#legacy of the fire nation critical

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The author of Legacy of the Fire Nation admitted in a tweet that they weren't allowed to reveal anything that hadn't already been shown on-panel or on-screen. In fact, here is a screenshot for reference.

Imo, I treat it like a post-Smoke and Shadow Iroh upset that Azula took advantage of him pushing Aang to allow her to go on the search for Ursa on her terms to not only almost kill Ursa, but also then become a world-class terrorist bent on turning Zuko into a tyrant like their forefathers before them.

It's like when he said, "She's crazy and needs to go down." after Azula almost killed him and Azula. He could have said it better, but he is human after all, no matter how his stans deify him.

Seriously?! First Iroh pins the blame on Azula and now this unflattering portrait of her?!!!!

Whoever wrote this BS forgot to drink their Respect Women juice.

#iroh#alta comics#legacy of the fire nation#iroh meta#atla comics meta#legacy of the fire nation meta#legacy of the fire nation critical

132 notes

·

View notes

Note

Can I hear your opinions on rita skeeter?

You know how some stories have that only sane man, the one person who isn't impressed by our dashing main characters or who's living in a different genre and rated story? The one, typically a fan favorite, character who has a fundamentally different perspective. They can also, shortly put, be the "this is stupid and you're stupid" character.

The NBC Hannibal show has Freddie Lounds ("I'm a bad, bad man", Will threatens her. He is then surprised when she runs a feature on the FBI hiring a creep to come to crime scenes and pretend he's a serial killer.) The Vampire Diaries had Elijah (he isn't a great example of this, but legacy fans will remember all the jokes about how the reason the writers never put him in episodes was because he'd have solved all the characters' stupid problems within twenty minutes and there would be no plot for the rest of the season. Elijah was perceived to be living in a different type of show than the rest of the teen drama cast), and there are some who think that this was Snape for Harry Potter.

They are wrong.

Rita, my dove

Let's take a look at a few things Rita prints over the course of canon, where we have an insight into what actually happened and know precidely what she printed. I have my copy of Goblet of Fire with me, it's in Norwegian so I'll be translating back to English but I trust that's alright.

The Quidditch world cup incident

What we know happened:

The British Ministry was responsible for the event. It was highly prestigious, with foreign leaders attending and people from all over the world camped out near the stadion. After the first match there's celebrations, which turns into a riot. Tents are set on fire, people are chased through the camp grounds, and there's total chaos where nobody knows where their loved ones are. The riot soon turns into a homage to Voldemort, with rioters in Death Eater uniforms tormenting the Muggles living nearby and someone putting up the Dark Mark.

Arthur Weasley, who works in the Department of Misuse of Muggle Artifacts (which is admittedly part of the Department of Magical Law Enforcement), is sent to make a statement on the Ministry's behalf to the terrified witches and wizards hiding.

What Skeeter reports:

Headlining "TERROR AT THE WORLD CUP" (me translating), with an image of the Dark Mark, Rita Skeeter writes (this is Arthur skimming): "Ministry blunders... culprits not apprehended... lax security... Dark wizards running unchecked... national disgrace..." (original English from the wiki)

A full section (and this is me translating again): "If the terrified witches and wizards who waited for information while they hid in the woods had hoped for any sort of reassurance from the Ministry of Magic, they were sorely disappointed. A department spokesman, who only showed up long after the Dark Mark had appeared, claimed no one had been injured but refused to give further information. It remains to be seen if this statement will quell the rumors that several bodies were seen being recovered from the woods an hour later."

Verdict

All of this is accurate, except the last sentence.

Nobody was killed in the incident. However, Skeeter was acting on the information available to her, and she makes it clear this last part is unconfirmed. Further, I'm going to come out in her defense and say that Skeeter, writing an article critical of the Ministry in a community with a very loose sense of free speech, can't take Arthur Weasley at his vague word and should refer to her own sense of judgement when deciding whether the rumors are credible enough to print or not.

As it is, a riot in a crowded area at night with people who dressed like Death Eaters, where the Dark Mark was fired into the sky, where mass panic erupted, in a world where children can produce deadly magic with their wands, could easily have led to casualties. I don't think it was a far leap for Skeeter that people might have died, and the Ministry didn't want to admit as much.

Notice her phrasing (and yes, I know you're reading my translation) when she talks about the Ministry: "It remains to be seen if this statement will quell the rumors that several bodies were seen being recovered from the woods an hour later." Not, "It remains to be seen whether the rumors that several bodies were seen being recovered from the woods an hour later were true.", or any type of phrasing indicating that the truth will out. Only rumors that may or may not be quelled.

Knowing that the Wizarding World doesn't appear to be a functional nor accountable democracy, that things like statistics likely don't exist (who will be your statistician if there is no basic math education? How will wizards interpret statistics if they don't understand basic maths, what use are error margins and percentages to them? This is important, because without statistics there is also no need to collect numbers - how many students take the core classes, how many are employed after X years, how many citizens die in a given year and of what causes... you see where I'm going with this), and that Arthur gets so defensive when reading legitimate criticism of his Ministry (not even his department or jurisdiction, mind, and Skeeter anonymized him), indicates a fraught understanding of governmental accountability and transparency.

In other words, who can say if anybody died that night. Arthur himself had gone to bed with his family as soon as the chaos was under control, and there was no tally after the riot, no controlled evacuation, nothing. Skeeter wasn't wrong for publishing what she herself clarified was speculation, either way I'm hard pressed to see her as a villain for putting the Ministry under pressure, in fact I have to wonder if this kind of pressure is necessary to get them to admit things they'd otherwise shove under the carpet.

Back to Arthur Weasley. In response to this article he says to his family (me translating again): "Molly, I must go to the office. Killing this is going to take some time."

Now, I know real governments have to cry over scandals that take time to move past as well: however, what are people upset over? What's the scandal?

Oh, yes, that the Ministry wasn't able to prevent a riot at a large sports event, flubbed completely once it had begun, and failed to give the people any kind of useful or timely information. All of that is true. The only part that isn't true, would be dispelled if they'd only put out a statement saying "no one was killed". The only reason why one such statement wouldn't work is if Ministry statements are not considered trustworthy - and this is where we return to the above.

So far, so good on Rita Skeeter, and so bad on Arthur who, going by this section, questions the Ministry less than Bellatrix Lestrange questions Voldemort.

Interlude: Percy and the vampires

While the article about the World Cup is read, Percy jumps in with an anecdote about Skeeter.

"That woman is always out to slander the Ministry," Percy said angrily. "Last week she claimed we waster our time fooling around with cauldron thickness when we should be extinguishing vampires! As though it is not expressedly stated in Guidelines for treatment of non-wizard halfhumans that-"

I'm not going to make any guesses as to what precisely Skeeter's criticism was, because Percy is angry and venting to his family, which doesn't make him likely to present her argument fairly. Who knows what, specifically, she criticized and why and what she asked for in her article. What we do know is that she questioned Ministry priorities and resource allotment, and Percy takes it personally, he gets angry about it. Hostility and defensiveness is the gut reaction.

More damningly, "that woman is always out to slander the Ministry" implies no one else is doing it.

Your star is rising, Rita.

Oh no, post got long

And this is the part where I'd go on to her interview with Harry and subsequent articles, and later on Dumbledore, but I'm realizing that would make this post a very long and decentralized mess.

Will cover it in follow up posts: today is for Rita vs. the Ministry and how the Weasleys think Muggles are so quaint with their democracricy and freedom of speech, teehee that's silly.

#rita skeeter#harry potter#harry potter meta#anti arthur weasley#arthur weasley#percy weasley#anti percy weasley

210 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Fire doesn't stop, it blooms."

════════════════════

════════════════════

- Zuko x wife!reader - Head cannons - "Fire doesn't stop, it blooms." - Fluff - Warnings: None

A/N: I'm actually sorry for being gone so long, but things were more complicated in these last few weeks than I would have liked them to be. With all the exams I had, going through a writer's block and losing motivation, I just needed some time to cool off. But I'm back now, and I am hopefully going to stay because I am very excited to take requests in once again!

