#historical garments

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

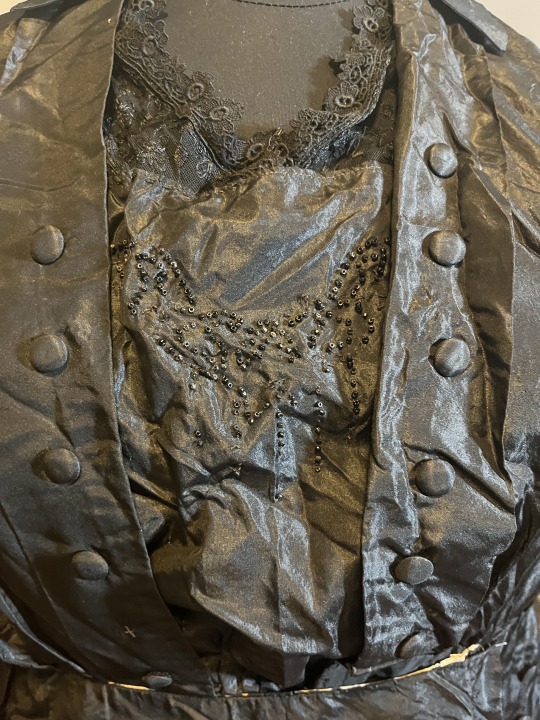

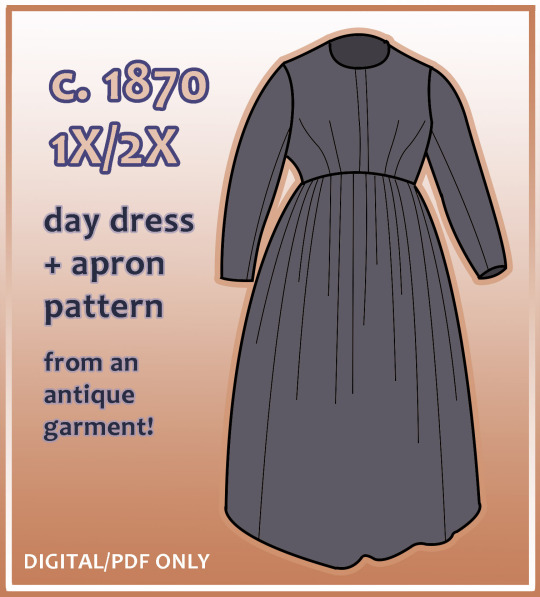

The two newest patterns that I have in testing right now, based on antique plus-size garments...

c. 1909 eleven-gore polka-dotted cotton day skirt The size as-is is a 37”/94cm waist with 60”/152cm+ hips, and ungathered it’s a 46.5”/118cm waist. It was made for a very short person, so I’ve provided the original length (32”/81cm) as well as an extended version (40”/102cm) on the pattern for whatever you need. On Etsy here.

c. 1915-17 silk day dress with beading This has a 60” (152cm) bust and 45.5” (116cm) waist and was made for a relatively tall person. On Etsy here.

Both are now up on Etsy!

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

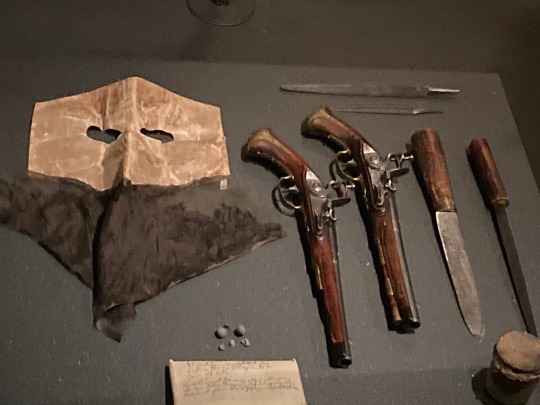

Gustav III's Masquerade Costume

Worn During His Assassination At The Royal Opera House, Stockholm

Midnight, 16th Of March, 1792

The Royal Armoury

Stockholm, Sweden

#gustav iii#masquerade costume#18th century fashion#extant garments#historical garments#highwayman costume#political assassination#regicide#royal armoury#stockholm#sweden

