#letters and journals of lord byron

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

i thought nothing could be worse than the burning of byron’s memoirs but i stand corrected after reading jane austen’s poor wikipedia page

because at least we still have thousands of byron’s letters and journals which are mostly uncensored and which reveal his personality in all of it’s aspects, flaws and all, and everyone in his circle documented every detail of his life because he was a huge celebrity. his letters are considered some of the most brutally transparent ever written. i'm just using him as an example; him and austen shared the same publisher, lived during the same time, both very studied.

but with jane austen? we don’t get that honesty or that truly full picture. her relatives are the main sources of information, and all her surviving letters were carefully selected by them to portray her according to a specific agenda which would favor them, and so the true extent of her personality can never be as fully ascertained.

but at the same time... i don't think that's necessarily a bad thing. she doesn't seem to have wanted attention for herself but to have likely preferred privacy, and her books have gotten more acclaim that she ever could have comprehended -- her books are the way we access her, her life, her thoughts and her voice. i think that about all writers, though i do love biographical criticism and biography.

some writers we know nothing about and some writers we know everything about -- at least they all live on in their writing, yes. but on the one hand, i'm grateful all writers live on in their work (as a fan of history and literature) and on the other hand, my unquenchable curiousity does get annoyed with the lack of available information. i would really love to read an extensive series of austen diaries. there is something sort of voyeuristic about this, i know, but there is also a love of preserving the niche parts of history, the parts that others overlook, the undervalued parts (letters, diaries, receipts, notes, scraps, drafts, juvenilia, etc.)

marcus aurelius wanted his diaries burned but perverse curiousity, likely driven by excessive admiration, led to their preservation, and thus we have his meditations which is now one of the most valued pieces of literature ever. so i think letters and diaries, and any piece of writing, does have immense value, even when it borders on a violation of privacy or has the potential to ruin a reputation.

i think this all simply ties in to the fact that i don't believe in book-burning in any form. embarrassing love letters from 1812 ARE important, depressing diary entries from 1818 ARE important. i could go on and on and on but the point is that i think all words and all history are imporant. in my classes we've discussed how archival technology is at the forefront of all human knowledge: what do we keep, what do we preserve, what do we spend more time on salvaging?

it just kills me that so much has been burned and destroyed, regardless of all the intense ethical discussions which could derive from all this, which could go on for a million years. my point is that it is tragic that so much of austen's work was destroyed, and it is tragic that byron's memoirs were destroyed even though we have so much of his work any way. any loss of writing is a loss to posterity.

#ramble#thoughts#jane austen#literature#english literature#romanticism#lord byron#letters#history#english lit#lit#writing#literary history#womens history#censorship#journals#biography#my analysis#my essays#my writing#pride and prejudice#ji

109 notes

·

View notes

Text

A list of all the books mentioned in Peter Doherty's journals (and in some interviews/lyrics, too)

Because I just made this list in answer to someone's question on a facebook group, I thought I may as well post it here.

-The Picture of Dorian Gray/The Ballad Of Reading Gaol/Salome/The Happy Prince/The Duchess of Padua, all by Oscar Wilde -The Thief's Journal/Our Lady Of The Flowers/Miracle Of The Rose, all by Jean Genet -A Diamond Guitar by Truman Capote -Mixed Essays by Matthew Arnold -Venus In Furs by Leopold Sacher-Masoch -The Ministry Of Fear by Graham Greene -Brighton Rock by Graham Green -A Season in Hell by Arthur Rimbaud -The Street Of Crocodiles (aka Cinnamon Shops) by Bruno Schulz -Opium: The Diary Of His Cure by Jean Cocteau -The Lost Weekend by Charles Jackson -Howl by Allen Ginsberg -Women In Love by DH Lawrence -The Tempest by William Shakespeare -Trilby by George du Maurier -The Vision Of Jean Genet by Richard Coe -"Literature And The Crisis" by Isaiah Berlin -Le Cid by Pierre Corneille -The Paris Peasant by Louis Aragon -Junky by William S Burroughs -Absolute Beginners by Colin MacInnes -Futz by Rochelle Owens -They Shoot Horses Don't They? by Horace McCoy -"An Inquiry On Love" by La revolution surrealiste magazine -Idea by Michael Drayton -"The Nymph's Reply to The Shepherd" by Sir Walter Raleigh -Hamlet by William Shakespeare -The Silver Shilling/The Old Church Bell/The Snail And The Rose Tree all by Hans Christian Andersen -120 Days Of Sodom by Marquis de Sade -Letters To A Young Poet by Rainer Maria Rilke -Poetics Of Space by Gaston Bachelard -In Favor Of The Sensitive Man and Other Essays by Anais Nin -La Batarde by Violette LeDuc -Lolita by Vladimir Nabokov -Intimate Journals by Charles Baudelaire -Juno And The Paycock by Sean O'Casey -England Is Mine by Michael Bracewell -"The Prelude" by William Wordsworth -Noise: The Political Economy of Music by Jacques Atalli -"Elm" by Sylvia Plath -"I am pleased with my sight..." by Rumi -She Stoops To Conquer by Oliver Goldsmith -Amphitryon by John Dryden -Oscar Wilde by Richard Ellman -The Song Of The South by James Rennell Rodd -In Her Praise by Robert Graves -"For That He Looked Not Upon Her" by George Gascoigne -"Order And Disorder" by Lucy Hutchinson -Man Crazy by Joyce Carol Oates -A Pictorial History Of Sex In The Movies by Jeremy Pascall and Clyde Jeavons -Anarchy State & Utopia by Robert Nozick -"Limbo" by Samuel Taylor Coleridge -Men In Love: Masculinity and Sexuality in the Eighteenth Century by George Haggerty

[arbitrary line break because tumble hates lists apparently]

-Crime And Punishment by Fyodor Dostoevsky -Innocent When You Dream: the Tom Waits Reader -"Identity Card" by Mahmoud Darwish -Ulysses by James Joyce -The Four Quartets poems by TS Eliot -Julius Caesar by William Shakespeare -A'Rebours/Against The Grain by Joris-Karl Huysmans -Prisoner Of Love by Jean Genet -Down And Out In Paris And London by George Orwell -The Man With The Golden Arm by Nelson Algren -Revolutionary Road by Richard Yates -"Epitaph To A Dog" by Lord Byron -Cocaine Nights by JG Ballard -"Not By Bread Alone" by James Terry White -Anecdotes Of The Late Samuel Johnson by Hester Thrale -"The Owl And The Pussycat" by Edward Lear -"Chevaux de bois" by Paul Verlaine -A Strong Song Tows Us: The Life of Basil Bunting by Richard Burton -Don Quixote by Miguel de Cervantes -The Divine Comedy by Dante Alighieri -The Jungle Book by Rudyard Kipling -The Man Who Would Be King by Rudyard Kipling -Ask The Dust by John Frante -On The Trans-Siberian Railways by Blaise Cendrars -The 39 Steps by John Buchan -The Overcoat by Nikolai Gogol -The Government Inspector by Nikolai Gogol -The Iliad by Homer -Heart Of Darkness by Joseph Conrad -The Volunteer by Shane O'Doherty -Twenty Love Poems and A Song Of Despair by Pablo Neruda -"May Banners" by Arthur Rimbaud -Literary Outlaw: The life and times of William S Burroughs by Ted Morgan -The Penguin Dorothy Parker -Smoke by William Faulkner -Hero And Leander by Christopher Marlowe -My Lady Nicotine by JM Barrie -All I Ever Wrote by Ronnie Barker -The Libertine by Stephen Jeffreys -On Murder Considered As One Of The Fine Arts by Thomas de Quincey -The Void Ratio by Shane Levene and Karolina Urbaniak -The Remains Of The Day by Kazuo Ishiguro -Dead Fingers Talk by William S Burroughs -The England's Dreaming Tapes by Jon Savage -London Underworld by Henry Mayhew

