#kikongo

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I kind of want to learn (self teach) a language based on the most spoken language of some of my non-european genetic ancestry regions.

the only language remotely close to something i know would be Vietnamese since I've attempted East Asian languages before, but I'm pretty sure there's a lot of differences between it and Mandarin/Korean/Japanese

#academia#black studyblr#black academia#studyblr#student#langblr#language learning#languages#yoruba#vietnamese#quechua#akan#bambara#kikongo#tamil#choctaw#culture#poc langblr#poc studyblr#poc academia#poc dark academia#let's ignore that i forgot to add benin and togo to the poll..... 😭

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

I have something beautiful to share with you all: give this a listen. What do you think it is?

There's many different versions of this song, just type "Misibamba" on spotify or youtube, and enjoy. It's specifically an AfroArgentinean song, with most of the versions of this song recorded in Buenos Aires. According to african scholars, the song was originally in kikongo, possibly from the Benguela Nation, and it's traditionally sung to call on God (Nzambi Npungu). Some of the words have gone through slight (and not so slight) pronunciation or spelling changes but it's still recognizable for scholars in Angola!

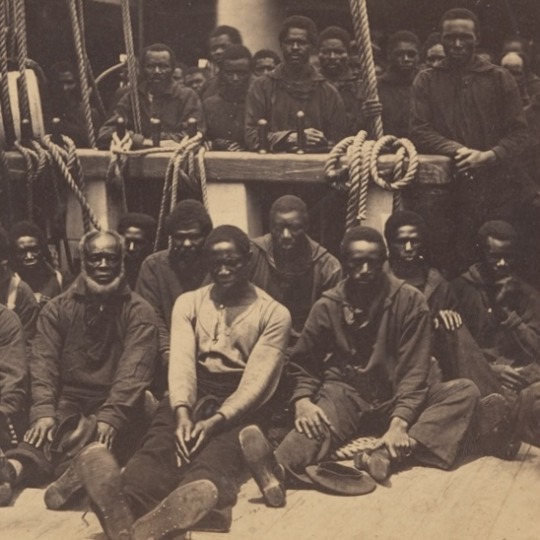

What scholars say about it being originally used to call on God fits our own oral tradition and custom too, it's a religious song. Our elders sing it in times of need, when you need that extra ancestral and divine protection or guidance, and Elders say it was originally sung by our Ancestors in the slave ships as they were crossing the atlantic !!!

And it's not even the only song that remains! there's many other songs in african languages and derived dialects, remembered and sung by afroargentine Elders across the country. After so many years of denial and historical whitewashing, I'm so, so deeply grateful for all the afroargentine and african scholars, and afroargentine collectives and associations, working to preserve our music and dialects, and finally bring them back to the light, to remember and honor our Ancestors.

#Afroargentina#Afroargentinean#Afrolatinos#Afrolatines#Afroargentine#Afroargentines#history#afroargentine history#kikongo#angola#benguela#Nzambi Mpungu#ATRs#ADRs#African Traditional Religions#african diaspora#black argentina#black argentines

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

San Basilio de Palenque or Palenque de San Basilio, often referred to by the locals simply as Palenke, is a Palenque village and corregimiento in the Municipality of Mahates, Bolivar in northern Colombia. Palenque was the first free African town in the Americas, and in 2005 was declared a Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity by UNESCO

Spaniards introduced enslaved Africans in South America through the Magdalena River Valley. Its mouth is close to the important port of Cartagena de Indias where ships full of Africans arrived. Some Africans escaped and set up Palenque de San Basilio, a town close to Cartagena. This community began in 1619, when Domingo Biohó led a group of about 30 runaways into the forests, and defeated attempts to subdue them. Biohó declared himself King Benkos, and his palenque of San Basilio attracted large numbers of runaways to join his community. His Maroons defeated the first expedition sent against them, killing their leader Juan Gómez. The Spanish arrived at terms with Biohó, but later they captured him, accused him of plotting against the Spanish, and had him hanged.

They tried to free all enslaved Africans arriving at Cartagena and were quite successful. Therefore, the Spanish Crown issued a Royal Decree (1691), guaranteeing freedom to the Palenque de San Basilio Africans if they stopped welcoming new escapees. But runaways continued to escape to freedom in San Basilio. In 1696, the colonial authorities subdued another rebellion there, and between 1713-7. Eventually, the Spanish agreed to peace terms with the palenque of San Basilio, and in 1772, this community of maroons was included within the Mahates district, as long they no longer accepted any further runaways

The village of Palenque de San Basilio has a population of about 3,500 inhabitants and is located in the foothills of the Montes de María, southeast of the regional capital, Cartagena. The word "palenque" means "walled city" and the Palenque de San Basilio is only one of many walled communities that were founded by escaped slaves as a refuge in the seventeenth century. Of the many palenques of escaped enslaved Africans that existed previously San Basilio is the only one that survives.Many of the oral and musical traditions have roots in Palenque's African past. Africans were dispatched to Spanish America under the asiento system.

The village of San Basilio is inhabited mainly by Afro-Colombians which are direct descendants of enslaved Africans brought by the Europeans during the Colonization of the Americas and have preserved their ancestral traditions and have developed also their own language; Palenquero. In 2005 the Palenque de San Basilio village was proclaimed Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity by UNESCO.

In the village of Palenque de San Basilio most of its inhabitants are African and still preserve customs and language from their African ancestors. In recent years people of indigenous ancestry have settled at the borders of Palenque, being displaced earlier by the Colombian civil war. The village was established by Benkos Bioho sometime in the 16th century.

One of the first anthropological studies of the inhabitants of Palenque de San Basilio was published by anthropologist Nina de Friedemann and photographer Richard Cross in 1979 entitled Ma Ngombe: guerreros y ganaderos en Palenque.

A Spanish-based creole language known as Palenquero originates in this community. The New York Times reported on October 18, 2007 that the language spoken in Palenque is thought to be the only Spanish-based creole language spoken in Latin America. Being a creole language, its grammar differs substantially from Spanish making the language unintelligible to Spanish speakers. Palenquero was influenced by the Kikongo language of Congo and Angola, and also by Portuguese, the language of the slave traders who brought enslaved Africans to South America in the 17th century. Exact information on the different roots of Palenquero is still lacking, and there are different theories of its origin. In 2007, fewer than half of the community's 3,000 residents still speak Palenquero.

A linguist born in Palenquero is compiling a lexicon for the language and others are assembling a dictionary of Palenquero. The defenders of Palenquero continue working to keep the language alive

#san basilio#palenquero#african#kemetic dreams#afrakan#brownskin#afrakans#africans#brown skin#south america#spanish#colombian#kikongo#congo#angola#latin america

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Kingdom of Kongo and Palo Mayombe: Reflections on an African-American Religion

Abstract

Historical scholarship on Afro-Cuban religions has long recognized that one of its salient characteristics is the union of African (Yoruba) gods with Catholic Saints. But in so doing, it has usually considered the Cuban Catholic church as the source of the saints and the syncretism to be the result of the worshippers hiding worship of the gods behind the saints. This article argues that the source of the saints was more likely to be from Catholics from the Kingdom of Kongo which had been Catholic for 300 years and had made its own form of Christianity in the interim.

