#neckers

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The Witcher by Pao Cruz

350 notes

·

View notes

Text

In 1978, to impress his girlfriend, Richard Branson showed interest in Necker Island, listed at $6 million. He initially offered $100,000, which was declined. A year later, the owner accepted $180,000, and Branson purchased the island.

#Richard Branson#Necker Island#Virgin Group#real estate#British Virgin Islands#luxury resort#entrepreneurship#business history#1978#Joan Templeman

84 notes

·

View notes

Text

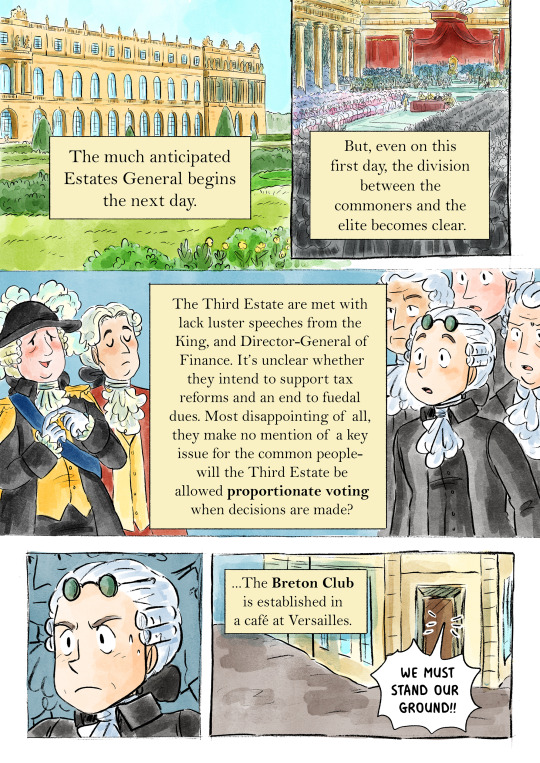

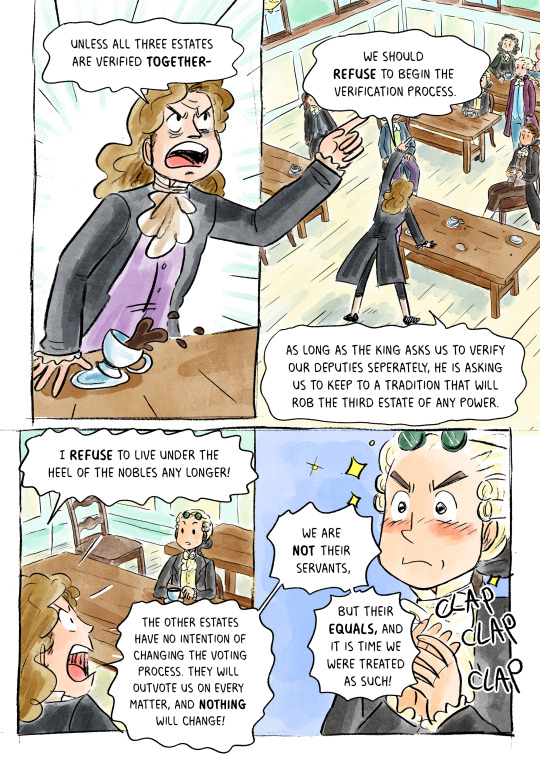

Incorruptible chap 2 pt 5

I'd like to think Robespierre was intensely excited and inspired during those early days in the Breton Club (I remember reading a letter that suggested as such)

#incorruptiblecomic#I feel bad for showing Necker in a bad light since he really helped in the build up to Frev with his bold moves/popularity#but also it sounds like he really didnt read the room with his opening speech at the Estates General lol#Also me chanelling personal anger at current political situations into an angry Breton lol#french revolution#robespierre art#robespierre#frev#webcomic#comic#webtoon#historical fiction#maximilien robespierre#frev art#frev comic

137 notes

·

View notes

Text

double bwomp/peace stripe-inversion style: GO!

