#muroid

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

59 notes

·

View notes

Text

First drawing of all of them

1 note

·

View note

Text

since artfight just wrapped up i thought i'd share all of the attacks i managed to complete this year! this was my first time participating and it was a lot of fun. i'm proud of myself for being able to finish so many pieces between working and moving states and i'm already looking forward to next year's!! :]

characters and credits listed under the cut!

in order of appearance:

@rainily-03's cassian fitzgerald & sebastian finch

@thefroggiestoffrogs's caleb vatore

@snarksearching's circe cecil snark

granxa's eclipse

@blueammolite's button

@lieutenantcactus's extraordinaire

@dreamcast-official's shining star

@silentnoisemaker's muroide shu

@meowmoths's asmodeus

#my art#artfight#artfight 2024#team stardust#dungeons and dragons#d&d#identity v#twisted wonderland#my little pony#magical girl#others ocs

24 notes

·

View notes

Note

🦎

(partially copy/pasted from a convo we're currently having in the laoft server, so someof you may recognize it)

any living thing (including plants an animals) can be anomalous, but it seems to happen most commonly in (in roughly this order) 1. humans, 2. domesticated species (crops and other domesticated plants, domesticated animals likee cats/dogs/livestock), 3. feral domesticated species (stray cats, dogs, etc) 4. other species that interact specifically with humans in the web (human parasites and diseases, common weeds, common edible wild plants) basically, humans seem to be the primary source of all anomalies, and they kind of radiate out through the ecosystem to the living things most closely associated with or influenced by humans

house lizards, stray cats, muroids, and other common pest animals who develop anomalies will typically have some sort of adaptive ability that lets them live closer to or more easily off of humans, such as their garbage or grain. invisibility is by far the most common of these, but you do occasionally get Literal Rat King Mutants The Size Of House Cats

(which people still sometimes breed for rat fancy, but anomalies arent always passed on genetically. rat king may very well have only perfectly normal rat children)

all of which is to say that chameleons irl cant actually turn invisible but some chameleons in ping verse actually can

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

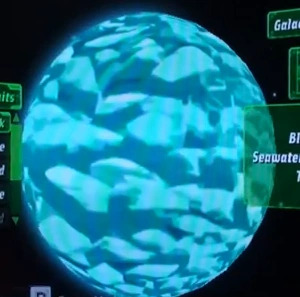

These are some of the planets, moons and other celestial bodies that Ben Tennyson learned about. Khoros is home to the Tetramands, Petropia is home to the Petrosapiens and Crystalsapiens, Pyros is home to the Pyronites, Kinet is home to the Kinecelerans, Galvan Prime is home to the Galvans, Cascareu is home to the Cascans, Galvan Prime's moon, Galvan B is home to the Galvanic Mechamorphs, Flors Verdance is home to the Floraunas, Arburia is home to the Arburian Pelarotas, Lepidopterra is home to the Lepidopterrans, Fulmas is home to the Fulmini, Ekoplekton is home to the Ekoplektoids, Appoplexia is home to the Appoplexians, Terradino is home to the Vaxasaurians. Peptos 12 is home to the Gourmands, Aranaschimmia aka Arachna is home to the Arachnachimps, Piscciss is home to the Piscciss Volanns, Xenon is where Ben met Azmuth, Anur Transyl is home to the Transylians, Anodyne is home to the Anodites, Luna Lobo, Anur Transyl's moon is home to the Loboans, Revonnah is home to the Revonnahganders and Muroids, and Kylmyys is home to the Necrofriggians and Psycholeopterrans.

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Multituberculate Earth: Djadochtatheroidea: The Children of the Desert

Djadochtatherioidea (also spelled Djadochtatheroidea or Djadochatheroida in publications because an already complicated name needs a more labyrinthine approach obviously) is probably the second best understood multituberculate clade due to the amount of complete skeletons. These animals evolved in the Cretaceous of Asia and were in fact the dominant multituberculates in the continent, to the point the only unambiguous non-djadochtatheroidean allothere from the Late Cretaceous of Asia are the taeniolabidoids Erythrobaatar and Yubaatar. They occupied a myriad of ecological niches from the predatory Kryptobaatar to the herbivorous Catopsbaatar, though they all seem to share adaptations for jerboa-like hopping and digging.

