#king of phrygia

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

Phrygia

Phrygia was the name of an ancient Anatolian kingdom (12th-7th century BCE) and, following its demise, the term was then applied to the general geographical area it once covered in the western plateau of Asia Minor. With its capital at Gordium and a culture which curiously mixed Anatolian, Greek, and Near Eastern elements, one of the kingdom's most famous figures is the legendary King Midas, he who acquired the ability to turn all that he touched to gold, even his food. Following the collapse of the kingdom after attacks by the Cimmerians in the 7th century BCE, the region came under Lydian, Persian, Seleucid, and then Roman control.

Historical Overview

The fertile plain of the western side of Anatolia attracted settlers from an early period, at least the early Bronze Age, and then saw the formation of the Hittite state (1700-1200 BCE). The first Greek reference to Phrygia appears in the 5th-century BCE Histories of Herodotus (7.73). The Greeks applied the name to the Balkan immigrants who, sometime after the 12th century BCE, relocated to western Anatolia following the fall of the Hittite Empire in that region. The kingdom's traditional founder and first king was Gordios (aka Gordias). A legendary figure, Gordios is most famous today as the creator of the 'Gordian Knot', a fiendishly difficult piece of rope-work the king had used to tether his cart. The story goes that an oracle had foretold that the person who knew how to untie the knot would rule over all of Asia, even the whole world. The cart and the knot were, incredibly, still there at Gordium when Alexander the Great (356-323 BCE) arrived a good few centuries later. Alexander was said to have heard the story and, rather unsportingly, sliced the knot open with a single blow of his sword. In other accounts, the young general slipped the pin out of the cart's yoke pole and slid the knot off that way.

The neighbouring states of Phrygia, which similarly formed out of the remnants of the Hittite Empire, were Caria (south), Lydia (west), and Mysia (north). Phrygia's territory expanded to reach Daskyleon in the north and the western edge of Cappadocia. Phrygia prospered thanks to the fertile land, its location between the Persian and Greek worlds, and the skills of the state's metalworkers and potters. Chamber tombs, especially at the capital Gordium, have distinctive doorways and their excavated contents have revealed both the use of the language of Indo-European Phrygian (from the 8th century BCE) and the wealth which gave rise to the legend of the fabulously rich King Midas (see below).

Phrygia was conquered by the Cimmerians in the 7th century BCE but the period of domination by Lydia and Persia has left an impoverished archaeological record. We know that Lydia expanded under the reign of the Mermnad dynasty (c. 700-546 BCE), and especially King Gyges (r. c. 680-645 BCE). Phrygia was absorbed c. 625 BCE with Gordium conquered around 600 BCE. Lydia then continued to prosper with such famed kings as Croesus (r. 560-547 BCE). Over the next century, the Persians took over Anatolia following the victory of Cyrus II (d. 530 BCE) over the Lydians at the Battle of Halys in 546 BCE. The region was then made a Persian satrapy. Phrygia continued to be used as a label of convenience for the general and ill-defined geographical area which had once been ruled by the now-defunct kingdom of that name.

After the campaigns of Alexander the Great, the region of Phrygia/Lydia came under the control of one of Alexander's successors, Antigonus I (382-301 BCE). Shortly after, Anatolia became a part of the Seleucid Empire c. 280 BCE. As a consequence of this takeover, many settlers came from ancient Macedon and their Hellenistic culture with them. Notable Phrygian towns in this period besides Gordium included Hierapolis, Laodikeia by the Lykos (aka Laodicea), Aizanoi, Apamea, and Synnada, although most of the region's population lived in small, agriculturally-based villages.

Phrygia became a part of the Roman province of Asia (with a part in Galatia, too) in 116 BCE, and the region now grew in scope, at least as a geographical term. To quote the Oxford Classical Dictionary:

During the Roman period the region extended north to Bithynia, west to the upper valley of the Hermus and to Lydia, south to Psidia and to Lycaonia, and east as far as the Salt Lake (1142).

Phrygia then became embroiled in the Mithridatic Wars of the 1st century BCE between Rome and the kings of Pontus. With the reign of Augustus (27 BCE - 14 CE), there followed a period of peace and stability in the region. Prosperity was ensured by the continued fertility of the land and the important marble quarries near Dokimeion - stone from there would be used in such buildings as Trajan's Forum in Rome and the Library of Celsus at Ephesus. Into the 3rd century CE, the culture of the region had become a mix of indigenous Anatolian, Greek, Roman, Jewish, and Christian practices and customs. The Phrygian language, as attested by inscriptions, was still in use in the 3rd century CE, although it is called New Phrygian by historians to distinguish it from the Old Phrygian used when the kingdom itself was in existence (the link between the two was likely created by the language being spoken only as a vernacular in the interim).

Continue reading...

123 notes

·

View notes

Text

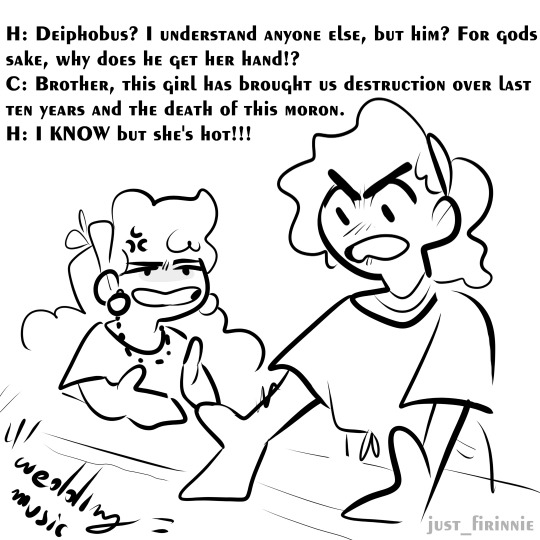

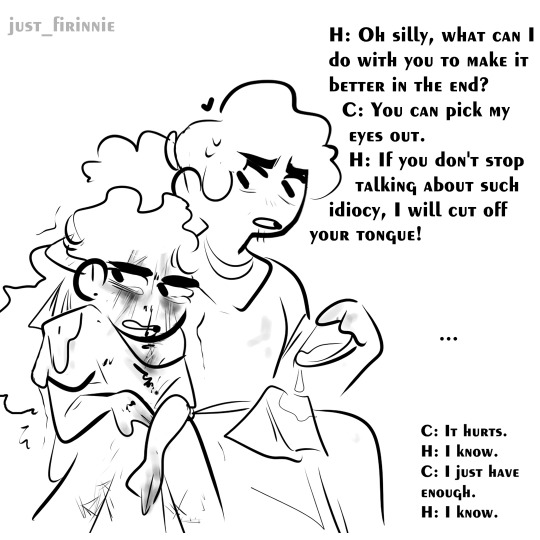

Oracle twins of Troy!

In general, I have a lot of golden thoughts so it's nice if you read them! As I love Cassandra, I am also fascinated by her brother Helenus.

In my Au Priam and Hecuba sent Helenus (then called Scamanderus) to Phrygia. This is a special place for two reasons, because one of the suitors of Cassandra, Coroebus (who gave his life in the Trojan war when he tried to protect her!) came from there! What is even more interesting? His father, King Mygdon of Phrygia … fought in his young adulthood on the same side as Priam of Troy in war! Wow, they like friends, this is a very cool information right??? I think Troy would like to keep relationships with city of Phygia by sending their sons to school would be very interesting.

And again, for two reasons. First of all, Coroebus would fall in love with kind & intelligent Cassandra from the stories which her brother told and not only in her appearance as other suitcases did. And besides, I want relationship of ths poor twins to be very complicated. Like, they love each other but Helenus suddenly returns, his beloved sister behaves as if she lost her mind and there is a war in front of their house because a stranger who turned out to be their lost brother (Paris) kidnapped someone's wife (Helen).

Additionally, I have an idea that Apollo has cursed Cassandra with "no one who NOW is behind the walls of city will believe you in terrible visions that I will send." What does it mean? This means that the curse that was imposed on her is still here … but Helenus (and even Coroebus) are not under its effect, because they were no longer in Troy at a time when Cassandra refused love to God. This means that Helenus may not believe his twin of his own will :)

At my arts - twins with colors (ugh, why is he so like my Odysseus? I need to do something with old king tho), a scene from the Iliad in which after the death of Paris, Helen is forced to marry his brother … and Helenus for some reason also fought for her hand? Boy, you were supposed to be the intelligent one. And next is the scene in which Cass is after vision, all scratched and in her own blood/ Helenus wants to disintegrate the wounds so he pours some vinegar onto a cloth. He has no idea what happened to his sister, he has no idea what to believe but he really wants to help her. And the last art, i.e. young twins who interested wrong God. BTW … I used yellow and blue for them because they are complementary colors. Cass has yellow, which unfortunately shows her attracting to Apollo but she wears some blue. Helenus has blue besides because it is a color that will show coldness and distance. He publicly does not take Cassandra seriously but privately apologizes for it and says that he is too weak for standing on her side. He doesn't lie, she believes him and understands it too, but this hurts a lot. In general, it is difficult to love someone when divine forces on the road and Helenus did not pass the test. Coroebus do! But we'll talk about him later. For now I will say that he and Hel do not have a good relationship.

