#localize your virtue

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

#fr tho#projection#politics is the opium of the asses#politics#complaining#making personal probs into causes#narrativespeak#evasion#denial#examine your own shit before blaming society#punkass route#psychobabble#life is hard#wacktivism#empty activism#activism#pseudo religion#localize your virtue#do real things#come correct#own your own bullshit#you are the cause#take responsibility#hiding behind issues#existential cowardice#culture#real talk#truth#weak#pseudo intellectualism

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

so many people on this site are competing to win the award for Best, Most Moral Person that they turn into unlikable witch hunters who make being around them actively unenjoyable. sure you can give me a list of the top ten worst zionists in hollywood but can you give me a list of pro palestine organizers in your area. you can tell me that you think the rocky horror picture show is transphobic but can you tell me local elections you've voted in to keep anti-trans legislators out of office. can you tell me one meaningful thing you have participated in outside um actuallying people in the internet. can you.

#GOD. LOG OFF!!!!!!!#DO GOOD IN YOUR COMMUNITY!!#donate to a food bank see a local drag show attend a protest get a library card.#any of these things are more meaningful than virtue signalling on tumblr dot com

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

You can't be an ally to anyone (LGBT+, religion, race, etc) and then say a group of people "should die".

#this is about a local shop owner who claimed one person had 'fake illnesses' and said someone else was 'Overreacting' bc that person said th#that they're parents were strict as fuck... like#you fly the Progress flag but then you belittle and invalidate others? who tf are you?#a group of backwoods Christians bullied you? so you say that ALL Christians should die?*#*I don't condone any kind of bullying and your suffering is valid but like... get a grip*#its kind of a red flag when someone wishes another human being would die... Yikes#no human gets to decide who lives and who dies... and no one is more deserving of life than someone else#people should fave consequences for their actions absolutely... but be for real#just because you're part of a marginalized group* it doesn't mean that you are above morality and you certainly don't get to tell ppl to die#*im afab. im trans. im ex-christian. and im pan-ace... I belong to one of the most hated groups of the modern age**#*(not trying to virtue signal... Im just saying that I KNOW what it feels like to have people want you erased from existence)#big yikes#hot take#i understand that freedom most likely will not come peacefully... but I also know it isn't right to wish death upon anyone#the two ideologies can coexist

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

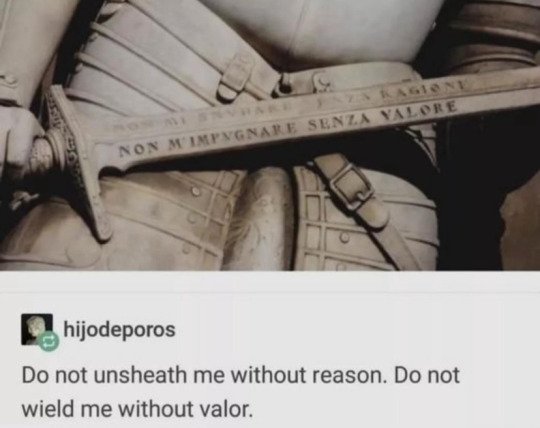

Sexiest thing I’ve ever heard tbh

So y’all know the classic edge trope of “my blade cannot be sheathed until it has tasted blood”? What if a magic sword that has that requirement, except it’s sort of inverted. A sword that, instead of being inhabited by an evil spirit which once awakened cannot be lulled back to sleep except by blood sacrifice, was inhabited by a benevolent spirit who would not allow the sword to be drawn unless bloodshed were the only possible solution. A sword whose power could never be misused because it would only allow itself to be used in situations where it was justified. What about a Paladin who spends their entire journey fighting with a sheathed sword, incapacitating but never killing or maiming. The party believes that the Paladin has taken an oath of no killing, until they face the big villain. And it is in that moment, and that moment alone, that the sword will allow itself to be drawn.

Idk, this image set my mindwheels a-turning.

But do y’all see the vision?

#your local AroAce#at the safari park#zoo#whatever#story ideas#do not unsheathe me without reason#there’s something nice in the idea of power that does not corrupt#not through any virtue of the wielder#but because the power itself will not allow it

52K notes

·

View notes

Text

During the 2008 recession, my aunt lost her job. Her, her partner, and my three cousins moved across the country to stay with us while they got back on their feet. My house turned from a family of four to a family of nine overnight, complete with three dogs and five cats between us.

It took a few years for them to get a place of their own, but after a few rentals and apartments, they now own a split level ranch in a town nearby. I’ve lost track of how many coworkers and friends have stayed with them when they were in a tight spot. A mother and son getting out of an abusive relationship, a divorcee trying to stay local for his kids while they work out a custody agreement, you name it. My aunt and uncle knew first hand what that kindness meant, and always find space for someone who needed it, the way my parents had for them.

That same aunt and uncle visited me in [redacted] city last year. They are prolific drinkers, so we spent most of the day bar hopping. As we wandered the city, any time we passed a homeless person, my uncle would pull out a fresh cigarette and ask them if they had a light. Regardless of if they had a lighter on hand or not, he offered them a few bucks in exchange, which he explained to me after was because he felt it would be easier for them to accept in exchange for a service, no matter how small.

I work for a company that produces a lot of fabric waste. Every few weeks, I bring two big black trash bags full of discarded material over to a woman who works down the hall. She distributes them to local churches, quilting clubs, and teachers who can use them for crafts. She’s currently in the process of working with our building to set up a recycling program for the smaller pieces of fabric that are harder to find use for.

One of my best friends gives monthly donations to four or five local organizations. She’s fortunate enough to have a tech job that gives her a good salary, and she knows that a recurring donation is more valuable to a non-profit because they can rely on that money month after month, and can plan ways to stretch that dollar for maximum impact. One of those organizations is a native plant trust, and once she’s out of her apartment complex and in a home with a yard, she has plans to convert it into a haven of local flora.

My partner works for a company that is working to help regulate crypto and hold the current bad actors in the space accountable for their actions. We unfortunately live in a time where technology develops far too fast for bureaucracy to keep up with, but just because people use a technology for ill gain doesn’t mean the technology itself is bad. The blockchain is something that she finds fascinating and powerful, and she is using her degree and her expertise to turn it into a tool for good.

I knew someone who always had a bag of treats in their purse, on the odd chance they came across a stray cat or dog, they had something to offer them.

I follow artists who post about every local election they know of, because they know their platform gives them more reach than the average person, and that they can leverage that platform to encourage people to vote in elections that get less attention, but in many ways have more impact on the direction our country is going to go.

All of this to say, there’s more than one way to do good in the world. Social media leads us to believe that the loudest, the most vocal, the most prolific poster is the most virtuous, but they are only a piece of the puzzle. (And if virtue for virtues sake is your end goal, you’ve already lost, but that’s a different post). Community is built of people leveraging their privileges to help those without them. We need people doing all of those things and more, because no individual can or should do all of it. You would be stretched too thin, your efforts valiant, but less effective in your ambition.

None of this is to encourage inaction. Identify your unique strengths, skills, and privileges, and put them to use. Determine what causes are important to you, and commit to doing what you can to help them. Collective action is how change is made, but don’t forget that we need diversity in actions taken.

22K notes

·

View notes

Note

i just want a hug from Hotch so bad!!! 😭🤧 can i request a sunshiney and oblivious reader and Hotch hugging and sharing his coat bc she forgot hers and insists it’s too cold for Hotch to just give her his, so obviously the smartest solution is just to share hehehe? 🥰 and ofc the team makes fun of him bc he’s a huge softie for her!!! ❤️🍯

tysm! i absolutely adore your fics!

survival instincts

AWWWW cw; fem bau sunshine!reader, established relationship, playful banter and fluff <3

Patience was a virtue, one you felt as if you exhibited thoroughly. You were easygoing, positive, sensible when it came to others.

So waiting for the local PD to wrap up their analysis of the crime scene would've been fine, if the temperature hadn't been plummeting by the minute.

And you hadn't foolishly left your coat back at the precinct.

Your nose was numbing, you were beginning to shiver in place; the sun wasn't there to provide any supplemental warmth. The clouds were a menacing, gloomy gray that was darkening, with the tiniest bit of gleam coming from behind. In an hour or so, night would be upon you.

