#multituberculate earth

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Illyriolestes piscimimus, a new critter for Multituberculate Earth: https://multituberculateearth.wordpress.com/2022/04/03/mammals-at-sea/

#multituberculate earth#dryolestoid#dryolestoidea#dryolestida#meriodiolestida#meridiolestid#speculative zoology#spec evo#speculative biology

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Aggression/ Danger to humans: High - Medium

Element/ Ailment: Scent Marking

The Azure Falswine “Tusk Boar” or T’ïkh Balat/ T’ïkhxpïm (Tuhk Balat/ Tuhk-Pym) meaning “Tusk Boar/ Falswine,” sometimes called the Azure Menace, is a small hooved multituberculate that inhabits the forests of the Northern Eastern Continent of Atterra and is a chiefly vegetarian omnivore. Azure Falswine travels in herds (gangs) up to fifty animals strong. What the Azure Falswine lacks in size and weight, it more than makes up for in attitude and defense. With a robust sense of smell, decent eyesight, and good hearing, the Azure Falswine keeps a vigilant lookout for predators in the Atterran wilds at all hours of the day.

During the night, gangs of Azure Falswine will have rotating lookouts, with pregnant females and kids getting the most sleep each night. Should a threat be spotted, the lookouts will sound an alarm to wake up the entire herd and form a defensive ball around the young and pregnant females. Due to their poor night vision, Tusk boars often use their sense of hearing and smell to sniff out the threat. Falswine will use the scent glands on their snouts to paint the target, and the rest of the gang will move towards the scent and attack.

This method of attack works due to the social nature of the Azure Falswine and the way they form bonds within the gang. The scent glands are also used to mark edible feet and nesting areas. All species of Falswine rub each other with their scent glands (Both males and females have them) to bond and intermix their scents. Giving each herd a ‘distinct scent’ unique to their gang and comprised of all the individuals in the gang. Making it easy for Falswine to detect outsiders or gangs at the edges of their territory to attack. Couple this with the scent gland producing a muskier and sharper scent when under stress means that when a predator hunts a Falswine, it or the surrounding area is marked with the alarm scent from the thrashing Falswine. Being a vindictive genus like Earth’s Peccaries or Cape Buffalo, upon smelling the musk of duress from another gang member or species, the whole gang will move to attack the threat to their herd.

Azure Falswine and other Tuskboars have been known to swarm and kill Red-Maned Quill Tails and Guild Huntsman with their sheer numbers and tenacity. There have been a few recorded cases of Falswine waiting up to six hours at the base of a tree a party of Huntsman climbed into, guarding the carcasses of their fellow gang members before leaving the Huntsman and dead behind. This has made Guild Huntsman and other predators wary of hunting Tuskboars, who have taken a hit-and-run approach when hunting Azure Falswine. Should a predator or Huntsman find themselves marked by a Tuskboar, the best course of action is to take the carcass and run or cause enough damage to the herd by killing several pursuing members of the gang so the herd panics and breaks off pursuit. Besides, some predators, such as Chardanes have begun constructing pitfalls and traps to hunt Tusk Boars. The Guild has elected to use bow hunting for a clean kill or light stones to blind and panic the gang of Falswine.

Besides their scent gland, the Azure Falswine and other Tuskboars are equipped with horns on their snout, four tusks, fangs derived from their bicuspids, bone plates on their shoulders, bony spines on their flanks, and hard cartilage plates on their rear. Like the horns, the bony plates and spines are covered in a thin layer of keratin and are used to protect the Tuskboars spine from attack by larger predators. The plates and spines are not connected with the Azure Falswine’s skeleton and instead are anchored into the upper layer of the muscle so as not to impede the movement or flexibility of the animal. The hard cartilage plating on the rump of the Azure Falswine protects the animal’s rear from the jaws of predators. Allowing the Tuskboar to turn around and gore the predator.

When the Tuskboar is not out for the blood of the enemies of its gang, the Azure Falswine uses its hard cartilage-reinforced snout to dig up roots, tubers, mushrooms, and underground worms and grubs to feed on. Besides those, the Falswine likes eating fallen fruit on the forest floor and low-growing ferns, shrubs, nuts, and Wax Fruit. Tuskboars mark the edges of the gang’s territory by rubbing their scent glands on the rocks and trees at the far ends of their range, which, on average, are around a thousand acres in size. The herd periodically moves from feeding ground to feeding ground on well-worn trails throughout the year, with the gang only deviating from the path should one of the two to three small scouting parties (usually between three to 5 individuals in size and usually made up of senior members of the gang) find a new source of food or nesting grounds for the gang.

Tuskboars can mate and give birth in any season to twins or triplets per litter, with two births happening yearly and primarily in the spring and summer months. Female Tuskboars will gestate their kids for five months before giving birth to a litter of kids, usually around a pound in weight at first breath. Kids are very vocal and playful, lacking the bone plating of mature Falswine, and will nurse for eight weeks before weaning and moving onto solid food. Baby Azure Falswine are usually reddish and black in color with white bellies like adults but lack the characteristic blue fur (The blue coloring being due to hair follicle structure and not blue pigmentation in the fur) of mature individuals.

Tuskboars mature at two years and can live up to an average of ten years in the wild, with captive or lucky individuals living over twenty years of age. Male and female Falswine are identical in appearance, with the only way to tell the difference between the genders is their size. Male Tuskboars are fifteen percent larger than females in height and body mass, with females almost always accompanied by their kids in the spring and summer months. When a female of the gang goes into heat, the dominant male (Often the oldest and strongest surviving male) will breed with the fertile female. Shoving matches will ensue if any other male Falswine wants to dethrone the gang’s Patriarch for breeding rights. So far, attempts to domesticate Tuskboars have been less than stellar, and their aggressive and high-strung nature makes them a poor candidate for domestication. Making it so that certain Hakdor tribes that are almost as stubborn as the Tuskboars themselves try breeding out aggression towards humanoids as a means of domestication. After almost a century of breeding, this method yields some positive results, creating a more agreeable breed of Falswine for food or pets. Something human breeders are having trouble accomplishing, and more than one has lost their lives attempting to recreate.

#art#artwork#creature#creature art#creature design#digital art#drawing#illustration#monster design#monsters#monster art#monster#creature drawing#creatures#fantasy creature#creative design#fantasy worldbuilding#fantasy#fantasy art#speculative biology#speculative evolution#speculative zoology#speculative ecology#alternate universe#alternate timeline#digiart#digial art#digialillustration#digial painting#digital 2d

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

More aquatic up:Beginning of the Wrabs for @the6planet8ofbats

The early thallasocene - 101 Million Years After Post Establishment

This not hamsters paradise,for @the6planet8ofbats

Like rattiles (a clade of ectothermic hamsters descended from surface molrocks) by @tribbetherium A group of bats become https:/en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carcination meaning crab-like body plan called Warbs are descended from some bats called Molarchs are into Pikabats like Molemice from by @tribbetherium become various different groups

Warbs is actually just an example of Carcinazation,which is known tobbe mammals,perhaps no arthropods. Like most mammals (Except Monotromes and Allotheres like Gondwanatheres or Multituberculates) reproduced by giving birth. Warbs become losing patagium,one of the few bat lineages of this Planet not have patagium.

