#gilded age 2.0

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

youtube

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sometimes I like to check the inflation calculator to check my current salary versus what some corporations think is a fair wage (which is usually frozen like 20 years ago if they're a shit company)

And my very first office job was $9.16 an hour which if you adjust for inflation would have the same spending power as $19.18 an hour in 2025

That's how much lower wage jobs have stagnated in the past 20+ years

If you currently have a job that pays $9 an hour in 2025 in the US then you have the same spending power of $5 an hour due to the cost of living and inflation

Truly anything less than $20 is just indentured servant 2: electric boogaloo

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

i should have the government-protected right to call my work up and be like, yeah i need the week off. yeah it's the disorders. yeah i'm gonna go to the beach and play arcade games now all the kids are back in school. which i suppose technically i CAN do but it's called "calling out" (feel bad for putting pressure on my coworkers) (not that bad, because they'll be under pressure regardless, but still) or "scheduling time off" (relies on my brain having any semblance of normalcy and ability to do things in a rational, timely manner)

#piri.txt#ive been applying to places and all the entry level jobs are like teehee actually you need 1-2 years relevant experience to apply for this!#do you guys remember when words meant things. do you guys remember when we weren't in the gilded age 2.0

1 note

·

View note

Text

Why is the only "shocking" scenario i can think of oscar outing john and getting him into prison, lichrally nobody would care

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

LIAFF SPECIAL - I titoli più attesi di Giugno 2025!

Carissimi lettori, ben ritrovati con un nuovo appuntamento con LIAFF Special, dove andremo a scoprire i titoli più interessanti del nuovo mese. Vi starete domandando come sia possibile, ebbene sì, siamo a Giugno, a metà dell'anno. Sta per arrivare il caldo, le giornate al mare e le montagne di gelato. Ma ciò non ci priva di goderci di nuovi ed entusiasmanti titoli per il grande e il piccolo schermo, fra debutti intriganti e ritorni attesi, specialmente in televisione. Quindi sedetevi e godetevi la lista dei titoli più interessanti di Giugno!

CINEMA

youtube

Ballerina (Cinema - 12 Giugno)

Il franchise di John Wick non si ferma e, dopo averci regalato quattro film, uno più bello dell'altro, si amplia, offrendoci un nuovo punto di vista all'interno della saga. Ballerina, diretto da Len Wiseman, avrà come protagonista Ana de Armas, in una storia di vendetta che si ambienterà fra il terzo e il quarto capitolo della saga principale. Nel cast abbiamo sia vecchi volti, come Keanu Reeves, il compianto Lance Reddick (qui nel suo ultimo ruolo), Ian McShane e Anjelica Huston, ma anche new-entry, come Norman Reedus, Gabriel Byrne e Catalina Sandino Moreno.

youtube

Dragon Trainer (Cinema - 8 Giugno [anteprima], 13 Giugno)

Fra le saghe più importanti di Dreamworks vi è Dragon Trainer, iniziata nel 2010 e che conta tre film di grande successo. E, seguendo le orme della Disney (si spera in meglio), Dreamworks ha deciso di portare in live-action il primo film, mantenendone il titolo e la storia, almeno a grandi linee. Il cast vanta giovani nomi, come Mason Thames, che interpreterà il protagonista Hiccup, e Nico Parker, ma anche nomi più noti, come Nick Frost e Gerard Butler, che riprenderà i panni di Stoick, e, stando alle prime recensioni, sembra essere davvero interessante. Da tenere d'occhio.

youtube

28 Years Later (Cinema - 18 Giugno 2025)

Fra le saghe che ripartono in questo 2025 c'è quella di 28 Days Later, film britannico del 2002, nonchè uno dei titoli più apprezzati di quelli sugli zombie. Ebbene, diciotto anni dopo 28 Weeks Later, si ritorna nella Gran Bretagna post-apocalittica con 28 Years Later, che vede la regia dello storico regista della saga Danny Boyle e sceneggiatura di Alex Garland. Con protagonisti Jodie Comer, Aaron Taylor-Johnson e Ralph Fiennes, il film ci mostrerà le sorti della Gran Bretagna a quasi trent'anni dall'inizio dell'epidemia, e sarà l'inizio di una nuova trilogia, con un secondo film già previsto per il 2026.

youtube

F1 (Cinema - 25 Giugno)

Dopo gli aerei di Top Gun: Maverick, Joseph Kosinski si butta sulle auto della Formula 1, portando alla luce un progetto in produzione da diversi anni. Prodotto da Apple TV, F1 è un film che promette di essere un esperienza cinematografica per gli amanti delle gare di Formula 1 e non solo. Il film vanta nel cast Brad Pitt, Javier Bardem e Kerry Condon e anche qualche cameo direttamente dal mondo della Formula 1. Un progetto interessante.

youtube

M3gan 2.0 (Cinema - 26 Giugno)

Nel 2022 uscì nelle sale M3gan, film horror che parlava di una bambola robot che diventa una spietata assassina. E, visto il successo riscontrato, si è pensato di cambiare il tono del racconto, trasformandolo in un action-comedy molto cattiva, il che genera parecchia curiosità per questo sequel. M3gan 2.0 vedrà la tembile M3gan scontrarsi con Amelia, un robot creato con la sua stessa tecnologia. Si spera che sia divertente.

SERIE TV

youtube

The Waterfront (Netflix - 19 Giugno)

Le uscite seriali di Giugno non sono moltissime, ma a quanto pare sono tutte concentrate dopo la seconda metà del mese. Infatti Netflix decide di rilasciare proprio in quel periodo una delle sue serie più attese, il drama The Waterfront. Creata da Kevin Williamson (Dawson's Creek, Scream), la serie racconta della famiglia Buckley, la quale dovrà lottare con ogni mezzo per tenere in piedi il loro business, con un cast capitanato da Holt McCallany, Maria Bello, Melissa Benoist e Jake Weary.

youtube

The Gilded Age 3 (Now - 23 Giugno)

Uno dei titoli più attesi dell'estate è senz'altro la terza stagione di The Gilded Age, il dramma storico di HBO creato da Julian Fellowes. La serie ripartirà dagli eventi della seconda stagione, con nuove storyline, nuovi personaggi e insidie lungo la strada, e ritroveremo personaggi amatissimi, come l'ambiziosa Bertha Russell (Carrie Coon) o le due sorelle Agnes (Christine Baranski) e Ada Brook (Cynthia Nixon).

youtube

Ironheart (Disney+ - 25 Giugno)

A seguito del successo di Daredevil: Born Again, la Marvel ci riprova anche nel mondo seriale con Ironheart, serie incentrata sul personaggio di Riri Williams (Dominique Thorne), già vista in Black Panther: Wakanda Forever. La serie, composta da sei episodi, che verranno rilasciati in due blocchi da tre ciascuno, esplorerà i primi passi da eroina della protagonista, la quale, grazie alle sue conoscenze tecnologiche, si dovrà scontrare con un avversario che userà la magia. Una combinazione strana, ma potenzialmente interessante.

youtube

The Bear 4 (Disney+ - 26 Giugno)

Grandemente attesa dal pubblico, la pluripremiata serie "comedy" The Bear torna a fine mese con la quarta stagione, la quale in Italia arriverà in contemporanea con gli Stati Uniti. A seguito del finale, che lasciava in sospeso la questione riguardante la prima recensione ufficiale del The Bear, Carmy, Sidney, Richie e gli altri protagonisti dovranno affrontare nuove sfide, sia lavorative che personali, senza dimenticare l'amore per la cucina che caratterizza questa serie.

youtube

Squid Game 3 (Netflix - 27 Giugno)

E per ultimo, ma non per questo meno importante, abbiamo la terza ed ultima stagione di Squid Game, la serie coreana di successo della piattaforma in rosso. A seguito della chiaccheratissima seconda stagione, la storia ha preso nuove e oscure direzioni, con nuovi letali giochi in arrivo per Gi-hun e gli altri protagonisti. E voi siete pronti a giocare per l'ultima volta?