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ball gown, Au Bon Marché (1905-1906)

via Museum für Kunst & Gewerbe Hamburg

#historical fashion#fashion history#dress history#history of fashion#ball gown#edwardian fashion#edwardian aesthetic#edwardiana#edwardian dress#20th century fashion#early 20th century#early 1900s#extant garments#coquettecore#pinkcore#1900s#1905#1906#1900s style#1900s dress#e

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

I hate "it's not trying to be accurate!" arguments for historical fiction or historically-inspired fantasy clothing choices that just. don't make sense logistically

why is that girl in Br*dgerton tightlacing her stays? what is she reducing- her upper ribcage? not only can you not tightlace in those (hand-bound eyelets can't usually take that strain, in my experience), but there's no reason to because your waistline is under your boobs. and unlike most of the series, they actually commit to the empire waistline for the court presentation gowns. small waists don't matter when NOBODY IS SEEING YOUR WAIST

why no chemise, in so many productions? fantasy/lack of concern for accuracy can't make things not chafe. chafing is not a matter of accuracy; it's a physical reality. did a wizard give everybody in the kingdom Anti-Chafing Spells?

just because you don't WANT a linen underlayer beneath a medieval tunic doesn't mean sweat won't get to outer garments and damage them- or make them need laundering, which weakens the fibers -at a time when all clothing is handmade, custom-fitted, and created from hand-woven fabrics and thus a HUGE investment

you're not just throwing accuracy to the winds as a design choice; you're ignoring How Textiles And Bodies And the Realities of Your Technology Level's Fabric and Laundering Capabilities Work

#historical fiction#fantasy#clothing history#people cannot treat their garments like modern polyester fast fashion pieces if they're NOT#if NONE OF THOSE THINGS EXIST IN YOUR SETTING#who is MAKING IT who is DOING THE LAUNDRY why has NOBODY DEVELOPED A WAY TO AVOID DISCOMFORT#IF CERTAIN EVERYDAY GARMENTS COULD POTENTIALLY CAUSE IT#(that one is still about Br*dgerton and also The Al*enist)#(Oh If Only Women Didn't Have To Be Chafed By This Garment They Basically All Wear! well. um. bud I have a huge surprise for you)#(called 'they thought of that long before they started wearing them in that form')

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

I have some gorgeous shot taffeta that is just waiting for the right project to come along. Every time I see work like this, I want to start stitching

63K notes

·

View notes

Text

1845 green silk brocade evening dress with a white floral pattern, with a pleated skirt and boned bodice, that is shown here displayed with a lace bertha collar. Kyoto Costume Institute collection.

#fashion history#vintage fashion#victorian fashion#historical fashion#clothes#extant garments#green dress#sage green#ilovethis

563 notes

·

View notes

Text

Overview of Rococo Fashion

I mentioned in a post three god damn years ago I was writing this, but in my defense 1700s was a hell of a century.

18th century was a weird and interesting period of western fashion. It was a time of extreme inequality in Europe and even more extreme exploitation of the rest of the world through massive colonial expansion. Fashion became also extreme. The wealth amassed by the elite translated into diverse styles and complicated dress codes which required multiple changes in clothing thorough a day. Imperialism also meant increasing centralization of power and authoritarianism. In fashion this led to interesting dynamic, where the courts, trying to control the increasingly rich and powerful elite, set restrictive and archaic dress codes, while the aristocrats continued to experiment with new fashions in their casual styles. The cultural capital shifted from formal court events to the casual gatherings among the fashionable aristocrats. Salon parties, picnics, morning gatherings and even dressing up became important social events.

All of this makes the fashion of the period very hard to grasp. I have yet to find any good overview of it. So after trying to figure out this period for a long while now, I will attempt to give my own overview. Like any even remotely succinct overview, it will be incomplete. I'll focus on the high society women's fashion and the two central players in the fashion of this period, France and Britain. I define this fashion period (which is really late Baroque plus Rococo) as starting from the rise of mantua in 1680s and ending to the French Revolution in 1789, but this post will only cover the fashion up to roughly 1770. Things changed a lot during the 1770s in France especially (which was the fashion capital) and numerous new types of fashionable gowns popped up, so this would be way too long (more than it is already) and it's a natural place to split this. (I will make a second part to this but no promises on doing it quickly.) The different types of gowns were used for different purposes and often evolved fairly separately from the other types of gowns, so I will structure this around them. This approach was the only one that made sense to me so I hope it makes sense to you too. I won't go through every single type of gown, since there's too many. For example I will skip all the numerous short gowns and jackets, which were always common informal wear, and I'm focusing less on different types of negligé. Just know they and others were there. I have split this in a very vibes based eras named after the most fashionable thing at the time.