Traditionally, it is thought that djadochtatheroideans met their end in the KT event, since they are conspicuously absent from the Asian Paleocene. However, recently two Paleocene groups, Eucosmodontidae and Boffiidae, have been recovered as nested within this group; similarities have been noted between at least the former and classical Asian taxa for years now so it doesn’t come out of nowhere and I’m inclined to believe it. Both groups are still conspicuously absent from Asia, where lambdopsalid taeniolabidoids dominate, so either the Asian species became extinct in the KT event or were quickly displaced by the lambdopsalids. Considering these animals evolved in desert environments, its clear that the wetter forest world of the Paleocene didn’t do them many wonders.

Both eucosmodontids and boffiids continue the trend of djadochateroidean diversity, the former tending towards carnivory with seed side dishes and the latter being a large herbivore, one of the largest mammals of the Belgian Paleocene. In our timeline they actually endured for quite a bit until the PETM, and in this one this is no different at all, the main difference being that they survived this event, having a higher diversity as placentals declined.

Eucosmodontidae

Khusuurbaatarelegans by Dave García.One of various flying euscosmodontid lineages, this one lasted across the Eocene, with fossils found in Asia, Europe, North America, Australia and Antarctica. It was a genus of fast aerial insectivores, this species being the largest known with a wingspan of 60 centimeters.

Relatively basal members of Djadochtatheroidea, eucosmodontids possess large plagiaulacoids, apt for their primarily carnivorous diets with occasional granivory and frugivory. Across the Paleocene and Eocene they mostly diversified as small sized carnivores and omnivores, occupying niches similar to those of muroid rodents, tarsiers and cats, with some otter and desman-like swimmers. Like their Cretaceous relatives they are well adapted to hopping, and larger species resemble carnivorous kangaroos that act like dogs, hopping after prey for long distances. Also like their Cretaceous ancestors (and most multituberculates for that matter) they possess tarsal spurs, though they are rarely venomous as they use that energy and resources for hopping.

Myypbaatar eocursor, a civet or cat like eucosmodontid from the Eocene of Mongolia. Like many of its peers it was a predator, but also an opportunist fruit and seed-eater. By Dave Garcia.

In terms of predatory niches, eucosmodontids carefully remained in the background as other clades like ptilodontoideans and microcosmodontids duked it out. This lasted until the Miocene, when a combination of expanding grasslands and the decline of other multituberculate predators allowed them to sky rocket both as mouse analogues and as carnivoran analogues, mimicking the ecological radiation of those clades in our timeline.

And they were quick to turn to another ecological goldmine: the skies. And in this a group of mostly unassuming hoppers produced some of the most spectacular mammals of this timeline.

Hopping animals, eucosmodontids were prime material for developing powered flight. Most species were only semi arboreal, but in the rainforest world of the Eocene it paid off to be able to use both resources on the trees and the ground. Hopping offered the begins of a flight stroke in the extension of the forelimbs before landing, and as the animals developed various airfoils different wing types evolved. Some like Plummobaatar developed “feathered” wings similar to those of pteroectypodids, while others like Khusuurbaatar developed flying squirrel-like styliform bones on the wrist, that quickly elongated to form a pterosaur-like wing. Others still just developed bat-like wings.

This innovation proved quite useful. Like all flying mammals and pterosaurs, acamapichtliids launch quadrupedally, vaulting using the forelimbs. The backwards-pressing styliform bone adds more power, acting like a spring; likely an ossification of the triceps tendon, it is pulled backwards by the humerus muscles, and against the ulna by wrist tendons. As such it is suffused by tendons inside and out, extending or flexing the bone, preventing it from breaking by distributing pressure and adding additional energy as they move. Combined with the respiratory benefits of the epipubic bones (to which are attached muscle systems responsible for lung ventilation), this allowed acamapichtliid flight to be energy efficient, and they quickly attained massive sizes.

Already by the Rupelian/Chattian boundary these animals attained wingspans of 7 meters, comparable to those of the largest flying birds and contemporary insulonycteriids and surpassed only by the long gone azhdachid pterosaurs; this might represent the current size limit as the wing length is limited due to the styliform folding against the lower arm when in disuse, though derived species are getting around this problem by developing bent wing tips, digitigrade forelimbs and a more flexible yet strong styliform with various ossified tissue and tendon arrangements, all allowing for a potentially longer wing with top-tier folding.