You breathed out, watching your breath fan out in a cloud, hoping it would entertain you enough to stop thinking about your growing frigidness. Your gaze furthered past it as it expanded, landing on Aaron and his warm coat.

The visual caused you to think about the earlier morning, warm in the comfort of bed. Laid beside Aaron, enveloped in the weak comforter the hotel had to offer - which didn't matter with the warmth he consistently provided. You would've done anything to go back to the moment. And so, a plan to remedy your problem quickly developed in your mind.

"Aaron." You whisper-yelled, despite the fact he was a mere foot away. His eyes were locked forward, without a doubt ensuring the crime scene wasn't being compromised by the officers poking around.

His brown eyes found yours, "Hm?"

"I'm cold." You whined with a playful pout, your eyes begging for help.

"Then maybe you should've remembered a coat." He teased, hands buried in his coat pockets.

You quipped by use of a cheeky expression in return. You gazed at the asphalt below, the wind whipping your hair around your face. You mumbled a feigned, solemn, "Maybe."

He began prying his coat off his shoulders, "Here, let me-"

"No silly. Then you'll be cold. And we can't have that, can we?" You rolled your eyes, bringing yourself in front of him. You slid your arms around his middle, underneath his coat - thankfully unbuttoned - and embracing him tightly.

The long coat he wore was loose enough to shield your sides, provided mild coverage from the wind, and whatever was left was made up from his body heat. Immediately, you began regaining warmth head to toe.

"Sweetheart, this isn't very convenient." You felt his chuckle rumble through him, gently jostling your head as it rest on his chest. But still his arms wrapped around you, holding you close. "Or professional, given the circumstances."

"This is merely a survival technique." You mumbled insistently into his shirt, a smile tugging at your lips. "Close contact preserves body heat. I'm just doing what it takes to survive. I don't think the Bureau would be very happy if one of their agents froze to death while on the job."

Aaron hummed at the stretch of your proposition. "Well, I think the Bureau would presume their agents would have the intention to bring a coat."

You scoffed lightly, causing him to laugh again. "Well, do you have a better idea?"

"Yeah, you could just wear my-"

"I already told you no. And my supporting evidence," You insisted, your voice laced an almost, mischievous wisdom. "You're just getting over a cold, which won't be returning if there's anything I can do about it. Plus there's a reason I call you a furnace. This, you," You tightened your hold on his as if to prove your point. "Can supply me with more warmth than a coat ever could."

He laughed softly. Again it was leaning more on the rigid side, conscious of any wandering eyes. He did, however, sneak a quick kiss to the top of your head. "If you say so."

You closed your eyes, releasing a content sigh and savoring the warmth, as well as Aaron's contact. One of his hands softly brushed a spot along your back. However, your shared moment of solitude was interrupted by the sound of approaching footsteps.

"Aww, can I join?" Derek gushed, shit-eating grin on his face. JJ had an equally as smug grin as she trailed up from behind him.

You shot him a look, one that read ha-ha funny as well as amused, while Aaron subtly narrowed his eyes. He then turned his head in the opposite direction, his cheek resting against your head comfortably.

"Cuddling on the job, huh? What would Strauss have to say about this?" Morgan continued to tease, and Dave even took out his phone, discreetly snapping a picture.

"He's just doing his job. Looking out for a team member by preventing potential frostbite. Or hypothermia, even." You arched an eyebrow playfully, your fingers clutching onto the fabric of Aaron's shirt underneath his coat. "And there's nothing wrong with that."

#aaron hotchner x reader#aaron hotchner#aaron hotchner fluff#aaron hotchner x you#aaron hotchner x fem!reader#aaron hotch x reader#aaron hotchner imagine#criminal minds#criminal minds x reader#criminal minds x you#criminal minds drabble#aaron hotchner drabble#criminal minds imagine#criminal minds fanfiction#hotch imagine#criminal minds x fem!reader

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Temperance (1/3)

pairing: wanda maximoff x female!reader plot: Your best friend Kate convinced you to do charity work in Sokovia with some of your old classmates, including your former bully Vision and his girlfriend Wanda Maximoff, who you inconveniently took too much of a liking in. warnings: 18+ !! minors dni. wanda is with vision... also, suggestive content I guess word count: 1115

Patience is a virtue. Patience is the solution. These have been your only thoughts for days now. From a self-imposed affirmation to a recurring echo in your head, this reminder is all you had to get through the situation at hand. What else could you do? Keep trying to ignore your desire? The craving that has kept you awake for days and nights?

The thing is, you may be able to trick your brain for a while. Convince yourself that the way her nose wrinkles when she grins doesn't do anything to you. That the way her middle and ring finger draw the same patterns over and over again on the pages of her book whenever she is deep in thought, doesn't stir something inside of you. That the muffled moans coming from her and Vision's room at night don't bother you. Your brain has managed to lie to itself for a long time, but you can no longer ignore what Wanda is doing to you. So instead of denying your feelings, you decided that you have to sit through them. Until you can finally leave this place.

You weren't planning on pining after your old classmate's girlfriend, but here you were. Miles away from home, locked up with the constant reminder that you can never be with Wanda the way you want to. Originally, the three months in Sokovia were supposed to fulfill you. You just wanted to take care of the local street dogs with your best friend Kate. Do something good. That was it.

“Come on y/n, you've always had a heart for street animals,” your best friend said to you at the time. Back then she turned up at your door without a warning and told you about this great trip Vision had planned.

“Kate, I barely got anything done last semester. I can't waste another one. Besides, my boss never gives me that long of a vacation.”

You knew Kate wouldn't leave your apartment until you said yes. You could tell by the way her eyes were gleaming. How she slightly bend over the table you were sitting at, her gaze not leaving you for one second. Of course, the whole thing is much easier for Kate. Her mother is filthy rich. Kate can basically do whatever she wants. She could disappear for one year, travel the world with money she didn't earn and wouldn't have to worry about her life back home for one moment. You don't have that luxury.

“Think about it. First of all, you do something that fulfills you. Besides, I know you y/n. You haven't wanted to work in that rancid bakery for months. We'll find something new for you afterwards. Not to mention that volunteering to help street dogs for three months looks great on your CV. Plus: I heard Vision rented a mansion”

Vision. The name alone triggered something in you. Vision is not only the son of the famous billionaire Tony Stark, but also a giant asshole. Before Vision knew you were friends with Kate, he took every opportunity to trigger you in some way. Like standing in front of your locker with his group of followers for no reason, just so you couldn't get to it. The worst thing he ever did was probably when he stole your notebook and read out loud in class what you had written about your former classmate Natasha. Some cheesy and cringe poem you managed to suppress from your memories. From that day on, it wasn't just the whole school that knew you liked women. You also were never able to look Natasha in the eye again. But Vision somehow always managed to come out of it okay. His reputation was disgustingly squeaky clean.

“It's so weird imagining Vision doing something voluntarily that doesn't serve only himself. Are you sure he isn't just joking?,” you had asked back then.

“I think he has really changed since high school. Besides, his girlfriend is originally from Sokovia and I think it was her idea? I don't know for sure. But please, y/n, join me. I'd do anything to spend more than an hour a week with my best friend. And this is a once in a lifetime opportunity! Vision specifically asked if you want to join.”

You've never been able to deny Kate a wish. But also, it's never led you into such a miserable situation before. So this is where you were. In a villa far too grand for it to feel like a prison. Besides Vision, Wanda and Kate, there were two other old classmates; Steve and Bucky. Living together turned out to be easier than you thought, especially considering the fact that Vision was there. But your feelings for Wanda kept causing you problems. Whenever the redhead came near you, you started to stumble over your words. One long look alone could throw you completely off balance. But it was even worse when she smiled at you. When she listened to you and her head slightly tilted at the same time. Or when you were cooking and she suddenly appeared behind you, her hand softly placed around your waist and her head set down on your shoulder.

“What are you blessing us with this evening?,” she inquired with an almost teasing tone in her voice.

Before you were able to even articulate anything, she took her free hand, slid it along your arm and took the wooden spoon out of your hand.