Negligé, dishabillé, half dress and full dress

But first, to understand the fashion of 18th century, we need to first understand the social life of the high society and it's dress codes. The highest level of formality was expected in court, and courts set their own dress code, which needed to be complied with. It functioned as a sort of invitation pass as court was theoretically open, but you needed to wear extremely expensive clothing to get in. Outside court the most formal events were formal balls, in which full dress (formal dress) was used. Full dresses followed fashion and were quicker to change than the court's dress code, so they weren't necessarily the same as court dresses. Less formal events were things like private dinner parties. In those half dress (semi-formal dress) was used. Then there were informal social events, like tea parties, picnics and salon gatherings, where dishabillé could be used. Dishabillé means undress, and while from modern perspective they were fully dressed, at the time it meant a type of informal dress that was used inside the home, but which was not too casual to be improper outside home either. Dishabillé was also used when otherwise going outside, not to an event, but for example visiting a friend or a relative.

At home dishabillé could be used for example to have dinner with family. Dishabillé negligé was an even more informal dress and not used outside home, except for perhaps a private morning walk. Usually it was used in the morning, but could be used till dinner on a quiet day. It could be used to receive guests or sometimes for receiving the small intimate gatherings too. It would be used with stays (could be lightly boned or worn loosely) or jumps and petticoat. Negligé was the most casual wear which was not literally underwear. Negligé was worn over the night chemise, sometimes with minimal structural garments. Negligé was used inside bedchambers or dressing room (usually the same). In the 18th century toilette, dressing up for the day, had become a very intimate social event. The upper class hair especially took quite a while to powder and put up fashionably, so while they were being dressed by the servants, they might just as well receive close friends, family members or even lovers. Sometimes women might receive close friends also when reclining in bed in their negligé.

Only court dress had explicit rules and even those were not always followed, so what was considered full dress, half dress, dishabillé or negligé was not very strict. So when I mention later what type of gown was considered to fit what sort of dress code at different points in time, these are not hard rules and people did bend them based on their taste and even politics. Some day I'll want to go deeper into this and go through some of my research of paintings and fashion plates.

1680s-1710s: The Mantua Era

Mantua gained it's start in 1670s, but became broadly fashionable in 1680s, so that's where I'll properly start. At the start of 17th century first colonial trading companies, the Dutch and the British East Indian Companies, were created and through the century they had been establishing trading posts in Asia. As the century progressed they became increasingly aggressive in their competition over the trade leading to Anglo-Dutch wars. It lead to a race to extend colonial control over the local authorities and in 1680s the British East Indian Company colonized Indian subcontinent. Increasingly available Asian luxury products led to a fascination with Asia. This fascination became justification for colonialism in the form of Orientalism. Orientalism constructs an Orient, which is fetishized, mystical, primitive and barbaric at the same time, to dehumanize colonized people and justify their subjugation. It became a very significant force in the fashion of whole 18th century.

The rigid or stiff-bodied gown

Also known as rode de cour and grand habit in France. Most of the 17th century the basic garment in women's fashion was the structured bodies and a skirt, either attached together or separate as was the case increasingly towards the end of the century. Bodies were heavily structured with boning and the primary structural layer and were used as both outer and under garment. In formal occasions the gown had rigid bodies which could be separate from the skirt but always matching. When mantua became the fashionable dishabillé in 1680s, the more formal gown started to be called rigid or stiff-bodied gown. The new silhouette was conical and stiffer. The skirt had a long trail and was open at the front and pulled to back to expose the usually contrasting petticoat. Later, especially for full dress, petticoat would usually be matching. The petticoat was also fairly conical, narrow and stiff, not full and flowing like in the mid century. It was a sort of return to the Elizabethan aesthetics of mid and late 16th century England and France after the fuller and softer aesthetics of the height of Baroque.

French fashion plate from 1683. Detail from c. 1715-1720 painting "Madame de Ventadour with Louis XIV and his Heirs".