════════════════════

Honestly, I think he would make a wonderful husband in so many ways. You stood by him through all the struggles and pain, even during the pivotal moment when he had to make a choice that forever changed his role in the war. He’d want to show you just how much that meant to him. Whether through physical affection, thoughtful gifts, or heartfelt words of affirmation, he’d find ways to express his gratitude.

He has a way with words—always knowing just what to say and when to say it. He never hesitates to share his perspective, especially when he thinks you need to see things from a different angle. Pampering you would be second nature to him; he’d see it as his responsibility to make sure you have everything you deserve. And when the sun sets and the moon takes its place in the night sky, there wouldn’t be a single evening where he didn’t remind you of your worth.

That being said, not everything would come as naturally. Having grown up in a household where sharing fears and anxieties was reserved for his mother and uncle, his ability to communicate his own negative emotions is still a work in progress. Losing his mother at a young age and enduring the trauma of a father who criticized any emotion that didn’t meet his expectations shaped him deeply. Opening up about his feelings would take time and effort to improve.

On nights when he dreamed of his mother, he would wake with a shiver running up his spine, his eyes darting around until they found you. Yet, even as fear clawed at his soul, he refused to talk about it. You’d wake to the sound of his uneven breathing, gently calm him, and ask what was wrong. But he would deny it—deny it until the weight of it consumed him from the inside. And for that moment, you understood.

But you reminded him that, as his partner, the two of you were a unit. If your burdens were his to carry, then his were yours as well. You asked him to let you in, to let you help, and you promised to say it as many times as he needed to hear it. On the nights when another nightmare took hold of him, you whispered reassurances and held his hand as lightly as you could. Of course, you weren’t blind to what troubled him—You are his wife. You knew.

Together, you’re working to bring him a sense of security. His father can no longer hurt him; he has you to stand beside him through every hardship, and for him, that is enough. On a brighter note, he would definitely make a much better father himself—caring, affectionate, and present. When you gave him your first child, a little girl, no celebration in the nation could rival his joy. Holding the tiny miracle you both created, sleeping soundly in his arms while you took the well-deserved rest by his side, he couldn’t help but want to linger in that moment just a little while longer.

His little family, safe and sound right beside him, was everything. With the birth of his daughter, he reminded himself that there was now another heart to protect. Much smaller, less experienced, but he could already sense the strength in her—she would grow to be a fighter, just like her mother. This was his legacy: to break the cruel, poisonous chain that had defined his family for generations. He would protect the both of you with his last breath, proving to the spirits of his ancestors that fire doesn’t have to destroy—it can also ignite new beginnings. ════════════════════

A/N: With how tired I am at the moment, I lost complete sense of how much this took to write. It wasn't that long, I think.. But, considering that it is currently 02:40 AM and I have not slept since 12 PM, this was fairly easy to do. I've just been thinking about making this for a bit and decided that this ungodly hour is the perfect moment. I am going to sleep now, but I hope anyone who reads this likes it! - I do NOT give permission for any of my work to be republished on any other sites, or even here. Not Ao3, not Wattpad, nowhere. This is simply for entertainment purposes and I would appreciate respecting this.

#x reader#one shot#like#requests#zuko#atla#atla zuko#zuko x reader#avatar the last airbender#i need sleep#tired

83 notes

·

View notes

Text

In 2019, the American chattering class was atwitter about “cancel culture”: The New York Times reported on its popularity among teenagers; in 2020, Harper’s Magazine published “A Letter on Justice and Open Debate,” whose 153 world-renowned signatories—academics, writers, and artists—worried that a lack of “open debate” over police reform and other issues of social and racial justice was yielding to “dogma or coercion.”

Outside legacy media, cancel culture then became part and parcel of right-wing political agendas, with the End Woke Higher Education Act—which passed the U.S. House of Representatives on Sept. 19—marking one of several “anti-woke” initiatives launched by Republican congressional lawmakers.

A heavily reworked version of a 2022 German book, The Cancel Culture Panic by Adrian Daub offers a historical analysis of the so-called cancel culture moral panic that spread from the United States to the rest of the world. Daub argues that cancel culture is but the latest iteration of discussions of political correctness that emerged in the United States during the administration of former President Ronald Reagan.

Daub’s goal isn’t to catalog. Rather, he wants to reorient our attention and demystify fears in the United States, Europe, and elsewhere, as he believes that “[p]eople talk about cancel culture so that they don’t have to talk about other things, in order to legitimize certain topics, positions, and authorize and delegitimize others.”

Ultimately, Daub argues, hysteria over cancel culture keeps “us from finding solutions we desperately need” to widespread problems “of labor and job security,” the “digital public space,” and “accountability and surveillance.”

Daub begins by arguing that accusations of cancel culture obscure a widening gap between the “objective frequency of the phenomenon and its media presence.” Fears of alleged censorship, of excessive identity politics, and of “wokeness” are, Daub says, disproportionate to verified cancellations.

For example, the individuals who are often affected—for instance, professors at U.S. universities—have lost their jobs not because of cancel culture, but a specific academic or professional dispute. One example: “In 2021, Truckee Meadows Community College in Nevada moved to fire [math professor] Lars Jensen, citing two consecutive unsatisfactory performance reviews that accused him of ‘insubordination,’ among other things.” Specifically, Jensen had distributed “fliers at a state math summit that criticized the college’s math standards—a move Truckee Meadows administrators said disrupted the meeting.”

Cases of real “canceling” in America’s colleges and universities are thus in fact quite low; Daub notes, for example, that “[f]or the year 2021,” his research indicates that just a “total of four” professors “experienced what we would likely see reported in the press as a classic cancel story.” This, despite the conservative National Association of Scholars listing hundreds of cancellations.

Daub argues that “the persuasiveness of cancel culture warnings results from the fact that it insists on suddenness while actually drawing on well-established truisms and conventions.” Historically, he links the panic over cancel culture to fears over political correctness, which—reacting to feminism and the diversification of workplaces and universities—spread in the United States in the early 1990s, above all during the administration of President George H.W. Bush.

But Daub identifies a deeper discursive background: conservative narratives, which first emerged in the 1950s, that imagine U.S. higher education—really, the eight universities that make up the Ivy League—as bastions of “anti-Christian” bias and “anti-individualistic” ideologies.

In these narratives, which Daub argues were produced by members of “think tanks and nonprofit foundations set up by wealthy conservative donors” beginning in the 1970s, leftist academics insidiously swap canonical works—by William Shakespeare, Plato, Homer, and so on—with literature supposedly focused on identity and ethnicity, such as Toni Morrison’s Beloved and Alice Walker’s The Color Purple.

Intersecting with this backdrop, a wave of mainstream publications about political correctness’s apparent tyranny in the academy swept through the United States. These presented the concept sensationally, with “the flavor of the courtroom,” even if those presentations were “nowhere near the truth.”

In fact, Daub argues, a certain type of anecdote about cancel culture—imprecise, brief narratives from questionable sources with a punch line—are told as credible and received as plausible. For example: Psychology professor Jordan Peterson once reported in a viral video that a client of his was a bank employee who spoke of how their bank decided to cease using the term “flip chart” because it could be used “pejoratively to refer to Filipinos.”

Particular features of this and other cancel culture anecdotes develop, disappear, or are replaced with new details; in fact, this anecdote has been circulating since the 1990s, and sometimes features a Filipino gang member at a community panel meeting. Regardless, the more frequently that a cancel culture anecdote is referenced and recounted, the more that it gains credibility, and the more that it further inflames the moral panic over cancel culture.

Daub expands his analysis to our age of globalization—one in which, he argues, cancel culture anecdotes have helped produce moral panic in different global settings, becoming invariably linked to particular national issues, discussions, and societal anxieties.

In Germany, fears intersect with the concern that “left-wing censorship” and “identity politics from the left” will culminate, as theorized in political scientist Josef Joffe’s March 2021 Neue Zürcher Zeitung essay, in an imagined violent and wholesale cultural revolution. In the United Kingdom, cancel culture arrived after Brexit and became, in Daub’s assessment, “at least in part a crutch for managing the shambolic aftermath of the decision to leave.”

