#old norse poetry

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Also, because I’m me:

Yes, I will go back and count stanzas and syllables in Murtagh’s poetry to see which meters Paolini is using, because I am That Bitch and will never not Old Norse-ify things on main whenever possible

#Murtagh#old norse poetry#that first one felt so much like sonatorrek tbqh#which if I remember correctly is in a form of altered fornyrðislag that I suuuper can’t remember the name of

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Scandinavia - Old Norse Poetry - Structure and advice on writing imitations

(Some of this will be copy-pasted from my previous post on Old Norse literature and oral tradition)

OLD NORSE POETIC FORMS

Old Norse poetry utilizes a modified form of alliterative verse. In simpler terms, the metrical structure is not necessarily based on the last syllables of a line or phrase rhyming...

Ex: (lines from William Shakespeare’s Venus and Adonis) “And so in spite of death thou dost survive / In that thy likeness still is left alive”

... the structure relies on the repetition of multiple initial consonants in a line or phrase.

Ex: (from the Hávamál of the Codex Regius) Deyr fé // deyja frændr

SKALDIC POETRY

Primarily documented in sagas, skaldic poetry is usually about history, particularly the celebrated actions of kings, jarls, and some heroes. It typically includes little dialogue and recounted battles in dialogue. It has more complex styles, especially using dróttkvætt and many kennings.

DRÓTTKVÆTT (“courtly metre”)

- Adds internal rhymes and assonance (repetition of both consonants AND vowels) beyond the normal alliterative verse

- The stanza had 8 lines, each line usually having 3 lifts (heavily stressed syllables) and almost always 6 syllables

- The stress patterns tends to be trochaic (stressed, unstressed), with at least the last 2 syllables of a line being a trochee (usually...)

- In odd-numbered lines (first line, third line, etc.): 2 of the stressed syllables alliterate with one another; two of the stressed syllables share partial rhyme of consonants with dissimilar vowels (ex: hat and bet; touching and orchard)

- In even-numbered lines (second line, fourth line, etc.): the first stressed syllable must alliterate with the alliterative stressed syllables of the previous line (an odd-numbered line); two of the stressed syllables rhyme (ex: hat and cat; torching and orchard)

These requirements are SO difficult that oftentimes poets would mash together two separate lines of writing in order to meet the structure. It’s really hard to explain, so read the wikipedia link here for more info.

KENNINGS

Kennings are figures of speech strongly associated with Old Norse-Icelandic and Old English poetry. It is a “type of circumlocution, a compound employs figurative language in place of a more concrete single-word noun” (source).

Now, when I first read that, I had zero clue what the hell that meant. But this is my current understanding: a poetic device where you dance around using a single noun by describing it with other words. It is similar to the poetic device of parallelism.

- “bane of wood” = fire (Old Norse kenning)

- “sleep of the sword” = death (Old English kenning)

- Drahtesel = “wire-donkey” = bicycle (modern German kenning)

- Stubentiger = “parlour-tiger” = house cat (modern German kenning)

- Genesis 49:11 “blood of grapes” = wine

- Job 15:14 “born of woman” = man

A beautiful resource for translated kennings is this article here from the HuffPost’s Harold Anthony Lloyd.

SIMPLE KENNINGS

Simple kennings would be used in both Eddic and Skaldic poetry.

The usual forms are a genitive phrase (ex: the wave’s horse = ship) or a compound word (sea-steed = ship). There is usually a base-word and a determinant.

The determinant may be a noun used uninflected as the first element in a compound word, with the base-word being the second element of the compound word.

OR the determinant may be a noun in the genitive case placed before or after the base-word, either directly or separated from the base-word by intervening words. The base-words in the above examples are “horse” and “steed”, while the determinants are “waves” and “sea”.

The unstated noun which the kenning refers to is called its “referent”, in the example a bit above: ship.

COMPLEX KENNINGS

More complex kennings are really only used in skaldic poetry.

In these, the determinant and sometimes the base-word are themselves made up of kennings. A matryoshka doll of kennings, if you will.

Ex: “feeder of war-gull (bird)” = “feeder of raven” = “warrior” (referring to how warriors kill people and leave their corpses for birds to eat)

The longest kenning in Skaldic poetry belongs to Þórðr Sjáreksson’s Hafgerðinga where he writes “fire-brandisher of blizzard of ogress of protection-moon of steed of boat-shed”, which means “warrior” (source).

