#he was wearing a wetsuit in the body scene and is seen from far away in behind in the final one so i have the right to not have realized ok

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

saw jaws for the first time today and i can’t believe despite knowing so much about it through cultural osmosis i had no clue matt hooper existed and i love that funky little guy

#he’s just autistic about sharks and i love him for it. i forgive him for his crimes (being rich)#also his line about ‘having enough of these working class heroes’ or whatever. i was ready to fight him for that one#i knew about concerned police officer and weird old vaguely threatening fisherman but no one ever mentioned the silly little guy who just.#i knew when every jumpscare happened but i didn’t know one of the three main characters existed#he just loves sharks man. man was so funny. ‘hey i was told to tell you guys that you shouldnt all get in that boat’ ‘we’ll do it anyway’#‘okay! they’re going to die :)’#crazwaz posted#id seen the clip of matt discovering the body and the clip of them paddling to shore at the end!!!#but i’d never seen any clip of quint so i figured the one at the end was him and the body discoverer was a random character#he was wearing a wetsuit in the body scene and is seen from far away in behind in the final one so i have the right to not have realized ok#also weirdly enough my submechanophobia was not really triggered at all? which is wild. like one or two times it happened but like. that was#so weird to just. know that normally i’m scared of that kind of thing but it just. didn’t happen? like i’m scared of the jaws animatronic on#the universal ride! it scared me in pics and it scared me when i saw it irl! but bruce? nah she was just fine#that’s another thing i always think of bruce as she/her like. them all using he/him for the shark confused me#my brother mentioned she’s a girl in jaws 3d + in the wild girl sharks are bigger than boys so that’s probably what caused it#but i still think of godzilla as she/her and that one has like no evidence so maybe my brain just does that to them or smth

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

summary: stalker!rafe who saves pogue surfer!reader from the obx storm!

tw: stalker!rafe, dark!rafe but that’s just him tho, a storm, idk anything about boats or surfing

word count: 564

you were used to big waves. surfing is your life. you are no professional but you thought you could handle the obxs storms waves but turns out the roughness of the salt water was too much for you.

“hey hey it’s not safe out there come here i can help you get home,” a tall man yelled from his yacht, reaching out a hand for you. you felt stupid being out in a storm. when you lost the pogues and got pushed out to sea you knew your idea had become deadly so the strangers help might save you.

“here lemme help you. you are way too delicate to be out here in these tough waves, pretty girl,” rafe smirked, pulling you out of the water.

“i’m fine but i guess i’m used to smaller waves,” you said with an insecure giggle. “i’m y/n. um i live on the cut. you said you could get me home?” you said with a nervous smile, never meeting this handsome man before.

“why don’t you stay a while y/n? i got fresh clothes that you can wear and beer and snacks if you’re hungry. seriously whatever you want. i’m rafe.”

rafe was so excited to be around you. he’d been watching you surf from his yacht for months. staring at your body from a far wasn’t doing it for him anymore so when you took off your wetsuit rafe audibly moaned, standing up fast and coughing staring at your body in the pink bikini he only saw from a far distance.

“thanks, rafe but i need to get home. you’re really sweet but my friends will be worried since i got pulled into sea by the waves.” rafe made a fast excuse looking out on the horizon.

“i don’t think my boat will make it to shore. it’s just pouring now and it uh l-looks real bad. we um should probably just stay out here for the night.”

“are you sure because i think a yacht this huge can handle a storm like this.” you laughed staring at him confused.

“you think you know yachts y/n? you’re a pogue, stick to your surfboard,” rafe said laughing. you didn’t like his obnoxious joke but brushed it off.

“ya whatever, i’m a pogue. so what? can i get some clothes? i’m about to turn into a ice cube.” you rolled your eyes while walking down to the cabin exploring the living space of the boat. it was a scene straight out of a frat house nightmare, old beer cans and porn magazines.

amongst the clutter, a picture caught your eye: a girl in a pink bikini, surfing on a vibrant wave, laid provocatively on his bed. you reached out to inspect it, but he snatched it away before you could get a closer look “umm so you live here, rafe?”

“does it matter?” rafe frowned as you put on his old shirt and sarah’s sweatpants over your bikini, you asked “no but um where am i gonna sleep stranger? you know this is a major stranger danger situation right now.” you laughed, pointing at the both of you.

he smirked at your bubbly personality that he’d seen from afar as he would watch you at kook and pogue bonfire parties.

“next to me,” rafe said, watching your every movement. “no, that’d be weird. i don’t even know you. i’ll sleep on the couch, it’s no big deal,” you said so casually. mad at your rejection, rafe stood up, hovering over you.

“just seriously y/n. you can trust me ok? just stay in the bed with me, it’s cold out,” rafe said with intensity. as you noticed his blue eyes getting darker and his body getting closer, he gently tucked a loose strand of hair behind your ear, his touch sending a shiver down your spine. “you know,” he whispered, his voice sending ripples of unease through you, “you always fidget with your necklace when you’re nervous, your fingers trace its outline when you’re anxious.”

your heart skipped a beat. how did he know about that? it was like he could read your mind. feeling exposed, you backed away. his gaze locked into yours, making you feel vulnerable and like he had uncovered parts of you that were meant to stay hidden. you noticed the storm seemed to be calming down since rafe pulled you up on the cameron’s yacht. a perfect getaway.

“you know what uh i- i can handle these waves. don’t worry about me. thanks for helping me though,” you said as you bent over to pick up your wetsuit and surfboard. he grabbed your bicep forcefully pulling you up. he thought of every excuse but couldn’t manage to create one.

“no, no you can’t leave ok.” rafe stated, grabbing you by the wrist firmly. “yo dude, don’t fucking touch me. i don’t even know you.” as you scoff at him, you look deep into his blue eyes and recognize him, letting his rough hands grip onto your waist. you couldn’t put your finger on where from.

“dont fucking dude me. god you are such a pogue. y’know you do know me. i’m rafe. i’m someone you can trust y/n. imma proactive person. if i wasn’t there to help you get out of those waves who knows what could’ve happened to you. i protect you. i’ve been protecting you for months for fucks sake and you don’t appreciate me.”

a/n: idk maybe a part 2 is needed??? send me ur thots!

#rafe cameron#rafe x reader#rafe cameron x pogue!reader#drew starkey#rafe cameron x female reader#rafe cameron concepts#rafe cameron x kook!reader#outer banks#rafe cameron x y/n#rafe cameron x reader#rafe cameron x oc#dark rafe x reader#dark!rafe cameron#dark!rafe x reader#stalker!rafe#rafe x oc#rafexsurfer!reader#rafe drabble#rafe headcanons#amandabthinks#rafe cameron angst#pogue!reader#surfer!reader#outer banks pogues#rafe fic#rafe fanfiction#drew starkey drabble#rafe cameron fluff#dark!rafe#rafe x you

440 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bonfire nights

Parings: Jim mason x y/n

Summary: takes place in the past - the first memories you had of jim. Most likely a 2 or 3 part series

Warnings: none

Word count: 1.3k

taglist: @ghostiesbedroom @lovelylangdonx @queencocoakimmie@langdonsinferno @peachesandfern @gold-dragon-slayer @charlottelouise135 @hplotrfan @rosegoldrichie @taryn-just-happened @rocketgirl2410@little-grunge-flowerz @ccodyfern @1-800-bitchcraft @langdonsoceaneyes @sojourne @starwlkers @bellejeunefillesansmerci (hope its okay if i tagged you)

You sat on your favourite rock - close enough to hear the waves crash at the other rocks beneath you - but far enough for the water not to reach you, it was where you first met - Jim.

At the other end of the beach you could hear laughing in the distance, it reminded you of the late nights with Jim and his friends - you would watch them from afar, they always seemed to be laughing and having fun by the bonfire - you were a watcher.

-2 months ago-

You watched and listened to Jim and his friends for what seemed like forever - you wanted to be like them - outgoing, goofy, sporadic- you were neither of those things, they just seemed like a really cool crowd of people. But one night it was all about to change - Jim saw you sitting alone as he slowly walked down the mini trail that lead into the bay-

“Hey - you alright” Jim called out from behind you

You turned your head slightly to see who it was - “yeah im fine” - Jim had messy brown curls, bright ocean eyes you could see from a mile away - and he was always in that jean jacket, it suited him so well. This was your first memory of Jim - of course you saw him at school but you never actually talked to him.