Still, the low aspect ratios are mostly favoured by inland soarers, which is exactly what these animals specialised as. Occupying a niche similar to those of azhdarchid pterosaurs, they stalk their prey in the ground, though their tends to be proportionally larger since all terrestrial mammalian carnivores above 30 kg need to subsist on prey about the same size or larger. This is mostly not a problem the smaller members of this group with wingspans from 2-4 meters, which tend to be under 30 kg, but for the titans they are the first great raptorial flyers, competing both with birds of prey and insulonycteriids as well as terrestrial carnivores like microcosmodontids, ptilodontoideans and flightless eucosmodontids. On island ecosystems acamapichtliids can very well be the apex predators, though even here they retain the ability to fly.

Besides the styliform, acamapichtliids have collagen membranes fibers to keep their wings from fluttering, similar to pterosaur aktinofibrils; these fibers also further help disperse stress and strengthen the styliform when launching. Their uropatagium is supported by a modified calcar-like tarsal spur but it is otherwise small, the long tail being free from it. It is instead used as a display device, for these animals are rather social, gathering in massive flocks when not hunting.

Unlike most djadochtatheroideans, which have fast breeding cycles, acamapichtliids are K strategists. At birth the young can already walk and run, but like all flying mammals they can only take to their air when they’re close to adult size and the young are rather small in proportion to the mother in order to save weight (i.e. a species with a seven meter wingspan produces a pup the size of a domestic cat). This leaves them at least one year on the ground, so to lessen vulnerability most species form creches like those of flamingos, even located in less hospitable environments like salt flats to deter predators. Both parents take care of the young, males capable of producing milk much like in some bats. Even after growing large enough to fly the young may stay in the vicinity of the family group, with males being the most likely to leave.

Flightless eucosmodontids are mostly retricted to the northern continents, but both acamapichtliids and some Eocene flyers have managed to reach as far south as Antartica. In the southern continents they frequently meet their distant relatives, the boffiids.

Tauutus peon, a derived bipedal boffiid from the Late Oligocene of Africa. These animals tended towards fast running herbivorous niches, and eventually graduated from kangaroo-like hopping to theropod-like running. By Dave García.

More derived and related to forms like Catopsbaatar, boffiids debuted as the large herbivore Boffius splendidus and indeed most members of this group are herbivorous, even losing the plagiaulacoid. They seem to have been displaced from Asia by lambdopsalids in both timelines, and in this one they kept diversifying in Europe’s Eocene, where they produced a myriad of hopping herbivores, some as large as a red kangaroo.

Messelboffius atraxa, a red-kangaroo sized hopper from the Eocene of Europe. By Dr Spooky.

The Grand Coupure led to the end of these forest-dwelling hoppers in Europe, but a lineage managed to raft its way to Afro-Arabia during the mid-Eocene. Here they diversified, there being not only no other djadochtatheroideans besides them but also no other fast-running small herbivores and omnivores, galulatheriids being specialised herbivores, kogaionids hypercarnivorous and afroptilodontoideans stuck in the trees (barring some terrestrial seed eaters). As such, they underwent a massive adaptative radiation, giving rise to a variety of kangaroo and springhare-like hoppers, anomalure-like tree climbers and even tree-kangaroo-like folivores as leaves were too icky for afroptilodontoideans. Most notably, one lineage became bipedal runners, likely evolving in a similar manner as our timeline’s sthenurine kangaroos by being forced to walk bipedally while browsing, though unlike them they were truly agile animals like small dinosaurs. A number of species also appear to have been in an intermediary state, between bipedal runners and hoppers; in general, hoppers preffered open environments and were grazers while runners were forest animals and browsers, with both groups having mixed feeders.

Diagram of Messelboffius atraxa, showcasing its musculature. By Dr. Spooky

Two lineages rafted forth from Africa in the Eocene/Oligocene boundary: one to Madagascar and one to South America. The former diversified in a way similar as they did in Africa, but the latter were met with an essentially overcrowded continent with all manner of mammal lineages. For now, they simply occupy small hopping herbivore niches similar to that of our timeline’s Argyrolagus, but the decline of local omnivores and carnivores by the late Miocene might imply an expansion, particular as eucosmodontids haven’t reached South America yet…

#multituberculate earth#multituberculate#multituberculata#spec evo#speculative zoology#speculative biology

12 notes

·

View notes

Note

Might I have an assigned creature, please?

woe! muroid be upon ye!