Acknowledgements

Research funding for this project was supplied by Boston University Faculty Research Fund and the Hutchins Center of Harvard University. Earlier versions were presented at the Hutchins Center, and the keynote address at ‘Kongo Across the Waters’ in Gainesville, FL. Thanks to Linda Heywood, Matthew Childs, Manuel Barcia, Jane Landers, Carmen Barcia, Jorge Felipe Gonzalez, Thiago Sapede, Marial Iglesias Utset, Aisha Fisher, Dell Hamilton, Grete Viddal and Kyrah Daniels for readings, comments, questions and source material.

[1] Robert Farris Thompson, Flash of the Spirit: African and Afro-American Art and Philosophy (New York: Random House, 1983), pp. 17–8; see also Face of the Gods: Art and Altars of Africa and African America (New York: Prestel, 1993). For Cuba in particular, see David H. Brown, Santería Enthroned: Art, Ritual and Innovation in an Afro-Cuban Religion (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2003), p. 34 (with ample references to earlier visions).

[2] Georges Balandier, Daily Life in the Kingdom of the Kongo (New York: Allen and Unwin, 1968 [French Version, Paris, 1965]) and James Sweet, Recreating Africa: Culture, Kinship and Religion in the African-Portuguese World, 1441–1770 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003).

[3] Ann Hilton, The Kingdom of Kongo (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1984), for the role of the Capuchins in discovering problems with Kongo's Christianity. John Thornton, ‘The Kingdom of Kongo and the Counter-Reformation’, Social Sciences and Missions 26 (2013): 40–58 contextualizes their role and their problems with Kongo's Christianity.

[4] Adrian Hastings, The Church in Africa, 1450–1950 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994); this position is often implicit in the many histories written by clerical historians such as Jean Cuvelier, Louis Jadin, François Bontinck, Teobaldo Filesi, Carlo Toso and Graziano Saccardo, whose work has presented modern editions of the classical work of the Capuchin missionaries, commentaries and at times regional histories, such as Saccardo, Congo e Angola con la storia del missionari Capuccini, Vol. 3 (Venice: Curia Provinciale dei Cappuccini, 1982–1983). For both a position of dependence on missionaries and a recognition of local education, Louis Jadin, ‘Les survivances chrétiennes au Congo au XIXe siècle’, Études d'histoire africaine 1 (1970): 137–85.

[5] It is not mentioned at all in his seminal work, Thompson, Flash of the Spirit in the nearly 100-page section dealing with Kongo and its influence in Vodou, nor in Face of the Gods.

[6] Erwan Dianteill, ‘Kongo à Cuba: Transformations d'une religion africaine', Archives de Sciences Sociales de Religion 117 (2002): 59–80.

[7] Todd Ochoa, Society of the Dead: Quita Manaquita and Palo Praise in Cuba (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2010), pp. 8–10. Wyatt MacGaffey's work, especially Religion and Society in Central Africa: The BaKongo of Lower Zaire (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1986) is a favorite.

[8] Thiago Sapede, Muana Congo, Muana Nzambi a Mpungu: Poder e Catolicismo no reino do Congo pós-restauração (1769–1795) (São Paulo: Alameda, 2014) is the first book length study of Christianity in the later period of Kongo's history.

[9] John Thornton, ‘Afro-Christian Syncretism in the Kingdom of Kongo', Journal of African History 54 (2013): 53–77.

[10] Thornton, ‘Afro-Christian Syncretism'.

[11] Sapede, Muana Congo, pp. 248–57.

[12] Thornton, ‘Afro-Christian Syncretism', for the details of the struggle, but a perspective that sees the Capuchin mission as central to Kongo Christianity, see Saccardo, Congo e Angola.

[13] John Thornton, The Kongolese Saint Anthony: D Beatriz Kimpa Vita and the Antonian Movement, 1684–1706 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998).

[14] Rafael Castello de Vide, ‘Viagem ao Congo’, Academia das Cienças de Lisboa, MS Vermelho 396, pp. 32–4, 183–5 (transcription by Arlindo Carreira, 2007 at http://www.arlindo-correia.com/161007.html) which marks the pagination of the original MS.

[15] Castello de Vide, ‘Viagem ao Congo', pp. 110–4.

[16] Raimondo da Dicomano, ‘Informazione' (1798), pp. 1–2. The text exists in both the Italian original and a Portuguese translation made at the same time. For an edition of both, see the transcription of Arlindo Carreira, 2010 (http://www.arlindo-correia.com/121208.html).

[17] ‘Il Stato in cui si trova il Regno di Congo', September 22, 1820, in Teobaldo Filesi, ‘L'epilogo della ‘Missio Antiqua’ dei cappuccini nel regno de Congo (1800–1835)’, Euntes Docete 23 (1970), pp. 433–4.

[18] Among the first was Domingos Pereira da Silva Sardinha in 1854, who, according to King Henrique II of Kongo, had performed his duties of administering the sacraments with ‘all the necessary prudence', Henrique II to Vicar General of Angola, December 14, 1855, Boletim Oficial de Angola, 540 (1856).

[19] Biblioteca d'Ajuda, Lisbon, Códice 54/XIII/32 n° 9, Francisco de Salles Gusmão to the King, October 27, 1856.

[20] Castello de Vide, ‘Viagem ao Congo’, pp. 110–4.

[21] da Dicomano, ‘Informazione', pp. 1–7 (of manuscript).

[22] Castello de Vide, ‘Viagem', pp. 39, 69, 276.

[23] Castello de Vide, ‘Viagen', p. 217 (thanks to Thiago Sapede for this reference).

[24] Castello de Vide, ‘Viagem’, pp. 32–4, 1835.

[25] For a thorough study of these religious artefacts and their meaning, see Cécile Fromont, The Art of Conversion: Christian Visual Culture in the Kingdom of Kongo (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2014).

[26] Castello de Vide, ‘Viagem', p. 78.

[27] APF Congo 5, fols. 298–298v (Rosario dal Parco) ‘Informazione 1760' A French translation is found in Louis Jadin, ‘Aperçu de la situation du Congo, et rite d’élection des rois en 1775, d'après le P. Cherubino da Savona, missionaire de 1759 à 1774', Bulletin de l'Institut Historique Belge de Rome 35 (1963): 347–419 (marking foliation of original MS).

[28] Castello de Vide, ‘Viagem', pp. 180–4.

[29] Castello de Vide, ‘Viagem', p. 53.

[30] Castello de Vide, ‘Viagem', pp. 63–4; see also 87 for another noble as Captain of Church; 136 crowds at Mapinda.

[31] da Dicomano, ‘Informazione', pp. 1–7.

[32] Castello de Vide, ‘Viagem', p. 196.

[33] Bernard Clist et alia, ‘The Elusive Archeology of Kongo Urbanism, the Case of Kindoki, Mbanza Nsundi (Lower Congo, DRC)’, African Archaeological Review 32 (2014) 369–412 and Charlotte Verhaeghe, ‘Funeraire rituelen en het Kongo Konigrijk: De betekenis van de schelp- en glaskralen en de begraafplaats van Kindoki, Mbanza Nsundi, Neder-Kongo' (MA thesis, University of Ghent, 2014), pp. 44–50.

[34] ‘Il Stato in cui si trova il Regno di Congo', September 22, 1820, in Filesi, ‘Epilogo’, pp. 433–4.