And if Europeans obsess about U.S. universities, in Russia and Turkey, Daub writes, “the focus is on popular culture and social media.” In March 2022, for example, Russian President Vladimir Putin compared the West’s reaction to Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine to the supposed cancellation of Harry Potter author J.K. Rowling for her views on transgender people.

In his conclusion, Daub interrogates how “calls for a defense of liberal values” against critical race theory, the so-called woke campus, or cancel culture in publications such as Le Figaro, the Wall Street Journal, and the Atlantic can morph into—or at least indirectly contribute to—illiberal political-governmental restrictions on speech and institutions.

For instance, following the flurry of articles on cancel culture in 2019, Florida Gov. Ron Desantis signed the Stop WOKE Act into state law on April 22, 2022, and positioned himself as a 2024 presidential candidate in part by whipping up hysteria about cancel culture.

But, more broadly, Daub sees the anti-cancel culture movement as advancing a dark and illiberal vision of institutions and society. For him, “figures like the Le Pens [of France], the Trumps [of the United States], [Austria’s] Jörg Haider, [Italy’s] Silvio Berlusconi, [the United Kingdom’s] Boris Johnson, and [Brazil’s] Jair Bolsonaro … retain a certain conservative institutionalism, while they simultaneously participate in the populist/authoritarian degradation of institutions,” and they do this in part through using the tool of the cancel culture panic.

For these leaders, universities teach junk to students; companies go woke and go broke; the military is weak due to diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts; and experts are politically correct drones. All while casting themselves as liberal and tolerant, these illiberal figures construct straw man arguments from the legitimate concerns of minority perspectives and dismiss them as cancel culture; this allows for the powerful and privileged to reinforce political and social hierarchies, uphold majority rule, and crush opposition.

The fact that the cancel culture panic spread to other countries indicates how U.S. soft power remains operative. Nevertheless, despite Daub’s insights into the moral panic in the United States, Europe, and Latin America, he does not, for example, engage with its occurrence in China, where competitive social media platforms, streaming and video platforms, and state-run media outlets drive a “real” version of “cancellation.”

In 2021, for example, there were a series of high-profile celebrity cancellations in China; some transgressors were imprisoned, others not. The latter group included actor Zhang Zhehan, though, in his case, being “canceled” meant losing work and removal from social media platforms: in August 2021, Zhang was “canceled” because of old vacation photos showing Zhang posing with cherry blossoms, which had been taken in the open park area of Japan’s Yasukuni Shrine, which honors Japanese war criminals involved in the atrocities of World War II.

Furthermore, the intense public concern about cancel culture in the United States seems to have modulated itself. One reason might be related to changes in perceptions about the political alignments of Big Tech and social media companies. According to a 2024 study conducted by the Pew Research Center, Americans are overall inclined to see Big Tech corporations as more aligned with liberal than with conservative views. But these views now run up against the reality of Big Tech’s political donations in this year’s U.S. presidential election. “Silicon Valley,” as reported in The Guardian, “poured more than $394.1m into the US presidential election this year,” and most of that—$242.6m—was given by Elon Musk.

Americans’ perceptions of Big Tech corporations also now collide with how changes in the ownership and operation of Big Tech and social media companies have affected platforms, their attention economy, and the way that they circulate information.

It was announced after Musk acquired Twitter in October 2022—which he claimed to do because he wanted to protect “free speech”—that the rechristened “X” would discontinue its policy prohibiting COVID-19 misinformation; at the same time, algorithm changes led to X’s promotion of false viral information about the Russian invasion of Ukraine. The Center for Countering Digital Hate issued a November 2023 report declaring that 98 percent of misinformation, antisemitism, Islamophobia, and other hate speech vis-à-vis the Israel-Hamas war remained publicly viewable on X after a week of notice was given to the social media site.

Meanwhile, in 2023, Twitter—like Meta and Alphabet, the parent companies of Facebook and Google, respectively—dumped a significant number of its content moderators. While Gizmodo reported in 2016 that Facebook workers routinely suppressed conservative news in the “trending topics” section, a recent study published in Science and Nature showed that “[a]udiences who consume political news on Facebook are, in general, right-leaning.” And as reported in El País, 97 percent of links to what Meta’s fact-checkers deem to be “fake” news “circulate among conservative users.” (It’s fair to wonder whether cancel culture memes figure prominently among these links.)

Cancel culture panic’s newest inflections might also be related to a shift in who seeks to do the “canceling”: Rather than only cultural left—which prompted the era of #TimesUp, #MeToo, and Black Lives Matter—the cultural right also now commands public attention. In 2023, conservatives in America “canceled” Bud Light because of a social media promotion by TikTok personality and transgender woman Dylan Mulvaney, and the new Star Wars TV show The Acolyte, because it centered women and people of color.

Will U.S. citizens become fed up with the ways that Big Tech and social media feed panic on both sides of the country’s political divides? According to the aforementioned Pew Research Center study, large majorities of Americans believe that social media companies as possess too much political power and as censor political viewpoints that they reject.

But political will appears to be lacking in the United States to do much about it. In contrast, in August 2023, the European Union enacted the Digital Services Act, which aims to curb online hate, child sexual abuse, and disinformation.

Still, the panic about leftist cancel culture hasn’t so much faded from Americans’ consciousness as it has transformed. The idea of “wokeness” was the primary axis on which U.S. President-elect Trump oriented his latest campaign rhetoric. “Kamala is For They/Them. President Trump is For You,” voters were told in one prominent anti-woke campaign advert.

Now an anti-cancel culture president and his anti-woke cabinet are chomping at the bit. Stephen Miller, Trump’s nominee to become his Homeland Security advisor, launched America First Legal in 2021, filing more than 100 legal actions against “woke corporations” and others. And Musk, who vowed in 2021 to “destroy the woke mind virus,” along with entrepreneur Vivek Ramaswamy, who wrote the 2021 book Woke, Inc.: Inside Corporate America’s Social Justice Scam, were named by Trump to lead a department that aims to “delete” aspects of the U.S. federal government deemed too costly.

One shudders at the possibility that other liberal democracies will follow the path of cancel culture panic as far as the United States now has.

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yep. They just ruin his character by doing this.

Iroh: *learns to firebend without hatred and aggression after being found worthy by the dragons*

Also Iroh: *Commits imperialistic violence against the Earth Kingdom for decades culminating in a 600 day siege of Ba Sing Se*

Truly an example of how firebending can be used without hatred or aggression and how he proves himself worthy to the dragons.

#iroh#atla#legacy of the fire nation#avatar legends rpg#iroh meta#iroh critical#iroh is not a flawless saint#atla critical#legacy of the fire nation critical#avatar legends rpg critical

314 notes

·

View notes

Note

I've actually seen people say that the line in TSR sounds like Zuko isn't about defending Katara but that Zuko thinks Aang's beliefs are silly, and he doesn't think it's not part of the "real world" or something. How would you explain that part? I hope this doesn't come off as aggressive, I just want to know your thoughts.

i think what a lot of people tend to forget about aang - mostly because the show loves to paint him as Eternally Right and Wise most of the time - is that we cannot take what he says about air nomad culture as the Word of God. this is not to say that his beliefs are wrong or immoral, but that his interpretation and understanding of those beliefs will be naturally influenced by the fact that he's only twelve years old.

we see multiple times in atla that aang's perspective of air nomad culture is contradicted by that of other air nomads. gyatso is found surrounded by dozens of fire nation corpses that he undoubtedly killed. yangchen tells aang directly that his moral and spiritual duty is to kill ozai, regardless of his own feelings on the matter. clearly, then, neither of these two practiced absolute pacifism and both of them have years of experience and learning on aang. that is why simply reading, or studying, or parroting what other, more learned people have told you does not make you an expert on your culture - because the final component of genuine understanding comes from practice, from living and experiencing and putting your beliefs to the test, tempering them in the fire, questioning those that don't hold up and renewing your faith in those that do.

the problem arises from the fact that aang never does this, because he simply does not yet have the life experience to critically think about what he was taught! and that's fine, but it's also why it grinds my gears when people act as though aang was some kind of moral authority in the southern raiders, because he is very much still a child with a child's understanding of his culture.

that is what zuko means when he says that this isn't air temple preschool, but the real world (not a nice or polite remark, for sure, but also not without an element of truth to it). zuko is not calling aang's beliefs "silly", but he is calling out the fact that aang is not in a position to lecture others using beliefs that he himself does not - in fact, cannot - yet fully comprehend since he does not have the time and learned experience necessary for said comprehension.

and there was a much better narrative there about how aang clings to what he was told about his culture because it's all he has left of it, and how truly honoring his people's legacy means critically engaging with his cultural beliefs rather than enshrining them, allowing him to become a fully realized air nomad instead of remaining forever crippled by his grief - but sadly that's not the narrative we got, since aang had to be Unquestionably Right, and that's why we're still stuck dealing with discourse like this.