#epic#epic the musical#cassandra au#cassandra of troy#kassandra#kassandra of troy#cassandra#helenus#helenus of troy#cassandra and helenus#helenus and cassandra#Coroebus#coroebus of phrygia#priam#hecuba#firinnie#my thoughts#art#my art#trojan war#the iliad#troy#ilion#Coroebus and cassandra#cassandra and Coroebus

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

greek icons - king midas. king of phrygia. golden touch. blessed by dionysus

‘your midas touch on the chevy door, november flush and your flannel cure’ - taylor swift

#xoxochb#percy jackon and the olympians#pjo series#pjo fandom#percy jackson#pjo#percy series#pjo hoo toa#pjo spoilers#greek myth aesthetic#greek mythology#king midas

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

[All excerpts used are from E.P Coleridge's translation]

Okay, I've talked about the romantic dynamic between Iphigenia and Achilles in a less popular tradition (compared to the tradition that's all farce and nothing but deception), but I also like their dynamic in Iphigenia in Aulis because I feel like it, to some extent, has to do with the way Iphigenia is both humanized and objectified by the context that's imposed on her. I usually see their relationship being used to make a point about Achilles, but I think it's possible to make a point about Iphigenia as well.

Achilles is willing to cooperate with Clytemnestra from the beginning after they both discover Agamemnon's plan, and he doesn't need to be convinced to help. But they don't have the same goal, not really. Clytemnestra wants to save Iphigenia, but Achilles doesn't seem to be thinking about Iphigenia specifically. In fact, he seems to be thinking about his honor. When Clytemnestra begs Achilles to help her, he responds:

Achilles My proud spirit is stirred to range aloft, butI have learned to grieve in misfortune [920] and rejoice in high prosperity with equal moderation. For these are the men who can count on ordering all their life rightly by wisdom's rules. True, there are cases where it is pleasant not to be too wise, [925] but there are others, where some store of wisdom helps. Brought up in godly Chiron's halls myself, I learned to keep a single heart; and provided the Atridae lead well, I will obey them; but when they cease from that, no more will I obey; [930] no, but here and in Troy I will show the freedom of my nature, and, as far as in me lies, do honor to Ares with my spear. You, lady, who have suffered so cruelly from your nearest and dearest, I will, by every effort in a young man's power, set right, investing you with that amount of pity [935] and never shall your daughter, after being once called my bride, die by her father's hand; for I will not lend myself to your husband's subtle tricks; no! for it will be my name that kills your child, although it does not wield the sword. Your own husband [940] is the actual cause, but I shall no longer be guiltless, if, because of me and my marriage, this maiden perishes, she that has suffered past endurance and been the victim of affronts most strangely undeserved.

So am I made the poorest wretch in Argos; [945] I a thing of nothing, and Menelaus counting for a man! No son of Peleus I, but the issue of a vengeful fiend, if my name shall serve your husband for the murder. No! by Nereus, who begot my mother Thetis, in his home amid the flowing waves, [950] never shall king Agamemnon touch your daughter, no! not even to the laying of a finger-tip upon her robe; or Sipylus, that frontier town of barbarism, the cradle of those chieftains' line, will be henceforth a city indeed, while Phthia's name will nowhere find mention. [955] Calchas, the seer, shall rue beginning the sacrifice with his barley-meal and lustral water. Why, what is a seer? A man who with luck tells the truth sometimes, with frequent falsehoods, but when his luck deserts him, collapses then and there. It is not to secure a bride that I have spoken thus—there are maids unnumbered [960] eager to have my love—no! but king Agamemnon has put an insult on me; he should have asked my leave to use my name as a means to catch the child, for it was I chiefly who induced Clytemnestra to betroth her daughter to me; [965] I would had yielded this to Hellas, if that was where our going to Ilium broke down; I would never have refused to further my fellow soldiers' common interest. But as it is, I am as nothing in the eyes of those chieftains, and little they care of treating me well or ill. [970] My sword shall soon know if any one is to snatch your daughter from me, for then will I make it reek with the bloody stains of slaughter, before it reach Phrygia. Calm yourself then; as a god in his might I appeared to you, without being so, but such will I show myself for all that.

That is, Achilles openly admits that if Agamemnon had asked to use his name and justified it as necessary for Troy to be taken, Achilles would have accepted. He would have been willing to deceive Iphigenia, an innocent maiden who was eager to marry, if it meant that he would go to Troy to achieve his beloved glory. He himself makes this clear in “he should have asked my leave to use my name as a means to catch the child, for it was I chiefly who induced Clytemnestra to betroth her daughter to me; [965] I would have yielded this to Hellas, if that was where our going to Ilium broke down; I would never have refused to further my fellow soldiers' common interest”. Achilles, in literature, is usually presented more as strength than cunning and, in fact, tends to oppose deception. But the Achilles of Iphigenia in Aulis, when he says that he would collaborate with this cunning plan, immediately argues that the reason is that he would be motivated by “my fellow soldiers' common interest”. Sure, one might think that Achilles doesn't seem like someone who would do something he doesn't want to do for the sake of his soldiers, but this Achilles is young and inexperienced (see how he interacts with Clytemnestra in their first meeting, he is even shy to be alone with a woman). He's not the same Achilles we see in The Iliad, an adult in the last year of the war. The Iliadic Achilles is already established in the army, the Euripidean one isn’t and he needs to secure his position. I can believe that he would actively participate in this deception.

Achilles isn’t helping Clytemnestra because he would never sacrifice an innocent maiden, he is helping Clytemnestra because he has been insulted —“Agamemnon has put an insult on me.” It isn’t the aggression directed at Iphigenia, but the insult directed at him that angers him deeply. Because by disregarding Achilles’ consent to the plan, he feels as if he is ignored, as if he doesn’t matter enough to be considered, as if he has no identity at all: “So am I made the poorest wretch in Argos; [945] I a thing of nothing, and Menelaus counting for a man! No son of Peleus I, but the issue of a vengeful fiend, if my name shall serve your husband for the murder.” And if there is one thing that Achilles values, it’s his identity. For it is this identity that brings with it his glorious and famous lineage (so much so that, when denying his identity to himself, he says “no son of Peleus”), that makes him the infamous son of Thetis the Nereid, that makes him a prince, that makes him a descendant of the mighty Zeus, that makes him a pupil of the wise Chiron, that makes him the prophesied warrior. The honor that he values so much is linked to his identity as a person because the achievement of this honor has as its reward the immortalization of Achilles in future generations. A name — one of the strongest identity characteristics — that will be remembered, as well as what comes with it. And what does Agamemnon do when he uses it like this, without considering how he might feel? He transforms Achilles into a tool, a passive object.

But while Achilles is offended by the idea of him as a person being disregarded and instead used as a tool, he unconsciously does something similar with Iphigenia. To him, she initially has no identity. Throughout the play, before the end, several characters interact with each other, but Achilles and Iphigenia aren’t one of these pairs. He hasn’t spoken to her, he doesn’t know her. To him, there is no “Iphigenia the person” there is “Iphigenia the tool in the plan”. He only knows her in the capacity of a passive object, and in this imagery there isn’t enough in Iphigenia to be a motivator for Achilles any more than his wounded honor is. Even when he talks about the sacrifice, Achilles talks about how it affects him “never shall your daughter, after being once called my bride, die by her father's hand; for I will not lend myself to your husband's subtle tricks; no! for it will be my name that kills your child, although it does not wield the sword”. Even when it comes to Iphigenia, Achilles seems to be motivated primarily by himself. Iphigenia is almost like a footnote, just a motivating object of his narrative.

In contrast, when Iphigenia refers to Achilles, she is seeing him as a person. More specifically, she sees him as a potential fiancé, even after she knows about the deception, so much so that she refers to the plan as “our marriage.” One could perhaps say that Iphigenia also doesn’t attribute an identity to him, since she sees him only in the role of this scenario (i.e., fiancé) in the same way that Achilles saw her as “bride”, but I don’t think that’s the case. She is embarrassed by the possibility of seeing Achilles, and why would she be embarrassed if it weren’t because she fears his reaction? And for Iphigenia to fear Achilles’ reaction to the discovery that Iphigenia genuinely thought they were going to get married is because she considered him enough of a person to assume that he might have conflicting feelings about the situation. Iphigenia could have just thought “he was deceived too” and that was that, but implicitly she also thought about how the deception would affect him:

Iphigenia calling into the tent. [1340] Open the tent-door to me, servants, that I may hide myself Clytemnestra Why seek to escape, my child? Iphigenia I am ashamed to face Achilles. Clytemnestra But why? Iphigenia The luckless ending to our marriage causes me to feel abashed.