Robe de chambre

Also called wrapper, dressing gown and nightgown. Robe de chambre became the fashionable negligee in late 1600s following the style of men's informal robe, banyan, which had become fashionable in the mid century. Banyan was of Orientalist origin and imitated Japanese kimonos. Banyan name came from Hindu merchants and was also called the Indian nightgown in Britain. In the eyes of Orientalism the whole continent of Asia (and North Africa) were all interchangeable. Banyan represented intellectualism and open-mindedness, connecting to the view that "the Orient" possessed "ancient mystic wisdom", which in the hands of the "Rational Western Man" could be turned into intellectual enlightenment. For example philosophers and intellectuals often got their portraits in banyan. Robe de chambre was like banyan, a long loose gown of rich (often imported) material. As it became more fashionable and more richly made, it graduated to dishabillé negligé. As negligé it was often worn over a night shift, when getting dressed, but as dishabillé negligé it was worn over stays and petticoat. Then it was often belted at the waist to give definition to the silhouette. It could be closed, hiding the stays and petticoat, or they could be left visible, in which case they needed to be fashionable as well. The stays evolved from the undergarment bodies and therefore weren't considered strictly undergarment, like the later corset.

Robe de chambre or dressing gown continued to be used as negligé and dishabillé negligé thorough the century only changing a little (for example in patterns and sleeve shapes) with fashions.

French fashion plate from 1685. French fashion plate from 1695.

Mantua

During 1670s increasingly formal forms of robe de chambre emerged and started to be worn as dishabillé. In addition to being belted, this robe was paired with a fashionable petticoat and the skirt was tied back like the formal rigid gowns to follow the fashionable silhouette and that way making it more formal. It became a new type of dress, mantua. Robe de chambre continued to be used as dishabillé negligé. Mantua was basically constructed the exact same way as robe de chambre, only really differing by having a long train. Early mantuas in 1680s and before were pinned closed at the front to create a sort of closed bodice mimicking rigid gowns. By 1690s though the bodice would be usually left open in a v and a stomacher in contrasting colour would be attached to the stays to cover them or stays of contrasting color from fashionable fabrics were used, usually for more casual cases. By the end of 17th century the petticoat was usually made from the same fabric as mantua, but the stomacher was still often from contrasting fabric. Around that time mantua also graduated to half dress. It was still worn in less elaborate forms as dishabillé though.

Mantua's success arguably laid in it's adaptability. It was loose, simple in cut and didn't need tailoring, so it was quite easy and cheep to make, while it could still be fitted to the fashionable silhouette with pins and belts. This made it very easy to fit comfortably to the changes in body and to other people with different bodies. It could even be fitted to new silhouettes just by changing the structural under garments. The quick and cheap construction also made it possible for rich upper class women to gain very large wardrobe and therefore develop the very complicated dress codes the 18th century would be known for.

British woolen extant mantua from late 17th century (probably around 1680s). French portrait of Anne de Souvré from 1693.

1720s-1730s: The Robe Volante Era

Rococo style started dominating the arts, especially in France, but would influence the whole western world. In fashion it meant brighter colours, lighter and fuller fabrics and lusher details. Because of the rivalry between the British and French empires, the English took a fairly oppositional stance on the very French Rococo style. This led to a gap between French and English fashions. French fashion leaned to the decadent opulence, while English fashion was more restrained and somber. Rococo was a decorational style related to the broader Classicism, and the English fashion leaned more towards "pure" Classicism.

Rigid gown

By 1720s mantua had firmly usurped rigid gown as the fashionable full dress. However, the courts still clinged to the traditional rigid gowns, even though by that point it was clear mantua had come to stay. The roundness had come back to the skirts to display the fullness of the fabrics. The skirt had started growing again in the beginning of the century and hooped petticoats had started to enter back into the wider fashion after almost a century, probably again from Spain, where they had stayed as the stable of court fashion through the whole 17th century. It kept growing through 1730s into massive round cake-like proportions. The sleeves had barely changed at all from previous decades.

Portrait of Maria Lescynska, Queen of France, from 1726. Portrait of Princess Amelia of Great Britain from 1728.

Mantua

As mentioned, mantua had became the full dress. Less elaborate mantua was still also used as half dress, but the dishabillé versions had been usurped by new types of gowns. The formal mantuas had increasingly their pleats stitched to create more fitted appearance. Skirts of the formal mantuas changed along rigid gowns. Hoops (or that large hoop skirts) weren't necessarily used with half dress.