“May I?,” her voice dangerously low, as she already moved the spoon towards her mouth, looking straight at you. You just gulped and managed a small nod as Wanda put the spoon in her mouth, her gaze never leaving you as she sucked it clean. Her green eyes were barely visible as her dilated pupils covered them almost completely. A soft moan escaped from her lips as she handed the spoon back to you.

“You're so good at this y/n,” Wanda groans, her hand which still holds onto your waist making its way to your lower back, smoothly slipping under your loose t-shirt. The cold rings on her fingers on your warm skin immediately sent shivers down your spine. Her pinky slightly slipped under the waistband of your sweatpants before she left you standing alone in the kitchen.

She must do this on purpose. There is no other way.

You thought to yourself. But what was the use? Either you are right and she does it on purpose or you are wrong and project your fantasies onto her. In both cases, it is best to simply stay away from Wanda. Because there is no way you don't end up completely fucked. Right?

: Part 2

#wanda maximoff#wanda x you#wanda x reader#scarlet witch#wanda maximoff x female reader#wanda maximoff x reader#wanda maximoff x you#wanda maximoff fanfiction#kate bishop#kate bishop x reader

519 notes

·

View notes

Text

Barbi. I support you in this I don't want to vote for Joe Biden any more than you do but some of us don't live in deep blue states. If he is the democratic nominee I will vote for Joe because I'd rather Texas go for Joe than fucking Desantis or Trump or whoever which is the reality I live in. People in red states can't fucking afford to vote 3rd party. Unless an honest to god miracle happens in the next year, people in red states need to vote blue no matter who.a

a reminder to my fellow usamericans that one year from now we are voting third party. free palestine

#listen to me. do you fucking see that this doesn't apply to some of us#in the eyes of the government i AM repeesented by Ted Cruz. and John Cornyn.#and various other Republican state and local officials. in the eyes of the government I wanted trump to win in 2020#and when it comes down to it? you have some level of protection by virtue of living in your state#at the end of the day I can't get an abortion if I need one. and you can#and I think you should not vote for biden but I cannot in good conscience vote third party next year#when my state is already at the mercy of the republican party

89 notes

·

View notes

Text

Marshmallow Longtermism

The paperback edition of The Lost Cause, my nationally bestselling, hopeful solarpunk novel is out this week!

My latest column for Locus Magazine is "Marshmallow Longtermism"; it's a reflection on how conservatives self-mythologize as the standards-bearers for deferred gratification and making hard trade-offs, but are utterly lacking in these traits when it comes to climate change and inequality:

https://locusmag.com/2024/09/cory-doctorow-marshmallow-longtermism/

Conservatives often root our societal ills in a childish impatience, and cast themselves as wise adults who understand that "you can't get something for nothing." Think here of the memes about lazy kids who would rather spend on avocado toast and fancy third-wave coffee rather than paying off their student loans. In this framing, poverty is a consequence of immaturity. To be a functional adult is to be sober in all things: not only does a grownup limit their intoxicant intake to head off hangovers, they also go to the gym to prevent future health problems, they save their discretionary income to cover a down-payment and student loans.

This isn't asceticism, though: it's a mature decision to delay gratification. Avocado toast is a reward for a life well-lived: once you've paid off your mortgage and put your kid through college, then you can have that oat-milk latte. This is just "sound reasoning": every day you fail to pay off your student loan represents another day of compounding interest. Pay off the loan first, and you'll save many avo toasts' worth of interest and your net toast consumption can go way, way up.

Cleaving the world into the patient (the mature, the adult, the wise) and the impatient (the childish, the foolish, the feckless) does important political work. It transforms every societal ill into a personal failing: the prisoner in the dock who stole to survive can be recast as a deficient whose partying on study-nights led to their failure to achieve the grades needed for a merit scholarship, a first-class degree, and a high-paying job.

Dividing the human race into "the wise" and "the foolish" forms an ethical basis for hierarchy. If some of us are born (or raised) for wisdom, then naturally those people should be in charge. Moreover, putting the innately foolish in charge is a recipe for disaster. The political scientist Corey Robin identifies this as the unifying belief common to every kind of conservativism: that some are born to rule, others are born to be ruled over:

https://pluralistic.net/2020/08/01/set-healthy-boundaries/#healthy-populism

This is why conservatives are so affronted by affirmative action, whose premise is that the absence of minorities in the halls of power stems from systemic bias. For conservatives, the fact that people like themselves are running things is evidence of their own virtue and suitability for rule. In conservative canon, the act of shunting aside members of dominant groups to make space for members of disfavored minorities isn't justice, it's dangerous "virtue signaling" that puts the childish and unfit in positions of authority.

Again, this does important political work. If you are ideologically committed to deregulation, and then a giant, deregulated sea-freighter crashes into a bridge, you can avoid any discussion of re-regulating the industry by insisting that we are living in a corrupted age where the unfit are unjustly elevated to positions of authority. That bridge wasn't killed by deregulation – it's demise is the fault of the DEI hire who captained the ship:

https://www.axios.com/local/salt-lake-city/2024/03/26/baltimore-bridge-dei-utah-lawmaker-phil-lyman-misinformation

The idea of a society made up of the patient and wise and the impatient and foolish is as old as Aesop's "The Ant and the Grasshopper," but it acquired a sheen of scientific legitimacy in 1970, with Walter Mischel's legendary "Stanford Marshmallow Experiment":

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stanford_marshmallow_experiment

In this experiment, kids were left alone in a locked room with a single marshmallow, after being told that they would get two marshmallows in 15 minutes, but only if they waited until them to eat the marshmallow before them. Mischel followed these kids for decades, finding that the kids who delayed gratification and got that second marshmallow did better on every axis – educational attainment, employment, and income. Adult brain-scans of these subjects revealed structural differences between the patient and the impatient.

For many years, the Stanford Marshmallow experiment has been used to validate the cleavage of humanity in the patient and wise and impatient and foolish. Those brain scans were said to reveal the biological basis for thinking of humanity's innate rulers as a superior subspecies, hidden in plain sight, destined to rule.

Then came the "replication crisis," in which numerous bedrock psychological studies from the mid 20th century were re-run by scientists whose fresh vigor disproved and/or complicated the career-defining findings of the giants of behavioral "science." When researchers re-ran Mischel's tests, they discovered an important gloss to his findings. By questioning the kids who ate the marshmallows right away, rather than waiting to get two marshmallows, they discovered that these kids weren't impatient, they were rational.

The kids who ate the marshmallows were more likely to come from poorer households. These kids had repeatedly been disappointed by the adults in their lives, who routinely broke their promises to the kids. Sometimes, this was well-intentioned, as when an economically precarious parent promised a treat, only to come up short because of an unexpected bill. Sometimes, this was just callousness, as when teachers, social workers or other authority figures fobbed these kids off with promises they knew they couldn't keep.

The marshmallow-eating kids had rationally analyzed their previous experiences and were making a sound bet that a marshmallow on the plate now was worth more than a strange adult's promise of two marshmallows. The "patient" kids who waited for the second marshmallow weren't so much patient as they were trusting: they had grown up with parents who had the kind of financial cushion that let them follow through on their promises, and who had the kind of social power that convinced other adults – teachers, etc – to follow through on their promises to their kids.

Once you understand this, the lesson of the Marshmallow Experiment is inverted. The reason two marshmallow kids thrived is that they came from privileged backgrounds: their high grades were down to private tutors, not the choice to study rather than partying. Their plum jobs and high salaries came from university and family connections, not merit. Their brain differences were the result of a life free from the chronic, extreme stress that comes with poverty.

Post-replication crisis, the moral of the Stanford Marshmallow Experiment is that everyone experiences a mix of patience and impatience, but for the people born to privilege, the consequences of impatience are blunted and the rewards of patience are maximized.

Which explains a lot about how rich people actually behave. Take Charles Koch, who grew his father's coal empire a thousandfold by making long-term investments in automation. Koch is a vocal proponent of patience and long-term thinking, and is openly contemptuous of publicly traded companies because of the pressure from shareholders to give preference to short-term extraction over long-term planning. He's got a point.

Koch isn't just a fossil fuel baron, he's also a wildly successful ideologue. Koch is one of a handful of oligarchs who have transformed American politics by patiently investing in a kraken's worth of think tanks, universities, PACs, astroturf organizations, Star chambers and other world-girding tentacles. After decades of gerrymandering, voter suppression, court-packing and propagandizing, the American billionaire class has seized control of the US and its institutions. Patience pays!

