#late 19th – early 20th century women's fashion

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Women's Suffrage Movement

The movement for women's suffrage took many decades to obtain voting rights. Women fought for their rights via smart political strategy. Dynamic leadership attracted several generations of women – mothers, daughters, and grandmothers formed national organizations and made alliances that brought women into the political sphere. The fight intensified during World War I due to women's work outside the home to help the war effort. Women now saw themselves as fully deserving of the same rights as men.

A trio of outfits at the Daughters of the American Revolution Museum shows the evolution from the last gasp of Edwardian bulk to the short, simple dress of the Twenties. Left, a two-piece dress of about 1907 (Daughters of the American Revolution Museum). Center, a houndstooth suit of about 1914 (loan courtesy Shippensburg University Fashion Archives and Museum). Right, black and white day dress, 1925 (Daughters of the American Revolution Museum).

Exhibition vignette with the “Bear the Banner Proudly They Have Borne Before” banner, circa 1913-1920. National Woman’s Party. Belmont-Paul Women’s Equality National Monument, Washington, DC.

Purple, white, and gold were among the colors representing the movement. White dresses were worn by women as a representation of purity of thought and high-mindedness. Purple represented the vote and loyalty, constancy, and steadfastness. Gold stood for the torch that guides our way.

Ethel Wright (1866–1939) Christabel Pankhurst (British suffragette) • National Portrait Gallery, London

#fashion history#women's history#suffrage movement#women's voting rights#white dresses of the suffrage movement#colors of women's suffrage#daughters of the american revolution#late 19th – early 20th century women's fashion#the resplendent outfit art & fashion blog#ethel wright#woman artist#christabel pankhurst#suffrage fashion#historical photos

98 notes

·

View notes

Text

Word List: Fashion History

to try to include in your poem/story (pt. 1/3)

Adinkra - a flat, cotton textile that is stamped with symbols which create the meaning of the garment; produced by the Asante peoples in Ghana

Agal - a rope made from animal hair which wraps around a keffiya (square cloth) on the head and is worn typically by Bedouin men

Akwete - a decorative cloth with complex weave designs, creating intricate geometric patterns, made with many vibrant colors; it is usually made into wrappers for women to wear and it is made by the Igbo women of Nigeria

Aniline Dyes - synthetic, chemical dyes for garments first invented in the 19th century

Anorak - a jacket that typically has a hood, but not always, which was originally worn by the indigenous peoples of the Arctic designed to keep them warm and protected from harsh weather

Back Apron (Negbe) - an oval-shaped decorative pad worn by Mangbetu women over the buttocks in Central Africa

Backstrap Loom - a lightweight, mobile loom made of wood and a strap that is wrapped around the back; it only needed to be attached to a tree or a post for stability and to provide tension

Banyan - a loose-fitted informal robe or gown typically worn by men in the late 17th to the early 19th centuries

Barbette - a piece of linen which passes under the chin and is pinned at the sides, usually worn in conjunction with additional head coverings during the Middle Ages

Bark Cloth - fabric made out of bark from trees

Beadnet Dress - a decorative sheath dress made of beads worn in ancient Egypt

Bloomers - a bifurcated garment that were worn under dresses in the 19th century; they soon became a symbol of women’s rights because early activist Amelia Bloomer wore drawers long enough to stick out from under her dress

Bogolanfini - (bogolan- meaning cloth; fini- meaning mud) a cotton cloth made from strips of woven fabric, which are decorated with symbolic patterns using the mud-resist technique, sewn together at the selvage to create a fabric that is utilized during the main four stages of a West African Bamana woman’s life: puberty, marriage, motherhood, and death

Bombast/Bombasted - the padding used to structure clothing and create fashionable silhouettes in the 16th and 17th centuries

Boubou - an African robe made of one large rectangle of fabric with an opening in the center for the neck; when worn it drapes down over the shoulders and billows at the sleeves

Buff Coat - a leather version of the doublet that was often, but not exclusively, worn by people in the military in the 17th century

Bum Roll - a roll of padding tied around the hip line to hold a woman’s skirt out from the body in the late 16th and early 17th centuries

Burqa - an outer garment worn by Muslim women that covers the entire body, often with a cutout or mesh at the eyes

Busk - a flat length stay piece that was inserted into the front of a corset to keep it stiff from the 16th century to the early 20th century

Bustle - a pad or frame worn under a skirt puffing it out behind

Cage Crinoline - a hooped cage worn under petticoats in the 19th century to stiffen and extend the skirt

Caraco - 18th century women’s jacket, fitted around the torso and flared out after the waist

Carrick Coat - an overcoat with three to five cape collars popular in the 19th century and mostly worn for riding and travel–sometimes called a Garrick or coachman’s coat

Chantilly Lace - a kind of bobbin lace popularized in 18th century France; it is identifiable by its fine ground, outlined pattern, and abundant detail, and was generally made from black silk thread

Chaperon - a turban-like headdress worn during the Middle Ages in Western Europe

Chemisette - a piece of fabric worn under bodices in the 19th century to fill in low necklines for modesty and decoration

Chiton - an ancient Greek garment created from a single piece of cloth wrapped around the body and held together by pins at the shoulders

Chlamys - a rectangular cloak fastened at the neck or shoulder that wraps around the body like a cape

Chopines - high platform shoes worn mostly in Venice in the 16th & 17th centuries

Clavus/Clavi - decorative vertical stripes that ran over the shoulder on the front and back of a Late Roman or Byzantine tunic

Clocks/Clocking - decorative and strengthening embroidery on stockings in Europe and America during the 16th-19th centuries

Cochineal Dyes - come from the Cochineal beetle that is native to the Americas and is most commonly found on prickly pear cacti; when dried and crushed, it creates its famous red pigment that is used to dye textiles

Codpiece - originally created as the join between the two hoses at the groin, the codpiece eventually became an ornate piece of male dress in the 16th century

Cuirass Bodice - a form-fitting, long-waisted, boned bodice worn in the 1870s and 1880s–almost gives the appearance of armor as the name suggests

Dagging - an extremely popular decorative edging technique created by cutting that reached its height during the Middle Ages and Renaissance

Dalmatic Tunic - a t-shaped tunic with very wide sleeves; worn by both men and women during the Byzantine empire

Dashiki - a loose-fitting pullover tunic traditionally worn in West African cultures that was adopted by African diasporic communities as a symbol of African heritage in the 1960s and then more widely worn as a popular item of “ethnic” fashion

Dentalium Cape - or dentalium dress is a garment worn by Native American women that is made from the stringing together of dentalium shells in a circular pattern around the neck and across the chest and shoulders

Doublet - an often snug-fitting jacket that is shaped and fitted to a man’s body–worn mostly in the 15th to 17th centuries

Échelle - a decorative ladder of bows descending down the stomacher of a dress; worn during the late 17th and 18th centuries; sometimes spelled eschelle

If any of these words make their way into your next poem/story, please tag me, or leave a link in the replies. I would love to read them!