But Warbs have hunters,examples like invertebrate Goliath Warbeater (Spiroteutholimax goliath) like Goliath screwhorn (Spiroteuthocochleus giganteus) by @tribbetherium and Two red-striped magicirill (Magocanaus dirhodostripus) is a krill

A vertebrate is omnivore,but only eating animals are Warbs a cetacean named Poultry porpoise (Galloenus omnivorus) much like earth's chickens or other Poultry like a Guineafowl

Whetever or not??? This decision is entirely up to you!!!! ☺️☺️☺️☺️☺️☺️☺️☺️👏👏👏👏👏👏

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

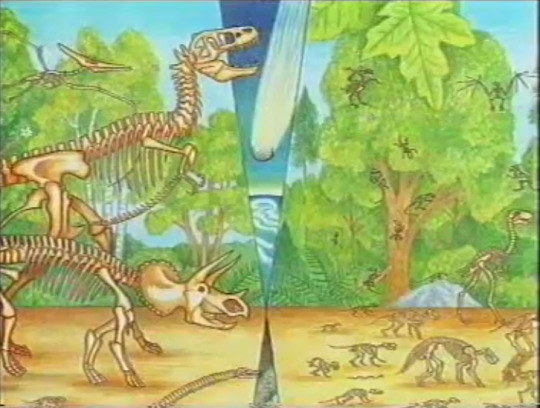

Identifying Skeletons from Drawings

Okay, Paleonerds, I need help. I've been going through every piece of Paleomedia I can get my hands on, logging them, and trying to ID as many of the prehistoric fauna as I can.

Today, I hit a hard one.

This art is from the 1996 BBC Documentary "Life & Earth", and while the Mesozoic fauna is easy enough (Pteranodon, Tyrannosaurus, Triceratops, Didelphodon, Elasmosaurus), the Paleogene (Or Early Tertiary one as was known at the time) is a lot harder.

I mean, there's more to ID and a lot of it is small.

Still, I was able to identify Gastornis, Barylambda, and Palaeochiropteryx.

There are probably a few ungulates, carnivorans, creodonts, primates, and multituberculates that are just a wash.

If anyone knows what the things are, or better yet, the art piece this is from, let me know!

#Paleontology#Paleomedia#Life & Earth#BBC#Documentary#Dinosaurs#Mammals#Prehistoric#Extinction#Tyrannosaurus#Pteranodon#Triceratops#Elasmosaurus#Didelphodon#Paleogene#Gastornis#Barylambda#Palaeochiropteryx

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Free Speculative Evolution Prompt Saturday: K-PG Lightning Round!

66 million years ago, a mass extinction event wiped out 75% of life on earth, wiping out the dinosaurs, and leading to the age of mammals. And 66 million years later a sapient species of hairless primates discovers dinosaur bones and imagines what would happen if they never went extinct.

For those who don't want to follow this trope but still like the idea of alerting the cenozoic through the end K-PG this is your post.

Part One: Changing Difficulties

One of the easiest ways of changing the Cenozoic through the end Cretaceous is by lowering or increasing the percentage of life being wiped out from the end Cretaceous. For example, if the percentage was lowered by 60 or less you could have other mammals like multituberculates and Dryolestida, you could even include some non avian dinosaurs survive to the Cenozoic. now for the opposite side of the scale you could go full on Sephiroth and go 80 to END PERMIAN levels of extinction, wiping off the birds, most of the placental mammals, and all gymnosperm plants! leaving a world much weirder then where we were.

Part 2: Location Location Location

We all know about the butterfly effect right? one small or insignificant change would change everything, from a butterfly fluttering it's wings, to the exact location of a asteroid hitting earth. while it will wipe out 75% of life on earth, but the brunt of the death would depend on where the asteroid would hit, and no I'm not just talking about the amount of animals that would die near the impact but the rest of ecosystems of the hemisphere. for example, if the asteroid hit somewhere off the coast of Chile or northern Argentina more southern hemisphere animals would die then the northern hemisphere animals.

Part 3: The Cause

let's say you wanted to be creative and don't want a asteroid wiping out the dinosaurs, you might wanna have the earth go through a ice age in the K-PG, or maybe have the deccan traps be more destructive to earth, or maybe some alien space bats to cherry pick the animals you don't like and kill them. Be creative.

#speculative biology#speculative zoology#speculative evolution#spec bio#alternate timeline#alternate universe#dinosaurs#cretaceous#late cretaceous#cenozoic#K-PG

1 note

·

View note

Text

There were once massive glaciers until the ice ages came to a sudden close when an asteroid struck into the north pole of Ataran to create the Emba Ocean over 49 million years ago. The impact saw the fall of previous civilizations and the perfect circumstances needed to inspire agriculture did not come back until the last epoch of the Cenozoic nearly 6 million years after the Younger Dryas Impact in the north pole. When civilization returned, the enantiornithine birds who had once joined megaraptorans, baboons, and cuttlefish in their civilization building were no-more, left instead to their intellectually devolved state.

However, these civilization-building evolutionary geniuses were not the only ones who had bounced back. The Malayan Tapir for example, the sole survivor of the Tapir lineage had gone on to sprout one of the most successful evolutionary lines of the late Cenzoic. Large bodies Tapirs had gone on to replace many animals such as the horse and buffalo of the Holocene, while Caimans grew to become 25 foot giants in some cases and some became small terrestrial creatures. Their success following the Younger Dryas would save them from what was worst to come as with the return of civilization came the return of large scale war, and with it, weapons of mass destruction. Not much is known about the End-Cenozoic War to the current inhabitants of Ataran. but of what is known this much is true. The largest cities of the Cuttlefish-like creatures were almost certainly in the Emba Sea, at the time it was the most successful low lying sea in the world if possible fossilization bias is to be ignored. The historians of the future still often debate on exactly why, and the physicists on how, but a weapon of the baboon-animals is said to have relatively abruptly dried the ocean between their homelands and the homelands of the Proto-O’Zehra megaraptorans. The effects of this brought the most disastrous and powerful war known to Ataran/Earth’s history(ies).

The fossil record, somewhat ironically, is by far the most complete and well understood thing regarding the flora and fauna of this time, despite several detailed accounts remaining of parts of the civilizations of the time (or at least the millennia's following the event), even after almost 45 million years.

What is shown is tragic. A mass extinction to second only the Great Dying in the East and surpass it in the West. The few multituberculates surviving from the Eocene made it only due to their presence in a small island that fared better than most of the western sectors of Ataran. They would grow to lead a large legacy in the eons following the planet’s recovery. However, they would not be alone. Tapirs, Dolphins, Frogs, Cuttlefish, Jumping Spiders, Centipedes, Cheetahs, Caimans, Megatherian sloths, Phorusrhacids, descendants of the Okapi, and numerous types of non-enantiornithine and non-avian dinosaurs would bounce back and flourish in life's next stage.

