#irish rebellion

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

As for the person who was asking about Arthur suppressing the Irish rebellion and stuff like that...

I'll be honest, I always thought it was Uther who started the war and it just "bled onto" Arthur's reign and he sort of was not able to stop it until now, so he was forced to continue fighting to prevent damage to his own kingdom. And finally, when the Irish started being receptive to stop this, he immediately agreed - even going as far as to cause the discomfort of an arranged marriage, just to make sure it finally stops.

Yes, that's it. Uther conquered Ireland without even a proper war, he just invaded it during a time where the Houses were unable to fight. Then, Uther ruled over Ireland with an iron fist, often making his knights violently repress any spark of rebellion on the Irish side.

So, when Arthur got on the throne, he made those stop and tried to create a more united Camelot, in peace with Ireland and Wales under the Common kingdom of Camelot. During the years Arthur reigned (very young, very inexperienced and trying to pick up the pieces of the absolute mess that was the capital and the castle itself), the Houses got stronger and formed alliances through various marriages.

Then, they got strong enough to strike and the proper rebellion started. There didn't propose treates or tried to negotiate with the King - and in truth their primary objective was to kill Arthur because of his association with Uther. So, that is also why Arthur sent his knights to fight and the rebellion became a massacre on both sides.

And then yes, he was very agreeable to stop the bloodbath in any way possible, even going so far as to offer a marriage plus some concessions in spite of the Irish houses having lost the most important fights and effectively having lost the rebellion. Arthur has many nobles against him for this decision, thinking he went too soft instead of harshly punishing the houses responsible.

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

REBELLION RISING ON THE RISE: 2009-2018

THE FRANCE AND IRISH LINK TO THE REBELLION:

THE PARANORMAL HOTSPOT IN ROUSE HILL REGIONAL PARK

THE REAL CENTER OF THE CIVIL WAR OF THE REBELLION OF VINEGAR HILL PART 1:

My hypothesis is there is a link to the slave revolts in Haiti and the Battle of Vinegar ill where the Irish slaves attempted to overthrow their English captors.

This is founded by my initiation into haitian voodoo, 21 divisions creole spiritism which combines with my cereominal magician tradition starting HARDCORE at the same site (the battle site of vinegar hill) back in 2009.

All events were extreme paranormal and unexplained anomalous events, experienced by a friend and I who were yet to be formally initiated into ceremonial magick or vodou.

A magical portal was opened which took me until 2018 to close

many ufo and other supernatural events took place at this site

which can be ascribed to the closest site to the only civil war in Australia has ever witnessed.

My notes on the historical context from 2022

1789

After 1789, some Volunteer units showed their sympathy with the French Revolution by holding parades on 14 July to commemorate the fall of the Bastille. In 1792, Grattan succeeded in carrying an Act conferring the franchise on the Roman Catholics; in 1794, he introduced a reform bill that was even less democratic than Flood’s bill of 1783.

He was as anxious as Flood had been to retain the legislative power in the hands of men of property, for he had a strong conviction that while Ireland could best be governed by Irish hands, democracy in Ireland would inevitably turn to plunder and anarchy. The defeat of Grattan’s mild proposals helped to promote more extreme opinions. However, as soon as the Jacobin regime assumed power in France, radical Patriots became more reluctant to refer to France as a prime example of Catholic political action for the causes of liberty and justice. Nevertheless, one of the main inconsistencies on the Patriot political agenda by calling for increasing powers of the Irish parliament while maintaining the selective as opposed to universal suffrage seemed to have been dissolved.

However, the French Revolution also had a second, contrasting, effect. Conservative loyalists such as John Foster, John Fitzgibbon and John Beresford, however, remained opposed to further concessions to Catholics and, led by the ‘Junta’, argued that the ‘Protestant Interest’ could only be secured by maintaining the connection with Britain. In reactionary circles, it was used to emphasise the point that an open political debate without censorship as well as parliamentary reform could entail a severe blow to their special interests, and could be tantamount to inviting Radicals to overturn the political structure of the country, rather than just appeasing them. In particular, the French Revolution prompted relentless action against the radical wing of the Patriot movement, the United Irishmen that included many former Whigs. It also prevented more moderate Patriots from supporting some radical Patriot activities without reservation, depriving the Patriot movement of solidarity and unity.

1688-91

WILLIAMITE WAR

William of Orange - dutch born

William of Orange, the Dutch prince who became King of England, Scotland, and Ireland in the Glorious Revolution of 1688

Defeated catholic "james 2nd" in wiliamite-jacobite war.

Protestant ascendancy

THE DECLATORY ACT OF 1719

Loss of Independence due to the House of British Lords being able to pass laws in Ireland

Restrictions of commerce at the expense of ireland that favoured Britain were tipping this rise to the protestant ascendancy for GREATER freedoms from great britain.

ORANGE ORDER:

The basis of the modern Orange Order is the promotion and propagation of "biblical Protestantism" and the principles of the Reformation. As such the Order only accepts those who confess a belief in a Protestant religion.

As well as Catholics, non-creedal and non-Trinitarian Christians are also banned.

This includes members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints(Mormons), Jehovah's Witnesses, Unitarians, and some branches of Quakers.