More: Fashion History ⚜ Word Lists

#word list#fashion history#writeblr#dark academia#spilled ink#writers on tumblr#writing prompt#terminology#poetry#poets on tumblr#literature#light academia#studyblr#linguistics#lit#words#fashion#culture#worldbuilding#creative writing#writing reference#fiction#writing tips#writing advice#writing resources

234 notes

·

View notes

Text

So, Wizarding Robes

I saw this post by @iamnmbr3 and @kittenjammer talking about wizarding fashion and I wanted to talk about this for a while, so I'm going to give my own two cents on it based on fashion history. I love history in general, but fashion history and historical architecture are two I’m incredibly passionate about. So, here we go (post with a lot of pictures ahead):

When I read the books and they mentioned unisex “robes” which function like dresses in a way (as you don’t have to be wearing trousers beneath them:

James whirled about; a second flash of light later, Snape was hanging upside down in the air, his robes falling over his head to reveal skinny, pallid legs and a pair of graying underpants.

(OotP, 647)

And described as being very colorful and billowing, often accompanied by a pointed wizard hat, it was clear to me JKR was trying to invoke the image of the classic fantasy wizard robe:

Especially when it comes to Dumbledore.

The thing is, this style is based on a real historical period and historical styles of the medieval period in Europe.

Medieval Europian Robes

When I'm thinking about the "classic fantasy wizard look" the first historical period that comes to my mind is the 15th century and I'll illustrate why.

Spesificly, the 14th and 15th centuries houppelande. It was a long over garment that looked kinda like a dress with wide, flaring sleeves available for both men and women in various shapes, cuts, and even patterns. Here are examples of some houppelandes:

(As you can also see, early 15th-century fashion comes built-in with silly hats! Just like wizards)

In the 15th century you also have a wide array of cuts of cloaks (and even more silly hats!):

Along with surcoats, that contrary to their name, weren't just for knights to signify on their armor the house they serve:

These 15th-century garments are exactly like wizard fashion is described in the books: billowing robes, colorful and eye-catching, and accompanied by silly hats.

The thing is, all these garments are from the high medieval period and as wizards broke away from muggles only when the Statute of Secrecy was enacted, I'd expect their fashion to follow the muggle trend up to that point and then start diverging. Even the most pure-blooded wizarding families of the modern day, like the Malfoys, integrated with muggle circles up until the Statue of Secrecy, something that would've forced them to dress like the muggles at the time to blend in better.

As the Status of Secrecy was first enacted in 1692, it's time to talk about:

Late 17th Century Fashion

Now, while the high middle ages in Europe had everyone wearing essentially wizard robes and silly hats on the regular, the Statue of Secrecy was enacted much later. Fashion in the 17th century was drastically different from the earlier one mentioned above.

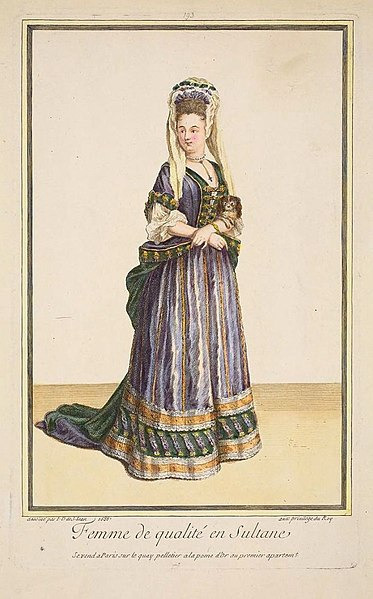

In the late 17th century, this is the kind of dress I'd expect from women in England:

And this is what I'd expect from men:

Which is very different from what is described but would've been the historical basis the wizards would work from.

So what do I think wizarding fashion is actually like?

Well, since the books are in the 1990s and wizards don't really live in a vacuum we know some later influences in fashion did make it in. So, I think wizarding fashion is an odd mix of 15th-century and late 17th-century fashions updated to the time period the wizard grew up in, hence distinct fashion changes between generations like we see in the muggle world.

We see these distinct generational fashion changes with characters like Agusta Longbottom who wears a Vulture hat. These sorts of hats with real birds on them were a thing historically. They were quite fashionable in the late Victorian era, which is when Agusta would've been a child if she's around Dumbledore's age:

Fudge is described as wearing a Bowler Hat, a kind of hat that started catching on in the late 19th century but was still a staple in menswear into the early 20th century, hence indicating Fudge's age.

Ron's yule ball dress robes are described as old-fashioned, again indicating fashions in the wizarding world change at a similar rate to the muggle one. Note that since the 17th century, fashion has been changing quite rapidly and by the 18th century fast fashion where you need to buy new garments each "season" has already started becoming a thing. With all that, I think wizard fashion indeed changes just as rapidly as the muggle one.

Now, that's great, and all, but, what would that odd mish-mash fashion even look like?

Well, I made a few very quick sketches as concept examples for what casual wizarding fashion in the UK might look like if we're working off historical references:

(not my best pieces, it's just to get the concept across)

Note that Wizengamot robes and other formal professional wear would probably be older in style and closer to 17th-century fashions.

#harry potter#hp#harry potter thoughts#wizarding world#hp meta#hp headcanon#wizarding fashion#wizarding society#harry potter meta#harry potter headcanon#hollowedtheory#hollowedheadcanon#hollowedart#hollowed hp redesign

334 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi, this is a bit of a shot in the dark on my end, but I have a fashion inquiry (and I apologize if I sound ridiculous at all; I’m a bit at my wit’s end).

Is there a good way to research forms of casual Victorian garb? I feel like I’m going a bad route by inserting the word ‘Victorian’ into any search because it results in rather fancy things (or modern twists on such that are purchasable). Would it be wiser to site dates in search? Is this going to fruitless?

Sorry for taking up any time if this is out of wheelhouse. But if you do answer, I really appreciate it.

I'll do my best! Focusing on womenswear, because...well, that's what I know best. But if anyone wants to chime in about the gentlemen, please do so!