116 notes

·

View notes

Note

Salut et Fraternité, my dear Citizen George - (that you pretend to the title of Lord I am aware, but I cannot acknowledge aristocratic pretensions; as for my addressing you by christian rather than last name, you will agree it is much more comic.) For an Englishman, your sentiments appear tolerably reasonable, and your letters are certainly amusing; however, I have a strong objection to make to your mentioning Monsieur de Chevalier Saint Just within them and never once mentioning me, despite the fact it is quite clear to any with the least knowledge of the fashions and intellectual currents of this age that your Style is conspicuously derived from mine! In order to demonstrate this point beyond question, let me draw your attention to the portrait of myself by Citizen Joseph Boze: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Camille_Desmoulins#/media/File:Camille_Desmoulins_-_Joseph_Boze.png.

You here perceive, unless you are quite as blind and as provincial as Polyphemus, serpentine and lightly disheveled dark curls, a melancholy and brooding air, a distinctly classical nose and mouth, a luminous and restless eye, and a frilled necktie half-hidden by the shadows of the palette, which catch up and intensify the dim mystery of the sitter; all of which, mon cher Christmas (as such, I have been informed, is the name you prefer to go by), are now ignorantly termed to be Byronic attributes, as if no one but George Gordon Noel Byron, 6th Baron Byron, had ever employed them! Add to this your scathing wit, your appreciation of the glories of the Ancients, your predilection for writing with a hangover, your swiftly-shifting humours of unseasonable gaiety and black despair, your habit of throwing your countrymen into fits of puzzlement and concern and incurring banishment for carmen et error, and it becomes a simple case of plagiarism! You may think yourself extremely Original in engaging in incest, calculating, no doubt, that I would not have had time for the pursuit in the midst of all my patriotic duties, but if that is the only defence you can find it will not do at all. You had better reply with all haste, as I already have a philippic forming in my head, and if I grow bored in the interim, or simply become very attached to the phrases, you shall not be able to prevent me from publishing it.

Yours with slanderous intent,

@thelanterneattorney

Dear God, what a veritable wall of words! I doubt any poor fellow was before presented with his faults in such a devilish involved manner - & I am used to missives that look like essays - my lovers send them all too oft - & usually burn the fattest ones when my debts disallow coals. Heigho, pistols at dawn et al it is then! Let us see if I can make a sentence string together well enough in prose to answer this, without becoming more ennuyé than is usual of that yawning verb.

Firstly: George?! Of all the conjugations of my name, that one has fallen into such a disrepute that it is almost as obscure as the locative & about as oft used. You hardly insult me - simply perplex, which seems your usual mode of carrying on - & to be addressed as a citizen of a republic I admire & who gave birth to the new Caesar can be taken as nothing save a compliment! I had far rather be French, Italian or Grecian than inhabit ye nook-shotten isle of the stinking corporal Arthur. However, I beg to correct your assumption of my nationality - I was born & raised in Aberdeen, & as such am more Scots than English - & ask you to to at least use Geordie, if you must be so damn familiar.

Next, my correspondence: aforementioned reference to the Chevalier Saint-Just is not within my letters - which would be a plain case of traitorous friends - of which I have many - or traitorous lovers - of which devils there are still more - but it makes up an entry in mine journal from 1813-14. This suggests burglary - Massena @chicksncash, if you helped him I swear by Jove to call you out! - which is far more concerning when coming from a rather insane journaliste. I believe property is sacred under your Declaration of the Rights of Man &c, & so if you would give me back my deuced scribblings, I would be grateful.

Yon portrait is lacking from ye missive, so I shall ask Teresa to aid me in supplying a copy of it alongside one of my own, for comparison:

'Pon the subject of my supposed plagiarismes: My curls are certainly not serpentine - simply charmingly windswept, as is to be expected from traipsing about in sublimity - & bear not the lightest resemblance to ye ancient tempted the Serpent, being far too short. As for this melancholia of air - Phah! I have no such sullen countenance as yours - although I am a devil in a mood - nor do I look upon death's door with consumption. Yon "dim mystery of the sitter" is certainly the kind of trash dear Polly-Dolly would write about me, but is hardly apropos from a man of some literary talent. This Byronic air you speak of is hardly the depression of the incarcerated firebrand, as is evident in your portrait, but simply the inevitable absence of ye world traveller pondering the mountains & smoking.

I admit that I gain some attributes of my manner of carrying on from you, but is not imitation the sincerest form of flattery? If ayne fellow of talent - @franzliszt-official for example - came up to me with a reputation for imitating my mannerisms, I should offer him hock & soda on ye spotte! My only defence for stealing your gay moods & melancholia is that I found you fascinating as an infant, & something about your heroism must have wormed into my unformed mind to lodge there.

Your final point is one no gentleman would make, let alone acknowledge. I do not know what that harpy my wife has been saying, but her words are driven by spite and disappointment in my "failure to reform", & are not worth their damn salt. You would do well to refrain from mentioning such toss again.

Yr humble servante,

Byron.

#chit chat over coffee#frevblr#frev rp#napoleonic rp#napoleonic era#napoleonic roleplay scene#lord byron#george gordon byron#camille desmoulins#the leaf journaliste

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

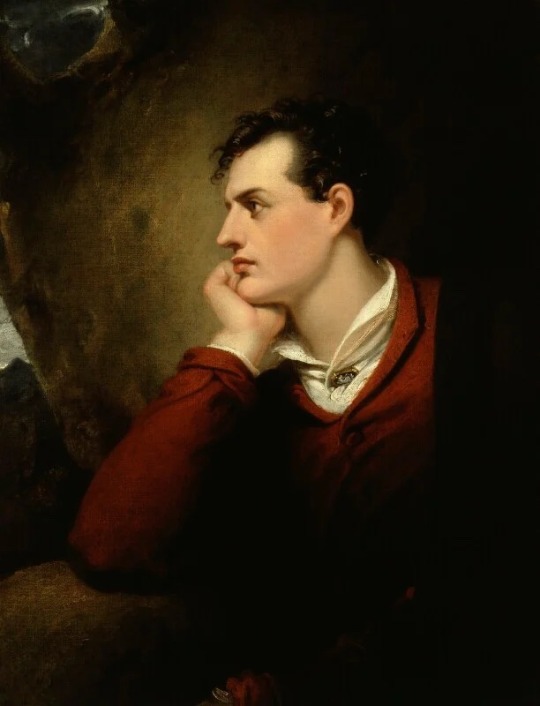

Historians identify lost portrait of Shelley painted days before his death

The poet Percy Bysshe Shelley has been identified in a portrait painted by an artist who met him just days before his death by drowning off the Italian coast in 1822, aged just 29.

It was created by William Edward West, the American painter, who had been struck by Shelley’s good looks while on a visit to paint Lord Byron in Tuscany.

Professor Andrew Stauffer, who has conducted the research, told The Telegraph: “This portrait captures Shelley just before his death. We don’t have better portraits of him.”