#cinema#serie tv#ballerina#dragon trainer#28 years later#f1#m3gan 2.0#the waterfront#the gilded age#ironheart#the bear#squid game#LIAFF: LIAFF SPECIAL#Youtube

0 notes

Text

Hello everybody! Surprised to see me post something not Seabird related? Well sometimes drawing the same things over and over again gets a little tiring, so to clear my head (and to remind myself to draw legs once in while) I’d tried to draw other owl house stuff. During this break times I’d actually end up drawing other owl house creators Au’s, and I decided to clean up these drawings together and compile them into one big illustration. Think of this post as a sorta tribute to creators that inspire me. And don’t worry, Seabird part 3 will still come out Monday.

First up, the Monster high AU by @dazeddoodles

As the title suggests, it’s an AU that combines the G1 Monster high with the Owl house series. I was a huge Monster High fan when I was younger, so this AU was a real treat. I’m really sad they decided to discontinue it, as I think this AU is really cute. I love the designs too, Raine is my favorite. I kinda just wanted to draw some cute interactions, a young Eda and Raine interacting, Gus and Willow giving Hunter “a hand’ and Amity flirting with Luz (in her own way). Drawing this AU was a lot of fun and did inspire me to rewatch some of the old Monster high specials.

Pittwins AU by @nikolutke

This AU is much darker. The idea of the story is what if Hunter and Luz weren’t resurrected at the end of the series and wandered around the Boiling Isles as ghosts. I love Nikolutke designs for Ghost Luz and Hunter, they’re both haunting and really sad. Plus the idea exploring the Owl house characters reactions towards the death of a love one is really fascinating concept. I kinda explored that idea with these drawings, in this case Eda and Darius reactions. I feel like Eda would be out of her mind with grief, as she was forced to watch Luz’s death first hand. I think she’d feel a lot of guilt too, thinking she failed to protect Luz. I also wonder if Kings Titans powers allows him to see the dead, could be possible. As for the other illustration, I think Darius would probably isolated himself and grieve quietly, contemplating what he could of done differently, and if he could have saved Hunter in time.

The Gilded Cage by @catboymoments

I’ve been fan of both their next gen au and this one, but I decided to post one about the Gilded age au. The basic idea of this AU is the classic “What if Belos found Luz instead of Eda” concept. A lot of these AUs tend to go the route of “Luz becomes Belos 2.0” as someone who loves Luz, I’m sad people just think she’d just instantly become a villain if left unguided. I’m really that this AU went into a different direction and actual kept Luz’s personality and made Luz someone who’s trying to help the Isles and wants to protect her friends from Belos wrath. The one on the left is Lilith and Luz interacting, I like to think Lilith sees a lot of Eda in Luz, and makes her think of the good times before everything got complicated. The one on the right is Luz and Hunter, with the former trying to convince the latter to question Belos control. I love in this AU that despite Belos attempts to put the, against each other, they still have each others back no matter what! Their siblings no matter what universe they’re in!

And of course the classic (pun intended) The Mythology AU by @turquoisespace35

This AU is Huntlow story set in Greek mythology. Hunter in this AU is the half human-gorgon offspring of the human Caleb and gorgon Evelyn. Willow is sent to his location to kill him but (of course) they fall in love instead. The story has a lot of twists and turns, so I suggest you check it out if you haven’t already. The left drawing is Caleb and Evelyn interacting together. I don’t know if this work but I like to think the two were able to somewhat interact with each other by Caleb looking through mirror. I of course had to draw the love birds Hunter and Willow interacting together. The one on the top right is a little bit of a spoiler but I decided to draw Lilith and Edalyns in their goddess forms, I love that Lilith plays the role of Athena and acts a caretaker to Hunter. I drew her getting a little emotional about Hunter finally being free, as any cool Aunt should.

And to those who are just hear to see the Seabird AU, here’s a preview drawing of part 3 of chapter 10. I don’t think Edas really enjoying this part though lol.

Anyway, hope you guys this more unusual post, I just wanted to draw something a little different this time and pay tribute to some of the artists that have inspired me.

Edit: Chapter 10 part 3 of the Little Seabird is out now. In case you’re interested in seeing my work, I’ve left a link:

Chapter 10, part 3:

And if you want to read from the beginning, here’s a link to the first page:

Beginning:

#luz noceda#toh luz#amity blight#toh amity#luz x amity#lumity#hunter toh#hunter owl house#willow park#toh willow#toh gus#augustus porter#gus porter#lilith clawthorne#toh lilith#toh eda#toh edalyn#edalyn clawthorne#eda clawthorne#eda the owl lady#raine whispers#toh raine#toh raeda#raine x eda#darius deamonne#toh darius#toh king#king clawthorne#the owl house#toh

276 notes

·

View notes

Text

A year in illustration (2024), Part three

If you'd like an essay-formatted version of this post to read or share, here's a link to it on pluralistic.net, my surveillance-free, ad-free, tracker-free blog:

https://pluralistic.net/2024/12/07/great-kepplers-ghost/art-adjacent

Part one

Part two

Live Nation/Ticketmaster is buying Congress

I had a lot of fun scouring Victorian woodcuts for cool tentacles to add to this image. The garish concert lights in the background were a fun find – I was halfway through using them when I realized that the image came from my old pal Matt Biddulph, who has many claims to fame, but my favorite is that he once sarcastically called the area in Hackney where some tech startups were clustered "Silicon Roundabout" and then experienced the monkey's paw curse of having the government turn this into an official designation.

https://pluralistic.net/2024/04/30/nix-fix-the-tix/#something-must-be-done-there-we-did-something

(Image: Matt Biddulph, CC BY-SA 2.0; Flying Logos, CC BY-SA 4.0; modified)

The specific process by which Google enshittified its search

Around April, I realized I needed a visual signifier for "enshittified Google" – I created a cartoon mascot with the head of a poop emoji, colored in the original Google logo colors. I put him into "The Junior Partner Speaks," an old ad for Pacific Woolens and Worsteds, which I've since used several times:

https://craphound.com/images/juniorpartner.jpg

I'm very fond of using the homely old original Google logo as a way to differentiate pre-enshittificatory Google from modern, enshittocene Google.

https://pluralistic.net/2024/04/24/naming-names/#prabhakar-raghavan

Podcasting "Capitalists Hate Capitalism"

Real Gilded Age corruption-heads will instantly recognize the editorial cartoon image of Boss Tweed as a suited figure with a sack of money for a head; his body language is impeccable, conveying a sneering disregard for decency and others' wellbeing. He works very well inserted into this tapestry of feudal peasants threshing grain.

https://pluralistic.net/2024/04/18/in-extremis-veritas/#the-winnah

No, "convenience" isn't the problem

It's stupidly, unnecessarily hard to find hi-rez scans of Rube Goldberg cartoons online, but this one is perfect and it was a delight to lovingly crop out all its little details. Throw in Cryteria's HAL 9000 and a Matrix code waterfall and you've got a perfect image of the complex, hostile traps of digital systems.

https://pluralistic.net/2024/04/12/give-me-convenience/#or-give-me-death

The unexpected upside of global monopoly capitalism

This one's pretty subtle! I mostly just added the monocle, mustache and top-hat to the fallen head of Goliath in Bosse's 17th century engraving of the triumphant David. The planet Earth in David's sling is a NASA image and thus in the public domain.

https://pluralistic.net/2024/04/10/an-injury-to-one/#is-an-injury-to-all

How to shatter the class solidarity of the ruling class

Goodness, but "canceled" is a tedious cliche. If you must describe someone being ejected from polite society, please consider the far more delightful "defenestrated," not least because the many paintings and etchings of The Defenestration of Prague gives us a lot of public domain visual material to work with when illustrating such events.

https://pluralistic.net/2024/04/08/money-talks/#bullshit-walks

(Image: KMJ, CC BY-SA 3.0, modified)

General Mills and cheaply bought "dietitians" co-opted the anti-diet movement

The minute I saw this unsourced midcentury commercial illustration of a scientist working in a chem lab, I knew I'd get a lot of mileage out of it; I spent a long flight productively slicing it onto layers so that I could replace his head and put arbitrary objects in his flask:

https://craphound.com/images/labflask.jpg

I've used him before, but putting the Trix rabbit's head on him and sticking a box of Cocoa Puffs in the flask worked great.

https://pluralistic.net/2024/04/05/corrupt-for-cocoa-puffs/#flood-the-zone-with-shit

Too big to care

I spent the whole flight to SXSW last year slicing up a super hi-rez (10,000px wide!) image of Hieronymus Bosch's "Garden of Earthly Delights," slicing out individual demons, with special attention to the hoof-footed, anus-baring demon in a hat with a whole secret demonic clubhouse in its rectal cavity. At the end of that flight, I had a very funny conversation with my perplexed seatmate, who was dying to know what the actual fuck I was working on.