So, casual Victorian doesn't always read as Casual to us nowadays. Standards of casual clothing- that is, clothing one wears for everyday life when nothing special is going on -were rather higher than we have today.

This is an illustration of matchstick-makers in London's East End c. 1871, done by one Herbert Johnson. The women have their sleeves rolled up and aprons on, but when they leave the factory (rolling their sleeves down, adding hats to go outside- which most of them would have done; it was part of looking Respectable) they might be indistinguishable to us from any other women of the same era wearing not particularly bustle-y skirts. Some of them probably have on the commonplace Matching Skirt And Bodice dress format of the era; others have on blouses made from the same patterns as those worn by middle- and upper-class women.

Also note that they have on ribbons, chokers, earrings...they're just like us. They like wearing things that make them feel Put Together, even though they're doing one of the lowest-valued, most dangerous jobs open to women at the time. Because people have always been people, regardless of time or social class.

And for middle-class women and up, Casual might be even harder to distinguish from "fancy" to us today.

This is a mid-late 1880s day dress with a skirt length suitable for lots of walking, from Augusta Auctions. Could not tell you the social status of the woman who owned it, genuinely. Probably not the absolute poorest of the poor, but beyond that...this is a dress you could potentially wear to run errands. Even to go to work, if your job wasn't especially physical. Because. I don't know. It's a Day Dress. You wear it for day things. It's not especially formal, because then it would be made of a more delicate material and probably have a longer skirt (unless it was a Serious Dancing ball gown). Possibly also a lower neckline and puffed sleeves, if it was exclusively for the most formal events.

The idea that a dress was "fancy" just because it had ornamentation wasn't really in their cultural vocabulary.

Here is a group of women playing croquet in what looks like the early-mid 1870s. They're just hanging out! Having a good time! They're probably middle or upper class, but that's what they wear to chill outside with friends- to play a lowkey sport, even.

So yeah, it can be hard to map Victorian everyday clothing onto our "jeans and t-shirt" understanding of what makes an outfit casual. They had skirts and blouses for most relevant decades, but even those outfits often end up looking formal to us nowadays because of what I call Ballgownification- the idea that, since we only wear clothes that look even vaguely like what they had for extremely dressy occasions, we assume everything we see of their clothing was dressy.

(Someone please ask for my rant about Ballgownification)

Searching for "day dress," "walking dress," "blouse," "blouse waist," and "shirtwaist" (the last for the late 19th-early 20th century when that term became commonplace) might help. Best of luck!

#victorian#history#fashion history#dress history#clothing history#ask#madsk3tch#even just Throwing Something On looks dressy if all you have to throw on is. that.#I make a lot of my clothes from extant patterns and people comment on how dressed-up and put together I look#which is very kind but. these are magazine patterns. anyone had access to them#and I often even take off some of the recommended trims no less#a casual blouse waist from 1869 looks quite dressy to a modern audience#long post

199 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cultural Fashion: Toph's Ba Sing Se Dress

While Katara's Ba Sing Se dress takes pretty direct inspiration from early 20th-century Manchu fashion, Toph's party outfit is more varied in its sources. Toph's ensemble appears to be inspired by the look of late 19th-century aoqun (襖裙), literally meaning "robe-skirt" in Mandarin. Like aoqun, Toph's attire possesses a short standing collar, a rounded cross-collar (pianjin), intricate trim along the collar and sleeves, and moderately wide sleeves.

However, there are also a few differences between what Toph's wearing and a traditional aoqun. Most obviously, Toph's top (ao) is cut quite a bit shorter than a traditional aoqun top. Her skirt is also not pleated, unlike traditional Qing aoqun skirts. I believe this is due to Toph's party design taking partial inspiration from traditional Korean women's clothing (hanbok/한복). The top's fit is much closer to the cropped style of a jeogori (저고리) and the silhouette is very hanbok-like. I don't think there's a particularly deep reason for this; the traditional silhouette of an aoqun is very boxy, while hanbok silhouettes are comparatively more form fitting. Form fitting designs tend to be easier to animate.

Overall, the design is cute, but I would have preferred to see Toph in a more faithful aoqun. I think looser clothes embody Toph's personal style more. ^_^

Like what I’m doing? Tips always appreciated, never expected. ^_^

https://ko-fi.com/atlaculture

190 notes

·

View notes

Text

Etiquette of the Edwardian Era and La Belle Époque: How to Dress

This is a new set of posts focusing on the period of time stretching from the late 19th century to the early 20th Century right up to the start of WWI.

I'll be going through different aspects of life. This series can be linked to my Great House series as well as my Season post and Debutant post.

Today will be focusing on the rules of clothes with this time period.

A Cut for Every Occasion

As you may know, the wealthy elite and their servants lived extremely regimented lives and every aspect was governed by careful rules. They would be expected to wear the right outfit at the right time, every minute of the day. Any misstep would be noticed at once and be subject to scruntiny.

In the circles of the elite, one would be expected to change for every occasion. One simply wouldn't wear the same outfit they've been lying around the house in to attend tea at somebody's house. Fashion in this era was dictated by the clock and by the event diary of the wearer.

Ladies

Women of the upperclass would be expected to change at least six times a day. When she would rise for a morning of repose around the house, she would simply wear a house gown or a simple blouse and skirt. If planning a morning stroll, she would change into a walking suit which is a combination of blouse, skirt and jacket along with her hat usually of tweed. If running errands or paying a visit to friends, she would wear another walking suit. If riding, she would wear a riding habit and a hat. If hosting tea or taking tea in her own home, she would change into a tea gown with is a lighter more airier gown more comfortable for chilling in. If attending a garden party, one wears a pastel or white formal day gown accompanied by a straw hat and gloves. For dinner, she would change into an evening gown which would be more elaborate and show off a little more skin than her day wear. After dinner and ready for bed, she would change into her nightgown.

Female servants had an easier time of it. A housekeeper and lady's maid would simply wear a solid black gown for the entire day. A cook and kitchen maids would wear a simple day dress for working with an apron. Housemaids would usually wear a print dress with an apron and cap, changing into the more formal black and white attire you would associate with a maid.