He believes that its modest size - 7.25 inches by 9.25 inches - may explain why it eluded notice before an American academic, Newman Ivey White, decided in the 1940s that it actually depicted Leigh Hunt, the English essayist, journalist and poet.

Until then, it was accepted as a portrait of Shelley, after surfacing in 1905.

Prof Stauffer said: “Then White’s debunking comes along and it disappears. But I’m basically debunking his debunking.”

Shelley had come to Italy to broker an introduction between Hunt and Byron, wanting them to collaborate on a new political poetic journal. They sought Byron’s involvement, both for his money and his fame. Literally a week after Hunt arrived, Shelley drowned after his boat foundered during a stormy return voyage to Lerici.

West later recalled their meeting, telling his nephew: “After seeing Shelley again…, I determined to paint [a] picture of him while his image was fresh in my memory.”

Prof Stauffer is President of the Byron Society of America and head of English at the University of Virginia, in whose library the painting hangs.

‘Misdirected debunking’

He made this discovery while doing research for his forthcoming book, Byron: A Life in Ten Letters, to be published by Cambridge University Press early next year.

He will publish his research in the Keats-Shelley Journal this month.

He points to evidence that West had multiple opportunities to observe Shelley in person. For example, an 1828 article titled Shelley in The Yankee and Boston Literary Gazette features West’s description of Shelley as having “the most wonderful-looking head ever seen alive on our earth”.

Prof Stauffer writes: “Published when Shelley was little known in the United States, this reference to West’s opinion of Shelley’s appearance strikes me with the force of authenticity.”

He argues that “the misdirected debunking” of this painting has “distorted our sense of Shelley’s appearance”, with the result that he has been seen primarily through lesser portraits by amateur artists.

In the newly attributed oil painting, the poet was captured by a professional who had observed him firsthand.

Of the amateur portraits, one is by Amelia Curran, who was so unhappy with her work that she threw it onto the fire, only to rescue it at the last minute.

Prof Stauffer said that putting the West and Curran portraits side by side, one sees similarities such as the straight nose with its elongated nostril, a heavily curved upper lip and a rounded chin.

White had argued that, according to contemporaries, Shelley’s hair was beginning to turn grey in 1822 and that this was absent from the portrait.

Prof Stauffer writes: “Perhaps White never saw the West portrait in person and could not see in reproductions the grey, which is plainly visible in the painting.”

— The Telegraph, 23 September 2023

#BYSSHE!#percy bysshe shelley#percy shelley#art#painting#art history#william edward west#william west#poet#english#american#19th century#19th century painting#shelley#west

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

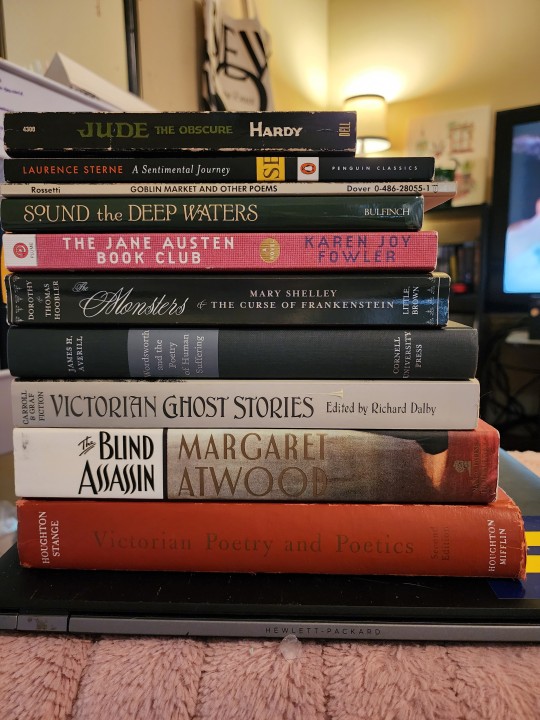

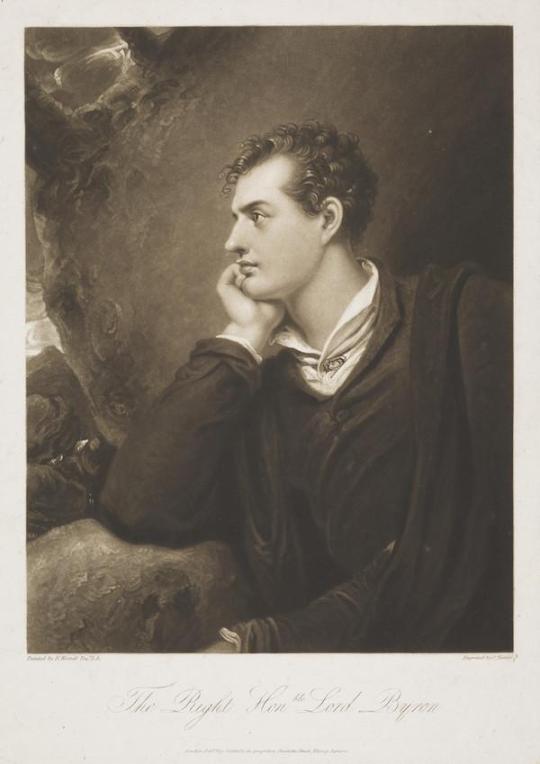

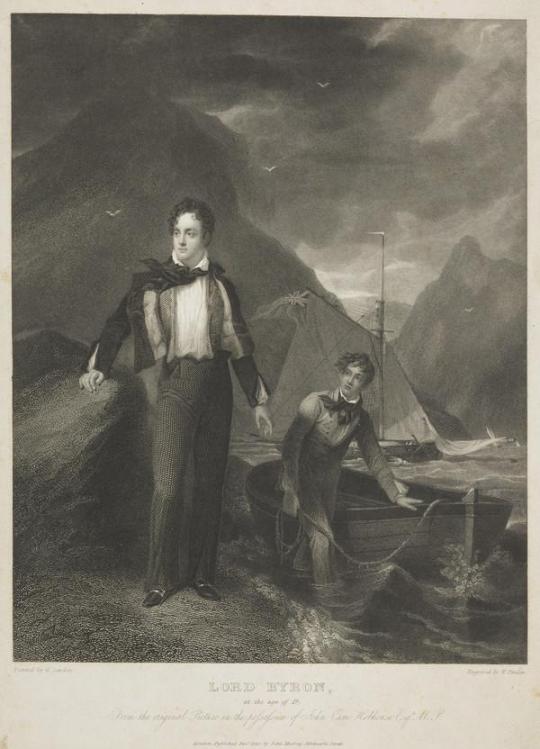

January 22nd 1788 the poet George Gordon Byron, better known as Lord Byron was born in Holles Street, London

Lord Byron’s mother was Scottish, and for his first ten years they lived in Aberdeen, where he attended the Grammar, until he succeeded to his title. He always considered himself a Scot. He wrote in Don Juan: ‘But I am half a Scot by birth, and bred /A whole one, and my heart flies to my head…’

The most glamorous member of the second generation of Romantic poets, he was a prolific writer, led a scandalous life, and died in the Greek war of independence, aged 34. . Apart from his short lyrics, his poetry is perhaps less read now than his extraordinarily vivid letters and journals; his life continues to intrigue readers, scholars and film-makers.

Of course the Scots remember him for the brilliant poem Lochnagar, a favourite of my friend Roland, adapted into a folk song by The Corries, but I am going to post another of his “Scottish” poems called When I Roved A Young Highlander.