#me#trans#transfemme#transfem#oh hey look my apartment interior kinda has a necker-cube type illusion to it#anyway...

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

#androgyne#transgender#andrógine#andróginx#trans#nonbinary#gender symbols#no binarie#androginia#androgynous#flags#género#gender#pride month#arca#símbolos#bandera#transgénero#transexual#transsexual#triangles#necker cube#practical androgyny#the kybalion

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

'The War of the Districts, or the Flight of Marat…'

Part 1 (of 5)

Some years ago I photographed a fantastic, satirical poem from a compendium of French Revolutionary verse in the BnF (réserve). It’s been gathering virtual dust ever since. But no more! It’s a witty take on a key moment from early in the Revolution, when the Paris authorities pitted themselves against the radical Cordeliers district (under Danton’s leadership). With help from @anotherhumaninthisworld (merci encore!), we managed to produce a rough translation, which I revised, added some footnotes (to clarify the more obscure references) and added this brief intro to put it in context. While the translation is a literal one, I’ve tried to preserve some of the rhyming spirit of the original where possible. So boil the kettle, get a brew on and settle down to an epic account of Maranton vs Neckerette…

In the early hours of 22 January 1790, General Lafayette, commander of the National Guard, authorized a large military force to arrest the radical journalist Jean-Paul Marat, following a request from Sylvain Bailly, the Mayor of Paris, to provide the Chatelet with sufficient armed force [“main-forte’] to enable its bailiff to enforce the warrant.[1] Bailly’s request was in response to the outrage caused by the publication, four days earlier, of Marat’s 78-page Denunciation of the finance minister, Jacques Necker.[2] Marat had moved into the district the Cordeliers district in December to seek its declared protection against arbitrary prosecution.

His best-selling pamphlet denounced Necker – probably the most popular man in France after the King in July 1789 – of covertly supporting the Ancien Régime and working to undermine the Revolution. His accusations included plotting to dissolve the National Assembly and remove the royal family to Metz on 5 October, colluding in grain hoarding and speculation, and generally compromising the King’s honour. The charges were intended to reveal a cumulative (and damning) pattern of behaviour since Necker’s reappointment in July 1788, and again in July 1789. Bearing his Rousseau-derived epigraph, Vitam impendere vero (‘To devote one’s life to the truth’) – now used as a kind of personal branding, Marat adopted the role of “avocat” to ‘try’ Necker before the court of public opinion.[3] Its general tone came in the context of a wider distrust of international capitalism, with which Necker was closely associated, and which appearted to violate many traditional values.[4] For those interested in the nitty gritty, here’s a footnote explaining why Marat had completely lost faith in Necker.[5]

It caused such a sensation that the first print-run sold out in 24 hours. Most of the radical press hailed Marat’s audacity in challenging Necker’s ‘virtuous’ reputation, while providing invaluable publicity for his pamphlet. The legal pursuit of Marat was largely prompted by the rigid adherence of the Chatelet to Ancien Régime values against the offence of libel (attacking a person in print).[6] I suspect that Marat was hoping a high-profile campaign against Necker would help to establish his name in the public eye by provoking a strong response. However, this was one of the rare occasions when Necker delegated his defence to ‘hired’ pens, providing Marat with valuable extra publicity.