“Wanna come join our fire” jim asked softly as he walked towards you

You turned to face him then immediately looked over at the huge bonfire - “its not really my scene over there” you laughed - you could hear ms popular heathers laugh above them all.

Jim laughed - “its not mine either but its a lot less lonely”

You pulled your jacket tighter to your body - “maybe” you spoke softly - you did have a small crush on Jim, he was kind and sweet (from what you could see).

Jim crouched down beside you - “the offer is always standing love” he smiled as he looked out into the ocean with you.

“Thanks” you smiled - “im y/n” you spoke softly

“Jim - Jim mason” he smiled - god there's that smile. Jim knelt there for a few more minutes then got up walked towards his mini party -

“Bye Jim” you said quietly to yourself

Its been a few days since you’ve seen Jim in the bay of palos - but you would see and hear his mum pacing back and forth yelling at the bay boys (jims friends) for being so damn loud at night, but you had hoped to see him again..

-2 weeks pass by-

You decided to change it up and go out to the bay earlier - you wanted to soak in the sun… for once - today was different, it was quiet and calm, the tide was low, there was not a segal near to hear, but the best part was there was no bay boys, just Jim and his twin sister Medina surfing. Jim and Medina were basically attached at the hip - but they have such different personalities, Jim was a ‘follower’ and Medina had a strong personality, I guess their relationship was unique.

Both of them made surfing look so easy, you could never ! on the best of days you were lucky not to trip over your own 2 feet.

“HEY” Jim yelled from what seemed like the middle of the bay - his hand was waving at you

You had your legs stretched out with a book in your hand - homework of course - for a second you didnt realize Jim was waving at you, “what? Me??!” you yelled back at him

Medina waved her hand to come join them - “I'M STUDYING” you yelled back while holding your book up.

An hour or so went by without any disturbance from the mason twins, it was nice - peaceful. You could help but think of what Jim looked like while out on the ocean, and the texture of his hair - he probably smelt of salt water - his beautiful chocolate curls probably look amazing after being in the water all afternoon.

“Hey sunshine - how've you been” Jims voice boomed from above you while he blocked your sun-

“I've been well - how about yourself mason” you looked up at him - “it been awhile” you laughed.

“Yeah yeah - it's good to be back, but hey - you still owe me” Jim smiled

“Excuse me - owe you what ?” you questioned him, then yourself

“You said maybe to coming to a bonfire and i didnt see you at the last 2 we had, so your coming tonight” jim smiled as he unzipped the top half of his wetsuit

“Tonight? I - im uh busy” you tried to make an excuse - he was a gift sent from god, the way the water droplets fell down his shoulders onto his chest - it made it hard to concentrate

Jim laughed - “i'll come pick you up, lets say 8pm?”

Its like he didn't even give you a choice - “uh - sure, yeah that works”

“Its the blue house yeah?” jim asked as he pointed to the blue-ish white house with no fence

“Yep - thats me” you laughed

“Its a date” Jim smiled as he picked up his board and walked away

“A - date” you whispered to yourself

Within seconds of realizing you were going on a mini date with Jim freaking Mason you stood up and grabbed your belongings and literally ran up the hiking trail - you needed to get ready, to shower, pick out an outfit, hair, makeup - but there just felt like there was not enough time.

When you got into your bedroom you dropped everything on the floor and headed to your dresser -- you picked out a pair of black ripped jeans, and paired it with a pale yellow graphic tee, for shoes you would probably just wear your vans - who cares if they were dirty, they were old anyways. As for your hair you sprayed some dry shampoo at the root and a texture spray throughout - the messy style just fit you perfect.

‘Y/n! - theres a young man at the door for you” you mother called out

“Already?” you spoke quietly to yourself - you quickly grabbed your cell, and a pony… just incase.

It felt like you ran down the stairs but you knew you werent it was just moving so fast - “hi Jim” you smiled when you met him at the bottom

“You look - wow” Jim smiled at you

There it was - that smile, it melted your heart - maybe cause it was the way his eyes smiled with his mouth - or maybe cause he just seem genuinely happy.

“Shall we ?” jim held his hand out for you

Your fingers interlocked his and he quickly pulled you out the front door - “arent we taking this path” you questioned jim as he walked past the short cut down -

“No” he shook his head as he kept walking with you

Something didnt feel right, you have never seen jim take the long before - “jim where are we going”

“Down to the bay - where just gonna take a different path, i dont wanna share you with anyone yet”

“Share me?” you raised a brow

“Yeah - your the dark mysterious girl, and i like that.”

“Jim your freaking me out” your feet stopped in place

“Im sorry - i didnt mean to freak you out - i just wanna get to know you better before my friends rip me away’ his voice cracked

“Oh-” your voice was low - “so your just gonna ditch me with a bunch of random popular girls?”

“Oh god no - medina, my sister will be there. And besides your staying by my side.” Jim smiled

You nodded your head and proceeded walk behind jim - the both of you walked in silence for a moment, you reached the top of the bay -

“y/n”

“Yeah jim” you looked up at him

“I really like you - i kinda always have.” jims eyes locked to yours

#jim mason#jim mason x reader#jim mason x you#jim mason x female reader#cody fern#The Tribes of Palos Verdes#topv#michael langdon#michael langdon x you#michael langdon x reader#ahs#Duncan Shepherd#duncan shepherd blurb#duncan shepherd x you#duncan shepherd x female reader#duncan shepherd fic#michelal x female

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

On another site Star Wars Trivia:

Chewie stood on a small landing and pounded his mighty clenched fists against the unmoving hatch. He didn’t want to stand in the putrid pool of liquid filling the room beneath all the trash.

Luckily he, Luke, and Leia had avoided being hit by a deadly bolt from Luke’s blaster which had bounced from wall to wall before slamming into a pile of floating metallic trash, destroying it.

The room was magnetically sealed. Their weapons wouldn’t help them.

At that moment, Han fell from the darkened chute above, landing in the trash piles as they had just moment before.

He stood up, finding his footing as best he could on top of the garbage, silently assessing the situation before turning to Leia. “The garbage chute was a really wonderful idea!”

He continued condescendingly, “What an incredible smell you’ve discovered.”

Chewie was still trying to open the hatch of trash compactor 3263827. Han caught sight of him and drew his blaster. “Let’s get out of here. Get away from there.”

Luke tried his best to stop him. “No, wait!”

Han fired, and again, the blast ricocheted around the room, narrowly missing each of them before blasting the trash.

“Will you forget it, I already tried it, it’s magnetically sealed”, gesturing to the hatch.

Leia lit into him, “Put that thing away, you’re going to get us all killed!”

Han glared at her. “Absolutely your worship. Look I had everything under control until you led us down here. You know it’s not going to take them very long to figure out what happened to us.”

Leia fired back, “It could be worse.”

Suddenly a deep, inhuman moaning boiled up from beneath the trash and water, echoing off the disgusting walls.

“It’s worse” said Han, looking around for the source of the noise, blaster drawn.

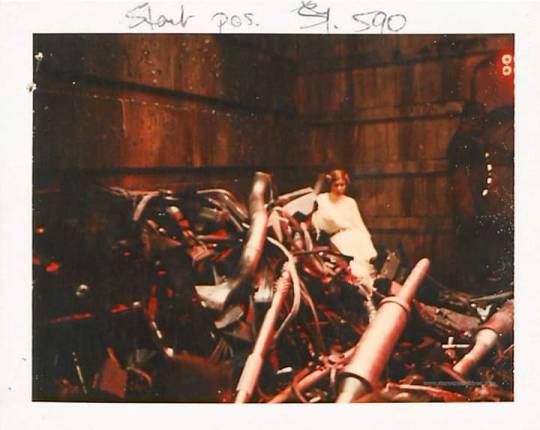

The trash compactor footage was shot June 21st and 22nd 1976 on stage 4 at Elstree Studios. On June 24th, two days after this scene was completed, Harrison Ford wrapped his last day working on ‘Star Wars’ by filming his scenes in the 'Falcon's gun turret, for the getaway from the Death Star.