Superfamily Muroidea

https://www.inaturalist.org/observations/112635074

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sitting here, trying to think of species we know in Ben 10 share a homeworld or system.

We know Earth has at least five native sapients

Piscciss has two

According to the Reboot Petropia actually has three

DJW claimed that the muroids might have crept into the sapient zone, which doesn't seem impossible, so Revonnah may have two

X'Nelli might depending on whether the Polar Manzardill are the only sapient members of their category or if it's a 'multiple species of Homo ran around at once' situation

Kuisana, according to merch, has at least one other sapient species alongside the Orishan on it which from what little we get seem like they're likely native

Terradino has the Vaxaurians and whatever Astrodactyl is

Whatever system the Galvan's inhabit has them and the Mechamorphs at the very least, but may have more depending on who it is that kept them as pets in their early history- visitors from other systems or natives to their own

Cascareau may have two sapient species, we don't know for whether the other one we see alongside the Cascan is native to the planet, the system, or completely non-native

Don't know for sure whether Prypiatosians of Prypiatos are two separate species at this point, but they might be

The Atrocians and whatever Ball Weevil is apparently share a homeworld of Atrocius 0

And of course the Anur System has native inhabitants for about every planet and one at least moon

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

What's Rooks reaction to Draal when he bags a couple of Muroids for a snack?

A raised eyebrow. Rook chalks it up to troll appetites as various species eat foods that others would find disgusting or inedible.

#sonicasura#sonicasura answers#asks#cf8wrk4u us#trollhunters#tales of arcadia#toa trollhunters#tales of arcadia trollhunters#toa#draal#draal the deadly#ben 10 rook#rook blonko#omnitrix wearer!jim#ben 10#ben 10 series#ben ten#ben ten series

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Muroide Shu, Commander of the Crimson Fate and righthand man to a satyr, Lord Sanguine. Though, his friends call him by his real name, Orion.

Bellatrix has been part of the Crimson Fate for thirteen years, and has made close connections with all of them. Shu, though uptight and constantly stressed, is one of her closest friends. Her and Orion love to poke fun at his stoic and matter-of-fact speaking all the time.

Aurelian, after living int he woods for her whole life, is learning about city life. She doesn't know that many terms, and asks every question she can to further her knowledge, but oh gods Shu gets SO FRUSTRATED SO EASY.

Orion and Bella love to push his buttons. And when there's no guests around, Orion can easily make Shu so frustrated he will actually yell.

All in good fun though <3

#dnd#d&d#oc#oc art#shu#orion#bellatrix#aurelian#god i love my players#theyre so funny when they rp with my oc's#I MEAN UH#NPCS#who am i kidding this is my world and all my babies they get to play with its an rp dream come true#just with added mechanics and dungeons and dragons shit#i love everyone so much

6 notes

·

View notes

Note

Since they're so intelligent, do you think Ben could turn into a Muroid?

I think they were just intelligent enough to be trained, not enough to be sapient

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hi guys! So I put these two drawings together just cuz they’re both character references/ concepts! I figured both would be cool to explain. Also for Reina it’s just concept art but nothing much isn’t going to change just gotta finalize some things.

For my ponysona ref I just did it for fun, really was into the trait randomizer on TikTok and made her! Her name is Sugar Kisses and her cutie mark is a camera with a rose tinted lense cuz she can capture those sweet moments. She does this by being a wedding photographer!

As for Reina Valencia she is a self insert for Ben 10 Omniverse cuz I LOVE Rook Blanco. So for her, long story short: She’s half Revonnahgander and half Human, she grew up with her dad who was a Plumber until they got separated, luckily she got stranded on Revonnah and tries to find her mother despite the discrimination from the Revonnahganders due to her human features. She resides with in the tunnels with the Muroids.

#sleepycaramelart#mlp art#mlp oc pony#mlp ponysona#oc art#my ocs#ben 10 omniverse#Ben 10 Omniverse OC#self insert#character concept#character ref sheet

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

I don't really play MtG, but the lore and card art has always intrigued me. It's like I have become fond of saying since I heard the phrase Adventure Time:

I've a few questions in mind:

The Myr appear to be bird-like considering the head shape, but also draw from ants in their name and "social structure"... Any thoughts on what their name would be if they appeared more like rodents or another social species such as canines?