At the end of the play, however, Iphigenia subverts the passive position imposed upon her. She accepts being sacrificed and, in a way, does so in an attempt to regain her agency. Rather than it being something that was done to her, it’s something that she did. Speaking about her decision, she says:

Iphigenia Mother, hear me while I speak, for I see that you are angry with your husband [1370] to no purpose; it is hard for us to persist in impossibilities. Our thanks are due to this stranger for his ready help; but you must also see to it that he is not reproached by the army, leaving us no better off and himself involved in trouble. Listen, mother; hear what thoughts have passed across my mind. [1375] I am resolved to die; and this I want to do with honor, dismissing from me what is mean. Towards this now, mother turn your thoughts, and with me weigh how well I speak; to me the whole of mighty Hellas looks; on me the passage over the sea depends; on me the sack of Troy; [1380] and in my power it lies to check henceforth barbarian raids on happy Hellas, if ever in the days to come they seek to seize her women, when once they have atoned by death for the violation of Helen's marriage by Paris. All this deliverance will my death insure, and my fame for setting Hellas free will be a happy one. [1385] Besides, I have no right at all to cling too fondly to my life; for you did not bear me for myself alone, but as a public blessing to all Hellas. What! shall countless warriors, armed with shields, those myriads sitting at the oar, find courage to attack the foe and die for Hellas, because their fatherland is wronged, [1390] and my one life prevent all this? What kind of justice is that? could I find a word in answer? Now let us turn to that other point. It is not right that this man should enter into battle with all Argos or be slain for a woman's sake. Better a single man should see the light than ten thousand women. [1395] If Artemis has decided to take my body, am I, a mortal, to thwart the goddess? no, that is impossible. I give my body to Hellas; sacrifice it and make an utter end of Troy. This is my enduring monument; marriage, motherhood, and fame—all these is it to me. [1400] And it is right, mother, that Hellenes should rule barbarians, but not barbarians Hellenes, those being slaves, while these are free.

So Iphigenia is actively trying to gain an active role — I am resolved to die; and this I want to do with honor, dismissing from me what is mean“. She doesn’t want to be Iphigenia, the object, she wants to be Iphigenia, a person with an identity. In the same way that soldiers are motivated to fight out of pride in their Greek identity, Iphigenia is motivated to sacrifice herself out of pride in her Greek identity — “and my fame for setting Hellas free will be a happy one“. Not only that, but her action is motivated by glory to some extent, in a similar way to how Achilles himself is motivated — “I give my body to Hellas; sacrifice it and make an utter end of Troy. This is my enduring monument; marriage, motherhood, and fame—all these is it to me“. In the same way that Achilles will have his identity immortalized, so will Iphigenia, and she knows this when she says “to me the whole of mighty Hellas looks; on me the passage over the sea depends; on me the sack of Troy”. By equating her voluntary sacrifice with the sacrifice of soldiers who are willing to die in the field, Iphigenia regains her autonomy by getting closer to their imaginary. Indirectly, Iphigenia secures her identity in a way that makes her close to Achilles, since, after all, he also accepted death.

And it’s in this identification that Achilles begins to see that Iphigenia isn’t just someone he needs to protect, but someone who has desires of her own. Desires that he admires, in fact. He didn’t admire her before because, before, Achilles didn’t know her…but now that he feels he knows her, he thinks she is worthy of it. Iphigenia, then, takes on a humanized role in his mind:

Achilles Daughter of Agamemnon! some god was bent [1405] on blessing me, if I could have won you for my wife. In you I consider Hellas happy, and you in Hellas; for this that you have said is good and worthy of your fatherland; since you, abandonIng a strife with heavenly powers, which are too strong for you, have fairly weighed advantages and needs. [1410] But now that I have looked into your noble nature, I feel still more a fond desire to win you for my bride. Look to it; for I want to serve you and receive you in my halls; and, Thetis be my witness, how I grieve to think I shall not save your life by doing battle with the Danaids. [1415] Reflect, I say; a dreadful ill is death. Iphigenia This I say, without regard to anyone. Enough that the daughter of Tyndareus is causing wars and bloodshed by her beauty; then be not slain yourself, stranger, nor seek to slay another on my account; [1420] but let me, if I can, save Hellas. Achilles Heroic spirit! I can say no more to this, since you are so minded; for yours is a noble resolve; why should not one speak the truth? Yet I will speak, for you will perhaps change your mind; [1425] [that you may know then what my offer is,] I will go and place these arms of mine near the altar, resolved not to permit your death but to prevent; for brave as you are at sight of the knife held at your throat, you will soon avail yourself of what I said. [1430] So I will not let you perish through any thoughtlessness of yours, but will go to the goddess with these arms and await your arrival there. Exit Achilles.

Achilles describes her as someone who has a “noble nature” and a “heroic spirit,” thus acknowledging Iphigenia’s autonomy. For Achilles, Iphigenia is “noble” and “heroic” because she chooses to sacrifice herself for the sake of the Greeks, something that requires courage from her, and if there is anything Achilles admires, it’s this. She takes an action worthy of recognition. Iphigenia is no longer passive, she is active, and Achilles’ attitude changes to match. Throughout the play, whenever he talks about saving Iphigenia, he negotiates this with Clytemnestra. Before Iphigenia declares that she will be sacrificed, Achilles is actually talking to Clytemnestra and in fact doesn’t even address Iphigenia directly, even though she is there. After her declaration, however, even though Clytemnestra was present and disapproved of Iphigenia's thinking, Achilles addresses Iphigenia (and not Clytemnestra) directly, and although he tries to convince her to give up (claiming that he would try to protect her), he still respects her decision. In fact, he puts the decision in her hands by saying that he will wait for Iphigenia to decide whether or not she wants him to intervene. Thus, Achilles acknowledges Iphigenia as not only someone with an identity, but someone with desires that he cannot override [note: I obviously don’t think that Clytemnestra's disapproval of this is the same as her overriding Iphigenia's desires. Since Achilles isn’t intimate with Iphigenia, it’s certainly much easier for him to accept her decision to die than it is for Clytemnestra, the mother who loves her immensely. But Clytemnestra's taking revenge, however, was overriding what Iphigenia would want].

Of course, one could argue that Achilles accepts Iphigenia's decision because her being sacrificed is to his advantage, as it will allow him to go to Troy. But I disagree. After all, he literally offers to try to prevent this, if Iphigenia so desires. He is willing to go against the will of a goddess, Artemis, and the entire army (as Achilles makes it clear that they tried to stone him for speaking in favor of Clytemnestra and Iphigenia) if Iphigenia wants, and indirectly, he is willing to delay his achievement of glory (since the sacrifice is necessary for him to go to Troy). In fact, Achilles explicitly states that he has come to be seen as someone who is enslaved by marriage. In other words, his reputation has been damaged and he has been viewed in a pejorative manner, but that still doesn’t stop him from offering Iphigenia the option of rebelling against the will of the majority:

Clytemnestra In danger of what, stranger?. Achilles [1350] Of being stoned. Clytemnestra Surely not for trying to save my daughter? Achilles The very reason. Clytemnestra Who would have dared to lay a finger on you? Achilles All the men of Hellas. Clytemnestra Were not your Myrmidon warriors at your side? Achilles They were the first who turned against me. Clytemnestra My child! we are lost, it seems. Achilles They taunted me as the man whom marriage had enslaved. Clytemnestra And what did you answer them? Achilles [1355] Not to kill the one I meant to wed— Clytemnestra Justly so. Achilles The wife her father promised me. Clytemnestra Yes, and sent to fetch from Argos. Achilles But I was overcome by clamorous cries. Clytemnestra Truly the mob is a dire mischief. Achilles But I will help you for all that. Clytemnestra Will you really fight them single-handed? Achilles Do you see these warriors here, carrying my arms? Clytemnestra Bless you for your kind intent! Achilles [1360] Well, I shall be blessed.