The background here is made up of desaturated, magnified brushstrokes from Van Gogh's "Starry Night."

https://pluralistic.net/2024/04/04/teach-me-how-to-shruggie/#kagi

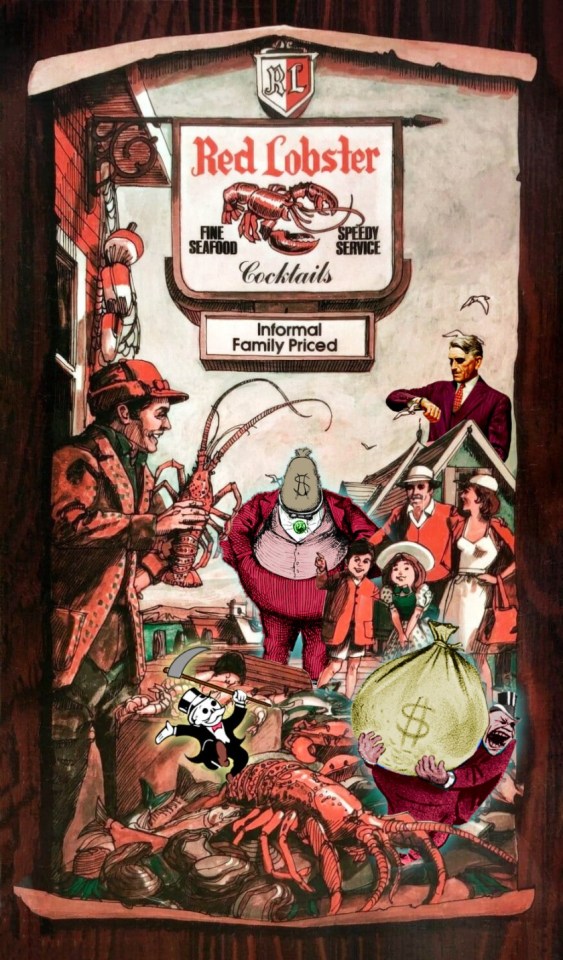

Red Lobster was killed by private equity, not Endless Shrimp

I inserted a rogue's gallery of "evil boss types" from various editorial cartoons into this vintage Red Lobster ad, including Boss Tweed, an impatient guy from a midcentury John Falter commercial illustration, possibly for a radio station (?) and a William Gropper sketch for a cartoon making fun of the business lobby's opposition to the New Deal.

https://pluralistic.net/2024/05/23/spineless/#invertebrates

You were promised a jetpack by liars

The newsie with the great grin makes a reappearance in this one, beneath a jetpack flyer taken from a 1928 Amazing Stories cover by R Frank Paul. The control panel is one of several midcentury electronics consoles I've spent idle hours cropping out (this one comes from a Schlitz ad depicting a HAM radio enthusiast). The hypnotic head is from the October, 1953 cover of Doll-Man, likely by Reed Crandall. I started playing around with halftoning with this one, on the background, as a way of hiding the JPEG artifacts that emerged when I uprezzed small source images. It worked really well.

https://pluralistic.net/2024/05/17/fake-it-until-you-dont-make-it/#twenty-one-seconds

AI "art" and uncanniness

I was so happy with how the extra fingers on this Victorian woodcut of a hand on a Oujia board planchette came out. And the green tinting worked perfectly with the Code Waterfall background.

https://pluralistic.net/2024/05/13/spooky-action-at-a-close-up/#invisible-hand

Part four

#art#collages#public domain#creative commons#cc#fair use#copyfight#visual communications#illustration#pluralistic illustrations 2024

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

Late in 1774, Lord Robert Clive was found dead in his London townhouse. Rumors flew that conscience had finally compelled the rapacious conqueror to take his own life. Having just arrived in Pennsylvania from England, Thomas Paine recalled how the riches Clive wrested through “murder and rapine” and “famine and wretchedness” in India had enveloped him in the “sunshine of sovereign favor” at home, allowing him to enter into further “schemes of war … and intrigue” to amass an “unbounded fortune.” In the end, however, “guilt and melancholy” had proved “poisons of quick despatch.”

Clive was a reckless fortune-hunter in the British East India Company (EIC), the chartered monopoly company trading in the Indian Ocean region—heavily armed, to compel trade on its terms. When the British and French went to war globally in 1756, their rivalrous companies in India did, too, and Clive secured the EIC’s first major territory in Bengal in 1757. Long-held company towns at the subcontinent’s edges expanded into a company-owned state.

The company’s shareholders sat in the British Parliament and were politically powerful. Those who rose up in it acquired power as well. Plunder of gold and jewels and a rich annuity in land revenue enabled Clive to secure an Irish barony, a country estate in Shropshire, and a seat in Parliament, as well as seats for his friends. The term for such nouveaux riches, “nabob”—a corruption of the Hindustani word nawab, or prince—captured their political presumption.

This was the Britain that Americans rebelled against.

Since the launch of Trump 2.0, both supporters and critics have analogized its unapologetic embrace of financial and tech titans to America’s Gilded Age. Others see in the administration’s ambitions in Greenland and Panama a throwback to the 19th-century private contractors of colonialism. But the 19th century was itself a new twist on an older oligarchic model exemplified by Clive. Private contracting is in the DNA of the modern state structures that Americans adopted—forgetting that they had rebelled not just against monarchy but also an oligarchic Parliament. Revisiting that foundational struggle shifts our perspective on the threat oligarchy poses today and the tactics needed to contend with it.

Traditional monarchs were corporate bodies in their own right, expressing the body politic in their personal form. From the 16th century, the British monarchy also relied on another kind of corporation, the chartered monopoly company, to pursue interests abroad, including the EIC, Virginia Company, Massachusetts Bay Company, Royal African Company, and Hudson’s Bay Company. Members of such companies enormously influenced the government bureaucracy that began to emerge to address the questions of trade and war that their activities sparked. Finally, with the 1688-89 Glorious Revolution, Parliament, controlled by wealthy elites also involved in such enterprises, dramatically curbed kingly authority; sovereignty migrated from the king’s person to the nascent institutions of the modern state, a new form of continuous public power above the ruler and the ruled.

This state was an oligarchy. The aristocrats who controlled Parliament used it to usurp the common rights of ordinary people, passing thousands of laws privatizing land—an internal colonialism that displaced masses of people, many of whom took their memory of oligarchic injury to North America, where they in turn displaced Indigenous inhabitants. The state also depended on contractors and corporations such as the EIC for the military and financial organization that it still lacked. Corporations’ interests in Asia, Africa, and the Americas were entangled with and dependent on Britain’s diplomatic, military, and political pursuits. Apart from trade and conquest, such companies bought, sold, and leased sovereignty like a commodity, as, for instance, with the EIC’s creation and sale of the princely state of “Jammu and Kashmir” to its allies in its conquest of Punjab.

In short, corporations were the new state’s partners in governance. The British state was Parliament, an emerging fiscal-military bureaucracy, and the Crown, plus corporations (including the Royal Mint and the Bank of England) and private contractors and financiers. In this sense, it, too, had a corporate form. It’s impossible to say where the state ended and the private sphere began. Great landowners and merchant oligarchs sat in Parliament but also held wide, unsupervised local powers as lord lieutenants, sheriffs, justices of the peace. Such unpaid positions layered state authority on their holders’ local social status and private wealth. They secured compliance with the threat of legitimate force, even though they did not always see themselves primarily as agents of the state and their power did not derive solely from their office.

Most Americans know that when Parliament asked the colonists to help fund debt accrued in the massive Seven Years’ War, which lasted until 1763, they cried, “No taxation without representation!” But ordinary Britons were also incensed by the hot mess of private wealth and state power in this time, which saw the most consistently negative depictions of big business ever. Followers of the radical politician John Wilkes likened the alliance among elites across the state, land, commerce, finance, and industry to a gang of robbers plundering society. Popular reform movements involved petitions and pamphleteering but also marches and mass meetings incorporating song and religious feeling—crowd politics.