#atla critical#aang critical#it's not even actually critical of aang but we know how certain aang stans are so#anon asks

218 notes

·

View notes

Text

While enslaved people were mostly overseas, in colonies, out of sight, slavery funded British wealth and institutions from the Bank of England to the Royal Mail. The extent to which modern Britain was shaped by the profits of the transatlantic slave economy was made even clearer with the launch in 2013 of the Legacies of British Slave-ownership project at University College London. It digitised the records of tens of thousands of people who claimed compensation from the government when colonial slavery was abolished in 1833, making it far easier to see how the wealth created by slavery spread throughout Britain after abolition. “Slave-ownership,” the researchers concluded, “permeated the British elites of the early 19th century and helped form the elites of the 20th century.” (Among others, it showed that David Cameron’s ancestors, and the founders of the Greene King pub chain, had enslaved people.)

But as Bell-Romero would write in his report on Caius, “the legacies of enslavement encompassed far more than the ownership of plantations and investments in the slave trade”. Scholars undertaking this kind of archival research typically look at the myriad ways in which individuals linked to an institution might have profited from slavery – ranging from direct involvement in the trade of enslaved people or the goods they produced, to one-step-removed financial interests such as holding shares in slave-trading entities such as the South Sea or East India Companies.

Bronwen Everill, an expert in the history of slavery and a fellow at Caius, points out “how widespread and mundane all of this was”. Mapping these connections, she says, simply “makes it much harder to hold the belief that Britain suddenly rose to power through its innate qualities; actually, this great wealth is linked to a very specific moment of wealth creation through the dramatic exploitation of African labour.”

This academic interest in forensically quantifying British institutions’ involvement in slavery has been steadily growing for several decades. But in recent years, this has been accompanied by calls for Britain to re-evaluate its imperial history, starting with the Rhodes Must Fall campaign in 2015. The Black Lives Matter protests of 2020 turbo-charged the debate, and in response, more institutions in the UK commissioned research on their historic links to slavery – including the Bank of England, Lloyd’s, the National Trust, the Joseph Rowntree Foundation and the Guardian.

But as public interest in exploring and quantifying Britain’s historic links to slavery exploded in 2020, so too did a conservative backlash against “wokery”. Critics argue that the whole enterprise of examining historic links to slavery is an exercise in denigrating Britain and seeking out evidence for a foregone conclusion. Debate quickly ceases to be about the research itself – and becomes a proxy for questions of national pride. “What seems to make people really angry is the suggestion of change [in response to this sort of research], or the removal of specific things – statues, names – which is taken as a suggestion that people today should be guilty,” said Natalie Zacek, an academic at the University of Manchester who is writing a book on English universities and slavery. “I’ve never quite gotten to the bottom of that – no one is saying you, today, are a terrible person because you’re white. We’re simply saying there is another story here.”

323 notes

·

View notes

Text

I don't think Iroh was wrong for not trying to make Zuko feel sympathy for Azula during the show since there was no way of reaching her while Ozai was still in power and any hesitation on his or Zuko's part would lead to them being in chains or dead.

But no, Iroh doesn't have a model for treating two kids fairly, and to be quite honest, there is a strong argument that Iroh never cared for Azula since he viewed her an obstacle to Zuko to getting Ozai's love, and then, after his redemption arc, to becoming the savior of the Fire Nation.

i know i literally just wrote a post about it, but it’s just earth-shattering to me that… ok, so even with all the kindness and love he offers zuko, iroh still regards parenting two or more children still as a matter of showing favouritism, right? it wasn’t as if he tried to even be polite or sympathetic towards azula; he encouraged zuko to see her as an obstacle to overcome, he validated those feelings of resentment and jealousy without also ever trying to encourage him to look at her sympathetically, without an “I understand, but remember your sister has had a difficult journey too,” without encouraging the sympathy & compassion required to navigate sibling conflict, and ultimately fuelled that competitive sibling dynamic for the worse.

and for a while i thought - like a lot of people - that was weird. probably motivated by misogyny on some level, but I didn’t really get it for the longest time, and just thought it was a weird oversight of the writers for the sake of “haha this 14 year old girl most terrifying thing ever” comedy - which don’t get me wrong, is funny, but they leaned into it a little too much (at the expense of characterful writing).

but actually all iroh is doing is mirroring literally every parental relationship in the fire nation royal family. he’s showing blatant favouritism to one child and disregarding the other. just like ozai did to his children, just like it’s implied azulon did to his children, (and I would not be surprised if sozin was the same in this regard either). there’s a key difference in that he shows genuine love, support, & care for zuko, but ultimately iroh still wants to give his favoured child everything. iroh still wants zuko to seize the crown, and in order to do that he needs to be able to take down azula without hesitation. there’s no space for mediation there. it’s one or the other, in his mind.

like, it just hit me, that i honestly don’t think iroh has a model for treating two kids fairly, and it might literally just be outside of his understanding. I don’t know if he can conceive of a relationship in the royal family not being marred by competitiveness and toxic rivalry, with one having the crown and the other scrambling for scraps. it’s always been like that. like he literally can’t imagine it.

and yes that’s a deep failing on his part, his inability to even show a scrap of sympathy for azula is really damning, but oh god it just points to how deeply fucked up the fire nation royal family is. nobody has any clue what a healthy relationship between two (or more) siblings looks like.

#iroh#fire nation royal family#legacy of the fire nation#iroh meta#iroh critical#fire nation royal family meta#iroh is not a flawless saint

835 notes

·

View notes

Note

hello! I have already seen the opinion several times that everlark and zutara are very similar ships. as a big everlark shipper, I feel that there is something wrong with such an opinion. what can you say about it?

everlark and zutara are similar ships??? how???

zutara has always been given grace from the fandom for as long as i can remember, has always been the fandom preference, while back in the 2010s people despised everlark and wanted katniss to get with gale simply because they found liam hemsworth so much hotter. i directly recall all of my friends being team gale and making fun of me for being team peeta while the movies were coming out. i’m glad that the fandom seems to have done a 180 since the ending of the books and movies; but i also see people taking part in revisionist history by saying that everlark was always the fandom’s preferred choice & i just want to remind y’all that no!!! early everlark stans were in the trenches!

not to mention the criticisms towards everlark and kataang are very similar? i.e., it was forced, katara/katniss didn’t actually love them, aang/peeta coerced their partners into a relationship, aang/peeta isn’t masculine enough for katara/katniss, it was trauma bonding, etc etc. sometimes when i read anti everlark opinions, i get a serious case of deja vu because i’ve heard those exact arguments being used for kataang.

i’ll have to reread the hunger games trilogy for an accurate comparison on the similarities and differences between everlark and the two atla ships. i can, however, offer my two cents based on the following quote:

“That what I need to survive is not Gale's fire, kindled with rage and hatred. I have plenty of fire myself. What I need is the dandelion in the spring. The bright yellow that means rebirth instead of destruction. The promise that life can go on, no matter how bad our losses. That it can be good again. And only Peeta can give me that.”