Even Achilles’ marriage proposal is different. Previously, he had constantly thought of Iphigenia as a “bride” and had taken the marriage for granted if he could handle the situation. And since Achilles hadn’t even met Iphigenia at the time, his motivation for the marriage wasn’t her per se, but rather to reverse the plan into which he had been unwillingly included. And how can a false marriage be reversed if not by making it genuine? In a way, marrying Iphigenia would also be placing himself as responsible for her, in the ancient view of husbands as responsible for their wives. In this sense, Iphigenia was once again passive. But after her declaration, Achilles, instead of taking the marriage for granted, proposes to her. He leaves the decision to marry Iphigenia up to her—“Reflect, I say; a dreadful ill is death”— and if she doesn’t want it, he will accept. And now he desires Iphigenia as his wife in a genuine way because he recognized in her someone with an admirable personality— “But now that I have looked into your noble nature, I feel still more a fond desire to win you for my bride”. Achilles no longer wants “Iphigenia, a passive object” that he needs to protect if he wants to protect his honor, he wants “Iphigenia, a person with an identity and an active one” because he thinks that having a wife like her would be a blessing — “some god was bent [1405] on blessing me, if I could have won you for my wife”. Achilles even talks about a possible marriage as he serves her in “Look to it; for I want to serve you and receive you in my halls”. She is no longer a symbol of his wounded honor, she is a symbol of glory and if there is one thing young Achilles desires it is glory. She's not a part of the scenery, she's a character.

But Iphigenia chooses to sacrifice herself and Achilles clearly doesn’t contradict her on, as a Messenger actually makes it quite clear that Achilles had an active role in the sacrifice as he spread the water and referred directly to Artemis:

Messenger [1540] Dear mistress, you shall learn all clearly; from the outset will I tell it, unless my memory fails me somewhat and confuses my tongue in its account. As soon as we reached the grove of Artemis, the child of Zeus, and the flowery meadows, [1545] where the Achaean troops were gathered, bringing your daughter with us, at once the Argive army began assembling; but when king Agamemnon saw the maiden on her way to the grove to be sacrificed, he gave one groan, and, turning away his face, let the tears burst [1550] from his eyes, as he held his robe before them. But the maid, standing close by her father, spoke thus: “O my father, here I am; willingly I offer my body for my country and all Hellas, [1555] that you may lead me to the altar of the goddess and sacrifice me, since this is Heaven's ordinance. May good luck be yours for any help that I afford! and may you obtain the victor's gift and come again to the land of your fathers. So then let none of the Argives lay hands on me, [1560] for I will bravely yield my neck without a word.” She spoke; and each man marvelled, as he heard the maiden's brave speech. But in the midst Talthybius stood up, for this was his duty, and bade the army refrain from word or deed; [1565] and Calchas, the seer, drawing a sharp sword from its scabbard laid it in a basket of beaten gold, and crowned the maiden's head. Then the son of Peleus, taking the basket and with it lustral water in his hand, ran round the altar of the goddess [1570] uttering these words: “O Artemis, you child of Zeus, slayer of wild beasts, that wheel your dazzling light amid the gloom, accept this sacrifice which we, the army of the Achaeans and Agamemnon with us, offer to you, pure blood from a beautiful maiden's neck; [1575] and grant us safe sailing for our ships and the sack of Troy's towers by our spears.” Meanwhile the sons of Atreus and all the army stood looking on the ground.

[But the priest, seizing his knife, offered up a prayer and was closely scanning the maiden's throat to see where he should strike. [1580] It was no slight sorrow filled my heart, as I stood by with bowed head; when there was a sudden miracle! Each one of us distinctly heard the sound of a blow, but none saw the spot where the maiden vanished. The priest cried out, and all the army took up the cry [1585] at the sight of a marvel all unlooked for, due to some god's agency, and passing all belief, although it was seen; for there upon the ground lay a deer of immense size, magnificent to see, gasping out her life, with whose blood the altar of the goddess was thoroughly bedewed. [1590] Then spoke Calchas thus—his joy you can imagine—“You captains of this leagued Achaean army, do you see this victim, which the goddess has set before her altar, a mountain-roaming deer? This is more welcome to her by far than the maid, [1595] that she may not defile her altar by shedding noble blood. Gladlyshe has accepted it, and is granting us a prosperous voyage for our attack on Ilium. Therefore take heart, sailors, each man of you, and away to your ships, for today [1600] we must leave the hollow bays of Aulis and cross the Aegean main.” Then, when the sacrifice was wholly burnt to ashes in the blazing flame, he offered such prayers as were fitting, that the army might win return; but Agamemnon sends me to tell you this, [1605] and say what heaven-sent luck is his, and how he has secured undying fame throughout the length of Hellas. Now I was there myself and speak as an eyewitness; without a doubt your child flew away to the gods. A truce then to your sorrowing, and cease to be angry with your husband; [1610] for the gods' ways with man are not what we expect, and those whom they love, they keep safe; yes, for this day has seen your daughter dead and living.

Thus, I genuinely think that Achilles' change in thinking in relation to Iphigenia follows her characterization in the narrative, which changes from passive to active, from a narrative motif to a structured character. This post is, of course, purely my own interpretation, but I feel like Iphigenia is rather unfortunately ignored among the interactions/relationships Achilles has and I don't understand why. I think it's important! Not only is Iphigenia important to Achilles' character, but Achilles is also a narrative element in Iphigenia's character.

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Atalanta#8 "Aphrodites Revenge"

The marriage between Hippomenes and Atalanta proves strong and true, and Hippomenes doesn’t stifle his wife’s wild independence. On the contrary, he loves her the more for it. Many days they hunt together in the forests, and before long they have a son, Parthenopaeus. However, Hippomenes made an unforgivable mistake. He forgot to honor and sacrifice to Aphrodite for helping him win the foot race. The Olympians do not forget such things easily, and the goddess plans her revenge. One day the pair rest inside a cave dedicated to the mother goddess Cybele, where Aphrodite bewitches the two with lust, and they lay together within site of the gods. Furious at the blasphemous act, Cybele turns the lovers to lions, and put them under the harnesses of the Goddesses chariot.

Atalanta and Hippomenes son, Parthenopaeus, has his own epic life and story, as he goes on to be one of the captains in “The Seven Against Thebes” play. The third in a trilogy by “the father of Greek tragedy”, Aeschylus, the play concerns the two sons of King Oedipus of Thebes, Eteocles, who refuses to relinquish the throne, and Polynices, the other son who leads a revolt army led by seven Argive (from city-state of Argos) captains.

Cybele, a mother goddess of fertility, motherhood, and wilds, has her roots in Anatolia (Turkey), also knows as Asia Minor, in the kingdom of Phrygia. Using the title of Meter Theon, or “Mother of the gods,” the Greek equivalent would be Rhea. The goddess was born a hermaphrodite, but the other gods, fearing this duality, cut of her penis and discarded it. Later, when her mortal lover, Attis, spurns her, she drives him crazy and he amputates his penis and bleeds to death at the base of a pine tree. Thus, Cybele’s cult was run by transgender eunuch priests; the Galli. The orgiastic rites of the cult of Cybele share similarities with the cult of Dionysus. Apparently the priests and other followers, in honor of Cybeles castration, would work themselves into a frenzy, and mutilate and bleed themselves upon violets (representing Attis blood) adorned on a sacred pine tree.

Like this art? It will be in my illustrated book with over 130 other full page illustrations coming in Aug/Sept to kickstarter. to get unseen free hi-hes art subscribe to my email newsletter

Follow my backerkit kickstarter notification page.

Thank you for supporting independent artists! 🤘❤️🏛😁

#aphrodite#Atalanta#Hippomenes#Parthenopaeus#greekmythology#greekgods#pjo#mythology#classics#classicscommunity#myths#ancientgreece

73 notes

·

View notes

Text

Zagreus Sabazius

Important reminder. Everything I write about here is only indirectly connected by distant assumptions and rare crossings and absolutely should not be considered the immutable truth. As someone whose patron is Zagreus, I write about my findings and assumptions, but I am also totally possibly to be mistaken and see what I want to see myself. Take everything with a grain of salt.

We have already once looked at the Greek sources with the story of Zagreus. But beyond the rare surviving Greek sources, we will always have something else. Why is Zagreus sometimes mentioned with the epithet “Sabazius”? What does this epithet mean? What are Zagreus' powers? And why, after all, is he and Gaia called “highest of the all gods” in the Alcmeonis?

Welcome to my deep dive on one of the most mysterious theoi — Zagreus Sabazius.

So, later Greek writers, like Strabo in the first century CE, linked Sabazios with Zagreus. But who is Sabazios and what does it mean?

Sabazius comes from a common root with Sanskrit sabhâdj, honored, and with Greek σέβειν, to honor. It's also may be connected with the Indo-European *swo-, meaning "[his] own," and with the idea of freedom.

Sabazios is a deity originating in Asia Minor. He is the chief sky god of the Phrygians and Thracians. Sabazios gained prominence across the Roman Empire, particularly favored in the Central Balkans due to Thracian influence. On some monuments Sabazius is called “master of the cosmos”.