Among them were the descendants of every animal inhabiting the great valley of Xalembasa, the bowl continent. Tapirs, like in most places in Kliaxiya, have remained as breakout stars for tens of millions of years in many different forms. Now is no different as they swagger across the salt-filled environment left behind from the now gone Emba Ocean. While the horse like Daradar is by far the most common and most successful of these large creatures, tapiroidea includes other very notable and popular members. This includes one of the mammal’s biggest accomplishments, a 14 Ton Tapir. The largest mammal of the late Efrahnozoic, a full 49.08 Million Years since the Holocene, this is Titanotapirus Saliscus. As a giant comparable to the Paracetherium before it, it is suffice to say that its mere presence commands a sense of bewilderment and even submission.

Ladies and gentlemen, welcome to the home of the weird, woeful, gorgeous, and giant. Welcome to Xalembasa. Welcome to Kliaxiya. Welcome to Earth Ataran.

.

.

.

.

Yeah so I guess I'm back in the game :D I'm gonna start commissions soon to and I guess explore the world on Tumblr as the book continues to progress. Also I'm gonna post less detailed stuff on Instagram so be on the look out if you came from there!

-Kai/Dezdanni

.

.

.

^ A map of the Western Sectors of Ataran, the most similar planet to Earth out of every explored dimension. A map of Earth for scale, more detail on this coming soon! : )

Also the music being used has been cited in the description of it. I am using this under the terms of fair use. All credit goes to Geoff Knorr and all the musicians who created this soundtrack because they kicked it out of the ball park with the Civilization 6 Official Sound Track.

#speculative biology#speculative evolution#science fantasy#science fiction#scifi#fantasy map#bookblr#world building#dinosaurs#hippos#malayan tapir#dinosaur#dragon#drama#world exploration#writers on tumblr#writing#future#evolution#black stories#science#sciblr#scifi au#scifiart#scififantasy#sci fi writing#scifibooks#daradar#harlem hell rat#art

1 note

·

View note

Text

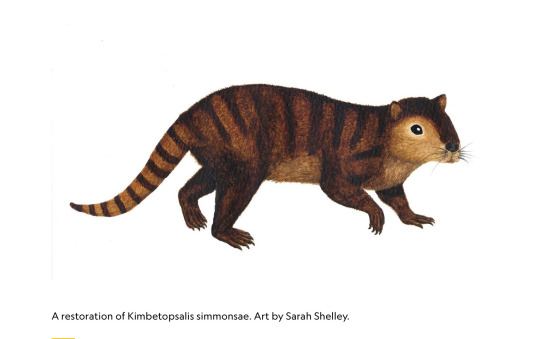

Hey guys, how ‘bout a fun fact science corner? I’m wanting to talk about Kimbetopsalis Simmonsae. I know it’s a big word, sadly we don’t have common names for most extinct animals so any creature that hasn’t existed within the last 1000 years is gonna be a mouthful.

Now what does Kimbetopsalis have to do with Cro-Marmot and Dumuzi? This is where science and my headcanons merge.

So Let’s talk Dino-Sore days.

If Cro was around during the age of the Dinosaurs, that dates him all the way back to the Mesozoic era. So let’s throw him at the tail end of the Cretaceous period, when the most popular of the giant reptiles reigned, tyrannosaurus, the titanosaurs, pteranodon, ect.

Marmots did not exist at any time during the entirety of the Mesozoic. In fact, though many of the mammals that lived during that time were very rodent like, true rodents did not even appear for another 10 million years after dinosaurs were wiped off the face of the planet. And marmots did not evolve for at LEAST another 48 million years after THAT.

So Cro and his sister Dumuzi could not have been marmots. So then what were they?

Time to put on my paleonerd hat.

Meet Kimbetopsalis Simmonsae

To the left we have paleoart of what we believe Kimbetopsalis to have looked like, and to the right we have a modern day marmot. Not too drastically different, eh?

Now here’s what’s really cool about Kimbetopsalis. We have fossil evidence that tells us that they are one of the few survivors of the K/PG mass extinction. That’s right, these are one of the legendary mammals that survived the famous asteroid impact that wiped out all the non-avian dinosaurs and played a role in bringing forth the Age of Mammals. If it weren’t for little survivors like them, we wouldn’t be here!

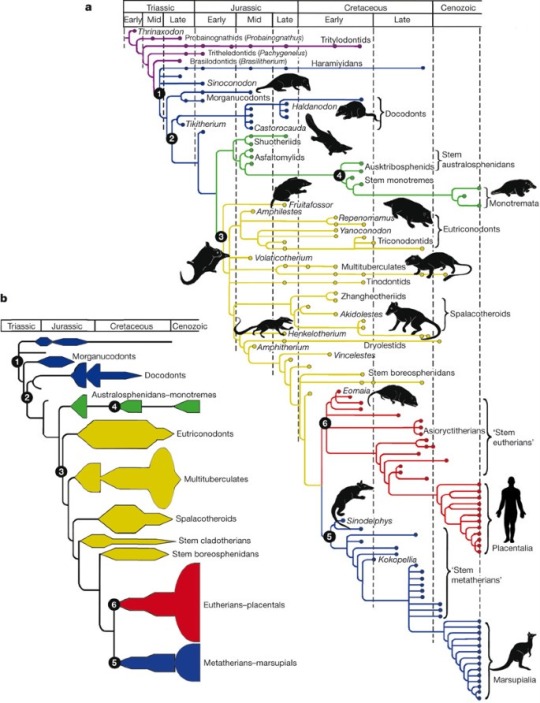

Kimbetopsalis is part of a group of mammals that no longer exists, the multituberculates. These group of animals survived for 130 million years, dying out and disappearing from the fossil record forever in the late Eocene. But don’t be too sad! Multituberculates existed for longer than ANY other group of mammaliforms, including the one that you, I, and every canon character of htf belongs to. The placentals. Today there are only three living groups of crown mammals (aka true mammals): the monotremes (such as the platypus and echidnas), the marsupials (such as kangaroos and opossums), and the placentals.

Now I could go on forever about taxonomies but trust me we’d be here forever. Especially since we are still learning what we can to fully understand mammal evolution. You see, the fossil record for Mesozoic mammals is scarce. Mammals did not get much larger than a badger throughout all the Mesozoic so they did not fossilize easily. Most of what we know about them from that time is from small fragmentary remains, mainly teeth. But despite very few full fossils having been found, we are learning and discovering something new about our ancient mammalian ancestors every day. What we know is constantly changing, but that is the nature of paleontology.

Like I said. We’d be here all day. So let’s move on.

As far as mammals go, Multituberculates like Kimbetopsalis were very common during the Mesozoic. They are easily identifiable by, you guessed it, their teeth.