EDDIC POETRY

Eddic poetry is usually about mythology, ethics, and heroes, and is narrative (where both the narrator and the characters are speaking). They use simpler structures, like fornyrðislag, ljóðaháttr, and málaháttr, and use kennings more sparingly.

FORNYRÐISLAG (”old story metre”)

- Each line tends to be a whole phrase or sentence (or end-stopped), where a sentence won’t “run over” and onto the next line (or enjambment).

Ex: End-stopped, from William Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet “A glooming peace this morning with it brings. / The sun for sorrow will not show his head.”

Ex: Enjambed, from T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land “ Winter kept us warm, covering / Earth in forgetful snow, feeding / A little life with dried tubers.”

- Each verse is split into 2 to 8 (or more) stanzas.

Ex: from Waking of Angantyr (structure provided by wikipedia)

- There are 2 lifts per half line, usually with two or three unstressed syllables. At least 2 (but usually 3) lifts will alliterate, always including the main stave (the first life of the second half-line). This means there are usually between 4 and 5 syllables per half line, and therefore between 8 and 10 syllables per full line (but it can vary).

MÁLAHÁTTR (“conversational style”)

- Similar to fornyrðislag, but there are more syllables in a line.

- It adds an unstressed syllable to each half-line, making the typical 2-3 per half-line and 4-6 per line into 3-4 per half-line and upwards of 6 unstressed syllables per line

LJÓÐAHÁTTR (“song” or “ballad metre”)

- Usually made up of stanzas with four lines each

- Odd numbered lines were usually standard lines of alliterative verse with 4 lifts and 2 or 3 alliterations. It was cut in half with a “cæsura” or “//”, which indicates the end of one phrase and the beginning of another.

- Even numbered lines had 3 lifts and 2 alliterations, with no cæsura.

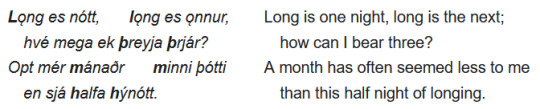

Ex: from Freyr’s lament in Skírnismál (structure provided by wikipedia)

WRITING IMITATION

When writing an imitation of Eddic and Skaldic poetry, there are many workarounds if you don’t want to jump through these hoops.

Personally, I am putting forward my imitation as a “translation” of an Old Norse text so I don’t need as much concern for alliteration, rhymes, and exact syllables.

But I enjoy having a similar feel to the original poems, so I do try to put in some alliteration for words that are of Norse/Germanic origin and keep a similar syllable count.

Posted: 2023 May 29

Edited last: 2023 May 30

Writing and research by: Rainy

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

This is fascinating! I wanna give this a try!

A galdralag on galdralag:

So, for homework for my Seiðr apprenticeship, I was assigned to write a poem in galdralag, the traditional norse poetic meter used for spellcraft and speaking of spellcraft.

i Grasp at Galdralag,

Great meter, Gargantuan power.

Always An Alliteration here.

Note Now which lines alliterate,

Know Now these six lines are ljoðahattr.

Another Alliteration ends ljoðahattr.

Additional Alliteration Adds power.

Great Galdralag Always Alliterates Although Adding Eighth lines are Optional.

So as this galdralag I wrote explains, galdralag is an alliterative poetic meter focused on parallelism. Also, as the poem suggests, the first part of any galdralag is actually the format called ljoðahattr, another poetic meter used by the old norse. The first two lines alliterate with each other as much as possible, the more the better (my example is basic and in my native English), followed by a third line which alliterates within itself. Then, two more lines alliterate with each other, followed by another line of the same type as the third line. Then another (now seventh) line of the same type as the third and sixth line, followed by an eighth of the same type. You could experiment with adding more lines, of the same type as the third and sixth through eighth, although I’m unaware of examples of this. Galdralag can be found in the Rune song portion of the Havamal, the majority of the Havamal being written in the previously mentioned poetic meter of Ljoðahattr.

Galdralag can also be broken down in this way, to aid in understanding the meter’s structure:

1: always alliterates with 2

2: always alliterates with 1

3: always alliterates with itself

4: always alliterates with 5

5: always alliterates with 4

6: always alliterates with itself

7: always alliterates with itself

8: always alliterates with itself

There are also examples of Ljoðahattr consisting of just the first three lines, and becoming galdralag when adding another line of the same type as the third, for a shorter poetic verse.