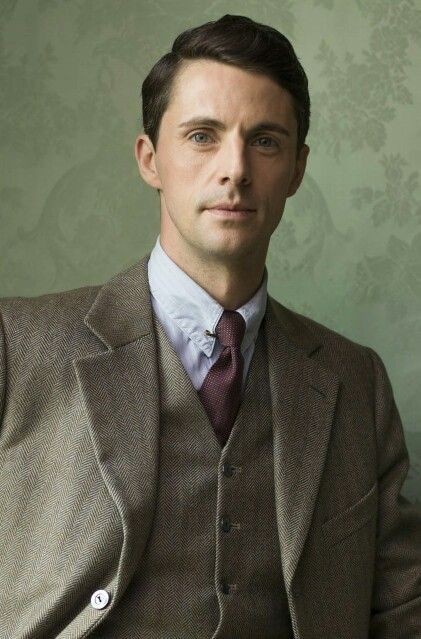

Gentlemen

The gentlemen had an easier time but they too were subject to changes throughout the day. Men were expected to wear a suit. The most popular day time suit was a sack suit. These were comprised of plain and loose fitting jackets, worn over a starched shirt with a high collar, waistcoat and straight trousers with ironed creases. These suits were exclusively wool with cheaper ones made of a wool and cotton blend. Grey, green, brown, navy were usual but sine younger men preferred louder colours such as purple which was a trend for a time in the 1910s. These suits were worn about the house or in the city accompanied by a coat. Men would change into tweed if shooting or walking. For garden parties, a gentleman would wear a light coloured suit, usually white and a straw hat. For dinner, a man had two choices: his tails or his dinner jacket. A dinner jacket was for less formal suppers say if dining at home. This was a collection of a jacket, trousers, waistcoat, a bow tie, a detachable wing-collar shirt and black shoes. Lapels of these jackets were edged with silk or satin. Tails were worn at a formal dinner party, at White Tie events. This was made up of a tailcoat, white piqué waistcoat, a starched dress shirt with a pique bib and standing wing collar with a white bow tie. Trousers were lined with trim to hide the seams.

Male servants were soared changing. Footmen would wear their livery around the clock which would resemble white tie to a certain extent or mimic court dress of palace servants. Butler's would wear a variation of a gentleman's evening suit throughout the day. When a male servant is dressed, he usually stays that way. However, a valet or a footman may be taken to pick up during shooting parties where they would wear tweed walking suits.

Jewellery

Jewellery was an important sign of status in society. Upperclass women of this time has access to untold caches of sparklers but there were rules concerning their use and meaning. Earrings were usually clip ons as women of high status would not pierce their ears. Simple, understated earrings were worn during the day with more ostentatious sets were worn in the evening time. Broaches were popular at this time, usually worn at the throat of a gown or blouse or walking suit or affixed on hats. Large stoned rings were worn over gloves while slender bands were worn under. Jewellery was intricate and understated amongst old money whole the nouveau riche went for chunkier stones and larger settings. Tiaras were only worn at White Tie events, held after six pm and almost never by unmarried girls. One would not wear a larger tiara than that most senior lady present. Men would wear tie pins, cufflinks and pocket watches to match any occasion be it for a jaunt on the town or at a formal evening party.

Hats

Hats were a staple in this period. Anybody respectable from any class wouldn't venture out of the door without a hat.

Men would wear hats when heading out but always remove them when entering a building, and never wear one without removing it for the presence of a lady. The bowler was seen as more a servant's headwear while a top hat was reserved for gentlemen. Flat caps would be only seen on gentlemen at shooting gatherings or in the country, they were popular among the common class for any informal occasion.

Women had more stricter rules concern hats. Hats for women were more a day accessory worn while out and about. A woman would not wear a hat in her own home even when entertaining and nor would any of the other female occupants if joining the gathering. A woman would not remove her hat when attending a luncheon or tea or any activity. Hats were held in place by a ribbon or sash tied under the chin or by a hat pin, which is essentially a large needle thrust through the hair. This was the period where women's hats became more ornate and rather large, leading to some critisism. Among servants, housekeepers and lady's maids would not wear a hat while indoors and working but a housemaid or cook or kitchen maid would cover their hair with a cap with housemaids changing into a more elaborate one come evening time. Male servants would not wear hats unless travelling or outdoors.

Gloves

Gloves are a staple in this period and worn only at the opportune time. Among servants, only footmen would wear gloves and usually only when serving. Butlers would never wear gloves. Female servants did not wear gloves.

Men did wear gloves, usually woollen or leather while outside or riding gloves when out on horseback.

Women wore gloves whenever outside. Day gloves were usually wrist length, with evening gloves stretching to the elbow. During dinner, evening gloves would be removed at the first course and laid across the lap, replaced at the last course when the ladies leave for tea and coffee after where the gloves are then removed again. Gloves are always worn when dancing and at the theatre or opera. If one is sitting in ones box and sampling some chocolate, one can remove their gloves for that.

Hair and Makeup

Make up was a no-no amongst the upper crust and for their servants in England and America, as it was seen as licentious but in France, the use of rouge was accepted. Perfume and cologne were acceptable but excessive use was frowned upon.

Hair was dressed by one's lady's maid. Bouffant updos were popular in this time period for married women. During the last years of this period, women began adopting the 'bob' but this was seen as radical and sometimes scandalous. Unmarried girls could wear their hair down, often with accessories like a bow to adorn their tresses. Servants would always tie up their hair and never be seen with it down or uncovered (though this depended on their job).

Men would comb their hair, slicking it back for dinner. Most men were clean shaven but if they wore beards, they were usually well groomed. Hair was kept short for grown men and teenagers but young boys may wear their hair longer whilst in the nursery.

#This bitch loooonnnnggg#Etiquette of the Edwardian Era and La Belle Époque series#Fantasy Guide#Early 20th Century#late 19th century#Great houses#writing#writeblr#writing resources#writing reference#writing advice#ask answered questions#writing advice writing resources#writers#Writing advice writing references#Writing references#Historical fiction#1900s#1890s#Fashion

636 notes

·

View notes

Text

as someone whos not normal about late 19th and early 20th century womens fashion its so annoying when people ask me if i like maid dresses. to put it bluntly im a lesbian not a straight man with no personality

80 notes

·

View notes

Photo

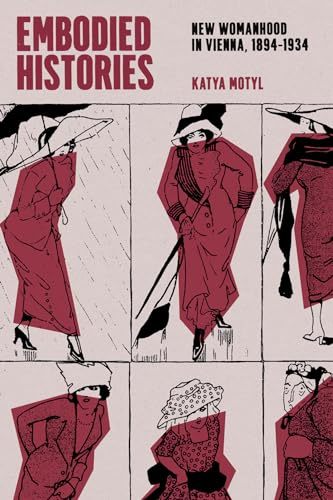

Embodied Histories: New Womanhood in Vienna, 1894–1934

"Embodied Histories" by Katya Motyl explores the intersection of gender, modernity, and urban culture in Vienna during the late-19th and early-20th centuries. This book is an enlightening resource for university students focusing on modern European history.