As you can see, the molars have some crazy cusps on them, also known as “tubercles” hence the name. Their teeth are designed for chomping and crunching all kinds of vegetation. These teeth are very unique among mammals and probably helped them to have a generalist diet which would have aided them greatly in surviving the aftermath of the Chicxulub asteroid impact.

Anyways, Kimbetopsalis is a survivor and a cool little critter, much like Cro is. They lived among the largest land animals to ever walk the earth. They survived the horrifying event that saw an end to the Age of the Reptiles.

I dunno bout yall, but I just think that’s pretty neat.

#happy tree friends#htf#htf cro marmot#Dino-sore days#htf oc#maybe I’ll do a little science corner for all the prehistoric ocs#I love rambling about cool critters#paleo#loretime

85 notes

·

View notes

Text

Spectember Interlude: The Modern Dinosaur Explosion

(Darren Naish over on TetZoo has already done much more extensive coverage on this subject. Check out his series of posts here: part 1 - part 2 - part 3)

The concept of long-extinct prehistoric animals surviving into modern times has been around since at least the mid-1800s, with Jules Verne's 1864 novel Journey to the Center of the Earth being one of the earliest well-known examples. Many many other pieces of media have since explored the concept, especially with the ever-popular non-avian dinosaurs, but often the depictions were of ancient relict stock species virtually unchanged after millions of years.

Two things in the 1980s began to change this idea, however. Obviously Dixon's The New Dinosaurs in 1988 was a major influence – but there was also the infamous dinosauroid.

Emerging from some rather exaggerated ideas in the 1970s about the level of intelligence of relatively "big brained" troodontids, the dinosauroid started as a "thought experiment" in a 1982 article by paleontologist Dale Russell and taxidermist Ron Séguin. Unfortunately the resulting creature was heavily anthropomorphized, and while every element of its anatomy was justified as being the “best” evolutionary solution for a big-brained bipedal creature there was obviously a lot of human-centric unconscious bias in its design.

But it was wildly popularized in media at the time, and incarnations of it have regularly appeared in dinosaur-based pop culture ever since. (And it's also unfortunately become intertwined with antisemitic conspiracy theories, often being used as a visual representation of "lizard people".) Many other hypothetical sapient dinosaurs have appeared in various works over the years, usually also derived from maniraptoran theropods – although exceptions like Star Trek's hadrosaur-descended Voth do also exist.

But getting back to non-sapient dinosaurs… let's talk about The Speculative Dinosaur Project!

Also known as "Specworld" or just "Spec" for short, this was an absolutely massive collaborative online worldbuilding project in the same vein as The New Dinosaurs – a world where the K-Pg asteroid impact never happened, there was no mass extinction, and non-avian dinosaurs continued to dominate global ecosystems.

Started by a July 2001 thread on the Dinosaur Mailing List, Specworld quickly branched off into its own dedicated website. The main contributors and project runners were Daniel Bensen, David Marjanović, Brian Choo, and Mette Aumala, but there was a huge list of other names involved over the years, and many of them went on to become professional paleontologists, biologists, writers, and illustrators.

(Additional contributors included Tim Morris, Clayton Bell, Brett Booth, João Boto, Steve Brusatte, Stacey Burgess, Martin Chavez, Morgan Churchill, Anthony Docimo, Michael Habib, Michael Hanson, Daniel R. Heald, Jonas Holjer, Emile Marc Moacdieh, David Namen, Eric Christopher Ømtvedt, Donald Ridenbaugh, Edgar Segovia, Ville Sinkkonen, Chris Srnka, and Raymond Tobin.)

Presented as the observations of scientists studying a parallel-reality version of Earth, full of the results of 66 million years of divergent evolution, Specworld developed a huge variety of speculative species and ecosystems.

Both avian and non-avian dinosaurs were abundantly represented (as would be expected in something called The Speculative Dinosaur Project!), with creations such as arboreal ornithopods, spiny theropods, huge grazing sail-backed sauropods, ant-eating noasaurs, and the disgusting "dire rhea" and "rectal probe". But groups other than dinosaurs were also given a fair amount of attention, including butt-gilled turtles, ankylosaur-like crocodiles, whale-like squid, burrowing sea cucumbers, skunk-like geckos, bone-crushing platypuses, gliding multituberculates, cookiecutter tadpoles, symbiotic spiders, and terrifyingly toxic plants.

At one point there were plans to eventually publish all this as a physical book, but it never came to fruition.

Specworld's progress began to stall around 2005 or so when Daniel Bensen stepped down from the main editor role, unable to devote enough time to it while in college. Others continued developing Spec for several years afterwards, making revisions to fit in with newer paleontological discoveries that had made some elements of the world outdated, but the original website was abandoned in late 2008 and discussion was moved to a Yahoo Group — which then shut down in 2019 with the closure of that service.

Most of Spec's content is still around, but currently everything seems to be a bit fragmented. Parts are archived on the Speculative Evolution wiki, along with a Russian site featuring a saved English version, and much of the old site can still also be viewed on the Internet Archive Wayback Machine.

Tomorrow: All Yestermorrows and some more aliens.

#spectember 2020#spectember#speculative evolution#specevo#spectember interlude#dinosauroid#the speculative dinosaur project#specworld#long post#antisemitism mention

82 notes

·

View notes

Text

Aepyornithomimus tugrikinensis

By Scott Reid

Etymology: Elephant Bird Mimic

First Described By: Tsogtbaatar et al., 2017

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoromorpha, Maniraptoriformes, Ornithomimosauria, Ornithomimoidea, Ornithomimidae

Status: Extinct

Time and Place: Around 80 million years ago, in the Campanian of the Late Cretaceous

Aepyornithomimus is known from the Tögrögiin Shiree environment of the Djadokhta Formation in Ömnögovi, Mongolia

Physical Description: Aepyornithomimus was a large, derived Ornithomimosaur, much like the later Struthiomimus and Ornithomimus - indicating that these animals were present early on in the Latest Cretaceous. In fact, Aepyornithomimus was somewhat intermediate in form between earlier and later forms, indicating it was somewhat transitional. The size of this dinosaur is unknown, since so little of its skeleton is known, and it could have been anywhere between 2 and 5 meters long. It had unique feet, with fairly slender toes that were weirdly curved compared to close relatives. It also had longer toes than later forms - indicating said transitional nature. Unfortunately, the only parts of this dinosaur known are its legs and feet, so any weirdness elsewhere is currently unknown - though it stands to reason it may have looked different from other Ornithomimosaurs. It probably had a toothless beak, with a small head, long neck, and decently sized tail. As an Ornithomimosaur, Aepyornithomimus would have been covered in feathers all over its body, with wings on its arms (and potential ornamental feathers elsewhere as well).

By Ripley Cook

Diet: It is more likely than not that Aepyornithomimus was an herbivore, as other Ornithomimosaurs were as well.