Previous rules specifically forbade Roman Catholics and their close relatives from joining

but the current rules use the wording "non-reformed faith" instead. Converts to Protestantism can join by appealing to Grand Lodge.

James Wilson and James Sloan, who issued the warrants for the first Lodges of the Orange Order along with 'Diamond' Dan Winter, were Freemasons,[26] and in the 19th century many Irish Republicans regarded the Orange Order as a front groupestablished by Unionist Masons as a more violent and jingoist vehicle for the promotion of Unionism.[71] Some anti-Masonic evangelical Christian groups have claimed that the Orange Order is still influenced by freemasonry.[72] Many Masonic traditions survive, such as the organisation of the Order into lodges. The Order has a similar system of degrees through which new members advance. These degrees are interactive plays with references to the Bible. There is particular concern over the ritualism of higher degrees such as the Royal Arch Purple and the Royal Black Institutions

1795: the battle of richmond hill

Darug natives defend the land from british invaders

North richmond - pitt town wetlands.

1798

The first battle of vinegar hill

County wicklow

The catholics invasion and claim to the irish land and protestant ascendancy

Act of union 1800- rise to catholic invasion that allowed the mobilisation of the catholic poplation

Uniteed the british parliament and irish parliement in unity, to form a united front

Catholic resentment in leinster

1789

THE AFRO-CARIBBEAN LINK

UNITED IRISH PRISONER

JAMAICA

WEST INDIES

NEW FOUNDLAND

NEW SOUTH WALES

"United Irish" mutinies in Jamaica, Newfoundland and New South Wales

In October 1799 Castlereagh received reports from Jamaica that many (of the 3,200)

United Irish prisoners, "incautiously drafted" into regiments for service in the West Indies, had taken to the hills to fight alongside the Maroons and with the French: "as soon as they got arms into their hands they deserted".

There is no suggestion that this was part of any trans-Atlantic design of the United directory in Dublin or Paris.

The same is true of the "United Irish Uprising in Newfoundland" in April 1800. Two-thirds of the colony's main settlement, St. John's, were Irish, as were most of the island's locally-recruited British garrison. There were reports that upwards of 400 men had taken a United Irish oath, and that eighty were resolved to kill their officers and seize their Protestant governors at Sunday service. As in Jamaica, the mutiny (for which 8 were hanged) may have been less a United Irish plot, than an act of desperation in the face of brutal living conditions and officer tyranny.

Yet the Newfoundland Irish would have been aware of the agitation in the homeland for civil equality and political rights.

There were reports of communication with United men in Ireland from before '98 rebellion;of Thomas Paine's pamphlets circulating in St John's;and, despite the war with France, of hundreds of young Waterford men still making a seasonal migration to the island fisheries, among them defeated rebels who are said to have "added fuel to the fire" of local grievance.

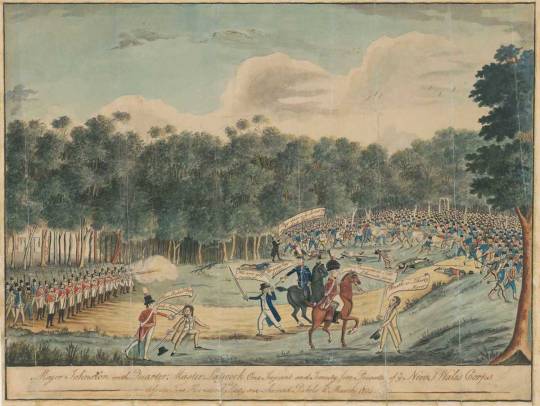

In March 1804, stirred by news of Emmet's rising, several hundred United Irish convicts in New South Wales tried to seize control of the penal colony and to capture ships for a return to Ireland.[204] Poorly armed, and with their leader Philip Cunningham seized under a flag of truce,the main body of insurgents were routed in an encounter loyalists celebrated as the Second Battle of Vinegar Hill.

The 1803 Michael Dwyer, who was a captain of the irish rebellion of 1798, transported to NEW SOUTH WALES

-1807 x 2 imprisoned and x2 trials for plotting against the british penal rule in NSW

1804

The second battle of vinegar hill

LIBERTY OR DEATH!

‘Death or Liberty’

The 1804 Castle Hill convict rebellion was led by Philip Cunningham of Moyvane, north County Kerry, a government stonemason who was convicted for his involvement in the 1798 Irish rebellion; he was also involved in a mutiny on board the convict transport ship, the Anne.

He was key figure in the planning of the rebellion, along with his rebel assistants William Johnston and Samuel Humes.[

Accompanied by over 200 frustrated armed Irish convicts, their aim was to capture ships and sail to Ireland. The rebels gathered at Castle Hill, calling on other convicts to join them.

Their intention was to march from Windsor to Parramatta, and then onto Sydney, gathering recruits along the way to attain a ship to bring them back to Ireland.

The Irish rebels were betrayed by an informer Keogh, who told the authorities of the Irish convicts’ plans.

By 1804, most of the Irish leaders of the previous attempts at rebellion had been imprisoned and moved to outlying areas of the colony such as Norfolk Island. Dispersal had worked well for the authorities but with each new rebellion plan, new Irish leaders rose among the convicts more aware of what not to do next time. The leaders of rebellion on 4 March 1804 were Phillip Cunningham and William Johnston.