When first picking up this book, the reader might not expect to stumble upon police reports regarding wrongful arrests of Viennese women at the turn of the century. As a contemporary reader, what is provided on the pages of Katya Motyl’s new book is enlightening yet infuriating.

Embodied Histories: New Womanhood in Vienna, 1894–1934 by Katya Motyl explores the intersection of gender, modernity, and urban culture in Vienna during the late-19th and early-20th centuries. Motyl is a cultural and social historian, Assistant Professor of History, and Affiliate Faculty of the Gender, Sexuality, and Women’s Studies Program at Temple University.

Her book, written successfully and with expert knowledge, focuses on the "New Woman" concept and is aimed at scholars and students of global history and gender studies. The New Woman, described by Motyl, was symbolic of changing traditional gender roles and aspirations among women in Vienna whether she was aware of the change or not.

Through a combination of historical analysis and cultural critique, Motyl examines various aspects of the experiences of the New Woman in each chapter. These include her participation in public life, her engagement with emerging feminist movements, her portrayal in literature and art, and her embodiment in fashion and lifestyle choices. Motyl offers readers an in-depth discovery of unbearably truthful historical scenarios based on her thorough research of documents, including police reports, court records, and more. This well-rounded research approach makes the book compelling, unique, and a must-read for anyone studying European history, women’s history, or sexuality.

According to Motyl, at the turn of the century, women in Vienna were apprehended by police simply for walking outside at night or dressing in non-traditional feminine outfits. The eye-opening and informative stories and the voices of the women affected are revealed throughout the text. The instances of women unable to speak freely about their emotions or thoughts are also mentioned, giving readers insight as to why human rights and women's rights are important yet still challenged today.

Outlets such as theater or sanatorium visits were usually the only means of expression for women in Vienna during this time. The information included in this often heart-wrenching text is sewn together with various forms of artwork. Tying the stories together with cartoons, sketches, and even the era's political drawings showcases society and gender norms, displaying the mindset of people who lived during the turn of the century in Vienna.

The adoption of new styles and beliefs together with the rejection of outdated norms during this period were seen as significant acts of rebellion, leading to police interactions, as women searched for self-expression. With this book, their experiences are brought to light. Embodied Histories reflects broader changes in gender roles of women and societal expectations of them in early 20th-century Europe, laying the groundwork for further advancements of women’s rights and social equality in the future.

Katya Motyl has contributed a significant gift to cultural and social history research with her book. Motyl's effort in demonstrating how Viennese women contributed to and were shaped by the city's dynamic cultural milieu offers insights into their individual experiences and collective impact on society.

Continue reading...

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Tailor & The Seamstress - A Reading Aid

So here's some stuff I'm just putting up here as a kind of glossary/reading aid/moodboard collection for The Tailor & The Seamstress.

It's not an easy read in some ways, because it's set in 1910 and deals with some fashion terminology that can be opaque, so yeah. Just dropping this here.

Accents

Firstly, Remy and Anna do not speak in their accents, and that was deliberate. Working where and in what they do (i.e. haute couture in 1910's New York), having a Southern accent would have been very uncouth. For professional reasons they would have got rid of their accents, or polished them off, fairly quickly. But both of them actually filed off their Southern accents earlier in life, for entirely different reasons (which will become clear later on in the story).

The closest you'd probably get to what they sound like is probably the Transatlantic accent, which developed in the late 19th century in the acting industry and among the American upper class. (Thanks to @narwhallove for pointing this out!).

You can hear what this accent sounded like in 1930's and 40's Hollywood movies:

Dress Forms

There are a lot of dress forms floating around in this story. A dress form is very much like a mannequin, where a garment can be mounted on it to make working on it easier. The difference between a dress form and a mannequin is that a form can be adjusted to different sizes. Here's an example:

Nowadays, dress forms usually conform to modern standards of sizing, but back in the day, all dressmakers/fashion houses would have dress forms made according to the sizing of their target clientele, and adjustments would be made to individual customers when a dress was purchased.

The dress forms at the House of Burford, of course, are made to Anna's measurements. 😉

Maison Maillot

The idea of Remy working at a waning fashion house was inspired by the historical House of Worth, which was probably the world's first modern atelier. Established in 1858 by Charles Frederick Worth, it came to dress empresses, queens, actresses and singers. The business was later taken over by his sons, but the house's fortunes waned in the early 20th century. IMHO, you begin to see the decline in design quality by the 1920's. Worth was bought out by the House of Paquin in 1950, and closed in 1956. In 1999, it was revived.

Early Worth designs were so powerfully beautiful, and always innovative and at the cutting edge. In the story, the House of Maillot's heyday would have been the same - a tale of an exciting and forward-thinking atelier that dressed the best and brightest.

By the early 20th century, at the time of the story, they are still putting out beautifully breath-taking clothes - but decades of newer competition means that their work no longer stands out. By the 1910's, the House of Worth had been eclipsed by designers like Callot Soeurs, Paul Poiret, and Lucile (of Titanic fame), who were becoming the innovators in women's dress, and Worth tended to follow where others led. This is where Maison Maillot is at in the story; and their rival, the House of Burford, is one of those new and exciting innovators in fashion.

By the 1920's, fortunes have fallen, and the House of Worth was putting out stuff like this:

The Peacock and the Phoenix Dresses

The rival dresses don't have any analogue in real life, but here are the dresses that roughly inspired them.

A 1909 evening dress by Callot Soeurs:

And a 1913-14 evening dress by an unknown artist:

I like to think of Remy always being slightly (maybe a lot) more ahead of his time with his clothes than Anna is with hers. Remy is designing tubular dresses a few years before they started to become a fashionable silhouette. Ironically Maillot rejects them, but I find it kind of funny that by the end of the decade, he'll have been wishing his house had set the trend Remy had conceived of years before.

At SOME POINT I will draw how I envision the dresses to be. I HOPE.

If you want to see my moodboard for this story, you can catch it on Pinterest here.

#The Tailor & The Seamstress#fanfic#meta#reading aid#historical fashion#historial fiction#historical fic

29 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello! I was wondering about the evolution of kimono styles throughout Japanese history. I have a rather static image of what they look like, but being into general historical fashion made me question if it really was as unchanging as I imagine. For example, the Edwardian and Victorian silhouettes, or Tang dynasty qixiong and Ming dynasty aoqun look very different from each other. Did kimono have they own trends that amateurs don't know about?