Feel free to message me if you have any questions. I hope to see the Norse art of Galdralag spread and evolve, and I hope my English speaking audience finds some inspiration to work with this style of both traditional spellcraft and poetry (Galdralag is both). Of course, I likely won’t reveal all I know about Galdralag as it would be very unwizard of me to reveal ALL my secrets, but I hope this is helpful or inspirational to some of you.

#old norse#old norse poetry#poetic meter#history#spellwork#seidr#seiðr#heathen#heathenry#galdralag#spellcraft#queued

90 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hail to the Old Gods;

The ancient ones, Deities of forest, mountain, and sea, for whom my ancestors poured from their ram horns.

Hail to the god of emotions, who teaches us when to embrace chaos and when to refrain for the moment.

Hail to the goddess of seiðr, who holds the key of divination in the waves of her golden hair trailing down her breasts.

Hail to the god of strength, guardian of the deer herds, who teaches me when to cry for help and when to stand and gore. Hail to the Allfather, whose unconventional wisdom hurt me greatly in the moment, but saved my soul from perpetual insanity through the binding of runes.

(Thank you all for everything)

Hail to the Old Gods.

#poetscommunity#writers and poets#poems on tumblr#original poem#writers on tumblr#writing#writerscommunity#writeblr#poems and poetry#poets on tumblr#poem#poetry#pagan#norse#norse pagan#norse paganism#heathen#heathenry#gratitude#devotional#paganism#paganblr#asgard#pagan worship#deity worship#the old ways#landscape#mountains#i miss home#tennessee

158 notes

·

View notes

Text

ᛆᚱ ᚢᛆᚱ ᛆᛚᛑᛆ ᚦᛆᚱ ᛂᚱ ᚤᛘᛁᚱ ᛒᚤᚵᚧᛁ ᚮᚱ ᚤᛘᛁᛋ ᚼᚮᛚᛑᛁ ᚢᛆᚱ ᛁᚰᚱᚧ ᚢᛘ ᛋᚴᚰᛔᚢᚧ ᛂᚿ ᚮᚱ ᛋᚢᛅᛁᛐᛆ ᛋᛅᚱ ᛒᛁᚰᚱᚵ ᚮᚱ ᛒᛅᛁᚿᚢᛘ ᛒᛆᚧᛘᚱ ᚮᚱ ᚼᛆᚱᛁ ᛂᚿ ᚮᚱ ᚼᚰᚢᛋᛁ ᚼᛁᛘᛁᚿᚿ

Ár var alda, þar er Ymir bygði; ór Ymis holdi var jǫrð um skǫpuð, en ór sveita sær, bjǫrg ór beinum, baðmr ór hári, en ór hausi himinn.

The age was old when Ymir (Twin) lived; from Ymir’s flesh the earth was formed, and from his sweat (i.e. blood) the sea, boulders from his bones, trees from his hair, and from his skull the sky.

First two lines are from Vǫluspá 3, the rest is from Grímnismál 40

(sang by Gealdýr)

#old norse#norse#heathen#heathenry#gealdyr#skald#skaldic poetry#voluspa#cosmology#runes#runic#futhark

76 notes

·

View notes

Text

Arúnd dem fellar,

thveran dem vaer,

äthr keolar abr arget

ek’ eom kaustaën.

Ek’ né kenne hvarfra,

ed hvat ek’ eithí,

anan harmr nuanen nun

unin hjarta iet líf.

Over the mountains,

across the sea,

on ships of silver

I am come.

I know not whence,

or what I left behind,

only beautiful sorrow now

lives in my heart.

(part of an ancient elvish song about longing for Alalëa)

#- mod Lights#eragon#inheritance cycle#poetry#i mostly drew on Paolini's own notes on the ancient language that are on his website#and filled in the gaps with modified Old English and Old Norse

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vin sínum skal maðr vinr vera, ok gjalda gjöf við gjöf. Hlátr við hlátri skyli hölðar taka, en lausung við lygi.

'To his friend, a man should be a friend, and return a gift for a gift. Men ought to accept Laughter with laughter, but faithlessness with falsehood.'

-- Hávamál 42

#old norse#norrønt#hávamál#havamal#odin#óðinn#wisdom#quote#poetry#poetic edda#bits and pieces#my work#translation#language

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tonight's recitation of Völuspá has been canceled due to forseen circumstances.