But Koch's longtermism is highly selective. Arguably, Charles Koch bears more personal responsibility for delaying action on the climate emergency than any other person, alive or dead. Addressing greenhouse gasses is the most grasshopper-and-the-ant-ass crisis of all. Every day we delayed doing something about this foreseeable, well-understood climate debt added sky-high compounding interest. In failing to act, we saved billions – but we stuck our future selves with trillions in debt for which no bankruptcy procedure exists.

By convincing us not to invest in retooling for renewables in order to make his billions, Koch was committing the sin of premature avocado toast, times a billion. His inability to defer gratification – which he imposed on the rest of us – means that we are likely to lose much of world's coastal cities (including the state of Florida), and will have to find trillions to cope with wildfires, zoonotic plagues, and hundreds of millions of climate refugees.

Koch isn't a serene Buddha whose ability to surf over his impetuous attachments qualifies him to make decisions for the rest of us. Rather, he – like everyone else – is a flawed vessel whose blind spots are just as stubborn as ours. But unlike a person whose lack of foresight leads to drug addiction and petty crimes to support their habit, Koch's flaws don't just hurt a few people, they hurt our entire species and the only planet that can support it.

The selective marshmallow patience of the rich creates problems beyond climate debt. Koch and his fellow oligarchs are, first and foremost, supporters of oligarchy, an intrinsically destabilizing political arrangement that actually threatens their fortunes. Policies that favor the wealthy are always seeking an equilibrium between instability and inequality: a rich person can either submit to having their money taxed away to build hospitals, roads and schools, or they can invest in building high walls and paying guards to keep the rest of us from building guillotines on their lawns.

Rich people gobble that marshmallow like there's no tomorrow (literally). They always overestimate how much bang they'll get for their guard-labor buck, and underestimate how determined the poors will get after watching their children die of starvation and preventable diseases.

All of us benefit from some kind of cushion from our bad judgment, but not too much. The problem isn't that wealthy people get to make a few poor choices without suffering brutal consequences – it's that they hoard this benefit. Most of us are one missed student debt payment away from penalties and interest that add twenty years to our loan, while Charles Koch can set the planet on fire and continue to act as though he was born with the special judgment that means he knows what's best for us.

On SEPTEMBER 24th, I'll be speaking IN PERSON at the BOSTON PUBLIC LIBRARY!!

If you'd like an essay-formatted version of this post to read or share, here's a link to it on pluralistic.net, my surveillance-free, ad-free, tracker-free blog:

https://pluralistic.net/2024/09/04/deferred-gratification/#selective-foresight

Image: Mark S (modified) https://www.flickr.com/photos/markoz46/4864682934/

CC BY 2.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/

#pluralistic#locus magazine#guillotine watch#eugenics#climate emergency#inequality#replication crisis#marshmallow test#deferred gratification

637 notes

·

View notes

Text

sure "nuns with guns" is a fun trope but can we have more "nuns with no romantic interest in men who turn to life in a nunnery to escape patriarchal expectations in favor of a woman-centric society, and in the process meet brilliant-but-headstrong Sister Virtue, who took vows to confound her father's plans to marry her off to local gentry, and having successfully escaped marriage now plots to escape the convent, but after living a youth defined by defiance is overwhelmed by the fact she doesn't know what life she wants only what life she rejects, and she can't imagine the shape of the future, so she just continues on with her work in the cheese shed experimenting with fungi until one day she meets the new novice (you) tasked with tending to the dairy cows, and she finds your milkmaid naivety off-putting (reminding her of a younger, more hopeful version of herself) but actually you aren't naive, you've survived countless hardship by choosing to believe in hope, choosing to believe in the goodness and kindness that all people are capable of (even as you accept the presence of violence and selfishness), and your optimism is both the sword and shield with which you ride every morning into the day's battle, and as Sister Virtue discovers this about you, she feels a spark in her belly that she has hardly felt since girlhood (when she would dream distressing dreams of the lips and bosom of the local barmaid, a childhood companion from whom she drifted slowly apart in the cusp of maidenhood), and she spurns your company as a result, but only briefly because all asudden you come down with a fierce sweating sickness, and Sister Virtue sits up all night by your sickbed, stroking your brow with a cloth and whispering hoarse prayers she isn't certain she believes in, and when you are recovered she surprises you with a picnic (only a simple meal of cheese and bread while you both bring the cows out to graze, but she has sneaked in a jug of mead and you feel like a schoolchild again, playing truant, and for a moment you ache for the life you might have had if you had been brave enough to keep fighting the world instead of hiding away in the monotonous safety of the abbey),,, and then suddenly the sky opens, and you and Sister Virtue are caught in a rainstorm, and there are raindrops dripping down your bodice, and your wimple is slipping from your forehead, and she leans in to pull the veil from your eyes, and you lean forward and

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

This has always been the problem with the Howard Zinn school of history. Zinn’s history of the US resembles a biography written by a bitter former spouse. In lieu of a nuanced and accurate historical account it offers a deliberate slander of our own culture. The result is at once self-indulgent and self-pitying. A balanced account must not flinch from examining our historical mistakes and misdeeds and those of others, but the modern approach to history has too often become a neurotic wallowing in half-truths of our own failures. The corresponding utopian fantasies of other cultures more closely resemble the morality play of a Tolkien novel than the more complex experiences of people who actually lived on Earth.

As UK-based IEA economist Kristian Niemietz recently observed in a short Twitter thread about “anti-Britishness,” signalling disgust at our own culture and history has little to do with truth or helping marginalized communities. Rather, it is a way to advertise the superficial cleverness of radical self-criticism. By castigating the United States on social media or with our K12 or university students, we can flatter our moral egos without needing to donate money or time to communities in need. It fosters division and the main beneficiaries are not Native Americans or other marginalized groups, but whoever is collecting likes and followers online.

We can do better than this. US history should be clear and accurate about the US’s misdeeds, but we should also acknowledge that the US overcame its faults to become a beacon for progress. In the same way, we should highlight the wonderful culture, arts, religion, and so on of American Indians without turning them into pious exemplars of pastoral innocence and moral instruction. Our “ethnic studies” curricula too often lapse into propaganda designed to indict and shame the West and all its works. People and cultures are complex. If students were permitted to understand that human failings are universal but can be overcome, it might help to alleviate the depression and anxiety of those unjustly burdened by the sins of their ancestors.

__________

Christopher J. Ferguson

excerpt from his book review of ‘Indigenous Continent’ by Pekka Hämäläinen @quilette

https://quillette.com/2023/04/27/uncomfortable-history/

#history#analysis of facts vs narratives#quilette#oikophobia#white guilt#bullshit#education#intellectual honesty and proportionality vs sentimentality or pseduo guilt that helps fuckall#examine your assumptions#intellectual honesty vs fundamentalist ideological loyalty#localize your virtue to help people in need where you are vs ideological conformity

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Non Amazon book resources

Look, I know Amazon is a sensitive topic. It has been allowed to dominate the market, and for indie writers, it is a huge (if not their main) source of income. Personally, as an indie writer, I have tried to always keep my work available elsewhere (because you can't trust Amazon not to screw you over, I mean just look at Audible. For those who don't know, Audible royally fucks over authors, and the narrators don't do that great either). But even for me, the loss of Amazon sales would highly affect my ability to keep going without getting another job or three. So I get it. Nonetheless, they cannot be trusted not to drop queer writers and readers, so it's best to have alternatives now.

If you are a reader or an indie author looking for different platforms to buy and/or sell books, even if only to start branching out a little, here is a list.

I doubt it's comprehensive. Feel free to reblog with more.

Kobo and Kobo Plus -Kobo is the biggest online 'Zon alternative. Kobo Plus is sort of like KU. On either one, you get points for buying books and can use the points to get more books. Works for ebook and audiobooks. (And, if you have a non-Kindle ereader, it works for Kobo but it also works for like, fanfiction. I'm just saying. I got a refurbished Kobo a while ago and it's lovely.)