When I roved a young Highlander o'er the dark heath,

And climb’d thy steep sumrnit, oh Morven of snow!

To gaze on the torrent that thunder’d beneath,

Or the mist of the tempest that gather’d below,

Untutor’d by science, a stranger to fear,

And rude as the rocks where my infancy grew,

No feeling, save one, to my bosom was dear

Need I say, my sweet Mary, 'twas centred in you?

Yet it could not be love, for I knew not the name,-

What passion can dwell in the heart of a child?

But still I pereceive an emotion the same

As I felt, when a boy, on the crag cover’d wild:

One image alone on my bosom impress’d

I loved my bleak regions, nor panted for new;

And few were my wants, for my wishes were bless’d;

And pure were my thoughts, for my soul was with you.

I arose with the dawn; with my dog as my guide,

From mountain to mountain I bounded along

I breasted the billows of Dee’s rushing tide,

And heard at a distance the Highlander’s song:

At eve, on my heath-cover’d couch of repose,

No dreams, save of Mary, were spread to my view;

And warm to the skies my devotions aoose,

For the first of my prayers was a blessing on you.

I left my bleak home, and my visions are gone;

The mountains are vanish’d, my youth is no more;

As the last of my race, I must wither alone,

And delight but in days I have witness’d before:

Ah! splendour has raised but embitter’d my lot;

More dear were the scenes which my infancy knew:

Though my hopes may have fail’d, yet they are not forgot;

Though cold is my heart, still it lingers with you.

When I see some dark hill point its crest to the sky,

I think of the rocks that o'ershadow Colbleen

When I see the soft blue of a love-speaking eye

I think of those eyes that endear’d the rude scene;

When, haply, some light-waving locks I behold,

That faintly resemble my Mary’s in hue,

I think on the long, flowing ringlets of gold,

The locks that were sacred to beauty, and you.

Yet the day may arrive when the mountains once more

Shall rise to my sight In their mantles of snow:

But while these soar above me, unchanged as before

Will Mary be there to receive me? - ah, no!

Adieu, then, ye hills, where my childhood was bred!

Thou sweet flowing Dee, to thy waters adieu!

No home in the forest shall shelter my head,–

Ah! Mary, what home could be mine but with you?

The statue in the pics is at Aberdeen Grammar School,

12 notes

·

View notes

Note

I think you've mentioned once that there was something fucky going on with Mary Shelley's gender. Where were you looking to find that? Is it in her journals? letters? I'm looking for a place to start.

I don’t remember if I said there was any solid evidence about Mary Shelley’s gender being fucky per se, but:

1. Frankenstein is a HEAVILY transmasculine book, like to an absurd degree. It’s possible that the transmasculine subtext was created by synthesizing a masculine viewpoint to stand in for “feminine” issues however (difficult pregnancies, presumed fragility in health/mind, incestuous abuse) because the issues were not safe for her to write about. For example, the incest issues in Frankenstein are buried while in her next book chronologically, Mathilda, was not, and it was not allowed to be published until the 1900s because her father blocked publication. The fact that Frankenstein managed to get, and still managed to get, so much under the radar makes me wonder if her viewpoint came from any self-knowledge.

2. Mary Shelley was friends with trans man and writer David Lyndsay/Walter Sholto Douglas, who she met after the first edition of Frankenstein (1818) was released, and he was sick with some kind of physical and mental illnesses and died before the more widely released 3rd edition (1831), which has been criticized for making Victor Frankenstein too sympathetic. And by “friends” I mean she engaged in a harebrained scheme to forge him and his wife papers so he would legally be a man when they moved to Paris, so, you know, grade A allyship from Mary Shelley. Anyway, the character of Victor is widely attributed to Percy Shelley and Lord Byron and him becoming more sympathetic has been attributed to changing social mores and the stage play but I’d be VERY curious if any of Lyndsay/Douglas made it in there, though this would take a shitton of research and my life has been too much of a garbage fire to get into this right now.

3. There could be stuff I’m forgetting but again, my life, garbage fire, etc. if anyone else has a suggestion here, I’d be very grateful.

So, anyone?

#frankenstein#victor frankenstein#transgender#transmasculinity#mary shelley#David lyndsay#Walter sholto Douglas#trans man#transmasc#transmasculine#questions

82 notes

·

View notes

Text

My former English professor is retiring and gave away a bunch of the books in her office. She's a gem. I giddily returned to campus just to sort through her collection. Super excited about the ones I brought home with me. I thought someone else might appreciate some of the books I found.

I've already began poring over the poetry collections, but what should I read first? Are there any that you guys have read that you highly recommend?

Books included in Photo 1:

● Sense and Sensibility by Jane Austen (Alta Edition includin Persuasion)

● Robert Burns by David Daiches

● Far From the Madding Crowd by Thomas Hardy

● Leigh Hunt's What is Poetry? by Albert S. Cook

● Love Letters Between a Nobleman and His Sister by Aphra Behn

● Virginia Woolf: A Biography by Quentin Bell

● Holy Madness: Romantics, Patriots, and Revolutionaries 1776-1871 by Adam Zamoyski

● Earnest Victorians by Robert A. Rosenbaum

● Lord Byron: Selected Letters and Journals by Lord Byron, Leslie A. Marchand (Editor)

Books Included in Photo 2:

● Orlando by Virginia Woolf

● Brave New World by Aldous Huxley

● The Portable Irish Reader, (The Viking portable library) by Diarmuid Russell

● The Last Days of Pompeii by Edward Bulwer-Lytton

● Becoming a Heroine by Rachel M. Brownstein

● To the Lighthouse Virginia Woolf

● East Lynne by Ellen Wood, writing as Mrs Henry Wood

● Poetry and Prose of Alexander Pope edited by Aubrey Williams

● In Memoriam; An Authoritative Text, Backgrounds and Sources, Criticism (Norton Critical Editions) by Alfred Tennyson

● Daughters and Fathers by Lynda E. Boose, Betty S. Flowers

Books Included in Photo 3:

● Jude the Obscure by Thomas Hardy

● A Sentimental Journey by Laurence Sterne

● Goblin Market and Other Poems by Christina Rossetti (Dover Thrift Editions)

● Sound the Deep Waters: Women's Romantic Poetry in the Victorian Age includes works by Christina Rossetti, Elizabeth Barrett Browning, George Eliot, Alice Meynell, and Edith Nesbit

● The Jane Austen Book Club by Karen Joy Fowler

● The Monsters: Mary Shelley and the Curse of Frankenstein by Thomas Hoobler and Dorothy Hoobler

● Wordsworth and the Poetry of Human Suffering by James H. Averill

● Victorian Ghost Stories: By Eminent Women Writers (Part of the The Virago Book Series) edited by Richard Dalby

● The Blind Assassin by Margaret Atwood

● Victorian Poetry and Poetics by Walter E. Houghton G. Robert

#bookish#bookworm#books#book haul#booklr#book tumblr#books and literature#booklover#booksbooksbooks#books & libraries#bookblr#book blog#women reading#reading#literature#english literature#literary fiction#literary#margaret atwood#jane austen#thomas hardy#virginia woolf#my library#from the library of nikki howard#fromthelibraryofnikkihoward