Behavior: As an Ornithomimosaur, Aepyornithomimus would have been fast moving, primarily using speed to run away from predators rather than other means of defense. It probably would have lived in herds, or at least small groups, exploring its environment and feeding together. It is possible that it may have had adaptations in its mouth to aid in feeding on dry vegetation - since Ornithomimosaurs are usually wet-habitat dwellers, and stick to soft water-based vegetation, Aepyornithomimus is fascinating as a case study into how these dinosaurs adapted to different areas. As a dinosaur, it would have taken care of its young, potentially with the help of the rest of the flock. The wings would have been primarily used in communication - especially sexual and other forms of display. Brighter colors or weirder patterns on those feathers would have been used to indicate the health of the individuals involved.

By José Carlos Cortés

Ecosystem: The Tögrögiin environment was a red, windswept desert, much like how the fossil formation where these animals are found is today. There wasn’t a lot in terms of water, though eventually the ecosystem would transition to a wetter environment during the time of the likes of Deinocheirus et al. There were oases and arroyos, but it would have primarily been very, very dry. This means it would have been filled with tough vegetation, and as such it wasn’t a very herbivore-heavy environment.

This environment was filled with a wide variety of animals - especially lizards. There were Iguanas like Mimeosaurus, Temujinia, Zapsosaurus, Isodontosaurus, Flaviagama, Gurvansaurus, and Dzhadochtosaurus; skinks like Adamisaurus; and monitors like Cherminotus. As for mammals, there were the insectivorous stem-mammals like Barunlestes and Zalambdalestes, and the multituberculate Kryptobaatar.

By Stolp

Of course, Aepyornithomimus wasn’t the only dinosaur here! This place was lousy with the Ceratopsian Protoceratops, which would have been a major competitor with Aepyornithomimus for plant food; and there were also plenty of Pinacosaurus, the Ankylosaur, which would have been able to reach for plants with its long and flexible tongue. Insectivores included Shuvuuia, the Alvarezsaur; and Elsornis, the Opposite Bird. Mahakala, an early raptor, was present as well - and it may or may not have specialized in feeding whatever animals were present at the oases and arroyos that were present, as it seems to have been closely related to the later Goose-Raptor Halszkaraptor. Finally, the main predator of Aepyornithomimus would have been Velociraptor - which was extremely common in this location as well!

Other: Aepyornithomimus, as a potentially transitional Ornithomimosaur, helps to highlight some of the evolution of this group. It is entirely possible that Ornithomimids originated in Asia, before spreading out to North America - or, at least, went through a major portion of their evolution there. Aepyornithomimus also will help to show, as we study it further, how Ornithomimids may have handled the challenge of evolving for drier habitats.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources Under the Cut

Alifanov, V. R. 1989. [New priscagamas (Lacertilia) from the Upper Cretaceous of Mongolia and their systematic position in the Iguania]. Paleontologiceskij Zhurnal 4:73-87.

Alifanov, V. R. 1993. New lizards of the family Macrocephalosauridae (Sauria) from the Upper Cretaceous of Mongolia, critical remarks on the systematics of the Teiidae. Paleontological Journal 27(1):70-90.

Barsbold, R. 1974. Poyedinok dinozavrov [Dueling dinosaurs]. Prioda 1974(2):81-83.

Chiappe, L. M., M. A. Norell, and J. M. Clark. 1998. The skull of a relative of the stem-group bird Mononykus. Nature 392:275-278.

Chiappe, L. M., S. Suzuki, G. J. Dyke, M. Watabe, K. Tsogtbaatar and R. Barsbold. 2007. A new enantiornithine bird from the Late Cretaceous of the Gobi Desert. Journal of Systematic Palaeontology 5(2):193-208.

Chinzorig, T., Y. Kobayashi, K. Tsogtbaatar, P. J. Currie, M. Watabe and R. Barsbold. 2017. First ornithomimid (Theropoda, Ornithomimosauria) from the Upper Cretaceous Djadokhta Formation of Tögrögiin Shiree, Mongolia. Scientific Reports 7(1):5835:1-14.

Fastovsky, D. E., D. B. Weishampel, M. Watabe, R. Barsbold, K. Tsogtbaatar and P. Narmandakh. 2011. A nest of Protoceratops andrewsi (Dinosauria, Ornithischia). Journal of Paleontology 85(6):1035-1041.

Gao, K., and M. A. Norell. 2000. Taxonomic composition and systematics of Late Cretaceous lizard assemblages from Ukhaa Tolgod and adjacent localities, Mongolian Gobi Desert. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 249:1-118.

Gradzinski, R., and T. Jerzykiewicz. 1972. Additional geographical and geological data from the Polish-Mongolian Palaeontological Expeditions. Palaeontologia Polonica 27:17-306.

Kielan-Jaworowska, Z., and R. Barsbold. 1972. Narrative of the Polish-Mongolian Palaeontological Expeditions 1967-1971. Palaeontologia Polonica 27:5-136.

Kielan-Jaworowska, Z., and D. Dashzeveg. 1978. New Late Cretaceous mammal locality in Mongolia and a description of a new multituberculate. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 23(2):115-128.

Kielan-Jaworowska, Z., and B. A. Trofimov. 1981. A new occurence of Late Cretaceous eutherian mammal Zalambdalestes. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 26(1):3-7.

Kielan-Jaworowska, Z. 1984. Evolution of the therian mammals in the Late Cretaceous of Asia. Part V. Skull structure in Zalambdalestidae. Palaeontologia Polonica 46:107-117.

Kielan-Jaworowska, Z., and J. H. Hurum. 1997. Djadochtatheria - a new suborder of multituberculate mammals. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 42(2):201-242.

Kurzanov, S. M. 1972. Sexual dimorphism in protoceratopsians. Paleontological Journal 1972(1):91-97.

Jerzykiewicz, T., P. J. Currie, D. A. Eberth, P. A. Johnston, E. H. Koster and J. J. Zheng. 1994. Djadokha Formation correlative strata in Chinese Inner Mongolia: an overview of the stratigraphy, sedimentary geology, and paleontology and comparisons with the type locality in the pre-Altai Gobi. Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 39(10-11):2180-2195.

Mikhailov, K. E. 1991. Classification of fossil eggshells of amniotic vertebrates. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 36(2):193-238.

Mikhailov, K. 1994. Eggs of theropods and protoceratopsian dinosaurs from the Cretaceous of Mongolia and Kazakhstan. Paleontological Journal 28:101-120.

Mikhailov, K. E. 2000. Eggs and eggshells of dinosaurs and birds from the Cretaceous of Mongolia. In M. J. Benton, M. A. Shishkin, D. M. Unwin, & E N. Kurichkin (eds.), The Age of Dinosaurs in Russia and Mongolia 560-572.

Nikoloff, I., and F. v. Huene. 1966. Neue Vertebratenfunde in der Wüste Gobi. Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie Monatshefte 11:691-694.

Norell, M. A., and P. J. Makovicky. 1997. Important features of the dromaeosaur skeleton: information from a new specimen. American Museum Novitates 3215:1-28.

Norell, M. A., and P. J. Makovicky. 1999. Important features of the dromaeosaur skeleton II: information from newly collected specimens of Velociraptor mongoliensis. American Museum Novitates 3282:1-45.