Airing of the EIC’s corruption and cruelties as it teetered on the verge of bankruptcy in 1772, threatening the nation’s finances, fueled censure of figures such as Clive. Sharply attacking the company, the philosopher Adam Smith theorized a society in which a private economic realm free from state intervention would drive world-historical progress. The Wealth of Nations, published in 1776, called not for recognition of boundaries between the public and private spheres but the creation of such boundaries—the liberal political-economic principle that shapes many Americans’ expectations of the relationship between government and society today.

Paine wrote about Clive’s death against this backdrop of ire against oligarchy in Britain and the Colonies—months before he drafted Common Sense, the incendiary pamphlet released in 1776 as Americans revolted. Fury about the EIC’s abuses fueled anger at Parliament’s treatment of the Colonies. In 1778, Paine noted the poetic justice that Indian tea had kindled a war in America “to punish the destroyer.” The villain was not just King George III but the oligarchy that had already checked his power.

After the Revolutionary War, the British public persisted in attacking military contractors, for reaping profits despite the country’s humiliating defeat, and financiers, for defrauding the public by exploiting their relationships with government offices for personal gain. When contracting exploded during the long wars against France from 1793 to 1815, popular radicals such as William Cobbett condemned this system of “Old Corruption,” dubbing the nexus of power, patronage, and wealth “the THING.”

In the face of sustained outcry, new institutions did evolve to exert control over the state’s private partners. The EIC, for instance, was integrated into the bureaucratic structure of the state, and new state offices, the Colonial and Foreign offices, were formed to engage in activities previously entirely outsourced to corporations.

Americans, too, worked to create institutions that would limit the potential for despotism. To be sure, the “articles” incorporating their government echoed the company charters that governed the earliest Colonies and gave Americans their understanding of a constitution: a written charter from a sovereign ordaining and setting out the limits of a government. But now “the people,” rather than the monarch, were the sovereign. Both countries also pursued civil service reform in the 19th century, meaning fewer political appointees and buying of positions—the creation of the professionalized government bureaucracy that the Trump administration is attempting to undo.

The process of separating business from state activity took time and remained ever incomplete because these states were designed for the pursuit of territorial expansion and maintenance of power within that territory through a security establishment. Both governments thus continued to invest in military industry and depend on contractors and corporate control of media, and a revolving door kept elites in these fields intimate with government offices. While the robber barons of the Gilded Age shaped U.S. industrial policies and westward expansion, monopoly companies continued to undertake British colonial expansion, profiting from government support while relieving the government of responsibility. Cecil Rhodes’s British South Africa Company is merely the most famous, or infamous, of the companies that dominated this era.

Rhodes’s machinations triggered a grueling war in South Africa in which Britain prevailed only by recourse to scorched-earth tactics and concentration camps. Covering the war for the Manchester Guardian, the economist J.A. Hobson perceived that reckless imperialism was driven by oligarchs who hijacked foreign policy to serve their ends—inspiring Vladimir Lenin’s later critique of imperialism as the highest stage of capitalism. Such theorists grasped that asserting sovereignty uniformly across a bounded space was innately colonial, requiring the backing of military or security contractors and financiers. Voting was no guarantee of a democratic check on their power and policies, given the way that private donations swayed elections and that press barons cozy with the government manipulated public opinion in favor of jingoistic causes.

After World War I, a wised-up British public with a mass franchise and more consciously assertive press railed passionately against the sway of arms contractors who led the country into unnecessary conflicts. Again, imperial conflicts continued, albeit at times more covertly, to evade public scrutiny.

The public failed to dislodge oligarchic influence partly because it focused on tactics that liberalism prioritized at the expense of the more powerful tools it once wielded. From the 18th century, British reformers focused on franchise expansion as the key to changing Parliament’s composition and thus breaking the elite monopoly of state power. This emphasis on institutions of formal democracy was rooted in liberal ideals of political subjectivity: a highly individualized coherent self who formed his (and I mean “his,” up until after World War I) opinions rationally through careful reading of material produced by a presumptively free press. Institutionalized politics and secret balloting would deliver progress, liberal philosophers assured. This ideal meant moving away from the more fluid and collective sense of identity that drove the subversive street politics of the 17th and 18th centuries. Faith in print media facilitating debate among enlightened individuals undermined the emotive, melodramatic, and collective uses of more radically democratic forms of political expression, as did the state’s expanding capacity to police public spaces.

As World War II and the Cold War stoked doubts about liberal assumptions, the British New Left tried to revive collective forms of consciousness and action. In 1965, one of its leaders, the historian E.P. Thompson, identified the new “predatory complex” occupying the British state, with “its interpenetration of private industry and the State … [and] control over major media,” as a “new Thing.” A few years earlier, in his farewell address as U.S. president, Dwight D. Eisenhower had named the “military-industrial complex” entangling the interests of military contractors, the Defense Department, and politicians and distorting U.S. policy. The term was new, but the phenomenon was not.

Despite this warning, military contractors and financial elites continued to mold U.S. policy. If robber barons laid the foundation of Stanford University (the company town I write from), Pentagon contracts nurtured the rise of Silicon Valley through the present moment of tech billionaire-contractors lining up to kiss Donald Trump’s ring.

It’s no accident that tech billionaires style themselves as explorers on the frontiers of knowledge and space. Just as Clive molded himself on the conquistadors of narratives of the Age of Exploration, stories of the Clives and Rhodeses of empires past, long whitewashed by historians despite their ignominy in their own time, have made them models for men aspiring to enact the science fiction fantasies that were the Cold War update to adventure stories about colonial exploration of so-called dark continents.

Crony capitalism is a global imperial legacy. After 1947, corporations that had profited from military contracts under India’s colonial government cultivated a relationship with the new independent government, profoundly shaping its policies. Like the EIC, as the historian Mircea Raianu writes, the Tata Group acquired “attributes of sovereignty in the interstices of state power,” including company-owned towns established for mineral extraction and industrial production by displacing local inhabitants. Indeed, the group’s vision of systematic expansion across diverse industries—mills, land, mines, and more—was consciously imperial. Ordinary people and the government at times checked this influence—for instance, by resisting displacement and nationalizing airlines—to the extent that “corporate social responsibility” became a necessary public commitment for the Tatas. Today’s newer corporate billionaires, including Gautam Adani, wanted on charges of fraud and bribery in the United States, likewise rose through intimacy with the state. Their grip on the media, however, has all but banished acknowledgment that greedy tycoons loot the nation and exploit the common man. Today’s oligarchs unapologetically pursue and exhibit extravagant wealth, as masses of dispossessed Indians turn desperately to emigration to North America, like Britons in the 18th century.

The cult of MAGA deflects ordinary Americans’ frustration with a government that has long failed them toward such fellow victims of oligarchy, while Trump and his accomplices downsize the corporate U.S. government like maniacal management consultants to fully monopolize its capacities for their own ends.

Much distinguishes the current moment, not least that the stakes are planetary. But this is no freakishly unprecedented capture of a democracy by corporate power. The failure to recognize that the United States was born out of rebellion against oligarchy, not just monarchy, has long helped preserve oligarchic influence in the country. Even Sen. Bernie Sanders likens today’s oligarchs to the kings who ruled Americans by divine right before the 1770s, forgetting the oligarchic tyranny of Parliament.

Perhaps partly because Britons are more aware of their long struggle against oligarchy, as evident in Thompson’s invocation of Cobbett’s “Thing,” they have been more able to regulate campaign finance, albeit still not enough to prevent the rise of super-rich politicians such as Rishi Sunak (who married into India’s billionaire class), plutocratic control of the country’s biggest newspapers, and ideologically driven dismantling of the very state regulatory functions that could keep corruption in check.

Americans can mourn the loss of even the pretense of separation between government and big money. But the stark revelation of their entanglement is also an opportunity to rethink inherited concepts of normative governance and democracy.

The lesson of the past three centuries of recurring oligarchic influence on elections and governance is that democracy cannot be just about voting. Nor can we simply hope that the courts will challenge the avalanche of executive orders. Confronting oligarchy requires reclaiming the local forms of sovereignty sacrificed at its altar, which means collective action, forged through values of mutuality, outside electoral and legal institutions. It is worth considering whether British victims of 18th-century oligarchy might have more effectively defended the commons had they stayed rather than become settlers visiting their rage upon others abroad. Federal governments that are more substantively federal (i.e., not uniformly sovereign across their territory) yield less easily to oligarchic influence. The same applies to India.