[35] ‘O Congo em 1845: Roteiro da viagem ao Reino de Congo por Major A. J. Castro … ’, Boletim de Sociedade de Geographia de Lisboa II series, 2 (1880), pp. 53–67. The orthographic irregularity reflects the actual pronunciation of these terms in the São Salvador region (the Sansala dialect).

[36] Alfredo de Sarmento, Os sertões d'Africa (Apontamentos do viagem) (Lisbon: Artur da Silva, 1880), p. 49 and Adolf Bastian, Ein Besuch in San Salvador: Der Hauptstadt des Königreichs Congo (Bremen: Heinrich Strack, 1859), pp. 61–2.

[37] Castello de Vide, ‘Viagem', pp. 102–3 and da Firenze, ‘Relazione', pp. 420–1.

[38] Castello de Vide, ‘Viagem', p. 137.

[39] Castello de Vide, ‘Viagem', pp. 180–4.

[40] da Dicomano, ‘Informazione', pp. 1–7.

[41] Castello de Vide, ‘Viagem', pp. 32–4; da Dicomano, ‘Informazione', pp. 1–7; Zanobio Maria da Firenze, ‘Relazione della Stato in cui si trovassi autalmente il Regno di Congo … 1814’, July 10, 1816, in Filesi, ‘Epilogo’, pp. 420–1.

[42] Archivio ‘De Propaganda Fide' (Rome) Acta 1758, ff 213–9, no. 16, Relazione di Rosario dal Parco, July 31, 1758. These large numbers were not simply priests catching up on people who had not been baptized for a long time, as personnel staffing and statistics are found from 1752 onward; but the priests did not cover the whole country every year, so many priests would baptize babies all under age two or three.

[43] Castello de Vide, ‘Viagem', pp. 63–4; see also 87 for another noble as Captain of Church; 136 crowds at Mapinda.

[44] da Dicomano, ‘Informazione', pp. 1–7.

[45] da Firenze, ‘Relazione', pp. 420–1.

[46] ‘Il Stato in cui si trova il Regno di Congo', September 22, 1820, in Filesi, ‘Epilogo’, pp. 433–4.

[47] Francisco das Necessidades, Report, March 15, 1845, in Arquivo do Archibispado de Angola, Correspondência de Congo, 1845–1892, cited in François Bontinck, ‘Notes complimentaire sur Dom Nicolau Agua Rosada e Sardonia’, African Historical Studies 2 (1969): 105, n. 6. Unfortunately, no researchers have been allowed to work in this section of the archive for many years and so the actual text is not available.

[48] Report of November 13, 1856 in António Brásio, ‘Monumenta Missionalia Africana’, Portugal em Africa 50 (1952), pp. 114–7.

[49] Biblioteca d'Ajuda, Lisbon 54/XIII/32 n° 9, Francisco de Salles Gusmão to the King, de Outubro de 27, 1856.

[50] Da Cruz, entry of October 8 and 25 on the problems of baptizing people.

[51] da Dicomano, ‘Informazione', is the first to describe this process; for more detail see Bastian, Besuch.

[52] David Eltis, An Atlas of the Transatlantic Slave Trade.

[53] For a recent discussion of names and nomenclature, see Jésus Guanche, Africanía y etnicidad en Cuba (los componentes étnicos africanos y sus múltiples demoninaciones (Havana: Editoria de Ciencias Sociales, 2008). As we shall see, a number of other subdivisions also derived from the kingdom like the Musolongos, Batas and others.

[54] John Thornton, Africa and Africans in the Formation of the Atlantic World, 1400–1800, 2nd ed. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), for Cuba in particular, Matt Childs, ‘Recreating African Identities in Cuba', in The Black Urban Atlantic in the Era of the Slave Trade, eds. Jorge Cañizares-Esquerra, Matt Childs, and James Sidbury (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013), pp. 85–100.

[55] Robert Jameson, Letters from Havana in the Year 1820 … (London: John Miller, 1821), pp. 20–2 (from letter II).

[56] Fernando Ortiz, Hampa Afro-Cubana. Los Negros Brujos (Havana: Liberia de F. Fé, 1906), pp. 81–5; and further developed in ‘Los Cabildos Afrocubanos', in Ensayos Etnograficos, eds. Miguel Barnet and Angel Fernández (Havana: Editoriales Sociales, 1984 [originally published 1921]), pp. 12–34; for a more recent statement based on more research, Matt Childs, The 1812 Aponte Rebellion and the Struggle Against Atlantic Slavery (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006), pp. 209–45 and María del Carmen Barcia Zequeira, Andrés Rodríguez Reyes, and Milagros Niebla Delgado, Del cabildo de “nación” a la casa de santo (Havana: Fundación Fernando Ortiz, 2012).

[57] For example, the now famous community of Pindar del Rio, see Natalia Bolívar Arostegui, Ta Makuende Yaya y las Reglas de Palo Monte: Mayombe, brillumba, kimbisa, shamalongo (Havana: Ediciones UNION, 1998).

[58] Childs, Aponte Rebellion, pp. 209–12; Jane Landers, ‘Catholic Conspirators: Religious Rebels in Nineteenth Century Cuba', Slavery and Abolition 36 (2015): 495–520.

[59] Brown, Santería Enthroned, pp. 62–112; María del Carmen Barcia, Los ilustres apellidos: Negros en la Habana colonial (Havana: Oficina del Historiador de la Ciudad, 2008), pp. 45–151; Barcia, Rodríguez Reyes, and Niebla Delgado, Del Cabildo which carefully demolishes the earlier theses of Fernando Ortiz and others that the cabildos grew out of the brotherhoods.

[60] This group must have split or been replaced by another, for a property dispute in the Congos Loangos relates to their foundation in 1776, Archivo Nacional de Cuba (ANC) Escribanía Valerio-Ramirez (VR) legajo 698, no. 10.205.

[61] Barcia, Iustres Apellidos, pp. 45–151.

[62] Barcia, Ilustres Apellidos.

[63] del Carmen Barcia Zequeira, Rodríguez Reyes, and Niebla Delgado, Del cabildo, pp. 12–9.

[64] Fernando Ortiz, ‘Los Cabildos Afrocubanos', in Ensayos Etnograficos, eds. Miguel Barnet and Angel Fernández (Havana: Ediciones Ciencas Sociales, 1984 [originally published 1921]), p. 13, citing documents in El Curioso Americano, 1899, p. 73.

[65] Proclama que en un cabildo de negros congos de la ciudad de La Habana, prononció por su Presidente Rey Siliman Mofundi Siliman … (Havana: np, 1808); for the claim of superiority, drawn from an ambiguous statement that he was ‘more black that you others’, see Brown, Santería Enthroned, pp. 25–7 and 311, footnotes 4 and 6. For political context, see Ada Ferrer, Freedom's Mirror: Cuba and Haiti in the Age of Revolution (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014), pp. 247–9.

[66] Fredrika Bremer, Hemmen i den Nya Världen, 2nd ed., Vol. 3 (Stockholm: Tidens forläg, 1854), p. 142 (English translation as The Homes of the New World: Impressions of America, Vol. 2 (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1853), p. 322) Her host's name is given in the original and obscured in the translation as ‘C—'.

[67] Bremer, Hemmen, Vol. 3, pp. 146–8 (Homes Vol. 2, pp. 325–8).