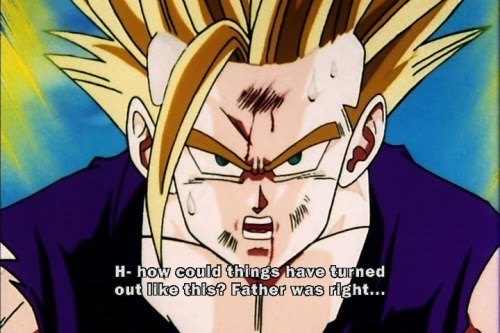

and based on what iroh has said about zuko and katara’s dynamic in the legacy of the fire nation, which i think summarizes it perfectly:

“she was certainly the whetstone against which you honed and sharpened your fury, at least for some time.”

“you both shared tremendous passion, but also emotional pains that fueled the fire in your bellies.”

“but her instincts and aang’s advice served her well, as she discovered that vengeance was not the answer.”

this post also provides a great visual summary into how katniss’ monologue applies to katara and aang (rather than katara and zuko):

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

Days of The Jackal: how Andrew Wylie turned serious literature into big business

Andrew Wylie is agent to an extraordinary number of the planet’s biggest authors. His knack for making highbrow writers very rich helped to define a literary era – but is his reign now coming to an end?

Andrew Wylie, the world’s most renowned – and for a long time its most reviled – literary agent, is 76 years old. Over the past four decades, he has reshaped the business of publishing in profound and, some say, insalubrious ways. He has been a champion of highbrow books and unabashed commerce, making many great writers famous and many famous writers rich. In the process, he has helped to define the global literary canon. His critics argue that he has also hastened the demise of the literary culture he claims to defend. Wylie is largely untroubled by such criticisms. What preoccupies him, instead, are the deals to be made in China.

Wylie’s fervour for China began in 2008, when a bidding war broke out among Chinese publishers for the collected works of Jorge Luis Borges. Wylie, who represents the Argentine master’s estate, received a telephone call from a colleague informing him that the price had climbed above $100,000, a hitherto inconceivable sum for a foreign literary work in China. Not content to just sit back and watch the price tick up, Wylie decided he would try to dictate the value of other foreign works in the Chinese market. “I thought, ‘We need to roll out the tanks,’” Wylie gleefully recounted in his New York offices earlier this year. “We need a Tiananmen Square!”

Literary agents are the matchmakers and middlemen of the book industry, pairing writers with publishers and negotiating the contracts for books, from which they take an industry-standard 15%. In this capacity, Wylie and his firm, The Wylie Agency, operate on behalf of an astonishing number of the world’s most revered writers, as well as the estates of many late authors who, like Borges, Chinua Achebe and Italo Calvino, have become required reading almost everywhere. The agency’s list of more than 1,300 clients includes Saul Bellow, Joseph Brodsky, Albert Camus, Bob Dylan, Louise Glück, Yasunari Kawabata, Czesław Miłosz, VS Naipaul, Kenzaburō Ōe, Orhan Pamuk, José Saramago and Mo Yan – and those are just the ones who have won the Nobel prize. It also includes the Royal Shakespeare Company and contemporary luminaries such as Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Karl Ove Knausgård, Rachel Cusk, Deborah Levy and Sally Rooney. “When we walk into the room, Borges walks in, and Calvino walks in, and Shakespeare walks in, and it’s intimidating,” Wylie said.

When the Borges auction took off in 2008, Wylie began plotting. “How do we establish authority in China?” he asked himself. Authority is one of Wylie’s watchwords; it signifies the degree to which his agency can set the terms of book deals for the maximum benefit of its clients. To establish such authority, it is critical, in Wylie’s view, to represent authors who command a position of cultural eminence in any given market – Camus in France, Saramago in Portugal and Brazil, Roberto Bolaño in Latin America. “I always look for a calling card,” Wylie said. “If you want to deal in Russia, for example, you want – dot dot dot – Nabokov.”

Who better to help him take over China, Wylie thought, than Henry Kissinger? In the 1970s, as US national security adviser and secretary of state under President Nixon, Kissinger had presided over a historic rapprochement between the US and China. Since then, he had been an important interlocutor between China and the west. Kissinger was not a Wylie client, but that was an easy problem to solve. When Wylie Googled Kissinger’s name in 2008, he was confronted with books attacking his humanitarian record. “Kissinger was depicted as a war criminal who enjoyed killing babies – basically a monster,” Wylie said. “So I went to him and said: ‘Henry, this is not good legacy management.’” Wylie told Kissinger to fire his agent. Then, he added, “You need to get all three volumes of your memoirs back in print, and write a new book, a strong book.” Kissinger quickly became a client of The Wylie Agency.

The new book would be called On China. Wylie’s plan was to sell it to the Chinese market first, an unprecedented tactic for a book by a famous American author. In 2009, a Chinese publisher bought the rights to it for more than $1m, Wylie claimed (although he later said he was not able to confirm this figure). Authority duly established, his agency has gone on to achieve seven-figure deals in China for the works of authors as various as Milan Kundera and Philip K Dick. “That is how you take Tiananmen Square,” Wylie crowed, recalling his success. “You put Henry in the first tank, and you fill it with gas!”

The Kissinger operation was vintage Wylie: tempting an author away from a competitor and then leveraging that client’s reputation to mutually beneficial ends. “He’s playing a multiyear game in which he is constantly trying to consolidate the board,” Scott Moyers, the publisher of Penguin Press and a former director of the Wylie Agency. In the 1980s and 90s, so the legend goes, Wylie used his commercial cunning to disrupt the chummy norms that reigned in the publishing industry, replacing them with what one tabloid newspaper referred to as a “greed storm”. When he met Wylie in the late 1980s, the author Hanif Kureishi later wrote, he was reminded of “the bullying, loud-mouthed suburban wide-boys I’d grown up with, selling socks and watches from suitcases on a pub floor”. Since the mid-90s, Wylie has been known as The Jackal, and many other agents and small publishers still see him as a predator who seizes literary talents nurtured by others. His agency’s approach is “very adversarial”, Valerie Merians, the cofounder of the independent publisher Melville House, said. The head of rights at a London literary agency put it more bluntly: “He uses Colonel Kurtz methods.”

But there is more to Wylie’s success and his character than mere rapacity. Better than anyone else, Wylie and his agency have figured out how to globalise and monetise literary prestige. “I took him on after my six previous agents did not provide, out of idleness, what I required,” Borges’s widow, María Kodama, once said of Wylie. The works of Borges and other classics can be found throughout Latin America and Spain, in part because Wylie makes sure that publishers “commit to keeping them alive everywhere,” Cristóbal Pera, a veteran Spanish-language publisher and a former director at The Wylie Agency, said. At the same time, Wylie’s international representation of authors like Philip Roth and John Updike has succeeded in “establishing American literature as world literature”, the Temple University scholar Laura McGrath has written.

Wylie’s literary tastes and international reach helped to create what was for several decades the dominant vision of literary celebrity. In the era in which writers such as Roth and Martin Amis had an almost equal place in the tabloids and in the New York Review of Books, when they were famous in Milan as well as Manhattan, and might plausibly afford to keep apartments in both, when they were public intellectuals living semi-public lives, Wylie was the most audacious broker of literary talent in the world, a man who seemed equally intimate with high culture and high finance.

Today, that era of priapic literary celebrity has faded, and some believe that Wylie’s stock has gone down with it. “I think the Wylie moment has passed,” Andrew Franklin, the former managing director and co-founder of Profile Books, said. “When he dies, his agency will fall apart.” A crop of younger agents and large talent agencies have attempted to adapt many of Wylie’s business strategies to a new reality, in which literary culture is highly fragmented and clients are less likely to be novelists or historians than “multichannel artists” with books, podcasts and Netflix deals.

Wylie thinks that’s bunk. Even if the era of high literary fame is dead, he believes great literature continues to represent the best long-term investment. “Shakespeare is more interesting and more valuable than Microsoft and Walt Disney combined,” repeating an argument he has been making in the media for more than 20 years. All the Bard of Avon lacked was a good trademark lawyer, a long-term estate management plan and, of course, the right agent.