To be sure, some of the Trump administration’s cheerleaders insist that dismantling the federal government is precisely about returning power to local communities and states. But the public goods at stake—food and air safety, public health—are necessarily federal. If the oligarchs call for privatizing the Postal Service and space exploration, the people should call for nationalizing X. Moreover, without reversion of federal taxes to local units, such rhetoric is merely cover-up for the administration’s actual effort to lay claim to local resources to serve its own ends. Local governments have already launched lawsuits against this imperial assertion.

Paine was too optimistic about Clive’s liberal subjectivity. Most probably, Clive did not die by his own hand but from overmedicating abdominal pain with opium. Conscience can’t stay the hand of unstable, violent, narcissistic personalities; it requires action, melodramatic action, from others. Some, however, are already pouring their melodramatic capacities into dark proclamations of a ruthless new order. Such despair in the world of print arises perhaps from the disappointed expectation of progress by the expected means. But nothing is settled, not least given the demonstrated ineptitude of the villains of the latest “Thing.” Optimistic action is a moral obligation in this situation; watch, don’t just read about, the example of the Indian farmers whose protests since 2020, drawing on memory of their struggle against British rule, have forestalled the billionaire-backed move to corporatize agriculture.

Right-wing American accelerationists dreaming of a world of high-tech enclaves governed as corporations dream an old dream. We have seen this EIC movie before. Oligarchy has always been an innate tendency of the modern state, one requiring stiffer resistance than Americans have yet offered. Democracy is, at its essence, the active challenging of “the Thing.” It’s time for Americans to be melodramatically democratic.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

HP FESTS: Dramione Teratophilia Fest (Part 1)

Dramione Teratophilia Fest 2.0 2023:

Grace Period by TeTe91 - E, WIP - After all the hardships and challenges Hermione had to face during the war, she is left empty-handed. Instead of a reward, she finds herself in a hopeless situation and struggles with the closed door to her previously bright future. Upset with the hand she has been dealt, she no longer sees any reasons to play by the rules, or even be good. Who better to unleash her anger onto than Draco Malfoy.

Coup de Grâce by ChaosAndCrumpets - E, WIP - The only place Hermione Granger finds some semblance of her former self is - inexplicably - in the arms of Draco Malfoy. But something so unnatural is sure to have wider implications. Then people start to die.

A Captured Moment by peachy_V, Roseheira - E, one-shot - Many wolves die having never experienced the love and devotion that can only come from one's true mate. And for the longest time Draco thought his fate would be condemned to a loveless life. Yet here she was, his mate. Conveniently brought to him, tied up like a present, and ready to be claimed by him.

Shadow Pact by Serpent_Sortia - E, WIP - “From Glittering Love to Gilded Betrayal! Golden Girl Heartbroken by Cheating Scandal” Or, what happens when a certain demon offers to help Hermione get revenge on her cheating ex?

Eternity by emmarauren - M, one-shot - Hermione Granger would wait an eternity for Draco Malfoy to love her back. Even if he is eternally a beast.

Bound by Darkness by BlueZeldana - E, WIP - Draco Malfoy had been living alone for years and no one knew he was alive. He was a murderer now, and the magic of his victims ran through his veins making him more and more powerful with each life he took. The only thing he cared about was power. Until a Muggleborn witch stepped into his manor and ruined everything.

Thick as blood by pinkhairandbooks - E, one-shot - You’re a Vampire Slayer and you find out that your soulmate is the Vampire that you are tasked to kill and almost killed you. What now?

The Claiming by Kayka - E, 5 chapters - The men of the Malfoy line have maintained a carefully guarded family secret for generations. Perpetually exhausted Hermione Granger is simply trying to get through her Thursday.

Starve This Sin by belladeexx - E, WIP - An age-old saying: An Angel on your right and the Devil on your left. In this case, Draco Malfoy is the pesky lust demon on the metaphorical left side of every shoulder Hermione interacts with. He's a constant thorn in her wings, albeit an attractive thorn she can't stop dreaming about, but a thorn nonetheless. After all, he's just a harmless demon on his knees begging for a taste of heaven. Who is Hermione to forbid him of it?

messy eater by riddikulus_puff - E, one-shot - Hermione Granger thought she had learned her lessons when it came to seeking food out during her nightly adventures as a newly turned vampire, but it seemed that she really hadn't learned anything. She had been given the title of "messy eater" when it came to her desperation and hunger and always seemingly made a mess of things. Usually, Hermione found that she could clean things up herself after satiating her hunger but it seemed as though that wasn't happening this time. Draco Malfoy, an older vampire who was more expressed with quelling his hunger, was nearby when Hermione needed help with cleaning herself and the crime scene up. He was used to this, his father being the one who originally turned Hermione and introduced her to him. Draco acted as a shadow for Hermione to follow, supposed to protect and show her the ways of the vampires.

My Love, My Moon by Art_emis, magicalmolly - E, one-shot - Hermione is filling in as the substitute Herbology Professor for Neville and hating it. While gathering materials in the Forbidden Forest one night, during the full moon, she's attacked by a werewolf. When she goes to hunt them down and demand that they leave the school grounds she finds out that the werewolf is none other than Draco Malfoy. But he's no ordinary werewolf and his attack has left them connected to one another in an unbearable way.

I See You by art_emissss - T, one-shot - The familiar thrill of the hunt only began to seep into her blood, and her skin itched with anticipation. Or: the one where Hermione miscalculates and gets something out of it.

there's always a straight way to the point by B_LovedHunter - T, one-shot - Hermione becomes an Animagus just in time for the start of her 8th year. Surprise. She's a cat. While roaming Hogwarts, she comes across a very distressed Draco Malfoy. Against her better judgement, she decides to comfort him. It turns out Draco is a cat person. **** “Granger came to find me in the library today.” She stopped purring. He kept stroking her absently. “She said she forgives me. I don’t know how or why, but she does,” He sighed deeply. “I believe her. Maybe you’ll meet her one day. She has a lot of wild hair and she’s a swotty, annoying sort–” WELL. “But she’s good. She’s good, and brilliant. Pretty too. She’s always been all of that, even when she had rather large teeth.” Well. “Don’t worry, love. Not as pretty as you.”

An Abysmal Riptide by Bana_Bhuidseach - M, WIP - To catch a siren one must set sail on a moonless night at the peak of the storm, to capture a siren one must risk meeting death by the relentless sea and its razor sharp rocks, to capture a siren sometimes it means losing ones mind and life in the process and the captain of the ¨Sea Dragon¨is about to find out what that means when he encounters her, the sweetest thing on this side of hell.

When Stars Align by art_emissss, thatblondebitvh - E, WIP - The one where Draco Malfoy fucks around and finds out.

Waiting For The Bite by rapunzerelli, Sophiesstreet - E, one-shot - Members of notoriously rivaled species, Draco Malfoy and Hermione Granger have only two things in common: a mutual hatred and a soulmate bond they unfortunately share. But when their lives are threatened by lingering followers of Voldemort and their bond forces them to protect each other, they find themselves thanking fate instead of blaming it.

For a Good Time by ymer - E, one-shot - Draco Malfoy finds a mysterious spell that starts as a dream before turning into a nightmare.

By These Fearful Places by ohthedrarry - M, 2 chapters - In his youth, Draco Malfoy had been little more than the disgraced son of an executed Senator. Hunger forced him to teach himself to hunt and risk his mortal life in woods ruled by the gods. Artemis took pity on the young boy and sent a woodland nymph to save him from a mountain lion who stalked him while he slept. Draco returned to that same forest ten years later, a man whose reputation exceeded that of even Odysseus. Fame and fortune gifted to him by his patron goddess no longer satisfied him. He craved the touch of that nymph who’d saved his life – and would risk everything to take it.

Never Let You Go by cauldronofmenace - M, one-shot - Draco is a vampire. Hermione is his prisoner. She has sexy dreams about him and he's happy to make them a reality.

The Sun and Her Shadow by daydreamstory, Ivmaruva - E, WIP - She travels across barren stretches of an eternal night to find him. He waits for her there, on the dark side of the moon.

Blood Moon by NinaBinaBallerina - E, WIP - Under a blood moon, Lycans hunt the forest for their mates. And Draco Malfoy knew just the witch he wanted to sink his teeth into.