#volva#völva#voluspa#völuspa#völuspá#old norse#norse poetry#skaldic poetry#poetic edda#norse mythology#viking mythology#scandinavian mythology#paganism#vikings#asatru#viking#viking history#norse history#norse humor#norse heathen

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

This is technically my Second Hymn to Nótt, but I think The Dreamer's Hymn to Nótt is a better title

#Nótt#night#dream god#dream goddess#unlight#masker#joy-of-sleep#Norse gods#Norse Mythology#Norse paganism#norse Polytheism#Old Norse#heathen#heathenry#north sea poet#poetry#my poetry#nico solheim-davidson

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

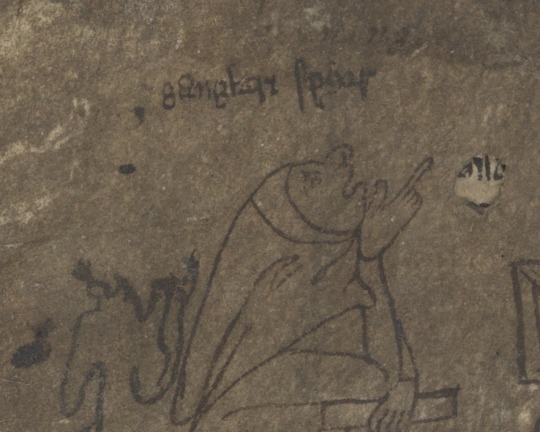

Episode 13: Maja Bäckvall on the Prose Edda, funky Norse illustrations, and the MCU Thor movies

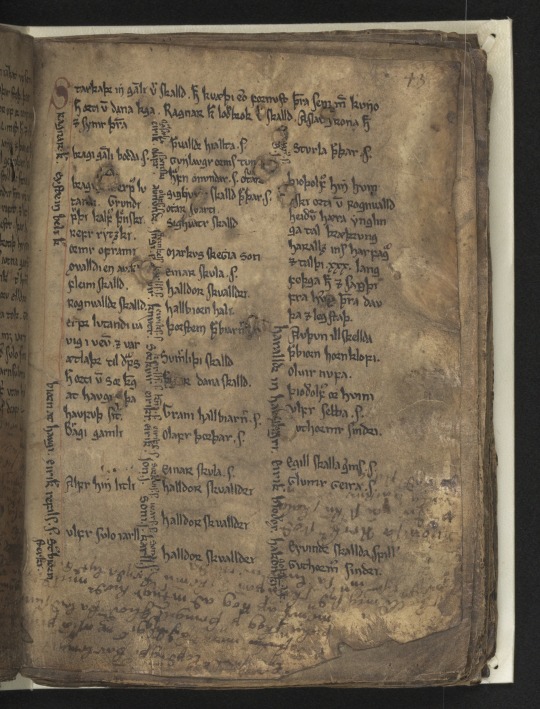

Uppsala-Eddan, p. 47, Skaldic lists with figures dancing (?) in the margins.

In Episode 13 of Inside My Favorite Manuscript, Lindsey and Dot chat with Maja Bäckvall about Uppsala University DG 11, one of four surviving copies of the so-called Prose Edda written by Snorri Sturluson in the 1220s. The Uppsala copy was made in Iceland in the first quarter of the 14th century. We talk about what exactly the Prose Edda is, how this copy differs from the others, we look at the illustrations, and we also make Maja talk about THOR (the movies from the Marvel Cinematic Universe).

Listen here, or wherever you find your podcasts.

Below the cut are more page images and links to the shows and books we mention during our conversation.

Uppsala-Eddan, Uppsala University Library DG 11 (digitized on the Alvin portal)

Uppsala-Eddan, p. 50

Close-up on p. 50 - see the man's name written over his head (also there's a little hole in the parchment on the right, with the text from the page before visible through it)

Another close-up on p. 50, where a later artist (or wishes-to-be-an-artist) is trying their hand at drawing their own king.