The Gremlins in Kaladesh(?) have a resemblance to 6-limbed aardvarks, caustic saliva and feed on Ether IIRC. Is Ether a colorless resource separate from Mana or a transmuted form of Mana for artifacts?

Couldn't said Gremlins be a bit cuter?

Any opinions on the kinda grody appearance of the Compleated Weatherlight? Consider the diversification of Phyrexians, how do you think one faction's Compleated form would differ from the others?

That's all for the time being. If this is too long just let me know... Thanks for your time & TTFN.

1. I’m the worst at coming up with fantasy names! You can maybe just see “Myr” from Myomorpha, a big rodent suborder, but yeah, the name is really from ants by way of the Myrmidons, Achilles’s troops in the Iliad. Trying to think of something if my own, I came up with “muroid”, which is just directly ripping off Myomorpha superfamily Muroidea.

2. Yep, that’s Kaladesh you’re thinking of. IIRC aether is just the form mana takes on that plane. All colors can draw on it, and there are colorless uses too.

3. I think they’re plenty cute! They’re like nude cats (binguses/bingi). Also reminiscent of Dragon Age nugs. But I suppose the obvious answers are give them some hair or have them drool less.

4. That hit me hard as an older player who remembers old Weatherlight story. I suppose it’s supposed to look grody. On New Phyrexia, at least, there are distinctive looks for the five colors/praetors, so yeah, I’d expect a Weatherlight compleated by forces other than Sheoldred’s would look different.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Multituberculate Earth: Djadochtatheroidea

Djadochtatherioidea (also spelled Djadochtatheroidea or Djadochatheroida in publications because an already complicated name needs a more labyrinthine approach obviously) is probably the second best understood multituberculate clade due to the amount of complete skeletons. These animals evolved in the Cretaceous of Asia and were in fact the dominant multituberculates in the continent, to the point the only unambiguous non-djadochtatheroidean allothere from the Late Cretaceous of Asia are the taeniolabidoids Erythrobaatar and Yubaatar. They occupied a myriad of ecological niches from the predatory Kryptobaatar to the herbivorous Catopsbaatar, though they all seem to share adaptations for jerboa-like hopping and digging.

Traditionally, it is thought that djadochtatheroideans met their end in the KT event, since they are conspicuously absent from the Asian Paleocene. However, recently two Paleocene groups, Eucosmodontidae and Boffiidae, have been recovered as nested within this group; similarities have been noted between at least the former and classical Asian taxa for years now so it doesn’t come out of nowhere and I’m inclined to believe it. Both groups are still conspicuously absent from Asia, where lambdopsalid taeniolabidoids dominate, so either the Asian species became extinct in the KT event or were quickly displaced by the lambdopsalids. Considering these animals evolved in desert environments, its clear that the wetter forest world of the Paleocene didn’t do them many wonders.

Both eucosmodontids and boffiids continue the trend of djadochateroidean diversity, the former tending towards carnivory with seed side dishes and the latter being a large herbivore, one of the largest mammals of the Belgian Paleocene. In our timeline they actually endured for quite a bit until the PETM, and in this one this is no different at all, the main difference being that they survived this event, having a higher diversity as placentals declined.

Eucosmodontidae

Khusuurbaatar elegans by Dave García. One of various flying euscosmodontid lineages, this one lasted across the Eocene, with fossils found in Asia, Europe, North America, Australia and Antarctica. It was a genus of fast aerial insectivores, this species being the largest known with a wingspan of 60 centimeters.

Relatively basal members of Djadochtatheroidea, eucosmodontids possess large plagiaulacoids, apt for their primarily carnivorous diets with occasional granivory and frugivory. Across the Paleocene and Eocene they mostly diversified as small sized carnivores and omnivores, occupying niches similar to those of muroid rodents, tarsiers and cats, with some otter and desman-like swimmers. Like their Cretaceous relatives they are well adapted to hopping, and larger species resemble carnivorous kangaroos that act like dogs, hopping after prey for long distances. Also like their Cretaceous ancestors (and most multituberculates for that matter) they possess tarsal spurs, though they are rarely venomous as they use that energy and resources for hopping.

In terms of predatory niches, eucosmodontids carefully remained in the background as other clades like ptilodontoideans and microcosmodontids duked it out. But they were quick to turn to another ecological goldmine: the skies. And in this a group of mostly unassuming hoppers produced some of the most spectacular mammals of this timeline.