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

a something of loose ends, words, looks, there was no retrieving

a something of trouble and unease as it were black scratches on rough plaster ₁ such a lot of loose ends ₂ I could extract a something, of, at least ₃ in new series of invention. Yet a something of consistency ₄ and a something of interest ₅ that’s the mystery. A few pence wrong in our accounts seemed to unfold to me a something of the purpose and aim of life, of which I had been till then ignorant ₆ a something of a string-halt in the bargain, I need hardly say ₇ seems to mount up to quite a lot of money in twenty years. Or was it not rather that a something of which they were both conscious, and that had lain concealed; as an apparently dead dry stick in Eastern lands ₈ in quo etiam erat aliquis quaestus; in which lay a something of gain ₉ Compound interest, whatever that may be ₁₀ and a something of self in all their speculations ₁₁ She did not know. ₁₂

—

sources (their respective details at the more’s)

1 ex google books snippet view, page 95 somewhere in Vol. 5 (1966), The Dublin Magazine / more 2 this and other italicized passages from E. H. Young, Celia (1937) : 57 digitallibraryindia copy/scan, via archive.org / link Virago Modern Classics edition (introduction by Lynn Knight), borrowable at archive.org / link 3 entry for January 28, 1821, in Letters and Journals of Lord Byron : With Notices of His Life, by Thomas Moore. Complete in one volume. (Paris, 1831) / more 4 review of Francis Lathom, his The Fatal Vow; or, St. Michael’s Monastery (1807) in The Annual Review for 1807 (London, 1808) / more 5 Mrs. Kelly, The Fatalists; or, Records of 1814 and 1815. A Novel. (London, 1821) / more 6 The Fortunes of Woman : Memoirs, Edited by Miss Lamont. (London, 1849) / more 7 Texas and the Gulf of Mexico; or, Yachting in the New World, by Mrs. Houstoun (Philadelphia, 1845) / more 8 A Chequered Life by Mrs. Day (London, 1878) / more 9 Richard Horton Smith, Conditional Sentences in Greek and Latin, for the use of students (London, 1894) / more 10 E. H. Young, Celia (1937) : 117 digitallibraryindia copy/scan, via archive.org / link Virago Modern Classics edition, borrowable at archive.org / link 11 ex letter dated November 10, 1822, in Letters and Journals of Lord Byron (Paris, 1831), op. cit. / more 12 “She did not know. There seemed to be no clearness or simplicity in any human emotion, and life, which ought to have been noble, was cluttered with mistakes, words, looks, there was no retrieving. But, she thought, they might with patience, with care and courage, be overlaid by something better. But had she, did she want to exercise the patience and care and courage? Again, she did not know and her musings were interrupted by an imperative ring and knock.” “She opened the door to a telegraph boy.” — E. H. Young, Celia (1937) : 333 digitallibraryindia copy/scan, via archive.org / link Virago Modern Classics edition, borrowable at archive.org / link

20250313

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

swans butterflies bees pollen flowers nature wind seasons transitions blooming green yellow blue pink red lilac Greece Zeus Eros/Psyche Odysseus/Penelope Leander Aphrodite fantasies gardens carriages mirrors emeralds candles shadows spotlights journals letters gossip writing purpose cake

kiss curls, pirate coat, red ring, dance cards, corset pro, bodice ripping?

dual identities, relationship parallels, romance romance romance, rom coms, friends to lovers, Lord Byron.

You are Pen.

Wake up Colin.

What.

A.

Barb.

#here we go#polin season#bridgerton#polin#i hope my walls are thick enough to muffle my screams#assuredly fervently loudly

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

MORTIMER ADLER’S READING LIST (PART 2)

Reading list from “How To Read a Book” by Mortimer Adler (1972 edition).

Alexander Pope: Essay on Criticism; Rape of the Lock; Essay on Man

Charles de Secondat, baron de Montesquieu: Persian Letters; Spirit of Laws

Voltaire: Letters on the English; Candide; Philosophical Dictionary

Henry Fielding: Joseph Andrews; Tom Jones

Samuel Johnson: The Vanity of Human Wishes; Dictionary; Rasselas; The Lives of the Poets

David Hume: Treatise on Human Nature; Essays Moral and Political; An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding

Jean-Jacques Rousseau: On the Origin of Inequality; On the Political Economy; Emile, The Social Contract

Laurence Sterne: Tristram Shandy; A Sentimental Journey through France and Italy

Adam Smith: The Theory of Moral Sentiments; The Wealth of Nations

Immanuel Kant: Critique of Pure Reason; Fundamental Principles of the Metaphysics of Morals; Critique of Practical Reason; The Science of Right; Critique of Judgment; Perpetual Peace

Edward Gibbon: The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire; Autobiography

James Boswell: Journal; Life of Samuel Johnson, Ll.D.

Antoine Laurent Lavoisier: Traité Élémentaire de Chimie (Elements of Chemistry)

Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, and James Madison: Federalist Papers

Jeremy Bentham: Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation; Theory of Fictions

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe: Faust; Poetry and Truth

Jean Baptiste Joseph Fourier: Analytical Theory of Heat

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel: Phenomenology of Spirit; Philosophy of Right; Lectures on the Philosophy of History

William Wordsworth: Poems

Samuel Taylor Coleridge: Poems; Biographia Literaria

Jane Austen: Pride and Prejudice; Emma

Carl von Clausewitz: On War

Stendhal: The Red and the Black; The Charterhouse of Parma; On Love

Lord Byron: Don Juan

Arthur Schopenhauer: Studies in Pessimism

Michael Faraday: Chemical History of a Candle; Experimental Researches in Electricity

Charles Lyell: Principles of Geology

Auguste Comte: The Positive Philosophy

Honore de Balzac: Père Goriot; Eugenie Grandet

Ralph Waldo Emerson: Representative Men; Essays; Journal

Nathaniel Hawthorne: The Scarlet Letter

Alexis de Tocqueville: Democracy in America

John Stuart Mill: A System of Logic; On Liberty; Representative Government; Utilitarianism; The Subjection of Women; Autobiography

Charles Darwin: The Origin of Species; The Descent of Man; Autobiography

Charles Dickens: Pickwick Papers; David Copperfield; Hard Times

Claude Bernard: Introduction to the Study of Experimental Medicine

Henry David Thoreau: Civil Disobedience; Walden

Karl Marx: Capital; Communist Manifesto

George Eliot: Adam Bede; Middlemarch

Herman Melville: Moby-Dick; Billy Budd

Fyodor Dostoevsky: Crime and Punishment; The Idiot; The Brothers Karamazov

Gustave Flaubert: Madame Bovary; Three Stories

Henrik Ibsen: Plays

Leo Tolstoy: War and Peace; Anna Karenina; What is Art?; Twenty-Three Tales

Mark Twain: The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn; The Mysterious Stranger

William James: The Principles of Psychology; The Varieties of Religious Experience; Pragmatism; Essays in Radical Empiricism

Henry James: The American; ‘The Ambassadors

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche: Thus Spoke Zarathustra; Beyond Good and Evil; The Genealogy of Morals; The Will to Power

Jules Henri Poincare: Science and Hypothesis; Science and Method

Sigmund Freud: The Interpretation of Dreams; Introductory Lectures on Psychoanalysis; Civilization and Its Discontents; New Introductory Lectures on Psychoanalysis

George Bernard Shaw: Plays and Prefaces

Max Planck: Origin and Development of the Quantum Theory; Where Is Science Going?; Scientific Autobiography

Henri Bergson: Time and Free Will; Matter and Memory; Creative Evolution; The Two Sources of Morality and Religion