Cunningham was a veteran of the 1798 conflict in Ireland and the mutiny of the convict transport ship Anne. From his experiences in Ireland and NSW he understood that secrecy and a non-traceable but effective communication were essential to a successful rebellion.

Cunningham’s emphasis on secrecy was so successful that it was not until the day before the rebellion that the authorities knew of its existence.

On the evening of 3 March, one of the Irish convict overseers turned informant. On Sunday 4 March, the day of the rebellion, two more informants came forward and provided names.

John Griffen was one of the informants and had been relaying a message to the pike-maker Bryan Furey that the rebellion was on for Sunday night.

Since Furey did not get the message the areas of Sydney, Parramatta and Windsor did not rebel.

Castle Hill was the only district that rose in rebellion.

Despite this intelligence, the authorities in Parramatta and Sydney did not act immediately and on 4 March 1804, John Cavenah set fire to his hut in Castle Hill at 8.00 pm. This was the signal for the rebellion to begin.

With Cunningham leading, 200 rebels broke into the Government Farm’s buildings, taking firearms, ammunition and other weapons. Initially, there was mayhem as buildings were ransacked to cries of ‘Death or Liberty’. Two English convicts dragged the Hills District flogger, Robert Duggan from under his bed and George Harrington an English convict beat him unconscious. A constable was saved from a musket ball in the face when the musket of John Brannon misfired.

Another constable was saved in similar circumstances when Jonathon Place’s musket also misfired. Cunningham gathered the rebels and reprimanded them for their lack of disciplined behaviour.

The rebels then went from farm to farm on their way to Constitution Hill at Parramatta gathering firearms, supplies and drinking any liquor they found. The looting of farms gave the rebels over 180 swords, muskets and pistols. In 1804, this was close to one third of the colony’s entire armoury

I do therefore proclaim the Districts of Parramatta, Castle Hill, Toongabbie, Prospect, Seven and Baulkham Hills, Hawkesbury and Nepean to be in a STATE of REBELLION; and to establish Martial Law throughout those Districts…

Cunningham’s plan involved burning the MacArthur property of ‘Elizabeth Farm’ in order to draw the Parramatta garrison out of the town.

Once this was done the rebels in Parramatta would rise up and set fire to the town as a signal. The Castle Hill rebels would gather at Constitution Hill and then raid the barracks for more arms and ammunition.

From there the rebels would march to Windsor and join up with the rebels in the Hawkesbury before marching on Sydney. At dawn on 5 March, rebels were still straggling in to Constitution Hill. Phillip Cunningham and William Johnston were busy drilling the rebels on the hill while they were waiting for the signal from the uprising rebels in Parramatta. The signal never came. Cunningham’s messages to the Parramatta and Windsor rebels had not got through. Cunningham decided that the rebels would head down the Hawkesbury Road to Windsor to meet up with the rebels from the Hawkesbury. Had Cunningham effected this, King maintained it would have increased his force by a further hundred rebels.[10]

Colonial paranoia increased once evidence of planned rebellion became evident after 1800 but how real was the threat from Irish convicts?

The Defenders and United Irishmen transported between 1795 and 1806 provided leadership to those convicts, many Irish but including English transportees, who were prepared to take direct action to overthrow the colonial authorities.

Although it was the Irish convicts who were a particular concern to Hunter, King and Bligh, it is important not to over-exaggerate their significance while under-estimating the involvement of convicts of other nationalities. In addition, the Irish convict leadership had considerable experience in planning and implementing rebellious activities.

This explains why successive governors sent leaders or presumed leaders, whether there was concrete evidence of sedition or not, to the more isolated penal settlements on Norfolk Island and VDL. This had the effect of disrupting any planning for insurrection.

Finally, hatred of the British in Ireland was transposed to NSW and this meant that Irish leaders had a willing supply of convicts who were prepared to support their actions.

That support came from non-Irish convicts is a reflection of the punitive and arbitrary nature of convict life. Where they were concentrated in one area, as on the Castle Hill farm, Ireland’s cause helped bind these men together.

However, there were major problems for those seeking rebellion. First, keeping planning secret was a major difficulty and only the Castle Hill revolt in 1804 saw planning converted into action.

Convicts were always willing to ‘split upon each other’ and this allowed the authorities to intervene before matters spiralled out of control.

Secondly, the objectives of rebellion such as the rallying cry of ‘Death or Liberty’ or demands for a ship to go home were idealistic and unrealistic. Although these may have been the aims of rebel leaders, there is little evidence that they were widely held by the rank-and-file, many of whom claimed that they had been forced into rebellion

Thirdly, as in Ireland during the 1798 rebellion, when faced with even inferior military force, the rebels could not translate numerical strength into military victory.

Finally, the hoped for French aid was illusory as it was never part of French strategy and, during the critical period from 1801 to 1804 war in Europe had been suspended.

It was the British government that was constantly afraid of convict rebellion and disorder though this did not stop it from sending political prisoners to NSW despite the concerns of successive governors. For the authorities, a colony composed largely of convicts was inevitably turbulent and rebellious, something reflected in Hunter’s and King’s despatches. In his reports on NSW and VDL, Bigge considered that the best security against rebellion was the higher standard of living that convicts generally enjoyed in NSW than in Britain and the opportunities and rewards open to those with industry and skill. Some convicts ‘bolted’ but only a few rebelled.