Hopping animals, eucosmodontids were prime material for developing powered flight. Most species were only semi arboreal, but in the rainforest world of the Eocene it paid off to be able to use both resources on the trees and the ground. Hopping offered the begins of a flight stroke in the extension of the forelimbs before landing, and as the animals developed various airfoils different wing types evolved. Some like Plummobaatar developed “feathered” wings similar to those of pteroectypodids, while others like Khusuurbaatar developed flying squirrel-like styliform bones on the wrist, that quickly elongated to form a pterosaur-like wing. Others still just developed bat-like wings.

But the most successful clade came at the Eocene/Oligocene transition, when the Grand Coupure was busy killing off the previous flying djadochtatheroideans as their habitats collapsed. One cat sized species, Acamapichtli tlatoani, developed unciform styliforms on the elbow, similar to those of anomalures. These quickly grew larger in descendent species, the Acamapichtliidae, forming a bizarre wing supported not by a wing finger, but an independently acquired bone.

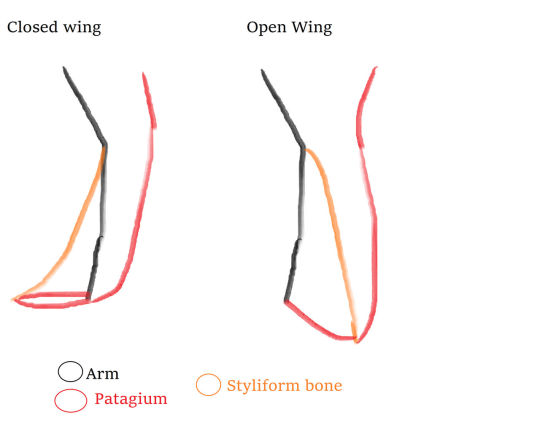

Acamapichtliid wing morphology diagram by yours truly.

This innovation proved quite useful. Like all flying mammals and pterosaurs, acamapichtliids launch quadrupedally, vaulting using the forelimbs. The backwards-pressing styliform bone adds more power, acting like a spring; likely an ossification of the triceps tendon, it is pulled backwards by the humerus muscles, and against the ulna by wrist tendons. As such it is suffused by tendons inside and out, extending or flexing the bone, preventing it from breaking by distributing pressure and adding additional energy as they move. Combined with the respiratory benefits of the epipubic bones (to which are attached muscle systems responsible for lung ventilation), this allowed acamapichtliid flight to be energy efficient, and they quickly attained massive sizes.

Already by the Rupelian/Chattian boundary these animals attained wingspans of 7 meters, comparable to those of the largest flying birds and contemporary insulonycteriids and surpassed only by the long gone azhdachid pterosaurs; this might represent the current size limit as the wing length is limited due to the styliform folding against the lower arm when in disuse, though derived species are getting around this problem by developing bent wing tips, digitigrade forelimbs and a more flexible yet strong styliform with various ossified tissue and tendon arrangements, all allowing for a potentially longer wing with top-tier folding.

Still, the low aspect ratios are mostly favoured by inland soarers, which is exactly what these animals specialised as. Occupying a niche similar to those of azhdarchid pterosaurs, they stalk their prey in the ground, though their tends to be proportionally larger since all terrestrial mammalian carnivores above 30 kg need to subsist on prey about the same size or larger. This is mostly not a problem the smaller members of this group with wingspans from 2-4 meters, which tend to be under 30 kg, but for the titans they are the first great raptorial flyers, competing both with birds of prey and insulonycteriids as well as terrestrial carnivores like microcosmodontids, ptilodontoideans and flightless eucosmodontids. On island ecosystems acamapichtliids can very well be the apex predators, though even here they retain the ability to fly.

Besides the styliform, acamapichtliids have collagen membranes fibers to keep their wings from fluttering, similar to pterosaur aktinofibrils; these fibers also further help disperse stress and strengthen the styliform when launching. Their uropatagium is supported by a modified calcar-like tarsal spur but it is otherwise small, the long tail being free from it. It is instead used as a display device, for these animals are rather social, gathering in massive flocks when not hunting.