British extant mantua from 1735-1740. Detail from French painting "Adélaïde de Gueidan and her sister at the harpsichord" from 1735-1740.

Robe volante

As mantua was turned into increasingly elaborate and formal gown, a new less formal version was developed from it. Or rather it also developed from a dressing gown as a slightly more formal version like mantua had before it. Robe volante or battante was unbelted mantua. It was closed at the front (usually stitched or closed with buttons) often leaving a similar v as mantua to reveal a stomacher, but sometimes closed so far it mostly covered the stays. It was pleated at the back, but the pleats were left loose, which was called sack back. Overall it was very loose flowing dress and combined with a large skirt the effect, especially when sitting, was like drowning in an opulent sea of fine fabric. In France it became extremely popular first as dishabillé, but eventually it was used as half dress as well.

Today it might feel a little weird that this very covering and not at all formfitting garment was seen as quite indecent in public. But at the time structural garments, especially stays, which shaped the body and concealed it's natural form, was needed to be considered dressed at all. Loose unfitted garments were already associated with negligé, but then covering the fashionable form with a garment like that left it obscured weather they were even wearing stays. The reaction was basically "what if she's naked under her clothes????" This was also of course related to Orientalism. In many Asian and North-African cultures (especially Arab and many other Muslim cultures) women (and everyone else) wore loose covering gowns, and there was fetishistic fascination among Europeans about their "exotic beauty" under the clothes. Both of these associations fed each other. So young fashionable women were then sometimes suspected of promiscuity for wearing robe volante in public. Occasionally these accusations were justified by claiming they could be hiding an extra-marital pregnancy under the loose garment, even though that seems quite impractical.

French extant robe volante from c. 1730. English portrait of Mrs. Elizabeth Symonds from 1740.

English gown

The English upper society, being more prudish and restrained, made their own version of robe volante. It was otherwise basically the same, but the pleats in front and back were pinned like in mantua. Since the skirt portion was closed at the front it was basically round gown. Sometimes belt was also used, or an apron. The v opening on the bodice usually had ribbons, sometimes pleating, to keep the robe in place. This English version was much more toned down than robe volante. It was usually made of plain single color fabric and white neckerchief stuffed under the ribbons of the v-opening or plain, often white, stomacher. There were a little more showy versions of it with elaborate patterned fabrics. For finer dishabillé round gowns the pleats were sometimes stitched to their place like mantua's pleats started to be stitched. The English did still use robe volante, but it seem to have stayed more in the dishabillé negligé (or at most dishabillé) category, while the English version of it was used as dishabillé and half dress.

British extant gown from c. 1725. Detail from British painting "Wedding of Stephen Beckingham and Mary Cox" from 1729.

English nightgown

In 1730s another version of the English gown became popular, it was basically the same, but the skirt was open at the front to reveal simple, often quilted, contrasting petticoat. The terminology is hard to pin down often in this period, but I think this version of the English gown specifically was called nightgown. It was basically robe de chambre, but pinned and belted like the other English gown. It seems to have started as the new dishabillé negligé as round gown was increasingly used as dishabillé, but it would quickly increase in formality.

The English gowns with stiched down pleasts in the back as well, possibly both type of English gowns, came to be known as robe á l'anglaise in France.

British painting "Portrait of a Woman Seated beside a Table" from 1730s. French painting "Le lecturer" from 1725-1750.

1740s-1760s: The Robe á la Française Era

This is the peak Rococo fashion era and is usually what people think when they think of 18th century fashion. Extreme fashions became popular and the gap between the elite and the common people became even more apparent in fashion and in other areas of life. This was fertile ground for political upheaval, and revolutions in US, Latin America and France would follow. The extremes therefore, even in fashion, could not last very long.

Rigid gown

By 1740s rigid gown was well passed it's time as fashionable garment and supplanted from it's place as the court dress in Britain. In France though it continued to be the robe de cour in Louis XV's court till his death in 1774. Louis XV tried to keep control over his aristocracy, even though the center of high society had increasingly shifted to the salons of Paris out of Versailles. Robe de cour adapted to the new fashionable silhouette of the mid century - the extreme wide box-like skirt frame -, but continued to be otherwise very similar in style as earlier in the century.

Portrait of Marie Leszczyńska, Queen of France, from 1747. Portrait of Princess Henriette of France from 1754.