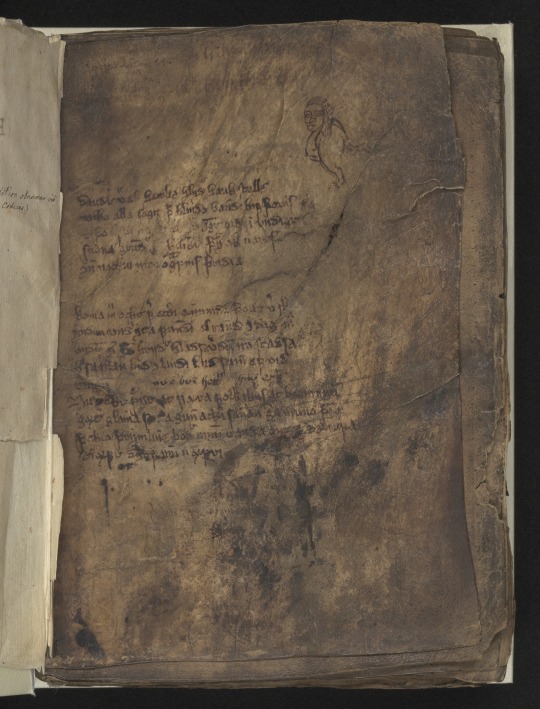

Uppsala-Eddan, p. 49 (the other side of p. 50), with illustration of a woman added to the manuscript in the 15th century:

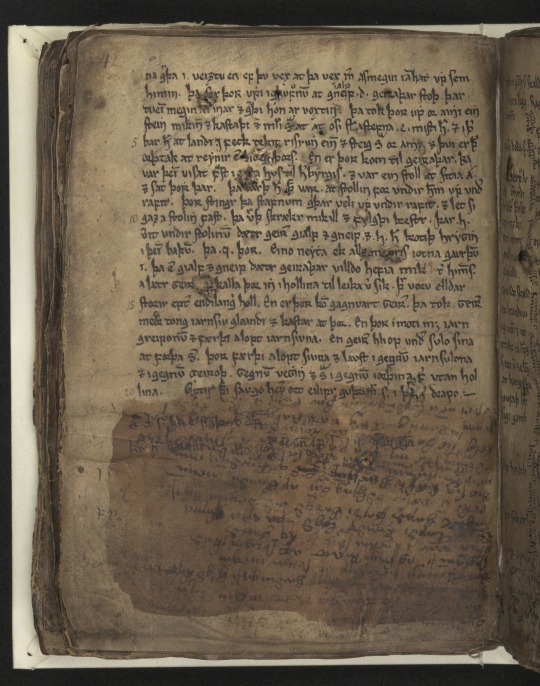

Uppsala-Eddan, p. 47, Skaldic lists with figures dancing (?) in the margins.

Uppsala-Eddan, p. 42. The bottom portion of the page was left blank and filled in later, with text written upside-down. The staining may be from a chemical reagent used to bring out faded ink.

Uppsala-Eddan, p. 42, a close-up of the bottom of the page, reversed so the text is right-side-up

Uppsala-Eddan, p. 43, where the upside-down text continues in the bottom margin.

Uppsala-Eddan, p. 43, bottom margin reversed and cropped

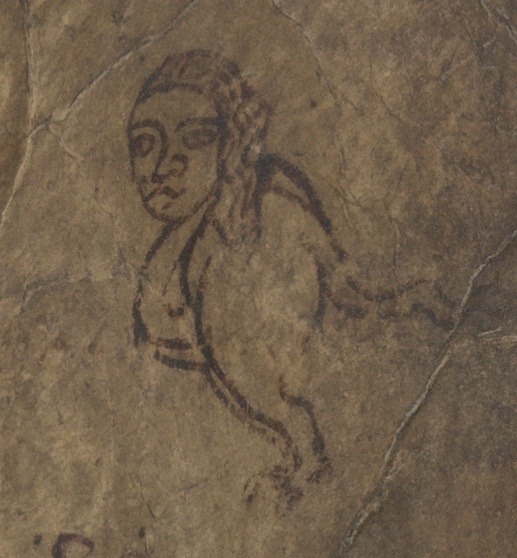

Uppsala-Eddan, front flyleaf recto (original parchment with text and illustration added later)

Uppsala-Eddan, p. 1, close-up of "sphinx-like creature" (I'm not really sure what that is!)