Part 2: Hi, just to clarify, I mean general fashion trends, for both men and women (though I'm leaning more women). Also, I was wondering if there was a disparity between geimaiko trends which separated them from "normal" women. In certain cultures, courtesans and entertainers were trendsetters. The kimono as we know it today, the kosode, has been around for approximately 600 years or so. In that time not much has changed in its shape, but rather all changes have been made in length and material. Until the late 19th century almost all kimono were worn while dragging along the floor, so they were longer than their contemporaries. In terms of material, obviously the richest members of society had the most lavish kimono, which are the ones that have survived in the highest quantities to this day. From what we know as the "modern kimono," which dates to the Edo Period (1603-1868), we know that goshodoki (views of the nobility) were a very popular motif on kimono for both women and younger girls (kosode and furisode) and were worn on their best kimono. Goshodoki began to fall out of favor just before the Meiji Period, so around 1840-1850, when Japan began to experience upheaval and Western influence. When it comes to influences and influencers, The Edo Period once again strictly controlled what people could wear due to sumptuary laws. There were many ways that people got around these laws, but for the most part you had to dress in what was prescribed for your social class. Courtesans were in a class above those of the "normal" people, so they weren't setting any trends for clothing (although they did with their hair). However, it was the geisha who were trendsetters for the common people as they belonged in the same class. What a popular geisha wore was quickly copied by other geisha, which was then in turn copied by townswomen. The only real control that they had over their wardrobe were the patterns on their kimono and obi, which, although still regulated, could be presented in unique ways or new color patterns. With the end of the Edo Period came the end of sumptuary laws and a fair degree of Western influence in everyday Japanese life. Kimono were now shorter as people no longer wore them dragging on the floor (except for geimaiko) and motif placement had to change to due to the adoption of Western furniture. Kamon (family crests) on women's kimono grew smaller but with them came added motifs on shoulders that weren't seen before as now most motifs on kimono couldn't be viewed properly on Western style chairs. Western style motifs and artistic styles also began to be adopted in the early 20th century in a time known as the Taisho Roman. Kimono production boomed during the Taisho Period (1912-1926) as Japan was expanding its foreign territories and the economy soared. The different types of motifs and and the sheer richness and sparing of no expense was something that has never been seen before and will never be seen again. Sadly then came World War II, production stopped, and when it resumed it was much more subdued as people moved to Western clothing as their main clothing of choice. Kimono were still being produced throughout the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s with a fair amount of regularity, but the burst of the bubble economy in the 1990s lead to a sharp decline in kimono production. It's only been within the last 10 years or so that a "Kimono Renaissance" has been taking place that has lead to both foreigners and Japanese nationals rediscovering the iconic garment, with an uptick in indie designers leading the way in new fashions rather than older fashion houses ^^

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ladies Fashion Illustration, The Delineator, September 1913.

The Delineator was an American women's magazine of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, founded by the Butterick Publishing Company in 1869 under the name The Metropolitan Monthly. Its name was changed in 1875. The magazine was published on a monthly basis in New York City. In November 1926, under the editorship of Mrs. William Brown Meloney, it absorbed The Designer, founded in 1887 and published by the Standard Fashion Company, a Butterick subsidiary. (x)

#fashion illustration#illustration#1913#the delineator#magazine#september#september issue#1910s fashion#1910s dresses#1910s mode#autumn fashion#fall fashion#delinator#hats#big hats#aigrette#day dresses#day outfits#ladies#womans magazine#1913 illustrations#chic#american#American fashion#American fashion history#fashion history#art

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

Remember how I said I'd talk about the guy who looted the UFO in my Dialtone lore post?

Let's talk about Nathaniel Robot.

Born in the early 19th century to middle classed immigrants, Nathaniel initially led a fairly standard life. Then at the age of 8, they left him behind on a family trip and were so caught up in frontier shit they failed to notice and get him back for two years.

A born entrepreneur, Nathaniel made his first break into business running a way station and general store. He quickly changed his surname to Robot, a set of random letters he got by asking strangers for their favorite letter, from his birth name of Murderface, fearing the effects it may have on business.

Nathaniel made his initial fortune, however, with a different business. He made his journey west, as was fashionable at the time, and he noticed a few things rather obvious nowadays.

1: People are happy to work for you if you treat them well, especially if other places won't.

2: There were a lot of women and minorities who wanted to get into various fields, but were unable to because this was the 19th century.

With this knowledge, he set about founding a variety of businesses with the fundamental principle of hiring and treating people solely off of the quality of their work. As you can guess, he was also staunchly pro-union. Because this is my fun lil oc world and I'm god, this worked great for him.

After some years of success and significantly moving the cultural norms leftward, he moved to Alaska in hopes of high yield snow farming. While there, he discovered an alien space ship which had crashed some years prior. Like any right thinking American, he investigated alone without telling anyone. Some time later, he ran into the nearest town raving of devices 'beyond comprehension' and scheduled a demonstration. Once the day came, he showed off a computer he's fixed up, powered by a solar panel he'd pried off the ship.

After he threw money at someone smart to reverse engineer the technology, he'd essentially thrown technology ahead over a century, furthering his business. Despite this, he made many of the patents public with the logic that if someone added a brilliant extra, he could hire them, or give a grant. He was less a brilliant businessman than lucky, and the type who's willing to throw money at anything vaguely interesting.

While technology was able to extend Robot's life significantly, he eventually passed away in the mid 20th century. However, he went out with a bang, mere weeks after announcements of his company creating the first autonomous computer, dubbed a robot in his honor.

Robot's was also a life-long supporter of civil rights movements, known for bragging about his 'anonymous' donations to whichever groups looked most likely to make an effective difference. These actions by someone with an enormous influence (just look at Edison [fuck Edison], or Carnegie for people who could approximate his status) resulted in much of that world achieving the closest to full equality and equity you're going to get in the late 20th century. A known bisexual, Robot's suspected relationship with gay activist Steven Mandater would likely have resulted in scandal if not for the public perception of him being batshit insane anyway.

Examples of what caused that view were his claim that seagulls only don't talk for fear of paying taxes, his claim to have invented calculus before Newton, and the fact that before anyone told him of motion picture technology he withdrew into his rooms for a week before returning with a full script for what would to a person from our world be recognizable as the original Star Wars trilogy.