Bookshop.org -print as well as ebooks

Smashwords/Draft2Digital - mostly ebooks but D2D does have a print option

Itch.io - ebook only (but gives a larger chunk of profits to authors than 'Zon does. Authors take note.)

Gumroad

Rainbow Crate -special edition print queer books. (I know there was some controversy with them but I am out of touch and don't know what it was, and most people who use them seem happy with them??? but if you know other queer/romance book crate services, lemme know)

The Ripped Bodice -brick and mortar stores but you can also shop online

Check out your local bookstores---many will order print copies for you if you request them

The authors' websites if they do direct sales

Barnes & Noble- yeah, it's a corporation and they are not great either, but it's not Amazon and sometimes a well-meaning relative gets you a gift card. And, for the moment, they do in fact sell queer romance. I know because I just used a gift card to get a paperback of The Prince and the Assassin. lol

Powell's Books- Portland's famous book store sells new and used books (and you can browse the stock online) --print only. They sell queer romance as well. I got a copy of Drag Me Up by RM Virtues there. That's not super relevant, but I was pleased :)

New link: Queer Books Weekly-- free and affordable books with queer protagonists

Also consider library books!

And for those in America--you can use library apps to read books. Yes, the authors still get paid! Libby is a big one. You can get audiobooks too, AND it can connect you with the Queer Liberation Library.

Also there is Hoopla - digital content

In Europe, I know there is Vivlio, which is French and I believe sells ereaders and also ebooks.

#amazon#books#bookblr#queer books#queer romance#queer fiction#lgbtqia#lgbtq+#romance#kobo#kobo plus#itch.io

162 notes

·

View notes

Text

Primal Chic: The Princess Saves Herself & The Planet in this It Girl meets Survivalist Lifestyle

If you think it girl, you may think of high maintenance, high consumption, pampered, luxe living. I want you to take a step back from that idea with me and introduce a new mindset, Primal Chic. Borrowing from the Clean Girl, GORP Girl, It Girl, Stoic, Survivalist, and Prepper, Primal Chic is all about minimizing your impact on the planet, maximizing your self-sufficiency, and building meaningful sisterhood.

Primal Chic in 3 Words is: Sustainability, Self-Sufficiency, & Sisterhood.

Body: Fuel, Movement, & Beauty

Fuel: Our bodies and minds need high-quality fuel, and that's offered by a whole-food, paleo diet. Many of the foods on the market are heavily processed and loaded with low-quality fillers that drive calories and macros up without meeting our micronutrient needs. On top of this, a huge segment of the market is imported from outside of our local communities, adding heavily to the carbon footprint of our foods. Choosing locally grown, non-GMO, organic produce and proteins from fair trade, regenerative, or woman-owned agri-businesses is a fantastic stepping stone if you can't generate your own food due to time, space, or monetary constraints. I love shopping locally owned health food stores, farmers markets, and farm stands. The price of organics also goes down if you shop store-brand organics. There are also Facebook groups and Pinterest boards dedicated to Paleo recipe swaps. You also want to make sure you're honoring your body's needs in all of it's areas, rest, relaxation, movement, and nutrition.

Movement: Functional, outdoor movement benefits body, mind, and soul. A good hike, a lake swim, or even just a good jog with your pets are all great ways to get your cardio in. Outdoor yoga, rucks, rock climbing, and calisthenics are low-cost, high-reward strength and conditioning exercises that help you to keep toned and ready for action in your day-to-day life. Don't forget ROM either, active recovery walks, daily yoga, and deep stretches ensure you remain flexible and reduce pain from tight, stiff muscles and joints. Adding in a few friends allows you to build sisterhood and meet your social needs too, and being outdoors helps with the chronic vitamin D deficiencies most modern women face.

Beauty: Choosing clean, sustainable beauty and reducing the number of products used is good for your body due to fewer toxins, your mind with lower body and facial dysmorphia from high glam makeup looks, and the planet with less harsh manufacturing processes. Consider switching to multi-use products, reducing the number of products in your skincare & makeup routines, and swapping to washable/reusable body, skin, and feminine hygiene products to care for yourself and our planet. I'll be going into more detail on the swaps I made personally in a blog post next week.

Side Note: Planning a girl's weekend yoga retreat or having a buddy to do the Whole30 (a great intro to Paleo eating) with you is a great way to build up your sisterhoods and your own resolve for this new lifestyle.

Mind: Clarity, Wisdom, and Continuous Growth

Stoicism: The serenity prayer is a fantastic example of the basis of stoicism, letting go of the things you can't control or change, courageously sticking to your values and virtues and changing or controlling the things you can, living in harmony with nature, practice emotional mindfulness and emotional chastity, and practice resilience, learning to bounce back from failures and misfortune. With all things in life there is a learning curve, and allowing yourself to be ruled by algorithms, propaganda, and impulses reduces your own personal power.

Minimalism: Cut out overconsumption to help save the planet, save your wallet, and save your space. Choosing quality, durable, practical, and multi-purpose items allows you to spend less time organizing and cleaning and more time with friends and family, and doing the things that truly feed your soul. You don't have to have a spartan, sterile, white living space to embrace minimalism either, you can still inject your own personal style and personality into your choices, but be more mindful about where and how you're spending your hard-earned money.

Dedication to Continuous Growth: Instead of doom-scrolling or watching brain-rotting television, try switching out social media for micro-learning, soaps for documentaries, and limiting screen time to 1-3 hours per day. Try switching out happy hour for a self-defense or first aid class. Get involved with book swaps and information databases or group PDF sharing.

Heart: Love Thyself, Love Thy Neighbor, Love Thy Planet

Self-Love: Forming a sisterhood and meaningful community starts with loving yourself. You can't draw from an empty well, so being honest and vulnerable with yourself and taking care of yourself is the first step in being able to be there for others at your most authentic. Reminding yourself of your inherent value is important.

Earth: The frequencies of the earth are often interfered with by our man-made surroundings, taking time to ground yourself and connect with the world around you, either on your own, or in a group, is good for the heart. Try and take an hour or two per day and spend it outdoors, really soaking in the beauty you may have been numbed to by having it become mundane.

Connection & Community: Not everyone you meet deserves your whole heart and mind, however, they do deserve basic human dignity and respect, for those closer to you, they do deserve having a reliable friend who they can turn to in times of need and times of victory. Forming meaningful connections across generational divides makes us stronger as women and enriches our lives.

Soul: Mindfulness, Purpose, & Resilience

Mindfulness: Meditation, nature walks, situational awareness, and group activities keep the mind and soul well-fed and the senses sharp should the need arise for defense. Live in the moment as much as you can, rather than drift aimlessly through life without a plan of attack. Spontaneity can still exist here, as you should have a balance of routine and flexibility.

Purpose: What drives you? Who drives you? What values are at your core? Answering these questions allows you to live a purposeful life where you are true to yourself and your community. If your values don't align with the life you're living what changes do you need to have them align?

Resilience: You don't have to make your life harder, but preparing for life's rough times through mental, spiritual, physical, financial and material preparedness is still important. Building a solid community will help with this, but ensuring you yourself have the tools and skills necessary for survival will help even more so.

Planet: Stewardship, Sustainability, and Conscious Consumption

Stewardship: Bring a bag with you on walks and hikes to collect trash and follow the old Girl Scout principle of leaving things better than you found them. Encourage sustainable practices with where you shop and invest your time and resources, and take advantage of your local parks and wild spaces.

Sustainability: Opt for natural materials in clothing, decor, & home goods. Choose materials like wood, cotton, real fur, leather, and linen rather than plastics and petroleum-derived products or "natural" materials with harsh production processes like viscose or bamboo fiber. Reduce your consumption of new products, and shop thrift or vintage where you can, and go as ecologically friendly and durable as you can afford when buying new.

Conscious Consumption: Shop local, woman-owned, small business, and fair trade products wherever you can, skip out on mega polluters like Amazon or Shien, and avoid sweatshop and slave labor wherever you can. Before making purchases, ask yourself if you truly need an item or if you're just looking for a quick dopamine hit. Mend your things if possible rather than trashing them, and opt for donation of things in good condition that no longer fit with who you are.

All in all, the Primal Chic lifestyle is attainable for everyone, and about making conscious, cognizant steps toward a more meaningful, impactful, and mindful life where you live sustainably, & self sufficiently while building meaningful community and sisterhood.