The detention block escape scene, followed by the Trash Compactor scene, is the first time the hero band of Luke, Leia, Han, and Chewbacca merges on screen. Luke is trying to keep the peace while Han and Leia are sniping at each other, and the undeniable chemistry tells you this is something special. It’s the perfect mix of alarm and humor that makes Star Wars work at its’ core.

As protection against the slimy water, the actors had the option of wearing a wetsuit under their costumes. Carrie thought it was mandatory, and wore hers for both days of shooting (Likely a tan skin color based on the images seen and with it being under her white costume dress).

Carrie: “I liked jumping through the garbage chute, but didn’t like wearing the wet suit. It was under my white gown, for protection, or I was going to look like Walter Brennan from the waist down from being in the water so long.”

British cameraman Ronnie Taylor, who passed away in 2018, also wore fishing waders, as did Focus puller Peter Taylor.

Roger Christian, set decorator said “The garbage compactor set was also pretty hard, because I knew I had actors in there and the walls had to come in, and they had to be in dirty water and I had to get stuff that would be light enough so it wouldn't hurt them but also not bobbing around." The set was dressed by Brian Lofthouse and the rest of the prop crew.

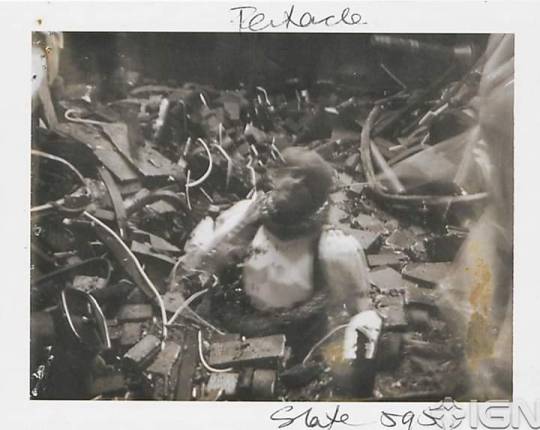

Even before the terror of the converging walls began, Luke and the others were visited by a live resident of the compact, the Dianoga. A lone eye stalk appeared out of the water to spy on its prey, and the something that moved past Luke’s leg was a large tentacle.

That same tentacle wound up and around Luke’s leg, body, and throat, strangling him and ultimately pulling him under the putrid water. Only after hearing the clanging indications that the compactor was about to come to life did it release him.

In order to portray the realism of the scene, Mark strenuously made himself appear as if he were being strangled.

Mark Hamill:

“I purposely made myself red-faced for a strangulated look, causing a blood vessel in my eye to burst. Afterwards-they had to shoot carefully to hide it until I healed. George told me I should've asked him first because with the lighting and red-filters it made no difference.”

It was Mark’s left eye that was affected. He was examined by the studio’s Dr. Collins, and then he was sent to be seen by eye specialist Dr. Watson.

Originally, the Dianoga was to have been a much larger creature, and be responsible for far more of the sequence than it ended up being.

Lucas described the Dianoga creature he envisioned in his mind this way: “It’s a cross between a jellyfish and as octopus, a transparent muck-monster which can take any shape. It presses itself against the floor or in nooks and crannies of the trash masher, or even in the trash itself to survive.”

Ultimately he had to scale back on the size of the part the Dianoga would play. It was yet another compromise. He had tried a trash compactor escape scene in THX 1138 and he had to cut it out because “it failed miserably”.

John Stears, Special production and mechanical effects supervisor, said they created a much larger monster, which was ultimately cut down from a full body to a tentacle when Lucas decided to combine the original, larger Dianoga encounter with the trash compactor scene. “There was an awful lot of work that went into that monster, and it really was superb. Unfortunately we couldn’t use it in its entirety. You never see the full body, just the tentacles.”

During pre-production there had been a plan to inflate the monster, so it would seem to emerge from the water. Budget cuts forced Lucas to combine scenes, so that idea was scrapped. A smaller tank had to be used, and the full scale monster became physically impossible on the resulting set.

As a result of the scaled down scene, the iconic head/eye that pops up out of the water and looks around was added at the last minute. Phil Tippett and Jon Berg sculpted it and filmed it on a stage at ILM. It was made from latex over foam, and featured hand-punched hair and a mechanism that allowed it to blink. A puppeteering rod allowed it to be turned from side to side so it could look around the trash compactor. The trash and debris in the garbage for their shoot included pieces from exploded pyrotechnic X-wings, and wreckage from the exploded Death Star.

George initially intended for music to play a part in the Trash Compactor/Dianoga scene, but ultimately decided to remove it to allow the creature’s noises, and its movement in the water to be heard, giving the scene a more ominous feel and tone.

Because the compactor room was a hollow metal chamber, Sound designer Ben Burtt ring modulated vocals, and added echo. He took inspiration from the technique used for the devil in ‘The Exorcist’ and used them for the sounds of the Dianoga. A ring modulator takes two signals and multiples them to create two new frequencies.

When the Dianoga retreats, and impending danger becomes immediate danger with the walls closing in, music returns to ramp up the tension.

From the original LP liner notes by John Williams for Side 3: Track 4, ‘The Walls Converge’:

“The walls begin to close together and the group helplessly fights to stop them. Finally C-3PO and R2-D2 come to the rescue and, at the last minute, stop the walls from crushing the group. This music has no thematic connection with anything else. I wanted to create a dark threatening sound which would represent the jeopardy of the group. I intentionally used low end music so it would co-exist with the grinding sound effects of the big steel walls.”

George was not happy with having to cut down the scene, and on one of the days Mark noticed he was a little down. He was waiting for another take to be set up - a scuba diver playing the part of the Dianoga to pull him under the water.

From Mark: “I hadn’t planned this, it was just out of desperation that this idea came into my head what with the monster being called a dianoga and everything. I picked up one of the little bits of green pieces of styrofoam floating on the water and, to the tune of ‘Chattanooga Choo Choo,’ I started to sing, ‘Pardon me, George, could this be dianoga poo-poo?'”

Lucas responded by putting his foot on Mark’s chest and pushing him into the water.

As a result of standing in the disgusting, murky water over the two days, Peter Mayhew’s yak-hair Chewbacca suit reeked for the rest of production.

The scene immediately after the heroes exit the compactor was shot in continuity, in what was called the ‘disused hallway’, explaining why it wasn’t filled with Stormtroopers or others noticing their exit from the compactor.

Before filming the scene, Mark had taken a look at the continuity of the film up to that shot, and was concerned.

“I remember saying things like, ‘Well, wait a minute. I just got out of the trash compactor. How come my hair’s all perfect?’ And Harrison replied, ‘Hey kid, it ain’t that kind of movie.’ And I thought, he’s so right.” – Mark Hamill.

1 note

·

View note

Link

Davide Enia | translated by Antony Shuggar | an excerpt adapted from Notes on a Shipwreck: A Story of Refugees, Borders, and Hope | Other Press | February 2019 | 16 minutes (4,334 words)

On Lampedusa, a fisherman once asked me: “You know what fish has come back? Sea bass.”

Then he’d lit a cigarette and smoked the whole thing down to the butt in silence.

“And you know why sea bass have come back to this stretch of sea? You know what they eat? That’s right.”

And he’d stubbed out his cigarette and turned to go.

There was nothing more, truly, to be said.

What had stuck with me about Lampedusa were the calluses on the hands of the fishermen; the stories they told of constantly finding dead bodies when they hauled in their nets (“What do you mean, ‘constantly’?” and they’d say, “Do you know what ‘constantly’ means? Constantly”); scattered refugee boats rusting in the sunlight, perhaps nowadays the only honest form of testimony left to us — corrosion, grime, rust — of what’s happening in this period of history; the islanders’ doubts about the meaning of it all; the word “landing,” misused for years, because by now these were all genuine rescues, with the refugee boats escorted into port and the poor devils led off to the Temporary Settlement Center; and the Lampedusans who dressed them with their own clothing in a merciful response that sought neither spotlights nor publicity, but just because it was cold out and those were bodies in need of warmth.

*

Haze blurred our line of sight.

The horizon shimmered.

I noticed for what must have been the thousandth time how astonished I was to see how Lampedusa could unsettle its guests, creating in them an overwhelming sense of estrangement. The sky so close that it almost seemed about to collapse on top of us. The ever-present voice of the wind. The light that hits you from all directions. And before your eyes, always, the sea, the eternal crown of joy and thorns that surrounds everything. It’s an island on which the elements hammer at you with nothing able to stop them. There are no shelters. You’re pierced by the environment, riven by the light and the wind. No defense is possible.