Unlike most djadochtatheroideans, which have fast breeding cycles, acamapichtliids are K strategists. At birth the young can already walk and run, but like all flying mammals they can only take to their air when they’re close to adult size and the young are rather small in proportion to the mother in order to save weight (i.e. a species with a seven meter wingspan produces a pup the size of a domestic cat). This leaves them at least one year on the ground, so to lessen vulnerability most species form creches like those of flamingos, even located in less hospitable environments like salt flats to deter predators. Both parents take care of the young, males capable of producing milk much like in some bats. Even after growing large enough to fly the young may stay in the vicinity of the family group, with males being the most likely to leave.

Flightless eucosmodontids are mostly retricted to the northern continents, but both acamapichtliids and some Eocene flyers have managed to reach as far south as Antartica. In the southern continents they frequently meet their distant relatives, the boffiids.

Boffidae

Tauutus peon, a derived bipedal boffiid from the Late Oligocene of Africa. These animals tended towards fast running herbivorous niches, and eventually graduated from kangaroo-like hopping to theropod-like running. By Dave García

More derived and related to forms like Catopsbaatar, boffiids debuted as the large herbivore Boffius splendidus and indeed most members of this group are herbivorous, even losing the plagiaulacoid. They seem to have been displaced from Asia by lambdopsalids in both timelines, and in this one they kept diversifying in Europe’s Eocene, where they produced a myriad of hopping herbivores, some as large as a red kangaroo.

Messelboffius atraxa, a red-kangaroo sized hopper from the Eocene of Europe. By Dr Spooky.

The Grand Coupure led to the end of these forest-dwelling hoppers in Europe, but a lineage managed to raft its way to Afro-Arabia during the mid-Eocene. Here they diversified, there being not only no other djadochtatheroideans besides them but also no other fast-running small herbivores and omnivores, galulatheriids being specialised herbivores, kogaionids hypercarnivorous and afroptilodontoideans stuck in the trees (barring some terrestrial seed eaters). As such, they underwent a massive adaptative radiation, giving rise to a variety of kangaroo and springhare-like hoppers, anomalure-like tree climbers and even tree-kangaroo-like folivores as leaves were too icky for afroptilodontoideans. Most notably, one lineage became bipedal runners, likely evolving in a similar manner as our timeline’s sthenurine kangaroos by being forced to walk bipedally while browsing, though unlike them they were truly agile animals like small dinosaurs. A number of species also appear to have been in an intermediary state, between bipedal runners and hoppers; in general, hoppers preffered open environments and were grazers while runners were forest animals and browsers, with both groups having mixed feeders.

Diagram of Messelboffius atraxa, showcasing its musculature. By Dr. Spooky

Two lineages rafted forth from Africa in the Eocene/Oligocene boundary: one to Madagascar and one to South America. The former diversified in a way similar as they did in Africa, but the latter were met with an essentially overcrowded continent with all manner of mammal lineages. For now, they simply occupy small hopping herbivore niches similar to that of our timeline’s Argyrolagus, but who knows what the future has in store…

#multituberculata#multituberculate#multituberculate earth#spec evo#speculative zoology#speculative evolution#speculative biology

7 notes

·

View notes

Note

Still mad that muroids are considered sapient enough to be in the omnitrix

FAIR

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Un éclairage sur certains arbovirus peu connus dont l'incidence, la distribution et l'impact sur la santé humaine ou animale sont en augmentation

See on Scoop.it - EntomoNews

Arboviruses (arthropod-borne viruses) are a class of viral pathogens that are transmitted by arthropod vectors in nature. They are responsible for many vector-b

Ary Faraji, Goudarz Molaei, Theodore G. Andreadis

Emerging and lesser-known arboviruses impacting animal and human health Ary Faraji and others Journal of Medical Entomology, tjad140, https://doi.org/10.1093/jme/tjad140

Ary Faraji (Data curation [Equal], Writing—original draft [Equal], Writing—review & editing [Equal]), Goudarz Molaei (Writing—original draft [Equal], Writing—review & editing [Equal]), and Theodore Andreadis (Writing—original draft [Equal], Writing—review & editing [Equal]) We hope that ...

The known unknowns of Powassan virus ecology Doug E Brackney and Chantal B F Vogels Journal of Medical Entomology, tjad095, https://doi.org/10.1093/jme/tjad095 Powassan virus (POWV; Family: Flaviviridae, Genus: Flavivirus ) is the sole North American member of the tick-borne encephalitis sero-complex. While associated with high rates of morbidity and mortality, POWV has historically been of little public health concern due to low incidence rates. However, ...