#cvt2dvm#studyblr#self care#self improvement#self love#study blog#self sustainability#self reliance#sustainability#self sufficiency#self sufficient living#self awareness#self defense#self development#it girl journey#it girl#primal chic#clean girl#aesthetics#lifestyles#lifestyle blog#ecofriendly#ecofeminism#ecofashion#green living#blog post#blogging#girl blogging#becoming that girl#becoming her

170 notes

·

View notes

Text

im not a primmie but i feel like i "get" it in a way i didn't used to, now that ive read some ethnographies of them. like. i mean, obviously it sucks. it is, on net, dispreferred. we shouldnt reorganize society towards it. but i think the hunter gatherer lifestyle does have particular virtues that modern life doesnt. they're hard to refer to. i dont think theyre *actually* more subtle than like "freedom" or whatever as concepts, but we dont have a whole societal thing about referring to them, so i cant just use a premade word and give you all sorts of complex preloaded concepts.

one of the virtues is...explainability-autonomy. but specifically like. everything you own (i mean, except for a few luxury trade goods) is something you know how to make, or you know a guy who knows how to make it. so you're not in a "matrix" the way we are, on the scale of a community you're more atomized. as soon as a culture gets mined metal this goes out the window, your livelihood is dependent on far-away people.

and this explainability-autonomy holds for the social world as well, even if your culture has an elaborate hierarchy it's a local one, you know everyone in your hierarchy structure. so you can know your social threats in a way you can't in the modern world (i mean, unless you count an ambush-massacre as a social threat).

and then seemingly opposite there's a feature people gloss as "community" but which i think is more like....absolute interdependence. like, you have these people around you, and theyre your only social interaction, or entertainment, and theyre essential for you getting food, and building the house you live in, on and on. like you just depend on each other so intensely (ofc this will depend on the particular H-G group, some were more interdependent and some were relatively independent, depending on hunting style, type of dwelling, etc). and this doesnt seem like a PLEASANT state of affairs but it is *intense* and maybe even beauitful. its like soldiers in the same squad. warriors bond.

this isnt all of them, but its a distinctive pair

128 notes

·

View notes

Text

warnings!: a bit drunk sylus, so mentions of alcohol and consume of it

your hometown seems prettier than ever with sylus walking by your side, with your hand entwined with his, as his voice hums some sweet song while you approach your old house's main entrance. the tall man smiles at you, his red eyes shining tenderly, as he knocks on the door.

all your memories - your childhood, the smell of food, the paintings hanging on the walls - hit you as soon as the door opens. sylus introduces himself to them, to your family, to those tied to you by blood and those that became part of it. he patiently hears the elder's talk about their young days, they way they embarrass you with stories of when you were younger, the way they compliment him and how he looks at you with a playful grin. he kneels to be able to talk with the younger ones, the ones that tell him he looks like a prince, whom ask for a game after lunch. sylus - your present and your future, the man that promised to protect you, the one you want to be with for the rest of your life - and them - your past, the ones that made you became who you are now, who shaped you, who forged your virtues and defects. - merge so well, as if all the pieces that took so long to repair inside of you were finally glued by the sound of their shared laughter.

lunch happens without any incident, apart from the continuous questions to a very confident sylus, and suddenly it's already time for the after lunch. bottles and bottles of exquisite local liquor and other alcohols run through the table while the kids play in the background. even when your man has a really strong alcohol tolerance, you fear maybe they're giving him too many things to try.

"sylus, maybe... that's enough." you see how the next shot -this time, pomace cream- slides into his mouth, with a drop running down his lip, that he's quick to catch with his tongue. he gives you a quick kiss, leaving a sweet flavor on them.

"i'm alright, love. it would be rude to refuse." but their tolerance outpaces your boyfriend's. green liquors, coffee ones, strawberry creams... he tries at least a shot of all of them, and even when he's being polite and rejecting most of the glasses, your family keeps insisting on the most famous ones. the elders pat his shoulders and you stand up quickly, taking your boyfriend's arm and walking towards the upper flat with a poor excuse. "please, forgive us. we're very tired of the trip, and we would like to rest. we'll be in my old room."

going upstairs, sylus walks by your side, tangling his arm on your waist and following you closely. as soon as you arrive, you see the old couch you used to spend so many afternoons in, reading a book, playing a game or watching a show. before being able to arrive to your old room, sylus turns around and, with a smile, he kisses the tip of your nose. seeing this version of him - so blushed, so soft, so tipsy.- makes your heart flutter.

"you're so drunk, sylus. i knew i shouldn't have let you stay for the afterlunch." he laughs and lets all his tall body fall in your couch, way too small for his body. he seems uncomfortable, so you guide him to lie properly. "here. your feet. now your knees, bend them." his movements mimic your orders, and his eyes are focused on you with attention.

"and now?" he asks. his voice sounds sleepy, but he's incredibly attentive to you.

"your hands under your head." he does so, and you kneel near him, his face close to yours. he hums.

"you could just buy a bigger couch." he whispers, glancing at his knees. "you can't fit here with me if my knees are not straight." his faces turns into a pout, before looking back at you. his red, sleepy eyes in contrast with his white, wild hair. he smiles sweetly. "but don't worry, love." he stretches his body, letting his feet hang from the couch, and resting his back against the cushions. "i can sleep with my feet outside the couch, but not without you." his hand moves to your cheek, caressing it, the very most sincere gaze you've seen from him looking directly at you. so full of love, of affection and happiness; of desire, of willing, of sweetness, of devotion. all the feelings he always tries to demonstrate to you, to tell you, to shout to everyone; caged in such a passional red-shade eyes.

his hand caresses your cheek, your jaw, your neck. it follows the pace of the same song he has been humming all day, some local tune he heard on the radio on your drive here. it's slow, pleasant, subtle; and his thick voice, roughened by sleep and alcohol, welcomes you to hear more of it. his hand quickly reaches your arm, pulling you sweetly towards the couch, making room for you in front of his body, facing him. his chest rises and falls with each quiet breath, and your bodies are too close. he sighs.

"are you alright, love? comfortable?" you nod a couple times against his collarbone. he smiles, even when you can't see him. you silently thank fate for bringing him into your life, for the smell of his cologne that feels like being home, for the warmth of his hands on your lower back, for the way you tangle your legs between his.

"forget the bigger couch, i think we should get one this size for our home." his sudden words make you laugh, quickly passing in on to him. his embrace becomes stronger and you close your eyes, face buried on his chest, feeling the laughs and the chats of the floor below. you smile.

maybe he's all you've been searching for.

"sylus." you fear he's asleep, but his low "hm?" reaches your ears.

"i love you."

the room falls silent for what seems to be hours, but you feel how his grip tighten, his body pressing even closer to yours as he takes a deep breath.

"i love you. i love you so much, so much more"

#funny thing: this is based on tonight's dream (i dream weird things)#warnings: alcohol#lunae writes#sylus x you#sylus x reader#sylus x y/n#l&ds sylus x reader#l&ds sylus x you#l&ds x reader#l&ds x you#l&ds sylus#love & deepspace x reader#love & deepspace x you#love & deepspace sylus#sylus fluff#l&ds fluff#love & deepspace fluff#l&ds fanfiction

207 notes

·

View notes

Text

Editor’s note: This story contains content that readers may find disturbing, including graphic allegations of sexual assault.

Scarlett Pavlovich was a 22-year-old drama student when she met the performer Amanda Palmer by chance on the streets of Auckland. It was a gray, drizzly afternoon in June 2020, and Palmer, then 44, was walking down the street with the actress Lucy Lawless, one of the most famous people in New Zealand owing to her six-season stint portraying Xena the warrior princess. But Pavlovich noticed only Palmer. She’d watched her TED talk, “The Art of Asking,” and was fascinated by the cult-famous feminist writer and musician — by her unabashed self-assurance.