It had been a long, long day.

I heard my father’s voice calling my name, while the sirocco tossed and tangled my thoughts.

*

I happened to meet the scuba diver at a friend’s house.

It was just the two of us.

The first, persistent sensation was this: He was huge.

His first words were these: “No tape recorders.”

He went over and sat down on the other side of the table from me and crossed his arms.

He kept them folded across his chest the whole time.

“I’m not talking about October third,” he added, his mouth snapping shut after these words in a way that defied argument.

His tone of voice was consistently low and measured, in sharp contrast with that imposing bulk. Sometimes, in his phrases, uttered with the sounds of his homeland — he was born in the mountains of the deepest north of Italy, where the sea is, more than anything else, an abstraction — there also surfaced words from my dialect, Sicilian. The ten years he’d spent in Sicily for work had left traces upon him. For an instant, the sounds of the south took possession of that gigantic body, dominating him. Then the moment would come to an end and he’d run out of things to say and just stare at me, in all his majesty, like a mountain of the north.

Before your eyes, always, the sea, the eternal crown of joy and thorns that surrounds everything.

He’d become a diver practically by sheer chance, a shot at a job that he’d jumped at immediately after completing his military service.

“We divers are used to dealing with death, from day one they told us it would be something we’d encounter. They tell us over and over, starting on the first day of training: People die at sea. And it’s true. All it takes is a single mistake during a dive and you die. Miscalculate and you die. Just expect too much of yourself and you die. Underwater, death is your constant companion, always.”

He’d been called to Lampedusa as a rescue swimmer, one of those men on the patrol boats who wear bright orange wetsuits and dive in during rescue operations.

He told me just how tough the scuba diving course had been, lingering on the mysterious beauty of being underwater, when the sea is so deep that sunlight can’t filter down that far and everything is dark and silent. The whole time he’d been on the island, he’d been doing special training to make sure he could perform his new job at an outstanding level.

He said: “I’m not a leftist. If anything, the complete opposite.”

His family, originally monarchists, had become Fascists. He, too, was in tune with those political ideas.

He added: “What we’re doing here is saving lives. At sea, every life is sacred. If someone needs help, we rescue them. There are no colors, no ethnic groups, no religions. That’s the law of the sea.”

Then, suddenly, he stared at me.

He was enormous even when he was sitting down. “When you rescue a child in the open sea and you hold him in your arms . . .”

And he started to cry, silently.

His arms were still folded across his chest.

I wondered what he could have seen, what he’d lived through, just how much death this giant across the table had faced off with.

After more than a minute of silence, words resurfaced in the room. He said that these people should never have set out for Italy in the first place, and that in Italy the government was doing a bad job of taking them in, wastefully and with a demented approach to issues of management. Then he reiterated the concept one more time: “At sea, you can’t even think about an alternative, every life is sacred, and you have to help anyone who is in need, period.” That phrase was more than a mantra. It was a full-fledged act of devotion.

Local Bookstores Amazon

He unfolded his words slowly, as if they were careful steps down the steep side of a mountain.

“The most dangerous situation is when there are many vessels close together. You have to take care not to get caught between them because, if the seas are rough, you could easily be crushed if there’s a collision. I was really in danger only once: There was a force-eight gale, I was in the water with my back to a refugee boat loaded down with people, and I saw the hull of our vessel coming straight at me, shoved along by a twenty-five-foot wave. I moved sideways with a furious lunge that I never would have believed I could pull off. The two hulls crashed together. People fell into the water. I started swimming to pick them up. When I returned from that mission, I still had the picture of that hull coming to crush me before my eyes. I sat there on the edge of the dock, alone, for several minutes, until I could get that sensation of narrowly averted death out of my mind.”

He explained that when you’re out on the open water, the minute you reach the point from where the call for help was launched, you invariably find some new and unfamiliar situation.

“Sometimes, everything purrs along smoothly, they’re calm and quiet, the sea isn’t choppy, it doesn’t take us long to get them all aboard our vessels. Sometimes, they get so worked up that there’s a good chance of the refugee boat overturning during the rescue operations. You always need to manage to calm them down. Always. That’s a top priority. Sometimes, when we show up on the scene, the refugee boat has just overturned, and there are bodies scattered everywhere. So, you have to work as quickly as you can. There is no standard protocol. You just decide what to do there and then. You can swim in a circle around groups of people, pulling a line to tie them together and reel them in, all at once. Sometimes, the sea is choppy and they’ll all sink beneath the waves right before your eyes. In those cases, all you can do is try to rescue as many as you can.”

I have the distinct sensation that I’m face-to-face with human beings who carry an entire graveyard inside them.

There followed a long pause, a pause that went on and on. His gaze no longer came to rest on the wall behind me. It went on, out to some spot on the Mediterranean Sea that he would never forget.

“If you’re face-to-face with three people going under and twenty-five feet farther on a mother is drowning with her child, what do you do? Where do you head? Who do you save first? The three guys who are closer to you, or the mother and her newborn who are farther away?”

It was a vast, boundless question.

It was as if time and space had curved back upon themselves, bringing him face-to-face with that cruel scene all over again.

The screams of the past still resonated.

He was enormous, that diver.

He looked invulnerable.

And yet, inside, he had to have been a latter-day Saint Sebastian, riddled with a quiverful of agonizing choices.

“The little boy is tiny, the mother extremely young. There they are, twenty-five feet away from me. And then, right here, in front of me, three other people are drowning. So, who should I save, then, if they’re all going under at the same instant? Who should I strike out for? What should I do? Calculate. It’s all you can do in certain situations. Mathematics. Three is bigger than two. Three lives are one more life than two lives.”

And he stopped talking.

Outside the sky was cloudy, there was a wind blowing out of the southwest, the sea was choppy. I thought to myself: Every time, every single time, I have the distinct sensation that I’m face-to-face with human beings who carry an entire graveyard inside them.

*

I tried calling my uncle Beppe, my father’s brother. We called each other pretty frequently. Often my uncle would ask me: “But why doesn’t my brother ever call me?” I’d answer: “He doesn’t even call me, and I’m his first-born son, Beppuzzo, it’s just the way he is.”

The phone rang and rang for more than a minute, with no answer.

I hung up and went back inside.

We ate dinner, tuna cooked in sweet-and-sour onions and a salad of fennel, orange slices, and smoked herring.

There were four of us sitting around the table: Paola, Melo, my father, and me.

We were at Cala Pisana, at Paola’s house. Paola is a friend of mine. She’s a lawyer who’s given up her practice and has lived on Lampedusa for years now. There, with her boyfriend Melo, she runs the bed and breakfast where I usually stay as my base of operations whenever I’m doing research on the island.

I was setting forth my considerations on that exceedingly long day, in a conversation with Paola. From time to time, Melo would nod, producing small sounds, monosyllabic at the very most. My father, on the other hand, made no sounds whatsoever. He was the silent guest. Patiently, with his gaze turned directly to the eyes of whoever was speaking, he displayed a considerable ability to listen that he’d developed in the forty-plus years he��d practiced his profession, cardiology. He invited people to tell him things just by the way he held his body.

I was considering out loud that everything happening on Lampedusa went well beyond shipwrecks, beyond a simple count of the survivors, beyond the list of the drowned.

“It’s something bigger than crossing the desert and even bigger than crossing the Mediterranean itself, to such a degree that this rocky island in the middle of the sea has become a symbol, powerful and yet at the same time elusive, a symbol that is studied and narrated in a vast array of languages: reporting, documentaries, short stories, films, biographies, postcolonial studies, and ethnographic research. Lampedusa itself is now a container-word: migration, borders, shipwrecks, human solidarity, tourism, summer season, marginal lives, miracles, heroism, desperation, heartbreak, death, rebirth, redemption, all of it there in a single name, in an impasto that still seems to defy a clear interpretation or a recognizable form.”

Lampedusa itself is now a container-word: migration, borders, shipwrecks, human solidarity, tourism, summer season, marginal lives, miracles, heroism, desperation, heartbreak, death, rebirth, redemption, all of it there in a single name.

Papà had remained silent the whole time. His blue eyes were a well of still water in whose depths you could read no judgment whatsoever.