Rouse Hill Estate

Vinegar Hill was not a formal location in 1804.

The battle between the rebels and the soldiers became commonly known as the ‘Battle of Vinegar Hill’ after the Irish battle in 1798. Common usage of the name Vinegar Hill began to appear in the 1810s and 1830s in the Rouse Hill area.

But there is no formal Vinegar Hill on a map. There have been competing thoughts for the location of Vinegar Hill.

Originally it was thought to be Rouse Hill, George Mackanass challenged this in the 1950s marking the location of Vinegar Hill as the crossroads between Windsor Road and Schofields Road.

THIS WAS THE LOCATION OF ROUSE HILL REGIONAL PARK, in which my friend and I partook in rituals with an optical crystal ball resulting in FULL BLOWN MANIFESTATIONS.

-1816

Richard rouse

Built tollhouses, turnpikes, estates from Parramatta to Liverpool

On 8 October 1816 Rouse was granted 180 hectares (450 acres) near the site of the Castle Hill convict rebellion; at the suggestion of Macquarie the grant was named Rouse Hill. The actual possession of the land had taken place a few years previously, as the Sydney Gazette had first mentioned Rouse Hill on 27 November 1813, and the homestead was begun soon afterwards. It took a few years to build and was a two-storey, twenty-two room house, which has been occupied by members of the Rouse family ever since.

Old government house & THOMAS MITCHELL ROYAL PEDIGREE ANCESTRAL ASSET

& THE HIDDEN HAND OF PARRAMATTA GOVERNMENT HOUSE AND THE TIMEKEEPERS SOUTHERN HEMISPHERE

this is an actual freemasonic ancestral connection of mine... this links to the rebellion and the colonisation of the country.

The Observatory, erected in 1822 was part of Brisbane's intention to make Parramatta "the Greenwich of the Southern Hemisphere" (DPWS 1997: p. 39).

1828, when Thomas Mitchell began the first trigonometrical survey of New South Wales, his initial meridian was taken from the Parramatta transit instrument in consultation with Dunlop. That survey underpinned mapping in New South Wales until recent times (Rosen 2003: p. 80).

Surveyor Edward Ebbsworth, when conducting his 1887 survey of Parramatta Park, ensured that the exact location of the piers would be preserved by fixing a copper plug in the basal stone of the piers.

Brisbane was accompanied to Australia by two astronomers: Charles Rumker, who had already attained a good reputation as an astronomer and mathematician; and James Dunlop, whose great natural ability in mechanical appliances and instruments saw him identified as a suitable man for second assistant in the Observatory in an out of the way place like Parramatta. On arrival in New South Wales, Brisbane's instruments were immediately set up on piers in the Domain to allow the observation of the solstice on 21 December 1821. B

April 1822, the construction of the observatory had been completed in anticipation of the appearance of Encke's Comet, an event not observable in Europe or at the Cape of Good Hope (Rosen 2003: p. 80).

The observatory was privately funded by Brisbane and consisted of two buildings: an observatory equipped at Brisbane's personal expense; and a residence attached to it. Located about 91 m (100 yards) behind Government House, the observatory was a plain building, 8.5 m (28 feet) square by 3.4 m (11 feet) high, with a flat roof with two domes 3.51 m (11 feet 6 inches) in diameter projecting from it, one at the north and the other at the south.

On the north and south sides were five windows, three of which were in a semi-circular projection from the wall at the base of the domes.

Transit openings in the domes extended to one of the windows to allow observations of the horizon. A 0.41-metre (16 in) Reichenbach repeating circle was located under the north dome and a 1.2-metre (46 in) equatorial Banks telescope was under the south dome.

There was also a Troughton mural circle and a 1.7-metre (5+1⁄2 ft) Troughton transit instrument. A Hardy clock showed sidereal time and a Brequet clock showed mean time.

All instruments were mounted on solid masonry piers.

There was also a Fortin pendulum and two instruments for observing the dip and variation of the magnetic needle.

CONVICT LIES

O’Farrell estimates about 1.5% of these were unambiguously sent out as political offenders or participants in rebellion or conspiracy, with the great bulk of these coming in the aftermath of the 1798 Rebellion.

If crimes of agrarian discontent and social disaffection are included under the heading of ‘political crimes’, then the proportion of Irish political transportees rises to about 20%. The great majority of Irish convicts were, therefore, sent to Australia largely for petty crimes.

Theory to link back to

JOHN DEE AND THE OPTICS OF THE CRYSTAL BALL USED BY THE MONARCHY OF BRITISH CROWN

BASED ON THE PROJECTION INTO THE ASTROLOGICAL, ASTRONOMICAL TRANSITS TO CONQUER VIA USING EDWARD KELLY AS "COURT MAGE" AND THE ENOCHIAN CHESS IN THE GLOBAL CONQUEST

real scrying methods take two or more people in the spiritual court for impact, as per 2009 - 2014 when K and I had adopted the original crystal ball between us resulting in full-blown manifestations, later confirmed by Kardec spiritism sources

my spirits advise me Australia is the prime spot for HAITI 2.0 FOR THE SECOND COMING OF THE SLAVE REVOLT IF THINGS CONTINUE THIS WAY ....

note the date and time and motions of movement

note the present economic, social and political happenstance

note the pestilence that has persistence against the masses who only want freedom and peace

note the objections from the overlords through clauses like agenda 2030, and sustainable development, which are just fancy names for the "new world order". which is just a modern 'human slave agenda" decked out in bureaucratic red tape.

freedom of choice, or be denied all liberty?

look at the manipulation that occurred as a result of COVID-19 and the forced COVID-19 vaccine agenda

when will the next thing that replicates occur, and when will humanity rise against the overlords to object in the most amicable and peaceful or diplomatic way, as clearly, the violence and bloodshed aren't going to work here.