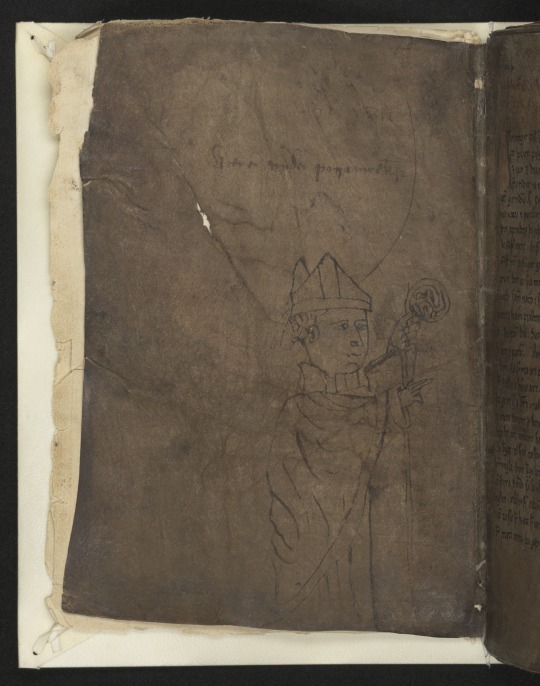

Uppsala-Eddan, front flyleaf verso with Bishop drawn in after the original text was written, probably at the same time as the text written on the recto side of the leaf

Uppsala-Eddan, p. 1, the first page of the Edda text.

Uppsala-Eddan, p. 1, a close-up at the text in red at the top of the page, which names the text as Edda and the author as Snorri Sturluson (both underlined)

Uppsala-Eddan, p. 1, close-up of the initial, which is quite fancy for an Icelandic manuscript

Thor movies in the MCU (IMDB)

Vikings TV show (IMDB)

The Northman (Dir. Robert Eggers, 2022) (IMDB)

πορφυρογέννητη, a fan fiction by neonheartbeat (posted with permission from the author)

Travel Light by Naomi Mitchison (book on Goodreads)

#medieval#manuscript#podcast#old norse#icelandic#icelandic manuscript#snorri sturluson#prose edda#skaldic poetry#vikings#thor#imfm#imfmpod

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Scandinavia - Old Norse Poetry - Literature and Oral Tradition

The following post describes the literature and oral traditions of Scandinavian peoples during the times of the Vikings. I describe the difference between skaldic and eddic poetry and define kennings.

A later post will have my resources and advice on writing imitations of both types of poetry. (Find it here!)

There are few primary sources of Scandinavian history and stories from the times of “Vikings”, or from the late 8th century to the late 11th century. There are artifacts with runic writing, but these are short and few in number. Most of the documents about Scandinavians written during their time are from outside sources (and often they are biased against the Norsemen) (source).

In the late 11th and early 12th centuries, Christianity and its method of writing in Latin was introduced to Scandinavia. After Latin was introduced, the oral traditions began to be recorded by a variety of authors, though the most notable is Snorri Sturluson (who compiled the Prose Edda) (source).

The most important to study of the Old Norse languages and the mythos of these peoples are the Poetic Edda and the Prose Edda.

“The Poetic Edda is the modern name for an untitled collection of Old Norse anonymous narrative poems” (source). There are several versions, and the most notable is an Icelandic text called Codex Regius from the 1270s CE which has 31 poems. These poems were not written by any one poet, but were collected and recorded from oral tradition. The exact age of these poems are unknown, but are considered to be the only direct records of Norsemen from their times.

The Prose Edda “is an Old Norse textbooks written in Iceland during the 13th century”. Its major and most well known contributor is Snorri Sturluson, a scholar and historian. The contents of the book are accounts of Old Norse mythology. Many of its sources are the same poems documented in the Poetic Edda.

Now, more on Old Norse poetry. For the most part, history and stories of the time of Vikings were passed down orally in two types of poetry.

Skaldic poetry (named for their creators: skald, or court poets) mostly regarded history and celebrated kings and jarls. It typically included little dialogue and recounted battles in detail. In comparison to Eddic poetry, Skaldic verse tends to be more complex in style and uses dróttkvætt. It also uses more kennings. While not proven, there is some speculation that skald accompanied their verse with a harp or lyre (source). It is mostly recorded in sagas.

Eddic poetry (named for the book they are compiled in: the Poetic Edda) is narrative, where there is both a narrator and characters speaking. They are characterized by their focus on mythology, ethics, and heroes, as well as a simpler way of verse (using fornyrðislag, ljóðaháttr, and málaháttr). It uses kennings, but less extensively than Skaldic poetry. It is mostly dialogue (source 1, source 2).