Paola had just poured herself an espresso.

“Lampedusa is a container-word,” she repeated under her breath, nodding to herself more than to me.

She sugared her coffee and went on with her thoughts. “And in a container, sure enough, you can put anything you like.”

Little by little, with a gradual rising tone, her voice grew louder, and the pace of her words became increasingly relentless.

“In the container called Lampedusa, you really can fit everything and the opposite of everything. Take the Center where the young people are brought after they land. Do you remember? You saw it when you came back here the year after the Arab Spring.”

It was the summer of 2012 and I’d asked a few Lampedusan piccirìddi — kids — who I’d met on the beach: “Do you all ever go to the Center?” I was fantasizing about the idea that the structure where anyone who landed on Lampedusa was taken must somehow constitute a focus of enormous fascination for them. “E che ci ham’a iri a fare?” those children had replied in dialect. I was stunned to hear their answer: “Why on earth would we bother with that place?” I had been convinced, until that moment, that the presence of new arrivals must have generated a monstrous well of curiosity, becoming the sole topic of conversation, of play, of adventure. Something rooted in the epic dimension.

“Would you take me there?” I’d asked them, hesitantly, already anticipating my defeat.

“We’d rather die.”

There was nothing about the Center that appealed to them, it had never interested them. Only after I finally saw it did I understand that I had committed an enormous mistake: I’d interacted with the children but used the parameters of an adult. Along the road that leads to the Center, there was nothing but rocks, brushwood, and dry-laid stone walls upon which signs appeared here and there, reading for sale. The only form of life was a thunderous bedlam of crickets. It was an arid place. Of course the piccirìddi never went there, there was nothing fun to do, nowhere to play. Myths aren’t built out of nothing.

Kickstart your weekend reading by getting the week’s best Longreads delivered to your inbox every Friday afternoon.

Sign up

The Center had been built from the ground up on the site of an old army barracks. A number of dormitory structures, an open plaza, an enclosure fence. For all intents and purposes, it looked like a prison.

“Has anything changed about the Center in the last few years?” I asked Paola.

“The name. At first it was called the Temporary Settlement Center, then the Center for Identification and Expulsion, and now it’s a Hot Spot Center, whatever that’s supposed to mean. The governments change, the names rotate, but the structure is always the same: Under normal conditions it can hold 250 people, in an emergency situation it could take in at the very most 381 full-time residents. Those are the numbers, you can’t increase the number of bathrooms, or, for that matter, the number of beds. And in 2011 more than two thousand people were packed in there, for days and days, without being told at all what was to become of them. The world applauded the Arab Spring, and then imprisoned its protagonists. Was this the best response we could provide to their demands? And do you know what you create by keeping too many people shut up in such a small space? Rage. That’s how you create wild animals. And, in fact, a revolt broke out; they burned their mattresses and set fire to one wing of the structure.”

My father listened impassively, even though — clearly listening, but remaining opaque, inscrutable — he had to be squirreling away all that information. Melo was chewing on his lower lip, Paola continued to talk without taking her eyes off the demitasse of espresso.

“The Center, at least on paper, is supposed to be a containment facility if nothing else, right? And in fact, there’s a hole in the fence around the Center. I think it dates back to that period in 2011, but I couldn’t rule out by any means that the hole was there even earlier. It’s a great big hole and it works as a pressure valve, in fact, allowing the young men to get out, take a walk, come into town to try to get in touch with their families by using the Internet through the generosity of a number of residents. And what are you going to do, if a little kid asks you to let him talk to his mother to let her know that he’s still alive? Tell him he can’t use your computer?”

She’d continued to stir her espresso, tiny spoon in little demitasse. The sound of steel rattling against porcelain had punctuated the cadence of her words, like a rhythmic counterpoint, necessary to keep from losing the thread, to keep from plummeting body and soul into an abyss of screaming.

“Believe me, Davidù, it’s a good thing that hole is there. It’s a door, a way of keeping them from feeling like caged animals. So, you see what the point is? The Center is a structure garrisoned by the police force, inside which no one can go without special authorization. Not even a priest can go in. The facade remains intact. But in the fence, there’s always been a hole. It’s a well-known fact and no one does anything about it. And it’s a good thing that no one does anything about it, let me say that for the thousandth time. Here is a concrete example of how closely emergency and hypocrisy have to coexist, bureaucracy and solidarity, common sense and cult of appearances. Lampedusa is a container of opposites, for real.”

History is sending people ahead, in flesh and blood, people of every age.

Through the open window came the roar of waves, water rising, tumbling, crashing down onto the sand, pouring back out, and starting over again, in an endless relaunching. Melo, seated at the head of the table, had consigned himself to silence, just like my father. Melo, too, spoke little if at all, the whole day through, at most a bare handful of words, often drawled out, because speaking costs effort and effort is a burden.

Paola sipped her coffee slowly, and it wasn’t until she’d finished it that she started talking again.

“It is History that’s taking place, Davidù. And History is complicated, a mosaic full of tiles of different shapes and sizes, sometimes similar, other times diametrically opposed, yet all of them necessary in order for the final picture to emerge. No, wait, let me correct myself: It’s not that History’s taking place now. It’s been taking place for twenty years.”

She started taking long drags on a cigarette, her third in half an hour.

“As you had an opportunity to understand yourself this morning, the scale of this event can be perceived immediately when you witness a landing. But even if someone never had a chance to witness one, what can you expect them to care about the history of your, my, our perceptions? History is already determining the course of the world, tracing out the future, structurally modifying the present. It’s an unstoppable movement. And this time, History is sending people ahead, in flesh and blood, people of every age. They set sail across the water, they land here. Lampedusa isn’t an exit, it’s a leg in a longer journey.”

She crushed her cigarette out in the ashtray while Melo poured himself what beer remained in the bottle. Through the open window, warm fall air pushed into the room, scented with hot sand and salt-sea brine.

*

In the days following the Arab Spring, mass arrivals had begun on the shores of Lampedusa. An island resident named Piera had happened to be down at Porto Nuovo, or New Port, to supervise the efforts of the town constables.

“I’ve still got the scene before my eyes, it was completely insane! So many people had landed that you couldn’t make your way through the port. They were everywhere, the wharf was packed and the vessels were coming in and landing, more people one right after the other. A procession of refugee boats! And they were coming ashore by the thousands! We were there to give them a hand, but we were hardly prepared for anything like those numbers. A carabiniere was telling all the new arrivals in French to move over to the hill to make room for the others, and in the meantime new boats were coming in from the sea, all of them packed to the gunwales, and there was just no time to move people aside before the new refugee boats had already landed more young people. I really couldn’t begin to guess how many thousands came in that afternoon, it was impossible to count them, seven thousand, eight thousand, nine thousand, there was no settled number. And how could we ever reckon that number? There were more of them than there were islanders on Lampedusa, that much is certain. The ones who were standing on the hill, as soon as the boats came in carrying their families — wives, husbands, children — would rush down to rejoin their loved ones. An incredibly crazy scene: The police would try to separate them and we were caught in the middle, knocked back and forth. You couldn’t figure out what was going on. And from the sea, boat after boat kept arriving, so many of them, in quick succession. A flotilla! No one had ever seen such a thing. There was a gentleman who arrived with a falcon on his arm. On another refugee boat, one young Tunisian had brought his own sheep. A lovely sheep! A breed of sheep I’d never seen in my life, spectacular. A thick coat of wool, very curly! Stupendous. But in the end, we had to put the animal down. There was no alternative.”

There were more foreigners than residents on Lampedusa, more than ten thousand refugees as compared to five thousand islanders. Fear and curiosity coexisted with mistrust and pity. The shutters remained fastened tight, or else they’d open to hand out sweaters and shoes, electric adapters to charge cell phones, glasses of water, a chair to sit on, and a seat at the table to break bread together. These were flesh-and-blood people, right there before our eyes, not statistics you read about in the newspapers or numbers shouted out over the television. And so, in a sort of overtime of aid and assistance, people found and distributed ponchos because it was raining out, or they cooked five pounds of pasta because those young people were hungry and hadn’t eaten in days.

Everyone had been abandoned to their own devices.

The following year, the Italian government proudly proclaimed the figure of “zero landings on Lampedusa” as if it were a medal of honor to be pinned to its chest.