[68] Henri Dumont, Antropologia y patologia comparadas de los Negros escalvos, 1876, trans. Israel Castellanos (Havana: Molina, 1922), p. 38.

[69] Bremer, Hemmen, Vol. 3, pp. 172–4 (Homes Vol. 2, pp. 348–9).

[70] Bremer, Hemmen, Vol. 3, p. 213 (Homes Vol. 2, p. 383).

[71] Esteban Pichardo, Diccionario provincial de voces Cubanas (Matanzas: Imprenta de la Real Marina, 1836), p. 72. Musundi may refer to Kongo's northern province of Nsundi, though the match is not exact since the nasal ‘n' is not incorporated into it, musundi might also mean ‘excellent', as the Virgin Mary was called ‘Musundi Madia' in the Kongo catechism meaning exactly this.

[72] It is possible that Bremer attended the dance of another Cabildo of Congos Reales, who were in the process of declaring their insolvency in 1851, ANC Escrabanía Joaquin Trujillo (JT) leg 84, no. 12, 1851; for a 1867 dispute, see the property case involving them in ANC VR leg. 393, no. 5875; other mentions of cabildos of this name including the group from 1865–1871 in Carmen Barcia, Ilustres apellidos, p. 408. For the 1880s mentions, see Archivio Historico de la Provincia de Matanzas (henceforward AHPM), Religiones Africanas, leg 1, no. 30, July 7, 1882; no. 65, January 9, 1898 and no. 31, July 31, 1886.

[73] Fondo Fernando Ortiz, Institute de Linguistica y Literatura, Havana, 5.

[74] ANC Escibanía d'Daumas (ED) leg 917, no. 6. (foliation uncertain, very deteriorated document).

[75] António de Oliveira de Cadornega, História das guerras angolanas (1680–81 ), eds. Matias de Delgado and da Cunha, Vol. 3 (Lisbon: Agência Geral do Ultramar, 1940–1942, reprinted 1972), p. 3, 193. In July 2011, I drove through all three dialect zones, confirmed some of the differences by hearing them spoken and by speaking with people about these differences. My thanks to Father Gabriele Bortolami, OFMCap for driving, interacting with people, impromptu language updates and occasional lessons in the etiquette of dialect use in northern Angola.

[76] Cherubino da Savona, ‘Breve ragguaglio del Congo … ’, fols. 41v–44v, published with original foliation marked in Carlo Toso, ed., ‘Relazioni inedite di P. Cherubino Cassinis da Savona sul ‘Regno del Congo e sue Missioni’, L'Italia Francescana 45 (1974): 135–214. The foliation of the original is also marked in the French translation, found in Jadin, ‘Aperçu de la situation au Congo … '

[77] ANC ED, leg 494, no. 1, fols 96–97. This text was included in papers dealing with another dispute in 1827–1828 and in 1832–1836.

[78] ANC ED, leg 548, no. 11, fol. 9–9v; José Pacheco, January 21, 1806; ANC ED, leg. 660, no. 8, fols. 1–4; Pedro José Santa Cruz (a request for its own capataz) 1806; for the later dispute ANC ED leg 494, no. 1.

[79] ANC ED, leg 660, no. 8, fol. 4.

[80] ANC JT, leg. 84, no. 13 passim, 1851.

[81] AHPM, Religiones Africanas, leg 1, no. 30, July 7, 1882.

[82] AHPM, Religiones Africanas, leg 1, no. 65, January 9, 1898.

[83] AHPM, Religiones Africanas, leg 1, no. 31, July 31, 1886.

[84] Brown, Santería Enthroned, pp. 55–61 and Barcia Zequeira, Rodríguez Reyes, and Delgado, Cabildo de nación.

[85] Childs, Aponte Rebellion, p. 112 and ‘Identity', p. 91.

[86] Consider the temporal range of inquisition cases cited in Tania Chappi, Demonios en La Habana: Episodios de la Inquisición en Cuba (Havana: Oficinia del Hisoriador de la Ciudad, 2001). For an example of the sort of persecution the Inquisition could do, and the sort of information that can be obtained from their records, see James Sweet's study of slave religious life in Brazil, Recreating Africa.

[87] Jameson, Letters, pp. 20–2.

[88] See the transcript of his interview published in Henry Lovejoy, ‘Old Oyo Influences on the Transformation of Lucumí Identity in Colonial Cuba' (PhD diss., UCLA, 2012), pp. 230–46.

[89] Aisha Finch, Rethinking Slave Rebellion in Cuba: La Escalera and the Insurgencies of 1841–44 (Chapel Hill: North Carolina Press, 2015), pp. 199–220. Finch attributes most of the activities in these cases to the non-Christian part of Kongo religion, or an early form of Palo Mayombe; see also Miguel Sabater, ‘La conspiración de La Escalera: Otra vuelta de la tuerca', Boletín del Archivo Nacional 12 (2000): 23–33 (with quotations from trial records).

[90] Bremer, Hemmen, Vol. 3, p. 213 (Homes Vol. 2, p. 383).

[91] Bremer, Hemmen, Vol. 3, pp. 211–3 (Homes Vol. 2, pp. 379–83).

[92] Cabrera, Reglas de Congo, p. 26, citing late eighteenth- and nineteenth-century sources.

[93] Abiel Abbott, Letters Written in the Interior of Cuba … (Boston, MA: Bowles and Dearborn, 1829), pp. 15–7.

[94] Cabrera did not employ any orthography of contemporary Kikongo in her day, but it is not at all difficult to recognize her ear for that language, which she did not speak, and most quotations she provided are readily intelligible.

[95] Institute de Linguistica y Literatura, Havana, Fondo Fernando Ortiz, 5. This list, written in a different hand than Ortiz’, one that was shakier with large letters, on fragile aged paper (perhaps school paper) was, I believe, compiled by a literate person who was a native speaker of the language, based on his use of Kikongo grammatical forms (use of verb conjugations and class concords in particular).

[96] Armin Schwegler, ‘On the (Sensational) Survival of Kikongo in Twentieth Century Cuba', Journal of Pidgin and Creole Languages 15 (2000): 159–65; Jesús Fuentes Guerra, La Regla de Palo Monte: Un acercamiento a la Bantuidad Cubana (Havana: Iberoamericana Vervuert, 2012) (neither Schwegler nor Fuentes Guerra had access to Puyo's vocabulary in Ortiz’ documentation, the contention of its identity with Kikongo is my own). It seems likely that both Cabrera's and Ortiz’ vocabularies were collected probably from old native speakers, who entered Cuba at the end of the slave trade.

[97] For example, the class marker ki in the southern dialect is –ci in the north; use of ‘l' versus ‘d' would be another difference. The northern dialect is well attested in dictionaries of the French mission to Loango and Kakongo in the 1770s, compared with seventeenth- and nineteenth-century dictionaries of the southern dialects. I have also heard these differences myself in Angola.

[98] Fernando Ortiz, Hampa Afro-Cubana. Los Negros Esclavos (Havana: Bimestre Habana, 1916), pp. 25, 32 (clearly, testimony from the same informant).