On the surface, Pavlovich appeared to be self-assured as well. A local girl, she had dropped out of high school at 15 to travel to Europe, Morocco, and the Middle East on the cheap, pausing in Scotland — where Tilda Swinton gave her a scholarship to attend her Steiner school, Drumduan — and London to work in the cabaret scene. Eventually, her visa expired and she ran out of money and so, in 2019, she returned to Auckland, where she enrolled in an acting school and took a job at a perfumery. Pale and dark-haired and waifish, she favored bold colors and outrageous outfits. On the day she met Palmer — on most days then — she’d painted a triangle of translucent silver beneath her lower lashes so it looked as though she’d been crying tears of glitter. It was Pavlovich who approached Palmer on the sidewalk outside the perfumery. She was surprised when Palmer texted her a few days later. “It’s amanda d palmer,” she wrote. “Your new friend.”

Palmer, an obsessive chronicler of her own life in songs, poems, blog posts, and a memoir, got her start as half of the punk cabaret band the Dresden Dolls, but she is perhaps more famous for her ability to attract a tight-knit and devoted following wherever she goes. In 2012, she became the first musician to raise more than $1 million on Kickstarter and later became one of Patreon’s most successful artists. As Palmer explained in her book The Art of Asking — part memoir, part manifesto on the virtues of asking for assistance of various kinds — she had built her entire career on “messy exchanges of goodwill and the swapping of favors.” Out of this mess, she argues, a utopian sort of community formed: “There was no distinction between fans and friends.”

Over the following year and a half, Palmer and Pavlovich occasionally met for a drink or a meal. Palmer offered Pavlovich tickets to her shows and invited her to parties for the Patreon community at her house on nearby Waiheke Island, a lush bohemian retreat with vineyards, golden beaches, and more than 60 helipads to accommodate the billionaires who vacationed there. Sometimes Palmer asked Pavlovich for favors — help running errands or organizing files or looking after her child. Pavlovich was happy to assist. She had a crush on Palmer. She didn’t mind that Palmer only occasionally discussed paying her, even though Pavlovich was always strapped for cash. For Pavlovich, who was estranged from her family and without a safety net, Palmer filled a deeper need. In November 2020, Palmer invited her to hang out at her place for a weekend with a group of local artists. At the gathering, Palmer asked Pavlovich to babysit while she got a massage. Early the next morning, Pavlovich wrote a diary entry about the easy intimacy she’d felt in Palmer’s sun-drenched home, where she’d read to Palmer’s son, who was 5 at the time, their limbs entwined. “The years absent of touch build up like a gray inheritance,” she wrote. “I’m hungry. I am so fucking famished.”

On February 1, 2022, Palmer texted Pavlovich and asked if she wanted to spend the weekend babysitting, which would mean bouncing back and forth between her house and her husband’s. Pavlovich had never met Palmer’s husband, from whom she was separated, though of course she knew who he was: Neil Gaiman, the acclaimed British fantasist and author of nearly 50 books, including American Gods and Coraline, and the comic-book series The Sandman, whose work has sold more than 50 million copies worldwide. Gaiman and Palmer had arrived in New Zealand in March 2020, but just weeks later, their nine-year marriage collapsed and Gaiman skipped town, breaking COVID protocols to fly to his home on the Isle of Skye. Now, he’d returned and was living in a house near Palmer’s on Waiheke. Their previous nanny had recently left, and they needed help. Pavlovich agreed and was pleased when Palmer offered to pay her for the weekend’s work.

Around four in the afternoon on February 4, Pavlovich took the ferry from Auckland to Waiheke, then sat on a bus and walked through the woods until she arrived at Gaiman’s house, an asymmetrical A-frame of dark burnished wood with picture windows overlooking the sea. Palmer had arranged a playdate for the child, so not long after Pavlovich arrived, she found herself alone in the house with the author. For a little while, Gaiman worked in his office while she read on the couch. Then he emerged and offered her a tour of the grounds. A striking figure at 61, his wild black curls threaded with strands of silver, the author picked a fig — her favorite fruit — and handed it to her. Around 8 p.m., they sat down for pizza. Gaiman poured Pavlovich a glass of rosé and then another. He drank only water. They made awkward conversation about New Zealand, about COVID. Pavlovich had never read any of his work, but she was anxious to make a good impression. After she’d cleaned up their plates, Gaiman noted that there was still time before they would have to pick up his son from the playdate. “‘I’ve had a thought,’” she recalls him saying. “‘Why don’t you have a bath in the beautiful claw bathtub in the garden? It’s absolutely enchanting.’” Pavlovich told Gaiman that she was fine as she was but ultimately agreed. He needed to make a work call, he said, and didn’t want Pavlovich to be bored.

Gaiman led Pavlovich down a stone path into the garden to an old-fashioned tub with a roll top and walked away. She got undressed and sank into the bath, looking up at the furry magenta blossoms of the pohutukawa tree overhead. A few minutes later, she was surprised to hear Gaiman’s footsteps on the stones in the dark. She tried to cover her breasts with her arms. When he arrived at the bath, she saw that he was naked. Gaiman put out a couple of citronella candles, lit them, and got into the bath. He stretched out, facing her, and, for a few minutes, made small talk. He bitched about Palmer’s schedule. He talked about his kid’s school. Then he told her to stretch her legs out and “get comfortable.”

“I said ‘no.’ I said, ‘I’m not confident with my body,’” Pavlovich recalls. “He said, ‘It’s okay — it’s only me. Just relax. Just have a chat.’” She didn’t move. He looked at her again and said, “Don’t ruin the moment.” She did as instructed, and he began to stroke her feet. At that point, she recalls, she felt “a subtle terror.”

Gaiman asked her to sit on his lap. Pavlovich stammered out a few sentences: She was gay, she’d never had sex, she had been sexually abused by a 45-year-old man when she was 15. Gaiman continued to press. “The next part is really amorphous,” Pavlovich tells me. “But I can tell you that he put his fingers straight into my ass and tried to put his penis in my ass. And I said, ‘No, no.’ Then he tried to rub his penis between my breasts, and I said ‘no’ as well. Then he asked if he could come on my face, and I said ‘no’ but he did anyway. He said, ‘Call me ‘master,’ and I’ll come.’ He said, ‘Be a good girl. You’re a good little girl.’”

In The Sandman, the DC comic-book series that ran from 1989 to 1996 and made Gaiman famous, he tells a story about a writer named Richard Madoc. After Madoc’s first book proves a success, he sits down to write his second and finds that he can’t come up with a single decent idea. This difficulty recedes after he accepts an unusual gift from an older author: a naked woman, of a kind, who has been kept locked in a room in his house for 60 years. She is Calliope, the youngest of the Nine Muses. Madoc rapes her, again and again, and his career blossoms in the most extraordinary way. A stylish young beauty tells him how much she loved his characterization of a strong female character, prompting him to remark, “Actually, I do tend to regard myself as a feminist writer.” His downfall comes only when the titular hero, the Sandman, also known as the Prince of Stories, frees Calliope from bondage. A being of boundless charisma and creativity, the Sandman rules the Dreaming, the realm we visit in our sleep, where “stories are spun.” Older and more powerful than the most powerful gods, he can reward us with exquisite delights or punish us with unending nightmares, depending on what he feels we deserve. To punish the rapist, the Sandman floods Madoc’s mind with such a wild torrent of ideas that he’s powerless to write them down, let alone profit from them.

As allegations of Gaiman’s sexual misconduct emerged this past summer, some observers noticed Gaiman and Madoc have certain things in common. Like Madoc, Gaiman has called himself a feminist. Like Madoc, Gaiman has racked up major awards (for Gaiman, awards in science fiction and fantasy as well as dozens of prizes for contemporary novels, short stories, poetry, television, and film, helping make him, according to several sources, a millionaire many times over). And like Madoc, Gaiman has come to be seen as a figure who transcended, and transformed, the genres in which he wrote: first comics, then fantasy and children’s literature. But for most of his career, readers identified him not with the rapist, who shows up in a single issue, but with the Sandman, the inexhaustible fountain of story.