If Wylie is the world’s most mythologised literary agent, it is partly because the caricature of him as a plunderer of literary talent and pillager of other agencies has been so irresistible to the media, and at times to Wylie himself. “I think Andrew quite likes the whole Jackal thing, because it makes him seem like a kind of hard man,” Salman Rushdie, one of Wylie’s longest-standing clients and closest friends. Wylie is an ardent burnisher of his own legend, which is not to say that he traffics in falsehoods. He has led a remarkable life, and even when recounting facts that are grubby or mundane, he instinctively elevates them into something more fabulous. A dealmaker, after all, trades primarily in reputation.

Wylie’s success is founded, in part, on his gift for proximity to the great and the good. As a young man, he once spent a week in the Pocono mountains interviewing Muhammad Ali for a magazine, and singing him Homeric verses in the original Greek. He visited Ezra Pound in Venice and sang him Homer, too. In New York, he spent a lot of time at Studio 54 and the Factory studying the way Andy Warhol fashioned his public persona. He says Lou Reed introduced him to amphetamines in the 1970s and that he gave the band Television its name. The photographer and film-maker Larry Clark was best man at his second wedding. At the height of the fatwa against Rushdie, when Wylie wasn’t meeting with David Rockefeller to strategize a lobbying campaign to lift the supreme leader’s death warrant, or trying to self-publish a paperback edition of The Satanic Verses, he was sitting on the floor of a New York hotel room with mattresses covering the windows for security, meditating with Rushdie and Allen Ginsberg. At Wylie’s homes in New York and the Hamptons in the 90s, party guests might include Rushdie, Amis, Ian McEwan, Christopher Hitchens and Susan Sontag, or Rushdie, Sontag, Norman Mailer, Paul Auster, Siri Hustvedt, Peter Carey, Annie Leibovitz and Don DeLillo. (There was once a minor crisis when Wylie forgot to invite Edward Said.) Wylie was one of the first people to whom Al Gore showed the PowerPoint presentation that later became An Inconvenient Truth.

In his younger days, Wylie cultivated his reputation through decadence and outrageousness. At a publishing party in the 80s, Tatler reported that he invited a young novelist to “piss with me on New York”, and then proceeded to urinate out the window on to commuters at Grand Central station. (When asked to confirm or deny this, he said, “pass”.) During a hard-drinking evening with Kureishi around the same time, he spat on a copy of Saul Bellow’s More Die of Heartbreak, called it “utter drivel”, then stubbed his filter less cigarette out on it. (Wylie denies this happened, but Kureishi wrote about it in his diary at the time and later confirmed the story to his biographer Ruvani Ranasinha.) Bellow became a Wylie client in 1996, Kureishi in 2016.

The centre of the Wylie myth, however, has long been his ferocious pursuit of business. The author Charles Duhigg, a Wylie client, has proudly said that, in negotiations with publishers, his agent is “a man that can squeeze blood from a rock”. Wylie takes pleasure in conflict, and can be joyfully bellicose. Of a former client turned adversary, of which there have been a few, he will merrily remark, “I will refrain from saying ‘Fuck you’ to Tibor, because he’s already fucked.” He is as bald, cigar-puffing and self-assured as a Churchill. At The Wylie Agency, which he launched in 1980, “the keynote is aggression”, one of his former employees mentioned. That is not just the view of his detractors; Rushdie has described Wylie with affection as an “aggressive, bullet-headed American”.

The Wylie Agency hunts for undervalued literary talent the way a private equity firm might trawl for underperforming companies that it can turn into major profit centres after firing the current management. When he started out in the early 80s, Wylie saw more clearly than anyone else that literary reputations are commercial assets, and that if you control those assets, you ought to wring as much value from them as possible. Never mind if you have to use tactics that others consider unethical or underhanded. Scott Moyers summed it up this way: “When he came into publishing he said, ‘Fuck this. Who gains by this? What am I legally allowed to do? Let’s start with that as a basis, and then I’m gonna get to work.’”

Wylie’s New York offices are on the 22nd floor of a building in Midtown Manhattan. In the small reception area hangs an enormous framed picture of the first-edition cover of The Information, Martin Amis’s eighth novel, published in 1995. This is the book that caused Wylie to become widely known as The Jackal, after he ravished Amis away from the agent Pat Kavanagh, the godmother of Amis’s first child, with a pledge to sell the novel for £500,000. Like Wylie himself, the giant poster is calculated to seem at once high-minded, tongue-in-cheek and larger than life. It is Wylie revelling in his own myth.

“I think everyone got everything right,” he said slyly, when asked if journalists had, over the years, misunderstood him. It was a quintessential Wylie move: never to seem out of control of his own persona, always on guard against the impression that someone has perceived something about him that he has not intended. But it became clear he most assiduously fosters the impression that he values great literature. That is, he appreciates it for its own sake, and he also fights to ensure it is assigned what he believes is its proper price.

Wylie was eager to present his viewpoint as being at odds with the rest of the publishing industry, which he portrayed as offering up the fast food of the mind. The attitude of most publishers and agents, he said, is roughly: “Fuck ’em, we’ll feed them McDonald’s. It may kill them, but they’ll buy it.” Bestsellers are the greasy burgers of this metaphor. If you read the bestseller list, Wylie went on, “You will end up fat and stupid and nationalistic.” The sentiment is genuine, but it leaves out the fact, as Wylie’s critics delight in pointing out, that he has represented such questionable literary lights as his landscape architect and Madonna.

It was time for lunch. Wylie’s favourite spot is the chain restaurant Joe and the Juice, and he relished his own description of the cardboard bread and desiccated tomatoes in its turkey sandwich. “You feel right next door to extreme poverty when you eat at Joe and the Juice, which is a comfortable place to be,” he said. First, though, he wanted to smoke, so he strolled through Midtown as he puffed away on one of the Cuban cigars he buys from a shop on St James’s Street in London’s Piccadilly. By habit or design, his walk brought him to the sleek glass exterior of the Penguin Random House headquarters, where he stood for a moment in front of a digital display advertising a novel called Loathe to Love You, the latest instalment of a bestselling series of romances about Silicon Valley types. Wylie was exuberantly disgusted. “I mean, that speaks for itself,” he exclaimed.

he continued walking. Colleen Hoover, a Simon & Schuster romance author who had five novels on the New York Times bestseller list that week, was at that moment the greasiest of all the greasy burgers in his mind. “Put down your Colleen Hoover and begin to live!” he exhorted the culture at large. “Throw away the Big Mac and eat some string beans!” (Stridency and snobbery are a favourite pairing in his humour.) He soon arrived at Joe and the Juice, but the wait for a sandwich was more than a quarter of an hour, so he moved on to a local diner. For lunch, Wylie ordered a cheeseburger, rare.

Wylie often claims that he does not have a personality of his own, and is constantly in search of one. “I have this sort of hollow core,” he likes to say. That seems dissembling, perhaps self-protective, but more than one observer has noted that Wylie perennially reinvents himself in ways that reflect the spirit of the age: there was the investment banker of books in the 80s, the force for literary globalisation in the 90s, a supporter of American exceptionalism in the 00s and the critic of what he sees as the twin crises of national and literary decline today. (“I support, broadly speaking, the endeavour of the United States, which is very troubled at the moment,” he said at one point.) He is a man of multiple incarnations, from which a coherence nonetheless blooms.

Wylie grew up in a moneyed and highly literate Boston family; when Rushdie visited his agent’s childhood home in 1993, he found the initials AW still carved into an oak bookcase in the library wing. But Wylie spent a good portion of his teens and 20s in rebellion against his parents’ social world. He was kicked out of St Paul’s, the ultra-elite New England boarding school where his father went, for peddling booze to fellow students. Soon after, at age 17 or 18, he punched a policeman in the face. Given a choice between reform school and a psychiatric hospital, he chose the latter. He spent about nine months at the Payne Whitney clinic on Manhattan’s Upper East Side, not far from where he now lives, pacing the courtyard and memorising Finnegans Wake. “Everyone I admired had been crazy,” he said, including Ezra Pound and Robert Lowell. “I’m not, but I can fool everyone that I am.” André Bishop, who was close to Wylie at St Paul’s and later at Harvard, used to visit Wylie in hospital on the weekends. “I don’t know if I would call him crazy – I think he was disturbed,” Bishop said. “But it was real. I don’t think he was putting on an act.” (Bishop is now the head of Lincoln Center Theater in New York and one of Wylie’s clients.)