#nathaniel robot#batshit oc#oc#oc lore#oc history#seagulls#hes kind of like my bootleg cave johnson#though cave probably wasnt liberal#ocs

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

1880s: Dominique is very Masculine, and very Eccentric

In today's standards, Dominique is a fairly feminine woman. Yes she's wearing a prince inspired outfit, but it's feminized with the tight pants, long stockings, heels, and long hair, but what if I told you that was all considered masculine in the olden days?

The Time Period

Givn the story takes place when the alternate Eiffel Tower (can't remember the name) was being built, we can assume vnc takes place in the late 19th century, otherwise known as the Victorian era, ranging from 1820 to 1914.

The fashion looked somewhat like this, you can see some similarities to the outfits worn by the main cast.

Dominique's outfit doesn't really resemble much of the fashion at the time, you can make som mild comparisons to Victorian royal menswear, but I'd say her fashion is more similar to 17th century royal menswear, specifically,

King Louis XIV

The long hair, the tight white bottoms, the heels, the loose sleeves, the train of fabric behind him, It is said that King Louis was a big womanizer, who does this all sound like? It's almost as if Dominique is trying to be Louis- oh wait.

Also fun fact, King Louis XIV was born in Saint-Germain-en-Laye.

Masculinity & Eccentricity

For us in the present, King Louis XIV looks pretty feminine, and that was probably a shared sentiment in the 19th century, he looked outdated, but that same outfit on a woman like Dominique would cause some controversy if not for her status.

In the 19th and early 20th century, a woman wearing pants was not too accepted, women usually wore dresses, and pants were kept as a sports/work attire. A woman would not just go on about her day wearing a pair of pants, she'd be seen as strange, and maybe even get into trouble. Dominique wearing pants, and very tight pants reminicscent of older eras, is definetly a bold choice.

Her hair is long and straight, which is not how you'd usually describe a victorian woman's hair. It wasn't even that much of a gender thing, but more of a formality thing. Women at the time would have their long hair in an updo. Actually, according to Whizzpast, long loose hair was a thing only models and actresses wore to depict romantisiscm and intimacy.

Dominique's long hair makes a lot of since, she has a bold, eccentric personality, she's not one to conform, she's the current family outcast, but she is also a very romantic person, and is constantly seen in romantic/intimate scenes, so her loose hair really depicts that.

All in all, Dominique's appearance states a bold, romantic blast to the past with a pinch of her desceased brother.

If you want to look into queer subtext, you can assume that''s one of the reasons Noe drinks her blood.

#damn this is the longest analysis/essay I've done in a while#vnc really makes me think#vnc#vanitas no carte#dominique#dominique de sade#french fashion#fashion history#anime#manga#the case study of vanitas

59 notes

·

View notes

Note

hello! i am a longtime huge admirer of your clothing/fashion sense, as well as a longtime backreader of your #victorian and #goth tags. i am really interested in what you've written about Victorian dress, and i am looking to get more into 19th and 20th century clothing for gender + diy craft reasons. i'm so sorry if you've answered similar questions before, but do you have any tips for where a newbie should start researching? either way, thank you thank you, your blog opens my mind wide and brings me much joy and reflection!

General research:

Spend some time searching the 'net, museum websites, and archive sites for fashion plates (such as archive.org—link leads to a date-restricted query for "fashion"—or the Smithsonian—link leads to fashion plates in their image collection). Take note of what you like, as well as which styles correspond to which decade. Karolina Żebrowska has a good rundown of English fashion over the decades.

The undergarments are what does the most work creating the necessary silhouette to make Victorian & Edwardian womenswear fit properly. If you've figured out a decade you want your outfit to draw on, doing a quick search for "[decade] undergarments" should bring up plenty of blog posts, which may or may not cite primary sources (such is the fickle nature of the historical blogosphere). Bustle pads and sleeve supports can be purchased or made; they're both pretty simple, and tutorials abound.

Purchasing clothing:

Reproduction made-to-measure clothing can be readily found on etsy, but can be in the several-hundred USD range. I've had some luck finding vintage reproduction clothing (like, a skirt someone made by hand in the 1980s to a 1900s walking skirt pattern), which tends to be much cheaper.

Men, women, and children wore stays and corsets. As far as I know, Orchard Corset has the cheapest OTR corsets that are good quality and safe to wear. If you get a corset in the style of a specific decade handmade or made to measure, make sure that the seller tells you what the boning material is, what construction the boning is (spiral steel is sturdiest and most flexible), how many bones there are, what the corset material is, &c.—otherwise it's an indication of an unserious maker. Follow general advice for wearing corsets at a waist reduction (lace up slowly, break it in, &c.).

Antique Menswear on youtube gives a lot of good, practical advice for wearing late 19th-century and early 20th-century men's clothing (including where to buy reproductions and how to treat them, how to modify modern shirts to 19th-century standards with basically no sewing skills, &c.).

Actual antique clothing can be found and purchased online or at estate sales—usually in very small sizes, but I've seen Edwardian skirts and petticoats in an XL (also a small size, but...). You can also just simply browse this kind of thing for inspiration and save photos of anything you think you'd like to recreate.

Even clothing that was not "meant" to be worn by re-enactors can be clearly historically influenced (e.g. the huge boom in Victorian- and Edwardian- style blouses in the 1980s), so keep an open mind when shopping for vintage clothing! A lot of 1970s dresses that look "hippy" on their own can look very Victorian with the right undergarments and an updo. A lot of 1980s men's trousers also approach the right silhouette for the 1910s-inspired three-piece suit I'm trying to put together. Witness also the recent trend for big puffed sleeves!

Making or modifying clothing:

Victorian and Edwardian manuals for garment drafting and sewing can be found online—go to archive.org and search for "sewing," "drafting," or "dressmaking," then use the filters on the left to chuse which year(s) you want to see results from. Most of these have patterns that are sort of vibes-based: The work-woman's guide is one manual that claims to have patterns laid out strictly according to a grid.

I don't sew garments, but if Victorian pattern-writing for sewing is anything like it is for knitting, that may not be super useful. People do sell updates and graded 'translations' of antique patterns (which tend to be written in only one size) on etsy and ebay—just make sure from the description that it's 'deciphered' and translated rather than a scan of the original pattern!

One of the easiest things that you can do to add some Victorian or Goth flair to an otherwise plain-looking garment is to add trim. You can knit, crochet, or tat your own trim from Victorian lace-making patterns; purchase antique trim from resale sites; or buy braided or lace trim very cheaply at any craft store. Trim doesn't just have to go around the hems and cuffs of a garment: lace "insertions" between two pieces of fabric, as well as raised geometric patterns over the surface of a garment, are common in 19th-century clothing.