Decree of the organisation of worshippers of Sabazius, 102 BC

It seems likely that the migrating Phrygians brought Sabazios with them when they settled in Anatolia in the early first millennium BCE, and that the god's origins are to be looked for in Macedonia and Thrace. The ancient sanctuary of Perperikon in modern-day Bulgaria, uncovered in 2000, is believed to be that of Sabazios.

Two altars in the sanctuary were used for blood sacrifice.

And as Euripides has already graciously told us, Zagreus was honored as a god of blood, among other things. Sabazius, as a deity, was often associated with sky, thunder, nature, boons, mystery, and blood. One of its most frequent symbols was serpent.

Sabazius' references sometimes included Cybele. She is an Anatolian mother goddess. She is Phrygia's only known goddess, and was probably its national deity. Greek colonists in Asia Minor adopted and adapted her Phrygian cult and spread it to mainland Greece and to the more distant western Greek colonies around the 6th century BC.

In Greece, Cybele met with a mixed reception. She became partially assimilated to aspects of the Earth-goddess Gaia, of her possibly Minoan equivalent Rhea, and of the harvest–mother goddess Demeter.

And now everything suddenly made sense. Why are Gaia and Zagreus named the highest of all the gods in Alcmeonis? Because they always have been.

In her transition to Greece, Cybele, Phrygia's only known goddess, was named Gaia (which honestly makes much more sense to me than associating her with Rhea or Demeter). And Zagreus? And Zagreus remained Zagreus.

Gaia Cybele and Zagreus Sabazius, Mother Earth and Sky King, the highest gods of the Phrygians and Thracians, who later also made their way to Greece.

But unfortunately, no individual direct myths about King Sabazius have survived either.

But there was also one thing that persisted and always baffled me.

In my personal experience with Zagreus, his signature weapon has always been moonblades to me. And I always wondered why. What does Zagreus have to do with the moon? Why is it always an integral part of his power and history in my experience?

Well, now I know the answer.

At one point Sabazius merged with the Asia Minor and Syrian moon deity, Mēn. Mēn was a lunar god worshipped in the western interior parts of Anatolia. He is attested in various localized variants, such as Mēn Askaenos in Antioch in Pisidia, or Mēn Pharnakou at Ameria in Pontus.

Bust of Mēn in Museum of Anatolian Civilizations

In the Kingdom of Pontus, there was a temple estate dedicated to Mēn Pharnakou and Selene at Ameria, near Cabira (Strabo 12.3.31). The temple was probably established by Pharnakes I in the 2nd century BC, apparently in an attempt to counterbalance the influence of the Moon goddess Ma of Comana. The cult of Mēn Pharnakou in Pontus has been traced to the appearance of the star and crescent motif on Pontic coins at the time.

A similar temple estate dedicated to Mēn Askaenos existed in Pisidia, first centered around Anabura and then shifted to the nearby city of Pisidian Antioch after its founding by the Seleucids around 280 BC. The temple estate/sacred sanctuary (ἱερόs) was a theocratic monarchy ruled by the "Priest of Priests," a hereditary title. According to Strabo, this "temple state" that the cult of Mên Askaenos controlled near Pisidian Antioch, persisted until the city was refounded by the Romans in 25 BC, becoming Colonia Caesarea Augusta.

The Augustan History has the Roman emperor Caracalla (r. 198–217) venerate Lunus at Carrhae; this, i.e. a masculine variant of Luna, "Moon", has been taken as a Latinized name for Mēn.

Even though no specific myths have survived about any aspect of Zagreus, it gives us a wealth of information about what Zagreus was and is and the diverse number of domains he holds.

Yes, Zagreus. Zagreus, god of mysteries, blood, flesh, sky, thunder, nature and moon. Zagreus Sabazius, Zagreus Mēn, Zagreus the Winged Serpent Hunter, Zagreus the Scarlet Thunderer, Zagreus the Serpent King. Zagreus Prince of Chthonia, Zagreus King of Sky, Zagreus Highest of All the Gods, Zagreus Master of the Cosmos.

Ζαγρεύς Σαβάζιος

#zagreus#zagreus deity#zagreus sabazius#Zagreus Mēn#Ζαγρεύς#Ζαγρεύς Σ��βάζιος#Ζαγτεύς Μήν#greek mythology#greek gods#hellenic polytheism#hellenism#greek myth#greek pantheon#hellenic gods#theoi#sabazios#Mēn#hellenic deities#helpol#greek history#ancient greek#ancient greece#ancient greek mythology#ancient greek gods#ancient greek religion#ancient history#mythology#as you can see I'm still in dire need of psychiatric help

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fighting the Titans: Ptolemaic Victory over the Galatians

After the Galatians settled in Asia Minor, Northern Phrygia became a popular recruitment area for various competing Hellenistic monarchs. These Celts were known and respected for their military prowess. At the same time, the various kings of the ancient world occasionally waged war against them. These victories were then used in the royal propaganda to portray the monarch as a defender of civilization and liberty against these "barbarians." This perceived liberating role was often celebrated with the title "Soter" ("Savior"). The ambiguous love-hate relationship with the Galatians is clearly demonstrated in Ptolemaic Egypt, particularly during the reign of Ptolemy II.

Ptolemy II Philadelphos recruited some 4,000 Celtic warriors sometime during the 270s BCE. At the time, Ptolemy II was engaged in a conflict with his rebellious stepbrother, Magas, in Cyrenaica to the west. Magas, who became part of the Ptolemaic dynasty through his mother's marriage to Ptolemy I, had established a kingdom centered around the wealthy Greek colony of Cyrene in modern-day Libya. While Ptolemy headed west to address this threat, the Celtic mercenaries rebelled around 274 BCE.

According to Pausanias (1.7.2), the Celts sought to seize control of Egypt while Ptolemy II was preoccupied in the west. However, Ellis Berresford rightly notes that this claim is likely a gross exaggeration; a force of just 4,000 warriors would hardly have entertained such an ambitious plan. Instead, the Celts probably aimed to exploit the king’s absence by plundering Egypt’s numerous wealthy temples and towns before fleeing the country.

Ptolemy II, however, reacted swiftly and drove the rebels to an island near Sebennytos, where, according to Pausanias, they were starved into submission.

This victory was a minor event but quickly became a key element in Ptolemaic propaganda. The members of the Ptolemaic court, as well as the king himself, likely recognized the propaganda value of this triumph. As rival kings legitimized their rule through victories over Celtic tribes, Ptolemy seized the opportunity to join the ranks of these esteemed “liberator” kings.

Coins were issued featuring Galatian shields to commemorate this victory. Additionally, Ptolemy II was famously celebrated as a second Apollo in Kallimachos’ Hymn to Delos. In this work, the Hellenistic court poet recalls Ptolemy II's victory over the Celts in the following manner:

“Yes, and some day afterward a general conflict will come upon us, when the later-born Titans, raising up against the Greeks a barbarian sword and Celtic war, from the farthest west rushing like snow or equal in number to the heavenly bodies when they flock most thickly in the sky.” (transl. Dee Clayman)

Interestingly, Kallimachos describes the Celts as new Titans. The Titans were the older generation of gods who ruled the universe until they were overthrown by the Olympian gods under Zeus' command. If the Celts are the Titans, then the Ptolemaic king and his army are likened to the Olympian gods. This comparison between the Celts and villains from mythical history is not unique to Kallimachos’ poem. Similarly, in Attalid propaganda, parallels are drawn between their war against the Celts and the legendary Gigantomachy, the mythical victory of the Olympian gods over the Giants.

What is the purpose of this victory? It elevates the conflict with the Celts to an entirely new level. Just as the Titanomachy and Gigantomachy were remembered as triumphs of order, justice, and liberty, the subjugation of the Celts is meant to be celebrated as a victory over barbarism and chaos.

This reimagining of the wars against the Celts proved to be a powerful tool for legitimizing the Hellenistic monarchies in the eyes of the Greeks. The Greeks were naturally inclined to view kingship as an illegitimate and un-Greek form of government. Consequently, the kings employed these powerful mythological narratives to portray themselves as essential to the world order and worthy of rule, despite the autocratic nature of their governance. Moreover, if Zeus, a king, was accepted by the Greeks as the ruler of the cosmos, then why should the Hellenistic monarchs not be accepted as legitimate rulers?

In short, Ptolemy’s victory over the Celts, despite its limited scale, provided him with a triumph he could frame as a victory of order over chaos. This sent a powerful message throughout the Hellenic world: he was a god performing godlike deeds. Furthermore, as the Olympian gods were accepted by the Greeks as kings, why shouldn’t the Ptolemaic monarchy be afforded the same respect?