PEACEFUL REBELLION.

#john dee#crystal ball#vinegar hill#1804#rebellion#the battle of vinegar hill#australian history#haunted australia#paranormal australia#parramatta#john dee and edward kelley#thomas mitchell#rouse hill regional park#supernatural australia#haunted places in australia#ley lines#the rum rebellion#haitian revolt#slave rebellion#irish rebellion#liberty or death#calling down the lwa.#rum rebellion#crystal balls#scrying#spiritism#haitian vodou#ogun#spirts#revolt

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Defeat of Irish Royalism, 1650: ‘We are come to break the power of a company of lawless rebels who… live as enemies of human society,’

The End of the Confederate Rebellion

Source: Wikipedia

IN LATE 1649 Cromwell made overtures to the Irish Confederates, but they were couched in the language of uncompromising Puritanism. The Parliamentary general issued his declaration in response to a rallying cry from the Irish Church to the whole of Ireland to encourage resistance to the English invasion and to support the cause of the King. Cromwell proclaimed that the Irish would be treated leniently; that their lands would not be confiscated, and that there would be no judicial punishment for their rebellion. However, all the rebels heard was the unforgiving righteousness of the Calvinist godly: because Cromwell added that in order for there to be a peaceable end to the rebellion, the Catholics would have to give up their fight and their religion, their support for the king and to accept an imposed Protestant settlement on their country. Perhaps Cromwell thought his declarations reasonable in the context of a bitter civil war that had allegedly seen massacres of Protestant settlers by the rebels. However, to the supporters of a nine year nationalist rebellion rooted in the Roman Catholic religion, his words were those of conqueror to the vanquished.

So the war continued. In January 1650, a reinforced Cromwell continued his campaign of reducing Royalist and Confederate strongholds one by one. In contrast to the atrocities committed at Drogheda and Wexford, and to Cromwell’s subsequent baleful reputation in Ireland, he offered generous terms to defenders, permitting them to march out of surrendered towns and castles under arms and with banners flying. This way the Commonwealth forces were able to capture Fethard, Cashel and Cahir in quick succession. The route was then open for a march on Kilkenny, the capital of the Confederate rebellion. In March 1650, Cromwell invested the city. After five days of negotiations, the Confederate commander agreed to surrender the city and the garrison vacated Kilkenny, marching away with full honours and the centre of the rebellion was, rather suddenly, in English hands.

With the loss of Kilkenny, Ormond knew that the Royalist cause in Ireland was almost spent, but if Charles I’s former Lord Lieutenant despaired of now being able to aid his sovereign’s son to the throne, Cromwell himself was not so sanguine. He believed the danger of invasion from Ireland remained the greatest threat to the longevity of the upstart Commonwealth, for all Charles II’s rumoured courting of the Scots. Despite the absence of any rebel field army worth the name, the Confederates continued to hold several strongholds, all well garrisoned and therefore, from Cromwell’s perspective, comprising the core of a potential Royalist revival. The Parliamentary general resolved not to leave Ireland until each and every hold out had been reduced.

Cromwell began his campaign with Clonmel, a walled city in the south under the command of the formidable Hugh Dubh (“Black Hugh”) O’Neill, a veteran on the Catholic side of the Thirty Years’ War, known for both his military skill and his strategic cunning. O’Neill led an experienced garrison of 1500 rebels and had the support of the townspeople to resist the invaders and so when Cromwell arrived before the walls of Clonmel on 27th April and offered terms, Black Hugh refused to negotiate and a siege commenced. Cromwell concentrated artillery on the hills overlooking the city from the north and began a bombardment. Morale within the town however remained high and O’Neill sent several sorties out to attack the besiegers and disrupt their supply and communication lines. The rebel commander lived in hope that if he could tie down the Commonwealth forces long enough, Ormond may yet put a Royalist army into the field and come to his relief.

This was a folorn hope, but Black Hugh made the best of his situation. By the middle of May, the English gunners had made a major breach in Clonmel’s walls. It seemed the fall of the city was imminent and on the 17th, Cromwell ordered his infantry to advance into the breach. Unknown to the Parliamentary commander, O’Neill had turned this tactical disadvantage into an ambush. He had his men construct a makeshift wall around the edge of the breach, and secreted canon and sharpshooters within the new defensive line. As Cromwell’s forces surged forward, they were met by withering artillery and musket fire that cut them down in their droves. After an hour of one-sided combat, over a thousand New Model troopers lay dead or dying in the killing ground. When Cromwell arrived personally to oversee what he expected to be the final street by street battle for the town, he found his men in retreat and Clonmel still defiant. Black Hugh had arguably inflicted the only defeat suffered by Cromwell in his lengthy career fighting in the many and varied British Civil Wars.