[99] Ortiz, Negros Esclavos, p. 34. The term ‘Totila', clearly derived from the Kikongo ntotela meaning ‘king'. The word is first attested in the Kikongo dictionary of 1648, as meaning ‘King'. In 1901, King Pedro VI of Kongo, writing in Kikongo, styled himself ‘Ntinu Ntotela NeKongo' Archives of the Baptist Missionary Society (Regents’ Park College, Oxford) A 124 (both ntinu and ntotela can be glossed as ‘king').

[100] Cabrera, Reglas de Congo, p. 15.

[101] Cabrera, Reglas de Congo, p. 109. Cabrera, for her part, then told him of Nzinga a Nkuwu's baptism in 1491, presumably from one of the historical accounts she had read.

[102] On the assertions of Dona Beatriz Kimpa Vita, see Thornton, Kongolese Saint Anthony; on the representation of Christ as an Kongolese, Fromont, Art of Conversion.

[103] Cabrera, Reglas de Congo, p. 93.

[104] Cabrera, Reglas de Congo, p. 58.

[105] Cabrera, Reglas de Congo, p. 59.

[106] Cabrera, Reglas de Congo, p. 14.

[107] Cabrera, Reglas de Congo, p. 19.

[108] The problem was apparent to Lydia Cabrera in her study of Palo, El Regla de Congo: Palo Monte Mayombe (Miami: Ediciones Universal, 1979), pp. 120–30, as one can see from the defensive tone of her informants, probably speaking with her post-1960 experience (this is not seen as a problem in her earlier publication, El Monte (Havana, 1954)).

[109] Cabrera, Vocabulario, p. 123.

[110] Cabrera, Monte, pp. 119–23 passim (here, often used in the context of witchcraft); Reglas de Congo, pp. 24–5. In W. Holman Bentley, Dictionary and Grammar of the Kongo Language (London: Kegan Paul, 1887), p. 361, which relates to the Kinsansala dialect (the most likely associated with Christianity) in the 1880s, mvumbi meant simply the corpse of a dead person; in the 1648 dictionary ‘spirits' was rendered as ‘mioio mia mvumbi' (or souls of corpses).

[111] Cabrera, Reglas de Congo, p. 24. In Kikongo, mvumbi means a corpse, the lifeless remains of a dead person, and the name of an ancestor would usually have been nkulu, though this usage would still make sense in Kikongo.

[112] See John Thornton, ‘Central African Names and African American Naming Patterns', William and Mary Quarterly, 3rd Series, 50 (1993): 727–42.

[113] The denunciation of the first tooth ceremony is only attested in the general complaints of the Capuchins in the 1650s, written by Serafino da Cortona.

[114] ‘Kisi malongo' appears to be ‘nkisi malongo'. A more likely way to say ‘the teaching of nkisi' would be ‘malongo ma nkisi', so the word order puzzles me. However, word order in Kikongo is flexible and should the speaker wish to emphasize the teaching spiritual part, it might be feasible to use this order.

[115] Cabrera, Reglas de Congo, p. 24. My translation of the phrase ‘nganga la musi' assumes that the speaker has only partial command of Kikongo grammar and would be ‘nganga a mu nsi' The same informant used the term kisi malongo, and perhaps as a Cuban-born person was not secure in the language.

[116] Cabrera, Regla de Congo, p. 23.

[117] Institute de Linguistica y Literatura, Havana, Fondo Fernando Ortiz, 5.

#The Kingdom of Kongo and Palo Mayombe: Reflections on an African-American Religion#Palo Mayombe#ATR#African Traditional Religions#Kongo#Reglas De congo#Nkisi#Kikongo

1 note

·

View note

Video

youtube

Yannick Afroman - Bakongo ft. Sam Mangwana, Socorro, Kyaku Kyadaff, Gilmário Vemba

Yannick Afroman - Bakongo ft. Sam Mangwana, Socorro, Kyaku Kyadaff, Gilmário Vemba

#youtube#Yannick Afroman#Bakongo#Sam Mangwana#socorro#Kyaku Kyadaff#Gilmário Vemba#Kongo Dia Ntotila#Bantu#Kikongo#Mukongo#People#DRC Congo#Cabinda#Angola#Languages#português#culture#food#countries#tribe#music

0 notes

Note

do you believe Love Deterrence was kind of a love confession from Kaz to BB?

Sort of. Kind of. I do think it was about BB, and we know the lyrics are written by Kaz.

I don't know if we ever find out all the languages that BB speaks, obviously English, Russian, Spanish, that leaves iirc 3 more languages he speaks, and I don't know if Japanese is ever confirmed as one.

It seems likely given that he speaks to Kojima in PW, and that BB speaking other languages is translated for the player, but Venom also speaks to him and gets a verbal response in TPP, and we know that was in English due to [mumbled summary of TPP plot]. That's probably the closest we get to confirmation.

Anyways my point with that is, I tend to think that BB doesn't speak Japanese, at least not around Kaz, and Kaz intentionally wrote Love Deterrence in a language he didn't think BB knew so that he could get his feelings out without the utter mortification of actually sharing them.

#mgs#bbkaz#if anybody actually knows or has hunches about BB's language list im all ears i want to know#or any of them really#we know liquid “speaks arabic like a native” which is fascinating. like. which dialect?#khaliji would probably make the most sense since he was also in the gulf war#but almost equal chance of anything else as well given it is Year Of Our Lord 2005 when this takes place and uh#bestie we (westerners as a whole) did not really uhhh...what is the word...care...about the diversity of the arab world at that time#but idk its funny to me that *that* is what they choose to point out when he literally speaks kikongo for a large portion of his childhood

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

Exploring the Rich Linguistic Heritage of Kikongo and Kituba Languages in the Kongo Kingdom

Uncovering the Secrets of the Kikongo Language and People Located in the heart of Central Africa, the Kikongo language has a rich cultural heritage that has been passed down through the centuries. This ancient language spoken by the Bakongo people provides fascinating insight into the region’s history, traditions and way of life. In this article, we delve into the fascinating world of the…

View On WordPress

#African Languages#Bakongo people#Bantu languages#Cultural Heritage#inclusivity#Interpretation Services#Kikongo language#Kongo Kingdom#Language Preservation#LanguageXS

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Weekly Reads : Nov. 2023 "Accessing A New Road"

This is the final part of my weekly reads of November 2023🔌 Go back, watch all 4 parts on TikTok, consider what you’ve been experiencing each week and this month as a whole.

Where and how have doors opened and closed? How are you doing the work to stay aligned with the path leading to the Open Road and are you open to guidance thats contrary to what you think is “right”?

🧿 Check out www.lifesizeddoll.com for personal spiritual work with me 🧿 Longer content on my FB page : The Magik Mirror

#tarot spread#divination#spirituality#astrology#sidereal astrology#november reading#fall 2023#chalks of Kikongo#mirror#healing#motivation

0 notes

Text

Most Afrikans Will Say They Are the Oldest and First People.

The Igbo people will say they are the first and oldest people in the world. The Yoruba people of Nigeria will also say the same. The Ewe in Ghana called themselves, Amuawo, which means the first people, which has the same meaning as Akanfo.

The Great Kongo.

In the Great Kongo, the BaKongo people will say, "The Kikongo language, is the language of creation." This is how far back our history goes. To the dawn of time and the universe (Ye fre tete Odomankoma).

We know who we are. We know our history. The first people. Speaking the most ancient of languages. Languages that formed the foundations of all major languages in the world.

