Morgott, haltingly, “that in all thy doings, thou mightst have whereabouts of our father.”

He wasn’t sure why Morgott was so determined to make him exhume every complicated emotion he had ever buried. But he was beginning to tire of it.

Mohg pinched the bridge of his nose. “No, I haven’t seen him.”

That was clearly the answer he had expected. Nevertheless, Morgott sighed.

“I had thought…” He frowned. “Surely, if any of them were to arise…”

The throne is not mine to take.

The snippet of conversation from earlier resurfaced.

“You wish to see him restored to the throne,” said Mohg. “Don’t you?”

Morgott looked as if he were debating whether or not to respond. When he finally did, it wasn’t what Mohg had expected. “I wish to see him.”

His lip curled, almost reflexively, and Mohg jerked his head back up toward the ceiling. He could see Morgott out of the corner of his eye, furrowing his brow.

It was almost deafeningly loud amidst the quiet: “Dost thou repudiate him, too?”

There had been a time when Mohg already knew his answer.

Perhaps, once, he had paced the length of the Shunning Grounds like a caged animal. Lashing out at anything that dared approach. Consumed by inexhaustible rage as he clung to their father’s parting words, his promise to one day return from exile, and come back for them. Only to never see him again.

Perhaps, once, he had knelt in a ring of flickering candles. His brow anointed with blood, the ground before him smeared in dark crimson, as he had beseeched his new mother. Cried out until his voice was hoarse. Had asked his patron what more could be done—what more he could give—to erase the pain. Only to be chided. Scars, she told him, could not be erased.

Perhaps, once, he had scanned the horizon. Had convinced himself that he wasn’t looking for the silhouette of a lion, astride the shoulders of a man.

Perhaps, once, if had he been asked the same of his brother, his answer would have been no different.

Mohg closed his eye. “No,” he sighed, and the effort left him feeling drained, “I do not.” He opened it again, taking in the stars and their bright, otherworldly glow. “Should one of my scouts find evidence of his arrival, I’ll investigate. I will ensure no harm comes to him, insofar as I am able.”

The relief in Morgott’s face was replaced by confusion. “‘As thou art able’?”

“It isn’t just scarlet rot that inhibits our movements. Inducting the Tarnished does nothing to ward off those that would hunt them.” The frown he wore was identical to his brother’s—vexed by things beyond his control. “I’ve lost scouts to Godrick’s hunting parties. To riders, as well.”

Morgott’s reply was uneasy. “…What manner of riders?”

“Knights, of some kind.” He recalled the description from Ansbach’s latest report. “Wearing black armor, and carried by horses that don shrouds. They patrol most of the major roads.”

“They are called the Night’s Cavalry,” said Morgott, suddenly. “And they serve me.”

Mohg tore his gaze from the sky. “They serve you?”

Shame was as much a permanent fixture as his white hair. Yet Mohg couldn’t ever recall seeing it directed at him. “They are spirits, rejected by the tree, bound into my service through oath. I granted them new purpose when they died.” Unmistakably, he winced. “As a contingency measure…against the Tarnished.”

At a loss for words, Mohg could only give a noncommittal, “Ah.”

They stared at each other.

“I did not think they—that thy ranks would be—” He cut himself off with a frustrated noise and shook his head, before his shoulders dropped, settling into acquiescence. “What reparations can I make to thee, for my transgressions?”

It was such an absurd notion that Mohg actually thought he had misheard. But, no, he knew he hadn’t. His horns had taken his eye, not his ears.

Having the king of Leyndell in his debt would be useful, Mohg thought, in a voice that suspiciously resembled Varré's. It could be extorted—leveraged—to incredible effect.

Almost as soon as the thought entered his mind, it was discarded. Debt was no longer a prize worth coveting. It complicates things, Ansbach would have told him. And Mohg couldn’t have this—whatever this tentative truce between him and his brother actually was—if it was predicated on transactions.

“None, that I wouldn’t then need to reciprocate.” Mohg shrugged, broad shoulders shifting under the black garment. “My servants have killed a number of Leyndell soldiers. Of course,” he added, “I hadn’t realized at the time they were yours.”

He extended a hand.

“Consider the ledger balanced?”

Morgott eyed the appendage, letting it hang between them—before, finally, stepping forward. Their hands clasped.

“We’ve an accord,” he murmured.

His palm was warm and calloused. Leathery, even. Years’ worth of self-neglect, no doubt. It startled Mohg how achingly familiar the touch felt.

Mohg almost regretted letting go.

He wondered, as Morgott watched his hand return to his side, if he didn’t feel the same.

“My cavalry only rideth between dusk and dawn,” Morgott said. “So long as thy scouts avoid the roads betwixt then, they will be safe.”

“I’ll bear that in mind.”

Morgott opened his mouth again, only to close it. His tail swept behind him, and without warning, he brushed past Mohg and made his way toward the gatehouse.

“I’ve overstayed my welcome, unannounced as it was,” he said, rather abruptly. “Where is thy war surgeon? Lurking somewhere nearby, I assume? Let me find him, and I’ll see myself out.”

He only made it eight steps before Mohg capitulated.

“Morgott,” he called after him. “Wait.”

His brother glanced over his shoulder, his look of puzzlement morphing into confusion as Mohg caught up, and pressed the medal into his hand. “Take this.”

Morgott lifted the crest to eye-level. It was the color of rusted iron, emblazoned with a trident in its center. “What is it?”

“My aegis,” he said, ignoring the startled look he received. “There are enchantments upon it. Should you need to reach me, it will bring you here.”

Morgott thumbed over the intricate design. A nacreous sheen rippled across its surface—the only evidence of latent spellwork. “I’ve naught to give thee in return.”

“Oh, that won’t be necessary. I have my own methods for going as I wish.”

Morgott’s brows shot up. No doubt the aloof drawl had sparked recognition—the same one that, in their adolescence, had threatened to turn his hair prematurely gray; a foreboding sound, of amusement at the expense of his brother’s peace of mind. A moment passed, and Morgott let out an exasperated snort. It was almost fond. “I don’t want to know.”

“No,” he agreed, and his face split into a jagged grin, “you rather don’t.”

Mohg might have missed the brief, furtive smile, if he hadn’t been looking for it.

#elden ring#elden ring fic#elden ring thought dump#morgott the omen king#mohg lord of blood#white mask varre#pureblood knight ansbach#my posts#i speak#as always my fics are available on AO3 (including this one)#stress writing to cope with The Horrors™#onion headline: estranged brothers proceed to bicker within seconds of being reunited

53 notes

·

View notes