John Dewey: How We Think; Democracy and Education; Experience and Nature; Logic; the Theory of Inquiry

Alfred North Whitehead: An Introduction to Mathematics; Science and the Modern World; The Aims of Education and Other Essays; Adventures of Ideas

George Santayana: The Life of Reason; Skepticism and Animal Faith; Persons and Places

Lenin: The State and Revolution

Marcel Proust: Remembrance of Things Past

Bertrand Russell: The Problems of Philosophy; The Analysis of Mind; An Inquiry into Meaning and Truth; Human Knowledge, Its Scope and Limits

Thomas Mann: The Magic Mountain; Joseph and His Brothers

Albert Einstein: The Meaning of Relativity; On the Method of Theoretical Physics; The Evolution of Physics

James Joyce: ‘The Dead’ in Dubliners; A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man; Ulysses

Jacques Maritain: Art and Scholasticism; The Degrees of Knowledge; The Rights of Man and Natural Law; True Humanism

Franz Kafka: The Trial; The Castle

Arnold J. Toynbee: A Study of History; Civilization on Trial

Jean Paul Sartre: Nausea; No Exit; Being and Nothingness

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn: The First Circle; The Cancer Ward

Source: mortimer-adlers-reading-list

#reading list#long post#mortimer adler#text#saved posts#works#books#so much to read#philosophy#literature#dark academia#light academia

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lord Byron and Napoleon

Someone responded to my Lord Byron post saying they were surprised Lord Byron liked Napoleon. Let’s just say this, Lord Byron was obsessed with Napoleon. He was his “alter ego.” He loved him.

Like most of the Romantics, Napoleon was his muse. He was not a propagandist. He was able to write about Napoleon in a nuanced way and explore different aspects. For example, his “Ode Napoleon Buonaparte” is a sharp criticism which expresses his utter disappointment in Napoleon for abdicating. He hated Napoleon for his defeat, but he loved him for his cause.

Lord Byron had a bust of Napoleon since he was a young boy. He modelled his carriage on Napoleon’s carriage. He had engravings of Napoleon in his room and collected mementos of Napoleon long after his death in 1821. He referred to Napoleon as his “little pagod.” People around him said that the vicissitudes of Napoleon’s life affected his personality. He mattered to him a lot. This is what he said in a letter to his friend after Napoleon’s defeat: “I detest the cause and the victors – and the victory.” (Quote source)

He was hard on Napoleon because he believed in him, but he was devotedly loyal. Notice that he died in exile, just like Napoleon. Thomas Medwin explains that Lord Byron admired Napoleon so much that he came to envy him. Like Beethoven, his admiration turned into a desire to replicate. Beethoven once said he wanted “to conquer” the conqueror.

If anyone is interested in learning more about Lord Byron and Napoleon, I’ve provided some links. Any good book about Lord Byron should mention it. But most biographies about Napoleon will not mention it because it was a parasocial relationship for Lord Byron.

Some but not all sources on the topic:

Between Emperor and Exile: Byron and Napoleon (source)

Byron’s Napoleonic Poems (source)

Beethoven, Byron, and Bonaparte - part 1 (source)

Beethoven, Byron, and Bonaparte - part 2 (source)

Lord Byron Reacts to the News - Napoleon's 100 Days (source)

Lord Byron and Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte between the Ode and Waterloo (source)

Journal of the Conversations of Lord Byron […] in the Years 1821 and 1822, By Thomas Medwin (source)

Manuscript of Byron’s additional stanzas to ‘Ode to Napoleon Buonaparte,’ 1814 (source)

#lord Byron#Napoleon#Byron#napoleon bonaparte#english romanticism#napoleonic#romantic#romantic era#romanticism#romantic age#napoleonic era#first french empire#English literature#literature#English lit#19th century#19th century literature#19th century lit#romantic poets#english#English romantic poets#frev#french revolution#france#text post#links#article#poetry#poem#writers and Napoleon

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

Every Instance of Lord Byron Hating On John Keats, Listed in Chronological Order.

“No more Keats I entreat — flay him alive. If some of you don’t I must skin him myself.”

To his publisher John Murray, 12 October 1820:

“‘I’m thankful for your books dear Murray / But why not send Scott’s Monastery?’ the only book in four living volumes I would give a baioccho to see, abating the rest of the same author, and an occasional Edinburgh & Quarterly – as brief Chroniclers of the times. — Instead of this – here are John Keats’s piss a bed poetry – and three novels by God knows whom [..] Pray send me no more poetry but what is rare and decidedly good. — There is such a trash of Keats and the like upon my tables – that I am ashamed to look at them. [..] – I am in a very fierce humour at not having Scott’s Monastery. – You are too liberal in quantity and somewhat careless of the quality of your missives. – [..] No more Keats I entreat – – – flay him alive – if some of you don’t I must skin him myself. There is no bearing the drivelling idiotism of the Mankin. – – – – – [editor’s note: ‘dashes degenerate into scrawl’]”

To his publisher John Murray, 4 November 1820:

“They Support Pope I see in the Quarterly. [Let them] Continue to do so – it is a Sin & a Shame and a damnation – to think that Pope!! should require it – but he does. – – – Those miserable mountebanks of the day – the poets – disgrace themselves – and deny God – in running down Pope – the most faultless of Poets, and almost of men – – the Edinburgh praises Jack Keats or Ketch or whatever his names are; – why his is the Onanism of Poetry — something like the Pleasure an Italian fiddler extracted out of being suspended daily by a Street Walker in Drury Lane – this went on for some weeks – at last the Girl – went to get a pint of Gin – met another, chatted too long – and Cornelli was hanged outright before she returned. Such like is the trash they praise – and such will be the end of the outstretched poesy of this miserable Self-polluter of the human Mind [editor’s note: ‘untranscribable scrawl’]. W. Scott’s Monastery just arrived — many thanks for that Grand Desideratun of the last Six Months.”

Note: “onanism” refers to masturbation.

To his publisher John Murray, 9 November 1820:

“Mr. Keats whose poetry you enquire after — appears to me what I have already said; such writing is a sort of mental masturbation — he is always frigging his Imagination. I don’t mean that he is indecent, but viciously soliciting his own ideas into a state which is neither poetry nor any thing else but a Bedlam vision produced by raw pork and opium.”

Note: “frigging” was slang for masturbation.

To his publisher John Murray, 18 November 1820:

“P.S. — Of the praises of that little dirty blackguard Keates in the Edinburgh — I shall observe as Johnson did when Sheridan the actor got a pension. ‘What has he got a pension? then it is time that I should give up mine!’ — Nobody could be prouder of the praises of the Edinburgh than I was — or more alive to their censure — as I showed in English Bards and Scotch Reviewers — at present all the men they have ever praised are degraded by that insane article. — Why don't they review & praise ‘Solomon's Guide to Health’ it is better sense — and as much poetry as Johnny Keates.”

To his publisher John Murray 26 April 1821:

“Is it true – what Shelley writes me that poor John Keats died at Rome of the Quarterly Review? I am very sorry for it – though I think he took the wrong line as a poet – and was spoilt by Cockneyfying and Surburbing – and versifying Tooke’s Pantheon and Lempriere’s Dictionary. I know by experience that a savage review is Hemlock to a sucking author – and the one on me – (which produced the English Bards &c.) knocked me down – but I got up again. Instead of bursting a blood-vessel – I drank three bottles of Claret – and began an answer – finding that there was nothing in the Article for which I could lawfully knock Jeffrey on the head in an honourable way. However I would not be the person who wrote the homicidal article – for all the honour & glory in the World, – though I by no means approve of that School of Scribbling – which it treats upon.”