Do the Asians and Europeans (who our ancestors called Ofre Jato, (albinos), know their true history and origins? We know who we are. Do they know who they are and their very true origins?

#history of the world#albinos#europeans#asians#african history#bakongo#akan#yoruba#igbo#igbo culture#akan institute#history#africa#african#caucasus#west asia#russian steppe#history of africa#humanity

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kikongo está na minha lista pra aprender também, depois do Kimbundu. Esta música é um desbunde de lindeza!

#me #mg #kimbundu

9 notes

·

View notes

Note

Can you explain your process on how you chose human names, or how you found them I can't find shit on African-language names that aren't European.

So, my tip is that you probably wanna get more specific- if you look up stuff like "Republic of Congo Names," you're gonna get a list of the most popular names used in the Republic of Congo, which skews towards European style names. However, if you look up "KiKongo names" or "Luba names", you're much less likely to get European names. I also cross reference any names I pick out as an additional precaution- so if I like a certain name from a list of "X ethnicity" names, I peruse around for people from that ethnicity and see if that name actually exists among them!

#Tho i will say the human name for my lebanon I just chose 'Latif' because it suits him and I wanted to keep the L naming theme of the Levant#ask#shamangus#hetalia#tips

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

information

basics

full name: Elizabeth Irene Riley {{Birth-Certificate: Elikapeka Ailine Alohaekauneikahanuola'Ilikea'wahine Riley}}

nicknames / aliases: Beth, Apples, Konachino, Jelly Bean {{the nurse shark}}

height: 5 foot even

age: 27-35 {verse dependant}

spoken languages: English, Pidgin, French, Latin, Spanish, Basic/some: Russian, German, Greek, Japanese, Mandarin, Kikongo {Kituba}, Masalit

physical characteristics

hair color: deep chestnut/mahogany brown

eye color: green/honey brown {central heterochromia iridum}

skin tone: sand/olive with warm undertones { "deep autumn"}

body type: delicate/petite {ectomorphic/triangle}

dominant hand: left

posture: straight, graceful, poised

scars: The shark bite scar/muscle atrophy/shortened tendon {right leg}

tattoos: sea turtle with the Hawai'ian island chain on its shell, with a hibiscus {left hip} {eventually the tree of life as above/so below near the bottom of her neck/between her shoulder blades} She has three sub-dermal studs just inside the arch of her hip.

birthmarks: freckles around her chin, across her nose, sharp 'little' teeth

most noticeable features: Wide doe-eyes, 'fangy' smile, nose crinkles when she does so unguarded/genuinely.

childhood

place of birth: Pearl City/Honolulu, O'ahu, Hawai'i. {for Turn: Brooklyn, New York}

siblings: Andrew Riley, Jayden Morgan

parents: The Admiral, Iwalani Kahananui {Riley} Stern

adult life

occupation: ER Nurse/ER Doctor {verse dependant, might be NYPD or SHIELD agent} {for Turn: Wealthy Socialite}

current residence: Verse dependent {for Turn: Philidelphia, Boston, NYC} close friends: this is an entire blog roll roster of my beloved mutuals, so verse dependent? {For Turn: Ben and Samuel Tallmadge, Caleb Brewster, Anna Strong, John Simcoe, Malcolm Baker}

relationship status: Verse dependent. Beth doesn't so much date as she lurks, closely. Waiting for all parties involved to tire out and just move in.

children: Beth is incapable of having children, but loves everyone else's. {Turn: None...yet.}

criminal record: various juvenile charges for destruction of property, vandalism, and the like. All neatly sealed and never to be spoken of again.

vices: entirely too fond of a glass or six of wine in the 'evenings'. workaholic.

sex and romance

sexual orientation: demi-sexual {{I would say she leans towards heterosexual but the body isn't exactly a concern for her, so long as she likes/feels connected to the person}}

turn-ons: Intelligence, kindness, wittiness, passionate, idealism, honesty, empathy, caring for other people, the environment, animals.

turn-offs: Cruelty, abuse {physical/verbal/of power, etc}, lack of respect, refusal to accept boundaries, one night stands

love languages: physical touch, acts of service, quality time

relationship tendencies: Beth tends to be slightly oblivious when it comes to relationships. She is avidly keen in getting to know people, cannot help but to try and nurture them in what seem to be natural ways as much as she's able to. She doesn't experience sexual attraction until well after feeling bonded to someone. This can lead to many mixed signals. When it comes to love/sex/romance, Beth tends to be a little naive and extremely trusting,and that has always broken her heart in the past. Beth doesn't do one night stands, or casual hook-ups, though she doesn't judge others for them. Some people might consider her clingy.

miscellaneous

hobbies to pass time: surfing, dancing, knitting, reading, gardening, card games, chess. {Beth is amusingly aggressive when it comes to competitive games/sports}

mental illnesses: Beth lives with bipolar disorder, shows signs of childhood trauma, and tends toward fear of rejection/abandonment self confidence level: Beth has all the self esteem of a banana slug outside of a medical-treatment setting. ~*~ tagged by: my darling M @honorhearted tagging: Tell me about your muses!

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Historians from Southern Illinois University in the Africana Studies Department documented about 20 title words from the Kikongo language are in the Gullah language. These title words indicate continued African traditions in Hoodoo and conjure. The title words are spiritual in meaning. In Central Africa, spiritual priests and spiritual healers are called Nganga.

In the South Carolina Lowcountry among Gullah people a male conjurer is called Nganga. Some Kikongo words have a "N" or "M" in the beginning of the word. However, when Bantu-Kongo people were enslaved in South Carolina the letters N and M were dropped from some of the title names. For example, in Central Africa the word to refer to spiritual mothers is Mama Mbondo. In the South Carolina Lowcountry in African American communities the word for a spiritual mother is Mama Bondo. In addition during slavery, it was documented there was a Kikongo speaking slave community in Charleston, South Carolina

#nganga#mama mbondo#slave community#charlestonch#charleston south carolina#afrakan#kemetic dreams#africans#african#brownskin#brown skin#afrakans#african culture#afrakan spirituality#central africa#kikongo language#gullah#gullah geechee#gullah gullah island

96 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bakongo (also known as Mkongo or Mukongo). In one of the Bantu languages, Kongo, the word “Ba” means “People” while “Kongo” according to an adventure means “Hunter” while according to others it means “Gathering” or “Mountains”. There is yet to a decisive context for it. Even the term “Congo” was a term used to refer to black people who spoke “Kikongo” in Cuba, America. The Bakongo people speak Kinkongo language which also compromises of 9 other language variations for different sub-branches of the Bantu tree; for example the Kivil dialect by the north coast, the Kisansolo in the central dialect, amongst others.

The 13th – 14th century saw the creation, transition, and building of the great Kingdom of Kongo. The kingdom succession was based on voting by the noble of the land which kept the king’s lineage among royalty. In the late 14th century, what was supposed to be a quick stop for the portugese

Allegedly, the Portuguese were in search of a route to India for opportunities when one Diego Cao found the river Congo. Moving south he and his companions found the people of Kongo in an organized system; valuable currency, trading relations, transport infrastructure, port settlements, and open-minded people.