Kennings are figures of speech strongly associated with Old Norse-Icelandic and Old English poetry. It is a “type of circumlocution, a compound employs figurative language in place of a more concrete single-word noun” (source).

Now, when I first read that, I had zero clue what the hell that meant. But this is my current understanding: a poetic device where you dance around using a single noun by describing it with other words. It is similar to the poetic device of parallelism.

- “bane of wood” = fire (Old Norse kenning)

- “sleep of the sword” = death (Old English kenning)

- Drahtesel = “wire-donkey” = bicycle (modern German kenning)

- Stubentiger = “parlour-tiger” = house cat (modern German kenning)

- Genesis 49:11 “blood of grapes” = wine

- Job 15:14 “born of woman” = man

In a later post I will go into further details of the exact format of the two types of poetry. But it will be in the context of writing imitations.

Posted: 2023 May 29

Last edited: 2023 May 30

Writing and research by: Rainy

#vikings#poetic edda#prose edda#snorri sturluson#viking poetry#skald#skaldic poetry#kennings#kenning#eddic poetry#edda#old norse#old norse poetry#norse poetry

0 notes

Text

My queen i had sought ,

Or at least so i thought

But she let my heart rot .

I wanted to be her Thor ,

For she was my Sif

But oh warriors of Valhalla, little did we know, that her love, was just a whiff !

Being mine, she'd always whine

Wait, was she ever mine ?

I wasn't the only one with whom she was snug

Oh gosh it broke my smug !

Turns out, the one i thought was my queen was really just a dream .

You know, the dreams which are more than just dreams

The ones which grow within you like a river and it's streams.

The ones which no matter how dark they are, light your life with gleams.

But thing is, no matter how lovely a dream is, if it's a nightmare, that's what it'll continue to be

But it's the nightmare i everyday want to see !

#relationships#poetry#sad boi hours#sad but true#im hurtin#hurtful#hurtquotes#poemsworld#poetsandwriters#poems and quotes#my poem#norsemen#old norse#valhallaedit

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hail, Spirit of the Mountain, Hail, Landvættir!

Hail to you, Spirit of the Mountain lands, Although I am from Appalachia, you welcome me as your own kin and Daughter.

Hail to you, Landvættir: the Great Deer Herds, The Guardians of these mountains and woods, Keepers of the Ancient Wisdom and tales.

May I recognize your presence all times, May I always listen when you speak up, May you be blessed in all your endeavors.

Hail, Spirit of the Mountain, Hail, Landvættir!

#poetscommunity#writers and poets#poems on tumblr#original poem#heathen#writers on tumblr#writing#writerscommunity#writeblr#poems and poetry#poets on tumblr#poem#poetry#pagan#norse#norse paganism#paganism#pagan worship#deity worship#land spirits#the old ways#landscape#mountains#garden of the gods#southern illinois#i miss home

58 notes

·

View notes

Photo

He that lavished rings in largesse, When the fight's red rain-drops fell, Bright of face, with heart-strings hardy, Hogni's father met his fate; Then his brow with helmet shrouding, Bearing battle-shield, he spake, "I will die the prop of battle, Sooner die than yield an inch. Yes, sooner die than yield an inch.”

Brennu-Njáls Saga, chapter 77 - Gunnar Sings a Song Dead George W. DaSent’s translation (1861)

#god of war ragnarok#draugr#virtual photography#my screenshots#gunnar at this point in the story was a draugr#many draugr in germanic sagas and poetry were sentient and could speak#gunnar in this instance could sing#the quotation is his song#what's interesting about many of these sagas is that they are sometimes from the early christian period of old germanic culture#and so you'll sometimes see christian terms evoked alongside norse paganism

1 note

·

View note

Text

poetry

#poetry#poem#old norse#norse#translation#sun#moon#cosmos#stars#ancient wisdom#thinking about how all these#celestial beings#are so#insecure#and lost#but we mortals#with a little life#live with purpose#fearlessly#because we know we’ll be gone#in the end

0 notes

Text

Vesall maðr ok illa skapi hlær at hvívetna. Hittki hann veit er hann vita þyrfti: at hann er-at vamma vanr.

'A wretched man and the undisciplined ridicules everything. He has not learned the lesson which he needs: he is not without flaw either.'

Hávamál 22.

#old norse#norrønt#hávamál#havamal#odin#óðinn#wisdom#quote#poetry#poetic edda#bits and pieces#my work#translation#language

4 notes

·

View notes