It is hard not to detect the hubris in this Ptolemaic mindset. They were mortals striving to be gods—or so it might seem. To the Ptolemies, there was no such contradiction: they were not merely mortals aspiring to divinity; they were gods. Through the dynastic cult and other forms of propaganda, they blurred the line between the divine realm and the Egyptian monarchy. Narratives emphasizing the kings’ similarities to the gods were widespread throughout the kingdom. For instance, the Ptolemies’ practice of sibling marriage mirrored the relationship between Zeus and Hera, who were also siblings. The story of the Celts aligns seamlessly with this broader propaganda effort, making its use entirely logical.

Olivier Goossens

#ancient history#archaeology#art history#hellenism#ancient greece#classical literature#ancient egypt#egyptology#celtic#celts#ancient celts

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE ASTOR COVEN, LONDON, ENGLAND. Minor Coven.

Depending on which Astor is asked, the story is different. But a grandmother’s tale is the most accurate. Less embroiled with details, more savage in its executions.

There was a Midas, once. He was a king. It’s a Greek myth well known about greed and humility and it’s rooted in Europe, in ancient Phrygia. From there, it’s been tarnished with adventure to better suit its audience. The ending’s different.

When Midas washed his hands in the river Pactolus. He lost his magic. The daughter he’d turned to gold returned to him with new eyes; gold flecked. Dionysus did not warn Midas of the aftereffects of a magic that runs this deep. When he touched Marigold again in a warm embrace. She turned the tables on him.

King Midas, the man with the golden touch. A golden legacy.

Sometime between 650-700BC, Marigold had two children. They inherit Dionysus’ gift. And her story is carved into Midas’ golden statue. He is displayed beside the throne, watching over the legacy he began. The lineage continues, and Midas gets history’s credits. He is the humbled King, blessed by a God, made mortal by his own greed. Marigold had vanished some centuries ago, though some called her Zoe. Immortality was not part of her dangerous touch; she left behind the power in sons and daughters, who passed the power to the next generation. Scholars, Mythics, New Kings, The Age of Gods. Healers, Clerics, Inventors. Magic breeds attention. And, the Gods lose the faith of the people. The church shuns them. Named abominations from a woman out of wedlock. There is the Age of Gold. Where alchemy, blood and magic begin to blend. More powerful machines of iron and steel are when the God-Kings and Queens are hunted for their magic. There is no faith in false idols. And the river Pactolus is used as a weapon to weaken the tight-knit young Gods. Those who survive, flee to the rest of Europe, spread amongst the common folk, there are only a handful that live past thirty. 1746, Leila Pavett, a potioneer ahead of her time marries Matthew Astor, the son of a God. They form the Astor Coven, in old London, operating a store selling wares and cure-all’s. They moonlight as alchemists, attempting rituals that test the boundaries of both science and magic. 1770, Leila is killed in an alchemical accident. She leaves Matthew and their young son behind. Matthew begins to delve into the possibility of endless life, obsessed with the concept of manufacturing a new version of immortality by using alchemy and the power of the Gods. 1810, The Astor Coven is expanded and Matthew’s son, Kyro continues his parent’s work, but he focuses on the wealth that comes from what he is. Kyro Astor begins to found what would eventually become Astorgold Enterprise Ltd.

The passage of time is a ruthless constant. It is unforgiving. It does not wait for any God, or man, not even an Astor. It is why there is a darkness rooted deep within the bloodline. Something beyond Dionysus, and Midas. It is not godlike or mythical. It is human. Monstrously human. Mortality is a curse they cannot purchase, barter with or run from. No Astor lives beyond one lifetime and often, they die early; reaped by their own, or hunted by the desperate and the envious.

It has been Levinon Astor’s entire obsession. A man descended from a God, from a King. Who forged an Empire, united a coven in one of the most magically underbellied cities in the world and developed the modernisms that the Astor’s still live by, now. But an Astor always wants more.

Nobody ever gets to the top, because those beneath him were kind enough to let him bypass freely.

A grandmother passes, and so does a grandfather. It is the way of life. There is a method to an Astor birth, just as there is one for their death. Like any coven, there are rules and rituals; there is a method to the madness, per se. A coven bleeding gold, can afford to be elitist about their circle.

When an Astor is born, they are deemed Gods.

When an Astor dies, they are considered Reaped.

THEY KNOW THEIR WEIGHT.

At the age of twelve, an Astor knows their role in the coven. They know their bloodline and what they are expected to be. Descended from inventors and mythics, they are children of deities that stand tall above all else. They know the power of Rivers. They know the Nile, Isis, Pactolus, Yangtze, Amazon — they understand the cost of Godhood and the mortality of their existence. There is no mistaking an Astor's power, but there is no doubting the River Gods and theirs. On this birthday, they stand among their elders, in the Altın Çember (Circle of Gold) and are bled. A God can be humbled, and that is always the first lesson.

The ribs are seen as the core of the body; a symbolism between an Alchemist and its exploration of the soul, in a scientific manner. It is the seat of magic within oneself. A vessel that can be cracked. An Astor knows this from childhood, as they are sliced open beneath the twelfth rib.

They must know how to heal a God before they are to live as one.

If an Astor is reaped in this ceremony, then they never deserved to be a God. Those who survive and are able to wield their magic to save themselves are left with a golden scar that follows the path beneath their ribcage; a beautiful reminder of endurance and humility.

On their fifteenth birthday, they must drink from the river Pactolus to understand that power demands sacrifice. If an Astor recovers with their powers after a week, they have transcended to a Bloodright God. They have proven their worth. If their magic is too weak upon its return, they are considered Humbled. And Dionysus does not foresee them as righteous or strong enough to hone such a gift.

An Astor understands that they favour the River Isis, for its alchemical properties, and will not challenge the River Pactolus; if an Astor is sunk into Pactolus, their magic will be Purged and they will be a God no longer. If they consume the waters outside of its sacred well, they will suffer its dampened effects: a sickness, a temporary ward against their power. A God will recover, but they must never fall too deep.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Paris and Helen leaving Sparta basically has two main variations (as survived to us), with some minor differences within each, and it basically breaks down like this:

Menelaos present in Sparta, later leaves:

This is the version that seems to be the oldest, and has staying power close to the "end" of our sources. (Not necessarily exhaustive here, just a couple representative sources below.) It's implied in the Iliad by several of Menelaos' lines where he talks of himself as a host (that has been wronged) and "the Trojans [that is, Paris]" being Helen's guest. The Kypria, too, uses this version. Here's from Proclus' summary: "After their intercourse, they load up a great many valuables and sail away by night." While Ovid's Heroides doesn't deal with Helen and Paris leaving Sparta, this setup is clearly what's going on as well, for they are in Sparta and in Helen's letter she mentions Menelaos having left (with her encouraging/assuring him she'll be fine, while acknowledging she should not have done this and rather told him what is going on with Paris). As does Apollodoros' Bibliotheke: [E.3.3] "For nine days he was entertained by Menelaus; but on the tenth day, Menelaus having gone on a journey to Crete to perform the obsequies of his mother's father Catreus, Alexander persuaded Helen to go off with him. And she abandoned Hermione, then nine years old, and putting most of the property on board, she set sail with him by night."

What happens here, too, is we get some idea of how they left Sparta; apparently quite orderly, with a whole baggage train (inanimate and animate belongings included). This was no quick and sexy little hit and run.

Menelaos not present:

This one has some more variants, and they're all late/er sources; most of them post-0, going on into the Medieval era. Dictys of Crete have Paris come to Sparta, but Menelaos is already absent: "Alexander, taking advantage of Menelaus’ absence, committed a very foul crime. Falling desperately in love with Helen, the most beautiful woman in Greece, he carried her off, along with much wealth, and also Aethra and Clymene, being Menelaus’ relatives, attended on Helen.

A report of this crime came to Crete; but rumor, as commonly happens, spread over the island, making what Alexander had done seem worse than it was. People were even saying that King Menelaus’ home had been taken by storm and that his kingdom was conquered." Dracontius have Helen and Paris meet (after Paris is separated from the rest of his party and driven there by storm) on Cyprus, and he then, with her cooperation "abducts her" - when he sees the Cypriot pursuit he basically goes "oh we die here 8(" and Helen has to tell him to apply his feet so they can reach the ship. In Dares of Phrygia Paris and Helen meet not in Sparta, but on Kythira, and have a moment of mutual attraction. Then this happens: "Thus at a given signal they invaded the temple and carried her off – she was not unwilling – along with some other women they captured. The inhabitants of the own, having learned about the abduction of Helen, tried to prevent Alexander from carrying her off. They fought long and hard, but Alexander’s superior forces defeated them. After despoiling the temple and taking as many captives as his ships would hold, he set sail for home." And in Colluthus' Abduction of Helen, much like in Dictys Paris does come to Sparta and Menelaos is absent.