Perle, A., M. A. Norell, L. M. Chiappe and J. M. Clark. 1993. Flightless bird from the Cretaceous of Mongolia. Nature 362:623-626.

Sabath, K. 1991. Upper Cretaceous amniotic eggs from the Gobi Desert. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 36(2):151-192.

Saneyoshi, M., M. Watabe, T. Tsubamoto, K. Tsogtbaatar, T. Chinzorig and S. Suzuki. 2010. Report of the HMNS-MPC Joint Paleontological Expedition in 2007. Hayashibara Museum of Natural Sciences Research Bulletin 3:19-28.

Suzuki, S., and M. Watabe. 2000. Report on the Japan–Mongolia Joint Paleontological Expedition to the Gobi desert, 1998. Hayashibara Museum of Natural Sciences Research Bulletin 1:83-98.

Turner, A. H., D. Pol, J. A. Clarke, G. M. Erickson, and M. A. Norell. 2007. A basal dromaeosaurid and size evolution preceding avian flight. Science 317:1378-1381.

Watabe, M., and D. B. Weishampel. 1994. Results of Hayashibara Museum of Natural Sciences–Institute of Geology, Academy of Sciences of Mongolia Joint Paleontological Expedition to the Gobi Desert in 1993. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 14(3, suppl.):51A.

Watabe, M., and S. Suzuki. 2000. Cretaceous fossil localities and a list of fossils collected by the Hayashibara Museum of Natural Sciences and Mongolian Paleontological Center Joint Paleontological Expedition (JMJPE) from 1993 through 1998. Hayashibara Museum of Natural Sciences Research Bulletin 1:99-108.

Watabe, W., and S. Suzuki. 2000. Report on the Japan–Mongolia Joint Paleontological Expedition to the Gobi desert, 1994. Hayashibara Museum of Natural Sciences Research Bulletin 1:30-44.

Watabe, M., and K. Tsogtbaatar. 2004. Report on the Japan–Mongolia Joint Paleontological Expedition to the Gobi desert, 2000. Hayashibara Museum of Natural Sciences Research Bulletin 2:45-67.

Watabe, M., and D. E. Fastovsky. 2007. Mass burial event of Pinacosaurus (Ankylosauria, Dinosauria) in Alag Teg, a fluvial facies of the Djadokhta Formation (Late Cretaceous), Gobi Desert, Mongolia. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 27(3, suppl.):163A.

Wible, J. R., M. J. Novacek, and G. W. Rougier. 2004. New data on the skull and dentition of the Mongolia Late Cretaceous eutherian mammal Zalabdalestes. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 281:1-144.

#Aepyornithomimus tugrikinensis#Aepyornithomimus#Ornithomimosaur#Dinosaur#Palaeoblr#Factfile#Cretaceous#Eurasia#Theropod Thursday#Herbivore#paleontology#prehistory#prehistoric life#dinosaurs#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature

197 notes

·

View notes

Text

Scientists just found the earliest evidence of social behaviour in mammals

https://sciencespies.com/nature/scientists-just-found-the-earliest-evidence-of-social-behaviour-in-mammals/

Scientists just found the earliest evidence of social behaviour in mammals

How long have mammals been social creatures? At least since the Late Cretaceous part of the dinosaur age, according to a new study, which puts back the earliest evidence of the behaviour by some 10 million years.

Studying fossils of the small rodent Filikomys primaevus (meaning “youthful, friendly mouse”) dated to around 75.5 million years ago, palaeontologists have discovered evidence of the animals hanging out and living in groups.

We’re not just talking about adults bringing up their young – the site at Egg Mountain in western Montana shows adults and younger animals choosing to burrow and nest together, perhaps some of the first such social activity in history.

“It is really powerful, I think, to see just how deeply rooted social interactions are in mammals,” says palaeontologist Luke Weaver, from the University of Washington.

“Because humans are such social animals, we tend to think that sociality is somehow unique to us, or at least to our close evolutionary relatives, but now we can see that social behaviour goes way further back in the mammalian family tree.”

“Multituberculates are one of the most ancient mammal groups, and they’ve been extinct for 35 million years, yet in the Late Cretaceous they were apparently interacting in groups similar to what you would see in modern-day ground squirrels.”

A lifelike reconstruction of F. primaevus. (Misaki Ouchida)

It had been thought that this kind of deliberate social behaviour developed after the extinction of the dinosaurs 66 million years ago, and primarily in the Placentalia class of mammals that humans belong to.

Not so, according to these fossils – the type of rock they were found in, how well they were preserved, and the traits that F. primaevus share with modern-day burrowing animals all suggest that these ancient creatures were happy chilling out together.

The researchers couldn’t find any evidence of bite marks on the fossils, so it’s unlikely that predators put these animals together, and if they’d been moved by the flow of a river then the fossils wouldn’t be as complete as they are.

A block of fossils analysed from the Egg Mountain. (Luke Weaver)

“These fossils are game changers,” says palaeontologist Gregory Wilson Mantilla. “As palaeontologists working to reconstruct the biology of mammals from this time period, we’re usually stuck staring at individual teeth and maybe a jaw that rolled down a river, but here we have multiple, near complete skulls and skeletons preserved in the exact place where the animals lived.

“We can now credibly look at how mammals really interacted with dinosaurs and other animals that lived at this time.”

Artistic reconstruction of a social group of F. primaevus in a burrow. (Misaki Ouchida)

Today, around half of Placentalia or placental mammals socialise in this way (global pandemics permitting), and the behaviour is also seen in some marsupials such as kangaroos.

Humans hang out together for all kinds of reasons beyond the business of reproducing and bringing up children, but in evolutionary terms the behaviour can help in avoiding predators, sharing resources, and keeping warm.

Now it seems that behaviour started a lot earlier than we thought. As much of the world continues to grapple with restrictions on meeting up in groups, it’s a reminder that we’re social animals at heart – something the research team is well aware of.

“It was crazy finishing up this paper right as the stay-at-home orders were going into effect – here we all are trying our best to socially distance and isolate, and I’m writing about how mammals were socially interacting way back when dinosaurs were still roaming the Earth!” says Weaver.

The research has been published in Nature Ecology & Evolution.

#Nature

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

While you wait for Hamster's Paradise to come back, may I suggest you take a look at my own Multituberculate Earth?

Ooohooo absolutely!!

0 notes

Text

Multituberculate Earth: Messel Pit

Messelboffius atraxa, a red-kangaroo sized hopper from the Eocene of Europe, coupled with its muscular anatomy. By Dr Spooky.

The Messel Pit is a world renowed (being even a UNESCO heritage site) fossil site in Germany, dating to the Lutetian stage of the Eocene. It represents a lake environment associated with a volcano, the latter likely providing toxic gases that routinely killed the local fauna (such events have been compared to our timeline’s Lake Nyos incidents). The lake likewise had an anoxic layer preventing normal decomposition by bacteria; as a result, animals that fell into the lake’s deeper regions became exceptionally well preserved. Soft tissues from hair to organs are known, all captured within thin limestome slabs.