The people of Kongo accepted them and even the king willingly accepted Christianity in a show of solidarity with these new people. Once a man, Chief Muanda, warned the people of the coming doom of slavery of the Bakugo clan which will destroy the kingdom, he said it will begin with the visitation of foreigners but people choose what they want to see even though he was later right. By the 19th century; the Kingdom of Kongo had completely fallen, the Bakongo people had fully divided and spread across different parts of the continent.

The Bankongo people are the third-largest group in Angola but in the 17th century, they lost a war to Portuguese during the repression. They moved throughout the continent occupying the northern regions of places like Cabinda, Congo, Angola and Zaire. In the 20th century, the Bakongo created a political party called the Union of Angolan Peoples (UPA) in an attempt to bring back all the Bakongo people, eventually, they decided an independent country filled with different tribes was much better for their society. Soon after that decision, they fought along the Ovimbundu and the Mbundu people for a better Angola.

In 1975, Angola gained its independence with a lot of Bakongo people being the faces for the win but as soon as the Mbundu people took over the ruling power there was discrimination among all three tribes. In the present time, their largest numbers are in Congo and though they’ve been through a lot, they have kept some of their cultural practices.

13 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

KIZABA - FESTIVAL CENTRO 2025

Vocalista, baterista, compositor, arreglista, multi instrumentista pionero de la música electrónica afro congoleña, ejecuta al vivo su canto en idiomas francés, inglés, kikongo y lingala. Su propuesta se clasifica en el concepto del afrofuturismo global y fusiona las tradiciones congoleñas con un moderno afro beat que combina melodías y ritmos africanos en géneros como la música electrónica, el house, funk, R & B. https://youtu.be/6mAjEFdnLb4

#youtube#kizavibe#bogota#colombia#chile#brasil#recife#liverpool#taipei#taiwan#chine#chinese#canada#kinshasa#free congo#sud africa#tanzania#kenya#sENEGAL#mali#burkina faso#brazaville#rdc congo#festive#fest#festa#pop stars#ARTISTIQUE#FESTIVAL#ibiza

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

CRACKPOT THEORY: Baron Samedi was worshiped in New Orleans during the 19th century.

Here is all the evidence I have collected to support this hypothesis.

1. THE “CLOPIN-CLOPANT” STORY FROM THE DAILY PICAYUNE

"Clopin-Clopant" is a story that was published in the Daily Picayune of New Orleans, on Sunday, December 25th, 1892, page 21.

The full article can be viewed online here: https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-times-picayune/90528775/

In the following excerpt, the author describes “the great Zombi” as a dangerous, angry spirit that Haitian slaves brought with them to New Orleans following the Revolution:

“Somehow or other Clopin-Clopant was held directly responsible by the ignorant blacks und whites for every misfortune that happened in the faubourg. To the former, gradually imbued with the wild theories of fetish belief brought to New Orleans by the San Domingo negroes after the island insurrection, the old hunchback was the slave of the great Zombi, and many whispered he was the Zombi himself, who had followed them in anger from his chosen island to wreak vengeance upon them and their masters wherever they dwelt.”

Later, “the great Zombi” is described as having the power to create more “Zombis”:

“But governor commands him, in the name of the king, to open the portal and come forth. And obeys tremblingly, and, falling upon his knees, says: "Monsieur, have pity! I am not the Zombi! I have never harmed any one in my life. I am only a miserable old man, who wants to die in peace. I am not the Zombi." "Tiens!" cried the governor indignantly, "we want a hundred Zombis like you in New Orleans. Rise, monsieur, and receive from your fellow citizens the reward of your noble service.”

Here is a question for New Orleanians… How is the “Zombi” in “great Zombi” pronounced?

Is it pronounced like the Haitian zonbi, or the English zombie?

Sometimes, I hear people pronounce the “Samedi” in “Baron Samedi” like the name “Sam”, but this is not accurate.

Here is how “Baron Samedi” (really, Bawon Sanmdi) is actually pronounced: https://youtu.be/NN9pGa5GmZ4?feature=shared&t=575

It is pronounced similarly to the English word zombie, and the Kikongo nZambi.

(this is why I think the Sanmdi in Bawon Sanmdi could be African in origin… although not necessarily derived from nZambi…)

Importantly, Baron Samedi is associated with the creation of zombies. Really, zonbi. In order to create a zonbi, you have to go through him.

If Zombi is pronounced like the English word zombie, I think it is plausible that the real identity of the “great Zombi” in this story is Baron Samedi. The author may have invented this story because they overheard tales involving Bawon Sanmdi and zonbi from the descendants of Haitians who arrived in New Orleans. Hence, they confused great Zombi with Bawon Sanmdi.

2. MARIE LAVEAU’S WORSHIP OF “THE SPIRIT OF DEATH”

In The Magic of Marie Laveau (2020), Denise Alvarado describes how Marie Laveau worshiped the Spirit of Death:

While not explicitly called by name in rituals described by reporters and witnesses of Marie Laveau's magick, I believe he may have been represented. In her gris gris ceremonies, Marie Laveau always summoned Li Grand Zombi; but in one description, she also called upon the Spirit of Death: “She summoned the spirits of darkness and death, the supreme power of the great Zombi, who protects and hears the Voudoo's prayer” when suddenly, “there appeared in the group the Voudoo, being clad in the garb of death . . . he wore a skull and crossbones upon his bosom and carried a scythe in one hand and a small wooden coffin in the other” (Times Daily Picayune 1890, 10). A ritual is then described whereby the Spirit of Death knelt in front of the serpent and knocked on the ground three times. Grabbing a rag doll from the altar, he placed it into the little coffin along with a handful of dirt gathered from the ground—more than likely grave dirt. Once he closed the coffin, it signaled the point of the ceremony when all of the participants approached the gris gris pot and received their portion, and the Dance of Death, known today as the Banda, commenced.

Source: Alvarado, Denise. The Magic of Marie Laveau: Embracing the Spiritual Legacy of the Voodoo Queen of New Orleans. Weiser Books, 2020.

I wouldn’t read much into the physical description of this Spirit of Death, due to the unreliable, sensationalized coverage Voodoo received in newspapers.

In Witch Queens, Voodoo Spirits, and Hoodoo Saints: A Guide to Magical New Orleans (2022), Alvarado provides an additional clue: the use of purple robes during a ceremony hosted by Marie Laveau.

Previously, I had been under the impression that this was the same ceremony that involved the “Spirit of Death”, but this is not the case. For this reason, I think this piece of evidence is weaker than I’d thought, as the use of purple robes could be coincidental.

Here is the full context, so you can draw your own conclusions:

Another clue recently became evident. According to one individual who called himself Pops, “This was around 1875. She was dressed in a long purple robe with some kind of rope around her waist . . . da women coworkers wore purple, too. Da men wore white and purple . . .” (Dillon, Folder 025). Voudous who serve the Guédé and Baron Samedi wear purple when conducting rituals specifically for those spirits, as purple, black, and white are their colors. This informant was about eighty-one years old at the time of the interview and was believed to have been a reliable witness and suspected of knowing much more than he offered to interviewers.

Source: Alvarado, Denise. Witch Queens, Voodoo Spirits, and Hoodoo Saints: A Guide to Magical New Orleans. Weiser Books, 2022.

The full excerpt can be found in Robert Tallant’s Voodoo in New Orleans:

Howard LeBreton, a very old colored man, recalled the crowds that attended a Voodoo dance in 1875.