“And it’s true,” Paola had assured me that summer in 2012. “No boats are landing here anymore. We didn’t even see any in the spring. And do you know why? When the refugee boats are intercepted they’re escorted all the way to Sicily, and that’s where the landings take place, far out of the spotlight. Which means: zero landings on Lampedusa. From a purely statistical point of view, the logic is impeccable. And yet, you see? The island is fragmented, in the throes of anxiety, tumbled and tossed in this media maelstrom, a hail of contradictions. People talk less and less and, when they do, it’s only to complain about concrete problems, such as the lack of a hospital, for instance, or the cost of gasoline, which here is the highest in all of Italy. And they point out, with a touch of bitterness, that all the attention is always focused on those who arrived over the water, while the everyday challenges that we residents face don’t really seem to matter to anyone, except to us.”

There was the vacation season, the real engine of the island’s economy, to get up and running.

From time to time, someone would shoot a furtive glance toward the horizon.

“Sooner or later, something will come back to these beaches,” a fisherman had told me. That prediction, shared by all the residents, came true the following year, on October 3, 2013. It was an event that outpaced even our wildest nightmares. A refugee boat overturned just a few hundred yards off the coast of the island, the waters filled up with corpses, and Lampedusa was overrun by coffins and television news crews. What had actually changed in the recent years, after all, were just the minor details. The corpses found in the fishing nets, for example, were simply tossed back into the sea in order to prevent the fishing boats from being confiscated and held in a subsequent investigation. The reports of alleged sinkings — alleged because the only sources were the words of those who had traveled on sister refugee boats — were only mentioned at the tail end of the newscasts. In the absence of a corpse, it’s always better to leave death confined to territories that everyone prefers not to explore. And yet, in the months that preceded the October tragedy, the everyday rescue work carried out by the Italian Coast Guard continued as always, people continued to trek across the Sahara, women continued to be raped in Libyan prisons, the refugee boats and the rubber dinghies set sail and were intercepted, or else they sank.

History certainly hadn’t stopped.

* * *

Davide Enia was born in 1974 in Palermo, Italy. He has written, directed, and performed in plays for the stage and for radio. Enia has been honored with the Ubu Prize, the Tondelli Award, and the ETI Award, Italy’s three most prestigious theater prizes. He lives and cooks in Rome.

Longreads Editor: Dana Snitzky

0 notes

Text

5 Balls-Out Insane Competitions You Won’t Believe Are Real

Sports were born when a subset of humanity became obsessed with the question: “Who among us is the best at doing this arbitrary physical thing?” Extreme sports came to be when an even smaller, crazier sect asked: “How could we make this arbitrary physical thing as dangerous as possible so that some of us can finally be granted the sweet release of death?” Follow that path to its logical conclusion, and you get this shit:

#5. There Are People Who Drown Themselves For Fun

“Freediving” sounds like the kind of carefree sport the whole family could enjoy during a vacation to Hawaii. “Free” makes it sound like there’s not a lot of rules, so maybe it just involves flopping around in a pool? And the “winner” is whoever has the most fun? But we suppose they had to go with that name rather than the more accurate “competitive drowning.”

Motto: “If at first you don’t GLUB GLUB BLUB.”

Freedivers are all about diving as far down as they can, ever trying to beat the last great attempt. They don’t wear oxygen tanks — they voluntarily deal in apnea, the cessation of breath. They dive down either with their own power, aided by weights, or strapping themselves into a machine known as “no limits,” and come up at the last second with a balloon-style flotation device — basically an Opposite Day parachute.

These are people who have painstakingly taught themselves to survive up to 9 minutes, 24 seconds without air, and it is precisely as dangerous as it sounds: There are around 5,000 freedivers in the world, and an estimated 100 of them die every year. That’s 2 percent of your entire sport just up and dying on an annual basis, and the people who perish are not just overconfident rookies: In 2015, Natalia Molchanova, the greatest superstar of the sport, never surfaced from a freedive that she was doing just for shits and giggles.

At that depth, shits and giggles are both fatal.

“Now, hold on,” you’re surely saying. “If it’s just a contest to see who can hold their breath the longest, why not do it in a small tank of water, where they can easily sit up if they exceed their limits?” Oh, you naive fool. You’re still not getting it: It’s because freedivers are fucking crazy. Understand, the body changes in many ways when you go hundreds of feet deep with no air but what you hold in your body. In some competitions, half of the divers come up unconscious. A study of 57 freedivers in an eight-day competition saw a whopping 35 of them suffer from some “adverse event” or another due to the body freaking out because of the lack of air.

Which makes sense, as their body is all but completely failing on these dives. Like a robot running out of battery, the typical freediver’s heart slows down to just 14 beats per minute, as opposed to the normal human heartbeat of 60 to 100 beats per minute. People in a coma have a faster beat. You shouldn’t be able to maintain consciousness, let alone operate at that level. In fact, experts reportedly have little idea how 100 percent of the divers don’t wind up unconscious on these dives.

Yet they push on, despite — or because of — the insanely high mortality rate and the fact that science has no idea how they’re doing their thing.

#4. You Can Take A 30-Mile Swim In Some Of The Most Shark-Infested Waters In The World

If you’re a world-class swimmer wishing to join some elite company, you could try doing something difficult but boring, like swimming the English Channel. Just keep in mind that over the years more than 2,000 people have actually done it. But there’s another swim out there, less known but far more perilous. How perilous? Try “only five people have ever done it.”

And that’s five more than would have in a sane world.

The 30-mile swim between the Farallon Islands and San Francisco’s Golden Gate Bridge is 10 miles longer than the English Channel route, but that’s just part of its terrorizing charm. The course goes straight through an area called the Red Triangle, a fun area of the ocean with the greatest number of great white shark attacks on humans. Shockingly, this means that anyone stupid/courageous enough to attempt the Farallon-Golden Gate route risks having to cut their swim short for little things like, oh, suddenly noticing that a great white shark has started circling them.

Sharks are banned from all but the most exciting Olympic events.

But the sharks aren’t your real enemy — you’re far more likely to succumb to water that can get as chilly as 48 degrees, and if that doesn’t sound very cold to you, it’s because you’ve never been submerged in 48-degree water for hours. It’s cold enough to suck the heat out of the body so fast that you’ll go into shock and won’t be able to control your breathing. One early attempter’s body temperature got so low that, when his support ship fished him out, the nurse on scene initially declared him dead.

And then there’s the weather. The route has a portion nicknamed the Potato Patch, known for its unpredictable, huge swells. Riding the waves on the Potato Patch can be like getting tossed off a 10-story building (80 to 100 feet at their peak), and its many currents, shifts, and whirlpools can be like you’ve fallen into God’s washing machine during the spin cycle. That is what the Farallon-Golden Gate swimmers are trying to swim through … after already swimming for hours, after already having seen all of their limbs go numb from the freezing cold.

Actual frost zombies have refused to compete.

But hey, screw sharks, cold, and waves, right? Surely modern technology has plenty of wetsuit with cold repellents, shark repellents, and wave … repellents that enable a strong swimmer to power through the route? Well, they might … if it wasn’t for the fact that whatever maniac set the rules for the swim declared that to officially complete this route, you aren’t even allowed a wetsuit. You’ll be jumping in the freezing, watery sharknado wearing just a bathing suit, goggles, and a swimming cap. We’re kind of surprised they even allow that.

#3. There’s A 3,100-Mile Foot Race … All Around The Same Block

Really, this had to happen. Marathons and ultra-marathons are a thing, so of course someone keeps adding more and more “ultras” in there until you wind up with a 3,100-mile race some sad-sack sports addict is actually prepared to try to finish. That much is no surprise. What is surprising, however, is the precise nature of this race. You’d think that the longest foot race on the planet would be an epic course over several varied, marvelous countries, or at least a Forrest Gump-style, winding, coast-to-coast trek across America.

The scenery: spectacular. The food situation: complicated.

What you wouldn’t expect is a mind-numbing hamster wheel race around a single city block in New York. But that’s what the Self-Transcendence 3,100 Mile Race is all about, and that’s what the few dedicated super-runners willing to take part in the competition face: endless laps around a single block in a boring cityscape, on a ruthless concrete surface. For 52 days, their day starts at 6 a.m. They run (or walk) until midnight, trying their best to complete all the required miles before the time limit is up. Do the math, and that’s basically two marathons a day, every day, for almost two months.