The climate in the region was tropical; in this timeline, perhaps even hotter thanks to an extended thermal maximum. Tropical rainforests covered what was once an island continent, as Europe was isolated from the other landmasses. This allowed it to develop an unique fauna with elements from both Laurasia and Gondwanna.

Taeniolabidids were the largest land mammals in the continent, though european forms were mostly island dwarfs; the local Gauliolabis messelnienses, the very largest land mammal in the site, rarely surpassed 120 kg. It was a semiaquatic herbivore, though more closely related to north american giants than to other aquatic forms. The second largest mammal was Messelboffius atraxa, a boffiid, about as large as a red kangaroo at 47 kg, and similarly a hopper much like most of its relatives.

No, the largest land animal was not a mammal but rather the famous flightless bird Gastornis. Europe, much like in our timeline, had birds as the largest land animals, making it rather similar to Madagascar in our timeline’s Pleistocene, being another island continent ruled by giant birds. Terrestrial crocodilians like Bergisuchus and Boverisuchus were the apex predators on land, with more familiar forms ruling the waters. It was truly a reminder of the age of the dinosaurs.

Still, some mammals packed a punch. Celtoptilodus giganteus was a bobcat sized ptilodontoid and the largest mammalian carnivore in the region, followed closely by the symmetrodont Taranomamus horridus, a more robust and badger like animal. Ptilodontoids and symmetrodonts occupied the main carnivorous and omnivorous niches among mammals, and though several species were small (particularly symmetrodonts) their menagerie was vast. Another common group of omnivores were the eucosmodontids; though many forms were terrestrial mouse to cat sized species, the Messel Pit preserves two genera of flyers: Khusuurbaatar, with wings supported by its styliform, and Plummobaatar gaulica, with wings composed of feather-like hairs.

Khusuurbaatar elegans by Dave García. One of various flying euscosmodontid lineages, this one lasted across the Eocene, with fossils found in Asia, Europe, North America, Australia and Antarctica. It was a genus of fast aerial insectivores, this species being the largest known with a wingspan of 60 centimeters.

Another flyer was the ptilodontoid Pteroectypodus falco, which also occured in contemporary sites in North America. This diversity of flying mammals rivals our timeline’s bat diversity, of which several species are known from the Messel Pit.

Pteroectypodus falco by Diego Ortega Anatol.

Among herbivorous mammals, the most common were the gondwanathere feruglitheriids, which likely arrived to Europe from North America (and in turn from South America) in the Paleocene. They and the boffiids compromised the main herbivorous guilds: the ferugliotheriids ranged from mouse sized to 50 kilo large forms, from burrowers to sloth-like tree climbers, while boffiids were more typical hoppers, ranging from jerboa sized to the aforementioned Messelboffius atraxa.

Microcosmodontids were smaller in Europe than in other land masses, the largest being the mole-sized burrower Velesotherium occidentalis. The eucosmodontid Thylacolutra messeliensis occupied an aquatic forager niche akin to an otter, while the ptilodontoid Amaxillodens plagiaulacoides lost its upper dentition, relying on its plagiaulacoid teeth and robust claws to open termite nests.

The unique fauna of the Messel Pit is a slice in time of when Europe was allowed to develop its fauna in isolation. With the Grand Coupure, climatic changes and competition from arrivals from Asia ended this strange world. But for almost twenty million years, the fauna of Europe thrived in their tropical island paradise.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

@ fellow neurodivergents tell me fun facts about your hyperfixations. I will start. Thor and Zeus and Indra trace their roots to the same indo-european god. The oldest fairytale pre-dates Latin, as in the language. Millet, not rice, was the historic staple food of northern China. The mammalian genus with the longest fossil record on earth are the extinct multituberculates, which existed for approximately 166-183 million years. For reference, that's more than 2x as long from the extinction of the non-avian dinosaurs to the modern day.

#actuallyadhd#actuallyautistic#actuallyocd#actuallyobsessive#today has been Trying and i want some positivity#whispers

232 notes

·

View notes

Text

New picture for Illyriolestes piscimimus: https://multituberculateearth.wordpress.com/2022/10/05/iberia-the-tip-of-the-world/ https://multituberculateearth.wordpress.com/2022/04/03/mammals-at-sea/ https://multituberculateearth.wordpress.com/2022/04/02/dryolestoidea-the-other-guys/

#multituberculate earth#dryolestida#dryolestoidea#dryolestidae#dryolestoid#speculative zoology#speculative biology#speculative evolution#spec evo

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Multituberculate Earth: Dryolestoidea/Meridiolestida

(As with all animal pages so far, this only goes so far into the Miocene… for now)

Xenotamandua allocaellusfrom the Paleocene of Bolivia.By pale.relics.

The thesis of this project is a world where multituberculates rose to dominance instead of placental and marsupial mammals. In doing so, I uplifted some other groups as a butterfly effect, but no group stands so starkly as dryolestoids, a completely unrelated lineage of mammals sharing equal power in this timeline. This is because dryolestoids, alongside multituberculates, likely suppressed therian expansion until their decline, so it makes so logical sense that whatever didn’t cause the downfall of multtuberculates also allowed dryolestoids to keep on thriving.

Plus, they’re fun as well.

Dryolestoids are in many respects similar to therian mammals and likely close relatives, differing primarily in some cranial aspects like a well developed premaxilla, double canine roots, slower tooth eruption patterns (indicative of longer lifespans compared to therian mammals) and the presence of “eupantothere” molars, a sort of intermediate between the triconodont teeth of mammals like eutriconodonts and the tribosphenic teeth of therians. Unlike multituberculates they don’t have a palinal stroke, instead mostly chewing “normally”, so they lack many of their pecularities. Like with multituberculates phylogenetic bracketing suggests they probably had a cloaca, internal testicles and bifurcated penis like modern monotremes and marsupials.

Dryolestoids first appear in the fossil reccord in the Mid to Late Jurassic, roughly at the same time as early therians from which they split likely shortly before. They were common in the Late Jurassic and Early Cretaceous of Europe, but disappear from the nothern continents around the Mid-Cretaceous, likely due to ecological turnovers caused by the spread of flowering plants. This was no problem, however, as some had made it to Africa and then South America, where they not only survived but actually became the dominant mammals alongside gondwanatheres. Most of these Late Cretaceous forms belong to the group Meridiolestida, but a few basal forms continued to survive until the KT event.

Cretaceous forms were rather diverse, including insectivores (some of which possibly sengi-like) and large herbivores and omnivores. The KT event seems to have obliterated a large portion of their diversity, but the Paleocene saw some diversity in South America and Antarctica, culminating in the giant herbivore Peligrotherium tropicalis, the largest south american mammal of its time and likely functionally similar to the black rhino. Afterwards their fossil reccord is much scarcer, with an Eocene Antarctic tooth and the Miocene mole-Like Necrolestes, ending their long reign in a strange little note.