Everglades virus: an underrecognized disease-causing subtype of Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus endemic to Florida, USA Nathan D Burkett-Cadena and others Journal of Medical Entomology, tjad070, https://doi.org/10.1093/jme/tjad070 Everglades virus (EVEV) is subtype II of the Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus (VEEV) complex (Togaviridae: Alphavirus), endemic to Florida, USA. EVEV belongs to a clade that includes both enzootic and epizootic/epidemic VEEV subtypes. Like other enzootic VEEV subtypes, muroid rodents are ...

La Crosse virus neuroinvasive disease: the kids are not alright Corey A Day and others Journal of Medical Entomology, tjad090, https://doi.org/10.1093/jme/tjad090 La Crosse virus (LACV) is the most common cause of neuroinvasive mosquito-borne disease in children within the United States. Despite more than 50 years of recognized endemicity in the United States, the true burden of LACV disease is grossly underappreciated, and there remain severe knowledge gaps ...

Emerging tickborne viruses vectored by Amblyomma americanum (Ixodida: Ixodidae): Heartland and Bourbon viruses Alan P Dupuis and others Journal of Medical Entomology, tjad060, https://doi.org/10.1093/jme/tjad060 Heartland (HRTV) and Bourbon (BRBV) viruses are newly identified tick-borne viruses, isolated from serious clinical cases in 2009 and 2014, respectively. Both viruses originated in the lower Midwest United States near the border of Missouri and Kansas, cause similar disease manifestations, and are ...

The increasing threat of Rift Valley fever virus globalization: strategic guidance for protection and preparation Seth Gibson and others Journal of Medical Entomology, tjad113, https://doi.org/10.1093/jme/tjad113 Rift Valley fever virus (RVFV) (Bunyavirales: Phlebovirus ) is a prominent vector-borne zoonotic disease threat to global agriculture and public health. Risks of introduction into nonendemic regions are tied to changing climate regimes and other dynamic environmental factors that are becoming more ...

Colorado tick fever virus: a review of historical literature and research emphasis for a modern era Emma K Harris and others Journal of Medical Entomology, tjad094, https://doi.org/10.1093/jme/tjad094

Colorado tick fever virus is an understudied tick-borne virus of medical importance that is primarily transmitted in the western United States and southwestern Canada. The virus is the type species of the genus Coltivirus (Spinareoviridae) and consists of 12 segments that remain largely ...

Culicoides-borne Orbivirus epidemiology in a changing climate Amy R Hudson and others Journal of Medical Entomology, tjad098, https://doi.org/10.1093/jme/tjad098 Orbiviruses are of significant importance to the health of wildlife and domestic animals worldwide; the major orbiviruses transmitted by multiple biting midge ( Culicoides ) species include bluetongue virus, epizootic hemorrhagic disease virus, and African horse sickness virus. The viruses, insect ...

Cache Valley virus: an emerging arbovirus of public and veterinary health importance Holly R Hughes and others Journal of Medical Entomology, tjad058, https://doi.org/10.1093/jme/tjad058 Cache Valley virus (CVV) is a mosquito-borne virus in the genus Orthobunyavirus (Bunyavirales: Peribunyaviridae) that has been identified as a teratogen in ruminants causing fetal death and severe malformations during epizootics in the U.S. CVV has recently emerged as a viral pathogen causing ...

Jamestown Canyon virus comes into view: understanding the threat from an underrecognized arbovirus John J Shepard and Philip M Armstrong Journal of Medical Entomology, tjad069, https://doi.org/10.1093/jme/tjad069 This review examines the epidemiology, ecology, and evolution of Jamestown Canyon virus (JCV) and highlights new findings from the literature to better understand the virus, the vectors driving its transmission, and its emergence as an agent of arboviral disease. We also reanalyze data from the ...

Snowshoe hare virus: discovery, distribution, vector and host associations, and medical significance Edward D Walker and Thomas M Yuill Journal of Medical Entomology, tjad128, https://doi.org/10.1093/jme/tjad128 Snowshoe hare virus (SSHV), within the California serogroup of the genus Orthobunyavirus , family Peribunyaviridae , was first isolated from a snowshoe hare ( Lepus americanus ) in Montana, United States, in 1959. The virus, closely related to LaCrosse virus (LACV) and Chatanga virus (CHATV), ...

0 notes