One of Gaiman’s greatest gifts as a story-teller was his voice, a warm and gentle instrument that he’d tuned through elocution lessons as a boy in East Grinstead, 30 miles south of London. In America, people mistakenly assumed he was an English gentleman. “He spoke very slowly, in a hypnotic way,” says one of his former students at the fantasy-writing workshop Clarion. He wrote that way, too, with rhythm and restraint, lulling you into a trance in the way that a bard might have done with a lyre. Another gift was his memory. He has “libraries full of books memorized,” one of his old friends tells me, noting that he could recall the page numbers of his favorite passages and recite them verbatim. His vast collection was eclectic enough to encompass both a box of comics (Spider-Man, Silver Surfer) from his boyhood and the works of Oscar Wilde he received as a gift for his bar mitzvah. For The Sandman, a forgotten DC property he had been hired to dust off and polish up, Gaiman gave the hero a makeover, replacing his green suit, fedora, and gas mask with the leather armor of an angsty goth, and surrounded him with characters drawn from the books he could pull off the shelves in his head, from timeless icons like Shakespeare and Lucifer to the obscure San Francisco eccentric Joshua Abraham Norton. Norman Mailer called it “a comic strip for intellectuals.”

Gaiman and the Sandman shared a penchant for dressing in black, a shock of unruly black hair, and an erotic power seldom possessed by authors of comic books and fantasy novels. A descendant of Polish Jewish immigrants, Gaiman had gotten his start in the ’80s as a journalist for hire in London covering Duran Duran, Lou Reed, and other brooding lords of rock, and in the world of comic conventions, he was the closest thing there was to that archetype. Women would turn up to his signings dressed in the elaborate Victorian-goth attire of his characters and beg him to sign their breasts or slip him key cards to their hotel rooms. One writer recounts running into Gaiman at a World Fantasy Convention in 2011. His assistant wasn’t around, and he was late to a reading. “I can’t get to it if I walk by myself,” he told her. As they made their way through the convention side by side, “the whole floor full of people tilted and slid toward him,” she says. “They wanted to be entwined with him in ways I was not prepared to defend him against.” A woman fell to her knees and wept.

People who flock to fantasy conventions and signings make up an “inherently vulnerable community,” one of Gaiman’s former friends, a fantasy writer, tells me. They “wrap themselves around a beloved text so it becomes their self-identity,” she says. They want to share their souls with the creators of these works. “And if you have morality around it, you say ‘no.’” It was an open secret in the late ’90s and early aughts among conventiongoers that Gaiman cheated on his first wife, Mary McGrath, a private midwestern Scientologist he’d married in his early 20s. But in my conversations with Gaiman’s old friends, collaborators, and peers, nearly all of them told me that they never imagined that Gaiman’s affairs could have been anything but enthusiastically consensual. As one prominent editor in the field puts it, “The one thing I hear again and again, largely from women, is ‘He was always nice to me. He was always a gentleman.’” The writer Kelly Link, who met Gaiman at a reading in 1997, recalls finding him charmingly goofy. “He was hapless in a way that was kind of exasperating,” she says, “but also made him seem very harmless.” Someone who had a sexual relationship with Gaiman in the aughts recalls him flipping through questions fans wrote on cards at a Q&A session. Once, a fan asked if she could be his “sex slave”: “He read it aloud and said, ‘Well, no.’ He’d be very demure.”

This past July, a British podcast produced by Tortoise Media broke the news that two women had accused Gaiman of sexual assault. Since then, more women have shared allegations of assault, coercion, and abuse. The podcast, Master, reported by Paul Caruana Galizia and Rachel Johnson, tells the stories of five of them. (Gaiman’s perspective on these relationships, including with Pavlovich, is that they were entirely consensual.) I spoke with four of those women along with four others whose stories share elements with theirs. I also reviewed contemporaneous diary entries, texts and emails with friends, messages between Gaiman and the women, and police correspondence. Most of the women were in their 20s when they met Gaiman. The youngest was 18. Two of them worked for him. Five were his fans. With one exception, an allegation of forcible kissing from 1986, when Gaiman was in his mid-20s, the stories take place when Gaiman was in his 40s or older, a period in which he lived among the U.S., the U.K., and New Zealand. By then, he had a reputation as an outspoken champion of women. “Gaiman insists on telling the stories of people who are traditionally marginalized, missing, or silenced in literature,” wrote Tara Prescott-Johnson in the essay collection Feminism in the Worlds of Neil Gaiman. Although his books abounded with stories of men torturing, raping, and murdering women, this was largely perceived as evidence of his empathy.

Katherine Kendall was 22 when she met Gaiman in 2012. She was volunteering at one of his events in Asheville, North Carolina. He invited her to join him a few days later at an after-party for another event, where he kissed her. The two struck up a flirtatious correspondence, emailing and Skyping in the middle of the night. Kendall didn’t want to have sex with Gaiman, and on one of their calls, she told him this. Afterward, she recorded his reply in her diary: “He had no designs on me beyond flirty friendship and I believe him thoroughly.” She’d grown up listening to his audiobooks, she later told Papillon DeBoer, the host of the podcast Am I Broken: “And then that same voice that told me those beautiful stories when I was a kid was telling me the story that I was safe, and that we were just friends, and that he wasn’t a threat.”

With Kendra Stout in April 2007. Photo: Courtesy of Kendra

Gaiman had been having sexual encounters with younger fans for a long time. Kendra Stout was 18 when, in 2003, she drove four and a half hours to Fort Lauderdale, Florida, to see Gaiman read from Endless Nights, a follow-up to The Sandman. She met him in the signing line. Gaiman sent her long emails and bought her a web camera so they could chat on video. Around three years after they met, he flew to Orlando to take her on a date. He invited her back to his hotel room, put on a playlist of love songs, and held her down with one hand. Gaiman didn’t believe in foreplay or lubrication, Stout tells me, which could make sex particularly painful. When she said it hurt too much, he’d tell her the problem was she wasn’t submissive enough. “He talked at length about the dominant and submissive relationship he wanted out of me,” she tells me. Stout had no prior interest in BDSM. She says Gaiman never asked what she liked in bed, and there was no discussion of “safe words” or “aftercare” or “limits.” He’d ask her to call him “master” and beat her with his belt. “These were not sexy little taps,” she says. When she told him she didn’t like it, she says he replied, “It’s the only way I can get off.”

Gaiman told Stout he had been introduced to these practices by a woman he’d met in his early 20s who had asked him to “whip her pussy.” At the time, he claimed to Stout, he was such a naïve Englishman that he thought she meant her cat. Then she handed him a flogger and told him to use it on her vagina. “‘This is what gets me off now,’” Stout recalls him saying. A similar anecdote shows up in an interview Gaiman gave for a 2022 biography of Kathy Acker, the late experimental punk writer Gaiman befriended in his 20s, but he offers a different account of how it affected him. When Acker asked him to “whip her pussy,” he found it “profoundly unsexual,” he told the interviewer. “I did it and ran away.” He identified himself as “very vanilla.”

In 2007, Gaiman and Stout took a trip to the Cornish countryside. On their last night there, Stout developed a UTI that had gotten so bad she couldn’t sit down. She told Gaiman they could fool around but that any penetration would be too painful to bear. “It was a big hard ‘no,’” she says. “I told him, ‘You cannot put anything in my vagina or I will die.’” Gaiman flipped her over on the bed, she says, and attempted to penetrate her with his fingers. She told him “no.” He stopped for a moment and then he penetrated her with his penis. At that point, she tells me, “I just shut down.” She lay on the bed until he was finished. (This past October, she filed a police report alleging he raped her.)

After Gaiman got into the bathtub with Pavlovich, she retreated to Palmer’s house, which was vacant at the time. She sat in the shower for an hour, crying, then got into Palmer’s bed and began to search the internet for clues that might explain what had happened to her. She Googled “Me Too” and “Neil Gaiman.” Nothing. The only negative stories she found were about how he’d broken COVID lockdown rules in 2020 and had been forced to apologize to the people of the Isle of Skye for endangering their lives.

At the end of the weekend, Palmer texted Pavlovich to say how pleased she was to see Pavlovich and her child get along. “The universe is a karmic mystery,” Palmer wrote. “We nourish each other in the most random and unpredictable ways.” Palmer asked if she could babysit again. She needed so much help. Would Pavlovich consider staying with them for the foreseeable future?

Pavlovich was living in a sublet that was about to end. She was broke and hadn’t been able to find a new apartment. She’d been homeless at the start of the pandemic, when the perfumery closed, and had ended up crashing on the beach in a friend’s sleeping bag on and off for the first two weeks of lockdown. The thought of returning to the beach filled her with dread.