So unless they’re willing to cut down on their daily six-hour break, there’s no fun with friends, no TV, no shopping, no video games, just monotonous running on the same stretch of dreary New York streets. And yeah, this isn’t even the interesting streets — the block is a boring-ass one in Jamaica, Queens, creating a course of a little under .55 miles. It’s like purgatory for runners.

Purgajoggy.

Some of the runners are in it just because they like to run. Most of them are disciples of the Bengali Guru Sri Chinmoy, and believe that part of spirituality is taking on seemingly impossible physical challenges. Regardless of their motivation, this race might not make headlines with crazy injuries or deaths, but it’s still pretty hard on the feet … literally. Runners go through a dozen pairs of shoes during the race, and because no shoe feels good for long on a two-marathons-per-day pace, they generally just give up and cut the toe area away, letting their toes enjoy the sunshine. As for the ones who don’t, well … one runner had to have all of his toenails removed, because it was either that or the toes as well. He took a little two-hour break, and then resumed his race.

Then there’s the matter of diet. The runners estimate they burn through 10,000 calories per day, so they need intensely calorie-rich foods to keep from withering away, so they pretty much need to be snacking all the time. Said snacks, by the way, range from simple apples and glasses of (non-alcoholic) beer to freaking sticks of butter.

“No time to stop and chew, just give it to me as a suppository.”

Still, with their shoes giving up under them and nourished by things that would down a lesser person, the runners blaze on. The race has taken place regardless of the conditions; one year, New York was suffering such an insane heat wave that the mayor declared a “heat emergency” and estimated there would be 140 heat-related deaths in the city. The race went on as planned, though presumably the participants had to ingest their butter from a cup.

#2. In One Desert Rally, Mad Max Comes To Life

The universe of Mad Max is one of those gloriously madcap fictional worlds that are gorgeous to look at but might be somewhat unpleasant to actually live in. Real-life limitations and common sense render it borderline impossible to re-create Fury Road-style massive, deadly car chases where crazy people ride awesome custom vehicles through never-ending deserts. That is, unless you count the Dakar Rally, which just so happens to be that exact thing.

Dakar is Senegal’s word for “vulture chow.”

The 3,000-mile Dakar Rally used to be between Paris and Dakar, Senegal, but had to be moved to South America in 2009 because of terrorism threats. You can take part with pretty much any land vehicle you fancy, from trucks and normal cars to motorcycles and quads. It’s a two-week off-road race with speeds averaging 100 miles per hour, and unholy insanity is pretty much its status quo. Since its inception in 1978, the Dakar Rally has claimed over 50 lives.

The ways it can kill your ass are varied and plentiful: People have died of heat stroke, heart attacks, and thirst, or a combination of all three plus terror caused by simply getting lost. Spectators aren’t any safer: In this year’s rally, 10 people were injured right off the bat when an out-of-control car went careening into the stands. That’s right: This is a race that isn’t even safe to watch.

The photographer is this picture’s only confirmed survivor.

#1. You Can Spend A Week Running Through The Deadliest Jungle In The World

It’s called the Jungle Marathon, which is a much more descriptive name than “freediving” but still undersells exactly what madness is taking place. For one thing, a marathon is 26.2 miles — this one is a seven-day, 137-mile trek. So, more than five of those. The “jungle” part is accurate, though — you’re doing the whole jaunt through the Amazon, the long-reigning champion in the “green hell” weight class of geographical hellholes.

The knee-high swamp wins in the “brown-hell” class.

So, in this particular competition, your race is not so much for the prize as it is for getting to the goal in one piece, and your most dangerous opponent is Mother Nature herself. Participants face challenges like the Jaguar Alley, a portion of the race that goes through known jaguar territory, where runners are advised to avoid running too far away from each other and armed guards stand watch at night (yes, of course they stay overnight in the area. How else could the jaguars get a sporting chance?) To date, no one has been eaten by a jaguar (as far as we know), but multiple people have seen them, and more than one competitor has reported being stalked by them.

The race directors do their best to make sure the journey is safe-ish, but as shitty as humanly possible; after all, this is an extreme sports event, so things tend to — and are meant to — leave sports competition territory and veer screaming into disaster-movie land. Not that they have to try too hard. The most recurring attacks from the local fauna come from wasps, which pretty much attack every single runner in the race. It’s not unheard of for a runner to limp on with 18 stingers sticking out of them.

Other wildlife that takes little to no shit from human passersby include supersized ants, ticks, snakes, and venomous scorpions. There have even been multiple reports of freaking stingray attacks (yes, you’re splashing through water in many parts of the race). Or maybe nothing will sting or bite you, and you just have to escape an angry wild pig by climbing up a tree. Did we mention that many trees in the Amazon are poisonous and can cause numbness just from touching them? Good luck running with a body you can no longer feel, buster! On the other hand, not feeling your legs might be a good thing, because the jungle does a person’s body absolutely no favors.

“Why, peeling and discarding excess toes doesn’t hurt at all!”

And then there’s the heat and humidity, which by itself would make the run a nightmare even if all other conditions were ideal. You don’t get help, either — competitors have to haul their own gear throughout the race. As such, the completion rate of the Jungle Marathon is predictably low: In 2012, 60 people started the race. Only 11 managed to finish it in full. And that’s picking from a group of people already willing to travel around the world to compete in such an event in the first place — the craziest of the crazy, in other words.

We like to imagine the other 49 people took two steps into the jungle, stopped, blinked, and said, “Wait, what the fuck am I doing?”

For as long as competitions have been a thing, there have been those who just need to make them infinitely more painful to perform. See what we mean in The 6 Most Terrifying Historical Car Races and 5 Bizarrely Masochistic Races People Run For ‘Fun’.

Source: http://allofbeer.com/5-balls-out-insane-competitions-you-wont-believe-are-real/

from All of Beer https://allofbeer.wordpress.com/2018/10/27/5-balls-out-insane-competitions-you-wont-believe-are-real/

0 notes

Text

Notes on a Shipwreck

Davide Enia | translated by Antony Shuggar | an excerpt adapted from Notes on a Shipwreck: A Story of Refugees, Borders, and Hope | Other Press | February 2019 | 16 minutes (4,334 words)

On Lampedusa, a fisherman once asked me: “You know what fish has come back? Sea bass.”

Then he’d lit a cigarette and smoked the whole thing down to the butt in silence.

“And you know why sea bass have come back to this stretch of sea? You know what they eat? That’s right.”

And he’d stubbed out his cigarette and turned to go.

There was nothing more, truly, to be said.

What had stuck with me about Lampedusa were the calluses on the hands of the fishermen; the stories they told of constantly finding dead bodies when they hauled in their nets (“What do you mean, ‘constantly’?” and they’d say, “Do you know what ‘constantly’ means? Constantly”); scattered refugee boats rusting in the sunlight, perhaps nowadays the only honest form of testimony left to us — corrosion, grime, rust — of what’s happening in this period of history; the islanders’ doubts about the meaning of it all; the word “landing,” misused for years, because by now these were all genuine rescues, with the refugee boats escorted into port and the poor devils led off to the Temporary Settlement Center; and the Lampedusans who dressed them with their own clothing in a merciful response that sought neither spotlights nor publicity, but just because it was cold out and those were bodies in need of warmth.

*

Haze blurred our line of sight.

The horizon shimmered.

I noticed for what must have been the thousandth time how astonished I was to see how Lampedusa could unsettle its guests, creating in them an overwhelming sense of estrangement. The sky so close that it almost seemed about to collapse on top of us. The ever-present voice of the wind. The light that hits you from all directions. And before your eyes, always, the sea, the eternal crown of joy and thorns that surrounds everything. It’s an island on which the elements hammer at you with nothing able to stop them. There are no shelters. You’re pierced by the environment, riven by the light and the wind. No defense is possible.

It had been a long, long day.

I heard my father’s voice calling my name, while the sirocco tossed and tangled my thoughts.

*

I happened to meet the scuba diver at a friend’s house.

It was just the two of us.

The first, persistent sensation was this: He was huge.

His first words were these: “No tape recorders.”

He went over and sat down on the other side of the table from me and crossed his arms.

He kept them folded across his chest the whole time.