If libel was the main reason for going after Marat, the impetus for pursuit was further motivated by wider political concerns over the extreme volatility that had gripped Paris since mid-December. After pre-emptive popular action in July and October against perceived counter-revolutionary plotting, a new wave of similar rumours was seen by many as a signal that the thermometer was about to explode again. The arrest of the marquis de Favras on Christmas Eve, for allegedly conspiring to raise a force to whisk the King away to safety, assassinate revolutionary leaders, and put his master, Monsieur (the King’s middle brother) on the throne as regent, only served to intensify popular fears. This, combined with the continuing failure to prosecute any royal officers, including the baron de Besenval, commander of the King’s troops around Paris during 12-14 July ��� who would be acquitted on 29 January for ‘counter-revolutionary’ actions – led to large crowds milling daily outside the Palais de Justice, as the legal action against both men dragged on through January.[7] On the 7th January, a bread riot in Versailles led to the declaration of martial law; on the 10th, a large march on the Hotel de Ville had been stopped in its tracks by Lafayette; on the 11th, there was an unruly 10,000-strong demonstration, screaming death-threats against defendants and judges, in the worst disturbances to public order since the October Days march on Versailles (and the most severe for another year); and on the 13th, tensions were further exacerbated by a threatened mutiny amongst disgruntled National Guards, which was efficiently snuffed out by Lafayette.[8] As a result, Marat’s Denunciation, and earlier attacks on Boucher d’Argis, the trial’s presiding judge, were seen as encouraging a dangerous distrust towards the authorities. Hence the pressing need to set an example of him.

So much for the background. Do we know anything about the poem’s authorship? it appeared around the same time (July/August) as Louis de Champcenetz & Antoine Rivarol’s sarcastic Petit dictionnaire des grands hommes de la Révolution, par un citoyen actif, ci-devant Rien(July/Aug 1790), which featured a brief entry on how Marat had eluded the attention of 5000 National Guardsmen and hid in southern France, disguised as a deserter. These figures would become the subject of wildly varying estimates, depending on who was reporting the ‘Affair’ – all, technically, primary sources! The higher the number of soldiers, the greater the degree of ridicule.[9] Contemporary accounts ranged from 400 to 12,000, although the latter exaggerated figure, included the extensive reserves positioned outside the district.[10] Since the poem also suggests around 5000 men, this similarity of numbers, alongside other literary and satirical clues, such as both men’s involvement in the Actes des apôtres, and the Petit dictionnaire’s targeting of Mme de Stael, suggest a possible common authorship.[11] While the poem took delight in mocking the ineptitude of the Paris Commune, the lattertook aim at the pretensions of the new class of revolutionary. While it is impossible to estimate the public reception of this poem, its cheap cover price of 15 sols suggests it was aimed at a wide audience. It was also republished under at least two different titles, sometimes alongside other counter-revolutionary pamphlets.[12]

Both act as important markers of Marat’s growing celebrity, just six months after the storming of the Bastille. A celebrity that reached far beyond the confines of his district (now section) and readership (which peaked at around 3000).[13] Marat was no longer being spoken of as just a malignant slanderer [“calomniateur”] but as the embodiment of a certain revolutionary stereotype. While he lacked the dedicated ‘fan base’ of a true celebrity, such as a Rousseau, a Voltaire or (even) a Necker, he did not lack for public curiosity, which was satisfied in his absence by a mediatized presence in pamphlets, poems, and the new lexicology.[14] For example, Marat would earn nine, separate entries in Pierre-Nicolas Chantreau’s Dictionnaire national et anecdotique (Aug 1790), the first in a series of dictionaries to capitalize on the Revolution’s fluid redefinition of language.

There seems little doubt that Marat’s Denunciation was intended to provoke the authorities into a strong reaction, and create “quelque sensation”, of which this mock-heroic poem forms one small part.[15] It would prove a pivotal moment in his revolutionary career, transforming him from the failed savant of 1789 to a vigorous symbol of press freedom and independence in 1790. Who knows what might have happened, if, as one royalist later remarked, the authorities had simply ignored this scribbling “dwarf”, whose only weapon was his pen.[16]

I'll post the 3 parts of the poem under #la fuite de Marat. enjoy!

[1] The Chatelet represented legal authority within Paris.

[2] Dénonciation faite au tribunal public par M. Marat, l’Ami du Peuple, contre M. Necker, premier ministre des finances (18 Jan 1790).

[3] The slogan was borrowed from Rousseau’s Lettre à d’Alembert, itself a misquote from Juvenal’s Satires (Vitam inpendere vero = ‘To sacrifice one’s life for the truth’).