Mantua

The British court had less authoritarian power than the French counterpart, but it was just as conservative, so when it finally accepted mantua as the formal court dress, it was already going out of fashion. From 1740s onward mantua was relegated to court gown. Like the French robe de cour, it also adapted the new fashionable boxy wideness.

British extant court mantua from c. 1750. British painting of David Garrick and Hannah Pritchard from 1752.

Robe á la française

Robe á la française, or the French gown or saque or sack or sack-back gown, replaced robe Volante as the fashionable deshabillé and half dress. Despite it's name, it may have gained it's beginning in Britain in a roundabout way. English gown was a more fitted and conservative version of robe volante, but early in 1740s, when robe á la française had not yet gained popularity, a new English version of robe volante became popularised in Britain. Like in English gown the pleats on the front were fitted, however, the pleats on the back were left unfitted and hence it became a sack-back gown. I'm not sure which came first, the robe á la française in France, which had fitted pleats on the front of the bodice, sack-back and was open at the front, or the English version, which only difference was closed front. I suspect the latter, since I have found more early examples of the closed English version, and it's sort of transitional link between robe volante and robe á la française, and I haven't found any French examples of the closed variety.

Regardless, early on robe á la française was a relatively simple, but it quickly went from dishabillé and half dress to half dress and full dress, making mantua obsolete outside the English court. In 1750s it had become the default formal wear outside courts in both France and Britain and grew increasingly opulent. The sleeves also turned more fitted, while the cuffs grew and gained more layers of ruff and lace.

British portrait of Mrs. Wardle from 1742. French extant gown from c. 1755-1760.

English gown

The open English gown was also adopted by the French as dishabillé and increasingly as robe á la française grew in formality, as half dress, like it was used in Britain as well, though it was more popular in Britain. It followed the same trends too, especially in it's half dress form. Dishabillé version of the garment continued to be quite simple, worn with less structuring and otherwise too quite similar as they were earlier in the century.

Portrait of Sarah Lascelles from 1749. British extant gown from 1770-1775.

Round gown

Closed versions of the English gown were called round gown. It was possibly always called that, but as said multiple times, the terminology of this period is unclear. They stayed fairly similar as they had been since 1720s and didn't really gain popularity in France. I have not seen examples of this early type of round gown from France. The open English gown seemed to have become the more formal version and examples of round gown from 1740s and 1750s seem to be more dishabillé than half dress. Round gown in this form fell out of fashion around 1760, which gets us to the last garment we'll cover in this post.

Portrait of Mrs Iremonger of Wherwell Priory from 1745. British extant garment from 1760-1775.

Close bodied gown

Close bodied gown basically replaced round gown. The unclear terminology makes this especially hard to parse out. It seems to me that after the early version of round gown (open bodice, closed skirt) was replaced with close bodied gown (closed bodice, closed skirt), that was then called round gown as well. The trouble is that close bodied gowns existed alongside round gowns, and not all close bodied gowns even had closed skirt (this applies later as well and I'm not sure weather they were separated in terminology or were both called round gown). Close bodied gowns in fact existed basically during the whole century, but earlier they were used only by underage girls. Main difference to these earlier girl's dresses was that they were closed at the back, while the later close bodied gowns worn by adult women were closed at the front. Some of the close bodied gowns are however constructed similarly to girls' dresses, where the bodice and the skirt are cut fully separately from simple cuts, only difference being the opening is at the center front instead of center back. The close bodied gown, which clearly evolved from the English gown, instead has the distinctive pleated back seams of English gowns. Early gowns like this were clearly constructed as basically the same as the English gown, but the front was not pleated open into a v-shape, instead it was closed over the stays. This close bodied version of round gown would later become very popular casual garment everywhere among all classes and would eventually come to define the Regency fashion which followed after the French Revolution.

British extant garment from c. 1750. Portrait of Anna Dorothean Finney from 1758.