Suffice to say, in this timeline they do not decline, and keep on diversifying across South America, Antarctica and Australia, even as the landmasses break apart. Though a few new faces like ptilodontoideans have shown up in their turf, for the most part their reign continued uninterrupted even across major events like the PETM and Grand Coupure, ranging from small insectivores to some of the largest mammals of this timeline.

Leonardidae

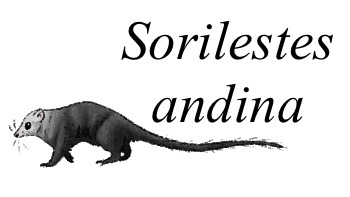

Sorilestes andinafrom the Paleocene of Bolivia.By pale.relics.

By far the most diverse lineage, leonardids first occur in the Cretaceous in the eponymous genus Leonardus and the closely related Cronopio, the latter in particular occasionally well known for its long canines, resembling Scrat from the Ice Age movies. They are ancestral to the Cenozoic mole-like Necrolestidae, so Leonardidae is treated here as paraphyletic in relation to that clade. The clade Brandoniidae is a controversial assemblage which may or may not be valid as it is known only from teeth that might belong to leonardids or mesungulatids; henceforth, putative members are treated as part of this group.

Fo gaxie, an animal used to play with the controversy of Brandoniidae. From the Paleocene of Bolivia, by pale.relics, you know the drill.

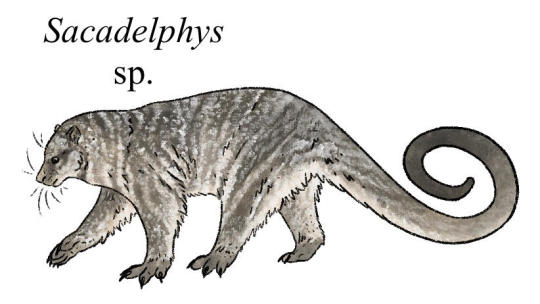

Leonardids occupied small omnivorous and insectivorous niches in the Cretaceous and ultimately that’s how they ended in our timeline (if as highly unusual mole mimics), but in this timeline they are a very diverse bunch, if tending toards carnivorous niches. They include also a variety of forms convergent with our didelphids (fittingly the clade Pseudodidelphidae), sengi-like runners (the aforementioned ‘brandoniids’), anteater-like forms and a few large carnivores. Their diversity increased in particular during the Miocene, as their larger mesungulatid cousins declined.

Sacadelphys, a pseudodidelphid. From the Paleocene of Bolivia, by pale.relics

Two particular clades went on to have a global success beyond the southern continents: Necrolestidae and Allochiropteridae:

The former started off as burrowing mole analogues as in our timeline. However, here they took to the seas in the Late Eocene genus Camahueto, spreading across the world’s oceans in the Oligocene. Propelled by four flippers like mammalian pliosaurs, they typically range at about porpoise size (though a few forms grew to up to 6 meters and as small as desman size in freshwater habitats), and occupy a variety of niches taken in our timeline by large fish, cetaceans and seals, from hunters of squids, shrimps and the remaining fish to durophagists plucking molluscs from the sea bed to macropredators hunting other marine mammals.

The latter took to the skies in wings rather similar to those of true bats from our timeline, their similarity earning them their name (“different hand wings”). The first forms evolved in Antarctica as semi-terrestrial foragers like our mystacine bats, but quickly flew far and wide across all major continents, some forms becoming flying-fox like frugivores and others hawking insectivores. They largely remain small sized compared to other contemporary flying mammals, rarely exceeding two meter wingspans.

The allochiropterid Chimil kaslem, from the Oligocene of Antarctica. Here depicted with speculative structural colours like those of mandrill faces, exhibitting for a potential mate. By hodarinundu

With generally dog-like faces, leonardids offer at least a hint of the familiar in this strange world.

Mesungulatidae

Allqu uyam, a relatively conservative mesungulatid. From the Paleocene of Bolivia, by pale.relics

Mesungulatids already started off big in the Cretaceous as formerly shown, and so it is no surprise that in this timeline they quickly diversified as megafaunal species. Some forms resemble their Cretaceous ancestors, occupying raccoon or skunk-like niches while leonardids and notoptilodontoideans crowd them at all sides.

But it didn’t take long for change to came in drastic aways. One lineage related to Peligrotherium (hence Peligrotheriidae) grew rapidly, already reaching the 3 ton threshold by the Paleocene, and only increasing in size across the Eocene and Oligocene with some forms rivalling our indricotheres and elephants as largest land mammals of all time. Some of these gigantic herbivores developed long necks, allowing them to literally tower above the gondwanathere competition, though peligrotheriids tend to be more mixed feeders compared to those hard-plant specialists. Unlike them, they have a more lateral and orthal chewing style functionally similar to that of rhinos, which also allows them to extract nutrients from plants differently. Others developed powerful canine tusks, used both for sexual selection as well as to dig out tubers and roots. Giant herds of peligrotheriids cross South America, Antarctica and Australia, true heirs to the sauropods of the Mesozoic.

Baroauchenia canifacis, here portrayed as a Falkor cosplayer but potentially hairless since its supposed to be a fossil species and all.From the Paleocene of Bolivia, by pale.relics

By contrast, some mesungulatids went in the complete opposite direction and became the mammalian apex predators of the southern continents. Some of these animals, vaguely cat or fossa-like, used their clawed forelimbs to wrestle with their prey until a fatal bite was strategically placed. Others, more akin to dogs and hyenas, developed crushing and terrifying jaws, running after their prey. Such animals might represent several different lineages, that took to a more carnivorous lifestyle as gondwanatheres and peligrotheriids expanded, turning competition into food. Developing carnassial-like teeth to cut meat, they quickly turned to hypercarnivory with few omnivorous forms, which has served them well for now but might become a liability when biomes become more unstable in the future.

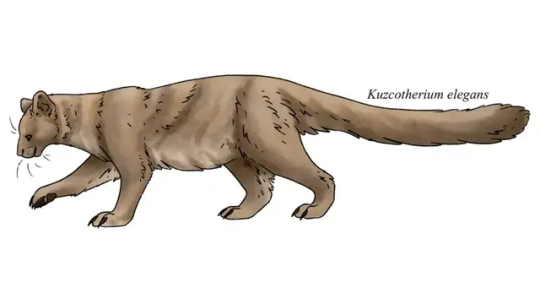

Kuzcotherium elegans, a carnivorous form related to Allqu uyam.From the Paleocene of Bolivia, by pale.relics

Be them carnivores or omnivores, mesungulatids are some of the most impressive mammals currently alive, but as Antarctica cools and South America and Australia dry they might have to give up their throne soon enough. And indeed, across the Miocene, mesungulatids, both herbivorous and carnivorous, have started to decline…

#multituberculate earth#dryolestida#dryolestidae#dryolestoidea#meridiolestida#spec evo#speculative biology#speculative zoology#speculative evolution

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Feel too lazy to post it fully here, webarchived it

2 notes

·

View notes