[4] See Steven Kaplan’s excellent analysis of the mechanisms of famine plots and popular beliefs in the collusion between state and grain merchants. In part, this reflected a lack of transparency and poor PR in the state’s dealings with the public. During 1789-1790, when anxieties over grain supply were the main cause of rumours and popular tension, Necker made little effort to explain government policies. The Famine Plot Persuasion in Eighteenth-Century France (1982).

[5] As a rule, the King, and his ministers, did not consider the workings of government to be anyone’s business, and was not accountable to the public. However, in 1781, Necker undermined this precedent by publishing his Compte-rendu – a transparent snapshot of the royal finances – yet on his return in 1788, he failed to promote equivalent transparency over grain provision. In consequence, local administrators suffered from a lack of reliable information. Given the underlying food insecurity that followed the poor harvest of 1788, any rumours only unsettled the public. The most dramatic example of this came in the summer of 1789, when rumours of large-scale movements of brigands & beggars created the violent, rural panic known as ‘The Great Fear’. It was Necker’s continuing silence on these matters that lost Marat’s trust.

[6] Necker had a history of published interventions defending himself before the tribunal of public opinion, confessing that a thirst for gloire (renown) had motivated his continual courting of PO, then dismissing it as a fickle creature after it turned against him in 1790. eg Sur l’Administration de M. Necker (1791). For the best demonstration of continuity with Ancien Régime values after 1789, see Charles Walton, Policing Public Opinion in the French Revolution (2009).

[7] The erosion of Necker’s popularity began on 30 July after he asked the Commune to grant amnesty to all political prisoners, including Besenval.

[8] While the evidence was slight, Favras’ sentence to be hanged on 18 February made him a convenient scapegoat, allowing Besenval and Monsieur to escape further action. See Barry M. Shapiro, Revolutionary Justice in Paris, 1789-1790 (1993).

[9] The most likely figure appears 300-500. See Eugène Babut, ‘Une journée au district des Cordeliers etc’, in Revue historique (1903), p.287 (fn); Olivier Coquard, Marat (1996), pp.251-55; and Jacques de Cock & Charlotte Goetz, eds., Oeuvres Politiques de Marat (1995), i:130*-197*.

[10] For example, figures cited, included 400 in the Révolutions de Paris (16-23 Jan); 600 (with canon) in Mercure de France (30 Jan), repeated in a letter by Thomas Lindet (22 Jan); 2000 in a fake Ami du peuple (28 March); 3000 in Grande motion etc. (March); 4000 in Révolutions de France; 6000 (with canon) in Montjoie’s Histoire de la conjuration etc. (1796), pp.157-58; 10,000 in Parisian clair-voyant; 12,000 in Marat’s Appel à la Nation (Feb), repeated in AdP (23 July), reduced to 4000 in AdP (9 Feb 1791), but restored to 12,000 inPubliciste de la République française (24 April 1793).

[11] “Five to six large battalions/Followed by two squadrons” = approximately 5000 men (4800 + 300). A royalist journal edited and published by Jean-Gabriel Peltier, who also appears the most likely publisher of this poem.

[12] For example, Crimes envers le Roi, et envers la nation. Ou Confession patriotique (n.d., n.p,) & Le Triumvirat, ou messieurs Necker, Bailly et Lafayette, poème comique en trois chants (n.d., n.p.). Note the unusual use of ‘triumvirate’ at a time when this generally applied to the trio of Antoine Barnave, Alexandre Lameth and Adrien Duport.

[13] By the time the poem appeared, the Cordeliers district had been renamed section Théåtre-français, following the administrative redivision of Paris from 60 districts to 48 sections on 21 May 1790.

[14] For the growth of mediatized celebrity, see Antoine Lilti, Figures publiques (2014).

[15] As Marat explained in a footnote (‘Profession de foi’) at the end of his Denunciation, “Comme ma plume a fait quelque sensation, les ennemis publics qui sont les miens ont répandu dans le monde qu’elle était vendue…”

[16] Felix Galart de Montjoie, Histoire de la conjuration de Louis-Philippe-Joseph d’Orléans (1796), pp.157-58.