Sources

Patterns of Fashion 1, Janet Arnold

Faction and Fashion: The Politics of Court Dress in Eighteenth-Century England, Hannah Greig

5 Facts About Fashionable, Morning and Domestic Apparel in 18th Century France - MoMu Antwerp (based on a book "Living Fashion: Women’s Daily Wear 1750–1950 from the Jacoba de Jonge Collection" but I couldn't get my hands on the book)

Women's clothing and accessories - 18th Century Notebook

#historical fashion#fashion history#history#dress history#rococo fashion#18th century#18th century fashion#robe a l'anglaise#robe a la francaise#rococo#mantua#extant garment#painting#fashion plate

258 notes

·

View notes

Text

First time wearing stays

Notes, mostly for myself and whoever’s interested :

Went to a knight’s tournament today and since I haven’t gotten around to researching the early medieval dresses I’d like to make one of, I decided to finally wear my 1780’s stays in a sort of historical fantasy look that was basically just stays + one set of petticoats and a belt. (An old sundress served as a shift)

I began the day with the stays quite loosely tied because it was my first time wearing them out and I knew I’d be wearing them all day. I ended up tightening them up quite a bit two hours later and that actually ended up being way more comfortable.

The tight sensation actresses complain about in interviews (you know which ones) only happened when i slouched- as long as I kept my posture in check I didn’t feel caged in at all, even after eating.

But most fascinating to me is that after a day like this, which involves a LOT of standing, i normally get a back ache in my lower back. Today? Barely anything. (By comparison my legs are a bit sorer, I guess the combination of the stays themselves and actually watching my posture caused me to put my weight into my legs and not my lower back for once)

Finally, the muscles in my upper back are almost as sore as they are after a workout targeting that area- so fascinating.

I sewed the stays over Christmas break and was so happy to finally have a reason to break them out today and experience first hand what I’ve been watching Bernadette Banner & Co. talk about for ages. (I used the infamous redthreaded pattern and found it quite tricky as an intermediate seamstress, still very happy with my result)

Will definitely think about wearing the stays to more functions!!

Details for Historical/Fantasy Writing: Insights from a Reenactor

Writing is the main thing I do for fun, but I’m a multi-faceted lass with many hobbies, and I also do Roman reenactment. I find that by actually doing something, you learn things that aren’t possible through theoretical research alone, so here is a collection of small things I’ve noticed while reenacting that you could add to your writing for a bit of extra realism.

Loose long hair is ANNOYING. There’s a reason most depictions you’ll see of women in history show them with their hair up and/or covered, and that is pure practicality. Having hair in the way is a massive pain (this would be particularly true for working women with stuff to get done).

Repetitive tasks aren’t boring if you have someone to chat to. When we do events, I’m in the textiles tent, and as the most junior member of the team I’m the one who does the spinning. Most events are 10-4/5, and you’d think 6/7 hours of spinning (with a break for lunch) would be boring, but actually, once you’re practiced you can do it on autopilot while you natter! I’m sure this is how people managed samey tasks back in ye olde days.

Speaking of spinning, working with textiles leaves its mark. If you’ve been spinning, sewing, or weaving for a long time, you’ll feel it. It knots up your shoulders and, perhaps less obviously, the friction of fibre against your fingers can wear away just enough skin to make them tender. Thimbles help with sewing, but not spinning or weaving.

Wool is WONDERFUL. I love it. It has a reputation as being scratchy and itchy, but when it’s finely woven/spun it is fantastic to wear. It keeps you cool when it’s hot, and warm when it’s cold. It also has the fantastic property of keeping you insulated even when soaking wet, which is why wool cloaks are so brilliant.

Linen is also wonderful. Lovely against the skin and cool in the summer (but for the average person in history, it’s more expensive than wool).

Woodsmoke gets everywhere. It stings your eyes and makes your clothes and hair smell smokey. However, after a little while the smell becomes just a background thing (and you get pretty practiced at anticipating when the smoke is going to change direction so you can move out of the way). It also keeps insects away!

Cooking over a fire takes longer than you’d think. If we start an event at 10 am, that means we’ll usually be having lunch at 1-2pm. However, we do have pretty elaborate meals, and have to start the fire from scratch every day (a lot of the wait time is getting the fire to cooking embers). If your characters are cooking simple fare over a fire that you’ve started from being banked, it’ll be quicker.

You want different footwear for different purposes. Hobnails give you great footing on soft/muddy ground, but on pavement they offer no purchase at all and will KILL YOU (okay, this is slight hyperbole, but there is an account of a centurion running from grass to pavement, slipping over and getting killed by his enemies). City wear would likely be leather and clogs/pattens.

CLOAKS CLOAKS CLOAKS! They are so versatile. They keep you warm, they keep you dry, they can be a blanket or an impromptu bag. Essential equipment in my view.