However, O’Neill knew the chances of repeating this success were limited. With ammunition and food running low, and the continuance of the bombardment assured, he took the view that Clonmel was impossible to hold. That night he and his remaining soldiers slipped out of the city and made their way to Waterford. On the 18th a frustrated Cromwell took the surrender of the city from the town’s mayor - a victory perhaps, but one that probably felt like a defeat. Nontheless, however hard won, the taking of Clonmel effectively ended Royalist hopes in Ireland and Charles indeed gave up the slim hope that Ormond’s forces could be the vehicle for a restored monarchy. The Rump Parliament agreed. Their nervousness was focused entirely now on the danger from Scotland and they wanted their all-conquering general home, despite the fact the Catholic rebellion was not fully suppressed. On 29th May, Cromwell left Ireland and returned to London to a hero’s welcome. The task of stamping out the last of the Catholic rebellion, which would carry on for a further two years, fell to Cromwell’s fellow Grandee, Henry Ireton, who would eventually die in this, his last campaign in the Parliamentary cause.

Cromwell could count his Irish campaign a success. In just nine months he had destroyed Royalist hopes in Ireland and fatally crippled the Confederate rebellion but at lasting cost to his reputation. If the atrocities at Drogheda and Wexford were exaggerated and there is also evidence elsewhere of Cromwell’s leniency and political skill, there is no doubt the behaviour of the general and his army to the Irish was brutal and contemptuous in equal measure. And if there is little or no evidence of deliberate wholesale massacre of non combatants in the two notorious sieges, the cold-eyed killing of the entire garrisons of each city, whether the men were fighting or surrendering, is enough to justifiably condemn Cromwell as a callous military murderer for posterity.

1 note

·

View note

Note

"Starscream mpreg is also very important to history" So true

Here's an wider out of context view of that

#disclaimer: i was talking about transformers beforehand#i did not randomly insert starscream mpreg into the irish rebellion!!!#asks#edit: what will be my 50th post the comic i put time and effort in or irish pregnant starscream#this post is more significant to my blog of course

34 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi! So this is gonna sound weird, but I’ve kinda been learning about Irish history backwards? Like, I started with the Troubles (bc of family involvement), then back to the 1916 rising which got me more interested in the people involved which took me further back and etc etc. I know I’ve been doing it “wrong” but I’m just starting to come up to the 1798. Do you happen to have any recommended readings or particular persons of interest to read? Any collections of primary sources would be more than welcome!

Secondary sources I would recommend:

The Year of Liberty by Thomas Pakenham - about the rebellion in general

The People's Rising by Daniel Gahan - about the rebellion in Wexford

The Summer Soldiers by ATQ Stewart - about the rebellion in Ulster

Wolfe Tone: Prophet of Irish Independence by Marianne Elliott - about Wolfe Tone

The Life and Times of Mary Ann McCracken by Mary McNeill - technically this is just about Mary Ann but I think it's pretty good for Henry Joy McCracken too because there aren't many biographies of him

Orangeism in Ireland and Britain 1795 - 1836 by Hereward Senior - obviously exercise caution on whether or not you think you can mentally handle this subject but book about loyalism during 1798

Castlereagh: War, Enlightenment, and Tyranny by John Bew - about Lord Castlereagh

2 things that I would also recommend reading about for context are the French Revolution and the British radical movement of the late 18th century. for the French Revolution 1 book I would say is good is Liberty or Death by Peter McPhee and for the British radical movement... the book The English Jacobins by Carl B Cone does a good enough job

Primary sources:

The Memoirs of Theobald Wolfe Tone by Theobald Wolfe Tone - title is pretty self explanatory. It's Tone's account of his own life + his diary

The United Irishmen, Their Lives and Times by RR Madden - this is considered to be the 1st history of the rising & was written with the help of many people who lived through it, so it includes a lot of first hand accounts. HOWEVER. beware that Madden was your archetypical mid 19th century Catholic Irish nationalist and the bias created due to that shows through in every single part of these books

Memoirs of the different Rebellions in Ireland by Sir Richard Musgrave - this is another very early history of the rising, also written with the help of people who lived through, also including a lot of first hand accounts. HOWEVER. Musgrave is like Madden's Orange counterpart in that this book is also wildly biased and should also be read with a degree of caution

Personal Narrative of the "Irish Rebellion" of 1798, Sequel to Personal Narrative of the "Irish Rebellion" of 1798, and History and Consequences of the Battle of the Diamond by Charles Hamilton Teeling - 3 accounts of politics in Ireland in the 1790s written by someone who as a young man led the Catholic paramilitary the Defenders

The Drennan letters (a collection of letters that Belfast doctor William Drennan and his sister, Martha McTier, wrote to each other between the 1770s and 1820s), if you can find them, are another great primary source on both the United Irishmen & on what life was like back then in general, as are the McCracken letters, which I know are available free online somewhere I just can't remember where exactly I got the pdf from

There are a lot of them but if you're interested in primary sources you might also read some of the political pamphlets/books that were going around back then -- the most famous that come to mind in this context are Wolfe Tone's Argument on Behalf of the Catholics in Ireland, Thomas Paine's The Rights of Man, and Edmund Burke's Reflections on the Revolution in France but there are wayyy more than that and at least some of them are on the internet archive

200 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hozier sings in English, lucky for me to understand him, lucky for him to make good money, but remember the violence that made our world Anglophone, the Gaelige of his homeland will always sound foreign, a poet cut off from his mother tongue.