[ID: first image shows a black overdress showing lace insertions between strips of fabric of equal width, creating a striped effect. second image is the back of a black blouse with trim in a geometric design centred around right angles and parallel lines. end ID]

Jewellery (women's and men's):

Actual antique jewellery (including men's jewellery and fastenings) is not as expensive as you might think. Even if you're not willing to spend a lot of time learning what to look for and scouring estate sales for people who don't know or care what they have, late Victorian mass-manufactured costume jewellery often goes for sub-$50 or even $30 prices at auction on ebay (USD, in the US—in my experience it is even more plentiful and cheaper in the UK).

Specifically, I've lucked out with lots ("lot" as in, a bunch of small things being sold together) of "vintage men's accessories" going for $20 or so that contained Victorian cufflinks (in low-karat gold, mother-of-pearl, and jet), collar studs (in low-karat gold and base metals), and shirt studs (in low-karat gold, with garnets and seed pearls, &c.). Searching for lots of accessories is generally a good idea since by and large people do not know what these things are... but if you're willing to spend a little more for something that has been identified and is more likely to still be with its set, use the specific search term for that item (e.g. "antique collar studs").

Answers to Questions About Old Jewelry (though aimed at estate sellers and, if memory serves, full of regrettable pæans to Queen Victoria) is a good reference text to dating antique jewellery. I also recommend Miller's Illustrated Guide to Jewelry Appraising. Both of these texts are available on libgen.

Feel free to ask me follow-up questions if you want more detail on any of these points. As you can see I am perfectly happy to blather away on this topic

85 notes

·

View notes

Text

my dream guidance for 19th-early 20th century women's garment labeling in museums

instead of "mourning dress", "[insert time/formality modifier] dress, suitable for [early-stage/late-stage] mourning"

instead of "morning/afternoon/walking/traveling/archery/tennis/whatever other random descriptor can be attached to a generic Long Sleeves High Neckline Practical Fabrics Reasonable Skirt Length dress," "day dress"

instead of "dinner dress/visiting dress/promenade dress," "semiformal dress"

instead of "ball gown/opera gown," "formal gown"

instead of "wedding gown," "gown worn by [name of bride] for her wedding" UNLESS it matches the modern definition of a wedding gown, ie "gown made and worn exclusively for this woman's wedding and instantly recognizable to all who see it as such." because when you say "wedding gown," that is what people now assume you mean

if the provenance is not known and it doesn't match the modern definition...why are we calling it a wedding gown? you have no evidence for that. stop it.

I don't care if we pick "robe" or "dressing-gown" or "wrapper" or "house dress" for Thing Worn When Hanging Out Around The House Sans Company, but for the love of god, can we all just pick one

ACTUAL specialized garments can keep their labels the same- nightgowns, sporting attire specifically made for that sport eg. cycling bloomers, etc. -and obviously styles of dresses with their own titles, eg. Edwardian lingerie dresses, can retain those

But guys. We've got to have more clarity on this than extant fashion magazines where a gown might be labeled one thing in the picture and something else in the text description

I KNOW they used all those terms back then, but they weren't trying to EDUCATE A PUBLIC WHO HAS NO CONTEXT FOR ANY OF IT

#museums#dress history#fashion history#this is why everyone assumes they changed clothing six times a day#surprise! they did it situationally! like we do! yes even the rich women!

273 notes

·

View notes

Text

I really hope you will find this interesting and maybe even useful.

APS is a Custom GPT I made. And it figures out old photos, sometimes pretty obscure ones.

I've been testing it for some time now and while being far from perfect, it appears to be quite a useful device, i would say, surprisingly so. And I would really appreciate it, if you give it a try, — and maybe even provide some feedback

[Only ChatGPT Plus users have access to Custom GPTs for now; hopefully this will change soon].

Case study

I asked it to "tell me all there is to know about this image:

It was found on Flickr with the caption "Pardon of Folgoet 1923", which, frankly speaking, made no sense to me — except for the year, of course. Now I know that Pardon is a religious ceremony, rather specific to Bretagne, where Folgoët is located.

What follows is rather a detailed report of APS findings, —and while being maybe a bit too general, it was also acccurate, quick and quite instructive indeed. Here it is:

This photograph provides a fascinating glimpse into the past, capturing a moment that speaks to the era's cultural, societal, and technological aspects. Let's analyze the various elements:

Architecture and Location: The building in the background is made of stone, indicating that this photo could be from a region where stone was a common construction material, possibly Europe. The style of the shutters and the architecture suggest a setting in a small town or village.

Signage: The sign reading "BYRRH" suggests a location where French is spoken, as Byrrh is a French aperitif that has been produced since the 19th century. This could place the photograph somewhere in France or in a French-influenced area.

Fashion: The attire of the individuals is very indicative of the time period. The women are wearing long dresses and hats typical of the late 19th to early 20th centuries. The boys are dressed in what appears to be sailor suits, a popular style for children from the mid-19th century onwards, as per the knowledge sourced from the documents provided.

Children's Clothing: The boys are dressed similarly, indicating a uniform, which could imply they are attending a special event or are part of a school group. This was a common practice in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Flags: The flags are difficult to identify clearly, but they seem to be fluttering in celebration or a public event, which could help date the photograph if the event is known.

Street Scene: The cobblestone street and the relaxed posture of the people suggest a peaceful day-to-day moment, rather than a staged photograph.

Photographic Style and Quality: The clarity of the image, along with the candid nature of the shot, suggests it was taken at a time when street photography became more feasible due to advancements in camera technology. This could be in the late 19th or early 20th century, aligning with the Kodak Brownie introduction in 1900, making photography more accessible to the masses.

Umbrellas and Sunlight: The presence of umbrellas could indicate either a sunny day or an impending rain, but the shadows suggest a bright day, with the sun high as indicated by the short shadows.

From these observations, it seems likely that the photograph was taken in France or a French-influenced region during a public event or gathering, likely in the late 19th or early 20th century. The combination of the children's uniforms, the women's fashion, the stone architecture, and the photographic quality all contribute to this conclusion. However, without more context or specific historical knowledge, pinpointing an exact date or event is challenging.

#AI#vintage style#retro style#Vintage-Stil#生成的#生成艺术#人工智能艺术#集体#LLM#chat gpt#ai tools#DALL-E#photo dating#photo attribution#obscure photos#antique photos#history#Bretagne#histoire#história#Geschichte#歴史#historical#historisch#histórico#historique#vintage photos

30 notes

·

View notes