The interesting thing here is that this second set (again, not exhaustive) introduces a much more obvious/straightforward abduction. And yet, even as they do so, several sources still complicate the matter and introduce some element of willingness for Helen. In Dictys, though nothing is said (because the narrator does not know) about what she might have felt about leaving Sparta, in Troy Helen says she wants to stay there (and the narrator confesses to no idea why she prefers to do so). Dracontius has them both in love and condemns them both as adulterous lovers, Helen urging Paris on in her "abduction". Dictys, too, is the only source that brings up the specter of Paris sacking Sparta to get to Helen - only to explicitly disarm this idea and deny that this was the way it happened. Dares, obviously, note that she's "not unwilling" even as this is the most violent version of Paris leaving with Helen that we have.

Dares, too, is the version of Trojan war narratives that got popular in the West. Even after the Iliad was "rediscovered" and translated into Latin for the West, the more "realistic" and "complete" story as told in Dares (and variously retold in new creations in the Medieval times and forwards) was preferred.

I'm pretty sure that Dares is the reason a lot of our Renaissance (and some earlier, too) art of Paris and Helen leaving Sparta/Kythira look like a violent abduction with battle somewhere in there. Because that is what happens in Dares, and thus in all the Medieval retellings based on Dares... and pretty much nowhere else.

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Gordium

Gordium was the capital of ancient Phrygia, modern Yassihüyük. It is situated on the place where the ancient Royal road between Lydia and Assyria/Babylonia crosses the river Sangarius, which flows from central Anatolia to the Black Sea. Remains of the road are still visible. In the ninth century BCE, the city became the capital of the Phrygians, a Thracian tribe that had invaded and settled in Asia. They created a large kingdom that occupied the greater part of Turkey west of the river Halys.

The kings of Phrygia built large tombs near Gordium. These wooden chambers were covered by artificial hills that are usually called tumuli. There are about eighty of them; forty have been investigated by archaeologists, and turn out to cover the period from the eighth to the first century BCE.

In the eighth century, the citadel was fortified and in the next century, the town became very large indeed. A palace was built in the citadel. To the south of it was a lower city, and a large suburb was to be found on the other bank of the Sangarus.

The most famous king of Phrygia was Midas, who is little more than a name to us. However, contemporary Assyrian refer to a Mit-ta-a, king of Muški. If he is identical to the legendary Midas - which is contested - he cooperated with the rulers of Tyana, Karkemiš, Gurgum, and Malida against the Assyrian king Sargon II, but was attacked by a nomadic tribe called Cimmerians. In 710/709, Midas was forced to ask for help from Sargon. This did not prevent the Cimmerian invasion. Another source, the Chronicle of Eusebius, tells us that the legendary Midas died in 695 - he may have committed suicide after a lost battle. There are traces of destruction at Gordium, but they may be older than the attack by the Cimmerians - and, again, it is unclear whether Muški is identical to Phrygia amd Mit-ta-a to Midas.

The "mound of Midas", the greatest tumulus near Gordium, was excavated in 1957. Its diameter is a little short of 300 meters and it is 43 meters high. In the wooden chamber, which measured 5 x 6 meters, a man's corpse was found, and even the contents of his last dinnerr could be reconstructed. The tumulus also contained one of the oldest alphabetic inscriptions outside Phoenicia (c.740 BCE). After half a century of confusion, western Turkey was reunited by the Lydians, whose first great king was Gyges (c.680-c.644). During the reign of one of his successors, Alyattes (c. 600-560), the wall of the citadel was rebuilt, while a massive fortress was built on a hill next to it. From this moment on, Greek ceramics became fashionable: initially from the Ionian cities, later also from Laconia, and especially Athens.

When Lydia was conquered by the Persian king Cyrus the Great and its last king Croesus killed (after 547), a Persian garrison took possession of this fortress. Gordium was now included in the satrapy of Greater Phrygia. Ceramics from this period sometimes imitate Achaemenid silver vessels, while the town appears to have exported textile.

The garrison stayed there until the last months of 334, when the Macedonian commander Parmenion captured the city. During the winter, his king Alexander the Great joined him. (Go here for the famous story about Alexander cutting the Gordian knot in the palace.)

After the troubles following the death of Alexander in 323, Gordium was first ruled by Antigonus, then by the Seleucid kings of Asia, then by the Celts (the remains of their human sacrifices have been found), then by the Attalid rulers of Pergamon, and eventually by the Romans.

It remained one of the most important commercial centers in the region, still producing textiles. However, the size of the city itself diminished. The old center - citadel and lower town - was abandoned after the Roman conquest in 189 BCE; only the western suburbs remained occupied. (From the first until the fourth century CE, part of the citadel was again in use.) Gordium was still in existence in the sixth century, and was probably called Vindia, which suggests that people no longer remembered its Phrygian past.

Continue reading...

45 notes

·

View notes

Note

🌸✨sparkle sparkle! since you get along so well with the tiny reckless version of you, the world thinks it’s time you reconnect with your younger self! all the drama! the heartache! the pettiness! time to go back and re-experience it all! this ✨magic anon✨ curses you to become 20 once again, for five (5) whole asks! enjoy the ride!!✨🌸

"Get along with--Reconnect with my younger self? Oh, Gods--" Midas feels the zap of magic through him, a tingle similar to passing through a Zero Point rift. Before he's even able to yell obscenities at whoever sent this curse, there is a flash of light that eminates from his body, and he's on the ground. No longer quite himself.

With long, dark hair falling over his shoulders and armor that fit just a touch too big, King Midas stands from the ground in a daze.

Or rather, Prince Midas. At the young age of 20, his father had not yet gruesomely passed and named him king.

Although this Midas already has the scar marring his right eye, his lively tan skin is clear of tattoo ink. A difference more substantial than that, his skin remains it's birth-given tone down to his fingertips. He is not yet cursed with Dionysus' golden gift, is yet to lose a daughter, is yet to even have a child.

Prince Midas was hawty. Over confident to a fault with a clumsy, if not somehow still often effective charisma. He was naive, believed the world would be his for the taking as soon as the throne was his.

Not yet married, he was technically betrothed to a woman chosen by his family already. He'd honor the arrangement when his hand was forced, but at this age, he cared little for the obligation. Both men and women in his kingdom tended to fawn over royalty, not to mention ones so beutiful, and who would he be not to indulge in the privileges the gods had granted him?

Prince Midas of Phrygia could do no wrong, the rules hardly applied to him. He took what he wanted, turned his nose up to what he didn't, and there was no authority he bowed to. (That is, besides his father, and the gods at his father's behest.)

Much to his further confusion, and by some strange grace of this curse, his words come in English rather than Greek. Though, with an accent the current King does not have.

"What the hell is going on?!" He looks around with eyes unburdened by decades of sleepless nights. He pats himself down, the clothes on him strange and constricting, "What costume has been put on me?"

Reaching up to his head, he pulls the thorned crown from his hair. It's gilded surface gleams in the light.

'Ah, well this can stay.' He thinks before setting it back on his head.

#midas answers#cursed with youth#fortnite Tumblrverse#fortnite rp#((I am SO excited for this!!!!))#((I was really wanting to make art for this. But if I did that then whoever sent this anonymous would be waiting for weeks probably lmao))#((hopefully I'll have something drawn to post for this before all the asks are used up but can't guarantee it lol))#((Get twinked idiot))#((seriously I cannot wait to mess around with a version of Midas that is SO different than how he is now))#((tracked tag for this will be cursed with youth))

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Musical Contest between Apollon and Marsyas

Marsyas was a Phrygian satyr who found the divine aulos that Athena had discarded. Or in another version, Marsyas is known as the inventor of the aulos. He fell in love with the instrument and eventually mastered it, believing his skills were that of a God.

Marsyas challenged Apollon, who agreed (or in some versions, Apollon challenged Marsyas for his claims of being better than the God). Marsyas would play first using the double-piped aulos, followed by Apollon playing the same piece on a kithara (or lyre, as some debate these were the same instrument in their earlier days), and the two played back and forth captivating their audience.

Some sources say the judges were the Muses, in others it was King Midas of Phrygia. In one version, Marsyas won the first round. To this, Apollon turned his kithara upside down and played the piece. In another version, Apollon sang while playing the piece. And no matter which version you follow, Marsyas was unable to flip his aulos upside down or sing while playing the wind instrument, ending the contest with Apollon as the winner.

As punishment for his hubris and pride by challenging a deity, Apollon had Marsyas tied to a tree and flayed alive, who might have intended for his skin to be turned into a wine flask. The sight of Marsyas was so upsetting that locals, rustic deities, fauns, and his brother satyrs all wept for him, and in doing so they flooded a river that would be named after him.