You’re Everything a Big, Bad Wolf Could Want by LaLuneMoonstone - E, 2 chapters - A trip into the forbidden forest under the waxing crescent to get herbs for potions plus a new read cloak lands Hermione in a mate situation. Little red riding hood never had to deal with this, or did she?

The Banshee of Biddeford Pond by atomicbombshell - G, one-shot - no summary

La Appel du Vide by CSIsui - E, one-shot - “Flora has always been the most innocent and, at the same time, the most perverse medium for symbolism all throughout history.” Draco once heard in her lecture. “From Georgia O’Keefe to Shakespeare and ancient history, flora has been the favourite when it comes to cheeky sex symbols.” And she was right

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

Possible Inspiration for Maud Beaton 2.0

Elizabeth "Betty" Bigley a.k.a Cassie Chadwick

She was a Gilded Age scammer who used a false identity as the illegitimate daughter of Andrew Carnegie to swindle hundreds of thousands of dollars from wealthy individuals and banks alike. After she was caught, her trial became a media circus with Carnegie himself attending. Her story in particular reveals a lot about how gender roles and propriety in the era could be leveraged by an ambitious con-man to get what they want.

Her schemes seems different from Maud's (possible) scheme. Obviously, like any historical analog, the narrative we are seeing would probably just be broad strokes. But, I think it is revelatory to examine the real historical events of the time and how they differ from what we see on TV. I urge you to look into it if you are interested!

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

I mean, if they want to do Gilded Age 2.0 we can get it on. I'm not looking forward to the mix of dynamite and drones but let's go.

tbh it seems like they want us to bring it back

9K notes

·

View notes

Text

i hate living in the gilded age 2.0 can we move onto the fdr stage already but minus the ww please

0 notes

Text

March Wrap Up

The Amazing Remarkable Monsieur Leotard - Eddie Campbell & Dan Best [1.75 stars]

While I like seeing graphic novelists experiment with form, in this instance, it gave me a bit of a headache. But at the same time, it worked as it revolves around the son of a circus ringmaster who then takes his place after he dies. So it did aid in setting the absurdism of the setting, allowing it to be more character-driven. And it emphasized how unreliable a narrator Monsieur Leotard is.

The Cat Lover's Craft Book: Cute and Easy Accessories for Kitty's Best Friend - Neko Shugei [2.0 stars] Cat on the Hero’s Lap Vol 2 - Kousuke Iijima [2.5 stars] Everything, Everything - Nicola Yoon [3.75 stars]

I have spent eons in fandom spheres where 3rd person is preferred over 1st person when it comes to fanfiction and man, is it refreshing to see 1st person stuff again. Being in 1st person helped cement the living situation that Madeline goes through. Which has been kinda shot in the foot with the pandemic happening but there was no way Nicola Yoon could've predicted a global pandemic was going to happen 5 years after publishing. Then again, I still think the stir-crazy sensation felt during said time was exemplified through how Maddie navigates her emotions, even with the whole insta-love element. Along with the added visuals.

The biggest nitpick I have is just who is paying off the credit card that Madeline uses? Not only that but the ending, after the plot twist felt extremely abrupt. That and I don't appreciate Carla trying to coax her into forgiving her mother. It's not necessarily out of character. Granted that was a bit open-ended with her (Maddie) saying that she didn't know the bubble she had grown up in was still home. Also her meeting up with Oliver in New York didn't feel solid enough. Also if he's not living at home, why is the ornery still up? But overall, I enjoyed reading it.

Favorite bit of the book was pg 196, where Madeline was internally describing her 1st time walking on the beach.

Last thing to note is that I had seen the movie when it was released in theaters so the twist with the mom was already spoiled.

Killers of the Flower Moon - David Grann [5.0 stars]

I had seen the movie adaptation of this book that Martin Scorsese did when it had got put on streaming services and gotta say, the book is loads better. Like he cut out so, so much of the FBI investigation with Tom White and his makeshift crew which would've helped with the pacing issues. The book is divided into 3 sections. The first one going into the murders of Anna Brown, Charles Whitehorn, and George Bigheart, alongside the house explosion of Rita and Bill Smith, setting the scene. In this section, it also goes into depth about the Osage tribe's traditions and how they had been forced to assimilate due to their various everyday interactions with white people. Such as the Christian boarding school Mollie was sent to. Explaining the headright system and that a lot of them weren't able to have access to their own money as they weren't deemed mentally competent.

The second section details the FBI investigation and how it helped cement the FBI as a credible federal institution under Hoover. Emphasizing the corruption rife within the government during the 1920s with the Teapot Dome Controversy which was carried over by the gilded age. Many officials were bribed by rich oilmen. Which we seem to be paralleling with Trump and Musk (more people should've clocked him when he began using Reagan's tagline.) And how far William Hale's power stretched within the county. That he muddied the original investigation by creating false evidence to replace/misdirect from actual evidence. Even able to infiltrate the FBI's investigative crew with Kelsie Morrison and how it took multiple attempts to find an impartial jury to convict him.

The final section revolves around the relatives of those murdered. Interviewing them and what they know about the murders, how it has affected them and the surrounding community. What has become of the oil reserves and the headright system. Furthermore the author himself, reviews the investigation with material found at the National Archives. In attempts to find the missing link between some of the 25+ murders as not all of them tied back to Hale or Burkhart. Discovering that there was in fact a third central man; H.G Burt.

#bookblr#booklr#monthly wrap up#march wrap up#wrap up#reviews#book reviews#killers of the flower moon#everything everything#the amazing remarkable monsieur leotard

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Deep Roots of Oligarchy! Private Contracting Is In The DNA of The Modern State.

— March 25, 2025 | By Priya Satia | Foreign Policy

A Painting of the British East India Company’s Lord Robert Clive Overlaid with a Battle Scene From the American Revolution and Images of Modern Protest. Illustration For Foreign Policy/Nathaniel Dance Painting/Hulton Archive/Getty Images; New York Public Library; iStock Photo

Late in 1774, Lord Robert Clive was found dead in his London townhouse. Rumors flew that conscience had finally compelled the rapacious conqueror to take his own life. Having just arrived in Pennsylvania from England, Thomas Paine recalled how the riches Clive wrested through “murder and rapine” and “famine and wretchedness” in India had enveloped him in the “sunshine of sovereign favor” at home, allowing him to enter into further “schemes of war … and intrigue” to amass an “unbounded fortune.” In the end, however, “guilt and melancholy” had proved “poisons of quick despatch.”

Clive was a reckless fortune-hunter in the British East India Company (EIC), the chartered monopoly company trading in the Indian Ocean region—heavily armed, to compel trade on its terms. When the British and French went to war globally in 1756, their rivalrous companies in India did, too, and Clive secured the EIC’s first major territory in Bengal in 1757. Long-held company towns at the subcontinent’s edges expanded into a company-owned state.

This Article Appears in the Spring 2025 Issue of Foreign Policy.

The company’s shareholders sat in the British Parliament and were politically powerful. Those who rose up in it acquired power as well. Plunder of gold and jewels and a rich annuity in land revenue enabled Clive to secure an Irish barony, a country estate in Shropshire, and a seat in Parliament, as well as seats for his friends. The term for such nouveaux riches, “nabob”—a corruption of the Hindustani word nawab, or prince—captured their political presumption.

This was the Britain that Americans rebelled against.

Since the launch of Trump 2.0, both supporters and critics have analogized its unapologetic embrace of financial and tech titans to America’s Gilded Age. Others see in the administration’s ambitions in Greenland and Panama a throwback to the 19th-century private contractors of colonialism. But the 19th century was itself a new twist on an older oligarchic model exemplified by Clive. Private contracting is in the DNA of the modern state structures that Americans adopted—forgetting that they had rebelled not just against monarchy but also an oligarchic Parliament. Revisiting that foundational struggle shifts our perspective on the threat oligarchy poses today and the tactics needed to contend with it.

A Satirical Drawing from 1788 Depicts King George III, Queen Charlotte, and Dignitaries of the British Church and State Scrambling for Rupees From an East India Company Nabob. Culture Club/Getty Images

Traditional monarchs were corporate bodies in their own right, expressing the body politic in their personal form. From the 16th century, the British monarchy also relied on another kind of corporation, the chartered monopoly company, to pursue interests abroad, including the EIC, Virginia Company, Massachusetts Bay Company, Royal African Company, and Hudson’s Bay Company. Members of such companies enormously influenced the government bureaucracy that began to emerge to address the questions of trade and war that their activities sparked. Finally, with the 1688-89 Glorious Revolution, Parliament, controlled by wealthy elites also involved in such enterprises, dramatically curbed kingly authority; sovereignty migrated from the king’s person to the nascent institutions of the modern state, a new form of continuous public power above the ruler and the ruled.