“This one was out by Lake Pontchartrain,” he said, “and thousands of people come out to see it. I can remember it good. The Voodoos danced on barges on the water just away from the shore and they carried all kinds of torches and lighted candles. The queen was dressed in a long purple dress with a blue cord ’round her waist, and all her co-workers wore purple dresses, too. And they didn’t wear nothin’ underneath. Them was what they called good-time dresses. The men wore white pants wit’ purple shirts and they carried white candles.

“You never seen such dancin’ in your life. They all danced first slow, then faster. They would go ’way down to the ground and come up shakin’.

“On the barges they had statues of saints and altars and lots of stuff to eat. They had wine and beer and everybody got drunk. It was just like a picnic.”

Despite all this, Howard contended that white people did not see all the Voodoo meetings. “There was some nobody but the real Voodoos ever seen,” he said. “People didn’t know that, but it’s the truth.”

Source: Tallant, Robert. Voodoo in New Orleans. United Kingdom, Pelican Publishing Company, 1983.

3. “THE DEVIL” IN “THE HIGH SILK HAT” AND “FROCK COAT”

Newbell Niles Puckett (1926) describes how “the Devil” appeared to African Americans in the South:

“...Most of the time, however, when going about on the earth, the Negro devil has the appearance of a gentleman, wearing a high silk hat, and a frock coat, and having an "ambrosial curl" in the center of his forehead to hide the single horn which is located there. Mrs. Viriginia Frazer Boyle tells me that when she was first taken to church by her father and mother she used to scan the congregation eagerly for a man with that "ambrosial curl" and one with the "evil eye", which her old Negro nurse had told her were to be found in every crowd, even in church. In most cases this Negro devil has cloven feet, a characteristic also credited to him in European circles. Possibly the black cat is the animal most chosen by the Negro devil for impersonation...Nevertheless the devil is not limited to this particular form but may appear as a rabbit, terrapin, serpent, housefly, grasshopper, toad, bat, or yellow dog at will. To the Mississippi Negroes he often appears as a black billy-goat; a view strictly in keeping with his custom at the English witches' Sabbath. In New Orleans it is thought by some that snakes and black cats are incarnations of the devil…”

Source: Puckett, Newbell Niles. Folk beliefs of the southern Negro. University of North Carolina Press, 1926. https://archive.org/details/folkbeliefsofsou00puck/page/552/mode/2up?q=devil

A figure “very similar” to this appears in Southern (specifically, Woodruff County) folktales: “He is commonly seen near a crossroads, a cemetery, or, as is often the case, both simultaneously. Sometimes, as in Haiti, he holds a cane.”

Source: Jacobsen, K. (Nov. 1, 2002). The Society for the Study of Southern Literature, Volume 36, Issue 1: https://southernlit.org/volume-36-issue-one-fall-2002/

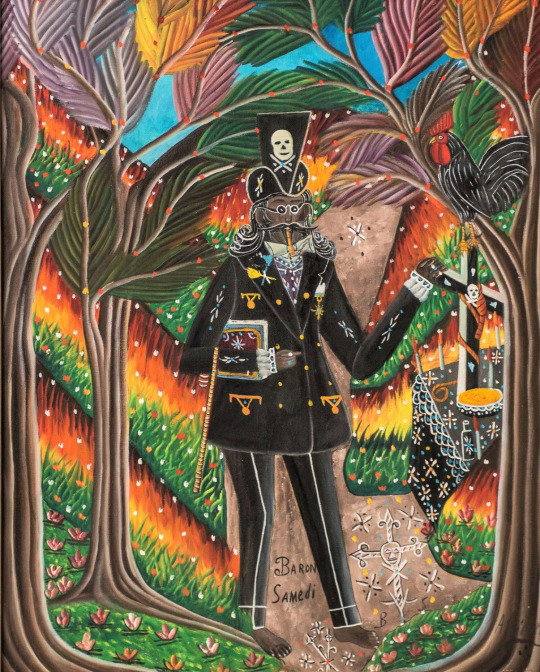

Here is Baron Samedi, as depicted by Andre Pierre, and described by Milo Marcelin:

“Baron-Samedi, père et chef des Guédé, est le maître des cimetières. On le représente sous les traits d’un noir robuste, qui porte une longue barbe blanche; il est vêtu d’une redingote, coiffé d’un melon ou d’un chapeau haut de forme, ganté de blanc; il a toujours en main un bâton coco-macaque et une bouteille de clairin ou rhum blanc. Une croix noire, sur laquelle figure parfois un crâne, est son Emblème.”

TRANSLATION:

“Baron Samedi, father and chief of the Guede, is the master of cemeteries. He is represented with the traits of a robust Black man, who sports a long white beard; he is dressed in a frock coat, dons a bowler hat or a top hat, white gloves; he always has a coco macaque stick in hand and a bottle of clairin or white rum. A black cross, on which sometimes appears a skull, is his Emblem.”

SOURCE: Marcelin, Milo. "Mythologie vodou (Rite Arada), Volume II." Pétionville: Éditions Canapé Vert (1950). p. 153

IS THIS THEORY CORRECT?

I do not know, but this theory can be validated or debunked.

I believe the earliest known list of the lwa is found in Duverneau Trouillot’s (1885) Esquisse ethnographique: Le vaudoun. If Baron Samedi is not named in this list, this would suggest he was never transmitted to New Orleans. Benjamin Hebblethwaite’s (2021) A Transatlantic History of Haitian Vodou might also include evidence that supports or disproves this theory. Sadly, I do not have access to either of these texts…

A final clue can be found in the Hoodoo Saint Expedite.

HOODOO IS NOT VOODOO YOU FUCKING IDIOT!!!

I KNOW! I KNOW!

I actually have a deep respect for what Hoodoo is, and the history behind it. It’s basically just “what if you strip all the frills and fluff away from magic”. It’s so practical and robust, I think it’s really cool – oh shit! I’m getting really off topic here!

Anyways, Hoodoo has a very underrated pantheon of Saints. Among them is Saint Expedite, who is petitioned for his mastery of magic.

Baron Samedi is also an extremely powerful magician, and according to Denise Alvarado: “In New Orleans Voudou, Baron Samedi is associated with St. Expedite.”

Source: Alvarado, Denise. Witch Queens, Voodoo Spirits, and Hoodoo Saints: A Guide to Magical New Orleans. Weiser Books, 2022.

Did the Haitians worship Baron Samedi in secret by hiding him under the name “Saint Expedite”?

People in the Hoodoo community – especially those further South – can probably determine whether there is any truth to this, or if it’s just bullshit!

As I write this, I think it’s probably difficult to definitely determine whether Baron Samedi was worshiped prior to the revitalization movement. Much like Maitre Carrefour, Baron Samedi is associated with the nocturnal aspect of Vodou, and is associated with the bòkò. Even if there is no evidence that he was worshiped, that does not mean he was not worshiped in secret.

In the words of “Pops”: “There was some nobody but the real Voodoos ever seen…People didn’t know that, but it’s the truth.”

#commentary#im not part of either community so i lack insight#but if they have not already done so i think it should be TOP PRIORITY for new orleans voodooists to network with people in the hoodoo comm#this should actually take priority over networking with haitians and west africans (although that's also important) for reasons i may expla#n at a later time...

4 notes

·

View notes