Not long after Wylie was discharged from psychiatric hospital, he arrived at Harvard, also his father’s alma mater. “Nervous, a bit wild, gentle and intelligent,” is how the modernist poet Basil Bunting described him at 19 years old, in 1967. At Harvard and in the first few years after graduation, poetry was the centre of his life. “I’ve been having a look at the verse Eliot wrote at Harvard, and find that yours is more accomplished, despite the echoes,” Bunting wrote to him. In 1969, Wylie married his college girlfriend, Christina, and the following year, she gave birth to their son, Nikolas. The couple wrote poetry, and Wylie spent his days working in a Maoist bookshop near Harvard Square.

In 1971, Wylie left his young wife and child “with the car and the bank account” and moved to New York City. (He and Christina were “moderately unhappy people” and they divorced in about 1974; he remarried in 1980, and has two more children.) In New York, he drove a taxi and wore his beard and thinning hair biblically dishevelled, as if he were wandering Mount Sinai instead of Lower Manhattan. He rented a storefront in Greenwich Village from which he attempted to sell his college library, including editions of Heraclitus in multiple European languages. Bob Dylan and John Cage were occasional customers, but “business was not brisk”, Wylie has said. Bunting wrote with condolences: “It is equally difficult to read the books that sell or sell the books you can read.”

Wylie, his family money ultimately backstopping his risks, was undeterred. He cofounded a small press and published the first book of poetry by a young musician named Patti Smith. He began a freelance gig doing celebrity interviews of figures like Warhol and Salvador Dalí for various books and magazines. He brooded, some of his acquaintances thought, on a certain kind of fame. The punk pioneer Richard Hell, who moved in similar circles, later wrote that “Andrew’s main model was Andy Warhol, because of Warhol’s combination of artistic talent with overriding worldly ambition”.

Then, sometime in the mid 1970s, Wylie began a three-year, amphetamine-fuelled “hiatus” from life, during which he slept about six hours a week, he said. “If you grow up with money, you either spend it over the course of your life, and you’re done, or you get rid of it and start from scratch,” Wylie said. He said he injected most of his inheritance into his arm. Eventually, “a lot of people I was doing business with were apprehended and sent away, so the supply of drugs went to zero,” he added. When he recovered from a terrible period of withdrawal, he decided it was time to get on with the business of living.

The story that Wylie likes to relate of how he became a literary agent usually runs like this. It was 1979. He was off amphetamines and needed a job. Following in the footsteps of his late father, a director at the publishing house Houghton Mifflin, he applied for publishing roles. When he was asked in an interview what he was reading, he said Thucydides, and the interviewer told him he should read the bestsellers instead. “So I looked at the bestseller list and I thought, ‘Well, if that’s what you have to do to be in this business, then really and truly, fuck it, I’ll be a banker,’” he said in a speech in 2014. But banking appealed to him about as much as the bestseller list did. Then a friend at a publishing house suggested he look into becoming an agent.

As an agent, Wylie could attempt to thread the needle between commerce and quality. Books are a high-risk, low-margin business; Wylie has compared its profits unfavourably to those of shoe-shining. But the best literary works can remain in print for a long time, generating small but steady streams of income. Wylie began by renting a desk in the hallway of another agency, where he learned “how not to do things”. In his telling, it was just Harvard men getting drunk with Harvard men, selling unread manuscripts by Harvard men to fellow Harvard men. Wylie saw an opportunity: by treating books with the utmost seriousness, and by treating business as business, he could carve out a profitable niche for himself. In 1980, Wylie borrowed $10,000 from his mother, and The Wylie Agency was born. “We would corner the market on quality, and we would drive up the price,” Wylie later said of his business philosophy, to the sociologist JB Thompson.

The best writers needed serious wooing, Wylie understood, so he became an unparalleled practitioner of the grand gesture. He would call a writer and ask to meet next time he was in town. Then he would get the next flight to town, where he would recite to the writer swathes of their own prose, or verses of Homer. Wylie flew to Washington DC to win over the radical American journalist IF Stone. He flew to France to sign the deposed Iranian president Abolhassan Banisadr, whose book on Iran he miserably failed to sell. He flew to London to woo Rushdie, who demurred, so he flew to Karachi to sign Benazir Bhutto, who didn’t. Then he flew back to London for another go at Rushdie, who, impressed by the Bhutto manoeuvre, became receptive to Wylie’s advances. Surprise next-day arrival, the deployment of one client to attract another and the chanting of dactylic hexameters became canonical elements of the Wylie mating ritual.

Charm offensive complete, Wylie would talk money. “The most important thing … is to get paid,” Wylie told Stone, his first client, according to the biographer DD Guttenplan, who is also a client of The Wylie Agency. The bigger the advance, the better, Wylie went on: the more a publisher spends on buying a book, the more they will spend on selling it. Thompson later dubbed this “Wylie’s iron law”. The 80s were a good time for getting paid. Thanks to a historic rise in the number of readers after the baby boom, an explosion in book sales and the conglomeration of booksellers and publishing houses, publishers had more money, enabling agents like Wylie to demand higher and higher advances for their clients. Once one literary writer got a six-figure book deal, others expected to get six figures, too.

Within a few years of opening his agency, Wylie had an exquisitely curated list of a dozen or so writers. He devoted “seasons” to learning about one or two fields, from politics to art and theatre, and then courted the most significant names in each. He signed up Ginsberg and William Burroughs, David Mamet and Julian Schnabel. He also added the New Yorker writers and fiction editors Veronica Geng and William Maxwell, important nodes in the discovery network of new talent. In the mid-80s, he partnered with an agency in the UK and started systematically pursuing writers whom he deemed to be “underrepresented” by other agents. By the time he convinced Bruce Chatwin, Ben Okri, Caryl Phillips and Rushdie to leave their agent in 1988, Wylie was quickly becoming one of the most important conduits of money and influence in literary culture. As Ginsberg told Vanity Fair, Wylie was “assuming the normal powers of his family station after a long, experimental education which had ranged from high-class to the gutter”.

Every April, Wylie flies to London for the London Book Fair. For three days, he and his colleagues meet foreign publishers, pitching them books, negotiating deals and gathering intelligence on the state of their businesses. The Wylie Agency has offices in a Georgian townhouse on London’s Bedford Square, but Wylie often takes his meetings in the courtyard of the American Bar at the Stafford hotel, off St James’s Street, where cigar-smoking is encouraged. He was there on a Sunday morning before the fair. It was the start of a 12-day trip that would also take him to the south of France to meet the Camus family and to Lisbon to meet the Saramagos. Then he would fly back to New York, where he was looking forward to celebrating Kissinger’s 100th birthday. In London he would mostly be doing “just the tedious usual shit”, he said – pitching books to publishers and negotiating deals.

That Wylie is an agent who can demand six or seven figures and be taken seriously comes, in part, from close study and good information. “We are intensely systems-driven,” he said. “If the computer tells you that Saramago’s licence in Hungary is expiring in three months, then you look at the entire Hungarian market.” Teams of two or three Wylie agents regularly fly around the world to visit publishing houses, speak with editors and take photographs of their buildings. They generate a report on each house that is shared throughout the agency. “It was badly heated, staff seemed depressed but the publisher herself was quite vibrant,” Wylie said, as if he were reading one of the dossiers. Wylie also takes advice about certain markets, like Russia, from members of the prestigious Council on Foreign Relations, of which he is also a member.

If that all sounds a bit like intelligence-gathering, it is. “I’m very interested in the work the CIA does and how they do it,” Wylie said. “I think there’s a lot to learn from the agency about the way things work politically, and the way strategic calculations are made.” He has had a number of clients who are working or have worked at the CIA, including the former director Michael Hayden and the current director, Bill Burns. “We have access to projects that come out of the CIA as a first port of call,” Wylie said. He added that it was out of a CIA operation that he represented King Abdullah II of Jordan’s 2011 book, The Last Best Chance. When asked whether he could say more, he thought for a moment, then replied, “I probably can’t.”