This state was an oligarchy. The aristocrats who controlled Parliament used it to usurp the common rights of ordinary people, passing thousands of laws privatizing land—an internal colonialism that displaced masses of people, many of whom took their memory of oligarchic injury to North America, where they in turn displaced Indigenous inhabitants. The state also depended on contractors and corporations such as the EIC for the military and financial organization that it still lacked. Corporations’ interests in Asia, Africa, and the Americas were entangled with and dependent on Britain’s diplomatic, military, and political pursuits. Apart from trade and conquest, such companies bought, sold, and leased sovereignty like a commodity, as, for instance, with the EIC’s creation and sale of the princely state of “Jammu and Kashmir” to its allies in its conquest of Punjab.

Ordinary Britons were incensed by the hot mess of private wealth and state power in this time, which saw the most consistently negative depictions of big business ever.

In short, corporations were the new state’s partners in governance. The British state was Parliament, an emerging fiscal-military bureaucracy, and the Crown, plus corporations (including the Royal Mint and the Bank of England) and private contractors and financiers. In this sense, it, too, had a corporate form. It’s impossible to say where the state ended and the private sphere began. Great landowners and merchant oligarchs sat in Parliament but also held wide, unsupervised local powers as lord lieutenants, sheriffs, justices of the peace. Such unpaid positions layered state authority on their holders’ local social status and private wealth. They secured compliance with the threat of legitimate force, even though they did not always see themselves primarily as agents of the state and their power did not derive solely from their office.

Most Americans know that when Parliament asked the colonists to help fund debt accrued in the massive Seven Years’ War, which lasted until 1763, they cried, “No taxation without representation!” But ordinary Britons were also incensed by the hot mess of private wealth and state power in this time, which saw the most consistently negative depictions of big business ever. Followers of the radical politician John Wilkes likened the alliance among elites across the state, land, commerce, finance, and industry to a gang of robbers plundering society. Popular reform movements involved petitions and pamphleteering but also marches and mass meetings incorporating song and religious feeling—crowd politics.

Airing of the EIC’s corruption and cruelties as it teetered on the verge of bankruptcy in 1772, threatening the nation’s finances, fueled censure of figures such as Clive. Sharply attacking the company, the philosopher Adam Smith theorized a society in which a private economic realm free from state intervention would drive world-historical progress. The Wealth of Nations, published in 1776, called not for recognition of boundaries between the public and private spheres but the creation of such boundaries—the liberal political-economic principle that shapes many Americans’ expectations of the relationship between government and society today.

Paine wrote about Clive’s death against this backdrop of ire against oligarchy in Britain and the Colonies—months before he drafted Common Sense, the incendiary pamphlet released in 1776 as Americans revolted. Fury about the EIC’s abuses fueled anger at Parliament’s treatment of the Colonies. In 1778, Paine noted the poetic justice that Indian tea had kindled a war in America “to punish the destroyer.” The villain was not just King George III but the oligarchy that had already checked his power

After the Revolutionary War, the British public persisted in attacking military contractors, for reaping profits despite the country’s humiliating defeat, and financiers, for defrauding the public by exploiting their relationships with government offices for personal gain. When contracting exploded during the long wars against France from 1793 to 1815, popular radicals such as William Cobbett condemned this system of “Old Corruption,” dubbing the nexus of power, patronage, and wealth “the THING.”

In the face of sustained outcry, new institutions did evolve to exert control over the state’s private partners. The EIC, for instance, was integrated into the bureaucratic structure of the state, and new state offices, the Colonial and Foreign offices, were formed to engage in activities previously entirely outsourced to corporations.

Americans, too, worked to create institutions that would limit the potential for despotism. To be sure, the “articles” incorporating their government echoed the company charters that governed the earliest Colonies and gave Americans their understanding of a constitution: a written charter from a sovereign ordaining and setting out the limits of a government. But now “the people,” rather than the monarch, were the sovereign. Both countries also pursued civil service reform in the 19th century, meaning fewer political appointees and buying of positions—the creation of the professionalized government bureaucracy that the Trump administration is attempting to undo.

The process of separating business from state activity took time and remained ever incomplete because these states were designed for the pursuit of territorial expansion and maintenance of power within that territory through a security establishment. Both governments thus continued to invest in military industry and depend on contractors and corporate control of media, and a revolving door kept elites in these fields intimate with government offices. While the robber barons of the Gilded Age shaped U.S. industrial policies and westward expansion, monopoly companies continued to undertake British colonial expansion, profiting from government support while relieving the government of responsibility. Cecil Rhodes’s British South Africa Company is merely the most famous, or infamous, of the companies that dominated this era.

Both countries also pursued civil service reform in the 19th century, meaning fewer political appointees and buying of positions—the creation of the professionalized government bureaucracy that the Trump administration is attempting to undo.

Rhodes’s machinations triggered a grueling war in South Africa in which Britain prevailed only by recourse to scorched-earth tactics and concentration camps. Covering the war for the Manchester Guardian, the economist J.A. Hobson perceived that reckless imperialism was driven by oligarchs who hijacked foreign policy to serve their ends—inspiring Vladimir Lenin’s later critique of imperialism as the highest stage of capitalism. Such theorists grasped that asserting sovereignty uniformly across a bounded space was innately colonial, requiring the backing of military or security contractors and financiers. Voting was no guarantee of a democratic check on their power and policies, given the way that private donations swayed elections and that press barons cozy with the government manipulated public opinion in favor of jingoistic causes.

After World War I, a wised-up British public with a mass franchise and more consciously assertive press railed passionately against the sway of arms contractors who led the country into unnecessary conflicts. Again, imperial conflicts continued, albeit at times more covertly, to evade public scrutiny.

The public failed to dislodge oligarchic influence partly because it focused on tactics that liberalism prioritized at the expense of the more powerful tools it once wielded. From the 18th century, British reformers focused on franchise expansion as the key to changing Parliament’s composition and thus breaking the elite monopoly of state power. This emphasis on institutions of formal democracy was rooted in liberal ideals of political subjectivity: a highly individualized coherent self who formed his (and I mean “his,” up until after World War I) opinions rationally through careful reading of material produced by a presumptively free press. Institutionalized politics and secret balloting would deliver progress, liberal philosophers assured. This ideal meant moving away from the more fluid and collective sense of identity that drove the subversive street politics of the 17th and 18th centuries. Faith in print media facilitating debate among enlightened individuals undermined the emotive, melodramatic, and collective uses of more radically democratic forms of political expression, as did the state’s expanding capacity to police public spaces.

A Depiction of the Boston Tea Party in Boston Harbor in 1773. Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

The cult of MAGA deflects ordinary Americans’ frustration with a government that has long failed them toward such fellow victims of oligarchy, while Trump and his accomplices downsize the corporate U.S. government like maniacal management consultants to fully monopolize its capacities for their own ends.

Much distinguishes the current moment, not least that the stakes are planetary. But this is no freakishly unprecedented capture of a democracy by corporate power. The failure to recognize that the United States was born out of rebellion against oligarchy, not just monarchy, has long helped preserve oligarchic influence in the country. Even Sen. Bernie Sanders likens today’s oligarchs to the kings who ruled Americans by divine right before the 1770s, forgetting the oligarchic tyranny of Parliament.

Perhaps partly because Britons are more aware of their long struggle against oligarchy, as evident in Thompson’s invocation of Cobbett’s “Thing,” they have been more able to regulate campaign finance, albeit still not enough to prevent the rise of super-rich politicians such as Rishi Sunak (who married into India’s billionaire class), plutocratic control of the country’s biggest newspapers, and ideologically driven dismantling of the very state regulatory functions that could keep corruption in check.

Americans can mourn the loss of even the pretense of separation between government and big money. But the stark revelation of their entanglement is also an opportunity to rethink inherited concepts of normative governance and democracy.