To Percy Shelley, 26 April 1821:

“I am very sorry to hear what you say of Keats — is it actually true? I did not think criticism had been so killing. Though I differ from you essentially in your estimate of his performances, I so much abhor all unnecessary pain, that I would rather he had been seated on the highest peak of Parnassus than have perished in such a manner. Poor fellow! though with such inordinate self-love he would probably have not been very happy. I read the review of ‘Endymion’ in the Quarterly. It was severe, — but surely not so severe as many reviews in that and other journals upon others.

I recollect the effect on me of the Edinburgh on my first poem; it was rage, and resistance, and redress — but not despondency nor despair. I grant that those are not amiable feelings; but, in this world of bustle and broil, and especially in the career of writing, a man should calculate upon his powers of resistance before he goes into the arena. ‘Expect not life from pain nor danger free, Nor deem the doom of man reversed for thee.’

You know my opinion of that second-hand school of poetry. You also know my high opinion of your own poetry, — because it is of no school. [..] I have published a pamphlet on the Pope controversy, which you will not like. Had I known that Keats was dead — or that he was alive and so sensitive — I should have omitted some remarks upon his poetry, to which I was provoked by his attack upon Pope, and my disapprobation of his own style of writing.”

To Percy Shelley, 30 July 1821:

[First page missing] “The impression of Hyperion upon my mind was – that it was the best of his works. Who is to be his editor? It is strange that Southey who attacks the reviewers so sharply in his Kirk White – calling theirs ‘the ungentle craft’ – should be perhaps the killer of Keats. Kirke White was nearly extinguished in the same way – by a paragraph or two in ‘the Monthly’ – Such inordinate sense of censure is surely incompatible with great exertion – have not all known writers been the subject thereof?”

To his publisher John Murray 30 July 1821:

“Are you aware that Shelley has written an Elegy on Keats, and accuses the Quarterly of killing him?

‘Who killed John Keats? / ‘I,’ says the Quarterly, / So savage and Tartarly; / ‘Twas one of my feats.’ / Who shot the arrow? / ‘The poet-priest Milman / (So ready to kill man), / Or Southey or Barrow.’’

You know very well that I did not approve of Keats’s poetry, or principles of poetry, or of his abuse of Pope; but, as he is dead, omit all that is said about him in any M.S.S. of mine, or publication. His Hyperion is a fine monument, and will keep his name. I do not envy the man who wrote the article; — you Review people have no more right to kill than any other footpads. However, he who would die of an article in a Review would probably have died of something else equally trivial. The same thing nearly happened to Kirke White, who died afterwards of a consumption.”

4 August 1821, to his publisher John Murray:

“You must however omit the whole of the observations against the Suburban School – they are meant against Keats and I cannot war with the dead – particularly those already killed by Criticism. Recollect to omit all that portion in any case.”

To his publisher John Murray, 7 August 1821:

“All the part about the Suburb School must be omitted – as it referred to poor Keats now slain by the Quarterly Review — [..] I have just been turning over the homicide review of J. Keats. – It is harsh certainly and contemptuous but not more so than what I recollect of the Edinburgh R. of ‘the Hours of Idleness’ in 1808. The Reviewer allows him ‘a degree of talent which deserves to be put in the right way’ ‘rays of fancy’ ‘gleams of Genius’ and ‘powers of language’. – It is harder on L. Hunt than upon Keats & professes fairly to review only one book of his poem. – Altogether – though very provoking it was hardly so bitter as to kill unless there was a morbid feeling previously in his system.”

To Thomas Moore, August 27th 1822:

“It was not a Bible that was found in Shelley's pocket, but John Keats's poems.”

From his poem Don Juan Canto Eleventh written October 1822 and published August 1823. He was going off the popular gossip shared to him by Shelley (who believed it), which was that Keats health had sharply declined due to receiving bad reviews:

“John Keats, who was killed off by one critique, / Just as he really promised something great, / If not intelligible, without Greek / Contrived to talk about the Gods of late, / Much as they might have been supposed to speak. / Poor fellow! His was an untoward fate; / ‘Tis strange the mind, that very fiery particle, / Should let itself be snuffed out by an article.”

To his publisher John Murray, 25 December 1822:

“As to any community of feeling, thought, or opinion, between Leigh Hunt and me, there is little or none. We meet rarely, hardly ever; but I think him a good-principled and able man, and must do as I would be done by. I do not know what world he has lived in – but I have lived in three or four – and none of them like his Keats and Kangaroo terra incognita – Alas! poor Shelley! – how he would have laughed – had he lived, and how we used to laugh now & then – at various things – which are grave in the Suburbs. You are all mistaken about Shelley – – you do not know – how mild – how tolerant – how good he was in Society – and as perfect a Gentleman as ever crossed a drawing room; – when he liked – & where he liked. – – – – –“

The excerpts above are taken primarily from Peter Cochran’s transcriptions.

#contrary to stereotypes byron wasn’t always like this - he just rly hated keats’ poetry#literature#english literature#dark academia#lord byron#romanticism#poetry#history#writing#john keats#letters#journals#interesting#1800s#regency era#19th century#english#books#bookblr#authors#writers#gothic literature#romantic literature#romantic poets#keats#byron#feuds#literary history#quotes#excerpts

122 notes

·

View notes

Text

She kept a journal, where his faults were noted, And open’d certain trunks of books and letters, All which might, if occasion served, be quoted; And then she had all Seville for abettors, Besides her good old grandmother (who doted); The hearers of her case became repeaters, Then advocates, inquisitors, and judges, Some for amusement, others for old grudges.

— Lord Byron, Don Juan

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

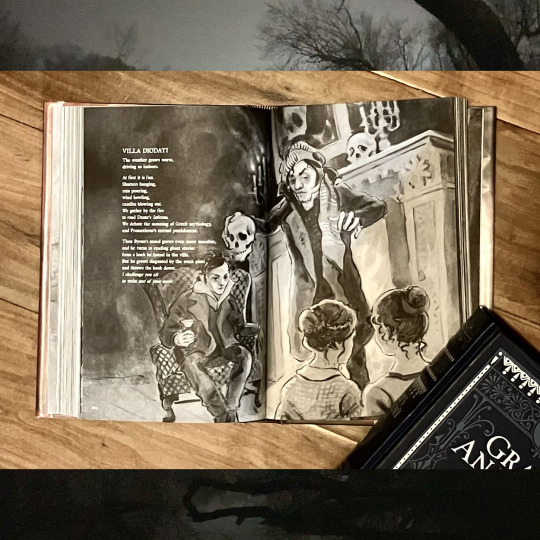

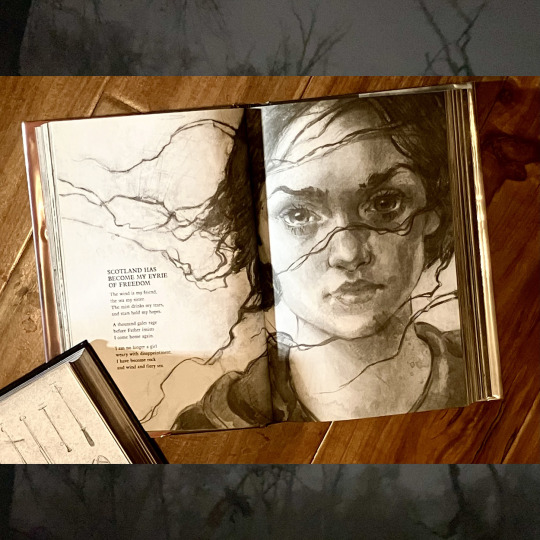

Another book review! I was hoping to post this back in October for spooky season, but work and class got in the way. So I'm posting it now to start off the new year.