A butchered tongue is a tragedy, more poignant when the message comes from such a blessed tongue, a talented singer and lyricist.

What other voices have been lost.

#hozier#butchered tongue#unreal unearth#dantes inferno#seventh circle of hell#gaelige#anglophone#anti colonialism#irish history#irish language#british commonwealth#imperialism#violence#indigenous people#lamguages#wexford rebellion

119 notes

·

View notes

Text

History of Harold's Cross, Dublin

One explanation of the origin of the name Harold’s Cross is that it is derived from the name given to a gallows, which had been placed where the current Harold’s Cross Park is situated. Harold’s Cross was an execution ground for the city of Dublin during the 18th century and earlier. In the 14th century the gallows there was maintained by the Archbishop. Harold’s Cross stands on lands which…

View On WordPress

#1798 United Irishmen Rebellion#1916 Volunteers#Archbishop#Dublin#Gallows#Harold&039;s Cross Green#History#History of Ireland#Ireland#Irish History#Kimmage#Mount Argus Church#Padraig Pearse#Rathfarnham#Rathmines#Robert Emmet#Sarah Curran#The Pale#Whitechurch

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

...sound of rebellion ...

Rory Gallagher's Sunburst 1961 Fender Strat guitar

#sound of rebellion#famous guitar#fender strat#fender#stratocaster#guitar#listen out loud#rory gallagher#debut album#irish#musician#guitar player#songwriter#the greatest guitarist you've never heard of#Spotify

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

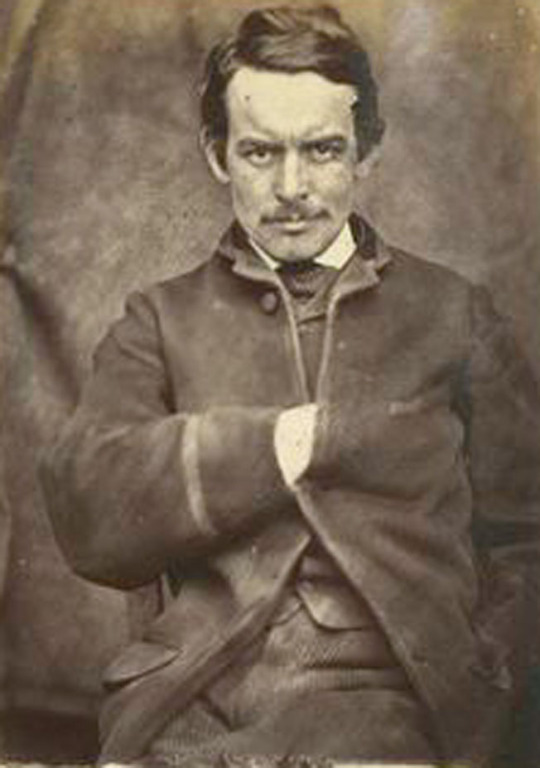

Mugshot of Denis F. Burke, former Colonel of the 88th New York (part of the Irish Brigade), while he was imprisoned at Mountjoy Prison in Dublin for aiding the Fenian movement against British rule in Ireland.

#american#history#irish#ireland#fenian#rebel#rebellion#mugshot#19th century#1860s#irish brigade#new york#dublin#union#federal

44 notes

·

View notes

Note

Don't know the timeline, but maybe the war was something Arthur inherited from Uther, and he couldn't just stop it because all of the nobles involved were very in favour of it?

Frankly, war is very lucrative for the nobles. It's how they got to high up the taxes from the populace. Many aren't happy with the quick way Arthur accepted a truce as soon as the Irish asked for it.

47 notes

·

View notes

Note

I appreciate the counter-revisionist spirit of the Puritans but it doesn't fully acknowledge the bad with the good, right? The Puritans were genocidal towards Native Americans (during Metacomet's War), supported slavery, and then there's the brutal campaign in Ireland under Cromwell that ended with many poor Irish reduced to indentured servitude.

So I think this is a very fair critique. If I'm going to take the position that we have to acknowledge that tumblr's faves the Vikings and Caribbean pirates were heavily implicated in slavery, I think it's incumbent on me to recognize the intense violence that was also part of the Puritan legacy. Because I think there's a direct line that can be drawn towards the violence of King Metacomet's War, the violence of Cromwell's campaign in Ireland, the violence of the English Civil War, and the violence of the wars of religion on the European continent, in part because in some cases you literally had veterans of one conflict fighting in another, and also because I think it points to the ways in which these conflicts fit a rather conventional pattern of 17th century warfare. This is not to say that the Puritans' actions were moral, but rather that they weren't unusual.

First, these wars tended to involve targeted attacks on civilian populations, the tendency for both sides to engage in escalating reprisal atrocities (this is not meant as a minimization tactic: if you look at the actual conduct of these wars, there are no good guys as pretty much everyone gives into the temptation to massacre civilians in revenge), and high casualty rates.