The lesson of the past three centuries of recurring oligarchic influence on elections and governance is that democracy cannot be just about voting. Nor can we simply hope that the courts will challenge the avalanche of executive orders. Confronting oligarchy requires reclaiming the local forms of sovereignty sacrificed at its altar, which means collective action, forged through values of mutuality, outside electoral and legal institutions. It is worth considering whether British victims of 18th-century oligarchy might have more effectively defended the commons had they stayed rather than become settlers visiting their rage upon others abroad. Federal governments that are more substantively federal (i.e., not uniformly sovereign across their territory) yield less easily to oligarchic influence. The same applies to India.

The failure to recognize that the United States was born out of rebellion against oligarchy, not just monarchy, has long helped preserve oligarchic influence in the country.

To be sure, some of the Trump administration’s cheerleaders insist that dismantling the federal government is precisely about returning power to local communities and states. But the public goods at stake—food and air safety, public health—are necessarily federal. If the oligarchs call for privatizing the Postal Service and space exploration, the people should call for nationalizing X. Moreover, without reversion of federal taxes to local units, such rhetoric is merely cover-up for the administration’s actual effort to lay claim to local resources to serve its own ends. Local governments have already launched lawsuits against this imperial assertion.

Paine was too optimistic about Clive’s liberal subjectivity. Most probably, Clive did not die by his own hand but from overmedicating abdominal pain with opium. Conscience can’t stay the hand of unstable, violent, narcissistic personalities; it requires action, melodramatic action, from others. Some, however, are already pouring their melodramatic capacities into dark proclamations of a ruthless new order. Such despair in the world of print arises perhaps from the disappointed expectation of progress by the expected means. But nothing is settled, not least given the demonstrated ineptitude of the villains of the latest “Thing.” Optimistic action is a moral obligation in this situation; watch, don’t just read about, the example of the Indian farmers whose protests since 2020, drawing on memory of their struggle against British rule, have forestalled the billionaire-backed move to corporatize agriculture.

Right-wing American accelerationists dreaming of a world of high-tech enclaves governed as corporations dream an old dream. We have seen this EIC movie before. Oligarchy has always been an innate tendency of the modern state, one requiring stiffer resistance than Americans have yet offered. Democracy is, at its essence, the active challenging of “the Thing.” It’s time for Americans to be melodramatically democratic.

— Priya Satia is the Raymond A. Spruance Professor of International History at Stanford University and the Award-winning Author of Spies in Arabia: The Great War and the Cultural Foundations of Britain’s Covert Empire in the Middle East and Empire of Guns: The Violent Making of the Industrial Revolution. Her most recent book is Time’s Monster: How History Makes History.

#Oligarchy#The Deep Roots of Oligarchy!#DNA#Modern State#Foreign Policy#Priya Satia#Britain 🇬🇧#United States 🇺🇸#Donald J. Trash 🗑️ Trumpet 🎺#Economics#History#Randia 🇮🇳

0 notes

Text

amazing caliber of reporting in the gilded age 2.0. do you think there's another bloody handed insurance exec out there reading this and shitting himself

0 notes

Photo

Elon Musk Elon Musk Contributor(s): Isaacson, Walter (Author) Publisher: Simon & Schuster Physical Info: 2.0" H x 9.4" L x 6.1" W (2.25 lbs) 688 pages When Elon Musk was a kid in South Africa, he was regularly beaten by bullies ... But the physical scars were minor compared to the emotional ones inflicted by his father, an engineer, rogue, and charismatic fantasist. His father's impact on his psyche would linger. He developed into a tough yet vulnerable man-child, prone to abrupt Jekyll-and-Hyde mood swings, with an exceedingly high tolerance for risk, a craving for drama, an epic sense of mission, and a maniacal intensity that was callous and at times destructive. ... For two years, Isaacson shadowed Musk, attended his meetings, walked his factories with him, and spent hours interviewing him, his family, friends, coworkers, and adversaries. The result is the revealing inside story, filled with ... tales of triumphs and turmoil, that addresses the question: are the demons that drive Musk also what it takes to drive innovation and progress Walter Isaacson is the bestselling author of biographies of Jennifer Doudna, Leonardo da Vinci, Steve Jobs, Benjamin Franklin, and Albert Einstein. He is a professor of history at Tulane and was CEO of the Aspen Institute, chair of CNN, and editor of Time. He was awarded the National Humanities Medal in 2023. Visit him at Isaacson.Tulane.edu. Review Quotes: Shortlisted for the Financial Times and Schroders Business Book of the Year "Whatever you think of Mr. Musk, he is a man worth understanding-- which makes this a book worth reading." -- The Economist "With Elon Musk, Walter Isaacson offers both an engaging chronicle of his subject's busy life so far and some compelling answers..." -- Wall Street Journal "Walter Isaacson's new biography of Elon Musk, published Monday, delivers as promised -- a comprehensive, deeply reported chronicle of the world-shaping tech mogul's life, a twin to the author's similarly thick 2011 biography of Steve Jobs. Details ranging from the personally salacious to the geopolitically volatile have already made the rounds -- the rare example of a major book publication causing a news cycle in its own right...What Isaacson's biography reveals through its personalized lens on Musk's work with Tesla, SpaceX, OpenAI, and more is not only what Musk wants, but how and why he plans to do it. The portrait that emerges is one that resembles a hard-charging, frequently alienating Gilded Age-style captain of industry, with a particular fixation on AI that ties everything together....Isaacson's book is like a decoder ring, tying the mercurial Musk's various obsessions into a coherent worldview with a startlingly concrete goal at its center." -- Politico "[The book] has everything you'd expect from a book on Musk--stories of tragedy, triumph, and turmoil.... While the stories are fascinating and guaranteed to spark a mountain of coverage, founders and entrepreneurs will also unearth valuable lessons." -- Inc. "Isaacson has gathered information from the man's admirers and critics. He lays all of it out.... The book is bursting with stories....A deeply engrossing tale of a spectacular American innovator. " -- New York Journal of Books "One of the greatest biographers in America has written a massive book about the richest man in the world. This fast-paced biography, based on more than a hundred interviews...[is] a head-spinning tale about a vain, brilliant, sometimes cruel figure whose ambitions are actively shaping the future of human life." --Ron Charles on CBS Sunday Morning "A painstakingly excavation of the tortured unquiet mind of the world's richest man... Isaacson's book is not a soaring portrait of a captain of industry, but rather an exhausting ride through the life of a man who seems incapable of happiness." -- The Sunday Times "An experienced biographer's comprehensive study." --The Observer "Walter Isaacson's all-access biography... Its portrait of the tech maverick is fascinating." --The Telegraph "Isaacson boils Musk down to two men... the result is a beat-by-beat book that follows him insider important rooms and explores obscure regions of his mind." --The Times Publisher Marketing: The #1 New York Times bestseller from the author of Steve Jobs--this is the astonishingly intimate story of the most fascinating and controversial innovator of our era--a rule-breaking visionary who helped to lead the world into the era of electric vehicles, private space exploration, and artificial intelligence. Oh, and took over Twitter. When Elon Musk was a kid in South Africa, he was regularly beaten by bullies. One day a group pushed him down some concrete steps and kicked him until his face was a swollen ball of flesh. He was in the hospital for a week. But the physical scars were minor compared to the emotional ones inflicted by his father, an engineer, rogue, and charismatic fantasist. His father's impact on his psyche would linger. He developed into a tough yet vulnerable man-child, prone to abrupt Jekyll-and-Hyde mood swings, with an exceedingly high tolerance for risk, a craving for drama, an epic sense of mission, and a maniacal intensity that was callous and at times destructive. At the beginning of 2022--after a year marked by SpaceX launching thirty-one rockets into orbit, Tesla selling a million cars, and him becoming the richest man on earth--Musk spoke ruefully about his compulsion to stir up dramas. "I need to shift my mindset away from being in crisis mode, which it has been for about fourteen years now, or arguably most of my life," he said. It was a wistful comment, not a New Year's resolution. Even as he said it, he was secretly buying up shares of Twitter, the world's ultimate playground. Over the years, whenever he was in a dark place, his mind went back to being bullied on the playground. Now he had the chance to own the playground. For two years, Isaacson shadowed Musk, attended his meetings, walked his factories with him, and spent hours interviewing him, his family, friends, coworkers, and adversaries. The result is the revealing inside story, filled with amazing tales of triumphs and turmoil, that addresses the question: are the demons that drive Musk also what it takes to drive innovation and progress?

0 notes