“I’m not talking about October third,” he added, his mouth snapping shut after these words in a way that defied argument.

His tone of voice was consistently low and measured, in sharp contrast with that imposing bulk. Sometimes, in his phrases, uttered with the sounds of his homeland — he was born in the mountains of the deepest north of Italy, where the sea is, more than anything else, an abstraction — there also surfaced words from my dialect, Sicilian. The ten years he’d spent in Sicily for work had left traces upon him. For an instant, the sounds of the south took possession of that gigantic body, dominating him. Then the moment would come to an end and he’d run out of things to say and just stare at me, in all his majesty, like a mountain of the north.

Before your eyes, always, the sea, the eternal crown of joy and thorns that surrounds everything.

He’d become a diver practically by sheer chance, a shot at a job that he’d jumped at immediately after completing his military service.

“We divers are used to dealing with death, from day one they told us it would be something we’d encounter. They tell us over and over, starting on the first day of training: People die at sea. And it’s true. All it takes is a single mistake during a dive and you die. Miscalculate and you die. Just expect too much of yourself and you die. Underwater, death is your constant companion, always.”

He’d been called to Lampedusa as a rescue swimmer, one of those men on the patrol boats who wear bright orange wetsuits and dive in during rescue operations.

He told me just how tough the scuba diving course had been, lingering on the mysterious beauty of being underwater, when the sea is so deep that sunlight can’t filter down that far and everything is dark and silent. The whole time he’d been on the island, he’d been doing special training to make sure he could perform his new job at an outstanding level.

He said: “I’m not a leftist. If anything, the complete opposite.”

His family, originally monarchists, had become Fascists. He, too, was in tune with those political ideas.

He added: “What we’re doing here is saving lives. At sea, every life is sacred. If someone needs help, we rescue them. There are no colors, no ethnic groups, no religions. That’s the law of the sea.”

Then, suddenly, he stared at me.

He was enormous even when he was sitting down. “When you rescue a child in the open sea and you hold him in your arms . . .”

And he started to cry, silently.

His arms were still folded across his chest.

I wondered what he could have seen, what he’d lived through, just how much death this giant across the table had faced off with.

After more than a minute of silence, words resurfaced in the room. He said that these people should never have set out for Italy in the first place, and that in Italy the government was doing a bad job of taking them in, wastefully and with a demented approach to issues of management. Then he reiterated the concept one more time: “At sea, you can’t even think about an alternative, every life is sacred, and you have to help anyone who is in need, period.” That phrase was more than a mantra. It was a full-fledged act of devotion.

Local Bookstores Amazon

He unfolded his words slowly, as if they were careful steps down the steep side of a mountain.

“The most dangerous situation is when there are many vessels close together. You have to take care not to get caught between them because, if the seas are rough, you could easily be crushed if there’s a collision. I was really in danger only once: There was a force-eight gale, I was in the water with my back to a refugee boat loaded down with people, and I saw the hull of our vessel coming straight at me, shoved along by a twenty-five-foot wave. I moved sideways with a furious lunge that I never would have believed I could pull off. The two hulls crashed together. People fell into the water. I started swimming to pick them up. When I returned from that mission, I still had the picture of that hull coming to crush me before my eyes. I sat there on the edge of the dock, alone, for several minutes, until I could get that sensation of narrowly averted death out of my mind.”

He explained that when you’re out on the open water, the minute you reach the point from where the call for help was launched, you invariably find some new and unfamiliar situation.

“Sometimes, everything purrs along smoothly, they’re calm and quiet, the sea isn’t choppy, it doesn’t take us long to get them all aboard our vessels. Sometimes, they get so worked up that there’s a good chance of the refugee boat overturning during the rescue operations. You always need to manage to calm them down. Always. That’s a top priority. Sometimes, when we show up on the scene, the refugee boat has just overturned, and there are bodies scattered everywhere. So, you have to work as quickly as you can. There is no standard protocol. You just decide what to do there and then. You can swim in a circle around groups of people, pulling a line to tie them together and reel them in, all at once. Sometimes, the sea is choppy and they’ll all sink beneath the waves right before your eyes. In those cases, all you can do is try to rescue as many as you can.”

I have the distinct sensation that I’m face-to-face with human beings who carry an entire graveyard inside them.

There followed a long pause, a pause that went on and on. His gaze no longer came to rest on the wall behind me. It went on, out to some spot on the Mediterranean Sea that he would never forget.

“If you’re face-to-face with three people going under and twenty-five feet farther on a mother is drowning with her child, what do you do? Where do you head? Who do you save first? The three guys who are closer to you, or the mother and her newborn who are farther away?”

It was a vast, boundless question.

It was as if time and space had curved back upon themselves, bringing him face-to-face with that cruel scene all over again.

The screams of the past still resonated.

He was enormous, that diver.

He looked invulnerable.

And yet, inside, he had to have been a latter-day Saint Sebastian, riddled with a quiverful of agonizing choices.

“The little boy is tiny, the mother extremely young. There they are, twenty-five feet away from me. And then, right here, in front of me, three other people are drowning. So, who should I save, then, if they’re all going under at the same instant? Who should I strike out for? What should I do? Calculate. It’s all you can do in certain situations. Mathematics. Three is bigger than two. Three lives are one more life than two lives.”

And he stopped talking.

Outside the sky was cloudy, there was a wind blowing out of the southwest, the sea was choppy. I thought to myself: Every time, every single time, I have the distinct sensation that I’m face-to-face with human beings who carry an entire graveyard inside them.

*

I tried calling my uncle Beppe, my father’s brother. We called each other pretty frequently. Often my uncle would ask me: “But why doesn’t my brother ever call me?” I’d answer: “He doesn’t even call me, and I’m his first-born son, Beppuzzo, it’s just the way he is.”

The phone rang and rang for more than a minute, with no answer.

I hung up and went back inside.

We ate dinner, tuna cooked in sweet-and-sour onions and a salad of fennel, orange slices, and smoked herring.

There were four of us sitting around the table: Paola, Melo, my father, and me.

We were at Cala Pisana, at Paola’s house. Paola is a friend of mine. She’s a lawyer who’s given up her practice and has lived on Lampedusa for years now. There, with her boyfriend Melo, she runs the bed and breakfast where I usually stay as my base of operations whenever I’m doing research on the island.

I was setting forth my considerations on that exceedingly long day, in a conversation with Paola. From time to time, Melo would nod, producing small sounds, monosyllabic at the very most. My father, on the other hand, made no sounds whatsoever. He was the silent guest. Patiently, with his gaze turned directly to the eyes of whoever was speaking, he displayed a considerable ability to listen that he’d developed in the forty-plus years he’d practiced his profession, cardiology. He invited people to tell him things just by the way he held his body.

I was considering out loud that everything happening on Lampedusa went well beyond shipwrecks, beyond a simple count of the survivors, beyond the list of the drowned.

“It’s something bigger than crossing the desert and even bigger than crossing the Mediterranean itself, to such a degree that this rocky island in the middle of the sea has become a symbol, powerful and yet at the same time elusive, a symbol that is studied and narrated in a vast array of languages: reporting, documentaries, short stories, films, biographies, postcolonial studies, and ethnographic research. Lampedusa itself is now a container-word: migration, borders, shipwrecks, human solidarity, tourism, summer season, marginal lives, miracles, heroism, desperation, heartbreak, death, rebirth, redemption, all of it there in a single name, in an impasto that still seems to defy a clear interpretation or a recognizable form.”

Lampedusa itself is now a container-word: migration, borders, shipwrecks, human solidarity, tourism, summer season, marginal lives, miracles, heroism, desperation, heartbreak, death, rebirth, redemption, all of it there in a single name.

Papà had remained silent the whole time. His blue eyes were a well of still water in whose depths you could read no judgment whatsoever.

Paola had just poured herself an espresso.

“Lampedusa is a container-word,” she repeated under her breath, nodding to herself more than to me.

She sugared her coffee and went on with her thoughts. “And in a container, sure enough, you can put anything you like.”

Little by little, with a gradual rising tone, her voice grew louder, and the pace of her words became increasingly relentless.

“In the container called Lampedusa, you really can fit everything and the opposite of everything. Take the Center where the young people are brought after they land. Do you remember? You saw it when you came back here the year after the Arab Spring.”