#ignore my sewing lines I was using a machine and scared#should have just hand sewn#1780’s stays#historical fashion#corsetry#historical garments#18th century#stays

7K notes

·

View notes

Text

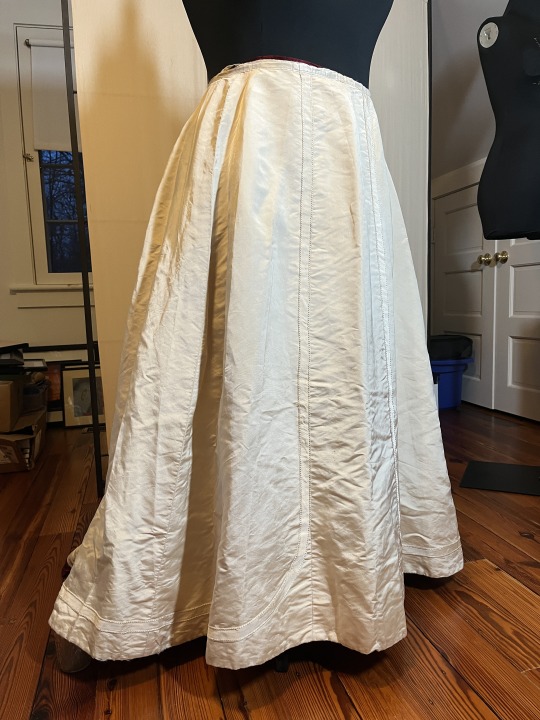

Aaand two more patterns from antique garments!

1890s silk faille evening skirt with a 34" / 86cm waist. On Etsy here!

c. 1870 cotton sateen day dress with a 50” (127cm) bust and 39” (99cm) waist! (It fits the 48”/122cm-bust mannequin very well.) On Etsy here!

I'm finishing up digitization on these, but tester slots are currently open! Once the patterns are finished, I'll put them up on Etsy with the others. <3

#22.1#23.2#plus size patterns#historical garments#historical sewing#plus size historical costuming#1890s fashion#1870s fashion

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

Met Costume Institute

Walking dress. British. ca. 1830

#fashion history#historical fashion#antique#1800#1830s fashion#1830s#extant garments#met museum#floral#this is my absolute favorite 1830s dress but I don't know if it's been posted before

776 notes

·

View notes

Text

14th century

#medieval reenactment#14th century reenactment#historical reenactment#sewing#medieval#mysca#history#medieval history#historical fashion#i’ll be on my merry way now#don’t ask where the sleeves are ok#this garment is still very much unfinished

194 notes

·

View notes

Text

Folklore garment from Romania

Romanian vintage postcard

#briefkaart#photography#folklore#vintage#tarjeta#postkaart#postal#garment#photo#postcard#historic#carte postale#romania#ephemera#sepia#ansichtskarte#postkarte#romanian

148 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ball Gown

Late 1860s

European

The MET (Accession Number: 1981.49.3a–c)

#ball gown#evening dress#fashion history#historical fashion#1860s#crinoline era#victorian#victorian fashion#red#black#silk#cotton#up close#19th century#europe#the met#this is one of those garments i would love to see mounted#to better understand shape and proportions#but i'm guessing it's chiffon so it's probably extremely fragile at this point

330 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dress, c.1900s.

Satin, velvet, silk. Worn by Mrs. Minnie Muffley (née Hopley).

via idaho state historical society

#fashion history#historical fashion#history of fashion#historical clothing#extant garments#20th century#20th century fashion#early 20th century#early 1900s#edwardian#edwardiana#edwardian fashion#edwardian era#edwardian dress#1900s#1900s fashion#1900s art#1900s style#1900s dress#e

277 notes

·

View notes

Text

In celebration of seeing the first fireflies of the season:

Furisode with Fireflies and Irises Japan, Edo period, 18th century silk crepe, paste-resist dyed, embroidery National Museum of Japanese History (photographed on display at The Life of Animals in Japanese Art exhbition at the National Gallery of Art DC in 2019)

#Japanese art#East Asian art#Asian art#18th century art#kimono#furisode#historical costume#garment#embroidery#irises#fireflies#National Gallery of Art DC#The Life of Animals in Japanese Art#museum visit#exhibition#textiles#National Museum of Japanese History

946 notes

·

View notes