#la fuite de Marat#french revolution#poetry#counter-revolutionary#Jean-Paul Marat#Antoine de Rivarol#Louis de Champcenetz#1790#libel#Jacques Necker#General Lafayette#marat

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Le soleil a rendez-vous avec la lune…

#photography#original photography#original photography on tumblr#streetart#fresque murale#parisfrance#hôpital Necker

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

a fun fact about me is i have my list of historical figures i am Not Normal about but i also have another, secreter list of historical figures i know i could be not normal about if i learned more about them.

#top contenders on the 2nd list rn are necker colbert malthus and smith#yes there is a Theme. no i don't get it either#is this why i once thought i liked alexander hamilton? perhaps#revealing my shit taste

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Before beginning this critique, as I have not finished reading the books, I would like to thank aedesluminis for the references she recommended. Without them, I wouldn't even have been able to place Madame de Stael. This is a personal opinion about her, so I allow myself some deviations that should not be present in a historical analysis. At the moment, my initial impression of her has proven to be justified. First of all, the two million livres that Necker advanced as collateral on his personal fortune. Personally, I wouldn't blame the Treasury for not repaying it because we must remember two things:

Necker amused himself with others in obstructing Turgot, who was much more competent than him. If Turgot had not proposed his austerity plan and had not played the "villain", Necker wouldn't have been able to borrow at all (I acknowledge the limitations of Turgot's economy, but I prefer the austerity plans advocated by Lindet and others at the time of 1793; however, Turgot was much more competent than Necker). Necker wanted this position at any cost, and now he must bear the consequences.

By constantly borrowing, playing the image of the false friend of the people denounced by Marat, and especially hiding the realities of the deficit, Necker would have done better to donate 2 million livres to try to redeem himself (even without these 2 million livres, his situation is much better than that of the vast majority of French people at that time). But let's get back to the subject of Germaine de Stael. As the daughter, she is a privileged witness of 1789. She becomes friends with people like Talleyrand and especially Lameth. She is attached to a moderate revolution of 1791 and does not like that the power of the King (executive) is diminished when he still has significant powers such as the right of veto. She suffers insults from the ultra-royalists, but she doesn't like the republicans much either. Contrary to some legends, Manon Roland is quite different from Madame de Stael. Moreover, the grinding of teeth that I would have against Stael is the fact that she approves of the shooting on the Champ de Mars while citizens were signing a petition for the deposition of the king following the flight to Varennes (thus a justified opinion) in the face of the lie of the National Assembly. With this phrase in 1793, "The Terror, he writes, was nothing but arbitrary pushed to the extreme." In her moral double standard, she will later approve of the repression of April 1, 1795, led by the army, the Muscadins. Not to mention the execution of the last Montagnards. Without any consideration for the economic context, namely the abolition of the maximum and the poor harvests of 1794 which pushed the last sans-culottes to rebel (even if I totally disapprove of the macabre assassination of Féraud), Madame de Stael approves once again. In conclusion, if it is republicans from the extreme left wing of 1791 - who were Girondins and some Montagnards -, Jacobins, Cordeliers or sans-culottes demanding repressive measures, they are awful arbitrary actions, but if it is the opposite camp, it can allow killings according to Germaine de Stael. These double standards should never be tolerated. I am exaggerating, but this is how I feel. The guillotine cannot be used against Madame Stael's friends but can be used against people like Charles Gilbert Romme according to her (I am exaggerating again, but you see where I am going with this).