References

https://meet-the-myths.com/greek-mythology/marsyas-and-apollo/

https://www.theoi.com/Georgikos/SatyrosMarsyas.html

https://www.theoi.com/Text/HyginusFabulae1.html

https://fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk/explore-our-collection/highlights/context/stories-and-histories/apollo-and-marsyas

https://www.thoughtco.com/apollo-and-marsyas-119918

#witch#witchcraft#witches#pagan#paganism#hellenic deities#hellenic pagan#hellenic polytheism#hellenic polythiest#lord apollon#apollon#apollo deity#lord apollo#apollo worship#greek deities#apollo devotee#marsyas#apollon and marsyas#apollo#greek gods#myths#mythos#greek mythos#polytheist#polytheism

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Okay, I know it's common knowledge here that Teucer shares his name with King Teucer, who ruled over the region that would later become known as Trojan territory. That he's named after a figure from Trojan history isn't strange, since his mother, Hesione, was a Trojan princess and Priam's sister. The interesting part is that the Homeric scholia says this:

...you, though a bastard child (καί σε νόθον περ᾿ ἐόντα) When Heracles sacked Troy, he took as prisoner Hesione, the daughter of Laomedon (and sister of Priam), and gave her as a war-prize to Telamon because he had fought with him. Telamon fathered Teucros by her. Because he had been born of a Trojan woman, they called the child “Teúcros,” moving the accent back to create a proper noun. For the Trojans are called Teucroí after one of their rulers, Teucros. The story has been told in more detail by many, including Apollonios the grammatikos in the second book of On Generations.

Translation by R. Scott Smith et al.

In other words, in this version told here by the scholia, Teucroi/Teucrians would be a kind of synonym for Trojans because of King Teucer/Teucros. The scholia even uses the term as a synonym here:

[a bane] unto himself, since he did not know the gods’ decrees ([κακὸν...] οἷ τ᾿ αὐτῷ, ἐπεὶ οὔ τι θεῶν ἐκ θέσφατα ᾔδη) When the Lacedaimonians were overcome by famine, they consulted an oracle about a solution. The god told them to placate the deities of the Teucrians (this is what the people of Troy were called previously). [...]

Translation by R. Scott Smith et al.

The scholia says “this is what the people of Troy were called previously” probably because, in the myth, even the term “Trojan” comes from a king named Tros. Tros was the inspiration for the name Troy, which is why the inhabitants were called Trojans. In the same way, mythology tries to explain the name “Dardanus” with the character Dardanus and the name “Illium” with the character Ilus. The name “Mount Ida” maybe was related to the nymph Idaea, who had Teucer with the river Scamander, or even Idaeus, one of the sons of Dardanus.

Some sources mention characters that are considered eponymous, but I’ll only present Library as an example because it brings all three of them together:

[...] That country was ruled by a king, Teucer, son of the river Scamander and of a nymph Idaea, and the inhabitants of the country were called Teucrians after Teucer. Being welcomed by the king, and having received a share of the land and the king's daughter Batia, he built a city Dardanus, and when Teucer died he called the whole country Dardania. And he had sons born to him, Ilus and Erichthonius, of whom Ilus died childless, and Erichthonius succeeded to the kingdom and marrying Astyoche, daughter of Simoeis, begat Tros. On succeeding to the kingdom, Tros called the country Troy after himself [...] [...] there Ilus built a city and called it Ilium. [...]

Pseudo-Apollodorus’ Library, 3.12.1-3. Translation by J.G. Frazer.

In the case of Mount Ida, here is an example with Idaeus:

[...] Idaeus, the son of Dardanus, with part of the company occupied the mountains which are now called after him the Idaean mountains, and there built a temple to the Mother of the Gods and instituted mysteries and ceremonies which are observed to this day throughout all Phrygia. And Dardanus built a city named after himself in the region now called the Troad; the land was given to him by Teucer, the king, after whom the country was anciently called Teucris.

Dionysus Helicarnassus’ Roman Antiquities. Translation by Earnest Cary and Edward Spelman.

Establishing here the idea that these local names were attributed as homage to these mythological characters, it’s interesting that the scholia says “because he had been born of a Trojan woman, they called the child “Teúcros,” moving the accent back to create a proper noun. For the Trojans are called Teucroí after one of their rulers, Teucros”. The scholia doesn’t say “the name was in honor of the king”, the scholia says that the inspiration was the word itself that designated the Trojan people. In other words, Teucer was basically named after not a specific man, but his mother’s people as a whole, who were once named after that man. And the scholia doesn't say "Hesione named him", the scholia says "they". So this was probably a decision by more than one person. Telamon and Hesione, probably. I can see Hesione naming her son this because she wants to remember her home, after all she's not there because she wants to be (she's a captive), but Telamon? It's interesting that the apparent scholia indicates that Telamon agreed. I doubt he did it out of kindness, Telamon is usually consistently portrayed as a character with a bad temper (for example, see Apollonius Rhodius' Argonautica). Could it be that, in this case, Telamon wanted to sinalize Teucer as a half-Trojan boy? Not out of kindness to Hesione, but as a way of accentuating Teucer as a bastard of foreign blood? After all, he did indeed have favoritism towards Ajax, this is also consistent in the myth (see, for example, how he banished Teucer from Salamis because he blamed him for Ajax's death. In Sophocles' Ajax this element is emphasized). Also, a character called the equivalent of "Trojan" helping to destroy Troy is something… to think about. The possibility that Teucer was named after the people rather than the man makes it all the more interesting.

Anyway, I think this is headcanon. Of course, it seems quite purposeful that he is given a Trojan name as far as the narrative is concerned, but I honestly don't think they were thinking about specific details like Hesione and Telamon's inner motivations for the name when this was written. But I like my new headcanon!

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reference to Alexander the Great, his General, Antigonus, and the Battle of Gabiene.

The "Treasures of the Aegean Sea" tells the saga of a family of Western arcanists whose journey spans thousands of miles and over two millennia. Their ancestors fought alongside a Macedonian God-King (possibly Alexander the Great), shifting their loyalties after his death to the one-eyed general (possibly Antigonus). These war-hardened veterans joined his army after the Battle of Gabiene and formed a powerful but volatile force.

The arcanists within this army were eventually sent east, where they blended into the Sogdian tribes and thrived along the Central Asian trade routes. Over time, they settled near the ancient Hellenistic city of Ai-Khanoum, establishing a small arcanist commune. However, the turbulence of early conflicts eventually scattered them once again, leaving behind only fragments of their story—maps, diaries, epitaphs, and archives that tell the tale of their incredible adventure.

Alexander the Great (356–323 BC), king of Macedon, succeeded his father Philip II at age 20 and embarked on a decade-long military campaign, creating one of the largest empires in history, stretching from Greece to India. Undefeated in battle, he conquered the Achaemenid Persian Empire and expanded Macedonian control across Western and Central Asia, Egypt, and parts of South Asia. After defeating Indian king Porus, Alexander’s army refused to advance further, leading him to turn back. He died in 323 BC in Babylon. His conquests spread Greek culture widely, marking the start of the Hellenistic period. Alexander’s military legacy influenced later leaders and became legendary, inspiring literature across many cultures. source

Antigonus I Monophthalmus aka "Antigonus the One-Eyed"; 382 – 301 BC) was a Macedonian general and a key successor to Alexander the Great. After serving in Alexander's army, he became satrap of Phrygia and later assumed control over large parts of Alexander’s former empire. He declared himself king (basileus) in 306 BC and founded the Antigonid dynasty. Following a series of wars among Alexander’s successors, Antigonus became one of the most powerful Diadochi, ruling over Greece, Asia Minor, and parts of the Near East. However, he was defeated and killed at the Battle of Ipsus in 301 BC, leading to the division of his kingdom. His son Demetrius later took control of Macedonia. source

Gabiene: After the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC, his generals immediately began squabbling over his empire. Soon it degenerated into open warfare, with each general attempting to claim a portion of Alexander's vast kingdom. One of the most talented generals among the Diadochi was Antigonus Monophthalmus (Antigonus the One-eyed), so called because of an eye he lost in a siege. During the early years of warfare between the Successors, he faced Eumenes, a capable general who had already crushed Craterus. The two Diadochi fought a series of actions across Asia Minor, and Persia and Media before finally meeting in what was to be a decisive battle at Gabiene (Greek: Γαβιηνή). source

15 notes

·

View notes

Note

I'm reading The Last King and this meteor strike in Phrygia has floored me and I've got to talk to someone about this!

Rome is in chaos following the Populares/Optimates civil war, their armies are stretched thin trying to take and hold too much territory. Mithridates' Pontics are a massive army with top notch modern Roman training, many of whom are exiled Populares themselves. The Pontics have the initiative, a Roman enemy with mixed feelings about slaying their own, and every probability of destroying the Romans totally, shifting the balance of power in the Med and ending the empire they were to become.