MARY'S MONSTER

written and illustrated by Lita Judge

The common story of how Mary Shelley came to write Frankenstein is that she conceived the plot during a ghost-writing contest while she, her lover Percy Bysshe Shelley, and her sister Claire were staying at the manor house of Lord Byron and his personal physician, John Polidori. Some might add that she took inspiration from an experiment in galvanism she had witnessed a few weeks earlier. But Lita Judge’s evocative book, told through prose poetry, posits that the novel grew for many years within Mary’s mind, sewn together from the tragedies and drama of her life. It grew from the deaths that surrounded her: her children; her neglected sister; Percy Shelley’s abandoned first wife; and Mary’s own mother who died giving birth to her. It grew from her feelings of estrangement towards her once-beloved father who did not approve of her romance with the young poet. It grew from the anger of her sister Fanny “shackled by illegitimacy and despair”. And it grew from Percy Shelley’s own growing madness “because society loathes him for his beliefs”. Out of these parts Mary made her creation, so Judge writes, stitching them into a greater whole just as Victor Frankenstein assembled his creature from corpses.

The book is told in first person from Mary’s perspective, giving the reader a personal connection with her pain and her joy. At critical moments the voice of her creature also emerges as an extension of her. A literary child just as precious to her as the biological children she lost.

Central to Mary’s story is her turbulent relationship with Percy Bysshe Shelley. How they came to love each other and fled to Europe to try to build a life through loss, ostracization, and Shelley’s growing mania. Equally important to the narrative is Mary’s relationship with her sister Claire, who travels with the couple and shares in Mary’s pain and joy. And, then, of course the book depicts the fateful ghost-writing contest at Byron’s chateau, when Mary’s creature finally comes to life and speaks with his own voice.

The book gives context to some of the more macabre events in Mary’s life, such as when she first makes love to Shelley on her mother’s grave, or how she rescues his physical heart after he is cremated and keeps it in her writing desk for the rest of her life. Both acts keep her deceased loved ones close to her.

Judge’s evocative black-and-white illustrations accompany and enhance each poem, steeping the book in a gothic aesthetic. This is a passion project for the author, undertaken- as she explains in the afterward- while she struggled with pain, fatigue, and isolation during a long illness. “I have represented the details of Mary’s life,” she writes, “by weaving the actual events (as documented in her journals, copious letters, and later biographies) with the themes she and Shelley wrote about in their creative work.” The author does acknowledge that, although this book draws from facts, it is a dramatization of Mary’s experiences. Judge provides an extensive bibliography for further reading, along with a list of what the characters themselves read, to provide some context for their lives. She also includes short biographical notes of what happened to everyone later in life.

You can get a copy of Mary's Monster at Bookshop.org. Or, like, Amazon if you want.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

{{Hey, all!

My cowriter and I are still on hiatus due to her being in another country and myself working towards an English MA acceptance letter, a long process that's taken me all over the world and will likely continue to. I'm a teacher in my daily life these days, which I never would've imagined saying in earnest when I started this blog over 10 years ago! Currently, I'm at the precipice of a career as an academic and cohost a podcast on top of it all, so I haven't been around. Additionally, the host of this blog is a transman, and I've been preparing to medically transition, which while exciting is equally nervewracking and expensive.

I'm far from gone, however. While we are planning to continue our series (which currently sits at a collective 600 pages on A03!), I've decided to start work on a novel - a Victorian gothic queer enemies to lovers sort of passion project. It sits as my magnum opus, it's absolutely inspired by our series, and the hope is for it to actually hit store shelves. I've been published as a teen, in the occasional journal or local publication, and I'm coming to the realization that the ONLY thing stopping me is my own nerves. So, I'll lurk, occasionally update the fic and hopefully one day allow my boy his full story, and start a new one with a new set of boys who are very much inspired by our beloved boys themselves and a bit of Lord Byron.

Perhaps one day this will be incriminating evidence for who I am

No matter

0 notes

Text

January 22nd 1788 the poet George Gordon Byron, better known as Lord Byron was born in Holles Street, London

Lord Byron’s mother was Scottish, and for his first ten years they lived in Aberdeen, where he attended the Grammar, until he succeeded to his title. He always considered himself a Scot. He wrote in Don Juan: ‘But I am half a Scot by birth, and bred /A whole one, and my heart flies to my head…’

The most glamorous member of the second generation of Romantic poets, he was a prolific writer, led a scandalous life, and died in the Greek war of independence, aged 34. . Apart from his short lyrics, his poetry is perhaps less read now than his extraordinarily vivid letters and journals; his life continues to intrigue readers, scholars and film-makers.

Of course the Scots remember him for the brilliant poem Lochnagar, a favourite of my friend Roland, adapted into a folk song by The Corries, but I am going to post another of his “Scottish” poems called When I Roved A Young Highlander.

When I roved a young Highlander o'er the dark heath,

And climb’d thy steep sumrnit, oh Morven of snow!

To gaze on the torrent that thunder’d beneath,

Or the mist of the tempest that gather’d below,

Untutor’d by science, a stranger to fear,

And rude as the rocks where my infancy grew,

No feeling, save one, to my bosom was dear

Need I say, my sweet Mary, 'twas centred in you?

Yet it could not be love, for I knew not the name,-

What passion can dwell in the heart of a child?

But still I pereceive an emotion the same

As I felt, when a boy, on the crag cover’d wild:

One image alone on my bosom impress’d

I loved my bleak regions, nor panted for new;

And few were my wants, for my wishes were bless’d;

And pure were my thoughts, for my soul was with you.

I arose with the dawn; with my dog as my guide,

From mountain to mountain I bounded along

I breasted the billows of Dee’s rushing tide,

And heard at a distance the Highlander’s song:

At eve, on my heath-cover’d couch of repose,

No dreams, save of Mary, were spread to my view;

And warm to the skies my devotions aoose,

For the first of my prayers was a blessing on you.

I left my bleak home, and my visions are gone;

The mountains are vanish’d, my youth is no more;

As the last of my race, I must wither alone,

And delight but in days I have witness’d before:

Ah! splendour has raised but embitter’d my lot;

More dear were the scenes which my infancy knew:

Though my hopes may have fail’d, yet they are not forgot;

Though cold is my heart, still it lingers with you.

When I see some dark hill point its crest to the sky,

I think of the rocks that o'ershadow Colbleen

When I see the soft blue of a love-speaking eye

I think of those eyes that endear’d the rude scene;

When, haply, some light-waving locks I behold,

That faintly resemble my Mary’s in hue,

I think on the long, flowing ringlets of gold,

The locks that were sacred to beauty, and you.

Yet the day may arrive when the mountains once more

Shall rise to my sight In their mantles of snow:

But while these soar above me, unchanged as before

Will Mary be there to receive me? - ah, no!

Adieu, then, ye hills, where my childhood was bred!

Thou sweet flowing Dee, to thy waters adieu!

No home in the forest shall shelter my head,–

Ah! Mary, what home could be mine but with you?

22 notes

·

View notes