Moreover, she quickly forgot Barras' role, which was one of the bloodiest of the revolution, to curry favor with him (hypocrisy or political calculation, I will be kind and grant her the second option). Furthermore, she who disapproved of the demonstration of April 1, 1795, by the sans-culottes or the petition demanded by the Cordeliers among others following the King's flight, will approve of a coup d'état which is an even more serious and unconstitutional act (because it comes from the army) on the part of Napoleon. Is she aware of her history? In the absence of following the predictions of a Marat, other Cordeliers, Jacobins, and others who believed that the army should never meddle in the affairs of the country, did she follow the excesses of the Janissaries in the Ottoman Empire? Or simply of Roman history? Quality education doesn't guarantee everything... And yes, Madame de Stael was initially a fervent admirer of Napoleon but later became his opponent due to authoritarian abuses. However, I am against in her biographies the fact of exonerating her from her mistake by saying that many people at the time admired Napoleon and supported the coup d'état. It's untrue; Kleber made a report against Napoleon (although he died before the 18th Brumaire), Prieur de la Marne was against Napoleon, Prieur de la Côte d'Or never accepted anything from Napoleon... So no, this excuse doesn't hold. Let's not forget that Germaine Stael made a dubious comparison between Robespierre and Napoleon; Robespierre surely had flaws but not that of being a dictator, and wouldn't sending armed force against the Convention unlike Napoleon. I acknowledge Madame de Stael for being anti-slavery and for having a good opinion of the consequences of the Hundred Days regarding Napoleon, but I must note that she did not suffer (at least not much) unlike other opponents of Napoleon, namely the Belair couple (Charles and Sanité Belair) who were executed, Jean-Baptiste Antoine le Franc (we must not forget that deportation could be worse than death), and even Simone Evrard who was interrogated (I think Napoleon and his governement wouldn't have arrested her too much time and even less deported her because even he would have realized that it would have been hell to pay if he did that against someone considered the widow of Marat) or even Marie Anne Babeuf watched by Napoleon's police and denounced, etc... But I will continue to read the books; I hope that thanks to these books, my opinion of her will evolve.

Source thank you again aedesluminis

Jean Denis Bredin Une singulière famille

Michel Winock Madame de Stael

Gislaine de Diesbach Madame de Stael

#frev#french revolution#madame de stael#napoleon#barras#romme charles gilbert#robespierre#necker#turgot

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

annnnnd already Death Metal has turned on Necker.. she is literally batting a 0... she should just give up the robot business because she is pretty terrible at it...

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

We all need to talk about how Yusuke Urameshi kept up with a truck on a goddamn BIKE 🔥

#yu yu hakusho#yyh#yusuke urameshi#kazuma kuwabara#shinobu sensui#kaname hagiri#amanuma tsukihito#gourmet#I love the dub so much! he called them rubber neckers 🤣

41 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Suzanne Curchod (1737 – 6 May 1794) was a French-Swiss salonist and writer. She hosted one of the most celebrated salons of the Ancien Régime. She also led the development of the Hospice de Charité, a model small hospital in Paris that still exists today as the Necker-Enfants Malades Hospital. She was the wife of French finance minister Jacques Necker, and is often referenced in historical documents as Madame Necker.

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Christophe Truchi, Marina Delmonde et Stéphane Russel dans “La Guerre des Trônes, la Véritable Histoire de l'Europe : La Révolution Française I (Saison 7)” documentaires présentés par Bruno Solo, décembre 2023.

#films#style#dentelle#xviiie siècle#MarieAntoientte#LouisXVI#Necker#Solo#Truchi#Delmonde#Russel#inspirations bijoux#diamant

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mazurier/マズリエ, "Sur ma peau"/肌刻み込まれたもの/Scene 1 Costume (磯部勉/Isobe Tsutomu) 1789 Les Amants de la Bastille Jp Toho 2018 (1/2)

Production Notes: The actor who plays Ronan and Solene's dad also plays Jaques Necker later in the show.

Parts: 2

#磯部勉#sur ma peau#costume reference#1789 les amants de la bastille#1789バスティーユの恋人たち#1789 バスティーユの恋人たち#1789 toho#マズリエ#Mazurier#tsutomu isobe#Isobe Tsutomu#肌刻み込まれたもの#Jaques Necker#ネッケル

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

hey loser. 1789 called

LMAOOOOOO

4 notes

·

View notes