Second, they tended to involve seizure of land and the simultaneous pushing out of existing inhabitants and intended settlement of co-ethnics/co-religionists. These wars were intended to reshape borders and frontiers in ways that we today would consider ethnic cleansing.

Third, they were also rather complicated conflicts. Metacomet's War wasn't just a Puritan attack on the Wampanoags, but a complex affair of the Puritans and nine different First Nations tribes who fought both for and against the Puritans and one another - indeed, arguably two of the biggest victors of Metacomet's War were the Mohawk and the Wabanaki. In Ireland, you had the Catholic Confederation who had originally rebelled against Charles I and warred against the largely Scottish Ulster Protestants but who also allied with Charles against first the rebellious Scottish Covenanters and then the English Parliamentarians, you had Scottish Covenenanters who sent armies into Ireland to protect and revenge their kinsmen, you had a Royalist army under the command of an Irish lord who was tasked with putting down the Confederation and then recruiting the Confederation, and then you had Cromwell's New Model Army. (This is why, for example, most of the victims of the massacre of Drogheda were English Royalist soldiers rather than Irish Catholic civilians.)

Finally, a couple points about slavery. First, it is true that slavery was practiced in Puritan New England, but unlike in Virginia, New England was a society with slaves rather than a slave society. Hence why you had odd scenarios, whereby in New England slaves had the right to jury trials - a loophole that enlaved people would exploit starting in the mid-18th century to launch freedom suits by which they would petition the court for manumission.

Second, I would strongly advise that you be very, very careful about the topic of Irish indentured servitude, because the "Irish slaves myth" discourse devolves very quickly into white supremacist propaganda, and there is a nasty tendency for Irish republicans to be extremely cavalier with racist tropes. For example, Sean O'Callaghan, the author of To Hell Or Barbados: The Ethnic Cleansing of Ireland not only conflated indentured servitude with chattel slavery, but invented a brand new historical libel when he claimed that Irish women sent to Barbados were systematically forcibly bred to African men. (Incidentally, for some misbegotten reason Wikipedia's page on the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland cites O'Callaghan as a source.) Despite the fact that this obviously trades in racist myths of black men as sexual predators, other authors repeated the claim and then it went viral online.

Not only is the conflation of temporary indentured servitude with chattel slavery something that a lot of white people use to minimize the history of anti-black racism similar to how narratives of immigrant struggles and upward mobility are used to minimize the impact of slavery and racism (essentially, we white ethnic group suffered and got over it, why can't you), but it also becomes this vector for online radicalization by white supremacists, neo-Nazis, and conspiracy theorists as memes circulate on social media forums - with the hope being that you gradually draw people from Facebook (and Tumblr?) to Infowars to Stormfront.

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

Men of the Irish Legion in Napoleon’s grande armee. These troops were largely of those who escaped after the failed 1798 rebellion in Ireland. The legion was meant to be the core of a force to invade England and Ireland under Napoleon in 1803, but the naval Battle of Trafalgar ended any seaborne plans of invasion.

The Irish Legion continued service in the Grande Armee, serving in the Netherlands, Peninsula War, and the 1813 German campaign.

#history#miniatures#military history#historic miniatures#napoleon#irish history#ireland#irish legion#1798 rebellion

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

PUT NETANYAHU, BIDEN, AND VON DER LEYEN IN THE HAGUE

#free gaza#gaza strip#irish solidarity with palestine#free palestine#palestine#gaza#news on gaza#al jazeera#boycott israel#israel#the hague#Extinction rebellion#international criminal court

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Year of the French (1982)

Still from: Redcoats Return to Killala, 1981, RTÉ Archives.

I don't have much hope, but maybe someone can help me with my personal white whale, which is the TV series The Year of the French (1982), an Irish/French/British co-production based on the novel of the same name by Thomas Flanagan.

While the novel and the soundtrack, recorded by The Chieftains, are easy enough to access, the series itself remains elusive, to the point that it never saw a DVD, let alone a digital release.

From old forum discussions on IMDb, I gleaned that the series was repeated a couple of times and that some people possess home-recorded VHS-copies, which gives me some hope that a) it actually exists, and b) someone may have digitised the series after all.

Does anyone here know more about The Year of the French, or how to find/access it?

#the year of the french#history#irish history#question#18th century#rebellion of 1798#1798 rebellion#the chieftains#irish music#tv#tv shows

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Samuel neilson approving this for printing after another long day of the united irishmen encouraging individuals to commit acts which will both directly and indirectly tend to aid the king's enemies:

#'we would never encourage anyone to rebel' say men who will all be imprisoned for starting an armed rebellion within 5 years#french revolution#irish history#reading#jory.txt

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jozef Gabčík movie ver The blond beast killer.

(I've been abandoned this for months but able to finish it even I almost won't to continue it. Tempting me for bought Cillian papa fanart play on ww2 movie kkk)

NOTE: NON POLITICAL THINGS!!

Link : https://strafervii.carrd.co/

#anthropoid#operation anthropoid#ww2#ww2 movies#ww2 resistance#cillian murphy#Cillian Murphy fanart#fanart#Jozef Gabčík#Czech rebellion#historical movies#irish actor#movie poster#cillian murphy fans#Spotify

6 notes

·

View notes