Today, The Wylie Agency makes about half of its money in North America, and the other half from the rest of the world. “Part of our practice is to always be looking at how international publishing markets are shifting,” Wylie said. Romania and Croatia were up and coming, he added, as was the Arabic-language market. Korea was “very dynamic”. China, of course, was key.

Other people in the publishing industry, particularly smaller agents and publishers, think that Wylie’s highly efficient operation has harmed the culture and spirit of the book world, turning the genteel pursuit of publishing into a race to the bottom line. Andrew Franklin, the former Profile Books director, said that Wylie had built a factory that simply churns out deals. “It’s like a really efficient law firm,” Franklin said. (His colleague, Rebecca Gray, who has since taken over as managing director of Profile, remarked, “I think that’s the rudest thing that a publisher can say.”) A number of people in the industry suggested that the more talent Wylie has moved from small, independent presses to conglomerate imprints with large balance sheets, the more he has eroded the broader ecosystem of literary publishing. Wylie replied that this sounded like “the logic of resentment coming from small publishers who were no longer allowed the luxury of underpaying and underpublishing writers of consequence”.

Yet the issue is not just about money. Beyond handling the business side of things, agents are often a writer’s first reader, most attentive editor, therapist and dear friend; some people in the industry see the relationship as an almost sacred bond. A few months before the agent Deborah Rogers died in 2014, Kazuo Ishiguro remarked that “she taught me to be a writer”. Like Kureishi and McEwan, Ishiguro had remained her devoted client even while Wylie was seducing other clients away from her.

But most writers need to get paid, too. Kureishi, for one, long had qualms about the advances his books were reaping. When he joined The Wylie Agency two years after Rogers’ death, he was suddenly able to access a “different level of money and efficiency”, he told his biographer. Likewise, Barbara Epler, the president of the small but influential publishing house New Directions, mentioned a conversation she had in 1998 with the German writer WG Sebald when he left her for another imprint. “He said, ‘Barbara, you know you’ll always be my publisher. But the new novel – Wylie is getting me a half a million dollars for it!’”

Alongside the critique that Wylie has coarsened the industry, a number of people suggested that he has a tendency to aggrandise his accomplishments. Several publishers who work in China said that the Chinese may flatter Wylie that he’s a big deal, but that other agencies, like Andrew Nurnberg Associates, are much more influential there. Wylie made an important contribution to the career of a well-known American historian by suggesting the historian write for the New Yorker; the historian said that writing for the magazine had been a lifelong dream, and Wylie had nothing to do with it.

“There is Trump, Boris – and then there is Andrew Wylie,” Caroline Michel, the CEO of Peters Fraser and Dunlop, a rival agency, said, when she was asked about Wylie, who had recently taken over one of her firm’s clients, the estate of the Belgian writer Georges Simenon. Wylie claimed that, among other things, Peters Fraser and Dunlop had missed major commercial opportunities in the US and China. Michel rejected that account. When her agency acquired the Simenon estate 10 years ago, she said, fewer than a dozen of his 400 books were in print in English. Within seven years, she continued, they had all of the 100 or so Maigret books in print in English, and three years later her agency sold its portion of the rights for 10 times what it had acquired them for.

“What we did with those books from nothing could be considered one of the great reinventions” of a literary estate, Michel said. “But Andrew can blow smoke up his own ass if he wants to.”

Simenon is in many ways a classic Wylie target: the estate of an internationally popular author with a highly exploitable backlist who nevertheless has the requisite literary value. (“With Ian Fleming, it’s all surface,” Wylie said. “Simenon has the psychology.”) But it is only the most recent of Wylie’s campaigns of avid expansion. In 1997, the renowned agent Harriet Wasserman could already gripe that Wylie had annexed “more literary territory than Alexander the Great”. She also said she would rather clean the men’s toilet bowl in a New York subway station with her tongue than meet him: he had recently enticed Saul Bellow away from her. “There were a lot of agents who were tough, and there were some who were literate,” said Andrew Solomon, who became a Wylie client in 1998, when he was 24 years old. “But you tended to have to choose.”

Wylie was always thinking globally. In the 2000s and 2010s, he made two serious attempts to enter the Spanish language market directly by opening up an office in Madrid and buying a renowned agency in Barcelona (both failed). He attempted to sign up many of the most important American historians (a success) and to sell their books abroad (a failure). He attempted to force the major publishing houses to give authors a greater share of royalties for digital rights by setting up his own ebook company (also, in most respects, a failure). He began recruiting African writers who won the continent’s prestigious Caine prize (seven successes to date). He went after the estates of JG Ballard, Raymond Carver, Vladimir Nabokov, John Updike and Evelyn Waugh (success, success, success, success, success).

The pace of Wylie and his business in these years was not what many people expected of the publishing industry. “You were working on what sometimes felt like the floor of Wall Street,” said a former employee who worked at The Wylie Agency in the mid-00s. “An intellectual sweatshop for kids fresh out of the Ivy League,” is how another former employee described it. The workday was 10 hours long, and Wylie had an intense control over the minutiae of what was happening in the office. “You had to account for your whereabouts for anything longer than – excuse my crassness – taking a shit,” someone who worked in the New York office said. Wylie was generous and interesting, they claimed, but he didn’t stop some of his senior employees from being borderline abusive. A female employee from the mid-00s said that when a bunch of the assistants in the office saw The Devil Wears Prada, it struck a chord.

Despite that, “You felt you were in the midst of something important,” the person who worked in the New York office said. Staff might encounter Philip Roth wandering through the hallways; Al Gore or Lou Reed might be on the other end of the telephone. At Christmas parties, champagne flowed and Wylie would greedily dig the last of the caviar out of the tin with his finger. Hermès neckties were given to the gentlemen and cashmere scarves to the ladies. Even at other companies’ publishing parties, people were gossiping about The Wylie Agency: a now-legendary story went around New York that one evening Roth phoned the office. “Hello, The Wylie Agency, this is Andrew speaking,” an assistant at the other end of the line said. The excited caller, mistaking the assistant for the other Andrew, claimed – dubiously, to judge by recent reporting – that he had just gone to bed with the female lead in the movie being made of his novel The Human Stain, Nicole Kidman. The assistant, embarrassed, offered to put him through to Mr Wylie.

The Wylie Agency is still immensely influential, but the glamour of those previous decades is gone. For a long time, Wylie was known for his expensive neckties and Savile Row tailoring; Martin Amis proudly explained to his sons in the late 90s that his agent was called The Jackal “because of his claws and his jaws and the tail-slit in the back of his pinstripe suit”. But spending time with Wylie over several days in New York and London, he always wore blue jeans and a woollen shirt-jacket. Day after day, the uniform never changed; it suggested that his old suits were props in which he took no intrinsic interest, and that if he no longer had need of them, they could be cast away.

The week of the London Book Fair provided an inside view of the messy business and meagre economics of buying and selling highbrow books today. In a convention centre in west London, hundreds of agents were meeting with publishers from around the world. There were desks laid out in long rows, like an examination hall, but meetings were spilling over on to the floors, with several taking place against the wall by the entrance to the bathrooms. “Isn’t this horrible,” Wylie remarked. “It’s like a prison camp. Every time I come here I wonder what I’ve done to deserve this. I thought I was a good boy.” At another moment, he compared the convention centre to an elementary school in Lagos. “I’m going to get in trouble for saying that,” he said, despite the fact he had said it on the record many times before. “My Nigerian friends are going to find it condescending.” But he seemed to understand that its inappropriateness was the very thing that would get it repeated, and hopefully heard by the organisers of the book fair. It was tactical vulgarity. “Indiscretion is a weapon,” he mentioned once.

As he and his deputy, Sarah Chalfant, met publishers from around the world, Wylie often came across as more avuncular than avaricious, though he could be petulant at times. Wylie and Chalfant’s conversations with publishers ranged from the state of politics and the publishing industry to deeply personal stories about family travails. There were also, as always, writers’ egos to consider. At one point they discussed with an editor whether they should tell a famous English-language writer that no one could understand her when she spoke the language of her adopted country. They decided not to. (A writer’s “self-perception needs to be honoured”, Wylie had mentioned in another context.)